Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Improving Elementary Students' Writing Skills Through Sensorimotor Intervention

Hochgeladen von

Lena CoradinhoOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Improving Elementary Students' Writing Skills Through Sensorimotor Intervention

Hochgeladen von

Lena CoradinhoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A Sensorimotor he delayed development of fine moror skills in

young children is a frequent cause of referral to

Program for Improving school-based occupational therapists. Develop

mental delay in kindergarten and first-grade children

\flriting Readiness Skills often manifests itself as incomplete mastery of the

readiness skills needed to print. Upon meeting a child

in Elementary-Age referred for treatment, the therapist determines if

there is a sensorimotor cause for the developmental

Children delay and, if so, provides direct intervention or con-

sultation services to remediate the problem.

Literature Review

Carolyn E. Oliver

Delay in writing readiness skills has been addressed

by several aurhors. Ajuriaguerra and Auzjas (1975)

Key rVords: gross and fine motor skills o stated that the motor aspect of writing starts with

handwriting . visual perception scribbling. Over time, the scribbling becomes inten-

tional. Eventually, the child learns to combine ele_

mentary design patterns into precise shapes. Beery

(1982) suggested that the masrery of the first nine

Tbis article discusses a writing readiness program

used witb tbree groups of cbildren aged i to 7 years. figures in his Developmental Test of Visual-Motor In-

Tbe program combines occupational tberapy treat- tegration is essential for learning to print. This test

ment with a supplementary program implemented was designed to assess the perceptual-motor develop-

by scbool personnel or parents. Tbe Deublopmental ment of children aged 3 to 14 years. The first nine

Test of Visual-Motor Integration-Reuised (Beery, figures in the assessment are (a) avertical line, (b) a

1982) was used to measure tbe deueloDmental leuel horizontal line, (c) a circle, (d) a crossed t, (e) a

of tbe cbildren's writing readiness skiils before and right-to-left diagonal, (f) a left to right diagonal, (g)

after treatment. group of cbitdren witb a signif- an x, (h) a square, and (i) a triangle. In anorher study,

-Tbe

cant uerb.tl performance Ie discrepancy (> 15 Nihei (1983) looked ar rhe progressive steps in the

points) sbouted a 17-montb growtb in readiness

drawing and handwriting of Japanese preschoolers.

skills witbin 1 year. Tbe group of cbit,iren with men-

tal retardation (IQ < BO) sbou.ed a significant sex His study lends support to the developmental trend

gfeq' fne boys sbowed more gains tban-tbe girls. that underlies the elementary drawings in the Devel-

Implications of tbese fndings are discussed. opmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration. Alston and

Taylor (1987) used a developmental model to exam-

ine handwriting and emphasized the importance of

the mastery of writing readiness skills before letter

formation is attempted.

The perceptual-motor development necessary for

the mastery of writing is fairly complex. perceptual_

motor skills can be thought of as a composite of per_

ceptual, conceptual, and motor processes or any com-

bination of these three processes (Mattison, McIntyre,

Brown, & Murray, 1986).Ir is commonly believed that

children with learning or neurological disabilities

often have an irregular academic readiness profile

with a delay of one or more of the perceptual-motor

skill componenrs. Marrison et al. (f 9g6) analyzedthe

visuomotor problems of children with learning dis_

abilities and found that they had significantly more

Carolyn E. Oliver, MA, orR/l, at the time of this stucly, was

trouble than normal children with design-copy tasks

an Occupational Therapist at the Grant Vood Area Educa_ with simultaneous visuomotor components. They

tion Agency, Cedar Rapids, Iowa. She is currently an Oc_ concluded that a "cross-modal" or intersensory inte-

cupational Therapy Consultant in private practice. (Mail_ gration function was defective. Other authors found

ing address: 3920 Bruce Road, Marion ,Iowa 52302) similar results, thus indicating that the weakest skill in

the total composite is the motor coordination compo-

Tbis article uas accepted for publication April 26, 1989.

nent. Lewis and Lewis (1965) analyzed the kincls of

Tbe American Journal of Occupational Tberapy

111

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 02/02/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

errors first-grade children made while forming manu- Pilot Project for \friting Readiness Skills

script letters. The three most common s11s1s-i1661-

Participants

rect size, incorrect relationship of parts, and incorrect

placement relative to size-were related to lack of The pilot project involved three groups of children.

motor control. Examining the printing errors made by Group 1 consisted of tZ children (9 boys and 3 girls)

kindergarten students copying letters, Simner (1982) of normal intelligence (mean lQ: 94), as defined by

found more form errors. that is, more motor coordina- a full scale IQ greater than 80 and a performance IQ

tion errors, than reversals. greater than 80 on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for

Training directed at aty one of the perceptual- Children-Revised (Wechsler, 1974). All of these chil-

motor skill components tends to enhance the overall dren were in regular education classes. One child in

performance. Strayer and Ames (7972) found that the this group was black and the other 11 children were

ability to copy designs improved after a brief period of white, as were all of the other children included in the

visual-perceptual training that emphasized the orien- project. The mean age of this group was 72 months.

tation of figures. Jennings (1974) showed a positive Group 2 consisted of 6 children (4 boys and 2

and significant relationship between the ability to ma- girls), all of whom had a significant disparity between

nipulate objects and the ability to copy designs. Laszlo verbal IQ and performance IQ (>15 points) on the

and Bairsrow (t983, 1984) found long-term benefits 'Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised.

after using a kinesthetic and sensitivity training pro- The group mean IQ was 77, but their average verbal

gram with 7- and S-year-old children. They recom- IQ was 86 and their average performance IQ was 71.

mended activities to generate kinesthetic awareness, At the time of the study, 2 of these children were in

such as large arm movements at the blackboard or regular education classes with no special education

easel. Stott, Henderson, and Moyes (7981), in their support besides occupational therapy, 3 children

remedial handwriting program, recommended the were in a regular class with additional time in a class

development of a motor schema. They emphasized for children with learning disabilities, and 1 child was

large movement patterns along with a smooth, fluid in a class for children with educable mental retarda-

motion. Furner (1957) developed a classroom tion. The mean age of this group was 67 months.

handwriting program that stressed verbalization and Group 3 consisted of 6 children (2 boys and 4

perceptual processes. She found that if faulty habits girls). Five of these children were in special educa-

were allowed to develop, good patterns would then tion classes. The only child in regular education had a

be harder to establish. She emphasized the need supportive home environment and was labeled an

for handwriting programs with perceptual-process overachiever. Most of the students in this group had

training. conditions that were diagnosed as mental retardation

Occupational therapists can treat perceptual of unknown etiology. One student had a hearing im-

problems in various ways, ranging from consultation pairment and another student was autistic. This

to direct intervention (Gilfoyle & Hays, 1979).Direct group's mean IQ was 65, and the mean age was 75

therapy's benelits are enhanced markedly if school months.

personnel and parents participate in the remediation Lll 24 children included in this project had de-

process (Friedman, 1982; Gilfoyle & Hays, 1979; layed writing readiness skills and were unable to

Goldstein, O'Brien, &Kat2,1981). The importance of learn these skills in a typical classroom environment.

family involvement has been emphasized with the None of the children had mastered all nine of the

passage of the Education of the Handicapped Act elementary designs on the Developmental Test of Vi-

Amendments of 1986 (public Law 99-457), which sual-Motor Integration. All of the children showed

emphasizes team participation and the development comparable delays on the fine motor subtests of the

of an individualized family service plan in early inter- Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency

vention. The bill encourages the parents' participa- (Bruininks, 7978), the Peabody Developmental Motor

tion in the development and implementation of an Scales-Fine Motor Scale (Folio & Fewell, 1983), the

intervention program. Miller Assessment for Preschoolers (Miller, 1988),

The writing readiness program described in this and the Motor-Free Visual Perception Test (Colarusso

paper was developed as a result of numerous referrals & Hammill, 7972), which measure fine motor control

from elementary school teachers requesting help for and visual-perception skills. All of the 5- to 6-year-old

children who could not write. I developed a pilot children who had been referred to me over a 6-year

program to teach writing readiness skills and used it period were included in the program if they met the

with children of varying abilities. The program com- following criteria: (a) the severity of the problems

bined direct therapy with an ongoing supplemen- exhibited by each child warranted both direct therapy

tary program implemented by school personnel or and a supplementary program and (b) the child's de-

parents. velopmental delay in writing readiness skills was at

r12 February 199O, Volume 44, Number 2

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 02/02/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Ieast 1 year ot more when compared to chronological rect therapy. A classroom teacher, classroom aide, or

age. Six of the 12 children in Group 1 were delayed parent, using the program ourlined by the occupa-

more than 7/zyears; the remainder were delayed 1 to tional therapist, worked with the child a minimum of

lYz years. Group 2 had I child delayed I year and 5 three times a week for 10 minutes at a time. The adult

children delayed more than IVz years. Group 3 had 7 was given a structured format to follow, and each ses-

child delayed 7/z years and 5 children delayed more sion consisted of the following activities:

than IVz years.

Children who were inirially referred but who I. IVarm-up actiuities. These consisted of ele-

later moved, who were delayed less than 1 year, or mentary designs, well below the child's readi-

who did not experience both direct therapy and the ness level, drawn on the blackboard and on

supplementary program were not included in this paper (e.g., making railroad tracks by filling in

study. vertical lines between two horizontal lines).

2. Structured work sbeets from tbe Dubnof

TreAtnxent Scbool's program of sequential perceptual-

As part of the diagnostic process, the Developmental motor exercises (Dubnoff, Cbambers, &

Test of Visual-Motor Integration was used to deter- Scbaefer, 1968) Each work sheet conrained a

mine the developmental level of each child's writing series of simple mazes on which the child

readiness skills. I administered and scored the tesr drew a line that matched the original as

according to the test directions. The test was read- closely as possible. The difficulty level was

ministered after L year. The change in each child's increased very gradually: The mazes started

writing readiness developmental level was used to with single vertical and horizontal lines,

evaluate his or her progress. which eventually were combined into letter

The therapy program used with these students forms. To reduce the cost of materials, a plas-

had two parts, which were administered concurrently. tic template was used over each sheet, and the

One part of the intervention involved direcr rherapy, child used a grease pencil on rhe template.

in which I, the occupational therapist, saw each child 3. Manuscript letter practice. ln the last part of

individually once a week for 30 minutes. In a few each session, the child, working at his or her

situations, because of time constraints or better per- developmental level, made capital manuscript

formances, I saw the children in pairs. Activities dur- letters on the blackboard. The straight-line

ing therapy focused on writing readiness skills and letters were mastered first, followed by the

included multisensory stimulation and large move- letrers with diagonal elemenrs, and finally the

ment patterns. Therapy activities were directed at in- curved letters. \Whatever the child did on the

creasing the child's attention to lines and elementary blackboard, he or she then repeated on paper

designs. The child was asked ro copy simple design using a grease pencil.

elements using a variety of media including paper

The emphasis of the supplemenrary daily pro-

strips, masking tape on the floor, chalk of various

gram was a sufficiently slow pace so that the child

colors and sizes, clay, or a finger trail on the black-

would succeed every day. The parent or aide usually

board or in sand. Children who were slow to respond

reported that the child was delighted and proud of the

were given a 1-lb wrist weight to wear intermittently

ability to do the work. As the child's confidence grew,

on the dominant forearm to facilitate sensory pro-

the pace quickened. At least once a month, the thera-

prioceptors. As the child progressed, the elementary

pist met with the adult to ensure the appropriateness

designs used during therapy became more complex

of the program and the pace.

and the therapy activities eventually approximated

Typically, the supplementary program conrinued

manuscript letters. To vary the sensory stimulation

for 5 to 8 months. Thereafter, the child usually had

and to heighten interest and responsiveness, the ther-

either progressed sufficiently or was less motivated,

apist used other readiness activities during the ther-

in which case the program was used less frequently

apy sessions, including bead stringing, block design,

(i.e., once or twice a week). \7hen school resumed in

parquetry, and paper folding. All of the therapy acrivi-

the fall, direct therapy was discontinued if the student

ties were designed to increase attention to detail and

was able to do the written assignments without ex-

lines and to improve control of the fingers and of the

cessive frustration. Otherwise, therapy was continued.

writing instrument. The therapist's role was to After 1 year, follow-up testing was done.

strengthen the child's readiness skills. Letter forma-

tion was taught by both the classroom teacher and the

adult using the supplementary program. Results

The second part ot the intervention involved a All 12 of the children in Group 1 mastered the nine

supplementary program that complemented the di writing readiness designs on the Developmental Test

Tbe American Journal of Occupatiortal Tberapy rr3

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 02/02/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

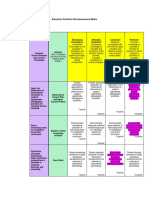

Table 1 dation in Group 3 is also significant. \fhen the de-

Mean Performance Scores of Elementary-Age Children mand for services exceeds the availability of thera-

on the Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integrationa

pists. such services should be made available to those

Initial Score Retest Score children most likely to benefit.

Group (in months) (in months) Gain

The difference in net gain made by the girls and

64.7 9.) 4.61

1

boys in Groups 2 and 3 is surprising. Typically, girls

2 46.o 63.0 77.0 3.44

'JZ

48.O 60.0 12.O 7.r3 do better than boys on paper-and pencil activities.

J

" (Beery,1982) Judd, Siders, Siders, & Atkins (1986) examined sex-

related differences of first graders on a design copy

activity and a dotting circle activity. The girls did sig

of Visual-Motor Integration within 1, year. Four chil- niflcantly better on the design copy activity, but no

dren in Group 2 and 4 children in Group 3 mastered difference was found between the groups on the dot-

all nine designs. The remaining 2 children in Group 2 ting circle activity. Perhaps the girls in this study

mastered eight of the nine designs and could occa- showed less improvement because they had primary

sionally make a triangle. The remaining 2 children in or more severe perceptual-motor deficits, rather than

Group 3 were able to make vertical and horizontal just delayed development.

lines singly and in combination but were still unable Overall, the children in Groups 1 and 3 were

to draw diagonal lines. closer in age than were those in Group 2. Group 2's

The largest gain in developmental skill level was meanage was 5 months younger than Group 1's mean

made by Group 2-a gain of 17 months with a range age and 8 months younger than Group 3's mean age.

of 14 to 22 months (see Table I for a summary of The oldest child in Group 2 was almost I year

performance scores). younger than the oldest child in either of the other

The sensorimotor writing readiness program was two groups. However, the children in Group 2 made

more successful with the special education students the most progress. This suggests that there is an opti-

in Group 3 than with average-IQ students in Group 1, mal time for remediating delayed readiness skills.

but the gain was not significantly different from the The older children in Groups I and 3 may have be-

expected normal maturation. The average gain for come habituated to failure with pencil skills and, as

Group 3 was 12 months with a range of 2 to 22 Furner (1961) indicated, more resistive to change.

months. The average gain for Group 7was9.5 months Contrary to my expectations, the regular educa-

with a range of 3 to 18 months. tion students in Group 1 made the least progress (see

The sex effect was not significant for Group 1. Table 1). The reasons for this are unclear. The pretest

The sex effect was significant, however, for Groups 2 level of readiness skills was more advanced for this

and 3. Both of these groups had below-average IQ group as compared with the other two groups. Ini-

scores (<80). The combined group of boys from tially, this group on the average could make six of the

Groups 2 and 3 @: 6) had an average gain of 17 nine designs on the Developmental Test of Visual-

months, which was significantly greater than the gain Motor Integration, whereas the other two groups

expected from maturation alone. The girls from could make only four or five designs. Perhaps once

Groups 2 and 3 @ : 5) had an gain of 11.83 the readiness skills were mastered, the Developmen-

months. ^veruge

tal Test of Visual-Motor Integration was no longer a

sensitive measure of progress; the value of this test to

Discussion measure functional paper-and-pencil skills beyond

The results of this program indicate that special popu- the readiness level needs to be examined. This proj-

lations who have deficits in their writing readiness ect. however. demonstrates the usefulness of the De-

skills will benefit from individualized instruction that velopmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration to as-

emphasizes multisensory training. This particular sess paper-and-pencil and fine motor skills of pre

method of improving writing readiness skills is espe- school- and early-elementary-age children. The test is

cially helpful with those children who have a differ administered easily and quickly, and previous studies

ence of 15 points or more between their verbal and indicate a high test-retest reliability (Breen, Carlson,

performance IQ scores on the l(echsler Intelligence & Lehman, 1985; Klein,1978; Ryckman & Rentfrow,

Scale for Children-Revised. Children with this IQ 797I). Its ease in administration makes it a particu-

profile should therefore be given priority for therapy larly valuable tool for the measurement of writing

intervention. Often, this tlpe of child becomes frus- readiness skills.

trated with the "seatwork" commonly done in the One of the unique elements of the writing readi-

kindergarten or first-grade classroom and experiences ness program is its combination of direct therapy with

few successful readiness activities. The 12-month an ongoing classroom-oriented remedial program.

average gain made by the children with mental retar- \fith the involvement of teachers, aides, and parents,

lt4 Februaryt 1PPo, Volume 44, Number 2

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 02/02/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

the new skills that the child learns in therapy can be ment: A multi disciplinary approacb (Vol.2, pp.31.1._328).

reinforced through practice. Additionally, morivation New York: Academic Press.

and enthusiasm seem to be heightened when a Alston, J., & Taylor, 1. (t987). Handwriting theory,

researcb, and practice. New york: Nichols.

teacher, a parent, or both share in the responsibility

Beery, K. E. (1,982). Reuised administration, scoring,

for a child's progress. Certainly, recognition of the and teacbing ntanualfor tbe Deuelopmental Test of Visuit

benefits of a team effort is emphasized in public Law Motor Integration. Chicago: Follett.

99-457. Breen, M. J., Carlson, M., & Lehman, J. (1985). The

Another feature of this program is the structured Revised Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration: Its

relation to the VMI, \7ISC-R, and Bender Gestalt for a group

format of the supplementary program. The parents

of elementary aged learning disabled students. lournal of

and school personnel favorably noted the ease with Learning Disabilities, 15, 136-138.

which they could follow the directions and use rhe Bruininks, R. H. (1978). Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of

materials. Additionally, because the work sheet Motor Profciency. Circle Pines, MN: American Cuidance

packets were prearranged, the therapist did not need Services.

Burke, D., & Burke, K. (1980). Sensory-Motor'Vriting

to devote time to finding new materials for each child.

Program. Tulsa, OK: Modern Education.

This project poses many quesrions. \7hich Colarusso, R. P., & Hammill, D. D . (t972) . Motor-Free

method of intervention is the most effective-direct Visual Perception Test. San Rafael, CA: Academic Therapy.

therapy or a supplementary program? Or were the Dubnoff,8., Chambers, I., & Schaefer,F. (.t968).6ub-

gains evident in this program attributable to the com- nof program 1, leuel 2: Experiential perceptuat motor ex-

ercises. Boston: Teaching Resources Corp.

bination of the two methods? A research model could Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of

be used to examine the treatment effect through a 1986 (Public Law 99-457),20 U.S.C. S 1400.

comparison of a control group and three expenmen- Folio, M. R., & Fewell, R. R. (1983). peabody Deuelop-

tal groups, each receiving a different treatment. mental Motor Scales and ActiuitJ) Cards. AIIen, TX: DLM

Other components of this training program are Teaching Resources.

Friedman, B. (1982). A program for parents of children

untested and need to be challenged. I believe that the

with sensory integrative dysfunction. American Journal of

use of a resistive writing instrument (e.g , a lJrease Occupational Tberapy, 36, 586-589.

pencil) provides increased sensory feedback to the Furner, B. (1967). The developmenr of a program of

student and is therefore conducive to optimal learn- instruction lor beginning handwriting emphasizing verbal-

ing. Further testing is needed ro confirm this hypoth- iTation ofprocedures to increase perception and an analysis

of the effectiveness of this program through comparilon

esis. The use of wrist weights to promote increased with a commercial method. Dissertation Abstracts Inter-

control of a writing instrument also needs further ex- nationaL 28(02 A), 389. (Universitv Microfilms No.

amination. In addition, although the Dubnoff School 6--09056)

materials are no longer available commercially, other Gilfoyle, E. M., & Hays, C. 0979). Occupational ther-

similar materials are available, such as Burke and apy roles and functions in the education of the school-based

handicapped student. American Journal of Occupational

Burke's (1980) Sensory-Motor \Vriting program and r berap)L 55, >o>-> /o.

Zaner-Bloser's (1982) handwriting method. Many of Goldstein, P. K., O'Brien, J D., & Katz, G. M. (1981). A

these programs are reviewed in an article by Loikith learning disability screening program in a public school.

and Ritter (1989). Further clinical studies are needed American Journal of Occupational Tberapy, 35, 1jI_455.

to ascertain their benefits. Jennings, P. A. (1974). Hapric perceprion and form

reproduction by kindergarten children. Anterican Journal

Finally, occupational therapy intervention tech- of Occupational Tberapy, 28, 27 4-280.

niques that deal with the other motor components of Judd, D. M., Siders,J. A., Siders, J.2., & Arkins, K. R.

writing readiness, such as sitting posture, trunk and (1986). Sex related differences on fine moror tasks at grade

shoulder stability, pencil grip, and handedness, need one. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 62,307 312.

to be examined. Evaluation tools, test instruments, Klein, A. E. (1978). The validity of the Beery Test of

Visual Motor Integration in predicting achievemenr in kin-

and treatment methods are all important areas for dergarten, first and second grades. Educational and psy-

research. a c bological MeasuremenL 38, 457 -45L

Laszlo, J I , & Bairsrow, p. J. (1933). Kinaesthesis: Its

measurement, training and relationship to motor control.

Acknowledgment

Quarterly Journal of Experimental psycbology, 35A,

411-127.

I wish to thank Carolyn Friederich and Carol paul for their Laszlo,J I., & Bairsrow, P.J. (1984). Handwriting: Dif-

assistance. ficulties and possible solurions. Scbool psycbologl,t Inlerna-

tional, 5,207 213.

Lewis, E. R., & Lewis, H. P. (1965). An analysis of errors

References in the formation of manuscript letters by first-grade chil-

dren. American Educational Researcb Journal, 2, 25 35.

Ajuriaguerra, J., & Auzias, M. (1975). preconditions for Loikith, C., & Ritter, L. K. (1989, March 2). Review: A

the development of writing in the chiid. In E. H. Lenneberg guide to handwriting . . there's more to it than just ABCs.

& E. Lenneberg (Eds.), Foundations of language deuelop- OTlVeek,pp 4-5,30-3r.

Tbe American Journal of Occupational Tberapy rr5

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 02/02/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Mattison, R. 8., Mclntyre, C. \(., Brown, A. S., & Murray, Simner, M. L. (1982). Printing errors in kindergarten

M. E. (1986). An analysis of visual-motor problems in learn- and the prediction of academic performance. Journal of

ing disabled children. Bulletin of tbe Psychonomic Society, Learning Disabilities, 15, 155,159.

)t ) t->+. Stott, D. H., Henderson, S. E., & Moyes, F. A. (1987).

Miller, t. J. (1988). Miller Assessment for Prescboolers. Diagnosis and remediation of handwriting problems.

San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp. Adapted Pbysical Actiuity Quarterly, 4, 137 147.

Nihei, Y. (1983). Developmental change in covert Strayer, J., & Ames, E,'W. (1972). Srimulus orientarion

principles for the organization of strokes in drawing and and the apparent developmental lag between perception

handwriting. Acta Psycbologica, 54, 221-232. and performance. Cbild Deuelopment, 43, 1345-1354.

Ryckman, D. 8., & Renrfrow, R. K. (1971). The Beery 'Wechsler, D. (1974). Wecbsler Intelligence Scale

for

Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration: An inves- Cbildren-Reuised New York: Psychological Corp.

tigation of reliability. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 4, Zaner-Bloser, Inc. (1982) . Handuriting. Columbus,

48-49. OH: Author.

rt6 Februarlt 199O, Volume 14, Nun'tber 2

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 02/02/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Reading CurriculumDokument16 SeitenReading Curriculumapi-478596695Noch keine Bewertungen

- Action Plan in Girls Scout of The Philippines: Henry Gusse Christian School Inc. Brgy 171 Bagumbong, Caloocan CityDokument3 SeitenAction Plan in Girls Scout of The Philippines: Henry Gusse Christian School Inc. Brgy 171 Bagumbong, Caloocan CityMybhabylabz Francis AndfranzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Italian (Learn Italian With Teach Yourself) - Lydia VellaccioDokument5 SeitenComplete Italian (Learn Italian With Teach Yourself) - Lydia Vellacciohahexihu0% (3)

- Optometric Vision TherapyDokument6 SeitenOptometric Vision TherapyBlogKing100% (1)

- Dysgraphia PDFDokument11 SeitenDysgraphia PDFLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors affecting student performanceDokument3 SeitenFactors affecting student performanceYasser Badr0% (1)

- A Frame of Reference For Visual PerceptionDokument40 SeitenA Frame of Reference For Visual Perceptionkura100% (1)

- Improving visual-motor skills through OTDokument6 SeitenImproving visual-motor skills through OTRidwan HadiputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11 PDFDokument31 SeitenChapter 11 PDFPrashant Kumar SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conduction 5e Model Lesson Plan William Sanchez 3Dokument24 SeitenConduction 5e Model Lesson Plan William Sanchez 3api-3843719100% (1)

- Application LetterDokument1 SeiteApplication LettersinosikpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dale's Cone of ExperienceDokument18 SeitenDale's Cone of ExperienceSuzanne SarsueloNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Hierarchical Model For Evaluation and Treatment of Visual Perceptual Dysfunction in Adult Acquired Brain Injury Part 1Dokument13 SeitenA Hierarchical Model For Evaluation and Treatment of Visual Perceptual Dysfunction in Adult Acquired Brain Injury Part 1Sebastian CheungNoch keine Bewertungen

- FInal Session 10 Determining Cause and EffectDokument120 SeitenFInal Session 10 Determining Cause and EffectJuliet Echo NovemberNoch keine Bewertungen

- System ApproachDokument13 SeitenSystem ApproachNeethu VijayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grades 1-12 STEM Daily Lesson Log - General Biology 1 Cell StructureDokument2 SeitenGrades 1-12 STEM Daily Lesson Log - General Biology 1 Cell StructureBeeWinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dunn, The Impact of Sensory Processing Abilities On The Daily Lives of Young Children and Their Families - A Conceptual Model, 1997 PDFDokument14 SeitenDunn, The Impact of Sensory Processing Abilities On The Daily Lives of Young Children and Their Families - A Conceptual Model, 1997 PDFmacarenavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pwords For Teachers IiDokument8 SeitenPwords For Teachers IiJade BaliolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Efficacy of Computer Assisted Cognitive Training in The Remediation of Specific Learning DisordersDokument4 SeitenThe Efficacy of Computer Assisted Cognitive Training in The Remediation of Specific Learning DisordersRakesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relationship Between Visuomotor and Handwriting Skills of Children in KindergartenDokument7 SeitenRelationship Between Visuomotor and Handwriting Skills of Children in KindergartenLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ED452998Dokument17 SeitenED452998Sara CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Learning Monitoring PlanDokument7 SeitenIndividual Learning Monitoring PlanJanet Manalo GamayotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recognizing Facial Emotions For Educational Learning SettingsDokument12 SeitenRecognizing Facial Emotions For Educational Learning SettingsIAES International Journal of Robotics and AutomationNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1499 6761 1 PBDokument17 Seiten1499 6761 1 PBMISS HILDANoch keine Bewertungen

- School Children TestsDokument10 SeitenSchool Children TestsMamiko Fenella SyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Go SWM I 2006 From Research To PracDokument46 SeitenGo SWM I 2006 From Research To PracAdela Fontana Di TreviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developmental Dissociation Between TheDokument9 SeitenDevelopmental Dissociation Between ThemeiselinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Stage ModelDokument4 Seiten3 Stage ModelLourence Dela Cruz VillalonNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On The Comparison Between Multiple Intelligence and Emotional Adjustment of Secondary School Students in KeralaDokument8 SeitenA Study On The Comparison Between Multiple Intelligence and Emotional Adjustment of Secondary School Students in KeralaImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infant Behavior and Development: ReviewDokument7 SeitenInfant Behavior and Development: ReviewNesi Jamiat SulaimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bristol Diploma lifespan cns development and damage 2022Dokument90 SeitenBristol Diploma lifespan cns development and damage 2022mszakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exner 10Dokument8 SeitenExner 10Sara CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Test of Sensory Functions in Infants: Test-Retest Reliability For Infants With Developn1ental DelaysDokument6 SeitenThe Test of Sensory Functions in Infants: Test-Retest Reliability For Infants With Developn1ental Delaysadrika94Noch keine Bewertungen

- Galvin Et Al., 2017Dokument17 SeitenGalvin Et Al., 2017Fabiana MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weber 2013Dokument8 SeitenWeber 2013s3.neuropsicologiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Best Portfolio Self Assessment Matrix-1Dokument2 SeitenBest Portfolio Self Assessment Matrix-1api-540469290Noch keine Bewertungen

- Integración SensorialDokument6 SeitenIntegración SensorialGeorginaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task 5 Web-Based ProgramsDokument2 SeitenTask 5 Web-Based Programsapi-294972766Noch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Visual PerceptionDokument6 SeitenRole of Visual PerceptionCeleste LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Leader Project Schneringer HandoutsDokument4 SeitenTeacher Leader Project Schneringer Handoutsapi-284308390Noch keine Bewertungen

- Advan 00138 2015Dokument10 SeitenAdvan 00138 2015haileyesusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shalev Von Aster Dyscalculia DMCN 2007Dokument6 SeitenShalev Von Aster Dyscalculia DMCN 2007Fono CaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Correlation of Self Reported Sleep Duration With.63Dokument4 SeitenCorrelation of Self Reported Sleep Duration With.63vanathyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perceptual & Motor Skills: Physical Development & MeasurementDokument10 SeitenPerceptual & Motor Skills: Physical Development & MeasurementAleja ToPaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agricultural education scholarships and careers at Kansas State UniversityDokument4 SeitenAgricultural education scholarships and careers at Kansas State UniversityDa Grit WolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Memory Training For Kids IntelligenceDokument11 SeitenEffect of Memory Training For Kids Intelligencesullivan06Noch keine Bewertungen

- Goodway 1997Dokument13 SeitenGoodway 1997KYRIAKI PAPADOPOULOUNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Clercq-Quaegebeur, 2017 Arithmetic Abilities in Children With DyslexiaDokument14 SeitenDe Clercq-Quaegebeur, 2017 Arithmetic Abilities in Children With DyslexiaJorgeVictorMauriceLiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Document 19Dokument2 SeitenDocument 19api-501437271Noch keine Bewertungen

- Structured Cognitive Training Yields Best Results.2Dokument11 SeitenStructured Cognitive Training Yields Best Results.2ARBOLEDA ORREGO JOSE DANIELNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gross motor skills of children with mild intellectual disabilitiesDokument7 SeitenGross motor skills of children with mild intellectual disabilitiesnurul_sharaswatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week - 1 - August 22 - 26,2022Dokument15 SeitenWeek - 1 - August 22 - 26,2022Fabian P. SIcatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hybrid Facial Expression Recognition (FER2013) Model For Real-Time Emotion Classification and PredictionDokument9 SeitenHybrid Facial Expression Recognition (FER2013) Model For Real-Time Emotion Classification and PredictionBOHR International Journal of Internet of things, Artificial Intelligence and Machine LearningNoch keine Bewertungen

- BrigEC SMPLR Brochure 1Dokument32 SeitenBrigEC SMPLR Brochure 1megoo zenNoch keine Bewertungen

- SLA Lecture Notes 3Dokument4 SeitenSLA Lecture Notes 3Hollós DávidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action Plan For GEN MATHDokument1 SeiteAction Plan For GEN MATHGeraldine ElisanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Observation Task 5: Literacy Software /web Based ProgramsDokument2 SeitenObservation Task 5: Literacy Software /web Based ProgramsMaith 2510Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chen Et Al 2022 - Cognitive Training Enhances Growth Mindset in Children Through Plasticity of Cortico-Striatal CircuitsDokument10 SeitenChen Et Al 2022 - Cognitive Training Enhances Growth Mindset in Children Through Plasticity of Cortico-Striatal Circuitsprairie_fairyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2021 - Dysgraphia Classification Based On The Non-Discrimination Regularization in Rotational Region Convolutional Neural NetworkDokument9 Seiten2021 - Dysgraphia Classification Based On The Non-Discrimination Regularization in Rotational Region Convolutional Neural NetworkPanagiotis TrochidisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key WordsDokument5 SeitenKey Wordsapi-382172511Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Developing Infant Creates A Curriculum For Statistical LearningDokument12 SeitenThe Developing Infant Creates A Curriculum For Statistical LearningBozdog DanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task 5Dokument2 SeitenTask 5api-294972271Noch keine Bewertungen

- Inter 3Dokument4 SeitenInter 3I Gusti komang ApriadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mini-Mental State Pediatric Exam norms for young Italian kidsDokument6 SeitenMini-Mental State Pediatric Exam norms for young Italian kidsNaveen KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Childhood Victoria PecotDokument6 SeitenEarly Childhood Victoria Pecotapi-534405902Noch keine Bewertungen

- MFK PPT U 2.1Dokument6 SeitenMFK PPT U 2.1mohd ihtishamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lee 2009Dokument4 SeitenLee 2009MariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summer Par TableDokument5 SeitenSummer Par Tableapi-608708608Noch keine Bewertungen

- Observation Task 5Dokument2 SeitenObservation Task 5api-308081446Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Gestured Instruction On The Learning of Physical Causality ProblemsDokument20 SeitenThe Effect of Gestured Instruction On The Learning of Physical Causality Problems赵文Noch keine Bewertungen

- 8 Enhancing Esl Learners Sumaira QanwalDokument11 Seiten8 Enhancing Esl Learners Sumaira QanwalCamiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiple Intelligences: Skills and StrategiesVon EverandMultiple Intelligences: Skills and StrategiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multisensory PDFDokument14 SeitenMultisensory PDFWidya UlfaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syballus Dan DesignDokument8 SeitenSyballus Dan DesignNtahpepe LaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accepted Manuscript: Journal of Science and Medicine in SportDokument27 SeitenAccepted Manuscript: Journal of Science and Medicine in SportLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychometric Properties of The Strengths and Difficulties QuestionnaireDokument9 SeitenPsychometric Properties of The Strengths and Difficulties QuestionnaireLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of General Dynamic Coordination in The Handwriting Skills of ChildrenDokument10 SeitenThe Role of General Dynamic Coordination in The Handwriting Skills of ChildrenLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SIG Vortrag Fliesser V2 1finalDokument16 SeitenSIG Vortrag Fliesser V2 1finalLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contribution of Tactile and Kinesthetic Perceptions To Handwriting in Taiwanese Children in First and Second GradeDokument8 SeitenContribution of Tactile and Kinesthetic Perceptions To Handwriting in Taiwanese Children in First and Second GradeLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fine Motor Deficiencies in Children Diagnosed As DCD Based On Poor Grapho-Motor AbilityDokument23 SeitenFine Motor Deficiencies in Children Diagnosed As DCD Based On Poor Grapho-Motor AbilityLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handwriting Performance On The ETCH-M of Students in A Grade One Regular Education ProgramDokument9 SeitenHandwriting Performance On The ETCH-M of Students in A Grade One Regular Education ProgramLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research on validity and applications of Draw a Person testDokument18 SeitenResearch on validity and applications of Draw a Person testHazel Penix Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research in Developmental Disabilities: Lauren E. Cox, Elizabeth C. Harris, Megan L. Auld, Leanne M. JohnstonDokument11 SeitenResearch in Developmental Disabilities: Lauren E. Cox, Elizabeth C. Harris, Megan L. Auld, Leanne M. JohnstonLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Online Analysis of Handwriting For Disease Diagnosis: A ReviewDokument7 SeitenOnline Analysis of Handwriting For Disease Diagnosis: A ReviewLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Movement Science: Andréa Huau, Jean-Luc Velay, Marianne JoverDokument15 SeitenHuman Movement Science: Andréa Huau, Jean-Luc Velay, Marianne JoverLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Motor Development and Hand Laterality A Kinematic Analysis of Drawing Movements - 2000Dokument4 SeitenHuman Motor Development and Hand Laterality A Kinematic Analysis of Drawing Movements - 2000Lena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impactofapsychomotorprograminterventiononchildrenpresentingwritingdisabilities NASPSPA2017Dokument5 SeitenImpactofapsychomotorprograminterventiononchildrenpresentingwritingdisabilities NASPSPA2017Lena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAN - 2019 - 10 - Reproducibility IntroductionDokument25 SeitenCAN - 2019 - 10 - Reproducibility IntroductionLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thomassen Teulings1985TimeSizeAndShapeInHandwritingDokument7 SeitenThomassen Teulings1985TimeSizeAndShapeInHandwritingLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visual Motor Skills and Reading Fluency A CorrelatDokument7 SeitenVisual Motor Skills and Reading Fluency A CorrelatLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SJP Wickietal 2014Dokument11 SeitenSJP Wickietal 2014Lena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of Different Handwriting Teaching Methods byDokument5 SeitenEvaluation of Different Handwriting Teaching Methods byLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thomassen Teulings VisibleLanguage1979Dokument9 SeitenThomassen Teulings VisibleLanguage1979Lena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teachers Perceptions of Needs and Supports For HaDokument15 SeitenTeachers Perceptions of Needs and Supports For HaLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Development of A Computer-Based Handwriting Assessment Tool To Objectively Quantify Handwriting Proficiency in Children - 2011Dokument10 SeitenOn The Development of A Computer-Based Handwriting Assessment Tool To Objectively Quantify Handwriting Proficiency in Children - 2011Lena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dialnet PerformanceOnTheMovementAssessmentBatteryForChildr 6873424Dokument16 SeitenDialnet PerformanceOnTheMovementAssessmentBatteryForChildr 6873424Lena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- IGSE Signatureposter 2011 0608Dokument1 SeiteIGSE Signatureposter 2011 0608Lena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PSY011 All EnglishDokument12 SeitenPSY011 All EnglishLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relationship Between Gender and Motor Skills in PRDokument5 SeitenRelationship Between Gender and Motor Skills in PRLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Importance of Handwriting for Learning: A High-Density EEG StudyDokument45 SeitenThe Importance of Handwriting for Learning: A High-Density EEG StudyLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handwriting Movement Kinematics For Quan PDFDokument8 SeitenHandwriting Movement Kinematics For Quan PDFLena CoradinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cumbria - PGCE - Secondary - Prog2019-20Dokument3 SeitenCumbria - PGCE - Secondary - Prog2019-20stuffer27Noch keine Bewertungen

- Liam Bourassa - Professional Development Plan-2Dokument2 SeitenLiam Bourassa - Professional Development Plan-2api-438470477Noch keine Bewertungen

- Conditions Under Which Assessment Supports Student LearningDokument2 SeitenConditions Under Which Assessment Supports Student LearningDigCity DiggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using A Multimedia Application in The Teaching of LiteratureDokument9 SeitenUsing A Multimedia Application in The Teaching of LiteratureErda Bakar100% (1)

- Basic Curriculum ConceptsDokument16 SeitenBasic Curriculum Conceptsedward osae-oppongNoch keine Bewertungen

- AUD1202 Course Syllabus - Forensic AccountingDokument21 SeitenAUD1202 Course Syllabus - Forensic AccountingGellie BuenaventuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clil and PBLDokument61 SeitenClil and PBLElisangela SouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ece 4410 Lesson Plan 2Dokument7 SeitenEce 4410 Lesson Plan 2api-464509620Noch keine Bewertungen

- CECE Module 12Dokument5 SeitenCECE Module 12Ruth MoToNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Animals Sound Song-LyricsDokument6 SeitenThe Animals Sound Song-LyricsJoanne Lian Li Fang100% (1)

- Annotating & OutliningDokument15 SeitenAnnotating & OutliningJenni ArdiferraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 386316419-Chart and Paper On Classical ConditioningDokument6 Seiten386316419-Chart and Paper On Classical ConditioningNyatika CorneliusNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Safety, Relationships, and Teaching - Learning As Cited Above Affect The Psychology and Climate in The Classroom?Dokument15 SeitenHow Safety, Relationships, and Teaching - Learning As Cited Above Affect The Psychology and Climate in The Classroom?Shiela Marie Nazaret - MateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student feedback template with grammar tipsDokument5 SeitenStudent feedback template with grammar tipsMariel ManaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entire TwsDokument53 SeitenEntire Twsapi-332989759Noch keine Bewertungen

- Using Technology to Enhance TeachingDokument7 SeitenUsing Technology to Enhance TeachingAbryn Jirel L. AysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Every Child is SpecialDokument2 SeitenEvery Child is SpecialJoy ManliguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compare and Contrast ArticleDokument5 SeitenCompare and Contrast ArticleJasmin AdrianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Confirmation Participation Design-Led Approach CourseDokument1 SeiteConfirmation Participation Design-Led Approach CourseVenkat Ram ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen