Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Pre-Colonial Times: Keboklagan (Subanon) and Tudbulol

Hochgeladen von

Ivy Marie Lavador ZapantaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Pre-Colonial Times: Keboklagan (Subanon) and Tudbulol

Hochgeladen von

Ivy Marie Lavador ZapantaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The diversity and richness of Philippine literature evolved side by side with the country’s history.

This can best be

appreciated in the context of the country’s pre-colonial cultural traditions and the socio-political histories of its colonial

and contemporary traditions.

The average Filipino’s unfamiliarity with his indigenous literature was largely due to what has been impressed upon

him: that his country was “discovered” and, hence, Philippine “history” started only in 1521.

So successful were the efforts of colonialists to blot out the memory of the country’s largely oral past that

present-day Filipino writers, artists and journalists are trying to correct this inequity by recognizing the country’s wealth

of ethnic traditions and disseminating them in schools and in the mass media.

The rousing of nationalistic pride in the 1960s and 1970s also helped bring about this change of attitude among a

new breed of Filipinos concerned about the “Filipino identity.”

Pre-Colonial Times

Owing to the works of our own archaeologists, ethnologists and anthropologists, we are able to know more and

better judge information about our pre-colonial times set against a bulk of material about early Filipinos as recorded by

Spanish, Chinese, Arabic and other chroniclers of the past.

Pre-colonial inhabitants of our islands showcase a rich past through their folk speeches, folk songs, folk narratives

and indigenous rituals and mimetic dances that affirm our ties with our Southeast Asian neighbors.

The most seminal of these folk speeches is the riddle which is tigmo in Cebuano, bugtong in Tagalog,paktakonin

Ilongo and patototdon in Bicol. Central to the riddle is the talinghaga or metaphor because it “reveals subtle

resemblances between two unlike objects” and one’s power of observation and wit are put to the test.

The proverbs or aphorisms express norms or codes of behavior, community beliefs or they instill values by offering

nuggets of wisdom in short, rhyming verse.

The extended form, tanaga, a mono-riming heptasyllabic quatrain expressing insights and lessons on life is “more

emotionally charged than the terse proverb and thus has affinities with the folk lyric.” Some examples are

the basahanon or extended didactic sayings from Bukidnon and the daraida and daragilon from Panay.

The folk song, a form of folk lyric which expresses the hopes and aspirations, the people’s lifestyles as well as their

loves. These are often repetitive and sonorous, didactic and naive as in the children’s songs

or Ida-ida(Maguindanao), tulang pambata (Tagalog) or cansiones para abbing (Ibanag).

A few examples are the lullabyes or Ili-ili (Ilongo); love songs like the panawagon and balitao (Ilongo);harana or

serenade (Cebuano); the bayok (Maranao); the seven-syllable per line poem, ambahan of the Mangyans that are about

human relationships, social entertainment and also serve as a tool for teaching the young; work songs that depict the

livelihood of the people often sung to go with the movement of workers such as the kalusan (Ivatan), soliranin (Tagalog

rowing song) or the mambayu, a Kalinga rice-pounding song; the verbal jousts/games like the duplo popular during

wakes.

Other folk songs are the drinking songs sung during carousals like the tagay (Cebuano and Waray); dirges and

lamentations extolling the deeds of the dead like the kanogon (Cebuano) or the Annako (Bontoc).

A type of narrative song or kissa among the Tausug of Mindanao, the parang sabil, uses for its subject matter the

exploits of historical and legendary heroes. It tells of a Muslim hero who seeks death at the hands of non-Muslims.

The folk narratives, i.e. epics and folk tales are varied, exotic and magical. They explain how the world was created,

how certain animals possess certain characteristics, why some places have waterfalls, volcanoes, mountains, flora or

fauna and, in the case of legends, an explanation of the origins of things. Fables are about animals and these teach

moral lessons.

Our country’s epics are considered ethno-epics because unlike, say, Germany’s Niebelunginlied, our epics are not

national for they are “histories” of varied groups that consider themselves “nations.”

The epics come in various names: Guman (Subanon); Darangen (Maranao); Hudhud (Ifugao);

andUlahingan(Manobo). These epics revolve around supernatural events or heroic deeds and they embody or validate

the beliefs and customs and ideals of a community. These are sung or chanted to the accompaniment of indigenous

musical instruments and dancing performed during harvests, weddings or funerals by chanters. The chanters who were

taught by their ancestors are considered “treasures” and/or repositories of wisdom in their communities.

Examples of these epics are

the Lam-ang (Ilocano); Hinilawod (Sulod); Kudaman (Palawan); Darangen(Maranao); Ulahingan (Livunganen-Aruman

en Manobo); Mangovayt Buhong na Langit (The Maiden of the Buhong Sky from Tuwaang–Manobo); Ag Tobig neg

Keboklagan (Subanon); and Tudbulol (T’boli).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument5 SeitenLiterary Forms in Philippine LiteratureChristainielle JaspeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hlan Module 2 - Techniques in Reading Poetry and DramasDokument19 SeitenHlan Module 2 - Techniques in Reading Poetry and DramasJohn Mark ValenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Philippine Literature: Gongonan Nu Usin y Amam Maggirawa Pay Sila y Inam. (Campana)Dokument6 SeitenIntroduction To Philippine Literature: Gongonan Nu Usin y Amam Maggirawa Pay Sila y Inam. (Campana)Gian QuiñonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tagalog: para Abbing (Ibanag)Dokument3 SeitenTagalog: para Abbing (Ibanag)Tricia FaithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature Forms ExploredDokument18 SeitenPhilippine Literature Forms ExploredNapoleon B. Favila Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument29 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureJohannin Cazar ArevaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature - National Commission For Culture and The ArtsDokument7 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literature - National Commission For Culture and The ArtsJonvic CasunuranNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument11 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureAnonymous XyXKGEk8mBNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21st Century Lit Topic For MID-TERMDokument54 Seiten21st Century Lit Topic For MID-TERMAvegail Constantino0% (1)

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument6 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDanna Mae Terse YuzonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature: Christine F. Godinez-OrtegaDokument7 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literature: Christine F. Godinez-OrtegaCassy DollagueNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philippine Literary HistoryDokument5 SeitenThe Philippine Literary HistoryRegine Mae AswigueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week002 - The Literary Form in Philippine Literature z33dTf PDFDokument10 SeitenWeek002 - The Literary Form in Philippine Literature z33dTf PDFJunry ManaliliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre Colonial Period LectureDokument3 SeitenPre Colonial Period LectureJared Darren S. OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature - Docx - COPIED NETDokument31 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literature - Docx - COPIED NETJulienne S. RabagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- FinalModule.21st Century LiteratureDokument24 SeitenFinalModule.21st Century Literaturetampocashley15Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument16 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureJames Valdez80% (5)

- Forms of Philipine LiteratureDokument7 SeitenForms of Philipine LiteratureJohn Lee Damondon GilpoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument15 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureLicca ArgallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature TAmmyDokument29 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literature TAmmyNanette Garalde AmbantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument14 SeitenLiterary Forms in Philippine LiteratureJemar LuczonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument12 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureCarla Lizette BenitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument7 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literaturestealth solutionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument8 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureUmmaýya UmmayyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Engluishforms in Philippine LiteratureDokument8 SeitenLiterary Engluishforms in Philippine LiteratureChristian Mark Almagro AyalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ConceptualizationDokument30 SeitenConceptualizationTenshi TenshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discussion Lesson PlanDokument1 SeiteDiscussion Lesson PlanMHELNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Forms in The PhilippinesDokument11 SeitenLiterary Forms in The PhilippinesKmerylENoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature Forms ExploredDokument6 SeitenPhilippine Literature Forms Explorednica-chan0% (2)

- Module 1Dokument7 SeitenModule 1China PandinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literary History from Pre-Colonial to ContemporaryDokument8 SeitenPhilippine Literary History from Pre-Colonial to ContemporaryFernan CapistranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDokument6 SeitenThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureHamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To 21st Century LiteratureDokument6 SeitenIntroduction To 21st Century LiteratureKenyung WuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To 21st Century LiteratureDokument6 SeitenIntroduction To 21st Century LiteratureFranchezka Ainsley AfableNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brief History of 21st Philippine Lit.Dokument30 SeitenBrief History of 21st Philippine Lit.DianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- W8 - Module 0010 - Philippine Pop Culture - Literature PDFDokument7 SeitenW8 - Module 0010 - Philippine Pop Culture - Literature PDFpakupakuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Dokument11 SeitenPhilippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217God Warz Dungeon GuildNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Dokument11 SeitenPhilippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Estelito MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stages of Philippine LiteratureDokument28 SeitenStages of Philippine LiteratureAlethea BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature Across Regions and ErasDokument56 SeitenPhilippine Literature Across Regions and ErasRadzmiya SulaymanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Literary Forms PHDokument11 Seiten3 Literary Forms PHSean C.A.ENoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Literature Course Module Content - Gen EdDokument53 SeitenPhilippine Literature Course Module Content - Gen EdKathy R. PepitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name of Learner: - Grade Level: - Section: - DateDokument3 SeitenName of Learner: - Grade Level: - Section: - DateMarlon Duayao LinsaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethnic Tradition and Spanish Colonial TraditionDokument8 SeitenEthnic Tradition and Spanish Colonial TraditionYzza Veah Esquivel100% (12)

- Philippine LiteratureDokument5 SeitenPhilippine LiteratureMelrene Isabel MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- CW Grade 9 Module 1Dokument11 SeitenCW Grade 9 Module 1Carla MaglantayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Litt PresentationsDokument106 SeitenLitt PresentationsRoanne Davila-MatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Lit Forms ExploredDokument9 SeitenPhilippine Lit Forms ExploredkaskaraitNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21st Cent Lit Week 4-5Dokument20 Seiten21st Cent Lit Week 4-5Juliene Chezka BelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHS Literature 11Dokument7 SeitenSHS Literature 11May Tagalogon Villacora IINoch keine Bewertungen

- HANDOUT 1 LiteratureDokument12 SeitenHANDOUT 1 LiteratureCelina BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21st Century Literature from the Philippines and BeyondDokument17 Seiten21st Century Literature from the Philippines and BeyondRica Valenzuela - AlcantaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Forms and History in the PhilippinesDokument22 SeitenLiterature Forms and History in the PhilippinesClarisle NacanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Week Lit 121Dokument48 Seiten3 Week Lit 121Cassandra Dianne Ferolino MacadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2ND TERM - 21st Century LiteratureDokument10 Seiten2ND TERM - 21st Century LiteratureRaals Internet CafeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21st Century Literature Lesson 1 and 2Dokument25 Seiten21st Century Literature Lesson 1 and 2erickzkieolisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oral Lore From Pre-Colonial Times ( - 1564) : Mr. Harry Dave B. VillasorDokument22 SeitenOral Lore From Pre-Colonial Times ( - 1564) : Mr. Harry Dave B. VillasorJohn Carl AparicioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21St Century Literary Genres Elements, Structures and Traditions Lesson 3Dokument37 Seiten21St Century Literary Genres Elements, Structures and Traditions Lesson 3Alex Abonales Dumandan90% (39)

- Sounds of Other Shores: The Musical Poetics of Identity on Kenya's Swahili CoastVon EverandSounds of Other Shores: The Musical Poetics of Identity on Kenya's Swahili CoastNoch keine Bewertungen

- English CG!Dokument247 SeitenEnglish CG!Ronah Vera B. TobiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homonyms QuizDokument2 SeitenHomonyms QuizIvy Marie Lavador Zapanta0% (1)

- Figures Idioms QuizDokument2 SeitenFigures Idioms QuizIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- News Overview PDFDokument48 SeitenNews Overview PDFEsperval Cezhar CadiaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- HomonymsDokument13 SeitenHomonymsIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Father OlanDokument11 SeitenFather OlanIvy Marie Lavador Zapanta100% (6)

- Grade 7 4th Quarter Semi FinalDokument2 SeitenGrade 7 4th Quarter Semi FinalIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building A CommunityDokument6 SeitenBuilding A CommunityIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task On PhrasesDokument5 SeitenTask On PhrasesIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnalogyDokument6 SeitenAnalogyIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- newspaperPartsID PDFDokument1 SeitenewspaperPartsID PDFKrystallane ManansalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Word Cline Helps Build VocabularyDokument1 SeiteWord Cline Helps Build VocabularyIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wha TDokument2 SeitenWha TIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poblacion Night High School: Anecdotal RecordDokument1 SeitePoblacion Night High School: Anecdotal RecordIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Teachers GuideDokument119 SeitenEnglish Teachers GuideJoemar Furigay78% (9)

- DO No. 40, S. 2012Dokument33 SeitenDO No. 40, S. 2012Ivy Marie Lavador Zapanta88% (8)

- Subject Verb Agreement Sample LessonDokument8 SeitenSubject Verb Agreement Sample LessonIvy Marie Lavador Zapanta100% (1)

- Request Form - Form 137Dokument1 SeiteRequest Form - Form 137Ivy Marie Lavador Zapanta100% (1)

- DO No. 40, S. 2012Dokument33 SeitenDO No. 40, S. 2012Ivy Marie Lavador Zapanta88% (8)

- Program-Nutrition Month 2014Dokument4 SeitenProgram-Nutrition Month 2014Ivy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Invictus poem by William Ernest HenleyDokument1 SeiteInvictus poem by William Ernest HenleyIvy Marie Lavador ZapantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DO No. 40, S. 2012Dokument33 SeitenDO No. 40, S. 2012Ivy Marie Lavador Zapanta88% (8)

- HungarianDokument22 SeitenHungarianFabon CamilleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ug Anthropology Syllabus WbsuDokument15 SeitenUg Anthropology Syllabus WbsuARPITA DUTTANoch keine Bewertungen

- Panjab University Chandigarh List of Graduates - 2020 District: KurukshetraDokument47 SeitenPanjab University Chandigarh List of Graduates - 2020 District: KurukshetraHrshiya SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Supreme Court Upholds Indigenous Peoples ActDokument45 SeitenPhilippines Supreme Court Upholds Indigenous Peoples ActChristian KongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Services Result 2009Dokument23 SeitenCivil Services Result 2009anoopsinhghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scenic ValleyDokument144 SeitenScenic ValleyVũ Quang Hưng0% (1)

- Sherlock Holmes: Sherlock Holmes (/ Ʃɜ Rlɒk Hoʊmz/) Is A Fictional DetectiveDokument33 SeitenSherlock Holmes: Sherlock Holmes (/ Ʃɜ Rlɒk Hoʊmz/) Is A Fictional DetectiveYazi SanNoch keine Bewertungen

- KarateDokument8 SeitenKarateKiki NoviantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Caesar of DeceitDokument5 SeitenThe Caesar of Deceitapi-319241369Noch keine Bewertungen

- Flat For Sale March 2024 GurgaonDokument14 SeitenFlat For Sale March 2024 GurgaonVIJAY KUMARNoch keine Bewertungen

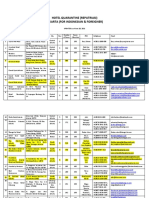

- Hotel For QuarantineDokument7 SeitenHotel For QuarantineElly EllyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iec60273 (Ed3 0) B ImgDokument56 SeitenIec60273 (Ed3 0) B ImgThi Huyen Trang Vu100% (1)

- KPTCL REJECTED APPLICANTSDokument619 SeitenKPTCL REJECTED APPLICANTSNishchith P SeegeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sagbama RoyalDokument10 SeitenSagbama RoyalSJ EndeleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Typesofcommunitiesquiz 1Dokument3 SeitenTypesofcommunitiesquiz 1api-582698270Noch keine Bewertungen

- Final List Candidates NTHP Batch2021Dokument214 SeitenFinal List Candidates NTHP Batch2021imtiazhusseinlangahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pacs NZBDokument28 SeitenPacs NZBksm256Noch keine Bewertungen

- Te RauparahaDokument15 SeitenTe RauparahaCyril GilfedderNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of CoDokument687 SeitenList of Comadeelhassan67% (3)

- George Adamski - Flying Saucers Farewell (1961)Dokument95 SeitenGeorge Adamski - Flying Saucers Farewell (1961)plowenshaw100% (11)

- Final RecipientsDokument144 SeitenFinal RecipientsSILVIA ROMERONoch keine Bewertungen

- Luis Valdez-Early Works: Actos, Bernabe and Pensamiento SerpentinoDokument202 SeitenLuis Valdez-Early Works: Actos, Bernabe and Pensamiento SerpentinoArte Público Press100% (6)

- HousingDokument60 SeitenHousingmunim100% (2)

- GR 4 My Social Studies NotebookDokument99 SeitenGR 4 My Social Studies NotebookMelrose AllicockNoch keine Bewertungen

- If You Forget Me by Pablo NerudaDokument1 SeiteIf You Forget Me by Pablo Nerudasbob255Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yet Not I But Through Christ in Me CDokument3 SeitenYet Not I But Through Christ in Me CEthan GilmoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macbeth Assignment 2017Dokument5 SeitenMacbeth Assignment 2017anastasiiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- El FilibusterismoDokument18 SeitenEl FilibusterismoHaidee PepitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The God Ninurta CHAPTER ONE Ninurtas RolDokument42 SeitenThe God Ninurta CHAPTER ONE Ninurtas Rol葛学斌Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ali Ibn Abu TalibDokument3 SeitenAli Ibn Abu TalibAreef OustaadNoch keine Bewertungen