Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Tempest - Parallelism in Characters and Situations

Hochgeladen von

noelya_16Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Tempest - Parallelism in Characters and Situations

Hochgeladen von

noelya_16Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

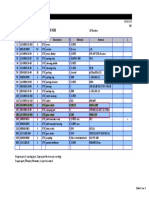

"The Tempest": Parallelism in Characters and Situations

Author(s): Allan H. Gilbert

Source: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Jan., 1915), pp. 63-74

Published by: University of Illinois Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27700639 .

Accessed: 24/05/2014 04:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal

of English and Germanic Philology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Tempest: Parallelism in Characters 63

THE TEMPEST: PARALLELISM IN CHARACTERS AND

SITUATIONS

Conspicuous in The Tempest of Shakespeare is the use of similar

and yet contrasted situations and characters. The suggestion of

likeness in difference is especially noticeable in the case of the two

servants of Prospero, Caliban and Ariel, one an

strange airy sprite,

the other an

earthy monster. Ariel is a being purely supernatural,

gifted with the abilities proper to spirits of the air, who, says

Reginald Scot, "can give the gift of invisibility, and the fore

knowledge of the change of weather; they can teach the exorcist

how to excite storms and tempests, and how to calm them again;

can news in an hour's space of the success of any battle,

they bring

siege, or navy, how far off soever" {Discovery of Witchcraft, 15. 6,

App. 1). Caliban, on the contrary, though partly supernatural,

possesses no powers than those of ordinary mortals, and can

greater

render the services of a menial of savage race. of

only Though

superhuman descent

through father, the devil, from that

his

parentage he derives only deformity. Like Lorel the Rude in

Jonson's Sad Shepherd, he does not partake of the diabolical craft of

the witch, his mother; quite the other way, he is sometimes but a

"puppy headed monster." Both the light spirit and the brutish

monster are equally desirous of freedom: Caliban embraces his

opportunity to throw off the yoke of Prospero, and there is discord

between Prospero and his quaint minister only when Ariel too

much insists upon his master's promise of liberty. Even though

Caliban, having a human shape, and being half of human parentage,

may be supposed to have a soul, and Ariel is, like Undine, without

one, the moral superiority is Ariel's. Were he but human he

would be moved by the sorrow of Prospero 's victims; even though

"

but air he has "a touch, a feeling of their afflictions. The sugges

tion that Ariel can feel pity leads to his comparison with Miranda,

the only woman appearing in the play. Even though she scarcely

understands the she sees wrecked before her, she says:

ship

O! I have suffer'd

With those I saw suffer:.

O ! the cry did knock

Against my very heart (1. 2. 5-9).

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

64 Gilbert

Many of the characters of the play appear two by two. Prospero

and Alonzo, the two rulers who have been enemies, are thrown

together by the union of that charming pair, their children; for the

courteous Ferdinand and the simple Miranda are foils for one

another. There are two Antonio and two

conspirators, Sebastian;

clowns, Stephano and Trinculo; two lords, Adrian and Francisco;

even two principal goddesses, Juno and Ceres. If Sycorax can be

counted, there are two magicians, for the witch was

one so strong

That could control the moon, make flows and ebbs,

And deal in her command without her power (5. 269).

Prospero uses his power for good, bringing about repentance and

restoration, but Sycorax has practised

mischiefs manifold and sorceries terrible

To enter human hearing (1. 2. 264-5);

yet the two work in similar ways. Prospero threatens to inflict on

Ariel a punishment like that he suffered from Sycorax. She, he

says to Ariel,

did confine thee,

By help of her more potent ministers,

And in her most unmitigable rage,

Into a cloven pine; within which rift

Imprison'd, thou didst painfully remain

A dozen years; ......

where thou didst vent thy groans

As fast as mill-wheels strike (1. 2. 274-81);

and for himself he declares :

I will rend an oak

And peg thee in his knotty entrails till

Thou hast howl'd away twelve winters (1.2. 294-6).

Both magicians have been banished to the island, and both because

of their art; Prospero gave himself so much to the study of magic

that he lost hold of the reins of his dukedom : Sycorax was criminal

in her practise of magic. Prospero brought his infant daughter to

the island : Sycorax gave birth to Caliban soon after her arrival, so

that he is a native of the island.

Thetwo conspiracies, that of Stephano, Trinculo, and Caliban,

against Prospero, and that of Antonio and Sebastian against Alonzo,

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Tempest: Parallelism in Characters 65

emphasize one another by contrast, even in details. Stephano

expects to make himself king of the island, and under his rule

Caliban anticipates freedom, just as Sebastian by the murder of his

brother will become king of Naples and will grant to Antonio, for

his aid, freedom from tribute. The sufferings of the two sets of

conspirators, when their are revealed, are suited to their

plots

characters: Stephano and his companions suffer bodily torments,

but the noble conspirators are afflicted only in conscience. Yet

both are punished through the same instrumentality, that of

Prospero and Ariel, and the same word {pinch1) is used to describe

the afflictions of both. Caliban endeavors to induce his fellow

conspirators to leave the spoiling of Prospero's goods and proceed

with their attack upon the owner, by saying:

Let's along,

And do the murder first: if he awake,

From toe to crown he'll fill our skin with pinches;

Make us strange stuff (4. 231-4).

He is right, for Prospero commands Ariel, when he punishes them, to

shorten up their sinews

With aged cramps, and more pinch-spotted make them

Than pard, or cat o' mountain (4. 260-62);

and in his afflictions Caliban cries out:

I shall be pinched to death (5. 276).

In rebuking the noble villains Prospero uses pinch to describe the

torments of conscience:

Thou'rt pinch'd for't now, Sebastian.

Sebastian,?

Whose inward pinches therefore are most strong (5. 74-7).

Sebastian and Antonio apply to Caliban the very words before used

by Stephano and Trinculo. When Trinculo first sees Caliban he

exclaims: "What have we here? a man or a fish? Dead or alive?

A fish: he smells like a fish; a very ancient and fish-like smell; a

kind of not of the newest Poor-John. A strange fish! Were I in

1

Pinch is elsewhere used by Shakespeare to describe mental discomfort

(e.g., I HenryIV, 1. 3. 229), but nowhere so strikingly as in The Tempest, where

it appears several times, referring now to mental, now to physical pain.

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

66 Gilbert

England now,.and had but this fish painted, not a

holiday fool there but would give a piece of silver" (2. 2. 24-9);

and in like manner when Caliban first appears to the nobles, Sebas

tian cries:

What things are these, my lord Antonio?

Will money buy them?

and Antonio answers:

Very like; one of them

Is a plain fish, and, no doubt, marketable (5. 263-6).

When Gonzalo begins to speculate on his ideal commonwealth he

remarks :

Had I plantation of this isle, my lord,?.

And were the king on't, what would I do?

to be interrupted by Sebastian:

'Scape being drunk for want of wine (2. 2. 144-7).

King Stephano, during his brief rule of the island, is far from escap

ing drunkenness through lack of wine; when at the conclusion of the

play he comes forward drunk, Sebastian, with his same thought of

the barrenness of the isle, says:

He is drunk now: where had he wine (5. 278)?

When told of Miranda, Stephano, bringing himself into contrast

with other characters than the conspirators, decides: "His daughter

and I will be king and queen?save our graces" (3. 2. 111-2), just as

Ferdinand, when he first sees Miranda, plans to make her queen of

Naples, and Alonzo says of her and Ferdinand :

O heavens ! that they were living both in Naples,

The king and queen there (5. 147-8) !

In neither case is the chief plotter in the conspiracy to be the

chief gainer. Caliban is to secure nothing but the gratification of

his hatred for Prospero, and a freedom that is but a more abject

servitude: Antonio's share in the conspiracy into which he leads

Sebastian, and in which the latter is to gain a kingdom, is but the

remission of the tribute he pays to Naples. Caliban defers to what

he thinks the better intellect of Stephano, and Antonio to Sebas

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Tempest: Parallelism in Characters 67

tian's right by birth. Both plans are to be brought to pass by a

single stroke. Sebastian exhorts Antonio:

Draw thy sword: one stroke

Shall free thee from the tribute which thou pay'st (2. 1. 293-4);

and in an antithetical speech Caliban, the chief plotter, promises

subjection to King Stephano:

This is the mouth o' the cell : no noise, and enter.

Do that good mischief, which may make this island

Thine own forever, and I, thy Caliban,

For aye thy foot-licker (4. 216-9).

Both groups of conspirators rely on striking while the objects of

their attack are asleep, and have not courage to make the attempt

at any other time. When foiled in the first attempt at murder by

the waking of the king, Antonio exhorts Sebastian to carry out the

plan that night, when their victims,

oppress'd with travel,.

Will not, nor cannot, use such vigilance

As when they are fresh (3. 3. 15-7).

Caliban again and again speaks of the necessity of attacking

Prospero when he is asleep :

I'll yield him thee asleep,

Where thou may'st knock a nail into his head (3. 2. 65-6) ;

Prithee, my king, be quiet (4. 215);

and there are other references to the same necessity. Prospero's

opinion of the noble conspirators,

some of you there present

Are worse than devils (3. 3. 35-6),

is echoed in his remark on the "born devil" Caliban, when he says

to those very :

conspirators

And this demi-devil?

For he's a bastard one?had plotted with them

To take my life (5. 272-4).

Caliban's hatred for Prospero led him, in his hope for revenge, to

serve Stephano even more abjectly than he had served Prospero,

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68 Gilbert

and to offer him the same services, such as pointing out the fresh

springs and bearing wood (2. 2. 160): Antonio, duke in all but

name, was willing to submit to the king of Naples,

and bend

The dukedom, yet unbow'd,?alas, poor Milan!?

To most ignoble stooping (1.2. 114-6),

in order to dispossess his brother. Both Caliban and Antonio have

manifested ingratitude. Caliban had been no slave during the

early part of Prospero's residence in the island; Prospero had

treated him kindly, taught him, and lodged him in his own cell, but

the devilish nature of Caliban would take no print of kindness: he

repaid his benefactor by an attempt to violate the honor of his

child. The depraved nature of Antonio responded to kindness in

the same fashion; Prospero says of him:

I.in my false brother

Awak'd an evil nature; and my trust

Like a good parent, did beget of him

A falsehood in its contrary as great

As my trust was; which had indeed no limit,

A confidence sans bound (1. 2. 92-7).

Like Caliban he used his opportunities to practise treachery against

his benefactor.

At the beginning of Act II, Scene 2, Caliban enters with a burden

of wood: two hundred lines later, at the beginning of the next

scene, the first of Act III, Ferdinand enters bearing a log. If this

similarity is striking on the modern stage, with its change of

scenery, and its long pause between the acts, it must have been

much more so on the Elizabethan stage. Miranda's words to

Ferdinand,

Such baseness

Had never like executor (3. 1. 12-3),

receive new when one remembers that has laid

meaning Prospero

on Ferdinand the chief task of Caliban, though with the difference

that Ferdinand

must remove

Some thousands of these logs and pile them up (3. 1. 9-10),

while Caliban merely fetches in fuel. Even though Miranda does

not love to look on Caliban and has no ambition to see a goodlier

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Tempest: Parallelism in Characters 69

man than Ferdinand, the two are related in more than occupation

alone. Prospero endeavors to restrain Miranda's admiration for

Ferdinand's beauty with the words:

Thou think'st there is no more such shapes as he,

Having seen but him and Caliban: foolish wench!

To the most of men this is a Caliban

And they to him are angels (1.2. 475-8).

Miranda herself uses Caliban as a standard:

This

Is the third man that e'er I saw; the first

That e'er I sigh'd for (1. 2. 442-3).

Later she refrains from bringing Caliban into the comparison :

Nor have I seen

More that I may call men than you, good friend,

And my dear father (3. 1. 50-2).

The two are used to show the connection of beauty and goodness,

evil and ugliness. Miranda says of Ferdinand:

There's nothing ill can dwell in such a temple:

If the ?1 spirit have so fair a house,

Good things will strive to dwell with't (1. 2, 454-6).

And Prospero says of Caliban:

He is as disproportion'd in his manners

As in his shape (5. 290-1);

As with age his body uglier grows,

So his mind cankers (4. 191-2).

With the last may be compared also Prospero's description of

Ferdinand:

And, but he's something stain'd

With grief?that beauty's canker?thou might'st call him

A goodly person (1. 2. 411-3).

Ferdinand hears mysterious music, and comments on it as follows:

Where should this music be? i' th' air, or th' earth?

It sounds no more;?and sure, it waits upon

ome god o' th' island. Sitting on a bank,

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70 Gilbert

Weeping again the king my father's wrack,

This music crept by me upon the waters,

Allaying both their fury, and my passion,

With its sweet air (1. 2. 385-91).

Caliban also utters a remarkable speech on the mysterious noises of

the island:

The isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight, and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand

twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears; and sometime voices,

That, if I then had wak'd after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again (3. 2. 141-6).

Caliban asserts himself against Prospero as the native possessor of

the island:

This island's mine, by Sycorax my mother,

Which thou tak'st from me (1. 2. 331-2).

Prospero accuses Ferdinand of attempting to win the island :

Thou.hast put thyself

Upon this island as a spy, to win it

From me, the lord on't (1. 2. 451-3).

The brutal Caliban has endeavored to violate the chastity of Miran

da; Prospero feels it needful to exhort even the chivalrous Ferdinand

to respect his lady's honor, in the words:

If thou dost break her virgin knot before

All sanctimonious ceremonies may

With full and holy rite be minister'd,

No sweet aspersion shall the heavens let fall.

therefore take heed,

As Hymen's lamps shall light you.

Look, thou be true; do not give dalliance

Too much the rein: the strongest oaths are straw

To the fire i' the blood : be more abstemious,

Or else good night your vow (4. 15-54)!

Both Ferdinand and his father think Miranda a goddess, and she,

in her innocence, on seeing Ferdinand for the first time exclaims:

What is't? a spirit?

Lord, how it looks about! Believe me, sir,

It carries a brave form:?but 'tis a spirit. ....

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Tempest: Parallelism in Characters 71

I might call him

A thing divine; for nothing natural

I ever saw so noble (1. 2. 406-15).

In like manner Caliban, after recovering from the fright given him

by Stephano and Trinculo, says of them:

These be fine things an if they be not sprites.

That's a brave god and bears celestial liquor (2. 2. 114-5).

When Miranda looks on the assembled company she bursts out:

O wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is ! O brave new world,

That has such people in't (5. 181-4).

Similarly Caliban exclaims:

O Setebos! these be brave spirits, indeed (5. 261).

But why should there not be likeness between Miranda and

Caliban? Both have been brought up on the island without know

ledge of the ways of the world, and both have been pupils of Pros

pero; but while the devilish nature of Caliban, appealed to only by

stripes, has taken no impress of virtue, Prospero can say to his

daughter:

Here

Have I, thy schoolmaster, made thee more profit

Than other princes can, that have more time

For vainer hours and tutors not so careful (1. 2. 171-4).

When Davenant and Dryden "added to the design of Shakespeare"

to produce their adaptation, The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island,

one of the additions of which Dryden speaks with most satisfaction

was "that of a man who had never seen a woman"; the part was

already well nigh filled, for Caliban had seen only his mother and

Miranda. Just as Prospero can make himself intelligible toMiran

da only by comparing Ferdinand to Caliban, in his words:

To the most of men this is a Caliban

And they to him are angels (1. 2. 477-8);

so the experience of Caliban has given him but one comparison

with which to tell of the beauty of Miranda:

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72 Gilbert

I never saw a woman,

But only Sycorax my dam and she;

But she as far surpasseth Sycorax

As great'st does least (3. 2. 105-8).

Shakespeare has added to the interest of The Tempest by his use

of contrast and similarity, making the plot more vivid, and the

comic scenes more one makes the other more

striking; conspiracy

effective, and Caliban ismore of a fish when called so by nobles as

well as servants. But the similarities are even more

by important

in bringing out some of the truths embodied in the drama. Per

haps the greatest lesson of the play is that men are good or bad by

what iswithin, not by that which iswithout: virtue or vice depends

on a man's own rather than on his environment: human

spirit

nature is essentially the same in every walk of life and in every

state of society : the learned and the ignorant, the civilized and the

savage, turn to good or evil as their natures incline them.

The witch Sycorax was banished for terrible deeds of sorcery;

she had used her magic power to devise such abhorred commands

that Ariel could not perform them. Yet even though she sold

herself to the devil, and bore a son whose father was the devil, she

did one good act that saved her life. The magic power of Prospero

is far different from that of Sycorax, not in scope, but in the spirit

behind it: if the magic of Sycorax drove her from men, that of

Prospero restores him to society by overthrowing the works of evil,

and causing repentance in the hearts of those who have injured

him; his supernatural power joined to his nobility of character

makes him the righteous providence of the play, bringing all to a

happy end. The two conspiracies reveal selfish lust for power in

the minds of prince and servant: Stephano is as willing to do evil

to make himself king as is Sebastian. Caliban, the savage native,

is as full of hatred for Prospero as Antonio himself had been,

for ingratitude dwells in the woods of the island as well as in the

halls of princes. It is a significant thing that he who might appear

as the innocent child of nature is made the son of the prince of

darkness himself. Difference in externals makes more evident the

similarity in character of the various conspirators. Stephano is

turned aside by a few rich garments; Sebastian grants Antonio the

tribute of a dukedom: Antonio has been moved by ambition

ungratefully to seize the dukedom of Prospero; Caliban, though

untainted by avarice, has with equal ingratitude yielded to lust

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Tempest: Parallelism in Characters 73

and endeavored to dishonor Miranda: both noble and savage are

willing murderers. There can hardly be a greater contrast than

between the courtly Ferdinand and the brutal Caliban. The for

mer is the ideal of a fine gentleman who unites virtue with his

accomplishments. His language is indeed, particularly in contrast

with the simple words of Miranda, somewhat extravagant, but

beneath courtly speech and aristocratic contempt for toil there is

a true heart. Though he resists an insult in the spirit of a courtier,

he is "gentle." The "fearful" savage, Caliban, suffers when com

pared in moral character with the youth from the court. If

Shakespeare, when he brought into contrast Ferdinand and Caliban,

was thinking ofMontaigne's presentation of the virtues of the inno

cent native in that essay, Of the Cannibals, which is so freely used

in The Tempest, he did not give it his full approval, for the natural

man, as represented in Caliban, ismorally inferior to the sophisti

cated prince. Yet for all that, Prospero warns Ferdinand against

that "fire in the blood" to which Caliban has yielded. Though

the thoughts of Ferdinand are all of virtue, the elemental passions

of prince and savage are the same.

How daring and effective a device for the clear presentation of

character Shakespeare has made his use of parallelisms! Not a

character in the play speaks a line out of keeping with what the

dramatist tells of his station and opportunities in life: though

characters greatly unlike utter similar speeches and do similar

deeds, there is always enough difference to accentuate the

dissimilarity of those characters. Prospero's analogy to the witch

Sycorax is so far from making him like her that it makes him more

evidently the learned man, strong through years of study, and her

the witch whose power depends on her contract with the devil.

When Ferdinand does the tasks of Caliban he is so little like Caliban

that he is yet farther removed from the savage by his like occupa

tion: Ferdinand piling a great quantity of logs carries them like a

prince, and Caliban with his burden of fire-wood ismore a serf than

ever. Caliban's speech on the noises of the island ismore impres

sive than that of Ferdinand on the mysterious music of Ariel, partly

because that of Ferdinand is more conventional; but this very

conventionality makes itmore fitting to the character of the prince.

Ferdinand talks of music, and the savage Caliban contrasts himself

with him by speaking of noises. Antonio calls Caliban a "fish"

with the amused contempt of a noble, the more emphatic in con

trast with the vulgar astonishment with which the servant Trinculo

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

74 Gilbert

uses the same word. Miranda and Caliban are both amazed at the

appearance of the strangers who come to the island; but how

different are their expressions of wonder! The verbal similarity of

their exclamations but makes more striking the great difference in

the two characters: Caliban's words are full of vulgar fear, but

Miranda's have in them something of maidenly reverence. The

parallels of the play emphasize the contrasts of the characters in

virtue while bringing out their truth to type. The plan of the

nobles to murder their victims when they are sleeping, made known

in courtly phrases, seems blacker when contrasted with Caliban's

similar plan, set forth in language proper to him. Prospero's

character is more noble when contrasted with that of Sycorax.

When Ferdinand's conduct is set against the foil of the demeanor of

Caliban, the virtues of the prince shine the brighter. What a

difference between his character, as revealed in the speech telling of

the care he will have of his lady's honor, and the disposition that

Caliban manifests in his attempt on her honor!

Though Ferdinand and Gonzalo, who have lived at court, are

virtuous, and Prospero by neglect of his dukedom for retired study

has brought evil on himself and others, the play speaks strongly for

the value of retirement?to spirits fitted to profit by it. On his

solitary island Prospero has perfected the wisdom with which he

looks upon and guides the affairs of men. Yet retirement little

avails him who iswithout a virtuous spirit. Absence from civiliza

tion does not produce perfect character. Caliban, though friendly

to Prospero at first, yet had in his nature a malice that allowed him

to be nothing but evil. The instruction of Prospero had not been

able to affect him for good: his profit from language is that he

knows how to curse. Miranda's noble character has made the

training that Caliban has turned to evil redound to her good, and

she has gained from it profit impossible to princesses who have

more leisure for the vanities of the world. Her innocence and

goodness are Shakespeare's recognition of the truth inMontaigne's

protest against the vices of civilization. Her pure nature, develop

ing in solitude under the care of a tutor able to impart the best of

civilized wisdom, has made her, even among the women of Shakes

"

peare, indeed a "wonder. This Eve of an enchanted paradise has

shown in the island, and one may believe continued to show at

Naples what it is to live the perfect natural life.

Allan H. Gilbert.

Cornell University.

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.195 on Sat, 24 May 2014 04:20:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Tempest - ACT IV Notes Classs NotesDokument5 SeitenThe Tempest - ACT IV Notes Classs NotesAyush PunjabiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Appreciation: FritzDokument4 SeitenA Critical Appreciation: FritzJonathan IyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hope Is A Thing With FeathersDokument3 SeitenHope Is A Thing With FeathersGeetanjali JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forum Birches by Robert FrostDokument5 SeitenForum Birches by Robert FrostQeha YayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest QuestionsDokument3 SeitenThe Tempest QuestionsNancy Ren67% (3)

- The Tempest QuestionsDokument7 SeitenThe Tempest QuestionspattitudeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Riders To The Sea As A One Act PlayDokument2 SeitenRiders To The Sea As A One Act PlayJash KhandelwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Blue BeadDokument7 SeitenThe Blue BeadHHNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest: Performer - Culture & LiteratureDokument15 SeitenThe Tempest: Performer - Culture & Literaturealex180500100% (1)

- Death of A Naturalist by Seamus Heaney The One With The FrogsDokument2 SeitenDeath of A Naturalist by Seamus Heaney The One With The FrogsLeo PavonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dolphins: BedeiugDokument10 SeitenThe Dolphins: BedeiugKabir MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The PatriotDokument7 SeitenThe PatriotSreyash Saha Shaw100% (1)

- Act 4, Scene 1Dokument4 SeitenAct 4, Scene 1Arihant KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birthes-Line by Line ExplanationDokument7 SeitenBirthes-Line by Line ExplanationmeprosenjeetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masculinity in Cat On A Hot Tin RoofDokument8 SeitenMasculinity in Cat On A Hot Tin RoofNini Godoy50% (2)

- Othello TimelineDokument3 SeitenOthello TimelineHo LingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tempest Dramatic SignificanceDokument2 SeitenTempest Dramatic Significancesameera beharry100% (1)

- The Singing Lesson 1Dokument5 SeitenThe Singing Lesson 1Manas GurnaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tempest SummaryDokument1 SeiteTempest SummaryJo March100% (3)

- I Am A Man More Sinned Against Than SinDokument5 SeitenI Am A Man More Sinned Against Than Sinswayamdiptadas22Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Poem HopeDokument9 SeitenThe Poem HopeMai PhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest Act 4 Summary & Analysis +questionsDokument5 SeitenThe Tempest Act 4 Summary & Analysis +questionsHassan SultanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Riders To The Sea - ThemesDokument40 SeitenRiders To The Sea - ThemesWiz MathersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Act 4 Scene 1Dokument1 SeiteAnalysis of Act 4 Scene 1ValiciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macbeth Best Bits PDFDokument19 SeitenMacbeth Best Bits PDFSrdan PetricNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lord of The Flies-QuestionsDokument5 SeitenLord of The Flies-QuestionsIlina DameskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Out Out NotesDokument4 SeitenOut Out NotesJjrlNoch keine Bewertungen

- HSC Notes - TempestDokument10 SeitenHSC Notes - Tempestapi-409521281100% (1)

- Isc Tempest Act 5 LongDokument5 SeitenIsc Tempest Act 5 Longankit100% (1)

- Imagery of Dover BeachDokument6 SeitenImagery of Dover BeachamrieadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The TempestDokument2 SeitenThe TempestDrew Gupte0% (1)

- Sonnet 116Dokument5 SeitenSonnet 116amir sohailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Julius Caesar Persuasive EssayDokument2 SeitenJulius Caesar Persuasive Essayapi-325743280Noch keine Bewertungen

- Scene 2Dokument3 SeitenScene 2Arka PramanikNoch keine Bewertungen

- LR Staging The Storm SceneDokument15 SeitenLR Staging The Storm SceneamnatehreemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ext 1 Intro To Literary Worlds v2Dokument23 SeitenExt 1 Intro To Literary Worlds v2justin gaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest - NotesDokument11 SeitenThe Tempest - NotesAnthonya KnightNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Duchess of MalfiDokument6 SeitenThe Duchess of Malfiapi-370350633% (3)

- PEM 2021 English Advanced Mod A Question For Keats and Bright StarDokument2 SeitenPEM 2021 English Advanced Mod A Question For Keats and Bright StarCorran DrazcruiseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tempest BackgroundDokument3 SeitenTempest Backgroundebarviat100% (1)

- The Death Drive in Shakespeare's Antony and CleopatraDokument8 SeitenThe Death Drive in Shakespeare's Antony and CleopatraJay KennedyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay On Viola From Shakespear's Twelth NightDokument3 SeitenEssay On Viola From Shakespear's Twelth NighttheoremineNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest NarrativeDokument3 SeitenThe Tempest NarrativeAnonymous SY1kBzuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest Miranda and FerdinandDokument5 SeitenThe Tempest Miranda and FerdinandSitar MarianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elizabethan Era Presentation Quiz AccomodatedDokument3 SeitenElizabethan Era Presentation Quiz Accomodatedapi-252069942Noch keine Bewertungen

- Extremes of Gender and PowerDokument12 SeitenExtremes of Gender and PowerMarianela SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest - ALL ACTSDokument12 SeitenThe Tempest - ALL ACTSKai KokoroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Matthew Arnolds Dover BeachDokument2 SeitenAnalysis of Matthew Arnolds Dover BeachP DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 45 Minute TempestDokument24 Seiten45 Minute TempestDeezy WestbrookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Act 3 Scene 3Dokument13 SeitenAct 3 Scene 3He Hsu XiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Immigrants at Central Station, 1951Dokument11 SeitenImmigrants at Central Station, 1951api-255675488Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest 5Dokument9 SeitenThe Tempest 5Reshmi BhowalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The TEMPEST Discussion QuestionsDokument3 SeitenThe TEMPEST Discussion Questionsdjoiajg100% (1)

- A Mid Summers Night DreamDokument24 SeitenA Mid Summers Night DreamKumaresan RamalingamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birches by Robert Lee FrostDokument3 SeitenBirches by Robert Lee FrostanushkahazraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jane Campion's Film Bright Star, and The Facinating Story of DR Cake and John KeatsDokument2 SeitenJane Campion's Film Bright Star, and The Facinating Story of DR Cake and John Keatspeter ellingsenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tempest Workbook (Handbook) 11Dokument52 SeitenThe Tempest Workbook (Handbook) 1121mayrudra.sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parallels and Contrasts in ShakespeareDokument3 SeitenParallels and Contrasts in ShakespeareKingshuk Mondal50% (2)

- Death of NaturalistDokument9 SeitenDeath of NaturalistDana KhairiNoch keine Bewertungen

- South Valley University Faculty of Science Geology Department Dr. Mohamed Youssef AliDokument29 SeitenSouth Valley University Faculty of Science Geology Department Dr. Mohamed Youssef AliHari Dante Cry100% (1)

- Practical Considerations in Modeling: Physical Interactions Taking Place Within A BodyDokument35 SeitenPractical Considerations in Modeling: Physical Interactions Taking Place Within A BodyFábio1 GamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Holowicki Ind5Dokument8 SeitenHolowicki Ind5api-558593025Noch keine Bewertungen

- Application of Eye Patch, Eye Shield and Pressure Dressing To The EyeDokument2 SeitenApplication of Eye Patch, Eye Shield and Pressure Dressing To The EyeissaiahnicolleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topik 3 - Hazard Di Air Selangor, Penilaian Risiko Langkah Kawalan Rev1 2020 090320Dokument59 SeitenTopik 3 - Hazard Di Air Selangor, Penilaian Risiko Langkah Kawalan Rev1 2020 090320Nuratiqah SmailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson PlanDokument18 SeitenLesson PlanYasmin Abigail AseriosNoch keine Bewertungen

- DSR Codes - 1Dokument108 SeitenDSR Codes - 1lakkireddy seshireddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oasis AirlineDokument5 SeitenOasis AirlineRd Indra AdikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESM-4810A1 Energy Storage Module User ManualDokument31 SeitenESM-4810A1 Energy Storage Module User ManualOscar SosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Sensitive Urban Design GuidelineDokument42 SeitenWater Sensitive Urban Design GuidelineTri Wahyuningsih100% (1)

- Introduction To The New 8-Bit PIC MCU Hardware Peripherals (CLC, Nco, Cog)Dokument161 SeitenIntroduction To The New 8-Bit PIC MCU Hardware Peripherals (CLC, Nco, Cog)Andres Bruno SaraviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BMS of Dubai International AirportDokument4 SeitenBMS of Dubai International AirportJomari Carl Rafal MansuetoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strange Christmas TraditionsDokument2 SeitenStrange Christmas TraditionsZsofia ZsofiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLL - Mapeh 6 - Q2 - W8Dokument6 SeitenDLL - Mapeh 6 - Q2 - W8Joe Marie FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smith KJ Student Mathematics Handbook and Integral Table ForDokument328 SeitenSmith KJ Student Mathematics Handbook and Integral Table ForStrahinja DonicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes in Pregnancy: Supervisor: DR Rathimalar By: DR Ashwini Arumugam & DR Laily MokhtarDokument21 SeitenDiabetes in Pregnancy: Supervisor: DR Rathimalar By: DR Ashwini Arumugam & DR Laily MokhtarHarleyquinn96 DrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barium SulphateDokument11 SeitenBarium SulphateGovindanayagi PattabiramanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mid Lesson 1 Ethics & Moral PhiloDokument13 SeitenMid Lesson 1 Ethics & Moral PhiloKate EvangelistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Evaluation of The Strength of Slender Pillars G. S. Esterhuizen, NIOSH, Pittsburgh, PADokument7 SeitenAn Evaluation of The Strength of Slender Pillars G. S. Esterhuizen, NIOSH, Pittsburgh, PAvttrlcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyundai Forklift Catalog PTASDokument15 SeitenHyundai Forklift Catalog PTASjack comboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit-1 Infancy: S.Dharaneeshwari. 1MSC - Home Science-Food &nutritionDokument16 SeitenUnit-1 Infancy: S.Dharaneeshwari. 1MSC - Home Science-Food &nutritionDharaneeshwari Siva-F&NNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Travel Insurance Policy: PreambleDokument20 SeitenInternational Travel Insurance Policy: Preamblethakurankit212Noch keine Bewertungen

- Etl 213-1208.10 enDokument1 SeiteEtl 213-1208.10 enhossamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction: Science and Environment: Brgy - Pampang, Angeles City, PhilippinesDokument65 SeitenIntroduction: Science and Environment: Brgy - Pampang, Angeles City, PhilippinesLance AustriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Setting Times of ConcreteDokument3 SeitenSetting Times of ConcreteP DhanunjayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Vapor Permeability of Polypropylene: Fusion Science and TechnologyDokument5 SeitenWater Vapor Permeability of Polypropylene: Fusion Science and TechnologyBobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boyle's Law 2023Dokument6 SeitenBoyle's Law 2023Justin HuynhNoch keine Bewertungen

- QIAGEN Price List 2017Dokument62 SeitenQIAGEN Price List 2017Dayakar Padmavathi Boddupally80% (5)

- What A Wonderful WorldDokument3 SeitenWhat A Wonderful Worldapi-333684519Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chemical Process DebottleneckingDokument46 SeitenChemical Process DebottleneckingAhmed Ansari100% (2)

- Can't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsVon EverandCan't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (386)

- The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessVon EverandThe Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (456)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesVon EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1636)

- Summary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosVon EverandSummary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (294)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaVon EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessVon EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (328)

- The Whole-Brain Child by Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., and Tina Payne Bryson, PhD. - Book Summary: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing MindVon EverandThe Whole-Brain Child by Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., and Tina Payne Bryson, PhD. - Book Summary: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing MindBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (57)

- Summary of The Algebra of Wealth by Scott Galloway: A Simple Formula for Financial SecurityVon EverandSummary of The Algebra of Wealth by Scott Galloway: A Simple Formula for Financial SecurityNoch keine Bewertungen

- The 5 Second Rule by Mel Robbins - Book Summary: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageVon EverandThe 5 Second Rule by Mel Robbins - Book Summary: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (329)

- Summary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessVon EverandSummary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of The New Menopause by Mary Claire Haver MD: Navigating Your Path Through Hormonal Change with Purpose, Power, and FactsVon EverandSummary of The New Menopause by Mary Claire Haver MD: Navigating Your Path Through Hormonal Change with Purpose, Power, and FactsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The War of Art by Steven Pressfield - Book Summary: Break Through The Blocks And Win Your Inner Creative BattlesVon EverandThe War of Art by Steven Pressfield - Book Summary: Break Through The Blocks And Win Your Inner Creative BattlesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (274)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsVon EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (709)

- Summary of The Algebra of Wealth: A Simple Formula for Financial SecurityVon EverandSummary of The Algebra of Wealth: A Simple Formula for Financial SecurityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Extreme Ownership by Jocko Willink and Leif Babin - Book Summary: How U.S. Navy SEALS Lead And WinVon EverandExtreme Ownership by Jocko Willink and Leif Babin - Book Summary: How U.S. Navy SEALS Lead And WinBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (75)

- How To Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie - Book SummaryVon EverandHow To Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie - Book SummaryBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (557)

- Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties by Tom O'Neill: Conversation StartersVon EverandChaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties by Tom O'Neill: Conversation StartersBewertung: 2.5 von 5 Sternen2.5/5 (3)

- Summary of Atomic Habits by James ClearVon EverandSummary of Atomic Habits by James ClearBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (170)

- Make It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningVon EverandMake It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (55)

- Steal Like an Artist by Austin Kleon - Book Summary: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being CreativeVon EverandSteal Like an Artist by Austin Kleon - Book Summary: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being CreativeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (128)

- Summary of Nuclear War by Annie Jacobsen: A ScenarioVon EverandSummary of Nuclear War by Annie Jacobsen: A ScenarioBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Summary of Eat to Beat Disease by Dr. William LiVon EverandSummary of Eat to Beat Disease by Dr. William LiBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (52)

- Summary of Million Dollar Weekend by Noah Kagan and Tahl Raz: The Surprisingly Simple Way to Launch a 7-Figure Business in 48 HoursVon EverandSummary of Million Dollar Weekend by Noah Kagan and Tahl Raz: The Surprisingly Simple Way to Launch a 7-Figure Business in 48 HoursNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effective Executive by Peter Drucker - Book Summary: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things DoneVon EverandThe Effective Executive by Peter Drucker - Book Summary: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things DoneBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (19)

- Essentialism by Greg McKeown - Book Summary: The Disciplined Pursuit of LessVon EverandEssentialism by Greg McKeown - Book Summary: The Disciplined Pursuit of LessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (188)

- Blink by Malcolm Gladwell - Book Summary: The Power of Thinking Without ThinkingVon EverandBlink by Malcolm Gladwell - Book Summary: The Power of Thinking Without ThinkingBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (114)

- Summary of The Galveston Diet by Mary Claire Haver MD: The Doctor-Developed, Patient-Proven Plan to Burn Fat and Tame Your Hormonal SymptomsVon EverandSummary of The Galveston Diet by Mary Claire Haver MD: The Doctor-Developed, Patient-Proven Plan to Burn Fat and Tame Your Hormonal SymptomsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of "Measure What Matters" by John Doerr: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs — Finish Entire Book in 15 MinutesVon EverandSummary of "Measure What Matters" by John Doerr: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs — Finish Entire Book in 15 MinutesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (62)