Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Balarajan2011 Anemia in Low Incmoe PDF

Hochgeladen von

Jose Luis Marin CatacoraOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Balarajan2011 Anemia in Low Incmoe PDF

Hochgeladen von

Jose Luis Marin CatacoraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review

Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries

Yarlini Balarajan, Usha Ramakrishnan, Emre Özaltin, Anuraj H Shankar, S V Subramanian

Anaemia affects a quarter of the global population, including 293 million (47%) children younger than 5 years and Lancet 2011; 378: 2123–35

468 million (30%) non-pregnant women. In addition to anaemia’s adverse health consequences, the economic effect Published Online

of anaemia on human capital results in the loss of billions of dollars annually. In this paper, we review the August 2, 2011

DOI:10.1016/S0140-

epidemiology, clinical assessment, pathophysiology, and consequences of anaemia in low-income and middle- 6736(10)62304-5

income countries. Our analysis shows that anaemia is disproportionately concentrated in low socioeconomic groups,

Department of Global Health

and that maternal anaemia is strongly associated with child anaemia. Anaemia has multifactorial causes involving and Population

complex interaction between nutrition, infectious diseases, and other factors, and this complexity presents a (Y Balarajan MRCP,

challenge to effectively address the population determinants of anaemia. Reduction of knowledge gaps in research E Özaltin MSc), Department of

Nutrition (A H Shankar DSc),

and policy and improvement of the implementation of effective population-level strategies will help to alleviate the and Department of Society,

anaemia burden in low-resource settings. Human Development and

Health (S V Subramanian PhD),

Introduction distribution of haemoglobin is lower in black people than Harvard School of Public

Health, Boston, MA, USA; and

Anaemia is a major public health problem affecting in white people.7,9,10 Only a few studies from low-income Hubert Department of Global

1·62 billion people globally.1 Although the prevalence of and middle-income countries have, however, examined Health, Rollins School of Public

anaemia is estimated at 9% in countries with high the applicability of these guidelines to other popu- Health at Emory University,

development, in countries with low development the lations.10,11 The use of moderate-to-severe anaemia Atlanta, GA, USA

(U Ramakrishnan PhD)

prevalence is 43%.1 Children and women of reproductive (haemoglobin <90 g/L) has been recommended for

Correspondence to:

age are most at risk, with global anaemia prevalence disease surveillance, especially in high-prevalence Dr S V Subramanian, Professor,

estimates of 47% in children younger than 5 years, 42% in countries, as changes in the high end of the distribution Department of Society, Human

pregnant women, and 30% in non-pregnant women aged are likely to shift more rapidly than those at the low end, Development and Health,

15–49 years,1 and with Africa and Asia accounting for so are more helpful in monitoring progress.12 Harvard School of Public Health,

Boston, MA 02115-6096, USA

more than 85% of the absolute anaemia burden in high- The WHO Global Database on Anaemia for 1993–2005, svsubram@hsph.harvard.edu

risk groups. Anaemia is estimated to contribute to more covering almost half the world’s population, estimated

than 115 000 maternal deaths and 591 000 perinatal deaths the prevalence of anaemia worldwide at 25%.1 About

globally per year.2 The consequences of morbidity 293 million children of preschool age, 56 million preg-

associated with chronic anaemia extend to loss of nant women, and 468 million non-pregnant women are

productivity from impaired work capacity, cognitive estimated to be anaemic (figure 1, webappendix p 1).1 See Online for webappendix

impairment, and increased susceptibility to infection,3 Africa and Asia are the most heavily affected regions,

which also exerts a substantial economic burden.4 with Africa having the highest prevalence of anaemia,

We review present understanding of the epidemiology, and Asia bearing the greater absolute burden.6

clinical assessment, pathophysiology, and consequences Determinants of the prevalence and distribution of

of anaemia, focusing on women of reproductive age and anaemia in a population involve a complex interplay of

children in low-income and middle-income countries. political, ecological, social, and biological factors

We discuss the multifactorial causes of anaemia and the (figure 2). At the country level, anaemia prevalence is

co-occurrence of multiple risk factors in different inversely correlated with economic development

populations and identify potential barriers to effective

anaemia prevention and control.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Epidemiology We searched PubMed using the search terms “anaemia”,

Anaemia is characterised by reductions in haemoglobin “tropical anaemia”, “iron deficiency”, and in combination

concentration, red-cell count, or packed-cell volume, and with “nutrition”, “infectious disease”, “helminths”,

the subsequent impairment in meeting the oxygen “hookworm”, “schistosomiasis”, “malaria”, “HIV/AIDS”,

demands of tissues.5 Table 1 shows the criteria adopted “thalassaemias”, “hemoglobinopathies”, “treatment”, “iron”,

by WHO to define anaemia status by haemoglobin “fortification”, “supplementation”, “developing countries”,

concentration.6 Physiological characteristics such as age, “Africa”, and “Asia”. We focused on publications from the

sex, and pregnancy status, as well as environmental past 10 years, including reviews. We also searched

factors such as smoking and altitude affect haemoglobin publications from international organisations including

concentration. There has been continued discussion WHO, World Bank, and UNICEF, as well as reports from

about the appropriateness of the thresholds used to non-governmental agencies, conference discussions, and

define anaemia and their applicability to different book chapters. We reviewed reference lists of publications

populations, which has implications for epidemiological and reports identified by this search strategy and selected

surveillance, monitoring, and targeting.7,8 For example, those deemed relevant to this Review.

several studies have shown that the population

www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011 2123

Review

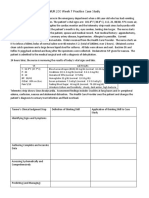

Anaemia is patterned by socioeconomic factors,

Haemoglobin concentration

(g/L) especially by household wealth (table 2). Our pooled

analysis showed that the risk of anaemia among women

Non-pregnant women (>15 years) <120

living in the lowest wealth quintiles was 25% higher

Pregnant women <110

than among those in the highest wealth quintile (table 2).

Children (0·5–4·9 years) <110

Women with no education were more likely to be

Children (5·0–11·9 years) <115

anaemic than were those with greater than secondary

Children (12·0–14·9 years) <120

education. Conditional on women’s socioeconomic

Men (>15 years) <130

status, relative risk of anaemia differed by urban or rural

Table 1: Thresholds of haemoglobin used to define anaemia in different setting. Patterning of anaemia by socioeconomic status

subpopulations, at sea level6 was also noted for children (table 2). A child living in a

household in the lowest wealth quintile was 21% more

likely to be anaemic than were those in the highest

(webappendix p 2). Children and women of reproductive wealth quintile. Risk of anaemia was also raised in

age, in part because of their physiological vulnerability, children whose mothers had no education. Conditional

are at high risk, followed by elderly people, and men.1 on demographic and socioeconomic factors, mother’s

Consequently, assessments of anaemia as well as anaemia status was among the strongest predictors of

interventions and policies to reduce anaemia largely anaemia in children (table 2).

focus on women and children. Adolescents are also a key In individual country analyses, in most countries,

group, with adolescent girls being targeted for women in the lowest wealth quintile or with no education

intervention before the onset of childbearing.13 were more likely to be anaemic than were those in highest

Anaemia is socially patterned by education, wealth, wealth quintile or with greater than secondary education,

occupation (eg, agricultural workers), and residence.14–16 respectively (webappendix pp 6–9). Similar patterns were

In most settings, anaemia is a marker of socioeconomic reported for children (webappendix pp 10–12). Maternal

disadvantage, with the poorest and least educated being anaemia was significantly and positively associated with

at greatest risk of exposure to risk factors for anaemia anaemia in children in all countries (webappendix p 10),

and its sequelae. Analysis of nationally representative and the effects were often stronger than socioeconomic

Demographic and Health Surveys undertaken in factors. Urban–rural differences in anaemia risk were

32 selected low-income and middle-income countries not apparent in most countries for both women and

(panel 1) suggests substantial variation in the prevalence children (webappendix pp 7–9, 11–12).

of anaemia between countries. The proportion of women The second report on the World Nutrition Situation,23

with anaemia varies—for example, being 61% (Benin) based on surveillance data available for 1975–90, reported

and 18% (Honduras), with half or more women having that anaemia prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa and

anaemia in a third of the countries (webappendix p 5). south and southeast Asia probably increased, consistent

In 23 of the 32 countries, the proportion of children with with the fall in dietary iron supply. Only in the near east

anaemia was 50% or higher. and north Africa region were there probable

Anaemia prevalence

Mild (5·0–19·9%)

Moderate (20·0–39·9%)

Severe (≥40·0%)

Regression-based estimate

Figure 1: Global prevalence of anaemia in children of preschool age (0–5 years)

Adapted from reference 6.

2124 www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011

Review

improvements during this period. Other estimates for

1995–2000 based on several different analytical Political economy

approaches showed striking variation in trends across

countries and regions. Interpolation of prevalence using Ecology, climate, geography

regression models estimated that global anaemia

prevalence fell by 0·16% points per year for non-pregnant

women, 0·04% points per year for pregnant women, and

EdEducation

Education Wealth Cultural norms and behaviour

0·36% points per year for children younger than 5 years.24

However, this overall picture masks regional hetero-

geneity; for example, among non-pregnant women

during this period, trends in anaemia worsened in sub- Physiological vulnerability of women and children

Early onset of childbearing, high parity, short birth spacing

Saharan Africa (by 0·18% points per year), the middle

east and north Africa (by 0·06% points per year), and

southeast Asia (by 0·42% points per year). Analysis of

Access to diverse Access to fortified Access to health Access to Access to clean

Demographic and Health Surveys, which are population- food sources food sources services and knowledge and water and

based with standardised methods, suggests that anaemia (quality and interventions education about sanitation,

prevalence has in some cases increased in both women quantity) (eg, iron anaemia insecticide-treated

supplementation, bednets

and children over time (webappendix pp 13–14). deworming)

Assessment of anaemia

The clinical symptoms and signs of anaemia vary and

Inadequate Exposure and

depend on the cause of anaemia and the speed of onset Genetic

nutrient response

haemoglobin

(panel 2). Medical history of signs and symptoms, clinical intake and

disorders

to infectious

absorption disease

examination, blood tests, and additional investigations

should ideally be done to confirm the diagnosis of

anaemia, along with further investigation to establish the

underlying cause. However, in many resource-poor

settings, in which access to routine biochemical and Decreased erythrocyte production Increased erythrocyte loss

haematological testing is scarce, diagnosis relies on

history and clinical examination alone.

As part of international guidelines for the Integrated Anaemia

Management of Childhood Illness,25 clinical assessment

for anaemia in sick children involves assessment of Figure 2: Conceptual model of the determinants of anaemia

palmar pallor. For pregnant women, the specific

symptoms assessed during antenatal care are fatigue and 92% and 94% in populations in which the prevalence of

dyspnoea, and the signs are conjunctival pallor, palmar severe anaemia (haemoglobin <70 g/L) is less than 10%;

pallor, and increased respiratory rate. These symptoms, use of multiple sites to detect pallor maximised

together with diagnostic testing, result in the classification sensitivity.28 The limitation of clinical examination to

of anaemia and subsequent treatment options.26 detect anaemia necessitates the complementary use of

Studies have investigated the sensitivity and specificity blood tests to detect the full extent of the disease.

of clinical signs in diagnosis of anaemia, and these Several haematological and biochemical indicators are

depend on the thresholds used to define anaemia, baseline used in diagnosis and assessment of anaemia and iron

anaemia prevalence, different phenotypes, and observer stores, the relative merits and limitations of which are

training and ability. A meta-analysis of 11 studies27 discussed elsewhere.29–31 Anaemia status is assessed

assessing the accuracy of clinical pallor in children, through haemoglobin concentrations, haematocrit or

mostly from Africa, showed a wide range of sensitivity packed-cell volume, mean cell volume, blood reticulocyte

(29·2–80·9%) and specificity (67·7–90·8%) for different count, blood film analysis, and haemoglobin electro-

signs of pallor (conjunctiva, palm, and nailbed) using phoresis. Since iron deficiency is one of the key causes of

different haemoglobin thresholds for anaemia; no anaemia, additional tests of iron status are also used;

particular anatomical site was deemed highly accurate for these tests include serum or plasma ferritin concentration,

prediction of anaemia. In another study of five populations total iron-binding capacity, transferrin saturation,

in Nepal and Zanzibar,28 pallor at any site (conjunctiva, transferrin receptor concentration, zinc protoporphyrin

palm, and nailbed) was associated with anaemia, although concentration, erythrocyte protoporphyrin concentration,

there were differences in the relative performance of and bone-marrow biopsy.32

these different anatomical sites in diagnosis of anaemia. To distinguish between iron-deficiency anaemia and

The sensitivity of clinical pallor to detect anaemia ranged anaemia of chronic or acute disease is difficult, because

between 60% and 80%, with a specificity between increased circulating hepcidin seen during inflammation

www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011 2125

Review

raised in the acute-phase response, this approach

Panel 1: Epidemiological analysis of anaemia underestimates iron deficiency, rendering the threshold

We used data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS; of lower than 12–15 μg/L inappropriate in settings in

webappendix pp 3–4) to describe the patterns, distribution, which infectious diseases are prevalent. A meta-analysis

and trends in anaemia.17 DHS are nationally representative of 32 studies35 assessing the increase in ferritin associated

household sample surveys measuring indicators of with acute-phase proteins estimated that inflammation

population, health, and nutrition, with special emphasis on increased ferritin by about 30%, leading to an under-

maternal and child health.18 We included all surveys estimation of iron deficiency by 14% (95% CI 7–21). The

measuring anaemia coded with standardised variables for combination of serum ferritin with transferrin receptor

women and children. The target population in most surveys allows some distinction between inflammation and iron

was all women (or in some cases ever-married women) of deficiency, although this finding is yet to be validated in

reproductive age (15–49 years), and all children born to population-based surveys.32 To monitor and assess the

mothers aged 15–49 years at the time of the survey. Anaemia effect of interventions on population-level changes in

was ascertained by measurement of the concentration of iron status, the WHO and US Centers for Disease Control

haemoglobin in capillary blood. Trained investigators and Prevention Technical Consultation recommends the

removed the first two drops of blood after a finger prick (or use of serum ferritin in combination with haemoglobin.32,36

heel prick for young children) and drew the third drop into a However, the complexity of multiple indicators to

cuvette for analysis with the HemoCue system. Anaemia is measure different aspects of anaemia and iron

defined as a haemoglobin concentration of less than 120 g/L metabolism, the knowledge gaps relating to the choice

for women, less than 110 g/L for pregnant women, and less and thresholds of different indicators, the absence of

than 110 g/L for children, adjusted for altitude.6 Mother’s age, research comparing the accuracy of different tests for

education (none, primary, secondary or greater), household haemoglobin concentration and iron status, and the lack

wealth, and urban or rural residence were included as of simple technology to easily measure iron status in the

covariates for analysis of the women’s sample, and for child field present a challenge to population assessment of

analysis we also include child’s age, maternal age at birth anaemia and iron status.

(<17, 17–19, 20–24, 25–29, >30 years), and mother’s anaemia In addition to these technical considerations, operational

status. Household wealth was defined in terms of ownership challenges arise from the different methods and costs. For

of material possessions,19 with each mother or child assigned example, the equipment cost and per-unit cost of testing

a wealth index based on a combination of different materials differs: for haemoglobin testing with portable

household characteristics provided by DHS. This standardised photometers, equipment cost is roughly US$500, unit cost

wealth index was then divided into quintiles for each less than $1; for ferritin, immunoassay testing equipment

country.20,21 We estimated modified Poisson regression cost is roughly $5000, unit cost $5–10; and for transferrin

models, which allows us to calculate relative risks for non-rare receptor, immunoassay testing equipment cost is roughly

events,22 to model the risk of having anaemia, for women and $5000, unit cost $10–15.32 Thus, technical and operational

children separately, pooled across all countries with country knowledge gaps, together with paucity of cost–benefit

fixed-effect, as well as separately for each country. analysis to guide the choice of the haematological and

biochemical testing, adds a substantial challenge to

assessment of anaemia in low-resource settings.

blocks iron release from enterocytes and the

reticuloendothelial system, resulting in iron-deficient Causes and types of anaemia

erythropoiesis. Moreover, since serum ferritin is an Classification

acute-phase protein, raised concentrations in the Anaemia can be broadly classified into decreased

presence of inflammation, as with coexisting infection, erythrocyte production (ineffective erythropoiesis) as a

do not necessarily rule out iron-deficiency anaemia. result of impaired proliferation of red-cell precursors or

C-reactive protein (CRP), another marker of inflamma- ineffective maturation of erythrocytes; or increased loss of

tion, has therefore been used in conjunction with serum erythrocytes through increased destruction (haemolysis)

ferritin, although the threshold of CRP that renders the or blood loss; or both. These processes are broadly

use of serum ferritin unreliable in identifying iron determined by nutrition, infectious disease, and genetics

deficiency is unknown, with thresholds of CRP greater (figure 3).37 Although iron deficiency is thought to be the

than 10–30 mg/L applied.30 major cause of anaemia, postulated to account for around

At the population level, haemoglobin concentration is 50% of anaemia,2 there is little evidence to support such

the most common indicator, because it is inexpensive estimates. Limitations of existing indicators to measure

and easy to measure with field-friendly testing (panel 3). iron status at the population level and scarcity of data

However, it lacks specificity for establishing of iron preclude improved understanding of the relative

status. Therefore, concentrations of serum ferritin and contribution of iron deficiency to anaemia in different

transferrin receptor have been recommended as settings, although studies in specific populations show

measures of population iron status. Since ferritin is that substantial variation exists in the estimated proportion

2126 www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011

Review

of anaemia attributable to iron deficiency. The distribution

Women (n=370 449) Children (n=173 464)

of haemoglobin among populations with and without iron

deficiency also overlaps substantially.32 Clear distinction Maternal anaemia

between anaemia, iron-deficiency anaemia, and iron Yes ·· 1·20 (1·19–1·21)

deficiency, in view of their independent and interdependent No ·· Reference

physiological effects, is impeded by data gaps. The terms Education

anaemia and iron-deficiency anaemia are often used None 1·08 (1·07–1·10) 1·09 (1·08–1·10)

interchangeably, further compounding the confusion. Primary 1·04 (1·03–1·05) 1·05 (1·04–1·07)

Secondary or higher Reference Reference

Nutritional anaemias Wealth quintile

Nutritional anaemias result from insufficient bioavailability Lowest quintile 1·25 (1·23–1·27) 1·21 (1·19–1·22)

of haemopoietic nutrients needed to meet the demands of Second lowest quintile 1·19 (1·18–1·21) 1·18 (1·16–1·20)

haemoglobin and erythrocyte synthesis.31,38 As human Middle quintile 1·15 (1·13–1·16) 1·14 (1·12–1·16)

diets have shifted over time from hunter-gatherer to more Second highest quintile 1·11 (1·09–1·12) 1·10 (1·08–1·12)

cultivated cereal-based diets with more heat exposure Highest quintile Reference Reference

during food preparation, there has been a large drop in Setting

bioavailable haemopoietic nutrients (iron, vitamin B12, Urban 0·98 (0·98–0·99) 1·00 (0·99–1·01)

and folic acid) and absorption enhancers such as vitamin C. Rural Reference Reference

This situation is compounded by increased intake of other

Data are relative risk (95% CI). Models for women were additionally adjusted for

dietary factors that reduce the bioavailability of non-haem age, and models for children were additionally adjusted for child’s age and

iron, such as polyphenols (eg, tea, coffee, and spices such mother’s age at birth.

as cinnamon), phytates (whole grains, legumes), and

Table 2: Relative risk of anaemia in women and children, by household

calcium (dairy products).29,39 Moreover, absorption of

wealth, education, urban or rural residence, and maternal anaemia

nutrients that promote haemopoiesis can be affected by

physiological and pathophysiological factors—for example,

Helicobacter pylori is associated with reduced iron stores Panel 2: Assessment of anaemia5

through several different mechanisms.40,41

Dependent on severity, speed of onset, and underlying cause

Restricted access to diverse micronutrient-rich diets,

of anaemia:

particularly for vulnerable groups, can exacerbate

• Symptoms: fatigue, pallor, exertional dyspnoea,

nutritional anaemias. Whereas each of the micro-

palpitations, angina, claudication, headache, vertigo,

nutrients we discuss has specific roles, multiple

light-headedness, faintness, tinnitus, cramps, increased cold

deficiencies tend to cluster within individuals, and the

sensitivity, anorexia, nausea, change in bowel habits,

synergistic effect of these deficiencies is important in

menstrual irregularities, urinary frequency, and loss of libido

the development of anaemia.

• Signs: pallor (conjunctival, nailbed, palmar, tongue, or

generalised), tachycardia, increased arterial pulsation,

Iron deficiency

capillary pulsation, bruits, cardiac enlargement, signs of

Iron deficiency occurs when the intake of total or

cardiac failure; specific signs related to specific causes

bioavailable iron is inadequate to meet iron demands, or

include koilonychia in iron-deficiency anaemia, jaundice

to compensate for increased losses. Iron has an

in haemolytic anaemia, splenomegaly in hyper-reactive

important role in the function of several biological

malarial splenomegaly, and bone deformities in

processes, and is an integral part of the haemoglobin

thalassaemias

molecule wherein Fe²+ is bound to the protein-

protoporphyrin IX complex to form haem. Lack of

available iron thereby results in low haem concentrations countries this occurrence is compounded by early onset

and hypochromic microcytic anaemia. of childbearing, high number of births, short intervals

Periods of rapid growth, especially during infancy and between births, and poor access to antenatal care and

pregnancy, result in substantial demands for iron, which supplementation.46 The effects of pregnancy and parity

accounts for the physiological vulnerability of children on iron status are long-lasting, with differences in iron

and women. Recurrent menstrual loss accounts for stores as measured by serum ferritin between nulliparous,

roughly 0·48 mg per day, with wide variation depending uniparous, and multiparous women detectable after

on menstrual flow.31,42 During pregnancy, expansion of menopause.43

the red-cell mass and development and maintenance of The intergenerational transfer of poor iron status from

the maternal-placental-fetal unit results in a substantial mother to child has also been shown in several studies,

increase in iron requirements that range from 0·8 mg with maternal iron deficiency increasing the vulnerability

per day in the first trimester to 7·5 mg per day in the of infants to iron deficiency and anaemia.46–49 Low-

third trimester.43,44 Even in developed countries, anaemia birthweight and preterm infants are at increased risk

during pregnancy is common;45 however, in developing because they are born with reduced iron stores. Iron

www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011 2127

Review

nutrition surveys from South America did not reveal

Panel 3: Haemoglobin measurement in population-based population-level folate deficiency in Costa Rica,

surveys Guatemala, or Mexico, but identified high prevalence of

Population-based estimates of anaemia prevalence serum folate deficiency in specific subpopulations of

depend on the sampling design, methods used for Cuban men (64–89%) and Chilean women (25%) before

assessment of haemoglobin concentrations, and thresholds flour fortification.53 Consumption and preparation of

used to define anaemia. folate-rich food varies greatly by region.

• Direct cyanmethaemoglobin: gold standard; needs access

to laboratory with a spectrophotometer within a few Vitamin B12 deficiency

hours of travel time Vitamin B12 is synthesised only by microorganisms, and

• Indirect cyanmethaemoglobin: field-friendly; blood dried its primary source is from ingestion of animal products.

on filter paper, redissolved in laboratory Absorption of vitamin B12 involves a complex process by

• Portable haemoglobin photometers such as HemoCue which gastric enzymes and acid facilitate its release from

system:* field-friendly, portable hand-held device; food sources, before being bound by an intrinsic factor

finger-prick or heel-prick (for children) capillary blood secreted by gastric parietal cells, followed by uptake in

samples sampled at site providing immediate results, the distal ileum. Vitamin B12 deficiency can result in a

used in Demographic and Health Surveys17,33 megaloblastic macrocytic anaemia, which is more

common in severe vitamin B12 deficiency.52

*A study comparing the specificity and sensitivity of these tests to the gold standard, The global prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency is

on both venous and capillary blood samples, recommended the use of HemoCue

with venous blood followed by HemoCue testing of capillary blood for use in remote

unknown, but evidence from several developing

areas.34 Furthermore, this system is easy to use, gives immediate results, and has low countries suggests that deficiency is widespread and is

interobserver error. present throughout life. In South America, at least 40%

of children and adults were vitamin B12 deficient, with

prevalences greater than 70% in Africa and Asia.53,54

deficiency and anaemia in young children are associated However, how much this deficiency contributes to

with various functional consequences, especially in early anaemia is unclear, with few data available for the

childhood development.50 Although the iron content of haematological effect of increasing B12 intake at the

breast milk is low, it is highly bioavailable and exclusive population level.52

breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is recommended. The main causes of vitamin B12 deficiency are

Inadequate access to fortified complementary foods and inadequate dietary intake, especially from vegetarian

iron supplements, and exposure to infections during diets,55 pernicious anaemia, an autoimmune disorder

infant growth increases the risk of anaemia and iron resulting from autoantibody against intrinsic factor,

deficiency in young children. Strategies to lower risk of tropical sprue, and co-infection with Diphyllobothrium

anaemia in early infancy and break the intergenerational latum, Giardia lamblia, and H pylori. Vitamin B12

cycle of iron depletion include optimisation of maternal deficiency is associated with lactovegetarianism in India,

nutritional status, delayed cord clamping at delivery, and the scarcity of meat products in many south Asian

improvement of infant feeding practices, and prevention diets.56–59 The prevalence of pernicious anaemia is

and treatment of infectious disease.31,51 unknown, but reports from several African countries

suggest that it could be more prevalent than was

Folic acid deficiency previously thought.60,61

Folic acid is required for the synthesis and maturation of

erythrocytes, and low serum and erythrocyte Vitamin A deficiency

concentrations of folate can lead to changes in cell Vitamin A deficiency is common in Africa and southeast

morphology and intramedullary death of erythrocytes Asia, affecting an estimated 21% of children of preschool

and reduced erythrocyte lifespan. Folic acid deficiency age and 6% of pregnant women, and accounting for

contributes to megaloblastic anaemia, a condition around 800 000 deaths of women and children worldwide.2

characterised by cells with large and malformed nuclei Vitamin A deficiency results from low dietary intake of

resulting from impaired DNA synthesis. During preformed vitamin A from animal products and

pregnancy, folate demands increase, and women entering carotenoids from fruits and vegetables. Vitamin A plays

pregnancy with poor folate status often develop an important part in erythropoiesis and has been shown

megaloblastic anaemia; furthermore, lactation places to improve haemoglobin concentration and increase the

additional demands with preferential uptake of folate by efficacy of iron supplementation.62 The mechanisms are

mammary glands over maternal requirements. not fully understood, but are suggested to operate

The contribution of folate deficiency to anaemia at the through effects on transferrin receptors affecting the

population level is unknown because few global data mobilisation of iron stores, increasing iron absorption,

exist, although it is thought to be low in developing stimulating erythroid precursors in the bone marrow,

countries.52 Review of epidemiological studies and and reducing susceptibility to infections.

2128 www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011

Review

Soil-transmitted helminths

Infectious diseases can contribute to anaemia through

impaired absorption and metabolism of iron and other Genetic haemoglobin

micronutrients or increased nutrient losses. Of disorders

Thalassaemias

soil-transmitted helminth infections, hookworms Haemoglobin variants

(Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale) are the Glucose-6-phosphate

dehydrogenase deficiency

major cause of anaemia, and are commonly found in Ovalocytosis

sub-Saharan Africa and southeast Asia, with an

estimated 576–740 million infections.63,64 In the tropics Infectious disease

Soil-transmitted helminths

and subtropics, where ecological conditions allow larval Nutrition Malaria

development, hookworm infections are overdispersed Iron deficiency Schistosomiasis

Folic acid deficiency Tuberculosis

or highly aggregated in areas of poverty, where poor Vitamin B12 deficiency AIDS

water, sanitation, and infrastructure result in Vitamin A deficiency Leishmaniasis

endemicity, often concentrated in small populations Protein energy malnutrition Tropical sprue

Malabsorption and disorders

within these areas.65,66 Co-infection with several species of the small intestine

is common.

Hookworms can cause chronic blood loss, with the

severity dependent on the intensity of infection, the Figure 3: Causes of anaemia in countries with low or middle incomes5

species of hookworm (A duodenale is more invasive than

N americanus),67 host iron reserves, and other factors

such as age and comorbidity. Systematic review of acting simultaneously and affected by factors such as

12 studies of deworming during pregnancy68 showed that age, pregnancy, malarial species, previous exposure,

women with light hookworm infection (1–1999 eggs per g and prophylaxis.

of faeces) had a standardised mean difference of The interaction between malaria and iron and folate

haemoglobin that was 0·24 lower (95% CI –0·36 to –0·13) supplementation has been the subject of intense research

than in those with no hookworm. Adult parasites invade and controversy in recent years,73 intensified by the

and attach to the mucosa and submucosa of the small results of two cluster-randomised double-blind inter-

intestine, causing mechanical and chemical damage to vention trials74,75 of iron and folate in preschool children

capillaries and arterioles. By secreting anticlotting agents, in Zanzibar and Nepal. In Zanzibar, an area of high

the parasite ingests the flow of extravasated blood, with P falciparum endemicity, the increased risk of severe

some recycling of lysed erythrocytes and blood. morbidity and mortality in children receiving iron and

Hookworm disease results when chronic blood loss folate supplementation was shown to outweigh the

exceeds iron reserves, inducing iron-deficiency anaemia. benefits.74 The subsequent WHO-led Expert Consultation76

A meta-analysis of 14 randomised controlled trials69 of emphasised the need to exercise caution against

deworming in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia showed a universal iron supplementation for children younger

significant increase in mean haemoglobin (1·71 g/L, than 2 years in malaria-endemic regions where

95% CI 0·70–2·73), with an increased response in those appropriate screening and clinical care are scarce,

provided with iron supplementation. A more recent together with other recommendations. Subsequently, a

meta-analysis of deworming in non-pregnant popu- systematic review of 68 randomised and cluster-

lations70 showed the beneficial effect of anthelmintic randomised trials77 covering 42 981 children did not

treatment, and the differential effects of coadministration identify any adverse effect of iron supplementation on

with praziquantel to target other parasites, or iron risk of clinical malaria or death, in both anaemic and

supplementation to replenish iron stores, or both; for non-anaemic children, in malaria-endemic areas.

example, albendazole together with praziquantel However, this finding relates to settings in which there

increased mean haemoglobin by 2·37 g/L (95% CI are adequate regular malaria surveillance and treatment

1·33–3·50). services in place, which might not be the case in many

low-resource settings. Thus, treatment of children with

Malaria iron supplements should be accompanied by adequate

Malaria causes between 1 million and 3 million deaths screening for and treatment of malaria.

every year,71 a burden falling overwhelmingly on Africa. Other malaria control strategies have had a beneficial

Plasmodium falciparum is the most pathogenic species effect on anaemia. A systematic review of the effect of

and can lead to severe anaemia, and subsequent hypoxia insecticide-treated bednets for prevention of malaria78

and congestive heart failure.72 Our knowledge of the showed a beneficial effect on haemoglobin in children.

mechanisms of malaria-related anaemia has evolved Use of insecticide-treated bednets compared with no

substantially,72 and can be broadly characterised as bednets increased absolute packed-cell volume by 1·7%,

increased erythrocyte destruction and decreased whereas use of treated bednets compared with untreated

erythrocyte production, with mechanisms probably bednets increased absolute packed-cell volume by 0·4%.

www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011 2129

Review

Analysis of nine trials of 5445 children examining the studies are needed to estimate their prevalence in

effect of malaria chemoprophylaxis and intermittent different populations,88 which could also have implications

prevention revealed significant reduction of severe for prevalence estimation of anaemia in populations in

anaemia (RR 0·70, 95% CI 0·52–0·94).79 which these variants are present.8

Each year, more than 330 000 infants are born with

Schistosomiasis these disorders (83% sickle-cell disorders and 17% thalas-

More than 90% of schistosomiasis occurs in sub-Saharan saemias).86 Sickle-cell disorders are associated with

Africa, where there are an estimated 192 million cases chronic haemolytic anaemia, and an estimated 2·28 per

affecting children and young adults,80 with Schistosoma 1000 conceptions worldwide are affected by sickle-cell

haematobium accounting for about two-thirds of these. disorders.86 Thalassaemias are highly prevalent in many

Several cross-sectional studies and randomised trials of Mediterranean, middle eastern, and south and southeast

different treatment options have examined the association Asian countries; an estimated 0·46 per 1000 conceptions

between Schistosoma spp and anaemia.81 However, of the worldwide are affected by homozygous β thalassaemia,

two randomised trials of monotherapy, only one82 showed haemoglobin E/β thalassaemia, homozygous α0

a significant effect of treatment of children with thalassaemia, and α0/α+ thalassaemia (haemoglobin H

praziquantel of about 10 g/L increase in haemoglobin disease).86 Only 12% of transfusion-dependent patients

concentration in a Schistosoma japonicum endemic area with β thalassaemia receive transfusions, and only 39%

in the Philippines, 6 months after the intervention. of those receive adequate iron chelation.86

The mechanisms underlying schistosomiasis-related As child survival improves, inherited haemoglobin

anaemia are not well understood. Postulated mechanisms disorders could become an increasingly important

include iron deficiency from blood loss from haematuria disease burden and cause of anaemia in the future.89

(S haematobium) and bloody diarrhoea (S japonicum and However, many of the recent advances involving genetic

S mansoni); splenic sequestration or increased haemolysis and pharmacological treatments are unlikely to be

by the hypertrophic spleen, or both; autoimmune available in low-resource settings, in which health system

haemolysis; and anaemia of chronic disease driven by requirements for diagnosis and management of these

proinflammatory cytokines.81 Several mechanisms are conditions remain poor.87

likely to be in operation, depending on the species,

intensity of infection, and host interactions. Consequences of anaemia

Background

HIV/AIDS Much of the knowledge pertaining to the health

Anaemia is the most common haematological consequences of anaemia comes from cross-sectional,

complication associated with HIV infection, and is a case-control, and prospective studies examining the

marker of disease progression and survival.83 The burden association between anaemia or haemoglobin on health

of HIV/AIDS-related anaemia falls predominantly on outcomes such as maternal mortality, perinatal mortality,

sub-Saharan Africa, where women and children are most and cognitive outcomes, with much of this evidence

at risk.84 The mechanism of HIV/AIDS-related anaemia relating specifically to iron-deficiency anaemia. As such,

is multifactorial, resulting from HIV infection and the the causal role and attributable fraction of anaemia

induced anaemia of chronic disease, AIDS-related toward various outcomes, although highly suggestive,

illnesses, and antiretroviral treatment. Further research remain to be fully documented.90

is needed to assess the burden and effect of strategies for

HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment on anaemia.85 Maternal and perinatal consequences

Although the causal evidence for adverse consequences

Genetic causes is strong for severe anaemia and maternal outcomes, it

Genetic haemoglobin disorders, which result from remains inconclusive for mild-to-moderate anaemia.90

structural variation or reduced production of globin Assimilation of the evidence from six observational

chains of haemoglobin, can result in anaemia. Estimates studies of anaemia and maternal mortality used to

of the burden of haemoglobin disorders suggest that at estimate the magnitude of the association found a

least 5·2% of the global population, and more than 7% of combined odds ratio (OR) of 0·75 (95% CI 0·62–0·89)

pregnant women, are carriers of a significant haemoglobin associated with a 10 g/L increase in haemoglobin.2 The

variant.86 There is substantial regional variation, with the relation between anaemia and perinatal mortality also

burden falling overwhelmingly on the African and remains inconclusive;91 on the basis of a meta-analysis of

southeast Asian regions, where 18·2% and 6·6% of the ten studies, the estimated combined OR for perinatal

population, respectively, carry a significant haemoglobin mortality associated with a 10 g/L increase in haemoglobin

variant.86 Although extensive research has investigated was 0·72 (95% CI 0·65–0·81). In a subgroup analysis,

the distribution and functional consequences of these the risk in P falciparum malaria endemic areas was

genetic haemoglobin disorders, their contribution to the greater, with a point estimate of 0·65 (0·56–0·75).2 Yet,

global anaemia burden remains unclear.87 Micromapping more recently, evidence from a large prospective cohort

2130 www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011

Review

study in China of more than 160 000 singleton births did in adults and cognitive effect in children. The present

not show an association of maternal anaemia with value of the median physical and cognitive losses

neonatal mortality.92 associated with anaemia and iron deficiency have been

Several studies have investigated the association estimated at US$3·64 per head, or 0·81% of gross

between anaemia and adverse birth outcomes, namely domestic product in selected developing countries.98

preterm birth and low birthweight. These studies have Although these estimates are based on several

had varied results, with heterogeneity in study designs, assumptions and should be interpreted with caution,

settings, and populations.90,93 These heterogeneous they give an idea of the scale of the potential economic

findings relating maternal anaemia to perinatal outcomes consequences of anaemia and iron deficiency. The

might also be affected by the dynamics of haemodilution aggregate effect of small individual losses, especially in

from first to third trimester, and the timing of developing economies in which physical labour is

haemoglobin measurements.94 Several studies have dominant, accrues to billions of dollars of human

investigated the effectiveness of iron supplementation capital—for example, in south Asia, the productivity loss

(with or without folic acid) in pregnant women; systematic is estimated at $4·2 billion annually.4

review of 49 randomised and quasirandomised trials

covering 23 200 women showed that treatment with iron Implementation of anaemia prevention and

or iron and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy control interventions

was associated with increased haemoglobin concen- Several strategies exist for anaemia prevention and

trations at term, and reduced risk of anaemia or iron control, and these include improvement of dietary intake

deficiency at term.95 However, there was no significant and food diversification, food fortification, supple-

reduction in infant or maternal outcomes, such as mentation with iron and other micronutrients,

preterm birth and low birthweight.90,93,95 appropriate disease control, and education (panel 4).

Although we have not reviewed these interventions here,

Cognitive development several are low cost and rank among the more cost-

Despite substantial research into the association between effective interventions at the population level.38,100–107

iron deficiency and cognitive development in children, Furthermore, from a sample of ten developing countries,

and several plausible physiological mechanisms, the the median value of the estimated benefit:cost ratios for

ability to infer causality from existing studies is limited.96 long-term iron fortification programmes was 6:1, and

Although observational studies have reported associations this ratio increased to 8·7:1 when discounted future

between iron-deficiency anaemia and poor cognitive and benefits attributable to cognitive improvements were

motor development, the evidence from randomised trials included in the estimates.4,98 Indeed, the high benefit-to-

has again been inconclusive.97 In an attempt to quantify cost ratios of micronutrient supplementation for children

this association, a meta-analysis of five studies estimated (with vitamin A and zinc), fortification with iron (and salt

that a 10 g/L increase in haemoglobin was associated iodisation), biofortification, deworming, school nutrition

with a 1·73 (95% CI 1·04–2·41) increase in IQ points.2 programmes, and community-based nutrition promotion

However, whether poor cognitive development in iron- have placed these interventions among the top ten global

deficient children is compounded by other factors

affecting social disadvantage, or factors relating to the

timing of iron deficiency during cognitive development, Panel 4: Anaemia prevention and control strategies

is unclear. • Improved dietary intake (quality and quantity) and

increased food diversity with increased iron bioavailability

Work productivity • Fortification of staples with iron (mass and home

The association between iron deficiency and productivity fortification); open-market fortification of selected

has been extensively investigated.3 Iron’s role in oxygen processed food such as breakfast cereals; targeted

transport to muscles and other tissues, and its role in fortification of foods for high-risk groups (eg, infant

other metabolic pathways, show the direct route by formula);99 biofortification

which iron deficiency can reduce aerobic work capacity. • Iron (and folic acid) supplementation (tablets, powders,

This link has been supported by randomised field trials spreads) to high-risk groups—eg, pregnant and lactating

of iron supplementation and work productivity in women, children, adolescents, and women of

developing countries, including rubber plantation reproductive age

workers in Indonesia, female tea-plantation workers in • Disease control (eg, malaria, with insecticide-treated

Sri Lanka, and female cotton-mill workers in China.3,4 In bednets and antimalarial drugs; deworming in

countries in which physical labour is prevalent, reduced helminth-endemic areas; handwashing)

work performance due to anaemia has substantial • Improved knowledge and education about anaemia

economic consequences.4 prevention and control, for both civil society and

Attempts to quantify the economic burden of iron policy makers

deficiency have focused on the loss of work productivity

www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011 2131

Review

Policy makers Human resources Beneficiaries

Policy Insufficient political priority Limited leadership and capacity of existing Limited mobilisation of civil society to demand

Poor awareness of the magnitude and consequences of anaemia burden human resources to champion anaemia policy attention to address anaemia

Challenge of coordination of necessary multisectoral policy response prevention and control Challenge of addressing needs of vulnerable groups

(food and agriculture, health systems, water and sanitation, etc)

Resources Little financial commitment for anaemia Lack of institutional and operational capacity Restricted financial access to iron-rich food sources,

Poor coordination of resources to support multisectoral response for scaling up of coverage of high-quality iron supplements, health services, etc

Inflexibility of financial disbursements for related health issues maternal and child health services Limited supply and access to iron supplementation

(eg, malaria, reproductive health) to be used towards anaemia control Challenge of integration of anaemia control and maternal health services to reinforce anaemia

into existing programmes and initiatives prevention

Poor awareness of need for anaemia

prevention and control

Knowledge Poor awareness of the magnitude of disease burden due to the Technical and operational knowledge gaps to Lack of education and information about anaemia

insidious, latent presentation of anaemia, and long-term guide more effective implementation prevention, and awareness of benefits of

consequences Little knowledge of how to integrate anaemia appropriate intervention

Technical knowledge gaps include: validity and cost-benefit of tests for control into existing programmes Poor compliance with iron supplementation

assessment of anaemia prevalence; challenge of assessment of local Little individual and community awareness of

determinants of anaemia; challenge of measurement of the anaemia status due to latent symptoms and signs

effectiveness of interventions; uncertainty as to best strategic response

to address anaemia in different groups

Poor knowledge about how to coordinate the policy and

implementation response to the context-specific causes of anaemia

Table 3: Barriers to effective implementation of anaemia prevention and control strategies

priorities to address the world’s important challenges by practices.113 Also, evidence from several countries suggests

the 2008 Copenhagen Consensus.103 that increased contact with health providers without due

However, several barriers impede anaemia prevention attention to the quality of services could fail to improve

and control strategies (table 3). Also, there are service delivery.112 Investment in the quality of community

implementation challenges relating to delivery and health workers, fostering of community awareness of the

scale-up of existing anaemia interventions; addressing benefits of addressing anaemia, and increasing of the

implementation knowledge gaps, and maximising social acceptability of interventions through community-

opportunity to learn from past failures and successes based approaches also needs further consideration and

could improve understanding of how to achieve and could help to improve results.114

sustain impact. Studies that provide evidence to aid Crucially, the timely availability and accuracy of data,

policy makers are needed, such as those that evaluate and its routine use to identify specific performance

effectiveness and measure the effect of interventions— bottlenecks, target solutions, and assess effect, will

for example, few studies have assessed the national underlie the successful implementation of anaemia

population-level effectiveness of fortification control strategies. For anaemia in particular, local data

interventions of staple foods in children.108 collection for decision making is important to guide

Another key challenge is meeting the needs of high-risk appropriate targeted packages of interventions to

groups at specific times in their lives—namely, pregnant address the different types of anaemia. We remain

women, infants (especially preterm or low-birthweight), unclear as to the contribution of different causes of

and adolescent girls, and balancing this strategy with anaemia in different settings; elucidating the pattern of

broader population-level approaches. Combination of the risk factors such as helminth infection and malaria is

different strategies needed during the continuum of care, crucial to identification of local determinants of anaemia.

together with interventions for the general population, This process might in the interim necessitate alternative

present complexity and necessitate assessment of the strategies such as synergism of data collection, sampling

programme effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and safety of of specific high-risk populations, and development of

combinations of interventions, and implementation methods to indirectly estimate clustering of co-infection

within the constraints of restricted resources and health and anaemia through methods such as prediction

systems in these settings.109 The low coverage of maternal modelling or spatial analysis. Geographical information

and child health interventions, and the poor quality of systems can be used to map anaemia and infectious

these services,110,111 add to this challenge. For example, diseases for data analysis, prediction of populations at

although antenatal care coverage is improving, gaps in the risk, and planning and monitoring of interventions.115–117

delivery of specific interventions (such as iron and folic Improved understanding of the clustering of risk factors

acid supplementation) remain.112 Inadequate investment and the distribution of co-infection is needed to build

in financial and human resources hampers the imple- the evidence base for strategies offering synergies to

mentation of maternal and child health interventions, as address multiple causes with a more coordinated

does scarce evidence for the effectiveness of policies and context-specific approach.117

2132 www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011

Review

Conclusion 10 Himes J, Walker S, Williams S, Bennett F, Grantham-McGregor S.

Global inequalities in anaemia reflect the stark A method to estimate prevalence of iron deficiency and iron

deficiency anemia in adolescent Jamaican girls. Am J Clin Nutr

differences between developing and developed countries 1997; 65: 831–36.

and the differential exposure to the varied determinants 11 Khusun H, Yip R, Schultink W, Dillon DHS. World Health

of anaemia. Anaemia continues to be an endemic Organization hemoglobin cut-off points for the detection of anemia

are valid for an Indonesian population. J Nutr 1999; 129: 1669–74.

problem of large magnitude, and the increasing trends 12 Stoltzfus RJ. Rethinking anaemia surveillance. Lancet 1997;

in several developing countries point to the failures of 349: 1764–66.

existing approaches to alleviate this burden. Overcoming 13 Micronutrient Initiative. Investing in the future: a united call

to action on vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Ottawa, Canada:

political, operational, and technical barriers to anaemia Micronutrient Initiative, 2009.

control will foster more effective implementation of 14 Shamah-Levy T, Villalpando S, Rivera JA, Mejia-Rodriguez F,

policies and strategies. Engagement of diverse Camacho-Cisneros M, Monterrubio EA. Anemia in Mexican

stakeholders and building of capacity is needed to effect women: a public health problem. Salud Publica Mex 2003;

45 (suppl 4): S499–507.

such change, as is sustained commitment and 15 Ngnie-Teta I, Kuate-Defo B, Receveur O. Multilevel modelling

investment in anaemia reduction.118,119 Addressing the of sociodemographic predictors of various levels of anaemia among

challenge of anaemia will necessitate a holistic response women in Mali. Public Health Nutr 2009; 12: 1462–69.

16 Ghosh S. Exploring socioeconomic vulnerability of anaemia

to both the proximate and distal determinants of among women in eastern Indian States. J Biosoc Sci 2009;

anaemia, together with consideration of the 41: 763–87.

intergenerational aspects. Identification of the local 17 Measure DHS. Demographic and health surveys. http://www.

measuredhs.com/ (accessed April 19, 2009).

determinants of anaemia and improvement of the

18 Rutstein SO, Rojas G. Guide to DHS statistics. Calverton, MD,

implementation of contextually appropriate strategies USA: ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS+, 2003.

will be crucial for progress in this important global 19 Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without

health issue. expenditure data—or tears: an application to educational

enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001; 38: 115–32.

Contributors 20 Gwatkin DR, Rustein S, Johnson K, Pande RP, Wagstaff A.

YB and SVS conceptualised the study and developed the framework Socioeconomic differences in health, nutrition, and population in

for the Review. YB led the writing of the Review. SVS contributed to India. For the HNP/Poverty Thematic Group of The World Bank.

critical revisions, writing, and supervised the Review. UR and Washington, DC, USA: World Bank, 2000.

AHS contributed to critical revisions and writing of the Review. 21 Rutstein SO, Johnson, K. The DHS wealth asset index. Report

EÖ contributed to data analysis and writing. All authors have read and No: 6. Calverton, MD, USA: ORC Macro, 2004.

approved the Review. 22 Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective

studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159: 702–06.

Conflicts of interest

23 United Nations. Subcommittee on Nutrition, International

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Food Policy Research Institute. Second report on the world nutrition

Acknowledgments situation: a report compiled from information available to the United

None of the authors received funding for this Review. We thank Nations agencies of the ACC/SCN. Geneva, Switzerland: United

Emily O’Donnell for her assistance with preparation of tables and Nations ACC Sub-Committee on Nutrition, 1992.

graphs, Jeff Blossom for his assistance with the preparation of the maps, 24 Mason J, Rivers J, Helwig C. Recent trends in malnutrition in

and Donald Halstead for his comments on the manuscript.. developing regions: vitamin A deficiency, anemia, iodine deficiency,

and child underweight. Food Nutr Bull 2005; 26: 57.

References 25 WHO. Department of Child and Adolescent Health and

1 McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide Development, UNICEF. Handbook: IMCI integrated management

prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition of childhood illness. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health

Information System, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutr 2009; Organization, 2005.

12: 444–54. 26 World Health Organization. Department of Reproductive Health

2 Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers AA, Murray CJL. Comparative and Research. Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care:

quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease a guide for essential practice. 2nd edn. Geneva, Switzerland: World

attributable to selected major risk factors. Geneva, Switzerland: Health Organization, 2006.

World Health Organization, 2004. 27 Chalco J, Huicho L, Alamo C, Carreazo N, Bada C. Accuracy

3 Haas JD, Brownlie T 4th. Iron deficiency and reduced work of clinical pallor in the diagnosis of anaemia in children:

capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal a meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 2005; 5: 46.

relationship. J Nutr 2001; 131 (2S-2): 676–88S; discussion 688–90S. 28 Stoltzfus RJ, Edward-Raj A, Dreyfuss ML, et al. Clinical pallor is

4 Horton S, Ross J. The economics of iron deficiency. Food Policy useful to detect severe anemia in populations where anemia is

2003; 28: 51–75. prevalent and severe. J Nutr 1999; 129: 1675–81.

5 Warrell D, Cox T, Firth J, Benz E. Oxford textbook of medicine. 29 Zimmermann MB, Hurrell RF. Nutritional iron deficiency.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003. Lancet 2007; 370: 511–20.

6 WHO. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005: WHO global 30 Zimmermann MB. Methods to assess iron and iodine status.

database on anaemia. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Br J Nutr 2008; 99 (suppl S3): S2–9.

Organization, 2008. 31 Ramakrishnan U. Nutritional anemias. Boca Raton, USA: CRC

7 Dallman P, Barr G, Allen C, Shinefield H. Hemoglobin Press, 2001.

concentration in white, black, and Oriental children: is there a need 32 WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessing

for separate criteria in screening for anemia? Am J Clin Nutr 1978; the iron status of populations: a report of a joint World Health

31: 377–80. Organization/Centers for Disease Control technical consultation

8 Beutler E, Waalen J. The definition of anemia: what is the lower on the assessment of iron status at the population level. Geneva,

limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood 2006; Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004.

107: 1747–50. 33 Sharman A. Anemia testing in population-based surveys: General

9 Johnson-Spear M, Yip R. Hemoglobin difference between black information and guidelines for country monitors and program

and white women with comparable iron status: justification for managers. Calverton, MD, USA: ORC Macro, 2000.

race-specific anemia criteria. Am J Clin Nutr 1994; 60: 117.

www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011 2133

Review

34 Sari M, de Pee S, Martini E, et al. Estimating the prevalence of 60 Savage D, Gangaidzo I, Lindenbaum J, Kiire C, Mukiibi JM.

anaemia: a comparison of three methods. Bull World Health Organ Vitamin B12 deficiency is the primary cause of megaloblastic

2001; 79: 506. anaemia in Zimbabwe. Br J Haematol 1994; 86: 844.

35 Thurnham DI, McCabe LD, Haldar S, Wieringa FT, 61 Stabler SP, Allen RH. Vitamin B12 deficiency as a worldwide

Northrop-Clewes CA, McCabe GP. Adjusting plasma ferritin problem. Annu Rev Nutr 2004; 24: 299–326.

concentrations to remove the effects of subclinical inflammation in 62 Fishman SM, Christian P, West KP. The role of vitamins in the

the assessment of iron deficiency: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr prevention and control of anaemia. Public Health Nutr 2000;

2010; 92: 546–55. 3: 125–50.

36 Mei Z, Cogswell ME, Parvanta I, et al. Hemoglobin and ferritin are 63 de Silva NR, Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Montresor A, Engels D,

currently the most efficient indicators of population response to Savioli L. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the

iron interventions: an analysis of nine randomized controlled trials. global picture. Trends Parasitol 2003; 19: 547–51.

J Nutr 2005; 135: 1974–80. 64 Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted

37 Tolentino K, Friedman JF. An update on anemia in less developed helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm.

countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 77: 44–51. Lancet 2006; 367: 1521–32.

38 Semba RD, Bloem MW. Nutrition and health in developing 65 Anderson RM, May RM, Baker JR, Muller R. Helminth infections

countries. Totowa, USA: Humana Press, 2008. of humans: mathematical models, population dynamics, and

39 Hurrell RF, Reddy M, Cook JD. Inhibition of non-haem iron control. Adv Parasitol 1985; 24: 1–101.

absorption in man by polyphenolic-containing beverages. 66 Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM, Bottazzi ME, Loukas A, Xiao S.

Br J Nutr 1999; 81: 289–95. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 799–807.

40 Khitam M, Dani C. Helicobacter pylori infection and iron stores: 67 Albonjco M, Stoltzfus RJ, Savioli L, et al. Epidemiological

a systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter 2008; 13: 323–40. evidence for a differential effect of hookworm species,

41 Qu XH, Huang XL, Xiong P, et al. Does Helicobacter pylori infection Ancylostoma duodenale or Necator americanus, on iron status of

play a role in iron deficiency anemia? A meta-analysis. children. Int J Epidemiol 1998; 27: 530–37.

World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16: 886–96. 68 Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Bundy DA. Hookworm-related anaemia

42 Guillebaud J, Bonnar J, Morehead J, Matthews A. Menstrual among pregnant women: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis

blood-loss with intrauterine devices. Lancet 1976; 307: 387–90. 2008; 2: e291.

43 Milman N. Iron and pregnancy—a delicate balance. Ann Hematol 69 Gulani A, Nagpal J, Osmond C, Sachdev HPS. Effect of

2006; 85: 559–65. administration of intestinal anthelmintic drugs on haemoglobin:

44 Bothwell TH. Iron requirements in pregnancy and strategies systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2007;

to meet them. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72: 257S–64. 334: 1095.

45 Milman N. Prepartum anaemia: prevention and treatment. 70 Smith JL, Brooker S. Impact of hookworm infection and

Ann Hematol 2008; 87: 949–59. deworming on anaemia in non-pregnant populations: a

46 Kalaivani K. Prevalence and consequences of anaemia in pregnancy. systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15: 776–95.

Indian J Med Res 2009; 130: 627–33. 71 Breman JG, Alilio MS, Mills A. Conquering the intolerable

47 de Pee S, Bloem MW, Sari M, Kiess L, Yip R, Kosen S. The high burden of malaria: what’s new, what’s needed: a summary.

prevalence of low hemoglobin concentration among indonesian Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71 (2 suppl): 1–15.

infants aged 3-5 months is related to maternal anemia. J Nutr 2002; 72 Menendez C, Fleming AF, Alonso PL. Malaria-related anaemia.

132: 2215–21. Parasitol Today 2000; 16: 469–76.

48 Meinzen-Derr JK, Guerrero ML, Altaye M, Ortega-Gallegos H, 73 Prentice AM. Iron metabolism, malaria, and other infections:

Ruiz-Palacios GM, Morrow AL. Risk of infant anemia is associated what is all the fuss about? J Nutr 2008; 138: 2537–41.

with exclusive breast-feeding and maternal anemia in a Mexican 74 Sazawal S, Black RE, Ramsan M, et al. Effects of routine

cohort. J Nutr 2006; 136: 452–58. prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on

49 Colomer J, Colomer C, Gutierrez D, et al. Anaemia during admission to hospital and mortality in preschool children in a

pregnancy as a risk factor for infant iron deficiency: report from high malaria transmission setting: community-based,

the Valencia Infant Anaemia Cohort (VIAC) study. randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2006; 367: 133–43.

Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1990; 4: 196–204. 75 Tielsch JM, Khatry SK, Stoltzfus RJ, et al. Effect of routine

50 Lozoff B, De Andraca I, Castillo M, Smith J, Walter T, Pino P. prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on

Behavioral and developmental effects of preventing iron-deficiency preschool child mortality in southern Nepal: community-based,

anemia in healthy full-term infants. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 846. cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2006;

51 Chaparro CM. Setting the stage for child health and development: 367: 144–52.

prevention of iron deficiency in early infancy. J Nutr 2008; 76 Allen L, Black RE, Brandes N, et al. Conclusions and

138: 2529–33. recommendations of a WHO expert consultation meeting on iron

52 Metz J. A high prevalence of biochemical evidence of vitamin B12 supplementation for infants and young children in malaria

or folate deficiency does not translate into a comparable prevalence endemic areas. Med Trop (Mars) 2008; 68: 182–88 (in French).

of anemia. Food Nutr Bull 2008; 29 (2 suppl): S74. 77 Ojukwu J, Okebe J, Yahav D, Paul M. Oral iron supplementation

53 Allen LH. Folate and vitamin B12 status in the Americas. for preventing or treating anaemia among children in malaria-

Nutr Rev 2004; 62 (s1): S29–33. endemic areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD006589.

54 Allen LH. How common is vitamin B-12 deficiency? Am J Clin Nutr 78 Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for

2009; 89: 693S–96. preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;

2: CD000363.

55 Antony AC. Vegetarianism and vitamin B-12 (cobalamin) deficiency.

Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 78: 3. 79 Meremikwu M, Donegan S, Esu E. Chemoprophylaxis and

intermittent treatment for preventing malaria in children.

56 Misra A, Vikram NK, Pandey RM, Dwivedi M, Ahmad FU.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 2: CD003756.

Hyperhomocysteinemia, and low intakes of folic acid and

vitamin B12 in urban North India. Eur J Nutr 2002; 41: 68–77. 80 Hotez PJ, Kamath A. Neglected tropical diseases in sub-Saharan

Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution, and disease

57 Modood ul M, Anwar M, Saleem M, Wiqar A, Ahmad M. A study

burden. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009; 3: e412.

of serum vitamin B12 and folate levels in patients of megaloblastic

anaemia in northern Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 1995; 45: 187. 81 Friedman JF, Kanzaria HK, McGarvey ST. Human

schistosomiasis and anemia: the relationship and potential

58 Antony AC. Prevalence of cobalamin (vitamin B-12) and folate

mechanisms. Trends Parasitol 2005; 21: 386–92.

deficiency in India—audi alteram partem. Am J Clin Nutr 2001; 74: 157.

82 McGarvey ST, Aligui G, Graham KK, Peters P, Olds GR, Olveda R.

59 Bondevik GT, Schneede J, Refsum H, Lie RT, Ulstein M.

Schistosomiasis japonica and childhood nutritional status in

Homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels in pregnant Nepali

northeastern Leyte, the Philippines: a randomized trial of

women. Should cobalamin supplementation be considered.

praziquantel versus placebo. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1996; 54: 498–502.

Eur J Clin Nutr 2001; 55: 856.

2134 www.thelancet.com Vol 378 December 17/24/31, 2011

Review

83 Volberding PA, Levine AM, Dieterich D, Mildvan D, Mitsuyasu R, 103 Consensus Consensus Center. Copenhagen Consensus 2008

Saag M. Anemia in HIV infection: clinical impact and evidence-based results. http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/Projects/

management strategies. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 1454–63. Copenhagen%20Consensus%202008/Outcome.aspx

84 Calis JC, van Hensbroek MB, de Haan RJ, Moons P, Brabin BJ, (accessed May 16, 2011).

Bates I. HIV-associated anemia in children: a systematic review 104 Fiedler JL, Sanghvi TG, Saunders MK. A review of the

from a global perspective. AIDS 2008; 22: 1099–112. micronutrient intervention cost literature: program design

85 Adetifa I, Okomo U. Iron supplementation for reducing morbidity and policy lessons. Int J Health Plann Manage 2008; 23: 373–97.

and mortality in children with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 105 Lutter CK. Iron deficiency in young children in low-income

2009; 1: CD006736. countries and new approaches for its prevention. J Nutr 2008;

86 Modell B, Darlison M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin 138: 2523–28.

disorders and derived service indicators. Bull World Health Organ 106 Allen LH. Iron supplements: scientific issues concerning efficacy

2008; 86: 480–87. and implications for research and programs. J Nutr 2002;

87 Weatherall DJ. Hemoglobinopathies worldwide: present and future. 132: 813S–19.

Curr Mol Med 2008; 8: 592–99. 107 Hurrell R, Ranum P, de Pee S, et al. Revised recommendations for

88 Weatherall DJ. The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are iron fortification of wheat flour and an evaluation of the expected

an emerging global health burden. Blood 2010; 115: 4331–36. impact of current national wheat flour fortification programs.

89 Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. Inherited haemoglobin disorders: an Food Nutr Bull 2010; 31 (1 suppl): S7–21.

increasing global health problem. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 108 Semba RD, Moench-Pfanner R, Sun K, et al. Iron-fortified milk and

79: 704–12. noodle consumption is associated with lower risk of anemia among

90 Allen LH. Anemia and iron deficiency: effects on pregnancy children aged 6–59 mo in Indonesia. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;

outcome. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71: 1280S–84. 92: 170–76.

91 Rasmussen KM. Is there a causal relationship between iron 109 Yip R, Ramakrishnan U. Experiences and challenges in developing

deficiency or iron-deficiency anemia and weight at birth, length countries. J Nutr 2002; 132: 827S–30S.

of gestation and perinatal mortality? J Nutr 2001; 131: 590S–603. 110 Shankar A, Bartlett L, Fauveau V, Islam M, Terreri N, on behalf of

92 Zhang Q, Ananth CV, Rhoads GG, Li Z. The impact of maternal the Countdown to 2015 Maternal Health Group. Delivery of MDG 5

anemia on perinatal mortality: a population-based, prospective by active management with data. Lancet 2008; 371: 1223–24.

cohort study in China. Ann Epidemiol 2009; 19: 793–99. 111 Van Den Broek NR, Graham WJ. Quality of care for maternal and

93 Abu-Saad K, Fraser D. Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. newborn health: the neglected agenda. BJOG 2009; 116: 18–21.

Epidemiol Rev 2010; 32: 5–25. 112 WHO, UNICEF. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–2010)

94 Xiong X, Buekens P, Alexander S, Demianczuk N, Wollast E. with country profiles: taking stock of maternal, newborn and child

Anemia during pregnancy and birth outcome: a meta-analysis. survival. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2010.

Amer J Perinatol 2000; 17: 137–46. 113 Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, et al. Countdown to 2015 decade

95 Peña-Rosas JP, Viteri FE. Effects and safety of preventive oral iron report (2000–10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child

or iron+folic acid supplementation for women during pregnancy. survival. Lancet 2010; 375: 2032–44.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD004736. 114 Bhutta ZA, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, Huicho L. Global experience of

96 McCann JC, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relation community health workers for delivery of health related Millennium

between iron deficiency during development and deficits in Development Goals: a systematic review, country case studies, and

cognitive or behavioral function. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 85: 931–45. recommendations for scaling up. Geneva, Switzerland: World

Health Organization, Global Health Workforce Alliance, 2010.

97 Grantham-McGregor S, Ani C. A review of studies on the effect of

iron deficiency on cognitive development in children. J Nutr 2001; 115 Brooker S, Michael E. The potential of geographical information

131: 649S–68. systems and remote sensing in the epidemiology and control of

human helminth infections. Adv Parasitol 2000; 47: 245–88.

98 Horton S, Ross J. Corrigendum to: “The economics of iron