Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Brower-They'd Kill Us If They Knew" Transgression and The Wester

Hochgeladen von

A Guzmán MazaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Brower-They'd Kill Us If They Knew" Transgression and The Wester

Hochgeladen von

A Guzmán MazaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

"They'd Kill Us if They Knew": Transgression and the Western1

Sue Brower

Journal of Film and Video, Volume 62, Number 4, Winter 2010,

pp. 47-57 (Article)

Published by University of Illinois Press

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jfv/summary/v062/62.4.brower.html

Access Provided by Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona at 01/25/11 3:38PM GMT

“They’d Kill Us if They Knew”: Transgression and the Western1

sue brower

a film that touched audiences with its Problematic Heroes (or, Who’re You

epic tale set in the West, Ang Lee’s Brokeback Callin’ a Cowboy?)

Mountain (2005) tells the story of hidden ho-

mosexual love, beginning in 1963 in the Wyo- Despite an increasingly cynical, media-wise

ming wilderness and spanning the next twenty audience that can spot and often dismiss es-

years. The film’s use of the Western genre in tablished generic icons, the Western archetype

its setting and iconography intensifies the lov- of the cowboy still possesses power as a sym-

ers’ transgression by juxtaposing the mythic bol of American courage, strength, capability,

roots of our country and the masculine arche- and masculinity. The Western figure continues

type of the cowboy with a taboo love affair—a to inhabit popular culture, from the Marlboro

combination, as critics have noted, resulting man to President George W. Bush’s references

in a film closer to melodrama than Western to Western mythology (e.g., “we’re gonna

(Kitses “All That”; Osterweil). A smaller film smoke ’em out”) to the recent flurry of Western

released in 1993, The Ballad of Little Jo, writ- films, including Appaloosa (2008) and 3:10 to

ten and directed by Maggie Greenwald, is a Yuma (2007). The Western protagonist’s identi-

tale set in the West (the old West) that also fication with masculinity, in contrast to Eastern

features social and sexual transgressions, femininity, goes unchallenged unless that chal-

including at least two taboo love stories. Both lenge becomes the point of characterization.

films also illuminate the lives of marginalized James Stewart in Destry Rides Again (1939),

people. My intention is to explore the filmmak- for example, is initially presented as less than

ers’ use of the Western genre in telling these a “real man” by his entry into town carrying a

stories and to consider how in each case they birdcage and a parasol. As Dennis Bingham

blend the Western with other genres. I hope to points out, what is seen as “‘sissified’ to the

show The Ballad of Little Jo deserves as much townspeople” proves to be an act of “chivalry”

recognition as Brokeback has garnered, or to a young woman he is assisting (47). In My

more, for the former’s critique of gender and Darling Clementine (1946), Wyatt is challenged

racial stereotypes, its examination of gender- by Doc Holliday to “draw,” and Wyatt mildly

based assumptions on which the Western is declines (“Can’t—not wearing a gun”) without

largely based, and its generic response to the sacrificing masculine pride because of the well-

theme of transgression that results in blend- established reputation of Wyatt Earp, within

ing the Western not with melodrama but with both the film and American culture. The sub-

comedy. tlety and irony of these characterizations are

cast aside by the extreme violence of Clint East-

sue brower teaches film and media studies in wood’s Western protagonists in Leone’s films of

the Department of Theater Arts at Portland State the 1960s and many of Eastwood’s subsequent

University. films made with Don Siegel or under his own

journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010 47

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

direction. Eastwood’s (perhaps) final Western, when Wyatt Earp in My Darling Clementine

Unforgiven (1992), offers a stark comment on introduces himself and his brothers as “cattle-

the hideous obligations of an individual assum- men” rather than “cowboys.” In her essay

ing the role of masculine protector/avenger. about the adaptation of her short story to the

These characters are Western heroes or antihe- film of Brokeback Mountain, Annie Proulx notes

roes, but they are not cowboys. that both of the main characters aspire “to be

In films since the 1960s, there has been a cowboys, be part of the Great Western Myth,”

self-conscious use of the term; indeed, “cow- with Jack Twist ( Jake Gyllenhaal) settling for

boy” has taken on a theatrical, artificial, camp, rodeo “as an expression of cowboy” and Ennis

and/or homosexual connotation. Ara Osterweil del Mar (Heath Ledger) toiling away as a mere

identifies both Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cow- ranch hand. In their transformative summer on

boys (1967) and John Schlesinger’s Midnight the mountain, however, they tend sheep, “ani-

Cowboy (1969) as precursors to Brokeback mals most real cowpokes despise”; moreover,

Mountain (39–40).2 “Cowboy” has become a she writes, “the word ‘cowboy’ is often used

signifier of an ironic twentieth-century (and now derisively in the west by those who do ranch

twenty-first-century) perspective on the genre’s work” (“Getting Movied” 130). By identifying

tradition as it has been commercialized, such as with and being identified as “cowboys,” Jack

The Electric Horseman’s (1979) has-been rodeo and Ennis are already out of the mainstream.

champion, repeatedly called a “cowboy,” cor- In Proulx’s short story, the word “cowboy”

nered into selling breakfast cereal, or the term is does not appear until nearly the end: Jack

trivialized, as with John Travolta’s turn on a me- recalls a moment years earlier in his relation-

chanical bull in Urban Cowboy (1980). In Mid- ship with Ennis, when the two young men had

night Cowboy the term is literally prostituted. shared an embrace while they stood, Ennis

In their allusions to the Western genre, holding Jack, rocking him as they gazed into the

Brokeback Mountain and Ballad of Little Jo offer fire, lulling Jack into a doze, “until Ennis, dredg-

a host of mythic associations and cultural refer- ing up a rusty but still useable phrase from the

ences to the Western and its protagonist. In the childhood time before his mother died, said,

case of Brokeback, the term “cowboy” is used ‘Time to hit the hay, cowboy . . .’” (“Brokeback

frequently in the film, whereas Ballad, in keep- Mountain” 22). In this context, “cowboy” has

ing with dramatic Western conventions, avoids none of the irony of later uses of the term in

the word. Consider the difference in inflection either the film or our recent cultural history. It

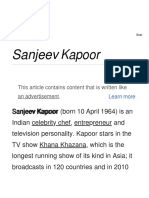

Photo 1: Jake Gyllenhaal

(left) and Heath Ledger as

Jack and Ennis in Broke-

back Mountain (2005).

48 journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

has, instead, all the affectionate nostalgia of term throughout the screenplay heightens

childhood innocence. this irony, reminding us that the story of Jack

In the screenplay of Brokeback, however, and Ennis is not the classic, heroic tale of the

Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana make much West. After Jack’s death in the film, Ennis visits

more use of the term “cowboy” than Proulx Jack’s parents and looks for consolation in his

does in her short story, as generic shorthand lover’s boyhood room, finding a little cowboy

(referring to cowboy hats and shirts) but also figurine—an emblem of boyhood dreams—

as a way to capture the constructed quality of before he finds their two shirts hidden away

the two characters. On one level, Ennis and Jack together. Repeatedly, we see that both men

are rare men of the late twentieth century who have struggled to live up to the mythic image of

make their livings riding horses and tending the western man and found themselves outside

livestock, but on another level, they are not the the boundaries of tradition and expectation.

archetypes of heterosexual masculinity they “Cowboy” is never used in Greenwald’s The

seem; they are masquerading. In an interview, Ballad of Little Jo, but much of the film, “based

actor Jake Gyllenhaal discussed the challenge on a true life” (Ballad), traces Josephine Mon-

of “cowboy school,” the training in riding and aghan’s self-construction as a “Westerner,”

roping he underwent to portray Jack Twist: to use Robert Warshow’s term. Heading west

after her Boston family disowns her for having

I’m not really a cowboy, and I think that’s a a child out of wedlock, Josephine is a female

really great thing for this part. I learned how Easterner who decides to protect herself by as-

to do the cowboy things, but my struggle with

suming a disguise in men’s clothes—a “simula-

trying to do it for real is the essence of Jack.

crum cowboy,” as Jim Kitses describes her (“An

He’s trying really hard. That’s who Jack is to

Exemplary” 369)—and begins her life as Little

me. (Brokeback DVD)

Jo. As played by Suzy Amis, Little Jo’s disguise

In the film, both Jack and Ennis fall short of may at first seem unbelievable to contempo-

being topnotch cowboys. We see it in Jack’s rary spectators, but writer-director Greenwald

dogged efforts to succeed in the rodeo and En- explains, “[W]e’re so used to women wearing

nis’s stunted progress in his career. jeans and suits and such that we don’t real-

Following that first summer on Brokeback ize the extent to which your outer appearance

Mountain, the term “cowboy” takes on a sexual dictated what you were accepted as being”

connotation, both straight and gay, in the film. (Modleski 561).

When Jack approaches a rodeo clown in a bar, When Little Jo enters the primitive settle-

ostensibly to buy him a drink for distracting ment of Ruby City, he/she is almost immedi-

the bull he was riding, the man deflects his ately challenged as a possible “dude,” which

approach with “Save your money for your next most critics interpret as “homosexual,” but

entry fee, cowboy” (McMurtry and Ossana which Greenwald has defined as “an upper

35).3 Lureen (Anne Hathaway), the rodeo bar- class person, dressed fancy, who didn’t have

rel rider Jack eventually marries, proves to be to work” (personal interview). In one of many

more aggressive than he in their first meeting: sly gags, then, Little Jo is challenged not as

“What are you waiting for, cowboy—a matin’ a man but as the right kind of man, much as

call?” (40). Several years later, after Ennis and Jack Twist is challenged, as I discuss later.

Alma have divorced, Ennis is almost snagged Many of the ensuing episodes or verses of

by Cassie, who loves to dance: “C’mon cow- this “ballad” turn on Little Jo’s having to pass

boy, you’re stayin’ on your feet” (78). As both another test or acquire another skill of the

Jack and Ennis age, references to their status Westerner. Like Jack and Ennis, Jo is hired

as “cowboys” become increasingly ironic for the lonely job of watching sheep—in Jo’s

in contrast to the truth of their situations. case, over an entire winter. More than Jack

McMurtry and Ossana’s repeated use of the and Ennis, Jo faces isolation, harsh weather,

journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010 49

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

and the threats of wild animals. But unlike helps a gambler cheat at poker, and later she

Jack and Ennis—both real men biologically—Jo lies about how she received the necklace,

in her disguise as a man proves to be an out- which becomes proof of both her infidelity to

standing Westerner, returning from the moun- Doc Holliday and the identity of James Earp’s

tain in the spring with the flock virtually intact killer. The greatest punishment these minor-

and sporting a mountain man’s coat of coyote ity characters experience, Simmon argues, is

pelts. This key difference—the issue of the exclusion. He notes the physical transforma-

protagonists’ success or failure as “cowboys” tion of Tombstone after the scene with Indian

and Westerners—resonates in the generic Charlie. The next day, the two-story saloon

makeup of the two films. Wyatt entered to stop the Indian no longer ex-

ists across the street from the barber shop, and

Transgression, Guilt, and Violence Wyatt can sit on the long wooden sidewalk,

in the Western gazing into open country. Says Simmon, “The

town is literally a different place after the Indian

The main project of the classic Western was to has been kicked out of it” (238–39). Chihuahua

dramatize the settling of the West, a story ani- pays for her more serious crimes by being shot

mated by the figure who embodied both civili- not by Wyatt, but by the Clanton boy who mur-

zation and savagery, engaged in a conflict set dered James. Despite Doc Holliday’s attempt to

on a territorial border between the two (Schatz save her, Chihuahua dies, ridding Tombstone of

48). Since the days of the classic Westerns, that another non-white member of the community,

terrain, both geographical and cultural, has without Wyatt having to resort to violence.

also suggested a border dividing not just ter- One way or another, elimination of marginal-

ritory but also people who have a “right,” who ized characters becomes morally justified and

“belong,” and those who do not. expected in the course of the typical Western

In his discussion of My Darling Clementine, plot. In The Six-Gun Mystique, John Cawelti

Scott Simmon focuses on the scene in which turns to a sociopsychological analysis from the

Wyatt Earp and his brothers first ride into 1950s by Peter Homans. In one passage of Ho-

Tombstone for a drink and a shave, leaving man’s work, a contemporary reader might find

youngest brother James at camp. Interrupted in the Western’s subtext of emotional repression,

his shave when a drunken Indian starts wildly homophobia, and misogyny brought into a dif-

shooting, Wyatt dispenses with Indian Charlie ferent light. Homans sees the plot of the West-

by hitting him on the head and dragging him ern as “a series of temptations to be resisted

out of the saloon. He hauls the Indian onto his by the hero” by an act of will, but “[w]hen faced

feet, kicks him in the rear end, and tells him to with the embodiment of these temptations,” the

“Get out of town and stay out!” For this display hero becomes justified in violent elimination of

of frontier justice, Wyatt is offered the job of the threat (qtd. in Cawelti 23). As Cawelti points

marshal on the spot. Simmon points out the out, Homans is arguing that the Western thus

film’s treatment of Native Americans extends

to Chihuahua, who is Mexican or Apache or a permit[s] a legitimated indulgence in vio-

combination of both, and is at first tossed into lence while reasserting at the same time

the ‘Puritan’ norm of the primacy of will over

a horse trough and later told to go back to the

feeling. Therefore, Mr. Homans believes there

reservation.

is a connection between the popularity of the

As Simmon’s description of Indian Charlie

Western and the cyclic outbursts of religious

and Chihuahua and, indeed, the conventional revivalism in the United States. (23)

treatment of minorities in studio-era Westerns

suggest, these characters’ marginal status is Based on this argument, the protagonists of

paired with some crime or transgression: Indian Brokeback Mountain and Ballad of Little Jo are

Charlie is drunk and disorderly; Chihuahua characters whose transgressive behavior, if

50 journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

we allow for any latent homosexual or Oedipal 131). But Jack and Ennis’s preoccupation with

subtexts, would be seen as the sources of one another results directly in the dead sheep,

temptation, and thus, they would be characters which Ennis discovers with “shame” (McMurtry

whom the conventional Western hero would be and Ossana 20), and the lower count when

compelled justifiably to dispatch violently. they bring the flock back to Aguirre. When Jack

The two young men we meet at the begin- returns the following year to ask for employ-

ning of Brokeback would not appear to be good ment, Aguirre turns him down not merely for

material for righteous elimination. In fact, the homosexual activity but for failing to do his job:

first suggestion of any behavior outside proper “you guys wasn’t gettin’ paid to leave the dogs

laws and boundaries comes from their new baby-sit the sheep while you stemmed the

boss, Joe Aguirre, who tells them to establish rose” (32). This failure to care for the sheep, to

a base camp on a designated Forest Service kill the coyote—in essence, their failure to be

campsite, but “pitch a pup tent on the Q.T. with successful cowboys—is paired with Jack and

the sheep. . . . [D]on’t leave no sign . . .”(3). Ennis’s homosexuality.

As a condition of their job, they have been Like the marginalized characters of classic

asked to violate a law, and Jack complains once Westerns, the two homosexual characters in

they have begun working on the mountain: Brokeback are shown to be guilty of something

“Aguirre’s got no right makin’ us do somethin’ other than their marginal status, but in an

against the rules” (7). In contrast to Aguirre’s interesting process of transference typical of

casual unlawfulness, as the two young men stereotyping (e.g., Indians are drunks), their

drink one night around the campfire, the song marginality—their homosexuality—becomes the

Jack sings is a Pentecostal hymn. Ennis asks primary reason for punishment. Jack in particular

what exactly Pentecost is, and Jack, himself is repeatedly cast as ineffectual and inept, by

puzzled, finally offers, “It’s when the world his boss, his wife, his father-in-law, and ulti-

ends and fellas like you and me march off to mately his own abusive father, all of whom seem

hell.” But Ennis replies, “Uh uh, speak for your- aware of or suspect Jack’s sexuality. This paired

self. You may be a sinner, but I ain’t yet had the prejudice is internalized, however, and violence

opportunity” (17). against homosexuals assumes its own justifica-

But the subsequent night of quick, urgent tion. When Jack proposes he and Ennis buy a

coupling between Jack and Ennis makes them ranch and live together, Ennis immediately re-

“sinners” by traditional (“Puritanical” to use jects the idea: “Bottom line, we’re around each

Homans’s term) values. There is no more talk other and this thing grabs hold of us again in the

about the boss’s breaking of rules. In that pas- wrong place, wrong time, we’re dead” (Broke-

sionate summer on Brokeback Mountain, they back). He tells the horrific story of being forced

end up jeopardizing the flock they were hired to by his father to view the results of a hate crime

care for: Jack fails to shoot the coyote that has committed against one of two men who had

killed at least one sheep (Ennis finally kills it lived together: “They’d took a tire iron to him,

later), and at another point while the two men spurred him up, drug him around by his dick till

are together, Aguirre’s flock gets mixed up with it pulled off. . . .” It is the terrifying memory of

another. Their behavior is witnessed by their this violence that prevents Ennis from openly

boss through his field glasses and confirmed entering into a relationship with Jack.

when he checks the flock upon their return. Because of their fear of being discovered,

As author Proulx points out, “livestock work- Jack and Ennis eventually are guilty of not just

ers have a blunt and full understanding of the one transgression but of others as well. Both

sexual behaviors of man and beast. High lone- marry within a few years after their summer on

some situation, a couple of guys—expediency Brokeback and become adulterers through their

sometimes rules and nobody needs to talk relationship and, in Jack’s case, other affairs,

about it and that’s how it is (“Getting Movied” both gay and straight. They lie to themselves

journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010 51

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

and to their wives; several years after Ennis and shopkeeper also passes judgment as Jose-

Alma’s divorce, she finally confronts him with phine turns to the stacks of men’s ready-made

his deception about the “fishing trips” the two pants and shirts. “It’s against the law to dress

men had taken for years. In what turns out to improper to your sex,” says the shopkeeper

be Ennis and Jack’s final time together, Ennis with narrowed eyes. Nevertheless, in a dressing

confronts Jack about his trips to Mexico, his room mirror, Josephine watches herself strip

rage barely suppressed: “What I don’t know, off layers of feminine adornment and confine-

all them things I don’t know . . . could get you ment. This scene is intercut with the scene of

killed if I should come to know them. I ain’t her seduction and the subsequent rejection by

jokin’” (Brokeback). This threat is consistent the family patriarch of her and her “bastard.” In

with the violence Ennis has exhibited at key the dressing room, we see her slash her cheek,

moments throughout the film, such as the beat- which will heal into a scar that becomes part

ing he gives two drunks at a family Fourth of of her gendered smokescreen—men will notice

July outing. Ennis’s violence has operated as a the scar, not the woman beneath it.

macho smokescreen for his homosexuality but In the next sequence we see a lone figure on

also manifests as a result of bottled-up rage a horse; the slight figure rides into Ruby City

and self-loathing. and speaks to a couple of the locals, who ad-

In the final scene with Jack, then, Ennis dress the newcomer as “kid.” This newcomer

threatens his lover with the brutality he himself is menaced by men in the saloon for possible

has feared. When Ennis learns of Jack’s death, “dude” status. Like Indian Charlie in Tomb-

Proulx’s story leaves the cause ambiguous— stone, the last “dude” was run out of Ruby

was it an accident, as Jack’s wife reported to City, in this case for wearing striped socks. Our

Ennis on the phone, or a tire-iron beating, as protagonist is forced at gunpoint to remove his/

Ennis feared? The film is clear, however: In a her boot to reveal a plain sock. Here, as Ennis

brilliant scene revealing the toll Jack’s choices did in Brokeback, Little Jo Monaghan protects

have taken on his wife, down to her chewed her secret with aggression. In this instance, it

nails and frozen mask of a face, Lureen me- is merely a verbal retort concerning “dudes”

chanically recites the accidental cause of her (“They’ve got as much right to be here as you

husband’s death, but during her rote narration, do, Mister”), but increasingly, her challenges

Ang cuts to the beating. A year after Annie will be backed up with a gun.

Proulx’s story was published—a story she says Indeed, much of the central part of Ballad,

is “of destructive rural homophobia” (“Getting which is closest to the conventional Western in

Movied” 130)—Matthew Shephard was beaten plot and character development, focuses on Lit-

to death just outside of Laramie, Wyoming, tle Jo’s education as a Westerner, including her

guilty only of homosexuality. growing proficiency with a gun and willingness

Transgression that leads to violence marks to use it. Tracing Jo’s progress as a sheepherder

several key scenes in Greenwald’s Ballad of in a classic montage of the greenhorn’s self-

Little Jo as well. First appearing as a solitary training, we see Little Jo become a good shot to

young woman walking west with a valise and protect the sheep, resulting in both the fur coat

parasol, Josephine Monaghan is victimized by a and a successful return with the flock. Jo does

traveling peddler who, calling her a vagrant and not use her gun against another person until

implying she is a prostitute, feels morally justi- her confrontation with Percy (Ian McKellen),

fied in selling her to two horsemen in uniform. the older, seemingly more “civilized” citizen of

He has her read from The Scarlet Letter just Ruby City who had acted as a mentor. This rela-

before the men appear to collect on their “justi- tionship had changed when a deaf-mute whore

fied” bargain. In terror, she escapes from them, came to town and Percy slashed the whore’s

but when she wanders, wet and bedraggled, cheek in a drunken rage. This violence (an echo

into a shop to buy fresh clothes, the female of the violence Josephine, also called “whore,”

52 journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

did to herself to escape worse) precipitated Jo’s she sees someone harassed and threatened—a

taking the sheep-tending job—self-imposed Chinese railroad worker, being passed among

isolation, similar to Ennis’s toward the end a jeering crowd of men, with a noose around

of Brokeback. When Jo returns to town in the his neck. The ringleader of this mock lynching

spring, Percy has read a letter that came for is Frank Badger, the same man who had been

Jo over the winter, and he knows all of Jo’s se- most concerned about Jo’s socks many years

crets: “You made a fool of me, Josephine.” He before. Here the Chinese man’s transgression

calls her a whore, and the attempted rape that may sound especially familiar today: he is a

follows, in a sharply edited onslaught of ugly foreigner accused of taking white men’s jobs.4

close-ups and overturned furniture, is halted Little Jo replies, “He’s tryin’ to eat,” but Badger

when Jo draws her gun. Percy agrees to leave persists in the harassment and humiliation of

town and keep her secret, for a price. He taunts “Tinman” Wong until Jo draws her gun.

her, saying, “They wonder about you. They’ll

never forgive you,” but swears he will keep his Transgression, Melodrama, and Comedy

word. Jo makes an oath of her own—“I’ll find

you and kill you”—but she lets the hammer And here’s where The Ballad of Little Jo returns

click on an empty gun. to a tone first struck in the “dude” scene early

Years later, when Little Jo rides into town, in the film. As in the earlier scene, there is a

now from her own ranch, she glimpses the threat of violence, but with the chief perpetrator

top-hatted president of the Western Cattle Com- played by Western character actor Bo Hopkins,

pany (a dude for sure) and then stops when there is also a comic undercurrent. The dia-

Photo 2: Suzy Amis as

Josephine “Jo” Monaghan

in The Ballad of Little Jo

(1993).

journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010 53

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

logue between Badger and Little Jo deals not comedy as two genres associated with women’s

just with the issue of a person of color being in stories, dealing with similar issues: complica-

Ruby City, but with gender-laden issues as well. tions in romance and family. Melodrama, Rowe

When Frank asks, “Don’t you ever have any says, presents a tragic, suffering, (usually)

fun?” Jo replies, “[We] don’t agree on what’s female hero, positioning the spectator as pow-

fun. . . .” Further into the scene, the dialogue erless to alter the unfolding tragedy, whereas

becomes even more personal as Badger tries to romantic comedy offers a resistant, rebellious

persuade Jo to hire the Chinese man as a cook. female hero: “Making fun of and out of inflated

and self-deluded notions of heroic masculinity,

jo: I don’t need a cook. romantic comedy is often structured by gender

frank: It’s nice havin’ a hot meal ready when inversion, a disruption of the social hierarchy of

you get home. male over female. . . .” Melodrama is the trag-

jo: My cookin’s fine. edy of the individual; romantic comedy leads to

frank: Too lonely out there. You need com- a new, utopian community (41).

pany. With Rowe, we turn to Robin Wood, who

jo: I don’t want company. considers it an error to “treat the genres as

frank: You’ll go crazy out there. I’ve seen it discrete,” arguing instead for an approach that

happen to men. And it worries me. would recognize genres as “different strategies

jo: Who asked you to worry about me? for dealing with the same ideological tensions”

frank: I can’t help it. (Ballad) (62). Ballad and Brokeback, looking like West-

erns and similarly focusing on taboo relation-

This exchange, despite the reciprocal threat ships, employ different secondary genres with

of violence, with Little Jo’s gun still drawn on profound ideological import. Jim Kitses cites

Frank Badger and Frank’s knife at Tinman’s Brokeback’s “sophisticated play with Western

throat, suggests at the very least Frank’s pro- conventions” (“All That” 23), but he quotes Ang

tective feelings toward the “boy.” Because we Lee as saying the film “has very little to do with

know the truth about Jo, however, the dialogue the Western genre” (24), and Kitses ultimately

edges into another generic territory altogether. concludes, “The expansive images from the

To director Maggie Greenwald, “An underlying film’s early scenes . . . shrink to the dimen-

theme in the movie is: Frank in love with Jo.” sions of crowded kitchens, closets, trailers, and

She sees Badger’s relationship with his wife as window-framed views” (26). Thus, Kitses sug-

“more like business partners . . . They had chil- gests (as does Osterweil) that the film “transi-

dren, but they didn’t make love because they tions into melodrama” (27). He compares Ennis

were in love. The real intimacy [for Frank] is with del Mar with the tragic Kyle Hadley of Douglas

his friends. Jo is his true love, based on a soul- Sirk’s Written on the Wind (1956).

ful friendship” (personal interview). Although Interestingly, The Ballad of Little Jo, despite

no romance will bloom openly between Frank its gender-bending female protagonist, follows

and Jo, they remain close until the film’s end. more closely the typical Western plot and char-

The humor in part comes from the gender rever- acterizations as well as the Western’s visual

sal that has the man expressing feelings of car- conventions. As Little Jo faces Frank Badger

ing and concern, while the character we know with her pistol drawn, she is taking up the

to be female remains tight-lipped and stoic. Westerner’s fight to bring civilization to Ruby

The joke is at Badger’s expense, given that the City—a more enlightened civilization than in

macho pose he has maintained throughout the Clementine because she is acting on a principle

film is undercut by feelings he “can’t help” hav- of inclusion rather than exclusion.5 But from

ing for what appears to be a young man. this point on in the film, Little Jo’s Western tra-

In her study of women’s genres, Kathleen jectory will be intertwined with romance and, at

Rowe has identified melodrama and romantic times, comedy of a special sort.

54 journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

Little Jo’s new domestic servant, of course, recovery from grave illness, leads Jo to the

quickly discovers the true sex of his employer, decision to stay and fight the Cattle Company.

first in a tense scene in the cabin after supper In the climax of the Western plot, Badger takes

when Jo, contentedly cleaning her gun, begins a shot at the company’s masked men and is

humming in a distinctly feminine register and wounded; Jo ends up shooting all three. After

Tinman notices. Again in a harshness similar the last shot, the camera circles from behind

to Ennis’s, Jo banishes Tinman from the cabin the classic Westerner to Jo’s face, in tears. The

into a driving rain. The next day, while the com- scene may be read as indicating Jo is “only a

petent Jo helps the physically weaker Tinman woman” after all, but Greenwald is showing

build a shelter, she nearly falls from the lad- instead the emotional toll of even righteous

der, and he catches her, his hand on her rear violence on the perpetrator—something the

end: “You’re no Mister Jo,” he says, and their male Westerner is never allowed to reveal. Just

relationship turns to deep friendship and love. as Frank Badger’s concern for Jo opens up the

Whereas Frank Badger provides the comedy emotional and romantic implications of men’s

and a hint of homosexual attraction, Tinman relationships in the West, this is the moment

provides real intimacy, sensuality, and a life- when the trope of the female Westerner opens

long partnership for Jo. Alone in the wilderness up the human (not male or female) implications

like Jack and Ennis, Jo and Tinman act on for- of the Western myth.

bidden desire, but unlike the Brokeback lovers, Ideologically speaking, both Brokeback and

they are able to create a utopian world in the Ballad address issues of gender, especially

old West. masculinity, as the Western has tradition-

Greenwald says of the Tinman character, ally displayed and exploited it. As a blend of

“Who in that landscape would be able to love Western and melodrama, Brokeback links its

Jo? . . . Someone who was her complement. exploration of gender with sexuality and the

Someone marginalized” (guest lecture). In failure of its characters to live up to gender-

Tania Modleski’s interview with Greenwald, the bound expectations and the tragedy resulting

director describes the Western’s stereotype from their transgressions as homosexuals. Bal-

of Asian men as asexual (363), which would lad was condemned by some lesbian critics for

have made the doubly transgressive romance not covering similar territory; critics including

between Jo and Tinman unnoticeable to others B. Ruby Rich and Karen Backstein argued Little

around them (Greenwald, personal interview). Jo’s cross-dressing should be linked with trans-

But eventually, they are forced to ponder the gressive sexuality as well (cited in Modleski;

danger created by their transgression. After a Kitses, “An Exemplary”). Director Greenwald

surprise visit from Badger, Jo worries, “How has said explicitly that she intended the film

long do you think it would take him to figure to be about gender, not sexuality (Modleski

out about me? . . . Little Jo Monaghan turns out 358), but the film is clearly about both gender

to be a woman, and she’s lovers with an ailing and sexuality as well as race (Kitses, “An Exem-

Chinaman?”—a beat—“They’d kill us.” Tinman plary” 371–73). Although Ballad is by no means

answers, “Unquestionably. Brutally” (Ballad). pure comedy—Jo’s sorrow over having to live

This new threat of violence parallels actual without her child is a melodramatic theme—its

violence perpetrated against the immigrant challenges of gender roles in the film’s grow-

family Jo had befriended years earlier. Their ing context of heterosexual romance gives this

murder by masked men of the Cattle Company Western ultimately a comic inflection. As Rowe

demands retribution but temporarily robs Jo of has suggested, the spectators of melodrama

her courage. Overwhelmed by the power of the are positioned to passively accept the Law

Cattle Company, she prepares to sell her ranch of the Father and its tragic implications; the

to the owner, but a glimpse of his stuffy wife spectators of comedy, however, are positioned

and repressed child, coinciding with Tinman’s as antiauthoritarian “subjects of a laughter

journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010 55

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

that expresses resistance, solidarity and joy” comes closer to Brokeback in its incorporation of

melodrama than Warhol’s parody of the Western that

(41). Surely Jo and Tinman’s relationship, in all

“mocked the taboo against homosexuality” (39–40).

its sensual complicity (opium-smoking in bed 3. For convenience, lines of dialogue from Broke-

beneath the coyote-fur covers), demonstrates back Mountain are cited by page numbers in the pub-

joyful subversion of traditional Western expec- lished screenplay, unless the dialogue is different in

tations. the film.

4. This is another scene with historic basis. The Chi-

Epilogues of the two films confirm their ge-

nese Exclusion Act of 1882 made Chinese immigration

neric tendencies. The end of Brokeback finds to the United States illegal in order to prevent further

Ennis some years after Jack’s death, living the competition with whites in the workforce. See http://

existence of a hermit to avoid his lover’s fate. www.asian-nation.org/racism.shtml.

The visit from his grown daughter to announce 5. In “Introduction: Post-Modernism and the West-

ern,” in The Western Reader, Kitses celebrates The

her upcoming marriage underscores all that

Ballad of Little Jo as one of two postmodern Westerns

he has been denied, all that he has suffered. (Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man being the other), citing

When his daughter leaves, he is alone again inclusion as one of the hallmarks of these new films

with the two shirts and the postcard of the based on the old genre. See also his wonderful analy-

mountain. In keeping with melodrama, his sis of Ballad, “An Exemplary Post-Modern Western:

The Ballad of Little Jo,” in The Western Reader as well.

transgression, guilt, and suffering have brought 6. I am indebted to my colleague, William Tate, for

Ennis to this lonely, tragic end. his comments on this scene.

The Ballad of Little Jo also moves years for-

ward to a time after Tinman has passed away, references

and an elderly Little Jo is discovered sick in Bingham, Dennis. Acting Male: Masculinities in the

bed by Badger, who (lovingly) tucks Jo into a Films of James Stewart, Jack Nicholson, and Clint

wagon to go to the doctor. But Jo is dead by Eastwood. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1994. Print.

Cawelti, John G. The Six-Gun Mystique. Bowling

the time Badger reaches town, and he orders

Green: Bowling Green UP, 1984. Print.

“the best funeral ever” for his friend. When the Greenwald, Maggie. Guest lecture. Portland State

undertaker announces Little Jo was a woman, University, Portland, OR. Apr. 2006.

and townspeople go to see for themselves, ———. Personal interview. 4 Aug. 2007.

their faces are seen almost from the body’s Kitses, Jim. “All That Brokeback Allows.” Film Quar-

terly 60.3 (2007): 22–27. Print.

( Jo’s) point of view. Each face registers surprise

———. “An Exemplary Post-Modern Western: The Bal-

and amazement, except that of the one woman lad of Little Jo.” The Western Reader. Ed. Jim Kitses

present, who breaks into laughter over the and Gregg Rickman. New York: Limelight, 1998.

joke that only she—and Jo, whose dead face is 367–80. Print.

shown as the woman’s laughter continues— ———. “Introduction: Post-Modernism and the West-

ern.” Kitses, The Western Reader. 15–31. Print.

can fully appreciate.6 While the men of the

McMurtry, Larry, and Diana Ossana. “Brokeback

town go through the comic business of posing Mountain, the Screenplay.” Brokeback Mountain,

the body on a horse for a photo, we see Frank Story to Screenplay. New York: Scribner, 2005.

Badger ransack Jo’s home, in rage or grief or 29–97. Print.

both, discovering the old photo of Josephine as Modleski, Tania. “Our Heroes Have Sometimes Been

Cowgirls: An Interview with Maggie Greenwald.”

a Boston debutant. Here we see the liberating, Film Quarterly 49.2 (1995–96): 2–11. Rpt. in The

comic potential of transgression in the Western. Western Reader. Ed. Kitses and Rickman. 355–66.

Both photos of Little Jo, printed side by side in Print.

the local newspaper, are the film’s last laugh. Osterweil, Ara. “Ang Lee’s Lonesome Cowboys.” Film

Quarterly 60.3 (2007): 38–42. Print.

notes Proulx, Annie. “‘Brokeback Mountain,’ the Story.”

Brokeback Mountain, Story to Screenplay. 1–28.

1. This article is a revised, expanded version of Print.

a paper presented at the 2007 UFVA Conference in ———. “Getting Movied.” Brokeback Mountain, Story

Denton, Texas. to Screenplay. 129–38. Print.

2. Osterweil suggests that the Schlesinger film Rowe, Kathleen. “Comedy, Melodrama and Gender:

56 journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

Theorizing the Genres of Laughter.” Classical Hol- Hathaway, Michelle Williams, and Randy Quaid.

lywood Comedy. Ed. Kristine Brunovska Karnick and Focus, 2005. DVD.

Henry Jenkins. New York: Routledge, 1995. 39–62. Destry Rides Again. Dir. George Marshall. Perf. Mar-

Print. lene Dietrich and James Stewart. Universal. 1939.

Schatz, Thomas. Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Film- The Electric Horseman. Dir. Sydney Pollack. Columbia,

making, and the Studio System. New York: Random 1979. VHS.

House, 1981. Print. Lonesome Cowboys. Dir. Andy Warhol. Andy Warhol/

Simmon, Scott. The Invention of the Western Film: A Sherpix, 1967.

Cultural History of the Genre’s First Half-Century. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Dir. John Ford.

New York: Cambridge UP, 2003. 234–42. Print. Ford Prod./Paramount, 1962. VHS.

Warshow, Robert. “Movie Chronicle: The Westerner.” Midnight Cowboy. Dir. John Schlesinger. Jerome Hell-

Partisan Review (Mar.-Apr. 1954). Rpt. in The West- man/United Artists, 1969.

ern Reader. Ed. Kitses and Rickman. 35–47. Print. My Darling Clementine. Dir. John Ford. Perf. Henry

Wood, Robin. “Ideology, Genre, Auteur.” Film Com- Fonda, Victor Mature, Walter Brennan, Linda

ment 13.1 (1977): 46–51. Rpt. in Film Genre Reader Darnell, Tim Holt, Ward Bond, John Ireland, Cathy

II. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: U of Texas P, 1995. Downs, and Charles Stevens. Twentieth Century

59–73. Print. Fox, 1946.

3:10 to Yuma. Dir. James Mangold. Perf. Russell Crowe

filmogr aphy and Christian Bale. Lionsgate, 2007.

Unforgiven. Dir. Clint Eastwood. Perf. Clint Eastwood

Appaloosa. Dir. Ed Harris. Perf. Ed Harris, Viggo and Gene Hackman. Malpaso/Warner Brothers,

Mortenson, and Jeremy Irons. New Line, 2008. 1992. DVD.

The Ballad of Little Jo. Dir. Maggie Greenwald. Perf. Urban Cowboy. Dir. James Bridges. Perf. John Travolta.

Suzy Amis, Bo Hopkins, Ian McKellen, David Chung, Paramount, 1980. VHS.

Rene Aubejonois, and Carrie Snodgrass. Fine Line, Written on the Wind. Dir. Douglas Sirk. Universal,

1993. VHS. 1956. DVD.

Brokeback Mountain. Dir. Ang Lee. Perf. Heath Ledger,

Jake Gyllenhaal, Linda Cardellini, Anna Faris, Anne

journal of film and video 62. 4 / winter 2010 57

©2010 by the board of trustee s of the universit y of illinois

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Altman-Fact Vs Fiction How Paratextual Information ShapesDokument8 SeitenAltman-Fact Vs Fiction How Paratextual Information ShapesA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Russ-Disordering History, Denying PoliticDokument10 SeitenRuss-Disordering History, Denying PoliticA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cover SheetDokument23 SeitenCover SheetA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Studies in 20th & 21st Century LiteratureDokument3 SeitenStudies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Studies in 20th & 21st Century LiteratureA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pryor-Ethnography of An American Main StreetDokument18 SeitenPryor-Ethnography of An American Main StreetA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shyminsky-Mutant Readers Reading Mutants AppropriaDokument19 SeitenShyminsky-Mutant Readers Reading Mutants AppropriaA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Screen 1972 Benjamin 5 26Dokument22 SeitenScreen 1972 Benjamin 5 26Kevin BrazilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maruo-Caricature and Face Recognition PDFDokument8 SeitenMaruo-Caricature and Face Recognition PDFA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zingsheim-X-Men Evolution Mutational Identity and Shifting SubjectivitiesDokument18 SeitenZingsheim-X-Men Evolution Mutational Identity and Shifting SubjectivitiesA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pryor-Ethnography of An American Main StreetDokument18 SeitenPryor-Ethnography of An American Main StreetA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perineum - Erika LopezDokument19 SeitenPerineum - Erika LopezA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MC Mullin 2014Dokument19 SeitenMC Mullin 2014A Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stimpson 2014Dokument2 SeitenStimpson 2014A Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018domoney LyttlePhDDokument217 Seiten2018domoney LyttlePhDA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panovksy-On The Problem of Describing and InterpretingDokument17 SeitenPanovksy-On The Problem of Describing and InterpretingA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Composing NoiseDokument57 SeitenComposing NoiseRiccardo Mantelli100% (9)

- Borders, Batos Locos and Barrios: Space As Signifier in Chicano CinemaDokument24 SeitenBorders, Batos Locos and Barrios: Space As Signifier in Chicano CinemaA Guzmán Maza100% (1)

- Basker-Amazin Grace (Poems About Slavery) PDFDokument52 SeitenBasker-Amazin Grace (Poems About Slavery) PDFA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge TamaiDokument13 SeitenGe TamaiIrina DrăguțNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nelson-Sick Humor Which Serves No PurposeDokument18 SeitenNelson-Sick Humor Which Serves No PurposeA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Jesus-Liminality and Mestiza Consciousness in Lynda Barry's One Hundred DemonsDokument34 SeitenDe Jesus-Liminality and Mestiza Consciousness in Lynda Barry's One Hundred DemonsA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andrade Cannibalistic ManifestoDokument14 SeitenAndrade Cannibalistic ManifestoVeronica DellacroceNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Fears, City of Hopes: by Zygmunt BaumanDokument39 SeitenCity of Fears, City of Hopes: by Zygmunt BaumanAnna LennelNoch keine Bewertungen

- James Boyd White The Edge of Meaning 1Dokument332 SeitenJames Boyd White The Edge of Meaning 1A Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beaulieu Automythology.Dokument33 SeitenBeaulieu Automythology.A Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuan, Yi-Fu-ThoughtLandscape PDFDokument13 SeitenTuan, Yi-Fu-ThoughtLandscape PDFA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cronin-Patterns of Puffery An Analysis of Non-Fiction BlurbsDokument8 SeitenCronin-Patterns of Puffery An Analysis of Non-Fiction BlurbsA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davis-A Graphic Self PDFDokument17 SeitenDavis-A Graphic Self PDFA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bradley - Graphic Memoirs Come of AgeDokument6 SeitenBradley - Graphic Memoirs Come of AgeA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Planarch Codex: The Path of Ghosts: An Ancestral Cult Recently Popular Among Thieves & AssassinsDokument2 SeitenPlanarch Codex: The Path of Ghosts: An Ancestral Cult Recently Popular Among Thieves & AssassinshexordreadNoch keine Bewertungen

- O Brother, Where Art ThouDokument38 SeitenO Brother, Where Art Thouharrybiscuit100% (4)

- Reading 10-1Dokument7 SeitenReading 10-1luma2282Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lab Dot Gain Calculator 1Dokument2 SeitenLab Dot Gain Calculator 1Djordje DjoricNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gothic Style - Architecture and Interiors From PDFDokument272 SeitenGothic Style - Architecture and Interiors From PDFsabina popovici100% (1)

- Silvercrest DVD PlayerDokument29 SeitenSilvercrest DVD PlayerterrymaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brazing PrinciplesDokument118 SeitenBrazing PrinciplesKingsman 86100% (1)

- Oceans Will PartDokument2 SeitenOceans Will PartAnthony JimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wasteland Fury - Post-Apocalyptic Martial Arts - Printer FriendlyDokument29 SeitenWasteland Fury - Post-Apocalyptic Martial Arts - Printer FriendlyJoan FortunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The True Story of PocahontasDokument22 SeitenThe True Story of PocahontasKatherinFontechaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bodhisattva Doctrine in Buddhist Sanskrit Literature - Har DayalDokument412 SeitenBodhisattva Doctrine in Buddhist Sanskrit Literature - Har Dayal101176Noch keine Bewertungen

- TG - Music 7 - Q1&2Dokument45 SeitenTG - Music 7 - Q1&2Antazo JemuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanjeev KapoorDokument12 SeitenSanjeev KapoorPushpendra chandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lightroom Magazine Issue 29 2017Dokument61 SeitenLightroom Magazine Issue 29 2017ianjpr0% (1)

- Message in A Bottle Lesson PlanDokument8 SeitenMessage in A Bottle Lesson PlanKatalin VeresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hero Realms Ruin of Thandar RulesDokument40 SeitenHero Realms Ruin of Thandar Rulespavlitos kokaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Script Story of PaulDokument2 SeitenScript Story of PaulMonica M Mercado100% (2)

- The Lessons Taught by Political SystemsDokument5 SeitenThe Lessons Taught by Political SystemsPaula HintonNoch keine Bewertungen

- MillwardBrown KnowledgePoint EmotionalResponseDokument6 SeitenMillwardBrown KnowledgePoint EmotionalResponsemarch24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mintmade Fashion: Fresh Designs From Bygone ErasDokument15 SeitenMintmade Fashion: Fresh Designs From Bygone ErasShivani ShivaprasadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parappa The Rapper 2Dokument65 SeitenParappa The Rapper 2ChristopherPeter325Noch keine Bewertungen

- 426 C1 MCQ'sDokument5 Seiten426 C1 MCQ'sKholoud KholoudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Origami: by Joseph ChangDokument12 SeitenOrigami: by Joseph ChangmoahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- The New Machine - Little Big Story BooksDokument37 SeitenThe New Machine - Little Big Story BooksbkajjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOPAZ GLOSS EMULSIONDokument2 SeitenTOPAZ GLOSS EMULSIONsyammcNoch keine Bewertungen

- THE TRAGEDY OF THE EXCEPTIONAL INDIVIDUAL IN THE WORKS OF HENRIK IBSEN AND VAZHA-PSHAVELA - Kakhaber LoriaDokument7 SeitenTHE TRAGEDY OF THE EXCEPTIONAL INDIVIDUAL IN THE WORKS OF HENRIK IBSEN AND VAZHA-PSHAVELA - Kakhaber LoriaAnano GzirishviliNoch keine Bewertungen

- G4-VM Workshop Final Report PDFDokument95 SeitenG4-VM Workshop Final Report PDFMaliki Mustafa100% (1)

- Tragedy Fact SheetDokument1 SeiteTragedy Fact SheetSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who's Been A Good Boy-GirlDokument13 SeitenWho's Been A Good Boy-GirlNevena Živić MinčićNoch keine Bewertungen