Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Hyperactivity and Attention Disorders of Childhood. Second Edition

Hochgeladen von

Jhoana BelloOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hyperactivity and Attention Disorders of Childhood. Second Edition

Hochgeladen von

Jhoana BelloCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hyperactivity and Attention Disorders of Childhood.

Second Edition

Seija Sandberg, editor. Cambridge University Press, NYC, 2002. 504 pp. $65.00 USA.

If you haven’t kept abreast of developments in the area of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and would like a relatively quick

yet comprehensive update this book is probably for you. Moreover, it embodies a balanced perspective between European and North American

viewpoints.

The introductory chapter by Sandberg and Barton is particularly enjoyable. It offers a detailed and well-referenced tour de force of the

historical developments in syndrome definition and characterization, as well as attributed causality over the course of the past one hundred

and fifty years. Chapters 2 and 5 addressing epidemiological aspects and classification issues respectively should be read side-by-side. There

is a substantial degree of overlap between these two chapters; albeit, on a positive note, the content is complementary and provides a good

contextual understanding of how we got to the current classifications in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, IV Ed. and the International

Classification of Diseases, 10th Ed.

Chapter 9 is a well-written account of developments in genetics of ADHD, comprising a discussion of progress in genetic epidemiology and

molecular genetics ending with a knowledgeable discussion of future directions. In Chapter 10 a comprehensive insight into the neurobiology

of ADHD addressing recent developments in brain imaging, neurophysiology, chemistry and neuropharmacology of the disorder is presented in

less than 20 pages. Chapters 6 and 7 are also complementary: the first one addresses the neuropsychology of attention from an experimental

psychology point of view and the latter addresses the relationship between ADHD and learning disorders. Chapter 4 discusses gender differences

and their significance in the identification of ADHD “caseness.” Attempts were made to incorporate developmental and psychosocial perspectives;

however, in contrast to biologically informed chapters, it became clear that there is ample room for progress in these areas.

The main weakness of the book is the relative lack of information pertaining to therapeutic interventions. Chapter 13 is devoted to the

Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) study as a model of treatment; however, the book fails to address therapeutic options in the context of

developmental changes, and a broader discussion of management strategies would have increased its usefulness.

Overall, while parents and lay readers may find the text to be too technical and detailed, this is a good book, It is best suited for mental

health professionals seeking a deeper understanding of the syndrome and has some excellent chapters..

Abel Ickowicz, MD

The Development of Emotional Competence

Carolyn Saarni. The Guilford Press, NYC, 1999. 381 pp. $21.95 USA.

Carolyn Saarni’s book is one of a very practical series of titles by Guilford Press examining emotional and social development. The author

stated a number of goals for the book including: writing about emotional development in mid-childhood and adolescence, examining emotion as

a part of culture, and establishing a pattern of studying emotion within the lives of children. The book was organized into three parts: research

and theories of emotional competence; skill levels of emotional competence and the clinical application of emotional competence.

In the first part, Dr. Saarni defined emotional competence as the functional capacity wherein a human can reach their goals after an emotion-

eliciting encounter. She defined emotion as a building block of self-efficacy. She described the use of emotions as a set of skills achieved which

then lead to the development of emotional competence. Attainment of the skills of emotional competence is crucial to self-efficacy. Dr. Saarni

outlined her theoretical position in relation to theories of emotion and social learning and cognitive development. Her approach to theory in

each of these fields was integrative and focussed on self-development with a strong social-contructivist perspective. I enjoyed the culture and

folk theories of emotional regulation in chapter three. Also, chapter three contained an interesting section on parent and peer influences on

emotional regulation, very useful for child psychiatrists who work to discern abnormal emotional regulation and mood patterns in context.

The bulk of the book was devoted to the eight emotional competence skills:

• Awareness of one’s own emotions,

• Ability to discern and understand other’s emotions,

• Ability to use the vocabulary of emotion and expression,

• Capacity for empathic involvement,

• Ability to differentiate subjective emotional experience from external emotion expression,

• Adaptive coping with aversive emotions and distressing circumstances,

• Awareness of emotional communication within relationships, and

• Capacity for emotional self-efficacy.

Skills one through six are based on developmental research on emotions but the final two skills are based on her experience as a clinical

developmental psychologist. Each chapter contained organizing subtitles and ended with culture, developmental stage and gender information.

In keeping with her leanings to Lewis and Michaelson, her most basic skill, ‘awareness of one’s own emotions,’ is one that requires cognitive

ability. She stipulated that, to accomplish the first skill, (Lewis’ argument) the child must know how the body feels to have an emotion. A

child needs to be age four or five to demonstrate this skill reliably. Of all the skills, skill four, the capacity for empathic involvement appears to

be an outlier. While the material she presented was interesting to read, the role of empathy as a skill of emotional competence wasn’t argued

convincingly. On the other hand, skill 7 had a great deal of face validity. It suggested that there is a skill of emotional meta-communication.

A strength of the book is its comprehensive examination of the skills she proposed. She covered many practical issues in emotional

competence. The book conveyed a strong sense of children in their world and thus it was easy and enjoyable to read. A limitation of the book

related to Dr. Saarni’s description of the differences between the theoretical models and how she applied them. There is a distinct difference

between the social constructivists and functionalists. If child psychiatrists or residents are not familiar with the difference, this book will confuse

their understanding. The former see emotions as arising from the development of cognition and the latter see emotion as not developmentally

dependent upon cognition, rather, an organizing principle in development in its own right. Despite this, the effort and breadth of the treatment

of emotional competence as illustrated in this book makes it well worth the read.

Esther Cherland MD

T h e C a n a d i a n C h i l d a n d A d o l e s c e n t P s y c h i a t r y R e v i e w N o v e m b e r 2 0 0 4 ( 13 ) : 4 12 1

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Emotional Intelligenceresearch PaperspdfDokument5 SeitenEmotional Intelligenceresearch Paperspdfknoiiavkg100% (1)

- Action Research Final Paper 2Dokument16 SeitenAction Research Final Paper 2api-264153257Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On Positive EmotionsDokument5 SeitenLiterature Review On Positive Emotionsafmaadalrefplh100% (1)

- Rhetorical Analysis of Pediatric NursingDokument9 SeitenRhetorical Analysis of Pediatric Nursingapi-402243913Noch keine Bewertungen

- Character Styles Introduction PDFDokument4 SeitenCharacter Styles Introduction PDFKOSTAS BOUYOUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Character Styles IntroductionDokument4 SeitenCharacter Styles IntroductionJose Andres GuerreroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Topics On EmotionsDokument8 SeitenResearch Paper Topics On Emotionsjicjtjxgf100% (1)

- Developmental Psychology Research Paper IdeasDokument7 SeitenDevelopmental Psychology Research Paper Ideasafnkfgvsalahtu100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography - Research Project Enc - Katelyn SmithDokument6 SeitenAnnotated Bibliography - Research Project Enc - Katelyn Smithapi-709160933Noch keine Bewertungen

- Motherhood, Mental Illness and Recovery: Stories of HopeVon EverandMotherhood, Mental Illness and Recovery: Stories of HopeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Play Therapy Literature ReviewDokument4 SeitenPlay Therapy Literature Reviewc5qvh6b4100% (1)

- Literature Review On Emotional StabilityDokument6 SeitenLiterature Review On Emotional Stabilityafmzzqrhardloa100% (1)

- The Logic of Human Mind: Inclduing "Self-Awareness" & "Way We Think"Von EverandThe Logic of Human Mind: Inclduing "Self-Awareness" & "Way We Think"Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Logic of Human Mind & Other Works: Critical Debates and Insights about New Psychology, Reflex Arc Concept, Infant Language & Social PsychologyVon EverandThe Logic of Human Mind & Other Works: Critical Debates and Insights about New Psychology, Reflex Arc Concept, Infant Language & Social PsychologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Healing Power of Anger: The Unexpected Path to Love and FulfillmentVon EverandThe Healing Power of Anger: The Unexpected Path to Love and FulfillmentBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- Psych Exam QuestionsDokument63 SeitenPsych Exam Questionsressejames24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rhetorical Analysis 2Dokument7 SeitenRhetorical Analysis 2api-4023555410% (1)

- Adolescent Depression Literature ReviewDokument8 SeitenAdolescent Depression Literature Reviewc5hzgcdj100% (1)

- PHD Thesis On Emotional Intelligence DownloadDokument5 SeitenPHD Thesis On Emotional Intelligence Downloadmarialackarlington100% (2)

- Research Paper On Your Own Personality TheoryDokument8 SeitenResearch Paper On Your Own Personality Theorynoywcfvhf100% (1)

- PSYCHOLOGY & SOCIAL PRACTICE – Premium Collection: The Logic of Human Mind, Self-Awareness & Way We Think (New Psychology, Human Nature and Conduct, Creative Intelligence, Theory of Emotion...) - New Psychology, Reflex Arc Concept, Infant Language & Social PsychologyVon EverandPSYCHOLOGY & SOCIAL PRACTICE – Premium Collection: The Logic of Human Mind, Self-Awareness & Way We Think (New Psychology, Human Nature and Conduct, Creative Intelligence, Theory of Emotion...) - New Psychology, Reflex Arc Concept, Infant Language & Social PsychologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Language Development Relates to Theory of MindDokument13 SeitenHow Language Development Relates to Theory of MindSanjoy Sarker JoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to be Wise: Dealing with the Complexities of LifeVon EverandHow to be Wise: Dealing with the Complexities of LifeBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Why I Triple Text: A Guide For Understanding Your Borderline Personality Disorder Diagnosis And Improving Your RelationshipsVon EverandWhy I Triple Text: A Guide For Understanding Your Borderline Personality Disorder Diagnosis And Improving Your RelationshipsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- Title: Child Adolescent Development: An Integrated Approach: South African Journal of Psychology - 2003, 33Dokument2 SeitenTitle: Child Adolescent Development: An Integrated Approach: South African Journal of Psychology - 2003, 33Aventis SSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Therapeutic Hypnosis with Children and Adolescents: Second editionVon EverandTherapeutic Hypnosis with Children and Adolescents: Second editionLaurence L SugarmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Psy Chia Try: As Perger Syn Drome. A KlinDokument2 SeitenChild Psy Chia Try: As Perger Syn Drome. A KlinSophieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discourse Analysis Adolescent Psychology Final Draft 1Dokument6 SeitenDiscourse Analysis Adolescent Psychology Final Draft 1api-608462277Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Sensory-Sensitive Child: Practical Solutions for Out-of-Bounds BehaviorVon EverandThe Sensory-Sensitive Child: Practical Solutions for Out-of-Bounds BehaviorBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- The Psychology Of Women - A Psychoanalytic Interpretation - Vol I: A Psychoanalytic Interpretation - Vol IVon EverandThe Psychology Of Women - A Psychoanalytic Interpretation - Vol I: A Psychoanalytic Interpretation - Vol INoch keine Bewertungen

- DR AryanDokument12 SeitenDR AryanJuan SalmasoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Character and the Unconscious - A Critical Exposition of the Psychology of Freud and of JungVon EverandCharacter and the Unconscious - A Critical Exposition of the Psychology of Freud and of JungNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to Study and Understand Anything: Discovering The Secrets of the Greatest Geniuses in HistoryVon EverandHow to Study and Understand Anything: Discovering The Secrets of the Greatest Geniuses in HistoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wiser: The Scientific Roots of Wisdom, Compassion, and What Makes Us GoodVon EverandWiser: The Scientific Roots of Wisdom, Compassion, and What Makes Us GoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Brain has a Mind of its Own: Attachment, Neurobiology, and the New Science of PsychotherapyVon EverandThe Brain has a Mind of its Own: Attachment, Neurobiology, and the New Science of PsychotherapyNoch keine Bewertungen

- (International Texts in Developmental Psychology) Hay, Dale F - Emotional Development From Infancy To Adolescence - Pathways To Emotional Competence and Emotional Problems-Routledge (2019) (Z-Lib.iDokument163 Seiten(International Texts in Developmental Psychology) Hay, Dale F - Emotional Development From Infancy To Adolescence - Pathways To Emotional Competence and Emotional Problems-Routledge (2019) (Z-Lib.iRodrigo HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotional Intelligence: A Psychologist’s Guide to Mastering Social Skills, Improving Your Relationships and Raising Your EQVon EverandEmotional Intelligence: A Psychologist’s Guide to Mastering Social Skills, Improving Your Relationships and Raising Your EQNoch keine Bewertungen

- wp2 Final Portfolio To PostDokument6 Seitenwp2 Final Portfolio To Postapi-320516625Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive Developement EmpathyDokument3 SeitenCognitive Developement EmpathyEdith CCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sex Talk: How Biological Sex Influences Gender Communication Differences Throughout Life's StagesVon EverandSex Talk: How Biological Sex Influences Gender Communication Differences Throughout Life's StagesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Schizophrenia - Sick search engine the brain: Neurotic-psychotic developments: When the soul "googles" and the memory delivers increasingly irrational search resultsVon EverandSchizophrenia - Sick search engine the brain: Neurotic-psychotic developments: When the soul "googles" and the memory delivers increasingly irrational search resultsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verbal Communication EssayDokument4 SeitenVerbal Communication EssayafhbhgbmyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument6 SeitenAnnotated Bibliographyapi-509512766Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Psychedelic Future of the Mind: How Entheogens Are Enhancing Cognition, Boosting Intelligence, and Raising ValuesVon EverandThe Psychedelic Future of the Mind: How Entheogens Are Enhancing Cognition, Boosting Intelligence, and Raising ValuesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Expressing Emotion Myths Realities and TherapeuticDokument2 SeitenExpressing Emotion Myths Realities and TherapeuticpsicandreiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rosas CarlosA Resena Personasaltamentesensibles InglesDokument3 SeitenRosas CarlosA Resena Personasaltamentesensibles InglesJanet Patricia Zacatelco FermanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Topics Child PsychologyDokument8 SeitenResearch Paper Topics Child Psychologyafeekqmlf100% (1)

- Propiedades Psicométricas Del Inventario de TA - 3 EDI-3 en Mujeres Adolescentes de ArgentinaDokument15 SeitenPropiedades Psicométricas Del Inventario de TA - 3 EDI-3 en Mujeres Adolescentes de ArgentinaJhoana BelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colombian Norms for the Neuropsychological Assessment of Children (ENIDokument13 SeitenColombian Norms for the Neuropsychological Assessment of Children (ENIJhoana BelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4th Coffee CharadasDokument108 Seiten4th Coffee CharadasJhoana BelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory IIIDokument16 SeitenMillon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory IIIJhoana Bello100% (2)

- PsycometricPropertiesoftheState TraitDepressionInventoryST DEPinaAdultsofLimaDokument11 SeitenPsycometricPropertiesoftheState TraitDepressionInventoryST DEPinaAdultsofLimaJhoana BelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- PsycometricPropertiesoftheState TraitDepressionInventoryST DEPinaAdultsofLimaDokument11 SeitenPsycometricPropertiesoftheState TraitDepressionInventoryST DEPinaAdultsofLimaJhoana BelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 PBDokument19 Seiten2 PBAna CastañedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Validacion Escala de Estilos de Afrontamiento LazarusDokument17 SeitenValidacion Escala de Estilos de Afrontamiento Lazarusnata_725Noch keine Bewertungen

- Validacion Escala de Estilos de Afrontamiento LazarusDokument17 SeitenValidacion Escala de Estilos de Afrontamiento Lazarusnata_725Noch keine Bewertungen

- Artículo Seminario de CasoDokument16 SeitenArtículo Seminario de CasoJhoana BelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genigraphics Poster Template 36x48aDokument1 SeiteGenigraphics Poster Template 36x48aMenrie Elle ArabosNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCERT Solutions For Class 12 Flamingo English Lost SpringDokument20 SeitenNCERT Solutions For Class 12 Flamingo English Lost SpringHarsh solutions100% (1)

- MATH 8 QUARTER 3 WEEK 1 & 2 MODULEDokument10 SeitenMATH 8 QUARTER 3 WEEK 1 & 2 MODULECandy CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application of Carbon-Polymer Based Composite Electrodes For Microbial Fuel CellsDokument26 SeitenApplication of Carbon-Polymer Based Composite Electrodes For Microbial Fuel Cellsavinash jNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bronchogenic CarcinomaDokument13 SeitenBronchogenic Carcinomaloresita_rebongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Vitae: Name: Bhupal Shrestha Address: Kamalamai Municipality-12, Sindhuli, Nepal. Email: ObjectiveDokument1 SeiteCurriculum Vitae: Name: Bhupal Shrestha Address: Kamalamai Municipality-12, Sindhuli, Nepal. Email: Objectivebhupal shresthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Database Case Study Mountain View HospitalDokument6 SeitenDatabase Case Study Mountain View HospitalNicole Tulagan57% (7)

- Enbrighten Scoring Rubric - Five ScoresDokument1 SeiteEnbrighten Scoring Rubric - Five Scoresapi-256301743Noch keine Bewertungen

- Latihan Soal Recount Text HotsDokument3 SeitenLatihan Soal Recount Text HotsDevinta ArdyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Female and Male Hacker Conferences Attendees: Their Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) Scores and Self-Reported Adulthood ExperiencesDokument25 SeitenFemale and Male Hacker Conferences Attendees: Their Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) Scores and Self-Reported Adulthood Experiencesanon_9874302Noch keine Bewertungen

- Theravada BuddhismDokument21 SeitenTheravada BuddhismClarence John G. BelzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pure Quality Pure Natural: Calcium Carbonate Filler / MasterbatchDokument27 SeitenPure Quality Pure Natural: Calcium Carbonate Filler / MasterbatchhelenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3.5 Lonaphala S A3.99 PiyaDokument9 Seiten3.5 Lonaphala S A3.99 PiyaPiya_TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Teacher and The LearnerDokument23 SeitenThe Teacher and The LearnerUnique Alegarbes Labra-SajolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Urbanization & Urban Community DevelopmentDokument44 SeitenUnderstanding Urbanization & Urban Community DevelopmentS.Rengasamy89% (28)

- Peptan - All About Collagen Booklet-1Dokument10 SeitenPeptan - All About Collagen Booklet-1Danu AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- CANAVAN' and VESCOVI - 2004 - CMJ X SJ Evaluation of Power Prediction Equations Peak Vertical Jumping Power in WomenDokument6 SeitenCANAVAN' and VESCOVI - 2004 - CMJ X SJ Evaluation of Power Prediction Equations Peak Vertical Jumping Power in WomenIsmenia HelenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Materials Science & Engineering A: Alena Kreitcberg, Vladimir Brailovski, Sylvain TurenneDokument10 SeitenMaterials Science & Engineering A: Alena Kreitcberg, Vladimir Brailovski, Sylvain TurenneVikrant Saumitra mm20d401Noch keine Bewertungen

- Transactionreceipt Ethereum: Transaction IdentifierDokument1 SeiteTransactionreceipt Ethereum: Transaction IdentifierVALR INVESTMENTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Financial Accounting Chapter 2 LECTURE - NOTESDokument14 SeitenAdvanced Financial Accounting Chapter 2 LECTURE - NOTESAshenafi ZelekeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ST Veronica Giuliani For OFS PresentationDokument7 SeitenST Veronica Giuliani For OFS Presentationleo jNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Four Principles of SustainabilityDokument4 SeitenThe Four Principles of SustainabilityNeals QuennevilleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Upper Six 2013 STPM Physics 2 Trial ExamDokument11 SeitenUpper Six 2013 STPM Physics 2 Trial ExamOw Yu Zen100% (2)

- 2017 Grade 9 Math Challenge OralsDokument3 Seiten2017 Grade 9 Math Challenge OralsGracy Mae PanganibanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hempathane Topcoat 55219 Base 5521967280 En-UsDokument11 SeitenHempathane Topcoat 55219 Base 5521967280 En-UsSantiago Rafael Galarza JacomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internal Disease AnsDokument52 SeitenInternal Disease AnsKumar AdityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICS Technical College Prospectus 2024 Edition 1Dokument36 SeitenICS Technical College Prospectus 2024 Edition 1samuel287kalumeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plate Tectonics LessonDokument3 SeitenPlate Tectonics LessonChristy P. Adalim100% (2)

- Psyclone: Rigging & Tuning GuideDokument2 SeitenPsyclone: Rigging & Tuning GuidelmagasNoch keine Bewertungen

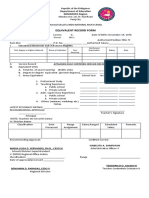

- Equivalent Record Form: Department of Education MIMAROPA RegionDokument1 SeiteEquivalent Record Form: Department of Education MIMAROPA RegionEnerita AllegoNoch keine Bewertungen