Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

2 5222149245129195974

Hochgeladen von

Pangala NitaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

2 5222149245129195974

Hochgeladen von

Pangala NitaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Research

JAMA Dermatology | Original Investigation

Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry Data on Contact Allergy

in Children With Atopic Dermatitis

Sharon E. Jacob, MD; Maria McGowan, MD; Nanette B. Silverberg, MD; Janice L. Pelletier, MD; Luz Fonacier, MD;

Nico Mousdicas, MD; Doug Powell, MD; Andrew Scheman, MD; Alina Goldenberg, MD, MAS

IMPORTANCE Atopic dermatitis (AD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) have a dynamic

relationship not yet fully understood. Investigation has been limited thus far by a paucity of

data on the overlap of these disorders in pediatric patients.

OBJECTIVE To use data from the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry to elucidate the

associations and sensitizations among patients with concomitant AD and ACD.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This retrospective case review examined 1142 patch test

cases of children younger than 18 years, who were registered between January 1, 2015, and

December 31, 2015, by 84 health care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician

assistants) from across the United States. Data were gathered electronically from

multidisciplinary providers within outpatient clinics throughout the United States on pediatric

patients (ages 0-18 years).

EXPOSURES All participants were patch-tested to assess sensitizations to various allergens;

history of AD was noted by the patch-testing providers.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Primary outcomes were sensitization rates to various

patch-tested allergens.

RESULTS A total of 1142 patients were evaluated: 189 boys (34.2%) and 363 girls (65.8%) in

the AD group and 198 boys (36.1%) and 350 girls (63.9%) in the non-AD group (data on

gender identification were missing for 17 patients). Compared with those without AD,

patch-tested patients with AD were 1.3 years younger (10.5 vs 11.8 years; P < .001) and had

longer history of dermatitis (3.5 vs 1.8 years; P < .001). Patch-tested patients designated as

Asian or African American were more likely to have concurrent AD (odds ratio [OR], 1.92; 95%

CI, 1.20-3.10; P = .008; and OR, 4.09; 95% CI, 2.70-6.20; P <.001, respectively). Patients with

AD with generalized distribution were the most likely to be patch tested (OR, 4.68; 95% CI,

3.50-6.30; P < .001). Patients with AD had different reaction profiles than those without AD,

with increased frequency of reactions to cocamidopropyl betaine, wool alcohol, lanolin,

tixocortol pivalate, and parthenolide. Patients with AD were also noted to have lower

frequency of reaction to methylisothiazolinone, cobalt, and potassium dichromate.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Children with AD showed significant reaction patterns to

allergens notable for their use in skin care preparations. This study adds to the current

understanding of AD in ACD, and the continued need to investigate the interplay between

these disease processes to optimize care for pediatric patients with these conditions.

Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

article.

Corresponding Author: Alina

Goldenberg, MD, MAS, Resident,

Department of Dermatology,

University of California–San Diego,

8899 University Center Lane,

JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6136 Ste 350, Loma Linda, CA 92122

Published online February 22, 2017. (a1golden@ucsd.edu).

(Reprinted) E1

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/derm/0/ by a Fudan University User on 02/28/2017

Research Original Investigation Contact Allergy in Children With Atopic Dermatitis

A

topic dermatitis (AD) and allergic contact dermatitis

(ACD) are 2 of the most commonly recognized pediat- Key Points

ric inflammatory skin disorders, but they have a dy-

Question Does having atopic dermatitis (AD) influence

namic relationship that is not fully understood. For patients with sensitization patterns and allergic contact dermatitis development

AD, concomitant undiagnosed ACD may result in treatment- among children?

resistant disease1 leading to increased patient morbidity, eco-

Findings In this retrospective case review, which included 1142

nomic burden, and lost work and/or school days.2 Diagnosis of

children younger than 18 years, those with AD had statistically

ACD in patients with AD is associated with improvements in significant increased frequency of reactions to cocamidopropyl

cutaneous symptoms as patients become able to avoid de- betaine, wool alcohol, lanolin, tixocortol pivalate, and

tected allergens that could potentially aggravate their under- parthenolide, and lower frequency of reaction to

lying AD.1 Because AD is most commonly a disease of child- methylisothiazolinone, cobalt, and potassium dichromate.

hood, and trends show that the incidence of AD and atopy are Meaning Children with AD showed significant reaction patterns

increasing,3 understanding the interplay between AD and ACD to allergens found in their skin care preparations..

is especially important in the pediatric population.

A limited number of studies have investigated the over-

lap of AD and ACD in children. Multiple studies found in-

creased sensitization rates to various allergens among chil- grading of results was not included in the survey. Positive

dren with AD, including potassium dichromate, Compositae patch-test (PPT) reactions included any reaction from macu-

mix, disperse blue, balsam of Peru, fragrance mix, and lar erythema to a 3+ reaction as defined by the International

lanolin.1,4,5 However, these study were limited by small sample Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Relevance of a PPT was

size, narrow age range, and restricted geographical distribu- interpreted and defined by the diagnosing providers and sub-

tion of test patients. One of the largest evaluations of chil- mitted within the survey, not verified by the primary investi-

dren with ACD was done by Zug et al6 from the North Ameri- gative team. The medical history and diagnostic findings were

can Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), which evaluated not verified by independent review because medical records

7 years of patch-test results from children 0 to 18 years of were not accessible to the primary investigative team. Spe-

age, with a total of 883 children within the sample. Zug et al6 cifically, the diagnosis of AD was made by the case-entering

reported that children had increased prevalence of atopic dis- provider on a case-by-case basis.

orders compared with adults. However, AD was not a pri- Within this analysis, the percentage of PPT (PPT%) was de-

mary focus of this study, and no demographic analysis was per- fined for each allergen as the sum of patients who had a posi-

formed for patients with concomitant AD and ACD.6 tive reaction divided by the total number of patients patch-

The Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry (PCDR) was de- tested for that specific allergen. The percentage of clinically

veloped to gather data on pediatric ACD, its associated demo- relevant positive patch tests (RPPT%) for each allergen was cal-

graphics, and related conditions. Established in 2014, the PCDR culated using the same approach. The percentage of having at

is a collaborative, multidisciplinary, nationwide registry of 1142 least 1 positive or relevant reaction was calculated by divid-

patch-tested children with data provided by 252 health care pro- ing the sum of patients with at least 1 positive or relevant re-

viders (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) action, respectively, by the total patients within the study.

from all 50 states.7 Herein, using data from the PCDR, we fo- Cases were arranged into 2 statistically independent groups

cus specifically on the interplay between AD and ACD, with the (patients with AD and those with non-AD medical history) based

goal of elucidating the sensitizations among patients with AD. on case-entering provider’s documentation. Data were ana-

lyzed with the independent t test for continuous variables, the

χ2 test for binary variables; odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs and

P values were confirmed through univariate logistic regres-

Methods sion using SPSS statistical software (version 22.0; SPSS Inc).

This retrospective case review was approved by the Loma Linda

University internal review board. In 2015, data for this study

were gathered from the PCDR, a multidisciplinary, electronic

data registry of patch-test results from children 0 to 18 years

Results

of age in the United States. Methodology for the PCDR devel- Overall, of 1142 pediatric patch test cases registered between

opment and a full description of providers contributing to the January 1 and December 31, 2015, by 84 unique providers, 552

registry may be found elsewhere.7 patients (49%) had a history of AD (data on concurrent AD were

The data collected for each case included a deidentified available for 98% of the entries).7 In 338 patients (30%), AD and

database collecting demographic information (age, sex, race); ACD were concurrent diagnoses reported by the data-entering

medical history, including diagnosis of AD; clinical informa- provider. The mean age of patients with AD was significantly

tion on active dermatitis (anatomic location and duration); and younger than the rest of the study populous—10.5 vs 11.8 years

logistical information regarding the patch-testing technique old (P < .001). Almost two-thirds of both AD and non-AD groups

(type of patch test used, date of patch test, time intervals for were female; sex was not significantly different between pa-

patch-test evaluation, and allergen results). Allergen results tients with AD and the rest of the study population. (Gender

were reported as either positive, relevant positive, or irritant; identification was missing for 17 patients.) Most patients were

E2 JAMA Dermatology Published online February 22, 2017 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/derm/0/ by a Fudan University User on 02/28/2017

Contact Allergy in Children With Atopic Dermatitis Original Investigation Research

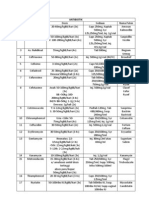

Table 1. Demographics of 1142 Children Referred for Patch Testing

AD Group Non-AD Group

Variable (n = 552)a (n = 565) OR (95% CI) P Value

Age, mean (SD), range, y 10.5 (4.7) 11.8 (4.6) (0.91-0.96) <.001

Sexb

Male 189 (34.2) 198 (36.1)

.50

Female 363 (65.8) 350 (63.9) 0.90 (0.70-1.20)

Race/ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic 274 (49.6) 377 (66.7) 0.49 (0.38-0.63) <.001

Hispanic/Latino 98 (17.8) 81 (14.3) 1.29 (0.94-1.80) .12

Asian 52 (9.4) 29 (5.1) 1.92 (1.20-3.10) .008

African American 106 (19.2) 31 (5.5) 4.09 (2.70-6.20) <.001

Location of dermatitis

Generalized 220 (39.9) 70 (12.4) 4.68 (3.50-6.30) <.001

Head

All 191 (34.6) 236 (41.8) 0.74 (0.58-0.94) .01

Face 70 (12.7) 88 (15.6) 0.79 (0.56-1.10) .17

Ears 14 (2.5) 25 (4.4) 0.56 (0.29-1.10) .10

Eyes 20 (3.6) 20 (3.5) 0.94 (0.54-1.90) >.99

Oral 8 (1.4) 38 (6.7) 0.20 (0.94-0.44) <.001

Neck 75 (13.6) 52 (9.2) 1.50 (1.10-2.30) .02

Torso 122 (22.1) 107 (18.9) 1.20 (0.91-1.60) .20

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis;

UEs 198 (35.9) 167 (29.6) 1.30 (1.00-1.70) .03 LE, lower extremity; PPT, positive

LEs 148 (26.8) 125 (22.1) 1.30 (0.90-1.70) .07 patch test result; RPPT, relevant

Groin 14 (2.5) 25 (4.4) 0.56 (0.30-1.10) .10 positive patch test result; UE, upper

Buttocks 18 (3.3) 28 (5) 0.65 (0.40-1.20) .17 extremity.

a

Duration of dermatitis, mean (SD), y 3.5 (4) 1.8 (2.6) (1.10-1.20) <.001 Data were missing for 25 cases

regarding medical history of AD.

≥1 RPPT 233 (42.2) 308 (54.5) 0.61 (0.48-0.77) <.001

b

Data on gender identification were

≥1 PPT 337 (61.1) 499 (88) 0.64 (0.49-0.82) <.001

missing for 17 patients.

listed as white non-Hispanic, and this category was signifi- population. No statistically significant difference was seen in

cantly more likely to be within the non-AD study population RPPT rates to nickel among patients with AD compared with

(P < .001). However, those patch-tested patients designated as the rest of the study sample (OR, 2.39; P = .13) (Table 2).

Asian (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.2-3.1; P = .008) or African American

(OR, 4.09; 95% CI, 2.7-6.2; P < .001) were significantly more

likely to have AD (Table 1).

Location of dermatitis prompting patch testing was sig-

Discussion

nificantly differed among patients with AD compared with Demographics

those without. Patients with AD had 4.68 times the odds of hav- Patients with AD who were referred for patch testing were, on

ing a generalized dermatitis (OR, 4.68; 95% CI, 3.5-6.3; P < .001) average, more than 1 year younger than their counterparts with-

and 1.3 times the odds of having dermatitis on the upper ex- out AD and had lived with some form of dermatitis for more

tremities (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.7; P = .03) compared with pa- than twice as long (3.5 years vs 1.6 years, respectively). Al-

tients without AD. Patients with AD had significantly longer though sex was not significantly different between AD and

history of dermatitis than those without AD: 3.5 years vs 1.8 non-AD groups, girls were patch-tested more often than boys

years (P < .001). Overall, 42.2% of patch-tested children with at a 2:1 ratio, consistent with referral patterns noted in prior

AD had at least 1 RPPT, and 61.1% had at least 1 PPT (Table 1). studies.6,8,9 It remains to be determined as to why girls are re-

Furthermore, the top 21 prevalent allergens with PPT were ferred more frequently for patch testing; however, this may in-

assessed among patients with AD, in comparison with the rest dicate that female children have a higher incidence of con-

of the study sample (Table 2). Specifically, in comparison with tact allergy. If so, increased topical product exposure may be

the patients without AD, those with AD had 7.4 times the odds a relevant sensitization route in girls.

of having an RPPT to cocamidopropyl betaine (CAPB) White children who underwent patch testing were found

(P = .008), 4.2 times the odds of having an RPPT to wool al- to be the least likely to have concomitant AD, whereas patch-

cohol (P = .047), 4 times the odds of having an RPPT to lano- tested Asians and African Americans had significantly higher

lin (P = .053), 5.3 times the odds of having an RPPT to tixocor- odds of having AD. The predilection for those with various an-

tol pivalate (P = .02), and 7.6 times the odds of having an RPPT cestries and ethnic backgrounds who are referred for patch test-

to parthenolide (P = .006). For MI, cobalt, and potassium ing to have a greater likelihood to have ACD and concomitant

dichromate, patients with AD had statistically significantly AD has not been fully elucidated in the literature, and, to our

lower odds of having an RPPT compared with the non-AD study knowledge, we are the first to report such an association. Prior

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology Published online February 22, 2017 E3

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/derm/0/ by a Fudan University User on 02/28/2017

Research Original Investigation Contact Allergy in Children With Atopic Dermatitis

Table 2. Top Allergens Among 1142 Children With AD Referred for Patch Testing

No. (%)a Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis;

Patient No. Allergen RPPT PPT OR P Valueb MCI/MI, methylchloroisothiazolinone/

1 Nickel sulfate 63 (12.0) 121 (22.0) 2.38 .13 methylisothiazolinone; OR, odds ratio;

2 Fragrance mix 1 52 (9.6.0) 63 (12.0) 0.05 .84 PPT, positive patch test result;

RPPT, relevant positive patch test

3 Balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae) 38 (7.0) 45 (8.3) 0.35 .63

result.

4 Bacitracin 29 (5.4) 41 (7.6) 0.9 .40 a

Percentages reflect the proportion of

5 Formaldehyde 28 (5.2) 34 (6.3) 1.2 .31 PPT out of the total number of

6 Cocamidopropyl betainec 27 (6.3) 36 (8.4) 7.4 .008 children with AD known to be

7 Propylene glycolc 25 (5.8) 33 (7.8) 2.8 .11 patch-tested with that allergen. The

denominator varied for each

8 Wool alcohol 25 (4.6) 29 (5.4) 4.2 .047

allergen—representing the total

9 Lanolinc 26 (6.0) 30 (7.0) 4.0 .053 number of children with AD known

10 Bronopol 19 (3.5) 23 (4.3) 0.005 >.99 to be patch-tested with that specific

11 Neomycin sulfate 18 (3.3) 33 (6.1) 3.77 .06 allergen. Unless otherwise marked,

12 Quaternium 15 18 (3.3) 27 (5.0) 1.91 .19 the denominator was 540 for

allergens; and for the allergens not

13 Colophony 17 (3.1) 17 (3.1) 3.53 .07

on the TRUE test (SmartPractice) the

14 Tixocortol-21-pivalate 15 (2.8) 17 (3.1) 5.33 .02 denominator was 429.

15 MCI/MI 13 (2.4) 18 (3.3) 2.17 .17 b

P value compares RPPT with each

16 Cobaltd 13 (2.4) 47 (8.7) 0.16 .02 allergen among patients with AD,

17 Fragrance mix 2c 13 (3.0) 19 (4.4) 3.64 .07 compared with everyone else.

c

18 MIc,d 12 (2.8) 14 (3.2) 0.16 .01 Represents allergen not on the

19 Potassium dichromate d

11 (2.0) 15 (2.8) 0.19 .03 TRUE test.

d

20 Compositae mixc 10 (2.3) 13 (3.0) 1.81 .20 For MI, cobalt, and potassium

dichromate, the ORs and P values

21 Parthenolide 10 (1.8) 11 (2.0) 7.65 .006

represent negative association.

large-scale assessments of patch-tested patients by the NACDG sensitizing agents.16,19 With our current data set, it is not pos-

may have had a type II error in assessing the component of race sible to separate severe AD from mild to moderate AD; there-

in the association of AD and ACD because it was noted that blacks fore, further research is necessary to elucidate this point.

were underrepresented in NACDG studies.10,11 Possible theo-

ries for our findings among African American and Asian pa- Allergens

tients with AD include a possibility that they are more likely to Certain trends in sensitization have been noted in our study. Many

be referred for patch testing because of increased rates of of the most common allergens, such as fragrance mix, balsam of

treatment-resistant AD as associated with filaggrin mutations,12 Peru, bacitracin, formaldehyde, or propylene glycol, were found

underlying genetic predilection for AD,12 reduced minority ac- in similar ratios across both groups (patients with AD and non-

cess to epicutaneous allergy testing, or more frequent misdi- AD). Nickel, for example, is the most common positive allergen,

agnosis of AD in these racial groups. Conversely, Asian and Afri- but there was no significant difference in rates of PPT from pa-

can American patients without AD may have been less likely to tients with AD compared with those without AD, consistent with

be referred for patch testing for various reasons and, thus, were results of previous studies.4 Specifically, sensitization to 5 aller-

not captured by our data registry. Future larger studies are nec- gens was noted more frequently in patients with AD than those

essary to further elucidate the aforementioned associations be- without AD to a statistically significant degree: CAPB, wool

tween AD and ACD across diverse populations. alcohol, lanolin, tixocortol pivalate, and parthenolide (a compo-

nent of Compositae). These sensitizers are frequently associated

Dermatitis Type with topical medicaments and skin care products.

Patients with generalized dermatitis were significantly more likely Patients with AD face inherent amplified risk of sensitiza-

to be patch-tested than those with other distributions. This find- tion because they are primarily treated with topical regimens

ing is consistent with those of other studies, such as the study by leading to increased exposure to product-based chemicals, they

Isaksson et al,1 which found that scattered generalized dermati- pathophysiologically have an impaired epidermal barrier, and

tis was the most common distribution in patch-tested children. these chemicals have been reported to have potentially en-

Patch-tested patients with AD were less likely to have a PPT hancing absorption through the skin.15,20-23

and RPPT than those in the non-AD group. According to one Cocamidopropyl betaine is a surfactant composed of a co-

pathophysiologic theory, this finding may be due to an under- conut oil derivative combined with dimethylaminopropyl-

lying misbalanced TH1/TH2 ratio in severe atopy.13-16 It has been amine and monochloroacetic acid. It is frequently found in

noted that patients with severe AD have a conspicuously lower shampoos, cleansers, contact lens solutions, and antiseptics.24

rate of ACD compared with the general population, and com- In 2004, it was named “Allergen of the Year” by the American

pared with those with mild to moderate AD.17-19 TH1 response Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) and has been noted as an

is limited in severe atopy, with an underlying increase in TH2; emerging allergen in pediatrics, especially in younger age

however, TH1 is critical in development of ACD; thus, these groups.4,25 Our findings correlated with those of other studies,

patients with severe AD are in a sense protected from highly such as Shaughnessy et al,20 who noted that atopic patients were

E4 JAMA Dermatology Published online February 22, 2017 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/derm/0/ by a Fudan University User on 02/28/2017

Contact Allergy in Children With Atopic Dermatitis Original Investigation Research

more likely to be allergic to CAPB, and Zug et al,6 who found that Potassium dichromate, an inorganic salt, used in manufac-

there was an increased prevalence of PPT to amidoamine, a pre- turing and construction. Historically, those at risk for ACD to chro-

cursor to CAPB. The frequency of sensitization in patients with mium were textile workers, leather tanners, smelters, and con-

mild to moderate AD may be related to increased absorption, struction workers who work with cement.24 Similar to cobalt, it

due to both the penetrating nature of CAPB and the inherent sus- is used as a pigment in yellow and green tattoo inks, green felt

ceptibility for absorption in AD skin.20-22 fabric, cosmetics, radiator coolants, and dental and orthopedic

Parthenolide is a sesquiterpene lactone found in Compositae implants.24 Presumably, in children, sensitization to potassium

plants, such as ragweed, feverfew, dandelions, sunflowers, and dichromate is more likely due to pigments rather than occupa-

daisies.24 Exposure to parthenolide may occur in nature, and is tional metal work. Our findings that potassium dichromate was

associated with summer-exacerbated dermatitis and airborne- skewed toward patients without AD are not fully in concordance

pattern dermatitis, or as a component of topical preparations such with other studies. For example, Belloni-Fortina et al4 found that

as moisturizers and cleansers.24,26 While our study showed that Italian children with AD had greater prevalence in PPT to potas-

patients with AD had significantly higher rates of allergy to par- sium dichromate. Future larger studies are necessary to further

thenolide, the same was not true for Compositae, suggesting that elucidate the relationship of potassium dichromate sensitivity

other elements of Compositae may more frequently be respon- in patients with AD with specific focus on relevant sources of

sible for sensitization in patients without AD. exposure in children worldwide.

Lanolin is a compound of esters, polyesters, alcohols, Overall, our study provides vital information on the relation-

and acids extracted from natural wool by using solvents or ship between AD and ACD in pediatric patch-tested patients in

detergents.4,27 It is a popular component of many skin prepara- the United States. This data set demonstrated that of children

tions, especially commonly used products in AD, because of its evaluated with patch testing, those who had an underlying his-

properties as an emollient, moisturizer, emulsifier, adhesive, and tory of AD tended to be significantly younger, a higher percent-

plasticizer.24 Because lanolin is a natural compound, it varies in age were of Asian or African American descent, and they were

composition based on its source and processing methods, ex- more likely to have a generalized-distribution and/or forearm dis-

plaining why some patients may tolerate certain lanolin prepa- ease and prolonged duration dermatitis compared with those

rations but not others.6,24,28 Wool alcohols may be removed from without AD. The allergens found to have significantly higher rates

lanolin, and this refined lanolin has been noted to elicit fewer re- of PPT and RPPT in patients with AD compared with those with-

sponses than lanolin with retained wool alcohol.24 out AD were ones commonly found in over-the-counter skin care

Tixocortol is a class A corticosteroid found in nasal sprays, products associated with either treatment of AD or gentle skin

inhalers, topical hemorrhoid preparations, and buccal and care, including CAPB, wool alcohol, lanolin, tixocortol pivalate,

throat medications. Its use in nasal sprays is noteworthy be- and parthenolide. Patients with AD had notably lower rates of PPT

cause many patients with AD may also be using these to treat or RPPT to MI.

another significant atopic syndrome, allergic rhinitis. Al-

Limitations

though tixocortol is not typically an ingredient in topical

Our study had several limitations. Our results may have been af-

medicaments,24 other class A corticosteroids, including hy-

fected by misclassification bias because our data were gathered

drocortisone, are frequently available over the counter.

from a variety of providers, which could lead to possible variabil-

Sensitization to 3 specific allergens was found to be sta-

ity in classifying patients as having AD, a relevant positive re-

tistically more common in patients without AD. These were

sponse, or a particular distribution of dermatitis. The variability

methylisothiazolinone (MI), cobalt, and potassium dichro-

in protocol and antigen panels from patch tests performed by the

mate. MI is a preservative that is commonly used as a cos-

enrolled providers heightens this potential bias. In addition, be-

metic preservative for its activity against bacteria and fungi.

cause the rates of positive and relevant positive results depend

MI has been well established as a potent allergen, similar to

on the relative frequency of allergens tested, the overall results

poison ivy. Following with the theory of TH1/TH2 imbalance,3

may have been affected by differences in the types of patch tests

patients with AD would be less likely to be sensitized to strong

used by individual providers, possibly leading to certain allergens

sensitizers than their counterparts without AD,29 which is con-

being overrepresented or underrepresented. Because the primary

sistent with our findings on MI.

study investigators did not have access to patient medical records,

Cobalt is a metal that is commonly combined with other

no confirmation of AD status or any additional medical history

metals, such as nickel.24 These cobalt alloys are then used in

was available as a quality-control measure. Finally, our results may

commonplace items (eg, jewelry, dental and orthopedic im-

also be privy to selection bias for the providers who registered into

plants, and belt buckles).24 Cobalt may also be used as pig-

the study, those who entered cases into the registry, and ulti-

ment for porcelain and glass, watercolor paints, crayons, tat-

mately, the patients evaluated by these providers—because they

toos, and hair dye. Historically, cobalt allergy was seen to be

may not be representative of the general population.

inexorably linked to concomitant exposure to nickel. How-

ever, it is increasingly recognized as an independent sensitizer.30

Two studies31,32 from the 1980s and 1990s noted cobalt PPT in-

dependent of nickel PPT at rates ranging from 21% to 32%, and Conclusions

the most recent NACDG data showed 40% of patients with PPT Future larger studies are necessary to further elucidate the results

to cobalt did not have PPT to nickel.30 Cobalt was named presented in this discussion. To date, the PCDR continues to pro-

“Allergen of the Year” in 2016 by the ACDS.30 vide the largest comprehensive collection of US-only pediatric

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology Published online February 22, 2017 E5

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/derm/0/ by a Fudan University User on 02/28/2017

Research Original Investigation Contact Allergy in Children With Atopic Dermatitis

patch-test cases from which ongoing research findings and ques- is needed to shed light on the global and local epidemic of ACD,

tions may continue to stem. Continued collaboration between pa- and to prevent future morbidity from commercial allergens to our

tients, health care providers, manufacturers, and policy makers children.

ARTICLE INFORMATION REFERENCES a systematic review [published online September

Accepted for Publication: December 22, 2016. 1. Isaksson M, Olhardt S, Rådehed J, Svensson Å. 17, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15065

Published Online: February 22, 2017. Children with atopic dermatitis should always be 16. Kohli N, Nedorost S. Inflamed skin predisposes

doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6136 patch-tested if they have hand or foot dermatitis. to sensitization to less potent allergens. J Am Acad

Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(5):583-586. Dermatol. 2016;75(2):312-317.e1.

Author Affiliations: Department of Dermatology,

Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, California 2. Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al; American 17. Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Linneberg A, Menné

(Jacob); Department of Internal Medicine, Loma Academy of Dermatology Association; Society for T, Engkilde K. The association between contact

Linda University, Loma Linda, California Investigative Dermatology. The burden of skin sensitization and atopic disease by linkage of a

(McGowan); Departments of Dermatology and diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American clinical database and a nationwide patient registry.

Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Academy of Dermatology Association and the Allergy. 2012;67(9):1157-1164.

New York, New York (Silverberg); Department of Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad 18. Rystedt I. Contact sensitivity in adults with

Pediatric Dermatology, Eastern Maine Medical Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490-500. atopic dermatitis in childhood. Contact Dermatitis.

Center, Bangor (Pelletier); University of Vermont 3. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Robbins SL, 1985;13(1):1-8.

School of Medicine, Burlington (Pelletier); Cotran RS. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of 19. Uehara M, Sawai T. A longitudinal study of

Department of Allery Immunology, State University Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2005. contact sensitivity in patients with atopic

of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York 4. Belloni Fortina A, Fontana E, Peserico A. Contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125(3):366-368.

(Fonacier); Department of Allery Immunology, sensitization in children: a retrospective study of

Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola (Fonacier); 20. Shaughnessy CN, Malajian D, Belsito DV.

2,614 children from a single center. Pediatr Dermatol. Cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity in patients

Department of Dermatology, Indiana University 2016;33(4):399-404.

Health, Indianapolis (Mousdicas); Department of with atopic dermatitis: reactivity to surfactants. J Am

Dermatology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City 5. Herro EM, Matiz C, Sullivan K, Hamann C, Jacob Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(4):704-708.

(Powell); Clinical Dermatology, Northwestern SE. Frequency of contact allergens in pediatric 21. Steele JC, Bruce AJ, Davis MD, Torgerson RR,

University, Chicago, Illinois (Scheman); Department patients with atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Drage LA, Rogers RS III. Clinically relevant patch test

of Dermatology, University of California–San Diego, Dermatol. 2011;4(11):39-41. results in patients with burning mouth syndrome.

San Diego (Goldenberg). 6. Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing Dermatitis. 2012;23(2):61-70.

Author Contributions: Drs Jacob and Goldenberg, in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the 22. Mertens S, Gilissen L, Goossens A. Allergic

had full access to all of the data in the study and North American Contact Dermatitis Group. contact dermatitis caused by cocamide

take responsibility for the integrity of the data and Dermatitis. 2014;25(6):345-355. diethanolamine. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75(1):

the accuracy of the data analysis. 7. Goldenberg A, Jacob SE. Demographics of US 20-24.

Study concept and design: Jacob, Goldenberg. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry providers. 23. Jakasa I, de Jongh CM, Verberk MM, Bos JD,

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All Dermatitis. 2015;26(4):184-188. Kezić S. Percutaneous penetration of sodium lauryl

authors. 8. Zug KA, McGinley-Smith D, Warshaw EM, et al. sulphate is increased in uninvolved skin of patients

Drafting of the manuscript: Jacob, McGowan, Contact allergy in children referred for patch with atopic dermatitis compared with control

Scheman, Goldenberg. testing: North American Contact Dermatitis Group subjects. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):104-109.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important data, 2001-2004. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(10):

intellectual content: All authors. 24. Marks JG, Elsner P, DeLeo VA. Contact

1329-1336. Occupational Dermatology. 3rd ed. St Louis, MO:

Statistical analysis: Jacob, McGowan, Goldenberg.

Obtained funding: Jacob, Goldenberg. 9. Hammonds LM, Hall VC, Yiannias JA. Allergic Mosby; 2002.

Administrative, technical, or material support: contact dermatitis in 136 children patch tested 25. Jacob SE, Amini S. Cocamidopropyl betaine.

Jacob, Silverberg, Fonacier, Goldenberg. between 2000 and 2006. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48 Dermatitis. 2008;19(3):157-160.

Supervision: Jacob. (3):271-274.

26. Belloni Fortina A, Romano I, Peserico A.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Jacob received 10. Deleo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The Contact sensitization to Compositae mix in children.

an American Contact Dermatitis Society Mid-Career association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(5):877-880.

Development award to support an education North American Contact Dermatitis Group,

1998-2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27(5):288-292. 27. Jovanović M, Poljacki M, Duran V, Vujanović L,

endeavor in information technology acquisition in Sente R, Stojanović S. Contact allergy to

association with this project. She was the 11. Deleo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect Compositae plants in patients with atopic

coordinating principal investigator for the PREA-1 of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am dermatitis. Med Pregl. 2004;57(5-6):209-218.

and PREA-2 Trials. No other disclosures are Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2)(Suppl Understanding):

reported. S107-S112. 28. Giménez-Arnau AM; Scientific Committee Of

Consumer Safety-SCCS. Opinion of the Scientific

Funding/Support: This study was supported in 12. Margolis DJ, Gupta J, Apter AJ, et al. Filaggrin-2 Committee on Consumer safety (SCCS): opinion on

part by Society for Pediatric Dermatology pilot variation is associated with more persistent atopic the safety of the use of methylisothiazolinone (MI)

project grant. dermatitis in African American subjects. J Allergy (P94), in cosmetic products (sensitisation only).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding source Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):784-789. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;76:211-212.

had no role in the design and conduct of the study; 13. Guillet G, Guillet MH, Dagregorio G. Allergic 29. Rees J, Friedmann PS, Matthews JN. Contact

collection, management, analysis, and contact dermatitis from natural rubber latex in sensitivity to dinitrochlorobenzene is impaired in

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or atopic dermatitis and the risk of later type I allergy. atopic subjects: controversy revisited. Arch Dermatol.

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53(1):46-51. 1990;126(9):1173-1175.

the manuscript for publication. 14. Boone M, Lespagnard L, Renard N, Song M, 30. Fowler JF Jr. Cobalt. Dermatitis. 2016;27(1):3-8.

Additional Contributions: We thank Susan Rihoux JP. Adhesion molecule profiles in atopic

Nedorost, MD, Director, Graduate Medical dermatitis vs. allergic contact dermatitis: 31. Rystedt I, Fischer T. Relationship between nickel

Education, UH Cleveland Medical Center, and pharmacological modulation by cetirizine. J Eur and cobalt sensitization in hard metal workers.

Professor, Dermatology, CWRU School of Medicine, Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14(4):263-266. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9(3):195-200.

for insightful review and mentorship. She was not 15. Halling-Overgaard AS, Kezic S, Jakasa I, 32. Kranke B, Aberer W. Multiple sensitivities to

compensated for her assistance. Engebretsen KA, Maibach H, Thyssen JP. Skin metals. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34(3):225.

absorption through atopic dermatitis skin:

E6 JAMA Dermatology Published online February 22, 2017 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/derm/0/ by a Fudan University User on 02/28/2017

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Approach To Jundiced PatientDokument2 SeitenApproach To Jundiced Patientmelinda SilalahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chiu 2018Dokument10 SeitenChiu 2018Pangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Open Ophthalmology JournalDokument10 SeitenThe Open Ophthalmology JournalPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emergency Medicine Manegement of Severe Alcohol WithdrawalDokument7 SeitenThe Emergency Medicine Manegement of Severe Alcohol WithdrawalPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JMentalHealthHumBehav22288-1958238 052622Dokument9 SeitenJMentalHealthHumBehav22288-1958238 052622Pangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Testosterone Therapy: Many Players and Much Controversy: VOL. 103 NO. 5 / MAY 2015Dokument2 SeitenTestosterone Therapy: Many Players and Much Controversy: VOL. 103 NO. 5 / MAY 2015Pangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety,.en - Id-1Dokument23 SeitenA Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety,.en - Id-1Pangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BanerjeeG JohnsonMIDokument11 SeitenBanerjeeG JohnsonMIPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isolasi Candida Albicans Dari Swab Mukosa Mulut Penderita Diabetes Melitus Tipe 2Dokument7 SeitenIsolasi Candida Albicans Dari Swab Mukosa Mulut Penderita Diabetes Melitus Tipe 2RhmaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Academy Product Order Form - 040317Dokument6 Seiten2017 Academy Product Order Form - 040317Pangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EphedrineDokument20 SeitenEphedrinePangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence of Vitreous Floaters in A Community Sample of Smartphone UsersDokument4 SeitenPrevalence of Vitreous Floaters in A Community Sample of Smartphone UsersPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EphedrineDokument20 SeitenEphedrinePangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muhammad Hassaan Ali - MM31DecDokument8 SeitenMuhammad Hassaan Ali - MM31DecPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bjophthalmol 2017 311801.full PDFDokument7 SeitenBjophthalmol 2017 311801.full PDFPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamic Postural-Stability Deficits After Cryotherapy To The Ankle JointDokument12 SeitenDynamic Postural-Stability Deficits After Cryotherapy To The Ankle JointPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Length Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926Dokument5 SeitenFull Length Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926Pangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sodium Fluorescein Staining of The Cornea For The PDFDokument5 SeitenSodium Fluorescein Staining of The Cornea For The PDFPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Prevalence of An I Some Trop I ADokument22 SeitenThe Prevalence of An I Some Trop I APangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mehdiophth 6 063 PDFDokument4 SeitenMehdiophth 6 063 PDFPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijcem0008828 PDFDokument6 SeitenIjcem0008828 PDFPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Herpes Dos PDFDokument6 SeitenHerpes Dos PDFAgustin Ivan GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Length Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926Dokument5 SeitenFull Length Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926Pangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Dosis Dan Sediaan ObatDokument5 SeitenDaftar Dosis Dan Sediaan ObatVenessa Rudy Pranata97% (38)

- 1 SMDokument4 Seiten1 SMPangalanitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0019 2A Neurologia AngolDokument5 Seiten0019 2A Neurologia AngolPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 413729Dokument5 Seiten413729Rima WulansariNoch keine Bewertungen

- ScleritisDokument3 SeitenScleritisPangala NitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Serbian Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research) Updates On The Treatment of PterygiumDokument6 Seiten(Serbian Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research) Updates On The Treatment of PterygiumRahmayani IsmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Characteristics and Visual Outcomes PDFDokument10 SeitenClinical Characteristics and Visual Outcomes PDFAnggie Pradetya MaharaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Insomnia: Management of Underlying ProblemsDokument6 SeitenInsomnia: Management of Underlying Problems7OrangesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypersensitivity: Dr. Amit Makkar, Sudha Rustagi Dental CollegeDokument117 SeitenHypersensitivity: Dr. Amit Makkar, Sudha Rustagi Dental Collegeamitscribd1Noch keine Bewertungen

- DMSCO Log Book Vol.3 7/1925-6/1926Dokument109 SeitenDMSCO Log Book Vol.3 7/1925-6/1926Des Moines University Archives and Rare Book RoomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Listening To and Making Facilitates Brain Recovery ProcessesDokument2 SeitenListening To and Making Facilitates Brain Recovery Processestonylee24Noch keine Bewertungen

- NHS LA - Duty of Candour 2014 - SlidesDokument10 SeitenNHS LA - Duty of Candour 2014 - SlidesAgnieszka WaligóraNoch keine Bewertungen

- SATO METHOD: Unique Qigong Originated in Japan (Part 1)Dokument18 SeitenSATO METHOD: Unique Qigong Originated in Japan (Part 1)kkkanhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Academy For Five Element Acupuncture Catalog 2013Dokument72 SeitenAcademy For Five Element Acupuncture Catalog 2013Shari Blake40% (5)

- NCP 1activity Intolerance N C P BY BHERU LALDokument1 SeiteNCP 1activity Intolerance N C P BY BHERU LALBheru LalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Biochemistry Past PaperDokument7 SeitenClinical Biochemistry Past PaperAnonymous WkIfo0P100% (1)

- Drug Study of FractureDokument3 SeitenDrug Study of FractureMarijune Caban ViloriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 27 Chest InjuriesDokument70 SeitenChapter 27 Chest Injuriesventus virNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chronic Care ManagementDokument8 SeitenChronic Care ManagementJubyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infection Control Risk Assessment Tool 1208Dokument7 SeitenInfection Control Risk Assessment Tool 1208sostro0% (1)

- Types of Dosage FormsDokument92 SeitenTypes of Dosage Formsneha_dand1591Noch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Safety: Fury MaulinaDokument16 SeitenPatient Safety: Fury MaulinaMuhammad Ezyra Widya AqshalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Satisfaction SurveyDokument3 SeitenPatient Satisfaction SurveyGlady Jane TevesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Horizontal Jaw RelationDokument101 SeitenHorizontal Jaw Relationruchika0% (1)

- EMQ Samples MicrobiologyDokument5 SeitenEMQ Samples MicrobiologyHugh JacobsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracy Terrones Resume 1Dokument2 SeitenTracy Terrones Resume 1api-315217520Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lung Contusion & Traumatic AsphyxiaDokument17 SeitenLung Contusion & Traumatic AsphyxiaLady KeshiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Assessment Portfolio Course SummaryDokument3 SeitenHealth Assessment Portfolio Course Summaryapi-507520601Noch keine Bewertungen

- Study Phenomenology: Experience of Chronic Kidney Failure Patients of Aspects Psychosocial in Hospital JambiDokument7 SeitenStudy Phenomenology: Experience of Chronic Kidney Failure Patients of Aspects Psychosocial in Hospital JambiInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- NICU Protocol 100Dokument76 SeitenNICU Protocol 100Catherine Lee100% (1)

- Elite Shoulder System: Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair With TheDokument16 SeitenElite Shoulder System: Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair With Theapi-19808945Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bathing An Adult ClientDokument8 SeitenBathing An Adult ClientXoisagesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Technologist Job DescriptionDokument2 SeitenSurgical Technologist Job DescriptionMeha FatimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PharmacistDokument3 SeitenPharmacistasakura95Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2Dokument2 SeitenModule 2Duchess Juliane Jose MirambelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kyphosis & LordosisDokument14 SeitenKyphosis & LordosisTrixie Marie Sabile Abdulla100% (3)