Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Publisher Version (Open Access)

Hochgeladen von

Inês DamascenoCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Publisher Version (Open Access)

Hochgeladen von

Inês DamascenoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

13 Communicating in hospital emergency departments

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, JEANNETTE

McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN – University of Technology and

Macquarie University, Sydney

Abstract

Ineffective communication has been identified as the major cause of critical incidents in public hospitals in

Australia. Critical incidents are adverse events leading to avoidable patient harm. This article discusses

a study that focused on spoken interactions between clinicians and patients in the emergency department

of a large, public teaching hospital in New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of the study was to

identify successful and unsuccessful communication encounters. It combined two complementary modes of

analysis: qualitative ethnographic analysis of the social practices of emergency department healthcare and

discourse analysis of the talk between clinicians and patients. This allowed the researchers to analyse how

talk is socially organised around healthcare practices and how language and other factors impact on the

effectiveness of communication.

The complex, high stress, unpredictable and dynamic work of emergency departments constructs

particular challenges for effective communication. The article analyses patient–clinician interactions within

the organisational and professional practices of the emergency department and highlights some systemic and

communication issues. It concludes with some implications for the professional development of clinicians

and an outline of ongoing research in emergency departments.

Introduction understand diagnosis and treatment, preventable

Effective communication and interpersonal morbidity and mortality, dissatisfaction with care

skills have long been recognised as fundamental and lower quality care in general. These difficulties

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

to the delivery of quality healthcare. However, are perceived to be due, to a large extent, to the

there is mounting evidence that the pressures numbers of practitioners and patients who are not

of communication in high-stress work areas proficient in English (Flores et al 2002). Currently,

such as hospital emergency departments present a considerable number of the health professionals

particular challenges for the delivery of quality in New South Wales hospitals are from language

care. A report on incident management in the backgrounds other than English, and the hospital

New South Wales healthcare system (NSW Health in this study had a total of 25% overseas-trained

2005) cites poor and inadequate communication doctors who had English as a second language.

between clinicians and patients as the main cause However, the study has shown a significant number

of critical incidents. Communication in emergency of clinician–patient communication difficulties and

departments is particularly complex, as clinicians breakdowns are between people who believe they

are now increasingly expected to work in teams to are communicating satisfactorily in English.

treat culturally diverse patients who present with Seminal cross-cultural communication research

multiple symptoms and problems. by Gumperz (1982) and Roberts (2000) has

Inadequate communication is also the demonstrated that serious communication

basis for many patient complaints about the problems can occur where there is no evident

healthcare system (Taylor, Wolfe and Cameron language barrier, and where it is assumed

2002; NHMRC 2004; Health Care Complaints that there is a shared language. For example,

Commission 2005). In their literature review, misunderstandings and communication

Flores et al (2002) demonstrate how failure to breakdowns can occur because of different cultural

recognise the importance of language and culture assumptions about how to structure information

can result in a range of health-related issues, or an argument in conversation, how to signal

including obtaining informed consent, failure to connections and logic, or how to indicate the

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

14 significance of what is being said in terms of overall • identify ways in which clinicians can enhance

meaning and attitude. Different ways of speaking, their communicative practices to improve the

such as tone of voice and intonation patterns, can quality of the patient journey through the

result in inaccurate inferences being drawn about emergency department.

knowledge, attitude or behaviour (Gumperz, Jupp

and Roberts 1991). The project was cross-disciplinary and involved

For a number of decades now, studies of academics in applied linguistics and nursing

communication between doctors and patients from the University of Technology, Sydney, and

have been carried out using either linguistic or Macquarie University, language educators from the

organisational approaches (Wodak 2006). Early New South Wales Adult Migrant English Service

work by Cicourel (1981, 1985), using a number and healthcare professionals from the Area Health

of case histories, showed the advantage of a Service. The research focused on communication

conversation-analytical approach. Other studies between clinicians and patients who were deemed

have focused on healthcare communication in to be able to communicate effectively in English.

general (Sarangi and Roberts 1999; Candlin 2000; The patients were from language backgrounds

Coiera et al 2002; Cordella 2004; Iedema 2005, other than English and English-speaking

2006; Wodak 2006; Sarangi in press). However, backgrounds, but patients who needed interpreters

to date, there has been no research that examines were not included.

the dynamic complexity of interactions unfolding We believe this study to be unique in that, for

in real time in high-risk environments such as the first time, patients were observed and recorded

emergency departments. from the moment they entered the hospital

Healthcare contexts are now of increasing emergency department (triage) to the moment

interest as social organisations because of the a decision about further hospital treatment or

technologically more complex medicalised release from the emergency department was

practices of modern healthcare and the interplay made. The study situated patient experiences and

of professionals in changing organisations (Iedema communication exchanges within professional

2007). There have been a significant number of and institutional practices (Gumperz 1982; Sarangi

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

recent complaints from patients in relation to and Roberts 1999; Iedema 2005; Kemmis in

their experiences in emergency departments in press) of the emergency department, and related

New South Wales, many involving inadequate the interactions between patients and clinicians

communication. Practitioners are also expressing to the broader, systemic exigencies and the roles

dissatisfaction (Joseph 2007) and professional and discourse practices of healthcare professionals,

disquiet (Bragg-Kingsford 2007). Dr Sally managers and policy-makers. The research thus

McCarthy,Vice President of the Australasian contributes to discourse knowledge in the context

College for Emergency Medicine and Director of critical healthcare services.

of the Prince of Wales Emergency Department, The article begins by introducing the hospital

cites lack of funding, inadequate staffing and over- in terms of general demographics, followed by

dependence on locums for the difficulties faced in an outline of the research methods. It presents

emergency departments (Wallace 2007). some examples of spoken data and discusses some

This article outlines findings of a pilot study that major findings. It concludes with implications for

took place in the emergency department of a large the professional development of clinicians and a

teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia. The main description of ongoing research in a further four

aims of the project were to: hospitals.

• describe, map and analyse the communication The study

encounters that occurred between clinicians and The research context

patients in the emergency department in order

The hospital involved in the pilot study has one

to identify the features of both successful and

of the busiest emergency departments in New

unsuccessful encounters

South Wales, dealing with approximately 46 000

patients per year, with an adult admission rate from

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

15 the emergency department of 35% to 40%. The • Discourse data collection

emergency department is the trauma centre for a Interactions between patients and clinicians in

large Sydney catchment area with approximately the emergency department were audio-recorded.

1500 trauma presentations annually. A significant Field notes were also taken during these

focus for the staff and the hospital is on the interactions to record non-verbal and other

efficiency and timeliness of the patient journey relevant information.

through the emergency department. Using the

Australasian triage scale from 1 (most urgent) to 5 • Data analysis

(least urgent), triage aims to ensure that all patients Transcriptions of the patient–practitioner

are treated in the order of their clinical urgency interactions were analysed for lexical,

and that treatment is timely. It also allows for the grammatical and discourse features.

allocation of patients to the most appropriate

assessment and treatment area. The triage nurse is The combination of methods made it possible

the first person to see a new patient and allocates to analyse the relationship between the contextual

an appropriate code following assessment. This features of the emergency department and the

study was primarily concerned with patients in nature of the interactions between patients and

categories 3, 4 and 5, with those in categories 1 clinicians. The purpose of the discourse analysis was

and 2 considered too critical to be recorded. to reveal patterns in discourse that are not normally

accessible to the interactants engaged in the

Research methods discourse. Discourse analysis involved annotating

Drawing on socially oriented functional approaches the transcripts in terms of patterns of meaning

to discourse and language description, the overall (semantics), wording (grammar and vocabulary)

frame for analysis used the theoretical perspectives and sounding (phonology), while at the same time

of critical discourse analysis (Fairclough 1995), taking into account the context in which the

sociolinguistics (Gumperz 1982; Tannen 1984) discourse had unfolded.

and systemic functional linguistics (Halliday 1995;

Halliday and Matthiessen 2004). In addition, the Research findings and discussion

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

study used qualitative ethnographic methods The study provided the researchers with initial data

(Gumperz and Hymes 1972; Creswell 1998; on how organisational and clinician practices and

Silverman 2001), including both observation of the roles impact on patient experiences in emergency

emergency department context and interviews with departments. The study revealed a number of

key personnel. The phases of the research were: issues that indicate potential communication

difficulties between patients and clinicians. These

• Ethnographic data collection findings reflect broader institutional, healthcare and

Participant observation in the field included practitioner practices and discourses, and provide

observations and impromptu interactions insights into how experiences for patients are

with clinicians in order to clarify meanings of affected by unseen or unfamiliar ways of doing,

observed practices. Semi-structured interviews being and talking in emergency care.

were conducted with key informants prior to

and following fieldwork. These included senior Patient as outsider

and junior doctors and nurses, administrative Patients are not familiar with the emergency

staff, ambulance officers and allied clinicians department system and do not understand how

who were selected for their knowledge of it works. A key overall finding is that at no stage

the context. Patient emergency department do patients appear to really know what is going

healthcare records were reviewed to ascertain on around them, or to them, while they are in

clinical information that situated the patient the emergency department. The way the hospital

journey, and analysis was undertaken of policies system works is rarely explained to them. Hospital

and procedures that affected communication in staff recognise that the stated priority is to provide

the emergency department. clear information to patients but it is not easy to

do this because of time and clinical pressures, as

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

16 well as the medical and/or mental condition of one patient said, ‘When they say time [they will

the patient. The patient remains an outsider to the be away], I think it’s a figure of speech for them’.

insitutionalised language and patterns of behaviour Another articulated a similar idea when the

that are practised by emergency department doctor was called away from the patient’s bedside:

staff. This outsider status can result in anxiety, ‘Meanwhile the doctor’s gone to lunch.’

experiential incomprehension and/or interpersonal Consultations between patients and doctors

alienation on the part of the patient. The following were often interrupted, sometimes only for a few

exchange between a young female patient and a seconds. However, occasionally doctors would be

nurse illustrates the patient’s lack of familiarity with called away after answering a message on their

hospital practices, language and procedures: beepers. The following exchange between an elderly

male patient and a male doctor occurred only a

Extract 1 minute or two after the consultation had started.

Nurse: Can you do a urine sample while you’re

in the bathroom? I’ll get you a jar. Extract 2

Patient: [to researchers] Did you guys get what Doctor: I’ve been caught up in something else.

she said ’cos I didn’t? Patient: Yes?

Doctor: I’ll be with you though …

In this extract the term urine sample, as well as

Patient: That’s all right.

the routine procedure of collecting a sample to be

sent for testing, may be new to the patient. Soon Doctor: … in about 5 to 10 minutes.

after, the patient commented that ‘everyone tells Patient: Yeah, righto.

you a different thing’ after being told she was being

admitted to the hospital for follow-up procedures. The doctor returned half an hour later. During

Her comment demonstrates confusion regarding the subsequent consultation, the same patient was

the interactions she has been involved in. interrupted a number of times when the doctor

was called out to attend to another patient, a

Different understandings of time regular occurrence for senior doctors.

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

Patients and doctors have different understandings These examples highlight that the clinicians

of the role that the passage of time plays within and patients in the recorded consultations had

the institutional context of emergency care; for no real control over their own time and the time

example, how long it takes to analyse blood taken for medical analyses. The observations

samples, to read an X-ray or the time it takes showed that clinicians and patients in the

for the doctor to see another patient. As a emergency department existed in competing

consequence, language references around absences timeframes. While doctors moved quickly,

and waiting times are not mutually understood. frequently interrupting consultations to attend

Time plays a central role in the way the to other emergencies, as required by the exigent

emergency department works, both as a resource nature of the emergency department, patients

and as a phenomenon experienced by patients and had little choice but to wait. They were obliged

healthcare practitioners. Elapsed time (waiting) to wait in the waiting room, to wait on test

can have a significant impact on the overall patient results, information and diagnosis, and to wait

experience. Recordings of consultations and on disposition and bed placement, with little

observations revealed that references to time, by explanation as to why this was happening or when

doctors in particular, ranged from the abstract (‘I things would occur. Recorded comments by

won’t be long’) to the numerically specific (‘I’ll be patients showed how the potential discord resulting

back in ten minutes’), although specific timeframes from different perceptions of time could impact

were often found to be unrealistic. Often patients negatively on their overall experiences. At a system

did not have a have clear understanding of how level, the speed of a patient journey through the

long a procedure would take, or how long an emergency department is a stated priority but

absence would be. Sometimes the patients quickly cannot always be achieved, as this Nursing Unit

recognised the elasticity of time; for example, Manager explains:

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

17 Extract 3

a feature that was also revealed in other recorded

[My role is] primarily being patient flow … consultations. The dominance of the doctor script

because obviously flow is very important … So reflects the medical and institutional priorities of

it’s very important to try and, you know, identify the emergency department, and also reflects normal

where there’s potential for bottlenecks and fast- practice. The biomedical imperative of finding out

tracking patients. what is wrong with the patient, in the quickest

possible way, is paramount.

Mismatches between communicative aims of

However, during this consultation, other

patient and practitioner

concerns of the patient were overlooked. The

There is frequently a mismatch between what doctor’s first turn is a question that focuses

patients or their families want to say and what on eating and drinking behaviour (‘Have you been

practitioners want to know. In the following extract eating and drinking sort of reasonably normally?’).

the patient was from a language background other This focus also provides the (repeated) question

than English. It shows the divergent trajectories at the end of this extract (‘Sure but you’ve been

between one inexperienced doctor’s line of keeping up your fluids and drinking …’).

questioning and a family member’s desire to The family member is helping the patient weave

foreground other information. in experiences that focus on the significant

family event of a ‘recent death in the family’.

Extract 4 The biomedical language sits alongside the more

Doctor: Have you been eating and drinking sort psychosocially oriented language, but it is only

of reasonably normally? the former that the doctor hears. Further findings

also demonstrated that doctors frequently did not

Patient: I drink but I haven’t been eating …

pick up on patient concerns when they were not

Family: She hasn’t been eating well because she’s explicitly related to pain, symptoms or the doctor

just had a recent death in the family … script. Nor did doctors ask patients what they

thought about their own health problems, what

Doctor: OK … they thought was wrong with them or what they

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

were worried about.

Family: … A couple of days ago …

Patients asked very few questions in the recorded

Doctor: OK … consultations and patients were not often given

the opportunity to deviate from the question–

Family: … Which is her grandmamma … answer structure. In each of the recorded pilot

study consultations, the doctors made nearly all

Doctor: OK.

the initiating moves, mostly through questions.

Family: So she’s been spending a lot of time at In one consultation, which lasted one and a half

her mother’s house and, no, she hasn’t hours, the doctors asked 145 questions but not

been eating well, obviously distressed one question was asked by the patient. There were

because of that. also significant variations in the kinds of questions

asked, information given and explanations by

Doctor: OK. Sure but you’ve been keeping up different practitioners.

your fluids and drinking and …?

The importance of how diagnoses are delivered

During the consultation phase of this patient’s The delivery of a diagnosis is a key moment

emergency department journey, two trainee of confusion in consultations, and patients do

doctors and a senior doctor interviewed her. not always receive timely, clear or appropriate

The two trainee doctors were practising their diagnoses. Emergency department practitioners see

history-taking techniques, which is normal practice patients as entering with symptoms, behaviours

in emergency departments, particularly in a and pains, as opposed to coming with a particular

teaching hospital. This brief exchange reveals the illness, condition or disease. Their job is to find out

dominance of the doctor script in the consultation, what is wrong with the patient and work out the

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

18 most effective follow-up treatment. Thus, diagnoses and interpersonal distance are not quite right in

for all but very minor ailments are usually given to this situation. He picks up on the patient’s use

patients after a considerable number of activities of the bad-news phrase earlier in the day when

have occurred. These include at least three the patient told the doctor to ‘give me the bad

consultations between different clinicians and the news’. This may have been chosen as a deliberate

patient, one or more physical examinations, tests strategy for establishing rapport with the patient by

such as blood tests, and exploratory procedures constructing some informality and/or familiarity.

such as X-rays. They also include discussions Looking beyond the short diagnosis delivery

between junior and senior doctors, between junior extract to the larger context of professional

and senior doctors and a consultant, and possibly practice, diagnoses are increasingly evidence-based

between hospital doctors and the patient’s general and institutional in nature; that is, they are signed

practitioner. off by others and systematised as ‘doctors and

How diagnoses are delivered constitutes a key nurses will invariably refer to test results carried

communicative event in the patient’s journey out by laboratory technicians when delivering a

through the emergency department. It is what diagnosis’ (Sarangi and Roberts 1999: 24). The

the patient has been waiting for, often very doctor in Extract 5, who was required to consult

anxiously, and it is what the doctor assigned to the with other doctors and wait on the results of tests

patient has been working towards. The following before he could make a final diagnosis, was unable

extract is one example of how a junior doctor, to provide this information to his patient until

from a language background other than English, the end of the shift. This example also illustrates

delivered a diagnosis to an elderly male patient. how the institutional practice of shiftwork in the

The consultations leading up to this diagnosis had emergency department impacts on communication.

continued for many hours while lengthy blood Further, the exchange highlights the doctor’s

tests and X-rays were carried out. The doctor had inexperience in being quite specific about the

been extremely busy all day with this patient and patient’s condition. This contrasts with more typical

others, yet he wanted to finalise the consultation, diagnostic discourse where ‘one searches in vain for

to be the one to deliver the diagnosis before he simple instances of decision-making. Indeed detailed

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

completed his shift. attention to talking-acting throughout the modern

clinic shows how relatively invisible are occasions

Extract 5 of decision-making per se’ (Atkinson 1999: 95).

Doctor: I give you good news or bad news?

Training implications

Patient: Alright.

The analyses of the interactions recorded in the

Doctor: Which one? emergency department will form the basis of

professional development frameworks for overseas-

Patient: Bad one first. educated doctors and nurses in Australia. These will

focus on healthcare and language training.

Doctor: Bad one first. OK. We did a scan and we

found some clots. Multiple. Several clots Healthcare training

in the chest. Right, that’s the bad news.

Health professional training will include

The good news, we found out why you

information on how patients experience their time

have clots. It’s not from the heart. The

in emergency departments and how systemic and

heart’s not going to fail.

institutional practices and communication strategies

Patient: OK. may be accounted for and acted upon in the future.

Cross-cultural training for trainee doctors will

In one reading of the exchange the doctor’s focus on history-taking, interviewing and diagnosis

language is somewhat inappropriate, without delivery. The metaphor of the production line is

the level of sensitivity required to convey such a useful one through which trainers can explore

critical news to an elderly patient. It could be that how emergency department clinicians might better

he realises that the normal biomedical language explain and reassure patients about:

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

19 • the time that tests will take • Are patients understanding the terminology

of the hospital?

• the length of time patients may be in the

emergency department • Are patients following what is happening

to them?

• the repetitive absences of clinicians from the

consultation process • Are patients informed enough about the

processes in the emergency department?

• the rotation of clinicians.

• How is the culture of the emergency

More creatively, training could explore ways in department affecting the understanding and

which clinicians can emancipate themselves from experience of patients?

their organisational settings by taking more time

with patients. For language teachers, training products will be

developed and will include samples of language

Language training and discourse transcripts for teaching purposes,

Language teachers, in order to contextualise demonstrating instances of effective and ineffective

language teaching, need information that describes communication, with sample exercises on why and

the culture of emergency departments, how how breakdowns have occurred in these contexts.

the systems work, and why clinicians and staff Teachers could also work with doctors to develop

operate the way they do. Of particular interest to language strategies that would allow them to pick

language educators will be a language in context up where they leave off in patient consultations.

framework, which will provide detailed discourse This article does not address the systemic

analysis of spoken interactions, so that professional issues with regard to teaching hospitals and ways

development can be based on real interactions to train doctors in history-taking. However, an

and real organisational contexts. The professional immediate observation is that practitioners need

development frameworks will be based on genre to develop listening skills, particularly listening

analysis of emergency department consultations for key information offered by patients and

between clinicians and patients, as well as analysis family members during consultations. In applying

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

of discourse semantics (for example, move and differential diagnoses, clinicians are trained to

speech function analysis, appraisal and lexical pursue specific lines of questioning but they should

cohesion). This analysis is adapted from Martin be better trained to identify key information given

(1992), Halliday and Matthiessen (2004), and or alluded to by patients, information that might

Eggins and Slade (1997) and enables description alert clinicians to underlying patient concerns.

of the different roles taken up by interactants and They should also be trained to redress the balance

the nature and function of exchanges. Grammatical of information exchange and questioning between

and lexical analyses will focus on mood, theme, themselves and their patients and to incorporate

process types, nominalisation, word frequency and greater contributions from patients.

collocations. Using genre analysis and real transcripts, teachers

The descriptive body of information will assist can illustrate the overall structure of consultations,

understanding of the range of ethnographic, including the recursive and frequently fragmented

linguistic and cultural factors that impact on and nature of history-taking in emergency departments.

influence effective communication in emergency Real consultation data shows why this can be

care. Specifically, the key finding that patients confusing to patients from different language

do not understand what is happening to them backgrounds. A focus on the use of tense and

highlights the need for clinicians to constantly aspect in transcripts of real history-taking and

check comprehension of what is being said. It how these are used to convey or seek information

reminds clinicians and hospital staff that their about crucial aspects of a patient’s health, the

practices and the environment of the emergency timing of the onset of symptoms and the use of

department do impact on patient comprehension. medical language would be useful to clinicians

Key questions they need to consider include: from different language backgrounds. Real data can

show them how complex the lexicogrammatical

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

20 structures of history-taking are and what is required hand and by political exigencies on the other.

from them in terms of structuring their own In Australia, as in many other places in the world,

consultations and questions. It can alert them to patients want patient-centred care that explores the

culturally specific ways of how this is done. When main reason for their visits, their concerns and their

it comes to the delivery of diagnoses, pedagogical need for information. To reach this goal clinicians

implications here include questions such as: need an integrated understanding of the world

from the patient perspective, their whole person,

• What is important about the diagnosis?

their emotional needs and life issues (Stewart

• How can sensitive information be conveyed to a 2001: 445). In the cut and thrust of the emergency

range of different patients in different situations? department observed, when consultations were

interrupted, patient stories were not picked up

• What are the best words to use? and complications were ignored. Patients were not

• What reassurance does the patient require? encouraged to ask questions and questioning by

doctors restricted the range of possible responses.

• What clarification is needed? Construal of pain and illness by patients and

doctors did not match.

• How can clinicians check whether patients have

At the political level the delivery of emergency

comprehended and absorbed what is said to

healthcare is creating significant unwelcome media

them?

coverage for governments and health departments

• What role can the family and culture play at key (eg Bragg-Kingsford 2007; Wingate-Pearce 2007).

moments in the consultation? The study outlined in this article, and the ongoing

research, may enable some systemic improvements

Many native speakers are not aware of the to occur, but at the very least it will make some

different kinds of questions and how these affect sense (Weick 1995) of institutional behaviours

ease of comprehension. In language-training and highlight how talk is socially organised

programs, language teachers can present these around healthcare practices. It will also illustrate

linguistic options to doctors from different how language and other factors, such as time of

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

language backgrounds. However, this information day, number and severity of presentations, levels

is also relevant for native English-speaking of seniority of emergency department staff, and

professionals when dealing with linguistically organisational and professional practices, impact on

diverse patients. the effectiveness of communication.

The pilot study described above is being followed

Conclusions by subsequent research in another four emergency

The ongoing research, of which this study is but departments in New South Wales hospitals over

a small part, is not yet complete. Triangulating three years and findings from that research will be

data sets to test for convergence, complementarity available towards the end of 2009.

and dissonance (Farmer et al 2006) will link the

findings arising from the recorded language data For more information about this project please contact:

and the ethnographic data from in situ physical

Diana.Slade@uts.edu.au or

observations. This will also be linked to the kinds

of organisational, professional and administrative Marie.Manidis@uts.edu.au

practices described in policy documents and

articulated by clinicians. By using complementary

data, the study will be able to shed light on the References

multiple dimensions of the patient experience of Atkinson, P. (1999). Medical discourse, evidentiality

emergency departments. and the construction of professional responsibility.

The study is timely. It puts the institutional In S. Sarangi & C. Robert (Eds.), Talk, work and

and professional practices of healthcare under the institutional order: Discourses in medicine, mediation

microscope at a time when a number of shifting and management settings (pp. 75 – 107). Berlin:

demands are being made by patients on the one Mouton de Gruyter.

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

21 Bragg-Kingsford, M. (2007, February 23). Hospital Flores, G., Rabke-Verani, B. A., Pine, W., &

GP clinics won’t fix emergency problems Sabharwal, A. (2002). The importance of cultural

(letter). Sydney Morning Herald, p. 10. and linguistic issues in the emergency care of

children. Pediatric Emergency Care, 18, 271–284.

Candlin, C. N. (2000). The Cardiff Lecture 2000 –

Retrieved October 18, 2007, from Medical

Reinventing the patient/client: New challenges

College of Wisconsin online database.

to health care communication. Retrieved

October 17, 2007, from Health Communication, Gumperz, J. J. (1982). Discourse strategies. London:

http://www.comminit.com/healthecomm/ Cambridge University Press.

lectures.php?showdetails=581

Gumperz, J. J., & Hymes, D. (Eds.). (1972).

Cicourel, A.V. (1981). Language and medicine. Directions in sociolinguistics. New York: Holt,

In C. Ferguson & S. B. Heath (Eds.), Language in Rinehart and Winston.

the USA (pp. 403-430). Cambridge: Cambridge

Gumperz, J. J., Jupp, T. C., & Roberts, C. (1991).

University Press.

Crosstalk at work. Havelock: National Centre for

Cicourel, A.V. (1985). Doctor–patient discourse. In Industrial Language Training.

T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Handbook of discourse analysis

Halliday, M. A. K. (1995). An introduction to functional

(Vol. 4, pp.193–202). New York: Academic Press.

grammar (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold.

Coiera, E. W., Jayasuriya, R. A., Hardy, J., Bannan,

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. (2004).

A., & Thorpe, M. E. C. (2002). Communication

An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.).

loads on clinical staff in the emergency

London: Edward Arnold.

department. Medical Journal of Australia, 176:

415–418. Retrieved November 8, 2006, from Health Care Complaints Commission. (2005).

Exlibris database and eMJA online, http://www. Annual report 2004–2005. Sydney: HCCC.

mja.com.au/public/issues/176_09_060502/

Iedema, R. (2005). Medicine and health: Intra- and

coi10481_fm.html

inter-professional communication. In K. Brown

Cordella, M. (2004). The dynamic consultation. (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of language and linguistics

A discourse analytical study of doctor–patient (pp. 745–751). Oxford: Elsevier.

communication. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

Iedema, R. (2006). (Post-)bureaucratising medicine:

Benjamins.

Health reform and the reconfiguration of

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research contemporary clinical work. In M. Gotti &

design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand F. Salager-Meyer (Eds.), Advances in medical

Oaks, CA: Sage. discourse: Oral and written contexts. Bern: Peter Lang.

Eggins, S., & Slade, D. (1997). Analysing casual Iedema, R. (Ed.). (2007). The discourse of hospital

conversation. London: Cassell. communication:Tracing complexities in contemporary

health care organizations. Hampshire/New York:

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis:

Palgrave MacMillan.

The critical study of language. London: Longman.

Joseph, T. (2007, August 2). Aiming for goals and

Farmer, T., Robinson, K., Elliott, S. J., & Eyles,

kicking behinds. Sydney Morning Herald, p. 8.

J. (2006). Developing and implementing a

triangulation protocol for qualitative health Kemmis, S. (in press). What is professional practice?

research. Qualitative Health Research, 16(3), Recognizing and respecting diversity in

377–394. Retrieved October 18, 2007, from understandings of practice. In C. Kanes (Ed.),

Sage Journals Database, http://qhr.sagepub.com/ Developing professional practice, Ripple Occasional

cgi/content/abstract/16/3/377 Paper 1.

Martin, J. (1992). English text: System and structure.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research

Council). (2004). Communicating with patients.

Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

22 NSW Health. (2005). Patient safety and clinical

quality program: First report on incident management

in the NSW public health system 2003–2004.

Publication SHPN (QSB) 040262: North

Sydney: Department of Health, NSW.

Roberts, C. (2000). Professional gatekeeping in

intercultural encounters. In S. Sarangi &

M. Coulthard (Eds.), Discourse and social life

(pp. 102–120). London: Longman Pearson

Education.

Sarangi, S. (in press). Other-orientation in patient-

centred health care communication: Unveiled

ideology or discoursal ecology? In G. Garzone &

S. Sarangi (Eds.), Discourse, ideology and ethics

in specialised communication. Berne: Peter Lang.

Sarangi, S., & Roberts, C. (Eds.). (1999). Talk, work

and institutional order, discourse in medical, mediation

and management settings. New York: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Silverman, D. (2001). Interpreting qualitative data:

Methods for analysing talk, text and interaction.

London: Sage.

Stewart, M. (2001). Towards a global definition

of patient centred care: The patient should be

the judge of patient centred care (editorial).

British Medical Journal, 322: 444–445. Retrieved

October 18, 2007, from BMJ Journals

Communicating in hospital emergency departments

online, http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/

full/322/7284/444

Tannen, D. (1984). Conversational style.

Norwood, NJ: Ablex Press.

Taylor, D. M., Wolfe, R., & Cameron, P. A. (2002).

Complaints from ED patients largely result

from treatment and communication problem.

Emergency Medicine Australasia, 14(1), 43–49.

Wallace, N. (2007, September 15–16). Doctors for

auction: Hospitals forced to bid for emergency

staff. Sydney Morning Herald, p. 1.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations.

London: Sage.

Wingate-Pearce, G. (2007, January 5). Mater under

siege. Newcastle Herald, p. 13.

Wodak, R. (2006). Medical discourse: Doctor–

patient communication. In K. Brown (Editor-in-

Chief), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics (2nd

ed.,Vol. 7, pp. 681–687). Oxford: Elsevier.

HERMINE SCHEERES, DIANA SLADE, MARIE MANIDIS, 2008 Volume 23 No 2

JEANNETTE McGREGOR and CHRISTIAN MATTHIESSEN

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- Assignment 3: Final Project - Comprehensive Literature ReviewDokument18 SeitenAssignment 3: Final Project - Comprehensive Literature ReviewJay JalaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- A Perfect Storm: Examining The Supply Chain For N95 Masks During COVID-19Dokument11 SeitenA Perfect Storm: Examining The Supply Chain For N95 Masks During COVID-19lucky prajapatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hes 008 - Sas 2Dokument2 SeitenHes 008 - Sas 2AIRJSYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Management in Cancer CareDokument27 SeitenNursing Management in Cancer CareFev BanataoNoch keine Bewertungen

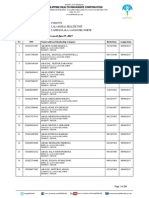

- Philhealth List of Assigned Members in Lala Rural Health UnitDokument299 SeitenPhilhealth List of Assigned Members in Lala Rural Health UnitJhonrie PakiwagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching More About LessDokument3 SeitenTeaching More About Lessdutorar hafuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive Development Plan for the City of San Fernando, PampangaDokument153 SeitenComprehensive Development Plan for the City of San Fernando, PampangaPopoy CanlapanNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSC 4 Years BooksDokument14 SeitenBSC 4 Years BooksJaved Noor Muhammad GabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 - The Home NUrseDokument3 SeitenModule 1 - The Home NUrsejessafesalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal2 JBI - Critical - Appraisal-Checklist - For - Analytical - Cross - Sectional - Studies2017Dokument8 SeitenJurnal2 JBI - Critical - Appraisal-Checklist - For - Analytical - Cross - Sectional - Studies2017Allysa safitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- PharmacistDokument2 SeitenPharmacistcrisjavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- State of The Province Address 2012 of Gov. Sol F. MatugasDokument289 SeitenState of The Province Address 2012 of Gov. Sol F. MatugaslalamanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Resin-Bonded Fixed Partial Denture As The First Treatment Consideration To Replace A Missing ToothDokument3 SeitenThe Resin-Bonded Fixed Partial Denture As The First Treatment Consideration To Replace A Missing ToothAngelia PratiwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Smtebooks - Com) Clinical Trials in Neurology - Design, Conduct, Analysis 1st Edition PDFDokument385 Seiten(Smtebooks - Com) Clinical Trials in Neurology - Design, Conduct, Analysis 1st Edition PDFnarasimhahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Download ebook Smith And Aitkenheads Textbook Of Anaesthesia 7Th Edition Pdf full chapter pdfDokument67 SeitenDownload ebook Smith And Aitkenheads Textbook Of Anaesthesia 7Th Edition Pdf full chapter pdfelaine.kern334100% (20)

- Nursing Core Competency Standards 2012Dokument27 SeitenNursing Core Competency Standards 2012JustinP.DelaCruz100% (1)

- PP-II End Semester Report - Yesu Raju S - 2004HS08916P - M.pharmDokument32 SeitenPP-II End Semester Report - Yesu Raju S - 2004HS08916P - M.pharmyesu56Noch keine Bewertungen

- JNT Pro 1Dokument132 SeitenJNT Pro 1vijaya reddymalluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Outcome Study - Short Form (SF-36)Dokument11 SeitenMedical Outcome Study - Short Form (SF-36)Arfia Chowdhury Arifa100% (1)

- Exploiting Transgenders Part 3 - The Funders & ProfiteersDokument48 SeitenExploiting Transgenders Part 3 - The Funders & ProfiteersHansley Templeton CookNoch keine Bewertungen

- KG College of Nursing VisitDokument7 SeitenKG College of Nursing VisitShubha JeniferNoch keine Bewertungen

- OPD Schedule of Faculty of Dental Sciences BHUDokument1 SeiteOPD Schedule of Faculty of Dental Sciences BHUG HhNoch keine Bewertungen

- BookDokument157 SeitenBookMaria Magdalena DumitruNoch keine Bewertungen

- VAKRATUNDA HOSPITAL PATIENT POLICYDokument11 SeitenVAKRATUNDA HOSPITAL PATIENT POLICYVIKRAM PATOLE100% (1)

- Post Operative CareDokument25 SeitenPost Operative CareS .BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manajemen Hiv.1Dokument92 SeitenManajemen Hiv.1Ariestha Teza AdipratamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter of MD Support To RNs - FinalDokument4 SeitenLetter of MD Support To RNs - FinalElishaDacey0% (1)

- DOH Guideline For The Screening of OsteoporosisDokument11 SeitenDOH Guideline For The Screening of OsteoporosisBasil al-hashaikehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Use Protaper NextDokument5 SeitenClinical Use Protaper NextGeorgi AnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trends in Healthcare Payments Annual Report 2015 PDFDokument38 SeitenTrends in Healthcare Payments Annual Report 2015 PDFAnonymous Feglbx5Noch keine Bewertungen