Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Reasons Admin

Hochgeladen von

Zipho0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

57 Ansichten16 SeitenAdmin Action - Grounds of review: Reasons

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenAdmin Action - Grounds of review: Reasons

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

57 Ansichten16 SeitenReasons Admin

Hochgeladen von

ZiphoAdmin Action - Grounds of review: Reasons

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 16

Reasons

Wits Law School

16-17 April 2018

Readings

• Quinot, Chapter 8 (193-218) & Hoexter 470-485

• Koyabe and Others v Minister for Home Affairs and Others (CCT

53/08) [2009] ZACC 23; 2009 (12) BCLR 1192 (CC) ; 2010 (4) SA 327

(CC) (25 August 2009) esp para 63 (88 paras)

• Kiva v Minister of Correctional Services (1453/04, 43/2006) [2006]

ZAECHC 34; [2007] 1 BLLR 86 (E); (2007) 28 ILJ 597 (27 July 2006) (43

paras)

• Judicial Service Commission and Another v Cape Bar Council and

another (818/2011) [2012] ZASCA 115; 2012 (11) BCLR 1239 (SCA);

2013 (1) SA 170 (SCA); [2013] 1 All SA 40 (SCA) (14 September 2012)

(55 paras)

Outline

• History and Purpose of the Right to Reasons in SA Admin Law

• The Right to Reasons in PAJA s 5

• Evaluating the Adequacy of Reasons Given

• Further topics relating to the right to reasons

• Remedies

• Inconsistency

• Reasons for non-PAJA administrative action

History of Right to Reasons in SA Admin Law

• The right to reasons was not part of general SA administrative law

prior to 1994

• But it was provided for in some legislative sections

• Constitutional advent of the “culture of justification” (E Mureinik)

• Increase rationality, fairness, public confidence, and legitimacy

• Section 33(2): “Everyone whose rights have been adversely affected

by administrative action has the right to be given written reasons”

Purpose(s) of the Right to Reasons

• To improve quality of decision-making by structuring discretion

• To increase fairness and public confidence by informing the person affected

of the reasons for the decision

• To enable rational and constructive criticism of decisions after the fact –

akin to monitoring and evaluation – and to enable appeal and review

• To educate the person(s) affected for future applications

• NB: There are costs as well as benefits, often termed as “administrative

efficiency” (as mentioned in section 33(3))

• Time burden

• Chilling/stifling of discretion

• Increased level/number of review applications

The Right to Reasons in PAJA s 5

• Process is a request-driven regime

• NB: a clear statement of administrative action is a mandatory element of PAJA s 3

procedural fairness

• Affected person may request reasons; once triggered, administrator must

furnish reasons within 90 days; administrator may furnish reasons without

request and may furnish reasons before 90 days

• Evidence is oral or documentary information provided to the administrator

• Reasons – an explanation for a decision/administrative action

• Findings – part of the essential background for reasons, but not themlseves

a complete explanation

• In US law, may be basic findings or ultimate findings (made by inference from basic

findings)

The Right to Reasons in PAJA s 5

• Section 5(1): Any person whose rights have been materially and adversely

affected by administrative action and who has not been given reasons for

the action may, within 90 days after the date on which that person became

aware of the action, request that the administrator concerned furnish

written reasons for the action.

• Section 5(2): the administrator “to whom the request is made must, within

90 days after receiving the request, give that person adequate reasons in

writing for the administrative action”

• Section 9(1) allows for the period of 90 days to reduced or extended by

agreement between the parties

• Who may request reasons?

• What must that person do to request reasons?

The Right to Reasons in PAJA s 5

• Who may request reasons?

• Any person ‘whose rights have been materially and adversely affected by

administrative action’

• PAJA adds element of materiality – just means significant and not trivial

• Transnet v Goodman Brothers (SCA, 2001) gave reasons where a tenderor’s right, interests,

and legitimate expectations were not affected; done in order to allow tenderer to know if the

right to lawful administrative action had been violated; also equal treatment was suggested

• Kiva v Minister of Correctional Services (similar reasoning)

• Any person ‘who has not been given reasons for the action’

• If reasons already provided are adequate, then subsequent request need not be responded

to

• If reasons provided are inadequate, then adequate reasons must be given on request

• ‘Written reasons’ suggests oral reasons cannot be adequate

• ‘Given’ – does this include not individual notice but public notification?

The Right to Reasons in PAJA s 5

• Process of requesting reasons: 90 day period

• To what degree is this firmly regulated by detailed PAJA subordinate legislation?

• 2002 Regulations on fair administrative procedures

• Includes requirement for requester to stipulate the rights adversely affected

• 2009 Draft Rules of Procedure for Judicial Review of Administrative Action (not in effect)

• Process of providing reasons: 90 day period

• 2002 Regulations (requiring acknowledgement of request)

• Conflicting decisions on whether the 90 day period may be reduced in absence of an agreement or

court order (in context of whether an application for reasons ahead of the 90 day period would be

premature) (Quinot p. 202-203 suggests that proper approach is to apply to court for order for

period to be reduced, not reasons given) (good place for a general administrative tribunal?)

• Departures from PAJA s 5: (PAJA s 2 (exemptions) and PAJA s 5(4) (departures (w/

reasons) and s 5(5) (fair but different))

• PAJA s 5(6) (providing potential for Minister to categorize some administrative action as

requiring automatic reasons)

The Right to Reasons in PAJA s 5

• Inference relevant to judicial review from the failure to provide

reasons

• Courts willing to draw an adverse inference if the administrator does not

provide reasons; National Transport Commission v Chetty’s Motor Transport

• PAJA s 5(3) codifies this and goes further, enacts a presumption that

administrative action was taken for no good reason if reasons are not

provided

• Wessels v Minister for Justice and Constitutional Development (High Court,

2010)

• Where no reasons provided for shortlisted applicant’s non-appointment, court presumes

appointment decision taken for no good reason and thus set aside

Evaluating the Adequacy of Reasons Given

• Adequacy of reasons will be relevant to the satisfaction of the s 5(1)

request and to the standing of the requester – e.g. whether the

requester has already been given reasons

• Adequacy fits the purpose(s) of the right to reasons

• So that the person affected knows why and how the decision was made

• So that the person affected can evaluate her options to appeal/re-apply

Evaluating the Adequacy of Reasons Given

• Commissioner, SAPS v Maimela (High Court, 2003): Reasons “must be informative in the

sense that they convey why the decision-maker thinks (or collectively think) that the

administrative action is justified.”

• Minister of EA & T v Phambili Fisheries (SCA, 2003) adequacy includes:

• The decision-maker’s understanding (interpretation) of the relevant law

• The decision-maker’s finding on the facts

• Particularly important where the facts are in dispute

• The decision-maker’s reasoning process

• Bare conclusions are inadequate

• Reasons must set out not only factors but also their role in the decision

• Reasons stated in clear and unambiguous language

• Usually the use of statutory language would not be adequate

• Reasons of appropriate length and level of detail, considering

• The complexity of the decision

• The time available to formulate the statement of reasons

• The nature and importance of the decision

Evaluating the Adequacy of Reasons Given

• Koyabe v Minister of Home Affairs (LHR as Amicus Curiae) (CC, 2010)

• Reasons do not have to be “specified in minute detail, nor is it necessary to

show that every relevant fact weighed in the ultimate finding”

• Kiva v Minister of Correctional Services (High Court, 2007)

• Inadequate reasons were furnished by a letter informing an applicant that he

was not promoted and a second document providing him with a list of factors

considered

• Commissioner, SAPS v Maimela

• Adequacy of reasons must be judged from the viewpoint of the requester and

“from the outset” (e.g. prospectively, not retrospectively)

• If referring to an extraneous source, should that source be (a) identified (yes) and (b)

provided (maybe)?

Evaluating the Adequacy of Reasons Given

• The case of standard form reasons (in some situations, pro forma reasons

would be sufficient; in other situations, they would be insufficient)

• Nomala v Permanent, Dept of Welfare (High Court, 2001) (the standard form reasons

provided did not inform the requester/denied applicant about what to address

specifically in an appeal or a new application)

• Ngomana v CEO, South African Social Security Agency (High Court, 2010) (considering

reasons ito Social Assistance Act, notifying refused applicant of absent or non-

supportive medical report available to the applicant was sufficient to comply with

the right to reasons)

• If there is a requirement that there be such a report, absence and that requirement should be

notified to the applicant (Quinot p 214)

• If medical report is non-supportive, how and why it is non-supportive should be explained

(Quinot p. 214)

• Millenium Waste Management (SCA, 2008)

• Reasons provided in first stage of procurement (administrative compliance) may simply be

noted absence or presence of required detail and reference to legal provisions requiring such

detail

Further topics on the Right to Reasons

• Remedies

• Maimela (a court cannot prescribe to an administrator what its reasons

should be; appropriate remedy is to review the decision)

• Alternative: since inadequate reasons are not reasons, then an order

compelling provision of reasons is competent under PAJA (Quinot at p. 216)

• Provisions allowing for such orders exist in PAJA s 8(1)(a) and in the 2009 PAJA

regulations

• Inconsistency and the provision of supplementary reasons

• De Ville (consistency required; 90 days is time enough); Currie (in the name of

efficiency, an administrator may supplement initial reasons)

Further Topic: Reasons and non-PAJA

administrative action

• Judicial Service Commission v Cape Bar Council (SCA, 2013) (deciding not to

appoint any nominees to the WC bench, leaving two posts unfilled, noted

no nominees had received a majority vote)

• Responding to the challenge that this was “no reason at all” and thus

irrational, JSC argued:

• JSC under no constitutional or statutory duty to give reasons

• JSC did give reasons (see above); and

• JSC has secret voting procedures, limiting it to above reasons

• SCA found JSC has implied Con’l duty to provide reasons; that reasons

given were inadequate; JSC could choose another non-secret procedure;

see explicit Con’l reasons required for Con Court appointments

• Relying on the principle of legality, SCA invalidated the decision as irrational

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Guide to Strategic LitigationDokument42 SeitenGuide to Strategic LitigationFilip JovovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- RTI CIC Case Law DigestDokument71 SeitenRTI CIC Case Law Digestvheejay.vkhisti1070100% (1)

- Case Management ChecklistDokument3 SeitenCase Management ChecklistYCSTBlogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Seminar Overview Problem Solving ApproachDokument7 SeitenCivil Procedure Seminar Overview Problem Solving ApproachMr FrostNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Law NCA Summary Alternate (1) ExtrasyllabusDokument70 SeitenAdmin Law NCA Summary Alternate (1) ExtrasyllabusModupe Ehinlaiye100% (3)

- Module 4 - Class NotesDokument86 SeitenModule 4 - Class NotesJennifer AshrafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. MCR Hrdi Ap: Right To InformationDokument32 SeitenDr. MCR Hrdi Ap: Right To InformationGomathiRachakondaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6.2 StudentDokument18 SeitenChapter 6.2 StudentHARRITRAAMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civ Pro - Johns - S08B - OutlineDokument15 SeitenCiv Pro - Johns - S08B - OutlineSophia VeledaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADR Slides - RVV.J'16Dokument120 SeitenADR Slides - RVV.J'16sandeepdsnluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Finaal 17 Junie 2021 PAIA Art 51 Handleiding Solidariteit - ENGDokument21 SeitenFinaal 17 Junie 2021 PAIA Art 51 Handleiding Solidariteit - ENGBNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPA exam access rights caseDokument3 SeitenCPA exam access rights casegianfranco0613100% (1)

- Civil Servants Efficiency and Descipline Rules in FGEI Qammer ShahzadDokument38 SeitenCivil Servants Efficiency and Descipline Rules in FGEI Qammer ShahzadQammer ShahzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Re Residential Tenancies - See Public Crevier) : Baker V Canada (1999)Dokument41 SeitenRe Residential Tenancies - See Public Crevier) : Baker V Canada (1999)Chamil JanithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Review Procedures and AvenuesDokument0 SeitenAdministrative Review Procedures and AvenuesHeather Kinsaul FosterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Law Checklist-2015Dokument6 SeitenAdmin Law Checklist-2015Prabdeep100% (2)

- Administrative Law Lesson 8 - Procedural Fairness NSPDokument23 SeitenAdministrative Law Lesson 8 - Procedural Fairness NSPnattiemonakali84Noch keine Bewertungen

- GC 13-04Dokument29 SeitenGC 13-04nlrbdocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stipulation Resolving Request For Comments On Proposed Order Appointing Fee ExaminerDokument12 SeitenStipulation Resolving Request For Comments On Proposed Order Appointing Fee ExaminerChapter 11 DocketsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011LHC686Dokument9 Seiten2011LHC686maryamsajjaladvocateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grave Abuse of Discretion in Delaying Case ResolutionDokument1 SeiteGrave Abuse of Discretion in Delaying Case ResolutionNiq PolidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excusable NegligenceDokument2 SeitenExcusable NegligenceStopGovt WasteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Law Study NotesDokument41 SeitenAdmin Law Study NotesHomework PingNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 - Judicial ReviewDokument14 Seiten7 - Judicial Reviewmanavmelwani100% (1)

- NCLT - Class Action SuitDokument44 SeitenNCLT - Class Action SuitAnkitTiwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9-Cca RulesDokument34 Seiten9-Cca RulesGomathiRachakondaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Rama KrishnaDokument26 SeitenSri Rama Krishnabunny4dare1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 5.2 StudentDokument26 SeitenChapter 5.2 StudentHARRITRAAMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 18 Domestic Enquiry: ObjectivesDokument10 SeitenUnit 18 Domestic Enquiry: ObjectivesgauravklsNoch keine Bewertungen

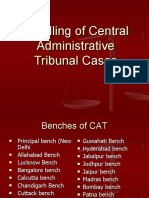

- Handling of Central Administrative Tribunal CasesDokument26 SeitenHandling of Central Administrative Tribunal Casessri vinayaga edutainersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central Administrative TribunalsDokument5 SeitenCentral Administrative TribunalsVangara HarshuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Additional - StudentDokument26 SeitenChapter 4 Additional - StudentMOHANARAJAN A L CHELVARAJANNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017-08-22 General Information - Entrance Exam For 3 November 2017Dokument10 Seiten2017-08-22 General Information - Entrance Exam For 3 November 2017MurrayNoch keine Bewertungen

- DOMESTIC INQUIRY PROCESS UNDER LABOR LAWDokument30 SeitenDOMESTIC INQUIRY PROCESS UNDER LABOR LAWTC-6 Client Requesting sideNoch keine Bewertungen

- P X - A R: ART Dministrative EviewDokument24 SeitenP X - A R: ART Dministrative EviewthejackersNoch keine Bewertungen

- J.J. Merchant Case by DR Prem LataDokument5 SeitenJ.J. Merchant Case by DR Prem LataAnonymous 8GvuZyB5VwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Law HD Notes 82Dokument75 SeitenAdministrative Law HD Notes 82miichaeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Requesting Attorney's Fees Under The Equal Access To Justice ActDokument18 SeitenRequesting Attorney's Fees Under The Equal Access To Justice ActUmesh HeendeniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 6 Overview - TaggedDokument11 SeitenWeek 6 Overview - TaggedDevan QuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- A.P. Sss Rules Feb 2015Dokument62 SeitenA.P. Sss Rules Feb 2015MuraliKrishna Naidu100% (1)

- Employment Law 1Dokument16 SeitenEmployment Law 1Elli KhaleelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LU 8 - Reasons & StandingDokument30 SeitenLU 8 - Reasons & Standingrameezvazeer129Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grievance & ProceduresDokument33 SeitenGrievance & ProceduresyogaknNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTA CasesDokument32 SeitenCTA CasesEmille LlorenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- UeDokument3 SeitenUeHerbert Shirov Tendido SecurataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Law - Right To Be HeardDokument11 SeitenAdministrative Law - Right To Be HeardRohitSingh416Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rwodzi V Municipality of Chegutu (HH 86 of 2003) 2003 ZWHHC 86 (3 June 2003)Dokument5 SeitenRwodzi V Municipality of Chegutu (HH 86 of 2003) 2003 ZWHHC 86 (3 June 2003)Panganayi JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part 3 - Representation, Practice, and Procedures: Revised For Tests Beginning May 1, 2013Dokument4 SeitenPart 3 - Representation, Practice, and Procedures: Revised For Tests Beginning May 1, 2013Sopno NonditaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CANADIAN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW MODULE 3 REVIEWDokument84 SeitenCANADIAN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW MODULE 3 REVIEWJennifer AshrafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interlocutory Applications Fact SheetDokument2 SeitenInterlocutory Applications Fact SheetAvneet KaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- (MP) V Bishop State Community College 5-30-08Dokument11 Seiten(MP) V Bishop State Community College 5-30-08E Frank CorneliusNoch keine Bewertungen

- December 09, 2013: OntarioDokument10 SeitenDecember 09, 2013: Ontarioapi-60748054Noch keine Bewertungen

- All Comm TransDokument95 SeitenAll Comm Transsimushi83% (6)

- California Notary Public Study Guide with 7 Practice Exams: 280 Practice Questions and 100+ Bonus Questions IncludedVon EverandCalifornia Notary Public Study Guide with 7 Practice Exams: 280 Practice Questions and 100+ Bonus Questions IncludedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure, Law Essentials: Governing Law for Law School and Bar Exam PrepVon EverandCivil Procedure, Law Essentials: Governing Law for Law School and Bar Exam PrepNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History and Transformation of the California Workers’ Compensation System and the Impact of Senate Bill 899 and the Current Law Senate Bill 863Von EverandThe History and Transformation of the California Workers’ Compensation System and the Impact of Senate Bill 899 and the Current Law Senate Bill 863Noch keine Bewertungen

- Key Case Law Rules for Government Contract FormationVon EverandKey Case Law Rules for Government Contract FormationNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Overview of Compulsory Strata Management Law in NSW: Michael Pobi, Pobi LawyersVon EverandAn Overview of Compulsory Strata Management Law in NSW: Michael Pobi, Pobi LawyersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journals of Regulatory Frame Work in Malawi: Book 1Von EverandJournals of Regulatory Frame Work in Malawi: Book 1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Winning Government Contracts: How Your Small Business Can Find and Secure Federal Government Contracts up to $100,000Von EverandWinning Government Contracts: How Your Small Business Can Find and Secure Federal Government Contracts up to $100,000Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Marketing Research NotesDokument102 SeitenMarketing Research Notessachin goswamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 121 Heuristics for Solving ProblemsDokument18 Seiten121 Heuristics for Solving ProblemsAlexi WiedemannNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Secular State A Response To Mohamad Amer MezianeDokument8 SeitenOn The Secular State A Response To Mohamad Amer MezianeaneesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argumentative EssayDokument4 SeitenArgumentative Essayhailglee1925Noch keine Bewertungen

- Programación English Alive 3 - 4 ESO EnglishDokument271 SeitenProgramación English Alive 3 - 4 ESO EnglishBea Triz0% (1)

- Book-1 Short Stories 1st YearDokument73 SeitenBook-1 Short Stories 1st YearMuhammad Yasin GillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workbook 2Dokument11 SeitenWorkbook 2arupsmartlearnwebtv0% (1)

- GMATH Module 1Dokument2 SeitenGMATH Module 1michaela mascarinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theological Ethics and Business Ethics: Richard T. de GeorgeDokument12 SeitenTheological Ethics and Business Ethics: Richard T. de GeorgeJohn ManciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Organizational Practices Can Compensate For Individual ShortcomingsDokument19 SeitenHow Organizational Practices Can Compensate For Individual ShortcomingsAngelo TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pinoy Math PDFDokument152 SeitenPinoy Math PDFsky9213Noch keine Bewertungen

- Trends q3 Module 3Dokument31 SeitenTrends q3 Module 3Peachy Cleo SuarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment # 2: Total Marks: 50 Submission Due DateDokument6 SeitenAssignment # 2: Total Marks: 50 Submission Due DateRaahim KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agree and DisagreeDokument2 SeitenAgree and DisagreePhương ChiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dao Companion To Classical Confucian PhilosophyDokument402 SeitenDao Companion To Classical Confucian Philosophymanidhara100% (1)

- Liberal Values LDDokument165 SeitenLiberal Values LDAndrew ChuangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whatever Happened To EmbodimentDokument13 SeitenWhatever Happened To EmbodimentPARTRICANoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Global Perspectives 0457/11 May/June 2022Dokument20 SeitenCambridge IGCSE™: Global Perspectives 0457/11 May/June 2022Akoh Nixon AkohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thought and Action in Aristotle AnscombeDokument12 SeitenThought and Action in Aristotle AnscombeJorge Fer García100% (1)

- Past Shock Jack Barranger Chapter 1 Part 1Dokument8 SeitenPast Shock Jack Barranger Chapter 1 Part 1Harshita ShivanagowdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Twilight of The IdolsDokument102 SeitenTwilight of The Idolsantinomy100% (1)

- Rousseau - ''Letter To D'Alembert'' Politics & The Arts (Allan Bloom)Dokument156 SeitenRousseau - ''Letter To D'Alembert'' Politics & The Arts (Allan Bloom)Giordano BrunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Do Bold Face Questions TestDokument4 SeitenWhat Do Bold Face Questions TestfrancescoabcNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Given Graph Elucidates Information About Access To Internet Enjoyed by Domestic Users in UrbanDokument47 SeitenThe Given Graph Elucidates Information About Access To Internet Enjoyed by Domestic Users in UrbanVân YếnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quarter 1st Con (Not Mine)Dokument6 SeitenQuarter 1st Con (Not Mine)Bautista Ayesha Mikhaila (A-kun)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Persuading Snow WhiteDokument7 SeitenPersuading Snow WhiteCristina Georgiana RosuNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHATZIDAKIS - & - LEE - 2013 - Anti-Consumption As The Study of Reasons AgainstDokument14 SeitenCHATZIDAKIS - & - LEE - 2013 - Anti-Consumption As The Study of Reasons AgainstEstudanteSaxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 3 Lesson 1 The Human ActsDokument35 SeitenModule 3 Lesson 1 The Human Actszzrot167% (3)

- Loyalty, Love, and Relationships (Grade 9)Dokument38 SeitenLoyalty, Love, and Relationships (Grade 9)Ronmar Manalo ParadejasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spiritual Field of Islamic CivilizationDokument8 SeitenSpiritual Field of Islamic CivilizationMajid YassineNoch keine Bewertungen