Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

M C - A P: Clinical Practice

Hochgeladen von

Kak DhenyOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

M C - A P: Clinical Practice

Hochgeladen von

Kak DhenyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

C LINICA L PRAC TIC E

Clinical Practice

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

a common clinical problem. Evidence supporting various Diagnosis and Treatment of Pneumonia

strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal

guidelines, when they exist. The article ends with the authors’ Patients with pneumonia usually present with cough

clinical recommendations. (more than 90 percent), dyspnea (66 percent), sputum

production (66 percent), and pleuritic chest pain (50

percent), although nonrespiratory symptoms can also

M ANAGEMENT OF C OMMUNITY - predominate.11,12 Elderly patients may report fewer

symptoms.13,14 Unfortunately, information obtained

A CQUIRED P NEUMONIA from the history or physical examination cannot rule

in or rule out the diagnosis of pneumonia with ade-

ETHAN A. HALM, M.D., M.P.H., quate accuracy.15 All rigorous definitions of pneumo-

AND ALVIN S. TEIRSTEIN, M.D. nia require the finding of a pulmonary infiltrate on a

chest radiograph.16

A 65-year-old man with hypertension and de- The initial antibiotic regimen should be chosen em-

generative joint disease presents to the emergen- pirically to cover common typical and atypical patho-

cy department with a three-day history of a pro- gens (Table 1). Pneumonia due to atypical organisms

ductive cough and fever. He has a temperature (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, legionella species, and Chla-

of 38.3°C (101°F), a blood pressure of 144/92 mydia pneumoniae) accounts for 20 to 40 percent of

mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per cases and cannot be differentiated from cases due to

minute, a heart rate of 90 beats per minute, and typical bacteria on the basis of the patient’s history, the

oxygen saturation of 92 percent while breath- results of the physical examination, or findings on chest

ing room air. Physical examination reveals only radiographs.17,18 Two large observational cohort stud-

crackles and egophony in the right lower lung ies found that antibiotic regimens that cover both typ-

field. The white-cell count is 14,000 per cubic mil- ical and atypical organisms are associated with a low-

limeter, and the results of routine chemical tests er risk of death than regimens that cover just typical

are normal. A chest radiograph shows an infil- bacteria.19,20

trate in the right lower lobe. How should this pa- Although rigorous data regarding the duration of

tient be treated? therapy are limited, most experts recommend a total

of 10 to 14 days. Intravenous therapy with antibiotics

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM that have a high level of oral bioavailability (e.g., fluor-

There are approximately 4 million cases of com- oquinolones) may be no better than oral therapy with

munity-acquired pneumonia in the United States each such antibiotics in patients with uncomplicated infec-

year, resulting in about 1 million hospitalizations.1-3 tions who have a functioning gastrointestinal tract.21,22

Inpatient management of pneumonia is more than 20

times as expensive as outpatient care and costs an es- Risk Stratification and the Decision to Hospitalize

timated $9 billion a year.2,3 The length of hospitaliza- Between 30 percent and 50 percent of patients

tion is the key determinant of inpatient costs.2,4 Previ- who are hospitalized with pneumonia have low-risk

ous studies have found wide variations in the rates and cases, many of which could potentially be managed at

lengths of hospitalization among patients with pneu- home.23-25 Indeed, most low-risk patients would pre-

monia that are not explained by differences in the char- fer to be treated as outpatients.26 Although physicians

acteristics of the patients or the severity of disease.5-10 base the decision about admission on their overall as-

This article focuses on the initial management of com- sessment of the severity of illness, they tend to over-

munity-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent estimate the risk of death.27 The average 30-day mor-

adults. tality rate among patients with pneumonia is 13.7

percent, but it ranges from 5.1 percent in studies in-

From the Department of Health Policy (E.A.H.) and the Divisions of

volving ambulatory and hospitalized patients to 36.5

General Internal Medicine (E.A.H.) and Pulmonary and Critical Care Med- percent in studies involving patients who required in-

icine (A.S.T.), Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, tensive care.28

New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Halm at the Department of Health

Policy, Box 1077, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1 Gustave L. Levy Pl., The decision regarding hospitalization should be

New York, NY 10029, or at ethan.halm@mountsinai.org. based on the stability of the patient’s clinical condition,

N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 25 · December 19, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 2039

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on November 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

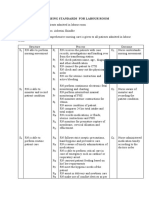

TABLE 1. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE INITIAL EMPIRICAL TREATMENT OF PNEUMONIA.

HOSPITAL SETTING ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY* COMMON ORGANISMS

General inpatient ward Third-generation cephalosporin plus a macrolide or Typical pathogens: Streptococcus pneu-

doxycycline moniae, Haemophilus influenzae

Antipneumococcal fluoroquinolone Atypical pathogens: Mycoplasma

b-Lactam–b-lactamase inhibitor plus a macrolide or pneumoniae, legionella species,

doxycycline Chlamydia pneumoniae

Intensive care unit

No risk of Pseudo- Third-generation cephalosporin plus an antipneumo- Same as above plus Staphylococcus

monas aeruginosa coccal fluoroquinolone or a macrolide aureus, drug-resistant S. pneumo-

infection b-Lactam–b-lactamase inhibitor plus antipneumo- niae, other gram-negative rods

coccal fluoroquinolone or macrolide

At risk for P. aerugi- Antipseudomonal b-lactam plus aminoglycoside plus Same as above plus P. aeruginosa,

nosa infection antipneumococcal fluoroquinolone or macrolide other resistant gram-negative rods

Antipseudomonal b-lactam plus ciprofloxacin

*Third-generation cephalosporins include ceftriaxone (1 to 2 g per day), ceftizoxime (1 to 2 g every 8 to 12 hours),

and cefotaxime (1 to 2 g every 6 to 8 hours). Doxycycline is given at a dose of 100 mg every 12 hours. Antipneumococcal

fluoroquinolones include levofloxacin (500 mg per day), gatifloxacin (400 mg per day), and moxifloxacin (400 mg per day).

Macrolide antibiotics include azithromycin (500 mg per day), erythromycin (500 mg every 6 hours), and clarithromycin

(500 mg every 12 hours). A b-lactam–b-lactamase inhibitor is ampicillin–sulbactam (1.5 to 3.0 g every six hours). Anti-

pseudomonal b-lactams include piperacillin–tazobactam (3.375 g every 6 hours) and cefepime (1 to 2 g every 12 hours).

the risk of death and complications, the presence or from traditional teaching in emphasizing that an age

absence of other active medical problems, and psycho- of more than 65 years alone is not an indication for

social characteristics. Disease-specific prediction rules admission.

are available that can be used to assess the initial sever- Some low-risk patients, especially those who are

ity of pneumonia and predict the risk of death. Such elderly or in class III of the Pneumonia Severity Index,

instruments can help inform the decision to hospital- may look sick or be reluctant to be treated at home.

ize a patient. The most widely used and rigorously Many of these patients may be appropriate candidates

studied prediction rule — the Pneumonia Severity for a short stay or 23 hours of inpatient observation.

Index — has been validated in more than 50,000 pa- This strategy allows them to receive antibiotic therapy

tients from a variety of inpatient and outpatient pop- and any needed hydration while their condition is

ulations (Fig. 1).23,29 monitored for deterioration. The risk of worsening,

The Pneumonia Severity Index is based on data that although very low, is highest on the day of presenta-

are commonly available at presentation and stratifies tion and decreases considerably thereafter,33 so patients

patients into five risk classes in which 30-day mortality whose condition is stable throughout the first hospital

rates range from 0.1 percent to 27.0 percent. The high- day should subsequently do well. The few patients

er the score, the higher the risk of death, admission to who do not have a favorable response to this approach

the intensive care unit, and readmission and the long- can then be admitted as traditional inpatients.

er the length of stay. Easy-to-use versions of the index Patients at moderate risk (class IV of the Pneumo-

are now available on the Internet (http://ursa.kcom. nia Severity Index) and high risk (class V) should be

edu/CAPcalc/default.htm, http://ncemi.org, and hospitalized, given their much higher rates of death

http://www.emedhomom.com/dbase.cfm)30-32 and and complications. In general, most such patients are

handheld computers. elderly and have two or more additional poor prog-

An algorithm that uses the Pneumonia Severity In- nostic factors, such as serious coexisting conditions,

dex to judge the appropriateness of admission is shown abnormal vital signs, and abnormal laboratory values.

in Figure 2. Patients in risk classes I, II, and III are All patients with hypoxemia (defined by an oxygen

at low risk for death, and most can be safely treated saturation of less than 90 percent or a partial pressure

as outpatients in the absence of extenuating circum- of arterial oxygen of less than 60 mm Hg in a patient

stances. who is breathing room air) or serious hemodynamic

The availability of oral antibiotics that attain high instability should be hospitalized regardless of their

serum levels has made outpatient treatment even eas- score on the Pneumonia Severity Index. Other indica-

ier to recommend than in the past. An algorithm tions for admission include suppurative or metastatic

based on the Pneumonia Severity Index deviates most disease (empyema, lung abscess, endocarditis, menin-

2040 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 25 · December 19, 2002 · www.nejm.org

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on November 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

CLINICA L PRAC TIC E

CHARACTERISTIC NO. OF POINTS

Patient with community-acquired Demographic factors ASSIGNED

pneumonia

Age

Men Age (in yr)

Women Age (in yr)¡10

Nursing home resident +10

Is the patient more than Yes

Coexisting illnesses

50 years of age? Neoplastic disease +30

Liver disease +20

No Congestive heart failure +10

Cerebrovascular disease +10

Does the patient have a history Renal disease +10

of any of the following Findings on physical examination

coexisting conditions? Altered mental status +20

Neoplastic disease Yes

Respiratory rate »30/min +20

Liver disease Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg +20

Congestive heart failure Temperature <35°C or »40°C +15

Cerebrovascular disease Pulse »125 beats/min +10

Renal disease

Laboratory and radiographic findings

No Arterial pH <7.35 +30

Blood urea nitrogen »30 mg/dl +20

Does the patient have any of (11 mmol/liter)

the following abnormalities Sodium <130 mmol/liter +20

on physical examination? Glucose »250 mg/dl (14 mmol/liter) +10

Altered mental status Hematocrit <30% +10

Yes

Respiratory rate »30/min Partial pressure of +10

Systolic blood pressure arterial oxygen <60 mm Hg

<90 mm Hg or oxygen saturation <90%

Temperature <35°C or »40°C Pleural effusion +10

Pulse »125 beats/min

No

Stratification of Risk Score

Assign patient to Assign patient to RISK RISK CLASS SCORE MORTALITY

risk class I risk class II, III, Low I Based on algorithm 00.1%

IV, or V accord- Low II «70 00.6%

ing to total Low III 71–90 00.9%

score using the Moderate IV 91–130 09.3%

prediction rule High V >130 27.0%

Figure 1. The Pneumonia Severity Index.

The Pneumonia Severity Index is used to determine a patient’s risk of death. The total score is obtained by adding to the patient’s

age (in years for men or in years¡10 for women) the points assigned for each additional applicable characteristic.

Data have been adapted from Fine et al.23

gitis, or osteomyelitis) or infection due to high-risk cent). There were no significant differences between

pathogens (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative groups in the hospitalization rates among moderate-

rods, and anaerobes). and high-risk patients for whom the protocol recom-

Several studies have established the safety and ef- mended admission. The intervention reduced the over-

fectiveness of an approach involving an admission- all number of hospital bed-days per patient without

decision algorithm that is based on the Pneumonia any increase in deaths, complications, use of the inten-

Severity Index. The strongest evidence comes from a sive care unit, or readmissions or any decrement in the

randomized, controlled trial involving 19 hospitals.25 health-related quality of life.

The hospitals that were randomly assigned to imple- This trial confirmed the findings of a study in which

ment the protocol admitted fewer low-risk patients a similar triage protocol decreased the initial hospital-

than did the control hospitals (31 percent vs. 49 per- ization rates among low-risk patients, from 58 per-

N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 25 · December 19, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 2041

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on November 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

Diagnosis of pneumonia confirmed in an

immunocompetent adult with community-acquired

pneumonia on the basis of signs and symptoms

and the finding of an infiltrate on chest radiography

Absolute contraindications to outpatient treatment

Hypoxemia (oxygen saturation <90% while patient

Yes

is breathing room air)

Hemodynamic instability

Active coexisting condition requiring hospitalization

Inability to tolerate oral medications

No

Use Pneumonia Severity Index to determine risk

Yes

Risk class I, II, or III Risk class IV or V

Other mitigating factors

Frail physical condition Yes

No response to oral therapy

Unstable living situation

No

Outpatient treatment Intermediate options Inpatient treatment

Brief inpatient stay

23 hours of observation

Admission to subacute care facility

Intravenous antibiotics at home

Home care with nursing visits

Close outpatient follow-up

Figure 2. Algorithm for Determining Whether a Patient with Community-Acquired Pneumonia Should Be Admitted or Treated as

an Outpatient.

cent to 43 percent, without any change in the rates hospitalization. The most common reasons for admit-

of death, symptom resolution, functional recovery, or ting low-risk patients include the presence of coexist-

patient satisfaction.24 The implementation of a some- ing conditions, patients’ preferences, and inadequate

what different (but related) algorithm in urgent care home support.36

clinics also increased the proportion of low-risk pa-

Criteria for Clinical Stability and Discharge

tients who were treated at home without compromis-

ing patient outcomes.34,35 These studies also confirm Once a patient is hospitalized and has received ap-

that selected low-risk elderly patients with pneumo- propriate antibiotic therapy, the most important de-

nia can be treated as outpatients with good results. cision is determining when their condition is clinically

Though this research shows that many low-risk pa- stable and they are ready to go home. To be consid-

tients who have traditionally been hospitalized can ered ready for discharge, patients should have stable

safely be treated at home, many still require or desire vital signs, have adequate oxygenation while breathing

2042 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 25 · December 19, 2002 · www.nejm.org

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on November 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

C LINICA L PRAC TIC E

determine the appropriateness of discharge rather

TABLE 2. CRITERIA FOR DETERMINING than rigidly specifying the number of days of hos-

THE APPROPRIATENESS OF DISCHARGE.

pitalization.

Patient’s vital signs are stable for 24-hour period (i.e.,

Though the condition of the average patient will

temperature «37.8°C [100°F], respiratory rate «24 become clinically stable on the third or fourth day of

breaths per minute, heart rate «100 beats per minute, sys- hospitalization,33 patients need to be told that they will

tolic blood pressure »90 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation

»90% while patient is breathing room air or at base line probably feel sick for a while. One week after present-

for patients with chronic obstructive lung disease or those ing with pneumonia, 80 percent of patients report fa-

receiving oxygen therapy at home). tigue and cough and 50 percent report dyspnea and

Patient is able to take oral antibiotics.

sputum production.12 It is often a few weeks before all

Patient is able to maintain adequate hydration and nutrition.

Patient’s mental status is normal (or at his or her base-line

their symptoms resolve and they return to their usual

level). activities.11,12,49

Patient has no other active clinical or psychosocial problems

requiring hospitalization. GUIDELINES

Two national subspecialty organizations have pub-

lished guidelines for the management of community-

acquired pneumonia. The guidelines of the Infectious

Diseases Society of America (updated in 2000) en-

room air, be able to take oral antibiotics and main- dorse the use of the Pneumonia Severity Index as

tain their oral intake, and have returned to their base- providing “a rational foundation for the decision re-

line mental status (Table 2). They should also have no garding hospitalization.”50 The recommended admis-

other active medical or psychosocial problems that re- sion-decision algorithm is similar to that depicted in

quire inpatient management. Figure 2. The guidelines state that patients in class I

Overall, the median time to clinical stability is three or II do not usually require hospitalization, those in

days among low-risk patients, four days among mod- class III may require a brief inpatient stay, and those

erate-risk patients, and six days among those at high in class IV or V should be hospitalized.

risk.33 Once a patient’s condition becomes stable, the The 2001 guidelines of the American Thoracic So-

risk of serious clinical deterioration is 1 percent or less, ciety,51 although acknowledging the value of predic-

even among the sickest subgroup of patients. Con- tion rules like the Pneumonia Severity Index, recom-

versely, patients who are discharged before their con- mend that patients with “multiple risk factors” for a

dition has stabilized have higher risk-adjusted rates of complicated course be admitted. The guidelines list

death or readmission and return more slowly to their these prognostic factors (many of which are included

usual activities.37 Several randomized controlled trials in the Pneumonia Severity Index), but it does not

and observational studies corroborate the safety of this specify how these data might be used to inform the

type of discharge criteria.25,38-43 Although these stud- decision about admission. Both guidelines indicate

ies used various designs and ways of defining clinical that old age alone is not a reason for hospitalization.

stability, they all stressed the importance of the reso- The American Thoracic Society recommends that

lution of fever, improving respiratory signs or symp- patients be switched to oral antibiotics and discharged

toms, the ability to take oral antibiotics, and the ab- on the same day that the patient’s clinical condition

sence of other active medical problems. stabilizes, if other medical and social factors permit.

Similar stability criteria can be used to determine The society uses the following criteria for switching

when patients can be switched from parenteral to oral therapy to oral antimicrobial agents (which should also

antibiotics. This topic has recently been systematically apply to the discharge decision): an improvement in

reviewed.43 In brief, data from randomized controlled cough and dyspnea, a temperature of 37.8°C (100°F)

trials and prospective studies indicate that early con- or less on two occasions eight hours apart, a decreas-

version from intravenous to oral therapy does not ing white-cell count, and a functioning gastrointestinal

adversely affect outcomes.25,38-41,44-46 In addition, ev- tract with adequate oral intake. The Infectious Dis-

idence from observational studies suggests that there eases Society of America does not specify discharge

is no need to observe patients for 24 hours after a criteria but does recommend timely conversion to

switch to oral therapy.47,48 treatment with highly bioavailable oral agents when

The condition of individual patients will stabilize the patient’s condition becomes stable and he or she

at different times depending on the initial severity can tolerate oral medicines. Both guidelines imply that

of pneumonia, the presence or absence of coexisting the average hospital course can probably be shorter

conditions, and the response to therapy. Therefore, than previously thought appropriate, since most pa-

practice guidelines, critical pathways, and utilization- tients have an adequate clinical response to therapy

management rules should use objective criteria to within three days.

N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 25 · December 19, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 2043

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on November 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY age. He has no other major risk factors or serious ab-

The randomized controlled trials supporting our normalities in laboratory data or vital signs that in-

recommendations largely used a new antipneumococ- crease his risk of a poor outcome. His Pneumonia

cal fluoroquinolone or an advanced macrolide antibi- Severity Index score corresponds to risk class II and a

otic (agents that cover both typical and atypical organ- predicted 30-day mortality rate of less than 1 percent.

isms) to treat outpatients. This strategy has been Because his condition is hemodynamically stable, he

associated with better outcomes than the use of more has adequate oxygenation while breathing room air,

narrowly focused initial regimens.19,20 We are less con- and there are no contraindications to outpatient care,

fident that oral therapy at home with non–first-line we would recommend that he be treated as an out-

regimens, such as treatment with a penicillin or ceph- patient and receive an oral antibiotic that covers both

alosporin alone, can achieve equally favorable results. typical and atypical organisms (an advanced macrolide

Although many experts suggest that a short period of or antipneumococcal fluoroquinolone). Finally, we

observation in the hospital is appropriate for “sicker- would recommend that, in the future, the patient re-

appearing” low-risk patients, there have been no pub- ceive the pneumococcal vaccine if he has not previous-

lished trials of this approach. There are no definitive ly been immunized.

data addressing whether the criteria for discharge

should vary depending on the pathogen (if known) or Dr. Halm is supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

the presence or absence of complications. An extended Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars Program.

course of intravenous antibiotics is generally recom-

REFERENCES

mended for patients with legionella infection, bacte-

remia due to high-risk organisms (S. aureus or gram- 1. Clinical classifications for health policy research: hospital inpatient sta-

tistics, 1996. Rockville, Md.: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research,

negative rods), or suppurative complications (e.g., 1999. (AHCPR publication no. 99-0034).

empyema). Nearly all the studies we reviewed excluded 2. Niederman MS, McCombs JS, Unger AN, Kumar A, Popovian R. The

patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cost of treating community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Ther 1998;20:820-

37.

infection. The discharge criteria we highlight are from 3. Lave JR, Lin CJ, Fine MJ, Hughes-Cromwick P. The cost of treating

studies that defined stability as demonstrated by a 24- patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care

hour period in which vital signs were normal.29,33,37 Med 1999;20:189-97.

4. Fine MJ, Pratt HM, Obrosky DS, et al. Relation between length of hos-

Other studies have required just an 8-hour or 16-hour pital stay and costs of care for patients with community-acquired pneumo-

period of stable vital signs.25,40,41 There are no good nia. Am J Med 2000;109:378-85.

5. Wennberg JE, Freeman JL, Culp WJ. Are hospital services rationed in

data comparing the alternative definitions. New Haven or over-utilised in Boston? Lancet 1987;1:1185-9.

6. McMahon LF Jr, Wolfe RA, Tedeschi PJ. Variation in hospital admis-

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS sions among small areas: a comparison of Maine and Michigan. Med Care

We believe that most low-risk patients with pneu- 1989;27:623-31.

7. Burns LR, Wholey DR. The effects of patient, hospital, and physician

monia (those in class I, II, or III of the Pneumonia characteristics on length of stay and mortality. Med Care 1991;29:251-71.

Severity Index) can be treated at home in the absence 8. Cleary PD, Greenfield S, Mulley AG, et al. Variations in length of stay

and outcomes for six medical and surgical conditions in Massachusetts and

of extenuating circumstances. The condition of low- California. JAMA 1991;266:73-9.

risk patients who are admitted is likely to stabilize very 9. Fine MJ, Singer DE, Phelps AL, Hanusa BH, Kapoor WN. Differences

quickly, and these patients may need to spend just a in length of hospital stay in patients with community-acquired pneumonia:

a prospective four-hospital study. Med Care 1993;31:371-80.

few days in the hospital. Conversely, moderate-risk and 10. McCormick D, Fine MJ, Coley CM, et al. Variation in length of hos-

high-risk patients (those in class IV and class V, respec- pital stay in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: are shorter

tively) should be admitted. Once the condition of pa- stays associated with worse medical outcomes? Am J Med 1999;107:5-12.

11. Fine MJ, Stone RA, Singer DE, et al. Processes and outcomes of care

tients is clinically stable, they should be switched to for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneu-

oral antibiotic therapy and discharged within 24 hours monia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) cohort study. Arch In-

tern Med 1999;159:970-80.

(unless they have other medical or psychosocial prob- 12. Metlay JP, Fine MJ, Schulz R, et al. Measuring symptomatic and func-

lems requiring inpatient management). Before being tional recovery in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Gen In-

discharged from the emergency department or the tern Med 1997;12:423-30.

13. Metlay JP, Schulz R, Li YH, et al. Influence of age on symptoms at

hospital, all patients should be informed about the presentation in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern

length of time it will take them to recover and alerted Med 1997;157:1453-9.

to the signs of clinical worsening that would require 14. Mehr DR, Binder EF, Kruse RL, Zweig SC, Madsen RW, D’Agostino

RB. Clinical findings associated with radiographic pneumonia in nursing

urgent medical attention. Although data are lacking, home residents. J Fam Pract 2001;50:931-7.

we believe that most patients who have HIV infection 15. Metlay JP, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ. Does this patient have community-

acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical ex-

and true community-acquired pneumonia can be treat- amination. JAMA 1997;278:1440-5.

ed in the same way as any other patients with pneu- 16. Bartlett JG, Mundy LM. Community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J

monia, unless they have advanced HIV disease. Med 1995;333:1618-24.

17. Marston BJ, Plouffe JF, File TM Jr, et al. Incidence of community-

With respect to the case vignette, the patient’s Pneu- acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization: results of a population-based

monia Severity Index score is 65 on the basis of his active surveillance study in Ohio. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1709-8.

2044 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 25 · December 19, 2002 · www.nejm.org

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on November 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

C LINICA L PRAC TIC E

18. Marrie TJ. Community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18: 36. Halm EA, Atlas SJ, Borowsky LH, et al. Understanding physician ad-

501-13. herence with a pneumonia practice guideline: effects of patient, system,

19. Gleason PP, Meehan TP, Fine JM, Galusha DH, Fine MJ. Associations and physician factors. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:98-104.

between initial antimicrobial therapy and medical outcomes for hospital- 37. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN, Singer DE, Marrie TJ, Siu AL. In-

ized elderly patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2562- stability on hospital discharge and the risk of adverse outcomes in patients

72. with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1278-84.

20. Houck PM, MacLehose RF, Niederman MS, Lowery JK. Empiric an- 38. Rhew DC, Riedinger MS, Sandhu M, Bowers C, Greengold N,

tibiotic therapy and mortality among Medicare pneumonia inpatients in 10 Weingarten SR. A prospective, multicenter study of a pneumonia practice

western states: 1993, 1995, and 1997. Chest 2001;119:1420-6. guideline. Chest 1998;114:115-9.

21. Sanders WE Jr, Morris JF, Alessi P, et al. Oral ofloxacin for the treat- 39. Weingarten SR, Riedinger MS, Hobson P, et al. Evaluation of a pneu-

ment of acute bacterial pneumonia: use of a nontraditional protocol to monia practice guideline in an interventional trial. Am J Respir Crit Care

compare experimental therapy with “usual care” in a multicenter clinical Med 1996;153:1110-5.

trial. Am J Med 1991;91:261-6. 40. Ramirez JA, Srinath L, Ahkee S, Huang A, Raff MJ. Early switch

22. Chan R, Hemeryck L, O’Regan M, Clancy L, Feely J. Oral versus in- from intravenous to oral cephalosporins in the treatment of hospitalized

travenous antibiotics for community acquired lower respiratory tract infec- patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 1995;

tion in a general hospital: open, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1995; 155:1273-6.

310:1360-2. 41. Ramirez JA, Vargas S, Ritter GW, et al. Early switch from intravenous

23. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low- to oral antibiotics and early hospital discharge: a prospective observational

risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997; study of 200 consecutive patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

336:243-50. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2449-54.

24. Atlas SJ, Benzer TI, Borowsky LH, et al. Safely increasing the propor- 42. Weingarten SR, Riedinger MS, Varis G, et al. Identification of low-risk

tion of patients with community-acquired pneumonia treated as outpa- hospitalized patients with pneumonia: implications for early conversion to

tients: an interventional trial. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1350-6. oral antimicrobial therapy. Chest 1994;105:1109-15.

25. Marrie TJ, Lau CY, Wheeler SL, Wong CJ, Vandervoort MK, Feagan 43. Rhew DC, Tu GS, Ofman J, Henning JM, Richards MS, Weingarten

BG. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community- SR. Early switch and early discharge strategies in patients with community-

acquired pneumonia. JAMA 2000;283:749-55. acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:722-7.

26. Coley CM, Li YH, Medsger AR, et al. Preferences for home vs hos- 44. Siegel RE, Halpern NA, Almenoff PL, Lee A, Cashin R, Greene JG.

pital care among low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A prospective randomized study of inpatient i.v. antibiotics for community-

Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1565-71. acquired pneumonia: the optimal duration of therapy. Chest 1996;110:

27. Fine MJ, Hough LJ, Medsger AR, et al. The hospital admission deci- 965-71.

sion for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the 45. Omidvari K, de Boisblanc BP, Karam G, Nelson S, Haponik E, Sum-

pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern mer W. Early transition to oral antibiotic therapy for community-acquired

Med 1997;157:36-44. pneumonia: duration of therapy, clinical outcomes, and cost analysis.

28. Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of Respir Med 1998;92:1032-9.

patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 46. Hendrickson JR, North DS. Pharmacoeconomic benefit of antibiotic

1996;275:134-41. step-down therapy: converting patients from intravenous ceftriaxone to

29. Auble TE, Yealy DM, Fine MJ. Assessing prognosis and selecting an oral cefpodoxime proxetil. Ann Pharmacother 1995;29:561-5.

initial site of care for adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Infect 47. Rhew DC, Hackner D, Henderson L, Ellrodt AG, Weingarten SR.

Dis Clin North Am 1998;12:741-59. [Erratum, Infect Dis Clin North Am The clinical benefit of in-hospital observation in ‘low-risk’ pneumonia pa-

2000;14:xi.] tients after conversion from parenteral to oral antimicrobial therapy. Chest

30. Community acquired pneumonia CAP prognostic calculator. (Accessed 1998;113:142-6.

November 22, 2002, at http://ursa.kcom.edu/CAPcalc/default.htm.) 48. Dunn AS, Peterson KL, Schechter CB, Rabito P, Gotlin AD, Smith

31. Pneumonia Severity Index risk calculator. (Accessed November 22, LG. The utility of an in-hospital observation period after discontinuing in-

2002, at http://www.ncemi.org/cgi-ncemi/edecision. travenous antibiotics. Am J Med 1999;106:6-10.

pl?TheCommand=Load&NewFile=community- 49. Marrie TJ, Lau CY, Wheeler SL, Wong CJ, Feagan BG. Predictors of

acquired_pneumonia_mortality_risk&BlankTop=1). symptom resolution in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin

32. Pneumonia Severity Index risk calculator. (Accessed November 22, Infect Dis 2000;31:1362-7.

2002, at http://www.emedhome.com/dbase.cfm.) 50. Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, Mandell LA, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Fine

33. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ, et al. Time to clinical stability in pa- MJ. Practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneu-

tients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for monia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:347-82.

practice guidelines. JAMA 1998;279:1452-7. 51. Niederman MS, Mandell LA, Anzueto A, et al. Guidelines for the

34. Dean NC, Suchyta MR, Bateman KA, Aronsky D, Hadlock CJ. Im- management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: diagnosis,

plementation of admission decision support for community-acquired pneu- assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Respir

monia. Chest 2000;117:1368-77. Crit Care Med 2001;163:1730-54.

35. Suchyta MR, Dean NC, Narus S, Hadlock CJ. Effects of a practice

guideline for community-acquired pneumonia in an outpatient setting.

Am J Med 2001;110:306-9. Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society.

N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 25 · December 19, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 2045

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on November 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Infections in Cancer Chemotherapy: A Symposium Held at the Institute Jules Bordet, Brussels, BelgiumVon EverandInfections in Cancer Chemotherapy: A Symposium Held at the Institute Jules Bordet, Brussels, BelgiumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nac 2017Dokument18 SeitenNac 2017Nataly CortesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thwaites 2004Dokument11 SeitenThwaites 2004Navisa HaifaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 394 Full PDFDokument20 Seiten394 Full PDFHaltiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Reading ParuDokument53 SeitenJournal Reading ParuDaniel IvanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 Pneumonia Review ofDokument4 Seiten08 Pneumonia Review ofMonika Margareta Maria ElviraNoch keine Bewertungen

- NeumoniaDokument28 SeitenNeumoniaresidentes isssteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2021 - TorresDokument28 Seiten2021 - TorresCarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recognition and Prevention of Nosocomial Pneumonia in The ICU and Infection Control in Mechanical VentilationDokument11 SeitenRecognition and Prevention of Nosocomial Pneumonia in The ICU and Infection Control in Mechanical Ventilationandres felipe burgos granadosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cap AsmaDokument10 SeitenCap AsmaAuliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treatment of CAP: Stratifying Care Based on SeverityDokument16 SeitenTreatment of CAP: Stratifying Care Based on SeverityditaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review: Atypical Pathogen Infection in Community-Acquired PneumoniaDokument7 SeitenReview: Atypical Pathogen Infection in Community-Acquired PneumoniaDebi SusantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spiraling Out of Control: Clinical Problem-SolvingDokument6 SeitenSpiraling Out of Control: Clinical Problem-SolvingjjjkkNoch keine Bewertungen

- 30794136: Aspiration Pneumonia in Older AdultsDokument7 Seiten30794136: Aspiration Pneumonia in Older AdultsNilson Morales CordobaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0221 Community-Acquired-PneumoniaDokument29 Seiten0221 Community-Acquired-PneumoniaDiego YanezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospital PneumoniaDokument15 SeitenHospital Pneumoniarivai anwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- BMJ 2021 065871.fullDokument24 SeitenBMJ 2021 065871.fullEfen YtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients With Covid-19 - Preliminary ReportDokument11 SeitenDexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients With Covid-19 - Preliminary ReportGino IturriagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pneumonia Mimics: Pearls and Pitfalls: MAY 26TH, 2016Dokument11 SeitenPneumonia Mimics: Pearls and Pitfalls: MAY 26TH, 2016Marcel DocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Necrotizing Pneumonia in Cancer Patients A.8Dokument4 SeitenNecrotizing Pneumonia in Cancer Patients A.8Manisha UppalNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Institute For Health and Clinical Excellence Scope: 1 Guideline TitleDokument8 SeitenNational Institute For Health and Clinical Excellence Scope: 1 Guideline TitleJefrizal Mat ZainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparison of Methicillin-Resistant Community-Acquired and Healthcare-Associated PneumoniaDokument8 SeitenComparison of Methicillin-Resistant Community-Acquired and Healthcare-Associated PneumoniaSuarniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neumonia Anciano 2014Dokument8 SeitenNeumonia Anciano 2014Riyandi MardanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients With Covid-19Dokument11 SeitenDexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients With Covid-19michaelwillsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 5811@westjem 2018 12 37335Dokument8 Seiten10 5811@westjem 2018 12 37335bobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Micoplasma en NiñosDokument11 SeitenMicoplasma en Niños17091974Noch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Management CPA PediatricDokument3 SeitenSurgical Management CPA PediatricIndah Nur LathifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of Flexible Bronchoscopy in The Diagnosis of Infectious Etiologies - A Literature ReviewDokument4 SeitenUse of Flexible Bronchoscopy in The Diagnosis of Infectious Etiologies - A Literature ReviewAna MercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- GripeDokument10 SeitenGripeSCIH HFCPNoch keine Bewertungen

- Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Infections: ReviewDokument12 SeitenNon-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Infections: Reviewmgoez077Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fungalinfections in The Icu: Marya D. Zilberberg,, Andrew F. ShorrDokument18 SeitenFungalinfections in The Icu: Marya D. Zilberberg,, Andrew F. ShorrGiselle BaiãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primer: BronchiectasisDokument18 SeitenPrimer: BronchiectasisAnanta Bryan Tohari WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neumonia IDokument9 SeitenNeumonia IMario RomoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Envenimations ViperinesDokument6 SeitenEnvenimations ViperinesIJAR JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pneumonia ElderlyDokument13 SeitenPneumonia ElderlyAndreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pneumonia: V. Mandang, M.DDokument44 SeitenPneumonia: V. Mandang, M.DMeggy SumarnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coccidioidomycosis PDFDokument7 SeitenCoccidioidomycosis PDFAustine OsaweNoch keine Bewertungen

- Severe Covid-19: Clinical PracticeDokument10 SeitenSevere Covid-19: Clinical PracticejoelNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Randomized Trial of Convalescent Plasma in Covid-19 Severe PneumoniaDokument11 SeitenA Randomized Trial of Convalescent Plasma in Covid-19 Severe PneumoniaRinawati UnissulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Characteristics of Chronic Cough in Pakistani AdultsDokument5 SeitenCharacteristics of Chronic Cough in Pakistani AdultslupNoch keine Bewertungen

- 09-1434 FinallDokument2 Seiten09-1434 FinallRemy SummersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hemoptysis in A Healthy 13-Year-Old Boy: PresentationDokument5 SeitenHemoptysis in A Healthy 13-Year-Old Boy: PresentationluishelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rosas, Et AllDokument14 SeitenRosas, Et AllrezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Intervention in AIP Improves OutcomesDokument9 SeitenEarly Intervention in AIP Improves OutcomesHerbert Baquerizo VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAP Diagnostic (Uptoptodate 2019)Dokument34 SeitenCAP Diagnostic (Uptoptodate 2019)elizabeth perezzNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1056@NEJMoa1812379Dokument12 Seiten10 1056@NEJMoa1812379alvaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Incidence and Risk Factors For Ventilator Associated Pneumon 2007 RespiratorDokument6 SeitenIncidence and Risk Factors For Ventilator Associated Pneumon 2007 RespiratorTomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nac Leve Diseño de Estudios Cid 2008Dokument2 SeitenNac Leve Diseño de Estudios Cid 2008Gustavo GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10-Effect of Chest Physical Therapy On Pediatrics Hospitalized With Pneumonia PDFDokument8 Seiten10-Effect of Chest Physical Therapy On Pediatrics Hospitalized With Pneumonia PDFandina100% (1)

- Nonimaging Diagnostic Tests For Pneumonia: Anupama Gupta Brixey,, Raju Reddy,, Shewit P. GiovanniDokument14 SeitenNonimaging Diagnostic Tests For Pneumonia: Anupama Gupta Brixey,, Raju Reddy,, Shewit P. GiovannikaeranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bag-Mask Ventilation During Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill AdultsDokument11 SeitenBag-Mask Ventilation During Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill AdultsRitmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sdra PDFDokument22 SeitenSdra PDFalfred1294Noch keine Bewertungen

- Treatment Options of Spontaneous Pneumothorax: Abdullah Al-QudahDokument10 SeitenTreatment Options of Spontaneous Pneumothorax: Abdullah Al-QudahIneMeilaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Pneumonia InternasionalDokument8 SeitenJurnal Pneumonia InternasionalDina AryaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nebulized Colistin in The Treatment of Pneumonia Due To Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii and Pseudomonas AeruginosaDokument4 SeitenNebulized Colistin in The Treatment of Pneumonia Due To Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii and Pseudomonas AeruginosaPhan Tấn TàiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 Pneumonia Review ofDokument4 Seiten08 Pneumonia Review ofSandra ZepedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pneumonia ComunitariaDokument10 SeitenPneumonia ComunitariaMaulida HalimahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal InternationalDokument6 SeitenJurnal InternationalLeonal Yudha PermanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurding Paru 1Dokument12 SeitenJurding Paru 1Clinton SudjonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pyogenic Brain Abscess A 15 Year SurveryDokument10 SeitenPyogenic Brain Abscess A 15 Year SurverySilvia RoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- DHENYDokument1 SeiteDHENYKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terima Sem I ObatDokument3 SeitenTerima Sem I ObatKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book 1Dokument3 SeitenBook 1Kak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kunci Jawaban Sistem Gerak TumbuhanDokument1 SeiteKunci Jawaban Sistem Gerak TumbuhanKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lembar Penerimaan Obat No Nama Barang Persediaan Satuan Obat Rencana Permintaan Harga StuanDokument2 SeitenLembar Penerimaan Obat No Nama Barang Persediaan Satuan Obat Rencana Permintaan Harga StuanKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- DownloadDokument53 SeitenDownloadKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Latihan ABC AnalisisDokument8 SeitenLatihan ABC AnalisisKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- M C - A P: Clinical PracticeDokument7 SeitenM C - A P: Clinical PracticeKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lembar Penerimaan Obat No Nama Barang Persediaan Satuan Obat Rencana Permintaan Harga StuanDokument2 SeitenLembar Penerimaan Obat No Nama Barang Persediaan Satuan Obat Rencana Permintaan Harga StuanKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nama-Nama Guru SLB MP Iii BantulDokument3 SeitenNama-Nama Guru SLB MP Iii BantulKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lembar Penerimaan Obat No Nama Barang Persediaan Satuan Obat Rencana Permintaan Harga StuanDokument2 SeitenLembar Penerimaan Obat No Nama Barang Persediaan Satuan Obat Rencana Permintaan Harga StuanKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nanananana PDFDokument1 SeiteNanananana PDFKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hiv and Aids: Last Reviewed: 06/21/2011Dokument10 SeitenHiv and Aids: Last Reviewed: 06/21/2011Kak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- UKK English Practice Test for Grade 4 StudentsDokument3 SeitenUKK English Practice Test for Grade 4 StudentsKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypo Parathyroid Ism Leaflet WebDokument2 SeitenHypo Parathyroid Ism Leaflet WebKak DhenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Efficacy of Non-Sedating Antihistamine Updosing in Patients With Chronic UrticariaDokument6 SeitenComparative Efficacy of Non-Sedating Antihistamine Updosing in Patients With Chronic UrticariadregleavNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHN Exercise 1 - Paola Mariz P. CeroDokument3 SeitenCHN Exercise 1 - Paola Mariz P. CeroPaola Mariz P. CeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Standards for Labour RoomDokument3 SeitenNursing Standards for Labour RoomRenita ChrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENL 110 APA In-Text-Citations and References ActivityDokument5 SeitenENL 110 APA In-Text-Citations and References ActivityNajat Abizeid SamahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. clinical observerships help IMGs gain experienceDokument8 SeitenU.S. clinical observerships help IMGs gain experienceAkshit ChitkaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- H Pylori Diet EbookDokument232 SeitenH Pylori Diet EbookDori Argi88% (8)

- Nursing Diagnosis and Plan of Care for Anemia with Chronic DiseaseDokument6 SeitenNursing Diagnosis and Plan of Care for Anemia with Chronic DiseaseChristine Joy FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effectiveness of Massage and Manual Therapy'Dokument5 SeitenEffectiveness of Massage and Manual Therapy'Kinjal SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malignant Hyperthermia: Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Recommendations Recommendations For Hospital Emergency DepartmentsDokument6 SeitenMalignant Hyperthermia: Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Recommendations Recommendations For Hospital Emergency DepartmentsHelend Ndra TaribukaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maturity Onset Diabetes of The Young: Clinical Characteristics, Diagnosis and ManagementDokument10 SeitenMaturity Onset Diabetes of The Young: Clinical Characteristics, Diagnosis and ManagementatikahanifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 @dentallib Douglas Deporter Short and Ultra Short ImplantsDokument170 Seiten2018 @dentallib Douglas Deporter Short and Ultra Short Implantsilter burak köseNoch keine Bewertungen

- PESCI Recalls PDFDokument9 SeitenPESCI Recalls PDFDanishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Nursing Care PlanDokument26 SeitenFamily Nursing Care PlanAmira Fatmah QuilapioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Four Humors Theory in Unani MedicineDokument4 SeitenFour Humors Theory in Unani MedicineJoko RinantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metabolic EncephalopathyDokument22 SeitenMetabolic Encephalopathytricia isabellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hipopresivos y Dolor Lumbar Cronico 2021Dokument9 SeitenHipopresivos y Dolor Lumbar Cronico 2021klgarivasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complications After CXLDokument3 SeitenComplications After CXLDr. Jérôme C. VryghemNoch keine Bewertungen

- SickLeaveCertificate With and Without Diagnosis 20240227 144109Dokument2 SeitenSickLeaveCertificate With and Without Diagnosis 20240227 144109Sawad SawaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Protect Yourself and OthersDokument2 SeitenHow To Protect Yourself and OtherslistmyclinicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthopaedic Surgery Fractures and Dislocations: Tomas Kurakovas MF LL Group 29Dokument13 SeitenOrthopaedic Surgery Fractures and Dislocations: Tomas Kurakovas MF LL Group 29Tomas Kurakovas100% (1)

- What Is ScabiesDokument7 SeitenWhat Is ScabiesKenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prescribing Information: 1. Name of The Medicinal ProductDokument5 SeitenPrescribing Information: 1. Name of The Medicinal Productddandan_20% (1)

- Eeg, PSG, Sleep DisordersDokument48 SeitenEeg, PSG, Sleep DisordersIoana MunteanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seth AnswerDokument27 SeitenSeth AnswerDave BiscobingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written Exam-2!2!2013Dokument1 SeiteWritten Exam-2!2!2013Charm MeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infusion Pumps, Large-Volume - 040719081048Dokument59 SeitenInfusion Pumps, Large-Volume - 040719081048Freddy Cruz BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Green White Minimalist Modern Real Estate PresentationDokument8 SeitenGreen White Minimalist Modern Real Estate Presentationapi-639518867Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adult Early Warning Score Observation Chart For High Dependency UnitDokument2 SeitenAdult Early Warning Score Observation Chart For High Dependency Unitalexips50% (2)

- Margin Elevation Technique PDFDokument6 SeitenMargin Elevation Technique PDFUsman SanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Postterm Pregnancy - UpToDateDokument16 SeitenPostterm Pregnancy - UpToDateCarlos Jeiner Díaz SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionVon EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityVon EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (13)

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearVon EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (23)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsVon EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityVon EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (78)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeVon EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsVon EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementVon EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (40)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossVon EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (4)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisVon EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (8)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsVon EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (169)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingVon EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (33)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsVon EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingVon EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Von EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (110)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesVon EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (34)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaVon EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeVon EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (253)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingVon EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsVon EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyVon EverandRecovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (201)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossVon EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4)