Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Downes - Autos Over Rails How US Business

Hochgeladen von

Bruno ReisCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Downes - Autos Over Rails How US Business

Hochgeladen von

Bruno ReisCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Journal of Latin American Studies

http://journals.cambridge.org/LAS

Additional services for Journal of Latin

American Studies:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

Autos over Rails: How US Business

Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910–28

Richard Downes

Journal of Latin American Studies / Volume 24 / Issue 03 / October 1992, pp 551 - 583

DOI: 10.1017/S0022216X00024275, Published online: 05 February 2009

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/

abstract_S0022216X00024275

How to cite this article:

Richard Downes (1992). Autos over Rails: How US Business Supplanted the

British in Brazil, 1910–28. Journal of Latin American Studies, 24, pp 551-583

doi:10.1017/S0022216X00024275

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/LAS, IP address: 138.251.14.35 on 17 Apr 2015

Autos over Rails: How US Business

Supplanted the British in Brazil,

1910—2 8

RICHARD DOWNES

The dynamics of Brazil's transportation sector early in this century reveal

much about how and why US industries conquered the Brazilian market

and-established a sound basis for investment. Especially during the 1920s,

US companies responded to the transportation needs of Brazil's rapidly

growing economy and won the major share of its automobile and truck

markets. This was crucial because of the automobile's central role as a

leading sector of the world's economy during this period. Sales and then

direct investment by US firms in automobile assembly plants placed US

business on a more secure foundation than British investment, prominent

in a sector losing the vitality exhibited in the nineteenth century:

railroads. Rail systems slowed their extension into the immense Brazilian

interior while the automobile flourished, promoted by a powerful

Brazilian lobby for automobilismo reinforced by efforts of US business and

government. This process illustrates how the Brazilians' interpretation of

their economic needs coincided with pressures exerted by US industry to

create a permanent US presence within Brazil's economy. How Henry

Ford replaced Herbert Spencer as the foremost symbol of industrialism in

early twentieth century Brazil sheds light on the personal and political

dynamics of international business competition.1

Rapid economic growth in the early twentieth century thrust a host of

new local and regional demands upon Brazil's woefully inadequate

transportation sector. Capital formation rose without interruption from

1901 onwards and reached very high levels immediately prior to World

War I; more than 11,000 industrial firms producing over 67% of the

economy's 1920 industrial output came into being between 1900 and 1920.

1

'The "leading sector" is that segment of the economy "moving ahead mote rapidly

than the average, absorbing a disproportionate volume of entrepreneurs, [and]

stimulating requirements to sustain it.' Walt W. Rostow, The World Economy: History

& Prospect (Austin, 1978), pp. 104-5, 18 j and 208-9. F° r Spencer's image as a

proponent of industrialism, see Richard Graham, Britain and the Onset of Modernisation

in Brazil, iSjo-1914 (Cambridge, 1968), pp. 236-41.

Richard Downes is Director of Communications, North-South Center, University of

Miami.

]. Let. Amer. Stud. 24, JJ 1-583 Printed in Great Britain 5 51

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5 5 2. Richard Dowries

While the war slowed capital formation, new domestic and foreign

demand created by wartime interruptions in world trading patterns

stimulated increased production in food and textile sectors. For example,

exports of five major commodities (rice, beans, sugar, meat and

manganese) rose from a mere $3 million in 1914 to over $62 million by

1917.2

Growth in the 1920s taxed the transportation system beyond its

capacity. Manufacturing output rose by nearly one-third, with especially

strong increases in chemicals, pharmaceuticals, food products, beverages

and metal products. By the mid-1920*5, Sao Paulo state was experiencing

severe transportation shortages that epitomised the deficiencies of the

existing transportation system. 'The great economic expansion of Sao

Paulo state since 1911' had taxed railroads beyond their capacity: whereas

the railroads had been required to transport only 350,000 sacks of produce

in 1911, by 1924 approximately ten million sacks awaited movement.

Movement of cattle by rail had begun only in 1912 and reached 700,000

head by 1915. By 1924, though, the cattle industry required shipment of

over 2,500,000 head of cattle. Lack of adequate transportation caused sacks

of cereal to 'rot and face the consequences of weather', making farmers

the 'principal victims' of a system unresponsive to their needs.3

Such calamities exposed the turn-of-the-century weaknesses of Brazil's

railroads, inadequate for a more diversified economy because of their

traditional orientation to the fortunes of two principal export crops: coffee

and sugar. In south-central Brazil, most rail systems had been borne with

a single-minded pursuit of coffee's expansion through Rio de Janeiro's

Paraiba Valley and then onto the central plateau during the latter half of

the nineteenth century. In the northeast, railroads depended as heavily on

sugar and focused almost exclusively on serving coastal lowlands in Bahia

and Pernambuco where sugar dominated. Farmers who raised crops in the

vast interior found that' freight rates charged by the railway together with

the costs of reaching the railway' made their use uneconomical, and

cotton growers preferred to hire horses to carry their loads to Recife over

300 miles of 'bridle paths, and often very bad ones at that'. 4

The railroads' strong ties with British entrepreneurs and financiers and

the consequent need to pay dividends and loans in foreign currency

2

Werner Baer, The Brazilian Economy: Growth and Development, 3rd edn. (New York,

1989), pp. 25, 28, 30 and 32. E. Richard Downes, 'The Seeds of Influence: Brazil's

"Essentially Agricultural" Old Republic and the United States, 1910-1930', (PhD

Diss., Univ. of Texas at Austin, 1986), p. 214.

3

Baer, The Brazilian Economy, p. 27; Kevista da Sociedade Rural Brasileira (SRB), vol. 4

(1924), pp. 113-4.

4

John C. Branner, Cotton in the Empire of Brazil: The Antiquity, Methods and Extent of its

Cultivation; Together with Statistics of Exportation and Home Consumption (Washington,

1885), pp. 25-6; Joao Dutra, 0 sertao e 0 centro (Rio de Janeiro, 1938), p. 163. See also

Julian S. Duncan, Public and Private Operation of Railways in Brazil (New York, 1932).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Rails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910-28 553

limited their capacity for expansion. The earliest railroads responded to

government guarantees of a specific return on investment, such as an 1852

law promising a five per cent insured return on investment for approved

railroad projects. Enterprising Brazilians often secured a concession for a

specific railroad project to sell to British interests, and Brazilian railroad

companies obtained loans from British financiers to support expansion.

Railroads proliferated in the 1880s and early 1890s, but by the turn of the

century the sector began to stagnate, forced to pay loans and guaranteed

dividends in currency constantly losing its value relative to the pound.5

The burden of such payments gradually converted the Brazilian

government into a major owner of Brazil's railroads. By 1898 the federal

government devoted a full one-third of its budget to paying the

guaranteed railroad dividends and attempted to remedy the situation by

buying back the railroads. With the 1898 Funding Loan the government

bought 2,100 kilometres of railway, 13 % of the country's rail system, and

in 1901 the government expropriated twelve foreign railway companies.

Between 1901 and 1914 the federal government attempted to lessen its role

in railroad operation by leasing out lines and allowing formation of new

foreign railroad companies, especially the Brazil Railway Company,

formed in 1907. But the November 1914 collapse of Percival Farquhar's

Brazil Railway thrust even more kilometres into the federal and state

governments' domains. Although the government managed to decrease

its operational role, it retained ownership of 61 % of Brazil's railroads in

1914.6

While relieving the state of burdensome payments to foreign

shareholders, state ownership of railroads left them vulnerable to

successful lobbying by special interest groups seeking low freight rates.

Government lines regularly charged lower freight rates than private lines

for beans, corn, coffee, hides and other commodities. As one prominent

state president explained in 1913, 'the State does not necessarily extract a

net profit from its railways' and could in fact operate them ' at cost, at a

loss, or even for free'. While such policy could have stimulated

agricultural diversification in zones already served by railroads, it removed

any incentive for expansion into new areas.7

The tangle of railways emanating fron the coast to the interior

5

See Graham, Britain and the Onset, p. 30. Railroad construction recovered between 1905

and 1913 precisely when the milreis regained some strength against foreign currency.

For exchange rates see Thomas H. Holloway, Immigrants on the Land: Coffee and Society

in Sao Paulo, rSU-ipj4 (Chapel Hill, 1980), p. 181. For annual new railroad

construction, see Brazil, Inspectoria Federal de Estradas de Ferro, Estatistica 1934

(Araguary, Minas Gerais, 1936), p. 45.

6

Steven Topik, 'The Evolution of the Economic Role of the Brazilian State'', Journal of

Latin American Studies, vol. 2 (1979), pp. 336-7.

7

Duncan, Public and Private Operation of Railways, pp. 206-7; R'° Grande do Sul,

Mensagem, p. 50.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5 54 Richard Dowries

prevented efficient shipment of goods in any direction other than between

the interior and the nearest port. The US director of Vic,osa's agricultural

school, P. H. Rolfs, explained how shipping citrus shoots from his school

to the western part of Minas Gerais required intense coordination and a

series of personal favours. At his request, friends in Juiz da Fora

transferred the shoots from the Leopoldina station to that of the Central,

less than ioo metres away. At Barbarcena another friend performed a

similar favour, transferring the shoots to the Oeste de Minas. On one such

transfer expedition, a flock of sheep entered the same freight car as the

citrus shoots and ' en route the hungry animals voraciously devoured the

mudas [shoots] until not enough was left to even justify planting them',

explained an exasperated Rolfs. Transferring a carload of cattle from the

Central to the Leopoldina required an order prepared by the state

president, a situation that Rolfs judged 'an utter waste of time for a man

in his elevated position'. 8

The crisis in Europe's economy and the disruption of trade caused by

the First World War further eroded the sector's efficiency and financial

stability. The high price and inadequate supply of foreign coal and

difficulties of importing engines and rails pushed lines to the brink of

solvency and beyond. In 1918 the Rede Sul Mineira lacked funds for its

payroll, fuel bills, and urgently-needed repairs to its main lines. The

Sorocabana Railway Company also confronted extreme difficulties in

acquiring material, even as its freight traffic increased phenomenally.9

Low freight rates on various lines leased by the government to private

companies prevented even a recovery of the costs of operation, and the

Central also suffered high deficits, attributed to uneconomial rates. The

two state-run railroads in Bahia also reported losses, while only the

British-owned Ilheus-Conquista line registered a clear profit. The Great

Western secured government permission to raise rates to reasonable

levels, but only after promising to contract a 10,000:000 contos de rets ($)

loan to improve its shops and rolling stock. The Leopoldina, enmeshed

in a three-way regulatory pull involving Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro

states and the federal government, registered a 13,000:000 $ loss for

1918.10

In July 1919 the federal inspector of railroads, Joao Pires do Rio,

sketched a bleak image of the state of Brazil's railroads, highlighting the

8

TS (typescript), P. H. Rolfs,'Human Waste', n.d., Box 2, Peter Henry Rolfs Archives,

(PHRA), University of Florida.

9

Duncan, Private and Public Operation of Railways, pp. 70 and 79.

10

'Estradas de ferro', Retrospecto Comercial do Jornal do Comercio (RC do "JC"), 1919,

pp. 127 and 129; John D. Wirth, Minas Gerais in the Brazilian Federation, 1889-1937

(Stanford, 1977), p. 179; USC (US Consul)-Bahia to SS (US Secretary of State), 2 Aug.

1921, 832.77/63, RG 59, US National Archives (USNA).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Kails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910—28 5 5 5

unpleasant fact that federal subsidies sustained most lines. As owner of

5 5 % of the nation's rail system, the federal government had paid out

dividend guarantees of 17,114:703$ in 1918, 60% of which went to the

Sao Paulo—Rio Grande route, a former component of the Brazil Railway.

Only three Sao Paulo lines, the San Paulo, Moygana, and the Paulista, as

well as a portion of the Leopoldina's lines, 'live by their own resources'.

Refusing to recognise the role of special interest groups in lowering

freight revenue, Pires do Rio conveniently blamed the lack of' economic

intensity' in most areas served by the railroads for the system's woes.

'Railroads administered by the government leave deficits; the leasing

companies do not prosper and ask for a revision of their contracts,' while

the private companies receive no federal aid but 'distribute little or no

dividend', he lamented. One solution Pires do Rio proposed was 'a

resolute end to the construction of railroads in Brazil'. Such a

recommendation found a sympathetic ear at the presidency, where

Epitacio Pessoa reasoned that 'since it is no longer possible [to pay] the

guarantee of dividends, I no longer count on rail lines' to provide

transportation to those vast regions without railroads.11

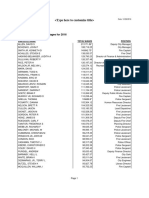

Railway construction withered before such disincentives. As Fig. 1

shows, additions to the system slowed markedly from 1914 onward. From

1915 to 1930, the system grew only an average of 400 kilometres per year,

about one-fourth the average yearly growth rate of the 1909-14 boom

period.

1,600

1,400

1,200

1,000

800

600

400

200

1900 1905 1910 1915 1920 1925 1930

Fig. 1. Rail lines added, kilometres per year, }-year moving averages, ryoo-jo. Source: Brazil,

Inspectoria Federal de Estradas de Ferro, Estatistica tpj</ (Araguary, Minas Gerais, 1936),

p. 45.

11

' O problema ferroviario', RC do "JC", 1919, pp. 130 and 132.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5 j6 Richard Dowries

The Bra^ilian-U.S. road building campaign

With railroad expansion problematical, Brazilians began turning to motor

vehicle transportation — an alternative with important economic advant-

ages. States could opt to construct roads navigable by the primitive, but

durable, vehicles of the time without investing vast sums in rights-of-way,

terminals and rolling stock. Nor did roads require the large overheads of

executive, administrative, secretarial, and other specialists not directly

related to the volume of transportation. Lower capital investment

requirements obviated the search for foreign financing through bur-

densome guarantees and monopolistic concessions, but, like railroad

construction, road building still demanded 'great numbers of workers', as

noted in Augst 1915 by a Northeastern city's municipal council. While

both modes depended upon imported equipment, the lower cost of

motor vehicles made financing easier. From the states' viewpoint, roads

represented an economical way of complementing existing rail systems

and expanding exports to neighbouring states, important because states

received significant revenues from state export taxes during the period.12

Brazil's rural-oriented elite soon recognised the advantages offered by

this new mode of transportation. Automobilismo spawned new social clubs

where members could simultaneously engage in uproarious weekend

adventures and hardheaded lobbying for an improved transportation

system. Automobile clubs founded in Rio de Janeiro in 1908 and Sao

Paulo in 1910 soon pressured public officials to improve the nation's road

system through a series of races and contests.13 Of the 190 founding

12

Roy J. Simpson et al., Domestic Transportation: Practices, Theory, and Policy (Boston:

1990), pp. 62-3; Enrique Cardenas, La industrialisation mexicana durante la Gran

Depresion (Mexico: 1987), p. 161: Joseph Weiss, 'The Benefits of Broader Markets Due

to Feeder Roads and Market News: Northeast Brazil', (PhD Diss., Cornell University,

1971); Letter, Prefeitura Municipal de Garanhuns, Pernambuco, to Inspectoria de

Obras Contra as Seccas, 28 August 1915, M (Maco)-2i;A, Brazilian National Archive.

There appears to have been no empirical comparison of the merits of expanding

Brazil's railroad system versus creating a national highway system. Even today such

comparisons are complex, involving assumptions about pick up and delivery costs,

length of haul, traffic density, energy costs, source of capital, and interest and exchange

rates. See Richard B. Heflebower, ' Characteristics of Transportation Modes', in Gary

Fromme (ed.), Transport Investment and Economic Development (Washington, 1965), pp.

45-6, and Robert T. Brown, 'The "Railroad Decision" in Chile', in ibid., pp. 264-6.

13

Under the Empire provinces and property owners had been responsible for building

and maintaining roads, and hopes for an adequate road system often fell victim to

vague contracts, skimming contractors and the whims of weather. As one account of

the Empire's agricultural experience summarised, 'most highways were mere dirt

paths, poorly designed, that permitted only the passage of mule teams, ox carts, and

horses during the dry season'. Stanley J. Stein, Vassouras: A Brazilian Coffee County,

iSjo-1900 (Cambridge, 1957), pp. 94-110; Eulalia Maria Lahmeyer Lobo, Historia

politico-administrativa da agricultura brasileira, 1808-188) (Brasilia, n.d.), p. 64.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Kails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910-28 557

members of the Sao Paulo club, those with rural ties proved most

numerous, with a full 41 % describing themselves as a farmer [lavrador] or

rancher \fa%endeiro\. Prominent founding member Antonio Prado Junior,

later described as a 'great automobilistic excursionist', roused public

interest by motoring throughout Sao Paulo and Parana and organising a

great 'raid' from Sao Paulo to Ribeirao Preto.14

By 1910 the federal government began to conceive of the automobile

as rail's substitute. A 1910 law authorised concessions, similar to those

offered to railroad companies, to 'persons or private enterprises' to

organise 'a system of transportation of passengers or cargo' between two

states or within one state. As with railroads, the government retained

control over rates and required transport at half-fare of all military

personnel, federal employees, colonists, and immigrants and their

baggage, as well as all government seeds and plants. Further, it required

the concessionaire to construct a telegraph line the length of the road

while reserving any payment until completion of all construction.15

As could be expected under the Old Republic's political structure, state

and local governments took the first hesitant steps toward promoting use

of motor vehicles and highways. A 1911 report prepared for the Minas

Gerais state government dismissed autos as the dominion of tourists, but

nevertheless suggested they could link 'railroad stations with the rural

zones in the region', if studies on a case-by-case basis so warranted. That

same year Rio Grande do Sul constructed 74 kilometres of road, including

a ten-kilometre stretch tapping the rich Vale das Antas. By 1913 the

Companhia Mineira de Auto-Viacao Municipal of Uberaba, Minas Gerais,

was building local roads and planning links with Rio Verde and

Morrinhos in the state of Goias. Minas state agricultural secretary Raul

Soares accepted the concept and created a system of concessions designed

to build roads between 'centres of production' and railroad stations

during his 191410 1917 tenure.16 State president Arturo Bernardes termed

highway construction 'an undisguisable duty of the state' because they

would provide 'an easy and cheap outlet for [agricultural] production'.17

14

Business interests were almost equally represented. See Automovel Club de S. Paulo,

Annuario 1921 (N.P., n.d.), pp. 48-7;.

15

Decree 8,324, 27 Oct. 1910, and 'Regulamento...', Cokcfao das Leis de 1910 (Rio de

Janeiro, 1915), vol. 11, no. 2, p. 1,151.

16

TS, 'Estradas de Rodagem', p. 2, 21 June 1911, 1911.06.21, Arquivo Raul Soares

(ARS); Auto-Propulsao, col. i, no. 7 (1915), p. 9; Minas Gerais, Inspectoria de Estradas

de Rodagem, As estradas de rodagem no estado... (Rio de Janeiro, 1929), p. vii.

17

U.S. Consul, Sao Paulo (USC-SP) to U.S. Secretary of State (SS), jo June 1922,

832.154/33, RG 59, USNA. Rio Grande do Sul, Mensagem, 1912, p. 26; Ernesto

Bertarelli, 'As vias comuns de communicacao nos estados agricolas', 0 Progresso, vol.

i, no. 10 (1914), p. 4; Brasii Industrial, vol. 2, no. 15 (1915), pp. 14-15. Only one per

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5j8 Richard Dowries

Large-scale federal government support for Brazilian highway con-

struction occurred first as a complement to aid for the barren Northeast,

where US technicians urged vigorous road-building programmes through

agreements between state and federal governments. Good roads would

permit the introduction, geologist Roderic Crandall wrote after three

years in Brazil, of the 'four-wheeled wagon... constructed "par excellence"

by the Studebaker company in the United States' as well as tractors and

the 'cargo automobile'. He felt that highways would especially increase

the region's cotton production, citing a cotton-rich zone Taperoa, ioo

kilometres west of Campina Grande, Paraiba, that produced 6,ooo to 8,ooo

bales of cotton yearly beyond the reach of the Great Western. Crandall

applauded road construction already underway in the region, asserting

costs would quickly be recouped by the lowering of shipping costs. He

also endorsed plans for a 160-kilometre road tying the Ceara cities of

Forteleza and Sao Bernardo das Russas as a major improvement over the

existing steamship service and encouraged the introduction of US

wagons, automobiles and tractors to overcome the parched region's

transportation deficiencies.18

The federal government responded to such recommendations and

devastation in the drought area with a more active role in road

construction by funding specific projects. The 1915 federal budget opened

a 5,000:000$ credit line for various roads in Bahia and Paraiba. By the end

of 1918 over 1,175 kilometres of road had been constructed in Pernambuco

state, with over 400 kilometres constructed in 1918 alone.19

The mid-1917 push to increase agricultural production — a campaign to

'make abundance be born from the earth, fortune arise from trade, and

patriotism grow from national unity' - intensified federal support for

road construction.20 Federal and state governments began a cooperative

cent of the Old Republic's 113,000 kilometres of roads were paved by 1930. See Arthur

R. Sheerwood, 'Brazilian Federal Highways and the Growth of Selected Urban Areas',

(PhD Diss., New York University, 1967), p. 30.

18

Crandall also hoped that good roads would lead to broad social change in the

Northeast, where 'a few men of great power hold their positions independent of

justice' while the majority lay 'reduced to poverty or to living as bandits'. Brazil,

Inspectoria de Obras Contra as Seccas, Geografia, geologia, supprimento d'agua, transportes

e afudagem nos estados orient/us do norte do Brasil: Ceara, Rio Grande do Norte, Parabyba

[Roderic Crandall], 2nd edn. (1923; rpt.: Rio de Janeiro, 1977), pp. 54, 55-8, 75 and

129.

19

'Obras contra as seccas', RC do 'JC, 1917, p. 163; USC-Pernambuco to SS, 26 July

1919, 832.154/28, USNA. The federal government also had ordered studies of the Rio-

Petropolis road in 1911 but did not assist reconstruction until the late 1920s. See Decree

8571, 22 Feb. 1911, in M-151, Ministerio de Viacao e Obras Piiblicas, Brazilian

20

National Archive. Quoted in Boletim Agricola, 10 (1916), p. 483.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

A u t o s over Kails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910-28 559

effort to renovate provincial cart roads built during the Empire by

'lengthening of curves, decreasing of gradients and providing modern

systems of draining, surfacing and bridges', as a contemporary explained.

In June 1917 the federal government authorised a 625 :ooo$ (US$156,250)

expenditure to reconstruct the 100-kilometre 'Uniao e Industria' highway

linking Petropolis and Juiz da Fora, originally constructed in 1856. With

contributions from Petropolis and the two states involved, the refurbished

road was to transport products of the region's 'industrial and agricultural

centres'. The 1918 budget for the Ministerio da Agricultura provided

subsidy of two contos de reis per kilometre for firms that would construct

roads suitable for passengers and cargo carried by automobile or trucks.

This law required states to make an equal contribution but omitted the

onerous conditions that had doomed the 1910 legislation. In the next two

years the federal government subsidised building of over 2,300 kilometres

of highways throughout Brazil. The vast majority of the subsidised

highway construction took place in Parana (611 kilometres), where strong

demand for wood, herva mate and cereals 'obliged the government to open

new highways', Minas Gerais (591 kilometres), and Goias, where the only

two roads constructed totalled some 511 kilometres.21

Road construction in the Northeast surged on a crest of high cotton

prices and political favouritism with the 1919 arrival of Epitacio Pessoa to

the presidency, who assured funds for implementation of earlier

recommendations on the need for highways in the Northeast. In August

1919 the Inspectoria de Obras Contra as Seccas began construction of a

275-kilometre road between Natal and Parelhas, Rio Grande do Norte,

and in 1920 began building roads to link smaller towns with existing

highways or railheads. Ironically, this programme fell under control of

Miguel Arrojado Lisboa, former head of the Central do Brasil railroad,

who supervised construction of over 1,700 kilometres of new roads

throughout the Northeast. Private enterprise added to the new system, as

the Sociedade Algodoeira do Nordeste Brasileiro purchased a caterpillar

tractor and repaired 75 kilometres of road to a town deep in Pernambuco's

interior destined to receive a new cotton mill.22

21

Brasil Industrial, vol. 3, no. 29 (1919), p. 49; USACG to SS, 15 June 1918, 832.154/19,

Record Group (RG) 59, USNA; Parana, Secretaria d'Estado dos Negocios, Fazenda,

Agricultura e Obras Piiblicas, Kelatorio, ifiy (Curitiba, 1919), vol. n, pp. 548-9;

Romario Martins, 'As esttadas de rodagem no Parana', Brasil Agrkola, vol. 2 (1917),

pp. 262—4; Parana, Mensagem, 1917, p. 32. 'Estradas de rodagem', Boletim [MAG], vol.

I, no. 3 (1925), p. 391.

22

Brazil, Ministerio de Agricultura, Industria e Comercio (MAG), Kelatorio, 1918, p. 89;

Brazil, Inspectoria Federal de Obras Contra as Seccas, Estradas de rodagem e carrocaveis

construidas no Nordeste Brasileiro pela Inspectoria Federal de Obras Contra as Seccas nos annos

ipip a 192; (Rio de Janeiro, 1927), p. 232; Brazil, Primeiro Congresso Panamericano,

Annex 5; 'Mappa demonstrativa das estradas de rodagem ', 10 Aug. 1925, 10.08.25,

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

560 Richard Dowries

Primitive by current standards, these dusty trails inspired contemporary

praise. A US automobile salesman reported in 1922 that 'in Ceara, in Rio

Grande do Norte and in Paraiba I have found some very good roads... of

good material and very serviceable'. Paraiba's state president declared that

the new highways allowed Paraiba to export to other areas of Brazil cotton

by-products previously fed to local cattle or 'incinerated to clear

warehouse space'. In retrospect, a historian of the region termed the post-

1920 era in Ceara as the 'cycle of the automobile'. Not only did the auto

lift commerce from the backs of animals and extend its scope and

intensity, it revealed to the backwoodsman 'unknown things, new ideas,

new desires, new will, and [these] transfigured him'. 23

The success of these tenuous efforts generated close Brazilian study of

the US highway complex. From Ft. Worth agricultural student Landulpho

Alves wrote to Minister of Agriculture Simoes Lopes that US state and

federal governments were cooperating to create 'thousands and thousands

of kilometres' of roads. Texas alone had allocated US$200,000,000 to

construct highways in one year, partially because of the aid of federal

monies, Alves reported.24 Botanist Carlos Moreira offered a highly

positive if idealised image of US roads upon return from a 1918 mission

to review US agriculture schools and purchase agricultural equipment. US

highways, he noted, were ' perfectly constructed of macadam or concrete'

and 'cross the country in all directions, linking the principal cities with all

the towns', permitting 'an intense traffic over distances like that from Rio

de Janeiro to Manaus'. Jose Custodio Alves de Lima, former consular

agent in the United States and perennial advocate of closer US-Brazilian

economic ties, had attended a convention of road-building interests in

Chicago in 1916. Speaking to Rio de Janeiro's influential engineering

club, he credited the development of the northern nation to its rapid and

inexpensive transportation system while complaining that Brazilians

remained 'prisoners of old and worm-eaten European traditions' and

found 'everything difficult'. Highways would be a boon to rural Brazil

since they would improve mail service, let children live at home and still

attend school, allow for more frequent visits between neighbours, and

permit the farmer to 'cease being an object of curiosity in large towns',

Arquivo lldefonso Simoes Lopes (A1SL). Jose F. Brandao Cavalcanti, 'Em prol do

algodao', A Lavottra, vol. 24 (1920), pp. 269-70.

23

C. P. J. L u c a s , ' T h e G o o d Roads M o v e m e n t in Brazil', Bulletin of the American Chamber

of Commerce, S. Paulo, vol. }, no. 8 (1922), p . 4 ; J o a o Suassuna t o Epitacio Pessoa, 30

Jan. 1925, P-61, AEP; 'As grandes estradas do Nordeste", 0 Automo'vel, 8, no. 101

(1923), pp. 23-5; Raimundo Girao, Histo'ria economics do Ceara (Ceara, 1947), p. 433.

24

Landulpho Alves de Almeida to lldefonso Simoes Lopes, 2; July 1917, pp. 12, 16, 18,

14.12.1j, AISL.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Rails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, if 10-28 561

while selling his goods 'without recourse to middlemen'. To make all this

a reality, Alves de Lima recommended adopting several US road-building

techniques.25

The most important channel for US influence upon Brazil's road

programme, though, was the Good Roads Movement. This agglom-

eration of US road-building interests and government officials lobbied

intensely for federal subsidies for road building to remove the burden

from state treasuries. The American Road Builders Association and the

American Automobile Association, both formed in 1902, and the

American Association for Highway Improvement, established in 1910,

orchestrated an enduring campaign to promote federal support for

highway improvement. Partly by its efforts, the US Congress passed a law

in July 1916 providing federal assistance for building rural roads over

which US mail had to be transported. From a base of $5 million for 1917,

federal appropriations mushroomed to $75 million by 1921.26

A similar Good Roads Movement soon took root and grew in Brazil,

sustained by a nascent highway lobby substantially strengthened by US

ties. Both Rio de Janeiro's Automdvel Club Brasileira and Sao Paulo's

Automdvel Club sponsored national highway conferences in 1916, 1917

and 1919 to pressure public officials to achieve their ends. The Rio de

Janeiro conference, in October 1916, featured prominent roles for

President Braz and his Minister of Transportation and Public Works.

Similar gatherings in Sao Paulo in 1917 and in Campinas two years later

sustained the campaign to convince state officials of the advantages of

highway versus rail transportation.27

The Campinas conference also instituted continuous lobbying for

improving Brazilian highways when prominent politicians and members

of the Automdvel Club created the Associacao Permanente de Estradas de

Rodagem (the Permanent Highway Association), or APER. At its head

stood Washington Luiz Antonio Pereira da Fonseca, first secretary of the

25

'Missao Carlos Moreira', Brazil, MAG, Relato'rio, 1918, p. 254; Jose Custodio Alves de

Lima, Conferemia sobre tstradas de rodagem e aproveitamento dos sentemiados (Sao Paulo,

1917), pp. 10-11 and 15-19.

20

[US] Highway Research Board, Ideas & Actions: A History of the Highway Research

Board, 1920-1970 (Washington, n.d.), pp. 2-3; American Highway Improvement

Association, The Official Good Roads Year book of the United States (Washington, 1912),

pp. 8-2j; Gladys Gregory, 'The Development of Good Roads in the United States',

(M.A. thesis, Univ. of Texas at Austin, 1926), pp. 13-18.

27

Automdvel Club do Brasil, Primeira Exposicao de automobilismo, auto-propulsao e estradas

de rodagem (Rio de Janeiro, 192;), p. 5; Jornal do Commercio [Sao Paulo], 1 June 1917,

p. 4, col. 3; U.S. Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (USBFDC), Motor Roads

in Latin America (Washington, 1925), pp. 129-30; Decree 1707, 13 Sept. 1917,

'Estradas de rodagem', Boletim [Bahia], vol. 1, no. 2 (1917), p. 70; vol. 1, no. 4 (1917),

p. 72.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

562 Richard Downes

Camara Municipal of Sao Paulo and leader of several other national

associations, president, Antonio Prado Junior, vice-president, and Ataliba

Valle, an instructor at the Escola Polytecnica, as secretary. Membership

included several engineers and public works officials who did not own

autos. On the other hand, Jose Cardoso de Almeida, a founding member

of the Automovel Club, owned an auto and had extensive business

interests and political experience as an ex-state and federal deputy, former

director of the Banco do Brasil, and at the time president of the

Companhia Paulista de Seguros, an insurance company. Julio Prestes, at

the time a lawyer and state deputy, also brought several years of

experience with the Automovel Club to the APER's leadership.28

The APER grew quickly and even initiated its own road renovation

programme supported by a broad coalition of commercial interests. By

August 1921 it boasted 5,707 members and was issuing a variety of

propaganda items urging highway construction. The association con-

tracted the repair of 9.5 kilometres between Atibaia and Bragan^a and

another 20 kilometres between Sao Carlos and Descalvado in Sao Paulo,

while gathering endorsements for highways from a wide variety of

individuals and firms. These included 400 members of Sao Paulo's

Associa^ao Commercial and industrial magnate Francisco Matarazzo, who

pledged two contos de reis annually and applauded the association's goals of

building roads to complement and compete with the railroads. The mayor

of Sao Paulo, the Bolsa da Mercadorias (commodities exchange) and the

Sociedade Rural Brasileira also promised to support the APER's

objectives, meanwhile, the APER used its magazine to attack railroads for

requiring 'colossal capital', while highways were 'the most advantageous

solution... to uncover countless hidden riches and awaken a great love for

the natural beauties that make our land a land [that is] singularly

privileged'.29

Significantly, the association also began to gather strength from US

business interests whose goals coincided with those of the APER. The US

Chamber of Commerce established a branch in Sao Paulo in 1920 and

became an active supporter of the APER. Its president William T. Lee

was well-acquainted with the opportunity a good roads movement in

Brazil would provide for US business interests through over a decade of

experience as a founding member of the Automovel Club, former US

consul in Sao Paulo, and as a Sao Paulo businessman. Other officers of the

28

A Estrada de Rodagem, v o l . 1, n o . 1 (1921)1 p . 6 ; A u t o m o v e l C l u b de Sao P a u l o ,

Annuario 1921, p p . 4 9 - 1 6 2 .

29

' A necessidade de e s t r a d a s ' , A Estrada de Rodagem, v o l . 1, n o . 4 (1921), p . 2 1 ; ' A

Sociedade Rurale Brasileira collabora com a A.P.E.R.', Annaes da SRB, vol. 1 (1920),

p. 6; C. A. Monteiro de Barros, 'Pela solidariedade brasileira', A Estrada de Rodagem,

vol. 1, no. 1 (1921), p. 12.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Rails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910-28 563

chamber had more than a passing interest in bettering Sao Paulo's roads.

W. T. Wright, the Chamber's third vice president in 1920 and president in

1922, had years before migrated to Brazil from Maryland, and in 1915 had

established a successful Ford agency in Sao Paulo. An agent for Standard

Oil of Brazil served as one of the Chamber's directors, as did a member

of the Byington Company, Sao Paulo agent for General Motors Trucks,

Cadillac, Buick, Chevrolet and the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company.30

Under Lee's direction the Chamber formed a special committee on

roads at its 31 August 1920 meeting and announced in September that it

had ' taken upon itself to campaign for members' for the APER and hoped

'to interest American capital in improving roads throughout the state'. By

August 1921 every member of the Chamber had also joined the APER,

and the Chamber successfully placed at least one US businessman into the

heart of the road-building programme. L. Romero Samson arrived in

Brazil in 1920 as superintendent of Trading Engineers Incorporated, a

Chicago industrial consulting firm given permission to operate in Brazil

in January 1921. Samson, who claimed to have travelled 30,000 kilometres

within Brazil, soon left the company to use his engineering background

to offer advice on Brazil's road-building programme through the APER's

magazine, A Estrada de Rodagem. The APER then contracted him to

supervise construction of several highways near Sao Paulo.31

The Chamber's influence in the APER gained considerable strength

when the Chamber's general manager and secretary since 1920, Charles M.

Kinsolving, became also secretary of the APER in August 1921.

Kinsolving, son of US Episcopal Bishop in Brazil Lucien Kinsolving, had

returned from World War I service in the Lafayette Escadrille to serve as

the $3,500 per year secretary of the Sao Paulo chamber. He functioned as

secretary for both organisations until August 1922, when he became a

correspondent for a US wire service.32

30

Bulletin of the American Chamber of Commerce, S. Paulo, v o l . i , n o . 1 (1920), p . 1; v o l . 2,

no. ; (1922), p. 36; U.S. Consul, Sao Paulo (USC-SP) to SS, 8 Sept. 1915, pp. 1, 4, 16,

102.1/139 RG 59, USNA; A Evolucao Agrkola, vol. 6, nos. 69-70 (1915), back cover.

Jornaldo Commercio [Sao Paulo], 21 Nov. 21, 1915, p. 9, cols. 2 , 3 ; USC-SP to SS, 1 Sept.

1922, p. 2, 164.12/560, RG 59, USNA. Firestone began to conduct business in its own

right in Brazil in 1923. See Brazil, Ministerio do Trabalho, Industria e Comercio,

Sociedades mercantis autori^adas a functionar no Brasil {1808-11)46) ( R i o d e J a n e i r o , 1947),

p . 134.

31

Bulletin of the American Chamber of Commerce, S. Paulo, v o l . 1, n o . 1 (1920), p . 4 ; v o l . i,

n o . 12 (1921), p . 12; Brazilian—American, v o l . 2, n o . 50 ( O c t . 9, 1920), p . 15 ; L . R o m e r o

S a m s o n , ' O p r o b l e m a da V i a c a o n o B r a s i l ' , A Estrada de Rodagem, v o l . 1, n o . 3 (1921),

p p . 1 3 - 1 4 ; v o l . 1, n o . 4 (1921), p . 2 3 ; See also a d v e r t i s e m e n t , A Estrada de Rodagem,

vol. 1, n o . 2 (1921), inside c o v e r .

32

U S C - S P t o S S , zi J a n . 28, 1920, 6 3 2 . 1 1 1 7 1 / 1 9 , R G 59, U S N A ; Boas Estradas, v o l . 1,

no. 4 (1921), p. 23; Bulletin of the American Chamber of Commerce, S. Paulo, vol. 2, no.

3 (1921), p. 1.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5 64 Richard Downes

The APER also pressed its case for better roads by hosting official

openings for new stretches of highway. On 1 May 1921 the APER helped

open the Sao Paulo-Campinas highway - under construction since 1916

- with a 327-car caravan headed by a presidential committee and festivities

in Campinas, all designed to inform 'a great number of persons of certain

social position and certain above normal intellectual preparation' of the

benefits of such a road. The APER also sponsored a special trip for the

press in April 1922 along the soon-to-be-opened highway between Sao

Paulo and Itu. Popular novelist and essayist Monteiro Lobato participated

in the trip representing the Revista do Brasil. In October 1923 the

association, now renamed the Associagao de Estradas de Rodagem (AER

— the Highway Association), helped to sponsor the third public highways

conference, a six-day-long gathering of the state's mayors, engineers, and

representatives of railroad companies, touring clubs and other interested

parties. Aside from reviewing highway construction carried out since

1917, the nearly 500 participants committed themselves to gathering

information on road conditions and automobile ownership statewide.

They also witnessed an exhibition of road-building machinery and

automobiles - mainly from the United States - and a demonstration

sponsored by the AER of road-building machinery by representatives of

US firms.33

The close relationship between the AER and US business grew even

stronger when a partner in a road-building firm became the secretary of

the AER. D. L. Derrom was a Canadian engineer and partner of

L. Romero Samson in the firm Derrom-Samson, S.A. The company

became ' most instrumental in the introduction and sale of American road-

building equipment and maintenance machinery' in Sao Paulo at the same

time that Derrom served as the AER's secretary. Derrom lobbied heavily

for highway construction through close ties with Washington Luiz, other

key state and local officials, and 'good roads enthusiasts' nationwide, even

authoring a comprehensive programme for Brazilian road construction

entitled Caminhos para 0 Brasil (Roads for Brazil).34

In its campaign to improve Brazil's roads, the AER received valuable

assistance from Washington Luiz. Not only did he serve as the AER's first

president but, as Sao Paulo's state president between 1920 and 1924, he

33

' A estrada de rodagem de S, Paulo a I t u ' , A Estrada de Rodagem, vol. i, no. 11 (1922),

pp. 3 7 - 8 ; USC-SP to SS, 19 Oct. 1923, pp. 2 - 3 , 832.154/36, R G 59, U S N A ; ' T h i r d

Sao Paulo Highway Conference', Bulletin of the Pan American Union (BPAU), vol.

58 (1924), PP. 182-3.

34

USC-SP to SS, 14 Oct. 1926, 832.154/74, RG 59, USNA; Howard T. Oliver to

Fred I. Kent, 5 Feb. 1926, 033.3211/210 (attachment), RG 59, USNA; USC-SP to SS,

10 Oct. 1927, 832.154/86, RG 59, USNA.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Rails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, if 10-28 565

became a powerful advocate of a modern road network. True to his

proclamation to the Sao Paulo state legislature in 1920 that 'we should

everywhere construct highways, all hours of the day, all the days of the

year', he sponsored a 1921 state law outlining a road-building programme

for the state. He also collaborated with the AER in a series of annual

automobile rallies designed to draw attention to the need for better

highways. The first Prova de Turismo featured a circuitous round trip

between Sao Paulo and Ribeirao Preto in 1924, and the next year the rally

promoted the Rio-Sao Paulo highway as twelve cars and trucks negotiated

' hill and mountain... forest, swamp, and prairie' to call for the highway's

completion. As Washington Luiz's prominence increased, his aid became

all the more useful. The year he became national president (1926), he

allowed the rally to carry his name, and the winner of the 1,180-kilometre

race throughout the interior of Sao Paulo carried home the Washington

Luiz cup.35

The Brazilian good roads movement also received a substantial boost

from the US government's support to the 'Pan American Highway

Commission'. This effort was an offshoot of the US Highway Education

Board, a lobby of educators interested in engineering, government

highway officials, and businessmen associated with sales of automobiles

and road-building equipment. Delegates to the Fifth Pan American

Conference at Santiago de Chile, in 1923, suggested forming a Pan-

American Highway Commission to observe the US highway system and

US means of financing, administering, constructing and controlling

modern highways. The National Automobile Chamber of Commerce in

Washington began arranging funding after the notion was endorsed by

the Commerce Department and the Bureau of Public Roads. By December

1923 it had requested $60,000 in contributions from members of the

Highway Education Board, and soon received several pledges of $1,000

or more from 'prominent bankers and leading automotive and road

machinery manufacturers of the United States'.36

Members of the Pan American Highway Commission's executive

committee, named the following month, had strong ties to US automotive

interests. These included Roy D. Chaplin, chairman of the board of

Hudson Motor Car Company, Fred I. Kent, a vice-president of Banker's

Trust of New York, W. T. Beaty, president of Austin Manufacturing

35

' N o t a b l e Automobile Endurance Test in Sao Paulo, Brazil', BPAU, vol. 60 (1926), pp.

I , I 10 a n d 1,117.

36

Pyke Johnson to Francis White, Latin American Div., US Department of State

(USDS), 8 Dec. 1923,515.4C1/-, RG 59, USNA; Walter C. John to SS, 13 March 1924,

515.4C1/27, RG 59, USNA. Dotation Carnegie para la Paz Internacional, Conferencias

internacionales amerkanas, 1889-1936 (Washington, 1938), pp. 214 and 274-5.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5 66 Richard Dowries

Company of Chicago, Thomas H. MacDonald, chief of the Bureau of

Public Roads, F. L. Bishop of the Society for Engineering Education,

Harry S. Firestone, the rubber magnate, and B. B. Bachman of the Society

of Automotive Engineers.37

The conference they organised allowed for convincing lobbying of

Latin American guests, including two prominent Brazilians: Joaquim

Timotheo de Oliveira Penteado, inspector of highways for Sao Paulo

state, and Sampaio Correa, founder of Sampaio Correa e Companhia, an

importer of US coal and, especially, cement. The conference's sponsors

paid for round-trip steamship and rail transportation between Washington

and their city of origin in Brazil as well as all travelling expenses from

assembly of the group in Washington on June z. Once in Washington,

they joined 35 other delegates representing 17 countries for a visit to the

Bureau of Public Roads and an expenses-paid excursion through various

states focusing on highway construction and automobile manufacturing.

Throughout the trip they met with highway engineers, analysts, and

manufacturers of automobiles and road building equipment. Delegate

Penteado accepted invitations to visit the Barber Asphalt Company, the

Baldwin Locomotive Works, the Ingersoll-Rand Company and General

Electric while in New York.38

The Brazilian delegates returned convinced of the benefits of integrating

US equipment and techniques into Brazil's road-building effort. Penteado

reported that Latin American delegates' played the role of students' while

'the role of teachers' belonged to the North Americans because their

country had 'in a few years accomplished what took the Europeans

centuries to carry out'. He viewed the formal presentations and

discussions during meetings, meals and while travelling in trains and

automobiles as ' teachings... of great utility for the other countries'. He

urged adoption of the US example by equipping the state Inspectoria de

Estradas de Rodagem with all the tractors and road machines necessary

for an extensive road construction programme.39

Undoubtedly Penteado also promoted formation of the Confederacao

Brasileira de Educacao Rodoviaria (The Brazilian Highway Education

37

Brazil, Ministerio da Viac^o e O b r a s Publicas, Primeiro Congresso Panamericano de

Estradas de Rodagem: Reiato'rio da Delegacao do Brasil (N.P., 1928), pp. 4 - ; ; Pyke Johnson

to Francis White, Latin American Div., USDS, 8 Dec. 1923, 51J.4C1/-, RG 59, USNA;

Sao Paulo, Secretaria da Agricultura, Commercio e Obras Piiblicas, Commissao Pan-

Americana de Estradas de Rodagem Reunida nos Estados Unidos... (Sao Paulo, 1925), p. 6;

E. S. Gregg, Memo, Transportation Div., Commerce Department, 18 Jan. 1924,

; I ; . 4 C I / 5 , RG 59, USNA.

38

SS to U.S. Embassy, Rio de Janeiro (USE-RJ), 15 March 1924, j i j ^ C i ^ d , RG 59,

U S N A ; Brazil, Primeiro Congresso Panamericano, p p . 6 - 1 1 ; S a o Paulo, Commisao

Panamericana, p . 4 7 .

39

Sao Paulo, Commissao Panamericana, pp. 12, 8 ; and 90.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Kails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910-28 567

Board). Like similar organisations founded in Argentina, Chile, Cuba,

Honduras and Peru following the 1924 tour of the United States, the

Brazilian board sought to ' develop and increase the construction of roads

in all Brazil'. Also prominent in creating the organisation were Theodoro

A. Ramos, a professor at the Escola Polytecnica and A. F. de Lima

Campos, an engineer with considerable road-building experience with the

drought service. Representatives from groups interested in building

highways attended the board's first meeting in Sao Paulo on 20 May 1925:

the Automovel Club, the Sociedade Nacional de Agricultura (National

Agricultural Society), the Ministerio da Via$ao (Ministry of Trans-

portation), the Associacao Commercial de Rio de Janeiro, and the AER.

The board's establishment proved important more in symbolic than in

substantive terms, however. Almost two years after its initial meeting, the

group still lacked a formal charter. Nevertheless, the broad interest in the

group's purpose symbolised the impact of US actions designed to create

support from commerce, agriculture and government for the road-

building movement.40

The US automotive and highway lobby's campaign to encourage

Brazilian adoption of US techniques and machinery took another step

forward with the First Pan-American Highway Conference. This

conference, held in Buenos Aires in May 1925, reinforced messages

imparted at the previous year's meeting in the United States. The US

delegation hoped for approval of a resolution urging a 'permanent

organisation' in each nation to carry on 'the work initiated at the time of

the visit of their delegates to this country last year'. The 33-member US

delegation represented auto industry and road-building interests under

the leadership of a General Motors vice president serving concurrently as

head of the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce. Delegates

included Thomas H. MacDonald, chief of the Bureau of Public Roads, a

strong supporter of the previous year's meeting, and several state highway

officials. Stopping in Rio de Janeiro before the conference, MacDonald

urged Brazil to provide strong federal aid for highway construction, an

act that 'would greatly stimulate and assist development of adequate

highways in Brazil'.41

At least with respect to Brazil, the US delegation accomplished its goals

in Buenos Aires. Brazil's delegation returned convinced of the inadequacy

40

J. Walter Drake [Assistant Secretary of Commerce] to SS, 14 Jan. 1925, 515.4D1 / 1 ,

R G 59, U S N A ; 'Reunioes semanaes da S R B ' , Kevista da SRB, vol. 6, no. 61 (1925), p.

278; 'Brazilian Federation for Highway Education', BPAU, vol. 61, Primeiro Congresso

Panamericano, p. 25.

41

Drake to SS, 25 Jan. 1925, 515.4D1/1, RG 59, USNA; Quoted in Brazil, Primeiro

Congresso Panamericano, p. ii.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

568 Richard Dowries

of the 'old idea, still in vogue in Brazil, that highways were a mere

complement to the railroad'. It endorsed the conference's recom-

mendation that 'all the American nations create a central body to

direct... the reconstruction, maintenance, and financing of highways', and

Brazilian delegate Francisco Vieira Boulitreau played a direct role in

implementing the concept in Brazil. In June 1926 he recommended that

the Ministry of Agriculture propose a comprehensive highway law, to

include provisions for a Departamento Nacional de Estradas de Rodagem

(National Highway Department) with broad authority to plan, finance and

direct Brazil's highway construction.42

Aside from lobbying in international fora for automotive interests, US

government officials frequently reported on good roads movements in

Brazil's various regions. From Pernambuco, US consul C. R. Cameron

informed the State Department and the US Bureau of Foreign and

Domestic Commerce in August 1923 that while the automobile owners

'constitute an element naturally favorable to a good roads movement',

state spending on urban improvements, such as sewer and water works,

had depleted public funds. Nevertheless he also enclosed a list of the

principal automobile dealers in the region, 'the most desirable persons

with whom to communicate regarding the good roads movement', and a

year later reported formation of the Associacao de Estradas de Rodagem,

headed by Pernambuco auto enthusiast Carlos de Lima Cavalcanti. The

group launched a combined automobile show and goods roads congress

in January 1926 that failed to gather a large crowd, however. The consul

attributed this to the fact that' purchasers for automobiles are to be found

almost exclusively among the upper, educated classes'.43

The fervour for automobilismo proved stronger in Rio Grande do Sul. A

Porto Alegre dealership forwarded one per cent of revenue from its sales

of Chevrolets to the AER, suggesting a method of financing the AER that

may have been more widespread. The assistant trade commissioner, a US

official, reported creation of a good roads association in Rio Grande do

Sul in 1926. The Associacao Rio Grandense das Estradas de Rodagem

formed around a nucleus of automobile dealers in Porto Alegre, and

similar associations were 'in the course of formation' in Pelotas, Rio

Grande and Sao Angelo.44

42

Brazil, Primeiro Congresso Panamerkano, p . ii; ' E s t r a d a s de R o d a g e m ' , Boletim [ M A G ] ,

15, 2, no. 4 ( 1 9 2 7 ) , p . 429-

43

USC-Pernambuco to SS, 23 A u g . 1923, 832.154/154, R G 59, U S N A ; USC-Pernambuco

to SS, 11 Feb. 1926, 832.154/67, R G 59, U S N A .

44

The check for 4:872$ represented one percent of receipts from the sale of 50

Chevrolets. General Motors, vol. i, no. 6 (1926), p. 19; Richard C. Long 'Highways in

Rio Grande do Sul', quoted in Brazilian Business, vol. 7, no. 6 (1927), p. 9.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Kails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910-28 569

US businesses played a more direct role in supporting lobbying for

better highways in Rio de Janeiro state. There the Automovel Club do

Brasil, an outgrowth of a civic club founded in Petropolis in 1895, became

the major private lobby for a road-building programme. Like its Sao

Paulo name sake, this group espoused 'the development of automobilismo

and the construction of new highways' and associated goals. Although the

club sponsored the second and third national highway congresses, its

major accomplishment was instigating construction of the Rio de Janeiro

to Petropolis highway. Under the leadership of businessman Carlos

Guinle, the club initiated the project through its own resources and by

1923 had arranged for a 16-kilometre stretch linking Pavuna and Pilar.

Construction of the highway served club members by providing a first-

class road to a traditional resort area, but it also linked up to the

Petropolis—Juiz da Fora road and demonstrated highway-building

techniques and materials while allowing contributors to advertise their

products. The American Rolling Mill company, for example, donated all

culverts needed for the highway. The club soon found voluntary

contributions insufficient, though, and suggested that the federal and Rio

de Janeiro state governments also support the road's completion. In late

1925 the federal government opened a special subsidy for 500:000$ for

that purpose, and on 13 May 1926, the road opened with great fanfare.45

The arrival of US automobile companies

Lobbying by US businesses for good roads in Brazil complemented a

growing acceptance of US vehicles, paving the way for US automotive

manufacturers to establish themselves firmly in Brazil during the Old

Republic's final decade. Before 1917 Brazilians displayed only moderate

interest in US automobiles as French, German and British cars accounted

for nearly 75 % of Brazil's auto imports in 1913. With the war the trend

shifted, as Brazilians imported more US-made cars in 1917 than in the

three previous years combined and imported almost exclusively US-made

autos. This change stemmed partially from the difficulty of trading with

Europe under siege, but it also represented Brazilian affinity for a low-cost

yet durable car. As magazine correspondent Lillian Elliott recorded,' with

the introduction of the inexpensive car of North American build, the

fa^endeiro is acquiring a car for country use'. Even British cotton expert

Arno S. Pearse depended upon a Ford: when departing from Natal on one

of his treks inland, Pearse carried with him on the train 'two Ford motor

45

The Automovel Club was called the Automovel Club Brasileiro until 1919. Automovel

Club do Brasil, Annuario de 1929 (Rio de Janeiro, n.d.), pp. 13 and 16; 'Rio-Petropolis',

0 Automovel, vol. 9, no. 102 (1923), p. 5; 'A Estrada Rio-Petropolis', A Estrada de

Rodagem, vol. 3, no. 28 (1923), p. 40.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5 70 Richard Dowries

cars, the only kind which can be used in country of this nature'. In the

Northeast Ford trucks were converted into buses, and one sertanejo in

Acari, Rio Grande do Norte, even linked the engine of his Ford truck to

a cotton gin and drove from farm to farm ginning cotton for his clients.

A Jesuit who travelled frequently into Goias praised the car and its maker:

' The great North American industrialist, inventor of a car as simple as it

is strong, deserves to be considered one of the greatest benefactors of the

backlands of Goyaz.'46

Impressed by the wartime demand for US-made autos, Ford's

executives soon resolved to open an assembly plant in Brazil. In April

1917 they asked the Brazilian consul in Buffalo to furnish them with laws

on road conditions and maintenance to aid the decision, and on 24 April

1919, approved a capital expenditure of $25,000 to establish an assembly

plant in Sao Paulo. Two company officials experienced in selling Fords in

Argentina hurried to Sao Paulo to arrange for assembling the vehicles'

imported components (only jute to stuff seats would originate in Brazil)

in a refurbished skating rink. Within a year the company began to

construct its own building on Rua Solon, a few metres from where

W. T. Wright had established his successful agency during the war.47

Output at the plant reflected both the increasing popularity of the

vehicles and the soundness of the venture. Production shot up from 2,447

in 1919 to 24,500 in 1925, and earnings totalled $4 million for 1925-6.

Fords became the dominant vehicles in many Brazilian towns. Of the 5 8

automobiles owned in 1921 by residents of Sorocabana, Sao Paulo state's

third largest city, three were Fiats, two were Overlands, one each was a

Hupmobile, Benz, Saurer, Buick, Chevrolet, Adler and Scat. The

46

Brazil, Directoria de Estati'stica Commercial, Commercio Exterior do Brasi/: Importacao,

Exportacao ipij-iy/X (Rio de Janeiro, 1921), vol. t, p. 120; Lillian Elwyn Elliott, Brazil

Today and Tomorrow (New York, 1917), pp. 127-8. Diplomats, however, preferred more

expensive models. In a confidential telegram to the Brazilian Charge in Washington,

Foreign Minister da Gama ordered a draw upon a London account of 56,219.23 to

purchase a Phiama auto for da Gama. Embassy of Brazil, Washington (EBW) to

Ministerio de Relacoes Exteriores (MRE), 4 March 1919, M-232, 2, u , Arquivo

Historico d o Itamarati (AHI). Arno S. Pearse, Brazilian Cotton (Manchester, 1923), p.

141; Inspectoria Federal de Obras Contra as Seccas, Segundo Distrito, T S ,

'Transcripcao de trechos de Relatorios ', P - 6 i , Arquivo Epitacio Pessoa ( A E P ) ;

Camillo Torrend, 'Excursao a Goyaz', Boletim [MAG], vol. 15, no. 6 (1926), p. 770.

47

Noticias Ford, vol. 8, n o . 2 (1979), p . 3 ; Mira Wilkins a n d Frank E . Hill, American

Business Abroad: Ford on Six Continents (Detroit, 1964), p p . 9 3 - 4 . F o r d ' s plant was n o t

the first auto assembly plant in Brazil. In 1904 Luiz and Fortunato Grassi organised a

company that in 1907 assembled the first Fiat to operate in Brazil. The same company

in the 1920s sold both Ford and General Motors truck chasses for their products. See

Jose Almeida, A implantacao da industria automobilistica no Brasil (Rio de Janeiro, 1972),

pp. 4-5, 14; Benedicto Heloiz Nascimento, Formacao da industria automobilistica

brasileira: politico de desenvolvimento industrial em uma economia dependente (Sao Paulo, 1976),

p. 14. 'A expansao do Ford no Brasil', Automobilisma, vol. 1, no. 1 (1926), p. 20.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Kails: How US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910—28 571

remaining 43 were Fords. A similar survey of Pirassununga revealed that,

of the 21 vehicles in the town, one was a Maxwell, two others were

Chevrolets, and 18 were Fords. A later survey in Bahia counted 256 Fords

out of a total of 671 autos. None of the other makes - Overland, Willys-

Knight, Buick, Studebaker, Chevrolet, Dodge, or Essex - had more than

52 of their make registered.48

Brazil's growing affinity for motor vehicles soon attracted a second

major US manufacturer to the Brazilian market. In 1921 the federal

government ordered 50 five-ton trucks with trailers from General Motors,

and the following year James D. Mooney, vice-president of General

Motors Export Corporation, visited Brazil' to study conditions, especially

the motor car industry, with the idea of extending the business of my

corporation'. Significantly, the trip represented the 'first executive of that

corporation who has ever visited a foreign country'. Mooney left 'amazed

at the wonderful possibilities of the motor car industry in this country'

and convinced that 'Brazil will become one of the greatest automobile

countries in the world'. After further study of the Brazilian market, the

General Motors Export Corporation organised a Brazilian subsidiary in

1925 with an investment of $270,000. In a rented warehouse on Avenida

Presidente Wilson in Sao Paulo, the company started assembling 25 units

per day. By the end of 1925, it had put together 5,597 vehicles.49

Both General Motors and Ford became an integral part of the post-war

explosion in motor vehicle ownership in Brazil. A partial survey

conducted in Sao Paulo state in 1929 portrayed the dimensions of a true

invasion of automobiles and trucks. Total vehicles in the state had

increased from 2,661 in 1917 to 59,213 by 1928 - 38,787 autos and 20,426

trucks. In the city of Sao Paulo auto ownership had risen from 1,757 t o

12,366 during this period. Santos and Campinas each had over 1,000 autos

in 1928, roughly ten times what they had had in 1917. Overall vehicle

ownership proved widely dispersed geographically, although Sao Paulo

with 12 % of the state's population in 1920, had 31 % of all autos and 24 %

of total trucks in the state.50 In Minas Gerais the number of vehicles grew

48

Wilkins and Hill, American Business, pp. 146 and 148; A Estrada de Rodagem, vol. 1, no.

4 (1921), p. 11; vol. 1, no. 1 (1921), p. 14.

48

' Um grande acontecimento automobili'stico', 0 Automobilismo, vol. 2, no. 8 (1927), pp.

12-16; TS, General Motors do Brasil, Public Relations Department, 'Curiosidades

histdricas', 1972, p. 4; General Motors do Brasil, Public Relations Department,

'General Motors do Brasil — 57 annos de emprendimento industrial', 1982, p. 1, both

in Arquivo, General Motors do Brasil, Sao Caetano do Sul, Sao Paulo [hereafter

referred to as AGMB.]

60

Brazil, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica, Annuario estatistico 1939/1940 (Rio

de Janeiro, n.d.), vol. v, p. 1,304; 'Quadro do crescimento...', 0 Automobilismo, vol.

4, no. 42 (1929), pp. 31-6. The ratio of automobiles to total population remained much

lower than in the United States, where every state except Alabama had a higher ratio

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

5 72 Richard Dowries

from 2,309 in 1921 to over 15,000 in 1927. In Bahia the US consul

reported that 'the desire to own such machines is becoming very

widespread', with prospective buyers joining clubs that promised the

chance to win an automobile, either a ' low-priced American car of a well-

known make', or a 'higher priced automobile, also American'. By 1926

over 900 kilometres of road in the state were being used by 'more than

a hundred automobiles and trucks'. 51

The vehicles' utility obviously attracted buyers, but carefully staged

actions of the auto companies themselves boosted their popularity. Ford

sent its products on a tour of the interior of Sao Paulo to provide a

'practical demonstration' even into the 'recesses of our backlands'. The

' Ford-Fordson' caravan set out in May 1926 from Sao Paulo with 16 cars,

trucks and tractors for a 1,400 kilometre, 45-day jaunt through the state's

countryside. The group appeared before a reported 100,000 persons in 25

cities, demonstrating the vehicles' capabilities by day while entertaining

evening audiences with films depicting the Ford factories and the building

of good roads. Even though one town's residents panicked at the noisy

arrival of the caravan, mistaking it for 'an invading army', Ford

considered the journey 'a complete success'. Not to be outdone, General

Motors sent out its 'Chevrolet circus', an extravaganza featuring a circus

touring the states of Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais and Sao Paulo,

transported entirely by Chevrolet vehicles. The circus always held two

shows: at 6 p.m. for individuals invited personally by the local Chevrolet

dealer, and another later for the general public. General Motors considered

the concept 'the best means of publicity developed in Brazil to this

date'.52

The companies also generated support for automobilismo and drew

potential customers by sponsoring public automobile expositions and

trips to the United States to visit elements of the automotive industry.

Exhibitions of US autos accompanied the highway conventions, but were

also organised as independent events ' creating extraordinary interest and

prospects... for sales of automobiles and agricultural machinery'. In 1926

of cars to population. Even with Alabama's ratio, Sao Paulo would have had 400,000

autos, instead of less than 39,000. See Automobilismo, vol. 1, no. t (1926), p. 26.

51

Minas Gerais, Estradas de Rodagem, p. 4 ; USC-Bahia to SS, 8 Oct. 1924, 832.513/-, R G

59, U S N A ; Bahia, Mensagem, 1926, p. 245.

52

'A caravana Ford-Fordson...', 0 Automobilismo, vol. 1, no. 3 (1926), pp. 36-7; USC-

SP to SS, 30 Sept. 1926, 832.154/73, RG 59, USNA; ' O grande circo Chevrolet',

General Motors Brasileira, vol. 5, no. 52 (1930), pp. 8-9.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

Autos over Rails: Horn US Business Supplanted the British in Brazil, 1910-28 573

the newly-arrived General Motors subsidiary conducted an exhibition to

highlight models (other than the Chevrolet) that were relatively unknown

in Brazil, and to gather an extensive list of prospective buyers. Beyond

holding the event on Rua Consolacao ' only two blocks from the Avenida

Paulista, Sao Paulo's 'Fifth Avenue', the company underwrote a massive

advertising campaign. Promotional posters decorated Sao Paulo's

streetcars, aircraft dropped leaflets from the sky, and 20,000 engraved

invitations went out to 'persons of means' in Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo,

Santos, Campinas and Belo Horizonte. On the eve of the public opening,

the company invited its dealers from throughout the country and 'a

carefully selected list of 500 of Brazil's most distinguished citizens...

government officials... and members of socially prominent and wealthy

families of Sao Paulo'. On opening day 100 cars paraded for five hours

through Sao Paulo's streets.53

Such theatre attracted a large audience, including many prospective

buyers. The company estimated that some 100,000 people shuffled in to

see 19 models of Cadillars, Oaklands, Buicks and Oldsmobiles clustered

around a raised platform where 'a gray Cadillac sport Phaeton turned

slowly, its headlights piercing through a bath of colored lights, the twin

beams ... searching out every corner of the great building'. To add to the

attraction and gather names of potential customers, the company

conducted a charity lottery with an Oldsmobile Sport Roadster as the

prize. Entrants paid i,ooo$ to guess the total kilometres the car would

travel while operating for 100 hours on a stationary treadmill. After

opening of the entries by a committee made up of the editor of the 0

Estado de Sao Paulo, the vice president of the AER, and the cityfiscal,the

ticket stubs were ' sorted and turned over to our dealers for their prospect

files'. The company also registered 71 sales during the nine-day affair and

judged that the event 'sold the General Motors organisation' and made

it 'doubtful today [that] there is a better known merchandising

organisation in Brazil'.54

On a more individual basis, the companies arranged visits to the United

States for outstanding salesmen or prominent members of society as part

of their campaign to gain acceptance in Brazil. V. E. Lucca, a former

employee of Armour do Brasil and a Cadillac and Oakland salesman for

two and a half years, was awarded a US trip in 1927 for his 'superb

63

B. F. O ' T o o l e [Latin American Div., U S B F D C ] to N . Y. District Office, U S B F D C , 10

Oct. 1925, Box 2232, R G 151, U S N A ; T S , General Motors d o Brasil, untitled

scrapbook, n.d., pt. 1, p . i, A G M B .

64

General Motors, scrapbook, p p . 4, 6; T S , 'Office Bulletin (26 N o v . 1926)', scrapbook,

A G M B . Ford retained a dominant market share, however, in 1950: 5 4 . 9 % versus

General M o t o r ' s 17.1 %. Wilkins and Hill, American Business, p. 202.

21 LAS 24

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 17 Apr 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

574 Richard Dowries

services' as General Motors' sales manager.55 The road-building firm of

Derrom-Samson arranged invitations for prominent Brazilians to visit the

United States through the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce in

Washington. In early 1926 the firm suggested that the Pan American

[Highway] Confederation invite Washington Luiz to visit the United

States. The suggestion arrived at the desk of Fred I. Kent of Banker's

Trust, a member of the Highway Education Board and of the Pan

American Highway Commission. Kent in turn passed the idea on to Pyke