Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Make Money Surfing The Web? The Impact of Internet Use On The Earnings of U.S. Workers

Hochgeladen von

franciscoOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Make Money Surfing The Web? The Impact of Internet Use On The Earnings of U.S. Workers

Hochgeladen von

franciscoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Make Money Surfing the Web?

The Impact of Internet Use

on the Earnings of U.S. Workers

Paul DiMaggio Bart Bonikowski

Princeton University Princeton University

Much research on the “digital divide” presumes that adults who do not use the Internet

are economically disadvantaged, yet little research has tested this premise. After

discussing several mechanisms that might produce differences in earnings growth between

workers who do and do not use the Internet, we use data from the Current Population

Survey to examine the impact of Internet use on changes in earnings over 13-month

intervals at the end of the “Internet boom.” Our analyses reveal robustly significant

positive associations between Web use and earnings growth, indicating that some skills

and behaviors associated with Internet use were rewarded by the labor market. Consistent

with human-capital theory, current use at work had the strongest effect on earnings. In

contrast to economic theory (which has led economists to focus exclusively on effects of

contemporaneous workplace technology use), workers who used the Internet only at home

also did better, suggesting that users may have benefited from superior access to job

information or from signaling effects of using a fashionable technology. The positive

association between computer use and earnings appears to reflect the effect of Internet

use, rather than use of computers for offline tasks. These results suggest that inequality in

access to and mastery of technology is a valid concern for students of social stratification.

ith the emergence of the Internet as a makers and scholars became concerned about

W popular means of communication and the “digital divide”—the emerging gulf between

people with access to the Internet and those

information retrieval in the mid-1990s, policy-

without. The literature on the digital divide has

grown in size and sophistication: Whereas early

Direct correspondence to Paul DiMaggio, work simply documented and tracked inter-

Sociology Department, 118 Wallace Hall, Princeton group differences, more recent research attempts

University, Princeton, NJ 08540 (dimaggio@ to explain such differences statistically. Recent

princeton.edu). Support for this article’s research

research also explores digital inequality within

from the National Science Foundation, the Russell

Sage Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation is

the online population in extent and types of

gratefully acknowledged. We benefited from the use, autonomy of use, and the effectiveness

opportunity to present this work at the Princeton with which desired information can be retrieved

International Conference on Inequality (Spring 2006); (DiMaggio et al. 2004).

the Internet and Society session at the American Much of this work is motivated by a faith that

Sociological Association meetings (August 2006, access to the Internet and the ability to use it

Montreal); and the Princeton University Economic effectively is an important form of human cap-

Sociology Workshop (September 2006). We are espe- ital that influences labor-market success. An

cially grateful to Betsy Stevenson for perceptive and

early study of the digital divide warned that

helpful critical comments. We also received helpful

advice and feedback from Eszter Hargittai, Alan

“the consequences to American society” of

Krueger, Scott Lynch, Peter Meyers, Dick Murnane, racial inequality in Internet access “are expect-

Devah Pager, Jake Rosenfeld, Martin Ruef, Bruce ed to be severe” and noted that “the Internet may

Western, and three anonymous reviewers, none of provide for equal opportunity .|.|. but only for

whom is accountable for the sins of the authors. those with access” (Hoffman and Novak

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW, 2008, VOL. 73 (April:227–250)

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

228—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

1998:390). A more recent article makes a sim- LIMITATIONS OF EXISTING

ilar point: “The ‘Digital Divide’ may have seri- RESEARCH ON THE EFFECTS OF

ous economic consequences for disadvantaged TECHNOLOGY USE ON EARNINGS

minority groups as information technology skills

become increasingly important in the labor mar- Research on organizations suggests that com-

ket” (Fairlie 2004). mand of new technologies increases the power

Many policymakers share this faith. For and centrality to the labor process of those who

example, the Statement of Findings for Illinois’s possess it. For example, Barley (1986) report-

2000 “Eliminate the Digital Divide” Act notes ed that the introduction of CT scanners in hos-

the existence of a “digital divide” and asserts as pital radiology labs enhanced the status and

settled fact that citizens who have mastered and autonomy of technicians trained to use them,

have access to “the tools of the new digital tech- empowering such technicians in their relations

nology” have “benefited in the form of improved with senior radiologists, to whom the new meth-

employment possibilities and a higher standard ods were unfamiliar. Kapitzke (2000) found

of life,” whereas those without access to and similar dynamics when computers were intro-

mastery of the technology “are increasingly duced into public schools.

constrained to marginal employment and a stan- Researchers have not determined, however,

dard of living near the poverty level” (Illinois whether such increments in power are convert-

General Assembly 2000, Section I–5). ed into higher earnings. Indeed, sociologists

Although we have learned much about the who study inequality rarely ask whether varia-

nature and causes of inequality in access to and tion in access to or command of new technolo-

use of the Internet, we know surprisingly little gies influences individual life chances.

about such inequality’s effects on individual Economists have addressed this question more

mobility. To be sure, there are other reasons to thoroughly and have found positive impacts of

worry about the digital divide: Internet use is computer use on earnings (Krueger 1993). Very

becoming necessary for certain kinds of social little economic research, though, addresses

and political participation and for access to Internet use. Moreover, most economic studies

some private markets and government services of effects of technology use on earnings exhib-

(Fountain 2001). Ultimately, however, the expec- it two shortcomings. First, they usually employ

tation that people without Internet access are cross-sectional data. Second, they assume that

disadvantaged in their pursuit of good jobs and technology use influences income through a

adequate incomes is a central basis for concern single mechanism, specifically the increase in

about the digital divide. Determining whether human capital and productivity.

this expectation is justified is therefore an Some economists have called for employing

important priority for research. longitudinal data and using other means to coun-

In an era in which rapid technological change teract the effects of bias inherent in (but not lim-

has become the norm, the digital divide is sig- ited to) cross-sectional designs (Card and

nificant for students of social stratification as DiNardo 2002; DiNardo and Pischke 1997).

an example of what many believe to be the The obvious problem is reciprocity bias: work-

increasingly important influence of technolog- ers may adopt a new technology because they

ical access and know-how on social inequality. are better paid (and can therefore afford it)

Tilly (2005:118, 120), for example, asks, “To rather than being paid better because they use

what extent and how does unequal control over the technology. Cross-sectional studies are also

the production and distribution of knowledge vulnerable to three kinds of selectivity bias.

generate or sustain” inequality? He contends First, employers may choose their highest-qual-

that control over information, science, and ity workers to implement new technologies.

“media for storage and transmission of capital, Earnings advantages that appear to be caused by

information and scientific-technical knowl- the use of new technology may thus reflect

edge” are “newly prominent bundles of value- unmeasured variation in human capital (Entorf

producing resources” that have displaced and Kramarz 1997). Second, successful firms

ownership of the material means of production with slack resources may adopt new technolo-

as the primary bases of intergroup inequality. gies sooner than their less successful competi-

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–229

tors and pay their employees higher wages the workplace) and that may affect earnings

(Domes, Dunne, and Troske 1997). Third, firms independently.1 Third, the focus on current

with skilled (and highly paid) workers can more Internet use neglects research indicating that

easily implement technological changes requir- experience leads to more effective use, which

ing an educated work force than can those with suggests that returns to current users should be

less well-trained employees (Acemoglu 2002). higher for those with more accumulated expe-

This produces additional opportunities for spu- rience (Eastin and LaRose 2000; Hargittai

rious correlation between technology use and 2003).

earnings. A confident assessment of the impact of

The second problem with existing research is Internet use on earnings requires that we do the

that economists have restricted their hypothesis- following: (1) Go beyond cross-sectional analy-

testing to a single mechanism: technology use ses to examine the influence of technology use

increases human capital, which in turn boosts on earnings change over time. (2) Control for

productivity, which leads to higher wages. From as many individual differences that may be asso-

a sociological perspective, this view is unnec- ciated with both earnings and technology use as

essarily narrow. Earnings may be determined not possible, including occupation and industry

only by productivity (correctly appraised) but characteristics. (3) Distinguish between types of

also by efforts of groups or networks of work- Internet use and include independent measures

ers to monopolize access to certain skills of Internet use at home and in the past, as well

(monopolistic closure [Weber 1978:336]), to as measures of current Internet use on the job.2

use social ties to receive disproportionate access We take the following three steps to accom-

to desirable jobs (opportunity hoarding [Tilly plish these goals:

1998]), or to employ culturally embedded sta- 1. Panel data. We exploit a fortuitous feature

tus cues to signal virtue and ability (cultural cap- of the Current Population Survey (CPS) to pro-

ital [Bourdieu 1986]). (Economists refer to such duce a panel with two measures of both Internet

devices as “rent-seeking” but regard them as less use and earnings. Through 2003, the CPS con-

central and ubiquitous features of labor markets ducted periodic surveys of respondents’ use of

than do most sociologists.) communications technologies and took multi-

Because of their preoccupation with earn- ple measures of respondents’ incomes. CPS

ings increases caused by workplace productiv-

ity enhancement, economists’ empirical efforts

have focused almost exclusively on examining 1

the impact on earnings of current technology use Note that we do not question the importance of

the human-capital/productivity-enhancement mech-

in the workplace. By contrast, we believe that

anism. Indeed, we shall argue (on empirical grounds)

an exclusive focus on the human-capital/

that it is probably the most important mechanism

productivity-enhancement mechanism produces connecting Internet use to earnings. Nonetheless,

three kinds of mischief. First, it leads one to ne- we believe that attention to other mechanisms is nec-

glect two other mechanisms by which workers essary both to assess the full effect of technology use

may gain earnings advantages: social- on earnings and to gain leverage over potential rec-

capital/information-hoarding (i.e., the use of iprocity bias.

2 Internet use is, of course, differentiated in many

technology to gain privileged access to infor-

mation about desirable jobs) and cultural- other ways. Jung, Qiu, and Kim (2001) note that

capital/signaling (i.e., the use of technology to Internet users vary markedly on several dimensions

signal positive qualities that the worker may or of intensity and scope of use, and they produced an

may not possess). Second, an exclusive empha- index of “Internet connectedness” to tap such dif-

ferences. DiMaggio and colleagues (2004) likewise

sis on human-capital/productivity-enhancement

distinguish several dimensions of variation among

leads analysts to rely on measures of technolo- Internet users (degree of access and freedom from

gy use—current use at work—for which the surveillance, quality of available technology, skill,

potential for endogeneity related to employer social support, and type of use) that they view as pre-

decisions is greatest, and to neglect measures of dictive of rewards. Exploring such variation is a wor-

technology use that are less likely to be affect- thy objective but it is beyond the scope of this article

ed by employers (e.g., prior use or use outside and the capacity of existing data.

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

230—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

empanels respondents for a span of 16 months. ures of technology use at work and at home, and

Two of their periodic surveys of communications- separate measures of Internet use at two points

technology use, in 2000 and 2001, captured in time.

several thousand employed respondents toward The CPS data offer substantial purchase on

the beginning and end of their periods of empan- the relationship between Internet use and earn-

elment. It was thus possible to explore the ings for U.S. workers at the turn of the twenty-

impact of Internet use on earnings change over first century. We first look at the relative

a 13-month interval. To our knowledge this is earnings gains of consistent Internet users, new

the first study to exploit this feature to study the adopters, and disadopters (compared to never-

over-time effects of Internet use on earnings. users) between 2000 and 2001. Next we explore

2. Controls for other factors affecting income. the effects of Internet use at home as compared

Including lagged wages in a wage-determina- to Internet use in the workplace. Finally, after

tion model helps to correct for selectivity bias, testing several model specifications to examine

but other factors may influence both technolo- the models’ robustness to differing assump-

gy use and the rate at which wages rise. It is tions, we evaluate the hypothesis that gains

therefore important to include a variety of addi- result from computer use per se rather than

tional controls and to employ additional means from Internet use. First, though, we discuss in

of correcting for possible selectivity bias. The more detail the mechanisms—human-

CPS sample’s large size enables us to explore capital/productivity-enhancement, social-

differences in the effects of Internet use asso- capital/information-hoarding, and cultural-capital/

ciated with industry, occupation, and job-spe- signaling—that might lead us to expect, and

cific skill requirements, as well as educational enable us to explain, an association between

attainment, union membership, gender, race Internet use and wages.

and Hispanic ethnicity, marital status, age, and

place and region of residence. We also employ EXPLAINING THE RELATIONSHIP

propensity-score matching to address sample

BETWEEN INTERNET USE AND

selection bias based on observable characteris-

EARNINGS

tics of Internet users and nonusers. We use

change-score models to address selectivity on Why might we expect to find positive empiri-

unobserved characteristics, the effects of which cal associations between Internet use and earn-

are not incorporated in the lagged term. ings (and, more generally, between technology

3. Distinguishing among types of Internet use and socioeconomic achievement)? Whereas

use. Almost all economic accounts posit that most work in economics focuses on mecha-

technology-linked wage gains reflect enhanced nisms that link technology use to worker pro-

productivity due to the use of the new technol- ductivity and thence to earnings (summarized

ogy at work. In contrast, we argue that Internet below under the heading of “Internet Use as a

use may also contribute to earnings by enhanc- Form of Human Capital .|.|. ”), we describe

ing access to labor-market information and by additional mechanisms that link technology use

serving as a signal of status or competence. We to better labor-market information and social

use measures of Internet use from the 2000 and networks (“social capital/information-

2001 CPS Internet modules to divide our sam- hoarding”) and to a worker’s ability to establish

ple into groups of nonusers, consistent users, a positive face (Goffman 1955) before potential

adopters (nonusers in 2000 who were users in and actual employers (“cultural capital/

2001), and disadopters (Internet users in 2000 signaling”).

but not 2001). We also use the CPS to compare

the impact on earnings, respectively, of Internet

SKILL ONLINE

use at work and at home. The latter is less like-

ly to be a product of firm-level decisions than We begin by anticipating an objection from

is Internet use at work, and therefore it is less Internet-savvy academic readers to our focus on

likely to be a function of unmeasured employ- long-term use and home use. Even if new

er characteristics that influence both workplace employees have not used the Internet at home

technology and wages. We believe this is the or in a previous job, can they not pick up the

first earnings study to use both separate meas- necessary skills quickly? Finding information

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–231

and communicating with other people online, INTERNET USE AS A FORM OF HUMAN

after all, is not rocket science. CAPITAL LEADING TO ENHANCED

This objection underestimates the strange- PRODUCTIVITY

ness of cyberspace to neophytes, the difficulty In some occupations in some industries, work-

of mastering online search and communication ers who can use the Internet effectively may

skills for workers without previous experience, perform better than those who cannot, and they

and the range of competencies that Internet use will therefore have privileged access to desirable

entails. New users must (1) understand graph- jobs, be rewarded more generously for their

ic conventions prevalent in web design (e.g., the performance, or both. According to human-

difference between a list and a drop-down menu) capital theory, a wage premium for Internet use

and learn the cues that make it easy for experi- would reflect productivity gains that result from

enced users to tell one from the other; (2) improved access to information, faster and more

efficient communication, greater access to

acquire a mental map of the Internet as a “space”

learning opportunities, or higher job satisfaction

across which one can “navigate,” and master the leading to greater job commitment. Krueger’s

instrumentalities (e.g., hyperlinks, URLs, search (1993) classic study of the effects of computer

engines) through which one can do so; (3) learn use on earnings reported that workers who used

the basics of online searches (e.g., generating computers earned 17 to 20 percent more than

queries that are neither too broad nor too nar- those who did not (see also, Autor, Katz, and

row, using Boolean operators to refine a search); Krueger 1998; in the United Kingdom,

(4) acquire information about the uses and rep- Dickerson and Green 2004). Two rare studies of

utations of major Web sites; (5) develop skill in Internet users, employing cross-sectional data

distinguishing between trustworthy online infor- on workplace Internet use, reported a 13.5 per-

cent premium in 1998 (Goss and Phillips 2002)

mation sources and amateurish or misleading

and a 14 percent premium (controlling for com-

sites; and (6) master the pragmatics of online puter use) in 2001 (Freeman 2002). The eco-

communicative competence (e.g., knowing nomic theory of skill-biased technological

when it is appropriate to contact a stranger or change suggests that such wage premiums are

participate in an online forum, the appropriate temporary, because employers adopt new tech-

formality of address, appropriate message length nologies that require them to increase the ratio

and content, and use of abbreviations and emoti- of skilled to unskilled workers only when the

cons) (Van Dijk 2005, chap. 5; Warschauer former are relatively plentiful (Acemoglu 2002),

2003). and saturation of demand eventually causes

Not surprisingly, research demonstrates that returns to flatten or decline.

In many technologically oriented industries,

new users are less effective and more scattered

familiarity with the Internet is necessary to

in their use of the Internet than more experi-

obtain a job in the first place. For example,

enced users. A psychological study of Internet some auto-parts distributors provide job train-

use concluded that most people take at least ing for new salespersons only offsite over the

two years to become competent at finding infor- Internet. The ability to retrieve information

mation online (Eastin and LaRose 2000). The online is an important part of many workers’

most comprehensive sociological study of online daily routines: secretaries, for example, use the

skills (Hargittai 2003) found low and variable Internet to retrieve contact information, find

levels of skill in a random sample of Internet references to research reports, organize meet-

users from a socially heterogeneous county in ings, and locate statistical data. Indeed, the

the Northeast, with years of experience and Department of Labor’s Occupational Outlook

includes “conduct research on the Internet” in

intensity of use serving as strong predictors of

the job description for secretaries (Levy and

the success and rapidity with which subjects Murnane 2004:4). Some workers, such as cus-

completed a variety of online tasks. In other tomer service representatives who respond to

words, research indicates that effective use of the online inquiries, or purchasing agents who trawl

Internet requires signif icant training or through business-to-business ecommerce sites,

experience. may spend most of their working time online.

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

232—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

The theory of skill-biased change implies For example, the first author interviewed a sales

that highly educated workers are most likely to representative who found a better job when a

benefit from new technologies. But as Autor, professional acquaintance he had not seen in

Levy, and Murnane (2003) note, the critical years stumbled upon his résumé on an online

feature of jobs in which occupants benefit from employment site. Third, employees with large,

technological change is not skill per se but accessible professional networks may use tech-

impediments to routinization. Drivers for many nology to employ these networks in ways that

trucking fleets, for example, use the Internet to benefit their employers: for example, getting

receive information about route changes, report useful information, contacting clients, or setting

deliveries, and maintain contact with their home up collaborative ventures.

offices (Nagarajan, Bander, and White 1999). Efforts to assess the impact of Internet search

Police departments frequently issue officers methods on employment outcomes have focused

laptops to report and receive information about on low-income job-seekers and yielded incon-

crimes and other matters over dedicated wire- sistent results. In a study of 662 unemployed

less networks (Downs 2006). Some universities persons tracked by CPS in 1998 and 2000,

require custodial staff to log in for assignments Fountain (2005) found that Internet searchers

at the beginning of the work day. The ability to were more likely to find jobs in 1998 but not in

use the Internet (or intranets based on Internet 2000. Using similar CPS data, Kuhn and

technology) may thus be necessary even for Skuterud (2004) found no contribution of

blue-collar or service workers if their jobs can- Internet searching to job placement. In con-

not easily be routinized. trast, a 2003 study of Florida welfare recipients

Technology use also may be associated with who had moved into the labor market reported

higher wages if firms invest in worker human that Internet search intensity (but not offline

capital when they implement new technologies. search intensity) was significantly associated

For example, implementation of online with both earnings and benefits (McDonald

inventory-management plans may be associat- and Crew 2006).

ed with intensive employee training and skill-

enhancing reorganization of the labor process INTERNET USE AS CULTURAL RESOURCE

(Fernandez 2001). AND SIGNAL

INTERNET USE AS A SOURCE OF Throughout modern history, new technologies

have galvanized the popular imagination,

SOCIAL CAPITAL

entered into everyday language and literature,

The Internet may also intervene in the earnings- and provided prisms through which actors have

determination process by facilitating the expan- experienced and interpreted their times. In the

sion and exploitation of social networks (Lin age of railways, the locomotive was a metaphor

2001). Internet users may benefit from three for driving force. Henry Adams famously used

kinds of social-capital enhancement. First, they the “dynamo” in his Autobiography to symbol-

can use the Internet to search online job listings ize American society during the industrial rev-

or post their résumés. A 2006 survey reports that olution. Children’s author James Braden’s Auto

almost one in four workers who use computers Boys series drew on (and contributed to) the

at work have used them to search for new jobs motor craze of the early twentieth century.

(Hudson Employment Index 2006). Such work- Sinclair Lewis’s The Flight of the Hawk docu-

ers are likely to learn about many more open- mented the heady social world of aviation as that

ings than would otherwise come to their technology emerged in the 1920s. In each

attention. Second, when online activities lead instance, cultural enthusiasm accompanied

workers to expand their personal social net- financial speculation to create a boom with

works, incidentally created new ties may provide material and symbolic dimensions. The com-

access to informal information about job oppor- mercialization of the Internet in the second half

tunities within or outside the firm (Fountain of the 1990s reproduced this pattern once again

2005; Hampton and Wellman 2000). Online (Castells 2001; Turner 2006).

communications may also complement rather Significant emerging technologies possess a

than substitute for face-to-face relationships. cachet that marks their users as capable, adapt-

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–233

able, and well informed. When this occurs, a attached itself to workers who seemed knowl-

wage premium may reflect both the symbolic edgeable about the new technology.

value that employers attach to familiarity with Some evidence supports the view that

the technology and the personal qualities (com- employers regarded Internet users as especial-

petence, resourcefulness, intelligence) of which ly able. Niles and Hanson (2003:1236) report

they take it to be a signal (Weiss 1995), espe- that some employers used Internet job postings

cially where direct evidence of those qualities to weed out low-quality applicants, whom they

is difficult to come by. Technology use may presumed would not be online. An experimen-

also serve as a kind of “cultural capital”: famil- tal study of the impact of race and other factors

iarity with high-status objects or activities that on employer responses to otherwise randomized

makes it easier for people to form relations with résumés reports that (fictional) applicants with

high-status others and leads gatekeepers to eval- e-mail addresses on their résumés received sig-

uate them favorably (Bourdieu 1986; DiMaggio nificantly more calls for interviews than simi-

2004). lar applicants without them (Bertrand and

Our data were collected toward the end of the Mullainathan 2004).

Internet boom (but before the Internet bust),

when many Americans regarded the Internet as TEMPORAL SPECIFICITY OF CAUSAL MECHA-

a transformative force that would ignite explo- NISMS. Rewards to technological competence

sive economic growth. Internet use had spread are likely to change systematically over the life-

widely in the population (our analyses of CPS cycle of a technological innovation. Our data

data indicate that approximately seven in ten were collected at the end of a period of very

employed American adults used the Internet at rapid diffusion, just as the rate of increase was

some location in 2001), but the technology was beginning to decline. Figure 1 describes the

not so common in the workplace that it could change between 1997 and 2003 in the percent-

be taken for granted (just 45 percent used it at age of all non-institutionalized Americans age

work). Some of the Internet’s prestige may have 18 or older who reported using the Internet at

Figure 1. Internet Use, 1997 to 2003

Source: Current Population Survey Internet and Computer Use Supplements, 1997, 2000, 2001, and 2003.

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

234—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

any location and the percentage of employed For all of the reasons described above, we

Americans who reported using the Internet at anticipate the following:

work. Penetration in the U.S. population grew Hypothesis 1: The net earnings of Internet users

slowly through 1997 (not shown), then took rose faster in the period under observation

off, rising from 20 percent in 1997 to 52 percent than the earnings of workers who did not

in 2001. Internet use in the workplace, by con- use the Internet.

trast, grew slowly until 2000, jumped sharply

from 23 to 38 percent between 2000 and 2001, Not all forms of Internet use will have equally

and then leveled off. strong effects. We anticipate that the net earn-

The effects of competence in a new technol- ings of workers who used the Internet in 2000

ogy should initially increase as firms make the and 2001 rose faster than workers who report-

capital investments necessary to exploit such ed using it in only one of those years. Based on

competence. The effects should then decline as research on growth in the efficacy of use over

relevant skills saturate the workforce. Even if the time, we predict the following:

ability to find information effectively or to Hypothesis 2: The net earnings of workers who

engage in transactions online enhances worker used the Internet in 2001 but not 2000 grew

productivity, such skill will no longer give a faster than the earnings of nonusers but

worker a competitive edge once everyone has it less quickly than the earnings of more expe-

(Aghion and Howitt 2002). The same is true of rienced Internet users.

the competitive aspect of the social-capital

mechanism (although a general improvement in Workers who stopped using the Internet between

worker-job matches through more effective 2000 and 2001 may have benefited from sig-

information diffusion could lead to higher wages naling effects and social-capital effects. As cur-

overall). Similarly, the efficacy of Internet use rent nonusers, though, they lack the

for signaling is also likely to have been time-lim- human-capital advantage derived from using

ited. By 2002, the Internet boom had turned new technology at work. We therefore expect the

into a bust, and Internet use became common following:

even among moderately educated workers. Hypothesis 3: The net earnings of workers who

Being conversant with the latest technology used the Internet in 2000 but not in 2001

may always serve as a form of cultural capital grew faster than the earnings of nonusers

in some work settings, but particular technolo- but less quickly than the earnings of per-

gies may move in and out of fashion relatively sistent Internet users.

quickly. Consequently, the analyses that follow

Insofar as social-capital and cultural-capital

reflect the way that labor markets operated in

mechanisms operate to link technology use to

2000 and 2001; results should not be general-

higher earnings, we would expect to see bene-

ized to later periods.

fits for workers who used the Internet at home,

as well as for those who used it at work. Using

HYPOTHESES the Internet both at home and at work is likely

The three mechanisms described above do not to be especially advantageous. Use at work nets

map neatly onto specific indicators of Internet human-capital benefits; use on one’s own may

use. Nonetheless, we can use information about be more influential for signaling. Workers have

the impact of different indicators to derive more freedom to peruse job postings and to

insights into the relative importance of each. If expand networks through casual interaction at

Internet use raises income by boosting produc- home. And skills in searching and other activ-

tivity, only workers who use the Internet on the ities are likely honed through technology use at

job will benefit. By contrast, insofar as the home as well as at work. These points lead us

Internet operates through social-capital to our final hypothesis:

enhancement or signaling, using the Internet at Hypothesis 4: Net earnings of workers who

home may independently affect earnings. used the Internet only at home or only at

Indeed, workers who are no longer online could work grew faster than the earnings of

derive such benefits from past Internet use. nonusers but less quickly than earnings of

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–235

workers who used the Internet at both work Although the CPS’s panel structure makes it

and home. uniquely appropriate, it is not perfect. The major

limitation is that it cannot be used to estimate

the relationship between Internet use, job

DATA change, and earnings.4 Nor does it include data

We rely on data from the Current Population

Survey (CPS), a monthly household survey

third were in their 16th month (or had their eighth

fielded continually by the Bureau of the Census

interview) in September 2001. Hence, we were forced

and based on stratified probability samples of to rely on earnings data collected in the months

the non-institutionalized U.S. population. Each immediately following the Internet supplements. In

household in the CPS is interviewed in two 2000, all of our income data were collected after the

sequences of four consecutive months, sepa- August information technology module, in

rated by an eight-month hiatus, for a total of September, October, and November; in 2001, two-

eight interviews over 16 months. Every month, thirds were collected after the administration of the

one-eighth of the sample is replaced by new September 2001 information technology module, in

households with similar characteristics. This October and November. This feature of the CPS data

rotating sampling design permits comparisons requires us to assume that respondents’ typical week-

of households across time, as three-quarters of ly income would have been the same in the month of

respondents are the same in any two consecu- the Internet supplement as it was a month or two later.

Chow tests on coefficients from separate analyses of

tive months and half of the respondents are the

earnings data collected in September, October, and

same after 12 months. This design feature, com-

November gave us confidence in this assumption.

bined with the large sample size, makes the Coefficients for dummy variables representing (a)

CPS uniquely useful for our purposes. Internet use in both 2000 and 2001 and (b) Internet

In addition to core employment and demo- use in 2001 but not 2000 were virtually identical

graphic modules, the CPS periodically includ- across pairs of months. Coefficients for a dummy

ed special supplements on information and variable representing the relatively few respondents

communications technology. We take advan- who reported using the Internet in 2000 but not in

tage of the fact that the CPS included such sup- 2001 were different (the hypotheses that the effects

plements in August, 2000 and September, 2001. for the September and November samples were the

Data on technology use were collected between same as for the October sample were rejected with

August 13 and August 19, 2000 and again probabilities of p = .028 and p = .030, respectively)

between September 16 and September 22, 2001. but non-monotonically so, with effects on income

positive and significant for the September and

The 2000 wave comprised 47,673 households

November samples but negative and non-significant

and 121,745 individual responses, while the

for the October sample. Based on these analyses, we

2001 wave comprised 56,634 households and believe that using income measured in October and

143,300 individual responses. Of the house- November 2001 as a proxy for September income

holds in 2001, we found that 15,758 had also may have slightly diluted the effects of Internet use

participated in the 2000 supplement, yielding for those respondents who used the Internet in 2000

37,288 individual records. After excluding non- but not in 2001, but it did not materially affect the

civilians, respondents under age 18 and over 65, conclusions of this study.

4 During the period spanned by our panel, the CPS

those outside the labor force, respondents who

reported variable hours worked, and those who only collected detailed job change information in its

earned less than half of the federal minimum February 2000 Job Tenure and Occupational Mobility

wage, 9,446 individual cases remained.3 Supplement. Because our data span August to

November 2000 and September to November 2001,

and because the job change question refers to the pre-

vious year, it is impossible to know if the change

3 Individual earnings data in the CPS are collect- occurred before or after the collection of our first-

ed only from outgoing rotation groups (households period data. The basic CPS survey that accompanies

completing their fourth or eighth interview), which the Internet use supplements does gather information

constitute one-fourth of the respondents in any given about the respondents’ movements into and out of

month. None of the respondents who took part in both broad occupation and industry categories, but these

waves of the Internet supplement were in the fourth items fail to capture the majority of job changes that

month of their rotations in August 2000, and only one- occur within occupations and industries.

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

236—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

on employers. The CPS also suffers from exces- our sample.5 (Because the analysis is restricted

sive use of imputation and proxy respondents, to employed persons ages 18 to 65, usage rates

but our ability to control for the effects (see the are higher than for the population at large.)

Appendix) of these features renders these prob-

lems manageable.

Table 1 reports rates of Internet use in 2001 5 Respondents were asked, “Does anyone in this

by sociodemographic categories for persons in household use the Internet from home?” (2000) or

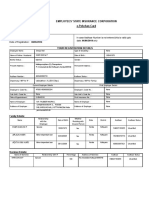

Table 1. Group-Specific Rates of Internet Use in 2001 (unweighted counts)

Work and Work or

Anywhere Work Home Home Home

N (percent) (percent) (percent) (percent) (percent)

Gender

—Male 4,793 66.7 41.1 55.6 31.6 65.1

—Female 4,653 73.7 48.2 57.5 33.5 72.2

Race/Ethnicity

—White 8,168 72.3 46.1 59.0 34.2 70.8

—Black 836 52.9 32.2 35.9 17.3 50.7

—Asian 342 67.5 44.7 56.4 34.5 66.7

—American Indian, Aleut, or Eskimo 100 48.0 26.0 33.0 14.0 45.0

—Hispanic 772 41.3 24.7 31.9 16.6 40.0

Age

—18 to 25 830 72.2 27.4 58.8 19.8 66.4

—26 to 35 1,953 73.8 47.4 59.4 34.8 71.9

—36 to 45 2,991 71.4 46.8 58.5 35.1 70.2

—46 to 55 2,628 70.4 47.6 56.4 34.4 69.6

—56 to 65 1,044 57.7 39.2 44.4 26.3 57.2

Education

—Less than high school 693 23.8 7.5 18.2 3.6 22.1

—High school 4,752 62.8 32.1 49.4 20.7 60.8

—Associate 1,037 76.0 45.6 60.6 31.9 74.3

—College 1,960 89.7 70.8 74.0 55.8 88.9

—Advanced 1,004 92.9 77.1 78.8 63.6 92.3

Region

—Northeast 2,092 72.9 44.0 60.3 32.6 71.7

—Midwest 2,601 72.7 45.8 58.4 33.6 70.6

—South 2,686 65.8 42.9 51.9 30.5 64.3

—West 2,067 70.0 46.0 56.4 33.8 68.6

Metropolitan Status

—Metropolitan 7,336 72.1 46.6 58.8 34.7 70.7

—Non-metropolitan 2,077 63.6 37.7 48.8 25.0 61.4

—Not identified 33 60.6 30.3 48.5 24.2 54.6

Industry

—Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mining 170 52.4 23.5 44.7 17.1 51.2

—Construction 581 50.3 19.3 43.6 14.1 48.7

—Manufacturing–durable 935 64.5 43.2 51.3 31.4 63.1

—Manufacturing–nondurable 589 61.1 39.7 50.4 30.6 59.6

—Transportation 413 60.3 25.2 49.6 17.7 57.1

—Communications 160 86.9 68.1 65.0 46.9 86.3

—Utilities and sanitary services 149 69.1 49.7 59.1 39.6 69.1

—Wholesale trade 397 67.5 45.1 52.6 31.7 66.0

—Retail trade 1,225 61.2 24.8 51.7 17.3 59.2

—Finance, insurance, and real estate 655 83.4 65.3 63.5 46.0 82.9

—Business, auto, and repair services 501 73.7 51.7 59.3 39.7 71.3

— (continued on the next page)

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–237

Table 1. (continued)

Work and Work or

Anywhere Work Home Home Home

N (percent) (percent) (percent) (percent) (percent)

Personal services 218 54.1 21.6 45.0 13.8 52.8

—Entertainment and recreation services 116 69.8 33.6 61.2 27.6 67.2

—Hospitals 525 75.2 45.3 60.8 31.8 74.3

—Medical services (excluding hospitals) 471 65.6 30.8 52.9 21.0 62.6

—Educational services 1,109 84.8 63.8 69.3 49.8 83.4

—Social services 203 69.0 38.9 49.8 23.2 65.5

—Other professional services 437 89.9 75.1 72.3 57.9 89.5

—Public administration 592 81.6 64.2 61.0 44.3 80.9

Occupation

—Executive, administrative, and managerial 1,487 88.4 73.7 70.8 56.6 88.0

—Professional specialty 1,775 89.1 69.8 74.1 55.7 88.2

—Technicians and related support 391 82.9 55.5 65.5 39.6 81.3

—Sales 879 72.4 43.1 59.4 31.2 71.3

—Administrative support (including clerical) 1,529 79.1 53.2 58.2 33.6 77.8

—Service 991 48.3 13.4 40.2 8.7 44.9

—Precision production 1,069 52.5 20.3 44.1 13.8 50.5

—Mach. operat., assemb., and inspect. 483 38.7 11.8 32.3 7.5 36.7

—Transportation and material moving 405 40.3 5.4 34.6 2.2 37.8

—Farming, forestry, and fishing 111 30.6 9.9 26.1 7.2 28.8

—Handlers, equip. cleaners, laborers 326 42.0 8.3 34.4 4.0 38.7

Total 9,446 70.2 44.6 56.6 32.5 68.6

Source: Current Population Survey Internet and Computer Use Supplement 2000 and 2001, employed persons,

ages 18 to 65.

More than two-thirds (70 percent) of the respon- Islanders (68 percent), African Americans (53

dents reported using the Internet in 2001, up percent), and American Indians, Aleuts, or

from 61 percent in 2000. Usage varied by race, Eskimos (48 percent). Hispanics reported a

with whites reporting the highest rates (72 per- lower rate than non-Hispanics, 41 and 73 per-

cent respectively. Respondents between ages

cent), followed by Asian Americans or Pacific

26 and 35 reported the highest usage of any

age cohort (74 percent); those between ages 56

and 65 used the Internet the least (58 percent).

“Does anyone in this household connect to the

Women were more likely than men to use the

Internet from home?” (2001). In 2000, they (or the

Internet (74 percent compared to 67 percent), an

person who answered on their behalf) were then

asked a series of questions about how they used the advantage among working Americans that con-

Internet at home and whether they used the Internet trasts with CPS figures for the entire adult pub-

at work or at another location. Persons were coded lic (55 percent for both women and men). The

as using the Internet in 2000 if they reported any use difference reflects women’s advantage in at-

at home (in response to a list that ended with use for work Internet use (48 versus 41 percent) and

“any other purpose”), at work, or at another location suggests that increased workplace technology

outside the home. In 2001, the survey asked point use was responsible for eliminating a gender gap

blank about use of any kind at home as well as use that gave men an advantage during the Internet’s

at work or another location outside the home. Again, early years (Ono and Zavodny 2003).

persons who used the Internet at any of these loca-

Consistent with previous research, educa-

tions were coded as using the Internet. Respondents

tional attainment was strongly and positively

who reported (or were reported as) using the Internet

at home for any of the options (including “any other”) associated with Internet use, with rates ranging

in 2000, or who reported (or were reported as) using from 24 percent for workers who had not fin-

the Internet at home in 2001, were coded as home ished high school to 93 percent for those with

users. Those who reported using the Internet at work advanced degrees. Usage rates were lowest in

were coded as workplace users. the South (66 percent) and highest in the

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

238—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Midwest and the Northeast (73 percent). ple); adopters, those who did not use the Internet

Workers who lived in Metropolitan Statistical in 2000 but did in 2001 (N–Y [for No–Yes]; 16

Areas (MSAs) were online more than non- percent of respondents); and disadopters, users

metropolitan residents (72 versus 64 percent). in 2000 who were nonusers in 2001 (Y–N [for

Internet use rates varied notably by industry, Yes–No]; 7 percent of respondents). (Consistent

ranging from just 50 percent in the construction with other studies, but contrary to popular belief,

trades to 90 percent in “other professional serv- the Internet user population is characterized by

ices.” (Not surprisingly, rates for agricultural and considerable flux [Katz and Aspden 1997;

personal-service workers were near the bottom, Lenhart et al. 2003]. The proportion of dis-

whereas rates in the communications and edu- adopters in our sample of employed persons is

cation industries were close to the top.) Variation lower than that for the CPS as a whole.) The

was even greater among occupations, with just omitted category includes respondents who

31 percent of laborers in extractive industries reported using the Internet in neither year (23

going online, compared to 89 percent of pro- percent). Because all models control for lagged

fessionals. (2000) income, coefficients indicate effects on

Finally, 81 percent of Internet users (57 per- net wages over a period of approximately 13

cent of all respondents in the labor force) used months.7

the Internet at home, 64 percent (45 percent of Positive effects of Internet use on earnings are

all respondents) used it at work, and 46 percent significant and robust to the inclusion of a wide

(33 percent of all respondents) used it at home range of controls. Model 1 includes the Internet

and at work. Over 98 percent of users were use measures and lagged wages.8 The effects of

connected at home or work; the rest went online all kinds of Internet use are highly significant,

at a library, community center, school, or friend’s but the coefficient for respondents who used the

or relative’s home. Internet in both periods exceeds those for recent

adopters or disadopters. Model 2 adds controls

for race and Hispanic ethnicity, gender, age

RESULTS (and age squared), marital status, educational

We first present OLS regression models in attainment, region of residence, and metropol-

which the dependent variable is logged hourly itan residence, reducing the impact of continu-

earnings in 2001.6 We compare change in wages al use by 41 percent and the advantage of both

of Internet nonusers to continuous Internet adopters and disadopters by about 27 percent.

users, adopters, and disadopters. Then we com- Adding controls for industry and occupation

pare nonusers to workers who used the Internet (Model 3) reduces the effect for continual users

only at work, only at home, and at home and by another 25 percent, for adopters by 22 per-

work. After reporting results of several robust- cent, and for disadopters by 27 percent.9

ness tests, we distinguish the impact of Internet

use from that of using stand-alone computers. 7 Coefficients for controls are reported in Table S2

of the Online Supplement on the ASR Web site:

DOES INTERNET USE SIGNIFICANTLY http://www2.asanet.org/journals/asr/2008/toc062.

PREDICT EARNINGS IN 2001 (NET OF 2000 html. For a list of control variables used in each

EARNINGS)? model, see the note for Table 2.

8 All models also include controls for dichoto-

Internet use is measured at any location in 2000 mous variables indicating (a) whether data on hours

and 2001. Separate dummies represent respon- or earnings were imputed in either wave and (b)

dents who used the Internet in both years (Y–Y whether the case includes a proxy flag indicating

[for Yes–Yes] in Table 2; 55 percent of the sam- that another household member answered on behalf

of the respondent, as well as a multiplicative term for

imputation*earnings (to correct for underestimation

of the lagged earning effect and for the possibility that

6 Earnings were reported for the primary job. control variables might be overestimated). See the

Hourly employees could report hourly earnings. Appendix for a thorough discussion.

Others reported hours worked in a typical week and 9 Both industry and occupation categories include

typical weekly earnings. The latter was divided by the numerous job titles that are heterogeneous with

former to yield an hourly wage. respect to the skill required of incumbents. If Internet

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–239

Table 2. Regression of Logged Wages in 2001 on Internet Use at Any Location

N Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Internet 2000 to 2001: Y– Ya 5,156 .148*** .087*** .065*** .061***

(.011) (.011) (.012) (.015)

.132 .078 .058 .055

Internet 2000 to 2001: N–Y 1,471 .070*** .051*** .040** .036*

(.014) (.013) (.013) (.017)

.046 .033 .026 .024

Internet 2000 to 2001: Y–N 625 .086*** .063*** .046** .046**

(.018) (.018) (.017) (.017)

.039 .028 .021 .020

Computer use 2001: networked and non-networked 7,331 .005

(.015)

.004

Intercept .419*** .189*** .436*** .435***

(.028) (.056) (.059) (.059)

N 9,446 9,446 9,446 9,446

Adjusted R2 .486 .529 .555 .555

Source: Current Population Survey Internet and Computer Use Supplement 2000 and 2001.

Notes: Income and hours worked were obtained from Basic CPS data collected in September, October, and

November, 2000 and 2001. The analysis excludes non-civilians, respondents under age 18 and over 65, people out

of the labor force, those with varying weekly work hours, and those who earned less than half of the federal

minimum wage in 2000 or 2001. Control variables are omitted in the interest of parsimonious presentation.

Model 1 controls include earnings in 2000 (logged), proxy and imputed response dummies, and an earnings by

imputation interaction. Model 2 controls include those from Model 1, plus union membership, gender, race and

ethnicity, age, education, marital status, metropolitan status, and region. Models 3 and 4 controls include those

from Model 2 plus industry and occupation. Coefficients are followed by standard errors in parentheses and beta

weights in italics. Y–Y refers to respondents who used the Internet at any location in both 2000 and 2001. N–Y

refers to those who used it in 2001 but not in 2000 (adopters). Y–N refers to respondents who used the Internet in

2000 but not in 2001 (disadopters).

a Internet and computer use variables measure use anywhere (home, work, or other locations).

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 (one-tailed tests for Internet use coefficients, two-tailed tests for all other

variables).

use is highly correlated with job skill requirements, The remaining net earnings advantage of

and if these requirements are associated with changes continuous users is statistically significant at

in wages, then omitting them from the model may p < .001 (one-tailed), consistent with Hypothesis

lead us to overestimate the impact of Internet use on 1. Adopters’ and disadopters’ advantages are

net wages. We therefore ran an additional model (not significant at p < .01. In dollar terms (based on

reported here but available on request) in which occu- coefficients in Model 3), the median earner

pation dummies were replaced by a novel set of occu-

who used the Internet in both years was paid

pational skill ratings: skill in managing interpersonal

relations, exerting physical strength, obtaining infor- $.96 per hour more than a comparable nonuser.

mation, working independently, having a strong The wage premium for a median earner who

achievement orientation, being socially perceptive, adopted Internet use in 2001 was $.58; and

analyzing data, and updating and using relevant median earners who stopped using the Internet

knowledge. Skill ratings were obtained from the between waves received a premium of $.67.

Occupational Information Network (O*NET), suc- Consistent with Hypothesis 2, Wald tests for dif-

cessor to the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, and ference in coefficients (available on request)

made applicable to the CPS occupation codes by a

indicate that continuous users gained signifi-

multistep crosswalk developed by the second author

(details available on request). Replacing categorical cantly more than 2001 adopters (p < .05). In

measures of occupation with these new measures these analyses, however, Hypothesis 3 is dis-

left coefficients for Internet use indicators virtually confirmed, as effects for continuous users and

unchanged. disadopters are not significantly different. As

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

240—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

noted below, robustness tests suggest that the Results appear in Table 3. Separate dichoto-

disadopter coefficient is inflated. mous variables identify respondents who used

We draw three tentative lessons from these the Internet at home and work in at least one

results: year (37 percent of all workers), respondents

1. Internet users gained significantly more in earn-

who used the Internet only at home (26 percent),

ings than nonusers. These gains persisted despite and those who used the Internet only at work (13

the inclusion of numerous control variables. They percent). Nonusers (23 percent) are the omitted

were also independent of the effects of unmea- category. For the sake of parsimony, the few

sured characteristics of worker and job, the effects respondents who used the Internet only at a

of which were incorporated in logged earnings as location other than home or work are omitted.

measured in the fall of 2000. The models control for lagged income, so coef-

2. The advantage of workers who used the Internet ficients indicate influence of Internet use on

in both years over recent adopters indicates that net wages over a period of approximately 13

experience and accumulated skill mattered. months.

3. The fact that disadopters continued to do better All groups of users earned significantly more

than workers who never used the Internet may be

(net earnings in 2000 and other controls) than

attributable to some combination of cultural-cap-

ital effects, job skills or information acquired

nonusers in 2001 (Model 1). Those who used the

before disadoption, and unmeasured correlates Internet at home and work gained the highest

of disadopter status that influenced the slope of returns, followed by those who used the Internet

earnings between August 2000 and September at work but not at home, and those who used it

2001. at home but not at work. Controlling for race and

Hispanic ethnicity, gender, age (and age

If social-capital/information-hoarding and cul- squared), marital status, educational attainment,

tural-capital/signaling mechanisms provide an region of residence, and metropolitan residence

income advantage to Internet users, then work- (Model 2) reduces the coefficient for Internet

ers who use the Internet at home but not at use at home and work by 37 percent. The effect

work should also do better than workers who do of home-only use declines by 42 percent, and

not use the Internet at all. It is also important to that of work-only use by 25 percent. Introducing

assess the effects of Internet use at home controls for industry and occupation (Model 3)

because home use is far less likely to be influ- further reduces the home and work effect by 24

enced by employer decisions than is Internet use percent, the work-only coefficient by 30 percent,

at work. We explore this possibility in the next and the home-only effect by just 5 percent. All

section. remain positive and statistically significant.

Consistent with Hypothesis 4, all user groups

DID INTERNET USE AT HOME increased earnings significantly more than did

INDEPENDENTLY BOOST EARNINGS? nonusers. Also consistent, Wald tests indicate

that returns to workers who used the Internet at

If the effects of Internet use reflect only unmea- home and at work were significantly greater

sured differences that influence the rate of earn- than for those who used the Internet only at

ings growth between Internet users and other work (p < .01) or only at home ( p < .001).

workers, or if they reflect a cultural-capital or Wage premiums (relative nonusers) amounted

signaling effect rather than enhanced produc- to $1.40 per hour for median earners who used

tivity, we would expect workers who used the the Internet at home and work, $.88 for those

Internet only at home to boost their net wages who used it at work but not at home, and $.52

as much as those who used the Internet on the for home-only users.

job. This was not the case. We ran an additional model with the same

If the association between Internet use and covariates as in Model 3, but with 15 detailed

earnings reflects only a tendency for wealthy categorical measures indexing Internet use or

firms to implement new technologies first and nonuse at home and work by year, with nonusers

to pay high wages to their employees, then omitted. Although Ns for many categories are

workplace Internet use would make all the dif- quite small, the overall pattern of results (avail-

ference and Internet use at home would have lit- able on request) reinforces those in Model 3.

tle effect on wages. This, too, was not the case. Workers who used the Internet at home and

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–241

Table 3. Regression of Logged Wages in 2001 on Internet Use at Home and Work

N Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Internet: home and work (2000 or 2001)a 3,486 .198*** .124*** .094*** .094***

(.011) (.012) (.013) (.016)

.172 .108 .082 .082

Internet: home only (2000 or 2001) 2,414 .066*** .038** .036** .036**

(.012) (.012) (.011) (.014)

.052 .030 .028 .028

Internet: work only (2000 or 2001) 1,186 .115*** .086*** .060*** .060***

(.014) (.014) (.015) (.017)

.069 .051 .036 .036

Computer use 2001: networked and non-networkedb 7,331 .000

(.014)

.000

Intercept .477*** .252*** .463*** .463***

(.028) (.056) (.058) (.059)

N 9,446 9,446 9,446 9,446

Adjusted R2 .493 .532 .556 .556

Source: Current Population Survey Internet and Computer Use Supplement 2000 and 2001.

Notes: Income and hours worked were obtained from Basic CPS data collected in September, October, and

November, 2000 and 2001. The analysis excludes non-civilians, respondents under age 18 and over 65, people out

of the labor force, those with varying weekly work hours, and those who earned less than half of the federal

minimum wage in 2000 or 2001. Control variables are omitted in the interest of parsimonious presentation.

Model 1 controls include 2000 earnings (logged), proxy and imputed response dummies, and an earnings x

imputation interaction. Model 2 controls include those from Model 1, plus union membership, gender, race and

ethnicity, age, education, marital status, metropolitan status, and region. Models 3 and 4 controls include those

from Model 2 plus industry and occupation. Coefficients are followed by standard errors in parentheses and beta

weights in italics.

a “Internet: home and work (2000 or 2001)” refers to respondents who used the Internet both at home and at work

in at least one of the two waves of the survey. “Internet: home only (2000 or 2001)” refers to respondents who

used the Internet at home but not at work in at least one of the two waves (and did not use the Internet at work in

the other wave). “Internet: work only (2000 or 2001)” refers to respondents who used the Internet at work but not

at home in at least one of the two waves (and did not use the Internet at home in the other wave). Respondents

who used the Internet at home in one wave and at work in the other were classified based on their Internet usage

in 2001.

b The computer use variable measures use anywhere (home, work, or other locations).

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 (one-tailed tests for Internet use coefficients, two-tailed tests for all other

variables).

work in both 2000 and 2001 (unstandardized location between 2000 and 2001, did better than

coefficient of .116), at home in 2000 and home those who used it at work alone.

and work in 2001 (.110), and at work in 2000

and home and work in 2001 (.112) gained the ARE THESE RESULTS ROBUST TO

most. The only groups whose earnings did not DIFFERENT SPECIFICATIONS?

increase significantly more than nonusers were

those who used the Internet only at work and In this section, we summarize the results of

only in 2000 (likely due to unmeasured job efforts both to correct for CPS’s use of imputa-

change); those who used the Internet only at tion and proxy responses and to employ change-

home and only in 2001 (whose skills were poor- score and propensity-score–matching models to

ly developed and for whom any signaling value address issues of endogeneity and selectivity. A

was belated); and those who used the Internet more detailed account appears in the Appendix.

at both locations in 2000 but at neither in 2001. 1. The effects of persistent Internet use and of

Overall, respondents who used the Internet at Internet use at home and work remain positive and

home and work, including those who added a highly significant in every specification. Bias

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

242—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

from selection on unobserved factors, which the DID INTERNET USE HAVE AN IMPACT OVER

change-score analysis suggests may inflate coef- AND ABOVE THAT OF COMPUTER USE

ficients, and bias introduced by CPS’s use of

ALONE?

proxy responses, which lead to underestimates of

Internet-use coefficients (except for disadopter Most computer users also use the Internet.

status), run in opposite directions. Propensity- Might the impact of Internet use represent no

score matching indicates that selection on more than the familiar effects of computer use

observed variables is not a problem.

on earnings (Krueger 1993)? In 2001, 72 per-

2. The effects of home-only use remain significant

in all specifications (though the significance level cent of workers who used a computer at work

declines in the proxy and change-score specifi- used the Internet there as well (Hipple and

cations), reinforcing our confidence that home Kosanovich 2003). Of the computer users in

Internet use boosted earnings even for respondents our sample, 89 percent also used the Internet.

who did not use the Internet at work. Benefits to (The figure is higher because it includes com-

adopters are reduced, especially in the change- puter and Internet use at any location.)

score model, but they also remain significant. Compared to Internet users, computer users

Work-only users’ earnings gains are strongly sig- who did not use the Internet were more likely

nificant in every specification but the change-

to be women, non-white and non-Asian, less

score model. Given reasons to question the

specification of that model (see the Appendix), we educated, somewhat older, and employed in

are disinclined to reject the hypothesis that work- blue-collar or retail occupations (table avail-

only use matters on that basis alone. able from the authors on request).

3. Earnings differences between disadopters and The effects of computer and Internet use are

nonusers are insignificant in the proxy specifi- diff icult to disentangle. Bresnahan,

cation and only marginally significant in the Brynjolfsson, and Hitt (2002) argue that, by

change-score model. Positive returns for dis- the late 1990s, the reported effects on labor

adopters thus appear to be artifacts of the CPS’s markets of computers were largely effects of net-

use of proxy respondents and perhaps of selection

worked computing rather than stand-alone com-

bias.

puters. Kim’s (2003) cross-sectional analysis

To summarize the findings: Internet users of 1997 CPS data reports a positive impact of

earned more than nonusers, especially if they Internet use on hourly wages even after con-

used the Internet in both years. The labor mar- trolling for computer use on the job. Also using

ket rewarded Internet use at home and at work, cross-sectional data, Bertschek and Spitz (2003)

and workers who went online at home and work report stronger effects of Internet use than of

did best of all. These results are inconsistent with more routine forms of IT use (including PCs)

the view that Internet effects are artifactual on earnings in a West German sample.11

because they reflect the characteristics of firms Consistent with these findings and argu-

rather than workers (in which case additive ments, we hypothesize that Internet and intranet

effects of home use would be weak or nonex- use add to workers’ earning power independent

istent). They are also inconsistent with the view of using computers for spreadsheet manage-

that Internet use boosts wages entirely through ment, word processing, or other conventional

its effect on technology-use–driven workplace office activities. To address this issue, we added

productivity gains (in which case use at home, dummy variables for computer use at any loca-

but not at work, would have no effect). The tion in 2001 to Model 3 of Tables 2 and 3.

effects appear to be real, but the mechanisms

that connect technology use to earnings are

more numerous and complex than standard words, home users have higher net earnings because

human-capital theories would predict.10 their technological skills enable them to insist on a

higher reservation wage. This explanation is plausi-

ble, but preferring it to the social-capital or signal-

ing accounts requires a commitment to neoclassical

10 One can salvage the human-capital explanation theory that we do not share.

for home users by arguing that they only take jobs that 11 They also reported stronger effects, with appro-

do not permit them to benefit directly from their priate controls, of using a laptop on the job. We sus-

Internet skills if those jobs provide especially high pect that being trusted with a laptop is a proxy for

returns to some other skill they possess. In other employee autonomy and employer confidence.

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

MAKE MONEY SURFING THE WEB?—–243

Results appear in Table 2, Model 4 (for year-of- mechanisms. Some such mechanisms are plau-

use Internet measures) and Table 3, Model 4 (for sibly connected to productivity enhancement

home and work Internet-use measures). (e.g., if home users acquire information that

Controlling for computer use has only a slight makes them better workers); whereas others

effect on the statistically significant coefficients may enhance workers’ wages without neces-

of persistent Internet use, adoption, and dis- sarily benefiting employers (e.g., by giving

adoption, and no effect on the coefficients for workers superior information about available

Internet use at home, work, and home and work. jobs or providing noisy signals for characteris-

In both models the coefficient for computer tics that employers value). Taking our results as

use itself is tiny and insignificant. These results a whole, we suspect that human-capital/

suggest that the effect of Internet use on earn- productivity-enhancement is probably the most

ings is independent of computer use and that, important, but not the only, mechanism through

as computer use has become ubiquitous, net- which technology affects earnings. Had we

worked computing has succeeded stand-alone taken the human-capital model for granted and

functions as the basis of computer users’ earn- measured Internet use only in the workplace

ings advantage. (using the covariates in Model 3), we would

have underestimated the impact of Internet use

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS on wages, reporting a single unstandardized

coefficient of .033 (for workplace use in 2000)

Between 2000 and 2001, U.S. workers who used or .064 (for workplace use in 2001) and miss-

the Internet increased their earnings at a faster ing the value added by home Internet use and

rate than their offline counterparts. These ben- by persistent, as opposed to short-term, use at

efits were independent of computer use, which work.

enhanced earnings only when computers were This study also leaves several questions un-

connected to networks that enabled users to go resolved:

online. Web users’ earnings were higher than

those of nonusers, even controlling for earnings 1. Identifying more clearly the relative roles of dif-

ferent mechanisms in linking technology use to

a year earlier, and with controls for age, gender,

earnings is a high priority. Better data on jobs,

race, ethnic background, educational attain- employers, and career histories could make this

ment, marital status, region and metropolitan possible. For example, human-capital returns to

residence, union membership, occupational cat- Internet use should be a function of experience

egory, occupation-level job skill demands, and with technology, the non-routineness of online

industry. Results indicating an advantage for tasks, and the potential payoff to employers of

workers who used the Internet in both years excellent performance (and the potential cost of

and for those who used the Internet at work mistakes). Benefits from enhanced information

and at home are robustly significant across a about the job market should be most visible

wide range of model specifications. Workers among recent job changers and in occupations in

which employers compete to attract and retain

who used the Internet only at home and not at

workers. Signaling effects should be most impor-

work were also rewarded, indicating that not tant in industries that are youth-oriented and value

all of the effect on earnings reflects either direct employees who are au courant; and for occupa-

enhancements to workplace productivity or the tions in which performance is difficult to meas-

results of employer investments. Workers who ure. Given adequate data, one could specify a

used the Internet only at work, or who began combination of interactions that could yield more

going online between 2000 and 2001, also detailed conclusions about the relative role of

earned more, though the effects are smaller and these mechanisms. More detailed data on what

less robust. workers actually do online at work and at home

These results indicate the value of looking would also provide greater purchase on this issue,

especially combined with better data on jobs,

beyond workplace Internet use and suggest that

making it possible to identify more precisely the

human-capital/productivity enhancement may skills that the labor market rewards. Case studies

not be the only mechanism responsible for of particular workplaces (see Fernandez 2001 for

Internet users’ earnings advantage. The earnings an excellent example) and interviews with human

gains for workers who used the technology at resources administrators could also be useful in

home but not at work may result from several this regard.

Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on February 10, 2015

244—–AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

2. These analyses are restricted to men and women Do the findings in this article demonstrate that,

already in the labor market. As job listings migrate to quote those infamous spam e-mails and

online, mastery of Internet technology may online ads, one can “make money surfing the

become increasingly important for getting a job Web”? Not necessarily. These results must be

in the first place. The impact of Internet use on understood in historical context. Two features of

job acquisition is an especially important priori- the period in which the data were collected—

ty for students of poverty.

the lingering cultural cachet of the Internet and