Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Delta Module 2 Internal LSA2 BE.2

Hochgeladen von

Светлана КузнецоваCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Delta Module 2 Internal LSA2 BE.2

Hochgeladen von

Светлана КузнецоваCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Helping Higher Level

Learners to write Exam Type

Discursive Essays through

Product Writing

Background essay: LSA2 – Skills - Writing

Number of words: 2523

Date of submission: 24/07/2017

Candidate name: Svetlana Kuznetsova

Centre number: RU006

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 1

Table of Contents

Chapter Page

Title Page 1

Table of Contents 2

1. Introduction 3

2. Analysis 4

2.1 Types of discursive essays

2.2 Features of formal writing 4

2.3 Organisation and paragraphing 5

2.4 Writing sub-skills and assessment scales 5

2.5 Approaches to teaching writing 5

3. Issues for learners and teaching suggestions 9

4. Bibliography 13

5. Appendix 1 14

6. Appendix 2 15

7. Appendix 3 16

8. Appendix 4 17

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 2

1 Introduction

Discursive essays are a feature of many English language examinations

and academic programmes. Even though this type of writing is rarely

practised outside the classroom (Byrne, 1988: 111), there is a need to help

our learners to develop the skills required to maximise their writing exam

score and to succeed in academic programmes (Zemach, 2005: 4).

Despite the fact that most course books and exam handbooks provide

learners with clear sample essays and step-by-step guides on their

completion, most learners still find it extremely difficult to write essays

without due assistance.

I have decided to focus on the topic of discursive essays because I work

in the academic environment and I have to help my students to develop

their essay writing skills for exams or for their further studies in English-

language contexts.

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 3

Analysis

Discursive essays

2.1 Types of essays

Discursive essays are seldom written outside educational or exam

environment. Hyland calls such types of writing “pedagogic” (2003:113).

A discursive essay is a piece of formal writing which discusses a

particular issue, situation or problem from the writer’s personal point of

view (Evans, 1998). There are three main types of discursive essays:

For and Against essays;

Opinion essays;

Problem and Solution essays;

A for and against essay presents both sides of an argument and discusses

points in favour of and against a particular issue. Each point should be

supported by justifications, examples and/or reasons. The writer’s opinion

is usually presented only in the last paragraph (e.g. “Smoking should be

banned in all public places.” Provide arguments for and against the

statement).

An opinion essay presents the writer’s personal opinion regarding the

issue stated. It usually includes only two main elements: statement of

belief and reason (Hinkel, 2004: 11). At more advanced levels of writing,

anticipation of counterarguments may need to be included in a separate

paragraph and then proved to be unconvincing. (e.g. “Shopping centres

have improved the way we shop”. Express your opinion and support it

with reasons and examples).

A problem-solution essay formulates a problem or problems associated

with some particular issue and analyses possible solutions specifying how

they can be achieved and what results can be expected. According to

Hoey (1979), it is one of the most common structures in academic

discourse. (e.g. topic: “What could be done to improve the lives of the

elderly?”)

2.2 Features of formal writing

Since a discursive essay is a formal piece of writing, conventions of

formal writing have to be respected:

Writing should be impersonal (apart from opinion essays), passive

voice and impersonal constructions should be used;

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 4

Overgeneralisations (e.g. All people need……, Everybody

believes……..) should be avoided;

Informal language (colloquialisms, slang and emotive words) and

simplistic vocabulary should be substituted with more neutral

equivalents or/and more advanced formal lexis (e.g. go up –

increase, kids – children, harmful – detrimental);

Formal linking words and discourse markers should be used (e.g.

furthermore, however, nonetheless, moreover, despite the fact that);

Complex sentences with a variety of links and dependent clauses

should be used;

Contractions should be avoided (e.g. haven’t - have not, don’t - do

not, it’s - it is);

Language for texting can not be used (e.g. asap – as soon as

possible, pov – point of view);

2.3 Organisation and paragraphing

Paragraphing reflects the “psychological units” of textual information and

is intended to signal a coherent set of ideas, typically with a topic theme

and supporting details (Grabe & Kaplan:1996: 353). Logical and coherent

organisation of paragraphs is one of the most important components in

essay writing.

A discursive essay usually consists of 4 to 6 paragraphs:

An introductory paragraph states the topic to be discussed

A main body clearly states different points in 2-4 separate

paragraphs;

A conclusion summarises the main points of the essay, restates the

writer’s opinion and does not present any new points;

A paragraph starts with a topic sentence summarising the idea, which is

going to be presented in the paragraph. The topic sentence may identify a

problem, express a need for solution or state an opinion. Supporting

sentences develop the idea presented in the topic sentence and provide

examples and/or reasons that prove the main idea. A paragraph may also

contain a qualifying statement, which modifies the topic statement and

include specific conditions, which make it true.

Appropriate discourse markers should be used to link the paragraphs and

the sentences within the paragraphs.

2.4 Writing sub-skills and assessment scales

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 5

Writing involves encoding of a message of some kind aimed at a certain

reader (Hedge, 2005:11). Good writing acknowledges the reader

(Richards, 1990: 103). As for the discursive essays, the target reader is

usually a teacher or an examiner. What makes this role specific is that the

focus of the target reader’s attention is not the content of the text itself but

assessing how well a student’s final product measures up against a list of

criteria (Burgess, 2005:42).

For instance, the Cambridge writing mark scheme (Cambridge English

Proficiency Handbook for Teachers, 2015:28) includes four criteria:

Content (relevance, target reader);

Communicative achievement (genre, format, register, function,

purpose, ability to hold the reader’s attention and develop ideas);

Organisation (linking words, cohesive devises, organisational

patterns);

Language (vocabulary and grammatical forms: appropriacy and

range):

The criteria are based on writing micro- and macroskills. The table of

subskills for writing production compiled by Brown demonstrates that

exam criteria mirror the sub-skills listed in the table (2001: 342). (See

Appendix 5.)

Since there is a tight time limit at the exams, candidates do not have an

opportunity to draft and re-draft their essays. Therefore, they have to be

able to develop a clear plan of main and supporting statements before

starting to write. Another challenge is the inability to use autocorrecting

programs or to consult dictionaries. Therefore, there are two vital skills

for learners to develop: finding equivalents to words, which learners do

not know, and proofreading.

2.5 Approaches to Teaching Writing

Raimes (1993) identifies three major ways of approaching the task: focus

on form, focus on the writer and focus on the reader. A more common

way of referring to the aforementioned approaches is genre, process and

product writing. When teaching learners to write academic essays, it is

important to find a balance between product and process approaches to

writing (Brown, 2001:337).

Product Writing

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 6

In product writing, teachers present model texts for students to imitate

and adapt. The approach examines texts, either through their formal

surface elements or their discourse structure (Hyland, 2003:7)

According to Pincas (1982: 22), the four stages of product writing are:

1. familiarization

2. controlled writing

3. guided writing

4. free writing

Product writing is the most common approach when teaching academic

and exam-type discursive essays. Students first work on recognising and

identifying key writing structures from model paragraphs or essays. Then

they manipulate the structures in controlled tasks and finally apply them

to their own writing (Zemach, 2005: iv).

The main disadvantage of the approach is that it lacks creativity. The

model is often imposed on the students and they have to fit their writing

into a very rigid framework.

For example, the opinion essay format of the English State Exam in

Russia dictates the candidates the number of paragraphs, ideas and

supporting statements.

Process Writing

The process approach takes the writer rather than the text, as the point of

departure and allows the writer to focus on content and language (Byrne,

1988):

prewriting (reading on the topic and discussing it, conducting

research, generating ideas, planning, free-writing);

drafting (getting started, monitoring of one’s writing, peer

reviewing for content, teacher’s feedback, editing for errors);

revising (writing the final draft and publishing it);

White & Arndt (1991:4) break the process into five stages:

Generating ideas;

Focusing;

Structuring;

Drafting;

Evaluating;

Re-viewing;

It is quite possible for teachers to go to an extreme in emphasising the

process to the extent that the product is ignored. However, such

techniques as generating ideas, structuring and planning can be adopted

from process writing when helping learners to master essay writing.

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 7

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 8

3. Issues for learners and teaching suggestions

Issue 1

Confusing types of essays

My advanced university learners often do not differentiate between the

three main types of essays. Instead of providing arguments for and

against a certain point, some learners start expressing their opinion. In

problem-solution essays, learners may state the problem and then start

describing the reasons for the problem in detail forgetting to provide

solutions.

Suggestion:

I agree with Evans (1998) that the most important point when dealing

with this issue is to teach learners to read the task instructions carefully

and to teach them to plan using the instructions. Learners often rush

straight into writing ignoring what they are actually asked to do in the

task.

The first step to the solution of this issue is asking learners to read

the task carefully and to underline the main instructions (e.g.

present both sides of the argument, give your own opinion, describe

the problem and ways of solving the problem stated). (Appendix 1)

The second step is asking learners to create a table or a mind map

for planning the essay. The table should only contain the

instructions stated in the task.

The third step is to brainstorm ideas and fill them in the table.

After the learners have finished their essays, they go back to the

task with underlined instructions and check their essay putting ticks

above each instruction.

In class, learners may be asked to create an instruction table and then to

check their tables in pairs. They may also be asked to exchange their

essays and do peer check using their tables and task instructions.

Rationale:

When learning to exploit the initial task for planning and organising their

ideas by underlining the main instruction verbs and creating simple

tables, learners have fewer chances of wandering from the instructions

and writing irrelevant points.

Issue 2

Developing a paragraph

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 9

In my experience, adult Russian students preparing for the First

Certificate often do not differentiate between main and supporting ideas

placing the topic sentence after the ones expressing details. Sometimes,

their paragraph consists of restating the main idea in several different

sentences and does not include supporting ideas. It is partially due to the

fact that in Russian, statements often come at the end of the paragraph.

Suggestion:

One of the ways of dealing with this issue is to analyse the

structure of the paragraph and draw the learner’s attention to how

paragraphs are organised (Zemach, 2005). A helpful activity aimed

at differentiating between topic and supporting statements is

provided in Appendix 2. I will ask learners to analyse the structure

of the introductory paragraph and then find three general

statements in a list of jumbled sentences. Students then find three

supporting statements for each general statement. After the students

have done the task and checked with their partner, I will check the

answers at the plenary and ask them to justify their answers.

The same type of activity can easily be arranged by cutting topic

and supporting sentences from sample essays into strips and asking

learners to arrange them in the correct order. Another way of

exploiting sample essays would be to leave blanks in the places of

topic statements and ask learners to think of a topic sentence for

each paragraph.

Rationale 2

By creating a text from isolated sentences, the learners’ attention is drawn

to organising information in paragraphs: from a general statement to

supporting statements. By putting the pieces of the text together, learners

begin to appreciate the structure of discourse and how to develop ideas

through a piece of writing (Hedge, 2005:113). By thinking of a general

statement for a paragraph, students learn to distinguish generalised

umbrella statements from more specific supporting statements.

Issue 3

Not keeping in mind assessment criteria

In my experience, at the beginning of the exam preparation course (First,

Advanced certificates), most higher-level learners are not familiar with

the exam marking scheme. It leads to ignoring some important writing

skills, e.g. holding the target reader’s attention or using less common

lexis. In Russia, learners are used to the idea that the only thing that

matters is grammatical and lexical accuracy and that no one really cares

about the content, paragraph development and the reader’s engagement.

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 10

Suggestion:

Students have to learn to check their essays using the required criteria.

For this, I suggest using sample essays, which can be found in collections

of past papers and handbooks for teachers. (Appendix 3). After

familiarising learners with the criteria, I hand out the sample essay and

ask them to mark each section (content, organisation, language, task

achievement), using the marking scheme. I ask them to provide examples

from the essay to justify their mark. Learners then check their marks in

pairs and discuss them and are then given the examiner’s comments to

compare. This technique should also be used for peer and self-checking

essays.

Rationale:

It is never enough to just introduce the learners to the marking scheme

and then not to use it when working in class and writing at home. By

using the marking scheme, learners become better aware of what they

have to focus on in terms of skills when writing. It is achieved by turning

learners into examiners and making them take an active part in analysing

someone’s work. It helps them to bear in mind all the criteria when

writing.

Issue 4

Using informal lexis

Higher level teenagers use a lot of simplistic and informal lexis when

writing essays for First Certificate or IELTS. It can be explained by the

fact that these learners are only starting to learn to write academic texts

and still have a limited vocabulary. Besides, a discursive essay is a new

format only introduced in high school.

Suggestion:

In order to push our learners to using less common and more formal lexis,

I suggest an activity in Appendix 4. Learners work in pairs. Each learner

gets a copy of an essay. They read their essays and suggest improvements

of simple and informal words (e.g. I think – I believe, etc). They check in

pairs. Since it is an information gap activity, the learners are safe to have

been provided with all the correct answers. I also encourage my learners

to self-check or peer-check essays and suggest synonyms for informal

lexis.

Rationale:

The learners figure out the equivalents of simple lexis by working in pairs

and helping each other with answers. It activates their lexical schema and

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 11

also enriches it if/when they do not know the answer and it is their peer

who tells them a more formal equivalent.

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 12

Bibliography

Brown, H.D, (2001) Teaching by Principles. An interactive approach to

language pedagody. (2nd ed.), White Plains: Longman. (referenced on pp.

6, 8)

Byrne D., (1988) Teaching Writing Skills. Essex: Longman. (referenced

on p. 3)

Cambridge English Proficiency, (2015) Handbook for Teachers,

Cambridge: CUP. (referenced on p. 6)

Evans, V., (1998), Successful Writing Proficiency. Berkshire: Express

Publishing. (referenced on p.3)

Grabe, W. & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Theory & Practice of Writing.

Harlow: Longman (referenced on p. 5)

Hedge T., (2005), Writing. (2d ed.), Oxford: OUP. (referenced on pp.5,

10)

Hinkel, E. (2004), Teaching Academic ESL Writing. Mahwah: Lawrence

Erlbaum. (referenced on p. 4)

Hoey, M., (1983). On the Surface of Discourse. London: George Allen &

Unwin. (referenced on p. 4)

Hyland K., (2003). Second Language Writing. Cambridge: CUP.

(referenced on p.4)

Raimes, A., (1993) Out of the Woods. Emerging Traditions in the

Teaching of Writing. Silberstein 237-260. (referenced on p. 6)

Richards, J.C., (1990) The Language Teaching Matrix. Cambridge: CUP.

(referenced on p. 5)

Zemach D., Rumisek L., (2005), Academic Writing from paragraph to

essay. Oxford: Macmillan. (referenced on pp. 3, 7, 10)

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 13

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 14

Appendix 1

IELTS Past Papers 7, (2009:31). Cambridge: CUP.

Read the task carefully and underline the instructions.

Answer: (discuss both views, give your own opinion, include relevant

examples).

Create a table/mind map that will help you answer all the questions

Plan your essay and fill out the table

Write your essay

Go back to the task, read your essay and tick (V) each instruction

when you see it carried out in your essay.

Sample table:

People are born with talents Any child can be taught to

(music, sports) become a good athlete or

musician

Reason 1/example 1 Reason 1/Example 1

Reason 2/example 2 Reason 2/example 2

My Opinion

Examples to prove it

Self-designed by S_Kuznetsova

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 15

Appendix 2 (Hedge, (2005: 114), Writing. Oxford: OUP)

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 16

Appendix 3 (sample essay and comments. Comments are to be cut)

Certificate of Advanced English Handbook for Teachers (2015: 24), Cambridge: CUP.

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 17

Appendix 4

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 18

Appendix 5

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 19

Table of writing subskills (Brown, 2001:342)

Table 1.1. Microskills for writing

1. Produce graphemes and orthographic patterns.

2. Write at an efficient rate of speed to suit the purpose.

3. Produce an acceptable core of words and use appropriate word order patterns.

4. Use acceptable grammatical systems (e.g. tense, agreement, patterns, rules).

5. Express a particular meaning in different grammatical forms.

6. Use cohesive devices in written discourse.

7. Use rhetorical forms and conventions of written discourse.

8. Accomplish the communicative functions according to form and purpose.

9. Convey links and connections between events (e.g. main idea, supporting idea,

exemplification)

10. Distinguish between literal and implied meanings.

11. Correctly convey culturally specific references in the context of the written text.

12. Develop and use writing strategies (using pre-writing devices, writing the first

draft fluently, re-drafting, editing, using paraphrases and synonyms, etc).

Helping Higher-Level Learners to write Academic Discursive Essays 20

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Academic Presenting and Presentations: Teacher's BookVon EverandAcademic Presenting and Presentations: Teacher's BookBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Curriculum Design in English Language TeachingVon EverandCurriculum Design in English Language TeachingBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- David Lind Pda Experimental EssayDokument8 SeitenDavid Lind Pda Experimental EssayDavid LindNoch keine Bewertungen

- Background EssayLSA2 Given To DeltaDokument8 SeitenBackground EssayLSA2 Given To DeltaAdele Rocheforte100% (6)

- Lsa 2 LPDokument24 SeitenLsa 2 LPemma113100% (6)

- Delta2 PDA RA Stage4Dokument3 SeitenDelta2 PDA RA Stage4Phairouse Abdul Salam50% (4)

- Del Mod2 LSA2 Lesson Plan Reading Elsaid RashadDokument27 SeitenDel Mod2 LSA2 Lesson Plan Reading Elsaid RashadDr.saira Ghazi100% (2)

- Delta lesson plan for showing interestDokument13 SeitenDelta lesson plan for showing interestJulie LhnrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Helping Higher Level Learners To Understand and Use Intensifiers EfficientlyDokument16 SeitenHelping Higher Level Learners To Understand and Use Intensifiers Efficientlyameliahoseason100% (3)

- Task-Based Background AssignmentDokument11 SeitenTask-Based Background Assignmentpandreop50% (2)

- DELTA Module 2 LSA - Teaching CollocationsDokument9 SeitenDELTA Module 2 LSA - Teaching CollocationsJason Malone100% (10)

- Delta2 LSA 2 BackgroundDokument18 SeitenDelta2 LSA 2 BackgroundPhairouse Abdul Salam100% (1)

- Intro To Delta PDADokument8 SeitenIntro To Delta PDAbarrybearer100% (3)

- Yolande Delta PdaDokument6 SeitenYolande Delta Pdasmileysab435950Noch keine Bewertungen

- HL Lsa4 BeDokument17 SeitenHL Lsa4 BeEmily JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDA Part B Experimental Practice AymardDokument11 SeitenPDA Part B Experimental Practice AymardGiuliete Aymard100% (1)

- Phoneme Distinction Techniques for Advanced Spanish LearnersDokument20 SeitenPhoneme Distinction Techniques for Advanced Spanish Learnerswombleworm100% (1)

- Delta2 LSA 1 BackgroundDokument14 SeitenDelta2 LSA 1 BackgroundPhairouse Abdul SalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- D8 Lexis Focus Teaching AssignmentsM2v2Dokument5 SeitenD8 Lexis Focus Teaching AssignmentsM2v2Zulfiqar Ahmad100% (2)

- Delta LSA 3 and 4 RubricDokument3 SeitenDelta LSA 3 and 4 Rubriceddydasilva100% (3)

- Delta2 LSA 4 Lesson PlanDokument23 SeitenDelta2 LSA 4 Lesson PlanPhairouse Abdul Salam100% (2)

- LSA 4 Lexis Essay v2Dokument21 SeitenLSA 4 Lexis Essay v2Melanie Drake100% (1)

- Dogme ELT methodology experiment with lower-level learnersDokument14 SeitenDogme ELT methodology experiment with lower-level learnersBenGreen100% (5)

- Cambridge DELTA PDA Part1 Stage 2Dokument9 SeitenCambridge DELTA PDA Part1 Stage 2Giuliete Aymard100% (2)

- Professional Development Assignment: Reflection and Action: Stage 3Dokument3 SeitenProfessional Development Assignment: Reflection and Action: Stage 3Phairouse Abdul Salam100% (1)

- DELTA Language Skills Assignment SpeakingDokument23 SeitenDELTA Language Skills Assignment Speakingsandrasandia100% (3)

- Lsa 2 BeDokument16 SeitenLsa 2 Beemma113100% (5)

- Lsa 3 BeDokument17 SeitenLsa 3 Beemma113100% (1)

- Cambridge Delta LSA 4 Essay Lexis A FocuDokument19 SeitenCambridge Delta LSA 4 Essay Lexis A FocuSam SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan and Commentary: Delta COURSEDokument7 SeitenLesson Plan and Commentary: Delta COURSEPhairouse Abdul SalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Experimental PracticeDokument24 SeitenSample Experimental PracticeAnna KarlssonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Present Perfect Simple - Getting It Right With Pre-Intermediate LearnersDokument11 SeitenThe Present Perfect Simple - Getting It Right With Pre-Intermediate Learnersm mohamedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Background EssayDokument18 SeitenBackground EssayEdward Green100% (3)

- Lsa4 Evaluation FinalDokument2 SeitenLsa4 Evaluation FinalDragica Zdraveska100% (1)

- Template For The Cambridge DELTA LSA Background Essay and Lesson PlanDokument7 SeitenTemplate For The Cambridge DELTA LSA Background Essay and Lesson Planmcgwart89% (9)

- Lsa2 LP LexisDokument26 SeitenLsa2 LP LexisBurayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Online Delta Course Module One Unit 2 Language AnalysisDokument14 SeitenOnline Delta Course Module One Unit 2 Language AnalysisSamina Shamim100% (2)

- DELTA2 - LSA 1 - 5aDokument8 SeitenDELTA2 - LSA 1 - 5aPhairouse Abdul Salam100% (1)

- LSA 4 GuidelinesDokument13 SeitenLSA 4 GuidelinesDragica Zdraveska100% (1)

- Delta Module 3: Teaching Exam ClassesDokument32 SeitenDelta Module 3: Teaching Exam ClassesArchie Pellago100% (2)

- Module 3 DELTA One To OneDokument16 SeitenModule 3 DELTA One To OnePhairouse Abdul Salam100% (3)

- Engaging adolescent learnersDokument35 SeitenEngaging adolescent learnersMuhammad Ali Khalaf80% (15)

- Experimental Teaching Technique AssignmentDokument3 SeitenExperimental Teaching Technique Assignmenteddydasilva100% (1)

- DELTA2 - LSA 2 - 5aDokument6 SeitenDELTA2 - LSA 2 - 5aPhairouse Abdul Salam100% (2)

- DELTA Module Three Manual 2020Dokument13 SeitenDELTA Module Three Manual 2020lolloNoch keine Bewertungen

- DELTA M2+3 Book ListDokument2 SeitenDELTA M2+3 Book ListphairouseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top-down bottom-up lesson analyzes news reportsDokument20 SeitenTop-down bottom-up lesson analyzes news reportsKasia MNoch keine Bewertungen

- GiulieteAymard - LSA2 - Using The Passive Voice at C1 LevelDokument11 SeitenGiulieteAymard - LSA2 - Using The Passive Voice at C1 LevelGiuliete AymardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge Delta: Focus On Teaching & Learning GrammarDokument12 SeitenCambridge Delta: Focus On Teaching & Learning GrammarKarenina ManzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spirit of DogmeDokument5 SeitenSpirit of DogmesnowpieceNoch keine Bewertungen

- High Frequency Phrasal Verbs For Elementary Level StudentsDokument14 SeitenHigh Frequency Phrasal Verbs For Elementary Level StudentsKhara Burgess100% (1)

- How To Prepare For Cambridge Delta Module Two ELTCloudDokument47 SeitenHow To Prepare For Cambridge Delta Module Two ELTCloudAlonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delta2 LSA 4 BackgroundDokument25 SeitenDelta2 LSA 4 BackgroundPhairouse Abdul Salam100% (4)

- DELTA2 - LSA 3 - 5aDokument11 SeitenDELTA2 - LSA 3 - 5aPhairouse Abdul Salam100% (1)

- LSA3 Pron FinalDokument12 SeitenLSA3 Pron FinalJamie PetersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Listening LSA1 Background EssayDokument15 SeitenListening LSA1 Background EssayBen Eichhorn100% (2)

- Experimental Practice in ELT: Walk on the wild sideVon EverandExperimental Practice in ELT: Walk on the wild sideBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- Balloon DebateDokument5 SeitenBalloon DebateСветлана КузнецоваNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bloom's QuicksheetsDokument6 SeitenBloom's QuicksheetsMatthew CallisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Science Through English - A CLIL Approach PDFDokument29 SeitenTeaching Science Through English - A CLIL Approach PDFMara Alejandra Franco PradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching EFL To Children The Delight of BeingDokument11 SeitenTeaching EFL To Children The Delight of BeingСветлана КузнецоваNoch keine Bewertungen

- Celta Assignment SampleDokument3 SeitenCelta Assignment SampleСветлана Кузнецова100% (1)

- (E-Book) Teaching English To ChildrenDokument119 Seiten(E-Book) Teaching English To Childrenemmaromera95% (41)

- Dynamic English Grammar and Composition: Book-9Dokument16 SeitenDynamic English Grammar and Composition: Book-9Nhâm An ThiênNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide To Contemporary Music in Belgium 2012Dokument43 SeitenGuide To Contemporary Music in Belgium 2012loi100% (1)

- Anna Lyons Analysis of Disney's Black and White Romance Short Film PapermanDokument5 SeitenAnna Lyons Analysis of Disney's Black and White Romance Short Film PapermanBrittan Ian PeterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modals Extra PracticeDokument16 SeitenModals Extra Practicekristen.study99Noch keine Bewertungen

- Integrated Language Environment: AS/400 E-Series I-SeriesDokument15 SeitenIntegrated Language Environment: AS/400 E-Series I-SeriesrajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anita Desai - in Custody PDFDokument68 SeitenAnita Desai - in Custody PDFArturoBelano958% (12)

- EC - A2 - Tests - Unit 3 Answer Key and ScriptDokument3 SeitenEC - A2 - Tests - Unit 3 Answer Key and ScriptEdawrd Smith50% (2)

- DLL Quarter 4 Week 6 Geneva MendozaDokument37 SeitenDLL Quarter 4 Week 6 Geneva MendozaGeneva MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Papers GuideDokument34 SeitenLiterature Papers Guidetetsuko_mochiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be The Best You. Be The Best For Your StudentsDokument16 SeitenBe The Best You. Be The Best For Your StudentsPrithviraj ThakurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appropriateness of Mother-Tongue Based Multi-Lingual Education (MTB-MLE) in Urban Areas A Synthesis StudyDokument10 SeitenAppropriateness of Mother-Tongue Based Multi-Lingual Education (MTB-MLE) in Urban Areas A Synthesis StudyIjsrnet EditorialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Radiologist Resume - Komathi SDokument3 SeitenRadiologist Resume - Komathi SGloria JaisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammar Lessons - Aleph With BethDokument106 SeitenGrammar Lessons - Aleph With BethDeShaunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written Expression QuestionsDokument10 SeitenWritten Expression Questionsaufa faraNoch keine Bewertungen

- C Programming - Question Bank PDFDokument21 SeitenC Programming - Question Bank PDFSambit Patra90% (10)

- Esb Dec 2008Dokument17 SeitenEsb Dec 2008Eleni KostopoulouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Intelligence Suite Enterprise Edition Release NotesDokument112 SeitenBusiness Intelligence Suite Enterprise Edition Release NotesMadasamy MurugaboobathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ArabicDokument113 SeitenArabicLenniMariana100% (12)

- DIRECT and Indirect Word Doc PDF 1636913196542Dokument6 SeitenDIRECT and Indirect Word Doc PDF 1636913196542md.muzzammil shaikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Vocabulary of Art: Elements, Principles and TechniquesDokument6 SeitenThe Vocabulary of Art: Elements, Principles and TechniquesApolinaria Apolinaire GhitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Luo - Plo3 - Edte606 Language Pedagogy Mastery AssignmentDokument26 SeitenLuo - Plo3 - Edte606 Language Pedagogy Mastery Assignmentapi-549590947Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Drama PDFDokument8 SeitenIntroduction To Drama PDFSaleh AljumahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Singular and Plural English Verbs ChartDokument1 SeiteSingular and Plural English Verbs Chartrizqi febriNoch keine Bewertungen

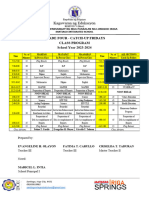

- Class Program G4 Catch UpDokument1 SeiteClass Program G4 Catch UpEvangeline D. HertezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammar Test 1-2 TestDokument4 SeitenGrammar Test 1-2 TestSimeon StaykovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive StylisticsDokument4 SeitenCognitive StylisticsTamoor AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Present Perfect Time ExpressionsDokument4 SeitenPresent Perfect Time ExpressionsAldo Jei IronyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Analysis of Oprah Winfrey Talk ShowDokument10 SeitenThe Analysis of Oprah Winfrey Talk ShowIris Kic LemaićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Possible Non-Indo-European Elements in HittiteDokument16 SeitenPossible Non-Indo-European Elements in HittitelastofthelastNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quranic DictionaryDokument3 SeitenQuranic DictionaryIrshad Ul HaqNoch keine Bewertungen