Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Poverty and Economic Policy in The Philippines

Hochgeladen von

Erika Marie Cardeño ColumnasOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Poverty and Economic Policy in The Philippines

Hochgeladen von

Erika Marie Cardeño ColumnasCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Development

Past economic policies

FOCUS that hampered growth,

and the resistance of

powerful elites to

Poverty and much-needed reforms,

were largely responsi-

Economic Policy ble for the high

incidence and persis-

in the Philippines tence of poverty in the

Philippines. Recent

policy changes have

spurred growth, but

additional reforms

could accelerate the

reduction of poverty.

Philip Gerson

P

OVERTY is both more widespread and more persis- as measured by the Gini coefficient (a ratio of income

tent in the Philippines than in neighboring ASEAN inequality, with 0 representing absolute equality and 1 repre-

(Association of South East Asian Nations) coun- senting absolute inequality), is extremely unequal. Moreover,

tries. While the poverty rate has decreased in the the Gini coefficient barely changed during 1957–94, varying

Philippines over the past 25 years, the decline has been only between 0.45 and 0.51 (Table 2). In 1994, the richest 20

slower than in other ASEAN countries. Some of the blame percent of the population received 52 percent of the coun-

for the Philippines’ slow progress in reducing the incidence try’s total income, nearly 11 times the share of the poorest 20

of poverty can be attributed to past economic policies that percent. These figures had changed little since the 1980s and

retarded growth by discriminating against agriculture and had even become slightly worse: in 1985, the richest 20 per-

discouraging investment in human capital. These policies, in cent of the population received the same share of national

turn, sustained powerful interest groups that blocked or income as in 1994 and their average income was about 10

delayed economic reform. times that of the poorest 20 percent. The distribution of

The Philippines began to undertake political and eco- assets has also shown little improvement over the last few

nomic reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, decades. Between 1960 and 1990, for example, the Gini coef-

and GDP growth has accelerated to about 5 percent a year ficient on landholding worsened slightly.

since 1994. With faster growth, the percentage of Filipinos Although an improvement in income distribution is often

living below the poverty line is decreasing, but agricultural accompanied by a decrease in the poverty rate (absent a sharp

reform and increased investment in human capital would decline in national income), the two are not necessarily

allow a more drastic reduction in the poverty rate.

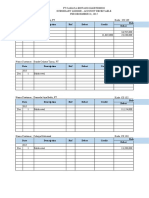

Table 1

Income distribution and poverty

Poverty incidence in selected Asian countries 1

The incidence of poverty in the Philippines was not unusu- (percent)

ally high in the early 1970s, compared with a representative Annual First Last

sample of Asian countries (Table 1), but very slow subse- Years reduction year year

quent progress in reducing the rate of poverty meant that Philippines 1971–94 0.7 52 36

by the early 1990s, the poverty rate was dramatically higher Indonesia 1970–90 2.0 58 19

in the Philippines than in its neighbors. (It is worth noting Korea 1970–90 0.9 23 5

Malaysia 1973–87 1.6 37 14

that comparisons of poverty rates across countries are com-

Thailand 1962–88 1.4 59 22

plicated because poverty thresholds are calculated differently

in every country. Poverty rates in these countries have also Sources: World Bank, 1996, and Philippines, National Statistical Coordination Board,

1996.

been affected by the recent economic downturn in the 1 Defined as proportion of families living below the poverty line.

region.) In addition, income distribution in the Philippines,

46 Finance & Development / September 1998

Table 2

Income distribution in selected years, 1957–94

1957 1961 1965 1971 1985 1988 1991 1994

Gini coefficient 0.461 0.497 0.513 0.494 0.447 0.445 0.468 0.451

Percent of income, top 20 percent 48.6 56.5 56.0 54.0 52.1 51.8 53.9 51.9

Percent of income, bottom 20 percent 6.5 4.2 3.5 3.6 5.2 5.2 4.7 4.9

Ratio of incomes of top 20 percent to 7.5 13.5 16.0 15.0 10.0 10.0 11.5 10.6

bottom 20 percent

Sources: 1957–71, Deininger and Squire, 1996; and 1985–94, Philippines, National Statistics Office, various years.

Economic policy and poverty

Table 3

Gini coefficients in selected Asian countries The sluggish pace at which the Philippines has reduced

poverty over time can be traced to economic policies that

Years First year Last year hobbled growth, many of which have recently been aban-

Philippines 1957–94 0.461 0.451 doned, as well as to policies that have more directly perpetu-

Indonesia 1964–93 0.333 0.317 ated income inequality.

Korea 1953–88 0.340 0.336 Exchange and trade policies. For many years, the

Malaysia 1970–89 0.500 0.484 Philippines pursued an industrial policy that encouraged

Thailand 1962–92 0.413 0.515

import substitution rather than promoting exports. Until

Sources: Deininger and Squire, 1996, and Philippines, National Statistics Office, 1994. tariff reforms were introduced in 1991, trade policies heavily

penalized the primary and agricultural sectors and benefited

the manufacturing sector. In addition, the overvaluation of

linked. It is quite possible for poverty rates to fall even when the Philippine peso during several periods between the 1950s

the distribution of income becomes more unequal. In fact, and the 1980s contributed to declines in the prices of exports

while progress in fighting poverty in the Philippines has been in peso terms and diverted resources away from agriculture

slow by Asian standards, the country’s disappointing experi- and toward import-substituting manufacturing. In addition,

ence in improving income distribution is not unique in Asia. incomes in the agricultural sector were depressed by heavy

None of the countries cited in Table 1 as being more success- regulation. Beginning in the 1970s, price controls were

ful in reducing poverty rates over time has experienced a large imposed on rice and other products, and the importation of

decline in its Gini coefficient in recent decades (Table 3). wheat and soybeans was monopolized. The government

Instead, these countries seem to have lowered their poverty introduced controls on the production, marketing, and pro-

rates by increasing incomes for all income groups. This sug- cessing of coconuts and created a price stabilization fund,

gests that decades of very slow growth, rather than inequality, while fertilizer and pesticide imports were controlled

may have been the most important cause of the persistence of through licensing requirements.

poverty in the Philippines. Indeed, between 1970 and 1995, Overvaluation of the peso, tariff policies, and heavy gov-

real GDP in the Philippines grew at an annual rate about half ernment regulation discouraged investment in agriculture,

that of the other Asian countries and barely exceeded popula- with a disastrous effect on productivity. For example, during

tion growth (see chart). 1982–85, productivity in the coconut sector—which had

Poverty in the Philippines, as in most countries, tends to long been the country’s most important agricultural industry

be associated with low education levels for heads of house- in terms of export earnings and employment—averaged

holds and with large family size. Poor Filipinos are dispro- 1.0 metric ton per hectare, exactly the same as during

portionately employed in agriculture, fishing, and forestry: 1962–66. Low agricultural productivity remains a drag on

these occupations account for 62 percent of poor house- growth, partly because some agricultural tariffs have been

holds, but for only about 40 percent of the employed labor maintained at the maximum level permitted by World Trade

force. The poor also seem to be disproportionately rural: Organization (WTO) agreements, even though tariffs were

60 percent of the poor were living in rural areas in 1991, dramatically lowered in almost all other sectors during the

compared with 51 percent of the total Philippine population. early and mid-1990s. While real GDP growth has averaged

Since 1960, the proportion of the population classified as 5 percent annually since 1994, growth in the agriculture, fish-

urban has increased from about 30 percent to 50 percent, ing, and forestry sectors has averaged less than half this rate.

while the proportion of the poor living in urban areas has The overvaluation of the peso, as well as fiscal and other

grown from 30 percent to 40 percent. Although these figures incentives (such as tax exemptions for imported capital

could be interpreted as suggesting that migration from rural equipment), has also reduced the cost of capital and encour-

to urban areas has led to a reduction in poverty rates, they aged the substitution of capital for labor. As a result, the

reflect, in part, a statistical artifact: rapidly growing rural share of the industrial sector in total employment has grown

areas tend to be reclassified as urban, while slowly growing only from 13 percent in 1960 to 16 percent in 1996. Between

ones do not. In fact, between 1970 and 1990, poverty rates 1980 and 1996, 5 million new workers joined the Philippine

declined faster in areas that were initially classified as rural workforce. The agricultural and services sectors accounted

than in areas that were classified as urban. for nearly 80 percent of the increase in employment, while

Finance & Development / September 1998 47

Development

FOCUS

fewer than 10 percent of the new workers joined the manu- poverty incidence (about 8 percent) in the country, is partic-

facturing sector. ularly favored. In addition, expenditure has concentrated on

Federal government expenditures. Because the poor are expensive, tertiary-level care, which lower-income families

better endowed with labor than with physical capital, pub- cannot afford; between 1981 and 1990, the share of total

lic expenditures on education and health can exert an health care expenditures captured by preventive care fell

important influence on poverty and income distribution. from 35 percent to 14 percent, while the share of curative

Unfortunately, public investment in human capital in the care rose from 55 percent to 65 percent. This distribution of

Philippines was both low and inefficiently allocated for expenditure is not out of line with international averages: the

many years and thus had a limited effect on poverty and World Bank’s World Development Report 1993 calculated that

inequality. Historically, public education in the Philippines the average developing country government spent two-thirds

has been underfunded relative to other ASEAN countries; of its health care budget on secondary and tertiary care in

central government expenditures on education, both as a 1990. However, the report also noted that an optimal alloca-

percentage of GDP and as a percentage of total government tion of health care spending would be less than one-third

spending, were significantly lower than in Malaysia and going to secondary and tertiary care, with the bulk going to

Thailand, for example. Moreover, the distribution of educa- primary care, whose impact (in terms of reducing mortality

tion spending among levels of schooling is skewed toward rates) is much greater.

secondary and tertiary education. The government now Tax policy. Indirect taxes (for example, value-added taxes,

subsidizes a greater share of education expenses at the uni- excise taxes, and customs duties) account for about 70 per-

versity level (78 percent) than at the primary level (69 per- cent of tax revenues in the Philippines; it would therefore be

cent). While participation rates in primary schools are easy to conclude that the overall tax system must be regres-

high, they drop sharply by age 13 for lower-income pupils sive. Because the poor consume a larger percentage of their

in urban areas, and by age 11 for those in rural areas. Scores incomes than do the wealthy, consumption-based taxes are

on achievement tests and data on the number of textbooks nearly always somewhat regressive in their impact, even

per student raise concerns about the quality of education when food is exempt. However, the fairness of any particular

received by low-income students, particularly in rural tax—and, indeed, of the tax system as a whole—must be

areas. If spending were reallocated toward primary educa- viewed in the context both of the alternatives for raising rev-

tion, the quality would improve significantly and a greater enues and of the progressivity of the expenditure side of the

proportion of lower-income students might remain in budget—that is, who benefits from tax revenues. In other

school, especially in rural areas. words, indirect taxes may be less regressive than the other

Spending on health and nutrition in the Philippines is also revenue-raising alternatives available to the government,

relatively low by ASEAN standards, and the composition of and, if revenues are raised in a mildly regressive manner and

expenditure is biased toward higher-income consumers. Per spent in a highly progressive way, the impact of fiscal policy

capita spending on health care tends to be higher, and access could still prove to be progressive.

to primary health care stations better, in urban areas than in Although the Philippines’ individual income tax system is

rural ones—Metropolitan Manila, which has the lowest quite progressive, at least on paper, it is easier for the wealthy

than for the less well-off to reduce or avoid taxes (as is the

case in many countries). Although the Philippines has with-

Annual population and real GDP growth rates in holding taxes on the incomes of wage earners, the earnings of

selected Asian countries, 1970–95 businessmen are harder to measure, and the wealthy have

(percent)

more opportunity to engage in perfectly legal tax-reduction

10

strategies, such as tax-free investments and deposits. In coun-

tries where the administration of taxes on the wealthy is diffi-

8 cult, and where there are many tax incentives and preferences

that benefit the wealthy, effective tax rates for this group may

6 be much lower than statutory ones, and an income tax that is

progressive on paper may be neutral or even regressive in

4 practice. When income taxes can easily be avoided, shifting

the tax burden to consumption may actually be more pro-

2

gressive, with the wealthy paying a higher proportion of tax

revenues and a higher percentage of their incomes in tax.

Recently, the Philippine government introduced a number of

0

Indonesia Korea Malaysia Philippines Thailand tax reforms designed to enhance the overall progressivity of

Real GDP

the tax system—for example, by bringing into the income tax

Population

net individuals (mostly high-income ones) who were previ-

Source: International Monetary Fund, 1997, International Financial Statistics Yearbook

(Washington). ously out of the tax system’s reach.

48 Finance & Development / September 1998

More generally, it is very difficult in any Although the coconut monopoly was dis-

country to effect a major redistribution of mantled by the administration of Corazon

income through the tax system, in large part Aquino, progress in reforming the agriculture

because many of the very poorest citizens are sector has been slow. For example, land

outside the tax net. For this reason, targeted reform efforts have met with little success, in

expenditure programs that use revenues raised large part because of the power of landed

in an economically efficient manner may be elites. While efforts to break up large land

more effective in helping the poor. While Philip Gerson is an holdings began in the 1950s and have recurred

recent tax reforms and improvements in tax Economist in the IMF’s sporadically since then—including the

administration that reduce the scope for Fiscal Affairs Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program

income tax evasion will make the Philippine Department. (CARP) initiated in 1987—landholding actu-

tax system more progressive, ultimately it is ally became more concentrated between 1960

very much a question not just of where the and 1990. Given the large budgetary expense

money comes from but also where it goes that determines the that would be required to achieve a significant redistribution

impact of fiscal policy on income distribution and poverty. of land, abandoning CARP in favor of additional spending on

rural education and health might ultimately do more to

Income distribution and government policies reduce poverty rates.

While economic policies have clearly affected poverty rates

and income distribution in the Philippines, unequal income Conclusion

distribution has made it difficult to enact reforms that would To a great extent, the relative lack of progress in improving

increase equity. Given the costs of organizing political activ- poverty indicators in the Philippines can be attributed to the

ity, the wealthy have a political influence in most countries country’s poor growth performance. Economic growth in

that is greater than their numbers might justify. The more the Philippines has been dampened by economic policies

unequal the distribution of income, the smaller will be the that favored capital over labor and import-substituting

number of individuals exerting political influence and the industries over agriculture, and that led to underinvestment

greater the resistance to policy reforms designed to redress in the human capital of the poor. These policies had a devas-

income inequalities. At the same time, the industrial strategy tating effect, particularly on the agricultural sector, whose

pursued by the Philippines, which was based on heavy regula- low productivity remains a drag on growth. The persistence

tion and import substitution, created many opportunities for of policies that have failed to stimulate growth owes much to

rent-seeking behavior and thus contributed to the concentra- the important role played by elites in Philippine politics and

tion of power in an elite. The manipulation of economic poli- society. The Philippine government has introduced a num-

cies for the benefit of a small group of well-connected ber of reforms that have stimulated growth, and these

individuals probably reached its most notorious stage during should, in turn, help to alleviate poverty. It could achieve

the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos (1965–86), when tax even more by eliminating remaining biases against agricul-

breaks, low-cost loans, debt bailouts, and monopoly rights ture and investing more in health and education, especially

were frequently granted to supporters of the president at the in rural areas. F&D

expense of taxpayers, workers, or small farmers.

The coconut industry provides an interesting case study

This article is based on Philip Gerson, 1998, “Poverty, Income

of the interaction between economic policies and income

Distribution, and Economic Policy in the Philippines,” IMF Working

distribution. Beginning in the early 1970s, a series of presi-

Paper 98/20 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

dential decrees created a single institution with control of all

stages of coconut production, from the purchase of References:

coconuts from farmers to the sale of processed oil on the Klaus Deininger and Lyn Squire, 1996, “A New Data Set Measuring

domestic and international markets. Although the measures Income Inequality,” World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 10, pp. 565–91.

were purportedly motivated by a desire to improve condi- International Monetary Fund, 1997, International Financial Statistics

tions for coconut growers, the main beneficiaries seem to Yearbook (Washington).

have been a small number of politically well-connected

Philippines, National Statistical Coordination Board, 1996, “Philippine

individuals. Aided by a substantial levy on coconut produc-

Poverty Statistics” (Manila).

ers and by its monopsony power (which enabled it to

increase profit margins on its production by 600 percent), Philippines, National Statistics Office, Family Income and

the United Coconut Mills/United Coconut Planters’ Bank Expenditure Survey (Manila, various years).

complex amassed vast sums of money at the expense of World Bank, 1996, “A Strategy to Fight Poverty: Philippines”

millers and traders, who were driven out of business, and of (Washington).

growers, who were forced to sell their output to one World Bank, World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health

extremely powerful buyer. (New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank).

Finance & Development / September 1998 49

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Poverty and Economic Policy in The PhilippinesDokument8 SeitenPoverty and Economic Policy in The PhilippinesJofil LomboyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes of PovertyDokument23 SeitenCauses of PovertyMarkiko Rivera100% (6)

- PB 2011-01 - Improving Inclusiveness of Growth Through CCTsDokument17 SeitenPB 2011-01 - Improving Inclusiveness of Growth Through CCTsNerissa PascuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Changes in The Understanding of Global PovertyDokument14 SeitenChanges in The Understanding of Global PovertyHWSC BSDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper About Poverty - NSTP Project For FINALSDokument5 SeitenResearch Paper About Poverty - NSTP Project For FINALSLeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty in The Philippines - Causes, Constraints and Opportunities - Asian Development BankDokument4 SeitenPoverty in The Philippines - Causes, Constraints and Opportunities - Asian Development BankKim TaehyungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resilient Housing: Technological Institute of The PhilippinesDokument13 SeitenResilient Housing: Technological Institute of The PhilippinesJennifer VillarNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADB Poverty PhilippinesDokument4 SeitenADB Poverty PhilippinesCarla CucuecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reforming Philippine Anti-Poverty PolicyDokument92 SeitenReforming Philippine Anti-Poverty Policynora o. gamoloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On Poverty in The Philippines: Asian Development BankDokument6 SeitenNotes On Poverty in The Philippines: Asian Development BankStephanie HamiltonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Summary - Poverty Philippines (ADB)Dokument6 SeitenExecutive Summary - Poverty Philippines (ADB)mlexarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Population Management Should Be Mainstreamed in The Philippine Development AgendaDokument4 SeitenPopulation Management Should Be Mainstreamed in The Philippine Development AgendaMulat Pinoy-Kabataan News NetworkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Are We Winning The Fight Against Poverty? An Assessment of The Poverty Situation in The PhilippinesDokument47 SeitenAre We Winning The Fight Against Poverty? An Assessment of The Poverty Situation in The PhilippinesFerdinand MarcosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problems of PoliciesDokument2 SeitenProblems of PoliciesAirah Jane TiglaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pro-Poor Growth and PoliciesDokument59 SeitenPro-Poor Growth and PoliciesDanish SajjadNoch keine Bewertungen

- En 14011Dokument27 SeitenEn 14011prabumech05Noch keine Bewertungen

- Montes 1987 The Impact of Macroeconomic Adjustments On Living Standard in The PhilippinesDokument11 SeitenMontes 1987 The Impact of Macroeconomic Adjustments On Living Standard in The PhilippinesCharlene EbordaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Think Piece SUPAPODokument5 SeitenThink Piece SUPAPOKenneth Dela cruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report On Poverty AlleviationDokument8 SeitenReport On Poverty AlleviationAshwini Kumar PalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty in The New MilleniumDokument7 SeitenPoverty in The New Milleniumapi-36961780% (1)

- Paper On Poverty and InequalityDokument3 SeitenPaper On Poverty and InequalitymonaileNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper About The Impact of The Increase or Decrease of The Filipino Citizens Living Below The Poverty LineDokument21 SeitenResearch Paper About The Impact of The Increase or Decrease of The Filipino Citizens Living Below The Poverty LineJohnReymondApeliasNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEARCA Rural Transformation in The Philippines A Development AgendaDokument8 SeitenSEARCA Rural Transformation in The Philippines A Development AgendaDesie NayreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 18 Activity (Gulle, Andre T.) LWR - K2Dokument1 SeiteLesson 18 Activity (Gulle, Andre T.) LWR - K2andreNoch keine Bewertungen

- BarcenaDokument2 SeitenBarcenabobbytheoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty Alleviation Programmes in India: A Social Audit: Review ArticleDokument10 SeitenPoverty Alleviation Programmes in India: A Social Audit: Review ArticleAadhityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SIBALDokument17 SeitenSIBALapi-26570979Noch keine Bewertungen

- This Content Downloaded From 49.207.140.11 On Sun, 30 May 2021 20:57:20 UTCDokument17 SeitenThis Content Downloaded From 49.207.140.11 On Sun, 30 May 2021 20:57:20 UTCAadhityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Growth and Poverty Reduction - Draft - ADBDokument23 SeitenGrowth and Poverty Reduction - Draft - ADBoryuichiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phillipines Country ReportDokument20 SeitenPhillipines Country Reporthino hinxNoch keine Bewertungen

- ch2 PDFDokument11 Seitench2 PDFMichel Monkam MboueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty in the Philippines: Causes, Constraints, and OpportunitiesVon EverandPoverty in the Philippines: Causes, Constraints, and OpportunitiesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (4)

- Population, Poverty and DevelopmentDokument21 SeitenPopulation, Poverty and DevelopmentJake CervantesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Economic Development A Turning Point?: Kelly Bird and Hal HillDokument20 SeitenPhilippine Economic Development A Turning Point?: Kelly Bird and Hal HillOLIVEROS, Reiner Joseph B.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Povmonitoring CasestudyDokument25 SeitenPhilippines Povmonitoring CasestudyChadrhet MensiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan Economy PovertyDokument47 SeitenPakistan Economy PovertyHamayal AzharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Key FindingsDokument2 SeitenSummary of Key FindingsJerard VismanosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes of Poverty in The PhilippinesDokument5 SeitenCauses of Poverty in The Philippinesangelouve100% (1)

- Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022 Overall FrameworkDokument12 SeitenPhilippine Development Plan 2017-2022 Overall FrameworkAngelica PagaduanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes of Poverty in The PhilippinesDokument3 SeitenCauses of Poverty in The PhilippinesSannyboy Paculio DatumanongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agrarian Reform and Poverty Reduction in The Philippines: Arsenio M. Balisacan andDokument20 SeitenAgrarian Reform and Poverty Reduction in The Philippines: Arsenio M. Balisacan andChante CabantogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Major OutputDokument12 SeitenFinal Major OutputMJ LositoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection Paper - Policy - Chapter 2Dokument1 SeiteReflection Paper - Policy - Chapter 2nathanieldagsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PovertyDokument2 SeitenPovertypratik3691Noch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty and Agriculture in The Philippines: Trends in Income Poverty and DistributionDokument46 SeitenPoverty and Agriculture in The Philippines: Trends in Income Poverty and DistributionCharmielyn SyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Past, Present, and Future of Agriculture Policy in AfricaDokument17 SeitenThe Past, Present, and Future of Agriculture Policy in AfricaIrene SimonNoch keine Bewertungen

- September1997 PDFDokument10 SeitenSeptember1997 PDFThe Concerned LawstudentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Socio-Economic Update: 11.1 PovertyDokument11 SeitenSocio-Economic Update: 11.1 PovertyMuhammad FaiqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Income Distribution in Malaysia: Old Issues, New Approaches (2008)Dokument24 SeitenIncome Distribution in Malaysia: Old Issues, New Approaches (2008)Adrian Loh100% (1)

- 02Dokument94 Seiten02IfyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty Alleviation Programmes in IndiaDokument10 SeitenPoverty Alleviation Programmes in IndiakaushikjethwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NEDA - Phil Dev't Plan 2017-2022, Chapter 4Dokument12 SeitenNEDA - Phil Dev't Plan 2017-2022, Chapter 4anon_249258367Noch keine Bewertungen

- Balisacan-Pernia TheRoralRoadtoPovertyReduction JAAS2002Dokument22 SeitenBalisacan-Pernia TheRoralRoadtoPovertyReduction JAAS2002Resty BalinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty in The Philippines and How It Affects The EconomyDokument23 SeitenPoverty in The Philippines and How It Affects The EconomyGian TuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty and InequalityDokument79 SeitenPoverty and InequalityIrisGayleJavierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Economic HistoryDokument6 SeitenPhilippine Economic HistoryKristel FieldsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eduardo Zepeda EIP UNDPMexicoFailedPro-MarketPolicyExperience In-FocusDokument3 SeitenEduardo Zepeda EIP UNDPMexicoFailedPro-MarketPolicyExperience In-Focuseduardo zepedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development Asia—Tackling Asia's Inequality: Creating Opportunities for the Poor: December 2008Von EverandDevelopment Asia—Tackling Asia's Inequality: Creating Opportunities for the Poor: December 2008Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 near East and North Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition: Building Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition in Times of Conflict and Crisis. A Perspective from the near East and North Africa RegionVon Everand2017 near East and North Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition: Building Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition in Times of Conflict and Crisis. A Perspective from the near East and North Africa RegionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pembayaran PoltekkesDokument12 SeitenPembayaran PoltekkesteffiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top Form 10 KM 2014 ResultsDokument60 SeitenTop Form 10 KM 2014 ResultsabstickleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Healthpro Vs MedbuyDokument3 SeitenHealthpro Vs MedbuyTim RosenbergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Working Capital Appraisal by Banks For SSI PDFDokument85 SeitenWorking Capital Appraisal by Banks For SSI PDFBrijesh MaraviyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fiscal Deficit UPSCDokument3 SeitenFiscal Deficit UPSCSubbareddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Packing List PDFDokument1 SeitePacking List PDFKatherine SalamancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HPAS Prelims 2019 Test Series Free Mock Test PDFDokument39 SeitenHPAS Prelims 2019 Test Series Free Mock Test PDFAditya ThakurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation NGODokument6 SeitenPresentation NGODulani PinkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Latihan Soal PT CahayaDokument20 SeitenLatihan Soal PT CahayaAisyah Sakinah PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhiratara Pradipta Narendra (1506790210)Dokument4 SeitenDhiratara Pradipta Narendra (1506790210)Pradipta NarendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Recycling PurposesDokument14 SeitenWater Recycling PurposesSiti Shahirah Binti SuhailiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ahmed BashaDokument1 SeiteAhmed BashaYASHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bye, Bye Nyakatsi Concept PaperDokument6 SeitenBye, Bye Nyakatsi Concept PaperRwandaEmbassyBerlinNoch keine Bewertungen

- EOQ HomeworkDokument4 SeitenEOQ HomeworkCésar Vázquez ArzateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Cycle Indicators HandbookDokument158 SeitenBusiness Cycle Indicators HandbookAnna Kasimatis100% (1)

- Proposal Tanaman MelonDokument3 SeitenProposal Tanaman Melondr walferNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clerks 2013Dokument12 SeitenClerks 2013Kumar KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDC Yanque FinalDokument106 SeitenPDC Yanque FinalNilo Cruz Cuentas100% (3)

- India of My Dreams: India of My Dream Is, Naturally, The Same Ancient Land, Full of Peace, Prosperity, Wealth andDokument2 SeitenIndia of My Dreams: India of My Dream Is, Naturally, The Same Ancient Land, Full of Peace, Prosperity, Wealth andDITSANoch keine Bewertungen

- Pandit Automotive Pvt. Ltd.Dokument6 SeitenPandit Automotive Pvt. Ltd.JudicialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microsoft Word - CHAPTER - 05 - DEPOSITS - IN - BANKSDokument8 SeitenMicrosoft Word - CHAPTER - 05 - DEPOSITS - IN - BANKSDuy Trần TấnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revenue Procedure 2014-11Dokument10 SeitenRevenue Procedure 2014-11Leonard E Sienko JrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bill To / Ship To:: Qty Gross Amount Discount Other Charges Taxable Amount CGST SGST/ Ugst Igst Cess Total AmountDokument1 SeiteBill To / Ship To:: Qty Gross Amount Discount Other Charges Taxable Amount CGST SGST/ Ugst Igst Cess Total AmountSudesh SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IBDokument26 SeitenIBKedar SonawaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flex Parts BookDokument16 SeitenFlex Parts BookrodolfoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metropolitan Transport Corporation Guindy Estate JJ Nagar WestDokument5 SeitenMetropolitan Transport Corporation Guindy Estate JJ Nagar WestbiindduuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dak Tronic SDokument25 SeitenDak Tronic SBreejum Portulum BrascusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Levacic, Rebmann - Macroeconomics. An I... o Keynesian-Neoclassical ControversiesDokument14 SeitenLevacic, Rebmann - Macroeconomics. An I... o Keynesian-Neoclassical ControversiesAlvaro MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MHO ProposalDokument4 SeitenMHO ProposalLGU PadadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ekspedisi Central - Google SearchDokument1 SeiteEkspedisi Central - Google SearchSketch DevNoch keine Bewertungen