Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire Validation Study

Hochgeladen von

nermal93Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire Validation Study

Hochgeladen von

nermal93Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics

The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire validation study

A. FRASER*, B. C. DELANEY*, A. C. FORD , M. QUME* & P. MOAYYEDI*

*Department of Primary Care and SUMMARY

General Practice, Primary Care Clin-

ical Sciences Building, University of Background

Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birming-

Assessment of symptoms should be the primary outcome measure in

ham; Centre for Digestive Diseases,

Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds, West dyspepsia clinical trials. This requires a reliable, valid and responsive

Yorkshire, UK questionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of dyspepsia.

The Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire fulfils these characteristics, but is

Correspondence to:

Dr B. C. Delaney, Department of

long and was not designed for self-completion, so a shorter question-

Primary Care and General Practice, naire was developed (the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire).

Primary Care Clinical Sciences

Building, University of Birmingham, Aim

Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK. To assess the acceptability, interpretability, internal consistency, reliab-

E-mail: a.a.fraser@bham.ac.uk

ility, validity and responsiveness of the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia

Questionnaire in primary and secondary care.

Publication data

Submitted 9 August 2006 Methods

First decision 24 August 2006 Unselected primary and secondary care patients completed the Short-

Resubmitted 9 December 2006

Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire. Test–retest reliability was assessed

Accepted 13 December 2006

after 2 days. Validity was measured by comparison with general practi-

tioners’ diagnosis. Sensitivity analysis and logistic regression were

employed to determine the most valid scoring system. Responsiveness

was determined before and after treatment for endoscopically proven

disease.

Results

The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire was administered to 388

primary care and 204 secondary care patients. The Pearson coefficient

for test–retest reliability was 0.93. The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia

Questionnaire had a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 75%. A

highly significant response to change was observed (P < 0.005).

Conclusions

The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire is a reliable, valid and

responsive self-completed outcome measure for quantifying the fre-

quency and severity of dyspepsia symptoms, which is shorter and more

convenient than the Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

ª 2007 The Authors 477

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03233.x

478 A . F R A S E R et al.

measures.5 Twelve assessed symptoms only, and 14

INTRODUCTION

were multidimensional. Of the unidimensional ques-

Dyspepsia is a common condition, and one that con- tionnaires, only two assessed both frequency and

sumes considerable resources in both investigation and severity of dyspepsia and had proven reliability, valid-

treatment and of which there is still a great deal of ity and responsiveness. The Reflux Disease Diagnostic

uncertainty regarding its management.1, 2 As a result, Questionnaire (RDQ) is an excellent measure for GERD,

a number of ‘cost-effectiveness’ randomized trials of but is not validated to assess dyspepsia.11 The Leeds

dyspepsia management strategies have been conduc- Dyspepsia Questionnaire (LDQ)10 was the only fully

ted. One difficulty for researchers has been choosing validated unidimensional instrument to assess both

an appropriate outcome measure as definitions of dys- frequency and severity of dyspepsia symptoms.

pepsia have changed over the years, and cost-effect- Although the LDQ is a useful unidimensional outcome

iveness studies require that the ‘effect measure’ is not measure for dyspepsia, it has three main disadvanta-

contaminated by ‘resource use questions’ such as visits ges. It is researcher administered (not self-completed),

to a doctor. Multidimensional scales that also assess it is long (nine pages) and has a long reference time

quality of life are particularly problematic, as there are frame (6 months). The aim of this study was to valid-

better validated quality of life measures that have gen- ate a shortened and revised the LDQ as a suitable

eralizability over other disease areas (e.g. Health Util- measure for dyspepsia trials.

ity Index3 and EQ-5D4). As there is no ‘absolute’

definition of dyspeptic symptoms we rely on question-

METHODS

naires that have established psychometrics.5 Dyspepsia

symptoms can be assessed by measuring either fre-

Questionnaire development

quency or severity. The frequency of symptoms has

been found to correlate more closely with a clinical The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire

diagnosis of dyspepsia than severity, indicating that (SF-LDQ) was developed by shortening and revising

frequency may be more valid for pragmatic studies.6 the previously validated LDQ.10 The LDQ contained

In gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD), severity eight questions relating to dyspeptic symptoms, and

of symptoms correlates more closely with oesophagitis one question about the most troublesome symptom for

cure than frequency, indicating that severity may be the patient. The SF-LDQ contained the four questions

more responsive to change.7 Measuring both frequency from the LDQ which had the greatest validity com-

and severity of dyspepsia symptoms may improve both pared with dyspepsia diagnosis by general practition-

validity and responsiveness to change of an instru- ers (GP) and gastroenterologists.12 Each question

ment compared with measuring either alone.6–9 A final comprised two stems concerning the frequency and

important factor for cost-effectiveness trials is that the severity of each symptom during the last 2 months.

instrument is suitable for self-completion by the sub- This time frame was a balance between reducing recall

ject, in terms of length and ease of comprehension. bias (requiring a shorter time frame) and maximizing

For clinical trials based in a primary care setting, data capture without unnecessary respondent burden

the outcome measure should have been validated in a (requiring a longer time frame).9 The SF-LDQ also con-

primary care population, where the aetiology, preval- tained a single question concerning the most trouble-

ence and severity of patients’ symptoms may differ to some symptom experienced by the patient to enable

those from secondary or tertiary care populations.10 categorization of patients on the basis of predominant

In addition, outcome measures should be able to heartburn or epigastric pain.

distinguish between patients suffering from predomin- The SF-LDQ was redesigned to increase its accepta-

antly ulcer-like symptoms (epigastric pain) or reflux bility, interpretability and feasibility of self-comple-

symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation); some evi- tion. The questions were arranged to fit onto a single

dence suggests that predominant ulcer-like or reflux A4 page, with shaded boxes around the questions and

symptoms do not reliably predict endoscopic diagnosis tick boxes for responses. Short summaries of the

of oesophagitis or ulcer, respectively.11 symptoms were included to reduce ambiguity, and dia-

In a recent review of symptom-based outcome grammatic representations of epigastric pain and

measures for dyspepsia and GERD trials 37 studies heartburn were added to ensure understanding of these

were identified describing 26 questionnaire outcome symptoms.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

D Y S P E P S I A Q U E S T I O N N A I R E V A L I D A T I O N S T U D Y 479

The SF-LDQ was piloted initially using six rounds of 386 and 841 of 32 48213) with any condition. As

peer review and feedback. Version 6 of the question- dyspeptic symptoms affect around 28% of the popu-

naire was piloted using a sample of 67 consecutive lation,14, 15 we did not specifically select patients

primary care patients. Several modifications of the for- with dyspepsia. The secondary care study population

mat were made and instructions were included on the consisted of unselected patients aged 18 and over,

questionnaire as a result. The final version of the attending for endoscopy at the Leeds General Infirm-

SF-LDQ is attached (Figure 1). ary. Patients were excluded if they were incapable of

giving informed consent, or if they could not speak

or read English.

Evaluation of the SF-LDQ

Patients were asked to participate in the study on

The characteristics of the questionnaire were exam- arrival at their GP’s surgery or the endoscopy suite.

ined using patient populations in both primary care, A trained researcher obtained informed consent.

with a relatively low prevalence of disease, and sec- Patients self-completed the SF-LDQ and an assessment

ondary care, with a high prevalence of dyspepsia. sheet containing questions about the acceptability and

The primary care population consisted of consecutive interpretability of the questionnaire. These were sealed

patients aged 18–65, presenting to two inner city in an envelope before seeing the GP or gastroenterolo-

general practices in Birmingham (deprivation ranks of gist, who made a blind assessment of the whether the

Figure 1. The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire (SF-LDQ).

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

480 A . F R A S E R et al.

patient suffered with dyspepsia and recorded this on 231 (39%) were male. Ages for the primary care patients

the preprinted envelope along with demographic infor- ranged from 18 to 65, and for secondary care, 18–81.

mation. Validity was established by comparing the Fifty-five questionnaires (9%) had one or more missing

SF-LDQ score with the presence or absence of dyspep- responses and were excluded from the final analysis, as

sia as diagnosed by the GP or gastroenterologist. a summed score could not be calculated. Score analysis

All primary care participants were asked to complete was therefore performed on 375 patients from primary

a second SF-LDQ after 2 days to assess test–retest reli- care and 162 patients from secondary care.

ability. Within the secondary care population, patients

identified as having oesophagitis or peptic ulcer dis-

Interpretability and acceptability

ease during endoscopy were asked to complete a sec-

ond SF-LDQ 2 months later after receiving treatment Five hundred and eighty-six participants from primary

of proven efficacy (proton pump inhibitor therapy and secondary care completed at least one question

and/or Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy). This concerning the interpretability and acceptability of the

enabled assessment of the SF-LDQ’s responsiveness to SF-LDQ. Overall, 97% found the questionnaire easy to

change in conditions with evidence-based treatments. read, 95% found it easy to interpret and 94% thought

Freepost envelopes were used to enhance response the layout was sufficiently clear.

rates, but non-responders to the second questionnaire Endorsement frequencies (the proportion of respond-

were not contacted. ents who chose each response category to a question)

Data were entered onto Microsoft Excel 2000 before were calculated for each response category to every

conversion into SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, v10 for question using combined data from primary and sec-

analysis. Logistic regression analysis was performed ondary care. Every response category had an endorse-

using Generalized Linear Interactive Modelling, Royal ment frequency of >5%, except for regurgitation

Statistical Society (GLIM) to determine the most valid severity ‘more than daily’ (Table 1). The distribution of

scoring system for the questionnaire. Statistical signi- responses to each of the questions about symptom fre-

ficance was determined where P < 0.05. Ethical quency and severity were positively skewed, reflecting

approval was obtained for South Birmingham, West the inclusion of the 278 participants from primary care

Birmingham and Leeds, UK. (47% of all participants) who did not have dyspepsia

according to their GPs diagnosis.

Non-response to questions regarding symptom fre-

RESULTS

quency occurred with 1% or less of participants, indica-

ting that this part of the questionnaire was acceptable

Population

and interpretable. However, there was no response to

A total of 592 patients were enrolled into the study, 388 questions regarding symptom severity in around 5% of

patients from primary care and 204 patients from sec- cases, indicating that this part of the questionnaire may

ondary care. Out of these, 361 (61%) were female and have been less acceptable or interpretable.

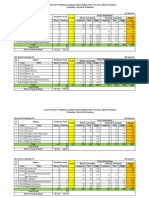

Table 1. Endorsement frequencies for each response category of the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire

Response category (%)

Not Less than Between monthly Between weekly More No

Symptom at all monthly and weekly and daily than daily response

Indigestion frequency 35 16 15 16 17 1

Heartburn frequency 39 18 15 15 13 0.8

Regurgitation frequency 43 21 14 14 8 0.5

Nausea frequency 38 23 16 14 9 1

Indigestion severity 45 12 13 16 8 5

Heartburn severity 50 11 15 12 7 5

Regurgitation severity 56 13 12 10 4 5

Nausea severity 46 18 12 11 6 6

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

D Y S P E P S I A Q U E S T I O N N A I R E V A L I D A T I O N S T U D Y 481

Internal consistency Sensitivity analyses

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for combined primary SF-LDQ scores were calculated using five different

and secondary care patients was 0.90, representing a methods to evaluate which produced the most valid

high level of internal consistency. The item-total cor- assessment of dyspepsia. These methods were:

relation for each question ranged from 0.57 to 0.75, 1 a summed total score of the frequency and sever-

suggesting that each question was independently asso- ity responses for each symptom (range: 0–32);

ciated with the total questionnaire score and that all 2 a summed score of the frequency responses for

questions were measuring different aspects of the same each symptom (range: 0–16);

condition. 3 a summed score of the severity responses for each

symptom (range: 0–16);

4 a categorized score of the single most frequent

Test–retest reliability

symptom (range: 0–4) and

In the primary care sample, 151 of 375 patients (40%) 5 a categorized score of the single most severe

returned a fully completed second questionnaire after symptom (range: 0–4).

at least 2 days. Pearson’s correlation coefficient Categorized scores were calculated by rating the sin-

between the first and second summed total scores was gle most frequent or severe symptom from 0 (not at

0.93, representing a high degree of reliability on all) to 4 (once a day or more). Scoring systems 1–3 are

re-testing the questionnaire. more practical and feasible to administer as they

require simple addition. Scoring systems 4 and 5 are

more complex, but may be more valid as they are

Validity

based on the Rome criteria for assessing the presence

Concurrent validity was established using the primary of dyspepsia.16

care population and divergent validity was examined by For each scoring system, a Receiver Operating Char-

comparing the primary and secondary care populations. acteristics (ROC) curve was plotted against the GPs’

diagnosis to determine the most sensitive and specific

point on the scale. The first point on each ROC curve

Concurrent validity

where sensitivity was greater than specificity was

Concurrent validity was assessed by comparing the selected as the ‘cut-off’ for diagnosing the presence of

SF-LDQ score with the GPs’ opinion of whether the dyspepsia. This gave a dichotomous outcome of whe-

patient had dyspepsia, expressed as a dichotomous ther dyspepsia was present or absent for each scoring

‘yes’ or ‘no’ response. Altogether 101 patients (27%) system. Table 2 shows the area under the ROC curves

were diagnosed as suffering with dyspepsia, 278 and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using differ-

patients (73%) had no dyspepsia. Nine participants out ent scoring systems, together with the chosen cut-off

of 375 with fully completed questionnaires did not score, sensitivity and specificity for that system.

receive a clinical assessment of dyspepsia by their GP, Although the summed frequency score produced a

so 366 primary care patients were analysed to deter- slightly larger area under the ROC curve (0.83) com-

mine concurrent validity. pared with the summed total score (0.82), this differ-

Table 2. Attributes of the five systems used to score the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire in the primary care

population

Scoring system Area under curve (95% CI) ‘Cut-off’ score Sensitivity Specificity

1 Summed total score 0.82 (0.777–0.868) 7/32 77.3 73.2

2 Summed frequency score 0.83 (0.790–0.876) 4/16 86.0 66.2

3 Summed severity score 0.76 (0.700–0.817) 2/16 80.6 61.0

4 Categorized frequency score 0.79 (0.738–0.836) 2/4 86.1 59.7

5 Categorized severity score 0.73 (0.671–0.787) 1/4 84.2 45.7

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

482 A . F R A S E R et al.

1.00 34

30

26

0.75

Summed total score

22

18

Sensitivity

0.50 14

10

6

0.25

2

–2

Primary care Secondary care

0.00

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00

1 - Specificity Figure 3. Box plot showing the distribution of Short-

Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire summed total scores

Figure 2. Receiver Operating Characteristic curve for the for primary (n ¼ 375) and secondary care (n ¼ 162) pop-

summed total score of the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia ulations. ‘Boxes’ show 25–75th centiles, with the horizon-

Questionnaire. The lines show the most sensitive and spe- tal line representing the mean. ‘Whiskers’ represent the

cific cut-off point for the scoring system. 5th and 95th centiles.

ence was not statistically significant. The summed between these scores was highly statistically signifi-

total score was chosen as the preferred method of cant using the Mann–Whitney U-test (P < 0.0005),

scoring the questionnaire because this scoring system demonstrating that the SF-LDQ was able to discrimi-

had the greatest specificity, giving closer agreement nate between two populations with different preva-

between the sensitivity and specificity, and it also had lence of dyspepsia.

a greater range of possible scores, allowing greater

precision.17 Figure 2 shows the ROC curve for the

Responsiveness to change

summed total score.

Oesophagitis or peptic ulcers was found in 60 of the

162 patients who completed the first questionnaire

Logistic regression analyses

from the secondary care population following endo-

Logistic regression analyses assessed the strength of scopy. These patients were asked to complete a second

the scoring system’s association with the GPs’ diagno- questionnaire following treatment of proven efficacy,

sis. All associations were strongly statistically signifi- 2 months after the endoscopy. This questionnaire was

cant (P < 0.0005). The summed frequency score was returned by 47 patients (78%). Ten patients were

marginally the best predictor of GPs’ diagnosis. How- excluded due to missing data, leaving 37 patients eli-

ever, the difference between the summed total score gible for this analysis.

and the summed frequency score again was not statis- The number of patients with dyspepsia present and

tically significant. absent according to the ‘cut-off’ identified by the sen-

sitivity analysis for the summed total score (seven of

32) was compared before and after treatment (Table 3).

Discriminant validity

Before treatment 89% of patients had dyspepsia com-

Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing pared with 38% after treatment, which was highly sig-

the primary and secondary care populations using the nificant using the McNemar test (P < 0.005). The

summed total scoring system. Figure 3 shows the standardized response mean for this change was 1.1,

range of scores in the two populations. The difference suggesting a large degree of responsiveness.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

D Y S P E P S I A Q U E S T I O N N A I R E V A L I D A T I O N S T U D Y 483

dyspepsia by their GP and had higher mean question-

Table 3. Number of secondary care patients with dyspep-

sia before and after treatment using the summed total naire scores compared with the other subgroups. There

score (n ¼ 37; ‘cut-off’ point ¼ 7 of 32) was little difference between the dyspepsia diagnoses

or questionnaire scores of those with predominant

After treatment

reflux-like or ulcer-like symptoms, suggesting that dif-

ferentiating between these subgroups may not be clin-

Dyspepsia Dyspepsia

present absent Total

ically relevant. There were insufficient numbers of

patients in each subgroup to determine the concurrent

Before treatment validity of the questionnaire scores compared with

Dyspepsia present 14 19 33 GPs diagnosis using ROC curves. As a result, the sensi-

Dyspepsia absent 0 4 4 tivity and specificity of the SF-LDQ for dyspepsia in

Total 14 23 37 these subgroups could not be calculated.

The effect of excluding patients with predominant

Values in bold indicate those partipants who had a change reflux-like symptoms on the concurrent validity of the

in dyspepsia status following treatment. No patients without

dyspepsia developed symptoms following treatment, and 19

SF-LDQ was assessed, to determine the effect of using

patients with dyspepsia were ‘cured’ following treatment. the Rome II definition instead of the 1988 Working

This demonstrates that the questionnaire is responsive to Party definition of dyspepsia. This gave an area under

changes in symptoms. the ROC curve of 0.83 for the summed frequency

score, which was almost identical to the area under

the curve for all patients, including those with

Predominant symptom analysis predominant reflux symptoms (0.82). This suggests

that the SF-LDQ predicts the diagnosis of dyspepsia in

The influence of the predominant (or most trouble- a similar way whether or not patients with predomin-

some) symptom on the GPs’ diagnosis of dyspepsia ant reflux symptoms are included.

and SF-LDQ scores (total and summed frequency) was

assessed in the 364 primary care patients who comple-

ted this question and had a GP diagnosis. Four sub- DISCUSSION

groups were identified reflecting the 1988 Working The SF-LDQ proved to be a sensitive and specific

Party definition of dyspepsia:18 those with predomin- measure, acceptable to patients and suitable for high

ant reflux-like symptoms (heartburn and regurgita- rates of self-completion. The SF-LDQ was responsive

tion); those with predominant ulcer-like symptoms to change and able to differentiate between popula-

(epigastric pain); those with predominant dysmotility- tions with differing prevalence, demonstrating discri-

like symptoms (nausea) and those with no predomin- minant validity. Other dyspepsia questionnaires have

ant symptom. The results are shown in Table 4. also been tested for discriminant validity19–21 provi-

The reflux-like and ulcer-like subgroups contained a ding additional evidence for the construct validity of

higher proportion of patients who were diagnosed with this instrument.

The summed frequency scoring system demonstrated

the greatest concurrent validity when analysed using

Table 4. General practitioner (GP) diagnosis and Short- the area under ROC curves and logistic regression.

Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire scores by symptom However, the difference in concurrent validity between

subgroup this scoring system and the summed total score was

GP diagnosis not statistically significant. The summed total score

Symptom Number (percentage Mean total has a greater range of values (0–32) than the summed

subgroup of patients with dyspepsia) score frequency score (0–16), which gives greater precision.

Rates of non-response to questions about symptom

Reflux-like 92 48 11.4 frequency were very low (0.5–1%), indicating that

Ulcer-like 59 53 10.7

these questions were acceptable. Rates of non-response

Dysmotility-like 97 20 7.9

None of these 116 2 1.1 to questions about symptom severity were higher

All patients 364 26 7.1 (5–6%) indicating that these items were less interpreta-

ble or acceptable to a minority.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

484 A . F R A S E R et al.

The LDQ has previously demonstrated a sensitivity alter the concurrent validity of the SF-LDQ, when

of 80% (95% CI: 65–91%) and a specificity of 79% assessed by the area under the ROC curve for the

(95% CI: 66–89%) in a primary care population.10 summed frequency score. This suggests that using the

These values were marginally higher than the Rome II definition of dyspepsia instead of the 1988

SF-LDQs sensitivity of 77% (95% CI: 68–85%) and Working Party definition has little influence on the

specificity of 73% (95% CI: 68–78%) using the concurrent validity of the SF-LDQ. Both GERD and

summed total score. However, this difference is not dyspepsia have recently been re-defined by the Rome

statistically significant, and even if the SF-LDQ was III panel.36, 37 These changes are designed to aid fur-

slightly less valid than the LDQ, this would be offset ther research in selected subgroups of patients and do

by the increased acceptability, feasibility and reliabil- not alter the nature of symptoms sought as outcome

ity of the shorter self-completed measure.17 The SF- measures for use in uninvestigated patients, where

LDQ had a high level of internal consistency when both reflux symptoms and epigastric pain commonly

tested by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and the item- coexist.

total correlation method, indicating that all of the The correlation between the test–retest SF-LDQ scores

questions in the questionnaire scale were measuring 2 days apart was 0.93, showing a high degree of reliab-

the same underlying construct, producing a high ility. Whilst only 40% of patients returned the second

level of reliability. The SF-LDQ had a higher score questionnaire, this low response rate was not unex-

for Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.90) than the LDQ pected for a primary care sample where most partici-

(0.69),10 suggesting that the shorter form was more pants do not have dyspepsia. The LDQ had a weaker

accurately measuring a single construct. correlation between the two questionnaire scores (0.83)

Assessment of concurrent validity involves compar- when test–retest reliability was assessed,10 but the

ing the questionnaire against a ‘gold standard’. As response rate for the second questionnaire was higher

there is no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis of dyspep- (96% in a secondary care population). Validation of the

sia6, 22, 23 a GPs’ diagnosis was chosen as a quasi-gold SF-LDQ as a postal questionnaire was not carried out in

standard. Validity has been established compared with this study. However, the reliability, validity and respon-

a clinician’s diagnosis in previous studies,10, 19, 24–27 siveness should not be affected by postal completion,

whilst other studies of dyspepsia outcome measures as it is a self-completed instrument. Interpretability and

have used different ‘gold standard’ comparisons to acceptability of the SF-LDQ were demonstrated, sug-

demonstrate concurrent validity, such as generic qual- gesting that the questionnaire should have a good

ity of life scores,28–33 patient self-assessment using response rate. The response rate was only 40% in the

diaries34 and dyspepsia adverse events.35 An alternat- test–retest sample, but it was 78% in the responsiveness

ive approach would have been to compare the SF-LDQ to change sample (secondary care), where dyspepsia

with the LDQ as the gold standard.17 However, the cor- was more salient to the respondents. The SF-LDQ’s

relation between the two questionnaires would have responsiveness to change was highly statistically signi-

been artificially inflated by the presence of four iden- ficant in 37 patients receiving a treatment of known

tical questions. No attempt was made to standardize effectiveness. The standardized response mean values

GPs’ diagnosis through discussion of the 1988 Work- suggested this response to change was large. The LDQ

ing Party definition of dyspepsia with them.18 Stan- was assessed in a similar way and was found to be

dardizing the GPs’ diagnosis in this way would have equally responsive to change, although the standard-

artificially increased the concurrent validity of the ized response mean was not calculated.10 Other studies

SF-LDQ, because the questionnaire is based upon the have used two groups receiving treatment and placebo,

Working Party definitions. in order to compare the responsiveness of the two

It should be emphasized that the SF-LDQ is designed groups.38, 39 However, it is not ethical to use placebos

as an outcome assessment tool and not as a diagnostic except in the context of a randomized-controlled trial,

tool. Although considerable effort has been made by so this was not possible in this study. There was no

the Rome process to disentangle reflux and epigastric alternative method of confirming that a response to

pain, this has not been successful where patients have change had occurred in this study, such as a blinded

not had endoscopic investigation to exclude peptic clinician assessment after treatment or a question on

ulcer and oesophagitis. Exclusion of patients with pre- self-reported global improvement, as the treatments

dominant reflux-like symptoms did not substantially used have proven efficacy.40–42

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

D Y S P E P S I A Q U E S T I O N N A I R E V A L I D A T I O N S T U D Y 485

Three percent of respondents commented that the University of Birmingham. They assisted with patient

text size was too small and a larger version of the recruitment and data entry.

questionnaire should be made available for such

patients in clinical trials. Non-English speaking

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

patients were excluded from this study, but should be

included in clinical dyspepsia trials to increase gener- Adam Fraser: Lead contributor to study design and

alizability. Translation of the SF-LDQ into other lan- planning, conducting the study, data analysis and wri-

guages would alter its characteristics, necessitating ting the manuscript; Brendan C. Delaney: guarantor of

further validation.17, 31 the submission and corresponding author. Contributed

The SF-LDQ is a self-completed outcome measure to study design and planning, and writing the manu-

that assesses both the frequency and severity of dys- script; Alexander C. Ford: responsible for conducting

pepsia symptoms for which acceptability, interpretabil- the secondary care arm of the study at Leeds General

ity, reliability, validity and responsiveness to change Infirmary; Michelle Qume: contributed to conducting

have been demonstrated. It is a precise measure using the study, data entry and analysis and writing the

the summed total score of frequency and severity manuscript; Paul Moayyedi: contributed significantly

responses and has good feasibility due to its brevity. to study design and planning, especially questionnaire

The SF-LDQ meets all the criteria for an outcome development. All authors have checked and approved

measure for dyspepsia in cost-effectiveness trials, and the final draft submitted.

is particularly well suited to primary care trials invol-

ving uninvestigated patients.

STATEMENT OF INTERESTS

Authors’ declaration of personal interests: All authors

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

were employed by the University of Birmingham at

This work was undertaken by Dr Adam Fraser as part the time of this study.

of a Masters in Primary Care degree at the University Declaration of funding interests: The study was fun-

of Birmingham. John C. Duffy provided statistical ded in full by the Medical Research Council as part of

advice at the Department of Primary Care and General the CUBE trial (ISRCTN 87644265). The general prac-

Practice, University of Birmingham. He carried out the tices involved were reimbursed by the Midlands

sensitivity analyses and logistic regression analyses. Research Practices Consortium (MidReC) for each

Val Redman and Beth Hinks are Research Associates at patient enrolled. Gastroenterologists recruited patients

the Department of Primary Care and General Practice, in secondary care without remuneration.

questionnaire survey. BMJ 1998; 316: tional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 1994;

REFERENCES

736–41. 106: 1174–83.

1 Delaney BC, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, et al. 5 Fraser A, Delaney B, Moayyedi P. 9 McColl E. Best Practice in Symptom

The management of dyspepsia: a sys- Symptom-based outcome measures for Assessment: a review. Gut 2004; 53

tematic review. Health Technol Assess dyspepsia and GERD trials: a systematic (Suppl. 4): iv49–54.

2000; 4: 1–189. review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 10 Moayyedi P, Duffett S, Braunholtz D,

2 Talley NJ. Dyspepsia: management 442–52. et al. The Leeds Dyspepsia Question-

guidelines for the millennium. Gut 6 Agreus L. Natural history of dyspepsia. naire: a valid tool for measuring the

2002; 50: 72iv–8. Gut 2002; 50: 2iv–9. presence and severity of dyspepsia. Ali-

3 Torrance GW, Boyle MH, Horwood SP. 7 Sharma N, Donnellan C, Preston C, ment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12: 1257–

Application of multi-attribute utility Delaney B, Duckett G, Moayyedi P. A 62.

theory to measure social preference for systematic review of symptomatic out- 11 Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, et al. Ini-

health states. Oper Res 1982; 30: comes used in oesophagitis drug ther- tial validation of a diagnostic question-

1043–69. apy trials. Gut 2004; 53 (Suppl. 4): naire for gastroesophageal reflux

4 Kind P, Dolan P, Gudex C, Williams A. iv58–65. disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:

Variations in population health status: 8 Talley NJ. A critique of therapeutic tri- 52–7.

results from a United Kingdom national als in Helicobacter pylori-positive func- 12 Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori Eradi-

cation in General Practice: Medical

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

486 A . F R A S E R et al.

Benefits and Health Economics. Leeds: Functional gastroduodenal disorders. 34 Leidy NK, Farup C, Rentz AM,

Institute of Epidemiology and Health Gut 1999; 45 (Suppl. 2): II37–42. Ganoczy D, Koch KL. Patient-based

Services Research, University of Leeds, 24 Greatorex R, Thorpe JA. Clinical assess- assessment in dyspepsia: development

1999. ment of gastro-oesophageal reflux by and validation of Dyspepsia Symptom

13 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. The questionnaire. Br J Clin Pract 1983; 37: Severity Index (DSSI). Dig Dis Sci

English Indices of Deprivation. London: 133–5. 2000; 45: 1172–9.

Neighbourhood Renewal Unit, 2004. 25 Junghard O, Lauritsen K, Talley NJ, 35 Rabeneck L, Wristers K, Goldstein JL,

14 Heading RC. Prevalence of upper gastro- Wiklund IK. Validation of seven graded Eisen G, Dedhiya SD, Burke TA. Reliab-

intestinal symptoms in the general pop- diary cards for severity of dyspeptic ility, validity, and responsiveness of

ulation: a systematic review. Scand symptoms in patients with non-ulcer severity of dyspepsia assessment (SODA)

J Gastroenterol Suppl 1999; 231: 3–8. dyspepsia. Eur J Surg Suppl 1998; 583: in a randomized clinical trial of a COX-

15 Stanghellini V. Three-month prevalence 106–11. 2-specific inhibitor and traditional

rates of gastrointestinal symptoms and 26 Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, NSAID therapy. Am J Gastroenterol

the influence of demographic factors: Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire 2002; 97: 32–9.

results from the Domestic/International for gastroesophageal reflux disease. 36 Drossman DA. The functional gastroin-

Gastroenterology Surveillance Study Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69: 539–47. testinal disorders and the Rome III Pro-

(DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 27 Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, cess. Gastroenterology 2006; 130:

1999; 231: 20–8. Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ III. Assess- 1377–90.

16 Talley Colin-Jones NJD, Koch KL, ment of functional gastrointestinal dis- 37 Vakil N, VanZanten S, John D, Kahrilas

Koch M, Nyren O, Stanghellini V. Func- ease: the bowel disease questionnaire. P, Roger J. The Definition of GERD: a

tional dyspepsia: a classification with Mayo Clin Proc 1990; 65: 1456–79. Global, Evidence-based Consensus.

guidelines for diagnosis and manage- 28 Hu WH, Lam KF, Wong YH, et al. The Los Angeles, USA: Digestive Disease

ment. Gastroenterol Int 1991; 4: 145– Hong Kong index of dyspepsia: a valid- Week, 2006.

60. ated symptom severity questionnaire for 38 Rabeneck L, Cook KF, Wristers K,

17 Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, patients with dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Souchek J, Menke T, Wray NP. SODA

Jones DR. Evaluating patient-based out- Hepatol 2002; 17: 545–51. (severity of dyspepsia assessment): a

come measures for use in clinical trials. 29 Dimenas E, Glise H, Hallerback B, new effective outcome measure for dys-

Health Technol Assess 1998; 2: 1–74. Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I. pepsia-related health. J Clin Epidemiol

18 Management of dyspepsia: report of a Quality of life in patients with upper 2001; 54: 755–65.

working party. Lancet 1988; 1: 576–9. gastrointestinal symptoms. An improved 39 Rothman M, Farup C, Stewart W,

19 Buckley MJ, Scanlon C, McGurgan P, evaluation of treatment regimens? Helbers L, Zeldis J. Symptoms associ-

O’Morain CA. A validated dyspepsia Scand J Gastroenterol 1993; 28: 681–7. ated with gastroesophageal reflux dis-

symptom score. Ital J Gastroenterol 30 Shaw M, Talley NJ, Adlis S, Beebe T, ease: development of a questionnaire

Hepatol 1997; 29: 495–500. Tomshine P, Healey M. Development of for use in clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci

20 Poitras MR, Verrier P, So C, Paquet S, a digestive health status instrument: 2001; 46: 1540–9.

Bouin M, Poitras P. Group counseling tests of scaling assumptions, structure 40 Laine L, Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS. Has the

psychotherapy for patients with func- and reliability in a primary care popula- impact of Helicobacter pylori therapy

tional gastrointestinal disorders: devel- tion. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12: on ulcer recurrence in the United States

opment of new measures for symptom 1067–78. been overstated? A meta-analysis of

severity and quality of life. Dig Dis Sci 31 Goldman J, Conrad DF, Ley C, et al. rigorously designed trials. Am J Gast-

2002; 47: 1297–307. Validation of Spanish language dyspep- roenterol 1998; 93: 1409–15.

21 Calvet X, Bustamante E, Montserrat A, sia questionnaire. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 47: 41 Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM,

et al. Validation of phone interview for 624–40. Hunt RH. Speed of healing and

follow-up in clinical trials on dyspepsia: 32 Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Russell I, et al. symptom relief in grade II to IV gastr-

evaluation of the Glasgow Dyspepsia Developing a condition-specific measure oesophageal reflux disease: a meta-ana-

Severity Score and a Likert-scale symp- of health for patients with dyspepsia lysis. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:

toms test. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol and ulcer-related symptoms. J Clin Epi- 1798–810.

2000; 12: 949–53. demiol 1996; 49: 565–71. 42 Penston JG. Review article: Clinical

22 Dent J. Definitions of reflux disease and 33 Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee aspects of Helicobacter pylori eradica-

its separation from dyspepsia. Gut 2002; S, et al. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life tion therapy in peptic ulcer disease. Ali-

50: 17iv–20. Index: development, validation and ment Pharmacol Ther 1996; 10: 469–86.

23 Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, application of a new instrument. Br J

Koch KL, Malagelada JR, Tytgat GN. Surg 1995; 82: 216–22.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Craap Test WorksheetDokument5 SeitenCraap Test Worksheetapi-272946391Noch keine Bewertungen

- Coeliac Disease and Gluten-Related DisordersVon EverandCoeliac Disease and Gluten-Related DisordersAnnalisa SchiepattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Future of The Humanities and Liberal Arts in A Global AgeDokument30 SeitenThe Future of The Humanities and Liberal Arts in A Global AgeJohn McAteer100% (1)

- The Test of Masticating and Swallowing Solids (TOMASS) : Reliability, Validity and International Normative DataDokument13 SeitenThe Test of Masticating and Swallowing Solids (TOMASS) : Reliability, Validity and International Normative DatamartaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Istqb Questions and AnswersDokument105 SeitenIstqb Questions and Answersnrguru_sun100% (1)

- HSC4537 SyllabusDokument10 SeitenHSC4537 Syllabusmido1770Noch keine Bewertungen

- Laoang Elementary School School Boy Scout Action Plan Objectives Activities Time Frame Persons Involve Resources NeededDokument3 SeitenLaoang Elementary School School Boy Scout Action Plan Objectives Activities Time Frame Persons Involve Resources NeededMillie Lagonilla100% (5)

- Development of The GerdQ, A Tool For The DiagnosisDokument9 SeitenDevelopment of The GerdQ, A Tool For The Diagnosiskaizen C2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Systematic Review: Antacids, H - Receptor Antagonists, Prokinetics, Bismuth and Sucralfate Therapy For Non-Ulcer DyspepsiaDokument13 SeitenSystematic Review: Antacids, H - Receptor Antagonists, Prokinetics, Bismuth and Sucralfate Therapy For Non-Ulcer DyspepsiaAaquib AmirNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2003 A Validated Symptoms Questionnaire Chinese GERDQ For Thediagnosis of Gastro Oesophageal Reflux Disease in The ChinesepopulationDokument7 Seiten2003 A Validated Symptoms Questionnaire Chinese GERDQ For Thediagnosis of Gastro Oesophageal Reflux Disease in The ChinesepopulationAhmad Yar SukheraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating Disorder Diagnostic ScaleDokument4 SeitenEating Disorder Diagnostic ScaleEminencia Garcia PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- DyspepsiaDokument8 SeitenDyspepsiaaspNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence Analysis Library Review of Best Practices For Performing Indirect Calorimetry in Healthy and NoneCritically Ill IndividualsDokument32 SeitenEvidence Analysis Library Review of Best Practices For Performing Indirect Calorimetry in Healthy and NoneCritically Ill IndividualsNutricion Deportiva NutrainerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desjardins 2018Dokument11 SeitenDesjardins 2018pseptinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Validation of The Gerdq Questionnaire For The Diagnosis of Gastro-Oesophageal Re Ux DiseaseDokument9 SeitenValidation of The Gerdq Questionnaire For The Diagnosis of Gastro-Oesophageal Re Ux DiseaseSharan KaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kleinman 2011Dokument9 SeitenKleinman 2011rsthsn6z8xNoch keine Bewertungen

- 624Dokument7 Seiten624debbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- British Society Guidelines Functional DyspepsiaDokument27 SeitenBritish Society Guidelines Functional DyspepsiagigiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diseases of The Esophagus 2017Dokument9 SeitenDiseases of The Esophagus 2017Nimesh ModiNoch keine Bewertungen

- GROUP 4 EBP On Renal NursingDokument7 SeitenGROUP 4 EBP On Renal Nursingczeremar chanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article: Short-Term Treatment With Proton-Pump Inhibitors As A Test For Gastroesophageal Reflux DiseaseDokument11 SeitenArticle: Short-Term Treatment With Proton-Pump Inhibitors As A Test For Gastroesophageal Reflux DiseaseAsni Putra JayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Itopride and DyspepsiaDokument9 SeitenItopride and DyspepsiaRachmat AnsyoriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines For The Surgical Treatment of Esophageal Achalasia PDFDokument24 SeitenGuidelines For The Surgical Treatment of Esophageal Achalasia PDFInomy ClaudiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aliment Pharmacol Ther - 2003 - FRANCIS - The Irritable Bowel Severity Scoring System A Simple Method of MonitoringDokument8 SeitenAliment Pharmacol Ther - 2003 - FRANCIS - The Irritable Bowel Severity Scoring System A Simple Method of MonitoringsandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7826 PDFDokument6 Seiten7826 PDFIka SalehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disfagia PDFDokument11 SeitenDisfagia PDFRonald MoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Noutati Din Diagnosticarea AstmuluiDokument1 SeiteNoutati Din Diagnosticarea AstmuluiPetrescu MihaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Validity and Reliability of The Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) 2003Dokument6 SeitenValidity and Reliability of The Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) 2003draanalordonezv1991Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anorectal Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis A SystDokument10 SeitenAnorectal Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis A SystactualashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anorectal Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis A SystDokument10 SeitenAnorectal Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis A SystactualashNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Development of The GERD-HRQL Symptom Severity InstrumentDokument5 SeitenThe Development of The GERD-HRQL Symptom Severity InstrumentAndrés MaldonadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Prevalence of Rome IV Nonerosive Esophageal Phenotypes in ChildrenDokument6 SeitenThe Prevalence of Rome IV Nonerosive Esophageal Phenotypes in ChildrenJonathan SaveroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gcsi PDFDokument12 SeitenGcsi PDFnadiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ford 2020Dokument14 SeitenFord 2020Indra WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art. - Qual - of Life AsthmaDokument6 SeitenArt. - Qual - of Life AsthmaMaria MariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Dysphagia Tto PoststrokeDokument7 SeitenReview Dysphagia Tto PoststrokeTrinidad OdaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- A12 PDFDokument25 SeitenA12 PDFjoelrequenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal GERD 3Dokument8 SeitenJurnal GERD 3cici angraini angrainiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moayyedi P The Effect of Fiber Supplementation On IrritableDokument8 SeitenMoayyedi P The Effect of Fiber Supplementation On Irritableoliffasalma atthahirohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive Impairment in Coeliac Disease Improves On A Gluten-Free Diet and Correlates With Histological and Serological Indices of Disease SeverityDokument11 SeitenCognitive Impairment in Coeliac Disease Improves On A Gluten-Free Diet and Correlates With Histological and Serological Indices of Disease SeverityAnaaaerobiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstract. The Dysphagia Outcome and Severity ScaleDokument7 SeitenAbstract. The Dysphagia Outcome and Severity ScaleWallace HongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gideon 2016Dokument19 SeitenGideon 2016pentrucanva1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Review of LiteratureDokument16 SeitenReview of Literatureakhils.igjNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5as Physical ActivityDokument7 Seiten5as Physical ActivityCarolina PaezNoch keine Bewertungen

- King's Research Portal: Citing This PaperDokument24 SeitenKing's Research Portal: Citing This PaperShishirGaziNoch keine Bewertungen

- British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines On The Management of Functional DyspepsiaDokument27 SeitenBritish Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines On The Management of Functional DyspepsiaRicardo PaterninaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GatroDokument48 SeitenGatronainggolan Debora15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Scores For Dyspnoea Severity in Children: A Prospective Validation StudyDokument11 SeitenClinical Scores For Dyspnoea Severity in Children: A Prospective Validation StudyMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pi Is 1542356517309278Dokument11 SeitenPi Is 1542356517309278Putri SaharaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LkjkusteiDokument8 SeitenLkjkusteiPeriyasami GovindasamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dysphagia Handicap Index, Development and ValidationDokument7 SeitenDysphagia Handicap Index, Development and ValidationWlf OoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mayo ScoreDokument7 SeitenMayo ScoreBruno LorenzettoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH01 FinalDokument14 SeitenCH01 FinalSharmaineTaguitagOmliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients A Systematic ReviewDokument13 SeitenEfficacy of Dietary Interventions in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients A Systematic ReviewKhusnu Waskithoningtyas NugrohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eda 5Dokument22 SeitenEda 5Eminencia Garcia PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIIS1098301518308854Dokument1 SeitePIIS1098301518308854Angga PratamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioural Intervention For Dysphagia in Acute Stroke A Randomised Controlled Trial PDFDokument7 SeitenBehavioural Intervention For Dysphagia in Acute Stroke A Randomised Controlled Trial PDFmichelle montesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eight Weeks of Esomeprazole Therapy Reduces Symptom Relapse, Compared With 4 Weeks, in Patients With Los Angeles Grade A or B Erosive EsophagitisDokument9 SeitenEight Weeks of Esomeprazole Therapy Reduces Symptom Relapse, Compared With 4 Weeks, in Patients With Los Angeles Grade A or B Erosive EsophagitisBeau PhatruetaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alginate TherapyDokument12 SeitenAlginate TherapySMJ DRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessing Fatigue in The ESRD Patient: A Step Forward: Related Article, P. 327Dokument3 SeitenAssessing Fatigue in The ESRD Patient: A Step Forward: Related Article, P. 327Rina FebriantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Algoritma GerdDokument14 SeitenAlgoritma GerdBintang AnjaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- MeduriDokument4 SeitenMeduriSilvia Leticia BrunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alzheimer PicoDokument6 SeitenAlzheimer PicoRaja Friska YulandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalVon EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation and Management of Dysphagia: An Evidence-Based ApproachVon EverandEvaluation and Management of Dysphagia: An Evidence-Based ApproachDhyanesh A. PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2005 Talley Self Rated DyspepsiaDokument7 Seiten2005 Talley Self Rated Dyspepsianermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 EngelDokument5 Seiten2014 Engelnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- Psychiatry Research: Tsuo-Hung Lan, Bo-Jian Wu, Hsing-Kang Chen, Hsun-Yi Liao, Shin-Min Lee, Hsiao-Ju SunDokument7 SeitenPsychiatry Research: Tsuo-Hung Lan, Bo-Jian Wu, Hsing-Kang Chen, Hsun-Yi Liao, Shin-Min Lee, Hsiao-Ju Sunnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Zhaocai - Self Control Gender CHINADokument6 Seiten2017 Zhaocai - Self Control Gender CHINAnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 GonzálezDokument8 Seiten2012 Gonzáleznermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 PotardDokument6 Seiten2014 Potardnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 RebecaDokument5 Seiten2014 Rebecanermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- Author's Accepted Manuscript: Psychiatry ResearchDokument17 SeitenAuthor's Accepted Manuscript: Psychiatry Researchnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 HaoDokument7 Seiten2015 Haonermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 WahabDokument6 Seiten2015 Wahabnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 JeanDokument5 Seiten2016 Jeannermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 WeiDokument10 Seiten2016 Weinermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 InnamoratiDokument6 Seiten2016 Innamoratinermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 WangDokument5 Seiten2016 Wangnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 Shrivastava Mainstreaming of Ayurveda Yoga Naturopathy Unani Siddha and Homeopathy With The Health Care Delivery System in IndiaDokument3 Seiten2015 Shrivastava Mainstreaming of Ayurveda Yoga Naturopathy Unani Siddha and Homeopathy With The Health Care Delivery System in Indianermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Bajaj Mediating Role of Self Esteem On The Relationship Between Mindfulness Anxiety and DepressionDokument5 Seiten2016 Bajaj Mediating Role of Self Esteem On The Relationship Between Mindfulness Anxiety and Depressionnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Chandra Ayurvedic Research Wellness and Consumer RightsDokument5 Seiten2016 Chandra Ayurvedic Research Wellness and Consumer Rightsnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Lin Shortened Telomere Length in Patients With Depression A Meta Analytic StudyDokument10 Seiten2016 Lin Shortened Telomere Length in Patients With Depression A Meta Analytic Studynermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Singh Ayurvedic Approach For Management of Ankylosing Spondylitis A Case ReportDokument4 Seiten2016 Singh Ayurvedic Approach For Management of Ankylosing Spondylitis A Case Reportnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Silvia RaynaudphenomenonDokument8 Seiten2016 Silvia Raynaudphenomenonnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Hughes Raynaud's PhenomenonDokument21 Seiten2016 Hughes Raynaud's Phenomenonnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 O Neill Anxiety and Depression Symptomatology in Adult Siblings of Individuals With Different Developmental Disability DiagnosesDokument10 Seiten2016 O Neill Anxiety and Depression Symptomatology in Adult Siblings of Individuals With Different Developmental Disability Diagnosesnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1998 - Coercion and Punishment in Long-Term Perspectives - McCordDokument405 Seiten1998 - Coercion and Punishment in Long-Term Perspectives - McCordnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Norr The Role of Anxiety Sensitivity Cognitive Concerns in Suicidal Ideation A Test of The Depression Distress Amplification Model in Clinical OuDokument7 Seiten2016 Norr The Role of Anxiety Sensitivity Cognitive Concerns in Suicidal Ideation A Test of The Depression Distress Amplification Model in Clinical Ounermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2009 - Blending Play Therapy With Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy - DrewesDokument547 Seiten2009 - Blending Play Therapy With Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy - Drewesnermal93100% (1)

- 2010 - Identifying, Assessing, and Treating Early Onset Schizophrenia at School - Li, Pearrow & JimersonDokument160 Seiten2010 - Identifying, Assessing, and Treating Early Onset Schizophrenia at School - Li, Pearrow & Jimersonnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- Joints and Glands Kanpur SeriesDokument19 SeitenJoints and Glands Kanpur Seriesnermal93100% (2)

- Wilber Metagenius-Part1Dokument15 SeitenWilber Metagenius-Part1nermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1969 PAHNKE - The Psychedelic Mystical Experience in The Human Encounter With DeathDokument22 Seiten1969 PAHNKE - The Psychedelic Mystical Experience in The Human Encounter With Deathnermal93100% (1)

- Cavite State University: Cvsu Vision Cvsu MissionDokument3 SeitenCavite State University: Cvsu Vision Cvsu Missionrose may batallerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 67-CS Electrical TechnologyDokument5 Seiten67-CS Electrical TechnologyMD. ATIKUZZAMANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Candy Science Experiment Using Skittles® To Show Diffusion - NurtureStoreDokument25 SeitenCandy Science Experiment Using Skittles® To Show Diffusion - NurtureStoreVictoria RadchenkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- June 2015 QP - Unit 2 Edexcel Biology A-LevelDokument28 SeitenJune 2015 QP - Unit 2 Edexcel Biology A-LevelSimonChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 13 Family and MarriagesDokument14 SeitenWeek 13 Family and Marriagesnimra khaliqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Reflective Techniques - Ilumin, Paula Joy DDokument2 SeitenCritical Reflective Techniques - Ilumin, Paula Joy DPaula Joy IluminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supa TomlinDokument33 SeitenSupa TomlinDiya JosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- GIYA Teachers G1 3 CDokument3 SeitenGIYA Teachers G1 3 CCHARLYH C. ANDRIANO100% (2)

- Rpms Portfolio 2023-2024 LabelsDokument44 SeitenRpms Portfolio 2023-2024 LabelsJAMES PAUL HISTORILLONoch keine Bewertungen

- Is Lacans Theory of The Mirror Stage Still ValidDokument10 SeitenIs Lacans Theory of The Mirror Stage Still ValidEmin MammadovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral and Psychophysiological Effects of A Yoga Intervention On High-Risk Adolescents - A Randomized Control TriaDokument13 SeitenBehavioral and Psychophysiological Effects of A Yoga Intervention On High-Risk Adolescents - A Randomized Control TriaSandra QuinonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- KISHAN RANGEELE - ProfileDokument1 SeiteKISHAN RANGEELE - ProfileKishankumar RangeeleNoch keine Bewertungen

- AQA GCSE Maths Foundation Paper 1 Mark Scheme November 2022Dokument30 SeitenAQA GCSE Maths Foundation Paper 1 Mark Scheme November 2022CCSC124-Soham MaityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questions About The Certification and The Exams 1Dokument7 SeitenQuestions About The Certification and The Exams 1Godson0% (1)

- Testing&certificationoffirefightingequipment11 02 13 PDFDokument8 SeitenTesting&certificationoffirefightingequipment11 02 13 PDFkushalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Psychoanalytic Theory: Clues From The Brain: Commentary by Joseph LeDoux (New York)Dokument7 Seiten6 Psychoanalytic Theory: Clues From The Brain: Commentary by Joseph LeDoux (New York)Maximiliano PortilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- ch14Dokument7 Seitench14Ahmed AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan in Physical EducationDokument4 SeitenLesson Plan in Physical EducationGemmalyn DeVilla De CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Policy Brief Social MediaDokument3 SeitenPolicy Brief Social MediabygskyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Components To The Teacher: What Is Top Notch? ActiveteachDokument1 SeiteComponents To The Teacher: What Is Top Notch? ActiveteachMikelyn AndersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- INTERNATIONAL INDIAN SCHOOL AL JUBAIL IISJ ProspectusDokument7 SeitenINTERNATIONAL INDIAN SCHOOL AL JUBAIL IISJ ProspectusMubeen NavazNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Operational and Financial Performance of Canara BankDokument11 SeitenA Study On Operational and Financial Performance of Canara Bankshrivathsa upadhyayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ishita MalikDokument10 SeitenIshita MalikIshita malikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yasmin Akhtar - Speech Therapy For Kids - Libgen - LiDokument84 SeitenYasmin Akhtar - Speech Therapy For Kids - Libgen - Liickng7100% (1)

- Sociology CH 3. S. 2Dokument15 SeitenSociology CH 3. S. 2Kyla Mae AceroNoch keine Bewertungen