Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Characterising Affordances. The Descriptions-Of-Affordances-Model PDF

Hochgeladen von

Alejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Characterising Affordances. The Descriptions-Of-Affordances-Model PDF

Hochgeladen von

Alejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Characterising affordances: The

descriptions-of-affordances-model

Auke J. K. Pols, Eindhoven University of Technology, IPO 1.09, PO Box 513,

5600 MB Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Artefacts offer opportunities for action, ‘affordances’, that can be described on

various levels, from manipulations (‘pushing a button’) to social activities

(‘dialling a friend’). However, research in design into affordances has not

investigated what an ‘action’ is, nor has it distinguished those levels. This paper

addresses the question of which kinds of descriptions can be applied to

affordances. Its main claim is that different descriptions can apply to a single

affordance. On this claim a descriptions-of-affordances-model is built that shows

how these levels are connected, and that specifies what knowledge the artefact

user would need in order to perceive affordances under each kind of description.

The paper also shows several ways in which the descriptions-of-affordances-model

can contribute to affordance-based design.

Ó 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: affordance, perception, philosophy of design, product design,

psychology of design

I

t is obvious that humans can perceive objects and their properties, but only

since the last century has it been claimed that we can also directly perceive

opportunities for behaviour, or more specifically, opportunities for action

(Gibson, 1979).1,2 Gibson calls these opportunities for action affordances, and

argues that they are ubiquitous in our everyday environment: a single chair can

afford sitting on, standing on, throwing, etc. Not only has Gibson’s claim been

supported by various experiments in ecological psychology (e.g. Milner &

Goodale, 1995; J. Norman, 2002), designers have found it very useful to

work with the concept of affordances, and have investigated what ensures

that affordances of artefacts will be perceived (D. Norman, 1988/2002).3

This is an important issue, as user behaviour is influenced by perceived rather

than by real affordances.

Defining affordances as ‘opportunities for action’ means that our under-

standing of what affordances are can only be as precise as our understand-

Corresponding author: ing of what actions are. Unfortunately, a good examination of the action

Auke J.K. Pols concept is lacking in the literature on affordance-based design. This may

A.J.K.Pols@tue.nl not be problematic for simple cases (‘this chair affords sitting’), but it raises

www.elsevier.com/locate/destud

0142-694X $ - see front matter Design Studies 33 (2012) 113e125

doi:10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.007 113

Ó 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

questions about more complex ones. For example, when I turn on the light

by flipping the switch, does the switch afford flipping, or turning on the

light, or both? Simply saying that the light switch affords flipping and the

lighting system affords turning on the light does not seem to be a proper

solution: ascribing different affordances to different parts of artefacts does

not relieve designers of the need to formulate a proper concept of actions.

Besides, if I turn on the light by flipping the switch, I perform only one ac-

tion. That is, I do not have to do anything else besides flipping the switch in

order to turn on the light: I merely describe my action in a different way

(Anscombe, 1957/2000; Michaels, 2003; Vallacher & Wegner, 1987). And

if there is only one action here, rather than two, it seems that there can

only be one affordance here.

This paper aims to provide affordance-based design with a clear, conceptual

account of what actions are, and use this account to clarify the notion of

real or physical affordances as ‘opportunities for action’. Specifically, this

paper assumes that actions can be described in different ways (e.g.

Anscombe, 1957/2000), which implies that affordances can also be described

in different ways. This assumption is reminiscent of that behind the abstrac-

tion hierarchy, which assumes that a system can be described on different

levels (of abstraction) (e.g. Vicente & Rasmussen, 1992). Where abstraction

hierarchies describe whole systems on different levels, however, in this paper

I am primarily concerned with the kinds of descriptions that apply to arte-

fact or system affordances. The main question this paper will address will

thus be: which kinds of descriptions can apply to the affordances of arte-

facts, and what knowledge do we need in order to perceive what an artefact

affords for each kind of description? I will address this question in several

steps. In Section 1, I will treat four kinds of descriptions that can apply to

what humans do, as proposed by the philosophy of action. In Section 2, I

will construct a descriptions-of-affordances-model that mirrors the philo-

sophical model of descriptions of actions. In particular, although many pos-

sible descriptions can apply to a single affordance, I will argue that there

are four main kinds of descriptions that can apply to what an artefact af-

fords: how the artefact can be manipulated, what the reliable effects of

those manipulations will be, what can be done with the whole artefact

(or technical system) in itself, and what can be done with the whole artefact

as component of a socio-technical system. I will also argue that those four

kinds of affordance descriptions can be differentiated in terms of the knowl-

edge needed in order to perceive the affordance under that description. For

example, in order to perceive that a switch affords flipping, a different kind

of knowledge is needed (if knowledge is needed at all) than in order to per-

ceive that a switch affords illuminating the room. In the last section, Section

3, I will give a general recommendation for affordance-based design that de-

rives from the descriptions-of-affordances-model, show how my model can

114 Design Studies Vol 33 No. 2 March 2012

ground and specify existing recommendations like ‘give feedback’, and can

extend the scope of affordance-based design to socio-technical systems.

1 Four ways to describe what humans do

We do many things each day: sit, stand, sneeze, blink, go to work, switch on

the light, read and send emails, prepare dinner, greet friends. Some of these

doings are fairly simple and direct, like blinking, others require more time and

activity, like preparing dinner. Some doings require technical structures or ar-

tefacts to be present, such as turning on the light and sending emails, others

require the presence of certain social structures, such as greeting friends.

According to the philosophers Anscombe (1957/2000) and Davidson (1980: es-

say 1), the things you intentionally do directly, not by doing anything else or

by doing multiple things, are actions. Examples are (intentional) blinking, sit-

ting and waving. Actions have consequences, however, and often we describe

our actions in terms of their consequences. If I startle a burglar (unintentionally)

by turning on the light (intentionally) by flipping a switch by moving my hand,

I can be said to do a number of things. However, Anscombe and Davidson

hold that there is only one, basic, action here: moving my hand, as I do not

(intentionally) do this by doing something else.4 The other descriptions of

what I do are all descriptions of the same action, moving my hand, but in terms

of some of its many consequences.

Sometimes we intend to do things that can only be realised by performing mul-

tiple actions. For example, when I call a friend, I do not just do this by doing

something else, but by doing several things, or performing several actions,

each with particular consequences. For example, calling a friend could require

me to press the button for the first digit of his phone number on my phone then

the button for the second digit, and so on, until I have selected the whole num-

ber and can press the ‘dial’-button and wait to be connected. In this case, what

I describe with ‘calling a friend’ is that I am executing a plan (Bratman, 1987).

In this case, I am executing a particular ‘use plan’ for my phone (Houkes &

Vermaas, 2004, 2010). As the example shows, executing a plan can include

both executing actions and waiting.

Finally, it is important to note that, while all physical actions have physical

consequences, some of those actions also have social consequences (Searle,

1996). If my action is intentional under any description in terms of its social

consequences, it can be said to be a social action. Examples are making a prom-

ise, or challenging someone to a duel. Similarly, plans can be social if they are

aimed at bringing about a social rather than a physical change: running for

president; blackmailing my competitor. Social actions and plans thus work

in the same way as physical actions and plans, but with intended effects in

the social rather than in the physical realm. If artefacts can be said to afford

actions and the execution of plans by virtue of belonging to a particular

Characterising affordances 115

technical system, they can afford social actions by virtue of belonging to a par-

ticular socio-technical system (Kroes, Franssen, Van de Poel, & Ottens, 2006;

Ottens, Franssen, Kroes, & Van de Poel, 2006).

If it is assumed that affordances are opportunities for action, then they would

mirror the structure of actions. In that case, there would be basic affordances

that afford basic actions.5 Those affordances would then afford actions under

all other kinds of descriptions, by affording these basic actions. The light

switch affords a basic action, namely, moving your hand against it. The light

switch affords actions under other descriptions as well: turning on the light,

startling the burglar, etc. These, then, would all be the same affordance under

different descriptions. Of course, the light switch in itself does not afford turn-

ing on the light: it needs to be connected to electric wiring and a light bulb. The

same holds for basic actions: your action of moving your hand is not an action

of turning on the light if the light switch is disconnected. However, given that

the light switch is connected, the one action is the other, since you do not need

to do anything else to turn on the light beyond moving your hand against the

switch in a certain way. Similarly, the one affordance is the other, since the

light switch does not have to afford anything else to you beyond moving

your hand against the switch, in order to afford turning on the light. What

is important here is that the switch affords these actions under various descrip-

tions by affording the basic action. If the switch does not afford moving your

hand against it, e.g. because it has broken off, then it does not afford flipping,

turning on the light, startling the burglar, etc.

Moving from actions to plans, it can be said that an artefact affords executing

a plan when it affords the actions required for executing the plan. This can e.g.

be realised by having the artefact offer a number of (basic) affordances that

need to be acted on in a certain sequence in order to execute the plan. For ex-

ample, my phone affords dialling my friend, because it affords selecting any of

the digits from 0 to 9 (by affording pressing certain of its keys) and affords di-

alling the chosen number (by affording pressing the dial key). An artefact af-

fords a social action, finally, if it affords a basic action or plan that can have at

least one particular consequence in the social, rather than physical realm, and

the action or plan can be described in terms of that consequence. For example,

a luggage monitoring system, because of the socio-technical context in which it

functions, could be said to afford ‘preventing terrorist attacks’ and ‘improving

the safety of plane travellers’.

In this section I have proposed that the structure of affordances mirrors that of

actions. The next step is to investigate what knowledge the user needs in order

to perceive the affordance under that kind of description. I will explicate this in

the descriptions-of-affordances-model. I will talk about ‘perceived affordan-

ces’ for each kind of description, where I assume with Norman that perception

can include interpretation and/or past knowledge (as opposed to sensing; see

116 Design Studies Vol 33 No. 2 March 2012

Hartson, 2003), and thus that it is possible to perceive affordances under high

levels of description, like ‘dialling a friend’ or ‘improving the safety of plane

travellers.’

2 The descriptions-of-affordances-model

In this section I will work out the four proposed kinds of affordance descrip-

tions, show how these levels connect, and argue what kind of knowledge a user

would need in order to perceive the affordance under that description.

In the previous section, I argued that there are basic affordances that corre-

spond to basic actions. These affordances I will call manipulation opportunities.

They are affordances at the first, lowest level of description, as they afford in-

tentional actions at the lowest level of description: grasping, pushing, etc. As

such, they map nicely onto the original Gibsonian concept of affordances that

can be directly perceived and fit the neuropsychological evidence for the direct

perceivability of affordances (J. Norman, 2002). In practice, users rarely en-

counter completely unknown artefacts without any signs or symbols, but if

they do, the only affordances of those artefacts they will be able to perceive

will be manipulation opportunities: can they stand on them? Push them?

Pull at some parts, or twist them? They will then, of course, need to experiment

with the artefact in order to find out whether those perceived affordances are

real affordances. Just as they can only find out if they can do something new by

trying to do it, they can only find out if some unknown artefact affords X-ing

by trying to X with or on the artefact. Perceived basic affordances can tell them

where to start experimenting, and what actions they might try out first.

By experimenting, or gaining knowledge about the artefact in some other way,

users might discover reliable connections between manipulations and their ef-

fects. They might find out that pulling the trigger of a loaded gun will reliably

fire it (‘this gun affords firing’), or that pressing the ‘A’ key on the keyboard of

their computer will make an ‘A’ appear in their text editor (‘this computer af-

fords typing A’s’). In short, they learn what the effects of their manipulations

are. I will call affordances described in terms of the effects of manipulations

effect opportunities. Although abstract knowledge can help the user in learning

effect opportunities e the ‘A’ printed on the key that will make an ‘A’ appear

in a text editor is there for that reason, effect opportunities can be directly per-

ceiveable. All that would strictly be needed for an observer to directly perceive

effect opportunities would be to have a simple psychological mechanism that

can correlate causes and effects.

According to You and Chen (2007), it is the task of product semantics to link

affordances to their intended functions, via design but also via labels, symbols,

etc., removing the need for experimentation. Norman (1999) similarly argues

that software buttons and icons do not afford clicking e every pixel on a com-

puter screen affords clicking e but that those buttons are symbols or

Characterising affordances 117

conventions that advertise an affordance. The descriptions-of-affordances-

model shows how product semantics (including adding buttons or icons) is

related to affordance design: it allows the user to perceive effect opportunities,

or higher-level descriptions of basic affordances. Also, effect opportunities

seem similar to Hartson’s (2003) functional affordances, in the sense that func-

tional affordances are physical affordances with a reference to their purpose

included in the description (‘this doorknob can be grasped and turned in order

to open the door’). Effect opportunities are also physical affordances described

in terms of their effects, though these effects may not always be purposes in-

tended by the designer (‘this shoddy doorknob affords pulling it loose from

the door by affording grasping and turning’). Finally, as users often bring

about effects by doing other things, such as turning on the light by flipping

the switch, this account of actions explains how Gaver’s (1991) proposed no-

tion of nested affordances works; how manipulation opportunities are con-

nected to effect opportunities, or even use opportunities, which I will

address next.

Affordances can also be described on a third level, in terms of what the user

can do with the artefact, rather than how to act on it. I will call these kinds

of affordances use opportunities. What the user can do with an artefact often

depends on a number of basic affordances: just like goal-directed actions

can be strung together in goal-directed plans, as when cooking a recipe, a num-

ber of basic affordances of an artefact taken together can enable a whole arte-

fact to afford an action under a high-level description. My computer affords

writing a paper because acting on its basic affordances realises effects (de-

scribed as ‘typing an “a”’, ‘deleting a letter,’ etc.) that contribute to the use op-

portunity of the whole. In other words: by affording text insertion, deletion,

etc., my computer affords writing a paper. These basic affordances can all

be present and perceivable at the same time, as with the keys on a phone, or

they can be sequential (Gaver, 1991), that is, that acting on one affordance cre-

ates or highlights other affordances (e.g. when the selection of a menu item in

a word processor makes a drop-down menu appear). Perceiving use opportu-

nities seems to be what Searle (1996) meant when he said that humans often

perceive objects as functional, for example, that we see bathtubs rather than

enamel-covered iron concavities containing water (p. 4). Sometimes, perceiv-

ing the context or socio-technical system of which the artefact is a part is nec-

essary to perceive its use opportunities (e.g. Vaesen, 2008: p. 56).

It does seem that mental representations or abstract knowledge are needed in

order to perceive use opportunities; they require too much interpretation or

past knowledge to be directly perceivable. Norman argues that the designer

needs to provide the user with the information needed to construct a correct

mental model of the artefact, that is, knowledge of what effects our actions

will have on the functioning of the whole artefact. An abstraction hierarchy

(e.g. Vicente & Rasmussen, 1992) could be used as an external mental model

118 Design Studies Vol 33 No. 2 March 2012

that would fit the descriptions-of-affordances-model particularly well: for each

affordance, it could show how an action on it would affect the artefact on dif-

ferent levels of description. These effects on the artefact, in turn, determine

that artefact’s effect and use opportunities.

As an alternative to mental models, Houkes and Vermaas (2004; see also

Houkes, Vermaas, Dorst, & De Vries, 2002; Houkes & Vermaas, 2010) argue

that the designer should communicate the use plan of the artefact to the user,

that is, knowledge that a certain sequence of actions will lead to the realisation

of a goal. The designer should in addition communicate information regarding

the proper context of use together with the use plan, as well as the need for

auxiliary items, if any, and whether the user would need special skills in oper-

ating the artefact. It is possible for users to construct use plans themselves

rather than relying on one provided by the designer (if any is provided), but

that would involve gaining knowledge about the artefact as well, e.g. by

experimenting.

Finally, affordances of artefacts can also be described in terms of their effects

on the social, rather than physical world. This is because artefacts almost never

operate in isolation, as purely technical systems: they are usually part of larger

socio-technical systems that themselves have specific functions (Kroes et al.,

2006; Ottens et al., 2006). Gibson seems to acknowledge this when he writes:

“.the real postbox (.) affords letter-mailing to a letter-writing human in

a community with a postal system. This fact is perceived when the postbox

is identified as such.” (1979: p. 139). Just as an artefact can offer a use oppor-

tunity by virtue of having a particular set of affordances, it can also offer an

opportunity for action by virtue of being part of a system consisting of arte-

facts, humans, institutional arrangements, etc. I will call affordances under

this kind of description activity opportunities. These would correspond with so-

cial actions in action theory: raising your hand is asking a question if the so-

cial/institutional setting is that of a talk, meeting, etc. Similarly, a debit card

reader affords conducting a payment, and passing your debit card through

the reader is conducting a payment, provided all kinds of other artefacts

and institutional arrangements are in place. Abstract social and institutional

knowledge is needed in order to perceive activity opportunities.

In this section I have explicated the descriptions-of-affordances-model and ar-

gued that there are four kinds of descriptions that can apply to affordances. An

overview of the model can be found in Table 1.

Let me add that these different kinds of affordance descriptions are not appli-

cable to every artefact. They will all be applicable to complex technical systems

such as computers and cars, but for simple artefacts, some distinctions be-

tween kinds may collapse. For example, while a spoon can be manipulated

in different ways, manipulating the spoon always means manipulating the

Characterising affordances 119

Table 1 The descriptions-of-affordances-model

Affordance Corresponding Knowledge needed Examples of actions

concept action afforded

theory

Opportunity for Basic action None; only neuropsychological Pulling a trigger, hitting

manipulation mechanisms a glass pane, pressing

(Milner & Goodale, 1995; a button.

J. Norman, 2002)

Opportunity for Action described None; only neuropsychological Firing a gun, breaking

effect in terms of its mechanisms a glass pane, typing an

effects (Milner & Goodale, 1995; ‘a’.

J. Norman, 2002);

optionally knowledge of

functions of parts

(You & Chen, 2007),

or cultural symbols

(Norman, 1999)

Opportunity for use Plan Mental models Shooting a person,

(D. Norman, 1988/2002); obtaining

use plans an emergency hammer,

(Houkes & Vermaas, 2004) writing a paper.

Opportunity for Social action Abstract, institutional Murdering an enemy,

activity and social escaping a crashed

knowledge (Kroes et al., 2006; vehicle,

Ottens et al., 2006; Searle, 1996) working out a

psychological

theory.

whole artefact, so there will be no use opportunities that are not also effect op-

portunities or manipulation opportunities. This redundancy, however, is nec-

essary to accommodate the different kinds of affordance descriptions that are

applicable to more complex artefacts or systems.

3 Applying the descriptions-of-affordances-model

In this final section I will show three ways in which the descriptions-of-

affordances-model can contribute to affordance-based design (e.g. Maier &

Fadel, 2001, 2009). First, I will give a general recommendation for design sug-

gested by the descriptions-of-affordances-model. Second, I will show how the

descriptions-of-affordances-model can ground and specify design recommen-

dations like ‘give feedback’. Third, I will show how the descriptions-

of-affordances-model can extend the scope of affordance-based design to

socio-technical systems.

As a general recommendation, if a certain system structure should possess

a certain function, according to the descriptions-of-affordances-model this

means that the system should have an affordance described on a high level,

say, a use or activity opportunity. This can be realised by ensuring a) that

the system has the proper (basic) affordance(s), and b) that the system

120 Design Studies Vol 33 No. 2 March 2012

structure is such that this affordance (these affordances) can be redescribed as

the desired use or activity opportunity. For example, if an artefact should af-

ford ‘lighting the room’, it should afford a manipulation like ‘flipping a switch’,

and the artefact should be built so that the light comes on when the switch is

flipped. In other words: the user should be able to light the room by flipping

the switch. The next step is to make sure c) that the use opportunity can be per-

ceived, so that the user can see what can be done with the artefact, and d) that

the manipulation opportunity can be perceived, so that users can see how they

can actually use the artefact. Note that it is possible to have c) without d): I

might perceive the light bulb and know that it can be used to light the

room, but if I do not manage to find the switch, I will not be able to actually

turn on the light.

Furthermore, if a certain system structure can be used in a way that is unac-

ceptable, the descriptions-of-affordances-model can be used to find possible

solutions. For example, the sharp edge of a razor affords cutting hairs, but

also cutting skin. In order to find a design solution that does not enable cutting

skin, one option is describing the desired action (‘cutting hairs’) on a higher

level, possibly in terms of the goal of the action (say, ‘getting a smooth

face’), and finding an alternative route to this goal (e.g. by depilating). Alter-

natively, the designer could look for a way to ensure that the description of

‘cutting skin’ does no longer apply to the affordances of the razor, while the

description of ‘cutting hairs’ does (this is e.g. the case with electric razors,

that contain a protective head to ensure that the blades cannot reach the

skin) (see also Maier, Sachs, & Fadel, 2009).

The descriptions-of-affordances-model can also ground and specify existing

recommendations for design: here I will show how the model can specify the

recommendation to ‘give feedback’.

In order to perceive effect opportunities, users should be able to register a reli-

able connection between their actions and the resulting behaviour of the arte-

fact. Therefore, the artefact’s behaviour should be predictable, and the users

should be given feedback on the effects of their manipulations. Norman em-

phasises the importance of giving immediate and obvious feedback. This

can tell the user what result has been accomplished and ensures that users

can determine the relationship between their actions and the effects on the sys-

tem. The descriptions-of-affordances-model adds that feedback is necessary to

go from perceiving manipulation opportunities to perceiving effect opportuni-

ties. Also, the model can offer a more specific recommendation: users should

not just receive feedback, but they should receive feedback on different levels.

More accurately, if different kinds of descriptions apply to their actions with

the artefact, they should receive different kinds of feedback to indicate whether

the action, described in that way, was successful. This does not only hold for

functional changes within the system (‘Did the light come on when I flipped the

Characterising affordances 121

switch?’), but also, perhaps even more so, for unwanted or possibly harmful

changes (‘No; by flipping the switch you blew the fuse.’)

At least, the user should receive feedback that the manipulation was success-

ful. For example, when pressing a button, there is direct feedback: the button is

pushed back. This direct feedback is absent in for example touchpads, where

the user has to rely on indirect feedback to perceive that the action was success-

ful (a light, a tone, etc.). Where direct feedback is important for knowing that

a manipulation is successful, indirect feedback is important for knowing that

a successful manipulation is also a successful use of the artefact. Good pedes-

trian traffic lights, for example, offer feedback on all relevant levels. They have

buttons that are pushed inwards when pressed. They have lights near the but-

ton to show that the button press was successfully registered and constituted

a successful use of the artefact. As Norman says, immediate feedback is impor-

tant here. The light turning green is delayed feedback that the action was suc-

cessful, but until the feedback occurs, the user cannot distinguish between

delayed feedback on a successful action and no feedback on an unsuccessful

one. Finally, other lights turn red to stop the traffic, showing that the socio-

technical system works as it should: the button press is, in these circumstances,

also a way to regulate traffic such that all road users can arrive safely at their

respective destinations. Since with a traffic light pressing the button is operat-

ing the traffic light, that is, there is no distinction between effect opportunities

and use opportunities, the light turning green is both feedback on the success-

ful action on and the successful use of the artefact.

Intimately related to the recommendation of giving feedback is the recommen-

dation to give feedforward, or to provide the user with clues as to what effect

will result from a specific manipulation. This can be a design solution, for ex-

ample, placing the control (say, a light switch) close to the function (the light).

It can also be symbolic, like putting a symbol or a label on a switch. Norman

argues that if design depends on labels, it may be faulty (p. 78). The

descriptions-of-affordances-model shows that this depends on the level that

the label announces an opportunity on. It may be difficult to find an intuitive

design alternative for a label that announces an effect opportunity, for exam-

ple, a light switch with a picture of a glowing light bulb on it. However, the

label can also announce a manipulation opportunity, say, a light switch with

the word ‘press’ on it. Here, Norman’s recommendation holds, for the infor-

mation denoting a manipulation opportunity should be made clearly avail-

able, not hidden behind clumsy or ‘artful’ design. In Gibson’s words, the

(basic) affordances should be fully specified in the stimulus information

(1979: p. 140).

Knowing what an artefact does in itself is good, but no artefact works in iso-

lation. Artefacts are connected to humans and to each other, their use and be-

haviour regulated by institutions and social procedures. In other words, many

122 Design Studies Vol 33 No. 2 March 2012

artefacts are part of socio-technical systems, systems that themselves have in-

tended functions and need to contain artefactual, human and institutional

parts in order to fulfill those intended functions (Kroes et al., 2006). An exam-

ple would be a luggage monitoring service at an airport that requires an arti-

ficial scanner, a human operator and regulations concerning luggage handling

and safety in order to fulfill the service’s intended function within the larger

civil aviation system. Given this additional context of the scanner, the scanner

affords actions under new descriptions that take the socio-technical system in

account. For example, as an artefact, the scanner affords ‘registering certain

substances in portable containers’. As part of a socio-technical system, the

scanner also affords ‘detecting bombs’, ‘improving the safety of plane travel-

lers’, etc. Given that many artefacts are designed to function within the context

of specific socio-technical systems, it is important for the designer to show how

the descriptions of the affordances of the artefact as a technical system relate to

the descriptions that apply to the affordances of the artefact by virtue of the

socio-technical system in which the artefact is supposed to function.

While Norman does not concern himself with socio-technical systems or the

place artefacts have in them, building a bridge between artefacts as technical

systems and artefacts as parts of socio-technical systems is a natural step in

the descriptions-of-affordances-model. Strictly speaking, it may not be the re-

sponsibility of the designer of the artefact to show what activity opportunities

the artefact affords by virtue of belonging to a certain socio-technical system,

but rather that of the designer of the socio-technical system. Still, it might have

distinct advantages to do so, if only for marketing purposes. People do not buy

modems because they afford modulating and demodulating analog signals to

encode and decode digital information, though that could be said to be the

technical function of a modem. Rather, people buy modems because they

can be made a part of a socio-technical system and then afford emailing, surf-

ing the internet, etc.

In this section I have shown what general recommendation for design the

descriptions-of-affordances-model gives, and how it can ground and specify

specific recommendations. I have also shown how the descriptions-of-

affordances-model can extend the scope of affordance-based design from tech-

nical artefacts to socio-technical systems.

4 Conclusion

In this paper I have asked the question: which kinds of descriptions can apply

to the affordances of artefacts, and what knowledge do we need to perceive

what an artefact affords for each kind of description? I have addressed this

question in two stages. First, in Section 1, I have argued that affordances

are like actions in the sense that there are basic affordances, and those can

be described in different ways. Second, in Section 2, I have worked out this

idea in the descriptions-of-affordances-model, a structured account of the

Characterising affordances 123

kinds of descriptions that can apply to affordances. The descriptions-of-

affordances-model states that affordances of artefacts can be described on

four levels: that of the manipulation opportunities, that are very basic, Gibso-

nian affordances; effect opportunities, that describe affordances in terms of the

effects of their manipulations; use opportunities, that describe affordances in

terms of their effect on the whole artefact; and activity opportunities, that de-

scribe affordances in terms of their effects on the particular socio-technical sys-

tem the artefact belongs to. I have also investigated what knowledge is needed

in order to perceive what an artefact affords on each of these levels of descrip-

tion. In Section 3, finally, I have shown how the model can give a general rec-

ommendation for design, as well as specify known design recommendations

and extend the scope of affordance-based design to socio-technical systems.

Notes

1. For Gibson (1979), who describes affordances as what the environment provides or offers

the animal, objects can afford both doings or actions (have goal affordances) and hap-

penings (have happening affordances; Scarantino, 2003). For example: a fire affords

cooking meat (goal affordance) but also burning yourself (happening affordance). This

paper is concerned only with goal affordances: though happening affordances are argu-

ably underexplored in affordance-based design, their treatment is outside the scope of

this paper.

2. In this paper I will concentrate on visual perception and to a lesser degree on tactile per-

ception, as vision and touch are the senses that can with most accuracy locate objects and

their affordances relative to the observer. It is possible, however, to perceive affordances

with other senses as well (Gaver, 1991).

3. Whenever I refer to Norman, I refer to D. Norman (1988/2002) unless stated otherwise.

4. Concepts similar to that of the basic action are also used in psychology, e.g. the basic

level components of action of Humphreys, Forde, and Riddoch (2001) and the Basic Ac-

tion Concepts of Schack (2004). My particular interpretation of the basic action concept

is inspired by Hornsby’s definition of intentionally basic descriptions of actions, a formal

version of which she elaborates and defends in (1980: pp. 78e79).

5. Gibson uses the term ‘basic affordance’ in passing (p. 143). He does not specify it, but it

seems compatible with my use of the term. Note that, contrary to what the term implies,

there are no non-basic affordances: only different ways of describing a particular

affordance.

References

Anscombe, G. E. M. (2000). Intention (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press. (Original work published 1957, Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Bratman, M. (1987). Intention, plans and practical reason. Cambridge, MA: Har-

vard University Press.

Davidson, D. (1980). Essays on actions and events. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gaver, W. W. (1991). Technology affordances. In S. P. Robertson, G. M. Olson,

& J. S. Olson (Eds.), Proceedings of CHI’91 (pp. 79e84). New York: ACM.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin.

Hartson, R. (2003). Cognitive, physical, sensory and functional affordances in in-

teraction design. Behaviour & Information Technology, 22(5), 315e338.

Hornsby, J. (1980). Actions. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Houkes, W. N., & Vermaas, P. E. (2004). Actions versus functions: a plea for an

alternative metaphysics of artifacts. The Monist, 87(1), 52e71.

124 Design Studies Vol 33 No. 2 March 2012

Houkes, W. N., & Vermaas, P. E. (2010). Technical functions: on the use and de-

sign of artefacts. Dordrecht: Springer.

Houkes, W. N., Vermaas, P. E., Dorst, K., & De Vries, M. J. (2002). Design and

use as plans: an action-theoretical account. Design Studies, 23, 303e320.

Humphreys, G. W., Forde, E. M. E., & Riddoch, M. J. (2001). The planning and

execution of everyday actions. In B. Rapp (Ed.), What deficits reveal about the

human mind (pp. 565e589). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Kroes, P., Franssen, M., Van de Poel, I., & Ottens, M. (2006). Treating socio-

technical systems as engineering systems: some conceptual problems. Systems

Research and Behavioral Science, 23, 803e814.

Maier, J.R.A., & Fadel, G.M. (2001). Affordance: the fundamental concept in en-

gineering design. In: Proceedings of the ASME design theory and methodology

conference, Pittsburgh, PA. Paper no. DETC2001/DTM-21700.

Maier, J. R. A., & Fadel, G. M. (2009). Affordance based design: a relational the-

ory for design. Research in Engineering Design, 20, 13e27.

Maier, J.R.A., Sachs, R. & Fadel, G.M. (2009). A comparative study of quanti-

tative scales to populate affordance structure matrices. In: Proceedings of the

ASME design theory and methodology conference. Paper no. DETC2009-

86524. San Diego, CA; pp. 863e872.

Michaels, C. F. (2003). Affordances: four points of debate. Ecological Psychology,

15(2), 135e148.

Milner, D., & Goodale, M. (1995). The visual brain in action. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

Norman, D. A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions 38e42,

(May/June).

Norman, D. A. (2002). The design of everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

(Original work published 1988 as The Psychology of Everyday Things).

Norman, J. (2002). Two visual systems and two theories of perception: an attempt

to reconcile the constructivist and ecological approaches. Behavioral and Brain

Sciences, 25, 73e144.

Ottens, M., Franssen, M., Kroes, P., & Van de Poel, I. (2006). Modelling infra-

structures as socio-technical systems. International Journal of Critical Infra-

structures, 2, 133e145.

Scarantino, A. (2003). Affordances explained. Philosophy of Science, 70, 949e961.

Schack, T. (2004). The cognitive architecture of complex movement. International

Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2, 403e438.

Searle, J. R. (1996). The construction of social reality. London: Penguin Books.

Vaesen, K. (2008). A philosophical essay on artifacts and norms. Doctoral disser-

tation. Eindhoven University, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. Retrieved 4

May 2011 from: http://alexandria.tue.nl/extra2/200811602.pdf.

Vallacher, R. R., & Wegner, D. M. (1987). What do people think they’re doing?

Action identification and human behavior. Psychological Review, 94(1), 3e15.

Vicente, K. J., & Rasmussen, J. (1992). Ecological interface design: theoretical

foundations. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 22(4),

589e606.

You, H., & Chen, K. (2007). Applications of affordance and semantics in product

design. Design Studies, 28, 23e38.

Characterising affordances 125

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- AphasiaDokument208 SeitenAphasiaErika Velásquez100% (4)

- Florence Nightingale BIOGRAPHY PDFDokument224 SeitenFlorence Nightingale BIOGRAPHY PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secret Hitler Print and Play PDFDokument13 SeitenSecret Hitler Print and Play PDFCanan OrtayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funciones Ejecutivas Tirapu Muñoz CespedesDokument13 SeitenFunciones Ejecutivas Tirapu Muñoz Cespedesmariaclararonqui100% (1)

- 130 - Gestures and Iconicity: 5 - ReerencesDokument21 Seiten130 - Gestures and Iconicity: 5 - ReerencesAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Pantomime To Actual Use. How Affordances Can Facilitate Actual Tool-UseDokument7 SeitenFrom Pantomime To Actual Use. How Affordances Can Facilitate Actual Tool-UseAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of Executive Dysfunction During Activities of Daily Living in SchizophreniaDokument12 SeitenAssessment of Executive Dysfunction During Activities of Daily Living in SchizophreniaAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bleuler Psychology PDFDokument666 SeitenBleuler Psychology PDFRicardo Jacobsen Gloeckner100% (2)

- VygotskyDokument40 SeitenVygotskynatantilahun100% (4)

- Skinner (1950) Classics in The History of PsychologyDokument20 SeitenSkinner (1950) Classics in The History of PsychologyAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On How We Can Act - Costall PDFDokument7 SeitenOn How We Can Act - Costall PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hergenhahn (2013) Humanistic (Third-Force) Psychology PDFDokument36 SeitenHergenhahn (2013) Humanistic (Third-Force) Psychology PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On How We Can Act - Costall PDFDokument7 SeitenOn How We Can Act - Costall PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Connection Between Lenguage and The World. A Paradox of The Linguistic Turn PDFDokument15 SeitenThe Connection Between Lenguage and The World. A Paradox of The Linguistic Turn PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beyond Nature-Nurture - Essays in Honor of Elizabeth Bates - Routledge (2005)Dokument390 SeitenBeyond Nature-Nurture - Essays in Honor of Elizabeth Bates - Routledge (2005)santimosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 Communicative Mediation by Adults in The Construction of Symbolic Uses by InfantsDokument19 Seiten2018 Communicative Mediation by Adults in The Construction of Symbolic Uses by InfantsAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- THE AGEING BRAIN. P Sachdev PDFDokument359 SeitenTHE AGEING BRAIN. P Sachdev PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language, Mind, and ReadingDokument4 SeitenLanguage, Mind, and ReadingAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canonical Affordances - The Psychology of Everyday Things - Research Aid - Academic EssaysDokument9 SeitenCanonical Affordances - The Psychology of Everyday Things - Research Aid - Academic EssaysAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Everyday Action in SchizophreniaDokument9 SeitenEveryday Action in SchizophreniaAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semiotics at The Circus Semiotics Communication and CognitionDokument208 SeitenSemiotics at The Circus Semiotics Communication and Cognitiontapper0Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Study of Real Skills (W. T. Singleton (Auth.)Dokument313 SeitenThe Study of Real Skills (W. T. Singleton (Auth.)Alejandro Israel Garcia Esparza0% (1)

- Learning and Generalization of Behavior-Grounded. Tool Affordances - SinapovDokument6 SeitenLearning and Generalization of Behavior-Grounded. Tool Affordances - SinapovAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affordance Gibson3 PDFDokument16 SeitenAffordance Gibson3 PDFtomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pragmatic Aspects of Human Comunication - Marshall PDFDokument185 SeitenPragmatic Aspects of Human Comunication - Marshall PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia Esparza100% (1)

- An Outline of A Theory of Affordances - Chemero PDFDokument16 SeitenAn Outline of A Theory of Affordances - Chemero PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tools For The Body (Schema) PDFDokument8 SeitenTools For The Body (Schema) PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Does A Chair Afford - A Heideggerian Perspective of Affordanc PDFDokument14 SeitenWhat Does A Chair Afford - A Heideggerian Perspective of Affordanc PDFAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- DWF 300Dokument36 SeitenDWF 300Josè Ramòn Silva AvilèsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tema Tubesheet Calculation SheetDokument1 SeiteTema Tubesheet Calculation SheetSanjeev KachharaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FEE Lab Manual FinalDokument86 SeitenFEE Lab Manual FinalbalasubadraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ASTM D1265-11 Muestreo de Gases Método ManualDokument5 SeitenASTM D1265-11 Muestreo de Gases Método ManualDiana Alejandra Castañón IniestraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bio GasDokument4 SeitenBio GasRajko DakicNoch keine Bewertungen

- EE020-Electrical Installation 1-Th-Inst PDFDokument69 SeitenEE020-Electrical Installation 1-Th-Inst PDFSameera KodikaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ValvesDokument1 SeiteValvesnikhilNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3UG46251CW30 Datasheet enDokument5 Seiten3UG46251CW30 Datasheet enDante AlvesNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Phase ChangesDokument28 SeitenOn Phase Changesapi-313517608Noch keine Bewertungen

- SimonKucher Ebook A Practical Guide To PricingDokument23 SeitenSimonKucher Ebook A Practical Guide To PricingHari Krishnan100% (1)

- (L4) - (JLD 3.0) - Semiconductors - 30th DecDokument66 Seiten(L4) - (JLD 3.0) - Semiconductors - 30th DecAshfaq khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Física Básica II - René CondeDokument210 SeitenFísica Básica II - René CondeYoselin Rodriguez C.100% (1)

- Piping SpecificationDokument3 SeitenPiping SpecificationShashi RanjanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thermal Imaging Tech ResourceDokument20 SeitenThermal Imaging Tech Resourceskimav86100% (1)

- New Generation Shaft KilnDokument2 SeitenNew Generation Shaft Kilndocument nugrohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Windows Romote ControlDokument6 SeitenWindows Romote ControllianheicungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aadhaar Application FormDokument4 SeitenAadhaar Application Formpan cardNoch keine Bewertungen

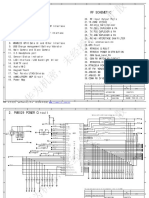

- Aiwa MC CSD-A120, A140 PDFDokument35 SeitenAiwa MC CSD-A120, A140 PDFRodrigo NegrelliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hydraulic BrakeDokument29 SeitenHydraulic Brakerup_ranjan532250% (8)

- CRD MethodDokument12 SeitenCRD MethodSudharsananPRSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ruth Clark ResumeDokument2 SeitenRuth Clark Resumeapi-288708541Noch keine Bewertungen

- Is 15462 2004 Modified Rubber BItumen PDFDokument16 SeitenIs 15462 2004 Modified Rubber BItumen PDFrajeshji_000100% (3)

- Method Statement of Refrigran Pipe Insulation and Cladding InstallationDokument16 SeitenMethod Statement of Refrigran Pipe Insulation and Cladding InstallationOdot Al GivaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5th Issue October 10Dokument12 Seiten5th Issue October 10The TartanNoch keine Bewertungen

- McbcomDokument72 SeitenMcbcomopenjavier5208Noch keine Bewertungen

- C8813 ÇDokument39 SeitenC8813 ÇZawHtet Aung100% (1)

- Pre-Disciplinary and Post-Disciplinary Perspectives: Bob Jessop & Ngai-Ling SumDokument13 SeitenPre-Disciplinary and Post-Disciplinary Perspectives: Bob Jessop & Ngai-Ling SumMc_RivNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group B04 - MM2 - Pepper Spray Product LaunchDokument34 SeitenGroup B04 - MM2 - Pepper Spray Product LaunchBharatSubramonyNoch keine Bewertungen