Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Malignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and Anatomy

Hochgeladen von

CeriaindriasariOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Malignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and Anatomy

Hochgeladen von

CeriaindriasariCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This site is intended for healthcare professionals

Drugs & Diseases > Plastic Surgery

Malignant Parotid Tumors

Updated: May 18, 2017 | Author: Bardia Amirlak, MD; Chief

Editor: Deepak Narayan, MD, FRCS more...

SECTIONS

Introduction and Anatomy

The parotid glands are the largest salivary glands in

humans and are frequently involved in disease

processes. Approximately 25% of parotid masses are

nonneoplastic; the remaining 75% are neoplastic.

Nonneoplastic causes of parotid enlargement

include cysts, parotitis, lymphoepithelial lesions

associated with AIDS, collagen vascular diseases,

and benign hypertrophy. Benign hypertrophy is

encountered in patients with bulimia, sarcoidosis,

sialosis, actinomycosis infections, and mycobacterial

infections. The vast majority (approximately 80%) of

parotid neoplasms are benign; these are discussed

in detail in the Medscape Drugs & Diseases article

Benign Parotid Tumors.

The paired parotid glands are formed as epithelial

invaginations into the embryological mesoderm and

first appear at approximately 6 weeks gestation. The

glands are roughly pyramidal in shape, with the main

body overlying the masseter muscle.

The glands extend to the zygomatic process and

mastoid tip of the temporal bone and curve around

the angle of the mandible to extend to the

retromandibular and parapharyngeal spaces. The

parotid duct exits the gland medially, crosses the

superficial border of the masseter, pierces the

buccinator, and enters the oral cavity through the

buccal mucosa opposite the second maxillary molar.

The gland is divided into a superficial and deep

portion by the facial nerve, which passes through the

gland. While not truly anatomically discrete, these

"lobes" are important surgically, as neoplasms

involving the deep lobe require sometimes

significant manipulation of the facial nerve to allow

excision. The superficial lobe is the larger of the two

and thereby the location of the majority of parotid

tumors.

The facial nerve exits the cranium via the

stylomastoid foramen and courses through the

substance of the parotid gland. The superficial lobe

of the parotid lies superficial or lateral to the facial

nerve, whereas the deep lobe is deep or medial to

the facial nerve. The facial nerve branches within the

substance of the parotid gland, and the branching

pattern can be highly variable. The main trunk

typically bifurcates in to the zygomaticotemporal

branch and the cervicofacial branch at the pes

anserinus, also known as the goose’s foot (see

images below), and thereafter into the temporal,

zygomatic, buccal, marginal, and cervical branches.

Pes is about 1.3 cm from the stylomastoid foramen.

Extensive anastomoses are usually present between

branches of the zygomatic and buccal branches of

the nerve.

The (Z) zygomaticotemporal branch and the (C)

cervicofacial branch of the facial nerve are

dissected out during resection of a parotid

tumor. The pes (goose's foot) is visible in this

photograph.

View Media Gallery

The surgical anatomy and landmarks of the facial

nerve.

View Media Gallery

Numerous lymph nodes also are present within the

parotid gland itself, subsequently draining to

preauricular, infra-auricular, and deep upper jugular

nodes.

Diagnosis

Evaluation of a patient with a suspected parotid

gland malignancy must begin with a thorough

medical history and physical examination.

The most common presentation is a painless,

asymptomatic mass; >80% of patients present

because of a mass in the posterior cheek region.

Approximately 30% of patients describe pain

associated with the mass, though most parotid

malignancies are painless. Pain most likely indicates

perineural invasion, which greatly increases the

likelihood of malignancy in a patient with a parotid

mass.

Of patients with malignant parotid tumors, 7-20%

present with facial nerve weakness or paralysis,

which almost never accompanies benign lesions and

indicates a poor prognosis. Approximately 80% of

patients with facial nerve paralysis have nodal

metastasis at the time of diagnosis. These patients

have an average survival of 2.7 years and a 10-year

survival of 14-26%.

Other important aspects of the history include length

of time the mass has been present and history of

prior cutaneous lesion or parotid lesion excision.

Slow-growing masses of long-standing duration tend

to be benign. A history of prior squamous cell

carcinoma, malignant melanoma, or malignant

fibrous histiocytoma suggests intraglandular

metastasis or metastasis to parotid lymph nodes.

Prior parotid tumor most likely indicates a recurrence

because of inadequate initial resection.

Trismus often indicates advanced disease with

extension into the masticatory muscles or, less

commonly, invasion of the temporomandibular joint.

Dysphagia or a sensation of a foreign body in the

oropharynx indicates a tumor of the deep lobe of the

gland. A report of ear pain may indicate extension of

the tumor into the auditory canal. The presence of

numbness in the distribution of the second or third

divisions of the trigeminal nerve often indicates

neural invasion.

Physical examination of the head and neck must be

thorough and complete. The entire head and neck

must be examined for cutaneous lesions, which may

represent malignancies that could metastasize to the

parotid gland or parotid nodes.

Palpation of the mass should determine the

degree of firmness. Even benign tumors are

usually firm, but a rock-hard mass generally

denotes malignancy.

Skin fixation, skin ulceration, or fixation to

adjacent structures also indicates malignancy.

The external auditory canal must be visualized

for tumor extension.

All regional nodes must be carefully palpated to

detect nodal metastasis. Examination of the oral

cavity and oropharynx also may yield further

evidence of metastasis or malignant nature of

the lesion.

Blood or pus from the Stenson duct is a sign of

malignancy but is infrequently encountered.

More often, one may see bulging of the lateral

pharyngeal wall or soft palate, indicating tumor

in the deep lobe of the gland.

Bimanual palpation with one finger against the

lateral pharyngeal wall and the other against

the external neck may confirm extent into the

tonsillar fossa and soft palate.

Once a thorough history and physical examination

are complete, perform diagnostic procedures to

confirm the diagnosis and extent of the disease

process.

Fine needle aspiration

See the list below:

Fine needle aspiration of the mass or an

enlarged lymph node may be performed to

obtain a tissue diagnosis. [1] Most surgeons

recommend excision of a parotid mass whether

it is benign or malignant unless a patient's

comorbidity precludes safe surgery. As such,

many surgeons do not routinely perform

cytology before proceeding with surgery.

The sensitivity of this procedure is greater than

95% in experienced hands. However, only a

positive diagnosis should be accepted;

negative results indicate the need for further

attempts at obtaining a histologic diagnosis,

including repeat fine needle aspiration.

The results of the fine needle aspiration provide

a histologic diagnosis and assist in preoperative

planning and patient counseling. It may not

distinguish benign from malignant epithelial

lesions because malignancy of parotid epithelial

cells is related to the behavior of the tumor cells

in relation to tissue planes and surrounding

structures rather than cellular architecture,

which may be rather normal even in malignancy.

Therefore, nonepithelial lesions may be

diagnosed with accuracy, but epithelial lesions

may require further investigation.

If fine needle aspiration is unsuccessful in

obtaining a diagnosis, an incisional biopsy

should not be performed. This procedure has a

high rate of local recurrence and places the

facial nerve at risk for injury from inadequate

visualization.

Some authors advocate large core needle

biopsies, but this procedure is less popular

because of potential facial nerve injury and the

possibility of seeding the needle tract with

tumor cells.

If a core biopsy is performed, the needle should

be inserted so that the tract may be excised

during the definitive operation. When all

attempts at obtaining a histologic diagnosis

have failed, operative exploration should

proceed after appropriate imaging studies have

been obtained.

Intraoperatively, a frozen section of the

specimen should be submitted for diagnosis.

The use of frozen sections has demonstrated

greater than 93% accuracy in the diagnosis of

parotid malignancy.

Imaging studies

Imaging studies may be helpful in staging and for

surgical planning. Sialography may help to

differentiate inflammatory versus neoplastic

processes, but this test is infrequently performed and

is of limited value in the evaluation of parotid

masses. It is mentioned herein for historic interest

only.

Sonography may be very useful. Benign lesions are

of lower density and have smaller caliber blood

vessels. However, determination of a cystic

component may be misleading, because cystic

degeneration may occur as a result of necrosis at the

avascular center of a malignancy.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) [2] can be valuable for

evaluation of parotid malignancies. CT scanning

provides better detail of the surrounding tissues,

whereas MRI demonstrates the mass in greater

contrast than a CT scan.

These imaging studies may identify regional lymph

node involvement or extension of the tumor into the

deep lobe or parapharyngeal space. CT scan criteria

for lymph node metastasis include any lymph node

larger than 1-1.5 cm in greatest diameter, multiple

enlarged nodes, and nodes displaying central

necrosis.

Lymph nodes harboring metastasis also may appear

round rather than the normal kidney bean shape, and

evidence of extracapsular extension may be

identified.

A study by Mamlouk et al of pediatric patients with

parotid neoplasms indicated that on MRI scans, the

presence of a hypointense T2 signal, restricted

diffusion, poorly defined borders, and focal necrosis

are suggestive of malignancy, although not specific

for it. The study involved 17 patients, including 11 with

malignant tumors and six with benign neoplasms. [3]

For more information on imaging studies for

malignant parotid tumors, see Medscape Drugs &

Diseases article Malignant Parotid Tumor Imaging.

Pathology

Many types of parotid malignancies exist, most

arising from the epithelial elements of the gland. [4, 5,

6, 7, 8] Classification of these tumors can be quite

confusing. In addition, malignancy may develop in

the secretory element of the gland or malignancy

arising elsewhere may first be noticed as a

metastasis to the gland.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common

malignant tumor of the parotid gland, accounting for

30% of parotid malignancies. [9, 10]

Three cell types are found in varying proportions:

mucous, intermediate, and epidermoid cells. High-

grade tumors exhibit cytologic atypia, higher mitotic

frequency, areas of necrosis and more epidermoid

cells. High-grade tumors behave like a squamous

cell carcinoma; low-grade tumors often behave

similar to a benign lesion. [11]

Limited local invasiveness and low metastatic

potential characterize this tumor, particularly when

cytologically low-grade. If metastatic, it is most likely

to metastasize to regional nodal basins rather than to

distant locations.

For patients with low-grade tumors without nodal or

distant metastasis, 5-year survival is 75-95%,

whereas patients with high-grade tumors with lymph

node metastasis at the time of diagnosis have a 5-

year survival of only 5%. Overall 10-year survival is

50%.

Differential diagnosis includes chronic sialoadenitis,

necrotizing sialometaplasia, and other carcinomas.

An association has been reported between

mucoepidermoid carcinoma and myasthenia gravis.

[12]

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

The adenoid cystic carcinoma is characterized by its

unpredictable behavior and propensity to spread

along nerves. It possesses a highly invasive quality

but may remain quiescent for a long time.

This tumor may be present for more than 10 years

and demonstrate little change and then suddenly

infiltrate the adjacent tissues extensively.

The tumor has an affinity for growth along perineural

planes and may demonstrate skip lesions along

involved nerves. Clear margins do not necessarily

mean that the tumor has been eradicated.

Metastasis is more common to distant sites than to

regional nodes; lung metastases are most frequent.

This tumor has the highest incidence of distant

metastasis, occurring in 30-50% of patients.

Three histologic types have been identified: cribrose,

tubular, and solid. The solid form has the worst

prognosis; the cribrose pattern possesses the most

benign behavior and best prognosis. This tumor

requires aggressive initial resection. Overall 5-year

survival is 35%, and 10-year survival is approximately

20%.

Malignant mixed tumors

Malignant mixed tumors arise most commonly as a

focus of malignant degeneration within a preexisting

benign pleomorphic adenoma (carcinoma ex

pleomorphic adenoma).

These tumors also may develop de novo

(carcinosarcoma). The longer pleomorphic adenoma

has been present, the greater the chance of

carcinomatous degeneration.

Carcinosarcomas, true malignant mixed tumors, are

rare. Overall 5-year survival is 56%, and 10-year

survival is 31%.

Acinic cell carcinoma

Acinic cell carcinoma is an intermediate-grade

malignancy with low malignant potential. This tumor

may be bilateral or multicentric and is usually solid,

rarely cystic.

Although this tumor rarely metastasizes, occasional

late distant metastases have been observed. This

tumor also may spread along perineural planes.

Overall 5-year survival is 82%, and 10-year survival is

68%.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma of the parotid develops from the

secretory element of the gland. This is an aggressive

lesion with potential for both local lymphatic and

distant metastases.

Approximately 33% of patients have nodal or distant

metastasis present at the time of initial diagnosis.

Overall 5-year survival is 19-75%, as it is highly

variable and related to grade and stage at

presentation.

A study by Zhan and Lentsch of basal cell

adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands (509

cases) found that 88% of tumors were in the parotid

glands, with 11.2% in the submandibular glands and

0.8% being sublingual gland lesions. Overall 5- and

10-year survival rates were 79% and 62%,

respectively, while regional and distant metastases

occurred in just 11.9% and 1.8% of cases, respectively.

Older age (65 years or older) and high primary tumor

stage had a significant negative impact on survival; in

patients with a high tumor stage, the survival rate

was significantly better with a combination of surgery

and radiation therapy than with surgery alone. [13]

Primary squamous cell carcinoma

Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid is

rare, and metastasis from other sites must be

excluded. Overall 5-year survival is 21-55%, and 10-

year survival is 10-15%.

Sebaceous carcinoma

Sebaceous carcinoma is a rare parotid malignancy

that often presents as a painful mass. It commonly

involves the overlying skin.

Salivary duct carcinoma

Salivary duct carcinoma is a rare and highly

aggressive tumor. Small cell carcinoma exists as 2

types. The ductal cell origin type is mostly benign

and rarely metastasizes. The neuroendocrine origin

type is often aggressive and has higher metastatic

potential.

Lymphoma

The parotid gland also may be the site of occurrence

of lymphoma, most commonly in elderly males. This

is also observed in approximately 5-10% of patients

with Warthin tumor of the parotid gland, a benign

neoplasm. [14]

The entire parotid is typically enlarged with a rubbery

consistency on palpation. Often, regional nodes also

are enlarged. Biopsy of enlarged regional nodes

avoids unnecessary parotid surgery, as the definitive

treatment consists of chemotherapy or radiation

therapy.

Malignant fibrohistiocytoma

Malignant fibrohistiocytoma is very rare in the parotid

gland. It presents as a slow growing and painless

mass.

Fine needle aspiration and imaging could confuse

this lesion with other kinds of parotid tumors;

therefore, definite diagnosis should be based on

immunohistochemical analysis of the resected tumor.

The tumor should be completely resected. [15]

Parotid metastasis from other sites

The parotid also may be the site of metastasis from

cutaneous, renal, lung, breast, prostate, or GI tract

malignancies.

Operative Management

Generally, therapy for parotid malignancy is complete

surgical resection followed, when indicated, by

radiation therapy. [16] Conservative excisions are

plagued by a high rate of local recurrence. The

extent of resection is based on tumor histology,

tumor size and location, invasion of local structures,

and the status of regional nodal basins.

Most tumors of the parotid (approximately 90%)

originate in the superficial lobe. Superficial parotid

lobectomy is the minimum operation performed in

this situation. This procedure is appropriate for

malignancies confined to the superficial lobe, those

that are low grade, those less than 4 cm in greatest

diameter, tumors without local invasion, and those

without evidence of regional node involvement.

Surgical resection procedure

The most important initial step is identification of the

facial nerve and its course through the substance of

the parotid gland. In order to preserve the facial

nerve, it is important to try to determine the proximity

of the nerve to the capsule of the tumor prior to

surgery. Results of a retrospective review showed

that malignant tumors were likely to have a positive

facial nerve margin. [17] Virtually all surgeons avoid

using paralytic agents, and, to assist finding the

nerve, many surgeons use a nerve stimulator.

Increasingly, surgeons are using intraoperative

continuous facial nerve monitoring any time a

parotidectomy is performed. This is not usually

necessary in the primary setting, but recurrent

resections may be very difficult and probably should

be performed using this device.

Ideally, the dissection of the facial nerve should

be performed without disturbing or violating the

tumor. The facial nerve may be found exiting

the stylomastoid foramen by reflecting the

parotid gland anteriorly and the

sternocleidomastoid muscle posteriorly.

Landmarks include the digastric ridge and the

tympanomastoid suture. Knowledge of the

relationships among these structures allows

more efficient and reproducible identification of

the nerve.

The cartilaginous external auditory canal lies

approximately 5 mm superior to the facial nerve

in this region. The facial nerve is also anterior to

the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and

external to the styloid process.

A second technique for locating the facial nerve

is to identify a distal branch of the nerve and to

dissect retrograde toward the main trunk. This

technique may be more difficult depending on

the ease of identifying the branching pattern. To

perform this maneuver, the buccal branch may

be found just superior to the parotid duct, or the

marginal mandibular branch may be found

crossing over (superficial to) the facial vessels.

These may then be traced back to the origins of

the main facial nerve trunks.

A final way of identifying the nerve in

particularly difficult situations is to drill the

mastoid and to locate the nerve within the

temporal bone. It may then be followed through

the stylomastoid foramen antegrade towards

the parotid.

Once these have been identified, the superficial

lobe of the parotid gland may be removed en

bloc and sent to the pathology laboratory.

If the immediate intraoperative pathologic

examination reveals that the tumor is actually

high-grade or >4 cm in greatest diameter, or

lymph node metastasis is identified within the

specimen, a complete total parotidectomy

should be performed.

If the facial nerve or its branches are adherent

to or directly involved by the tumor, they must

be sacrificed. However, a pathologic diagnosis

of malignancy must be confirmed

intraoperatively prior to sacrificing facial nerve

branches.

All involved local structures should be resected

in continuity with the tumor. This may include

skin, masseter, mandible, temporalis, zygomatic

arch, or temporal bone.

Tumors of the deep lobe are treated by total

parotidectomy. Identification of the facial nerves

and branches is the first and most crucial step.

Total parotidectomy is then performed en bloc,

and the fate of the facial nerve and surrounding

local structures must be decided similar to

superficial lobe tumors. The specimen should

be sent to the pathology laboratory for

immediate examination.

Neck dissection should be performed when

malignancy is detected in the lymph nodes pre-

or intraoperatively.

Other indications for functional neck dissection

include tumors >4 cm in greatest diameter,

tumors that are high-grade, tumors that have

invaded local structures, recurrent tumors when

no neck dissection was performed initially, and

deep lobe tumors.

These recommendations are based on the

higher likelihood of occult, clinically

undetectable nodal disease present at the time

of operation in patients whose tumors display

the above characteristics.

Reconstruction

Following resection of the tumor specimen, most

wounds can be closed primarily. However, the

presence of extension of the tumor to the overlying

skin or surrounding structures may require

reconstructive procedures. The overall goal following

tumor excision is to restore function and achieve the

best possible aesthetic result.

Options for wound closure in the presence of a skin

or soft tissue deficit include skin grafting,

cervicofacial flap, trapezius flap, pectoralis flap,

deltopectoral flap, and microvascular free flap. For

information on various flap procedures, see the Flaps

section of the Medscape Drugs & Diseases Plastic

Surgery journal.

Sacrifice of the facial nerve or one of its branches

also must be managed appropriately. If inadvertently

severed during the operation, the facial nerve should

be immediately repaired under the operating

microscope. If intentionally resected with the tumor

specimen, several options for reconstruction are

available to the surgeon.

The ipsilateral or contralateral great auricular

nerve may be used as an interposition graft,

although this sacrifices sensation to the area

normally supplied by this nerve.

Another option is to anastomose the facial

nerve to the ipsilateral hypoglossal nerve. This

anastomosis may be performed end-to-side to

avoid interfering with normal hypoglossal nerve

function.

During the period of waiting for facial nerve

recovery, maintain corneal protection if the

innervation to the orbicularis oculi has been

interrupted.

Measures include taping the eye closed at night

over ophthalmic ointment and frequent use of

wetting drops during the day. Some authors

recommend a moisture chamber.

If facial nerve recovery is not achieved, certain

measures may be taken to improve form and

function.

A gold weight (0.8-1.2 g) may be inserted in the

upper eyelid to assist with closure. Dynamic

slings of temporalis muscle to the upper and

lower lids and corner of the mouth or masseter

sling to the mouth have proven very successful

in the reconstruction of these patients. Static

slings also have been used and include fascia

lata, tendon, and Mitek anchors.

Following parotidectomy, some patients

develop gustatory sweating or Frey syndrome.

[18] This denotes an aberrant connection of

regenerating parasympathetic salivary fibers to

the sweat glands in the overlying skin flap.

Treatment of this condition has included

irradiation, atropinelike creams, division of the

auriculotemporal nerve (sensory), division of the

glossopharyngeal nerve (parasympathetic),

insertion of synthetic materials (AlloDerm),

fascial grafts, or vascularized tissue flaps

between the parotid bed and overlying skin

flap. Intracutaneous injections of botulinum

toxin A is also an attractive option which has

showed some promise.

Finally, neurovascular free tissue transfer has been

described for facial reanimation for treatment of

established facial paralysis following ablative parotid

surgery. [19]

Vascularized nerve grafts, such as sural nerve

graft, have been described to reestablish facial

nerve continuity.

Functional free muscle transfer with gracilis,

pectoralis minor, or latissimus dorsi muscles are

further options for reconstruction. The ipsilateral

facial nerve stump may be used as the recipient

nerve.

Alternatively, cross facial nerve grafting can be

performed. This is typically performed as a 2-

stage surgery, with anastomosis to a nerve graft

as the first stage and free tissue transfer as the

second stage.

For more information on facial nerve reconstruction

and the treatment of facial nerve paralysis, see the

Medscape Drugs & Diseases articles Facial Nerve

Paralysis, Dynamic Reconstruction for Facial Nerve

Paralysis, and Static Reconstruction for Facial Nerve

Paralysis.

Adjunctive Therapy

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Salivary Gland Cancer: From Diagnosis to Tailored TreatmentVon EverandSalivary Gland Cancer: From Diagnosis to Tailored TreatmentLisa LicitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Surgical Oncology Review: For the Absite and BoardsVon EverandThe Surgical Oncology Review: For the Absite and BoardsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Neck DissectionDokument9 Seiten6 Neck DissectionAnne MarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- SurgeryDokument47 SeitenSurgerymohamed muhsinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotid MassDokument9 SeitenParotid MassAndre Eka Putra PrakosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solitary Nodules Are Most Likely To Be Malignant in Patients Older Than 60 Years and in Patients Younger Than 30 YearsDokument5 SeitenSolitary Nodules Are Most Likely To Be Malignant in Patients Older Than 60 Years and in Patients Younger Than 30 YearsAbdurrahman Afa HaridhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Patologi AnatomiDokument5 SeitenJurnal Patologi Anatomiafiqzakieilhami11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grand Rounds Index UTMB Otolaryngology Home PageDokument9 SeitenGrand Rounds Index UTMB Otolaryngology Home PageandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotidectomy StatPearls NCBIBookshelfDokument16 SeitenParotidectomy StatPearls NCBIBookshelfshehla khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50315-72475-1-PB (1) Parotid TumorDokument3 Seiten50315-72475-1-PB (1) Parotid TumorShashank MisraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recurrent Salivary Gland CancerDokument13 SeitenRecurrent Salivary Gland CancerestantevirtualdosmeuslivrosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biopsy in Oral SurgeryDokument45 SeitenBiopsy in Oral SurgeryMahamoud IsmailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salivary Gland MalignanciesDokument13 SeitenSalivary Gland MalignanciesestantevirtualdosmeuslivrosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hemangiopericytoma of Palate A Rare Case ReportDokument4 SeitenHemangiopericytoma of Palate A Rare Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2006 89 Canine and Feline Nasal NeoplasiaDokument6 Seiten2006 89 Canine and Feline Nasal NeoplasiaFelipe Guajardo HeitzerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Normal Mediastinal Anatomy, Pathologies and Diagnostic MethodsDokument9 SeitenNormal Mediastinal Anatomy, Pathologies and Diagnostic MethodsJuma AwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adult Neck MassesDokument7 SeitenAdult Neck MassesHanhan90Noch keine Bewertungen

- Solitary Pulmonary Nodule (SPN (Dokument59 SeitenSolitary Pulmonary Nodule (SPN (mahmod omerNoch keine Bewertungen

- August 2013 Ophthalmic PearlsDokument3 SeitenAugust 2013 Ophthalmic PearlsEdi Saputra SNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABC - Oral CancerDokument4 SeitenABC - Oral Cancerdewishinta12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma (JNA)Dokument19 SeitenJuvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma (JNA)YogiHadityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Management of Soft Tissue SarcomaDokument33 SeitenPrinciples of Management of Soft Tissue Sarcomabashiruaminu100% (1)

- Cerebellopontine Angle TumoursDokument11 SeitenCerebellopontine Angle TumoursIsmail Sholeh Bahrun MakkaratteNoch keine Bewertungen

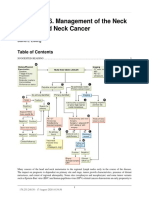

- Chapter 146. Management of The Neck in Head and Neck Cancer: David E EiblingDokument3 SeitenChapter 146. Management of The Neck in Head and Neck Cancer: David E EiblingYasin KulaksızNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article Imaging of Salivary Gland TumoursDokument11 SeitenArticle Imaging of Salivary Gland TumourskaryndpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soft Tissue Tumors of The Neck: David E. Webb, DDS, Brent B. Ward, DDS, MDDokument15 SeitenSoft Tissue Tumors of The Neck: David E. Webb, DDS, Brent B. Ward, DDS, MDCynthia BarrientosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Essentials: View Media GalleryDokument8 SeitenPractice Essentials: View Media GallerywzlNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Evaluation and Management of Neck Masses of Unknown EtiologyDokument38 SeitenThe Evaluation and Management of Neck Masses of Unknown EtiologyShaxawan Mahmood AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retro Peritoneal TumorDokument37 SeitenRetro Peritoneal TumorHafizur RashidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salivary Gland MalignanciesDokument69 SeitenSalivary Gland MalignanciesKessi VikaneswariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simultaneous Papillary Carcinoma in Thyroglossal Duct Cyst and ThyroidDokument5 SeitenSimultaneous Papillary Carcinoma in Thyroglossal Duct Cyst and ThyroidOncologiaGonzalezBrenes Gonzalez BrenesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Current Controversies in The Management of Malignant Parotid TumorsDokument8 SeitenCurrent Controversies in The Management of Malignant Parotid TumorsDirga Rasyidin LNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2009 0527 rs.1 PDFDokument5 Seiten2009 0527 rs.1 PDFpaolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Primary Testicular Tumor: Alireza Ghoreifi,, Hooman DjaladatDokument7 SeitenManagement of Primary Testicular Tumor: Alireza Ghoreifi,, Hooman DjaladatfelipeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Hard Palate: A Case ReportDokument5 SeitenAdenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Hard Palate: A Case ReportHemant GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CR Pa 2 PDFDokument4 SeitenCR Pa 2 PDFmitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Usg2Dokument6 SeitenThe Role of Usg2noorhadi.n10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Neck Mass ProtocolDokument8 SeitenNeck Mass ProtocolCharlene FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- ScriptDokument8 SeitenScriptChristian Edward MacabaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotid Gland NeoplasmDokument107 SeitenParotid Gland NeoplasmigorNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 OP Techniques General Surgery Superficial Parotidectomy OLSEN EXCELLENTDokument13 Seiten0 OP Techniques General Surgery Superficial Parotidectomy OLSEN EXCELLENTmuhammad ishaqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- HN 08-2005 Surgical Management of ParapharyngealDokument7 SeitenHN 08-2005 Surgical Management of ParapharyngealJosinaldo ReisNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Rare Huge Myxofibrosarcoma of Chest WallDokument3 SeitenA Rare Huge Myxofibrosarcoma of Chest WallIOSRjournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2010 Article 73Dokument12 Seiten2010 Article 73Abhilash AntonyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carcinoma Maxillary Sinus : of TheDokument6 SeitenCarcinoma Maxillary Sinus : of TheInesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salivary Gland Tumors: 1. AdenomasDokument18 SeitenSalivary Gland Tumors: 1. AdenomasMahammed Ahmed BadrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotidectomia - UpToDate 2022Dokument2 SeitenParotidectomia - UpToDate 2022juanrangoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric Desmoid Fibromatosis of TheDokument4 SeitenPediatric Desmoid Fibromatosis of ThevatankhahpooyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Large CystDokument4 SeitenLarge CystKin DacikinukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reti No Blast OmaDokument54 SeitenReti No Blast OmaSaviana Tieku100% (1)

- The Patient With Thyroid Nodule. Med Clin of NA. 2010Dokument13 SeitenThe Patient With Thyroid Nodule. Med Clin of NA. 2010pruebaprueba321765Noch keine Bewertungen

- Brain Abscess MimicsDokument16 SeitenBrain Abscess MimicsRikizu HobbiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salivary Gland Tumours and Other Lesions BDS 4Dokument38 SeitenSalivary Gland Tumours and Other Lesions BDS 4dunisanijamesonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary Management of Parapharyngeal TumorsDokument5 SeitenContemporary Management of Parapharyngeal TumorsSilvia SoareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Implications of The Neck in Salivary Gland DiseaseDokument14 SeitenClinical Implications of The Neck in Salivary Gland DiseaseГулпе АлексейNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primary Chest Wall TumorsDokument13 SeitenPrimary Chest Wall Tumorsmhany12345Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cranio Pha Ryn Gio MaDokument3 SeitenCranio Pha Ryn Gio MaSerious LeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meningioma: Tengku Rizky Aditya, MDDokument30 SeitenMeningioma: Tengku Rizky Aditya, MDTengku Rizky AdityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Studies in Advanced Skin Cancer Management: An Osce Viva ResourceVon EverandCase Studies in Advanced Skin Cancer Management: An Osce Viva ResourceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atlas of Diagnostically Challenging Melanocytic NeoplasmsVon EverandAtlas of Diagnostically Challenging Melanocytic NeoplasmsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 24 Jul 2018 01.13 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 24 Jul 2018 01.13 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 31 Des 2018 16.12 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 31 Des 2018 16.12 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 25 Agt 2018 01.38 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 25 Agt 2018 01.38 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Salivary Gland Tumours: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary GuidelinesDokument8 SeitenManagement of Salivary Gland Tumours: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary GuidelinesCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and AnatomyDokument1 SeiteMalignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and AnatomyCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 21 Agt 2018 18.00 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 21 Agt 2018 18.00 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Otorhinolaryngology: Parotid Gland Tumors: A Retrospective Study of 154 PatientsDokument6 SeitenOtorhinolaryngology: Parotid Gland Tumors: A Retrospective Study of 154 PatientsCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 21 Agt 2018 18.00 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 21 Agt 2018 18.00 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Haruskah Diterminas Dengan Bedah SesarDokument1 SeiteHaruskah Diterminas Dengan Bedah SesarCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 25 Agt 2018 01.38 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 25 Agt 2018 01.38 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Usg in Ra Anaesthesia 2010Dokument12 SeitenUsg in Ra Anaesthesia 2010Ivette M. Carroll D.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 25 Agt 2018 01.38 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 25 Agt 2018 01.38 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- c1 PDFDokument16 Seitenc1 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ebook Mata PDFDokument189 SeitenEbook Mata PDFepingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Otorhinolaryngology: Parotid Gland Tumors: A Retrospective Study of 154 PatientsDokument6 SeitenOtorhinolaryngology: Parotid Gland Tumors: A Retrospective Study of 154 PatientsCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotid Glands Tumours: Overview of A 10-Years Experience With 282 Patients, Focusing On 231 Benign Epithelial NeoplasmsDokument5 SeitenParotid Glands Tumours: Overview of A 10-Years Experience With 282 Patients, Focusing On 231 Benign Epithelial NeoplasmsCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotid Mass PDFDokument9 SeitenParotid Mass PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotid Mass PDFDokument9 SeitenParotid Mass PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- c1 PDFDokument16 Seitenc1 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Otorhinolaryngology: Parotid Gland Tumors: A Retrospective Study of 154 PatientsDokument6 SeitenOtorhinolaryngology: Parotid Gland Tumors: A Retrospective Study of 154 PatientsCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 2 Sep 2018 11.27 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotid Glands Tumours: Overview of A 10-Years Experience With 282 Patients, Focusing On 231 Benign Epithelial NeoplasmsDokument5 SeitenParotid Glands Tumours: Overview of A 10-Years Experience With 282 Patients, Focusing On 231 Benign Epithelial NeoplasmsCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bupivacaine: Review: Charles R. D. D. S. Bert N. M.D. Medical Center, Honolulu, HawaiiDokument5 SeitenBupivacaine: Review: Charles R. D. D. S. Bert N. M.D. Medical Center, Honolulu, HawaiiCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgery v6n1p1 en PDFDokument5 SeitenSurgery v6n1p1 en PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safari - 21 Agt 2018 18.00 PDFDokument1 SeiteSafari - 21 Agt 2018 18.00 PDFCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bupivacaine: Review: Charles R. D. D. S. Bert N. M.D. Medical Center, Honolulu, HawaiiDokument5 SeitenBupivacaine: Review: Charles R. D. D. S. Bert N. M.D. Medical Center, Honolulu, HawaiiCeriaindriasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final SBFR Training PPT 19th April 2022 MoHDokument113 SeitenFinal SBFR Training PPT 19th April 2022 MoHDaniel Firomsa100% (6)

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Paket C Setara SMA/MADokument22 SeitenSoal Bahasa Inggris Paket C Setara SMA/MApkbmalhikmah sukodonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mine ScoreDokument7 SeitenMine ScoreCharlys RhandsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challenges Faced by Roma Women in EuropeDokument29 SeitenChallenges Faced by Roma Women in EuropeaurimiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specific Groups EssayDokument1 SeiteSpecific Groups Essaysunilvajshi2873Noch keine Bewertungen

- Iv PrimingDokument16 SeitenIv PrimingZahra jane A.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Special Power of Attorney Chavez 1Dokument2 SeitenSpecial Power of Attorney Chavez 1Atty. R. PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational TheoryDokument5 SeitenEducational TheoryTejinder SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13 Reasons Why Character DiagnosisDokument9 Seiten13 Reasons Why Character DiagnosisVutagwa JaysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 MSDS BentoniteDokument5 Seiten03 MSDS BentoniteFurqan SiddiquiNoch keine Bewertungen

- OSSSC Diploma in Pharmacy..Dokument8 SeitenOSSSC Diploma in Pharmacy..RAJANI SathuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Health Nursing ExamDokument24 SeitenCommunity Health Nursing ExamClarisse SampangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrical Engineering Dissertation SampleDokument4 SeitenElectrical Engineering Dissertation SampleInstantPaperWriterUK100% (1)

- 1 5 4 Diabetes Mellitus - PDF 2Dokument6 Seiten1 5 4 Diabetes Mellitus - PDF 2Maica LectanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PRACTICAL RESEARCH Q2-W1.editedDokument3 SeitenPRACTICAL RESEARCH Q2-W1.editedRAEJEHL TIMCANGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Admission List of Students To Government Health Training CollegesDokument298 SeitenFinal Admission List of Students To Government Health Training CollegesThe New VisionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wcms - 618575 31 70 28 34Dokument7 SeitenWcms - 618575 31 70 28 34alin grecuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Common Medical AbbreviationsDokument1 SeiteCommon Medical Abbreviationskedwards108Noch keine Bewertungen

- Diass 2ndsem Q2.GDokument8 SeitenDiass 2ndsem Q2.GJohn nhel SinonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Question Text: Clear My ChoiceDokument13 SeitenQuestion Text: Clear My ChoiceLylibette Anne H. CalimlimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Your Clinic Name Here: Feline Acute Pain Scale Canine Acute Pain ScaleDokument1 SeiteYour Clinic Name Here: Feline Acute Pain Scale Canine Acute Pain ScalevetthamilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Make Today Amazing Checklist Printable Guide PDFDokument5 SeitenMake Today Amazing Checklist Printable Guide PDFemna fadliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Archery Tips-Home Training - WAEC - TEC-PHY - ENG - V1 - 0 PDFDokument44 SeitenArchery Tips-Home Training - WAEC - TEC-PHY - ENG - V1 - 0 PDFjenny12Noch keine Bewertungen

- NAMS 2022 Hormone-Therapy-Position-StatementDokument28 SeitenNAMS 2022 Hormone-Therapy-Position-StatementPaul PIETTENoch keine Bewertungen

- Aesthetic Inlays: November 2011Dokument4 SeitenAesthetic Inlays: November 2011Diego SarunNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCP Blurred VisionDokument3 SeitenNCP Blurred VisionRM MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compensation & Reward ManagementDokument227 SeitenCompensation & Reward ManagementjitendersharmajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ingles 2018Dokument12 SeitenIngles 2018Carmen GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tired Swimmer: A Case StudyDokument4 SeitenTired Swimmer: A Case StudyMorgan KrauseNoch keine Bewertungen

- GEN 013 Day 02 SASDokument5 SeitenGEN 013 Day 02 SASAlbert King CambaNoch keine Bewertungen