Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Comparison of Transverse and Vertical Skin Incision For

Hochgeladen von

Herry SasukeCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Comparison of Transverse and Vertical Skin Incision For

Hochgeladen von

Herry SasukeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Published in final edited form as:

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. 2010 June ; 115(6): 11341140. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181df937f.

Comparison of Transverse and Vertical Skin Incision for

Emergency Cesarean Delivery

Blair J. Wylie, MD, MPH, Sharon Gilbert, MS, MBA, Mark B. Landon, MD, Catherine Y.

Spong, MD, Dwight J. Rouse, MD, Kenneth J. Leveno, MD, Michael W. Varner, MD, Steve N.

Caritis, MD, Paul J. Meis, MD, Ronald J. Wapner, MD, Yoram Sorokin, MD, Menachem

Miodovnik, MD, Mary J. OSullivan, MD, Baha M. Sibai, MD, and Oded Langer, MD for the

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

(NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU)*

Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University, New York, New York; The Ohio

State University, Columbus, Ohio; the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham,

Alabama; the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas; the University of

Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Wake Forest

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

University Health Sciences, Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Thomas Jefferson University,

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan; the University of

Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio; the University of Miami, Miami, Florida; the University of Tennessee,

Memphis, Tennessee; the University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas; and the

George Washington University Biostatistics Center, Washington, DC; and the Eunice Kennedy

Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Maryland

Abstract

OBJECTIVETo compare incision-to-delivery intervals and related maternal and neonatal

outcomes by skin incision in primary and repeat emergent cesarean deliveries.

METHODSFrom 1999 to 2000, a prospective cohort study of all cesarean deliveries was

conducted at 13 hospitals comprising the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child

Health and Human Developments MaternalFetal Medicine Units Network. This secondary

analysis was limited to emergent procedures, defined as those performed for cord prolapse,

abruption, placenta previa with hemorrhage, nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing, or uterine

rupture. Incision-to-delivery intervals, incision-to-closure intervals, and maternal outcomes were

compared by skin-incision type (transverse compared with vertical) after stratifying for primary

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

2010 by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Corresponding author: Blair J. Wylie, MD, MPH, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55

Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114; bwylie@partners.org.

*For a list of other members of the NICHD MFMU, see the Appendix online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/A177.

Presented at the 53rd Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation, March 2225, 2006, Toronto, Canada.

Dr. Spong, Associate Editor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, was not involved in the review or decision to publish this article.

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Landon received honoraria for doing grand rounds at various institutions and travel and accommodation expenses covered or

reimbursed for grand rounds. Dr. Leveno received royalties for the Williams Obstetrics textbook. Dr. Varner received grants or grants

pending from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) for research conducted with funding from the

NICHD MaternalFetal Medicine Units Network. Dr. Miodovnik received a grant, NIH-NICHD HD-27905-05 (until 2003). Dr.

OSullivan was reimbursed for travel expenses related to this study by the NICHD; participated in the data monitoring committee after

no longer a member of the study group and the compensation for travel and hotel was reimbursed by the NICHD; received a grant or

has grants pending from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for The Womens Health Initiative (WHI; The National

Childrens Study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health); travel and accommodation expenses were reimbursed by NHLBI for

the WHI annual meeting. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Wylie et al. Page 2

compared with repeat singleton cesarean delivery. Neonatal outcomes were compared by skin-

incision type.

RESULTSOf the 37,112 live singleton cesarean deliveries, 3,525 (9.5%) were performed for

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

emergent indications of which 2,498 (70.9%) were performed by transverse and the remaining

1,027 (29.1%) by vertical incision. Vertical skin incision shortened median incision-to-delivery

intervals by 1 minute (3 compared with 4 minutes, P<.001) in primary and 2 minutes (3 compared

with 5 minutes, P<.001) in repeat cesarean deliveries. Total median operative time was longer

after vertical skin incision by 3 minutes in primary (46 compared with 43 minutes, P<.001) and 4

minutes in repeat cesarean deliveries (56 compared with 52 minutes, P<.001). Neonates delivered

through a vertical incision were more likely to have an umbilical artery pH of less than 7.0 (10%

compared with 7%, P=.02), to be intubated in the delivery room (17% compared with 13%, P=.

001), or to be diagnosed with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (3% compared with 1%, P<.001).

CONCLUSIONIn emergency cesarean deliveries, neonatal delivery occurred more quickly

after a vertical skin incision, but this was not associated with improved neonatal outcomes.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCEII

Since its initial description in 1897 by Pfannenstiel,1 a transverse suprapubic incision has

been used frequently in both obstetric and gynecologic surgeries. As initially described, the

Pfannenstiel incision includes dissection of the rectus muscles from the overlying fascia and

ligation of any perforating vessels encountered. In emergency situations, tradition has taught

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

that abdominal entry at the time of cesarean delivery may be facilitated more rapidly

through a midline vertical skin incision because rectus dissection is not required and

perforating vessels are thus not encountered.2 The Pfannenstiel incision is cosmetically more

attractive than a vertical incision, is familiar to the obstetric surgeon, and may be associated

with less postoperative pain and a lower risk of hernia formation, leading many practitioners

to choose this incision location even in emergencies.3

Randomized evaluations of skin incisions for cesarean delivery have been limited to

comparisons between the Pfannenstiel and modifications of this transverse skin incision

such as the muscle-splitting Maylard incision or the Joel-Cohen incision during which tissue

layers are opened bluntly and dissection of the rectus muscles is not required. In these

comparisons, the Joel-Cohen entry appears to offer certain advantages, including shorter

incision-to-delivery intervals, less blood loss, shorter operating time, reduced time to oral

intake, shorter duration of postoperative pain, and a shorter length of stay.4,5

The literature comparing transverse with vertical skin incisions for cesarean delivery is

sparse. One study compared 619 cesarean deliveries performed by midline incision with 328

performed by Pfannenstiel skin incision and found no difference in postoperative

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

complications such as wound healing or wound hematoma.6 The time required to deliver the

neonate was not compared, and both elective and emergency deliveries were included.

The purported shorter incision time with a vertical incision has not been rigorously

confirmed. Therefore, the purpose of this analysis was to compare incision-to-delivery

intervals, total operative time, and maternal and neonatal outcomes by skin incision

(transverse compared with vertical) in a large cohort of women undergoing emergency

cesarean delivery at multiple hospitals throughout the United States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The cesarean registry, a prospective observational study conducted by 13 institutions in the

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

MaternalFetal Medicine Units Network between 1999 and 2002, was designed to assess

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 3

several specific contemporary issues.7 During the first 2 years of the cohort, information

concerning all cesarean births within the MaternalFetal Medicine Units Network was

ascertained. During the second 2 years, data were collected only for repeat cesareans and

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

attempted vaginal births after prior cesarean. For the current study, only data collected

during the first 2 years of the study were analyzed so that there would not be an imbalance

in the type of cesarean deliveries. Each participating network center and the data

coordinating center received Institutional Review Board approval for this study.

Detailed information regarding maternal demographic characteristics, medical and

obstetrical history, intrapartum course, postpartum complications diagnosed before hospital

discharge, and neonatal outcome was abstracted directly from maternal and neonatal charts

by specially trained and certified research nurses. Longer-term maternal outcomes such as

chronic pain, hernia formation, and cosmetic satisfaction were not available from the

registry.

This analysis was limited to singleton emergency cesarean deliveries defined as those

indicated to be emergent on individual record review that were performed for a diagnosis of

umbilical cord prolapse, abruption, placenta previa with hemorrhage, nonreassuring fetal

heart rate tracing, or uterine rupture. Stillbirths (n=27) were excluded because this could

potentially influence the swiftness of delivery. Skin incisions were coded as either transverse

or vertical. Skin incision, neonatal delivery, and skin closure times were ascertained from

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

intraoperative records and used to calculate incision-to-delivery and incision-to-closure

intervals in minutes.

Baseline variables and maternal delivery characteristics were compared by skin-incision

type. Categorical variables were compared using the Pearsons chi-square or the Fisher exact

test. Continuous variables were compared by the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Time intervals

were analyzed by transverse compared with vertical skin-incision type after stratifying by

primary compared with repeat cesarean delivery. Analysis of covariance was conducted

after stratifying by primary and repeat cesarean deliveries to compare the mean differences

in time intervals between the skin incision groups adjusting for body mass index at

delivery.8 Analysis was confirmed using rank analysis of covariance because the data

violated the normality assumption of the residuals by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In

addition, a subgroup analysis of incision-to-delivery intervals by indication for emergent

delivery was performed. For maternal outcomes, the cohort was compared by type of skin

incision after stratifying by primary compared with repeat cesarean delivery. Neonatal

outcomes were compared by type of skin incision. Nominal two-sided probability values are

reported with statistical significance defined as P<.05. No adjustments were made for

multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

During 1999 and 2000, a total of 184,387 women delivered in MaternalFetal Medicine

Units Network hospitals and 39,283 (21.3%) of these women underwent cesarean delivery.

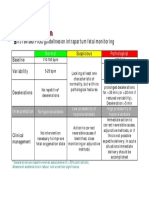

As shown in Figure 1, 3,525 (9.5%) emergency cesarean deliveries of singleton live births

were available for analysis. A transverse incision was performed in 2,498 (70.9%) of these

deliveries and vertical skin incisions performed in the remaining 1,027 (29.1%). Vertical

incisions were more commonly performed during emergent cesarean deliveries than during

nonemergent cesarean deliveries (29.1% compared with 20.4%, P<.001). The proportion of

women undergoing vertical incisions did not differ by indication for emergent delivery (P=.

34).

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 4

Women delivered by a transverse skin incision had a lower body mass index at delivery and

were more likely to be nulliparous and white (Table 1). Women with a transverse skin

incision were more likely to be undergoing a primary cesarean delivery compared with those

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

in the vertical group (84% compared with 81%, P=.01) (Table 2). There were no other

differences in assessed delivery characteristics.

In primary emergency cesarean deliveries, the median incision-to-delivery interval was 1

minute longer in women with a transverse skin incision when compared with those having

vertical incisions (median 4, interquartile range 27 compared with median 3, interquartile

range 24, P<.001) (Table 3). Among women undergoing repeat emergency cesarean

deliveries, the median incision-to-delivery was 2 minutes longer with a transverse incision

(median 5, interquartile range 39 compared with median 3, interquartile range 26, P<.001)

(Table 3). Even after adjusting for body mass index at delivery using analysis of covariance,

both primary and repeat cesarean deliveries had longer mean incision-to-delivery intervals

with transverse incisions. For primary cesareans, the adjusted mean difference was 2.0

minutes (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.4, P<.001). For repeat cesareans, the adjusted

mean difference was 1.6 minutes (95% confidence interval 0.6 to 2.6, P=.002). Despite

longer incision-to-delivery intervals, the median total operative time was shorter by 3

minutes in primary cesarean deliveries and by 4 minutes in repeat cesarean deliveries for

surgeries performed through a transverse skin incision (Table 3).

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Longer incision-to-delivery intervals by transverse incision occurred both among centers

that performed the majority of their emergency cesarean deliveries by transverse skin

incision as well as among those primarily performing vertical incisions (data not shown). In

subgroup analysis by indication for emergent cesarean delivery, a longer incision-to-delivery

interval was again evident for transverse incisions performed for nonreassuring fetal

tracings, abruptions, or cord prolapse. The longer intervals did not reach statistical

significance in the previa with hemorrhage or uterine rupture subgroup perhaps secondary to

a small sample size (Table 4).

Table 5 demonstrates selected maternal outcomes. There were no differences identified in

the risk of intraoperative injury (broad ligament hematoma, cystotomy, bowel injury,

ureteral injury) or postoperative ileus by type of skin incision. The frequency of wound

infections and wound hematomas was similar between the two skin incision groups. Among

women with vertical skin incisions, postpartum transfusions were more common both after

primary (7% compared with 5%, P=.01) and repeat cesarean delivery (14% compared with

8%, P=.02). Among primary emergency cesarean deliveries, there was an increased

incidence of postpartum endometritis in women delivered by vertical skin incisions (15%

compared with 11%, P=.006). Length of stay after discharge was similar in both groups.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Despite shorter incision-to-delivery intervals, neonates delivered through a vertical incision

were more likely to be intubated in the delivery room, to have an umbilical artery pH less

than 7.0, or to be diagnosed with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (Table 6). There were no

differences in neonatal outcomes by skin-incision type after cord prolapse, the subgroup that

was delivered the swiftest (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This secondary analysis of a large cohort of women undergoing emergency cesarean

delivery sought to answer the question of whether the skin incision, transverse compared

with vertical, is associated with a difference in the incision-to-delivery time, total operative

time, maternal complications, or adverse neonatal outcomes. In this study, transverse skin

incision lengthened the median incision-to-delivery interval by 1 minute for primary

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 5

cesarean deliveries and by 2 minutes for repeat cesarean deliveries. Our sample size allowed

for more than 80% power to detect a 0.25 standard deviation for the incision-to-delivery

interval between the vertical and transverse incision groups in both primary and repeat

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

cesarean deliveries.

We recognize that differences in speed of entry after the two incision locations may vary by

institution or by individual surgeon. Nonetheless, in our cohort, newborn extraction was

swifter after a vertical incision, even in centers that performed the majority of emergency

deliveries by transverse incision.

It is difficult to codify the urgency of delivery. Our cohort, despite being limited to

emergency cesarean deliveries, likely contains a range of urgency as demonstrated by the

finding that neonates were delivered in less than 2 minutes in only 25% of our sample. The

subgroup analysis by indication for delivery confirmed longer incision-to-delivery intervals

among women delivered through transverse skin incisions in the situation of cord prolapse,

considered to be perhaps more uniformly urgent than other indications with a more variable

range of urgency.

Although this study validates traditional teaching that abdominal entry is quickest after

vertical skin incision, at least in the setting of large teaching institutions, speed for speeds

sake alone cannot be advocated without addressing whether the identified time difference is

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

clinically significant in improving neonatal outcome without increasing significant maternal

complications. Immediate intraoperative and postoperative maternal complications were

similar between the groups with the primary exception of an increase in postpartum

transfusions for both primary and repeat cesarean deliveries after vertical skin incisions. The

proportion of women undergoing emergent cesarean delivery for hemorrhagic situations

(abruption, previa with hemorrhage) did not differ between the transverse and the vertical

skin incision groups; nonetheless, there are a number of other variables that could affect the

need for postpartum transfusion such as preoperative hemoglobin or intra-operative or

postoperative uterine atony that were not assessed in this analysis. The identified differences

in transfusion rates could be attributable, at least in part, to uncontrolled confounding factors

rather than being a reflection of the skin-incision type. Postpartum endometritis was also

more common after vertical skin incisions in primary cesarean deliveries, although it is

difficult to hypothesize how the incision location might affect this. Again, this may reflect

underlying confounding conditions not controlled for in the analysis linked with both

incision and infection.

Despite a statistically significant difference in incision-to-delivery time by skin-incision

type, neonatal outcomes were not improved among those delivered through a vertical skin

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

incision. In fact, we found improved neonatal outcomes after delivery through a transverse

incision. Our results must be interpreted with caution because our study was limited by its

observational nature and the potential for confounding that would not have been present if

this had been a randomized clinical trial. Women were not randomized to skin-incision type,

and the rationale for why a physician chose a particular skin incision was not captured in the

database. In repeat cesarean deliveries, for instance, we do not know the location of the prior

skin incision and whether this influenced the current incision type.

Despite data being collected contemporaneously to the delivery, our analysis was unable to

quantify the degree of urgency with which an emergency cesarean delivery was performed.

Our data may simply demonstrate that the sickest fetuses were delivered the quickest.

Although transverse incisions were used more frequently than vertical incisions in both

emergent and nonemergent cases, in this cohort, the frequency of vertical incision use was

increased among emergent cases. Perhaps vertical incisions were chosen in the most urgent

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 6

situations, biasing the results toward an apparent time advantage and an apparent neonatal

disadvantage with this approach. Individual surgeon experience was also not assessed and

may have impacted incision choice, swiftness of the delivery interval, and outcome.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

In a separate publication from this registry analyzing the effects of decision-to-incision

intervals on neonatal outcomes in emergency cesarean delivery, adverse neonatal outcomes

were not increased in emergency cesarean deliveries performed more than 30 minutes after

the decision to operate.9 It is therefore not surprising that the additional 1 to 2 minutes saved

by performing vertical skin incisions did not translate into improved newborn outcomes

given the absence of a measurable negative effect with the much longer time intervals in the

decision-to-incision analysis. Nonetheless, in certain emergent situations such as a cord

prolapse without a detectable fetal heart rate or a profound prolonged bradycardia, the

additional 1 to 2 minutes saved by a vertical skin incision could perhaps be significant.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

(HD21410, HD21414, HD27860, HD27861, HD27869, HD27905, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34122,

HD34136, HD34208, HD34210, HD36801).

The authors thank Francee Johnson, BSN, for protocol development and coordination between clinical research

centers; Elizabeth Thom, PhD, for protocol and data management and statistical analysis; and John C. Hauth, MD,

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

for protocol development and oversight.

References

1. Pfannenstiel J. On the advantages of a transverse cut of the fascia above the symphysis for

gynecological laparotomies and advice on surgical methods and indications. Samml Klin Vortr

Gynakol. 1897:6898.

2. Cunningham, FG.; MacDonald, PC.; Leveno, KJ.; Gant, NF.; Gilstrap, LC., editors. Williams

obstetrics. 21. Norwalk (CT): Appleton and Lange; 2001. p. 545

3. Kisielinski K, Conze J, Murken AH, Lenzen NN, Klinge U, Schumpelik V. The Pfannenstiel or so

called bikini cut: still effective more than 100 years after first description. Hernia. 2004; 8:17781.

[PubMed: 14997364]

4. Mathai M, Hofmeyr GJ. Abdominal surgical incisions for caesarean section. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2007; 1:CD004453. [PubMed: 17253508]

5. Hofmeyr GJ, Mathai M, Shah A, Novikova N. Techniques for cesarean section. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2008; 1:CD004662. [PubMed: 18254057]

6. Hetzel H, Bichler A, Geir W, Dapunt O. Cesarean section: low transverse (pfannenstiel) or midline

incision? (authors transl) [German]. Z Geburtshilfe Perinatol. 1979; 183:12835. [PubMed: 35886]

7. Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S, Varner MW, et al. Maternal and

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med.

2004; 351:25819. [PubMed: 15598960]

8. Stokes, ME.; Davis, CS.; Koch, GG. Categorical data analysis using the SAS system. 2. Cary (NC):

SAS Institute Inc; 2000. p. 174

9. Bloom SL, Leveno KL, Spong CY, Gilbert S, Hauth JC, Landon MB, et al. Decision-to-incision

times and maternal and infant outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 108:611. [PubMed: 16816049]

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 7

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of cohort selection.

Wylie. Skin Incision for Emergency Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2010.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 8

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics Among Women Undergoing Emergency Cesarean Delivery by Skin Incision

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Characteristic Transverse Incision (n=2,498) Vertical Incision (n=1,027) P

Age (y) 26.96.8 26.56.7 .10

Body mass index at delivery (kg/m2)* 31.56.8 32.47.6 .02

Race <.001

White 924 (37) 162 (16)

African American 1,162 (47) 421 (41)

Hispanic 278 (11) 406 (40)

Other 134 (5) 38 (4)

Preexisting diabetes mellitus 44 (2) 26 (3) .14

Gestational diabetes 126 (5) 52 (5) .98

Nulliparous 1,216 (49) 439 (43) .002

Data are meanstandard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

*

Data on body mass index at delivery were missing for 9% of the patients162 (6%) patients in the transverse group and 153 (15%) in the vertical

group.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 9

Table 2

Delivery Characteristics Among Women Undergoing Emergency Cesarean Delivery by Skin Incision

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Transverse Incision (n=2,498) Vertical Incision (n=1,027) P

Gestational age at delivery (wk) 37.24.4 37.04.8 1.0

Preterm delivery (less than 37 wk) 821 (33) 343 (34) .71

Birth weight (g) 2,760948 2,721985 .33

Number of prior cesarean deliveries <.001

0 2,107 (84) 830 (81)

1 341 (14) 150 (15)

2 45 (2) 33 (3)

3 or more 4 (0.2) 14 (1)

Indications for delivery .34

Nonreassuring fetal tracing 1,996 (80) 816 (79)

Abruption 199 (8) 71 (7)

Previa with hemorrhage 84 (3) 31 (3)

Cord prolapse 209 (8) 102 (10)

Uterine rupture 10 (0.4) 7 (0.7)

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

*

Data are meanstandard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 10

Table 3

Incision-to-Delivery and Incision-to-Closure Intervals Among Women Undergoing Primary Emergency

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Cesarean Deliveries and Repeat Emergency Cesarean Deliveries

Incision-to-Delivery Interval (min) Incision-to-Closure Interval (min)

Transverse Incision Vertical Incision Transverse Incision Vertical Incision

Primary CD

Sample size* 2,107 830 2,081 826

5.55.2 3.65.1 46.722.3 50.526.1

4 (27) 3 (24) 43 (3355) 46 (3758)

Repeat CD

Sample size* 391 197 382 197

6.85.8 5.15.0 56.428.9 67.949.8

5 (39) 3 (26) 52 (3963) 56 (4575)

CD, cesarean delivery.

Data are n, meanstandard deviation, or median (2575 percentile).

*

Sample size for incision-to-closure intervals smaller than the overall cohort secondary to missing information.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

All P<.001 comparing transverse with vertical incision.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 11

Table 4

Median Incision-to-Delivery Intervals by Indication for Emergency Cesarean Delivery

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Median Incision-to-Delivery Interval (min)

Indication for Emergent CD* Transverse Incision Vertical Incision P

Nonreassuring fetal tracing 1,996 (71) 816 (29) <.001

4 (28) 3 (25)

Abruption 199 (74) 71 (26) .006

4 (26) 3 (25)

Previa with hemorrhage 84 (73) 31 (27) .06

6 (310) 4 (26)

Cord prolapse 209 (67) 102 (33) .04

3 (25) 2 (24)

Uterine rupture 10 (59) 7 (41) .22

4 (27) 2 (13)

CD, cesarean delivery.

Data are n (%) or median (2575 percentile) unless otherwise specified.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

*

Percentages reflect frequency of skin-incision type within each indication subgroup.

P-values from the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 12

Table 5

Selected Maternal Complications Associated With Emergency Cesarean Delivery According to Skin Incision

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Outcome Primary CD Transverse Incision (n=2,107) Vertical Incision (n=830) P

Intraoperative injury* 15 (0.7) 6 (0.7) .97

Postpartum endometritis 237 (11) 124 (15) .006

Wound infection 15 (0.7) 9 (1) .31

Wound hematoma 11 (0.5) 1 (0.1) .20

Ileus 16 (0.8) 8 (1) .58

Postpartum transfusion 102 (5) 60 (7) .01

Length of stay (delivery to discharge) 3.62.3 3.83.2 .23

Repeat CD (n=391) (n=197)

Intraoperative injury* 15 (4) 5 (3) .41

Postpartum endometritis 41 (10) 24 (12) .54

Wound infection 4 (1) 3 (2) .69

Wound hematoma 4 (1) 2 (1) 1.0

Ileus 5 (1) 3 (2) 1.0

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Postpartum transfusion 30 (8) 27 (14) .02

Length of stay (delivery to discharge) 3.51.3 3.92.9 .63

CD, cesarean delivery.

Data are meanstandard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

*

Includes broad ligament hematoma, cystotomy, bowel injury, or ureteral injury.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Wylie et al. Page 13

Table 6

Selected Neonatal Outcomes in Relation to Emergency Cesarean Delivery According to Skin Incision

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Outcome Transverse Incision* (n=2,498) Vertical Incision* (n=1,027) P

5-min Apgar score 3 or less 88 (4) 50 (5) .06

Umbilical artery pH less than 7.0 104 (7) 79 (10) .02

Intubation in delivery room 316 (13) 172 (17) .001

Chest compression 83 (3) 38 (4) .57

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation within 24 h 107 (4) 53 (5) .26

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy 30 (1) 31 (3) <.001

Neonatal death

Total 68 (3) 34 (3) .33

Malformations excluded 47 (2) 22 (2) .58

None of the above 2,039 (83) 790 (78) <.001

*

Data are n (%).

Data on umbilical artery pH were missing for 37% of the neonates, 1,059 (42%) in the transverse group and 242 (24%) in the vertical group.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Includes neonates with 5-minute Apgar scores of 4 or more without intubation in the delivery room, chest compression, cardiopulmonary

resuscitation, hypoxicischemic encephalopathy, or neonatal death.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Obstet Gynecol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Christena Nippert-Eng - Watching Closely - A Guide To Ethnographic Observation-Oxford University Press (2015)Dokument293 SeitenChristena Nippert-Eng - Watching Closely - A Guide To Ethnographic Observation-Oxford University Press (2015)Emiliano CalabazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparison of Obstetric Maneuvers For The Acute Management of Shoulder DystociaDokument7 SeitenA Comparison of Obstetric Maneuvers For The Acute Management of Shoulder DystociaNellyn Angela HalimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparison of Transverse and Vertical Skin Incision For Emergency Cesarean DeliveryDokument7 SeitenComparison of Transverse and Vertical Skin Incision For Emergency Cesarean DeliveryGinecólogo Oncólogo Danilo Baltazar ChaconNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ballon Fluoroscopy As Treatment For Intrauterine Adhesions. A Novel ApproachDokument5 SeitenBallon Fluoroscopy As Treatment For Intrauterine Adhesions. A Novel ApproachAldito GlasgowNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4163-Article Text-41530-4-10-20220105Dokument5 Seiten4163-Article Text-41530-4-10-20220105Redia FalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Episio PDFDokument4 SeitenEpisio PDFEduBarranzuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HHS Public Access: Association of Cervical Effacement With The Rate of Cervical Change in Labor Among Nulliparous WomenDokument12 SeitenHHS Public Access: Association of Cervical Effacement With The Rate of Cervical Change in Labor Among Nulliparous WomenM Iqbal EffendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- EndometritisDokument6 SeitenEndometritisMuh Syarifullah ANoch keine Bewertungen

- Iams 2011Dokument6 SeitenIams 20118jxfv2gc5tNoch keine Bewertungen

- Society For Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology .25Dokument16 SeitenSociety For Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology .25n.i.andy.susantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endometrial Thickness PregnancyDokument12 SeitenEndometrial Thickness PregnancyAgung SentosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Episiotomy in USADokument6 SeitenEpisiotomy in USAFrans Nitu Pa'iNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factores Que Alteran Resutados CX No ObstetricaDokument12 SeitenFactores Que Alteran Resutados CX No ObstetricaMara MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Https:emedicine Medscape Com:article:2047080-PrintDokument5 SeitenHttps:emedicine Medscape Com:article:2047080-Printmiss beeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Etiology of Enterocutaneous Fistula Predicts OutcomeDokument5 SeitenThe Etiology of Enterocutaneous Fistula Predicts OutcomeYacine Tarik AizelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijgo 12787Dokument22 SeitenIjgo 12787Aline Costales TafoyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infertility Management According To The Endometriosis Fertility Index in Patients Operated For EndometriDokument11 SeitenInfertility Management According To The Endometriosis Fertility Index in Patients Operated For Endometricindy.Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Following.11Dokument7 SeitenThe Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Following.11Mara MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coates 2016Dokument2 SeitenCoates 2016FebbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1093@humrep@dex276Dokument7 Seiten10 1093@humrep@dex276Ricky AmeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nejmoa 2303966Dokument11 SeitenNejmoa 2303966Raul ForjanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of The Diagnostic Value of CD138 For ChroDokument8 SeitenAnalysis of The Diagnostic Value of CD138 For ChroAntonio RibeiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supported By: None.: AbstractsDokument1 SeiteSupported By: None.: AbstractsFerry DimyatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CDH ArticolDokument12 SeitenCDH ArticolamasherbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Epulis: Implications For DeliveryDokument3 SeitenPrenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Epulis: Implications For DeliveryRiznasyarielia Nikmatun NafisahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary Cesarean Delivery Practice in The United StatesDokument17 SeitenContemporary Cesarean Delivery Practice in The United StatesdedypurnamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cureus 0010 00000003715Dokument12 SeitenCureus 0010 00000003715widiastrikNoch keine Bewertungen

- APSA Fetal Handbook 2019Dokument92 SeitenAPSA Fetal Handbook 2019Fabrício GonzagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Optimal Timing For Soave Primary Pull-Through in Short-SegmentDokument7 SeitenOptimal Timing For Soave Primary Pull-Through in Short-SegmentNate MichalakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desmarais 2015Dokument4 SeitenDesmarais 2015Jesica DiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unukovych 2016Dokument7 SeitenUnukovych 2016jdavies231Noch keine Bewertungen

- Morbidly Adherent Placenta Treatments and OutcomesDokument15 SeitenMorbidly Adherent Placenta Treatments and OutcomesDara Mayang SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spontaneous Reduction of Intussusception in Infants Is The Glass Half Empty or Half FullDokument4 SeitenSpontaneous Reduction of Intussusception in Infants Is The Glass Half Empty or Half FullWorld Journal of Clinical SurgeryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Age-Dependent Outcomes in Asymptomatic Umbilical Hernia RepairDokument6 SeitenAge-Dependent Outcomes in Asymptomatic Umbilical Hernia RepairAnisaa GayatriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiple Choice Questions in Medical Schools: Saudi Medical Journal December 2000Dokument10 SeitenMultiple Choice Questions in Medical Schools: Saudi Medical Journal December 2000RAJESH SHARMANoch keine Bewertungen

- Fer 1Dokument6 SeitenFer 1Laurensia Liveina HartonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of A Text Messaging-Based Educational Intervention On Cesarean Section Rates Among Pregnant Women in China: Quasirandomized Controlled TrialDokument12 SeitenEffect of A Text Messaging-Based Educational Intervention On Cesarean Section Rates Among Pregnant Women in China: Quasirandomized Controlled Trialforensik24mei koasdaringNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSVD Case Study FinalDokument60 SeitenNSVD Case Study Finaljints poterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Safety During Sedation by Anesthesia ProfeDokument8 SeitenPatient Safety During Sedation by Anesthesia ProfeIsmar MorenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary Patterns of Spontaneous Labor With Normal Neonatal OutcomesDokument13 SeitenContemporary Patterns of Spontaneous Labor With Normal Neonatal OutcomesKathleenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articol 1Dokument7 SeitenArticol 1nistor97Noch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Complications After Caesarean Section: A Population-Based Cohort StudyDokument11 SeitenSurgical Complications After Caesarean Section: A Population-Based Cohort StudyMichael Judika Deardo PurbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Article: Treatment and Outcome For Children With Esophageal Atresia From A Gender PerspectiveDokument7 SeitenResearch Article: Treatment and Outcome For Children With Esophageal Atresia From A Gender PerspectivedaxNoch keine Bewertungen

- cm9 134 1043Dokument9 Seitencm9 134 1043Yudha PramanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recurrent Groin HerniaDokument6 SeitenRecurrent Groin HerniaJohn-adewaleSmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIIS0002937807011209Dokument2 SeitenPIIS0002937807011209Cindy AuliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 IncidenceDokument13 Seiten3 IncidenceRonald Ivan WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corresponding Author. E-Mail:, Twitter: .: Jlinden@bu - Edu @jlinden4Dokument10 SeitenCorresponding Author. E-Mail:, Twitter: .: Jlinden@bu - Edu @jlinden4Marcos ChuquiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric Inguinal Hernia PDFDokument5 SeitenPediatric Inguinal Hernia PDFade-djufrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Postpartum HemorrhageDokument8 SeitenSecondary Postpartum Hemorrhagealin lakoroNoch keine Bewertungen

- J Ajog 2009 10 892Dokument8 SeitenJ Ajog 2009 10 892mapecorelli2626Noch keine Bewertungen

- Verde IndocianinaDokument8 SeitenVerde IndocianinajosebaNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics: Adolf Lukanovi Č, Katarina Dra ŽičDokument4 SeitenInternational Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics: Adolf Lukanovi Č, Katarina Dra ŽičkevindjuandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avitanrg RG RDokument2 SeitenAvitanrg RG RPrasetio Kristianto BudionoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Significance of Primary Symptoms in Women With Placental AbruptionDokument5 SeitenClinical Significance of Primary Symptoms in Women With Placental AbruptionasfwegereNoch keine Bewertungen

- Systematic Review Placenta Calcification and Fetal OutcomeDokument22 SeitenSystematic Review Placenta Calcification and Fetal OutcomeRizka AdiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cesarean Delivery Procedures Recovery AnDokument13 SeitenCesarean Delivery Procedures Recovery AnFitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines For The Management of Postterm Pregnancy: Journal of Perinatal Medicine February 2010Dokument10 SeitenGuidelines For The Management of Postterm Pregnancy: Journal of Perinatal Medicine February 2010Hafif Fitra Alief SultanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apm 20072Dokument7 SeitenApm 20072ida wahyuni mapsanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factores de Riesgo y Resultados de EpisiotomíaDokument19 SeitenFactores de Riesgo y Resultados de EpisiotomíaAlvaro OyarceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frozen Section Pathology: Diagnostic ChallengesVon EverandFrozen Section Pathology: Diagnostic ChallengesAlain C. BorczukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does Tumor Grade Influence The Rate of Lymph Node Metastasis in Apparent Early Stage Ovarian Cancer?Dokument4 SeitenDoes Tumor Grade Influence The Rate of Lymph Node Metastasis in Apparent Early Stage Ovarian Cancer?Herry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparison of Transverse and Vertical Skin Incision ForDokument6 SeitenComparison of Transverse and Vertical Skin Incision ForHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tutorial About Hazard Ratios - Students 4 Best EvidenceDokument10 SeitenTutorial About Hazard Ratios - Students 4 Best EvidenceHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adjuvant Chemotherapy Is Not Associated With A Survival Benefit ForDokument6 SeitenAdjuvant Chemotherapy Is Not Associated With A Survival Benefit ForHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lembar Penilaian Osce Bss1Dokument16 SeitenLembar Penilaian Osce Bss1Herry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Journal of Pharmtech ResearchDokument5 SeitenInternational Journal of Pharmtech ResearchHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTG Classification PDFDokument1 SeiteCTG Classification PDFHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angket Kepuasan Mahasiswa Terhadap Pelayanan Akademik - OfflineeDokument4 SeitenAngket Kepuasan Mahasiswa Terhadap Pelayanan Akademik - OfflineeHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Placental Functions: Associate Professor Iolanda Elena Blidaru MD, PHDDokument40 SeitenPlacental Functions: Associate Professor Iolanda Elena Blidaru MD, PHDHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternal Mortality in 1990-2015Dokument5 SeitenMaternal Mortality in 1990-2015Herry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap44 PDFDokument4 SeitenChap44 PDFHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence Estimates of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in The United States, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2007-2010Dokument9 SeitenPrevalence Estimates of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in The United States, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2007-2010Herry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- By Dr. Malleswar Rao Kasina, MD, Dgo. Hod & CSS, Dept. of Gynobs, Esi Hospital, Sanathnagar, Hyderabad, Ap, IndiaDokument102 SeitenBy Dr. Malleswar Rao Kasina, MD, Dgo. Hod & CSS, Dept. of Gynobs, Esi Hospital, Sanathnagar, Hyderabad, Ap, IndiaHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes During Pregnancy: Li Ruzhi Ob&Gy Hospital, Fudan UniversityDokument41 SeitenDiabetes During Pregnancy: Li Ruzhi Ob&Gy Hospital, Fudan UniversityHerry SasukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mangas PDFDokument14 SeitenMangas PDFluisfer811Noch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting Worksheet Problem 4Dokument19 SeitenAccounting Worksheet Problem 4RELLON, James, M.100% (1)

- Properties of LiquidsDokument26 SeitenProperties of LiquidsRhodora Carias LabaneroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Exploration: Digestive System: Food Inio Simple Nutrien/oDokument9 SeitenStudent Exploration: Digestive System: Food Inio Simple Nutrien/oAshantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Power Control 3G CDMADokument18 SeitenPower Control 3G CDMAmanproxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oral ComDokument2 SeitenOral ComChristian OwlzNoch keine Bewertungen

- BS en Iso 06509-1995 (2000)Dokument10 SeitenBS en Iso 06509-1995 (2000)vewigop197Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDDokument81 Seiten1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDJerome Samuel100% (1)

- Agile ModelingDokument15 SeitenAgile Modelingprasad19845Noch keine Bewertungen

- Advent Wreath Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenAdvent Wreath Lesson Planapi-359764398100% (1)

- Terminal Blocks: Assembled Terminal Block and SeriesDokument2 SeitenTerminal Blocks: Assembled Terminal Block and SeriesQuan Nguyen TheNoch keine Bewertungen

- ULANGAN HARIAN Mapel Bahasa InggrisDokument14 SeitenULANGAN HARIAN Mapel Bahasa Inggrisfatima zahraNoch keine Bewertungen

- LavazzaDokument2 SeitenLavazzajendakimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Will Smith BiographyDokument11 SeitenWill Smith Biographyjhonatan100% (1)

- Dissertation 7 HeraldDokument3 SeitenDissertation 7 HeraldNaison Shingirai PfavayiNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEC CS Spice Money LTDDokument2 SeitenSEC CS Spice Money LTDJulian SofiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building A Pentesting Lab For Wireless Networks - Sample ChapterDokument29 SeitenBuilding A Pentesting Lab For Wireless Networks - Sample ChapterPackt PublishingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engine Controls (Powertrain Management) - ALLDATA RepairDokument3 SeitenEngine Controls (Powertrain Management) - ALLDATA RepairRonald FerminNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAO-Assessment of Freshwater Fish Seed Resources For Sistainable AquacultureDokument669 SeitenFAO-Assessment of Freshwater Fish Seed Resources For Sistainable AquacultureCIO-CIO100% (2)

- Course Projects PDFDokument1 SeiteCourse Projects PDFsanjog kshetriNoch keine Bewertungen

- PH of Soils: Standard Test Method ForDokument3 SeitenPH of Soils: Standard Test Method ForYizel CastañedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MECANISMOS de Metais de TransicaoDokument36 SeitenMECANISMOS de Metais de TransicaoJoão BarbosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geometry and IntuitionDokument9 SeitenGeometry and IntuitionHollyNoch keine Bewertungen

- LG Sigma+EscalatorDokument4 SeitenLG Sigma+Escalator강민호Noch keine Bewertungen

- CSEC SocStud CoverSheetForESBA Fillable Dec2019Dokument1 SeiteCSEC SocStud CoverSheetForESBA Fillable Dec2019chrissaineNoch keine Bewertungen

- 100 20210811 ICOPH 2021 Abstract BookDokument186 Seiten100 20210811 ICOPH 2021 Abstract Bookwafiq alibabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protection in Distributed GenerationDokument24 SeitenProtection in Distributed Generationbal krishna dubeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual: Functional SafetyDokument24 SeitenManual: Functional SafetymhaioocNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Piano Lesson Companion Book: Level 1Dokument17 SeitenThe Piano Lesson Companion Book: Level 1TsogtsaikhanEnerelNoch keine Bewertungen