Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

8.format. Man-Comprehending The Impact of Maternal Influence in Toni - 1

Hochgeladen von

Impact JournalsOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

8.format. Man-Comprehending The Impact of Maternal Influence in Toni - 1

Hochgeladen von

Impact JournalsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

IMPACT : International Journal of Research in

Business Management (IMPACT: IJRBM )

ISSN (P): 2347-4572; ISSN (E): 2321-886X

Vol. 6, Issue 4, Apr 2018, 81-88

© Impact Journals

COMPREHENDING THE IMPACT OF MATERNAL INFLUENCE IN TONI MORRISON’S GOD

HELP THE CHILD

Johnsi. A

Research scholar, Department of English, Nirmala College for Women, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Received: 29 Mar 2018 Accepted: 04 Apr 2018 Published: 30 Apr 2018

ABSTRACT

This study deals with the struggle and focuses on the interpretation of the individual and importance of the role of

Mother in the life of an individual its impact, disordered and traumatic behavior resulting from an unsettling and

disturbing experience.The work attests to the physical and emotional oppression worked out upon children with special

regard on the protagonist Lula Ann Bride well in Toni Morrison’s novel God Help the Child and strives to investigate

alternative modes of thought and behavior in dealing with children. The study further throws light on the true essence of

motherhood, the role of a mother in the initial years of an individual. And how the mother contributes to the individual

development of the children with the right kind of attention and love leads to the attainment of selfhood.

KEYWORDS: Motherhood, Individual, Oppression, Behaviour, Attention, and Love

INTRODUCTION

There can be no systematic study of women in patriarchal culture, no theory of women’s oppression, that does not

take into account women’s role as a daughter of mothers and as a mother of daughters, that does not study female identity

in relation to previous and subsequent generation of women, and that does not study that relationship in the wider context

in which it takes place: the emotional, economic and symbolic structure of family and society.

The mother--daughter relationship is evidently a recurrent theme in most of the autobiographies written by women

writers. Most autobiographies focus at least on one parent, naturally, the one who has influenced them more.

This influence which is positive in most cases could also be negative at times.

Critics of women’s writing have questioned whether women’s writing is characterized by female poetics of

affiliation that depends on the daughter’s relation to her mother. Feminist writers like Adrienne Rich and Nancy Chodorow

have strongly supported with path-breaking works like Of Women Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution

(Rich, 1976), and The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender (Chodorow, 1978).

They have argued that the relationship of the infant to the female parent is an important factor in the development of

identity.

They are of the opinion that it is the girl-child’s role as a daughter and later as a mother that forms an integral part

of her womanhood. Rich observes in her book Of Women Born that:

Impact Factor(JCC): 2.9867 - This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

82 Johnsi. A

The cathexis between mother and daughter- essential, distorted, misused- is the great unwritten story.

Probably there is nothing in human nature more resonant with changes than the flow of energy between two biologically

like bodies… (225)

The “mother” here implies not only the biological mother but all those other mother-figures who influence a

girl-child. Their role in the lives of a child has a greater significance. There are many untold stories were the breach

between the mother and the child leads to the psychological unpredictability in an individual.

Nancy Chodorow’s psychoanalytic feminism is especially mother directed, even if it is not mothercentred.

According to her, it is the intimacy to the mother that defines the process of women’s development in culture.

Chodorow believes that children wish to remain one with their mother, and expect that she will never have different

interests from them, yet they define development in terms of growing away from her. Chodorow in her book Of Women

Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution states that: “In the face of their dependence, lack of certainty of her

emotional permanence, fear of merging, and overwhelming love and attachment, a mother looms large and powerful” (82)

On the other hand, several psychoanalysts suggest that the mother symbolizes dependence, regression, passivity,

and the lack of adaptation to reality. Turning from the mother represents independence, individuation, progress,

activity, and participation in the real world. It is by turning away from our mother that we finally become, by going our

different paths, grown and women.Sometimes the mother-daughter connection is so strong and overwhelming that it stifles

the daughter’s growth as an individual. In her efforts to plumb the depth of human emotion, Toni Morrison returns again

and again to that most fundamental of personal relationships- the tie between mother and child. Motherhood is at the very

core of human experience, and truly grasps our capacity for love, for grief, for pain, for survival, one must take the full

measure of motherhood.

GOD HELP THE CHILD

Morrison is able to take historically and culturally African American interpretation of maternity and strip away

the socially imposed limitation on motherhood, thereby exposing the universal humanity of that experience.

Morrison dissolves the boundaries of the maternal role, creating an ever-widening, integrational definition of the concept

of mothering.

Toni Morrison’s God Help the Childleafs through the consequences of the recurrence of the past terrible

experiences in the makeup of the present and the memory of childhood on the individual’s psyche. The inter-racism

characteristic of America in the times of slavery, represented in the novel through the character of Sweetness; and the

second is the contemporary American society where blackness represents beauty, also represented in the text through the

black protagonist, Bride.

The novel discusses Morrison’s major themes in her well-known works as racial bigotry, black skin color and

center-periphery relationships. It is also, as the title indicates, about childhood and the way to confront childhood past

ghost to better reclaim the present and the future. The story of the novel revolves around Lula Ann Bridewell, Morrison’s

black protagonist, born to light skin parents, the father Louis and the mother Sweetness.

Morrison’s novel starts with the birth of Lula Ann. From the moment she is born, her mother is repelled by her,

as she has skin so black that it scares her mother, sweetness explains “Midnight black, Sudanese black” (3).

NAAS Rating: 3.09- Articles can be sent to editor@impactjournals.us

Comprehending the Impact of Maternal Influence in Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child 83

The hostility grows when Lula Ann’s father leaves them because he does not believe that he can be the father of a girl as

black as Lula Ann. Lula Ann’s mother looks back at how she and her husband had three good years together and how it

changed when Lula Ann was born. He blamed her “and treated Lula Ann like she was a stranger – more than that, an

enemy” (5).

As a dark baby girl, Lula Ann Bridewell was refused by her father and hated by her mother because of her black

epidermal signs. The child’s dark skin embarrassed the mother to the extent that she obliges the daughter to call her

sweetness instead of mom. She even tried once to kill her by pressing a blanket on her face and withholds any kind of

affection and love for her.

I hate to say it, but from the very beginning in the maternity ward the baby, Lula Ann, embarrassed me. Her birth

skin was pale like all babies’, even African ones, but it changed fast. I thought I was going crazy when she turned

blue-black right before my eyes. I know I went crazy for a minute because once-just for a few seconds- I held a blanket

over her face and pressed. (4-5)

Sweetness, with her ironic name, rears Lula Ann in a patriarchal authoritarian way. Lula Ann grows up bereft of

affection and love, which destroys the mother--daughter bond. Patriarchal motherhood prevents Sweetness from

developing the necessary emotion and affection ties with her daughter, critical during the first years of a child’s life.

Lula Ann remembers how her mother loathed touching her dark skin, “distaste was all over her face when I was little and

she had to bathe me.”(31) Lula Ann also recalls how she made little mistakes deliberately so that her mother would touch

her hateful skin. Lula Ann actually feels glad when she soils her bed sheet with her first menstrual blood and her mother

slap her, being handled “by a mother who avoided physical contact whenever possible”(79).

As an infant, Lula Ann misses being close to her mother. She remembers hiding behind the door to hear

Sweetness hum some blue song, thinking how nice it would have been if they could have sung together. Sweetness’s

withdrawal of affection is her daughter’s worst memory. Lula Ann is desperately in need of love. That is why she testifies

against a teacher, Sofia Huxley, and lies about her pervert abuses of children, “to get some love- from her mama” (156).

Lula Ann remembers how Sweetness was kind of mother like the day she colludes with her classmates to accuse

their teacher, a white woman named Sofia Huxley, of sexually molesting them. Smiling at her and even holding her hand

when they walked down the courthouse steps, which she had never done before. “I glanced at Sweetness; she was smiling

like I’ve never seen her smile before- with mouth and eyes”. (31)

Sweetness neglects her maternal duties so as not to confront the rejection of the society. She does not take Lula

Ann much outside because those who see her baby in the carriage give a start or jump back before frowning.

Sweetness does not want to be seen as her mother. She does not attend parent-teachers meetings or volleyball games either.

The racial self-contempt that Sweetness, who has accepted an inferior definition of the black self, inculcates in her

daughter does not allow her to have a sense of belonging or identity.

Things got better but I still had to be careful. Very careful in how I raised her. I had to be strict, very strict.

Lula Ann needed to learn how to behave, how to keep her head down and not to make trouble. I don’t care how many

times she changes her name. Her color is a cross she will always carry. (7)

Impact Factor(JCC): 3.6586 - This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

84 Johnsi. A

Sweetness believes that “there was no point in being tough or sassy even when you were right.”(41) to help black

children cope with racism, their parents teach them special skills, self-reliance, self-defense, dealing with pain and

disappointments. However, Sweetness’s motherhood only seeks absolute and uncontested obedience. She does not foster a

positive racial identity in her daughter so she can resist racist practices, cultural norms, values and expectations of the

dominant culture.

Lula Ann’s upbringing and disciplining are really harsh and even more when she is turning an adolescent.

Her rearing was all about following rules, which she obeyed. “I behaved and behaved and behaved” (32). And yet Lula

Ann feels that

She never knew the right thing to do or say or remember what the rules were. Leave the spoon in the cereal bowl

or place it next to the bowl; tie her shoelaces with a bow or a double knot; fold her socks down or pull them straight up to

the calf? What were the rules when did they change? (78-79)

Despite all the suffering, Sweetness’ patriarchal motherhood cannot preserve her daughter from the curse that

starts with Mr. Leigh’s insults when Lula Ann sees him abusing a boy. He calls her nigger and cunt. Lula Ann, who is only

six years old, does not need the definitions of the words because she feels the hate and revulsion they are charged with.

Lula Ann learns her mother’s lessons and “let the name-calling, the bullying travel like poison, like lethal viruses

through her veins, with no antibiotic available building up immunity so tough that not being a nigger girl was all she

needed to win” (57). Sweetness’ patriarchal motherhood does not focus on meeting Lula Ann’s cultural and emotional

needs. She is more concerned about her daughter living up to the standards, norm-abiding ideas, consensus values and

expectation of the white-dominated racist society.

When Lula Ann has to testify, her mother is very nervous thinking that her daughter’s performance may put her to

shame, instead of being worried about her stressful situation.

I was nervous thinking she would stumble getting up to stand or stutter, or forget what the psychologists said and

put me to shame…I sat through most of the days of the trial, not all just the days when Lula Ann was scheduled to appear

because many witnesses were postponed or never showed. She looked scared but she stayed quite (42).

Sweetness fails to fulfill the three essential tasks of maternal practice, without which the child will not be able to

confront racial injustices or develop a strong sense of black selfhood. Deprived of affection, effective preservation and

culture-bearing, Lula Ann has to struggle her whole life for self-definition, trying to protect herself from being hurt.

At the age of sixteen, she drops out of high school and flees home. Lula Ann changes her “dumb countrified name” (11)

and calls herself Bride. Bride’s memory as an adult is still stuck in her experiences of childhood traumas and refuses to

forget her mother’s avoidance. She builds a new life for herself, escaping from her mother’s and society’s definitions.

Bride reinvents herself. She becomes the regional manager of a prosperous cosmetic business, Sylvia Inc., and leads a

glamorous life. “She had stitched together: personal glamour, control in an exciting even creative profession,

sexual freedom and most of all a shield that protected her from any overly intense feeling, be it rage, embarrassment or

love.”(79)

Being a successful woman she finds vengeance in selling her elegant blackness to her childhood ghost,

her tormentors, so they can feel envious of her triumph. And still, her past is with her.

NAAS Rating: 3.09- Articles can be sent to editor@impactjournals.us

Comprehending the Impact of Maternal Influence in Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child 85

Bride tries to make amends for the terrible lie she told as a young girl but, in the process, her boyfriend Booker

walks out on her and bride decides to approach her former teacher, who has recently been released on parole, to make

recompense for her imprisonment but Huxley greets Bride with a vicious, disfiguring beat down. She learns that making

amends does not always go according to plan.

I reverted to the Lula Ann who never fought back. Ever. I just lay there while she beat the shit out of me…. I

didn’t make a sound, didn’t even raise a hand to protect myself when she slapped my face then punched me in the ribs

before smashing my jaw with her fist then butting my head with hers.(32)

Bride’s relationship with her lover, Booker Starbern, has just run aground. Bride suspects that Booker’s leaving

has instigated her body’s melting away. As she heals from her run-in with Huxley, Bride notices that her body has begun

regressing towards some prepubescent stage, her pubic hair suddenly disappears, her earlobe piercings close, and she stops

menstruating.

I shouldn’t have –trusted him, I mean. I spilled my heart to him; he told me nothing about himself. I talked;

he listened. Then he split, left without a word. Mocking me, dumping me exactly as Sofia Huxley did…. but I really

thought I had found my guy. “You not the woman” is the last thing I expected to hear.(62)

Bride decides to track down Booker to find out why he exited their relationship. Bride says, her failures in adult

life her breakup with Booker, her boyfriend or being beaten by Sofia Huxley makes her realize that, in spite of her

mother’s strict lessons, she is helpless in the presence of confounding cruelty. She just obeyed, never fought back.

She feels that she is “Too weak, too scared to defy Sweetness, or the landlord, or Sofia Huxley, there was nothing in the

world left to do but stand up for herself finally and confront the first man she had bared her soul to, unaware that he was

mocking her.”(79)

All along the novel, the extent of harm sweetness’s patriarchal motherhood has inflicted on Bride is exposed.

Her traumatic childhood experiences keep surfacing. Her lost identity is symbolized by physical regression, “back into a

scared little black girl” (142), triggered by Booker’s rejection. She becomes conscious that “she had counted on her looks

for so long-how well beauty worked. She had not known its shallowness or her own cowardice, the vital lesson Sweetness

taught and nailed to her spine to curve it”. (151)

Bride’s journey to find Booker takes her to the woods of northern California, where she wrecks her car and meets

with a white family. The bride also meets Rain, a semi-feral girl who has suffered terrible abuse on her mother’s hands.

Rain is the emerald-eyed girl who finds Bride stuck in the crashed car. Evelyn tells Bride that she and her husband had

found Rain drenched in rain alone on a wintry night. They dried, fed and cleaned her and tried to find out the house of

Rain. While Evelyn thinks that she rescued Rain from something terrible.

The hippy couple Steve and Evelyn have named her Rain in reference to her purity, innocence and unspoiled

nature. Rain confides in Bride that she is prostituted and sexually abused for money, in return, for her mother. Once she

opposes this act, her mother throws her outdoor. This steered the hatred towards her mother. The common memory of her

mother is so bitter that a six-year-old confesses her urge to chop off her mother’s head.

“She wouldn’t let me back in. I kept pounding on the door. She opened it once to throw me my sweater.”

As Bride imagined the scene her stomach fluttered. How could anybody do that to a child, any child, and one’s own?

Impact Factor(JCC): 3.6586 - This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

86 Johnsi. A

“If you saw your mother again what would you say to her?” Rain grinned. “Nothing. I’d chop her head off.” (102)

In rural California, Bride confronts Booker and her confession to him makes her feel newly born. “No longer

forced to relive, no, outlive the disdain of her mother and the abandonment of her father” (162). The bride tells him about

her pregnancy and he offers her “the hand she had craved all her life, the hand that did not need a lie to deserve it, the hand

of trust and caring for” (175).

At the end of the novel, Bride acquires, apparently, the sense of self-required to mother her baby and not to

reproduce Sweetness. “A child.New life. Immuneto evil or illness, protected from kidnap, beatings, rape, racism, insult,

hurt, self-loathing, abandonment…so they believe” (175). There is a ray of hope in the ending of this brisk tale. In the last

chapter, Morrison discloses Sweetness as sick guilt-ridden women in a nursing home. She wants to believe that she had

raised her daughter right to cope with the harsh reality black people had to face and states “I wasn’t a bad mother” (43).

And yet, her words, “But it’s not my fault. It’s not my fault. It’s not my fault. It’s not” (7), a prayer or chant, seems to

convey her concealed feelings of guilt at her distorted motherhood.

God Help the Child is filled with various themes that revisit traumatic moments in the black history and culture.

Toni Morrison has voiced African American experiences of racism and has particularly concentrated on the oppression

inflicted upon children. Indeed, the theme of child abuse and trauma has been recurrent in her major works including

Beloved, The Bluest Eye, Tar Baby among the others.

The characters in God Help the Child care deprived of parental love and compassion and left the alone fighting to

overstep the ghost of childhood horrific experiences to build up their future. The bride is an example of survival; she firmly

battled the nightmares of her past to offer them a happy living in the present.Mother is a child’s first link to any emotional

bonding and attachment. Children learn their first emotion in relation to their mother. The way the mother bonds with the

child in the initial years will leave a deep impact on the child’s overall well-being and development. The mother and child

relationship created will greatly influence the way the child behaves in social and emotional settings, especially in later

years. As a mother, how soon one reacts to the child’s needs and how one tries to take care of those needs will teach the

child a lot about understanding others’ and his/her emotional requirements.

CONCLUSIONS

Mothers have a greater responsibility in shaping their child’s personality and psyche. The way a mother nurtures

and cherishes her child is reflected in the future self of the individual. It may be destructive or constructive; it all depends

on the way the child is treated from the infancy onwards. Mothers are like roots to a tree; their contribution to the growth

of the tree is never seen on the surface but without the deep penetration of the roots and its aid to the tree, the tree will be

soon lifeless.

REFERENCES

1. Arya, Kavita. Blackhole in the Dust: The Novels of Toni Morrison. New Delhi: Adhyayan Publishers &

Distributors, 2010. Print.

2. Beaulieu, Elizabeth Ann, ed. The Toni Morrison Encyclopedia. USA: Greenwood Press, 2003.Print.

NAAS Rating: 3.09- Articles can be sent to editor@impactjournals.us

Comprehending the Impact of Maternal Influence in Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child 87

3. Bloom, Lynn. “Heritages: Dimensions of Mother-Daughter Relationships in Women’s Autobiographies.”

The Lost Tradition. Cathy Davidson and E.M. Broner, eds. New York: Fredrick Ungar Publishing Co, 1980.

Print.

4. Chodorow, Nancy. The Reproduction of Mothering.Berkeley: U of California, 1978. Print.

5. Gachan, Dina. “5 Ways God Help the Child Yet again proves that Toni Morrison is an Icon” Bustle.22 Apr.2015.

Web.17 Dec.2017.

6. Morrison, Toni. God Help the Child. London: Replika Press, 2015. Print.

7. Ramirez, Manuela Lopez. “What You Do to Children Matters: Toxic Motherhood in Toni Morrison’s God Help

the Child”. The Grove. Spain: N.P, 2015. Print.

8. Walker, Kara “Toni Morrison’s, God Help the Child”. The New York Times 13 Apr. 2015, 178. Print.

9. Wordworks, Manitou, ed. Modern Black Writers.2nd Ed. USA: St. James Press, 1999. Print.

10. Zayed, Jihan. “Polyphony of Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child” Global Journal of Arts: Humanities and

Social Sciences Vol.4 (2016): 34-41. Print.

11. De Beauvoir, Simone. Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter.Trans. James Kirup. New York: Popular Library, 1963.

Print.

12. Pattnaik, Minushree, and Itishri Sarangi. "A GLIMPSE ON THE FICTIONAL WORKS OF TONI MORRISON."

13. Flax, Jane. “Mother-Daughter Relationships: Psychodynamics, Politics, and Philosophy”. The Future of

Difference, eds Einstein and A. Jardine. Boston: G.K. Hall,1980. Print.

14. Scoble, Frank. “Mothers and Daughters: Living the Lie” Denver Quarterly 18.4 (1984): 7-12. Print.

15. Rich, Adrienne. Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution.New York: W.W. Norton &

Company, Inc, 1976. Print.

16. Christian, Barbara T. “Shadows Uplifted”. Black Women Novelists: The Development of a Tradition.

Connecticut: Grenwood Press, 1980. Print.

Impact Factor(JCC): 3.6586 - This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 19-11-2022-1668838190-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal-A Study of Emotional Maturity of Primary School StudentsDokument6 Seiten19-11-2022-1668838190-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal-A Study of Emotional Maturity of Primary School StudentsImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 09-12-2022-1670567569-6-Impact - Ijrhal-05Dokument16 Seiten09-12-2022-1670567569-6-Impact - Ijrhal-05Impact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19-11-2022-1668837986-6-Impact - Ijrhal-2. Ijrhal-Topic Vocational Interests of Secondary School StudentsDokument4 Seiten19-11-2022-1668837986-6-Impact - Ijrhal-2. Ijrhal-Topic Vocational Interests of Secondary School StudentsImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12-11-2022-1668238142-6-Impact - Ijrbm-01.Ijrbm Smartphone Features That Affect Buying Preferences of StudentsDokument7 Seiten12-11-2022-1668238142-6-Impact - Ijrbm-01.Ijrbm Smartphone Features That Affect Buying Preferences of StudentsImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14-11-2022-1668421406-6-Impact - Ijrhal-01. Ijrhal. A Study On Socio-Economic Status of Paliyar Tribes of Valagiri Village AtkodaikanalDokument13 Seiten14-11-2022-1668421406-6-Impact - Ijrhal-01. Ijrhal. A Study On Socio-Economic Status of Paliyar Tribes of Valagiri Village AtkodaikanalImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12-10-2022-1665566934-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-2. Ideal Building Design y Creating Micro ClimateDokument10 Seiten12-10-2022-1665566934-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-2. Ideal Building Design y Creating Micro ClimateImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 28-10-2022-1666956219-6-Impact - Ijrbm-3. Ijrbm - Examining Attitude ...... - 1Dokument10 Seiten28-10-2022-1666956219-6-Impact - Ijrbm-3. Ijrbm - Examining Attitude ...... - 1Impact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 25-08-2022-1661426015-6-Impact - Ijrhal-8. Ijrhal - Study of Physico-Chemical Properties of Terna Dam Water Reservoir Dist. Osmanabad M.S. - IndiaDokument6 Seiten25-08-2022-1661426015-6-Impact - Ijrhal-8. Ijrhal - Study of Physico-Chemical Properties of Terna Dam Water Reservoir Dist. Osmanabad M.S. - IndiaImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 09-12-2022-1670567289-6-Impact - Ijrhal-06Dokument17 Seiten09-12-2022-1670567289-6-Impact - Ijrhal-06Impact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 22-09-2022-1663824012-6-Impact - Ijranss-5. Ijranss - Periodontics Diseases Types, Symptoms, and Its CausesDokument10 Seiten22-09-2022-1663824012-6-Impact - Ijranss-5. Ijranss - Periodontics Diseases Types, Symptoms, and Its CausesImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21-09-2022-1663757902-6-Impact - Ijranss-4. Ijranss - Surgery, Its Definition and TypesDokument10 Seiten21-09-2022-1663757902-6-Impact - Ijranss-4. Ijranss - Surgery, Its Definition and TypesImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 05-09-2022-1662375638-6-Impact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Analysis of Impact of Covid-19 On Religious Tourism Destinations of Odisha, IndiaDokument12 Seiten05-09-2022-1662375638-6-Impact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Analysis of Impact of Covid-19 On Religious Tourism Destinations of Odisha, IndiaImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19-09-2022-1663587287-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal - Instability of Mother-Son Relationship in Charles Dickens' Novel David CopperfieldDokument12 Seiten19-09-2022-1663587287-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal - Instability of Mother-Son Relationship in Charles Dickens' Novel David CopperfieldImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 29-08-2022-1661768824-6-Impact - Ijrhal-9. Ijrhal - Here The Sky Is Blue Echoes of European Art Movements in Vernacular Poet Jibanananda DasDokument8 Seiten29-08-2022-1661768824-6-Impact - Ijrhal-9. Ijrhal - Here The Sky Is Blue Echoes of European Art Movements in Vernacular Poet Jibanananda DasImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 23-08-2022-1661248618-6-Impact - Ijrhal-6. Ijrhal - Negotiation Between Private and Public in Women's Periodical Press in Early-20th Century PunjabDokument10 Seiten23-08-2022-1661248618-6-Impact - Ijrhal-6. Ijrhal - Negotiation Between Private and Public in Women's Periodical Press in Early-20th Century PunjabImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monitoring The Carbon Storage of Urban Green Space by Coupling Rs and Gis Under The Background of Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutralization of ChinaDokument24 SeitenMonitoring The Carbon Storage of Urban Green Space by Coupling Rs and Gis Under The Background of Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutralization of ChinaImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 23-08-2022-1661248432-6-Impact - Ijrhal-4. Ijrhal - Site Selection Analysis of Waste Disposal Sites in Maoming City, GuangdongDokument12 Seiten23-08-2022-1661248432-6-Impact - Ijrhal-4. Ijrhal - Site Selection Analysis of Waste Disposal Sites in Maoming City, GuangdongImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08-08-2022-1659935395-6-Impact - Ijrbm-2. Ijrbm - Consumer Attitude Towards Shopping Post Lockdown A StudyDokument10 Seiten08-08-2022-1659935395-6-Impact - Ijrbm-2. Ijrbm - Consumer Attitude Towards Shopping Post Lockdown A StudyImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 25-08-2022-1661424708-6-Impact - Ijranss-7. Ijranss - Fixed Point Results For Parametric B-Metric SpaceDokument8 Seiten25-08-2022-1661424708-6-Impact - Ijranss-7. Ijranss - Fixed Point Results For Parametric B-Metric SpaceImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06-08-2022-1659783347-6-Impact - Ijrhal-1. Ijrhal - Concept Mapping Tools For Easy Teaching - LearningDokument8 Seiten06-08-2022-1659783347-6-Impact - Ijrhal-1. Ijrhal - Concept Mapping Tools For Easy Teaching - LearningImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 24-08-2022-1661313054-6-Impact - Ijranss-5. Ijranss - Biopesticides An Alternative Tool For Sustainable AgricultureDokument8 Seiten24-08-2022-1661313054-6-Impact - Ijranss-5. Ijranss - Biopesticides An Alternative Tool For Sustainable AgricultureImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Analysis On Environmental Effects of Land Use and Land Cover Change in Liuxi River Basin of GuangzhouDokument16 SeitenThe Analysis On Environmental Effects of Land Use and Land Cover Change in Liuxi River Basin of GuangzhouImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 25-08-2022-1661424544-6-Impact - Ijranss-6. Ijranss - Parametric Metric Space and Fixed Point TheoremsDokument8 Seiten25-08-2022-1661424544-6-Impact - Ijranss-6. Ijranss - Parametric Metric Space and Fixed Point TheoremsImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Analysis On Tourist Source Market of Chikan Ancient Town by Coupling Gis, Big Data and Network Text Content AnalysisDokument16 SeitenThe Analysis On Tourist Source Market of Chikan Ancient Town by Coupling Gis, Big Data and Network Text Content AnalysisImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Succession Planning HRMDokument57 SeitenSuccession Planning HRMANAND0% (1)

- Resume Curphey JDokument2 SeitenResume Curphey Japi-269587395Noch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Management in Education: Mark Gennesis B. Dela CernaDokument36 SeitenAdministrative Management in Education: Mark Gennesis B. Dela CernaMark Gennesis Dela CernaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Fast FoodDokument12 SeitenPhilippines Fast FoodSydney1911Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week 4 - Developing Therapeutic Communication SkillsDokument66 SeitenWeek 4 - Developing Therapeutic Communication SkillsMuhammad Arsyad SubuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Research 1Dokument3 SeitenPractical Research 1Angel Joyce MaglenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tiger ReikiDokument12 SeitenTiger ReikiVictoria Generao88% (17)

- Mandala ConsultingDokument6 SeitenMandala ConsultingkarinadapariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acrp - A2 Unit OutlineDokument11 SeitenAcrp - A2 Unit Outlineapi-409728205Noch keine Bewertungen

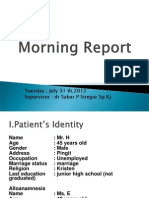

- Tuesday, July 31 TH, 2012 Supervisor: DR Sabar P Siregar SP - KJDokument44 SeitenTuesday, July 31 TH, 2012 Supervisor: DR Sabar P Siregar SP - KJChristophorus RaymondNoch keine Bewertungen

- DSWD Research AgendaDokument43 SeitenDSWD Research AgendaCherry Mae Salazar100% (6)

- Explaining The Willingness of Public Professionals To Implement Public Policies - Content, Context and Personality Characteristics-2Dokument17 SeitenExplaining The Willingness of Public Professionals To Implement Public Policies - Content, Context and Personality Characteristics-2Linh PhươngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Service Orientation For Nursing: Presented by Zakaria, SE, MMDokument37 SeitenCustomer Service Orientation For Nursing: Presented by Zakaria, SE, MMzakariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Ideas About MoviesDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper Ideas About Moviesfkqdnlbkf100% (1)

- Problem Solving-Practice Test A PDFDokument23 SeitenProblem Solving-Practice Test A PDFPphamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Power of Language EssayDokument5 SeitenPower of Language Essayapi-603001027Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mixed Strategies and Nash Equilibrium: Game Theory Course: Jackson, Leyton-Brown & ShohamDokument10 SeitenMixed Strategies and Nash Equilibrium: Game Theory Course: Jackson, Leyton-Brown & ShohamTanoy DewanjeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prayer To Mother KundaliniDokument19 SeitenPrayer To Mother KundaliniBrahmacari Sarthak Chaitanya100% (1)

- Sociolinguistics Christine Mallinson Subject: Sociolinguistics Online Publication Date: Nov 2015Dokument3 SeitenSociolinguistics Christine Mallinson Subject: Sociolinguistics Online Publication Date: Nov 2015Krish RaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Đăng kí học Tiếng Anh trực tuyến cùng với cô Mai Phương tại website ngoaingu24h.vnDokument5 SeitenĐăng kí học Tiếng Anh trực tuyến cùng với cô Mai Phương tại website ngoaingu24h.vnThị Thanh Vân NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Item Unit Cost Total Cost Peso Mark Up Selling Price Per ServingDokument1 SeiteItem Unit Cost Total Cost Peso Mark Up Selling Price Per ServingKathleen A. PascualNoch keine Bewertungen

- Higher English 2012 Paper-AllDokument18 SeitenHigher English 2012 Paper-AllAApril HunterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Day Bang - How To Casually Pick Up Girls During The Day-NotebookDokument11 SeitenDay Bang - How To Casually Pick Up Girls During The Day-NotebookGustavo CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Homo Economicus To Homo SapiensDokument28 SeitenFrom Homo Economicus To Homo SapiensLans Gabriel GalineaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allensworth & Easton (2007)Dokument68 SeitenAllensworth & Easton (2007)saukvalleynewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communicating Assurance Engagement Outcomes and Performing Follow-Up ProceduresDokument16 SeitenCommunicating Assurance Engagement Outcomes and Performing Follow-Up ProceduresNuzul DwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Erik Hjerpe Volvo Car Group PDFDokument14 SeitenErik Hjerpe Volvo Car Group PDFKashaf AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- MantrasDokument5 SeitenMantrasNicola De ZottiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 11 Integrating SandP 10 Tools For Progress Monitoring in PsychotherapyDokument45 Seiten2012 11 Integrating SandP 10 Tools For Progress Monitoring in Psychotherapypechy83100% (1)

- Letter of Request: Mabalacat City Hall AnnexDokument4 SeitenLetter of Request: Mabalacat City Hall AnnexAlberto NolascoNoch keine Bewertungen