Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

ILONGOTS

Hochgeladen von

Key Harken Salcedo Cruspero0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

43 Ansichten8 Seitenasdasd

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenasdasd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

43 Ansichten8 SeitenILONGOTS

Hochgeladen von

Key Harken Salcedo Crusperoasdasd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 8

Orientation

The Ilongot or Ibilao live in Nueva Vizcaya Province of Luzon in the

Philippines. They numbered about 2,500 in 1975. The name "Ilongot" is

Tagalog and Spanish, and is derived from "Quirungut" (of the forest), one

of the people's own names for themselves. The Ilongot language is

Austronesian (denoting a family of languages spoken in an area), and there

are three dialects: Egongut, Italon, and Abaka. They use Ilocano and

Tagalog in trading. The Ilongot are culturally conservative and

unsubjugated (not comparable). They live as an enclave and resist

incursions into their territory.

Settlements

Ilongot live in thirteen named dialect groups each with an average

population of 180. Each of these groups includes several settlements,

which in turn are made up of four to nine households (five to fifteen nuclear

families, forty to seventy people). When people move to a new area, their

houses are built in clusters, but as farther, more widely spaced new fields

are cleared, houses are built near the new fields, and the settlement

pattern becomes dispersed. Where there is missionary influence, houses

are built clustered near runways. Houses sit on pilings up to 15 feet above

the ground, and have walls of grass or bamboo. There are no inside walls;

each nuclear family (there are one to three per house) has its own

fireplace. There are also temporary field houses. The Ilongots live in the

southern Sierra Madre and Caraballo Mountains in the provinces of Nueva

Vizcaya and Nueva Ecija.

Economy

The Ilongot depend primarily on dry-rice swidden agriculture and

hunting, as well as fishing and gathering. They burn and plant new fields

each year, growing maize and manioc among the rice. Fields that already

have produced one rice crop are planted in tobacco and vegetables, and

fields that are in their last productive service are used to grow sweet

potatoes, bananas, or sugarcane. Fields made from virgin forest are in use

for up to five years, and then lie fallow for eight to ten years. Fields are

abandoned after a second use, and the group farming them leaves to find

new virgin forest. Men in groups hunt several times a week with the aid of

dogs; the meat acquired is shared equally among all households and is

consumed immediately. Sometimes hunts of three to five days take place,

and the meat from these trips is dried for trade or for bride-price

discussions. Individuals who hunt keep their meat for trade. Fish are taken

by nets, traps, spear, or poison. The Ilongot gather fruits, ferns, palm

hearts, and rattan from the forest. They keep domesticated dogs for

hunting, and pigs and chickens for trade. Men forge their own knives, hoes,

and picks, and make rattan baskets, whereas women weave and sew. The

items noted above as destined for trade are exchanged for bullets, cloth,

knives, liquor, and salt. Most trade within Ilongot society occurs during

bride-price payments and gift giving. Real property belongs to whoever

clears it; personal property belongs to the individual as well.

Kinship

Above the level of the nuclear family, the be:rtan, or ambilaterally

reckoned allegiance, is important. Generally, males prefer to become

members of their father's be:rtan, and females members of their mother's,

although in cases in which a man's parents pay his bride-price, all of his

children become members of his be:rtan. This term is used polysemicly to

refer in the first sense to kin to whom one is linked during discussions of

various social situations, as well as the thirteen mutually exclusive local

dialect groups. The names of be:rtan are geographical names, plant

names, place names, or colour terms. Kin terminology is of the Hawaiian

type. Affinal terminology applies only to Ego's generation.

Marriage and Family

Young men are expected to engage in a successful headhunt before

marriage. Young men and women select each other as marriage partners

and form couples prior to marriage. Such a relationship includes casual

field labour, gift giving, and sex. Later, there are formal discussions and

marital exchanges. These discussions are used to settle disputes with the

family of the potential spouse. Premarital pregnancy causes the marriage

process to speed up under threats of violence, and disputes are usually

ended with marriage. Marriage with closely related cousins (especially

second cousins) is preferred, because community leadership is held by

sets of male siblings. Levirate and sororate(a type of marriage in which a

husband engages in marriage or sexual relations with the sister of his wife,

usually after the death of his wife or if his wife has proven infertile) are

common upon the death of a spouse. Marriage is monogamous and

matrilocal(of or denoting a custom in marriage whereby the husband goes

to live with the wife's community) for some years after the wedding; married

couples may return to the husband's natal village only when bride-price

payments are complete.

Socio-political Organization

There is no formal leadership. Informal leadership resides in sets of

brothers, especially those with oratorical (puruN ) skills and knowledge of

genealogy; women claim to be unable to understand puruN. The leader

cannot apply sanctions, but can orchestrate consensus. In cases of dispute

requiring an immediate resolution, the offended party may require that the

alleged offender undergo an ordeal to establish innocence. Warfare is

practiced in the form of headhunting. The reasons for headhunting are an

unsettled feud, a death in one's household, and the obligatory requirement

of a young man to kill before marrying. A pig is sacrificed when the head

hunters return. Warring groups may establish peace through negotiations

and exchanges.

Religion and Expressive Culture

Until the 1950s, when Protestant proselytizers arrived, the Ilongot had had

no contact with major world religions. The traditional belief system includes

supernatural beings who are both helpful and dangerous. Illness is

conceived to be caused by supernaturals who lick or urinate on the

individual, by deceased ancestors, or by supernatural guardians of fields

and forests who become angered by human destruction of what they

guard. There are a few shamans who treat disease, and anyone so cured

can use a portion of the shaman's spiritual power to cure; otherwise,

spiritual curing power comes from illnesses and visions. The individual's

spirit, which travels at night during his life, continues on after death. Since

this spirit is dangerous to the living, it is forced away from habitations by

sweeping, smoking, bathing, and invocation.

Project in Literature I

“Ilongots”

Submitted to:

Romy U. Lumanog, MAEd

Instructor

Submitted by:

Key Harken S. Cruspero

BSIT-2

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Chapter 2-Realated Literature and StudiesDokument21 SeitenChapter 2-Realated Literature and StudiesKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper 9 EnrollDokument1 SeitePaper 9 EnrollKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sourcecode Systemdc: Object Property Settings RemarksDokument1 SeiteSourcecode Systemdc: Object Property Settings RemarksKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- HistoryDokument24 SeitenHistoryKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ILONGOTSDokument8 SeitenILONGOTSKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- How The Angels Built Lake LanaoDokument2 SeitenHow The Angels Built Lake LanaoKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Region 1Dokument19 SeitenRegion 1Kaycee NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Object Oriented ProgrammingDokument1 SeiteObject Oriented ProgrammingKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Object Oriented ProgrammingDokument1 SeiteObject Oriented ProgrammingKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Object Oriented ProgrammingDokument1 SeiteObject Oriented ProgrammingKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Object Oriented ProgrammingDokument1 SeiteObject Oriented ProgrammingKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Region 1Dokument19 SeitenRegion 1Kaycee NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Region 1Dokument19 SeitenRegion 1Kaycee NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Deped-Form-137-E G4-2018Dokument37 SeitenDeped-Form-137-E G4-2018Mark Quidit CovitaNoch keine Bewertungen

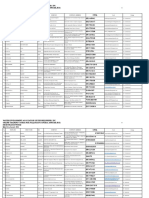

- Professional Teachers 09-2019 Baguio (Secondary)Dokument446 SeitenProfessional Teachers 09-2019 Baguio (Secondary)PRC Baguio100% (24)

- Position PaperDokument6 SeitenPosition PaperSamsung J7 CoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts 7Dokument42 SeitenArts 7Adiene Julienne Lupanggo100% (1)

- CMR Groupings-PCO May 31-June 4, 2021Dokument4 SeitenCMR Groupings-PCO May 31-June 4, 2021Kim Howard CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- RA TEACHERS TUGUE Sep2018-ELEM PDFDokument107 SeitenRA TEACHERS TUGUE Sep2018-ELEM PDFPhilBoardResults100% (1)

- Designation BrigadaDokument37 SeitenDesignation Brigadajulesgajes100% (1)

- DILG R2 2018 Annual Report PDFDokument53 SeitenDILG R2 2018 Annual Report PDFAshley Espiritu CornelioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Cases PDFDokument792 SeitenFull Cases PDFMainam GangstaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TM I B Philippine Tourism Geography CultureDokument23 SeitenTM I B Philippine Tourism Geography Culturejustin leeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cagayan ValleyDokument102 SeitenThe Cagayan ValleyRondel ForjesNoch keine Bewertungen

- RA-030745 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (Mathematics) - Tuguegarao - 9-2019 PDFDokument31 SeitenRA-030745 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (Mathematics) - Tuguegarao - 9-2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Government: List of Licensed Government and Private HospitalsDokument144 SeitenGovernment: List of Licensed Government and Private HospitalsMark GoducoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLUP Status As of 2nd Quarter 2019Dokument57 SeitenCLUP Status As of 2nd Quarter 2019julius ken badeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- NARRATIVE REPORT Math OlympiadDokument7 SeitenNARRATIVE REPORT Math OlympiadFrances MaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (Technology Livelihood, Tech-Voc Education) 03-2024Dokument27 SeitenPROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (Technology Livelihood, Tech-Voc Education) 03-2024PRC BaguioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Activity Sheets Arts Grade 7Dokument4 SeitenLearning Activity Sheets Arts Grade 7Ghia Cressida HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daisy ImmersionDokument24 SeitenDaisy ImmersionDaisy AbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interim NBS Strategy - DOH CVCHD 02Dokument4 SeitenInterim NBS Strategy - DOH CVCHD 02Kyla Malapit GarvidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAS Grade 8 MusicDokument22 SeitenLAS Grade 8 MusicBadeth Ablao100% (1)

- Tuguegarao Elementary PDFDokument60 SeitenTuguegarao Elementary PDFPhilBoardResultsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Session 3 CasesDokument133 SeitenSession 3 CasesJuvylynPiojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk To EarthquakesDokument6 SeitenRisk To EarthquakesCrizel VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lot Data Computation of Lot 4528-B-4Dokument9 SeitenLot Data Computation of Lot 4528-B-4kival231Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arts7 92320Dokument22 SeitenArts7 92320Ericka Mae PatriarcaNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Drivers Education Center (Dec) As of 31 July 2020: Region Province Name Address Contact NumberDokument16 SeitenList of Drivers Education Center (Dec) As of 31 July 2020: Region Province Name Address Contact NumberMico LrzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Teacher - Secondary (Mathematics)Dokument34 SeitenProfessional Teacher - Secondary (Mathematics)PRC BaguioNoch keine Bewertungen

- RA-012407 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (English) - Tuguegarao - 9-2019 PDFDokument55 SeitenRA-012407 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (English) - Tuguegarao - 9-2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monthly Accomplishment Report Ipcrf Based TemplateDokument7 SeitenMonthly Accomplishment Report Ipcrf Based TemplateJai MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Tourism, Geography, and CultureDokument3 SeitenPhilippine Tourism, Geography, and CultureTristan Troy CuetoNoch keine Bewertungen