Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rutes2001 PDF

Hochgeladen von

madhaviOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rutes2001 PDF

Hochgeladen von

madhaviCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HOTEL DESIGN GUEST-ROOM FLOORS

and support spaces on the lower floors may be

the most critical consideration. Two major plan-

ning requirements often dictate both the shape

Guest-room planning objectives

and the placement of the guest-room structure

on urban sites. Those requirements are the pre-

Siting and orientation ferred location of the public and service eleva-

l Site the guest-room structure to be visible from the road. tors and of the column-free ballroom. At resort

l Orient guest rooms to enhance views. properties, on the other hand, the opposite is true:

l Assess the relative visual impact and construction cost of various guest-room

configurations. the functional organization of the hotel’s elements

l Position the guest-room structure to limit its structural impact on the ballroom is secondary to the careful siting of the buildings

and other major public spaces. to minimize their impact on the site and to pro-

l Consider solar gain; generally north-south exposures are preferable to east-west

vide views of the surrounding landscape or beach.

exposures.

Many resorts feature not a single building but,

Floor layout instead, provide a number ofvilla structures that

greatly reduce the perceived scale of the project,

l Organize the plan so that the guest rooms occupy at least 70 percent of gross

floor area. give the guest a greater connection to the site

. Locate elevators and stairs at interior locations to use the maximum possible and the recreational amenities, and enhance the

length of outside wall for guest rooms. sense of privacy. At airport sites, height limita-

l Develop the corridor plan to facilitate guest and staff circulation.

tions often dictate the choice of a specific plan-

l Place the elevator lobby in the middle third of the structure.

l Place the service elevator, linen storage, and vending in a central location. one that packages the rooms into a relatively low

l Plan corridor width at a minimum of 5’ 0” (1.5 m), but consider the option of and spread-out structure.

5’ 6” (1.65 m). While the choice of an architectural plan is a

l Design guest bathrooms back-to-back for plumbing economies.

function of a balanced consideration of site, en-

l Locate handicap-access guest rooms on lower floors and near elevators.

vironment, and program requirements, the ar-

chitect must realize that a particular configura-

taking into account constraints and opportuni- tion will shape the economics of the project. Not

ties of a particular site, may initially select a only does the type of plan drive budgetary is-

double-loaded corridor configuration (i.e., one sues-including the cost of initial construction;

with rooms on either side), a compact vertical furniture, fixtures, and equipment (FF&E); and

tower, or a spacious atrium structure-each with ongoing energy and payroll expenses-but the

its myriad variations. Low-rise properties gener- choice of a plan also influences the more subtle

ally are planned using a double-loaded corridor aspects of guest satisfaction. The design that is

and may be shaped into an L, most economical to build, for instance, may not

a T, a U, or a +, among other configurations. provide the best (i.e., most profitable) design so-

High-rise buildings may follow those patterns; lution. A relatively less efficient (and, thus, more

they can be terraced into pyramid-like forms; or expensive) plan type may offer more variety in

they can adjoin a large lobby space so that some room types than an efficient construction design,

of the rooms look into the hotel’s interior. The as well as afford a more interesting spatial se-

tower plan, in which the guest rooms surround a quence, shorter walking distances, and other ad-

central core, can be practically any shape, al- vantages that affect the guest’s perception of the

though rectangular or circular are most common. value of the hotel experience.

Early atrium configurations, such as that of John

Portman’s Hyatt Regency Atlanta, were designed Analyzing Alternative Configurations

on a basic rectangular plan. More recent projects For an operator to realize profits, the design team

have taken on numerous, complex shapes. The must maximize the percentage of floor area de-

various configurations are illustrated throughout voted to guest rooms and keep to a minimum

Photograph on this article. the amount of circulation and service space (e.g.,

previous page:

The most appropriate configuration for the service-elevator lobby, linen storage, vending, and

Hotel Rey Juan Carlos I,

Barcelona, Spain. guest rooms depends largely on the nature of the other minor support spaces). Although the ar-

This luxury hotel places its building site. In densely populated urban areas, chitect and developer must not ignore aesthetic

370 guest rooms in two

opposing wings separated

where land costs are high and the site may be and functional issues, a simple comparison

by a ICstory-high atrium. relatively small, the ideal arrangement of public among alternative plans of the percentage of space

78 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly AUGUST 2001

GUEST-ROOM FLOORS HOTEL DESIGN

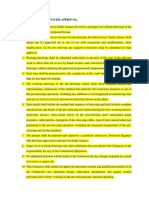

Guest-room floor analysis

Rooms Dimensions Guest-room Corridor area

Configuration per floor ft (m) percentage per room, ff (m2) Comments

Sing/e-loaded slab Varies by site 32 (10) x 65% 80 Vertical core usually not affected

size: 1Z-30+ available length (7.5) by room module.

Double-loaded slab Varies by site 60 (18) x 70% Economical length limited by exit-

size: available length stair placement to meet building

16-40+ code.

Offset slab Varies by site 80 (24) x 72% 50 Core is buried, creating less perim

size: available length (4.6) eter wall per room; more corridor

24-40+ because of elevator lobby.

Rectangular tower 16-24 110x110 65% 60 Planning issues focus on access to

(34 x 34) (5.6) corner rooms; fewer rooms per

floor make core layout difficult.

I I I

Circular tower 16-24 90-130 diameter 67% 45-65 High amounts of exterior wall per

(27-40) (4.2-6) room; difficult to plan guest

bathroom.

Triangular tower 24-30 Varies 64% 65-85 Central core inefficient due to

(6-7.9) shape; corner rooms easier to plan

than with square tower.

Atrium 24+ 90+ 62% 95 Open volume creates spectacular

(27) (8.8) space, open corridors, opportunity

for glass elevators; requires careful

engineering for HVAC and smoke

evacuation.

Each guest-room floor configuration has certain characteristics that For example, the table shows that the offset double-loaded slab is

affect its potential efficiency. This table shows the basic building the most efficient in terms of guest-room-area percentage and that

dimensions, the usual percentage of floor area devoted to guest the atrium configuration is the least economical, largely because of

rooms, and the amount of area per room needed for corridors. the high amount of corridor area required per room.

AUGUST 2001 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 79

HOTEL DESIGN GUEST-ROOM FLOORS

allocated to guest rooms versus non-revenue-

producing space can suggest a set of efficient so-

Slab configurations lutions. The major alternatives among plan types

are described in Exhibit 2 (on the previous page).

Our analysis of hundreds of different guest-

room floor plans shows that some patterns yield

more cost-effective solutions than others. The

choice of one configuration over another can

Single-loaded slab

mean a savings of 20 percent in gross floor area

of the guest-room structure and of nearly 15 per-

cent in the total building. For example, the three

principal plan alternatives-the double-loaded

slab, the rectangular tower, and the atrium-

when designed with identical guest rooms of 350

net sq. ft. (32.5 m2), yield final designs that vary

from about 470 to 580 gross sq. ft. (44 to 54 m’)

per room.

Double-loaded slab Our study also indicates the effect of subse-

quent minor decisions on the efficiency of the

plan-pairing two guest rooms back-to-back, for

example, or choosing a double- or single-loaded

corridor, grouping public and service elevators,

and planning efficient access to end or corner

rooms. Because guest rooms account for so much

total hotel area, the architect should establish a

series of quantitative benchmarks for the efficient

design of the guest-room floors. For example, one

Double-loaded slab approach is to set a goal of the median guest-

room percentage figure, say, 70 percent for the

double-loaded slab. In that case, if the gross area

isn’t more than 1.42 (the reciprocal of the .70

figure) x the net area, then the plan is relatively

efficient.

The relative efficiency of typical hotel floors

can be compared most directly by calculating the

percentage of the total floor area devoted to guest

Double-loaded slab

rooms. This varies from below 60 percent in an

inefficient atrium plan to more than 75 percent

in the most tightly designed double-loaded slab.

Clearly, the higher this percentage, the lower the

set slab

construction cost per room. In turn, a relatively

low construction cost offers the developer a range

of options: build additional guest rooms, pro-

vide larger guest rooms for the same capital in-

vestment, improve the quality of the furnishings

or of particular building systems, expand other

functional areas such as meeting space or recre-

ational facilities, or lower the construction cost

Single-loaded plans (top), while more costly, are sometimes necessary for and project budget.

narrow sites or to take advantage of views. Double-loaded plans (center)

The following sections describe the planning

show paired back-to-back bathrooms and offer the most-efficient options for

elevator cores, exit stairs, and servrce functions. Offset-slab plans (bottom) decisions that have the most influence on creat-

offer efficiency of interior core as well as more variety in the facades. ing an economical plan for each of the basic guest-

80 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly AUGUST 2001

GUEST-ROOM FLOORS 1 HOTEL DESIGN

room configurations. In some plans, the key fac- cially economical because the public and service

tor is the number of rooms per floor, while in elevator cores share one area and, in addition,

others the driving factor is the location of the they do not displace any guest rooms from the

elevator core or the shape of the building. In gen- building perimeter. The knuckle configuration,

eral, the most efficient configurations to con- which bends at angles, creates the potential for

struct and operate are those where circulation interestingly shaped elevator lobbies, provides

space is kept to a minimum-either the double- compact service areas, and breaks up the slabs

loaded corridor slab or the compact center-core long corridors.

tower. The core design is complicated by the need to

connect the public elevators to the lobby and the

Slab Configuration service elevators to the housekeeping and other

The slab configuration includes those plans that back-of-house areas. This often necessitates two

are primarily horizontal, including both single- distinct core areas at some distance from each

and double-loaded corridor schemes (as shown other, although in many hotels those areas are

in Exhibit 3). The few planning variables are con- located side by side. One common design is to

cerned primarily with the building’s shape position the elevator core in the middle third of

(straight, L-shaped, or other), the layout of the a floor to reduce walking distances to the far-

core, and the position of the fire stairs. The ar- thest rooms. Most often the vertical core is fully

chitect must consider the following issues relat- integrated into the body of the tower, but the

ing to a slab pattern. designer may occasionally add the core to the end

l Corridor loading. Given site conditions, of a compact room block or extend it out from

are any single-loaded rooms appropriate? the face of the fa$ade.

l Shape. Which particular shape (e.g.,

straight, L, courtyard) best meets site and

building constraints?

The hotel’s core design is complicated

l Core location. Should the public and the

service cores be combined or separated, and

where in the tower should they be by the need to connect the public

positioned?

l Core layout. What is the best way to orga- elevators to the lobby and the service

nize public and service elevators, linen stor-

elevators to back-of-house areas.

age, vending, and other support areas?

l Stair location. How can the exit stairs best

be integrated into the plan?

The high degree of efficiency found in the

slab plan arises primarily from double-loaded The final layout of the core is another factor

corridors. Single-loaded schemes, in contrast, re- that determines a plan’s efficiency. In most slab-

quire 5- to 8-percent-more floor area for the same plan hotels, the vertical cores require space equiva-

number of rooms. Therefore, one should em- lent to two to four guest-room modules. One goal

ploy a single-loaded design only where external is to keep the core to a minimum, and the plan’s

factors militate, such as a narrow site dimension efficiency improves when the core displaces the

or the availability of spectacular views in one smallest number of guest-room bays. Our com-

direction. parison of many projects shows that the vertical

While slab plans constitute the most efficient core displaces fewer guest-room bays when the

design category, various approaches can never- service areas are located behind the public eleva-

theless further tighten the layout. Configurations tors than when those areas are beside or at some

that bury the elevator and service cores in inte- distance from the public elevators. Many of the

rior corners, for instance, accomplish this task. more efficient configurations also feature a dis-

They reduce the non-guest-room area, reduce the tinct elevator lobby. Such a foyer space helps to

building perimeter, and increase the opportuni- isolate nearby guest rooms from the noise and

ties for creating architecturally interesting build- congestion of people waiting for the elevator.

ings. The offset-slab plan, for example, is espe- Also, plans that incorporate an elevator lobby gen-

AUGUST 2001 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 81

HOTEL DESIGN GUEST-ROOM FLOORS

erally have fewer awkwardly shaped rooms,

thereby providing a more uniform guest-room

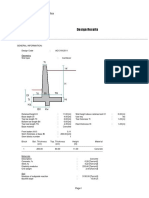

Tower configurations design.

Building codes generally require emergency-

exit stairs to be located at opposite ends of the

building. Each such stair tower might simply re-

place the last guest room on the corridor. But,

instead, the architect may be able to integrate

the stairs within the building, as part of an eleva-

tor core, at an “inside corner” where the build-

ing turns, or within the usual bathroom zone of

a guest-room bay (where the bathroom is part of

an oversized room or suite). Careful placement

Prnwheel Cros

of the stairs provides one more opportunity to

create a more efficient overall plan by reducing

gross floor area, compared with simply attaching

the stair tower to the end of the building.

One factor that limits the number of rooms

on the guest-room floor is the typical code re-

quirement for hotels with automatic sprinklers

that there be no more than (typically) 300 ft.

(91 m) between exit stairs. Therefore, another

goal in planning the repetitive guest-room floor

is to create a layout that does not require a third

fire stair. Experienced hotel architects have es-

Sauare iuare tablished techniques for maximizing the num-

ber of rooms per floor and manipulating the stairs

and corridors to increase the building’s overall

efficiency.

Tower Configuration

Tower plans are the second major category of

guest-room-floor layouts (as shown in Exhibit 4).

These generally comprise a central core sur-

rounded by a single-loaded corridor of guest

rooms. The tower’s exterior architectural treat-

ment can vary widely, depending on the geomet-

ric shape of the plan (e.g., square, cross-shaped,

circular, triangular). Tower plans exhibit differ-

Circular Triangular ent characteristics than those of the slab, but tow-

ers still raise a similar series of questions for the

designer:

Pinwheel plan (top, left) accommodates all typical rooms but requrres Number of rooms: How many guest rooms

extra corridor. Cross-shape plan (top, right) reduces corridor but in- economically fit a particular layout?;

creases building perimeter. Square towers of the type shown (center,

Shape: Which shape is most efficient and

left) feature efficient circulation, back-to-back bathrooms, and suite

options at corners. The square tower (center, right) provides for the permits the desired mix of rooms?;

most corner guest rooms and minimal circulation. Circular tower Corridor: How is hallway access to corner

(bottom, left) offers minimum area and perimeter but substantially rooms arranged?; and

smaller bathrooms. Triangular tower (bottom, right) has a less-

Core layout: How are the elevators, linen

efficient core, but added variety of room shape.

storage, and stairs organized?

Unlike the other plan configurations, selec-

tion of the tower shape creates specific limita-

82 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly AUGUST 2001

GUEST-ROOM FLOORS HOTEL DESIGN

About This Book

With the growth in world travel in recent years, business and pleasure tant design issue for many resort properties. Succeeding chapters detail

travelers are demanding more diverse hotels, resorts, and leisure-rime the key design guidelines for the functional areas in hotels: the guest-

amenities around the globe. The accompanying article, “Planning the room floor (excerpted here); guest rooms and suites; lobby, food and

Guest-room Floor,” is excerpted from Hotel Design, Planning, and beverage, meeting, and recreational areas; and administration and back-

Development, published earlier this summer by W.W. Norton in the of-house areas. The Design Guide concludes with a discussion of spe-

United States and the Architectural Press in the United Kingdom. cial building - systems and construction methods important to the whole

A total revision of our 1985 book, Hotel Planning and De&h, the range of hotel properties.

new volume explores the latest trends

in hotel and resort architecture, estab- To develop a successful hotel, its princi-

lishes a wide range of planning and pals must be familiar with more than just

design criteria, and discusses key devel- the distinct variety of hotel types and the

opment issues. In addition to extensive design criteria outlined in Parts 1 and 2.

photographs and scores of plans and The developers must also be familiar with

checklists, the book features a three- the development process irself and how

part foreword by architect Gyo Obata, the many financial, operational, market-

designer Michael Bedner, and industry ing, and organizational objectives of an

consultant Bjorn Hanson, as well as owner and developer influence the

commentary from I.M. Pei, John C. project and its prospect for success (as

Portman, Jr., Robert A.M. Stern, Ian found in Part 3, the Development

Schrager, Robert E. Kastner, Valentine Guide). If those objectives are in balance

A. Lehr, and Howard J. Wolff. with demand for hotel facilities, with the

site’s capacity to support a hotel or resort,

The Book at a Glance and with the programmatic and design

Part 1, Hotel Types, reviews more decisions, the project can prosper.

than 50 different types of hotels now

flourishing in today’s increasingly cus- The chapters in this third section trace

tomized marketplace, where concepts the hotel-development process beginning

range from theme resorts to efficient with the initial concept of developing a

extended-stay properties, and from lodging property. The process includes a

high-fashion boutique hotels to flexible number of key steps: analyzing feasibility,

office suites. Separate chapters are de- assembling the development and design

voted to each of I2 major categories. team, establishing the building program,

For example, suburban hotels comprise and managing the budget, schedule, and

many design types, including airport the hotel opening. In addition, the team

hotels, office-park hotels, mall or uni- should understand the issues of hotel

versity hotels, roadside hotels, and country inns. Resorts encompass operation and how the planning and design decisions influence many

an ever-widening array as unique as the ecotourist retreat or vacation of the practical and technical aspects of running a hotel. This allows the

village is from the convention resort. Many owners update existing team to consider solutions that effectively reduce staff numbers or ac-

hotels, reinventing their ambiance through innovative renovations, commodate important life-safety or mechanical requirements.

restoration, additions, or adaptive reuse.

Finally, the book considers lodging’s future, including the prospect of

This section begins with an overview that traces the hotel’s evolution increasing numbers of focused niche-lodging types, broad socioeco-

and offers the latest forecasts of its future development. It also features nomic trends, or creative proposals for new resorts under the sea or in

an evolutionary-tree diagram of hotels, another theme threading outer space. The future is wide open. With truly collaborative partner-

rhrough these chapters. Each hotel type is clearly addressed in terms ships among developer, design team, and operator the industry should

of development considerations, planning and design options, social see a continued explosion of creative hotels and resorts in the twenty-

and cultural implications, and future trends. (Those trends are sum- first century-mA.R, R.H.I?, andL.A.

marized in the final chapter of the book.) A continuing theme is the

emphasis on strongly targeting specific market sectors, so that the Together the authors have many decades’ experience comprising three

hotel may better fulfill its function. For example, luxury resorts and long careers in hotel design and development. Before founding 9 Tek

Ltd., Walter A. Rutes was vice president and director of architecture at

super-luxury hotels need small, superb restaurants and health spas to

such major hotel companies as Inter-Continental, Sheraton, Ramada,

maintain their clientele.

and Holiday Corporation. At Cornell University, Richard H. Penner

teaches courses in hotel development, planning, and interior design.

Part 2, the Design Guide, focuses on the program, planning, and He also is the author of Conference Center Planning and Design.

design issues critical to creating a successful lodging property. This Lawrence Adams has specialized in hotel design and large-scale

section highlights the types of operational and financial decisions that developments at major architectural and planning firms including

affect and influence the architectural and interior design. The first HOK, William B. Tabler, S. Stuart Farnet, and Frank Williams and

chapter introduces site and master planning, perhaps the most impor- Associates.

AUGUST 2001 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 83

HOTEL DESIGN GUEST-ROOM FLOORS

tions on the number of rooms per floor. For the

most part, towers can accommodate between 16

Atrium configurations and 24 rooms, depending on the guest-room di-

mensions, the number of floors, and the opti-

mum core size. With only 16 rooms, the core

would barely be large enough for two or three

elevators, two egress stairs, and minimum

amounts of storage. On the other hand, designs

with more than 24 rooms become so inflated and

the core so large that the layout becomes highly

inefficient.

The efficiency of most guest-room configura-

tions improves as the number of rooms on a floor

increases, with little or no expansion in the core

or building-service areas. With the tower plan,

the opposite is true. The analysis of a large sample

of hotel designs shows that, surprisingly, the fewer

the number of rooms per floor, the more eff-

cient the layout. This is true because the core, by

necessity, must be extremely compact and, as a

result, the amount of corridor area is kept to a

bare minimum. Ineffrcient layouts, on the other

hand, often result from adding rooms and from

extending single-loaded corridors into each of the

building corners.

The shape of the tower has a direct effect on

the structure’s appearance and perceived scale.

The efftciency of the plan is also a direct result of

the shape, because of the critical nature of the

corridor access to the corner rooms in the rect-

angular towers and the design of the wedge-

shaped guest room and bathroom in the circular

towers. Those plans that minimize the amount

of circulation and, in addition, create unusual

corner rooms exemplify the best in both archi-

tectural planning and interior layout.

For circular tower plans, the measures of effi-

ciency are judged by the layout of the room, in

addition to the core design. Typically, the perim-

eter of the wedge-shaped guest rooms is about

16 ft. (4.9 m), whereas the corridor dimension

may be less than 8 ft. (2.4 m), thus challenging

the designer’s skill to plan the bathroom, entry

vestibule, and closet.

While the design of the core in both rectan-

gular and circular towers is less critical than the

Typical atrium (top) features scenic elevators and single-loaded balcony corri- arrangement of guest rooms, certain specific is-

dors. Hybrid atrium plan (bottom) combines visual excitement of atrium sues have to be resolved. Generally, the core is

space with more efficient double-loaded slab extension (as found in the Hyatt

centrally located, and the vertical elements are

Regency Dallas, designed by Welton Becket Associates).

tightly grouped. Small hotels (i.e., those with only

I6 rooms per floor) usually do not feature an

84 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly AUGUST 2001

GUEST-ROOM FLOORS HOTEL DESIGN

elevator lobby, and the guests in rooms opposite as well as add animation to the space itself. In

the elevators must tolerate noise from guests wait- some cases, scenic elevators are placed opposite

ing for the elevator. In a few cases, the core is conventional ones, creating two distinct experi-

split into two parts, creating roughly an H- ences for the guest. The location of the service

shaped circulation zone, effectively providing an elevators, housekeeping-support functions, and

elevator lobby on each floor. The two fire stairs emergency-exit stairs, while needing to be inte-

can be efficiently arranged in a scissors configu- grated into the plan, are not particularly critical

ration (if permitted by code) to conserve space. to the efficiency of the guest-room floor.

In tower plans with 24 or more rooms per In addition to the open lobby, each atrium

floor, the central core becomes excessively large. hotel is distinguished by the plan of the guest-

Some hotel architects introduce a series of multi- room floors. While the basic prototype is square,

story “sky lobbies” to make this space a positive many of the recent atrium designs are irregularly

feature, or add conference rooms on every guest shaped to respond to various site constraints. This

floor. The efficient design of hotel towers requires sculpting of the building contributes to creating

the simultaneous study of the core and an imagi-

native layout to meet the demand for ultra-high-

rise mixed-use structures.

Atrium Configuration The efficiency of most guest-room

Atriums constitute the third major category of

guest-room floor plans (see Exhibit 5). As we configurations improves as the

mentioned above, the present-day atrium design

number of rooms on a floor increases.

was introduced by architect John Portman for

the Hyatt Regency Atlanta in 1967. The atrium

prototype had been used successfully late in the

nineteenth century in both Denver’s Brown Pal-

ace (still in operation) and San Francisco’s first

Palace Hotel, which was destroyed in the 1906 a distinctive image for the hotel, which is a pri-

earthquake and fire. By far the least efficient of mary goal in selecting the atrium configuration.

the plans we are highlighting here, the generic Recognizing the atrium’s inefficiency, archi-

atrium configuration has the guest rooms ar- tects have sought ways to gain the prestige ben-

ranged along single-loaded corridors, much efits of the atrium while increasing its efficiency.

like open balconies overlooking the lobby space. One technique that has been successful in sev-

The following issues must be addressed by the eral hotels is to combine a central atrium with

architect: extended double-loaded wings, as was done at

Shape: What configuration of rooms best the Hyatt Regency hotels in Cambridge (Massa-

fits the site and can be integrated with both chusetts) and Dallas. This approach effectively

public and back-of-house area needs?; draws together the architectural excitement of the

Guest-room location: Should any guest atrium space (on a smaller and more personal

rooms look into the lobby?; scale than in the large hotels) with the desirable

Public elevators: How are scenic or economies of the double-loaded plan. However,

standard elevators best arranged?; many developers and architects believe that the

Corridor: How can the amount of atrium design has become a cliche-and also rec-

single-loaded corridor space effectively ognize its tremendous cost premium-and seek

be reduced?; and other means to create a memorable building and

Service core and stairs: Where are service guest experience.

areas best located and integrated into the

building design? Defining the Guest-room and Suite

Practically all atrium hotels feature glass-en- Program

closed elevators that provide the guest with an After the architect establishes the conceptual de-

ever-changing perspective of the lobby activity, sign, including a basic configuration for the guest-

AUGUST 2001 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 85

HOTEL DESIGN GUEST-ROOM FLOORS

Typical guest-room program for a 300-room hotel

Room type Commtsnts

King 350 (32.5) 120 1 120 42,000 (3,900) -

Double-double 160 -

Parlor 350 (32.5) 6 1 6 2,100 (195) jet-bare connects to K and DD

-,*,:.“;,;.,,).

“:, ._“I~-’ Z,,“G‘:

Hospitality suite f.:; ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~;~:~ Kitchen; connects to K and DD

Conference suite 700 (65) 4 2 a 2,600 (260) Boardroom; connects to K and DD

;; ‘ .‘ ..:; ;. ; .*;. ,a,*. ,“/3.,

Deluxe suite .~~~~?~~:~~~~~~~~,’ 3 9 ~~~~~,~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Connects to K and DD

.:..

Presidential suite 1,400 (130) 1 4 4 1,400 (130) Connects to dedicated K and DD

C o n c i e r g e club ,~‘~j~~~~~~~~,~. 0 ;_ :.;,,, )* / ,‘~< -.:’ -~:~~

; I ~.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ .:, fnctode pantry, conference room

,_ ,:-.-“*:, .<‘,.’ ;:

Totals: 300 321 113,050 (10,500)

* Unit area and total net area given in ft* (m*)

room floors, the team needs to refine and modify lStructural bay: The dimension between

the earlier thumbnail guest-room program to fit two structural columns, typically equal

the architectural concept-or shape the build- to the width of one or two guest rooms; and

ing to accommodate the nuances of the program. lSuite: Combination of living room and

The room mix is based on the initial market study one or more bedrooms.

and, more important, on the advice and experi- Generally, a hotel’s management thinks in

ence of the hotel-operating company. The guest- terms of keys, or the total number of individual

room program defines the typical room module guest-room units available for sale. A suite con-

(key dimensions and bathroom configuration), taining a living room that connects to two bed-

the mix of room furnishings (e.g., single king bed, rooms totals three keys if the parlor has a full

two double beds), and the variety of suites. The bathroom and convertible sofa and the bedrooms

proposed room mix is intended to reflect the es- can be locked off. But the same arrangement is

timated demand from the individual business, only two keys if the living room cannot function

group, and leisure market segments. as a room on its own and must be sold with one

Design development of the guest-room floors bedroom. Large suites often are described in terms

to meet the specific requirements of the program of the equivalent number of guest-room bays so

is among the earliest steps in refining the con- that a hotelier may refer to a four-bay suite con-

ceptual design. The design team studies a wide taining a two-bay living room and two connect-

range of possible modifications, including chang- ing bedrooms. Architects, on the other hand, of-

ing the width of the guest-room module, the ten refer to the individual rooms and to structural

number of bays per floor, the location and lay- bays, the former being the basis of the contract

out of the elevator and service cores, and the ar- documents and the latter a chief component of

rangement of suites. To avoid misunderstandings, cost estimates for the guest-room portion of the

the following definitions should be used: hotel.

Key: A separate, rentable unit;

l During the development phases, feasibility

Guest-room bay: The typical guest-room

l consultants project revenues and expenses, occu-

module; pancy percentages, and average room rates based

86 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly AUGUST 2001

GUEST-ROOM FLOORS HOTEL DESIGN

Guest-room-mix analysis

e m

K

8

The guest-room-floor plans above illustrate the procedure for analyzing l Connecting rooms: Mark interconnecting rooms with an open circle,

the architectural planning and room layout for a hypothetical hotel. The for example between rooms 15 and 17. Operating companies seek a

plans show the typical floor and suite floor, the latter with five different specific number of connecting pairs of particular types (for example,

room types-not unusual, as the standard room bay is modified to fit half the pairs connect K to DD).

around elevators, stairs, or support areas. The number of different

room types is increased further by handicap-accessible rooms and by l Suites: Position all suites, combinations of a living room and one or

various suites. The following discussion describes the necessary steps more adjoining bedrooms, within the typical room configuration. Two

including key plans for each floor, labeled with room shape, bed type, suites are shown in the example: a conference suite in the corner that

room number, and connecting doors, and a comprehensive tally of the connects to a standard double-double room, and a VIP suite that con-

guest-room mix. nects to two bedrooms. The VIP suite also counts as a key, or rentable

unit, because it has a full bathroom and a convertible sofa. Often, the

l Architectural shape: Identify each room of a different shape or con- suites are grouped together on the top guest-room floors.

figuration (primarily different dimensions or bathroom layout) and

assign it a number. Different room types are identified by a Roman l Room numbers: Assign room numbers to the bays to meet the man-

numeral in the top half of the circular code in each room. Room I is the agement company’s eventual operating requirements. Doing this in

most typical; room II is similar but has a different configuration at the schematic design greatly aids communication among the various design

entry vestibule; room III is the corner guest room with a wider bay and professionals and reduces later confusion if the operator were to modify

different bathroom; room IV is a two-bay conference suite (only one the room numbers. Determine room numbers to simplify directional and

key); and room V is a two-bay living room that connects to two stan- destination signs; maintain corresponding numbers on different floors.

dard guest rooms.

l Key and bay analysis: Develop a summary table to tally the number of

l Bed type: Label each room by its bed type (king, queen, double- rentable ‘keys’ and room modules for each floor by architectural shape

double, twin, king-studio, parlor, handicap-accessible) and place a or bed type. The table next to each plan cross-references the number of

simple abbreviation (e.g., K, Cl, DO) on the plan. Note that the standard room types (I-V) and the bed types for each floor. Frequently, a larger

room type may be furnished in a variety of ways. chart is developed for the entire hotel showing the stacking of typical

and suite floors and providing totals of the number of rooms for each

type.

AUGUST 2001 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 87

on the number and type of guest-room keys. In Exhibit 7 illustrates one typical approach for

addition, both parking requirements and zoning documenting the guest-room mix. The technique

ordinances (used to control project size and den- presented here forces the architect or interior de-

sity) are usually based on the key count. How- signer to make a number of conscious decisions:

ever, clarification is essential to avoid possible Architectural shape: Categorize each

misunderstandings and delays. Exhibit 6 illus- room by its shape or conftguration;

trates an example of a typical guest-room and suite Bed type: Label each room by its bed

program and the use of the terms “key” and “bay.” type;

Connecting rooms: Indicate adjoining

lk~cumenting the Guest-room Mix guest rooms;

Throughout the late design phases the architect Suite locations: Position and label any

and other design-team members continually suites;

modify details of the guest-room structure, in Guest-room numbers: Assign final

response to the owner’s or operator’s input, or as room numbers; and

the result of changes in the public and service Key and bay analysis: Develop and

areas on the lower floors. But often changes in maintain a summary table of keys and

the guest rooms occur when the designs are bays by architectural shape or bed type.

fleshed out for the building’s mechanical and elec- Documenting the room count confers a num-

trical distribution systems, elevator cores, or stair ber of advantages. To begin with, the design team

towers. Because it is important that the team be can test the schematic design against the major

able to keep an accurate count of the total bays element in the space program-the required

and keys, the architect or interior designer should number of guest rooms-and initiate any neces-

prepare and regularly update a guest-room-mix sary changes at the earliest point in the concep-

analysis. tual design. Second, the documentation estab-

lishes a format that allows the designers readily

to analyze the guest-room mix and maintain a

precise record of the guest-room count through

the later design phases. Third, details of the re-

petitive guest-room block can be considered at a

relatively early phase. For example, the architect

can study possible pairing of rooms to increase

the number of back-to-back bathrooms and to

establish a repetitive pattern of setbacks at the

guest-room doors. Finally, the interior designer

can identify any potential problems, such as odd-

shaped rooms, that might not easily accommo-

date the necessary furnishings and amenities. In

addition, other members of the team can offer

better input when changes to the guest-room

tower are fully documented through the differ-

Walter A. Flutes Richard H. Penner, MS.,

ent design phases. For instance, the engineering

A teacher of hotel design

(not pictured). FAIA, is is a professor of property- at New York University, consultants can review the major systems in the

chair of 9 Tek Ltd., a asset management at the Lawrence Adams is an guest-room tower-the elevators, HVAC, and

hotel-design consulting Cornell University School architect in New York City

firm (TekSLtd@aol.com). of Hotel Administration (lawadams@aol.com). communications systems, for example-in the

(rhpZ@cornell.edu). same context as the rest of the design team.

98 Cr)rrlell HoleI anti Restaurant Aclmrnrstratron Quarterly AUGUST 2001

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- En 14351-1+A1 Caixilharia Janelas e PortasDokument71 SeitenEn 14351-1+A1 Caixilharia Janelas e PortasearpimentaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3-24-4 Vibracast Refractory LiningDokument38 Seiten3-24-4 Vibracast Refractory LiningPierre Ramirez100% (1)

- Dedesign Consideration For City HallDokument8 SeitenDedesign Consideration For City HallShawul Gulilat50% (4)

- Site Location: 12 KMS Fort St. George 12 KMS Fort St. GeorgeDokument3 SeitenSite Location: 12 KMS Fort St. George 12 KMS Fort St. GeorgemadhaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Site Study Check ListDokument3 SeitenFinal Site Study Check ListmadhaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- ProformaDokument2 SeitenProformamadhaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meeting Room Design Guide: Institute of Technology & Advanced LearningDokument6 SeitenMeeting Room Design Guide: Institute of Technology & Advanced LearningmadhaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles and Practice of Ecological Design: Fan Shu-Yang, Bill Freedman, and Raymond CoteDokument16 SeitenPrinciples and Practice of Ecological Design: Fan Shu-Yang, Bill Freedman, and Raymond CotemadhaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Habitat Centre SynopsisDokument4 SeitenHabitat Centre Synopsismadhavi100% (1)

- Bolt Tightening-Torques PDFDokument4 SeitenBolt Tightening-Torques PDFSH1961100% (2)

- The Views Protection Pile Alternate Design Calcs-1Dokument28 SeitenThe Views Protection Pile Alternate Design Calcs-1aliengineer953Noch keine Bewertungen

- HLX 5 Oms125 Yeni̇modelDokument17 SeitenHLX 5 Oms125 Yeni̇modelroland100% (1)

- Monitoring Shop Drawing MVACDokument2 SeitenMonitoring Shop Drawing MVACEko Indra SaputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- INSR1000Dokument15 SeitenINSR1000nasirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vikramjeet Kumar: Mobile: +91-8054915410 +91-7011773299Dokument4 SeitenVikramjeet Kumar: Mobile: +91-8054915410 +91-7011773299Shankker KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epo RipDokument4 SeitenEpo RipFloorkitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hydraulic Construction EquipmentDokument24 SeitenHydraulic Construction EquipmentAYUSH PARAJULINoch keine Bewertungen

- Vidyasagar Setu Kolkata: Under The Guidance of Prof. Dibya Jivan PatiDokument7 SeitenVidyasagar Setu Kolkata: Under The Guidance of Prof. Dibya Jivan PatisonakshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taliesin West: Assignment 3: Case StudyDokument17 SeitenTaliesin West: Assignment 3: Case StudyGeroke SzekeresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tarif Sewa Alat (PU) +Dokument4 SeitenTarif Sewa Alat (PU) +Abd Rahman WahabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dakin Cennik VRV 2017 2018Dokument25 SeitenDakin Cennik VRV 2017 2018Bikash Chandra DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Analysis On The National Building Code of The Philippines and LeedDokument6 SeitenComparative Analysis On The National Building Code of The Philippines and Leedtrave rafolsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hoa Report Muslim ArchitectureDokument38 SeitenHoa Report Muslim Architecturethe dankiest mmemmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual For Design Using Etabs PDFDokument46 SeitenManual For Design Using Etabs PDFPankaj Sardana100% (1)

- Hexoloy Enhanced Sa Sic en 1008 Tds 215399Dokument1 SeiteHexoloy Enhanced Sa Sic en 1008 Tds 215399Pedro Tavares MurakameNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Stressed ConcreteDokument23 SeitenPre-Stressed ConcreteShabbar Abbas MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Finite Element Based Dynamic Analysis of Multilayer Fibre Composite Sandwich Plates With Interlayer DelaminationsDokument14 SeitenFinite Element Based Dynamic Analysis of Multilayer Fibre Composite Sandwich Plates With Interlayer DelaminationsAhmet EcevitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slip Formwork: Guided by Prof. VRK Murthy Submitted by Vikas B. More (73036) Aniruddha S. Namojwar (73038)Dokument27 SeitenSlip Formwork: Guided by Prof. VRK Murthy Submitted by Vikas B. More (73036) Aniruddha S. Namojwar (73038)simple_ani100% (1)

- FSA 0180 CoDokument58 SeitenFSA 0180 CoNagamani ManiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project ManagementDokument9 SeitenProject Managementanuj jainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guideline For Quality Management of Concrete BDokument62 SeitenGuideline For Quality Management of Concrete BRam KrishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steel CentreDokument15 SeitenSteel CentrewendellNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAM Retaining Wall ReportDokument8 SeitenRAM Retaining Wall ReportRoxana Karin Llontop CaicedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 00 AWWA StandardsDokument3 Seiten00 AWWA Standardsliviu_dovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSA Quotation For Factory Shead & Civil Work For Plotno 46, Bagru JaipurDokument6 SeitenSSA Quotation For Factory Shead & Civil Work For Plotno 46, Bagru JaipurMohit DagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HILTI - Cutting, Sawing and GrindingDokument14 SeitenHILTI - Cutting, Sawing and GrindingSreekumar NairNoch keine Bewertungen