Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Coals of Fire - William Klassen

Hochgeladen von

Carlos MontielCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Coals of Fire - William Klassen

Hochgeladen von

Carlos MontielCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

New Testament Studies

http://journals.cambridge.org/NTS

Additional services for New Testament Studies:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

Coals of Fire: Sign of Repentance or Revenge?

William Klassen

New Testament Studies / Volume 9 / Issue 04 / July 1963, pp 337 - 350

DOI: 10.1017/S0028688500002174, Published online: 05 February 2009

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0028688500002174

How to cite this article:

William Klassen (1963). Coals of Fire: Sign of Repentance or Revenge?. New

Testament Studies, 9, pp 337-350 doi:10.1017/S0028688500002174

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/NTS, IP address: 138.251.14.35 on 04 Apr 2015

New Test. Stud. 9, pp. 337-50-

WILLIAM KLASSEN

GOALS OF FIRE:

SIGN OF REPENTANCE OR

REVENGE?

Anyone who has studied Rom. xii. 20 is aware that it is a notorious crux

interpretum. The strategy of dealing with one's enemy is clear: &AA& £ccv

Treiv^ 6 ^X^P^SCTOU>Tc«3tJllSe ovrov • £ocv Sivy 9, TT6TI3E OCUT6V. Difficult as it is

for the Christian to adapt his life to this admonition anticipations of such a

noble approach are not lacking in ancient literature. The wise man ac-

cording to early Egyptian religion conquers by mastering his emotions. The

prudent way is to avoid a conflict, for the situation may imply complications

which one cannot foresee. It is the silent man who conquers and who is

pre-eminently the successful man according to Egyptian religion.1 In the

strict sense this is not a parallel to Paul's words in Romans, but it is clear

evidence that religion early moved beyond the talion principle in discussing

the question of dealing with one's enemy.

Epictetus also provides an example for a sentiment that comes close to that

of the apostle when he says: ' To fancy that we shall be contemptible in the

sight of other men, if we do not employ every means to hurt the first enemies

we meet, is characteristic of extremely ignoble and thoughtless men. For it

is a common saying among us that the contemptible man is recognized among

other things by his incapacity to do harm; but he is much better recognized

by his incapacity to extend help.' 2

Other instances of this attitude towards enemies have been collected from

philosophical and religious writers.3 There can be no question that in his

position Paul is voicing what others had already voiced before him. In fact

his quotation is taken from the book of Proverbs showing that he bases his

position on the writings of the Hebrew people. The real crux from the stand-

point of the interpreter comes in the following words: TOOTO yctp TTOICOV

av6pctKccs TTupis acopeuaeis £irl TI'IV Ke<paAf]v OCUTOO. Here Paul provides a

motive for love towards enemies and thus the understanding of these words

is crucially important. They have not only theological but also practical rele-

vance for all who are concerned about how a Christian should deal with his

enemies.

1

Henri Frankfort, Ancient Egyptian Religion (New York: Harper Torchbook, 1961), pp. 66-8.

a

Fragments 7, cited from Loeb Classical Library edition.

3

E.g. M. Waldmann, Die Feindesliebe in der antiken Welt und im Christentum (1902), and H. Haas,

Idee und Ideal der Feindesliebe in der ausserchristlichen Welt (1927).

23-z

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

338 WILLIAM KLASSEN

In this difficult passage commentators have at times been satisfied with

'commonly held explanations', but when these are examined they leave

much to be desired.1 An examination of the image 'coals of fire' is necessary

if we are to arrive at the correct understanding of this difficult verse.

THE DERIVATION OF THE IMAGE

The striking vividness of this imagery has led some scholars to begin with the

assumption that the fire is not meant to be taken literally but metaphorically.

Thus Skrinjar notes that the Hebrew word for fire is used sometimes for

Divine punishment, usually vindictive punishment, and even once for

medicinal punishment (Exod. xxiv. 17).2 Since fire in the Bible often

signifies Divine anger, Skrinjar takes the figure to signify the emotion that

wells up in the man whom God medicinally punishes in this way with the

coals signifying the intolerable suffering of self-hatred which results when

hate is requited with love. Likewise Bernhard Weiss says ' Glowing coals is an

image portraying penetrating and enduring pain'. 3

There are a number of interpreters who see the image of fire here as

derived from the smelting furnace. Adam Clarke may be allowed to speak

for them. During the smelting process the ore is put into the furnace and

fire is put both under and over that the metal may be liquefied, and leaving

the scoria and the dross, may fall down pure to the bottom of the furnace.

According to Clarke this is beautifully expressed by an English poet in his

explanation of the passage:

So artists melt the sullen ore of lead,

By heaping coals offireupon its head.

In the kind warmth the metal learns to glow,

And pure from dross the silver runs below.

From this Clarke deduces that 'coals of fire are intended to produce not an

evil but the most beneficial effect'.4 Basically the same approach is taken by

J. E. Yonge when he says that it is generally agreed that the metaphor is

taken from metallurgy even though it becomes necessary to see this metaphor

not in its literal meaning, 'not in the process described, but in the effect

1

Thus Vincent Taylor, The Epistle to the Romans (London, 1955) says: 'This phrase is commonly

explained as meaning " the burning pangs of shame "' (p. 84). Sanday and Headlam also conclude:

'Coals offire,must, therefore, mean, as most commentators since Augustine have said, "the burning

pangs of shame", which may produce remorse and penitence and contrition' (A Critical and Exegetical

Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (New York, 1926), p. 365). Perhaps the most uncommon

interpretation is that of Joseph Rickaby, who feels that this verse ' merely means that you will bring

your enemy to reason more effectively by kindness than by heaping coals of fire upon his head'

{Notes on St Paul: Corinthians, Galatians, Romans (London, 1926), p. 426).

a

See Albinus Skrinjar, 'Carbones ignis congeres super caput eius', Verbum Domini, xvm (1938),

143-5°-

3

Bernhard Weiss, Der Brief an die Rb'mer (Gottingen, 1899), p. 527.

4

Adam Clarke, The Mew Testament (New York, 1857), 11, 142. Albert Sundberg called my

attention to this passage.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

C O A L S O F F I R E : SIGN O F R E P E N T A N C E O R R E V E N G E ? 339

1

produced'. According to John Steele the metaphor refers to the work of a

blacksmith and the expression is used in that trade to refer to the heating of

a broken vessel, thus mending it again. In arriving at this interpretation

Steele draws from an experience he had in China as a missionary. It is

doubtful, however, that Chinese blacksmiths can provide the clue to its

meaning.2

Indeed part of the uneasiness of interpreters stems from the concern that

the metaphor must be evaluated in its totality—that is, in some way 'the

coals of fire' must be brought together with their location, 'on the head'—

otherwise we will not get at the meaning of the metaphor. Sensing this

problem, A. T. Fryer referred to his experience in Palestine where he observed

that the wealthy often shared their embers for culinary purposes with the

poor; they did so by letting the servants carry these burning embers on trays

on their heads.3 According to this Paul would be advocating a beneficent

sharing with our enemy. Now certainly such sharing is already in the text

but Fryer's explanation does not solve the relationship between the act of

kindness and the coals of fire.

Other interpreters have been guided primarily by contextual considera-

tions independent of the clause introduced by ydp in v. 20. Thus Walter

Liithi equates the coals of fire with the fire of God's love and says: 'Heaping

coals of fire upon the head of an enemy is not a sign of weakness of character

on the part of the Christian, but the one act of aggression that love permits

and commands.'4 What has taken place in this interpretation is a spirituali-

zation of the text: a severance between the literal text and the spiritual

meaning derived from the context. Whether the meaning is correct or not is

not now the question. Certainly we will always be somewhat uneasy about an

interpretation which cannot be supported by the literal meaning of words.

If the ' coals of fire' are not literal to what then do they refer? The answers

have been diverse. Augustine took the position that the coals refer to coals of

shame and repentance, a shame evoked by the goodness done to the enemy

and this shame will be the beginning of repentance. Luther quotes Augustine

with approval: 'Blessed Augustine writes: "We must understand this saying

in the following way: we should induce a man who has done us harm to

repent of what he did, and, in this way, we shall do him good. For such

'coals', i.e. benefits, have the power to burn his spirit, i.e., to distress him."

1

'Heaping Coals of Fire on the Head', The Expositor, 3rd ser. n (1885), 158-9.

a

Expository Times, XLIV (1932), 141.

3

Expository Times, xxxvi (1924-5), 478.

4

The Letter to the Romans (Edinburgh, 1961), ad loc, Sanday and Headlam {ibid.) offer an inter-

esting example of how easily modern interpreters move from literal meanings to derived meanings

either on the basis of the context or on the principle that a writer cannot contradict himself. While

they say that dv6pocKcts trup6s 'clearly means "terrible pangs or pains"', they spiritualize this forthwith.

The Moffatt translation also takes this approach when it reads: ' in this way you will make him feel

a burning sense of shame. ' C. H. Dodd {The Epistle to the Romans (London, 1947), pp. 200 f.) is not

sure that it represents the original meaning of Prov. xxv. 22, but it renders Paul's meaning accurately.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

340 WILLIAM KLASSEN

This is what is meant by the words of the Psalter: "The sharp arrows of the

mighty with the coals that lay waste" (Psalm cxx. 4).. . .So then, it is the

benefactions one has performed for his adversaries that are the "coals of

fire".'1 But Ruffenach has observed that to connect coals offireto shame in

a metaphor is utterly foreign to Scripture and to profane literature as well.2

Ruffenach prefers to accept an interpretation-of this passage which he

attributes to Jerome who saw the good deeds as softening the hard heart of

the enemy and kindling love within him. According to his opinion this

interpretation is not far-fetched but rather an allusion to a practice of daily

life which he observed among the Arabs. When the fire in the tent is dead and

cold, they arrange the fuel in a neat pile, and crown it with hot coals on top,

the hot coals being called keph or head.3

There are finally those who see in the coals of fire a threat of severe punish-

ment. It is apparent that from the time of the Sodom and Gomorrah narra-

tive (Gen. xix. 24) onwards ' coals of fire' could be taken in this way and there

are certain Psalms which clearly used it in this way (Psalm xi. 6; cxx. 4;

perhaps also in Psalm cxl. 10, where there is a textual problem).4 Perhaps

Chrysostom is the most famous interpreter who saw in this metaphor a

warning that the punishment would be severe precisely because the enemy

refused to respond to the deeds of love showered upon him.5 Though the

context is meaningless if this interpretation is adopted it does have the ad-

vantage of not spiritualizing any of the elements of the figure of speech. It

does not reduce the figure of speech to a simile8 or spiritualize any parts of

the image here used.7 But if one takes the literal elements of the image

1

Luther: Lectures on Romans, translated and edited by Wilhelm Pauck, The Library of Christian

Classics (Phila. 1961), xv, 355 f. (Unfortunately there is no indication where the Augustine quote

ends and Luther returns.) According to Sanday and Headlam this interpretation goes back to

Origen: ' . . . et ex hoc ignis in eo quidem succendatur, qui eum pro commissi conscientia torqueat

et adurat: et isti erunt carbones ignis, qui super caput eius ex nostro misericordiae et pietatis opere

congregantur' (ibid.).

2

F. Ruffenach, 'Prunas congregabis super caput eius', Verbum Domini, vi (1926), 210-13. Father

Robert Kelly, S.J., kindly assisted me with an English abstract of this essay and the one by Skrinjar.

8

Ruffenach, op. at. p. 213. There is some disagreement among modern writers on the precise

differences among the Church Fathers on this verse.

• H. J. Kraus, Biblischer Kommentar, Altes Testament (Neukirchen, Kreis Moers, i960), xv (Psalmen

II), ad loc, questions the reading 'burning coals'.

5

F. Godet, Commentary on St Paul's Epistle to the Romans (New York, 1883), p. 439, attributes this

position also to Grotius and Hengstenberg. According to Godet these writers see here an encourage-

ment to heap benefits on the head of the evildoer in order to aggravate the punishment with which

God will visit him. Dahood (see below) attributes this view also to Origen. This view finds some

support in II Esdras xvi. 53: ' Let no sinner say that he has not sinned; for God will burn coals of fire

on the head of him who says, " I have not sinned before God... ".'

6

So Charles Gore when he says: 'heap burning shame upon his enemy, like coals offire'(my

italics), St Paul's Epistle to the Romans (London, 1900), n, 106.

7

As several of the above-mentioned interpretations do. One could add: C. K. Barrett, A Com-

mentary on the Epistle to the Romans (London, 1957), where the burning coals 'are the fire of remorse'

or Stifler who speaks of 'coals of red-hot love' (James M. Stifler, The Epistle to the Romans (New

York, 1897), p. 227), while rejecting the 'burning shame' explanation as 'overdrawn'. James

Denney asserts that the 'burning shame' interpretation is 'hardly open to doubt' (Expositor's Greek

New Testament, 11, 694).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

GOALS OF FIRE: SIGN OF REPENTANCE OR REVENGE? 341

seriously then we must inquire more diligently about its meaning. Such an

inquiry must obviously begin with the Old Testament verse Paul is here

quoting.

PROVERBS XXV. 22

Old Testament scholars have been baffled about the meaning of the proverb

which Paul quotes, but the procedure outlined is in accord with other

statements on how to treat an enemy in the book of Proverbs. In recent

times it has been observed that such advice can be found also in Egyptian

literature. Since there is considerable evidence that Egyptian wisdom litera-

ture influenced Proverbs1 it becomes tempting to see in this verse evidence of

borrowing from Egypt; a temptation to which every serious scholar must

yield in this instance. The reason why the identification with Egypt becomes

necessary is that in the verse immediately following we read: 'The north

wind brings forth rain' (Prov. xxv. 23). This verse caused the rabbis diffi-

culties and they emended it because they realized that this was not true in

Palestine.2 Modern scholars like G. Kuhn have made conjectural emenda-

tions on the basis of which he reads: 'The north wind makes a fool out of the

rain' (by dispersing it). 3 A better solution is to see the origin of this proverb

in Egypt, where it is true that the north wind does bring rain.4

Other scholars have noted the difficulty in Prov. xxv. 22 and have suggested

solving it by emendation of that passage. According to the Old Testament

philologist M. J . Dahood,6 Gustave Bickell in 1891 was the first modern

Hebrew scholar to recognize that the Hebrew text of Prov. xxv. 22 taken at

its face value could not be squared either with the immediate context or with

the precepts of charity inculcated in such passages as Prov. xx. 22; xxiv. 17-

18; Sir. xxviii. 1-7. Consequently, Bickell emended the text by deleting the

vexatious phrase 'upon his head' and argued that the coals of fire were the

substance of the hatred ('der Brennstoffdes Hasses') which must be removed

by love for our enemies. By an act of charity a man will put away the burning

coals of hatred. Bickell maintained that this interpretation resulted in a

much nobler sentiment than that which emerged from traditional exegesis.

He tried to justify the deletion of 'upon his head' on the ground that this

prepositional phrase was inserted into the text after the true meaning had

been distorted.6

1

See the article, 'Agypten und die Bibel', RGG3, 1, cols. 117-21, by S. Morenz.

a

Note also the difficulty A. Cohen has with it in Proverbs (Soncino Press, London, 1945), ad loc.

3

G. Kuhn, Beitrage zur Erklarung des salmonisehen Spruchbuches (1931), p . 65, cited in Morenz (see

next note).

4

As observed by Siegfried Morenz, 'Feurige Kohlen auf dem Haupt', Theologische Literaturzeitung,

Lxxvin (1953), cols. 187-92. I owe the impetus for this study to this article to which all subsequent

Morenz references refer.

6

M. J. Dahood, 'Two Pauline Quotations from the Old Testament', Catholic Biblical Quarterly,

xvn

('955). '9-24-

8

Bickell's position is described here on the basis of Dahood's presentation of it who gives as its

source 'Kritische Bearbeitung der Proverbien', W-Z-K-M. v (1891), 283-4.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

342 WILLIAM KLASSEN

Apparently independent of Bickell, T. K. Cheyne adopted a similar

position. His translation reads:

If thine enemy hunger, give him food;

Or if he thirst, give him water to drink;

For hot coals thou earnest away,

And Jehovah will recompense thee.

Cheyne states that the correction has been undertaken to relieve the writer

of the Proverb of the charge of ethical inconsistency. The hot coals of strife

will have been firmly grasped and removed and thus the quarrel will end.

It is true that Prov. xxvi. 20 f., to which T. K. Cheyne refers, seems to

support this understanding of the verse. There we read:

For lack of wood the fire goes out;

And where there is no whisperer, quarrelling ceases.

As charcoal to hot embers and wood to fire,

So is a quarrelsome man for kindling strife.

The main purpose of Dahood's study is to show that both Bickell and

Cheyne were essentially correct in their final result 'but that it is possible to

arrive at a translation similar to the one desired by them without a single

alteration of the M.T., thanks to our expanded knowledge of Hebrew

grammar'. 1

Dahood states that recent studies indicate that the preposition bv in

addition to its usual meanings could also denote 'from'. One could then

translate:' Thus, you will remove coals of fire from his head.' Dahood accepts

the position that 'coals of fire' is a metaphor for 'pains, afflictions' and the

author is then saying that by feeding your hungry enemy and giving him to

drink you will remove a serious affliction from his head. From the assertion

that 'blessings are upon the head of the just' (Prov. x. 6) it is possible to infer

that afflictions are upon the head of the unjust. In Arabic literature 'coals of

the heart' are the inquietudes which devour the soul, and to 'leave coals of

tamarisk in the heart of someone' is to cause him a worry which will perdure

as long as the burning charcoals from this plant.

Furthermore, Dahood seeks to establish the meaning of the participle

nnn which has no certain etymology, but which can be translated 'remove'. 2

This is the translation he prefers which would then give us identically the

same translation given above by Bickell,3 but without textual emendation.

There are those like J. A. Beet who see in the expression 'coals of fire' an

1

Op. cit.

2

According to Gesenius, Hebrew-English Lexicon, this verb is once applied to man (Ps. Hi. 7),

elsewhere always to fire or burning coals (Isa. xxx. 14: 'to take fire from the hearth'; Prov. vi. 27:

'carry fire in his bosom'). Koehler-Baumgartner indicate this root has a different meaning in Ps. lii. 7.

3

Dahood, op. cit. Dahood considers it less likely that 'coals of fire' here designates the passions,

the evil instincts, as is the case in Sirach viii. 10: 'Do not kindle the coals of a sinner, lest you be

burned in his flaming fire.' Skrinjar (op. cit.) also takes the word nrifl here as 'kindling'.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

C O A L S O F F I R E : SIGN O F R E P E N T A N C E O R R E V E N G E ? 343

1

'eastern metaphor for severe and overwhelming punishment'. Skrinjar too

speaks of intolerable suffering, 'the hate of the hater himself'.2 Few go as far

as H. Frankenberg in saying 'to heap fiery coals on someone's head signifies

to take vigorous revenge'.3

The above survey has shown that biblical scholars are uneasy about

accepting the literal meaning of this verse, especially the phrase, 'coals of

fire'. Those who have taken it literally must either emend the Old Testament,

or, as Dahood, reinterpret the meaning of the words; while those who do not

take it literally are far from agreed on its meaning. One group stresses the

pouring of coals of fire upon the head as punishment, others feel that it refers

to removal of potential punishment. It therefore becomes necessary to look

for new light elsewhere if this phrase is to be understood.

EGYPTIAN REPENTANCE RITUAL

An Egyptologist, Siegfried Morenz, has recently called our attention to a

striking parallel which has been known for sixty years but which has received

little attention from commentators. Even Morenz's article has received

little recognition and deserves to be noted here since it offers a solution to

this difficult figure of speech.4

Morenz calls our attention to the demotic narrative of Chaemwese in

which the carrying of coals of fire on the head was a religious ceremony

evidencing to the enemy the genuineness of the bearer's repentance. Now it

should be noted that it is not the coals of fire on the head which force

repentance or in any other way bring about repentance. They are the out-

ward evidence that repentance has taken place. The man in the Egyptian

narrative came back to the party whom he had wronged carrying a staff in

his hand and a tray of burning coals on his head.5 While there is in the

Egyptian narrative an allusion to the moral victory achieved it is clearly not

the kind of victory seen in the destruction of Sodom.6

The custom of carrying coals of fire on the head is not without analogues

1

J . A. Beet, A Commentary on St Paul's Epistle to the Romans (London, 1881), ad loc.

2

Op. cit.

' Die Spruche (Handkommentar zum Alten Testament, Gottingen, 1898), p. 142. Dahood agrees

that this is its meaning in biblical usage (op. cit.).

4

Op. cit.

6

Apparently the first publication of this material is F. L. Griffith, Stories of the High Priests of

Memphis (Oxford, 1900), who did not make the connexion with Proverbs, indeed who thinks of

punishment 'by beating and burning'. Perhaps E. von Dobschiitz is the first to ask the question

whether there may not be a connexion between this and Rom. xii. 20 in a review of Griffith's book

in Theologische Literaturzeitung (1901), col. 282 ff. The text Griffith prints is:' I will cause him to bring

this book hither, a forked stick in his hand and a censer offireupon his head' (p. 32). G. Raeder,

Altdgyptische Erzahlungen und Marchen (Jena, 1927), p. 150, cites it as follows: 'Ich will ihn zwingen,

dass er dieses Buch hierher zuruckbringt, indem ein gabelformiger Stock in seiner Hand und ein

Feuerbachen auf seinem Kopfe ist.'

8

One objection raised to the use of this material is that the Egyptian narrative in its written

form is apparently later than the Proverb. It must be observed, however, that the repentance ritual

may antedate the literary document.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

344 WILLIAM KLASSEN

in the Orient. In addition to the instances given above it is well known that

the humiliated person placed ashes on his head (II Samuel xiii. 19). The

ancient Assyrian laws provided that a prostitute should have bitumen

poured over her head if she veiled it against the law. In none of these cases

however do we have a completely analogous situation. At least in the latter

it would seem that the talion principle is expressed. That member of the

body which has been dishonoured is also to be punished.

In view of this evidence it is difficult to accept Paul Althaus' statement:

'Giite von dem als Feind Behandelten zu erfahren ist fur die feindselige

Gesinnung so unertraglich wie gliihende Kohlen auf dem Haupte: man

muB seine Haltung aufgeben.'1 It is possible to carry burning coals on

the head. Clay dishes have been discovered in Egypt dating prior to our

narrative which were used for the purpose of carrying coals of fire on the

head. A. Alt has indicated that it is the custom in Palestine when a need

arises to carry burning coals in the hands after putting a layer of ashes in

them.2

Having seen that the reference to coals of fire in Proverbs may have its

locus in an Egyptian repentance ritual it is still necessary to ask what

bearing this has on our understanding of the Pauline text. Could Paul have

known about such a usage of coals of fire?3 If not, in what sense did he

understand these verses? To answer this one must look at the Rabbinic

material.

RABBINIC INTERPRETATION OF PROVERBS XXV. 22

The Rabbinic interpretation of the proverb was not uniform. In one

homiletic application of Prov. xxv. 21 f. reference is made to Esther's invitation

of Haman when she fed her enemy but used her table as a snare to capture

her enemy (Esther v and Psalm lxix. 22). R. Jehoschua (c. 90) commented:

'She has learned from her early childhood what the meaning of the words is:

"If your enemy hungers, feed him with bread.'" Paul Billerbeck has ob-

served that the most common interpretation of the enemy is that it refers to

the evil impulse. Rabbi Schimon ben Eleazar (c. 190) draws a parallel

between this verse and a piece of iron which is kept in a fiery furnace. As

long as it is in the fiery furnace it is malleable. So also for the evil impulse:

as long as it is fed with the bread of the Torah it can be controlled. Rabbi

Eliezer (c. 90) refers to the words of the learned as being ' burning coals of

fire' but no application is made to this verse.

There is a late attempt to elucidate this verse which reads: 'With what

shall we compare this? With a baker who stood before the bakeoven; his

enemy comes, he scoops up glowing coals and places them upon his head.

1

Das Neve Testament Deutsch, 2; Der Brief an die Romer, p . 106.

a

The above material is taken from Morenz's article, cols. 189 f.

3

C. H. Dodd (op. cit.) differentiates between the meaning of the expression in Proverbs and

Paul.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

COALS OF F I R E : SIGN OF R E P E N T A N C E OR R E V E N G E ? 345

His friend comes and he takes out warm bread and gives it to him. The

glowing coals and the bread, both come out of the same oven, likewise God

dropped coals of fire on the Sodomites and manna upon the Israelites.'1

PAUL'S LINE OF THOUGHT

Since there is apparently no clue in pre-Christian Judaism to the way in

which Paul used this verse from Proverbs the interpreter of Paul's words

needs to go behind Paul's quotation to find the original meaning of the

expression, 'coals of fire'. Having done that he must make clear that he is

not ascribing that original meaning to Paul, but he is permitted to ask the

question whether the original meaning is in harmony with Paul's main point

in this particular passage. Does Paul's understanding of the way Christians

are to deal with their enemies fit into the original Egyptian repentance ritual

or does it fit better into a revenge motif?

In answering this question the broader New Testament teaching on

dealing with the enemy must be taken into account. Certainly as one looks

at Rom. xii. 14-21 the allusions to the Sermon on the Mount are striking.

C. H. Dodd comments that v. 21 'is an admirable summary of the teaching

of the Sermon on the Mount about what is called "non-resistance", and it

expresses the most creative element in Christian ethics'.2 A study of I Peter

also reveals that there is a consistency in the early Christian literature on this

point. Thus we are dealing here not with a point of view held by one author

but with one that pervades all the Christian literature. Even the Apocalypse

of John has as its dominant symbol a lamb which conquers through suffering

although the imagery is more involved in the apocalyptic material.

This consistency is the more remarkable when seen in contrast to the Old

Testament and the Qumran material. E. J. Sutcliffe has recently demon-

strated that while both the Old Testament and the Qumran literature

emphasize the command that the enemies of God are to be hated, even

though personal enemies are to be repaid with love, the New Testament

nowhere enjoins its readers to hate the wicked. This constitutes a major

difference from the attitude considered proper at Qumran. 3 The sectarians

are urged to 'love those whom (God) has chosen and to hate everyone whom

he has rejected'. They are encouraged to 'hate all the Sons of Darkness each

1

This Rabbinic material is taken from Paul Billerbeck, Kommntar zum Neuen Testament aus

Talmud und Midrasch (2nded.),m,3Oiff. It is also given in Paul Fiebig, 'Jesu Worte iiber die Feindes-

liebe', Theologische Studien und Kritiken, xci (1918), 30-64, who stresses that 'Die Grosse Jesu

besteht.. .darin, dass er mit prinzipieller Klarheit und Scharfe eine schrankenlose, auch iiber die

Schranken der Nationen hinausgehende, also wirkliche Menschenliebe fordert' (p. 39). His

treatment of'coals of fire' concludes that their purpose is to bring about a 'bitter, burning shame'

{ibid.).

a

Op. cit. p. 201.

3

On the Qumran material see E. J. Sutcliffe, 'Hatred at Qumran', Revue de Qumran, 11 (i960),

345-56, especially p. 353. Among the earlier studies S. Bartstra, ' Kolen vuurs Hoopen op iemands

Hoofd', Meuw Theologisch Tijdschnft, xxin (1934), 61-8, stresses the radical break Paul made with

Judaism on this point.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

346 WILLIAM KLASSEN

according to his guilt with the vengeance of God' (iQS i. 10 f.).1 One finds

the exact opposite also: ' Nicht will ich einem das Bose vergelten, mit Gutem

verfolgen will ich den Kraftmenschen, denn bei Gott liegt das Gericht iiber

alles Leben und er vergilt jedem nach seinem Tun' (iQS x. 17 f.). In com-

menting on these words Schubert notes: ' I n contrast to the eschatological

attitude previously described of hating the enemy we have here an attitude

of personal forgiveness towards the man of might. Just as Jesus rejected the

eschatological hatred towards enemies so also he went further in his rejection

of personal hatred of enemies than the sect at En Feschka. I believe it is no

coincidence that Matthew v. 39 is a parallel only to the first part of the

quotation from the Manual of Discipline and not to the second. We can see

from this that the only reason they did not retaliate was because they were

trusting in the judgment of God.' 2

The significant difference between the New Testament and the Qumran

literature would appear however to lie at a different point, viz. the extent to

which the member of the community becomes an agent of God's vengeance.

In addition to the observation that Christians are never enjoined to hate

their enemies they are never seen as agents of divine vengeance. As Kurt

Schubert has noted: 'The motif that is predominant in the battle Scroll is

that of the eschatological disposition to fight against the enemies of God. The

wrath of God will be carried through by the members of the community.'*

Paul too has made reference to the opyr) (Rom. xii. 19). The Christian is

to make room for that. Yet he is not to retreat into quietism but is given a

positive alternative for action in the following verses. The strong adversative

dtAAd which introduces v. 20 indicates that Paul sees this as the positive

alternative open to the Christian in the presence of the enemy. The Christian

does not merely wait in expectation of God's judgement or vengeance nursing

his wounds with thoughts about the eventual punishment which God will

visit upon his enemy. He makes use of the interim to show the enemy that

Christ has made it possible for him to love not only the neighbour but also

the enemy. Paul surely is thinking here of the saying of Jesus: ' Do good to

those who hate you' (Luke vi. 27) and he supports this by citing the Proverb

that the best way to do good to your enemy is to take him into your home

and provide the essentials of life for him thus giving him concrete evidence

that you seek his good in spite of the fact that he seeks your ill.

It would seem that Paul is here concerned primarily with the responsibility

of the Christian just as throughout this chapter he has developed the theme

of the Christian responsibility of love. How does love express itself in the

1

The Qumran material on this theme is competently dealt with also by Victor Hasler, 'Das

Herzstiick der Bergpredigt, Matth. v. 21-48', Theologische £eitschrift, xv (1959), 90-106; Kurt

Schubert, 'Bergpredigt und Texte von En Fescha', Theologische Quartalschrift, cxxxv (1955), 320-37,

and most recently by Krister Stendahl,' Hate, Non-Retaliation and Love', Harvard Theological Review,.

LV (October 1962), 343~55-

2 3

Op. cit. pp. 334 f. Op. cit. p. 336.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

COALS OF F I R E : SIGN OF R E P E N T A N C E OR R E V E N G E ? 347

presence of the enemy? His answer is that it attacks the evil which is incarnate

in the enemy with weapons that nurture human welfare. In so doing they

are overpowering the evil ev TU &ycc0co. Whatever Chrysostom may have

said about the meaning of the image,' coals of fire', his customary perspicacity

can be seen when he says: ' Conquering by doing ill is one of the Devil's laws.

The character of Christ's race is so that it is not in the victory alone, but also

in the way of the victory that the marvel is the greater.. .. For he that hath

ill done him, has not an evil that taketh up its constant abode with him since

he is not the parent of it, but as he received it from others, he made it good

by his patient endurance.' 1

Paul's dominant concern does not seem to be the conversion of the enemy

directly but the method by which Christians overcome evil. The use of

VIK&GO here as elsewhere in the New Testament places the emphasis not on

man's efforts but on the victory achieved by Jesus Christ (John xvi. 33;

Luke xi. 22) and manifested in the life of the church (I John ii. 13 f.). In this

victory judgement certainly has a place, but it is a judgement which is

executed by means of prophetic words and actions which display Christ's

love within the community (I Cor. xiv. 24 f.). To the Romans tutored to

think that power can only be met with greater brute power this teaching

that the goodness of God is meant to lead even the enemy to repentance was

new not in a formal sense but in its underlying dynamic motive. Its novelty

lay in the life of One who had conquered through love.2

Undoubtedly Paul did not know of the existence of the ancient Egyptian

ritual of bearing coals of fire on the head. He surely knew however that

Elijah had once prayed that fire descend from heaven to devour his enemies

(II Kings i. 9-16). He also may have known that the disciples of Jesus once

asked: ' Lord, do you want us to bid fire come down from heaven and con-

sume (the Samaritans?)' (Luke ix. 54) and the response Jesus made on that

occasion. Most deeply, however, Paul had been impressed by the radical

way in which Jesus Christ had overcome evil on the cross and Paul did not

deviate from the early Christian consensus on this matter (cf. I Thess. v. 15).

In the light of this it would seem that the interpreter can apply the original

meaning of this image to Paul's thought without doing violence to it and also

without leaving the impression that Paul knew the original meaning of the

image. Certainly this is not the only place in Paul's writings where the

interpreter must go behind Paul to the meaning of the Old Testament. And

if we evade the dilemma of this verse by introducing the escape hatch of

1

The Homilies ofSt John Chrysostom (Oxford, 1841), pp. 390 f.

2

Sutcliflfe (op. cit. p. 355) calls attention to a passage in Tacitus which may offer evidence for how

widespread the Jewish teaching was that one should hate his enemy: 'Apud ipsos fides obstinata,

misericordia in promptu, sed adversus omnes alios hostile odium' (Hist, v, 5). Paul Althaus has well

observed that the reference to vengeance in this connexion does not mean that Christians are to

seek solace in God's future punishment. 'The apparent impotence in refusal to avenge bears within

it a powerful force: the force of God's earnest love' (op. cit. p. 106).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

348 WILLIAM KLASSEN

'paradox' we should at least know that a repentance ritual existed in

Egypt which made use of 'coals of fire' in a way that is strongly reminiscent

of the Proverbs passage.1 It is not a paradox that we have in this verse but a

scandal—the scandal of the cross.

Whatever one may make of the coals of fire image it is clear that Paul goes

beyond the Stoic method of absorbing evil passively into himself and re-

pressing his feelings towards the enemy who is persecuting him. Epictetus

lauds the ' pleasant strand that is woven into the Cynic's pattern of life; he

must needs be flogged like an ass, and while he is being flogged he must love

(cpiXsiv) the men who flog him, as though he were the father or brother of

them all'. 2 Epictetus also speaks with admiration of Lycurgus the Lace-

daemonian who had been blinded in one eye by one of his fellow-citizens and

then been given the opportunity by the people to take whatever vengeance

he might desire. He refrained from doing this and instead brought him up

and made a good man out of him and presented him in the theatre. When

the Lacedaemonians expressed their astonishment he said, 'This man when

I received him at your hands was insolent and violent; I am returning him

to you a reasonable and public-spirited person'.3 Greek literature contains

other examples of such a noble approach but it lacks a consistent motive for

such an application of the ethic of love and lacks the power which Christians

derive from Christ's victory over evil.

Nor does Paul leave his Roman readers with a choice between two

alternatives as Rabbinic Judaism did. For while some rabbis had great

praise for yielding and compromise, one finds also the opposite: for

example, ' If someone desires to kill you, beat him to the draw and kill him

first'. Or, 'if someone comes to kill you and you can overpower him, do not

hesitate and deliberate, but kill him immediately, as the saying goes,

"Preempt the murderer, before he kills you"'. In the case of an evil done

the rabbis supplied minute regulations for retribution.4

It is significant that Paul did not follow this aspect of Judaism. According

to Paul the Christian is not non-resistant in the face of evil nor is he stoically

passive. He is engaged in a campaign to overcome evil and he retaliates

with those weapons which Christ himself used: deeds of love and kindness.

1

Is it the premature flight into a 'paradoxical' solution which causes Michel to say: ' Viellekht

gab es in Agypten eine Sitte, nach der ein Sunder ein Kohlenbecken auf dem Haupt trug, um dem

Beleidigten genug zu tun' (Der Brief an die Romer (Gottingen, 1955), p. 279, our italics)? The

evidence would seem to justify more confidence than the timid ' vielleicht' and certainly offers little

support for the assumption that its purpose was 'Genugtuung'.

2

Epictetus, Discourses in, xxii, 54ff.(Loeb Classical Library).

8

Epictetus, Fragments 5. Waldmann (op. cit. pp. 54 f.) deals ably with this material and notes the

difference between love for the enemy and disdain for him as it is stoically expressed.

4

Paul Billerbeck, op. cit. 1, 341. The criticisms against Billerbeck's collection are to some extent

justified. However, in our approach we explicitly note that Paul is indebted to Judaism for his view,

but that he could very well have developed a different view also based on Jewish sources. For a

collection of noble Rabbinic material one can refer among others to the excellent article, ' Enemy,

Treatment of an' in The Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, 1903), v, 159-60 by David Philipson and

Fiebig {op. cit.).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

C O A L S O F F I R E : SIGN O F R E P E N T A N C E O R R E V E N G E ? 349

In the performance of these deeds he becomes the instrument that brings the

enemy to encounter Christ, which may eventually lead him to repentance.

Those who see in this passage the two strands, vengeance through judgement

and redemption through repentance (punitive and redemptive punishment)

should note that such a differentiation cannot be found in the Egyptian ritual

and that they presuppose a certain view of Paul's conception of judgement.1

It would seem that Paul is not stating that the Christian's deeds of love will

be a foretaste of final judgement and the coals of fire the enemy will receive

then.2 The coals of fire were evidence in the original ritual that repentance

had taken place and for Paul they probably signified that the enemy had been

made into a friend.3

If this is true then the interpretation so widely accepted by interpreters

that the coals of fire refer to shame, remorse, or punishment lacks all support

in the text. In the Egyptian literature and in Proverbs the 'coals of fire' is a

dynamic symbol of change of mind which takes place as a result of a deed of

love. This text offers a curious case in which the Egyptologist, the Old

Testament scholar and the New Testament student of Paul together can

arrive at a more precise meaning of a difficult verse. It affords also an

interesting illustration of the use of an Old Testament verse by a New Testa-

ment writer without fully penetrating the imagery that lies behind it.

It is not difficult to see why the older interpretation identifying coals of

fire with shame has been so widespread. It is psychologically true to human

experience and the original figure of speech is so obscure that the interpreter

was left with no other alternative.

Having seen the strategy Paul advises the Christian to use in dealing with

an enemy we should not prematurely dismiss this as a product of Paul's

supposed expectation of the Lord's imminent return.4 May it not be more

consistent to see in it the Hebrew-Christian approach to breaking the barriers

that arise among men and which cause some men to call others their enemies?

G. R. Cragg may be correct when he sees in this advice evidence of Paul's

own radical reversal of strategy and the history of the church has shown that

1

In particular one would need to ask to what extent Paul's concept of judgement follows that of

the prophets in which judgement is primarily seen as educative. It would seem that his main point

in Rom. xii deals with the Christian's attitude and actions towards enemies, and thus his concept of

judgement would not bear directly on this issue.

8

Yet there have been attempts by scholars to relate the redemptive and punitive interpretations

of this image. F. J. Leenhardt says: 'The practice, which was probably magical in origin, implied

either the execution of a punitive measure or the repentance of one who undertook voluntarily to

expiate his fault in this way. We may see here then, either the idea already expressed by the sugges-

tion of the "wrath" which executed punishment, or else the idea that the guilty man will repent at

the sight of the kindnesss shown to him by his victim' (The Epistle to the Romans (London, 1961),

ad loc). F. Lang also notes the paradoxical nature of the call to reconciliation in Proverbs and

agrees with Adolf Schlatter that since Paul refers to the wrath (v. 19) the coals offirehave a secondary

reference to the final judgement (see Lang's article on iriJp in Kittel, T.W.N.T. vi, 944).

s

According to Billerbeck (op. cit. p. 302) this interpretation is found in the Targum, hence

would have been most accessible to Paul.

4

So John Knox in Interpreter's Bible, ad loc.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

350 WILLIAM KLASSEN

the method Paul here advocates does have fruitful results in many cases.1

Nevertheless the question Paul forces upon us in Rom. xii is not, ' How can

we transform society?' or 'How can we get results?' but 'What is the good,

acceptable and perfect will of God?' (Rom. xii. 2). By omitting the words

'and the Lord will reward thee' from the quotation from Proverbs Paul

emphasizes that such action is not based on an appeal to recompense but is a

genuine fruit of the Gospel. Wherever such methods do not grow naturally

out of the Gospel they cannot claim the support of Paul or Christ.

We may agree with C. H. Dodd then that we have here an expression of

the most creative element in Christian ethics but disagree with him in

ascribing to it the term 'non-resistance'. Paul says exactly the opposite.

The Christian's task is never to be 'non-resistant' in the face of evil. He

must overcome evil. To say that we have here the most creative element of

Christian ethics is only proper if we recognize that it came to Christianity

via Judaism, had its most pure representation in the life of Jesus and has

been sorely neglected in the history of Christianity. In a world concerned

about 'instant massive retaliation', and pre-emptive annihilation, when

Walter Kaufmann challenges the church with the statement: ' The new note

struck in the New Testament is personal revenge and eternal damnation' 2 it

may be in order to scrutinize the meaning of' coals of fire' again.

1

G. R. Cragg in Interpreter's Bible, ad loc.

2

Walter Kaufmann, Critique of Religion and Philosophy (New York, 1958), p. 180.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 04 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Rich Man and Lazarus, Abraham's Bosom, and The Biblical Penalty Karet (Cut Off) - Ed ChristianDokument11 SeitenThe Rich Man and Lazarus, Abraham's Bosom, and The Biblical Penalty Karet (Cut Off) - Ed ChristianCarlos Augusto VailattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- We Are a Royal Priesthood: The Biblical Story and Our ResponseVon EverandWe Are a Royal Priesthood: The Biblical Story and Our ResponseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Johnson Callum One Under The Father. Patronage, Reconciliation and Salvation in South Asian IslamDokument10 SeitenJohnson Callum One Under The Father. Patronage, Reconciliation and Salvation in South Asian IslamDuane Alexander Miller BoteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reconciliation and Transformation: Reconsidering Christian Theologies of the CrossVon EverandReconciliation and Transformation: Reconsidering Christian Theologies of the CrossNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Apocalypse of St. John-Swete-14Dokument14 SeitenThe Apocalypse of St. John-Swete-14cirojmed100% (1)

- The Image of God in Man. Is Woman Included PDFDokument33 SeitenThe Image of God in Man. Is Woman Included PDFClaraHabibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stephenson - Text of The Jerusalem CreedDokument8 SeitenStephenson - Text of The Jerusalem CreedA TNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jesus RediscoveredDokument282 SeitenJesus RediscoveredTotoDodongGusNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Priority of Love: Christian Charity and Social JusticeVon EverandThe Priority of Love: Christian Charity and Social JusticeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Religious Studies Resources 2010 CatalogDokument32 SeitenReligious Studies Resources 2010 CatalogAve Maria Press100% (1)

- Origen On Prayer by Tye RamboDokument19 SeitenOrigen On Prayer by Tye RamboBesHoxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Holy Trinity (Repaired)Dokument194 SeitenHoly Trinity (Repaired)Anonymous h1oP28wjiyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bible Verses About AngerDokument4 SeitenBible Verses About AngerJonathanKiehlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calvinism for a Secular Age: A Twenty-First-Century Reading of Abraham Kuyper's Stone LecturesVon EverandCalvinism for a Secular Age: A Twenty-First-Century Reading of Abraham Kuyper's Stone LecturesJessica R. JoustraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book of Uncommon PrayerDokument16 SeitenBook of Uncommon Prayerapi-251483947100% (1)

- Much Ado About Something: A Vision of Christian MaturityVon EverandMuch Ado About Something: A Vision of Christian MaturityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anointing and KingdomDokument7 SeitenAnointing and KingdommarlonumitNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gospel of Matthew Jesus As The New MosesDokument3 SeitenThe Gospel of Matthew Jesus As The New MosesRaul Soto100% (1)

- Hardwick - 23458229 Research THEO 530Dokument23 SeitenHardwick - 23458229 Research THEO 530Clay HardwickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gale Researcher Guide for: The Theology of St. Thomas AquinasVon EverandGale Researcher Guide for: The Theology of St. Thomas AquinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sabbath in The Synoptic GospelsDokument15 SeitenThe Sabbath in The Synoptic GospelsRicardo Santos SouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wrestling the Angel: Charles Wesley Struggles with Vital Questions of FaithVon EverandWrestling the Angel: Charles Wesley Struggles with Vital Questions of FaithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Albert Nolan EssayDokument2 SeitenAlbert Nolan EssayAngela Jhoie TolentinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remembering and Resisting: The New Political TheologyVon EverandRemembering and Resisting: The New Political TheologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andani CrucifixionDokument20 SeitenAndani CrucifixionAires Ferreira100% (1)

- A Christian Understanding of Pain and SufferingDokument20 SeitenA Christian Understanding of Pain and SufferingSam VargheseNoch keine Bewertungen

- THERE IS ONE GOD, Ebook by John M. BlandDokument74 SeitenTHERE IS ONE GOD, Ebook by John M. Blandapi-3755336Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hard QuestionsDokument14 SeitenHard QuestionsCon Que PagaremosNoch keine Bewertungen

- French Prophets ChapterDokument44 SeitenFrench Prophets ChapterJ.D. KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gospel of Thomas Commentary On LogioDokument40 SeitenThe Gospel of Thomas Commentary On Logioyahya333100% (1)

- Muhammad The Prophet of IslamDokument72 SeitenMuhammad The Prophet of IslamChristine CareyNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Hee-Sung Keel) Jesus The Bodhisattva Christology From A Buddhist PerspectiveDokument18 Seiten(Hee-Sung Keel) Jesus The Bodhisattva Christology From A Buddhist PerspectiveJaqueline CunhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jesus of Nazarteh and Cosmic RedemptionDokument32 SeitenJesus of Nazarteh and Cosmic RedemptionbuciumeniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life and Character of Gerhard Tersteegen PDFDokument453 SeitenLife and Character of Gerhard Tersteegen PDFWafik IshakNoch keine Bewertungen

- He Will Baptize You With The Holy Spirit and FireDokument81 SeitenHe Will Baptize You With The Holy Spirit and FireIustina și ClaudiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portrayal of John The Baptist in The Gospel According To LukeDokument5 SeitenPortrayal of John The Baptist in The Gospel According To LukeBrince MathewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ben Blackwell, Immortal Glory and The Problem of Death in RM 3,23Dokument24 SeitenBen Blackwell, Immortal Glory and The Problem of Death in RM 3,23robert guimaraesNoch keine Bewertungen

- How God Became Jesus - Part 1 in Review of The Evangelical Response To Ehrman - J. R. Daniel KirkDokument8 SeitenHow God Became Jesus - Part 1 in Review of The Evangelical Response To Ehrman - J. R. Daniel KirkOLEStarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 47 4 pp597 615 - JETSDokument19 Seiten47 4 pp597 615 - JETSSanja BalogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Love and Christian EthicsDokument23 SeitenSelf Love and Christian Ethicsאני גאריNoch keine Bewertungen

- ELOHIM They Are God Sample PDFDokument41 SeitenELOHIM They Are God Sample PDFNightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christadelphian Standards PDFDokument146 SeitenChristadelphian Standards PDFPeter HemingrayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vos ConsciousnessDokument7 SeitenVos Consciousnessmount2011Noch keine Bewertungen

- Niebuhr, Reinhold - Beyond TragedyDokument131 SeitenNiebuhr, Reinhold - Beyond TragedyAntonio GuilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rowan Williams Book ReviewDokument2 SeitenRowan Williams Book ReviewlanescruggsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peter Bouteneff (2008) Beginnings - Ancient Christian Readings of The Biblical Creation Narratives PDFDokument5 SeitenPeter Bouteneff (2008) Beginnings - Ancient Christian Readings of The Biblical Creation Narratives PDFGustavo LagaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Difference Between Orge and ThumosDokument9 SeitenThe Difference Between Orge and ThumosanthoculNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voice of LamentationsDokument4 SeitenVoice of LamentationsWill AndrewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commodity FetishismDokument19 SeitenCommodity FetishismJeet JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- NANCEY MURPHY's BIG MISTAKE (That "Christians Have No Souls") (& Rich Mouw Agrees With Her, Also Wrong)Dokument11 SeitenNANCEY MURPHY's BIG MISTAKE (That "Christians Have No Souls") (& Rich Mouw Agrees With Her, Also Wrong)Van Der Kok100% (1)

- Pelagian Is MDokument21 SeitenPelagian Is MWaya Waya Waya100% (2)

- Costumbres en Común (Reseña) - ThompsonDokument47 SeitenCostumbres en Común (Reseña) - ThompsonCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dead Sea Scrolls in Recent ScholarshipDokument1 SeiteDead Sea Scrolls in Recent ScholarshipCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parálisis de SueñoDokument21 SeitenParálisis de SueñoCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thomas Kuhn and Biblical StudiesDokument15 SeitenThomas Kuhn and Biblical StudiesCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lester L. Grabbe Introduction To Second Temple Judaism - History and Religion of The Jews in The Time of Nehemiah, The Maccabees, Hillel, and JesusDokument167 SeitenLester L. Grabbe Introduction To Second Temple Judaism - History and Religion of The Jews in The Time of Nehemiah, The Maccabees, Hillel, and JesusCosmin Cosorean100% (31)

- Los Valores Del Jade Maya Del Clásico - AndrieuDokument26 SeitenLos Valores Del Jade Maya Del Clásico - AndrieuCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4Q82 Como Texto Editorial.Dokument33 Seiten4Q82 Como Texto Editorial.Carlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scottish Witches and Witchhunters 2013 PDFDokument274 SeitenScottish Witches and Witchhunters 2013 PDFCarlos Montiel50% (2)

- Cazador Delante Del SeñorDokument7 SeitenCazador Delante Del SeñorCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Bible and PtesaursDokument14 SeitenThe Bible and PtesaursCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evangelion Da-Mepharreshe Vol 1 (Curetonian) - Crawford BurkittDokument584 SeitenEvangelion Da-Mepharreshe Vol 1 (Curetonian) - Crawford BurkittFinal777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Orion Newsletter 2019 FinalDokument4 SeitenOrion Newsletter 2019 FinalCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discovering SodomDokument8 SeitenDiscovering SodomCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sebastiano Timpanaro The Genesis of Lachmann S Method PDFDokument133 SeitenSebastiano Timpanaro The Genesis of Lachmann S Method PDFCarlos Montiel100% (2)

- 1 2 ReyesDokument13 Seiten1 2 ReyesCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Doctrina of The TrinityDokument3 SeitenThe Doctrina of The TrinityCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tyndale HouseDokument20 SeitenTyndale HouseCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ladislav Tichý, Co Je To Podobenství?Dokument19 SeitenLadislav Tichý, Co Je To Podobenství?Pavel JartymNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bart Ehrman - The Ortodox Corruption of The ScriptureDokument329 SeitenBart Ehrman - The Ortodox Corruption of The ScriptureMihalache Cosmina100% (23)

- The New Qumran Pesher in AzazelDokument7 SeitenThe New Qumran Pesher in AzazelCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does The Figure of The Son of Man Have A Place in The Eschatological Thinking of The Qumran Community?Dokument12 SeitenDoes The Figure of The Son of Man Have A Place in The Eschatological Thinking of The Qumran Community?Carlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beit Maiersdorf, Room 405: SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2018Dokument2 SeitenBeit Maiersdorf, Room 405: SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2018Carlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- 151 PDFDokument34 Seiten151 PDFCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beit Maiersdorf, Room 405: SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2018Dokument2 SeitenBeit Maiersdorf, Room 405: SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2018Carlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Digital Paleography Approach Towards Writer Identification in The Dead Sea Scrolls - Mladen PopovicDokument10 SeitenA Digital Paleography Approach Towards Writer Identification in The Dead Sea Scrolls - Mladen PopovicCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4Q374 - Louis FletcherDokument18 Seiten4Q374 - Louis FletcherCarlos Montiel100% (1)

- Ancient Jewish Cultural Encounters and A Case Study On Ezekiel - Mladen PopovicDokument11 SeitenAncient Jewish Cultural Encounters and A Case Study On Ezekiel - Mladen PopovicCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Not According To Rule: Women, The Dead Sea Scrolls and QumranDokument14 SeitenNot According To Rule: Women, The Dead Sea Scrolls and QumranCarlos Montiel100% (1)

- RutterGodbeinmheadtous PDFDokument2 SeitenRutterGodbeinmheadtous PDFCarlos MontielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is 666 An Evil Number?Dokument30 SeitenIs 666 An Evil Number?Craig PetersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quiz - Hccs Grade 10 - Google FormsDokument10 SeitenQuiz - Hccs Grade 10 - Google Formsapi-608753287Noch keine Bewertungen

- Coptic Version of N 05 Hornu of TDokument600 SeitenCoptic Version of N 05 Hornu of TPiero MancusoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Israeli Annual Film Guide 2010-2011Dokument68 SeitenIsraeli Annual Film Guide 2010-2011JerCin100% (1)

- Jewish Standard, March 31, 2017Dokument80 SeitenJewish Standard, March 31, 2017New Jersey Jewish StandardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strahlenfolter - Cuttingedge - Org - The 'Star of David' Is A Satanic Hexagram, What Is The Biblical Symbol For IsraelDokument4 SeitenStrahlenfolter - Cuttingedge - Org - The 'Star of David' Is A Satanic Hexagram, What Is The Biblical Symbol For IsraelKarl-Heinz-LietzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Old Testament HistoryDokument760 SeitenOld Testament Historyagnonfabiano100% (2)

- Elus Cohen Weekly Prayers and Invocations of The Elus CohensDokument4 SeitenElus Cohen Weekly Prayers and Invocations of The Elus Cohensroger santos50% (2)

- GodDokument15 SeitenGodKimon FioretosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Deity of Christ-2Dokument3 SeitenThe Deity of Christ-2TheologienNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rod: Will God Spare It?: Chapter 1 - The Accountability AwakeningDokument6 SeitenThe Rod: Will God Spare It?: Chapter 1 - The Accountability AwakeningRBJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transgender Welcome: A Bishop Makes The Case For AffirmationDokument47 SeitenTransgender Welcome: A Bishop Makes The Case For AffirmationCenter for American Progress100% (4)

- Productattachments Files F R Friday Night Siddur Look InsideDokument14 SeitenProductattachments Files F R Friday Night Siddur Look InsideInsiomisAbamonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Odes of SolomonDokument44 SeitenThe Odes of SolomonMichaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Dimension 5759-5760Dokument302 SeitenNew Dimension 5759-5760diederikouwehandNoch keine Bewertungen

- 'Daddy' Analysis by Sylvia PlathDokument6 Seiten'Daddy' Analysis by Sylvia PlathKanika Sharma50% (2)

- Ascended Masters Attunement Manual PDFDokument17 SeitenAscended Masters Attunement Manual PDFSnezana Knez100% (1)

- Tabernacle GuideDokument55 SeitenTabernacle Guidenazim2851100% (2)

- Holman Christian Standard BibleDokument8 SeitenHolman Christian Standard BibleJesus Lives100% (1)

- Statue of Idrimi TranslationDokument3 SeitenStatue of Idrimi TranslationAlex MihailaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bill Skiles - The Impersonal LifeDokument10 SeitenBill Skiles - The Impersonal LifewilliamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bible Reading Plan:: 40 Days On GraceDokument28 SeitenBible Reading Plan:: 40 Days On Gracejuan_rosario_5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gospel2 PDFDokument25 SeitenGospel2 PDFClaudia Sepulveda100% (1)

- Using Indirect WordsDokument3 SeitenUsing Indirect WordsJOLINA AGUAVIVANoch keine Bewertungen

- Crossing The Red SeaDokument4 SeitenCrossing The Red Seacabezadura2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ezekiels TempleDokument19 SeitenEzekiels TempleJohnathon DoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Reading From The Book of The Prophet Jeremiah (7:23-28)Dokument4 SeitenA Reading From The Book of The Prophet Jeremiah (7:23-28)lainelNoch keine Bewertungen

- TawakkulDokument3 SeitenTawakkulshazia100% (1)

- Alasdairs Own Systems and Manuals PDFDokument24 SeitenAlasdairs Own Systems and Manuals PDFSecure High Returns100% (1)

- SUMMARY: So Good They Can't Ignore You (UNOFFICIAL SUMMARY: Lesson from Cal Newport)Von EverandSUMMARY: So Good They Can't Ignore You (UNOFFICIAL SUMMARY: Lesson from Cal Newport)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (14)

- Summary of Supercommunicators by Charles Duhigg: How to Unlock the Secret Language of ConnectionVon EverandSummary of Supercommunicators by Charles Duhigg: How to Unlock the Secret Language of ConnectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Million Dollar Weekend by Noah Kagan and Tahl Raz: The Surprisingly Simple Way to Launch a 7-Figure Business in 48 HoursVon EverandSummary of Million Dollar Weekend by Noah Kagan and Tahl Raz: The Surprisingly Simple Way to Launch a 7-Figure Business in 48 HoursNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workbook & Summary of Becoming Supernatural How Common People Are Doing the Uncommon by Joe Dispenza: WorkbooksVon EverandWorkbook & Summary of Becoming Supernatural How Common People Are Doing the Uncommon by Joe Dispenza: WorkbooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary and Analysis of The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan HouselVon EverandSummary and Analysis of The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan HouselBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (11)

- Summary of The Galveston Diet by Mary Claire Haver MD: The Doctor-Developed, Patient-Proven Plan to Burn Fat and Tame Your Hormonal SymptomsVon EverandSummary of The Galveston Diet by Mary Claire Haver MD: The Doctor-Developed, Patient-Proven Plan to Burn Fat and Tame Your Hormonal SymptomsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Atomic Habits by James ClearVon EverandSummary of Atomic Habits by James ClearBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (169)

- Summary of When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times by Pema ChödrönVon EverandSummary of When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times by Pema ChödrönBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (22)

- Summary of Some People Need Killing by Patricia Evangelista:A Memoir of Murder in My CountryVon EverandSummary of Some People Need Killing by Patricia Evangelista:A Memoir of Murder in My CountryNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Talented Mr Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideVon EverandThe Talented Mr Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Rich AF by Vivian Tu: The Winning Money Mindset That Will Change Your LifeVon EverandSummary of Rich AF by Vivian Tu: The Winning Money Mindset That Will Change Your LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Miracle Morning Millionaires: What the Wealthy Do Before 8AM That Will Make You Rich by Hal Elrod and David OsbornVon EverandSummary of Miracle Morning Millionaires: What the Wealthy Do Before 8AM That Will Make You Rich by Hal Elrod and David OsbornBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (201)

- Summary of The Coming Wave By Mustafa Suleyman: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-first Century's Greatest DilemmaVon EverandSummary of The Coming Wave By Mustafa Suleyman: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-first Century's Greatest DilemmaBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- Summary of Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action by Simon SinekVon EverandSummary of Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action by Simon SinekBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- Summary of Can’t Hurt Me by David Goggins: Can’t Hurt Me Book Analysis by Peter CuomoVon EverandSummary of Can’t Hurt Me by David Goggins: Can’t Hurt Me Book Analysis by Peter CuomoBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Summary of Poor Charlie’s Almanack by Charles T. Munger and Peter D. Kaufman: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. MungerVon EverandSummary of Poor Charlie’s Almanack by Charles T. Munger and Peter D. Kaufman: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. MungerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Feel-Good Productivity by Ali Abdaal: How to Do More of What Matters to YouVon EverandSummary of Feel-Good Productivity by Ali Abdaal: How to Do More of What Matters to YouBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- PMP Exam Prep: Master the Latest Techniques and Trends with this In-depth Project Management Professional Guide: Study Guide | Real-life PMP Questions and Detailed Explanation | 200+ Questions and AnswersVon EverandPMP Exam Prep: Master the Latest Techniques and Trends with this In-depth Project Management Professional Guide: Study Guide | Real-life PMP Questions and Detailed Explanation | 200+ Questions and AnswersBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Summary of The Hunger Habit by Judson Brewer: Why We Eat When We're Not Hungry and How to StopVon EverandSummary of The Hunger Habit by Judson Brewer: Why We Eat When We're Not Hungry and How to StopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Eat to Beat Disease by Dr. William LiVon EverandSummary of Eat to Beat Disease by Dr. William LiBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (52)

- GMAT Prep 2024/2025 For Dummies with Online Practice (GMAT Focus Edition)Von EverandGMAT Prep 2024/2025 For Dummies with Online Practice (GMAT Focus Edition)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of How to Know a Person By David Brooks: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply SeenVon EverandSummary of How to Know a Person By David Brooks: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply SeenBewertung: 2.5 von 5 Sternen2.5/5 (3)

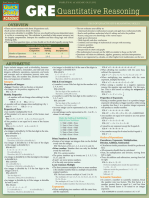

- GRE - Quantitative Reasoning: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideVon EverandGRE - Quantitative Reasoning: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOEFL Writing: Important Tips & High Scoring Sample Answers! (Written By A TOEFL Teacher)Von EverandTOEFL Writing: Important Tips & High Scoring Sample Answers! (Written By A TOEFL Teacher)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (5)

- CUNY Proficiency Examination (CPE): Passbooks Study GuideVon EverandCUNY Proficiency Examination (CPE): Passbooks Study GuideNoch keine Bewertungen