Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Idiots and Fools

Hochgeladen von

Nasser AmmarCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Idiots and Fools

Hochgeladen von

Nasser AmmarCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

J a m e s M .

B o urke

B r u n E i

A Rough Guide to

Language Awareness

F

or teachers of a second lan- of grammatical rules for themselves.

guage (L2), the role of grammar This new way of looking at grammar

instruction in the classroom instruction has come to be known as

has been a perennial subject of debate language awareness, among other des-

and has undergone many changes ignations. This article will discuss the

over the years. For example, the once background and rationale of language

well-respected traditional methods awareness, and will introduce a few of

that relied on extensive drilling and the techniques that teachers can use

memorization of grammar evoked a to help students discover grammatical

backlash in the 1970s, which resulted relationships and improve their learn-

in new methods that excluded gram- ing of English.

mar instruction in favor of “natu-

The demise of traditional

ral” communication in the classroom.

Nevertheless, the topic of grammar grammar instruction

remained a live issue, and throughout Traditional grammar instruction, as it

the 1980s and 1990s, research in the was commonly called, was criticized

classroom reported positive results for its long-winded teacher explana-

for grammar instruction. Even so, tions, its drills and drudgery, and

the communicative methods had an its boring and banal exercises. In

enduring effect, and the traditional the 1970s, new teaching methods

methods of teaching grammar did appeared that replaced grammar exer-

not return; instead, techniques were cises with meaningful communicative

developed whereby students would environments. In general, the goal was

be able to “notice” grammar, often to mirror the way a person learned his

spontaneously in the course of a com- or her first language, an approach that

municative lesson, and especially if was derived from the linguistic theories

the grammatical problem impeded of Chomsky (1965), who pointed out

comprehension. In this way, learners that humans are endowed with a lan-

would notice and learn the pattern guage acquisition device that enables

12 2008 N u m b e r 1 | E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 12 12/19/07 10:02:06 AM

that enables them to acquire whatever lan- The result was a number of do-it-yourself

guage they are exposed to. According to strategies devised by second language teachers

Chomsky (1965, 36), our “organ of language” to enable learners to analyze and internalize

extracts the rules of the target language from language rules and systems. These various

the data of performance, and this innate sche- tools and techniques differ considerably in

ma comprises “linguistic universals,” which their specific aims and in the manner in which

are part of our genetic inheritance. they are implemented, but they all have a

Chomsky’s theories revolutionized the common purpose, which is to raise learners’

field of linguistics, and had a dramatic impact awareness of important linguistic features,

on language teaching as well. The basic to see what attributes these features share, to

assumption underpinning the communicative notice how they differ from other related fea-

approach is that language is made in the mind tures, and, in time, to help learners construct

and is internal, a process that generates what their own grammar from personal exploration

Chomsky (1986) refers to as I-language. This and trial-and-error tasks.

suggests that language cannot be acquired by

putting learners through a series of linguistic Language awareness defined

hoops, which is the approach found in the Language awareness fits into this new

traditional grammar book, and what Chom- paradigm, and is defined as “the development

sky calls E-language, language external to the in learners of an enhanced consciousness of

learner. and sensitivity to the forms and functions of

Based on Chomsky’s theories, “nativists,” language” (Carter 2003, 64). Since the early

including Krashen (1981), Prabhu (1987), 1990s, an impressive body of research shows

and others, argued against explicit grammatical that conscious learning (especially the kind

instruction in favor of the naturalistic “discov- one would characterize as language aware-

ery” of the target language’s rule system. In the ness) also builds interlanguage, one’s interim

early 1980s, Krashen (1981) proclaimed that grammar in the mind. Interlanguage has to

exposure to comprehensible input in a stress- grow and develop; otherwise, fossilization sets

free environment was the primary condition in and learners may exhibit the all-too-famil-

for successful L2 acquisition. However, at the iar symptoms of a “grammar gap” (Bourke

same time this was being propagated, a num- 1989, 21). Many learners seem to experience

ber of researchers were investigating the effect this gap and need remedial work in order to

of formal instruction on L2 acquisition. Long eradicate fossilized errors. For this reason, the

(1983), for instance, in an extensive review of present author refers to language awareness as

the empirical research, found that certain types linguistic problem-solving (Bourke 1992).

of instruction did make a significant difference Other definitions that are similar to lan-

and hence one could no longer accept the guage awareness include consciousness-raising

nativist argument that the effects of grammar (Rutherford 1987; Schmidt 1990; Fotos

teaching appear to be peripheral and fragile. 1993; Sharwood Smith 1993); focus on form

(Long 1991; Doughty and Williams 1998);

The reincarnation of grammar instruction grammar interpretation tasks (Ellis 1995); and

In spite of the reaction against direct gram- form-focused instruction (Ellis 2001; Hinkel

mar instruction, many researchers and practi- and Fotos 2002).

tioners continued to strongly advocate for the It should be noted that James (1998)

role of conscious learning and have produced makes a fine distinction between language

a number of studies concluding that syntax awareness and consciousness-raising (CR). He

can and should be taught, and that formal suggests that language awareness is a learned

instruction makes a difference. However, even ability to analyze one’s internalized language,

though these researchers supported grammar be it the first language or that part of the L2

teaching, they also recognized that interven- that one has acquired so far. In other words, it

tion by means of traditional exercises such as is about making implicit knowledge explicit.

drills and slot-filling exercises, are much less On the other hand, CR refers to getting

effective than the communicative techniques explicit insight into what one does not yet

that supplanted it. know implicitly of the L2. James (1998, 260)

E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m | Number 1 2008 13

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 13 12/19/07 10:02:06 AM

concludes: Language awareness “is for know- the sum of the enabling strategies one

ers and CR is for learners.” Rightly or wrong- uses to get a handle on the language

ly, however, most applied linguists nowadays system. It employs cognitive strategies,

regard the two terms as synonymous. such as noticing, hypothesis testing,

Language awareness does differ from some problem-solving, and restructuring.

of the above definitions in that it is wider in • LA comes out of an initial focus on

scope, including not only grammatical aware- meaning. The objective is to investigate

ness but also lexical awareness, phonological which forms are available in English to

awareness, and discourse awareness. In order realize certain meanings, notions, and

to simplify matters, I shall refer to all of these

language functions. Whereas traditional

approaches as language awareness (LA), as

grammar was a grammar of classes, LA

they have much in common and differ from

is a grammar of meanings, functions,

traditional grammar teaching in a number of

and form-function mapping.

significant ways.

• The aim of LA is to develop in the

Differences between language awareness learner an awareness of and sensitivity

and traditional grammar to form, and not just to learn a long list

Language awareness does not use the same of grammatical items. Learners have to

traditional techniques used to teach grammar explore structured input and develop an

that one finds in structural grammar books awareness of particular linguistic fea-

like Stannard Allen’s (1974) famous Living tures by performing certain operations.

English Structure, Thompson and Martinet’s According to Schmidt (1995), there can

(1980) A Practical English Grammar, or Grav- be learning without intention, but there

er’s (1986) Advanced English Practice. In addi- can be no learning without attention.

tion, the practice that LA supports is different • LA occurs by means of certain types of

in kind from the exercises in traditional gram- formal instruction or task-based learn-

mar books like Azar (1989), Murphy (1997), ing, where learners do grammar tasks

and Willis and Wright (1995). in groups. It can come in many differ-

Language awareness also contrasts sharply ent forms and vary greatly in degree of

with the Presentation-Practice-Production explicitness and elaboration. It is not

(PPP) instructional cycle, another traditional the same thing as practice. It is about

way of teaching grammar in the L2 classroom input processing, noticing certain pat-

where the main focus is on controlled practice terns or relationships, discovering rules,

in the form of drills and various contextualized and noticing the difference between

grammar exercises. The PPP cycle is based on one’s current interlanguage and the

a simplistic theory of language acquisition, target language system and as a result

namely “implanting through practice.” In subconsciously restructuring one’s still

contrast, the LA model is more concerned evolving grammar system. As Schmidt

with input processing and comprehension (1993, 4) says, noticing is “the necessary

than with practice with drills and repetition. and sufficient condition for the conver-

LA is different in that it involves learners, indi- sion of input into intake.”

vidually or in groups, in exploratory tasks, very

often on bits of language that need repair. • LA is multi-faceted. It goes beyond the

The differences between LA and tradi- raising of grammatical consciousness

tional grammar teaching may be summarized to include all linguistic components—

as follows: vocabulary, morphology, phonology,

and discourse. However, most of the

• LA is not a body of established facts published examples of LA relate to

about grammar, and it differs fun- grammatical and lexical problems, such

damentally from the repertoire of as exploring the grammatical devices

structures and functions found in an used to express the concept of futurity,

itemized syllabus. Several researchers, looking at the difference between the

notably Long (1991) and Spada (1997), standard passive (The book was lost by

regard this distinction as crucial. LA is Sally) and the “get” passive (I got lost),

14 2008 Number 1 | E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 14 12/19/07 10:02:07 AM

making sense of modal verbs, examin- effectively explore, internalize, and gain

ing collocation or redundancy, and greater understanding of the target lan-

other features of English. guage. The basic assumption here is

• LA is data driven. Learners are not told that all learners have to be actively

the rule, but are given a set of data from involved in discovering features of the

which they infer the rule or generaliza- language. They are not given the rule,

tion in their own way. They check their but rather work inductively from struc-

tentative rule against other sets of data tured input to arrive at their own

and then see if it still holds in a number understandings. It is a process-oriented

of contexts of use. Here again, by notic- approach, which includes steps of dis-

ing the gap between their production covery, investigation, and understand-

and the correct target form, learners ing, which contrasts markedly with the

may restructure or fine-tune their con- traditional product-oriented approach

clusion. Rules in English are seldom in which one is told the rules and has

clear-cut, and a lot of work needs to be to drill and memorize them, a method

done on the gray areas. found even in recent grammar books

for teaching purposes.

Certainly, the concept of LA and related

approaches have become a major new trend Integrating language awareness into

in second language learning. There is now task-based learning

extensive literature on the subject, including There are probably dozens of effective

excellent summaries in Doughty and Williams activities in the literature that teachers can

(1998), Ellis (2001), Carter (2003), Hinkel and use to facilitate LA in the classroom. These

Fotos (2002), and Bolitho et al. (2003). The activities enable the teacher to “problematize”

key concept of noticing is explained by Batstone instruction, and they allow learners to actively

(1996), and some ways to implement LA in engage in the learning process. For this reason,

the classroom are found in Hawkins (1984), they are referred to as “enabling tasks” (Bourke

James and Garrett (1992), Wright and Bolitho 2002). According to Estaire and Zanon (1994,

(1993), Wright (1994), and Ellis (2006). 15), “enabling tasks act as a support for com-

munication tasks. Their purpose is to provide

The rational for language awareness students with the necessary linguistic tools to

One way to think about language aware- carry out a communication task.” This view-

ness is that everyone is a learner, since even point ties LA to task-based learning, another

teachers have to continue to explore language major paradigm shift in the way second

systems—a lifelong process. It is therefore use- language is experienced in the classroom. In

ful to look at the following two complemen- Willis’ (1996, 101–116) task based learning

tary aspects of LA in the context of learning a model “language focus” is the last phase in the

second language. framework. Upon completing a communica-

tive/interactive task, students have the oppor-

1. The personal exploration of the L2 tunity to explore points of language arising

helps the learner find out how language out of the task cycle. The language focus may

works and thereby enriches and extends consist of analysis or practice activities. Analy-

one’s knowledge of the language. Here, sis consists of consciousness raising activities

one is talking about a focus on language in which students analyze texts, transcripts,

itself. Everyone has a subconscious and sets of examples in order to notice specific

knowledge of the language they use, language points, such as:

but not everyone has managed to make

that internalized language explicit, by 1. Semantic concepts related to themes,

noticing and reflecting on the linguistic notions, functions (e.g., Find and clas-

data all around them. sify all the phrases referring to time.)

2. The other aspect of language aware- 2. Words or parts of a word (e.g., When

ness is the applied perspective, which do we use the word any? What does it

for teachers means helping learners mean? Study the examples in the text.)

E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m | Number 1 2008 15

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 15 12/19/07 10:02:07 AM

3. Categories of meaning or use (e.g., The occurs; this can include observation of

word will has four categories of mean- syntactic patterning, judgments and

ing in the text. What are they? Give an discriminations, and the articulation

example of each category.) of rules.

Practice activities may consist of one or 3. The student checks that the rule holds

more of the following (Willis 1996, 110– against further data and, if not, revises

113): the rule.

4. The student uses the structure in a

1. Unpacking and repacking a sentence

short production task.

2. Repeating, reading, or completing

phrases Technique 1: Linguistic problem-solving

Any piece of language can be targeted

3. Making a concordance

for exploration. For instance, Hall and

4. Progressive deletion from board Foley (1990) present topics such as tense

5. Gapped transcript contrasts, modal verbs, conditionals, infini-

tive versus gerund, verb patterns, adjectives

6. Dictionary work and reporting back

and adverbs, prepositions, and articles and

7. Looking up a point of grammar in a determiners.

reference grammar and reporting back Analysis may take place at the input

8. Computer games stage or the output stage. The task is often

presented by means of “perceptual frames,”

9. Language games

i.e., a short dialogue, narrative, or expository

10. C-text restoration activity and follow- text. The “input frames” provide a meaning-

up discussion ful context to focus on the new language

item, and sufficient data to enable the learner

The idea behind LA is that learners them-

to make a tentative induction as to the rule

selves construct their own grammar from

or generalization. Progress along that route is

their own language experience, and thereby

speeded up by exposure to “enhanced input”

either consciously or subconsciously restruc-

and the application of cognitive strategies.

ture their emerging interlanguage. They need

Further frames/data are then presented and

access to negative evidence, which in LA is

provided by means of corrective feedback the initial hypothesis is either confirmed

from the teacher or by looking up the prob- or rejected. The problem-solving procedure

lem point in a comprehensible reference involves a simple recursion, comprising three

grammar or dictionary. moves:

Implementing language awareness 1. Read the next frame

techniques 2. Form a hypothesis

Many other techniques, in addition to 3. Test, and if necessary, revise your

the task-based ones mentioned above, can hypothesis

raise learners’ consciousness of the form and

function of targeted grammatical items. The The input frames are seeded with pertinent

techniques listed below may be classed as LA data and are carefully sequenced to address

and have been found to be especially useful, different aspects of the problem under study.

user-friendly, and effective. Where possible, For example, in presenting the article system

these techniques should be sequenced as in English, one might look at a series of binary

follows: contrasts:

1. The student is exposed to oral or writ- 1. count vs. mass nouns

ten structured input where the initial

2. a versus an

focus is on the meaning of the text.

2. The student notices the target struc- 3. the versus a / an

ture and the context in which it 4. article versus no article

16 2008 Number 1 | E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 16 12/19/07 10:02:08 AM

The a versus an problem might be pre- of fossilized error in a systematic manner

sented to a beginning class as follows: through language awareness activities.

Technique 3: Restoring C-texts

Problem: Why are some nouns pre- The use of C-texts for measuring general

ceded by a and others by an? language proficiency has by now become quite

Instructions: Read the passage below common. The standard C-text consists of four

and underline all nouns preceded by a or to six short texts which have been altered by

an. Enter the underlined nouns in the cor- deleting the second half of every second word

rect column. and replacing it with a blank. The task is to

restore the missing pieces by using a variety of

conscious strategies, such as contextual infer-

Passage (with solution): Molly is an encing and analogy, among others.

awful cat. She sleeps on a mat and never The advantages of C-texts are numerous,

catches a mouse. She eats five times a day. some of the main ones being the following:

She often sits in an armchair for an hour

• They prime learners to discuss points

or more without making a sound. Some

of grammar or lexis on which they

people say she’s a horrid cat, but I think

miscue, and thus remove some of the

she’s an old rascal.

roadblocks to correct usage.

• Working on a C-text is like doing a

a an puzzle—it is an enjoyable and challeng-

mat armchair ing activity. (Students generally respond

well to problem-solving tasks.)

mouse hour • C-texts can lead learners to become

day aware of target language forms.

• C-texts are easy to construct and they

sound can be calibrated quite precisely to

learners’ abilities.

This technique allows the learner to notice • Learners can self-correct the C-text and

syntactic patterning and make judgments and thus benefit from immediate feedback.

discriminations about a rule. In this case, the • C-texts sample a wide range of gram-

fact that not only the nouns but intervening matical categories.

adjectives take indefinite articles may help • C-texts are objective, easy to adminis-

the learner “notice” that the rule is based on ter, and score.

sound.

Technique 4: Cloze procedure

Technique 2: Error detection and correction The basic fixed-ratio Cloze procedure

Noticing is also a key process in analyzing involves the systematic deletion of words

output and is essential for error detection and from a text (such as every fifth word) for

correction. Making errors and having them students to fill in (Oller 1973). This creates

corrected is a normal part of learning. We an awareness of word order, collocation, and

are told “there is no learning without making dependency relations between elements. It

errors.” However, it is pointless to tell students is a problem-solving exercise in which the

to edit their work if they do not know how to learner has to exploit linguistic clues on many

edit. In many cases, they do not know the fronts, not only in the linguistic context, but

rules; if they did, there would not be errors. also in the wider context of situation. Impor-

Student errors are a very good source of reme- tantly, the Cloze can be used to focus atten-

dial work, which may focus on one particular tion on specific language items if selected

problem, or on a number of related problems, function words (such as pronouns, articles,

such as looking at the form and function of and conjunctions) or inflectional morphemes

narrative tenses in a piece of writing. (such as the past tense marker -ed or the pro-

It is no easy task to eradicate persistent gressive tense marker -ing) are deleted. The

grave errors which have fossilized over many Cloze procedure is often used for language

years. It may be necessary to target each case testing; as such, it is not without its critics,

E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m | Number 1 2008 17

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 17 12/19/07 10:02:08 AM

even though, as Barnwell (1987) notes, work Technique 7: Sentence combining

is still in progress on Cloze variations. As a The issue of sentence combining as a teach-

result, some language teachers prefer to use ing tool is discussed by James (1994) and Zamel

the C-text for language testing and the Cloze (1980). Sentence combining has been and still

text for language teaching (Khoo 2002). is extensively used as a pre-writing task. It is

Whatever its role as a testing tool, the Cloze a very effective way of raising students’ con-

procedure, and especially the selective Cloze sciousness of cohesion. Some learners tend to

variation, seems to possess certain merits as a write a string of loosely-connected sentences.

teaching tool and can help learners consoli- For instance, in lower primary grades, one

date and restructure their grammar. often finds a lot of redundancy in composition

writing, as in the following example:

Technique 5: Paraphrase

I have a cat. My cat is black. She has white

Paraphrasing is a very powerful pedagogi- paws. My cat has green eyes.

cal tool for syntactic and lexical exploitation.

Moreover, it can be employed at different These four sentences can be more eco-

levels of L2 proficiency. For example, hav- nomically expressed in a single sentence:

ing analyzed the form and function of the I have a black cat with white paws and

present perfect tense in English, one might green eyes.

devise various stimulus sentences related to Sentence combining helps students to

a current task to elicit this tense, as in this become aware of the structural changes that

example: come into play when two or more simple

Instruction: Rewrite each sentence so that sentences are combined. It covers an enormous

it means the same, or nearly the same, as area of English grammar, ranging from coordi-

the given sentence. nation to subordination and the various types of

sentence connectives that signal a wide range of

Tom no longer lives in Kuching. semantic relationships. One LA activity in this

area is known as “packing” and “unpacking”

He________________ [Answer: He has sentences, which is combining two or more

left Kuching.] sentences into one, or extracting the embedded

There isn’t any food left. propositions from a complex sentence.

Abu________________ [Answer: Abu Technique 8: Grammaring

has eaten it all.] Teachers teach grammar, but learners need

grammaring, which is the ability to access and

Technique 6: Propositional cluster use grammatical devices to make meaning.

Rutherford (1987, 167) defines a “proposi- Thornbury (2001, 1) makes a distinction

tional cluster” as a skeletal sentence consisting between making an omelette (or “omelet-

of an unmarked verb and its associated noun- ting”) and an omelette. Likewise, he distin-

phrases. The learner is given the discourse set- guishes between doing grammar (or “gram-

ting, and the task is to arrange the cluster into maring”) and grammar. The same idea is

a well-formed sentence and to do so within found in Rutherford (1987), but he refers to

the context indicated. For example: the process of exploiting grammatical devices

as “grammaticization.”

Round the corner came a boy. In order to demonstrate the various ways

ride – he (boy) – bicycle in which a single concept is expressed, learners

may be given a set of propositions and asked

The most natural realization of this cluster

to indicate the many ways in which they can

would be:

be “grammared.” For instance, in English the

He was riding a bicycle. language function “contrast” is expressed in a

The learner has to figure out which noun number of ways.

phrase is selected as grammatical subject, the A [but] B. [simple conjunction]

form it takes, and the most likely type of ver- A; [however,] B. [sentence connector]

bal form and complementation. A [whereas] B. [subordinator]

18 2008 Number 1 | E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 18 12/19/07 10:02:08 AM

The focus here is to build procedural grammar and vocabulary) but also raises the

knowledge by sensitizing learners to the forms learner’s consciousness of textual organization.

available and enabling them to select the most

appropriate form for a particular context Technique 10: Language games

of use. Thus, in casual conversation the but All language learners enjoy an element of

option is most likely, while in formal writing fun and inventiveness, and language games

the whereas option is more appropriate. (The have long been part and parcel of second

range of options available would not be given language teaching and learning (Rinvolucri

as above, but would be inferred from a text or 1984; Rinvolucri and Davis 1995). One can

several texts.) easily devise game-like activities to elicit and

Grammaring tasks require learners to make use a particular pattern. For instance, the pair-

decisions as to which grammatical devices are work games such Describe and Draw, Spot the

most appropriate to express their intended Difference, and Board Rush are popular with

meaning. They have to ask themselves ques- young learners, while older learners seem to

tions such as: enjoy word games, puzzles, and problem-solv-

ing scenarios. The same kind of game can be

• “Shall I use the active or passive?” used in different ways to focus on language

• “Shall I use any narrative tenses, and if items, or real interaction. For example, an

so, which one, and why?” information-gap activity about zoo animals

• “Shall I use coordination or might focus on the present progressive (e.g.,

subordination?” Abu is feeding the zebra), while a communica-

Thornbury (2001, 81–99) offers a selec- tive version might require each participant to

tion of photocopiable grammaring materials. talk freely about the animals. One can find

Many of these are lexical clusters to which many stimulating games that focus on the

grammar has to be added. For example: language system, for instance, the discovery

boy blue suit Carlos activities in Hall and Shepheard’s (1991) The

Anti-grammar Grammar Book.

One possible way of grammaring this set of Many of the techniques outlined above

lexical items is as follows: have been around for the past 10 to 20 years.

The boy in the blue suit is Carlos. Some of them focus on input processing,

while others focus on output processing. Lan-

Technique 9: Dictogloss guage awareness is, therefore, any technique

Dictogloss or Grammar Dictation is a tech- or combination of techniques that enable

nique that involves the teacher and students in learners to understand how a piece of lan-

communicative interaction, text reconstruc- guage works. Far from being a new concept,

tion, and error analysis. There are four stages it is often a matter of putting old wine into

in the procedure: new bottles.

1. Preparation—the learner finds out Conclusion

about the topic of the text and is pre- One of the great challenges for second

pared for some of the vocabulary. language teachers has been the implementa-

2. Dictation—the learner hears the text tion of procedures that help learners process

and takes fragmentary notes. The text comprehensible input while at the same time

is dictated at a speed which allows only giving them opportunities for language aware-

key words to be noted. ness. In other words, effective second language

3. Reconstruction—students in pairs or teaching requires input processing (acquisi-

small groups pool their resources to tion) combined with focus on form (learn-

reconstruct their own version of the ing). It matters not whether we call the new

original text. process-oriented approach language aware-

4. Analysis and correction—learners ana- ness, or consciousness-raising, or linguistic

lyze and correct their texts. problem-solving. Language is no longer seen

Dictogloss is a fairly severe test of grammar- as a fixed inventory of structures prescribed

ing. It involves all the four skills and develops by an itemized syllabus that is presented in

awareness of language items (in particular an atomistic and linear fashion. Rather, it is

E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m | Number 1 2008 19

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 19 12/19/07 10:02:09 AM

seen as a dynamic process in which learners —–. 2002. Learning grammar by means of “enabling

themselves are actively involved. According to tasks.” Studies in Education 7:3–13.

Carter, R. 2003. Key concepts in ELT: Language

Nunan (1998, 140), an “organic” approach to

awareness. ELT Journal 57 (1): 64–65.

language teaching: Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax.

• offers a set of choices Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

—–. 1986. Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin,

• provides opportunities for learners to and use. New York: Praeger.

explore grammatical and discoursal Doughty, C., and J. Williams. 1998. Focus on form

relationships in authentic data in classroom second language acquisition. Cam-

• makes the form/function relationships bridge: Cambridge University Press.

transparent Ellis, R. 1995. Interpretation tasks for grammar

teaching. TESOL Quarterly 20 (1): 87–105.

• encourages learners to become active —–. 2001. Investigating form-focused instruction.

explorers of language Language Learning 51: Suppl. no. 1, 1–46.

• encourages learners to explore relation- —–. 2006. Current issues in the teaching of gram-

ships between grammar and discourse mar: An SLA perspective. TESOL Quarterly 40

(1): 83–107.

In summary, then, language awareness has Estaire, S., and J. Zanon. 1994. Planning classwork:

to do with the raising of learners’ awareness A task-based approach. Oxford: Heinemann.

of features of the target language. Its point Fotos, S. 1993. Consciousness raising and notic-

ing through focus on form: Grammar task

of departure is input processing, exploring performance versus formal instruction. Applied

examples of language in context, noticing Linguistics 14 (4): 385–407.

salient points and patterns, inferring a rule Graver, B. D. 1986. Advanced English practice 3rd

and testing it against further data. But that is ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

only half the story. It is equally important to Hall, D., and M. Foley. 1990. Survival lessons:

Resource material for teachers. Walton-on-

allow and require learners to outperform their Thames, UK: Nelson.

newly acquired grammar, or as Nunan (1998, Hall, N., and J. Shepheard. 1991. The anti-gram-

108) says, “for learners to press their gram- mar grammar book: Discovery activities for gram-

matical resources into communicative use.” mar teaching. London: Longman.

Research on LA is still in its infancy, and Hawkins, E. 1984. Awareness of language: An intro-

duction. Cambridge: Cambridge University

it is probably too soon to say which forms Press.

may be most effective with different groups Hinkel, E., and S. Fotos, eds. 2002. New perspec-

of learners. However, we now have a large tives on grammar teaching in second language

body of empirical evidence supporting the classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

inductive problem-solving route to linguistic Associates.

James, C., and P. Garrett, eds. 1992. Language

knowledge. Hence, the teacher’s role is no

awareness in the classroom. London: Longman.

longer that of “great guru”—or “all knowing James, C. 1994. Sentence combining revisited.

one”—but that of the facilitator of learning. Paper presented at the English Department,

University of Brunei Darussalam, Gadong.

References —–. 1998. Errors in language learning and use:

Azar, B. 1989. Understanding and using English Exploring error analysis. London: Longman.

grammar. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pren- Khoo, S. C. 2002. Use of C-texts to facilitate con-

tice Hall. sciousness-raising outside the English classroom

Barnwell, D. 1987. The cloze procedure and varia- among in-service teachers. Studies in Education

tions on it: A selective review of the literature. 7: 53–68.

Teangeolas 22: 9–12. Krashen, S. 1981 Second language acquisition and

Batstone, R. 1996. Key concepts in ELT: Noticing. second language learning. Oxford: Pergamon.

ELT Journal 50 (3): 273. Long, M. H. 1983. Does second language instruc-

Bolitho, R., R. Carter, R. Hughes, R. Ivanic, H. tion make a difference? A review of research.

Masuhara, and B. Tomlinson. 2003. Ten ques- TESOL Quarterly 17 (3): 359–82.

tions about language awareness. ELT Journal 57 —–. 1991. Focus on form: A design feature in

(3): 251–59. language teaching methodology. In Foreign lan-

Bourke, J. M. 1989. The grammar gap. English guage research in cross-cultural perspective, ed.

Teaching Forum 27 (3): 20–23. K. de Bot, R. B. Ginsberg, and C. Kramsch,

—–. 1992. The case for problem solving in sec- 39–52. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

ond language learning. CLCS Occasional Murphy, R. 1997. Essential grammar in use: A self-

Paper No. 33. Washington, DC: Education study reference and practice book for elementary

Resources Information Center. ERIC Database students of English. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cam-

ED353822. bridge University Press.

20 2008 Number 1 | E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 20 12/19/07 10:02:09 AM

Nunan, D. 1998. Teaching grammar in context. and laboratory research. Language Teaching 30

ELT Journal 52 (2): 101–109. (2): 73–87.

Oller, J. W. 1973. Cloze tests of second language Stannard Allen, W. 1974. Living English structure.

proficiency and what they measure. Language London: Longman.

Learning 23: 105–18. Thornbury, S. 1999. How to teach grammar. Lon-

Prabhu, N. S. 1987. Second language pedagogy. don: Longman.

Oxford: Oxford University Press. —–. 2001. Uncovering Grammar. Oxford: Macmil-

Rinvolucri, M. 1984. Grammar games: Cognitive, lan Heinemann.

affective and drama activities for EFL students. Thompson, A. J., and A.V. Martinet. 1980. A Prac-

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. tical English Grammar. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford

Rinvolucri, M., and P. Davis. 1995. More grammar University Press.

games: Cognitive, affective and movement activi- Willis, J. 1996. A framework for task-based learning.

ties for EFL students. Cambridge: Cambridge London: Longman.

University Press. Willis, D., and J. Wright. 1995. Collins Cobuild

Rutherford, W. E. 1987. Second language grammar: basic grammar. London: HarperCollins.

Learning and teaching. London: Longman. Wright, T. 1994. Investigating English. London:

Schmidt, R. 1990. The role of consciousness in Edward Arnold.

second language learning. Applied Linguistics 11 Wright, T., and R. Bolitho. 1993. Language aware-

(2): 129–58. ness: A missing link in language teacher educa-

—–. 1993. Awareness and second language acquisi- tion? ELT Journal 47 (4): 292–304.

tion. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 13: Zamel, V. 1980. Re-evaluating sentence-combining

206–26. practice. TESOL Quarterly 14 (1): 81–90.

—–. 1995. Consciousness and foreign language

learning: A tutorial on the role of attention and

awareness in learning. In Attention and aware-

ness in foreign language learning, ed. R. Schmidt, James M. Bourke has worked in Africa, the

1–64. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Over the

Sharwood Smith, M. 1993. Input enhancement

in instructed SLA: Theoretical bases. Studies in years he has been involved in teacher

Second Language Acquisition 15: 165–79. education (TESL); he is currently a senior

Spada, N. 1997. Form-focused instruction and sec- lecturer in language education at the

ond language acquisition: A review of classroom University of Brunei.

12. Harlem

11. Brooklyn Bridge

10. Empire State Building

9. Carnegie Hall

8. Central Park

7. Guggenheim Museum

6. Statue of Liberty

5. United Nations

Answers to The Lighter Side

4. Erie Canal

3. Greenwich Village

New York City Word Search

2. Hudson River

1. Broadway

+ + + + + + + + + + + C + + + + + + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + + + A + + + + + + + + + + +

B + + + + + + + + R + + + + + + + + + + + +

+ R + G + + + + N + + + + + + + + + + + + +

+ + O + N + + E + + + + + + + + H A R L E M

12. Harlem + + + O + I G S T A T U E O F L I B E R T Y

11. Brooklyn Bridge + E + + K I D + + + + + + + + + + + + + + M

+ G + + E L + L + + + + + + + + + + + + U +

10. Empire State Building + A + H + + Y + I + + + + + + + + + + E + +

9. Carnegie Hall + L A + + U + N + U + R E V I R N O S D U H

+ L + + + N + + B + B + + + + + + U + + + +

8. Central Park L I + + + I + K + R + E + + + + M + + + + +

7. Guggenheim Museum + V + + + T + + R + I + T + + M + + + + + +

+ H + + L E + + + A + D + A I + + + + + + +

6. Statue of Liberty + C + + A D + + + + P + G E T + + + + Y + +

5. United Nations + I + + N N + + + + + L H E + S + + A + + +

+ W + + A A + + + + + N A + + + E W + + + +

4. Erie Canal + N + + C T + + + + E + + R + + D R + + + +

3. Greenwich Village + E + + E I + + + G + + + + T A + + I + + +

+ E + + I O + + G + + + + + O N + + + P + +

2. Hudson River + R + + R N + U + + + + + R + + E + + + M +

1. Broadway + G + + E S G + + + + + B + + + + C + + + E

New York City Word Search

Answers to The Lighter Side

E n g l i s h T e a c h i n g F o r u m | Number 1 2008 21

08-20001 ETF_12_21.indd 21 12/19/07 10:02:10 AM

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Summit 2Dokument150 SeitenSummit 2Carlos Sanchez Becerril83% (18)

- CPIDokument51 SeitenCPISalim RezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roger Mcgough - Poems - : Classic Poetry SeriesDokument22 SeitenRoger Mcgough - Poems - : Classic Poetry SeriesJosé Carlos Faustino CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Paper LISTENING KETDokument15 SeitenSample Paper LISTENING KETZULHILMI MAT ZAIN50% (6)

- DELTA Language Skills Assignment SpeakingDokument23 SeitenDELTA Language Skills Assignment Speakingsandrasandia100% (3)

- Dr. Mercola Healthy Recipes WebDokument307 SeitenDr. Mercola Healthy Recipes WebAnonymous LhmiGjO100% (2)

- Guitar Sage Ebook PDFDokument32 SeitenGuitar Sage Ebook PDFzee_iit0% (1)

- Kindergarten curriculum guide for 5-year-oldsDokument36 SeitenKindergarten curriculum guide for 5-year-oldsMark Quirico100% (1)

- Lexical NotebooksDokument4 SeitenLexical Notebookstony_stevens47478Noch keine Bewertungen

- Four Strands Framework for Language LearningDokument13 SeitenFour Strands Framework for Language LearningDelfa OtrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Author Insights Paul Davis Hania KryszewskaDokument2 SeitenAuthor Insights Paul Davis Hania KryszewskaEmily JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Richards (1990) Design Materials For Listening PDFDokument18 SeitenRichards (1990) Design Materials For Listening PDFnenoula100% (1)

- Scaffolding WalquiDokument22 SeitenScaffolding WalquiAzalia Delgado VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ELT J 1986 MacWilliam 131 5Dokument5 SeitenELT J 1986 MacWilliam 131 5Olga IchshenkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Foundations of Accent and Intelligibility in Pronunciation ResearchDokument17 SeitenThe Foundations of Accent and Intelligibility in Pronunciation ResearchClaudia M. WinfieldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pronunciation teaching methods and techniquesDokument35 SeitenPronunciation teaching methods and techniquesMiriam BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Language Acquisition EssayDokument7 SeitenSecond Language Acquisition EssayManuela MihelićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anyone For Quircling?Dokument3 SeitenAnyone For Quircling?Pete ClementsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loop InputDokument4 SeitenLoop InputAndy Quick100% (3)

- Task-Based Language Education:from Theory To Practice and Back AgainDokument31 SeitenTask-Based Language Education:from Theory To Practice and Back AgainTrần Thanh Linh100% (1)

- Teaching IntonationDokument16 SeitenTeaching IntonationSerene Lai Woon MuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essays Into Literacy - Frank SmithDokument138 SeitenEssays Into Literacy - Frank SmithHuey RisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vocabulary Learning at Primary School: A Comparison of EFL and CLILDokument14 SeitenVocabulary Learning at Primary School: A Comparison of EFL and CLILSara CancelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PronunciationDokument6 SeitenPronunciationkirsy_perez100% (1)

- Incorporating Culture Into Listening Comprehension Through Presentation of MoviesDokument11 SeitenIncorporating Culture Into Listening Comprehension Through Presentation of MoviesPaksiJatiPetroleumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fluency Vs AccuracyDokument6 SeitenFluency Vs AccuracyAnonymous VkwVpe9AOkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Improve Your Writing SkillsDokument8 SeitenImprove Your Writing SkillsLusya LiannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lexical Notebooks or Vocabulary CardsDokument8 SeitenLexical Notebooks or Vocabulary Cardstony_stevens47478Noch keine Bewertungen

- CLIL Through EnglishDokument146 SeitenCLIL Through EnglishLucas FernandesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allwright 1983Dokument195 SeitenAllwright 1983academiadeojosazulesNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Framework To Task-Based LearningDokument11 SeitenA Framework To Task-Based LearningNatalia Narváez0% (1)

- Spoken Corpora PDFDokument25 SeitenSpoken Corpora PDFGeorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shifting The Focus From Forms To Form in The EFL ClassroomDokument7 SeitenShifting The Focus From Forms To Form in The EFL ClassroomNguyên KanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language JournalDokument12 SeitenLanguage JournalNadia Ali LWNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literacy Instruction Young Efl LearnersDokument48 SeitenLiteracy Instruction Young Efl LearnersPIRULETA100% (1)

- Collocations in English - Turkish PDFDokument5 SeitenCollocations in English - Turkish PDFColin LewisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feb 2018 Interaction Online ExtractDokument233 SeitenFeb 2018 Interaction Online ExtractKateryna Novodvorska100% (1)

- Teaching PronunciationDokument6 SeitenTeaching Pronunciationapi-268185812100% (1)

- Appreciating & Surviving Flipped Classrooms: Dr. Melodie RosenfeldDokument33 SeitenAppreciating & Surviving Flipped Classrooms: Dr. Melodie RosenfeldMohamad TahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Lexical PhrasesDokument31 SeitenTeaching Lexical PhrasesGallagher RoisinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Listening)Dokument11 SeitenTeaching Listening)sivaganesh_70% (1)

- The Coursebook As Trainer Et Prof 1Dokument4 SeitenThe Coursebook As Trainer Et Prof 1api-402780610Noch keine Bewertungen

- Overview of First Language Acquisition and Children's Early Grammatical DevelopmentDokument8 SeitenOverview of First Language Acquisition and Children's Early Grammatical DevelopmentKamoKamoNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Apply The Audio Lingual Method in The ClassDokument3 SeitenHow To Apply The Audio Lingual Method in The ClassYeyen Sentiani DamanikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authenticity BreenDokument6 SeitenAuthenticity Breenirony_of_fate100% (1)

- Ellis - Emergentism, Connectionism and Language LearningDokument34 SeitenEllis - Emergentism, Connectionism and Language LearningjairomouraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spada Lightbown2008Form Focused InstructionDokument27 SeitenSpada Lightbown2008Form Focused InstructionImelda Brady100% (1)

- Almahrooqi R Coombe C Almaamari F Thakur V Eds Revisiting EfDokument350 SeitenAlmahrooqi R Coombe C Almaamari F Thakur V Eds Revisiting EfkienNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1997 Celce Murcia Dornyei Thurrell TQDokument12 Seiten1997 Celce Murcia Dornyei Thurrell TQsnejana19870% (1)

- Helping Low-level Learners with Connected SpeechDokument12 SeitenHelping Low-level Learners with Connected SpeechresearchdomainNoch keine Bewertungen

- SWAIN LAPKIN 2002 Talking It ThroughDokument20 SeitenSWAIN LAPKIN 2002 Talking It ThroughMayara Cordeiro100% (1)

- Learning To Learn English A Course in LeDokument8 SeitenLearning To Learn English A Course in LeEi TunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waring (2008)Dokument18 SeitenWaring (2008)Alassfar AbdelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peer Taught Phrasal Verbs LessonDokument3 SeitenPeer Taught Phrasal Verbs Lessonpupila31Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Lexical PhrasesDokument4 SeitenTeaching Lexical PhrasesRonaldi OzanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zimmerman C and Schmitt N (2005) Lexical Questions To Guide The Teaching and Learning of Words Catesol Journal 17 1 1 7 PDFDokument7 SeitenZimmerman C and Schmitt N (2005) Lexical Questions To Guide The Teaching and Learning of Words Catesol Journal 17 1 1 7 PDFcommwengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Video Applications in English Language Teaching v3 PDFDokument125 SeitenVideo Applications in English Language Teaching v3 PDFenitu_1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Text and Task AuthenticityDokument7 SeitenText and Task AuthenticityjuliaayscoughNoch keine Bewertungen

- N.S Prabhu InterviewDokument83 SeitenN.S Prabhu InterviewSusarla SuryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Z413 English Development BookDokument380 SeitenZ413 English Development BookSilva RanxhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines On CLIL MethodologyDokument18 SeitenGuidelines On CLIL MethodologyMariliaIoannouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communication Skills in English: Suggested Reading for the Media, Schools and CollegesVon EverandCommunication Skills in English: Suggested Reading for the Media, Schools and CollegesNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study Guide for Heinrich Boll's "Christmas Not Just Once a Year"Von EverandA Study Guide for Heinrich Boll's "Christmas Not Just Once a Year"Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Grammar TechniquesDokument17 SeitenTeaching Grammar Techniqueslenio pauloNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Morphosyntax?: The Relationship Between Age and Second Language Productive AbilityDokument8 SeitenWhat Is Morphosyntax?: The Relationship Between Age and Second Language Productive AbilityAlvin Rañosa LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan DietsDokument7 SeitenHealth Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Dietsekhar17Noch keine Bewertungen

- Productive SkillsDokument8 SeitenProductive SkillssandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vegetarian Diets in Children and AdolescentsDokument6 SeitenVegetarian Diets in Children and AdolescentsPedro SimoesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deficiencia B12Dokument16 SeitenDeficiencia B12sandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Receptive SkillsDokument2 SeitenReceptive SkillssandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deficiencia B12Dokument16 SeitenDeficiencia B12sandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efectos de Una Dieta Vegana Baja en GrasaDokument7 SeitenEfectos de Una Dieta Vegana Baja en GrasasandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LeafyLegends TessMasters PDFDokument16 SeitenLeafyLegends TessMasters PDFsandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vegetarianismo y AntecedentesDokument7 SeitenVegetarianismo y AntecedentessandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action Plan For Teaching EngDokument44 SeitenAction Plan For Teaching EngMatt Drew100% (39)

- Efectos de Una Dieta Vegana Baja en GrasaDokument7 SeitenEfectos de Una Dieta Vegana Baja en GrasasandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bulats Productive SkillsDokument1 SeiteBulats Productive SkillssandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Articles Noticing&Guideddiscovery&MultiplechoiceDokument3 Seiten1 Articles Noticing&Guideddiscovery&MultiplechoicesandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ReadingDokument5 SeitenReadingsandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dictionaries For Learners of EnglishDokument44 SeitenDictionaries For Learners of EnglishsandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service Encounter Role PlaysDokument5 SeitenService Encounter Role PlayssandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Sentence Stress 22Dokument30 SeitenTeaching Sentence Stress 22Benjamin Ramsden Facer100% (1)

- BR J Philos Sci 2012 Wagner 547 75Dokument29 SeitenBR J Philos Sci 2012 Wagner 547 75sandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Lesson PlanningDokument6 SeitenAdvanced Lesson PlanningsandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Total Physical Response (TPR) A Curriculum For AdultsDokument28 SeitenTotal Physical Response (TPR) A Curriculum For AdultsanggasubagjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 81 BrainDokument2 Seiten81 BrainsandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building - Skills.for - The.toefl - Ibt Beginning - Reading Chapter.2Dokument63 SeitenBuilding - Skills.for - The.toefl - Ibt Beginning - Reading Chapter.2sandrasandia100% (1)

- Building - Skills.for - The.toefl - Ibt Beginning - Reading Chapter.1Dokument52 SeitenBuilding - Skills.for - The.toefl - Ibt Beginning - Reading Chapter.1Kiyo Kyle Kojima100% (1)

- Teaching English in Mixed Ability ClassroomsDokument35 SeitenTeaching English in Mixed Ability ClassroomssandrasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jocuri EnergizerDokument24 SeitenJocuri Energizerbogdan_2007100% (1)

- 12.curriculum As A ProcessDokument20 Seiten12.curriculum As A ProcessDennis Millares YapeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aims of Education Explored in 40 CharactersDokument2 SeitenAims of Education Explored in 40 Characterssidma70Noch keine Bewertungen

- GEAR UP 1 PagerDokument1 SeiteGEAR UP 1 Pagerparkerpond100% (2)

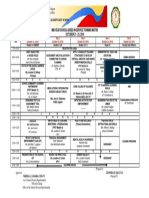

- Mid Year Inset 2019 2020 PDFDokument1 SeiteMid Year Inset 2019 2020 PDFLeonora DalluayNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Level 1 - Section A Teacher NotesDokument5 SeitenEnglish Level 1 - Section A Teacher NotesrsasamoahNoch keine Bewertungen

- English RPH Week 12 WedDokument4 SeitenEnglish RPH Week 12 WedfaizsrbnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Past QuizDokument3 SeitenPast QuizKone BlueNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR Diana M Burton - DR Steve Bartlett-Practitioner Research For Teachers-Sage Publications LTD (2004) PDFDokument209 SeitenDR Diana M Burton - DR Steve Bartlett-Practitioner Research For Teachers-Sage Publications LTD (2004) PDFfaheem ur rehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Outcome 5Dokument3 SeitenLearning Outcome 5api-346908515Noch keine Bewertungen

- 55 Minute Lesson PlanDokument8 Seiten55 Minute Lesson Planapi-295491619Noch keine Bewertungen

- LP PermutationDokument7 SeitenLP PermutationAlexis Jon Manligro NaingueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applied Strategic Thinking Brochure PDFDokument6 SeitenApplied Strategic Thinking Brochure PDFJosh NuttallNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLL Grade 11Dokument4 SeitenDLL Grade 11michael segundoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Is A Two-Way ProcessDokument5 SeitenTeaching Is A Two-Way ProcessHemarani MunisamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ict Lesson Plan 1Dokument3 SeitenIct Lesson Plan 1api-279341772Noch keine Bewertungen

- Project 5 Lesson PlanDokument7 SeitenProject 5 Lesson Planapi-341420321Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week 7 - Business FinanceDokument3 SeitenWeek 7 - Business FinanceAries Gonzales CaraganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 1 - The Role of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Human Resources DevelopmentDokument16 SeitenArticle 1 - The Role of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Human Resources DevelopmentYaacub Azhari SafariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Predication in English GrammarDokument17 SeitenTypes of Predication in English GrammarAlexandra Pity100% (1)

- Ahmadi - Presence in Teaching Awakening Body WisdomDokument253 SeitenAhmadi - Presence in Teaching Awakening Body WisdomMichaelFrelsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qce Faqs: What Is The Queensland Certificate of Education (QCE) ?Dokument2 SeitenQce Faqs: What Is The Queensland Certificate of Education (QCE) ?S RiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dream Keepers PaperDokument6 SeitenDream Keepers Paperapi-457866839Noch keine Bewertungen

- Deped School Calendar For School Year 2018-2019Dokument17 SeitenDeped School Calendar For School Year 2018-2019Alicia NhsNoch keine Bewertungen

- A National Curriculum Framework For All - 2012Dokument96 SeitenA National Curriculum Framework For All - 2012Hania KhaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Euclidean GeometryDokument405 SeitenEuclidean Geometryec gk100% (30)

- Eng 100bc Syllabus Sp14Dokument7 SeitenEng 100bc Syllabus Sp14jeanninestankoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit Plan Template SooonDokument4 SeitenUnit Plan Template Sooonapi-360229336Noch keine Bewertungen