Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Behavioral Activation in Breast Cancer Patients

Hochgeladen von

Andreea NicolaeOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Behavioral Activation in Breast Cancer Patients

Hochgeladen von

Andreea NicolaeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Clinical Case Studies

http://ccs.sagepub.com/

Behavioral Activation of a Breast Cancer Patient With Coexistent Major Depression

and Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Maria E. A. Armento and Derek R. Hopko

Clinical Case Studies 2009 8: 25

DOI: 10.1177/1534650108327474

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://ccs.sagepub.com/content/8/1/25

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Clinical Case Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://ccs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://ccs.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://ccs.sagepub.com/content/8/1/25.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Jan 12, 2009

What is This?

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Clinical Case Studies

Volume 8 Number 1

February 2009 25-37

© 2009 Sage Publications

10.1177/1534650108327474

Behavioral Activation of a Breast http://ccs.sagepub.com

hosted at

Cancer Patient With Coexistent http://online.sagepub.com

Major Depression and Generalized

Anxiety Disorder

Maria E. A. Armento

Derek R. Hopko

University of Tennessee

Recently developed behavioral activation interventions have shown promise in effectively

treating depression through increasing value-based activity levels that elicit response-

contingent reinforcement. This case study highlights the implementation of behavioral

activation to a breast cancer patient with major depression and generalized anxiety disorder,

applied within the context of a medical center oncology clinic. Following an eight-session

behavioral activation protocol, the patient demonstrated notable decreases in self-reported

depressive and anxious symptoms and an overall increase in quality of life and medical

functioning. These treatment gains were maintained through 6-month follow-up. Consistent

with an accumulating literature, these data support behavioral activation as an effective and

parsimonious intervention for individuals with depression and concurrent medical problems

such as breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer; behavioral activation; depression; anxiety

1 Theoretical and Research Basis

The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 180,000 cases of invasive

breast cancer and 62,000 cases of (ductal or lobular) carcinoma in situ will be diagnosed

among U.S. women in the upcoming year. Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed

cancer type among women (American Cancer Society, 2007; Dausch et al., 2004) and the

prevalence rate of clinical depression in breast cancer patients may approximate 18%-57%

(Badger, Sergrin, Dorros, Meek, & Lopez, 2007; Dausch et al., 2004; Monti, Mago, &

Kunkel, 2005). Researchers have investigated the short- and long-term effects that psycho-

logical distress (i.e., depression and anxiety) may have on women with breast cancer.

Emotional distress may be associated with increased difficulty coping with side effects of

cancer treatment, more health complaints, more significant physical and functional impair-

ment if cancer recurs following treatment, and possibly a higher risk of mortality depending

on the stage of breast cancer and onset of depression (Badger et al., 2007; Hjerl et al., 2003;

Authors’ Note: Please address correspondence to Derek R. Hopko, 307 University of Tennessee–Knoxville,

Department of Psychology, Room 301D, Austin Peay Building, Knoxville, TN 37996-0900; e-mail:

dhopko@utk.edu.

25

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

26 Clinical Case Studies

Monti et al., 2005). The stress associated with being diagnosed and treated for breast cancer

can be immense, significantly increasing depression and anxiety, reducing quality of life, and

decreasing engagement in rewarding activities and participation in social behaviors (Badger

et al., 2007; Dausch et al., 2004; Deshields, Tibbs, Fan, & Taylor, 2006; Hopko & Lejuez,

2007; Kissane et al., 2004; Monti et al., 2005; Wong-Kim & Bloom, 2005).

Psychological interventions for breast cancer patients have included pharmacological

and/or cognitive-behavioral stress management techniques conducted in individual, group,

or family formats (Andersen, 1992; Antoni et al., 2001; Baum & Andersen, 2001; Kissane

et al., 2004; McGregor et al., 2004; Ronson & Razavi, 2000; Speca, Carlson, Goodey, &

Angen, 2000; Trisjsburg, van Knippenberg, & Rijpma, 1992). Interventions differ in goals

and strategies depending on presenting problems, stage of disease, and whether chemother-

apy or radiotherapy is provided. Specific psychosocial interventions have included psy-

choeducational strategies, supportive psychotherapy, cognitive restructuring, relaxation

training, problem-solving and social skills training, biofeedback, and hypnosis (Antoni et al.,

2001; Golden & Gersh, 1990; Moorey, Greer, Bliss, & Law, 1998; Nezu, Nezu, Houts,

Friedman, & Faddis, 1999). However, well-designed treatment outcome research assessing

the relative efficacy of these approaches has been minimal, and studies examining their

efficacy among cancer patients with well-diagnosed depression is greatly lacking (Hopko

et al., 2008; Spiegel & Giese-Davis, 2003). Indeed, it is clear that depression in breast can-

cer patients may be significantly underdiagnosed and undertreated (Badger, Braden,

Mishel, & Longman, 2004; McQuaid et al., 1999; Spiegel & Giese-Davis, 2003).

A recent revitalization of behavioral interventions for depression (Hopko & Lejuez, 2007;

Lejuez, Hopko, & Hopko, 2002; Martell, Addis, & Jacobson, 2001) has focused on behav-

ioral activation approaches that show promise in effectively treating depression through sys-

tematically increasing value-based activity levels that elicit increased response-contingent

reinforcement (Dimidjian et al., 2006; Hollon, 2001; Hopko et al., 2005, 2008; Hopko,

Lejuez, Ruggiero, & Eifert, 2003b; Jacobson, Dobson, Truax, & Addis, 1996). Behavioral

theories of depression posit that decreased response-contingent positive reinforcement

(RCPR) or punishment of nondepressive behaviors and/or reinforcement of depressive

behaviors result in increased depressive affect (Ferster, 1973; Lewinsohn, 1974). Behavioral

activation for depressed cancer patients (Hopko & Lejuez, 2007) has several features that not

only make it a viable intervention for a medical care setting (e.g., uncomplicated, time effi-

cient) but also has aspects that may be particularly appealing for cancer patients. First, the

time efficiency not only better meets the demands of a medical care environment but also the

needs of cancer patients who may already be physically and emotionally overwhelmed by

their cancer treatment. Second, behavioral activation is specifically designed to encourage

healthy nondepressive behavior by way of guided activity leading to an increase in “control”

over one’s life (and overt behavior), an attribute that may be useful in restoring the loss of

control often experienced by cancer patients (Twillman & Manetto, 1998). Third, behavioral

activation addresses components deemed essential in the effective treatment of breast can-

cer patients with mental health problems that include social and family support, emotional

expression, the reordering of life priorities, and issues of symptom control (Spiegel, 1999).

The structure of the treatment also is compatible with the structured psychoeducational

intervention model for cancer patients whereby health education, stress management, and

behavioral coping skills (and avoidance reduction) are targeted (Fawzy, Fawzy, & Canada,

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Armento, Hopko / Behavioral Activation 27

2001). Finally, behavioral activation allows for a flexible treatment that can be tailored to the

unique needs of patients taking into consideration differences in patient demographics, treat-

ment goals, and coexistent psychological and medical symptoms. This case study represents

an exploration of the effectiveness of behavioral activation in treating a patient with breast

cancer and coexistent major depression and generalized anxiety disorder.

2 Case Presentation

The patient was a 58-year-old married White female with 4 years of college education

and a career as a nurse. At the commencement of therapy, she was unemployed due to knee

surgery and was not actively seeking employment.

3 Presenting Complaints

Upon entering therapy, the patient reported she was experiencing depressive and anxious

symptoms. Among her depressive symptoms was a depressed mood that had been present

for 2 years, starting with her breast cancer diagnosis. She also reported significant loss of

energy and impaired concentration along with moderate feelings of worthlessness, hyper-

somnia, and a decrease in appetite. Generalized anxiety symptoms also were reported that

included persistent and uncontrollable worry about a number of life areas such as work,

family, finances, social issues, and personal health. Psychosomatic symptoms of anxiety

included significant difficulty concentrating, becoming easily fatigued, moderate muscle

tension, sleep difficulties, and mild irritability. The patient reported the onset of anxiety

symptoms about a year prior to entering therapy, precipitated by knee surgery that affected

her ability to work. The patient reported utilizing avoidant behaviors to try and reduce her

anxious thoughts (e.g., thought suppression, watching television, sleeping excessively).

These avoidant behaviors became linked to her depressed mood, which further inhibited her

from engaging in previously rewarding overt behaviors. Another complication to this

patient’s situation were two significant Axis III problems (i.e., a breast cancer diagnosis 2

years prior to therapy and knee surgery 1 year prior) that required her to reevaluate how

current behavioral patterns and life goals might be changed as a function of these health

issues. These precipitators increased anxiety about her future. Although some previously

emitted positive behaviors had been discontinued due to avoidance and decreased motiva-

tion associated with depressed affect, decreased engagement in other previously reinforced

behaviors (e.g., work activities, health behaviors) were more directly related to physical

limitations.

4 History

As stated, the patient’s depressive and anxiety symptoms had been present for approxi-

mately 2 years and 1 year, respectively. The primary events proximal to the onset of these

symptoms were the patient’s diagnosis of breast cancer 2 years earlier and difficulties

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

28 Clinical Case Studies

recovering from knee surgery about a year earlier. The patient was diagnosed with Stage 2

breast cancer (left laterality) with a tumor size of 2.1 cm. She had positive estrogen and

progesterone receptor status and was negative for the HER-2/NEU gene. Subsequent to the

cancer diagnosis, the patient had a lumpectomy followed by radiation and chemotherapy.

The patient reported previous episodes of depression that included two psychiatric inpa-

tient hospitalizations during the 1980s and one hospitalization for alcohol addiction (1989)

that appeared to function as a maladaptive strategy to cope with memories of an abusive

childhood. The patient reported that her father frequently was physically abusive during her

youth and that she often experienced migraine headaches and depressive affect which she

associated with this abuse. The patient indicated that vivid memories of her childhood

abuse began to manifest during the 1980s and that alcohol abuse seemed to be the most

effective strategy by which to inhibit these memories. She initially engaged in psychother-

apy in the late 1980s and remained in therapy for about 5 years. The patient reported great

improvement following psychotherapy that focused on using cognitive-behavioral therapy

to develop coping strategies to minimize the frequency and intensity of aversive thoughts

and emotions related to early childhood abuse.

5 Assessment

The patient presented to the interview as well groomed and attentive. Her speech rate

was noticeably slowed and her tone and volume were quiet. The patient was oriented on all

spheres. Mild psychomotor agitation was evident and was consistent with the patient’s

mood that was described as depressed and somewhat anxious. Affect was congruent with

mood. There was no evidence of perceptual distortions or any indication of suicidal

ideation. Thought process, as exhibited by verbal behavior, was slowed but logical and the

patient appeared to be of above average intellect. The patient had adequate insight about

her psychological symptoms.

The patient was administered a semistructured interview (The Anxiety Disorder Interview

Schedule for DSM-IV; Brown, DiNardo, & Barlow, 1994) that revealed coexistent diagnoses

of major depression and generalized anxiety. Her multiaxial diagnosis was as follows:

Axis I: 296.32 Major depressive disorder, recurrent

300.02 Generalized anxiety Disorder

Axis II: Diagnosis deferred

Axis III: 239.9 Breast cancer

959.9 Knee injury/replacement

Axis IV: Employment issues

Axis V: GAF = 60

Prior to therapy, the patient completed several self-report assessment measures:

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) consists of 21 items, each

rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale. There has been strong support for the reliability and validity

of the measure with depressed younger (Nezu, Ronan, Meadows, & McClure, 2000) and older

adults (Stanley, Novy, Bourland, Beck, & Averill, 2001).

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Armento, Hopko / Behavioral Activation 29

The Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item

self-report questionnaire of depressive symptoms that has good psychometric properties (Radloff,

1977) and has been shown to modestly relate to a diagnosis of clinical depression (Myers &

Weissman, 1980).

The Environmental Reward Observation Scale (EROS; Armento & Hopko, 2007) is a 10-item

measure (responded to on a 1- to 4-point Likert-type Scale) that assesses RCPR or the experience

of increased behavior and positive affect as a consequence of rewarding environmental experi-

ences. Good psychometric properties (i.e., internal consistency, test-retest reliability, convergent

validity) have been demonstrated for the measure (Armento & Hopko, 2007).

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990) is a 21-item questionnaire designed to dis-

tinguish cognitive and somatic symptoms of anxiety from those of depression. Good psychome-

tric properties have been demonstrated for the measure among community, medical, and

psychiatric outpatient samples (Morin et al., 1999; Osman, Kopper, Barrios, Osman, & Wade,

1997; Steer, Willman, Kay, & Beck, 1994; Wetherell & Areán, 1997).

The Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI; Frisch, 1994) is a 16-item instrument that evaluates quality

of life across various domains of functioning (e.g., health, relationships, money). Ratings of

importance and satisfaction are made for each domain, with an overall score calculated by aver-

aging satisfaction ratings for all domains assigned nonzero importance ratings. Total scores range

from –6 to +6. The QOLI appears to be a reliable and valid measure of life satisfaction (Frisch,

1999).

The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) is a well-known

survey that assesses health and functional status. The instrument includes eight subscales: phys-

ical functioning (PF), role disability due to physical problems (RP), bodily pain (BP), health per-

ceptions (HP), vitality (V), social functioning (SF), role disability due to emotional problems

(RE), and general mental health (GH).

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, &

Farley, 1988) is a 12-item scale that assesses adequacy of social support from family, friends, and

significant others. The instrument has adequate psychometric properties in clinical and nonclini-

cal samples of adults (Stanley, Beck, & Zebb, 1998; Zimet et al., 1988).

In addition to these self-report measures, the clinician also completed the Hamilton

Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960), a 24-item semistructured interview

designed to measure symptom severity in patients with depression (Hamilton, 1960). The

instrument is the most widely used and accepted outcome measure for evaluating depres-

sion and has become the standard outcome measure in clinical trials (Kobak & Reynolds,

1999).

Pretreatment assessment occurred 1 week prior to beginning the behavioral activation

protocol. The patient’s scores on pretreatment measures were as follows: BDI-II = 25

(moderate depression; Beck et al., 1996); CES-D = 46; EROS = 21; BAI = 15 (moderate

anxiety; Beck & Steer, 1993); QOLI = –3; SF-36, PF = 30, RP = 0, SF = 12.5, HP = 48,

RE = 0, V = 30, GH = 50, BP = 31; MSPSS = 22; and HRSD = 25.

6 Case Conceptualization

The case formulation was based on a behavioral model of depression grounded in func-

tional analytic theorems (Ferster, 1973; Hopko & Lejuez, 2007). Beginning with Skinner

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

30 Clinical Case Studies

(1953), who theorized that depression was associated with an interruption of a repertoire of

healthy behavior that had previously been positively reinforced in the social environment,

a number of researchers have suggested that overall decreases in response-contingent rein-

forcement for nondepressive behavior are a causal factor in eliciting depressive affect

(Ferster, 1973; Hopko et al., 2003b; Lewinsohn, 1974; Martell et al., 2001). A functional

analytic view proposes that a combination of reinforcement for depressed behavior and a

lack of reinforcement or even punishment of more healthy alternative behaviors lead to

depressed affect and a pattern of depressed, unhealthy behavior (Ferster 1973; Hopko et al.,

2003b). In the case of this patient, antecedents to depressive affect were her diagnosis and

treatment of breast cancer as well as her difficulty regaining mobility after knee surgery.

These events had a significant impact on the patient’s overt behaviors, access to environ-

mental reinforcement, self-identity, and anticipated life goals. Previously rewarded behav-

iors such as working at her job and spending time hiking or exercising had become less

enjoyable and sometimes physically impossible. This led to a decrease in positive rein-

forcement (and increased punishment when pain became debilitating) for activities she had

previously found pleasurable, causing her to begin a cycle of avoidance and less healthy

behaviors (e.g., passivity, oversleeping). Although the patient found herself spending less

time being active and taking part in more avoidant, passive, and unhealthy behaviors, she

recognized that this behavioral routine was worsening her negative affect. At the same time,

she was mildly rewarded by these maladaptive behaviors in the context of controlling her

symptoms of pain, as well as generalized anxiety, noting that she could effectively avoid

anxious thoughts through such behaviors as watching television and oversleeping.

Importantly, this patient had previously been a very physically active person, and the inabil-

ity to behave in a manner consistent with this value and accomplish the same goals she had

previously set for herself further worsened her negative affect.

7 Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress

Based on this case conceptualization, the patient was treated using the behavioral acti-

vation manualized protocol for cancer patients (Hopko & Lejuez, 2007). In addition to the

core activation component outlined below, the protocol included psychoeducation about

cancer and its relation to emotional experiences and behavioral changes (during the first

session). In addition, the protocol included three journal assignments designed to increase

exposure and acceptance of issues surrounding cancer (i.e., writing about “being diagnosed

with cancer”, “living with cancer,” and “writing a letter to a friend who had been diagnosed

with cancer”). These exercises were assigned in each of the first three sessions.

The behavioral activation treatment was based on an “acceptance versus change” model

(Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999) in which the patient was presented with the rationale that

some things in life are controllable and changeable, whereas there are other experiences that

we cannot change and thus must be met with acceptance (e.g., being diagnosed with cancer).

The same logic is applied to negative emotional states that are perceived as very difficult to

directly target. Instead, the primary mechanism for improving affect is to target what we have

more power to control and change, namely, overt behavior. Once modified, these changes in

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Armento, Hopko / Behavioral Activation 31

overt behavior bring about different (and more rewarding) environmental consequences that

positively affect mood, energy level, motivation, and thinking patterns. Through this process,

the patient gradually experiences increased response-contingent reinforcement that facilitates

relief from depression and anxiety symptoms.

The behavioral activation intervention was carried out over eight, 1-hr sessions, con-

ducted weekly. The patient had been prescribed 500 mg of Wellbutrin (qd) during treatment

and had been stabilized on this medication for 8 weeks prior to initiating psychotherapy.

Initial sessions included building rapport with the patient, explanation of the treatment

rationale, working toward creating a healthier environment, identifying important life areas

and establishing life goals, beginning to confront cancer through behavioral exposure

accomplished through journal assignment, and beginning to establish measurable and

observable target activities consistent with the patient’s life-goal assessment. During the

first session, the patient was asked to take an exercise home to examine already occurring

daily activities through use of a daily diary. This assignment provided a baseline measure-

ment of the patient’s activities that allowed the patient to become more aware of the qual-

ity and quantity of her activities while also providing a baseline measure for following

progress of treatment. This exercise also provided an opportunity to gather ideas for poten-

tial activities to target. During the second session, focus shifted to identifying the patient’s

values and goals within various life areas including family, social, and intimate relation-

ships, as well as education, employment, hobbies or recreation, volunteer work, physical

and psychological health, and spirituality. An activity hierarchy was developed from this

list during the third session, and 13 activities were identified and rated from easiest to most

difficult for the patient to accomplish. These activities included some new activities (e.g.,

socializing with women from her support group outside of meeting times), some previously

rewarding activities that she was no longer engaging in or wanted to increase the time she

did engage in them (e.g., exercise, time with husband), and activities that were designed to

accomplish long-term goals (e.g., activities leading toward reestablishing a professional

career). Using a master activity log and behavioral checkout to monitor progress, the

patient progressively moved through the hierarchy of activities over sessions from easiest

to most difficult to accomplish. Patient and therapist together discussed what the final goal

duration and frequency would be and this was recorded on the master activity log that was

kept by the therapist (a sample master activity log is presented in Table 1). The patient and

therapist also discussed weekly goal assignments which were recorded on a behavioral

checkout form that the patient took home, completed, and brought back to the next session.

At the beginning of each session, the behavioral checkout was discussed and new goals for

the coming week were set based on the successes or difficulties associated with the previous

week’s goals. As indicated on the master activity log in Table 1, the patient exhibited very

good compliance. At posttreatment, compliance was assessed by calculating the proportion

of behaviors assigned versus those completed. The patient’s compliance score was 94.2%.

Exposure and relaxation exercises were incorporated into the behavioral hierarchy to

work through some of the patient’s generalized anxiety symptoms, particularly targeting

her health-related concerns with regard to her cancer diagnosis. As described earlier, expo-

sure exercises involved journal entries pertaining to experiences of being diagnosed,

treated, and living with cancer culminating with the completion of a written exercise

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

32 Clinical Case Studies

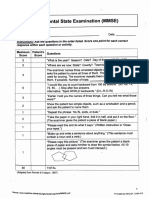

Table 1

Sample of Patient’s Master Activity Log

Ideal Goal Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7a

Goal Goal Goal Goal

Activity No. Time No. Time Do No. Time Do No. Time Do # Time Do

Exercise 7 30 m 3 20 5 3 20 3 3 20 4 3 20 3

Time talking 7 UF 1 UF 3 3 UF 3 1 UF 3

with husband

Activity with 7 UF 3 UF 6 3 UF 5

husband

Support group 5 1h 3 UF 5 3 UF 4 3 UF 3 3 UF 3

Attend church 1 UF 1 UF 1 1 UF 1 1 UF 1

Sitter elderly 5 8h 1 UF 1 6-12h 5

woman

Visit Chatanooga 1/m UF 1 UF 2 UF 1

(family)

Hiking or 2 UF UF 2 1 UF 1 1 UF 1

walking with

friends

Social activity 2 UF UF 2

with women

from SG

Granddaughter 1/m UF 1 UF 1

spend night

Note: UF = Until Finished

designed to help a friend cope with being diagnosed with cancer. Through each of these

journal assignments, the patient was able to approach her thoughts and emotions about her

health and her diagnosis. She became progressively more skilled at articulating her emo-

tional and cognitive experiences and reported that these exercises were cathartic and help-

ful for “moving through” her cancer experiences, coming to a greater level of acceptance

about her diagnosis, and being more comfortable with approaching (rather than avoiding)

difficult memories and stressful experiences in general. Regular exercise was also a stan-

dard assignment incorporated into the patient’s master activity log in an effort to further

develop stress management skills. The patient reported feeling less anxious and less

depressed as she became more committed to a regular exercise routine.

Consistent with this verbal report, the posttreatment assessment revealed notable

decreases in depressive and anxious symptoms as well as improved quality of life and psy-

chosocial functioning. At posttreatment, the patient’s scores on measures were as follows:

BDI-II = 0; CES-D = 0; EROS = 32; BAI = 0; QOLI = 3; SF36, PF = 70, RP = 25, SF =

75, HP = 76, RE = 100, V = 70, GH = 60, BP = 51; MSPSS = 12; HRSD = 2. Patient sat-

isfaction with behavioral activation was assessed with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

(CSQ; Larsen, Attkisson, Hargreaves, & Nguyen, 1979), with data indicating strong patient

satisfaction (CSQ = 29.0/32).

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Armento, Hopko / Behavioral Activation 33

8 Complicating Factors

The most prominent complicating factor for this patient involved unresolved grief sur-

rounding her cancer diagnosis, which effectively was addressed via completion of written

exposure exercises and subsequent therapist–patient verbal exploration. Another compli-

cating factor was the patient’s physical limitations associated with knee surgery approxi-

mately a year prior to therapy. During her treatment, exercise and health activities were

targeted along with coordinated rehabilitation of her knee provided by a physical therapist.

Consequently, the patient had increased mobility, less pain, and increased energy, greatly

contributing to her ability to successfully obtain RCPR.

9 Managed Care Considerations (if any)

Data have supported the utility of behavioral activation strategies among depressed

patients in the context of a community mental health center (Lejuez, Hopko, LePage,

Hopko, & McNeil, 2001), an inpatient psychiatric facility (Hopko, Lejuez, LePage, Hopko,

& McNeil, 2003a), as a treatment within medical care settings for depressed cancer patients

(Hopko et al., 2005, 2008) and in the context of rigorous randomized controlled trials

(Dimidjian et al., 2006; Jacobson et al., 1996). The flexible, uncomplicated, and time-effi-

cient nature of behavioral activation likely makes it a practical intervention within primary

care settings where resources and time may be limited.

10 Follow-Up

Assessment at 3- and 6-month follow-up revealed maintenance of gains in terms of

reduced depression and anxiety symptoms as well as the improved quality of life and psy-

chosocial improvements documented at posttreatment.

At 3 months follow-up, the patient’s scores on all measures were as follows: BDI-II = 0;

CES-D = 3; EROS = 40; BAI = 0; QOLI = 4; SF36, PF = 95, RP = 100, SF = 100, HP =

100, RE = 100, V = 90, GH = 90, BP = 94; MSPSS = 12; and HRSD = 0. Patient satisfac-

tion with treatment actually increased at 3-month follow-up (CSQ = 32/32) perhaps sug-

gesting that patient realization of how behavioral activation positively affects mood and

thought process increases over time.

At 6 months follow-up, the patient’s scores on all measures were as follows: BDI-II = 1;

CES-D = 1; EROS = 37; BAI = 0; QOLI = 4; SF36, PF = 90, RP = 100, SF = 100, HP =

92, RE = 100, V = 70, GH = 85, BP = 94; MSPSS = 14; and HRSD = 0. Patient satisfac-

tion with treatment continued to be strong (CSQ = 32/32).

11 Treatment Implications of the Case

Perhaps the most important implication of this case resides in the effective use of a

behavioral activation protocol to treat a patient presenting with both a major medical

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

34 Clinical Case Studies

problem and coexistent psychiatric problems. Given the prevalence of breast cancer and

the high rate of depression exhibited by women with breast cancer, the initial successes

of behavioral activation interventions administered within medical care settings is excit-

ing because it provides a treatment option for women who historically have been under-

treated for their depression. In addition, this study demonstrates that the uncomplicated,

time-effective, flexible, and ideographic nature of behavioral activation may be adequate

to observe clinically significant patient change across a breadth of outcome variables.

Finally, given the positive treatment outcome and corresponding reductions in anxiety,

which we largely ascribe to increasing approach-oriented behaviors (and reducing avoid-

ance) to facilitate environmental reinforcement, there is some support for a unified model

of emotional disorders. More specifically, it seems plausible that behavioral activation may

effectively treat coexistent depressive and anxiety disorders that are theoretically linked on

the basis of a core problem with avoidance behavior (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004).

12 Recommendations to Clinicians and Students

A significant proportion of patients with depression and anxiety who present to primary

care are misdiagnosed, undiagnosed, and untreated (McQuaid et al., 1999; Schuyler, 2000).

Those who are diagnosed and treated often report only moderate to low quality of care for

depression (Wells, Schoenbaum, Unutzer, Lagomasino, & Rubenstein, 1999). Accordingly,

there is a pressing need for quality improvement with an emphasis on treatment efficacy

and cost-effectiveness for depression treatments within medical care settings. The use of a

behavioral activation protocol may be helpful for clinicians and students looking to imple-

ment a time-efficient treatment that can be individualized to patient’s experiencing signifi-

cant and coexistent Axis I and III diagnoses while also respecting the infrastructure and

operating procedures of medical care settings.

References

American Cancer Society. (2007). Cancer facts and figures for 2007. Available from http://www.cancer.org

Andersen, B. L. (1992). Psychological interventions for cancer patients to enhance the quality of life. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 552-568.

Antoni, M. H., Lehman, J. M., Kilbourn, K. M., Boyers, A. E., Culver, J. L., Alferi, S. M., et al. (2001).

Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances

benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology, 20, 20-32.

Armento, M. E. A. & Hopko, D. R. (2007). The Development and Validation of the Environmental Reward

Observation Scale (EROS). Behavior Therapy, 38, 107-119.

Badger, T., Braden, C. J., Mishel, M. H., & Longman, A. (2004). Depression burden, psychological adjustment, and

quality of life in women with breast cancer: Patterns over time. Research in Nursing and Health, 27, 19-28.

Badger, T., Segrin, C., Dorros, S. M., Meek, P., & Lopez, A. M. (2007). Depression and anxiety in women with

breast cancer and their partners. Nursing Research, 56(1), 44-53.

Baum, A., & Andersen, B. L. (2001). Psychosocial interventions for cancer. Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Beck Anxiety Inventory: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological

Corporation.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Armento, Hopko / Behavioral Activation 35

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological

Corporation, Harcourt Brace.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX:

Psychological Corporation

Brown, T. A., Di Nardo, P., & Barlow, D. H. (1994). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. San

Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Dausch, B. M., Compas, B. E., Beckjord, E., Luecken, L., Anderson-Hanley, C., Sherman, M., et al. (2004).

Rates and correlates of DSM-IV diagnoses in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Journal of

Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 11, 159-169.

Deshields, T., Tibbs, T., Fan, M., & Taylor, M. (2006). Differences In patterns of depression after treatment for

breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 15, 398-406.

Dimidjian, S., Hollon, S., Dobson, K., Schmaling, K., Kohlenberg, B., Addis, M. E., et al. (2006). Randomized

trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of

adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 658-670.

Fawzy, F. I., Fawzy, N. W., & Canada, A. L. (2001). Psychoeducational intervention programs for patients with

cancer. In A. Baum & B. L. Andersen (Eds.), Psychosocial interventions for cancer (pp.235-267).

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ferster, C. B. (1973). A functional analysis of depression. American Psychologist, 28, 857-870.

Frisch, M. B. (1994). Manual and Treatment Guide for the Quality of Life Inventory. Minneapolis, MN:

National Computer Systems.

Frisch, M. B. (1999). Quality of life assessment/intervention and the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI). In

M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment

(2nd ed., pp. 1277-1331). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Golden, W. L., & Gersh, W. D. (1990). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of cancer patients. Journal

of Rational Emotive and Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 8, 41-51.

Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 23, 56-61.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential

approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

Hjerl, K., Anderson, E. W., Keiding, N., Mouridsen, H. T., Mortensen, P. B., & Jorgensen, T. (2003). Depression

as a prognostic for breast cancer mortality. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry,

44, 24-30.

Hollon, S. D. (2001). Behavioral activation treatment for depression: A commentary. Clinical Psychology:

Science and Practice, 8, 271-274.

Hopko, D. R., Bell, J. L, Armento, M. E. A., Hunt, M. K, & Lejuez, C. W. (2005). Behavior therapy for depressed

cancer patients in primary care. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 42, 236-243.

Hopko, D. R., Bell, J. L., Armento, M. E. A., Robertson, S. M. C., Mullane, C., Wolf, N., et al. (2008).

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Depressed Cancer Patients in a Medical Care Setting. Behavior Therapy, 9,

126-136.

Hopko, D. R., & Lejuez, C. W. (2007). A Cancer Patient’s Guide to Overcoming Depression and Anxiety:

Getting Through Treatment and Getting Back to Your Life. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Hopko, D. R., Lejuez, C. W., LePage, J., Hopko, S. D., & McNeil, D. W. (2003a). A brief behavioral activation

treatment for depression: A randomized trial within an inpatient psychiatric hospital. Behavior Modification,

27, 458-469.

Hopko, D. R., Lejuez, C. W., & Ruggiero, K. J., & Eifert, G. H. (2003b). Contemporary behavioral activation

treatments for depression: Procedures, principles, progress. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 699-717.

Jacobson, N. S., Dobson, K. S., Truax, P. A., & Addis, M. E. (1996). A component analysis of cognitive-

behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 295-304.

Kissane, D. W., Grabsch, B., Love, A., Clarke, D. M., Bloch, B., & Smith, G. C. (2004). Psychiatric disorder

in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer: A comparative analysis. Australian and New Zealand

Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 320-326.

Kobak, K. A., & Reynolds, W. M. (1999). Hamilton Depression Inventory. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The Use of

Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment (2nd ed., pp. 935-969). Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

36 Clinical Case Studies

Larsen, D. L., Attkisson, C. C., Hargreaves, W. A., & Nguyen, T. D. (1979). Assessment of client/patient satis-

faction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2, 197-207.

Lejuez, C. W., Hopko, D. R., & Hopko, S. D. (2002). The brief behavioral activation treatment for depression

(BATD): A Comprehensive patient guide. Boston: Pearson Custom.

Lejuez, C. W., Hopko, D. R., LePage, J., Hopko, S. D., & McNeil, D. W. (2001). A brief behavioral activation

treatment for depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 8, 164-175.

Lewinsohn, P. M. (1974). A behavioral approach to depression. In R. M. Friedman and M. M. Katz (Eds). The

psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 157-185). New York: Wiley.

Martell, C. R., Addis, M. E., & Jacobson, N. S. (2001). Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. New

York: Norton.

McGregor, B. A., Antoni, M. H., Boyers, A., Alferi, S. M., Blomberg, B. B., & Carver, C. S. (2004). Cognitive-

behavioral stress management increases benefit finding and immune function among women with early-

stage breast cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56, 1-8.

McQuaid, J. R., Stein, M. B., Laffaye, C., & McCahill, M. E. (1999). Depression in a primary care clinic: The

prevalence and impact of an unrecognized disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 55, 1-10.

Monti, D. A., Mago, R., & Kunkel, E. J. S. (2005). Depression, cognition, and anxiety among postmenopausal

women with breast cancer. Practical Geriatrics, 56, 1353-1355.

Moorey, S., Greer, S., Bliss, J., & Law, M. (1998). A comparison of adjuvant psychological therapy and sup-

portive counseling in patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 7, 218-228.

Morin, C. M., Landreville, P., Colecchi, C., McDonald, K., Stone, J., & Ling, W. (1999). The Beck Anxiety

Inventory: Psychometric properties with older adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 5, 19-29.

Myers, J. K., & Weissman, M. M. (1980). Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect major depression in a

community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137, 1081-1084.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., Houts, P. S., Friedman, S. H., & Faddis, S. (1999). Relevance of problem-solving

therapy to psychosocial oncology. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 16, 5-26.

Nezu, A. M., Ronan, G. F., Meadows, E. A., & McClure, K. S. (2000). Practitioner’s guide to empirically based

measures of depression. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Osman, A., Kopper, B. A., Barrios, F. X., Osman, J. R., & Wade, T. (1997). The Beck Anxiety Inventory:

Reexamination of factor structure and psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 7-14.

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population.

Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401.

Ronson, A., & Razavi, D. (2000). Affective and anxiety disorders in patients with cancer: Optimal management.

In K. J. Palmer (Ed.), Depression associated with medical illness (pp. 113-128). Hong Kong, Peoples

Republic of China: Adis International.

Schuyler, D. (2000). Depression comes in many disguises to the providers of primary care: Recognition and

management. Journal of South Carolina Medical Association, 96, 267-275.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Free Press.

Speca, M., Carlson, L. E., Goodey, E., & Angen, M. (2000). A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial:

The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in

cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 613-622.

Spiegel, D. (1999). Psychotherapeutic intervention with the medically ill. In D. S. Janowky (Ed.),

Psychotherapy: Indications and outcomes (pp. 277-300). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Spiegel, D., & Giese-Davis, J. (2003). Depression and cancer: Mechanisms and disease progression. Biological

Psychiatry, 54, 269-282.

Stanley, M. A., Beck, J. G., & Zebb, B. J. (1998). Psychometric properties of the MSPSS in older adults. Aging

and Mental Health, 2, 186-193.

Stanley, M. A., Novy, D. M., Bourland, S. L., Beck, J. G., & Averill, P. M. (2001). Assessing older adults with

generalized anxiety: A replication and extension. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 221-235.

Steer, R. A., Willman, M., Kay, P. A., & Beck, A. T. (1994). Differentiating elderly medical and psychiatric out-

patients with the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Assessment, 1, 345-351.

Trisjsburg, R. W., van Knippenberg, F. C. E., & Rijpma, S. E. (1992). Effects of psychological treatment on can-

cer patients: A critical review. Psychosomatic Medicine, 54, 489-517.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Armento, Hopko / Behavioral Activation 37

Twillman, R. K., & Manetto, C. (1998). Concurrent psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of

depression and anxiety in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 7, 285-290.

Ware, J. E., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual

framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30, 473-483.

Wells, K. B., Schoenbaum, M., Unutzer, J., Lagomasino, I. T., & Rubenstein, L. V. (1999).Quality of care for

primary care patients with depression in managed care. Archives of Family Medicine, 8, 529-536.

Wetherell, J. L., & Areán, P. A. (1997). Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with older med-

ical patients. Psychological Assessment, 9, 136-144.

Wong-Kim, E. C., & Bloom, J. R. (2005). Depression experienced by young women newly diagnosed with

breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 14, 564-573.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived

Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 17, 37-49.

Maria E. A. Armento, MA, is a graduate student in clinical psychology at the University of Tennessee. Her

research interests involve innovations in behavioral assessment and exploring the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral

treatments for depression.

Derek Hopko, PhD, is an Associate Professor of clinical psychology and Associate Department Head of psy-

chology at the University of Tennessee. His research program focuses on health psychology and emotional dis-

orders, with primary interests in psychosocial treatment outcome research for depressed cancer patients.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Comprehensive Handbook of Clinical Health PsychologyVon EverandComprehensive Handbook of Clinical Health PsychologyBret A BoyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychiatric Diagnosis: Challenges and ProspectsVon EverandPsychiatric Diagnosis: Challenges and ProspectsIhsan M. SalloumBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Counseling Vs Clinical PsychologistDokument2 SeitenCounseling Vs Clinical PsychologistOsvaldo González CartagenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical PsychologistDokument1 SeiteClinical PsychologistlackbarryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arizona Clinical Interview Rating ScaleDokument5 SeitenArizona Clinical Interview Rating ScaleArbnor Kica100% (1)

- PSYCH - PsychosomaticdelasalleDokument58 SeitenPSYCH - Psychosomaticdelasalleapi-3856051100% (1)

- Psychology Talks 2011 - DR Gitanjali (NUH)Dokument31 SeitenPsychology Talks 2011 - DR Gitanjali (NUH)nuspsycheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Youngmee Kim - Gender in Psycho-Oncology (2018, Oxford University Press, USA)Dokument263 SeitenYoungmee Kim - Gender in Psycho-Oncology (2018, Oxford University Press, USA)Dian Oktaria SafitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cigarette Smoking in Patients With Schizophrenia in Turkey Relationships To Psychopatology, Soci-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics PDFDokument9 SeitenCigarette Smoking in Patients With Schizophrenia in Turkey Relationships To Psychopatology, Soci-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics PDFEmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychiatric 3: Suicide (DR Rosales) June 8, 2011Dokument4 SeitenPsychiatric 3: Suicide (DR Rosales) June 8, 2011Von HippoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Competency Assessment 1Dokument19 SeitenProfessional Competency Assessment 1Bruce MannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS)Dokument1 SeiteSecondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS)MilosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Use of Mobile Device Application For Assessing Pain Pattern in Veteran Patients With Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Related HeadachesDokument27 SeitenThe Use of Mobile Device Application For Assessing Pain Pattern in Veteran Patients With Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Related Headachesapi-529388510Noch keine Bewertungen

- Psychologist or School Psychologist or Therapist or CounselorDokument2 SeitenPsychologist or School Psychologist or Therapist or Counselorapi-79222085Noch keine Bewertungen

- Psychological Assessment ReportDokument3 SeitenPsychological Assessment ReportmobeenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1999 Aversion Therapy-BEDokument6 Seiten1999 Aversion Therapy-BEprabhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 - Guidelines For HIV Care and Treatment in Infants and ChildrenDokument136 Seiten4 - Guidelines For HIV Care and Treatment in Infants and Childreniman_kundu2007756100% (1)

- The Psychology of Gender: PSYC-362-DL1 Taught By: Jason Feinberg Welcome!Dokument58 SeitenThe Psychology of Gender: PSYC-362-DL1 Taught By: Jason Feinberg Welcome!uhhhhNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Extended Bio-Psycho-Social Model: A Few Evidences of Its EffectivenessDokument3 SeitenThe Extended Bio-Psycho-Social Model: A Few Evidences of Its EffectivenessHemant KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- SDQDokument3 SeitenSDQSarah AzminNoch keine Bewertungen

- PSC-17 Scoring Instructions PDFDokument1 SeitePSC-17 Scoring Instructions PDFMayang Sukma SatriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluación de Abuso SexualDokument14 SeitenEvaluación de Abuso SexualLaura Sánchez RodríguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 Ways To Control StressDokument2 Seiten8 Ways To Control Stressstcyrjr510Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 3 Biochemistry of The BrainDokument12 SeitenModule 3 Biochemistry of The BrainSakshi Jauhari100% (1)

- Clinical Application of The DSM-5 in Private CounselingDokument15 SeitenClinical Application of The DSM-5 in Private CounselingRoss CameronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mill Shul Bert Williams 2012Dokument25 SeitenMill Shul Bert Williams 2012AdityaTirtakusumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHOQOL-BREF With Scoring Instructions - Updated 01-10-14Dokument12 SeitenWHOQOL-BREF With Scoring Instructions - Updated 01-10-14Sean Cho0% (1)

- Response Set (Psychological Perspective)Dokument15 SeitenResponse Set (Psychological Perspective)MacxieNoch keine Bewertungen

- QLD Drug Price ListDokument1 SeiteQLD Drug Price ListMayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biopsychosocial ModelDokument5 SeitenBiopsychosocial ModelElysium Minds100% (1)

- Perinatal Anxiety Screening ScaleDokument8 SeitenPerinatal Anxiety Screening ScaleAprillia RNoch keine Bewertungen

- H.5.1 Antipsychotics PowerPoint 2016Dokument55 SeitenH.5.1 Antipsychotics PowerPoint 2016Ptrc Lbr LpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Childhood Depression Presentation OutlineDokument7 SeitenChildhood Depression Presentation Outlineapi-290018716Noch keine Bewertungen

- Final ThesisDokument120 SeitenFinal ThesisSingh SoniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- School-Based Intervention Relaxation and Guided Imagery For Students With Asthma and Anxiety DisorderDokument19 SeitenSchool-Based Intervention Relaxation and Guided Imagery For Students With Asthma and Anxiety DisorderWidiastuti PajariniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Helping Men Recover: Addiction, Males, and The Missing PeaceDokument8 SeitenHelping Men Recover: Addiction, Males, and The Missing Peacetadcp100% (1)

- ETZI - 2014 - The Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual M AxisDokument16 SeitenETZI - 2014 - The Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual M AxisLoratadinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Overview of The Interview ProcessDokument6 SeitenAn Overview of The Interview ProcessLaura ZarrateNoch keine Bewertungen

- The EMDR Therapy Butter y Hug Method For Self-Administer Bilateral StimulationDokument8 SeitenThe EMDR Therapy Butter y Hug Method For Self-Administer Bilateral StimulationYulian Dwi Putra FJNoch keine Bewertungen

- CatDokument12 SeitenCatnini345Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tourette Syndrome Research PaperDokument7 SeitenTourette Syndrome Research PaperAtme SmileNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Scale For DeliriumDokument13 SeitenAssessment Scale For DeliriumPutu Agus GrantikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Functionalism: American Psychology Takes HoldDokument17 SeitenFunctionalism: American Psychology Takes HoldTehran DavisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tolman Theory of LearningDokument4 SeitenTolman Theory of LearningBigyan BasaulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourette's SyndromeDokument31 SeitenTourette's SyndromeGhadeer AlomariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)Dokument3 SeitenMini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)Prescilla San PedroNoch keine Bewertungen

- CDI Patient VersionDokument9 SeitenCDI Patient VersionalotfyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Case HistoryDokument5 SeitenClinical Case HistoryMahrukhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andreasen 1989Dokument4 SeitenAndreasen 1989RaquelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Issue Schizophrenia IndiaDokument58 SeitenCultural Issue Schizophrenia IndiaSam InvincibleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dummy ReportDokument29 SeitenDummy ReportnaquiahoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16PF BibDokument10 Seiten16PF BibdocagunsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bariatric Surgery BH Grand RoundsDokument39 SeitenBariatric Surgery BH Grand Roundsapi-440514424Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literature ReviewDokument9 SeitenLiterature ReviewCarlee ChynowethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personality Disorders PDFDokument414 SeitenPersonality Disorders PDFLorina SanduNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV For Dr. Keely KolmesDokument9 SeitenCV For Dr. Keely KolmesdrkkolmesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. Jagdeo Survival ManualDokument16 SeitenDr. Jagdeo Survival ManualAli BabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Competency MappingDokument20 SeitenCompetency MappingJagan Mba0% (1)

- QS: Social Exchange Theory: FoundersDokument2 SeitenQS: Social Exchange Theory: FounderssoulxpressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teenage Health Concerns: How Parents Can Manage Eating Disorders In Teenage ChildrenVon EverandTeenage Health Concerns: How Parents Can Manage Eating Disorders In Teenage ChildrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Gordon - Phoenix - Therapeutic Patterns of Milton H. EricksonDokument203 SeitenDavid Gordon - Phoenix - Therapeutic Patterns of Milton H. EricksonNora Grigoruta100% (9)

- An Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesDokument12 SeitenAn Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 382 Full PDFDokument22 Seiten382 Full PDFAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 555 Full PDFDokument21 Seiten555 Full PDFAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Animalele - Material Terapie ABADokument17 SeitenAnimalele - Material Terapie ABAAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time Limited Psychotherapy PDFDokument52 SeitenTime Limited Psychotherapy PDFlara_2772Noch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokument18 SeitenBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Full PDFDokument21 Seiten3 Full PDFAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic DisorderDokument21 SeitenA Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic Disordermetramor8745Noch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokument18 SeitenBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oppositional Defiant DisorderDokument13 SeitenOppositional Defiant DisorderAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokument18 SeitenBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Don't Kick Me OutDokument14 SeitenDon't Kick Me OutAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive InterventionDokument13 SeitenCognitive InterventionAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Five Therapeutic RelationshipsDokument16 SeitenThe Five Therapeutic RelationshipsAndreea Nicolae100% (2)

- Treating Depression in Prison Nursing HomeDokument21 SeitenTreating Depression in Prison Nursing HomeAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internet-Related Psychopathology Clinical Phenotypes and PerspectivesDokument138 SeitenInternet-Related Psychopathology Clinical Phenotypes and PerspectivesAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsDokument13 SeitenBehavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relation ASD - ADHDDokument16 SeitenRelation ASD - ADHDAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- RADDokument25 SeitenRADAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment and Behavioral Treatment of Selective MutismDokument22 SeitenAssessment and Behavioral Treatment of Selective MutismAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Use of Homework Success For A Child With Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive TypeDokument14 SeitenThe Use of Homework Success For A Child With Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive TypeAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokument18 SeitenBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trating Food Refusal in Adolescent With Asperger's DisorderDokument14 SeitenTrating Food Refusal in Adolescent With Asperger's DisorderAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Therapist As Trauma SurvivorsDokument16 SeitenTherapist As Trauma SurvivorsAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokument18 SeitenBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Attention - ASDDokument13 SeitenThe Role of Attention - ASDAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Attention - ASDDokument13 SeitenThe Role of Attention - ASDAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 Feeding Therapy in A Child With Autistic DisorderDokument12 Seiten9 Feeding Therapy in A Child With Autistic DisorderArden AriandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Immunity and Vaccines As Biology Answers AQA OCR EdexcelDokument3 SeitenImmunity and Vaccines As Biology Answers AQA OCR EdexcelShela HuangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Record Book Design With Services ListDokument3 SeitenMedical Record Book Design With Services ListNANTHA KUMARANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fistula in AnoDokument17 SeitenFistula in Anoapi-216828341Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, KarnatakaDokument7 SeitenRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, KarnatakaWirawanSiregarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter: Targeting The CBM Complex Causes T Cells To Prime Tumours For Immune Checkpoint TherapyDokument24 SeitenLetter: Targeting The CBM Complex Causes T Cells To Prime Tumours For Immune Checkpoint TherapyZUNENoch keine Bewertungen

- Evnt ASCODokument40 SeitenEvnt ASCOChristopher Praveen KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- CytomegalovirusDokument33 SeitenCytomegalovirusAnggi Tridinanti PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENTDokument17 SeitenENTNavya ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spirulina - LatestDokument14 SeitenSpirulina - Latestsenthilswamy_mNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cancer Incidence Report 2020Dokument98 SeitenCancer Incidence Report 2020بسام سالمNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abdominal ExaminationDokument12 SeitenAbdominal ExaminationMukhtar Ahmed100% (1)

- Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDokument7 SeitenDiffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDavid Ithu AgkhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Presentation of Renal Disease: Persistent Urinary AbnormalitiesDokument27 SeitenClinical Presentation of Renal Disease: Persistent Urinary AbnormalitiesradhiinathahirNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Treatment of Cancer With Chinese MedicineDokument6 SeitenThe Treatment of Cancer With Chinese Medicinenepretip100% (2)

- ConjectivaDokument34 SeitenConjectivaIrfan ParakkotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facit F IndiceDokument5 SeitenFacit F IndiceadolforomeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mapeh EssayDokument1 SeiteMapeh EssayJairon BariuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Haidar Abdul-Muhsin M.D., Vipul Patel M.D. (Auth.), Keith Chae Kim (Eds.) - Robotics in General Surgery-Springer-Verlag New York (2014)Dokument496 SeitenHaidar Abdul-Muhsin M.D., Vipul Patel M.D. (Auth.), Keith Chae Kim (Eds.) - Robotics in General Surgery-Springer-Verlag New York (2014)Bogdan Trandafir100% (1)

- Urological RefferalDokument12 SeitenUrological Refferalmichelle octavianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical AbbreviationDokument76 SeitenMedical AbbreviationNajwa AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feature and Sports WritingDokument27 SeitenFeature and Sports WritingJoemar Furigay100% (1)

- History, Examination and Treatment PlaningDokument78 SeitenHistory, Examination and Treatment PlaningShintia HawariNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCP For COLON Cancer PatientDokument4 SeitenNCP For COLON Cancer PatientCarolina Tardecilla100% (1)

- Breast Cancer, Version 3.2020: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in OncologyDokument27 SeitenBreast Cancer, Version 3.2020: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in OncologyHaidzar FNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bacillus Clausii ErcefloraDokument1 SeiteBacillus Clausii ErcefloraCezhille BattadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cures For TinnitusDokument9 SeitenCures For TinnitusBob Skins100% (2)

- Obesity Case StudyDokument4 SeitenObesity Case Studydsaitta108Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nonoperative Proximal Humeus FractureDokument20 SeitenNonoperative Proximal Humeus FractureLuka DamjanovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- CS ShockDokument5 SeitenCS ShockJuliusSerdeñaTrapal0% (5)

- Ipr F300 Re V12.0Dokument6 SeitenIpr F300 Re V12.0gtmlpatelNoch keine Bewertungen