Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kjim 2016 078

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous ORleRrOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Kjim 2016 078

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous ORleRrCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

REVIEW

Korean J Intern Med 2016;31:1009-1017

https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078

Mean platelet volume: a potential biomarker of

the risk and prognosis of heart disease

Dong-Hyun Choi1, Seong-Ho Kang2, and Heesang Song 3

Departments of 1Internal Medicine, Platelets are essential for progression of atherosclerotic lesions, plaque desta-

2

Laboratory Medicine, and

3 bilization, and thrombosis. They secrete and express many substances that are

Biochemistry and Molecular

Biology, Chosun University School of crucial mediators of coagulation, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Mean plate-

Medicine, Gwangju, Korea let volume (MPV) is a precise measure of platelet size, and is routinely reported

during complete blood count analysis. Emerging evidence supports the use of

MPV as a biomarker predicting the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial

fibrillation, and as a guide for prescription of anticoagulation and rhythm-con-

Received : February 22, 2016

Accepted : October 4, 2016 trol therapy. In addition, MPV may predict the clinical outcome of percutaneous

coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with coronary artery disease and indicate

Correspondence to whether additional adjunctive therapy is needed to improve clinical outcomes.

Dong-Hyun Choi, M.D.

Department of Internal Medi- This review focuses on the current evidence that MPV may be a biomarker of the

cine, Chosun University School risk and prognosis of common heart diseases, particularly atrial fibrillation and

of Medicine, 309 Pilmun-daero, coronary artery disease treated via PCI.

Dong-gu, Gwangju 61452, Korea

Tel: +82-62-220-3773

Fax: +82-62-222-3858 Keywords: Mean platelet volume; Atrial fibrillation; Ischemic stroke; Coronary

E-mail: dhchoi@chosun.ac.kr artery disease; Percutaneous coronary intervention

INTRODUCTION [3,4]. Increased platelet size is linked to other markers

of activity, including platelet aggregation, enhanced

Platelets are small, anucleate cytoplasmic cells that lack thromboxane synthesis and β-thromboglobulin release,

genomic DNA and have a volume of about 7 to 11 fL. and increased expression of adhesion molecules [5]. Con-

They contain many organelles, a microtubular system, sequently, platelet volume is thought to be predictive of

a metabolically active membrane, and have two types of cardiovascular disease [6]. Therefore, the mean platelet

granules. The α granules contain the von Willebrand volume (MPV) has been explored as a possible indicator

factor, platelet-derived growth factor, platelet factor of platelet reactivity and a predictor of various diseases

4, and β-thrombomodulin; the dense platelet bodies [7], particularly cardiovascular disease (Table 1). MPV is a

contain adenosine nucleotides (adenosine diphosphate precise measure of platelet size, being measured via elec-

[ADP] and adenosine triphosphate), calcium, and sero- trical impedance using automated hematological ana-

tonin. Platelets play essential roles in the progression lyzers. MPV is a routine component of a complete blood

of atherosclerotic lesions, plaque destabilization, and count. This review explores the evidence that MPV is a

thrombosis; they express and secrete many substances biomarker of the risk and prognosis of common heart

that are crucial mediators of coagulation, inflammation, diseases, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF) and diseases

and atherosclerosis [1,2]. Larger platelets are enzymat- treated via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

ically and metabolically more dynamic than smaller

ones, and they exhibit greater prothrombotic potential

Copyright © 2016 The Korean Association of Internal Medicine pISSN 1226-3303

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ eISSN 2005-6648

by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

http://www.kjim.org

The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine Vol. 31, No. 6, November 2016

EVIDENCE THAT THE MPV IS A BIOMARKER MPV as a potential guide toward rhythm or rate

OF ISCHEMIC STROKE RISK IN AF PATIENTS control strategies in AF patients

Treatment of AF with rhythm or rate control therapy is

MPV and prediction of stroke risk tailored to patient inclinations and characteristics [18].

AF is the most common major cardiac arrhythmia, and Many randomized controlled clinical trials have com-

it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality pared rhythm and rate control strategies in patients

from ischemic stroke [8,9]. There is a positive associa- with AF, and have found no differences in mortality

tion between MPV and the severity of acute ischemic [19-23]. Nevertheless, the appropriate choice of patients

stroke [10], and MPV is useful for predicting the risk who need rate or rhythm control treatment (to prevent

of ischemic stroke in patients with AF [11-15]. A recent ischemic stroke) among those with AF remains a mat-

case-control study showed that stroke patients with AF ter of contention [24,25]. To the best of our knowledge,

have a higher MPV than AF patients without a stroke only one study, which was both retrospective in nature

history [13]. The precise mechanism underlying the and had a small sample size, has explored whether MPV

supposed relationship (cardiac embolism caused by in- could potentially guide the provision of rhythm or rate

creased platelet reactivity) remains to be fully elucidated. control therapy to AF patients [14]. In this work, the rate

However, Providencia et al. [16] recently suggested an as- control strategy used to treat AF, and a high MPV, were

sociation between MPV and markers of left atrial stasis, independent predictors of ischemic stroke, as was a high

reinforcing the notion that a cardioembolic mechanism CHADS2 score (≥ 2). Such an association was also evident

may be in play when AF is associated with stroke. In that in patients at high risk for ischemic stroke as indicated

study, MPV independently predicted the development by their MPVs and CHADS2 scores. This suggests that

of a left-atrial appendage thrombus. The MPV cutoff implementation of a rhythm control strategy might be

values for predicting ischemic stroke in AF patients necessary in patients with a high MPV or CHADS2 score

were 7.85 to 8.85 fL (Table 1). (≥ 2).

Use of the MPV to guide anticoagulant therapy in AF

patients EVIDENCE THAT MPV IS A BIOMARKER OF

Anticoagulant therapy reduces the risk of stroke by 40% THE RISK AND PROGNOSIS OF CORONARY

in patients with AF, and is more effective than antiplate- ARTERY DISEASES

let therapy [17]. Hence, identifying patients at higher

risk for ischemic stroke is essential to optimize treat- Clinical assessment of MPV is ongoing. Currently, three

ment. The MPV has been shown to enhance the pre- lines of evidence suggest that it is potentially a clinically

dictive value of the clinical variables employed when useful biomarker for risk stratification of patients who

calculating CHADS2 or CHA2DS2VASc scores [11,12]. may develop coronary artery disease after PCI (Table 1).

One study found that the cutoff MPV better predicted First, several studies have addressed the frequencies of

ischemic stroke in those with a lower CHADS2 score (< impaired reperfusion, left ventricular systolic dysfunc-

2) than in those with a higher score (≥ 2) [11]. In addition, tion, and mortality in patients with acute myocardial

those with a high MPV who were not on anticoagulation infarction (AMI) who have undergone primary PCI or

therapy experienced poorer stroke-free survival than thrombolysis [26-39]. Second, some studies have shown

did others; this was true even for patients with CHADS2 that MPV is a useful predictive marker of short- and

scores < 2. It was suggested that anticoagulation therapy long-term clinical outcomes in unselected PCI cohorts,

was required by patients with high MPVs, even those in regardless of whether the patients had undergone elec-

the low to intermediate risk groups. Similarly, anoth- tive or primary PCI [40-47]. Third, some reports have

er study suggested that measurement of MPV may help suggested that MPV, or changes in it over time, reflect

physicians to decide whether to administer anticoagu- high residual platelet reactivity after conventional dual

lants to patients with CHA2DS2VASc scores of 1, who are antiplatelet therapy in patients who have undergone

thus at intermediate risk of stroke [12]. PCI [47-49].

1010 www.kjim.org https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078

Choi DH, et al. MPV as a biomarker of heart diseases

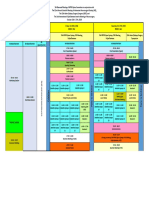

Table 1. Prognostic usefulness of measuring mean platelet volume in cardiovascular diseases

Heart disease Cut off value, f L Reference

Atrial fibrillation

Left atrial stasis 9.4 [16]

Stroke event

Mean follow-up 14 months 8.85 [11]

Mean follow-up 4 years 7.85 [14]

Coronary artery disease

Primary PCI in patients with STEMI

Large thrombus burden 10.2 [37]

No-reflow 9.05–10.3 [26,33,36,38]

In-hospital mortality in diabetic STEMI patients 10.3 [56]

In-hospital mortality in non-diabetic STEMI patients 10.9 [56]

30 Days mortality 9.85 [36]

6 Months mortality 8.90–10.3 [26,30]

12 Months mortality in diabetic STEMI patients 11.0 [56]

12 Months mortality in non-diabetic STEMI patients 11.4 [56]

2 Years MACE 11.7 [31]

Non-selective PCI (elective and primary)

MACCE (mean follow-up 7.6 months) 8.55 [47]

Cardiac death (mean follow-up 2 years) 8.20 [43,44]

MACCE (mean follow-up 2 years) 8.00 [45]

MACE at 1 year follow-up in elective PCI 9.25 [46]

High residual platelet reactivity after antiplatelet therapy

Aspirin 10.25 [48]

Clopidogrel 10.55 [48]

VTE

Unprovoked VTE in general population (mean 10.8 years) 9.5 [60]

1 Month mortality in patients with acute PE 10.9 [61]

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; MACE, major adverse cardiac

event; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; VTE, venous thromboembolism; PE, pulmonary embolism.

MPV and AMI 2-year mortality from STEMI treated via primary PCI

MPV increases during AMI and in the weeks thereaf- [26,30-33,36-38,56]. In addition, a higher MPV on admis-

ter [50-52]. MPV is associated with markers of platelet sion is independently associated with impaired micro-

activity, particularly the expression levels of the glyco- vascular perfusion, a poor postintervention myocardial

protein Ib and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors [53,54]. An blush grade, decreased post-PCI thrombolysis, and a

elevated MPV correlates with poor clinical outcomes poorer myocardial infarction flow grade (thromboly-

among survivors of MI in the era of thrombolysis, and sis in myocardial infarction [TIMI]) in STEMI patients

an impaired response to thrombolysis in those with ST treated via primary PCI [33-36,57]. In one study, a higher

segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [28,55]. MPV on admission was strongly associated with great-

MPV is also a strong independent predictor of impaired er microvascular resistance, a steeper diastolic decel-

angiographic reperfusion, in-hospital major adverse car- eration time, a lower thermodilution-derived coronary

diovascular events, and 30-day, 6-month, 12-month, and flow reserve, and a higher coronary wedge pressure [57].

https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078 www.kjim.org 1011

The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine Vol. 31, No. 6, November 2016

MPV seems to play a role in mediating reperfusion in- in clinical outcomes when platelet function was moni-

jury. In patients with STEMI scheduled for PCI, MPV tored and adjusted in patients who underwent coronary

at admission may be a valuable discriminator of a high- stenting, compared to those who received standard an-

er-risk patient subgroup, and a useful guide when de- tiplatelet therapy (without monitoring); this was a large,

ciding whether adjunctive therapy may be necessary to randomized open-label study on 2,440 patients. Platelet

improve outcomes [27]. MPV cutoff values for predicting activity testing can be time-consuming, expensive, and

poor clinical outcomes in STEMI patients treated via technically complex [70]. However, MPV can be readi-

PCI are 8.9 to 11.7 fL; thus, somewhat higher than those ly measured before PCI using automated hematology

predictive of ischemic stroke in AF patients (Table 1). analyzers. Recently, Kim et al. [48] suggested that a high

MPV was associated with reduced responses to aspirin

MPV and clinical outcomes after PCI and clopidogrel. Some investigators have suggested that

Duygu et al. [40] suggested a role for MPV as a useful an increase in MPV over time after PCI is associated

hematological marker allowing early and simple iden- with high on-treatment platelet reactivity [49]. Moreo-

tification of patients with stable coronary artery disease ver, Choi et al. [47] suggested that MPV was superior to

at high risk for post-PCI low-reflow. MPV independent- platelet function testing in terms of predicting cardi-

ly predicted the post-PCI-corrected TIMI frame count. ac death or cardiovascular events in patients who had

Another study found that MPV predicted in-stent reste- undergone PCI, particularly those in an acute coronary

nosis in patients undergoing PCI [58]. Similar to the ef- syndrome subgroup.

fects of MPV on AMI, several studies have found that an

elevated MPV is a strong independent predictor of long-

term outcomes after PCI [41-47]. However, one study COMPARISON OF THE PREDICTIVE UTILITY

found that mortality increased when the MPV rose over OF MPV AND OTHER TRADITIONAL BIOMARK-

time after PCI, but the pre-procedural MPV was not pre- ERS IN TERMS OF CLINICAL OUTCOMES

dictive in this context [59]. It was suggested that mon-

itoring of MPV after PCI might aid risk stratification. Traditional biomarkers, including pulse wave velocity

MPV cutoffs for predicting poor clinical outcomes in and the levels of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T,

patients with unselected coronary artery disease treated N-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide, and C-reac-

via PCI are 8.00 to 9.25 fL (Table 1) [11,14,16,26,30,31,33,36- tive protein, have long been of clinical research interest

38,43-48,56,60,61]. because of the roles that they play in predicting the clin-

ical outcomes of patients with heart disease. Recently,

MPV and residual platelet reactivity in patients on some studies have suggested that a high MPV has a pre-

dual antiplatelet therapy dictive utility comparable to those of other biomarkers

Antiplatelet therapy reduces the incidence of both (Table 2, Fig. 1) [43-45].

procedure-related complications and ischemic cardio-

vascular events after PCI [62,63]. Particularly, dual anti-

platelet therapy (aspirin and an ADP receptor inhibitor) LIMITATIONS OF MPV

is the present standard of care after implantation of

drug-eluting stents. Nevertheless, high residual plate- MPV can be simply and inexpensively determined and

let reactivity can limit the utility of antiplatelet therapy, does not require professional interpretation. However,

increasing the frequency of cardiovascular events both there are several limitations to using MPV as an indica-

during the procedure and during long-term follow-up tor of heart disease. This is because most relevant stud-

[64-67]. Recently, however, Paulu et al. [68], in a prospec- ies have been retrospective in nature, enrolled small

tive observational study, showed that clopidogrel re- numbers of patients, or had confounding factors that

sistance was not of prognostic utility in an unselected may have affected platelet volume [71]. Furthermore,

cohort of 378 patients who underwent PCI. In addition, a wide range of cut-off values has been used in retro-

Collet et al. [69] observed no significant improvement spective studies, emphasizing that prospective works

1012 www.kjim.org https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078

Choi DH, et al. MPV as a biomarker of heart diseases

Table 2. MPV, hs-cTnT, NT-proBNP level, and baPWV to predict cardiac death after percutaneous coronary intervention

Variable Area 95% CI p value Comparison with MPV

MPV 0.791 0.688–0.895 < 0.001 -

hs-cTnT 0.691 0.583–0.799 0.003 0.1632

NT-proBNP 0.828 0.734–0.922 < 0.001 0.5228

baPWV 0.778 0.700–0.861 < 0.001 0.8495

MPV, mean platelet volume; hs-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T level; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B type natriuret-

ic peptide; baPWV, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity; CI, confidence interval.

100

CONCLUSIONS

80 Many studies have shown associations between an ele-

vated MPV, the risk of ischemic stroke in AF patients,

and poor clinical outcomes after PCI in patients with

Sensitivity

60

coronary artery disease. This marker can help physicians

to identify patients at high risk for ischemic stroke, who

40

thus require anticoagulation therapy, and AF patients

who need rhythm control therapy. The marker also af-

MPV fords valuable insights into how to identify patients at

20 hs-cTnT high risk for coronary artery disease after PCI, and pro-

NT-proBNP

vides useful guidance as to when additional adjunctive

baPWV

therapy is needed to improve clinical outcomes. Much

0

remains to be learned about MPV. It is essential to ex-

20 40 60 80 100 plore whether therapeutic adjustment of the marker im-

100-Specificity proves cardiovascular care.

Figure 1. Receiver operating characteristic curve for mean

platelet volume (MPV), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T Conflict of interest

level (hs-cTnT), N-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article

(NT-proBNP) level, and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

(baPWV) to predict cardiac death after percutaneous coro-

was reported.

nary intervention. Adapted from Ki et al. [43], with permis-

sion from Taylor & Francis and Seo et al. [44], with permis- Acknowledgments

sion from Taylor & Francis.

This research was supported by Basic Science Research

Program through the National Research Foundation of

Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and

are needed. MPV increases as blood is stored in eth- future Planning (2016R1A2B4011905) and the Ministry of

ylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and the reliability of MPV Education, Science and Technology (2014028083).

measurement gradually decreases after 4 hours of such

storage [72,73]. Therefore, MPV should be measured

within 4 hours of sampling to exclude the possibility of REFERENCES

storage-related errors. Notwithstanding the potential

clinical utility of MPV, these issues, together with meth- 1. Coppinger JA, Cagney G, Toomey S, et al. Characterization

odological problems in MPV assessment, continue to be of the proteins released from activated platelets leads to

important limitations. localization of novel platelet proteins in human athero-

sclerotic lesions. Blood 2004;103:2096-2104.

2. Gawaz M, Langer H, May AE. Platelets in inflammation

https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078 www.kjim.org 1013

The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine Vol. 31, No. 6, November 2016

and atherogenesis. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3378-3384. tion and the presence of thrombotic events. Biomed Rep

3. Karpatkin S. Heterogeneity of human platelets. II. Func- 2015;3:388-394.

tional evidence suggestive of young and old platelets. J 16. Providencia R, Faustino A, Paiva L, et al. Mean platelet

Clin Invest 1969;48:1083-1087. volume is associated with the presence of left atrial stasis

4. Kamath S, Blann AD, Lip GY. Platelet activation: assess- in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. BMC Car-

ment and quantification. Eur Heart J 2001;22:1561-1571. diovasc Disord 2013;13:40.

5. Bath PM, Butterworth RJ. Platelet size: measurement, 17. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrom-

physiology and vascular disease. Blood Coagul Fibrinoly- botic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have non-

sis 1996;7:157-161. valvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857-

6. Tsiara S, Elisaf M, Jagroop IA, Mikhailidis DP. Platelets 867.

as predictors of vascular risk: is there a practical index of 18. Gillis AM, Verma A, Talajic M, Nattel S, Dorian P; CCS

platelet activity? Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2003;9:177- Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Committee. Canadian Car-

190. diovascular Society atrial fibrillation guidelines 2010: rate

7. Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mikhailidis DP, Kitas GD. and rhythm management. Can J Cardiol 2011;27:47-59.

Mean platelet volume: a link between thrombosis and 19. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of

inflammation? Curr Pharm Des 2011;17:47-58. rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial

8. Chugh SS, Roth GA, Gillum RF, Mensah GA. Global bur- fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1825-1833.

den of atrial fibrillation in developed and developing 20. Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, et al. A compari-

nations. Glob Heart 2014;9:113-119. son of rate control and rhythm control in patients with

9. Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diag- recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med

nosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications 2002;347:1834-1840.

for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the 21. Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Lilienthal J. Rhythm or rate

AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation control in atrial fibrillation. Pharmacological Interven-

(ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001;285:2370-2375. tion in Atrial Fibrillation (PIAF): a randomised trial. Lan-

10. Greisenegger S, Endler G, Hsieh K, Tentschert S, Mann- cet 2000;356:1789-1794.

halter C, Lalouschek W. Is elevated mean platelet volume 22. Carlsson J, Miketic S, Windeler J, et al. Randomized trial

associated with a worse outcome in patients with acute of rate-control versus rhythm-control in persistent atrial

ischemic cerebrovascular events? Stroke 2004;35:1688- fibrillation: the Strategies of Treatment of Atrial Fibrilla-

1691. tion (STAF) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1690-1696.

11. Ha SI, Choi DH, Ki YJ, et al. Stroke prediction using 23. Opolski G, Torbicki A, Kosior DA, et al. Rate control vs

mean platelet volume in patients with atrial fibrillation. rhythm control in patients with nonvalvular persistent

Platelets 2011;22:408-414. atrial fibrillation: the results of the Polish How to Treat

12. Bayar N, Arslan S, Cagirci G, et al. Usefulness of mean Chronic Atrial Fibrillation (HOT CAFE) Study. Chest

platelet volume for predicting stroke risk in paroxysmal 2004;126:476-486.

atrial fibrillation patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 24. Tsadok MA, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, et al. Rhythm ver-

2015;26:669-672. sus rate control therapy and subsequent stroke or tran-

13. Turfan M, Erdogan E, Ertas G, et al. Usefulness of mean sient ischemic attack in patients with atrial fibrillation.

platelet volume for predicting stroke risk in atrial fibril- Circulation 2012;126:2680-2687.

lation patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2013;24:55-58. 25. Sherman DG, Kim SG, Boop BS, et al. Occurrence and

14. Hong SP, Choi DH, Kim HW, et al. Stroke prevention in characteristics of stroke events in the Atrial Fibrillation

patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: new insight Follow-up Investigation of Sinus Rhythm Management

in selection of rhythm or rate control therapy and impact (AFFIRM) study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1185-1191.

of mean platelet volume. Curr Pharm Des 2013;19:5824- 26. Huczek Z, Kochman J, Filipiak KJ, et al. Mean platelet

5829. volume on admission predicts impaired reperfusion and

15. Xu XF, Jiang FL, Ou MJ, Zhang ZH. The association be- long-term mortality in acute myocardial infarction treat-

tween mean platelet volume and chronic atrial fibrilla- ed with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J

1014 www.kjim.org https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078

Choi DH, et al. MPV as a biomarker of heart diseases

Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:284-290. 37. Lai HM, Xu R, Yang YN, et al. Association of mean platelet

27. Maden O, Kacmaz F, Selcuk H, et al. Relationship of volume with angiographic thrombus burden and short-

admission hematological indexes with myocardial term mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation

reperfusion abnormalities in acute ST segment eleva- myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous

tion myocardial infarction patients treated with primary coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2015;85

percutaneous coronary interventions. Can J Cardiol Suppl 1:724-733.

2009;25:e164-e168. 38. Cakici M, Cetin M, Balli M, et al. Predictors of thrombus

28. Pereg D, Berlin T, Mosseri M. Mean platelet volume on burden and no-reflow of infarct-related artery in patients

admission correlates with impaired response to throm- with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: im-

bolysis in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarc- portance of platelet indices. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis

tion. Platelets 2010;21:117-121. 2014;25:709-715.

29. Acar Z, Aga MT, Kiris A, et al. Mean platelet volume on 39. Wang XY, Yu HY, Zhang YY, et al. Serial changes of mean

admission is associated with further left ventricular func- platelet volume in relation to Killip Class in patients with

tions in primary PTCA patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol acute myocardial infarction and primary percutaneous

Sci 2012;16:1567-1569. coronary intervention. Thromb Res 2015;135:652-658.

30. Akgul O, Uyarel H, Pusuroglu H, et al. Prognostic value 40. Duygu H, Turkoglu C, Kirilmaz B, Turk U. Effect of mean

of elevated mean platelet volume in patients undergoing platelet volume on postintervention coronary blood flow

primary angioplasty for ST-elevation myocardial infarc- in patients with chronic stable angina pectoris. J Invasive

tion. Acta Cardiol 2013;68:307-314. Cardiol 2008;20:120-124.

31. Rechcinski T, Jasinska A, Forys J, et al. Prognostic value of 41. Goncalves SC, Labinaz M, Le May M, et al. Usefulness of

platelet indices after acute myocardial infarction treated mean platelet volume as a biomarker for long-term out-

with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardi- comes after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J

ol J 2013;20:491-498. Cardiol 2011;107:204-209.

32. Celik T, Kaya MG, Akpek M, et al. Predictive value of ad- 42. Eisen A, Bental T, Assali A, Kornowski R, Lev EI. Mean

mission platelet volume indices for in-hospital major ad- platelet volume as a predictor for long-term outcome

verse cardiovascular events in acute ST-segment elevation after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Thromb

myocardial infarction. Angiology 2015;66:155-162. Thrombolysis 2013;36:469-474.

33. Elbasan Z, Gur M, Sahin DY, et al. Association of mean 43. Ki YJ, Park S, Ha SI, Choi DH, Song H. Usefulness of

platelet volume and pre- and postinterventional flow with mean platelet volume as a biomarker for long-term clini-

infarct-related artery in ST-segment elevation myocardial cal outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in

infarction. Angiology 2013;64:440-446. Korean cohort: a comparable and additive predictive val-

34. Sarli B, Baktir AO, Saglam H, et al. Mean platelet volume ue to high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and N-terminal

is associated with poor postinterventional myocardial pro-B type natriuretic peptide. Platelets 2014;25:427-432.

blush grade in patients with ST-segment elevation myo- 44. Seo HJ, Ki YJ, Han MA, Choi DH, Ryu SW. Brachial-ankle

cardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis 2013;24:285-289. pulse wave velocity and mean platelet volume as predic-

35. Karahan Z, Ucaman B, Ulug AV, et al. Effect of hematolog- tive values after percutaneous coronary intervention for

ic parameters on microvascular reperfusion in patients long-term clinical outcomes in Korea: a comparable and

with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated additive study. Platelets 2015;26:665-671.

with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Angi- 45. Moon AR, Choi DH, Jahng SY, et al. High-sensitivity C-re-

ology 2016;67:151-156. active protein and mean platelet volume as predictive

36. Lai HM, Chen QJ, Yang YN, et al. Association of mean values after percutaneous coronary intervention for long-

platelet volume with impaired myocardial reperfusion term clinical outcomes: a comparable and additive study.

and short-term mortality in patients with ST-segment Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2016;27:70-76.

elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary per- 46. Seyyed-Mohammadzad MH, Eskandari R, Rezaei Y, et

cutaneous coronary intervention. Blood Coagul Fibrino- al. Prognostic value of mean platelet volume in patients

lysis 2016;27:5-12. undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention.

https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078 www.kjim.org 1015

The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine Vol. 31, No. 6, November 2016

Anatol J Cardiol 2015;15:25-30. ume as a predictor of cardiovascular risk: a systematic

47. Choi SW, Choi DH, Kim HW, Ku YH, Ha SI, Park G. Clin- review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:148-

ical outcome prediction from mean platelet volume in 156.

patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention 59. Shah B, Oberweis B, Tummala L, et al. Mean platelet

in Korean cohort: implications of more simple and useful volume and long-term mortality in patients undergo-

test than platelet function testing. Platelets 2014;25:322- ing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol

327. 2013;111:185-189.

48. Kim YG, Suh JW, Yoon CH, et al. Platelet volume indices 60. Braekkan SK, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T,

are associated with high residual platelet reactivity after Stormer J, Hansen JB. Mean platelet volume is a risk

antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous factor for venous thromboembolism: the Tromso Study,

coronary intervention. J Atheroscler Thromb 2014;21:445- Tromso, Norway. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:157-162.

453. 61. Kostrubiec M, Labyk A, Pedowska-Wloszek J, et al. Mean

49. Koh YY, Kim HH, Choi DH, et al. Relation between the platelet volume predicts early death in acute pulmonary

change in mean platelet volume and clopidogrel resis- embolism. Heart 2010;96:460-465.

tance in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary in- 62. Shanker J, Gasparyan AY, Kitas GD, Kakkar VV. Platelet

tervention. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2015;13:687-693. function and antiplatelet therapy in cardiovascular dis-

50. Cameron HA, Phillips R, Ibbotson RM, Carson PH. Plate- ease: implications of genetic polymorphisms. Curr Vasc

let size in myocardial infarction. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) Pharmacol 2011;9:479-489.

1983;287:449-451. 63. Gasparyan AY, Watson T, Lip GY. The role of aspirin in

51. Kilicli-Camur N, Demirtunc R, Konuralp C, Eskiser A, cardiovascular prevention: implications of aspirin resis-

Basaran Y. Could mean platelet volume be a predictive tance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1829-1843.

marker for acute myocardial infarction? Med Sci Monit 64. Snoep JD, Hovens MM, Eikenboom JC, van der Bom

2005;11:CR387-CR392. JG, Jukema JW, Huisman MV. Clopidogrel nonrespon-

52. Martin JF, Plumb J, Kilbey RS, Kishk YT. Changes in vol- siveness in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary

ume and density of platelets in myocardial infarction. Br intervention with stenting: a systematic review and me-

Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:456-459. ta-analysis. Am Heart J 2007;154:221-231.

53. Tschoepe D, Roesen P, Kaufmann L, et al. Evidence for 65. Patti G, Nusca A, Mangiacapra F, Gatto L, D’Ambrosio A,

abnormal platelet glycoprotein expression in diabetes Di Sciascio G. Point-of-care measurement of clopidogrel

mellitus. Eur J Clin Invest 1990;20:166-170. responsiveness predicts clinical outcome in patients

54. Giles H, Smith RE, Martin JF. Platelet glycoprotein IIb-II- undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention results

Ia and size are increased in acute myocardial infarction. of the ARMYDA-PRO (Antiplatelet therapy for Reduc-

Eur J Clin Invest 1994;24:69-72. tion of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty-Platelet

55. Pabon Osuna P, Nieto Ballesteros F, Morinigo Munoz JL, Reactivity Predicts Outcome) study. J Am Coll Cardiol

et al. The effect of the mean platelet volume on the short- 2008;52:1128-1133.

term prognosis of acute myocardial infarct. Rev Esp Car- 66. Price MJ, Endemann S, Gollapudi RR, et al. Prognostic

diol 1998;51:816-822. significance of post-clopidogrel platelet reactivity as-

56. Lekston A, Hudzik B, Hawranek M, et al. Prognostic sig- sessed by a point-of-care assay on thrombotic events after

nificance of mean platelet volume in diabetic patients drug-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J 2008;29:992-

with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Diabetes Com- 1000.

plications 2014;28:652-657. 67. Bonello L, Pansieri M, Mancini J, et al. High on-treat-

57. Sezer M, Okcular I, Goren T, et al. Association of haema- ment platelet reactivity after prasugrel loading dose and

tological indices with the degree of microvascular injury cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary inter-

in patients with acute anterior wall myocardial infarction vention in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol

treated with primary percutaneous coronary interven- 2011;58:467-473.

tion. Heart 2007;93:313-318. 68. Paulu P, Osmancik P, Tousek P, et al. Lack of association

58. Chu SG, Becker RC, Berger PB, et al. Mean platelet vol- between clopidogrel responsiveness tested using point-

1016 www.kjim.org https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078

Choi DH, et al. MPV as a biomarker of heart diseases

of-care assay and prognosis of patients with coronary 2012;44:805-816.

artery disease. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2013;36:1-6. 72. Brummitt DR, Barker HF. The determination of a refer-

69. Collet JP, Cuisset T, Range G, et al. Bedside monitoring to ence range for new platelet parameters produced by the

adjust antiplatelet therapy for coronary stenting. N Engl J Bayer ADVIA120 full blood count analyser. Clin Lab Hae-

Med 2012;367:2100-2109. matol 2000;22:103-107.

70. Michelson AD. Methods for the measurement of platelet 73. Song YH, Park SH, Kim JE, et al. Evaluation of platelet

function. Am J Cardiol 2009;103(3 Suppl):20A-26A. indices for differential diagnosis of thrombocytosis by

71. Leader A, Pereg D, Lishner M. Are platelet volume indi- ADVIA 120. Korean J Lab Med 2009;29:505-509.

ces of clinical use? A multidisciplinary review. Ann Med

https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.078 www.kjim.org 1017

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Brain Sciences: Thiamine Deficiency Causes Long-Lasting Neurobehavioral Deficits in MiceDokument15 SeitenBrain Sciences: Thiamine Deficiency Causes Long-Lasting Neurobehavioral Deficits in MiceAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epidural Bupivacaine-Fentanyl Provides Superior Postoperative Pain Relief vs. IV PCA Morphine After Gynecological SurgeryDokument6 SeitenEpidural Bupivacaine-Fentanyl Provides Superior Postoperative Pain Relief vs. IV PCA Morphine After Gynecological SurgeryAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is Venous Congestion Associated With Reduced Cerebral Oxygenation and Worse Neurological Outcome After Cardiac Arrest?Dokument8 SeitenIs Venous Congestion Associated With Reduced Cerebral Oxygenation and Worse Neurological Outcome After Cardiac Arrest?Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Postoperative Pain at Rest After Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Severity, Sensory Qualities and Impact On SleepDokument6 SeitenAcute Postoperative Pain at Rest After Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Severity, Sensory Qualities and Impact On SleepAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basics of Mechanical VentilationDokument208 SeitenBasics of Mechanical VentilationAnonymous ORleRr100% (1)

- International Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectDokument4 SeitenInternational Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care: Jamie Sleigh, Martyn Harvey, Logan Voss, Bill DennyDokument6 SeitenTrends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care: Jamie Sleigh, Martyn Harvey, Logan Voss, Bill DennyAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dog As An Animal Model For Intervertebral Disc Degeneration?Dokument9 SeitenThe Dog As An Animal Model For Intervertebral Disc Degeneration?Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- OK Sio 2017Dokument6 SeitenOK Sio 2017Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prokalsitonin Dan Kultur Darah Sebagai Penanda Sepsis Di Rsup DR Wahidin Sudirohusodo MakassarDokument11 SeitenProkalsitonin Dan Kultur Darah Sebagai Penanda Sepsis Di Rsup DR Wahidin Sudirohusodo MakassarAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Felsenstein 2020Dokument13 SeitenFelsenstein 2020Mochamad RizkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annals of EpidemiologyDokument7 SeitenAnnals of EpidemiologyAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gland Corporate BrochureDokument6 SeitenGland Corporate BrochureAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- OA 737-11-18 Comparison Between Effectiveness of Transtracheal Block Alone Versus Superior Laryngeal1Dokument5 SeitenOA 737-11-18 Comparison Between Effectiveness of Transtracheal Block Alone Versus Superior Laryngeal1Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Back Facts 10102Dokument2 SeitenBack Facts 10102Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fluid Challenge Algorithm - 2006Dokument1 SeiteFluid Challenge Algorithm - 2006Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- ID Hubungan Faktor Resiko Dengan Terjadinya Nyeri Punggung Bawah Low Back Pain Pada PDFDokument10 SeitenID Hubungan Faktor Resiko Dengan Terjadinya Nyeri Punggung Bawah Low Back Pain Pada PDFAnonymous aH8gCZ7zjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Anembryonic Pregnancy Loss: An Observational StudyDokument6 SeitenManagement of Anembryonic Pregnancy Loss: An Observational StudyAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNAIR, ASAD, Surabaya Sanglah Hospital, Bali BNDCC, Bali BNDCC, BaliDokument1 SeiteUNAIR, ASAD, Surabaya Sanglah Hospital, Bali BNDCC, Bali BNDCC, BaliAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Algo ArrestDokument2 SeitenAlgo ArrestLocomotorica FK UkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perioperative Management of Thyroid DysfunctionDokument5 SeitenPerioperative Management of Thyroid DysfunctionAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- 605 FullDokument3 Seiten605 FullAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsDokument3 SeitenDiabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cover Dalam Dan Abstrak Siti Aisya Sakinah Web PDFDokument3 SeitenCover Dalam Dan Abstrak Siti Aisya Sakinah Web PDFAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Platelets and Atherosclerosis: John C. Hoak, M.DDokument4 SeitenPlatelets and Atherosclerosis: John C. Hoak, M.DAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- BJH 14482Dokument12 SeitenBJH 14482Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Verify Your Mobile NumberDokument2 SeitenHow To Verify Your Mobile NumberAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nautic Us Privacy PolicyDokument3 SeitenNautic Us Privacy PolicyAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- BJH 14482Dokument12 SeitenBJH 14482Anonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science of The Total Environment: Contents Lists Available atDokument8 SeitenScience of The Total Environment: Contents Lists Available atAnonymous ORleRrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Fasciotomy Procedures On Acute Compartment Syndromes of The Upper Extremity Related To BurnsDokument6 SeitenFasciotomy Procedures On Acute Compartment Syndromes of The Upper Extremity Related To BurnsMetta TantraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antianginal and Antiischemic DrugsDokument18 SeitenAntianginal and Antiischemic DrugsNaveen KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathology in Clinical Practice 50 Case Studies - 2009Dokument224 SeitenPathology in Clinical Practice 50 Case Studies - 2009Omar SarvelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2 Pathophysiology Carewell PharmaDokument23 SeitenUnit 2 Pathophysiology Carewell Pharmaakshay dhootNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compiled Do or Die Physio CAT 1 ShowDokument99 SeitenCompiled Do or Die Physio CAT 1 ShowSaktai DiyamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intra Aortic Balloon PumpDokument3 SeitenIntra Aortic Balloon PumpNkk Aqnd MgdnglNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDokument38 SeitenPeripheral Arterial DiseaseRessy HastoprajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Blood VesselsDokument26 Seiten12 Blood VesselsBalaji DNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nattokinase - Optimum Health Vitamins PDFDokument13 SeitenNattokinase - Optimum Health Vitamins PDFAnonymous SQh10rG100% (1)

- ACEP - October 2023 1Dokument24 SeitenACEP - October 2023 1s2qtxnxwk7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cerebrovascular AccidentDokument42 SeitenCerebrovascular AccidentGideon HaburaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuropathology Autopsy Practice Post Mortem Examination in Cerebrovascular Disease StrokeDokument15 SeitenNeuropathology Autopsy Practice Post Mortem Examination in Cerebrovascular Disease Strokelisboa_rodriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cerebrovascular Accident (Cva) : DescriptionDokument12 SeitenCerebrovascular Accident (Cva) : DescriptionAbeera AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- TA Web 72012Dokument2 SeitenTA Web 72012Erika KusumawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moshe Schein - Controversies in SurgeryDokument409 SeitenMoshe Schein - Controversies in SurgeryBogdan TrandafirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pressure Ulcers - Back To The BasicsDokument11 SeitenPressure Ulcers - Back To The BasicsHari Prasath T RNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case StudyDokument5 SeitenCase StudyMary Mae Boncayao50% (4)

- SURGICAL PROCEDURES AND COMPLICATIONSDokument55 SeitenSURGICAL PROCEDURES AND COMPLICATIONSNikxyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuroimaging of Acute Ischemic Stroke Multimodal Imaging Approach For Acute Endovascular TherapyDokument17 SeitenNeuroimaging of Acute Ischemic Stroke Multimodal Imaging Approach For Acute Endovascular TherapyEliana NataliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiovascular System Documents Covering Anatomy, Pathophysiology, Pharmacology & MoreDokument49 SeitenCardiovascular System Documents Covering Anatomy, Pathophysiology, Pharmacology & MoreDinesh Kumar ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Compartment SyndromeDokument15 SeitenAcute Compartment SyndromeDea Sella SabrinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevent and Reverse Heart DiseaseDokument95 SeitenPrevent and Reverse Heart Diseaseyhanteran100% (4)

- Innovations in Cardiovascular Disease ManagementDokument183 SeitenInnovations in Cardiovascular Disease ManagementGopal Kumar DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perinatal Asphyxia - Outline of Pathophysiology and Recent Trends in ManagementDokument31 SeitenPerinatal Asphyxia - Outline of Pathophysiology and Recent Trends in Managementokwadha simionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stroke and Neuro Anatomy: Angela RootsDokument22 SeitenStroke and Neuro Anatomy: Angela RootsCristian Florin CrasmaruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moyamoya Disease in ChildrenDokument13 SeitenMoyamoya Disease in ChildrenMiguelIbañezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vascular Complication of Injectable FillerDokument17 SeitenVascular Complication of Injectable Fillerahmed100% (1)

- Surgery - MCQ - 3rd - BHMS - (Old, New, 2015)Dokument57 SeitenSurgery - MCQ - 3rd - BHMS - (Old, New, 2015)Anil kadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical TerminologyDokument154 SeitenMedical TerminologySamuel Obeng100% (3)

- Test Bank For Comprehensive Radiographic Pathology 6th Edition by EisenbergDokument36 SeitenTest Bank For Comprehensive Radiographic Pathology 6th Edition by Eisenbergmilreis.cunettew2ncs100% (48)