Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Patofisiologi Krisis Hipertensi

Hochgeladen von

Afriodita Ary PratiwiOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Patofisiologi Krisis Hipertensi

Hochgeladen von

Afriodita Ary PratiwiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hypertensive elderly); however, men are affected approximately two times

more frequently than women.9–12

crisis—pathophysiology, Hypertensive urgencies are hypertensive crises associated

with severe elevations in BP without progressive target-organ

dysfunction.11,13–19 The majority of these patients present as

initial evaluation, and noncompliant or inadequately treated hypertensive individuals,

management often with little or no evidence of target-organ damage. Hy-

pertensive emergencies are hypertension crises characterized

by severe elevations in BP > 180/120 mmHg complicated by

Mukesh Singh, MBBS MD MRCP evidence of impending or progressive target-organ dysfunction.

They require immediate BP reduction (not necessarily to normal

levels) to prevent or limit target-organ damage.20,21

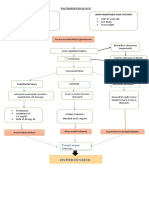

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

BACKGROUND

Acute severe hypertension can develop de novo or can compli-

The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, cate underlying essential or secondary hypertension. The exact

Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recently mechanism of hypertensive crisis is not known but the rapidity

classified hypertension according to the degree of blood pres- of onset suggests a triggering factor superimposed on pre-existing

sure elevation. Stage 1 patients have systolic blood pressure hypertension.22 Most accepted hypothesis is shown in Figure 1.

(SBP) of 140–159 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of Under normal circumstances, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

90–99 mmHg. Stage 2 patients have SBP of 160–179 mmHg or system plays a central role in the regulation of normal BP

DBP of 100–109 mmHg, whereas stage 3 corresponds to SBP of homeostasis.23 Overproduction of renin by the kidney stimu-

180 mmHg or greater or DBP of 110 mmHg or greater. Stage 3 lates the formation of angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor.

hypertension has also been called severe hypertension or ac- Consequently, both peripheral vascular resistance and BP in-

celerated hypertension.1 Although chronic hypertension is an crease. Hypertensive crisis is thought to be initiated by an

established risk factor for cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and abrupt increase in systemic vascular resistance likely related to

renal disease, acute elevations in BP can result in acute end- humoral vasoconstrictors.24,25 In the hypertensive crises state,

organ damage with significant morbidity. Prompt recognition, amplification of renin system activity occurs, leading to vascular

evaluation, and appropriate treatment of these conditions are injury, tissue ischemia, and further overproduction of renin-

crucial to prevent permanent end-organ damage. angiotensin. This vicious cycle contributes to the pathogenesis

Hypertensive crisis refers to a syndrome characterized by of hypertensive crises. The pathophysiologic link between the

severe acute elevations in blood pressure associated with im-

minent risks to the patient.2,3 Although not specifically ad-

dressed in the JNC-7 report, patients with a SBP > 179 mmHg Abrupt increase in systemic Humoral

or a DBP > 109 mmHg are usually considered to be having a vascular resistance vasoconstrictors

“hypertensive crisis.” The absolute level of BP itself is less impor-

tant, as acute increases in BP of even modest degree can lead to

↑ BP

critical target organ damage in previously normotensive patients

and those with certain medical conditions like acute myocardial

infarction or aortic dissestion.4

Prior to the introduction of antihypertensive medications, ↑ Mechanical stress Endothelial injury

approximately 7% of hypertensive patients had a hypertensive

emergency.5 Currently, it is estimated that ∼1% of patients with

hypertension will, at some point, develop a hypertensive crisis.6,7

• ↑ Vascular permeability

It is a common medical problem and accounts for 27.5% of all • Platelet activation

medical emergencies presenting to the emergency department.8 • Activation of

The epidemiology of hypertensive crises is similar to that of coagulation cascade

• Fibrin deposition

hypertension (i.e. higher among African-Americans and the

Ischemia

Department of Cardiology, Chicago Medical School & Mount Sinai

Release of vasoactive

Hospital.

mediators

Correspondence: Dr. Mukesh Singh, 1500 S California Avenue, Chicago,

IL-60608, United States. E-mail: drmukeshsingh@yahoo.com Figure 1 Pathophysiology of hypertensive crisis.

JICC Vol 1 Issue 1 36

Hypertensive crisis—pathophysiology, initial evaluation, and management

Table 1 Initial evaluation and management of hypertensive crisis.

A) Hypertensive urgency

• BP usually > 180/110 mmHg

• Presents with headache, dyspnea, edema

• Observe for 4–6 hours, oral agents for BP control and follow-up evaluation within 24 hours

B) Hypertensive emergency

• BP usually > 220/140 mmHg

• Presents with dyspnea, chest pain, dysarthria, focal neurological signs, altered sensorium, pulmonary edema, encephalopathy, stroke, renal failure

• Admit to ICU, investigate for associated condition, and start parenteral antihypertensive therapy

renin system and hypertensive crises has been established by Initial objective evaluation should include a metabolic panel

demonstrating that this process can be arrested when the renin- to assess electrolytes, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen; a

angiotensin system is interrupted either pharmacologically complete blood count (and smear if microangiopathic hemolytic

(i.e., angiotensin converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor, beta-blocker, anemia is suspected); a urinalysis to look for proteinuria or mi-

or type 1 angiotensin receptor antagonist) or by removal of an croscopic hematuria; and an electrocardiogram to assess for car-

ischemic kidney.23,26,27 Other factors induced by excess renin- diac ischemia.33 Supportive radiographic studies such as a chest

angiotensin include pro-inflammatory cytokines and vascular radiograph in a patient with dyspnea or chest pain or a head

cell adhesion molecules, which may contribute to the vascular computed tomography scan in a patient with neurologic symp-

sequelae and target organ damage.28–30 toms should be obtained in the appropriate clinical scenario. In

patients presenting with pulmonary edema it is important to ob-

tain an echocardiogram to distinguish between diastolic dysfunc-

EVALUATION AND INITIAL MANAGEMENT tion, transient systolic dysfunction, or mitral regurgitation.34

Hypertensive crises share all the pathophysiologic mecha-

Patients with hypertensive emergency usually present for eval- nisms and target organ complications (MI, stroke, renal failure)

uation as a result of a new symptom complex related to their similar to patients with milder forms of high BP and, thus, to-

elevated BP. Patient triage and physician evaluation should gether can be viewed as part of the spectrum of hypertensive

proceed expeditiously to prevent ongoing end organ damage. A diseases. BP is reduced, in the hypertensive crises and in the

focused medical history that includes the use of any prescribed chronic forms of hypertension, by the same drugs that interrupt

or over-the-counter medications should be obtained. If the pa- relevant pathophysiologic mechanisms. An algorithm for initial

tient is known to have hypertension, their hypertensive history, management of hypertensive crisis is given in Table 1.

previous control, current antihypertensive medications with The majority of patients in whom severe hypertension

dosing, compliance, and time from last dose are important facts (SBP > 160 mmHg, DBP > 100 mmHg) is identified on initial eval-

to know as subsequent treatment decisions are made. Also use uation will not have evidence of end organ damage and thus

of recreational drugs (amphetamines, cocaine, and phencyclidine) have hypertensive urgency. As no acute end organ damage is

should be considered. Confirmation of the blood pressure present, these patients may present for evaluation of another

should be obtained in both arms by a physician using a BP cuff complaint, and the elevated blood pressure may represent an

of appropriate size. Patients with long-standing hypertension acute recognition of chronic hypertension. In these patients,

may tolerate SBP > 200 mmHg or DBP > 150 mmHg without de- utilizing oral medications to lower the blood pressure gradually

veloping clinical signs or symptoms of end organ damage; over 24–48 hours is the best approach to management.35–37 In

however, in postoperative or pregnancy patients a much lower fact, rapid reduction of blood pressure may be associated with

but more rapidly progressive increase in blood pressure may significant morbidity in hypertensive urgency because of a

result in end organ damage. The physical examination should rightward shift in the pressure/flow auto-regulatory curve in

attempt to identify evidence of end organ damage by assessing critical arterial beds (cerebral, coronary, and renal).38 Rapid

pulses in all extremities, auscultating the lungs for evidence of correction of severely elevated blood pressure below the au-

pulmonary edema, the heart for murmurs or gallops, the renal toregulatory range of these vascular beds can result in a marked

arteries for bruits, and performing a focused neurologic and reduction in perfusion causing ischemia and infarction.39–42

fundoscopic examination. Headache and altered levels of con- Therefore, although the blood pressure must be reduced in these

sciousness are the usual manifestations of hypertensive enceph- patients, it must be lowered in a slow and controlled fashion to

alopathy.31,32 Focal neurological findings, especially lateralizing prevent this impaired autoregulatory hypoperfusion problem.

signs, are uncommon in hypertensive encephalopathy, being Patients with a hypertensive emergency should be managed in

more suggestive of a cerebrovascular accident. Subarachnoid an intensive care unit with close monitoring and are best man-

hemorrhage should be considered in patients with a sudden aged with a continuous infusion of a short-acting, titratable anti-

onset of a severe headache. hypertensive agent. Because of unpredictable pharmacodynamics,

JICC Vol 1 Issue 1 37

sh Singh

Table 2 Hypertensive emergencies.

A) Aortic dissection

• Beta blocker and nitroprusside

• Reduce to systolic BP < 120 mmHg over few minutes

B) Myocardial infarction

• Nitroglycerine

• Titrate to improvement of ischemic symptoms

C) Pulmonary edema

• Nitroglycerine

• 10–15% reduction leads to improvement in symptoms

D) Hypertensive encephalopathy

• Fenoldopam/nicardipine/nitroprusside

• 25% reduction over 2–3 hours

A) Acute stroke

• Do not attempt to reduce BP unless > 200/110 mmHg

• Keep BP > 180/100 mmHg

• For stroke after thrombolysis aim to keep BP < 180/105 mmHg for first 24 hours and then target < 140/90 mmHg

F) Subarachnoid hemorrhage

• Nimodipine

• 25% reduction over 2–3 hours

G) Acute renal failure

• Fenoldopam

• Up to 25% reduction over 1–12 hours

H) Eclampsia/Pre-eclampsia

• Magnesium sulfate and hydralazine or methyldopa

• Target diastolic BP < 90 mmHg

I) Clonidine withdrawal

• Reinstitute clonidine

J) Cocaine induced hypertensive crisis

• Clonidine

the sublingual and intramuscular route should be avoided. elevated BP with evidence of end organ damage should prompt

For those patients with the most severe clinical manifestations initiation of timely and appropriate antihypertensive regimens

or with the most labile blood pressure, intra-arterial blood pres- to prevent on-going end organ damage. There are multiple

sure monitoring may be prudent. Although there are no con- therapeutic options for hypertensive emergencies; and, the type

crete guidelines as to the degree of desired blood pressure of emergency and the individual patient are the most important

reduction, a reasonable goal for most hypertensive emergen- factors in the decision. ♦

cies is to lower the DBP to 100 mmHg (or to reduce the mean

arterial pressure by 20–25%) over a period of minutes

to hours.43 A list of conditions associated with hypertensive REFERENCES

emergency and the durgs of choice is given in Table 2. 1. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint

National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment

of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 Report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72.

CONCLUSION 2. Nolan CR III, Linas SL. Malignant hypertension and other hyperten-

sive crises. In: Diseases of the Kidney, 5th ed. Schrier RW, Gottschalk

Hypertensive crisis represents a serious medical condition with CW, eds. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. 1993:1555–643.

the potential for permanent end organ damage and significant 3. Mann SI, Atlas SA. Hypertensive emergencies. In: Hypertension:

morbidity and mortality. No data currently exists to show im- Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, 2nd ed. Laragh IH,

mediate benefit from acutely lowering BP in asymptomatic pa- Brenner BM, eds. New York: Raven, 1995:3009–22.

tients with severe hypertension, but data do suggest that an 4. Kitiyakara C, Guzman NJ. Malignant hypertension and hypertensive

aggressive approach may be harmful. However, recognition of emergencies. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:133–42.

JICC Vol 1 Issue 1 38

Hypertensive crisis—pathophysiology, initial evaluation, and management

5. Laragh J. Laragh’s lessons in pathophysiology and clinical pearls for 24. Ault MJ, Ellrodt AG. Pathophysiological events leading to the end-

treating hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2001;14:837–54. organ effects of acute hypertension. Am J Emerg Med 1985;3:10–5.

6. McRae Jr RP, Liebson PR. Hypertensive crisis. Med Clin North Am 25. Wallach R, Karp RB, Reves JG, et al. Pathogenesis of paroxysmal hyper-

1986;70:749–67. tension developing during and after coronary bypass surgery: a study

7. Vidt DG. Current concepts in treatment of hypertensive emergencies. of hemodynamic and humoral factors. Am J Cardiol 1980;46:559–65.

Am Heart J 1986;111:220–5. 26. Laragh JH, Ulick S, Januszewicz V, Kelly WG, Lieberman S. Electrolyte

8. Zampaglione B, Pascale C, Marchisio M, Cavallo-Perin P. Hypertensive metabolism and aldosterone secretion in benign and malignant

urgencies and emergencies: prevalence and clinical presentation. hypertension. Ann Intern Med 1960;53:259–72.

Hypertension 1996;27:144–7. 27. Case DB, Atlas SA, Sullivan PA, Laragh JH. Acute and chronic treat-

9. Lip GY, Beevers M, Potter JF, et al. Malignant hypertension in the ment of severe and malignant hypertension with the oral angiotensin

elderly. QJM 1995;88:641–7. converting enzyme inhibitor captopril. Circulation 1981;64:765–71.

10. Smith CB, Flower LW, Reinhardt CE. Control of hypertensive emergen- 28. Vaughan C, Dealnty N. Hypertensive emergencies. Lancet 2000;356:

cies. Postgrad Med 1991;89:111–6. 411–7.

11. Kaplan NM. Treatment of hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. 29. Funakoshi Y, Ichiki T, Ito K, et al. Induction of interleukin-6 expression

Heart Dis Stroke 1992;1:373–8. by angiotensin II in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension

12. Bennett NM, Shea S. Hypertensive emergency: case criteria, sociode- 1999;34:118–25.

mographic profile, and previous care of 100 cases. Am J Public Health 30. Han Y, Runge MS, Brasier AR. Angiotensin II induces interleukin-6

1988;78:636–40. transcription in vascular smooth muscle cells through pleiotropic

13. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh Report of the Joint activation of nuclear factor-B transcription factors. Circ Res 1999;84:

National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and 695–703.

Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206–52. 31. Garcia JYJ, Vidt DG. Current management of hypertensive emergen-

14. Joint National Committee on Detection Evaluation and Treatment of cies. Drugs 1987;34:263–78.

High Blood Pressure, National High Blood Pressure Education 32. Hickler RB. Hypertensive emergency: a useful diagnostic category.

Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint Am J Public Health 1988;78:623–4.

National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High 33. Vidt DG. Current concepts in treatment of hypertensive emergencies.

Blood Pressure, JNC-7 (complete report). NIH Publication No. 04-5230. Am Heart J 1986;111:220–5.

Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Health 34. Gandhi SK, Powers JC, Nomeir AM, et al. The pathogenesis of acute

Information Center, 2004. pulmonary edema associated with hypertension. N Engl J Med 2001;

15. Gifford Jr RW. Management of hypertensive crises. JAMA 1991;266: 344:17–22.

829–35. 35. Ferguson RK, Vlasses PH. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies.

16. Calhoun DA, Oparil S. Treatment of hypertensive crisis. N Engl J Med JAMA 1986;255:1607–13.

1990;323:1177–83. 36. Reuler JB, Magarian GJ. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies:

17. Rahn KH. How should we treat a hypertensive emergency? Am J definition, recognition, and management. J Gen Intern Med 1988;3:

Cardiol 1989;63:48–50C. 64–74.

18. Reuler JB, Magarian GJ. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies: 37. Kaplan NM. Treatment of hypertensive emergencies and urgencies.

definition, recognition, and management. J Gen Intern Med 1988; Heart Dis Stroke 1992;1:373–8.

3:64–74. 38. Strandgaard S, Olesen J, Skinhoj E, Lassen NA. Autoregulation of

19. Ferguson RK, Vlasses PH. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. brain circulation in severe arterial hypertension. Br Med J 1973;1:

JAMA 1986;255:1607–13. 507–10.

20. Greene CS, Gretler DD, Cervenka K, et al. Cerebral blood flow during 39. Prisant LM, Carr AA, Hawkins DW. Treating hypertensive emergen-

the acute therapy of severe hypertension with oral clonidine. Am J cies. Controlled reduction of blood pressure and protection of target

Emerg Med 1990;8:293–6. organs. Postgrad Med 1990;93:92–6.

21. Houston MC. The comparative effects of clonidine hydrochloride and 40. Bannan LT, Beevers DG, Wright N. ABC of blood pressure reduction.

nifedipine in the treatment of hypertensive crises. Am Heart J 1988; Emergency reduction, hypertension in pregnancy, and hypertension

115:152–9. in the elderly. Br Med J 1980;281:1120–2.

22. Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. 41. Bertel O, Marx BE, Conen D. Effects of antihypertensive treatment on

Chest 2007;131:1949–62. cerebral perfusion. Am J Med 1987;82:29–36.

23. Laragh JH, Sealey JE. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and 42. Reed WG, Anderson RJ. Effects of rapid blood pressure reduction on

the renal regulation of sodium and potassium and blood pressure cerebral blood flow. Am Heart J 1986;111:226–8.

homeostasis. In: Handbook of Renal Physiology, Windhager EE, ed. 43. Kitiyakara C, Guzman NJ. Malignant hypertension and hypertensive

New York: Oxford University Press, 1992:1409–541. emergencies. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:133–42.

JICC Vol 1 Issue 1 39

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Simple Guide to Parathyroid Adenoma, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsVon EverandA Simple Guide to Parathyroid Adenoma, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renal MedsurgDokument14 SeitenRenal MedsurgCliff Lois ╭∩╮⎷⎛⎝⎲⏝⏝⎲⎠⎷⎛╭∩╮ Ouano100% (1)

- Diabetic NephropathyDokument5 SeitenDiabetic NephropathydnllkzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Type 1 and PDFDokument12 SeitenThe Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Type 1 and PDFasmawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathophysiology of Portal HYPERTENSION PDFDokument11 SeitenPathophysiology of Portal HYPERTENSION PDFCamilo VidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infective Endocarditis CaseDokument3 SeitenInfective Endocarditis CaseMershen GaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Danger Signs of PregnancyDokument3 SeitenDanger Signs of PregnancyNesly Khyrozz LorenzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intracerebral HemorrageDokument13 SeitenIntracerebral HemorrageChristian JuarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- DB31 - Pathophysiology of Diabetes Mellitus and HypoglycemiaDokument5 SeitenDB31 - Pathophysiology of Diabetes Mellitus and HypoglycemiaNeil Alcazaren かわいいNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest InjuryDokument4 SeitenChest InjuryFRANCINE EVE ESTRELLANNoch keine Bewertungen

- RevisionDokument17 SeitenRevisionMatt RenaudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manuscript Case Report Addison's Disease Due To Tuberculosis FinalDokument22 SeitenManuscript Case Report Addison's Disease Due To Tuberculosis FinalElisabeth PermatasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept MapDokument4 SeitenConcept MapChelsyann FerolinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- EMERGENCY DRUGS: A Drug StudyDokument8 SeitenEMERGENCY DRUGS: A Drug StudyShaine WolfeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Guide 1 - Leadership and FollowershipDokument11 SeitenStudy Guide 1 - Leadership and FollowershipMark Vincent GallenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSN4D-SG2 DM Type2Dokument201 SeitenBSN4D-SG2 DM Type2Charisse CaydanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 NCP Spinal Cord InjuryDokument21 Seiten12 NCP Spinal Cord InjuryICa MarlinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypertensive Crisis - PathophysiologyDokument1 SeiteHypertensive Crisis - Pathophysiologyaaron tabernaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomy and Phsyiology of MeningococcemiaDokument2 SeitenAnatomy and Phsyiology of MeningococcemiaKevin Comahig100% (1)

- Generic Name T Rade Name Classification Diltiazem Cardizem Antianginals, AntiarrhythmicsDokument1 SeiteGeneric Name T Rade Name Classification Diltiazem Cardizem Antianginals, AntiarrhythmicsChristopher LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anaphylactic ReactionDokument9 SeitenAnaphylactic ReactionZahir Jayvee Gayak IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Myocardialinfarction 150223043527 Conversion Gate02 PDFDokument22 SeitenMyocardialinfarction 150223043527 Conversion Gate02 PDFBhavika Aggarwal100% (1)

- Lab 5 Diabetes InsipidusDokument6 SeitenLab 5 Diabetes InsipidusLisa EkapratiwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ParacetamolDokument2 SeitenParacetamolsleep whatNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHH Drug Study Week 3Dokument21 SeitenCHH Drug Study Week 3maryxtine24Noch keine Bewertungen

- AcetaminophenDokument2 SeitenAcetaminophendrugcardref100% (1)

- Drug StudyDokument5 SeitenDrug StudyJanine Erika Julom BrillantesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacologic Management: BleomycinDokument1 SeitePharmacologic Management: BleomycinKim ApuradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renal Concept MapDokument8 SeitenRenal Concept MapXtine CajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Page 17 ACUTE PAIN Related To Joint Stiffness Secondary To Aging.Dokument3 SeitenPage 17 ACUTE PAIN Related To Joint Stiffness Secondary To Aging.Senyorita KHayeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liver Cirosis Case StudyDokument18 SeitenLiver Cirosis Case StudyDaniel LaurenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dengue NCPDokument3 SeitenDengue NCPingridNoch keine Bewertungen

- CefalexinDokument1 SeiteCefalexinJohanna LehannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EAMC DFCM OPD Charting Guidelines As of March 2022Dokument19 SeitenEAMC DFCM OPD Charting Guidelines As of March 2022Adrian MaterumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care For MeaslesDokument5 SeitenNursing Care For MeaslesChristian Eduard de DiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathophysiology of Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDokument1 SeitePathophysiology of Peptic Ulcer DiseaseJhade RelletaNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Manila (Formerly City College of Manila) Mehan Gardens, ManilaDokument8 SeitenCity of Manila (Formerly City College of Manila) Mehan Gardens, Manilaicecreamcone_201Noch keine Bewertungen

- Drug StudyDokument4 SeitenDrug StudyJunel Paolo SilvioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quiz LeukemiaDokument4 SeitenQuiz LeukemiaHanna La MadridNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Presentation About Calculous CholecyctitisDokument23 SeitenCase Presentation About Calculous CholecyctitiskarenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avigan PDFDokument6 SeitenAvigan PDFSoheil JafariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study PneumoniaDokument14 SeitenCase Study PneumoniaJester GalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- IVABRADINEDokument9 SeitenIVABRADINEIvan Darío Castillo OrozcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meningitis Pathophysiology PDFDokument59 SeitenMeningitis Pathophysiology PDFpaswordnyalupa100% (1)

- Ulcerative ColitisDokument9 SeitenUlcerative Colitiskint manlangitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Study FUROSEMIDE (Eugene San)Dokument2 SeitenDrug Study FUROSEMIDE (Eugene San)Ana LanticseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cyclophosphamide For Injection, USPDokument2 SeitenCyclophosphamide For Injection, USPemilia candraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Study (AGN)Dokument10 SeitenDrug Study (AGN)kristineNoch keine Bewertungen

- CNS Stimulants DrugsDokument20 SeitenCNS Stimulants DrugsDavid Jati MarintangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Scenarios: Scenario 1Dokument2 SeitenCase Scenarios: Scenario 1Kym RonquilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dosage & Frequency Mechanism of Action Indication Contraindication Adverse Effect Nursing Responsibility Rivotril ClassificationDokument5 SeitenDosage & Frequency Mechanism of Action Indication Contraindication Adverse Effect Nursing Responsibility Rivotril ClassificationJenyl BajadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetic Nephropathy - Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, EtiologyDokument6 SeitenDiabetic Nephropathy - Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, EtiologyIrma KurniawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clonidine Hydro ChlorideDokument4 SeitenClonidine Hydro Chlorideapi-3797941100% (1)

- Atropine: Drug Study: NCM 106 PharmacologyDokument6 SeitenAtropine: Drug Study: NCM 106 PharmacologyKevin RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate: Therese M. Chapman, Jane K. Mcgavin and Stuart NobleDokument12 SeitenTenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate: Therese M. Chapman, Jane K. Mcgavin and Stuart NobleBagusHibridaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Correlation Between Disease Stage and Pulmonary Edema Assessed With Chest Xray in Chronic Kidney Disease PatientsDokument6 SeitenThe Correlation Between Disease Stage and Pulmonary Edema Assessed With Chest Xray in Chronic Kidney Disease PatientsAnnisa RabbaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypertensive Crises: Diagnosis and Management in The Emergency RoomDokument10 SeitenHypertensive Crises: Diagnosis and Management in The Emergency RoomGede AdiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypertensive Emergency PDFDokument14 SeitenHypertensive Emergency PDFOsiithaa CañaszNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisis HipertensivaDokument11 SeitenCrisis HipertensivaJakeline MenesesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiovascular Disease: Epidemiology, 2018Dokument11 SeitenCardiovascular Disease: Epidemiology, 2018Princess Diannejane MurlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cardiovascular SystemDokument29 SeitenThe Cardiovascular SystemTumbali Kein Chester BayleNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Heart Activity 3 PDFDokument4 SeitenThe Heart Activity 3 PDFbiancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACLS Exam - A&B VersionsDokument36 SeitenACLS Exam - A&B VersionsMohamed El-sayed100% (1)

- Rainer Kozlik-Feldmann, Georg Hansmann, Damien Bonnet, Dietmar Schranz, Christian Apitz, Ina Michel-BehnkeDokument7 SeitenRainer Kozlik-Feldmann, Georg Hansmann, Damien Bonnet, Dietmar Schranz, Christian Apitz, Ina Michel-BehnkeHerdinadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shock Management, by Ayman RawehDokument15 SeitenShock Management, by Ayman RawehaymxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Terminology Cardiovascular SystemDokument35 SeitenMedical Terminology Cardiovascular Systemapi-26819951486% (7)

- Finite Element and Mechanobiological Modelling of Vascular DevicesDokument166 SeitenFinite Element and Mechanobiological Modelling of Vascular DevicesASHISH AGARWALNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Case Study On Ischemic Stroke: J.H. Cerilles State CollegeDokument21 SeitenA Case Study On Ischemic Stroke: J.H. Cerilles State CollegeNicole Aranding100% (4)

- MidcabDokument7 SeitenMidcabNs PadiludinNoch keine Bewertungen

- KARDIOLOGIDokument120 SeitenKARDIOLOGIEsti IvanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Correlation Between Hba1c Level and Epicardial Fat Thickness in Acute Coronary Syndrome PatientDokument5 SeitenCorrelation Between Hba1c Level and Epicardial Fat Thickness in Acute Coronary Syndrome PatientIJAR JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- 103 Radionuclide Imaging TechniquesDokument30 Seiten103 Radionuclide Imaging TechniquesrevanthNoch keine Bewertungen

- " Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics" "Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics"Dokument7 Seiten" Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics" "Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics"kookiescreamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) : Kussia Ayano (MD)Dokument54 SeitenCongenital Heart Disease (CHD) : Kussia Ayano (MD)Yemata HailuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Structure and Function of The Cardiovascular SystemDokument28 SeitenThe Structure and Function of The Cardiovascular SystemShamaeNogaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heart Palpitations Top 6 Herbs According To A HerbalistDokument31 SeitenHeart Palpitations Top 6 Herbs According To A HerbalistCarl MacCordNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code BlueDokument18 SeitenCode Blueandri100% (1)

- Cardiotonics & Inotropic Drugs PDFDokument10 SeitenCardiotonics & Inotropic Drugs PDFZehra AmirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cp201012 Learning Light-395Dokument2 SeitenCp201012 Learning Light-395jyothiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Blood CountDokument3 SeitenComplete Blood CountivantototaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- (KEL 1) Jurnal IMA (Pak Arif)Dokument8 Seiten(KEL 1) Jurnal IMA (Pak Arif)Nurul HendrianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expt.4 To Generate ECG Signal Using LabVIEWDokument3 SeitenExpt.4 To Generate ECG Signal Using LabVIEWNeha GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- C1-Human HeartDokument3 SeitenC1-Human HeartNursuzela Abd MalekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Common Emergency DrugsDokument58 SeitenCommon Emergency Drugshatem alsrour84% (19)

- Lecturio ComDokument7 SeitenLecturio ComAlex Ivan Chen TejadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECG-Dr - Najeeb-By Kurdish Medico PDFDokument265 SeitenECG-Dr - Najeeb-By Kurdish Medico PDFMarwa Ahmad Abdelmohsen75% (4)

- 9 9 2023Dokument10 Seiten9 9 2023hoangnam147680Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1circulatory SystemDokument26 Seiten1circulatory SystemElisa EstebanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecologic Model CVA TCHDokument2 SeitenEcologic Model CVA TCHAlyzia DBNoch keine Bewertungen