Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Sepsis in General Surgery: The 2005-2007 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Perspective

Hochgeladen von

edo andriyantoOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Sepsis in General Surgery: The 2005-2007 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Perspective

Hochgeladen von

edo andriyantoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PAPER

Sepsis in General Surgery

The 2005-2007 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Perspective

Laura J. Moore, MD; Frederick A. Moore, MD; S. Rob Todd, MD; Stephen L. Jones, MD;

Krista L. Turner, MD; Barbara L. Bass, MD

Objective: To document the incidence, mortality rate, for myocardial infarction. The septic-shock group had a

and risk factors for sepsis and septic shock compared with greater percentage of patients older than 60 years (no sep-

pulmonary embolism and myocardial infarction in the sis, 40.2%; sepsis, 51.7%; and septic shock, 70.3%;

general-surgery population. P⬍ .001). The need for emergency surgery resulted in

more cases of sepsis (4.5%) and septic shock (4.9%) than

Design: Retrospective review. did elective surgery (sepsis, 2.0%; septic shock, 1.2%)

(P⬍ .001). The presence of any comorbidity increased

Setting: American College of Surgeons National Surgi- the risk of sepsis and septic shock 6-fold (odds ratio, 5.8;

cal Quality Improvement Program institutions. 95% confidence interval, 5.5-6.2) and increased the 30-

day mortality rate 22-fold (odds ratio, 21.8; 95% confi-

Patients: General-surgery patients in the 2005-2007 Na- dence interval, 17.6-26.9).

tional Surgical Quality Improvement Program data set.

Conclusions: The incidences of sepsis and septic shock

Main Outcome Measures: Incidence, mortality rate, exceed those of pulmonary embolism and myocardial in-

and risk factors for sepsis and septic shock. farction. The risk factors for mortality include age older

than 60 years, the need for emergency surgery, and the

Results: Of 363 897 general-surgery patients, sepsis oc- presence of any comorbidity. This study emphasizes the

curred in 8350 (2.3%), septic shock in 5977 (1.6%), pul- need for early recognition of patients at risk via aggres-

monary embolism in 1078 (0.3%), and myocardial in- sive screening and the rapid implementation of evidence-

farction in 615 (0.2%). Thirty-day mortality rates for each based guidelines.

of the groups were as follows: 5.4% for sepsis, 33.7% for

septic shock, 9.1% for pulmonary embolism, and 32.0% Arch Surg. 2010;145(7):695-700

P

REVENTION OF PERIOPERA - surgery patients have become standards

tive complications is a ma- of care. The issue of SSIs has been ad-

jor focus in the care of the dressed through national guidelines.2 Mini-

general-surgery patient. In mizing the occurrence of these poten-

recent years, much atten- tially preventable complications improves

tion has focused on the prevention of ve- patient outcomes and reduces health care

nous thromboembolism (postoperative costs.

deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary em- Within our institution, we have iden-

bolism [PE]), postoperative myocardial in- tified surgical sepsis to be a potentially pre-

farction (MI), and surgical site infections ventable cause of morbidity and mortal-

ity in our general-surgery patients. Severe

sepsis and septic shock are the leading

CME available online at causes of multiple organ failure and mor-

www.jamaarchivescme.com tality in noncoronary intensive care units

and questions on page 615 (ICUs).3 It is estimated that in the United

States there are 751 000 cases per year of

(SSIs). Through education and increased sepsis, with an annual cost of $17 bil-

Author Affiliations: awareness, there has been a significant re- lion.4 By 2010, it is estimated that there

Department of Surgery, The duction in the incidence of postoperative will be 934 000 cases per year.3 Unfortu-

Methodist Hospital, Weill venous thromboembolism. 1 Likewise, nately, despite tremendous basic and clini-

Cornell Medical College, preoperative cardiovascular evaluation cal research efforts, mortality from septic

Houston, Texas. and risk assessment of elective general- shock remains unchanged at greater than

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 7), JULY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM

695

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 08/12/2018

lection. All variables that are gathered in the NSQIP are pre-

Table 1. NSQIP Definitions of Sepsis and Septic Shock defined in the NSQIP data dictionary.

The 2005-2007 NSQIP Participant Use File was queried for

Sepsis (SIRS and infection) demographics, comorbidities, elective vs emergency case, and

SIRS criteria (ⱖ2 must be present) 30-day mortality in general-surgery patients. Patients having

Temperature ⬎38°C or ⬍36°C severe sepsis and septic shock are classified in the NSQIP data

Heart rate ⬎90/min set as the septic-shock stratum, whereas patients having only

Respiratory rate ⬎20/min or PaCO2 ⬍32 mm Hg sepsis are classified as the sepsis stratum. Patients without either

White blood cell count ⬎12 000/µL (12.0 ⫻ 109/L) or ⬍4000/µL sepsis or septic shock are classified as the no-sepsis stratum.

(4.0 ⫻ 109/L) or ⬎10% bands

This strategy was adopted by NSQIP to avoid counting pa-

Infection

Positive blood culture or

tients who had severe sepsis and septic shock twice. The NSQIP

Purulence or positive culture from any site thought to be causative data dictionary defines sepsis as the systemic inflammatory re-

Septic shock (sepsis and organ or circulatory dysfunction) sponse syndrome with a documented infection and defines sep-

Organ dysfunction(s) tic shock as sepsis and documented organ and/or circulatory

Oliguria dysfunction. The NSQIP definition of septic shock captures those

Acute alteration of mental status patients who are defined as having severe sepsis by the Ameri-

Acute respiratory distress can College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medi-

Circulatory dysfunction(s) cine Consensus Conference Guidelines.9 Detailed descrip-

Hypotension tions of the NSQIP definitions are presented in Table 1. From

Requirement of inotropic or vasopressor agents the NSQIP data set, we were unable to determine the source of

the sepsis.

Abbreviations: NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; A PE is defined by the NSQIP as “lodging of a blood clot in

SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

a pulmonary artery with subsequent obstruction of blood sup-

ply to the lung parenchyma.”10p31 The NSQIP data dictionary

defines a postoperative MI as “a new transmural acute myo-

50%.5 Early intervention and implementation of evidence-

cardial infarction occurring during surgery or within 30 days

based guidelines have been demonstrated to improve out- as manifested by new Q-waves on ECG [electrocardiogram].”10p28

comes in patients with sepsis.6,7 However, effective in- It also states, “The blood clots usually originate from the deep

tervention is contingent on the early identification of leg veins or the pelvic venous system within 30 days of the op-

sepsis. eration. PE documented if the patient has a ventilation-

In an attempt to improve the early identification of perfusion scan interpreted as high probability of PE or a posi-

sepsis, we have developed and instituted a sepsis tive computed tomography spiral exam, pulmonary arteriogram,

screening tool for use in our surgical ICU (SICU).8 The or computed tomography angiogram. Treatment usually con-

use of this tool and implementation of early evidence- sists of initiation of anticoagulation therapy or placement of

based care through computerized clinical decision sup- mechanical interruption (eg, Greenfield filter), for patients whom

port resulted in a substantial decrease in the rate of anticoagulation is contraindicated or already instituted.”10p31

mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock.8 On the Patient body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in

basis of this experience, we believe that sepsis screening kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Patient rec-

ords that were missing the weight or height were classified as

could potentially prevent sepsis-associated morbidity

unknown BMI. The patients were then stratified by their BMI

and mortality in the general-surgery population. Before following the 5 major categories of underweight, normal, over-

advocating mandatory sepsis screening programs in weight, obese, and severely obese (obese class III) as defined

general-surgery patients, we need to further character- by the World Health Organization BMI classification guide-

ize and understand sepsis in these patients. Further- lines.11 The classification breakdown for BMI is as follows: less

more, we need to document the relative incidence and than 18.50 is classified as underweight, between 18.50 and 24.99

associated mortality of sepsis compared with the more as normal, between 25.00 and 29.99 as overweight, between

commonly addressed preventable causes of postopera- 30.00 and 39.99 as obese, and 40.00 or higher as severely obese.

tive mortality. The objective of this study was to docu- Patients were further categorized by ethnicity and age. Pa-

ment the incidence, mortality, and risk factors for sep- tients were classified based on their NSQIP-defined ethnicity.

sis and septic shock compared with PE and MI in the After initial data explorations, it was clear that patients older

general-surgery population. than 60 years formed a significant stratum of their own; thus,

we stratified patients according to their age by whether or not

they were older than 60 years at the time of the operation. Simi-

METHODS larly, patients were categorized by whether the procedure was

an emergency or elective. From the NSQIP data set, we were

This study is an analysis of prospectively collected data from unable to determine whether the sepsis occurred before or af-

the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Im- ter the emergency surgical procedures.

provement Program (NSQIP) data set. The 2005-2007 NSQIP In comparing the study groups, a 2 analysis was used for

data set contains prospectively gathered clinical data and out- categorical data. Generalized linear models were used to cal-

comes on 363 897 patients collected from 121 academic and culate the adjusted relative risk between the presence of any

community-based hospitals. The NSQIP compiles data on of the NSQIP-documented comorbidities and risk of develop-

239 variables, including preoperative, intraoperative, and ing sepsis, septic shock, or 30-day mortality after adjustment

30-day postoperative variables, for patients undergoing surgi- for age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, and emergency case.12 P ⬍ .05 was

cal procedures in inpatient and outpatient settings (a sample considered statistically significant. Stata statistical software, ver-

of general-surgery cases using an 8-day cycle). All data are col- sion 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas), was used for

lected by an institutional surgical clinical nurse reviewer, who all statistical analyses. The review of data was approved by The

receives extensive training in the NSQIP methods and data col- Methodist Hospital Research Institute.

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 7), JULY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM

696

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 08/12/2018

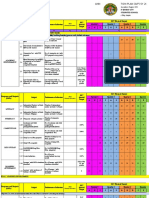

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of the Population a 9000 8350

(2.3%) Incidence

8000 Mortality

No. (%)

7000

5977

Septic (1.6%)

No Sepsis Sepsis Shock 6000

No. of Patients

Characteristics (n=349 570) (n=8350) (n=5977)

5000

Male sex 147 120 (42.1) 4248 (50.9) 3179 (53.2)

4000

Age, y

ⱕ19 5265 (1.5) 60 (0.7) 10 (0.2) 3000

2012

20-59 203 788 (58.3) 3975 (47.6) 1767 (29.6) (33.7%)

ⱖ60 140 517 (40.2) 4315 (51.7) 4200 (70.3) 2000 1078

(0.3%) 615

Ethnicity 1000 449

(5.4%) 98 (0.2%) 193

White 247 361 (70.8) 5982 (71.6) 4356 (72.9) (9.1%) (32.07%)

Asian or Pacific Islander 6472 (1.9) 140 (1.7) 101 (1.7) 0

Sepsis Septic Shock Pulmonary Myocardial

African American 33 548 (9.6) 1128 (13.5) 740 (12.4) Embolism Infarction

Hispanic 26 543 (7.6) 466 (5.6) 339 (5.7)

Group

American Indian 3230 (0.9) 47 (0.6) 34 (0.6)

Unknown 32 416 (9.3) 587 (7.0) 407 (6.8)

BMI b Figure. Incidence and mortality by group.

Underweight (⬍18.50) 8272 (2.4) 421 (5.0) 355 (5.9)

Normal (18.50-24.99) 95 022 (27.2) 2419 (29.0) 1744 (29.2)

Overweight (25.00-29.99) 102 841 (29.4) 2251 (27.0) 1565 (26.2) Table 3. Top 5 Operative Procedures for Sepsis

Obese (30.00-39.99) 90 532 (25.9) 2034 (24.4) 1357 (22.7) and Septic Shock

Severely obese (ⱖ40.00) 37 605 (10.8) 790 (9.5) 533 (8.9)

Unknown 15 298 (4.4) 435 (5.2) 423 (7.1)

Smoking 72 979 (20.9) 2179 (26.1) 1560 (26.1) Sepsis Septic Shock

Drinking 8875 (2.5) 335 (4.0) 301 (5.0) Partial removal of colon Partial removal of colon

Removal of small intestine Removal of small intestine

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms Arterial bypass graft Arterial bypass graft

divided by the height in meters squared). Partial removal of pancreas Removal of colon

a Data are presented as number (percentage). Percentages may not total 100

Removal of colon Exploration of abdomen

because of rounding. P ⬍.001 for all characteristics.

b Data unavailable for 37 605 patients.

groups (no sepsis, 0.6%; sepsis, 4.0%; and septic

RESULTS shock,30.0%; P ⬍ .001) and the emergency-case groups

(no sepsis,4.9%; sepsis,9.4%; and septic shock,39.3%;

The 2005-2007 NSQIP data set contains information on P ⬍ .001) were different, but patients with septic shock

363 897 general-surgery patients. Of these, 349 570 in elective and emergency cases had a similar high mor-

(96.1%) had no sepsis, 8350 (2.3%) had sepsis, and 5977 tality rate. The development of sepsis increased the risk

(1.6%) had septic shock. Pulmonary embolism oc- of 30-day mortality 4-fold (OR,3.9; 95% CI, 3.5-4.3). The

curred in 1078 patients (0.3%) and MI in 615 (0.2%). development of septic shock increased the risk of 30-

The demographic breakdown for the entire population day mortality 33-fold (OR,32.9; 95% CI, 30.9-35.1). The

is listed in Table 2. The septic-shock group had a greater operative procedures most commonly associated with

percentage of patients older than 60 years (no sep- sepsis and septic shock are listed in Table 3.

sis, 40.2%; sepsis, 51.7%; and septic shock, 70.3%;

P⬍.001). The incidence of sepsis and septic shock in elec- COMMENT

tive cases was 2.0% and 1.2%, respectively, compared with

4.5% and 4.9%, respectively, for sepsis and septic shock Minimizing mortality by preventing postoperative com-

in emergency cases (P ⬍ .001). The sepsis and septic- plications is a key component of surgical care. In recent

shock groups had a higher incidence of patients with 1 years there has been an increasing focus on minimizing

or more NSQIP comorbidities (no sepsis, 69.0%; sep- the risk of perioperative complications, including ve-

sis,90.2%; and septic shock, 96.4%; P ⬍.001). The pres- nous thromboembolism, perioperative cardiac events, and

ence of any of the NSQIP-documented comorbidities in- SSIs. Multiple professional organizations have pub-

creased the odds of developing sepsis and septic shock lished guidelines addressing these issues.2,13,14 There is

by 6-fold (odds ratio [OR], 5.8; 95% confidence interval no question that the implementation of these guidelines

[CI], 5.5-6.2). In addition, the presence of any comor- has reduced the occurrence of these perioperative ad-

bidity when compared with patients without comorbidi- verse events and subsequent mortality. However, the find-

ties increased the risk of 30-day mortality 22-fold ings of this study demonstrate that sepsis continues to

(OR,21.8; 95% CI, 17.6-26.9). Thirty-day mortality rates be a common and serious complication in general-

for each of the groups were as follows: no sepsis, 1.1%; surgery patients and occurs much more frequently than

sepsis, 5.4%; and septic shock, 33.7% (vs 9.1% for PE and PE and MI. Of note, septic shock occurs 10 times more

32.0% for MI). The incidence and mortality rates for the frequently than MI and has the same mortality rate; thus,

groups are depicted in the Figure. The 30-day mortal- it kills 10 times more people. These findings are consis-

ity of sepsis and septic shock within the elective case tent with other studies15-17 demonstrating that sepsis con-

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 7), JULY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM

697

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 08/12/2018

tinues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in tients with septic shock from ventilator-associated pneu-

surgical patients. monia identified advanced age, lymphocytopenia, high

Surgical site infections are defined as infections oc- blood glucose levels, and increased clinical pulmonary

curring up to 30 days after surgery and affecting either infection scores as independent predictors of the devel-

the incision or deep tissue at the operative site.18 Surgi- opment of septic shock. The findings of advanced age and

cal site infections are the second most common nosoco- preexisting liver or cardiac insufficiency from these stud-

mial infection in hospitalized patients, occurring in at least ies are consistent with our findings.

2% of those undergoing surgical procedures.19 The Cen- Our analysis of the NSQIP data set identified 3 major

ters for Disease Control and Prevention have estab- risk factors for the development of sepsis and septic

lished guidelines to address the issue of SSI.2 These guide- shock and mortality from sepsis and septic shock: age

lines focus on a bundle approach, ie, optimization of older than 60 years, the need for emergency surgery,

patient factors, antisepsis in the operating room, admin- and the presence of any comorbidity. The association

istration of prophylactic antibiotics, and postoperative between age, the presence of comorbid conditions, and

incision care.2 Although these initiatives can decrease the the need for emergency surgery and development of

occurrence of SSI, they fail to address the systemic role sepsis or septic shock has been demonstrated in larger

of sepsis, of which SSIs are only a low-risk subset of po- epidemiologic studies.4,5,24 However, these studies were

tential causes. In particular, these guidelines fall short retrospective analyses of International Classification of

of addressing the issue of postoperative surveillance for Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9)25 discharge data from

the development of sepsis. state databases. These findings suggest that those pa-

Within our institution, we have identified sepsis to be tients with any of these 3 factors warrant a high index of

a major cause of morbidity and mortality in our general- suspicion for the development of sepsis and that this

surgery patients. As a result, our multidisciplinary sep- patient population would most likely benefit from man-

sis research team has developed a sepsis-management pro- datory sepsis screening.

tocol that uses computerized clinical decision support to A healthy respect for these risk factors, in addition to

ensure timely and consistent implementation of the evi- early sepsis identification by screening, has influenced

dence-based guidelines for the management of sepsis.20 our surgical management of this patient population. A

Through our initial experience with implementation of distinct window of early intervention exists in which the

our computerized clinical decision support sepsis- septic source must be eliminated and physiologic de-

management protocol, we encountered the unantici- rangements corrected. For the postoperative patient whose

pated problem of untimely and inaccurate recognition sepsis has a nonsurgical source, such as pneumonia or a

of sepsis by bedside physicians. The need for routine, ac- urinary tract infection, this goal can be accomplished in

curate screening of all SICU patients for sepsis quickly an ICU setting in a straightforward manner. In the set-

became apparent. In an attempt to increase the early iden- ting of abdominal surgical sepsis, however, this issue be-

tification of sepsis, we developed a sepsis screening tool comes more complicated. This patient often requires emer-

in our SICU.8 This tool is based on graded derange- gency exploration for source control but loses valuable

ments in 4 variables that define the systemic inflamma- resuscitation time on the operating room table with on-

tory response syndrome: heart rate, white blood cell count, going heat, intravenous volume, and blood loss. In this

temperature, and respiratory rate. The ranges for these context, our practice has focused more on damage-

4 variables are based on the Acute Physiology and Chronic control surgery in the setting of septic shock. We have

Health Evaluation II scoring system.21 Our initial expe- used this concept for patients with de novo intra-

rience with this tool in our SICU showed promising re- abdominal sepsis and patients with postoperative ab-

sults. The tool yielded a sensitivity of 96.5%, a specific- dominal complications requiring surgery. Of note, this

ity of 96.7%, a positive predictive value of 80.2%, and a surgery is performed for only those patients with signifi-

negative predictive value of 99.5%. In addition, sepsis- cant physiologic derangements and predefined risk fac-

related mortality decreased from 35.1% to 23.3%.8 On tors. We continue to further delineate these risk factors

the basis of this experience, we have expanded use of the and physiologic cutoffs for truncated laparotomy with

tool to our surgical ward and are currently evaluating its the goal of decreasing the morbidity and mortality of sur-

applicability in the non-ICU setting. gical sepsis even further. By incorporating damage-

Although implementing mandatory sepsis screening control surgery into our established sepsis resuscitation

on the inpatient surgical floor is likely to improve the early protocol, we are maximizing the paradigm of early goal-

recognition of sepsis and allow for implementation of ap- directed sepsis management for our surgical patients.

propriate evidence-based care, implementing a system- We identified some limitations involved with work-

wide screening protocol would require a significant ing with the NSQIP data set. The first limitation is the

amount of health care resources. By identifying risk fac- NSQIP definitions for sepsis and septic shock. The Ameri-

tors for the development of sepsis and septic shock in can College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care

general-surgery patients, we can better allocate the avail- Medicine consensus conference definitions of sepsis, se-

able resources and focus screening on those patients most vere sepsis, and septic shock9 were developed in an at-

likely to develop sepsis and/or septic shock. Previously tempt to standardize patient classification. However, the

identified risk factors for early death from sepsis delin- NSQIP definitions deviate from these consensus confer-

eated by a French ICU group include low blood pH, shock, ence standards. Within the NSQIP data dictionary there

preexisting liver or cardiac insufficiency, and hypother- is no definition for severe sepsis. Instead, patients with

mia.22 In addition, a recent epidemiologic study23 of pa- severe sepsis are classified into the septic-shock cat-

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 7), JULY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM

698

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 08/12/2018

egory in the NSQIP. This misclassification of patients ciation; November 11, 2009; San Antonio, Texas; and is

makes it difficult to compare NSQIP patients with those published after peer review and revision. The discus-

from other data sets. However, this phenomenon is con- sions that follow this article are based on the originally

sistent with our experience: it is sometimes difficult to submitted manuscript and not the revised manuscript.

differentiate severe sepsis and septic shock. The second

limitation is related to lack of data regarding cause of REFERENCES

death. Although the NSQIP reports mortality, there is not

a defined category for cause of death. This makes it im- 1. Hope WW, Demeter BL, Newcomb WL, et al. Postoperative pulmonary embo-

possible to determine whether patients in the data set died lism: timing, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Surg. 2007;194(6):

814-818.

as a result of sepsis or septic shock or from another cause. 2. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR; Centers for Disease

That is true of other large data sets: it is difficult to know Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Com-

the ultimate cause of mortality in patients with multiple mittee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Am J Infect Control.

organ failure. 1999;27(2):97-134.

This study demonstrates that the incidence of sepsis 3. Sands KE, Bates DW, Lanken PN, et al; Academic Medical Center Consortium

Sepsis Project Working Group. Epidemiology of sepsis syndrome in 8 academic

and septic shock far exceeds that of MI and PE in general- medical centers. JAMA. 1997;278(3):234-240.

surgery patients. In addition, case mortality rates in pa- 4. Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR.

tients with sepsis and septic shock exceed those of MI Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, out-

and PE combined by nearly 10-fold. Therefore, our level come, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303-1310.

5. Dombrovskiy VY, Martin AA, Sunderram J, Paz HL. Rapid increase in hospital-

of vigilance in identifying sepsis and septic shock needs ization and mortality rates for severe sepsis in the United States: a trend analy-

to mimic, if not surpass, our vigilance for identifying MI sis from 1993 to 2003. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1244-1250.

and PE. By identifying 3 major risk factors for the devel- 6. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al; Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative

opment of and death from sepsis and septic shock in gen- Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic

eral-surgery patients, we can heighten our awareness for shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377.

7. Nguyen HB, Corbett SW, Steele R, et al. Implementation of a bundle of quality

sepsis and septic shock in these at-risk populations. The indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is asso-

implementation of mandatory sepsis screening for these ciated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1105-1112.

high-risk populations has resulted in decreased sepsis- 8. Moore LJ, Jones SL, Kreiner LA, et al. Validation of a screening tool for the early

related mortality within our institution. Further evalu- identification of sepsis. J Trauma. 2009;66(6):1539-1547.

9. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al; The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Com-

ation of the role of sepsis screening programs in other mittee. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of in-

settings is critical and could significantly reduce sepsis- novative therapies in sepsis. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644-1655.

related mortality in general-surgery patients. 10. American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

ACS NSQIP User Guide for the 2008 Participant Use File. Chicago, IL: American

Accepted for Publication: March 11, 2010. College of Surgeons; 2008: 28, 31.

11. Global Database on Body Mass Index. World Health Organization Web site. http:

Correspondence: Laura J. Moore, MD, Department of Sur- //www.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html. Accessed February 19, 2009.

gery, The Methodist Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical Col- 12. Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with bi-

lege, 6550 Fannin St, Smith Tower 1661, Houston, TX nary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706.

77030 (ljmoore@tmhs.org). 13. Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism:

the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest.

Author Contributions: Drs L. J. Moore, F. A. Moore, 2004;126(3)(suppl):338S-400S.

Todd, and Jones had full access to all the data in the study 14. Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al; ACC/AHA TASK FORCE MEMBERS.

and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care

the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and de- for noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of

sign: L. J. Moore, F. A. Moore, Jones, and Turner. Acqui- Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writ-

ing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular

sition of data: Jones, Turner, and Bass. Analysis and in- Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): developed in collaboration with the Ameri-

terpretation of data: L. J. Moore, F. A. Moore, Todd, Jones, can Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart

and Turner. Drafting of the manuscript: L. J. Moore, F. A. Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Car-

Moore, and Jones. Critical revision of the manuscript for diovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and

Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-

important intellectual content: L. J. Moore, F. A. Moore, 1996.

Todd, Jones, Turner, and Bass. Statistical analysis: Jones. 15. Improving America’s Hospitals. The Joint Commission’s Annual Report on Qual-

Administrative, technical, and material support: Todd, Jones, ity and Safety 2007. www.jointcommissionreport.org/pdf/JC_2007_Annual

Turner, and Bass. Study supervision: L. J. Moore, F. A. _Report.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2009.

Moore, and Turner. 16. Horan TC, Culver DH, Gaynes RP, et al; National Nosocomial Infections Surveil-

lance (NNIS) System. Nosocomial infections in surgical patients in the United

Financial Disclosure: None reported. States, January 1986–June 1992. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14(2):

Funding/Support: This study was supported by The Meth- 73-80.

odist Hospital Research Institute, Houston, Texas. 17. Bruce J, Russell EM, Mollison J, Krukowski ZH. The measurement and moni-

Disclaimer: The American College of Surgeons National toring of surgical adverse events. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(22):1-194.

18. Owens CD, Stoessel K. Surgical site infections: epidemiology, microbiology and

Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospi- prevention. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(suppl 2):3-10.

tals participating in the National Surgical Quality Improve- 19. Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL Jr, et al. Estimating health care-

ment Program are the source of the data used herein; they associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;

have not verified and are not responsible for the statisti- 122(2):160-166.

cal validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived 20. Sucher JF, Moore FA, Todd SR, Sailors M, McKinley BA. Computerized clinical

decision support: a technology to implement and validate evidence based

by the authors. guidelines. J Trauma. 2008;64(2):520-537.

Previous Presentation: This paper was presented at the 21. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of dis-

117th Scientific Session of the Western Surgical Asso- ease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818-829.

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 7), JULY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM

699

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 08/12/2018

22. Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J, et al; French ICU Group for Severe Sepsis. 3. You documented 3 risk factors for higher mortality: age

Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: older than 60, any comorbidity, and the need for emergency

a multicenter, prospective study in intensive care units. JAMA. 1995;274(12): surgery. None of these seem to be of the nature or sort that

968-974.

we as clinicians can affect. And perhaps the emergency sur-

23. Aydogdu M, Gursel G. Predictive factors for septic shock in patients with ventilator-

associated pneumonia. South Med J. 2008;101(12):1222-1226.

gery was in fact done to treat sepsis or a closed-space infec-

24. Vogel TR, Dombrovskiy VY, Lowry SF. Trends in postoperative sepsis: are we tion. So what then should we do with this information of risk

improving outcomes? Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2009;10(1):71-78. factors?

25. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revi- 4. Since NSQIP is meant to be a quality improvement/

sion (ICD-9). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1977. quality assurance analysis, can you provide any information on

the quality of care for those patients who developed sepsis or

septic shock? Were they effectively treated? Did they receive

DISCUSSION

the correct and timely antibiotics? Was there timely surgical

management of closed-space infections?

Gregory J. Jurkovich, MD, Seattle, Washington: Drs Moore

I appreciate the effort gone into the analysis of the NSQIP

and colleagues have shown us compelling data from the Ameri-

database and the recognition of the limitations that can and do

can College of Surgeon’s NSQIP demonstrating that sepsis and

occur with any and all administrative databases. This is an-

septic shock are a significant problem in the surgical patient. This

other example of the power of large numbers, as it gives us good

likely comes as no surprise to any surgeon in this audience. What

insight into the magnitude of the problem of sepsis in the sur-

may be more surprising is the severity of the problem. Overall,

gical patient.

nearly 4% of the 363 000 patients analyzed over this 3-year time

Dr Todd: As for your first question, is there a magic bullet?

frame were diagnosed with sepsis or septic shock. This is

Unfortunately, no, but we have developed a sepsis screening

20-fold higher than the 0.2% incidence of pulmonary embolus

tool based on the systemic inflammatory response syndrome

and 15-fold higher than the 0.3% incidence of MI. While these

criteria and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evalu-

data do not necessarily support the contention made in the title

ation II cut points, which is quite effective in our SICU. Our

that sepsis and septic shock are preventable, this frequency alone

SICU patients are screened every 12 hours using this tool. If

supports the argument for better screening, intervention, and treat-

they attain a score greater than or equal to 4, a secondary screen

ment tools. This is particularly so, given that the mortality from

is performed by either a midlevel provider or a surgical resi-

sepsis is 5% and for septic shock a remarkable 33%.

dent. The purpose of this evaluation is to validate the pres-

The authors have suggested they have the answer: a better

ence of an infectious source or not. In evaluating this tool sta-

screening tool for the early diagnosis and more rapid effective

tistically, it has a sensitivity and specificity of more than 90%.

interventions in the treatment of sepsis. But what is this screen-

We are currently evaluating this tool on our surgical wards and

ing tool? Dr Todd, I fear you have left the audience hanging,

assessing its validity.

like a chad, or like an anxious schoolgirl waiting for the text

Your second question addressed the timing of the sepsis (pre-

message, or well — the correct analogy clearly escapes me, but

operative or postoperative). In NSQIP, there is no preopera-

what I am trying to ask is, “Where’s the beef?” Is a magical

tive variable for sepsis, so all of these counts of sepsis are post-

screening tool for the early recognition of impending sepsis really

operative.

available? Is it some propriety formula you plan on market-

What are the sources of sepsis? Unfortunately, that is not

ing? Or is it an embarrassment that you have had to resort to

available in NSQIP.

something so simplistic in your ICU that you hesitate to dis-

Regarding the risk factors we identified as significant, you

cuss it publicly? Like paying attention to an elevated white blood

are correct, we cannot adjust these (their age, their need for an

cell count and fever? Less someone misconstrue my com-

emergency procedure, or their comorbidities). Our objective

ments, I am simply teasing the authors, as they have teased us,

here was to identify a high-risk group for screening in our hos-

and asking them to provide us more information.

pital. We have a 1000-bed hospital and realistically cannot af-

I have the following 4 queries for the authors:

ford to screen every patient every 12 hours. These variables

1. When did sepsis or septic shock occur in these pa- should provide us a narrower scope for focusing our limited

tients? Was it always a postoperative problem, or could it have resources.

been a presenting symptom or diagnosis? This has significant Unfortunately, you are correct; the answer is no. One of the

implications for its recognition and interventions. biggest struggles with the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guide-

2. What was the cause of sepsis? At the very least, can you lines is that clinicians have a difficult time actually interven-

provide us the origin by body regions, such as lungs, gastro- ing and providing the needed therapies in a timely fashion.

intestinal, renal, or soft tissue? Again, this carries significant

implications for diagnosis and treatment. Financial Disclosure: None reported.

(REPRINTED) ARCH SURG/ VOL 145 (NO. 7), JULY 2010 WWW.ARCHSURG.COM

700

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 08/12/2018

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Flat Belly ForeverDokument75 SeitenFlat Belly ForeverSurekaAnand100% (1)

- Gallstone Disease and Acute CholecystitisDokument21 SeitenGallstone Disease and Acute CholecystitisTanyaNganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign Hour 1 BundleDokument5 SeitenSurviving Sepsis Campaign Hour 1 BundleNadine Noelle AgraviadorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes For Healthy Kids - Rujuta DiwekarDokument171 SeitenNotes For Healthy Kids - Rujuta Diwekarindu tiwari100% (6)

- Gall StoneDokument38 SeitenGall Stoneumay83% (6)

- AchalasiaDokument40 SeitenAchalasiaedo andriyanto100% (1)

- Action Plan ExampleDokument6 SeitenAction Plan ExampleAshmal DanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutrition Care Process for Obese Client Seeking Gastric BypassDokument9 SeitenNutrition Care Process for Obese Client Seeking Gastric BypassJohn50% (2)

- FINAL Q4 Eng8 Week1 Module1 Grammatical-Signals-in-Idea-DevelopmentDokument10 SeitenFINAL Q4 Eng8 Week1 Module1 Grammatical-Signals-in-Idea-Developmentrex henry jutaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Informative EssayDokument4 SeitenInformative Essayapi-491520138Noch keine Bewertungen

- OralDokument33 SeitenOraledo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ventricular Septal Defect Complicating ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarctions: A Call For ActionDokument12 SeitenVentricular Septal Defect Complicating ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarctions: A Call For ActionIde Yudis TiyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S2589514123001263 MainDokument6 Seiten1 s2.0 S2589514123001263 MainTenorio Huaman SaucedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Non Cardiac Failure in Cardiogenic Shock PDFDokument11 SeitenAcute Non Cardiac Failure in Cardiogenic Shock PDFAndrew E P SunardiNoch keine Bewertungen

- [19330693 - Journal of Neurosurgery] Patient factors associated with 30-day morbidity, mortality, and length of stay after surgery for subdural hematoma_ a study of the American College of Surgeons National SurgiDokument7 Seiten[19330693 - Journal of Neurosurgery] Patient factors associated with 30-day morbidity, mortality, and length of stay after surgery for subdural hematoma_ a study of the American College of Surgeons National SurgiBruno MañonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 Article 525Dokument8 Seiten2019 Article 525Diane MxNoch keine Bewertungen

- JSR - Deep Learning Risk Model in Vascular SurgeryDokument9 SeitenJSR - Deep Learning Risk Model in Vascular Surgerytaiwandylee24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Salim 2009Dokument6 SeitenSalim 2009raden chandrajaya listiandokoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Thromboprophylaxis Fails Final VDM - 47-51Dokument5 SeitenWhy Thromboprophylaxis Fails Final VDM - 47-51Ngô Khánh HuyềnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oup Accepted Manuscript 2020Dokument10 SeitenOup Accepted Manuscript 2020Luis Bonino SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Journal of Neurosurgery - Spine) Risk Factors For Deep Surgical Site Infection Following Thoracolumbar Spinal SurgeryDokument10 Seiten(Journal of Neurosurgery - Spine) Risk Factors For Deep Surgical Site Infection Following Thoracolumbar Spinal SurgeryEugenia BocaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Predictors of Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks in Endoscopic Surgery For Pituitary TumorsDokument6 SeitenPredictors of Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks in Endoscopic Surgery For Pituitary Tumorsfabian arassiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prehospital Hemostatic Resuscitation To AchieveDokument7 SeitenPrehospital Hemostatic Resuscitation To AchieveMiluska SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- (10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Impact of Preoperative Endovascular Embolization On Immediate Meningioma Resection OutcomesDokument7 Seiten(10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Impact of Preoperative Endovascular Embolization On Immediate Meningioma Resection OutcomesBedussa NuritNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011 SabatéDokument12 Seiten2011 SabatéLuis CordovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complications Predicting Perioperative Mortality in Patients Undergoing Elective Craniotomy A Population Based StudyDokument11 SeitenComplications Predicting Perioperative Mortality in Patients Undergoing Elective Craniotomy A Population Based Study49hr84j7spNoch keine Bewertungen

- Completion of The Updated Caprini RiskDokument10 SeitenCompletion of The Updated Caprini RiskPaloma AcostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevenção de IraDokument21 SeitenPrevenção de IrajoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis in The Neurosurgical PatientDokument8 SeitenDeep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis in The Neurosurgical PatientIRMÃOS FOREVERNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Epistaxis in Patients With Ventricular Assist Device: A Retrospective ReviewDokument6 SeitenManagement of Epistaxis in Patients With Ventricular Assist Device: A Retrospective ReviewDenta HaritsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Readmission and Other Adverse Events After Transsphenoidal Surgery: Prevalence, Timing, and Predictive FactorsDokument9 SeitenReadmission and Other Adverse Events After Transsphenoidal Surgery: Prevalence, Timing, and Predictive FactorsbobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety of Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization For Treatment of Subdural Hematoma - A Nationwide Propensity Score Matched AnalysisDokument10 SeitenSafety of Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization For Treatment of Subdural Hematoma - A Nationwide Propensity Score Matched AnalysisJUANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reiner2017 PDFDokument8 SeitenReiner2017 PDFjessicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bernard D. Prendergast and Pilar Tornos: Surgery For Infective Endocarditis: Who and When?Dokument26 SeitenBernard D. Prendergast and Pilar Tornos: Surgery For Infective Endocarditis: Who and When?om mkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Predictor y Resultados en Pacientes Con SepsisDokument4 SeitenPredictor y Resultados en Pacientes Con SepsisLoreto ConchaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acta Colombiana Cuidado IntensivoDokument12 SeitenActa Colombiana Cuidado IntensivoDra Diana BermudezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pi Is 2666501823003379Dokument10 SeitenPi Is 2666501823003379Raja Alfian IrawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0022480422008150 MainDokument11 Seiten1 s2.0 S0022480422008150 MainYodi SoebadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intraoperative Cardiac Arrests in Adults.20Dokument9 SeitenIntraoperative Cardiac Arrests in Adults.20Werner Ruben Granados NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Vascular Surgery Response To The COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of A Nationwide SurveyDokument9 SeitenEarly Vascular Surgery Response To The COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of A Nationwide SurveyAji Prasetyo UtomoNoch keine Bewertungen

- RVM y MedistinitisDokument5 SeitenRVM y MedistinitisMartha CeciliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: Review Topic of The WeekDokument9 SeitenContrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: Review Topic of The WeekreioctabianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal TutKlinDokument9 SeitenJurnal TutKlinFadhil AbdillahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Extending The Limits of Reconstructive Microsurgery in Elderly PatientsDokument7 SeitenExtending The Limits of Reconstructive Microsurgery in Elderly PatientsroyvillafrancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Kidney Injury and Risk of Death After.27 PDFDokument8 SeitenAcute Kidney Injury and Risk of Death After.27 PDFtasya claudiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 325 FullDokument20 Seiten325 FullDessyadoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiothoraciccritical Care: Kevin W. Lobdell,, Douglas W. Haden,, Kshitij P. MistryDokument24 SeitenCardiothoraciccritical Care: Kevin W. Lobdell,, Douglas W. Haden,, Kshitij P. MistryShahzad Muneer ShahzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Upper Extremity Venous Thromboembolism Following ODokument7 SeitenUpper Extremity Venous Thromboembolism Following ODeborah SalinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthesia Needs Large International Clinical Trials: Mcmaster University, Ontario, CanadaDokument4 SeitenAnesthesia Needs Large International Clinical Trials: Mcmaster University, Ontario, Canadaserena7205Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Diabetes Mellitus On Surgical Site Infections After Colorectal and Noncolorectal General Surgical OperationsDokument6 SeitenThe Effect of Diabetes Mellitus On Surgical Site Infections After Colorectal and Noncolorectal General Surgical OperationsAna MîndrilăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Picot Synthesis SummativeDokument14 SeitenPicot Synthesis Summativeapi-259394980Noch keine Bewertungen

- 01 - Cost of AKIDokument7 Seiten01 - Cost of AKIFloridalma FajardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1016@j Surg 2019 04 034Dokument7 Seiten10 1016@j Surg 2019 04 034amelia henitasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simplified Frailty Index As A Predictor of Adverse Outcomes in Total Hip and Knee ArthroplastyDokument6 SeitenSimplified Frailty Index As A Predictor of Adverse Outcomes in Total Hip and Knee ArthroplastyJohn SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trauma Bazo Art 3Dokument7 SeitenTrauma Bazo Art 3Javi MontañoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strokeaha 116 016162Dokument7 SeitenStrokeaha 116 016162Clepsa VictorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stroke Dari AhaDokument7 SeitenStroke Dari AhaFia Delfia AdventyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Care Nephrology Core Curriculum 2020 PDFDokument18 SeitenCritical Care Nephrology Core Curriculum 2020 PDFMartín FleiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prognostic Role of Pre-Operative Symptom Status in Carotid Endarterectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDokument9 SeitenPrognostic Role of Pre-Operative Symptom Status in Carotid Endarterectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisFrancisco Álvarez MarcosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Operative Management of Anastomotic Leaks After Colorectal SurgeryDokument6 SeitenOperative Management of Anastomotic Leaks After Colorectal SurgeryJorge OsorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thromboprohylaxis and DVT in Surgical PRDokument7 SeitenThromboprohylaxis and DVT in Surgical PRAhmed MohammedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deep Sternal Wound Infections: Evidence For Prevention, Treatment, and Reconstructive SurgeryDokument12 SeitenDeep Sternal Wound Infections: Evidence For Prevention, Treatment, and Reconstructive Surgerylsintaningtyas100% (1)

- Impact of Microbial Findings On PlasticDokument6 SeitenImpact of Microbial Findings On PlasticFebrian Parlangga MuisNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review On The Biomechanics of Coronary ArteriesDokument62 SeitenA Review On The Biomechanics of Coronary ArteriesAbhishek KarmakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0914508719303648 MainDokument6 Seiten1 s2.0 S0914508719303648 MainMarina UlfaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bone Cement Implantation Syndrome: A. J. Donaldson, H. E. Thomson, N. J. Harper and N. W. KennyDokument11 SeitenBone Cement Implantation Syndrome: A. J. Donaldson, H. E. Thomson, N. J. Harper and N. W. KennyUfuk TuranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 736 1464 1 SMDokument5 Seiten736 1464 1 SMDr Meenakshi ParwaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- SDH MMA EmbolDokument8 SeitenSDH MMA EmbollokeshvdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary Management of Sigmoid VolvulusDokument8 SeitenContemporary Management of Sigmoid VolvulusWILLIAM RICARDO EFFIO GALVEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesVon EverandCritical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesDmitri BezinoverNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atherosclerosis: Clinical Perspectives Through ImagingVon EverandAtherosclerosis: Clinical Perspectives Through ImagingNoch keine Bewertungen

- SH 10 MSK RF Colles FractureDokument9 SeitenSH 10 MSK RF Colles Fractureedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abdominal TB: A Review of Clinical Features, Investigations and ManagementDokument10 SeitenAbdominal TB: A Review of Clinical Features, Investigations and ManagementMade Oka HeryanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ca Colon D Vs SDokument7 SeitenCa Colon D Vs Sedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ChenDokument9 SeitenChenedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- UpdateDokument1 SeiteUpdateedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 LeCompteMay1 SplenicTraumaMgmtDokument80 Seiten2013 LeCompteMay1 SplenicTraumaMgmtedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 LeCompteMay1 SplenicTraumaMgmtDokument21 Seiten2013 LeCompteMay1 SplenicTraumaMgmtIrfan Dzakir NugrohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- GastricDokument3 SeitenGastricedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- HenryDokument1 SeiteHenryedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prognostic Factor For LynchDokument7 SeitenPrognostic Factor For Lynchedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- HenryDokument1 SeiteHenryedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 708 1323 1 SMDokument9 Seiten708 1323 1 SMedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- FreeDokument7 SeitenFreeedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fluconazole For SepsisDokument13 SeitenFluconazole For SepsisLintang AdhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sobreviviendo A La Sepsis 2016 PDFDokument74 SeitenSobreviviendo A La Sepsis 2016 PDFEsteban Parra Valencia100% (1)

- SevereDokument8 SeitenSevereedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SepsisDokument6 SeitenSepsisedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manajemen Sepsis - SSCDokument8 SeitenManajemen Sepsis - SSCDeborah Bravian TairasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basal Cell CarcinomaDokument19 SeitenBasal Cell Carcinomaedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prognostic Factor For LynchDokument7 SeitenPrognostic Factor For Lynchedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ca Colon D Vs SDokument7 SeitenCa Colon D Vs Sedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vicky, Stoma Care, SSU 2018Dokument46 SeitenVicky, Stoma Care, SSU 2018edo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01-05-05 LO App - DR SigitDokument49 Seiten01-05-05 LO App - DR Sigitedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Splenectomy in Pediatric Trauma Case PresentationDokument46 SeitenSplenectomy in Pediatric Trauma Case Presentationedo andriyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epidimiological ApprochDokument14 SeitenEpidimiological ApprochBabita DhruwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obesity Is A Familial DisorderDokument4 SeitenObesity Is A Familial Disordernatasha karlinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutrition: Pregnancy AND Lactation: Enriquez R. Cayaban, RN, LPT, MANDokument44 SeitenNutrition: Pregnancy AND Lactation: Enriquez R. Cayaban, RN, LPT, MANCarl Josef C. GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fatal Fat: A Two Inch Tongue Can Kill A Six Feet ManDokument3 SeitenFatal Fat: A Two Inch Tongue Can Kill A Six Feet ManSumedha SunayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes and Pregnancy An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline ProvideDokument76 SeitenDiabetes and Pregnancy An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline Providediabetes asiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pe Midterm ReviewerDokument24 SeitenPe Midterm ReviewerAngelique CaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Omron Scale HBF 400Dokument24 SeitenOmron Scale HBF 400Lucy Fernanda MillanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Police Shift Work Linked to Health RisksDokument64 SeitenPolice Shift Work Linked to Health RisksvilladoloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Obesity: Improvement of Health-Care Training and Systems For Prevention and CareDokument13 SeitenManagement of Obesity: Improvement of Health-Care Training and Systems For Prevention and CareCarola CuervoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 IMDokument76 SeitenChapter 1 IMsdgafd100% (1)

- World Health Organization - Cancer Country Profiles, 2014Dokument2 SeitenWorld Health Organization - Cancer Country Profiles, 2014Ana BarbosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Big Persons, Small Voices: On Governance, Obesity, and The Narrative of The Failed CitizenDokument17 SeitenBig Persons, Small Voices: On Governance, Obesity, and The Narrative of The Failed Citizenlaurapc55Noch keine Bewertungen

- Insulin Resistance and PrediabetesDokument8 SeitenInsulin Resistance and Prediabetesant beeNoch keine Bewertungen

- PESTEL AnalysisDokument14 SeitenPESTEL AnalysisSreeman RevuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pros and Cons of Video GamesDokument4 SeitenPros and Cons of Video GamesPerla FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pyms User and Info GuideDokument28 SeitenPyms User and Info GuideMatthew NathanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research ProtocolDokument6 SeitenResearch ProtocolMike MichaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ôn Tập Chương Trình Mới Unit 10: Healthy Lifestyle And LongevityDokument10 SeitenÔn Tập Chương Trình Mới Unit 10: Healthy Lifestyle And LongevityMinh NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fitness Plan Template For ExcelDokument2 SeitenFitness Plan Template For ExcelPRONITS SARLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Practice With Peer Evaluation - Valeria de La Peña A01088765Dokument5 SeitenIndividual Practice With Peer Evaluation - Valeria de La Peña A01088765Valeria de la PeñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aip-Mtpa-Smea 2017-2018Dokument27 SeitenAip-Mtpa-Smea 2017-2018ISABEL GASESNoch keine Bewertungen

- MDP Class VIII (FIRST+)Dokument2 SeitenMDP Class VIII (FIRST+)Legend CrimeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Akash BhaiyaDokument56 SeitenAkash Bhaiyasai project50% (2)

- Obesity Project 2021Dokument16 SeitenObesity Project 2021JIESSNU A/L ANBARASU MoeNoch keine Bewertungen

![[19330693 - Journal of Neurosurgery] Patient factors associated with 30-day morbidity, mortality, and length of stay after surgery for subdural hematoma_ a study of the American College of Surgeons National Surgi](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/722525704/149x198/264ee18e78/1712965540?v=1)