Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

ost-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction Clinical Characterization and Preliminary Assessment of Contributory Factors and Dose-Response Relationship

Hochgeladen von

Teressa ShawCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ost-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction Clinical Characterization and Preliminary Assessment of Contributory Factors and Dose-Response Relationship

Hochgeladen von

Teressa ShawCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction

Clinical Characterization and Preliminary Assessment of Contributory Factors

and Dose-Response Relationship

Joseph Ben-Sheetrit, MD,* Dov Aizenberg, MD,*† Antonei B. Csoka, PhD,‡

Abraham Weizman, MD,*† and Haggai Hermesh, MD*†

in some patients, it persists beyond cessation of pharmacological

Abstract: Emerging evidence suggests that sexual dysfunction emerging treatment. In a prospective study of patients with SSRI-induced

during treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and/ sexual dysfunction, Montejo et al6 found that switching treatment

or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) persists in some from an SSRI to amineptine, a tricyclic antidepressant that acts

patients beyond drug discontinuation (post-SSRI sexual dysfunction primarily on dopaminergic systems, decreased the frequency of

[PSSD]). We sought to identify and characterize a series of such cases sexual dysfunction to 55% after 6 months while depression re-

and explore possible explanatory factors and exposure-response relation- mained in remission. As amineptine was not associated with sex-

ship. Subjects who responded to an invitation in a forum dedicated to ual dysfunction in patients who have not previously taken an

PSSD filled out a survey via online software. Case probability was defined SSRI, Bahrick7 suggested that this observation could be inter-

according to the following 3 categories of increasing presumed likelihood preted as evidence of enduring post-SSRI sexual dysfunction. In

of PSSD. Noncases did not meet the criteria for possible cases. Possible a prospective randomized placebo-controlled trial of premature

cases were subjects with normal pretreatment sexual function who first ex- ejaculation successfully treated with citalopram, Safarinejad and

perienced sexual disturbances while using a single SSRI/SNRI, which did Hosseini8 showed that time to ejaculation remained significantly

not resolve upon drug discontinuation for 1 month or longer as indicated by delayed in 3- and 6-month follow-up after discontinuation of treat-

Arizona Sexual Experience Scale scores. High-probability cases were also ment compared to the placebo arm. From 2006 to 2008, 8 cases

younger than 50-year-olds; did not have confounding medical conditions, of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction persisting after SSRI

medications, or drug use; and had normal scores on the Hospital Anxiety discontinuation appeared in the literature, in which genital anes-

and Depression Scale. Five hundred thirty-two (532) subjects completed thesia and pleasureless orgasm emerged as potential markers of

the survey, among which 183 possible cases were identified, including what Csoka et al tentatively termed post-SSRI sexual dysfunc-

23 high-probability cases. Female sex, genital anesthesia, and depression tion (PSSD).4,5,9,10 In 2012, the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance

predicted current sexual dysfunction severity, but dose/defined daily dose Center (Lareb) published an official report about PSSD, which in-

ratio and anxiety did not. Genital anesthesia did not correlate with depres- cluded 19 additional possible cases, calling for further investiga-

sion or anxiety, but pleasureless orgasm was an independent predictor of tion of the subject.11,12 Stinson13 has conducted an in-depth

both depression and case probability. Limitations of the study include ret- qualitative psychological investigation of 9 patients with PSSD,

rospective design and selection and report biases that do not allow general- which showed a pervasive negative impact on the quality of life.

ization or estimation of incidence. However, our findings add to previous Using data from an Internet portal for reporting adverse events,

reports and support the existence of PSSD, which may not be fully ex- Hogan et al14 found 91 reports of persistent sexual dysfunction

plained by alternative nonpharmacological factors related to sexual dys- linked to treatment with SSRIs or serotonin-norepinephrine reup-

function, including depression and anxiety. take inhibitors (SNRIs). Waldinger et al15 have recently described

Key Words: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a case study of successful treatment of penile anesthesia by low-

serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), persistent sexual power laser irradiation in a patient with PSSD, hypothesizing that

dysfunction, genital anesthesia, pleasureless orgasm, post-SSRI SSRIs may cause disturbances in transient receptor potential ion

sexual dysfunction (PSSD) channels of mechano-, thermo-, and chemosensitive nerve end-

ings and receptors, thus leading to the persistent genital anesthesia

(J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35: 273–278)

reported in PSSD. Csoka and Szyf16 suggested that epigenetic

alterations in the DNA may play a role in the pathogenesis of the

S exual dysfunction is a well-documented adverse effect of anti-

depressants, particularly frequent with selective serotonin re-

uptake inhibitors (SSRIs).1 It is now widely acknowledged that

syndrome. To further identify and characterize cases of treatment-

emergent sexual dysfunction persisting after SSRI/SNRI discon-

tinuation, as well as to evaluate possible explanatory factors and

SSRIs can cause disturbances in every aspect of sexual function, dose-response relationship, we conducted an Internet survey

including libido, arousal, erection, lubrication, orgasm,2 and also about sexual adverse effects of antidepressants using a structured

genital sensation.3–5 Sexual dysfunction is assumed to resolve self-report questionnaire and well-defined case-definition criteria.

upon drug discontinuation, but emerging evidence indicates that

METHODS

From the *Geha Mental Health Center, Petah Tikva; †Sackler Faculty of An invitation to participate in the survey was posted in an

Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel; and ‡Department of Anatomy,

School of Medicine, Howard University, Washington D.C.

Internet forum dedicated to PSSD ("SSRIsex – Persistent SSRI

Received October 13, 2014; accepted after revision February 11, 2015. Sexual Side Effects," URL: http://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/

Reprints: Joseph Ben-Sheetrit, MD, Geha Mental Health Center, SSRIsex/info). Participants filled out the survey via online survey

1 Helsinki St, PO Box 102, Petah Tikva 4910002, Israel software (Qualtrics.com). The study was approved by the Geha

(e‐mail: joseph.ben.sheetrit@gmail.com).

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Mental Health Center Review Board. The survey opened with a full

ISSN: 0271-0749 informed consent form that consisted of questions regarding demo-

DOI: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000300 graphic details (sex, age, relationship status, country of residence),

Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology • Volume 35, Number 3, June 2015 www.psychopharmacology.com 273

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Ben-Sheetrit et al Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology • Volume 35, Number 3, June 2015

experiences of sexual dysfunction while taking any medication sexual dysfunction was required as an inclusion criterion, since

(yes/no question, additional open-text question for description), a comparison of pretreatment versus current sexual dysfunction

details of all the medications used while experiencing sexual dys- is beyond the scope of the survey. Drug discontinuation is a defin-

function (names, doses, durations of use, and time since quitting ing feature of PSSD. A cutoff point of 1 month was chosen for

each medication; open-text questions), sexual dysfunction before 2 reasons. First, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

taking the medications (yes/no question, with space for details), Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criterion C for medication-

current sexual function as assessed by the Arizona Sexual Experi- induced sexual dysfunction seems to indicate that 1 month is a

ence Scale (ASEX),17 questions regarding genital anesthesia and substantial period of time during which sexual adverse effects of

erectile response to visual stimuli (multiple-choice Likert-scale medications are expected to wear off. Second, virtually all of the

items), current medical conditions (open-text question), current drug is eliminated from the patient's body after 1 month from dis-

use of medications (names and doses of all medications taken at continuation, even for the SSRI with the longest half-life (the ac-

the time of the survey; open-text question), consumption of addic- tive metabolite of fluoxetine, norfluoxetine, has a t½ of 7.5 days,

tive substances (current and past smoking: yes/no question with which yields approximately 94% washout after 1 month from dis-

space for details; alcohol, marijuana, cocaine: multiple-choice continuation20). The ASEX manual indicates specific score-based

items regarding use over the last 30 days), and current depression criteria highly correlated with physician-diagnosed sexual dys-

and anxiety levels as assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and De- function,21 which we used as a definition of current sexual dys-

pression Scale (HADS).18,19 The authors received written permis- function in our study. Additional criteria for high-probability

sion to use the ASEX and HADS from the copyright owners. cases aim to exclude cases in which possible alternative causes

Antidepressant doses were divided by the defined daily dose of sexual dysfunction are evident. Since the literature points to a

(DDD) for each medication, as published by the WHO Collabora- steep increase in sexual dysfunction at approximately age 50,22,23

tive Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, to create a measure it was used as a cutoff point for exclusion of age-related sexual

for dose comparison beyond specific agents (dose/DDD ratio). difficulties. Current medical conditions reported by the partici-

Case probability was defined according to the following cate- pants were searched in Google Scholar along the word "sexual,"

gories of increasing presumed likelihood of PSSD: noncase, pos- yielding 59 diseases/disorders associated with sexual dysfunction

sible case, and high-probability case; the criteria for each are listed (not including depressive and anxiety disorders, which are better

in Table 1. Subjects who reported using more than one medica- addressed by criteria 9 and 10, accordingly). Subjects who re-

tion (whether antidepressant or not) while the sexual dysfunction ported any of these conditions were not included in the high-

emerged were considered as noncases because the complexity of probability cases sample, regardless of treatment. To determine

drug combinations does not allow drawing clear conclusions the frequency of sexual adverse effects of the medications cur-

as to which drug was the culprit. Absence of any pretreatment rently taken by the participants, each was searched individually

in the databases UpToDate (2013) and Micromedex 2.0, and in

few cases where data was insufficient, also in relevant textbooks

TABLE 1. Criteria for Case Probability Categories and journal articles. Subjects taking medications of which sexual

dysfunction is a nonrare (≥1% frequency) adverse effect were not

Noncase included in the high-probability cases sample. Smokers were

One or more of the criteria for a possible case are not met allowed as high-probability cases. Subjects who reported consum-

(see below) ing alcohol more than the sex-specific low-risk drinking limits as

Possible case defined by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcohol-

All of the following:

ism (14 drinks per week for men, 7 drinks for women),24 using

marijuana on more than 2 occasions over the past 30 days (which

(1) Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction while taking one

antidepressant of the SSRI or SNRI class

corresponds to definition of "frequent" user by Schulenberg

et al25), or using cocaine even once over the same period, were

(2) As the above treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction appeared,

the patient was not taking any additional medications

not included as high-probability cases. Owing to the well-

documented association of depression and anxiety with sexual

(3) The patient reported no pretreatment sexual dysfunction

dysfunction,26 only subjects whose HADS-Depression and HADS-

(4) The antidepressant was discontinued at least 1 month before Anxiety scores were within the normal range (0–7) were included

the survey

in the high-probability cases sample. We defined genital anesthe-

(5) Sexual dysfunction persisted despite drug discontinuation, as sia as any degree of genital numbness as indicated by subject's re-

indicated by subject's ASEX scores

sponses ("somewhat numb," "very numb," or "completely numb")

High-probability case to the corresponding question in the survey. Pleasureless orgasm

All the above criteria for possible case plus all the following: was defined as a state in which orgasm can be easily achieved

(6) Subject is younger than 50 years old (ASEX-Orgasm ≤ 3) but is experienced as very unsatisfying

(7) Current medical conditions reported by the subject did not (ASEX-Satisfaction = 5).

include conditions associated with sexual dysfunction

(8) Current medications reported by the subject did not include

medications associated with sexual dysfunction Statistical Analysis

(9) The subject did not report use of addictive substances that We used SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) for statis-

may cause sexual dysfunction tical analyses. Descriptive statistics are expressed as rate (%) or

(10) Subject's HADS-Depression score is within normal mean ± standard deviation (SD). Pearson and partial correlations

range (0–7) were calculated as appropriate. One-way analysis of variance

(11) Subjects' HADS-Anxiety score is within normal was used to determine whether different groups of case probability

range (0–7) differed significantly in dose/DDD. We used linear multivariate

ASEX indicates Arizona Sexual Experience Scale; HADS, Hospital

regression analysis for the prediction of current sexual dysfunc-

Anxiety and Depression Scale. tion severity (total ASEX score). P < 0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

274 www.psychopharmacology.com © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology • Volume 35, Number 3, June 2015 Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction (PSSD)

RESULTS in this sample were men (82.6%), single (56.5%), of mean (SD)

age of 32.9 (11.4) years, most frequently from the United States

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (21.7%), the Netherlands (17.4%) or Australia (13.0%). None of

them reported using duloxetine or milnacipran. The mean (SD)

Five hundred thirty two (532) subjects consented to partici- dose/DDD was 1.74 (0.93). The medication was used for a

pate and completed the survey, within which 183 possible cases mean (SD) of 18.1 (21.5) months and discontinued 44.9 (50.1)

(34.4%) were identified, including 23 high-probability cases months before the survey. The mean (SD) ASEX score was 21.6

(12.6% of the possible cases). The possible cases sample included (3.8), and most subjects (78.3%) had genital anesthesia. The

143 men (78.1%) and 40 women (21.9%), with mean (SD) age HADS-Depression scores were 3.96 (2.38), and the HADS-

of 36.0 (11.4) years. Most subjects (53.6%) were married or in a Anxiety scores were 4.04 (1.87).

relationship. Most of them reported living in the United States

(43.7%) or the United Kingdom (13.7%), with sizable minorities

from Germany (7.1%), Canada (5.5%), and Australia (3.8%), Mood, Stress, and Sexual Dysfunction

the rest being from other countries (30.0%). The medication taken The following data were calculated using the possible cases

by the subjects when first experiencing sexual dysfunction was, sample (n = 183), except for data concerning case probability,

in order of frequency: citalopram (23.0%), escitalopram (16.4%), which was calculated using the entire survey sample (N = 532).

paroxetine (15.8%), sertraline (14.8%), fluoxetine (13.7%), Depression (HADS-D score) was weakly correlated with current

venlafaxine (9.8%), duloxetine (2.7%), fluvoxamine (2.7%), and sexual dysfunction severity (ASEX score; r = 0.32; P = 0.001),

desvenlafaxine (1.1%). Mean (SD) dose/DDD was 1.54 (0.91). but anxiety (HADS-A score) was not (r = 0.02; P = 0.845). De-

The mean (SD) duration of treatment was 28.1 (35.2) months pression and anxiety levels were significantly correlated

(range, 0.03–180 months), and the mean (SD) time since (r = 0.47; P = 0.001). Subjects who were not in a relationship

quitting the medication was 41.1 (47.3) months (range, 1.0– had higher depression scores (mean [SD] HADS-D,10.00

228.0 months). The mean (SD) ASEX score was 21.7 (3.8). The [4.97] vs 8.03[4.85]; t = 2.71; P = 0.007) and somewhat more se-

mean (SD) HADS scores were 8.95 (4.99) and 8.96 (4.37) for vere sexual dysfunction (mean [SD] ASEX,22.38[3.73] vs 21.16

the depression and anxiety subscales, accordingly. The high- [3.75]; t = 2.188; P = 0.030). Genital anesthesia score correlated

probability cases are presented in Table 2. Most of the subjects significantly with sexual dysfunction severity (ASEX score;

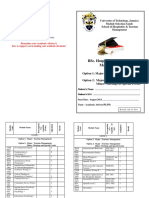

TABLE 2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the High-Probability Cases Sample (n = 23) of PSSD in Our Study

Reported Organic

Medical Conditions;

Daily Duration Time Since ASEX Specific HADS Reported Current

Case # Age (y) Sex Medication Dose (mg) of Use Quitting Score Symptoms scores (D;A) Medications

1 28 M Escitalopram 10 1 mo 2y 19 GA 1;4 Tinnitus; none

2 25 M Escitalopram 10 NR 3y 23 GA 5;6 None; none

3 30 M Desvenlafaxine 50 1.5 y 1.2 y 22 GA, PO 3;2 None; none

4 37 F Fluoxetine 20 2.5 y 10 y 26 GA 7;5 None; Zolpidem (for sleep)

5 34 M Venlafaxine 150 1y 5 mo 22 GA 7;3 None; none

6 28 F Citalopram 20 6 mo 3.5 y 21 – 3;4 None; none

7 31 M Sertraline NR 4 days 8 mo 22 GA 4;6 None; none

8 34 F Citalopram 20 2 mo 3y 25 GA 4;4 None*; none

9 45 F Fluoxetine 60 6 mo 12 y 25 GA 0;4 None; none

10 21 M Fluoxetine 40 6y 9 mo 21 GA 7;4 Scoliosis; none

11 32 M Paroxetine 20 2 mo 1.1 y 20 GA 7;5 None; none

12 33 M Citalopram 60 2y 4 mo 16 GA 1;1 None*; none

13 35 M Venlafaxine XR 150 4y 6y 10 PO 2;7 None; none

14 39 M Escitalopram 40 4y 3y 20 – 2;0 High cholesterol; Simvastatin

15 47 M Venlafaxine XR 75 5y 3.5 y 22 GA 3;3 None; none

16 34 M Fluoxetine 40 4 mo 16 y 15 – 5;3 None; none

17 41 M Escitalopram NR 6 mo 5y 20 GA 6;5 Mild headaches; none

18 26 M Sertraline 150 2y 3y 22 GA 3;6 None†; none

19 27 M Citalopram NR 3 mo 9 mo 22 GA, PO 1;1 None; none

20 27 M Citalopram 40 4 mo 4 mo 25 GA 1;3 None; none

21 33 M Fluoxetine 20 2 mo 2y 27 GA 7;5 None†; none

22 37 M Fluoxetine 20 8 mo 1 mo 30 GA 5;7 None; none

23 32 M Escitalopram NR NR 8.5 y 21 – 7;5 None; none

*Past smoker.

†

Current nonheavy smoker (≤20 cigarettes/d).

A indicates HADS-Anxiety score; D, HADS-Depression score; GA, genital anesthesia; mo, months; NR, not reported; PO, pleasureless orgasm; y,years.

© 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.psychopharmacology.com 275

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Ben-Sheetrit et al Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology • Volume 35, Number 3, June 2015

r = 0.56; P = 0.001). Although initially found to correlate with However, if the patient resumes antidepressant treatment, then

HADS-D scores (r = 0.286; P = 0.001), genital anesthesia was the current drugs are assumed to be the culprit. Regardless of

not significantly correlated with depression after controlling for how this condition is managed, the persistent nature of an impair-

ASEX score (r = 0.134; P = 0.071). There was no significant cor- ment induced by past pharmacological treatment is almost always

relation between anxiety and genital anesthesia (r = 0.08; confounded. There are 2 notable exceptions, however. First, when

P = 0.296). Subjects who had pleasureless orgasm had higher a patient develops treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction as de-

levels of depression (mean [SD] HADS-D,11.50[5.34] vs 8.56 pression and anxiety levels markedly improve in response to anti-

[4.84]; t = −2.739; P = 0.007) but not anxiety (mean [SD] depressants, it could be argued that this should be considered as

HADS-A,10.08[5.12] vs 8.79[4.24]; t = −1.358; P = 0.176), evidence that the sexual dysfunction is caused by the treatment

and this symptom predicted depression beyond ASEX score rather than the disorder being treated. The retrospective nature

(R = 0.435; F = 21.063; BPO = 4.474, BASEX = 0.529; of our study does not allow capturing this course of events, al-

P = 0.001). Pleasureless orgasm predicted case probability inde- though it may prove of great diagnostic value to the physician.

pendently from sexual dysfunction and depression severity Second, some patients experience drug-free remissions of their

(R = 0.213, F = 8.378, P = 0.001; BPO = 0.321, P = 0.001; depressive or anxiety disorders (either spontaneously or in re-

BASEX = 0.021, P = 0.001; BHADS-D = −0.009, P = 0.089). Time sponse to psychotherapy), allowing to attribute current sexual dys-

since quitting the medication did not correlate significantly with function to previous pharmacological therapy. We aimed to

ASEX scores (r = 0.06; P = 0.396) but correlated with decreased demonstrate this point by including in the high-probability cases

lubrication severity in women (r = 0.45; P = 0.004), even after sample only subjects whose HADS-Depression and HADS-

controlling for age, depression, and anxiety (r = 0.478; Anxiety scores were within normal range. A third potential aid

P = 0.003). The following were entered into linear multivariate to the diagnosis of PSSD was suggested by Bahrick,7 who pointed

regression analysis (method Enter) as independent variables in out that certain symptoms such as genital anesthesia and pleasure-

the prediction of current sexual dysfunction severity (total ASEX less orgasm seem to be associated with SSRI/SNRI treatment but

score): age, sex (as dummy variable, male = 1), relationship status are not known to be associated with any of the conditions for

(as dummy variable, in a relationship = 1), HADS-Depression which these drugs are prescribed. Since most of the participants

score, HADS-Anxiety score, and genital anesthesia score. A sig- in our study (both possible cases and noncases) reported taking

nificant model was retrieved (R = 0.631, R2 = 0.399, an SSRI/SNRI in the past, we cannot substantiate nor disprove this

F = 19.452, P = 0.001; BAge =0.040, P = 0.056; BSex = −1.754, hypothesis. It is important to note, however, that genital anesthesia

P = 0.002; BRelationship = −0.488, P = 0.313; BDepression = 0.185, did not correlate with either depression (when controlled for

P = 0.001; BAnxiety = −0.079, P = 0.186; BGenital anesthesia = ASEX score) or anxiety severity in any of the samples in our study

1.716, P = 0.000), explaining 39.9% of the total variance of (totaling in 532 subjects), raising doubt about a psychogenic etiol-

ASEX score. ogy. We found genital anesthesia to be a prominent predictor of

sexual dysfunction severity, a finding which could be explained

Exposure-Response Relationship in 2 ways. First, genital anesthesia probably causes or worsens

Dose/DDD ratios did not differ significantly between case sexual dysfunction. Decreased sensation is likely to lead to de-

probability groups in one-way analysis of variance (noncases, creased pleasure, which can result in erectile dysfunction or de-

1.50 ± 1.00; possible cases, 1.54 ± 0.91; high-probability cases, creased lubrication, and the latter may impede libido and arousal

1.74 ± 0.93; df = 2, F = 0.523; P = 0.59). Dose/DDD and treat- by means of negative feedback. Second, these 2 phenomena

ment duration did not correlate significantly with ASEX score may share a common etiological mechanism in SSRI-treated pa-

(r = − 0.90; P = 0.30). tients, namely, enhanced serotonergic load (see below for a brief

discussion on neurotoxicity). Unlike genital anesthesia, pleasure-

less orgasm was an independent predictor of both depression se-

verity and case probability. If further studies confirm that this

DISCUSSION symptom is indeed associated with both depression (as found in

The first objective of this work was to identify and character- the ASEX validity study17) and SSRI treatment, its value in the di-

ize a series of cases of PSSD, challenging the commonly accepted agnosis of PSSD may be limited. We found a significant associa-

assumption that antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in- tion between depression and current sexual dysfunction severity,

variably resolves upon drug discontinuation. Using a structured consistent with the literature.26 Depression may develop as a com-

self-report questionnaire and a validated scale for the assessment plication of persistent sexual dysfunction, or it may play a contrib-

of sexual function (ASEX), we were able to identify 183 subjects uting factor in its etiology, among other factors (including prior

who reported persistent treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction pharmacotherapy). Case probability was not significantly associ-

implicating a single SSRI/SNRI (ie, possible cases). Twenty three ated with dose/DDD. This finding could be interpreted in 2 ways.

(12.6%) of these subjects remained after taking into account many First, PSSD may represent an idiosyncratic drug reaction and may

alternative factors relevant to sexual dysfunction, including age, not be dose dependent. The rarity, severity, and unpredictability of

medical conditions, current medical therapy, use of addictive sub- this phenomenon support this option. Second, if PSSD is dose de-

stances, depression, and anxiety (ie, high-probability cases). pendent, lack of significance may have resulted owing to the small

There seems to be an inherent diagnostic challenge in PSSD, number of high-probability cases (n = 23), or secondary to an in-

illustrated by the following typical scenario. A patient sees a herent artifact created by the case definitions. Possible cases have

doctor for depression or anxiety and is given an antidepressant. by definition more severe sexual dysfunction compared to

Sexual dysfunction emerges, eventually leading to drug discontin- noncases, which may indicate low tolerability to SSRIs/SNRIs,

uation. When the patient realizes that the sexual dysfunction per- and hence may not have reached higher doses in the first place.

sists, he or she pays their doctor a visit. At this point, what would Moreover, high-probability cases have normal scores on both

the physician assume as the cause of the sexual disturbance? If the HADS-Depression and HADS-Anxiety, although they are not

patient is not currently on antidepressants and is obviously currently on antidepressants. Such patients who have achieved

stressed about his or her situation, then the re-emergence of de- drug-free remissions may have a less severe disorder (depression

pression or anxiety is naturally presumed to be the cause. or anxiety), requiring lower doses to begin with.

276 www.psychopharmacology.com © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology • Volume 35, Number 3, June 2015 Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction (PSSD)

The constellation of sexual dysfunction and genital anes- measured with the rush sexual inventory. Psychopharmacol Bull.

thesia persisting after SSRI use suggests that serotonergic neuro- 1997;33:755–760.

toxicity may play a role in PSSD. It is worth noting that 4. Bolton JM, Sareen J, Reiss JP. Genital anesthesia persisting

neurotoxicity induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, six years after sertraline discontinuation. J Sex Marital Ther.

which stimulates the release and inhibits the reuptake of sero- 2006;32:327–330.

tonin, is associated with sexual dysfunction persisting long after 5. Kauffman RP, Murdock A. Prolonged post-treatment genital anesthesia

abstinence (data indicate that axonal damage is involved).27 and sexual dysfunction following discontinuation of citalopram and

Whereas the potency of the agent is probably the cause in 3,4- the atypical antidepressant nefazodone. Open Womens Health J.

methylenedioxymethamphetamine–associated neurogenic sexual 2007;1:1–3.

impairment, we can presume that individual vulnerability may 6. Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, et al. Sexual dysfunction

have a prominent role in PSSD, as most patients treated with with antidepressive agents. Effect of the change to amineptine in

SSRIs never develop the syndrome. Persistent sexual dysfunc- patients with sexual dysfunction secondary to SSRI. Actas Esp Psiquiatr.

tion has been described in some patients treated with finasteride 1999;27:23–24.

(post-finasteride syndrome), a condition that has a similar symp-

7. Bahrick AS. Persistence of sexual dysfunction side effects after

tom profile to PSSD.14,28–30 Although the mechanism of post-

discontinuation of antidepressant medications: emerging evidence.

finasteride syndrome is unknown, it could be speculated that Open Psychol J. 2008;1:42–50.

since this 5α-reductase inhibitor decreases the rate of conversion

of testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone (DHT), it 8. Safarinejad MR, Hosseini SY. Safety and efficacy of citalopram

might hamper the direct androgen-receptor-dependent neuro- in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a double-blind

placebo-controlled, fixed-dose, randomized study.

protective effects of androgens in the brain31,32 and may thus

Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:164–169.

eventually lead to persistent sexual dysfunction.

The current study has several limitations. First, the specific 9. Csoka AB, Shipko S. Persistent sexual side effects after SSRI

characteristics of the study population, including demographic discontinuation. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:187–188.

characteristics, medical history, and willingness to volunteer to 10. Csoka AB, Bahrick AS, Mehtonen OP. Persistent sexual dysfunction

participate in the study, may represent a selection bias, which does after discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

not allow generalization of the findings. However, such gene- J Sex Med. 2008;5:227–233.

ralization was not an objective of this preliminary study. The ret- 11. SSRIs and persistent sexual dysfunction. in: Lareb quarterly report, 3e

rospective nature of study may result in recall bias, in which 2012, pg. 10–13 [Internet]: Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Center (Lareb).

patients with sexual dysfunction are more prone to remember Available from: http://www.lareb.nl/getmedia/ce215096-e980-4006-b7fb-

previous use of antidepressants. Self-report and anonymity may 6efd3a0c65b5/ 2012-3-LQR-2.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2012.

result in report biases, including underreporting of sexual dys-

12. Ekhart GC, van Puijenbroek EP. Does sexual dysfunction persist upon

function before therapy. The survey may have selectively attracted discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors? Tijdschr

respondents who wished to communicate about their disorder, Psychiatr. 2014;56:336–340.

leading to a bias favoring a higher prevalence and severity of

sexual dysfunction. Conversely, it is possible that individuals with 13. Stinson RD. The impact of persistent sexual side effects of selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors after discontinuing treatment: a qualitative

severe or significant sexual dysfunction selectively avoided the

study [dissertation]. Iowa, USA: University of Iowa; 2013. Available from:

survey, leading to an underestimation of prevalence and severity.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5061&context=etd.

It is thus clear that the current study cannot determine the inci- Accessed December 2013.

dence of PSSD. Double participation in the study was prevented

by the survey software, and the study was conducted in a closed 14. Hogan C, Le Noury J, Healy D, et al. One hundred and twenty cases

forum, limiting external abuse of the survey. Despite the afore- of enduring sexual dysfunction following treatment. Int J Risk Saf Med.

2014;26:109–116.

mentioned limitations, the current investigation adds to the emerg-

ing evidence that SSRI/SNRI-induced sexual dysfunction persists 15. Waldinger MD, van Coevorden RS, Schweitzer DH, et al. Penile anesthesia

in some patients beyond drug discontinuation and suggests that in post SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD) responds to low-power laser

this phenomenon may not be fully explained by alternative non- irradiation: a case study and hypothesis about the role of transient receptor

pharmacological factors, including depression and anxiety. Physi- potential (TRP) ion channels. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.

cians should assess sexual function prior, during, and also after ejphar.2014.11.031 [Epub ahead of print].

treatment with antidepressants and be aware of the possibility of 16. Csoka AB, Szyf M. Epigenetic side-effects of common pharmaceuticals:

PSSD. As it may have major implications on the informed consent a potential new field in medicine and pharmacology. Med Hypotheses.

and choice of therapy in depressive and anxiety disorders, further 2009;73:770–780.

research is warranted. 17. McGahuey A, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, et al. The Arizona sexual

experience scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther.

2000;26:25–40.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE INFORMATION

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. 18. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

19. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety

REFERENCES and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res.

1. Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to 2002;52:69–77.

antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29: 20. DeBattista C. Basic pharmacology of antidepressants. In: Katzung BG,

259–266. Masters SB, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic Clin Pharmacol. 12th ed. New York, NY,

2. Fava M, Rankin M. Sexual functioning and SSRIs. J Clin Psyhiatry. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2012.

2002;63:13–16. 21. Arizona Health Sciences Center, University of Arizona. ASEX© scale—

3. Zajecka J, Mitchell S, Fawcett J. Treatment-emergent changes in general instructions for clinicians administering the scale. 1997. Note:

sexual function with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as The scale and the instructions are available from The University of

© 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.psychopharmacology.com 277

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Ben-Sheetrit et al Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology • Volume 35, Number 3, June 2015

Arizona, Department of Psychiatry, for more information please visit: 26. Laurent SM, Simons AD. Sexual dysfunction in depression and anxiety:

http://psychiatry.arizona.edu/research/asex-scale-information. conceptualizing sexual dysfunction as part of an internalizing dimension.

Accessed January 13, 2015. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:573–585.

22. Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, et al. Sexual function in men 27. Parrott A. Recreational ecstasy/MDMA, the serotonin syndrome, and

older than 50 years of age: results from the health professionals follow-up serotonergic neurotoxicity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:837–844.

study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:161–168.

28. Questions and answers: Finasteride label changes [Internet]: U.S. Food and

23. Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual problems among Drug Administration (FDA). Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/

women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm299754.htm.

global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17: Accessed April 11, 2012.

39–57.

29. Irwig MS. Persistent sexual and nonsexual adverse effects of finasteride

24. Chen CM, Yi H, Falk DE, et al. Alcohol use and alcohol use in younger men. Sex Med Rev. 2014;2:24–35.

disorders in the united states: main findings from the 2001–2002

30. Irwig MS, Kolukula S. Persistent sexual side effects of finasteride for male

national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions

pattern hair loss. J Sex Med. 2011;8:1747–1753.

(NESARC). In: Hilton ME, Breslow RA, eds. U.S. Alcohol Epidemiologic

Data Reference Manual. 8th ed. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute 31. Creta M, Riccio R, Chiancone F, et al. Androgens exert direct

on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institute of Health neuroprotective effects on the brain: a review of pre-clinical evidences.

(NIH); 2006. J Androl Sci. 2010;17:49–55.

25. Schulenberg JE, Merline AC, Johnston LD, et al. Trajectories of marijuana 32. Hammond J, Le Q, Goodyer C, et al. Testosterone‐mediated

use during the transition to adulthood: the big picture based on national neuroprotection through the androgen receptor in human primary neurons.

panel data. J Drug Issues. 2005;35:255–280. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1319–1326.

278 www.psychopharmacology.com © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Are Men Under-Treated and Women Over-Treated With Antidepressants? Findings From A Cross - Sectional Survey in Sweden PDFDokument6 SeitenAre Men Under-Treated and Women Over-Treated With Antidepressants? Findings From A Cross - Sectional Survey in Sweden PDFTeressa ShawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Worksheet 1 GWS 103 (Online)Dokument6 SeitenWorksheet 1 GWS 103 (Online)Teressa ShawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Are Men Under-Treated and Women Over-Treated With Antidepressants? Findings From A Cross - Sectional Survey in Sweden PDFDokument6 SeitenAre Men Under-Treated and Women Over-Treated With Antidepressants? Findings From A Cross - Sectional Survey in Sweden PDFTeressa ShawNoch keine Bewertungen

- GWS 103 Project 2Dokument3 SeitenGWS 103 Project 2Teressa ShawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aging Resources, Generational Equality, and The Framing of The Debate Over Social Secuirty Williamson Watts Roy Framing 2009Dokument17 SeitenAging Resources, Generational Equality, and The Framing of The Debate Over Social Secuirty Williamson Watts Roy Framing 2009Teressa ShawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compresión Morbilidad Fries Annals 2003Dokument5 SeitenCompresión Morbilidad Fries Annals 2003Pedro Torres AlvarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Menstrual BodyDokument101 SeitenThe Menstrual BodyTeressa Shaw100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- (1921) Manual of Work Garment Manufacture: How To Improve Quality and Reduce CostsDokument102 Seiten(1921) Manual of Work Garment Manufacture: How To Improve Quality and Reduce CostsHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- Continue Practice Exam Test Questions Part 1 of The SeriesDokument7 SeitenContinue Practice Exam Test Questions Part 1 of The SeriesKenn Earl Bringino VillanuevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sept Dec 2018 Darjeeling CoDokument6 SeitenSept Dec 2018 Darjeeling Conajihah zakariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leadership Styles-Mckinsey EdDokument14 SeitenLeadership Styles-Mckinsey EdcrimsengreenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desktop 9 QA Prep Guide PDFDokument15 SeitenDesktop 9 QA Prep Guide PDFPikine LebelgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFDokument35 SeitenDwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFmirthafoucault100% (8)

- Produktkatalog SmitsvonkDokument20 SeitenProduktkatalog Smitsvonkomar alnasserNoch keine Bewertungen

- India TeenagersDokument3 SeitenIndia TeenagersPaul Babu ThundathilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reported SpeechDokument6 SeitenReported SpeechRizal rindawunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JIS G 3141: Cold-Reduced Carbon Steel Sheet and StripDokument6 SeitenJIS G 3141: Cold-Reduced Carbon Steel Sheet and StripHari0% (2)

- LP For EarthquakeDokument6 SeitenLP For Earthquakejelena jorgeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSC HTM - TourismDokument4 SeitenBSC HTM - Tourismjaydaman08Noch keine Bewertungen

- SASS Prelims 2017 4E5N ADokument9 SeitenSASS Prelims 2017 4E5N ADamien SeowNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Configure PowerMACS 4000 As A PROFINET IO Slave With Siemens S7Dokument20 SeitenHow To Configure PowerMACS 4000 As A PROFINET IO Slave With Siemens S7kukaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathology of LiverDokument15 SeitenPathology of Liverערין גבאריןNoch keine Bewertungen

- ML Ass 2Dokument6 SeitenML Ass 2Santhosh Kumar PNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cisco UCS Adapter TroubleshootingDokument90 SeitenCisco UCS Adapter TroubleshootingShahulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lamentation of The Old Pensioner FinalDokument17 SeitenLamentation of The Old Pensioner FinalRahulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development Developmental Biology EmbryologyDokument6 SeitenDevelopment Developmental Biology EmbryologyBiju ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Information and Communication Technology 0417/13 May/June 2022Dokument15 SeitenCambridge IGCSE™: Information and Communication Technology 0417/13 May/June 2022ilovefettuccineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evs ProjectDokument19 SeitenEvs ProjectSaloni KariyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FuzzingBluetooth Paul ShenDokument8 SeitenFuzzingBluetooth Paul Shen许昆Noch keine Bewertungen

- SLA in PEGA How To Configue Service Level Agreement - HKRDokument7 SeitenSLA in PEGA How To Configue Service Level Agreement - HKRsridhar varmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 4 - Theoretical Framework - LectureDokument13 SeitenWeek 4 - Theoretical Framework - LectureRayan Al-ShibliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iguana Joe's Lawsuit - September 11, 2014Dokument14 SeitenIguana Joe's Lawsuit - September 11, 2014cindy_georgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test 51Dokument7 SeitenTest 51Nguyễn Hiền Giang AnhNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 in 8.5 60KG PSC Sleepers TurnoutDokument9 Seiten1 in 8.5 60KG PSC Sleepers Turnoutrailway maintenanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design of Combinational Circuit For Code ConversionDokument5 SeitenDesign of Combinational Circuit For Code ConversionMani BharathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Promotion-Mix (: Tools For IMC)Dokument11 SeitenPromotion-Mix (: Tools For IMC)Mehul RasadiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV & Surat Lamaran KerjaDokument2 SeitenCV & Surat Lamaran KerjaAci Hiko RickoNoch keine Bewertungen