Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Simpson Ami-Marie - A2 Lit Rev and Protocol

Hochgeladen von

api-370153591Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Simpson Ami-Marie - A2 Lit Rev and Protocol

Hochgeladen von

api-370153591Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

How does collaborative work impact learning in the secondary classroom?

Impact of implementation of collaborative learning strategies on the Teacher

Literature review:

Collaborative or cooperative learning is a pedagogical strategy that encourages

students to work cohesively to achieve a common goal or purpose. The individuals in the

group depend on one another to address a question, create a product or share jointly

accumulated knowledge. The role of the teacher becomes that of a facilitator, where rather

than delivering content knowledge explicitly, the students themselves are expected to work

together in small groups of two students or more to acquire knowledge or further develop

their own skills. For the purpose of this report, collaborative and cooperative learning will be

used interchangeably.

The impact on learning by the students is well documented. Marsh et al. (2014) link

cooperative learnings theoretical origins to the seminal work of John Dewey, who relegated

learning tasks to students by having them search for their own answers to social issues and

interact with their peers in a democratic way. Further, they posit that cooperative learning is

one of the dominant instructional strategies in modern pedagogical practice (Marsh et al.

2014). Certainly it is a practice that is advocated in pre-service teacher training today as a

method of Vygotsky’s constructivist learning theory whereby students shape their own higher

level learning through collaborative work with more knowledgeable peers, whether students

or teachers (Fung & Lui, 2016; Gillies & Boyle, 2010; McGregor & Mills, 2017).

The social, academic, assessment and psychological benefits of collaborative or

cooperative learning are emphasised by Laal and Ghodsi (2012), who argue that cooperative

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 1 of 13

SID 17975780

learning is more beneficial than more individualised instruction. Hattie (2012) agrees, stating

that peer groupings can help all students, no matter where they are at in their learning

continuum to move forward. Roberts (2016) builds on the benefits of proximal learning

identified by Vygotsky and Hattie but argues that grouping students of different capacities

does not inherently put the more capable student in a teaching role, but each student

encourages each other in the process of learning. Gillies and Boyle (2010) emphasise that

cooperative learning helps students to not only learn content but develop skills in group

discussions including active listening and engaging in more sophisticated discourse. Shindler

(2010) comments on the capacity for cooperative learning to accommodate diverse learning

needs over that of individualised instruction.

Given the benefits of cooperative learning, it is imperative that teachers are confident

in their capacity to facilitate an effective and positive collaborative learning environment.

However, the perceived class management challenges that are implied by the implementation

of cooperative learning strategies can lead to teacher resistance and a lack of self-efficacy

(Shindler, 2010). The implementation of collaborative learning is impeded by issues such as

but not limited to the individual teachers’ attitude and perceived self-efficacy towards

managing a collaborative learning environment, and a lack of planning and training of

students on how to collaborate effectively (Buchs et al. 2017; Duran et al., 2017; Fung & Lui,

2016; Gillies & Boyle, 2010; Le et al., 2018; Marsh et al., 2014; Saborit et al., 2016; Ruys et

al., 2014; Shindler, 2010).

The positive attitude of a teacher to the implementation of collaborative learning is

imperative to facilitating effective cooperative learning. Williams and Sheridan (2010) note

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 2 of 13

SID 17975780

that the teachers attitude also informs and guides the attitude of the students, meaning

positivity and confidence are of utmost importance. The former perceptions of teachers as

lecturers that transmit content to their passive students are dated at best, yet still used in the

majority of cases. Gillies and Boyle (2010) comment on teachers’ “propensity to talk at

students … who are rarely asked challenging reasons where they are required to think about

the issues and provide reasons for their responses” (p. 933). This teacher-centric as opposed

to learner-centred or socially constructivist approach to teaching is discussed by many

researchers (Fung & Lui, 2016; Gillies & Boyle, 2010; Saborit et al., 2016). Saborit et al.

(2016) are concerned that up to 60% of teachers consider direct instructional techniques to be

more effective and efficient methods of content delivery than collaborative learning.

Teachers are often deterred by common misconceptions around collaborative

strategies and group work such as it being a “free for all for social time” (Shindler, 2010), a

“waste of valuable lesson time” (Bevilacqua, 2000), or generally “more socialising than

working” (Gillies & Boyle, 2010). Historically, grouping students has been used as a

preventative disciplinary measure to reduce inappropriate or unwanted behaviours in the

classroom (Gillies & Boyle, 2010) or to break classes into groups of heterogenous

capabilities for differentiation purposes (Roberts, 2016; Shindler, 2010).

Buchs et al. (2017) discuss the change from instructor to facilitator as a concern for

some teachers who are not confident in their ability to hand over the authority or

responsibility to their students. Duran et al. (2018) describe a discrepancy between the

development of competencies in theoretical teacher training environments and the use of

experiential training strategies – teachers, like students, learn by doing rather than being told

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 3 of 13

SID 17975780

how. Ruys et al. (2014) elaborates on this and has found that although pre-service teacher

training includes much emphasis on the benefits of collaborative pedagogical strategies, the

implementation at the practice level is significantly less than recommended. The teachers’

successful adaption to the role of facilitator is the determining factor to effective

collaborative learning, with Shindler (2010) expounding the significance of an involved and

effective teacher leading group work environments. Fung and Lui (2016) discuss the

attributes of an effective leader being a teacher who prompts students with open-ended

questions therefore stimulating students to agree on a consensus built by collaborative

knowledge. Other attributes of an effective leader include facilitating whole class discussion

based on the findings of one group (Shindler, 2010), creating mixed-ability groups (Roberts,

2016), and designing activities that meet the needs of all learners (State of Victoria:

Department of Education and Training, 2017).

The design and implementation of effective collaborative learning activities is another

common concern. Shindler (2010) emphasises the “intentionality” (p. 231) of engaging

collaborative work. Saborit et al. (2016) lament that most collaborative tasks are

implemented in a spontaneous and unstructured way, exemplified by teachers interviewed by

Gillies and Boyle (2010) who agree that their most unsuccessful attempts at collaborative

learning suffered from a distinct lack of structure.

The structure of these learning activities need to be scaffolded by teaching the

students how to effectively collaborate. Students develop their peer relationships and self-

efficacy by sharing mutual responsibility and accountability (Buchs et al., 2017), though a

common factor for student resistance to group work is the potential of free-riders getting

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 4 of 13

SID 17975780

marks based on the efforts of others (Le et al. 2018). The careful monitoring of the

contribution of each student is therefore attributed to the teacher. A well-designed task

means that all students contribute their individual expertise in a meaningful and equal way

(State of Victoria: Department of Education and Training, 2017), with an emphasis on

positive interdependence (Gillies & Boyle, 2010). Interviews with secondary students by Le

et al. (2018) find that the majority of students are not given instruction on ways of

collaborating effectively such as “accepting opposing viewpoints, giving elaborate

explanations, providing and receiving help and negotiating” (p. 110). These skills are key

elements to successful group learning (Gillies & Boyle, 2010), therefore facilitating the

development of these skills needs to be implemented into the structure of any collaborative

task.

These implications for the implementation of collaborative learning all add to the

current workload of a modern teacher in Australian classrooms, who is expected to deliver

quality content to a variety of diverse learners in engaging and productive ways. Given the

impact that classroom management alone has on teacher attrition rates and emotional burnout

(Tsouloupas, Carson, Matthews, Grawitch, & Barber, 2010), it does not seem at all surprising

that the perceived extra workload could intimidate teachers who perceive themselves to lack

the skills required to integrate collaborative learning strategies in their classrooms.

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 5 of 13

SID 17975780

Data Protocol Justification:

With these theories in mind, an investigation into the impacts of the implementation

of collaborative strategies on Australian secondary school teachers will be surveyed. The

purpose of the survey will be to ascertain how the facilitation of group work effects the day-

to-day life of a teacher, and if these best practice models discussed are being actively

implemented in classrooms. Of particular interest is the training of teachers in cooperative

learning strategies, and how this may differ based on tenure.

The survey is based on a Google Form (see below) and will be emailed to a selection

of teachers within the researcher’s practicum experience context in Term 2, 2018, as well as

to selected peers within the pre-service training context. The email will include the data

collection Consent Form as attached below in keeping with ethical protocol. The responses

will be collated anonymously, and any identifying information will be de-identified prior to

finalised reporting of data analysis and representation in the final part of this assessment.

The survey consists of a mixture of close-ended and open-ended questions. The

close-ended questions aim to serve the purpose of identifying which respondents have tenure,

have been exposed to training in collaborative learning strategies and who feels as though

these strategies are purposeful in their classroom. The open-ended questions will deliver

further information about what strategies teachers are or are not using, and their justifications.

To best learn about the impact on the implementation of collaborative work on

teachers, the aim is to purposively recruit teachers or pre-service teachers with some

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 6 of 13

SID 17975780

practicum experience. It would be beneficial to recruit contributions from teachers with

tenure to compare and contrast their perceptions of collaborative learning with that of pre-

service or graduate teachers, given the current pedagogical focus on constructivist teaching in

pre-service training modules. The open nature of some of the questions will assist in

identifying what, if any, are the more popular collaborative learning strategies in these

classrooms.

Survey is a beneficial model to use for this purpose, as the aim is to see if there is a

change of attitude over time (Kemmis, McTaggart, & Nixon, 2014). The survey is made up

of closed questions: Yes or No answers, and open-ended questions to see if there is a

similarity between reasoning or justifications. The data can then be measured and coded by

downloading the results from the Google Forms to a spreadsheet. The spreadsheet will clearly

indicate teachers’ answers to the close ended questions, with the open ended results being

searched and carefully coded to identify any common or recurring categories or themes in the

data (Kervin, Vialle, Howard, Herrington, & Okely, 2016). Themes that could be anticipated

from this data could be the use of collaborative learning strategies such as group work,

collaborative writing, presentations, think-pair-share and others. Another outcome could

identify whether Australian teachers perceive the implementation of collaborative work to be

too time intensive or not worthwhile.

Survey has its pitfalls, given the close-ended questions and lack of capacity to further

question the respondent to expand on their answers. However, the capacity for a longer

response for some questions enables the researcher to get a clear answer in the respondents’

own vernacular, without the bias that may be applied when taking notes for instance during

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 7 of 13

SID 17975780

interviews or observation. Another benefit of email survey is the potential to gather more

respondents in the same time frame.

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 8 of 13

SID 17975780

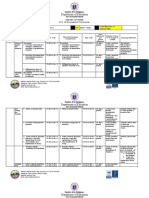

Survey (Google Forms):

Double click to open PDF

Impact of the implementation of collaborative learning strategies in the secondary classroom - Google Forms.pdf

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 9 of 13

SID 17975780

Consent Form:

Dear Potential Participant:

I am working on a project titled The Impact of Collaborative Learning Strategies on the Secondary

Classroom for the class, ‘Researching Teaching and Learning 2,’ at Western Sydney University. As part of

the project, I am collecting information to help inform the design of a teacher research proposal.

My topic focuses on the impact of the implementation of collaborative learning strategies on the teacher.

I intend to collect data from teachers to better understand their opinions on how collaborative learning

impacts their day-to-day classroom activities.

By participating in this survey, I acknowledge that:

I have read the project information and have been given the opportunity to discuss the

information and my involvement in the project with the researcher/s.

The procedures required for the project and the time involved have been explained to me, and

any questions I have about the project have been answered to my satisfaction.

I consent to completing the survey.

I understand that my involvement is confidential and that the information gained during this

data collection experience will only be reported within the confines of the ‘Researching Teaching

and Learning 2’ unit, and that all personal details will be de-identified from the data.

I understand that I can withdraw from the project at any time, without affecting my relationship

with the researcher/s, now or in the future.

By signing below, I acknowledge that I am 18 years of age or older, or I am a full-time university student

who is older than 17 years.

Signed: __________________________________

Name: __________________________________

Date: __________________________________

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 10 of 13

SID 17975780

References

Bevilacqua, M. (2000). Collaborative Learning in the Secondary English Classroom. The Clearing

House, 73(3), 132-133.

Buchs, C., Filippou, D., Pulfrey, C., & Volpe, Y. (2017). Challenges for cooperative learning

implementation: reports from elementary school teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching,

43(3), 296-306.

De Nobile, J., Lyons, G., & Arthur-Kelly, M. (2017). Positive Learning Environments: Creating and

Maintaining Productive Classrooms. South Melbourne: Cengage Learning.

Duran, D., Corcelles, M., & Flores, M. (2017). Enhancing Expectations of Cooperative Learning Use

through Initial Teacher Training. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 6(3), 278-

300.

Fung, D., & Lui, W. (2016). Individual to collaborative: guided group work and the role of teachers in

junior secondary science classrooms. International Journal of Science Education, 38(7),

1057-1076.

Gall, M., Gall, J., & Borg, W. (2015). Applying educational research: How to read, do and use

research to solve problems of practice. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson.

Gillies, R., & Boyle, M. (2010). Teachers' reflections on cooperative learning: Issues of

implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 933-940.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximising Impact on Learning. New York:

Routledge.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The Action Research Planner. Singapore: Springer

Science+Business Media.

Kervin, L., Vialle, W., Howard, S., Herrington, J., & Okely, T. (2016). Research for Educators. South

Melbourne: Cengage Learning Australia Pty Ltd.

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 11 of 13

SID 17975780

Laal, M., & Ghodsi, S. (2012). Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 31, 486-490.

Le, H., Janssen, J., & Wubbels, T. (2018). Collaborative learning practices: teacher and student

perceived obstacles to effective student collaboration. Cambridge Journal of Education,

48(1), 103-122.

Marsh, C. J., Clarke, M., & Pittaway, S. (2014). Marsh's Becoming A Teacher. Frenchs Forest,

Australia: Pearson Australia.

McGregor, G., & Mills, M. (2017). 15: The Virtual Schoolbag and Pedagogies of Engagement. In B.

Gobby, & R. Walker, Powers of Curriculum: Sociological Perspectives on Education (pp.

373-392). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, J. (2016). The 'More Capable Peer': Approaches to Collaborative Learning in a Mixed-

Ability Classroom. Changing English, 23(1), 42-51.

Ruys, I., Van Keer, H., & Aelterman, A. (2014). Student and novice teachers' stories about

collaborative learning implementation. Teachers and Teaching, 20(6), 688-703.

Saborit, J., Fernandez-Rio, J., Estrada, J., Mendez-Gimenez, A., & Alonso, D. (2016). Teachers'

attitude and perception towards cooperative learning implementation: Influence of continuing

training. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 438-445.

Shindler, J. (2010). Tranformative Classroom Management: Positive Strategies to Engage all

Students and Promote a Psychology of Success. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

State of Victoria: Department of Education and Training. (2017). High Impact Teaching Strategies.

Retrieved from Teaching Practice:

http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/support/highimpactteachstrat.pd

Tsouloupas, C., Carson, R., Matthews, R., Grawitch, M., & Barber, L. (2010). Exploring the

association between teachers' perceived student misbehaviour and emotional exhaustion: the

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 12 of 13

SID 17975780

importance of teacher efficacy beliefs and emotion regulation. International Psychology,

30(2), 173-189.

Williams, P., & Sheridan, S. (2010). Conditions for collaborative learning and constructive

competition in school. Educational Research, 52(4), 335-350.

SIMPSON, Ami-Marie 102097 – A2 Lit Review & Protocol Page 13 of 13

SID 17975780

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Classroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsVon EverandClassroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Successfully Implementing Problem-Based Learning in Classrooms: Research in K-12 and Teacher EducationVon EverandSuccessfully Implementing Problem-Based Learning in Classrooms: Research in K-12 and Teacher EducationThomas BrushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Students' Willingness To Practice Collaborative Learning: Teaching EducationDokument18 SeitenStudents' Willingness To Practice Collaborative Learning: Teaching EducationJuan Rocha DurandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edld - 5315Dokument12 SeitenEdld - 5315LaToya WashingtonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Nani Tehh Panabangi Final Mao Nani e PrintDokument35 SeitenFinal Nani Tehh Panabangi Final Mao Nani e Printjuliana santosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effectiveness of Collaborative LearningDokument16 SeitenEffectiveness of Collaborative LearningGreg MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 CompleteDokument9 SeitenChapter 2 CompletedocosinvonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project 690 Action Research ProposalDokument16 SeitenProject 690 Action Research Proposalapi-610591673Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2Dokument12 SeitenChapter 2Mark Rhyan AguantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 in PR1Dokument3 SeitenChapter 2 in PR1Norhanifa CosignNoch keine Bewertungen

- ResearchDokument19 SeitenResearchJustine WicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approches 2019Dokument14 SeitenApproches 2019lizete.capelas8130Noch keine Bewertungen

- Full Thesis RevisionDokument19 SeitenFull Thesis RevisionChristian Marc Colobong PalmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MathDokument27 SeitenMathDayondon, AprilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discussion 3Dokument4 SeitenDiscussion 3Nordia Black-BrownNoch keine Bewertungen

- The 4s Conceptual FrameworkDokument1 SeiteThe 4s Conceptual Frameworkapi-361327264Noch keine Bewertungen

- ColletGreiner2020RevisioningGrammarInstruction Pre PrintDokument27 SeitenColletGreiner2020RevisioningGrammarInstruction Pre PrintEVELYN GUISELLE CASTILLO ZHAMUNGUINoch keine Bewertungen

- Efficacy of Cooperative Learning Method To Increase Student Engagement and Academic Achievement 2Dokument7 SeitenEfficacy of Cooperative Learning Method To Increase Student Engagement and Academic Achievement 2Aila Judea MoradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 2 EdresDokument18 SeitenChap 2 EdresHALICIA LLANEL OCAMPONoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0883035522000052 MainDokument15 Seiten1 s2.0 S0883035522000052 Mainsher ahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- RRL 2019Dokument28 SeitenRRL 2019Analea C. AñonuevoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action ResearchDokument19 SeitenAction Researchmulatu mokononNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Suggested Technique For Cooperative Learning Implication in EFL ClassroomDokument15 SeitenA Suggested Technique For Cooperative Learning Implication in EFL ClassroomWagdi Bin-HadyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Group Study On Academic Performance Among Psychology StudentsDokument3 SeitenThe Impact of Group Study On Academic Performance Among Psychology StudentsAvery CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cooperation-Based Instructional DesignDokument14 SeitenCooperation-Based Instructional DesignSokhoeurn MourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cooperative and Collaborative Learning: Getting The Best of Both WordsDokument15 SeitenCooperative and Collaborative Learning: Getting The Best of Both Wordsjorge CoronadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Co-Creating Rubrics: Students Perspective On Their Process and The Product Designed in Technology-Enhanced Learning EnvironmentsDokument14 SeitenCo-Creating Rubrics: Students Perspective On Their Process and The Product Designed in Technology-Enhanced Learning EnvironmentsJennifer Saray Santana MartelNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Cooperative Learning Method On LearnDokument6 SeitenThe Impact of Cooperative Learning Method On LearnYolandinova SitorusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ej1151080 PDFDokument15 SeitenEj1151080 PDFDonna France Magistrado CalibaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Collaborative Learning in ClassroomDokument32 SeitenCollaborative Learning in ClassroomCristián EcheverríaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 FinalDokument12 SeitenChapter 1 FinalCherry Ann JarabeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1Dokument23 SeitenChapter 1Buena flor AñabiezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching English As A Foreign LanguageDokument16 SeitenTeaching English As A Foreign LanguageFebiana WardaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cooperative Learning StrategiesDokument75 SeitenCooperative Learning StrategiesMitzifaye Taotao100% (2)

- Jurnal Blended Learning 5 International - 2021Dokument38 SeitenJurnal Blended Learning 5 International - 2021zanisa nadiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7526-Article Text-29125-1-10-20150903Dokument5 Seiten7526-Article Text-29125-1-10-20150903Hiền Hoàng PhươngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conceptpaper ZablanDokument7 SeitenConceptpaper ZablanNyzell Mary S. ZablanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Peer Tutoring Teaching StrategDokument46 SeitenEffect of Peer Tutoring Teaching StrategNelly Jane FainaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action Research PlanDokument2 SeitenAction Research PlanRhea Jane AnselmoNoch keine Bewertungen

- rtl2 Assessment 2Dokument10 Seitenrtl2 Assessment 2api-435791379Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research Teaching and Learning 2 - Assessment 2 18417223Dokument9 SeitenResearch Teaching and Learning 2 - Assessment 2 18417223api-429880911Noch keine Bewertungen

- Traditional and Flipped Classroom Approaches Delivered by Two Different Teachers: The Student PerspectiveDokument21 SeitenTraditional and Flipped Classroom Approaches Delivered by Two Different Teachers: The Student PerspectiveJamaica Leslie NovenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- rtl2 - Assessment 1Dokument9 Seitenrtl2 - Assessment 1api-320830519Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yessy STPDokument7 SeitenYessy STPAryo ArifuddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effectiveness of InclusionDokument5 SeitenEffectiveness of Inclusionmb2569Noch keine Bewertungen

- 3I'SDokument7 Seiten3I'SShenmyer Pascual CamposNoch keine Bewertungen

- Additional RRLDokument11 SeitenAdditional RRLmae ann CadenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task-Based Instruction As A Tool in Improving The Writing Skills of Grade 11 Students in Selected Senior High Schools in San Juan BatangasDokument7 SeitenTask-Based Instruction As A Tool in Improving The Writing Skills of Grade 11 Students in Selected Senior High Schools in San Juan BatangasJennelyn Inocencio SulitNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Peer Learning Within A Group of InteDokument22 SeitenThe Impact of Peer Learning Within A Group of InteSalah MamouniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Inclusive Practices of Classroom Teachers: A Scoping Review and Thematic AnalysisDokument29 SeitenThe Inclusive Practices of Classroom Teachers: A Scoping Review and Thematic AnalysisAllen JordiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ContextDokument3 SeitenContextJOANA MARIE MATANoch keine Bewertungen

- CooperativeLearningandStudentSelf EsteemDokument39 SeitenCooperativeLearningandStudentSelf EsteemLiow Zhi XianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Chapter-GLENDA V. PAPELLERODokument8 SeitenBook Chapter-GLENDA V. PAPELLEROGlenda PapelleroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peer Tutoring On Studetns AchievementDokument80 SeitenPeer Tutoring On Studetns AchievementMux ITLinksNoch keine Bewertungen

- G3 IntroductionDraftDokument4 SeitenG3 IntroductionDraftDK 15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hares Sped854 m1 PhilosophyDokument6 SeitenHares Sped854 m1 Philosophyapi-610918129Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teachers' Perceptions of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and The Impact On Leadership Preparation: Lessons For Future Reform EffortsDokument20 SeitenTeachers' Perceptions of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and The Impact On Leadership Preparation: Lessons For Future Reform EffortsKhemHuangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bovill 2016 Addressing Potential Challenges inDokument14 SeitenBovill 2016 Addressing Potential Challenges inFollet TortugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written Assignment Unit 1Dokument7 SeitenWritten Assignment Unit 1daya kaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher's Perspective of SAPDokument8 SeitenTeacher's Perspective of SAPHafiz RabbiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simpson Ami-Marie - Teaching CVDokument2 SeitenSimpson Ami-Marie - Teaching CVapi-370153591Noch keine Bewertungen

- Simpson Ami-Marie - A1Dokument11 SeitenSimpson Ami-Marie - A1api-370153591Noch keine Bewertungen

- Simpson Ami-Marie A1 1Dokument41 SeitenSimpson Ami-Marie A1 1api-370153591Noch keine Bewertungen

- Changes To Class During IR: Invention QuizDokument3 SeitenChanges To Class During IR: Invention Quizapi-370153591Noch keine Bewertungen

- IntelligenceDokument39 SeitenIntelligenceAlishba ZubairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Background of The Study FinalDokument8 SeitenBackground of The Study FinalBIEN RUVIC MANERONoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget of Work Practical Research 2Dokument3 SeitenBudget of Work Practical Research 2Ester RodulfaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Math 7 - Week 5.1Dokument2 SeitenMath 7 - Week 5.1waywayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDT SaDokument2 SeitenPDT Saapi-340625860Noch keine Bewertungen

- Scid2 BPDDokument4 SeitenScid2 BPDRamonaStereaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Gathering ProcedureDokument3 SeitenData Gathering ProcedureMichelle MahingqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eclectic Counseling 1Dokument4 SeitenEclectic Counseling 1NelsonMoseM80% (5)

- Portfolio Comprehension MakingconnectionsDokument2 SeitenPortfolio Comprehension Makingconnectionsapi-289049819Noch keine Bewertungen

- Maslach Leiter Burnout Stress Concepts Cognition Emotionand BehaviorDokument5 SeitenMaslach Leiter Burnout Stress Concepts Cognition Emotionand BehaviorMOHD SHAHRIZAL CHE JAMEL100% (1)

- Technology Integrated LessonDokument5 SeitenTechnology Integrated Lessonapi-198204198Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3 in Persuasive Writing 2Dokument2 SeitenLesson 3 in Persuasive Writing 2api-459412225Noch keine Bewertungen

- Divergent ThinkingDokument16 SeitenDivergent ThinkingGrantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ms Moving PoetryDokument2 SeitenMs Moving Poetryapi-29777708Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cuestionario SPQ de Rasgos de Personalidad Esquizotípica - Validez y ConfiabilidadDokument6 SeitenCuestionario SPQ de Rasgos de Personalidad Esquizotípica - Validez y ConfiabilidadGuillermo A ManriqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissociative Identity Disoder1Dokument20 SeitenDissociative Identity Disoder1kmccullars100% (1)

- AndersonDokument14 SeitenAndersonsskishore89Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2020 - Intensive Intervention For Adolescents With Autism - Mazza Et AlDokument10 Seiten2020 - Intensive Intervention For Adolescents With Autism - Mazza Et AlJesus RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource DevelopmentDokument2 SeitenHuman Resource DevelopmentteshomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3rd Quarter COT - Observation January 15,2020Dokument3 Seiten3rd Quarter COT - Observation January 15,2020Josephine Rivera100% (1)

- Leadership and Management Development AssignmentDokument18 SeitenLeadership and Management Development AssignmentKarthik100% (2)

- Item Response Theory - Psychometric TestsDokument3 SeitenItem Response Theory - Psychometric TestsSyeda Naz Ish NaqviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan Clothes Bun A 5aDokument5 SeitenLesson Plan Clothes Bun A 5aPaul HasasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pdev 111 2ND Grading Exam (Amaoedsources - Blogspot.com)Dokument122 SeitenPdev 111 2ND Grading Exam (Amaoedsources - Blogspot.com)Keith Shimezu100% (2)

- Emotional Intelligence Self-AssessmentDokument10 SeitenEmotional Intelligence Self-AssessmentArjohn PaalisboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course Description General InformationDokument3 SeitenCourse Description General InformationJack BlackNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABM - AOM11 IIc e 30Dokument3 SeitenABM - AOM11 IIc e 30Jarven SaguinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accuracy Vs FluencyDokument4 SeitenAccuracy Vs Fluency陳佐安100% (1)

- SAMPLE of Practicum JournalDokument3 SeitenSAMPLE of Practicum Journallacus313Noch keine Bewertungen

- Placement and InductionDokument13 SeitenPlacement and InductionaditiNoch keine Bewertungen