Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Globalisation and Health - The Need For A Global Vision

Hochgeladen von

Jean Pierre GoossensOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Globalisation and Health - The Need For A Global Vision

Hochgeladen von

Jean Pierre GoossensCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Health Policy

Globalisation and health: the need for a global vision

Ted Schrecker, Ronald Labonté, Roberto De Vogli

Lancet 2008; 372: 1670–76 The reduction of health inequities is an ethical imperative, according to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants

Institute of Population Health, of Health (CSDH). Drawing on detailed multidisciplinary evidence assembled by the Globalization Knowledge

University of Ottawa, Ontario, Network that supported the CSDH, we define globalisation in mainly economic terms. We consider and reject the

Canada (T Schrecker MA,

R Labonté PhD); and

presumption that globalisation will yield health benefits as a result of its contribution to rapid economic growth and

Department of Epidemiology associated reductions in poverty. Expanding on this point, we describe four disequalising dynamics by which

and Public Health, University contemporary globalisation causes divergence: the global reorganisation of production and emergence of a global

College London, London, UK labour-market; the increasing importance of binding trade agreements and processes to resolve disputes; the rapidly

(R De Vogli PhD)

increasing mobility of financial capital; and the persistence of debt crises in developing countries. Generic policies

Correspondence to:

designed to reduce health inequities are described with reference to the three Rs of redistribution, regulation, and

Ted Schrecker, Department of

Epidemiology and Community rights. We conclude with an examination of the interconnected intellectual and institutional challenges to reduction

Medicine, Institute of Population of health inequities that are created by contemporary globalisation.

Health, University of Ottawa,

1 Stewart Street, Ottawa, ON,

K1N 6N5, Canada

Introduction: is globalisation good for you? Feachem has claimed that “globalisation is good for

tschrecker@gmail.com The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of your health, mostly”8 because countries that integrate

Health (CSDH) concluded that: “Reducing health more fully into the global economy, especially through

inequities is…an ethical imperative. Social injustice is trade liberalisation, grow faster and are therefore better

killing people on a grand scale.”1 Efforts to correct this able to reduce poverty.9 The argument is compelling, but

injustice should address the context created by it does not fully satisfy the ethical imperative identified

globalisation—the incorporation of national economies by the CSDH, since health inequities exist worldwide

and societies into a world system “through movements even in the absence of poverty, and essentially it is flawed.

of goods and services, capital, technology and (to a lesser Research used to support this argument has shown that

extent) labour”.2 This incorporation results in the countries termed globalisers—in which tariffs fell and

exposure of economies and societies to an expanding the ratio of trade to GDP increased after 1980—grew

range of influences outside their borders. Although it is faster than non-globalisers.9 The findings have been

fundamentally an economic process, contemporary criticised among other reasons for how the globalisers

globalisation is multidimensional, and therefore more were identified, the causal sequence (with the most rapid

complex than an earlier period of globalisation growth in some countries having occurred before major

(1870–1914), in which trade and colonisation were the trade liberalisation), and because many globalisers

main channels of influence. pursued dirigiste economic policies in areas other than

We analyse the health effects of globalisation with trade, whereas some non-globalisers began the period

reference to an established model for explaining health already highly integrated into the global economy.10–12

disparities.3 This model emphasises how social context A more fundamental point is that between 1981 and 2005,

creates differential exposures and vulnerabilities, which while the world’s economic product quadrupled, progress

in turn affect health outcomes. Especially important are toward poverty reduction was limited and uneven. On the

“those central engines in society that generate and basis of World Bank poverty lines updated in 2008, the

distribute power, wealth and risks”.3 Nowadays such estimated number of people living on US$1·25/day or less

engines operate in the environment created by (at 2005 prices, adjusted for purchasing power parity)

globalisation, when they are not actually driven by it. declined by 500 million.13 However, the decline was

Differential exposures and vulnerabilities can be a result accounted for by drastic poverty reductions in China

of material deprivation, which is the case for more than (figure, A), about half of which occurred before its market

800 million chronically undernourished people reforms and export-led growth. Outside of China, extreme

worldwide, 1 billion slum dwellers, and those who lack poverty increased, mainly because the number of

access to basic health services. Relative deprivation or sub-Saharan Africans living in poverty almost doubled.

position within a hierarchy is also important. The Reasons exist for scepticism about whether Chinese

contribution of these two factors to near-ubiquitous poverty reductions will lead to future improvements in

socioeconomic gradients in health is a topic of continuing health, since privatisation of China’s health system has

controversy.4,5 Although their contribution will probably been accompanied by increases in the cost of health care,

depend on the context, stress-related biological thereby reducing affordability and access.1 This problem is

mechanisms of action that explain the health not unique to China.14,15 With a poverty line of US$2·50/

consequences of relative deprivation have been well day, worldwide numbers living in poverty increased from

studied in both animal and human models.6,7 Globalisation about 2·7 billion to 3·1 billion, with reductions in China

can also create new economic opportunities (for some) offset by a substantial increase in India (288 million) and

and limit the options for policies that improve health. sub-Saharan Africa (294 million) (figure, B). In general,

1670 www.thelancet.com Vol 372 November 8, 2008

Health Policy

growth is an increasingly ineffective means of poverty especially low-income countries, because trade

reduction because the benefits of growth rarely reach the liberalisation has slashed tariff revenues far in advance of

world’s poorest people.16 the development of alternative revenue sources.

Experience suggests that economic growth can benefit Baunsgaard and colleagues37 showed that low-income

poor populations, but this requires “strong commitments countries “have recovered, at best, no more than about

on the part of policymakers”,17 who could have other 30 cents of each lost dollar” of tariff revenue, and Glenday38

priorities, such as obtaining military hardware or simple reported that only six of 28 low-income countries that lost

self-enrichment. In some cases, the expressed aim of tariff revenues were able to replace them from other

reducing health disparities might not be supported by

actual resources18 or opportunities to achieve major

A

reductions in disparities at low cost might be missed.19,20 3500 Worldwide

Such policy choices must be considered in relation to the Worldwide excluding China

East Asia and Pacific†

context created by globalisation (panel). South Asia*

3000 Sub-Saharan Africa

Globalisation is disequalising Latin America and Caribbean

Middle East and north Africa

A key element of the context created by globalisation is Eastern Europe and central Asia

2500

its “inherently disequalising”22 character, which means

that it tends to reinforce divergence of incomes, wealth,

Number of people (millions)

and opportunity.23,24 This tendency is strengthened by

2000

substantial disparities in the ability to change the rules

and institutions of the global marketplace. We consider

four disequalising dynamics of globalisation, although 1500

the list is not exhaustive.

First, production has been reorganised into global

commodity or value chains, which divide production 1000

across many national borders to maximise returns.25–27

The “new international division of labour”,28 which was

500

identified more than 30 years ago, has led to an emerging

global labour-market,29,30 and the world’s labour force has

roughly doubled in size with the integration of India, 0

China, and transition countries into the world economy.31

To simplify, the result is intensified competition between B

low-income workers, because potential employees are 3500

abundant, and governments competing for foreign

investment and contract production have a strong

3000

incentive to maintain flexibility in wages and labour

standards. Conversely, employers compete for

highly-valued skills at the top of the income scale, where 2500

employees are increasingly mobile. The World Bank

Number of people (millions)

predicts that labour-market outcomes will increase

economic inequality in much of the developing world 2000

because the “unskilled poor”30 population will be left

further behind. This pattern is established in several

Latin American countries32 and it is emerging in much of 1500

Asia;33 this so-called unskilled population have already

been left behind in the industrialised world.34,35

1000

Second, binding trade agreements and processes to

resolve disputes, exemplified by the World Trade

Organization (WTO), provide essential infrastructure for 500

the global marketplace. Substantial differences in

countries’ market size and government resources affect

both their initial bargaining leverage in trade negotiations, 0

1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005

and their ability to make effective use of dispute resolution

Calendar year

mechanisms.36 As countries open up to imports,

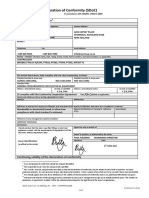

livelihoods are lost in formerly protected industries. Social Figure: Global poverty below the US$1·25/day (A) and US$2·50/day (B) poverty lines according to the World

protection measures can partly compensate, but financing Bank13

them could be difficult for many middle-income and *Includes India. †Includes China.

www.thelancet.com Vol 372 November 8, 2008 1671

Health Policy

slowly than growth.45 Conversely, the ease of capital flight

Panel: Globalisation and health: pathways of transmission in the global financial marketplace enables wealthy

and evidence of effects people to seek higher returns and lower risks by investing

An innovative econometric analysis undertaken for the assets abroad, which further increases inequality as the

Globalization Knowledge Network21 classified a range of costs of maintaining services for poorer people are

variables affecting mortality as: related to policy choices made socialised, in the form of government debt.46,47

in the context of globalisation (such as income inequality or Fourth, external debt has long been recognised to be a

immunisation rates); independent of globalisation for limiting factor on the ability of many developing

purposes of the analysis (medical progress); or “shocks” (such economies to meet the basic needs of their populations.48,49

as wars, natural disasters, or infection with HIV/AIDS). The In some cases, odious debts50,51 enriched corrupt leaders

analysis compared trends in life expectancy at birth (LEB), or financed the repression of political dissent. A recent

between 1980 and 2000, with those that would be predicted study by Mandel52 reports that about US$726 billion of the

on the basis of a counterfactual set of assumptions, in which debt owed at present by 13 developing countries is odious,

the relevant variables remained at the 1980 value or under international law it should be cancelled, and ten of

continued the same trend as the period before 1980. the countries should receive refunds of US$383 billion in

past payments on such debts.52 From the 1970s onwards, a

The results showed that worldwide, between 1980 and 2000,

much larger number of developing economies were

globalisation cancelled out most of the progress towards better

caught in a trap of rising interest rates and oil prices,

health (measured by LEB) attributable to diffusion of medical

declining prices for their commodity exports, and debt

advances. The effects of shocks combined with globalisation

obligations that increased in value as a result of currency

resulted in a slight worldwide decline in LEB (0·13 years),

devaluation under pressure from investors and

contrary to the counterfactual. On a regional basis, the largest

multilateral lenders. Over the past decade, partial debt

effects occurred in the transition economies (decline of

cancellation initiatives, such as the recent Multilateral

3·57 years, almost entirely caused by globalisation) and sub-

Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI), have increased the ability

Saharan Africa (decline of 8·95 years, almost equally caused by

of some low-income countries to invest in health and

globalisation and the AIDS epidemic, despite some offsetting

education. However, this effect has not been universal.

benefits from the diffusion of medical advances). The authors

The criteria for debt sustainability—the amount of debt a

concede the importance of the data limitations and difficulties

national government is expected to service on the basis of

with inferring causation, but nevertheless emphasise that “the

its own revenues before it becomes eligible for debt

negative association found between liberalisation-

cancellation—continue to prioritise creditor interests and

globalisation policies, poor economic performance and

limit the number of eligible countries. In most developing

unsatisfactory health trends…seems to be quite robust.”

countries, development assistance receipts are still

dwarfed by outflows of debt service payments.53

sources. This erosion of revenue-raising ability almost The influence of globalisation can be offset or

certainly compromises public investment in education compounded by domestic policy choices. Between 1997

and health care. The urgency of securing market access and 1998, the financial crises in several south Asian

for exports can lead countries with limited bargaining countries mobilised domestic political support for

power to accept provisions on intellectual property rights expanded social protection programmes.54 By contrast,

that undermine equitable access to health care,39 and most African countries have not reached the 2001 Abuja

vitiate benefits that globalisation of access to medical declaration commitment to spend 15% of general

technology might otherwise have conferred.21 government revenue on health,55 and oil-rich Nigeria has

Third, there has been a rapid increase in the mobility been one of the poorest performers. Development

of investment capital as a result of the interaction between economist Paul Collier estimates “that something around

technological advances and the deregulation of national 40% of Africa’s military spending is inadvertently financed

financial markets. Financial market integration has not by aid”,56 which is undoubtedly of interest to arms exporters

led to the growth payoffs predicted by conventional based in donor countries. Drawing worldwide attention to

economics40–42 and the frequency of financial crises has such examples could be one of the most immediately

increased since the late 1970s.43 In extreme cases, volatile positive effects of the CSDH report. A key social scientific

flows of short-term investment in shares and government question is how globalisation’s disequalising influence

bonds have destabilised entire economies, which will affect the formation of the necessary political coalitions

occurred in Mexico (1994–95), south Asia (1997–98), and to support the reduction of health inequities.

Argentina (2001–02). In each case, the national currency

depreciated by more than 50% and millions of people Three Rs for health equity

were precipitated into poverty and economic insecurity. The CSDH correctly identified reduction of health

Such crises undermine the health of the vulnerable both disparities as an ethical imperative. From this perspective,

directly and indirectly.44 These effects are worsened by the issue is not globalisation itself but rather, as

the fact that after such crises, employment recovers more philosopher Thomas Pogge has pointed out, whether

1672 www.thelancet.com Vol 372 November 8, 2008

Health Policy

plausible alternative sets of social arrangements or future trade negotiations as proposed by Collier,73 there

institutions, which would be less inimical to meeting the would be little immediate effect. Many low-income

ethical objective in question (in this case health equity), countries would remain decades away from being able to

can be imagined.57–59 The evidence is more than sufficient finance the cost of basic health care for the entire

to meet this test, suggesting the need to consider how population, about US$40 per person each year,74 much less

institutions might be changed. Globalisation did not just the costs of meeting other health-related basic needs such

happen.60 Technological change has operated partly as education, water, and sanitation.

outside of the control of policy makers but key elements Although private investment needs to be mobilised,

of globalisation—trade liberalisation, privatisation of there is widely shared recognition that redistribution of

state-owned assets, financial deregulation, and resources across national borders in support of meeting

labour-market flexibility—have been actively promoted basic human needs is an obligation.75,76 This means that the

by G7 governments, transnational corporations, and burden of proving how health equity can be achieved in an

multilateral institutions, for example, through the acceptable time without major increases in development

structural adjustment conditionalities of the International assistance now rests with the aid sceptics. There is

Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.61,62 abundant evidence that the availability of proven

Citing the need for collective policy choices and interventions would increase population health at relatively

initiatives to counterbalance the dominance of low cost.20,77 Effective scaling-up faces many challenges and

market-driven globalisation, the Globalization Knowledge will often depend on the availability of external resources.

Network53 that supported the CSDH identified the generic Increasing aid, however, should not mean doing more of

importance of “redistribution, regulation, and rights”—a the same. Aid should be directed towards meeting basic

rubric borrowed from the Finnish social policy research human needs, such as those identified in the Millennium

unit STAKES.63 For example, the ability of national and Development Goals.20,78 As the CSDH insisted, aid should

subnational governments to intervene in support of health also be linked to action plans on social determinants of

equity can be protected by use of the international human health and accountability mechanisms1 that go beyond the

rights law framework,64 identified in a CSDH background health sector, to make intersectoral action for health

paper as “the appropriate conceptual structure within possible. Donor countries must also avoid undermining

which to advance towards health equity through action on the effectiveness of aid with conditionalities such as

social determinants of health”.65 Potential policy initiatives wage-bill ceilings, or IMF insistence that countries

include development of mechanisms to assess liberalise imports more rapidly than agreed to in WTO

health-equity effects of trade policy, which was urged by commitments to qualify for debt cancellation.79

the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health in 2004,66 As another element of international redistribution,

and creation of a formal linkage between the results of eligibility for debt cancellation should be expanded, and

such negotiations and the outcomes of trade negotiations criteria for debt sustainability should be redefined with

and proceedings to resolve disputes. reference to the cost of meeting basic needs, rather than

Despite the need for caution about unanticipated effects the ability of a country to earn export revenues.80

that would actually increase inequity,67 recent analysis Additionally, with respect to development assistance,

suggests that linking market access under trade agreements accountability mechanisms should ensure that fiscal

with respect for labour standards is viable.68 Choices made flexibility created by debt cancellation is used for purposes

by the representatives of high-income countries on the related to social determinants of health—a crucial area

governing bodies of such institutions as the World Bank for multilateral agreement and institutional innovation.

and the IMF should also take human rights into account.69 Finally, creditor nations should work towards a solution

For example, IMF-recommended wage-bill ceilings, to the odious debt problem that prevents private-sector

justified on the basis of macroeconomic soundness, have creditors, aid agencies, and multilateral lenders from

prevented countries in sub-Saharan Africa from hiring trying to collect such debts.52

essential teachers and nurses, even when short-term funds

were available from promised development assistance.55,70 Intellectual and institutional challenges

This consequence of the IMF recommendations is arguably When Williamson81 coined the term “Washington

a contravention of the human rights obligations of consensus” to describe official wisdom on development

countries that dominate IMF decision-making. policy in about 1989, he “deliberately excluded from the

The paralysis of WTO negotiations in 2006 and again list anything which was primarily redistributive, as

in 2008, with regard to agricultural market access and opposed to having equitable consequences as a byproduct

development policy flexibility, underscored the difficulty of of seeking efficiency objectives, because [he] felt the

integrating trade and development policy objectives, which Washington of the 1980s to be a city that was essentially

is essential for long-term growth and poverty reduction.36,71,72 contemptuous of equity concerns”. Although that hostility

Even if the industrialised world abandoned its resistance to might have receded, mainstream economists remain

integrating development objectives into trade policy, for committed to market solutions and efficiency (a concept

example by incorporating up-front redistribution into that is indifferent to initial distributions of resources) in

www.thelancet.com Vol 372 November 8, 2008 1673

Health Policy

resource allocations, and they regard correcting for in need of immediate action by high-income countries to

market failures resulting from such factors as imperfect reduce WHO’s reliance on idiosyncratic, off-budget

information on the part of buyers and sellers to be the financing. The comparison also instantiates the broad

primary rationale for most forms of policy intervention. shift from public to private power, derived from property

Even at the national and subnational levels the resulting rights, that is associated with globalisation.

challenges are big, complicated, untidy, and largely outside WHO leadership will thus depend on effective

of the remit and often the professional competence of organisational reinvention, both internally and externally.

health ministries. Hence, the CSDH’s call for intersectoral Internally, WHO needs a more transdisciplinary, rather

action for health is critically important, but health than biomedical, orientation and it needs to engage

ministries could face an uphill battle integrating health credibly and proactively in a range of debates about the

concerns into areas that are generally the domain of direction of the world economic and geopolitical order.

finance and treasury ministries. Further, many Externally, WHO needs to function more effectively in

governments committed to redistributive policy operate the new environment for governance of global health, for

within constraints created by globalisation, such as the example by pursuing closer relationships with the UN

threat of capital flight82,83 and the continued need for the Economic and Social Council, other UN system agencies

World Bank and IMF to approve national Poverty (such as the Office of the High Commissioner for Human

Reduction Strategy Papers, which are a precondition for Rights and the International Labour Organization), and

debt cancellation and other forms of development civil society organisations and professional bodies.

assistance.84 WHO’s member states will ultimately be judged on their

Coordinated value-driven action will be needed willingness to create the conditions and supply resources

internationally to address these constraints, to counter for the necessary reinvention. Past initiatives to direct

globalisation’s disequalising dynamics, and to support globalisation in positive directions, such as the

national and subnational action to reduce health inequity. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and

For example, redesign of the World Bank and the IMF to subordinating intellectual property rights to health

reduce the over-representation of a few high-income protection imperatives to ensure access to essential

countries, and increase the transparency of deci- medicines, have shown the importance of civil society

sion making, has long been advocated by academic and campaigns informed by both evidence and ethics.

civil society commentators85,86 and is now advocated by the Conflict of interest statement

Commonwealth Heads of Government.87 Agreement is We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

also emerging on preventing financial crises, and Acknowledgments

therefore their destructive effects on health,44 as a true The thoughtful comments of three external reviewers substantially

public good that is at present inadequately provided.88 improved this article. The operations of the Globalization Knowledge

Network were supported by a grant from the International Affairs

New sources of financing for development could be Directorate of Health Canada. This paper is informed by the work of the

mobilised by means of a small tax on foreign currency Globalization Knowledge Network, but all views are those of the article

transactions, which have a present value of more than authors, or cited authors, and are not those of Health Canada, other

US$3·2 trillion/day, and measures to restrict tax avoidance members of the Globalization Knowledge Network, the CSDH, or WHO.

The funding agency played no role in the design or execution of the

through offshore financial centres. A tax on the annual research.

income from wealth estimated to be held in such centres

References

could yield an annual revenue stream equivalent to the 1 Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a

estimated cost of meeting the Millennium Development generation: health equity through action on the social determinants

Goals.1 of health (final report). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf

Mobilisation of support for health equity at the (accessed Oct 9, 2008).

international level implies a shift from self-interest to 2 Jenkins R. Globalization, production, employment and poverty:

altruism by the world’s largest and most powerful debates and evidence. J Int Dev 2004; 16: 1–12.

3 Diderichsen F, Evans T, Whitehead M. The social basis of

countries. Also needed will be the ability to overcome disparities in health. In: Whitehead M, Evans T, Diderichsen F,

resistance from rich and powerful actors, such as Bhuiya A, Wirth M, eds. Challenging inequities in health: from

managers of transnational corporations and a global ethics to action. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001: 13–23.

4 Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, House JS. Income inequality

economic-elite that is increasingly detached from national and mortality: importance to health of individual income,

allegiances. Who shall lead? As anticipated by the CSDH, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 2000;

WHO might be well placed to rediscover an advocacy 320: 1220–24.

5 Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Psychosocial and material pathways in

voice that it has lost in recent decades. However, WHO the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al.

now functions in a complex environment featuring BMJ 2001; 322: 1233–36.

multiple actors. No one governance structure for global 6 Brunner E, Marmot M. Social organization, stress, and health.

health exists that is even roughly comparable to the WTO In: Marmot M, Wilkinson RG, eds. Social determinants of health,

2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005: 6–30.

in trade policy,89 and WHO’s core budget is now less than 7 Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age

the annual expenditures of a single private foundation, patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the

which is arguably “a scandal of global health governance”90 United States. Am J Public Health 2006; 96: 826–33.

1674 www.thelancet.com Vol 372 November 8, 2008

Health Policy

8 Feachem RGA. Globalisation is good for your health, mostly. BMJ 29 World Bank. World development report 1995: workers in an

2001; 323: 504–06. integrating world. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

9 Dollar D, Kraay A. Trade, growth, and poverty. Economic J 2004; 30 World Bank. Global economic prospects 2007: managing the next

114: F22–49. wave of globalization. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2007.

10 Kawachi I, Wamala S. Poverty and inequality in a globalizing world. 31 Freeman RB. The challenge of the growing globalization of labor

In: Kawachi I, Wamala S, eds. Globalisation and health. markets to economic and social policy. In: Paus E, ed. Global

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007: 122–37. capitalism unbound: winners and losers from offshore outsourcing.

11 Rodrik, D. How to save globalization from its cheerleaders. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007: 23–40.

Cambridge, MA: John F Kennedy School of Government, Harvard 32 United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the

University; 2007. http://ksghome.harvard.edu/~drodrik/ Caribbean. Social panorama of Latin America 1999–2000.

Saving%20globalization.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008). Santiago: ECLAC, 2000. http://www.cepal.cl/cgi-bin/getProd.

12 Cornia GA. Globalization and health: results and options. asp?xml=/publicaciones/xml/2/6002/P6002.xml&xsl=/dds/tpl-i/

Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79: 834–41. p9f.xsl&base=/tpl-i/top-bottom.xsl (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

13 Chen S, Ravallion M. The developing world is poorer than we 33 Development Indicators and Policy Research Division, Asian

thought, but no less successful in the fight against poverty. Policy Development Bank. Key indicators 2007: inequality in Asia.

research working paper 4703. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2008. Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2007. http://www.adb.org/

http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/ Documents/Books/Key_Indicators/2007/default.asp (accessed

WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2008/08/26/000158349_ Oct 1, 2008).

20080826113239/Rendered/PDF/WPS4703.pdf (accessed 34 Nickell S, Bell B. The collapse in demand for the unskilled and

Oct 1, 2008). unemployment across the OECD. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 1995;

14 Sepehri A, Chernomas R, Akram-Lodhi H. Penalizing patients and 11: 40–62.

rewarding providers: user charges and health care utilization in 35 Wood A. Globalisation and the rise in labour market inequalities.

Vietnam. Health Policy Plan 2005; 20: 90–99. Econ J 1998; 108: 1463–82.

15 United Nations Country Team Viet Nam. Health care financing for 36 Stiglitz J, Charlton A. Common values for the development round.

Viet Nam, discussion paper no.2. Ha Noi: United Nations World Trade Rev 2004; 3: 495–506.

Viet Nam, 2003. 37 Baunsgaard T, Keen M. Tax revenue and (or?) trade liberalization,

16 Woodward D, Simms A. Growth isn’t working: the unbalanced IMF working paper, WP/05/112. Washington, DC: International

distribution of benefits and costs from economic growth. Monetary Fund, 2005. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/

London: New Economics Foundation, 2006. http://www. wp/2005/wp05112.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

neweconomics.org/NEF070625/NEF_Registration070625add. 38 Glenday G. Toward fiscally feasible and efficient trade liberalization.

aspx?returnurl=/gen/uploads/hrfu5w555mzd3f55m2vqwty5020220 Durham, NC: Duke Center for Internal Development, Duke

06112929.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008). University, 2006. http://www.fiscalreform.net/library/pdfs/

17 Nissanke M, Thorbecke E. Channels and policy debate in the Glenday_paper_May_18,_2006_SA_%20rev.pdf (accessed

globalization-inequality-poverty nexus. World Dev 2006; 34: 1338–60. Oct 1, 2008).

18 Shaw M, Davey Smith G, Dorling D. Health inequalities and New 39 Correa CM. Public health and the implementation of the TRIPS

Labour: how the promises compare with real progress. BMJ 2005; agreement in Latin America. In: Blouin C, Drager N, Heymann J,

330: 1016–21. eds. Trade and health: seeking common ground. Montreal:

19 Murray CJ, Laakso T, Shibuya K, Hill K, Lopez AD. Can we achieve McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008: 11–40.

Millennium Development Goal 4? New analysis of country trends 40 Gourinchas P-O, Jeanne O. The elusive gains from international

and forecasts of under-5 mortality to 2015. Lancet 2007; financial integration. Rev Econ Stud 2006; 73: 715–41.

370: 1040–54. 41 Prasad E, Rajan RG. A pragmatic approach to capital account

20 Countdown Working Group. Tracking progress in maternal, liberalization, IZA discussion paper no. 3475. Bonn: Institute for

newborn and child survival: the 2008 report. New York: UNICEF, the Study of Labor, 2008. http://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/

2008. http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/index. dp3475.html (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

php?option=com_content&view=article&id=68&Itemid=61 42 Edison HJ, Levine R, Ricci L, Sløk T. International financial

(accessed Oct 1, 2008). integration and economic growth. J Int Money Finance 2002;

21 Cornia GA, Rosignoli S, Tiberti L. Globalisation and health: 21: 749–76.

pathways of transmission and evidence of impact. Globalization 43 Claessens S, Klingebiel D, Laeven L. Resolving systemic financial

Knowledge Network research papers. Ottawa: Institute of Population crises: policies and institutions. World Bank Policy Research

Health, University of Ottawa, 2008. http://www.globalhealthequity. Working Paper 3377. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2004. http://

ca/electronic%20library/Globalisation%20and%20Health%20Pathw www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/

ays%20of %20Transmission%20and%20Evidence%20of %20Impact IB/2004/09/07/000160016_20040907154538/Rendered/PDF/

%20Final.pdf (accessed Oct 9, 2008). wps3377.pdf (accessed October 9, 2008).

22 Birdsall N. The world is not flat: inequality and injustice in our 44 Hopkins S. Economic stability and health status: evidence from east

global economy, WIDER annual lecture 2005. Helsinki: World Asia before and after the 1990s economic crisis. Health Policy 2006;

Institute for Development Economics Research, 2006. http://www. 75: 347–57.

wider.unu.edu/publications/annual-lectures/en_GB/AL9/_ 45 van der Hoeven R, Lübker M. Financial openness and

files/78121127186268214/default/annual-lecture-2005.pdf (accessed employment: a challenge for international and national

Oct 9, 2008). institutions. Geneva: International Policy Group, International

23 Birdsall N. Globalization at work: life is unfair: inequality in the Labour Office, 2005. http://81.29.96.153/pdf2/gdn_library/annual_

world. Foreign Policy 1998; 111: 76–93. conferences/seventh_annual_conference/Hoeven_Paper_

24 Sutcliffe B. A converging or diverging world? DESA working paper Lunch%20Time%20Session_ILO.pdf (accessed Oct 9, 2008).

no. 2, ST/ESA/2005/DWP/2. New York: United Nations 46 Rodriguez MA. Consequences of capital flight for Latin American

Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2005. http://www. debtor countries. In: Lessard DR, Williamson J, eds. Capital flight

un.org/esa/desa/papers/2005/wp2_2005.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008). and third world debt. Washington, DC: Institute for International

25 Commodity chains and global capitalism. Gereffi G, Economics, 1987: 129–52.

Korzeniewicz M, eds. New York: Praeger, 1994. 47 Helleiner E. Regulating capital flight. Challenge 2001; 44: 19–34.

26 Bair J. Global capitalism and commodity chains: looking back, 48 Ramphal S. Debt has a child’s face. In: UNICEF. The progress of

going forward. Competition Change 2005; 9: 153–80. nations 1999. New York: UNICEF; 1999: 26–29.

27 Dicken P. Global shift: reshaping the global economic map in the 49 George S. A fate worse than debt. London: Penguin, 1988.

21st century, 5th edn. New York: Guilford Press, 2007. 50 King J, Khalfan A, Thomas B. Advancing the odious debt doctrine,

28 Fröbel F, Heinrichs J, Kreye O. The new international division of CISDL working paper. Montreal: Centre for International

labour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980 [original Sustainable Development Law, McGill University, 2003. http://www.

German publication 1977]. cisdl.org/pdf/debtentire.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

www.thelancet.com Vol 372 November 8, 2008 1675

Health Policy

51 Ndikumana L, Boyce JK. Congo’s odious debt: external borrowing 71 Blouin C, Drager N, Heymann J, eds. Trade and health: seeking

and capital flight in Zaire. Dev Change 1998; 29: 195–217. common ground. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008.

52 Mandel S. Odious lending: debt relief as if morals mattered. 72 Garcia FJ. Beyond special and differential treatment.

London: New Economics Foundation, 2006. http://www. Boston Coll Int Comp Law Rev 2004; 27: 291–317.

jubileeresearch.org/news/Odiouslendingfinal.pdf (accessed 73 Collier P. Why the WTO is deadlocked: and what can be done about

Oct 1, 2008). it. The World Econ 2006; 29: 1423–49.

53 Labonté R, Blouin C, Chopra M, et al. Towards health-equitable 74 Sachs JD. The basic economics of scaling up health care in

globalization: rights, regulation and redistribution. Globalization low-income settings. In: Working Party on Biotechnology, ed.

Knowledge Network final report to the Commission on Social Horizontal project on policy coherence: availability of medicines for

Determinants of Health. Ottawa: Institute of Population Health, emerging and infected neglected diseases, DSTI/STP/BIO(2007)6.

University of Ottawa, 2007. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/ Paris: OECD, 2007: 7–23.

resources/gkn_final_report_042008.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008). 75 Pogge T, ed. Freedom from poverty as a human right: who owes

54 Blouin C, Bhushan A, Murphy S, Warren B. Trade what to the very poor? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

liberalization: synthesis paper. Globalization Knowledge Network 76 Ruger JP. Ethics and governance of global health inequalities.

research papers. Ottawa: Institute of Population Health, University J Epidemiol Community Health 2006; 60: 998–1003.

of Ottawa, 2008. http://www.globalhealthequity.ca/

77 Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al, eds. Disease control

electronic%20library/Trade%20Liberalization%20Synthesis%20Pap

priorities in developing countries. Washington, DC: Oxford

er%20Blouin.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

University Press and World Bank, 2006.

55 Working group on IMF programs and health spending. Does the

78 UN Millennium Project. Investing in development: a practical plan

IMF constrain health spending in poor countries? Evidence and

to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. London: Earthscan,

an agenda for action. Washington, DC: Center for Global

2005. http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/

Development, 2007.

MainReportComplete-lowres.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

56 Collier P. The bottom billion: why the poorest countries are failing

79 Brock K, McGee R. Mapping trade policy: understanding the

and what can be done about it. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

challenges of civil society participation. IDS working paper 225.

57 Pogge T. Human rights and human responsibilities. In: De Greiff P, Brighton: Institute for Development Studies, 2004. http://www.ids.

Cronin C, eds. Global justice & transnational politics. Cambridge, ac.uk/ids/bookshop/wp/wp225.pdf#search=%22%20%22%20%20

MA: MIT Press, 2002: 151–95. Mapping%20Trade%20Policy%3A%20Understanding%20the%20C

58 Pogge T. Recognized and violated by international law: the human hallenges%22%22 (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

rights of the global poor. Leiden J Int Law 2005; 18: 717–45. 80 Mandel S. Debt relief as if people mattered: a rights-based approach

59 Pogge T. Severe poverty as a human rights violation. In: Pogge T, ed. to debt sustainability. London: New Economics Foundation, 2006.

Freedom from poverty as a human right: who owes what to the very http://www.neweconomics.org/gen/z_sys_publicationdetail.

poor? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007: 11–53. aspx?pid=223 (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

60 Marchak P. The integrated circus: the new right and the restructuring 81 Williamson J. Democracy and the “Washington consensus”.

of global markets. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991. World Dev 1993; 21: 1329–36.

61 Babb S. The social consequences of structural adjustment: recent 82 Mosley L. Constraints, opportunities, and information: financial

evidence and current debates. Annu Rev Sociology 2005; 31: 199–222. market-government relations around the world. In: Bardhan P,

62 Labonté R, Schrecker T. Globalization and social determinants of Bowles S, Wallerstein M, eds. Globalization and egalitarian

health: the role of the global marketplace (part 2 of 3). Global Health redistribution. New York and Princeton: Russell Sage Foundation

2007; 3: 1–17. and Princeton University Press, 2006: 87–119.

63 Deacon B, Ilva M, Koivusalo M, Ollila E, Stubbs P. Copenhagen 83 Teichman J. Redistributive conflict and social policy in Latin

Social Summit ten years on: the need for effective social policies America. World Dev 2008; 36: 446–60.

nationally, regionally and globally. GASPP Policy Brief 6. 84 Gore C. MDGs and PRSPs: are poor countries enmeshed in a

Helsinki: Globalism and Social Policy Programme, STAKES, 2005. global-local double bind? Global Soc Policy 2004; 4: 277–83.

http://gaspp.stakes.fi/NR/rdonlyres/4F9C6B91-94FD-4042-B781- 85 Woods N, Lombardi D. Uneven patterns of governance: how

3DB7BB9D7496/0/policybrief6.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008). developing countries are represented in the IMF. Rev Int Polit Econ

64 Nygren-Krug H. 25 questions and answers on health and human 2006; 13: 480–515.

rights. Health & human rights publication series issue no. 1. 86 Chowla P, Oatham J, Wren C. Bridging the democratic

Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. http://www.who.int/ deficit: double majority decision making and the IMF. London:

entity/hhr/NEW37871OMSOK.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008). One World Trust and Bretton Woods Project, 2007.

65 Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social 87 Commonwealth heads of government meeting on reform of

determinants of health. Geneva: Commission on Social international institutions. Marlborough House statement on reform

Determinants of Health, World Health Organization, 2007. http:// of international institutions. London: Commonwealth Secretariat,

www.who.int/entity/social_determinants/resources/csdh_ 2008. http://www.thecommonwealth.org/files/180214/FileName/

framework_action_05_07.pdf(accessed Oct 1, 2008). HGM-RII_08_-MARLBOROUGHHOUSESTATEMENTONREFOR

66 Hunt P. Economic, social and cultural rights: The right of everyone to MOFINTERNATIONALINSTITUTIONS.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and 88 Griffith-Jones S. International financial stability and market

mental health. Addendum: mission to the World Trade Organization, efficiency as a global public good. In: Kaul I, Conceição P,

E/CN.4/2004/49/Add.1. Geneva: United Nations Economic and Social LeGoulven K, Mendoza RU, eds. Providing global public

Council Commission on Human Rights; 2004. http://www.unhchr. goods: managing globalization. New York: Oxford University Press

ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/e06a5300f90fa0238025668700518ca4/ for the United Nations Development Programme, 2003: 435–54.

5860d7d863239d82c1256e660056432a/$FILE/G0411390.pdf (accessed

89 Lee K, Koivusalo M, Ollila E, et al. Globalization, global governance

Oct 1, 2008).

and the social determinants of health: a review of the linkages and

67 Kabeer N. Globalisation, labour standards and women’s agenda for action. Globalization Knowledge Network research

rights: dilemmas of collective (in)action in an interdependent papers. Ottawa: Institute of Population Health, University of

world. Feminist Econ 2004; 10: 3–35. Ottawa, 2008. http://www.globalhealthequity.ca/electronic%20

68 Barry C, Reddy SG. International trade and labor standards: library/Globalization%20Global%20Governance%20and%20SD%2

a proposal for linkage. Cornell Int Law J 2006; 39: 545–640. 0of %20H.pdf (accessed Oct 1, 2008).

69 Hammonds R, Ooms G. World Bank policies and the obligation of 90 Kickbusch I, Payne L. Constructing global public health in the 21st

its members to respect, protect and fulfill the right to health. century, prepared for meeting on global health governance and

Health Hum Rights 2004; 8: 27–60. accountability, 2004; Geneva: Kickbusch Health Consult, 2004.

70 Independent Evaluation Office, International Monetary Fund. The http://www.ilonakickbusch.com/global-health-governance/

IMF and aid to sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: IMF, 2007. GlobalHealth.pdf (accessed Oct 9, 2008).

1676 www.thelancet.com Vol 372 November 8, 2008

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- 11 - Fittings For MV Tension LinesDokument15 Seiten11 - Fittings For MV Tension LinesJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- n07v K Eng PDFDokument1 Seiten07v K Eng PDFJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- IMQ CerificateDokument28 SeitenIMQ CerificateJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Attachment 4 The Certificate of DekraDokument1 SeiteAttachment 4 The Certificate of DekraJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Supplier Declaration of Conformity (Sdoc)Dokument2 SeitenSupplier Declaration of Conformity (Sdoc)Jean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Tri-Rated Rev005Dokument2 SeitenTri-Rated Rev005Jean Pierre Goossens100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- polymerinscatalogEN ML 1022 7 PDFDokument16 SeitenpolymerinscatalogEN ML 1022 7 PDFJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- DEIS2006Dokument5 SeitenDEIS2006Jean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- PDFDokument3 SeitenPDFJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Hendrix Molded TieTop InsulatorsDokument5 SeitenHendrix Molded TieTop InsulatorsJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Type Test Approvals: Powering The RegionDokument4 SeitenType Test Approvals: Powering The RegionJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- ZTT MV Power Cable Rev A 20181228Dokument5 SeitenZTT MV Power Cable Rev A 20181228Jean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accessori MT1 PDFDokument108 SeitenAccessori MT1 PDFJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- FaultLocationLowVoltage en 001Dokument36 SeitenFaultLocationLowVoltage en 001Jean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Cisco Webex Meeting Users' GuideDokument3 SeitenCisco Webex Meeting Users' GuideJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- XLPE Versus PVC Technical Write-UpDokument2 SeitenXLPE Versus PVC Technical Write-UpREUBEN7450% (2)

- Dso UeDokument126 SeitenDso UeJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Type Approval ManualDokument19 SeitenType Approval ManualJean Pierre GoossensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Accounting For Non-Profit OrganizationsDokument38 SeitenAccounting For Non-Profit Organizationsrevel_131100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Internship Final Students CircularDokument1 SeiteInternship Final Students CircularAdi TyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ery Systems of South India: BY T.M.MukundanDokument32 SeitenThe Ery Systems of South India: BY T.M.MukundanDharaniSKarthikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dreaded Homework Crossword ClueDokument9 SeitenDreaded Homework Crossword Clueafnahsypzmbuhq100% (1)

- G.R. No. L-6393 January 31, 1955 A. MAGSAYSAY INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, ANASTACIO AGAN, Defendant-AppellantDokument64 SeitenG.R. No. L-6393 January 31, 1955 A. MAGSAYSAY INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, ANASTACIO AGAN, Defendant-AppellantAerylle GuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Blue Umbrella: VALUABLE CODE FOR HUMAN GOODNESS AND KINDNESSDokument6 SeitenBlue Umbrella: VALUABLE CODE FOR HUMAN GOODNESS AND KINDNESSAvinash Kumar100% (1)

- Review Test 4 - Units 7-8, Real English B1, ECCEDokument2 SeitenReview Test 4 - Units 7-8, Real English B1, ECCEΜαρία ΒενέτουNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torrens System: Principle of TsDokument11 SeitenTorrens System: Principle of TsSyasya FatehaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 137684-1980-Serrano v. Central Bank of The PhilippinesDokument5 Seiten137684-1980-Serrano v. Central Bank of The Philippinespkdg1995Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Nationalization of Industries by 1971Dokument2 SeitenNationalization of Industries by 1971alamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deanne Mazzochi Complaint Against DuPage County Clerk: Judge's OrderDokument2 SeitenDeanne Mazzochi Complaint Against DuPage County Clerk: Judge's OrderAdam HarringtonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aquarium Aquarius Megalomania: Danish Norwegian Europop Barbie GirlDokument2 SeitenAquarium Aquarius Megalomania: Danish Norwegian Europop Barbie GirlTuan DaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality & Inspection For Lead-Free Assembly: New Lead-Free Visual Inspection StandardsDokument29 SeitenQuality & Inspection For Lead-Free Assembly: New Lead-Free Visual Inspection Standardsjohn432questNoch keine Bewertungen

- Purpose of Schooling - FinalDokument8 SeitenPurpose of Schooling - Finalapi-257586514Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bishal BharatiDokument13 SeitenBishal Bharatibishal bharatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lea3 Final ExamDokument4 SeitenLea3 Final ExamTfig Fo EcaepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trends and Challenges Facing The LPG IndustryDokument3 SeitenTrends and Challenges Facing The LPG Industryhailu ayalewNoch keine Bewertungen

- JioMart Invoice 16776503530129742ADokument1 SeiteJioMart Invoice 16776503530129742ARatikant SutarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual of Seamanship PDFDokument807 SeitenManual of Seamanship PDFSaad88% (8)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Basic Tax EnvironmentDokument8 SeitenBasic Tax EnvironmentPeregrin TookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business: O' Level Mock Exam - 2021 Paper - 1Dokument9 SeitenBusiness: O' Level Mock Exam - 2021 Paper - 1Noreen Al-MansurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time ClockDokument21 SeitenTime ClockMarvin BrunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iron Maiden - Can I Play With MadnessDokument9 SeitenIron Maiden - Can I Play With MadnessJuliano Mendes de Oliveira NetoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLAT UG Merit List - Rank 10001-15000Dokument100 SeitenCLAT UG Merit List - Rank 10001-15000Bar & BenchNoch keine Bewertungen

- MANUU UMS - Student DashboardDokument1 SeiteMANUU UMS - Student DashboardRaaj AdilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adrian Campbell 2009Dokument8 SeitenAdrian Campbell 2009adrianrgcampbellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of ExplanationDokument2 SeitenAffidavit of ExplanationGerwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qualified Written RequestDokument9 SeitenQualified Written Requestteachezi100% (3)

- LWB Manual PDFDokument1 SeiteLWB Manual PDFKhalid ZgheirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classification and Use of LandDokument5 SeitenClassification and Use of LandShereenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (9)

- The Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityVon EverandThe Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- Workin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherVon EverandWorkin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherNoch keine Bewertungen