Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Differences in Perceptions of Training by Coaches and Athletes

Hochgeladen von

Pootrain ConductorOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Differences in Perceptions of Training by Coaches and Athletes

Hochgeladen von

Pootrain ConductorCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Differences in perceptions of training by coaches

and athletes

Carl Foster (PhD)

Kara M Heimann (MS)

Phillip L Esten (PhD)

Glen Brice (PhD)

John P Porcari (PhD)

Departm ent o f Exercise and Sport Science, University o f W isconsin-La Crosse, La Crosse, W isconsin, USA

training LOAD (91 ± 43 vs 128 ± 92), despite similar

Abstract training duration (50 ± 16. vs 49 ± 21 min). For training

Objective. Despite careful planning by professionally sessions intended by the coaches to be of intermediate

educated coaches, overtraining syndrome remains a intensity, there were no differences between the coach

common problem among competitive athletes. In this es’ and athletes’ training RPE (3.4 ± 0.7 vs 3.4 ± 1.4),

study we compare the training plan designed by coach training LOAD (196 ± 66 vs 210 ± 149), or training dura

es with that executed by athletes to test the hypothesis tion (58 ± 16 vs 59 ± 22 minutes). For training sessions

that a potential cause of overtraining syndrome may be intended by the coaches to be of high intensity, the ath

unrecognised errors in the execution of the training pro letes trained at a significantly lower RPE (7.1 ± 1.2 vs

gramme by athletes. 6.2 ± 2.5) and training LOAD (486 ± 194 vs 422 ± 256),

Design. Volunteer competitive runners (N = 15) record despite no differences in training duration (67 ± 20 vs

ed their training over a 5-week period using the session 66 ± 26 minutes).

rating of perceived exertion (RPE) method of training Conclusions. We conclude that there are significant

monitoring, which multiplies a global rating of exercise differences between the training plan as designed by the

intensity using the category ratio RPE scale by the dura coaches and executed by the athletes. These differ

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2012.)

tion of training to create a calculated training load. ences are of a configuration and magnitude such that

Independently, their coaches also recorded what they they may be a reasonable cause of the high incidence of

intended the athletes to do in training. maladaptations to training in athletes.

Setting. University-based athletics team.

Main outcome measure. Correspondence between

coaches’ and athletes’ rating of the coaches’ training

programme.

Introduction

Results. The correlation between coaches’ and ath

The ability of athletes to adapt to training and improve per

letes’ training LOAD (r = 0.72), training intensity (r = 0.75),

formance is one of the cornerstones of contemporary sports

and training duration (r= 0.65) was modestly strong. For

medicine. We469 10 and others23514 171820 have demonstrated a

training sessions intended by the coaches to be low

quantitative relationship between the magnitude of the train

intensity, the athletes trained at a significantly (P < 0.05)

ing load and subsequent performance. However, despite

higher RPE than intended (mean ± standard deviation)

this adaptability, there is a relatively high incidence of unde

(1.8 ± 0.5 vs 2.4 ± 1.4) and had a significantly higher

sired outcomes from heavy athletic training. These unde

sired outcomes are often summarised under the broad

category of overtraining syndrome (OTS).8151621 However, a

failure to train with sufficient intensity or duration to provoke

maximal adaptive responses might be just as likely to lead to

CORRESPONDENCE: a less than desired response to training.259 "-14-17-1820 Despite

the generally good educational level of contemporary coach

Dr Carl Foster es and the effort they invest in designing training pro

Department of Exercise and Sport Science grammes, the incidence of OTS remains quite high.81516

132 Mitchell Hall Similarly, one only has to listen to the comments of coaches

University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and athletes following unsuccessful competitions to recog

La Crosse, Wl 54601 nise that inadequate training is frequently believed to be

Tel: 091-608 785 8687 responsible for many competitive failures. We have previ

Fax: 091-608 785 8172 ously suggested, on the basis of empirical observations, that

E-mail: foster.carl@uwlax.edu one potential cause of this high incidence of negative train

SPORTS MEDICINE JUNE 2001 3

ing outcomes may be a lack of correspondence between the LOAD, and which is conceptually (although not numerically)

training programme as designed by coaches and as execut equivalent to the TRIMP score derived from heart rate mon

ed by athletes." The purpose of this study is to test this itoring.13 Independently, prior to the training session each

hypothesis. coach rated his/her intention for the intensity (session RPE)

and duration of each training session using the same

approach. Not all athletes had exactly the same training pre

Methods scription as the needs for different event specialties and the

training plans among the three coaches varied somewhat.

The subjects for this study were competitive runners from a However, analysis was based on the responses of a given

club level university athletics team, a relatively modest com athlete to the training programme designed for that athlete

petitive level within the university athletics structure in the by his/her coach. We did not investigate whether the coach

USA. There were six male and nine female subjects. All es modified their intentions for subsequent training sessions

were middle- and long-distance runners, and their seasonal based on observations made within any particular training

best performance time in their own best distance was (mean session. However, on the basis of each coach having to

± standard deviation (SD)) 112.6 ± 3.5% relative to the dis

supervise a large number of athletes and their general pat

tance and gender-specific world record time. All subjects

tern of not being present during recovery training sessions,

were volunteers and provided informed consent prior to par

we have made the assumption that the coaches’ plans were

ticipation. The protocol had been approved by the University

relatively constant.

Human Subjects Committee. The group of athletes was

coached by three different coaches, although each athlete

had only one coach.

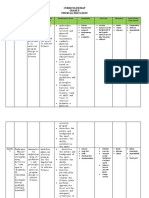

TABLE I. Session rating of perceived exertion

Training was monitored over a 5-week period, from the Rating Verbal anchor

middle of the spring athletics season through preparation for

0 Rest

the early conference championships. The training prescrip

1 Very easy

tion was presented to the athlete in conventional terms (e.g.

2 Easy

distance to be run and/or number and distance of intervals to

be completed). Descriptive modifiers, usually presented as 3 Moderate

a percentage of racing pace, were often added, particularly 4 Sort of hard

during high-intensity training sessions. Training was quanti 5 Hard

tated using the session rating of perceived exertion (RPE) 6

technique.fMM0-13 7 Very hard

This method is a modification of the training impulse 8 Very, very hard

(TRIMPS) method developed by Banister et al.,s'7 which is a 9 Nearly maximal

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2012.)

numeric term representing the product of training intensity 10 Maximal

and training duration, and which is used in various forms by

a number of investigators.2318 Our method modifies the use

of the RPE scale, by asking the athlete to rate the global per

ceived intensity of the entire training session, rather than rat Statistical comparisons of the coaches’ and athletes’

ing the momentary perception of effort. We have previously training were made using correlation statistics. Additionally,

validated the session RPE method by demonstrating that it the training sessions were divided into those intended by the

provides reasonable estimates of the intensity of an entire coaches to be fairly easy (RPE < 3), intermediate (RPE 3-5),

training session compared with methods which monitor train and fairly hard (RPE > 5) and the coaches' and athletes’ per

ing by means of heart rate and blood lactate67 and that it ceptions of intensity (e.g. session RPE), duration, and train

behaves reliably and consistently under a variety of types of ing LOAD (RPE x duration) were compared using two-way

training.13 Approximately 30 minutes after the conclusion of analysis of variance (ANOVA) (coaches vs athletes by inten

each training bout, athletes were asked to rate the overall sity level). Alpha was set at 0.05.

intensity of the training session using the category ratio (0-

10) RPE scale, and to record the duration of training. As in

previous studies, we modified the verbal anchors of the RPE Results

scale slightly (Table I). As in our other studies6-810'13 the

instructions given to the athletes and coaches were quite In general, the serial variations in training LOAD were com

simple: ‘if a friend who did not understand the specific train parable between coaches and athletes (Fig. 1). As the

ing expressions of athletics were to ask you how hard your observation period progressed, the training LOAD

training session was, how would you reply?' th e duration of decreased secondary to resting for the more important late

the training session included all training activities from the season competitions. There was a moderately strong corre

beginning of the warm-up period to the end of the cool down. lation between coaches’ and athletes’ estimates of training

The rationale for rating the intensity (RPE) of the training intensity (r - 0.75), training duration (r = 0.65) and training

session 30 minutes after the conclusion of training was to LOAD (r = 0.74) (Fig. 2).When the various categories of the

prevent particularly hard or easy elements late in the training training session were compared, there were significant

session from dominating the athletes’ perception of the train (P < 0.05) and relevant differences between the coaches’ and

ing session. Multiplication of the session RPE by the dura athletes’ ratings (Figs 3-5). For sessions intended by the

tion yielded a dimensionless term which we refer to as coaches to be relatively easy, the session RPE experienced

4 SPORTS MEDICINE JUNE 2001

10

□ Coaches

9

□ Athletes

?ff) 8

l ii

C

.2 3

Coaches’ LOAD 0

Easy

Fig. 1. R elationship betw een individual training sessions as

Fig. 3. Com parison o f the session R PE (e.g. training intensity)

designed b y the coaches and as experienced by the athletes.

experienced b y the athletes in relation to the m ean coach es’

Note particularly, the large num ber o f significant training ses

intentions for easy (R PE < 3), m oderate (R PE 3-5) and hard

sions perfo rm ed b y the athletes on days intended b y the

(RPE > 5) training sessions. There w ere significant differences

coaches to be com plete rest days (e.g. LOAD = 0), and the

between the coach es’ intentions an d a th le te s ’ experiences dur

occasional lo w training loads accom plished b y athletes on

ing both easy and h ard training sessions.

days intended b y the coach to be relatively hard.

□ Coaches

□ Athletes

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2012.)

Easy

Fig. 4. Com parison o f training session duration experienced

by the athletes in relation to the c o a c h es ’ intentions. There

w ere no sign ificant differences.

Fig. 2. Serial changes in average training LOAD as designed by

the coaches a n d as experienced b y the athletes. Notice the

o verall parallelism betw een the training LOADs, and the ten

dency fo r the athletes to have greater training LOADs during a

p erio d o f progressive reduction in training b y the coaches. □ Coaches

O 600 □ Athletes

by the athletes was significantly greater (mean + SD) (1.8 ± 0.5

vs 2.4 ± 1.4), and the training LOAD was significantly greater

(91 ± 13 vs 128 ± 72) than intended by the coaches. There

Q

were no significant differences in training duration (50 ± 16 <

O

vs 49 ± 21 minutes) between coaches and athletes. For ses

sions intended by the coaches to be of intermediate intensi

2 100

ty, there were no significant differences between coaches h-

and athletes for training intensity (3.4 ± 0.7 vs 3.4 ± 1.7),

Easy Moderate

training duration (58 ± 16 vs 59 ± 22 minutes), or training

LOAD (196 ± 66 vs 210 ± 149). For sessions intended by the

coaches to be relatively hard, the session RPE experienced Fig. 5. Com parison o f the com puted training LOA D (session

R PE * duration) experienced b y the athletes in relation to the

by the athletes (7.1 ± 1.2 vs 6.2 ± 2.5) and training LOAD c oach es’ intentions fo r easy, m oderate and h ard training ses

(486 ± 194 vs 422 + 256) were significantly less than intend sions. There were significant differences betw een the coach

ed by the coaches, although there were no significant differ e s ’ intentions and ath letes’ experiences during both easy and

ences in training duration (67 ± 20 vs 66 ± 26 minutes). hard training sessions.

SPORTS MEDICINE JUNE 2001 5

Discussion for testing the effectiveness and efficacy of systematically

designed training programmes.

The results of this study demonstrate that there are signifi There are alternative ways to interpret our observations.

cant differences in the training programme as designed by It may be that the observed differences between coaches

professional coaches and as executed by collegiate athletes. and athletes are not meaningful. Certainly the absolute

While no athlete in this study developed OTS, the results intensity experienced by the athletes on the coach-designat

demonstrate the presence of a plausible scenario whereby ed recovery (e.g. low-intensity and short-duration) days was

athletes might develop OTS. It is well accepted, based on still quite low (session RPE = 2.4 ± 1.4). One might argue,

both human781216 and animal1 models that the development particularly in light of the observation that no athlete in the

of OTS is primarily linked to failure of recovery periods, present study demonstrated any suggestion of OTS, that the

which may be related to a persistent inflammatory response differences between coaches and athletes are moot.

linked to too brief recovery periods between periods of Regardless, we interpret our results as suggesting a plausi

stress.21 Beyond the numerically greater intensity experi ble and highly likely scenario whereby athletes could unwit

enced by the athletes on days designed to be easy, it was tingly create conditions favourable for the development of

noted that several athletes ran significant training sessions OTS. Certainly, the experience of coaches, athletes and the

even on days intended by the coaches to contain little or no support personnel associated with them is that undesired

training. One athlete routinely completed 90-minute training training outcomes usually occur when recovery days are

sessions on days that the coach intended for complete rest missed, for whatever reason. Further, the too hard training

(Fig. 1). The data also demonstrate a plausible scenario on recovery days is paired with too easy training on days that

whereby the training pattern observed in this study might the coach designated as high-intensity training. That this

contribute to suboptimal performance. It is likely that the per pairing is consistent with a commonly recognised training

formance of athletes is enhanced primarily as a response to error (too hard on the easy days, too easy on the hard days)11

severe (e.g. high-intensity or long-duration) training ses provides a further commonsense confirmation of the mean

sions.51117 That the athletes tended to undertrain on days ingfulness of the present results.

that the coach intended to be quite difficult may be equally

important as a potential cause of suboptimal performance.

They are consistent with the concept that a common training

Conclusions

mistake is the tendency for training load to regress to the

mean, rather than remaining strongly polar (hard days and In summary, our study results suggest that although the

easy days). Whether this represents a failure of the coach training programme as designed by professional coaches is

es to communicate with their athletes or some other factor generally well executed by competitive athletes, there was

remains to be determined. Certainly the way the training evidence of meaningful differences in the direction of the ath

sessions were communicated was not in the jargon used in letes training harder than intended on coach-designated

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2012.)

our monitoring method, but in terms of distance to be run and recovery days and easier than intended on coach-designa-

the pace desired. The larger implication within the present ted hard days. Although in the present results there was no

results is that when the highly detailed training plans of ath evidence of OTS within a short observational period, we

letes are translated into a simpler method of expression, believe that these results demonstrate a plausible and likely

then athletes apparently do not experience what the coach scenario that can account for the high incidence of OTS in

intended. competitive athletes training under the supervision of profes

sionally trained coaches.

To our knowledge, these are the first results systemati

cally and quantitatively comparing the training programmes

of coaches and athletes. Other studies have described the R eferences

training undertaken by athletes,37910” 171820 have compared 1. Bruin G, Kuipers H, Keizer HA, van der Vusse GJ. Adaptation and over

training in horses subjected to increasing training loads. J Appl Physiol

the interplay between fitness and fatigue with variations in 1994; 76: 1908-13.

training,25121718 and have attempted to relate the details of 2. Busso T, Chandau R, Lacour J. Fatigue and fitness modeled from the

training to the incidence of OTS.78 However, no study has effects of training on performance. Eur J Appl Physiol 1994; 69: 50-4.

yet compared how well athletes execute the training plans 3. Busso T, Denis C, Bonnefoy R, Geyssant A, Lacour J. Modeling of the

designed by coaches. Given the nature of our results, the adaptations to physical training by using a recursive least squares algo

rithm. J Appl Physiol 1997; 82: 1685-93.

present study needs replication in higher level athletes and

4. Daniels JT, Yarbrough RA, Foster C. Changes in V 0 2max and running per

in athletes who subsequently develop OTS. The subjects in formance with training. Eur J Appl Physiol 1991; 39: 249-54.

this study were relatively low level athletes, who were stud 5. Fitz-Clarke JR, Morton RH, Banister EW. Optimizing athletic performance

ied relatively late in the training year during a period of time by influence curves. J Appl Physiol 1991; 71:1151-8.

during which the overall training load was being decreased 6. Foster C, Hector L, Welsh R, Schrager M, Green MA, Snyder AC. Effects

of specific versus cross training on running performance. Eur J Appl

as a normal part of the seasonal plan. Both of these factors

Physiol 1995, 70: 367-72.

could potentially have reduced the likelihood of maladapta-

7. Foster C. Monitoring training in athletes with reference to overtraining

tions to training. Further, although we have made the syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997; 30:1164-8.

assumption that the training programmes designed by the 8. Foster C, Lehmann M. Overtraining syndrome. In: Guten GN, ed.

coaches were correct, the fact remains that despite serious Running Injuries. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997; 173-88.

efforts to develop quantitative models of coaching,19 this 9. Foster C, Daniels JT, Yarbrough RA. Physiological correlates of marathon

running performance. Aust J Sports Med 1977; 9:58-61.

activity remains as much art as science. At the least, the

10. Foster C, Daines E, Hector L, Snyder AC, Welsh R. Athletic performance

results of the present study demonstrate a viable technique in relation to training load. Wis Med J 1996; 95: 370-4.

6 SPORTS MEDICINE JUNE 2001

11. Foster C, Daniels JT, Seiler S. Perspectives on correct approaches to 16. Lehmann M, Foster C, Keul J. Overtraining in endurance sports: a brief

training. In: Lehmann M, Foster C, Gastmann U, Keizer H, Steinacker J, review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993; 25: 854-62.

eds. Overload, Performance Incompetence and Regeneration in Sport. 17. Morton RH, Fitz-Clarke JR, Banister EW. Modeling human performance

New York: Plenum Press, 1999: 27-41. in running. J Appl Physiol 1990; 69:1171-7.

12. Foster C, Snyder AC, Welsh R. Monitoring of training, warm up and per- • 18. Mujika I, Busso T, Lacoste L, Barale F, Geyssant A, Chatard JC. Modeled

formance in athletes. In: Lehmann M, Foster C, Gastmann U, Keizer H, response to training and taper in competitive swimmers. Med Sci Sports

Steinacker J, eds. Overload, Performance Incompetence and Exerc 1996; 28: 251-8.

Regeneration in Sport. New York: Plenum Press, 1999: 43-51.

19. Rowbottom D Periodization of training. In: Garret WE, Kirkendall DT, eds.

13. Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J, Gottschall L, Hrovatin LA, Parker S, Exercise and S poil Science. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins,

Doleshal P, Dodge C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. 2000: 499-512.

Journal o f Strength and Conditioning Research (in press).

20. Slovic P. Empirical study of training and performance in the marathon.

14. Hagan RD, Smith MG, Gettman LR. Marathon performance in relation to Res Quart 1977; 48: 769-77.

maximal aerobic power and training indices. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1981;

13: 185-9. 21. Smith LL. Cytokine hypothesis of overtraining: a physiological adaptation

to excessive stress? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000; 32: 317-24.

15. Kuipers H, Keizer HA. Overtraining in elite athletes. Sports Med 1988,

6: 79-92.

Sports Medicine in Clinical Decision Making

Primary Care in Sports Medicine

Rob Johnson Dinesh Kumbhare and John Basmajian

Sports Medicine in Primary Care provides an easy-to-read refer As more therapies and technologies have developed in the area of

ence for the primary care physician who treats common musculo sports medicine, the need has grown for scientific evidence and

skeletal and sports medicine problems. Written by expert clinicians critical appraisal of the effectiveness of specific treatment meth

that practice both primary care and sports medicine, this resource ods. This informative text fills this gap by offering discussions on

contains invaluable information for the non-sports medicine trained evidence-based sports rehabilitation through a comprehensive and

physician. contemporary examination of the subject. It is divided into the fol

Features lowing sections:

■ Includes only those topics that are most commonly encoun Basic Considerations which includes cardiovascular considera

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2012.)

tered in the primary care office. tions, nutritional strategies, dehydration, inflammation, and psy

■ The format for musculoskeletal and medical problems is the chological, sociological and physiological factors in sport

same from chapter to chapter, helping readers to easily find a Therapeutics which covers physiotherapy, chiropractic and al

specific topic or answer a specific question. ternative treatment approaches

■ Summary sites, illustrations, and decision protocols make criti Special Considerations which covers pregnancy, the mature ath

cal information easy-to-find. lete and the paediatric athlete

■ Excellent chapter on preparticipation evaluation is included. Neuromuscular Considerations which includes epilepsy, concus

■ Presents return to activity guidelines. sion, neuropsychology and neuromuscular conditions

Contents: 1. The Essential Points of the Musculoskeletal Exam: Regional Considerations which covers the shoulder, hand and

The Focused Injury History, the Focused Musculoskeletal Exam 2. wrist, lower back, hip and knee, and the ankle.

Preparticipation Evaluation, Youth and Adolescent: History, Youth Features

and Adolescent: Physical Exam, Adult, 3. The Exercise Prescrip ■ The focus on evidence-based practice gives practitioners a

tion: Youth and Adolescent, Adult, 4. Principles of Training 5. Ad firm basis for decision making.

vising the Athlete on Nutrition, 6. Office Based Rehabilitation, 7. ■ Comprehensively examines clinical decision making in all fac

Return to Play, 8. The Use of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs ets of sports medicine

and Analgesics, 9. Office Evaluation of Minimal Brain Injury, 10. ■ Covers special topics such as Neurological Issues, Arthritis,

Neck and Cervical Spine Injury, 11. The Upper Extremity, 12. Sports Pregnancy and Paediatrics, which are not typically addressed by

Injuries to the Lower Extremity, 13. Back Injuries in Athletes, 14. sports medicine texts

Chest Injury, 15. Gastrointestinal Problems and Abdominal Trauma ■ The chapter on the aging athlete reflects the current trend

in Sports, 16. Genitourinary Problems, 17. Special Issues of the toward athletic activity throughout the lifespan

Young and Adolescent Athlete 18. Special Issues of the Woman ■ Applies many of the authors’ principles on decision making in

Athlete, 19. The Mature Athlete 20. Risk of Exercise, 21. The Ath rehabilitation to sports medicine.

lete with Medical Problems, The Hypersensitive Athlete, The Asth July 2000, hardback, 432 pp, 55 illus., CL, R499

matic/Allergic Athlete, Caring for the Diabetic Athlete, The Athlete

with Heart Disease, The Athlete with Chronic Obstructive Pulmo

nary Disease, Seizure Disorders and Athletes, The Role of Exer ORDERS

cise and Athletes in Anxiety and Depression, The Athlete with The South African Medical Association, Private Bag X1,

Infectious Disease, 22. Injection Techniques. Pinelands 7430. Tel Felicity on (021) 530-6527, Fax (021)

Sept 2000, hardback, 384 pp, 108 illus., WBS, R550 531-4126. E-mail: fpalm@samedical.org Prepayment

required but not actioned until order despatched.

Please allow 3-4 weeks for delivery if no local stock.

SPORTS MEDICINE JUNE 2001 7

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Ebook - Funnel - Self Defense - The Fundamental Concepts To Master Before Any Technique Ebook - VOLUME 1.Dokument49 SeitenEbook - Funnel - Self Defense - The Fundamental Concepts To Master Before Any Technique Ebook - VOLUME 1.Jeet Kune DoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Periodization of Training For Team Sports Athletes.9Dokument11 SeitenPeriodization of Training For Team Sports Athletes.9Ian ZarceroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Velocity-Based Training From Theory To ApplicationDokument19 SeitenVelocity-Based Training From Theory To ApplicationPabloAñonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1bachelor of Sports Coaching Strength and ConditioningDokument2 Seiten1bachelor of Sports Coaching Strength and Conditioningpc socialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Periodization of Training For Team Sports Athletes.9Dokument11 SeitenPeriodization of Training For Team Sports Athletes.9Carlos Martín De Rosas100% (1)

- Motivation in Sports Psychology: The Motivational Dynamics of SportDokument11 SeitenMotivation in Sports Psychology: The Motivational Dynamics of SportRozlee MianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Build Your Opening RepertoireDokument3 SeitenBuild Your Opening RepertoireMaestro JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bridging The Gap From Rehab To Performance Sue FalsoneDokument297 SeitenBridging The Gap From Rehab To Performance Sue FalsoneÁngel PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- ARTIGO CLASSIFICAÇÃO NIVEL DE TREINAMENTO - Santos-Junior Et Al., 2021 Classification - and - Determination - Model - (FINAL)Dokument10 SeitenARTIGO CLASSIFICAÇÃO NIVEL DE TREINAMENTO - Santos-Junior Et Al., 2021 Classification - and - Determination - Model - (FINAL)Gordo FakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiff City Technical ProgrammeDokument31 SeitenCardiff City Technical ProgrammeThyago MarcolinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electronic Health Record Training in Undergraduate.10Dokument7 SeitenElectronic Health Record Training in Undergraduate.10Yasmeen ShamsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essentials Strength Training Conditioning National Strength and Conditioning Association Third Edition PDF Free 1 656 10Dokument1 SeiteEssentials Strength Training Conditioning National Strength and Conditioning Association Third Edition PDF Free 1 656 10LR SantanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading The Play in Team SportsDokument3 SeitenReading The Play in Team Sportsapi-298014898Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jospt 1Dokument3 SeitenJospt 1Ian PeroniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive Training For Agility: The Integration Between Perception and ActionDokument8 SeitenCognitive Training For Agility: The Integration Between Perception and ActionNICOLÁS ANDRÉS AYELEF PARRAGUEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- "The Effect of Dynamics Balance Exercises On Some Kinematics Variables and Jump Shoot Accuracy For Young Basketball PlayersDokument18 Seiten"The Effect of Dynamics Balance Exercises On Some Kinematics Variables and Jump Shoot Accuracy For Young Basketball PlayersisnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brockport ch1Dokument6 SeitenBrockport ch1Abhimanyu SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- JSHR2012 PDFDokument11 SeitenJSHR2012 PDFNeil KhayechNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To The Brockport Physical Fitness Technical ManualDokument10 SeitenIntroduction To The Brockport Physical Fitness Technical ManualRamadhani PutraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laboratory Manual For Strength TrainingDokument208 SeitenLaboratory Manual For Strength Trainingbigchampion997Noch keine Bewertungen

- PREFIT MANUAL - Assessing FITness in PREschoolers - 14thsept2017Dokument34 SeitenPREFIT MANUAL - Assessing FITness in PREschoolers - 14thsept2017Natalia GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level-1 Between Batter and Bowler in CricketDokument5 SeitenAnalysis of Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level-1 Between Batter and Bowler in CricketFarjana Boby100% (2)

- Med Sport Pract 2020 Critical CommentaryDokument38 SeitenMed Sport Pract 2020 Critical Commentaryleal thiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training in Sports (Chapter 10)Dokument15 SeitenTraining in Sports (Chapter 10)Ankit KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2002 Heath-Carter ManualDokument25 Seiten2002 Heath-Carter ManualSofia142Noch keine Bewertungen

- Suchomel 2021Dokument16 SeitenSuchomel 2021Nicolás Muñoz ValenzuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To The "Research Tools": Tools For Collecting, Writing, Publishing, and Disseminating Your ResearchDokument40 SeitenIntroduction To The "Research Tools": Tools For Collecting, Writing, Publishing, and Disseminating Your ResearchNader Ale EbrahimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Field-Based Health-Related Physical Fitness Tests in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic ReviewDokument10 SeitenField-Based Health-Related Physical Fitness Tests in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic ReviewAyamKalkun BandungNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 - W-IE-133 Introduction To ErgonomicsDokument28 Seiten2 - W-IE-133 Introduction To ErgonomicsLahm Nguy100% (1)

- (BAL) What Is A Balance BoardDokument2 Seiten(BAL) What Is A Balance Boardapi-3695814Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Analysis of Motor Fitness Components Among Bogura and Khulna District Women Cricket PlayersDokument5 SeitenA Comparative Analysis of Motor Fitness Components Among Bogura and Khulna District Women Cricket PlayersInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (3)

- Best Foot Forward: Optimum PerformanceDokument6 SeitenBest Foot Forward: Optimum PerformanceVicente Ignacio Ormazábal MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fitness Protocols For Age 18-65 Years v1 (English)Dokument41 SeitenFitness Protocols For Age 18-65 Years v1 (English)Buddho BuddhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A New Approach To Monitoring Exercise Training.19Dokument7 SeitenA New Approach To Monitoring Exercise Training.19ravan aramamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carga Interna Desempenho em Ciências DoDokument5 SeitenCarga Interna Desempenho em Ciências DoWallace GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training Practices and Ergogenic Aids Used by Male.20Dokument9 SeitenTraining Practices and Ergogenic Aids Used by Male.20Gabriel BarrosNoch keine Bewertungen

- A New Approach To Monitoring Exercise TrainingDokument7 SeitenA New Approach To Monitoring Exercise TrainingDanilo Barreto SouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Periodization of Training For Team Sports Athletes.9Dokument11 SeitenPeriodization of Training For Team Sports Athletes.9burak soysalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impellizzeri Rampinini Marcora 2005Dokument11 SeitenImpellizzeri Rampinini Marcora 2005MiguelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quantifying Workloads in Resistance Training: A Brief ReviewDokument11 SeitenQuantifying Workloads in Resistance Training: A Brief ReviewDanielBCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quantifying Workloads in Resistance TrainingDokument11 SeitenQuantifying Workloads in Resistance TrainingAndre LuísNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijspp 7 2 161Dokument9 SeitenIjspp 7 2 161Iyappan SubramaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Total Score of Athleticism Holistic Athlete Profiling To Enhance Decision-MakingDokument11 SeitenTotal Score of Athleticism Holistic Athlete Profiling To Enhance Decision-MakingPabloAñonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Velocity Based Training From Theory To.99257Dokument19 SeitenVelocity Based Training From Theory To.99257Carles PeiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- GPS and Injury Prevention in Professional Soccer.9 PDFDokument8 SeitenGPS and Injury Prevention in Professional Soccer.9 PDFInês AntunesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2022 - Quantifying Crossfit Potencial SolutionDokument16 Seiten2022 - Quantifying Crossfit Potencial SolutionAlexandra MalheiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9c20 PDFDokument6 Seiten9c20 PDFBlake WillisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defreitas 2010Dokument7 SeitenDefreitas 2010Fabiano LacerdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposal of A Global Training Load Measure PredictDokument8 SeitenProposal of A Global Training Load Measure PredictLéo TavaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 136-Article Text-1020-1-10-20220916Dokument10 Seiten136-Article Text-1020-1-10-20220916Répási RichárdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strength and Conditioning For FootballDokument21 SeitenStrength and Conditioning For Footballbryce crawfordNoch keine Bewertungen

- A New Approach To Monitoring Exercise TrainingDokument7 SeitenA New Approach To Monitoring Exercise TrainingShinukiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise Nonresponders Genetic Curse, Poor.1Dokument1 SeiteExercise Nonresponders Genetic Curse, Poor.1Hans DonayreNoch keine Bewertungen

- A New Approach To Monitoring Resistance Training: Keywords: Exercise Intensity Perceived Exertion PeriodizationDokument6 SeitenA New Approach To Monitoring Resistance Training: Keywords: Exercise Intensity Perceived Exertion PeriodizationDanielBCNoch keine Bewertungen

- TrainingPeriodizationofProfessionalAustralianFootballPlayers Moreiraetal IJSPP July 2015Dokument7 SeitenTrainingPeriodizationofProfessionalAustralianFootballPlayers Moreiraetal IJSPP July 2015Adel KhalidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Map Grade 8 Physical Education: T (N .) M U T C C S P S C S A A R I C V Quarter 1Dokument4 SeitenCurriculum Map Grade 8 Physical Education: T (N .) M U T C C S P S C S A A R I C V Quarter 1joan nini100% (1)

- Douglas 2018Dokument12 SeitenDouglas 2018GabrielDosAnjosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Education Physical Fitness Test Manual: SD0-Zamboanga CityDokument4 SeitenDepartment of Education Physical Fitness Test Manual: SD0-Zamboanga CityMarlyn Rico - TugahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCJ D 18 00132Dokument13 SeitenSCJ D 18 00132api-314027895Noch keine Bewertungen

- 10.1519 1533-4287 (2003) 017 0734 Iotpoi 2.0Dokument5 Seiten10.1519 1533-4287 (2003) 017 0734 Iotpoi 2.0Stefan KovačevićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer of Training How Specific Should We Be .8Dokument13 SeitenTransfer of Training How Specific Should We Be .8Juan LamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Periodisation For Team SportsDokument12 SeitenPeriodisation For Team SportssimosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Examining The External Training Load of An English.8Dokument9 SeitenExamining The External Training Load of An English.8Ádám GusztafikNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of Training Volume On The PeDokument9 SeitenThe Effects of Training Volume On The PeRamsis SphinxNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11-17-15 Corporate Board Foundation Trustee Combined Meeting MinutesDokument2 Seiten11-17-15 Corporate Board Foundation Trustee Combined Meeting MinutesBrendaBrowningNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Manchester United 4 V 4 Pilot Scheme For U 9s - Part IIDokument4 SeitenThe Manchester United 4 V 4 Pilot Scheme For U 9s - Part IIfootymagzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Powerpoint (Student Copy)Dokument31 SeitenChapter 1 Powerpoint (Student Copy)api-287615830Noch keine Bewertungen

- SATAPHULDokument7 SeitenSATAPHULsataphulsahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reaction Paper (Envi)Dokument1 SeiteReaction Paper (Envi)majemafaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Childhood and Early Career: David Villa Sánchez (Dokument14 SeitenChildhood and Early Career: David Villa Sánchez (arvin_89Noch keine Bewertungen

- WPC ResumeDokument3 SeitenWPC Resumewpc5008Noch keine Bewertungen

- Double TightxDokument1 SeiteDouble TightxloveleeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal Ingris Kelas XDokument3 SeitenSoal Ingris Kelas XPLORENTINA SHERLYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Test 5Dokument6 SeitenPractice Test 5Heba ElmeniawyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volleyball Report CardDokument1 SeiteVolleyball Report Cardapi-386425687Noch keine Bewertungen

- African Violets at MCCC: Annual Pennington Day NearsDokument16 SeitenAfrican Violets at MCCC: Annual Pennington Day NearselauwitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digital Systems Project: IITB CPUDokument7 SeitenDigital Systems Project: IITB CPUAnoushka DeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strangles & Turtle BreakdownsDokument4 SeitenStrangles & Turtle Breakdownsmatheus martinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- US College List-1Dokument6 SeitenUS College List-1nzrunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines For Completing The Volleyball ScoresheetDokument22 SeitenGuidelines For Completing The Volleyball ScoresheetIanne SantorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supplementary English Activities Grade 8Dokument117 SeitenSupplementary English Activities Grade 8derinkatas41Noch keine Bewertungen

- When Does A Team Rotate?Dokument3 SeitenWhen Does A Team Rotate?Sheila Mae AramanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3-4-1-2vs4-4-2midl BlockDokument41 Seiten3-4-1-2vs4-4-2midl BlockMario JovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Model:: Answer KeyDokument55 SeitenModel:: Answer KeyYanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black Iron Beast - 5 - 3 - 1 Calculator PDFDokument5 SeitenBlack Iron Beast - 5 - 3 - 1 Calculator PDFrobinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adult Brochure Fall 2011Dokument72 SeitenAdult Brochure Fall 2011ddsmb100% (1)

- Fast Creek Is A City in South Central Saskatchewan LocatedDokument2 SeitenFast Creek Is A City in South Central Saskatchewan LocatedCharlotteNoch keine Bewertungen

- R11.4 Dylan Alcott The Truth About Growing Up DisabledDokument4 SeitenR11.4 Dylan Alcott The Truth About Growing Up DisabledElisa JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Report of Bmw-1Dokument96 SeitenFinal Report of Bmw-1Shreyansh rajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Choosing The Optimum Material For Making A Bicycle Frame: C. Rontescu, T. D. Cicic, C. G. Amza, O. Chivu, D. DobrotăDokument4 SeitenChoosing The Optimum Material For Making A Bicycle Frame: C. Rontescu, T. D. Cicic, C. G. Amza, O. Chivu, D. DobrotăkevinNoch keine Bewertungen