Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

This Content Downloaded From 103.244.172.219 On Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

Hochgeladen von

Ahsan IqbalOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This Content Downloaded From 103.244.172.219 On Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

Hochgeladen von

Ahsan IqbalCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

On the Dangers of Pulling a Fast One: Advertisement Disclaimer Speed, Brand Trust, and

Purchase Intention

Author(s): Kenneth C. Herbst, Eli J. Finkel, David Allan and Gráinne M. Fitzsimons

Source: Journal of Consumer Research , Vol. 38, No. 5 (February 2012), pp. 909-919

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/660854

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Journal of Consumer Research

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

On the Dangers of Pulling a Fast One:

Advertisement Disclaimer Speed, Brand

Trust, and Purchase Intention

KENNETH C. HERBST

ELI J. FINKEL

DAVID ALLAN

GRÁINNE M. FITZSIMONS

Two experiments demonstrated that fast (vs. normal-paced) end-of-advertisement

disclaimers undermine consumers’ purchase intention toward untrusted brands

(both trust-unknown and not-trusted brands), but that disclaimer speed has no

effect on consumers’ purchase intention toward trusted brands. The differential

effects of disclaimer speed for untrusted versus trusted brands were not due to

differences in consumers’ familiarity with the brands (experiment 1). Consistent

with the hypothesis that fast disclaimers adversely affect purchase intention via

heuristic rather than elaborative processes, the disclaimer speed # brand trust

interaction effect remained robust even when the disclaimer presented positive

information about the advertised product (experiment 2).

T o adhere to industry regulations or to protect against

possible lawsuits, advertisers frequently include end-

of-advertisement disclaimers in radio and television spots.

irrelevant features, including speed (http://business.ftc.gov/

documents/bus47-advertising-retail-electricity-and-natural-

gas, 2000; personal communication on FTC’s policy re-

Although regulatory agencies like the Federal Trade Com- garding disclosure speed regulation by Richard Quaresima,

mission (FTC) exert control over the content of these dis- FTC, April 20, 2011). The current research investigates the

claimers, they lack strict policies regarding many content- impact of disclaimer speed on consumers’ intention to pur-

chase the advertised product. We suggest that fast disclaim-

Kenneth C. Herbst is an assistant professor of marketing in the Schools ers can give consumers the impression that the advertisement

of Business at Wake Forest University, Worrell Professional Center, Wins- is trying to conceal information, “pulling a fast one” toward

ton-Salem, NC 27106 (herbstk@wfu.edu). Eli J. Finkel is an associate the goal of boosting purchase intention. We further suggest,

professor of psychology at Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 however, that trusted brands (vs. trust-unknown or not-

(finkel@northwestern.edu). David Allan is an associate professor of mar- trusted brands) are immune to these adverse effects of fast

keting in the Haub School of Business at Saint Joseph’s University, Phil- disclaimers.

adelphia, PA 19131 (dallan@sju.edu). Gráinne M. Fitzsimons is an associate Consumers, who must determine advertisers’ motives and

professor of management and psychology in the Fuqua School of Business at

intentions if they hope to make optimal spending decisions

Duke University, Durham, NC 27708 (grainne.fitzsimons@duke.edu). This re-

search was partially sponsored by the Wake Forest University Schools of

(e.g., Campbell 1995), often rely on their prior knowledge

Business Faculty Research Fund. The authors wish to thank Paul Eastwick, and experience with advertising tactics to determine whether

Steve Graham, Derek Rucker, Duane Wegener, and the MaSC Lab at Duke the advertised product is worth purchasing (Friestad and

University for their invaluable comments on a previous draft of this article; Wright 1994, 1995). Many people believe that advertisers

and the editor, the associate editor, and all three anonymous reviewers for use deceitful tactics to manipulate consumers (e.g., Darke

their extraordinary guidance throughout the review process. The first two and Ritchie 2007; Moog 1990; Packard 1991). We suggest

authors contributed equally to this article and should both be viewed as that fast disclaimers can represent one such tactic. In par-

“first author”; please direct correspondence to either of them. ticular, we propose that disclaimer speed serves as a heuristic

John Deighton served as editor and Susan Broniarczyk served as associate cue that consumers use to intuit whether they can believe

editor for this article. the claims presented in an advertisement. Because this cue

is only relevant when consumers aim to evaluate whether

Electronically published June 1, 2011

to trust the advertiser’s claims, it should only be influential

909

䉷 2011 by JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH, Inc. ● Vol. 38 ● February 2012

All rights reserved. 0093-5301/2012/3805-0010$10.00. DOI: 10.1086/660854

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

910 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

for brands that consumers do not already trust. We suggest can serve as a negative heuristic cue for the untrustworthi-

that consumers will use fast disclaimers as a heuristic cue ness of the advertiser.

of low trustworthiness when evaluating trust-unknown or The hypothesis that disclaimer speed may cue consumers

not-trusted brands but not when evaluating trusted brands. to distrust the advertiser’s intentions also has a strong link

to theorizing and research on the persuasion knowledge

model (Friestad and Wright 1994, 1995). According to this

ADVERTISEMENT DISCLAIMERS AND model, one of consumers’ primary tasks is to interpret and

SPEED OF COMMUNICATION cope with marketers’ persuasion attempts. To do so, they

develop knowledge structures about the motives of adver-

Our suggestion that disclaimer speed functions as a heuristic tisers and the tactics used in advertising, which help them

trust cue represents a new direction for research on dis- respond to advertising in a way that suits their own goals

claimers and on advertisement disclosures more generally. (Campbell and Kirmani 2000; Friestad and Wright 1994).

Past research on disclosures—end-of-advertisement infor- In particular, consumers use their prior experience and

mation about the safety or effectiveness of the product— knowledge of marketing tactics to make inferences about

has typically emphasized factors that influence their use- the manipulative intent, deceptiveness, and ulterior motives

fulness for protecting consumer interests (e.g., Andrews, of advertisers (Campbell 1995; Darke and Ritchie 2007;

Burton, and Netemeyer 2000; Andrews, Netemeyer, and Fein 1996). We suggest that consumers may believe that

Durvasula 1991; Mason, Scammon, and Fang 2007; Stewart fast disclaimers represent a tactic used by advertisers to hide

and Martin 2004). For example, previous benign experience information or to deceive consumers. Just as ingratiation

with a product and positive prior beliefs may reduce the and flattery tactics can serve as cues for the lack of trust-

effectiveness of disclosures (Rogers, Lamson, and Rousseau worthiness in salespersons (Campbell 1995; Main, Dahl, and

2000), as may frequent use of the product (Andrews et al. Darke 2007), we suggest that fast disclaimers can serve as

1991) and insufficient cognitive capacity to engage in cor- cues for the lack of trustworthiness in advertisements.

rection processes (Johar and Simmons 2000). In the present Our proposal that disclaimer speed can reduce trust via

research, rather than emphasizing the importance of disclo- heuristic processes, as opposed to processes requiring cog-

sure content, we emphasize the importance of disclaimer nitive elaboration, implies that the mere presence of the cue

speed—a content-irrelevant feature of disclosures. should influence consumers. Just as fast speech can serve

Although research has neglected the speed of disclaimers, as a heuristic cue for the intelligence of a speaker, affecting

several studies have examined the effects of speed of com- perception of the speaker without systematic processing of

munication in other persuasion attempts (Briñol and Petty the content of the speaker’s message (Miller et al. 1976;

2003; Miller at al. 1976; Moore, Hausknecht, and Thamo- Smith and Shaffer 1995), so too can fast disclaimers affect

daran 1986; Smith and Shaffer 1995). Much of this research perception of the advertised brand without systematic pro-

has used a dual-processing model of persuasion—the elab- cessing of the disclaimer’s content. If so, then the effect of

oration likelihood model (ELM; Petty and Cacioppo 1986; fast disclaimers on consumers’ purchase intention should

Petty and Wegener 1999)—as the theoretical starting point occur even if disclaimers reveal only positive information

for studying the effects of fast communication (Smith and about the advertised product.

Shaffer 1995). Such research has found that fast speech can This “content-independent” hypothesis allows us to test

limit people’s ability to process or elaborate on the message our proposed heuristic mechanism against another plausible

content; thus, its effect on persuasion depends on whether route through which fast disclaimers could reduce trust. If

such processing would have had positive or negative effects. participants see fast disclaimers as a cue for untrustworthi-

If elaboration would have yielded greater persuasion, as ness, then they may respond by closely scrutinizing the

when argument quality is strong, then fast speech hinders disclaimers (Priester and Petty 1995), elaborating upon and

persuasion (Smith and Shaffer 1991). If elaboration would processing them more systematically. If so, then they should

have yielded weaker persuasion, in contrast, then fast speech exhibit diminished purchase intention only when disclaimers

promotes persuasion. Indeed, fast radio advertisements de- are negative. According to this alternative mechanism, when

crease differentiation between strong and weak arguments disclaimers are positive, increased elaboration should, if

because consumers have trouble processing the content of anything, promote stronger purchase intention. We address

the message (Moore et al. 1986). this issue in experiment 2.

Fast speech can also act as a positive heuristic cue for

the credibility of the source, reflecting the belief that fast

speakers tend to be intelligent (Miller et al. 1976; Smith and

BRAND TRUST

Shaffer 1995). As Smith and Shaffer (1995) note, however, Integrating across various perspectives (Chaudhuri and Hol-

there is no reason to believe that intelligence is the only brook 2001; Doney and Cannon 1997; Erdem and Swait

characteristic conveyed by fast speech; listeners might also 2004; McAllister 1995; Moorman, Deshpandé, and Zaltman

infer that fast speakers are trying to deceive listeners by 1993; Moorman, Zaltman, and Deshpandé 1992; Morgan

speaking too quickly to allow for careful attention to the and Hunt 1994; Sirdeshmukh, Singh, and Sabol 2002), we

message content. In keeping with this insight, we suggest define brand trust as consumers’ confidence that the brand,

that, in the context of advertisement disclaimers, fast speech product, or service firm is dependable and competent. Trust

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DISCLAIMER SPEED 911

predicts perceptions of brand credibility (Erdem and Swait purchase intention is unaffected by ambiguous trust cues

2004) and brand loyalty and commitment (Chaudhuri and like speedy disclaimers when such cues come from trusted

Holbrook 2001; Garbarino and Johnson 1999; Morgan and brands, but that consumers’ purchase intention is under-

Hunt 1994; Sirdeshmukh et al. 2002), and it is an essential mined when such cues come from untrusted brands. The

element in building successful marketing relationships rationale for this prediction is that high levels of trust cause

(Morgan and Hunt 1994; Urban, Sultan, and Qualls 2000). consumers to have a high threshold for perceiving trust vi-

We draw on theorizing on interpersonal trust (Holmes and olations, and fast disclaimers fall below this threshold.

Rempel 1989; Simpson 2007) to examine how exposure to In summary, we suggest that consumers encountering an

heuristically processed trust-relevant information (dis- advertisement first ask themselves whether they already trust

claimer speed, in this case) differentially impacts consum- the advertised brand. If they do trust the brand, we suggest

ers’ purchase intention toward untrusted (either trust-un- that they will tend to lack the active goal of evaluating the

known or not-trusted) and trusted brands. When consumers trustworthiness of the claims and, consequently, will be in-

either lack trust-relevant information about or have low trust sensitive to trust cues. If they do not trust the brand (either

in the advertised brand, we suggest that they will exhibit because they lack trust-relevant information or because they

evaluation, showing sensitivity to heuristic trust cues. They have established low trust in the brand), we suggest that

are unsure or wary of the brand’s motives, and their purchase they will tend to possess the active goal of evaluating the

intention plummets if the brand exhibits ambiguously sus- trustworthiness of the claims and, consequently, will be sen-

picious tendencies. When consumers trust the advertised sitive to trust cues. Such consumers ask themselves whether

brand, in contrast, we suggest that they will exhibit faith, the cues indicate that the advertised brand is trustworthy. If

showing insensitivity to heuristic trust cues. They assume so, then they are more likely to purchase it. If not, then they

that the brand is acting with integrity, and their purchase are less likely to purchase it. (Although consumers may

intention is not affected by ambiguously suspicious behav- occasionally ask themselves these two questions deliber-

ior. Evidence consistent with this idea comes from research ately, diligently scrutinizing the evidence before answering

demonstrating that people tend not to scrutinize message them, we speculate that this process frequently transpires

content from clearly honest sources (Priester and Petty 1995, outside of conscious awareness.)

2003).

To be sure, even regarding a trusted brand, consumers HYPOTHESES AND RESEARCH

can recognize strong cues suggesting that they should re- OVERVIEW

consider their trust (e.g., if Tylenol is tainted with potassium

cyanide or if Enron engages in accounting fraud). Indeed, In two experiments, we tested the hypothesis that disclaimer

people tend to be more distressed or unforgiving when an speed and brand trust would interact to predict purchase

unambiguous transgression is perpetrated by a person with intention. Specifically, we hypothesized that fast (vs. nor-

a trustworthy rather than with an untrustworthy track record mal-paced) disclaimers weaken consumers’ purchase inten-

(Komorita and Heckling 1967), by a romantic partner to tion toward trust-unknown and not-trusted brands, but not

whom one is strongly rather than weakly committed (Finkel toward trusted brands (hypothesis 1). In experiment 1, we

et al. 2002), or by a sincere brand (with whom the consumer tested this hypothesis by employing a 2 (disclaimer speed:

has a friendship-type relationship) rather than an exciting fast vs. normal-paced) # 3 (brand trust: trust-unknown vs.

not-trusted vs. trusted) factorial design. The brand was

brand (with whom the consumer has a flinglike relationship)

equally familiar across conditions.

(Aaker, Fournier, and Brasel 2004). These effects appear to

In experiment 2, we tested the hypothesis that the dis-

emerge because people perceive these unambiguous trans-

claimer speed # brand trust effect is driven by heuristic

gressions to violate an implicit or explicit relational norm.

rather than elaborative processes (hypothesis 2) by employ-

Most trust cues, however, are ambiguous rather than bla-

ing a 2 (disclaimer speed: fast vs. normal-paced) # 2 (brand

tant, allowing people broad interpretational latitude. Fast trust: trust-unknown vs. trusted) # 2 (disclaimer valence:

disclaimers fall into this ambiguous category. In contrast to negative vs. positive) factorial design. The disclaimer va-

unambiguous transgressions, there is nothing inherently un- lence manipulation varied whether the disclaimer contained

trustworthy about fast disclaimers; such disclaimers merely negative or positive information about the advertised brand.

hint at the possibility of dishonesty. Consumers must inter- In contrast to experiment 1, which maximized internal va-

pret whether this ambiguous cue is evidence of untrust- lidity by using the same unfamiliar brand across all con-

worthiness. Although the research reviewed in the previous ditions, experiment 2 bolstered external validity by using

paragraph demonstrated that people are more unforgiving an established and widely trusted brand (Gatorade) as our

when an unambiguous transgression is perpetrated by an trusted brand.

entity with whom people have a positive relationship (by a

trustworthy person, by a partner with whom one has a

strongly committed romantic relationship, or by a brand with

EXPERIMENT 1

whom one has a friendship-like bond), we suggest that the In experiment 1, all participants listened to an advertisement

opposite pattern emerges for ambiguous transgressions. Spe- for a fictitious, Canadian, best-selling wireless device com-

cifically, as discussed above, we suggest that consumers’ pany named Apollo. In the advertisement, Apollo introduced

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

912 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

a new wireless headset called the “Surity.” To hold constant eration technology to make it seem like the person on the

participants’ baseline level of information about the brand, other end of the line is standing right next to you. Even on

all participants heard about a poll in which Canadian con- windy days, your phone calls will be virtually flawless. The

sumers rated Apollo products highly in terms of design and Apollo Surity . . . Nothing’s clearer [pause] anywhere.

functionality. Next, we implemented the trust manipulation. Disclaimer: The Apollo Surity emits radiation; studies

Approximately one-third of our participants were assigned have not conclusively shown that this radiation is harmless.

to the trust-unknown brand condition in which they learned

no additional information. Another one-third were assigned After listening to the advertisement, participants com-

to the not-trusted brand condition in which they learned that pleted a two-item measure of purchase intention (e.g., “I am

Apollo is untrustworthy. The final one-third were assigned likely to purchase this brand”; 1 p strongly disagree, 7 p

to the trusted brand condition in which they learned that strongly agree; a p .95). They also completed manipulation

Apollo is trustworthy. Participants then listened to an ad- checks, estimating the disclaimer’s duration and using an

vertisement containing a disclaimer, which was presented at 11-item measure to report their trust in the brand (see the

either a fast or a normal pace. After listening to the adver- appendix; 1 p not at all, 7 p very much; a p .91). During

tisement, participants reported their purchase intention re- debriefing, participants were informed that the advertisement

garding the Apollo Surity. We hypothesized that fast dis- was fake.

claimers would diminish participants’ purchase intention in

the trust-unknown and the not-trusted brand conditions, but Results

that they would not affect participants’ purchase intention

in the trusted brand condition. Manipulation Checks. Participants in the fast disclaimer

condition estimated that the disclaimer was significantly

shorter (M p 2.82 seconds; SD p 1.65 seconds) than did

Method participants in the normal-paced disclaimer condition (M p

5.03 seconds; SD p 2.10 seconds; t(65) p –4.85, p ! .001).

Participants and Design. Seventy-three undergraduate In addition, participants in the trust-unknown (M p 3.49;

and graduate students (33 males and 40 females; Mage p SD p 0.87) and the not-trusted conditions (M p 2.80; SD

20.27 years; SDage p 2.16 years) participated in a 2 (dis- p 0.83) reported significantly less trust in the product than

claimer speed: fast disclaimer vs. normal-paced disclaimer) did those in the trusted condition (M p 4.29; SD p 1.02;

# 3 (brand trust: trust-unknown vs. not-trusted vs. trusted) F(2, 70) p 17.31, p ! .001). Pairwise comparisons revealed

between-participants factorial design. that all three of these means differed significantly from both

Materials and Procedure. All participants began the ex- of the other two means (FbF 1 .38, FtF(43–51) 1 2.72, p !

periment by reading about a fictitious Canadian company .01).

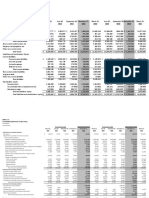

named “Apollo” that was presented as a bestseller of wire- Hypothesis Tests. As depicted in figure 1, results sup-

less devices. They learned that the May 2010 issue of Con- ported our hypotheses. The disclaimer speed # brand trust

sumer Reports Canada magazine (a fictitious magazine) re- interaction effect was significant in predicting purchase in-

ported a poll indicating that Canadian consumers gave tention (F(2, 67) p 3.35, p p .041). We probed this in-

Apollo relatively high marks in terms of design and func- teraction effect with two planned, orthogonal contrasts. First,

tionality. The final information about the poll contained our

trust manipulation, which built on work by Insko et al. FIGURE 1

(2005) and Lount (2010). In the trust-unknown condition,

participants were not exposed to any information about the EXPERIMENT 1: MEANS FOR PURCHASE INTENTION AS A

company’s trustworthiness. In the not-trusted condition, par- FUNCTION OF DISCLAIMER SPEED AND BRAND TRUST

ticipants read that Apollo is a relatively untrustworthy com-

pany, receiving a rating of 31 out of 100 on the magazine’s

Trustworthiness Index, which placed it well below the av-

erage brand. In the trusted condition, participants read that

Apollo is a highly trustworthy company, receiving a rating

of 91 out of 100, which placed it in the top 5%.

Next, all participants listened to the following advertise-

ment for a wireless headset named the Apollo Surity. In

both experiments, we designed the disclaimer speed manip-

ulation so that the fast disclaimer was unambiguously fast

but still comprehensible (approximately 4 seconds), whereas

the slow disclaimer approximated the speed of the rest of

the advertisement (approximately 7 seconds):

Advertisement: Interested in a small wireless headset with

superior sound quality? The Apollo Surity uses latest-gen-

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DISCLAIMER SPEED 913

the trust contrast pitted the trusted version of Apollo against model.) According to our hypothesized process, the mere

the other two versions (trust-unknown and not-trusted). Sec- presence of the speed cue should, via heuristic processes,

ond, the familiarity contrast pitted these other two versions undermine purchase intention for trust-unknown brands, re-

against each other. Consistent with our hypotheses, the dis- gardless of the disclaimer’s valence. In contrast, if the effects

claimer speed # trust contrast interaction effect was sig- are caused by an elaborative process, then the fast disclaimer

nificant (b p .31, t(69) p 2.91, p p .005), with fast dis- should only undermine purchase intention when the dis-

claimers significantly reducing participants’ purchase claimer valence is negative.

intention in the trust-unknown/not-trusted condition (Mfast p If this elaborative process drives our findings, then the

1.74; SDfast p 1.01; Mnorm p 2.97; SDnorm p 1.46; b p disclaimer speed # brand trust # disclaimer valence three-

–.39, t(69) p –2.86, p p .006), but not in the trusted way interaction effect should be significant. Specifically, the

condition (Mfast p 3.77; SDfast p 1.62; Mnorm p 3.00; SDnorm disclaimer speed # brand trust interaction effect should be

p 1.77; b p .24, t(69) p 1.43, p p .156). In contrast, the robust in the negative disclaimer condition, but it should

disclaimer speed # familiarity contrast interaction effect disappear (or perhaps even reverse) in the positive dis-

did not approach significance (p p .842), suggesting that claimer condition. If, however, the heuristic process drives

the effect of disclaimer speed on purchase intention was our findings, then the disclaimer speed # brand trust in-

comparable in the trust-unknown and the not-trusted con- teraction effect should not be moderated by disclaimer va-

ditions. lence. Indeed, the disclaimer speed # brand trust interaction

In sum, employing procedures that experimentally ma- effect should exhibit similar results in both the positive and

nipulated participants’ trust in the brand while holding var- negative disclaimer conditions, as the speed cue is present

iables like familiarity, popularity, and quality constant across regardless of valence.

conditions, experiment 1 demonstrated that brand trust mod- Beyond adding disclaimer valence to the design, exper-

erates the effect of disclaimer speed on purchase intention. iment 2 extended beyond experiment 1 in two additional

When consumers either lack trust information about an ad- ways. First, it sought to explore the generality of our findings

vertised brand or believe that the brand is not trustworthy, by testing our hypotheses in a new consumer domain: sports

fast disclaimers undermine their purchase intention. In con- drinks. Second, and more importantly, it manipulated brand

trast, when consumers trust an advertised brand, they appear trust in a new way. Whereas experiment 1 maximized in-

to be unaffected by disclaimer speed. ternal validity by using one unfamiliar brand across all con-

ditions, experiment 2 bolstered external validity by using

EXPERIMENT 2 not only an unfamiliar brand (Omega), but also an estab-

lished trusted brand (Gatorade).

Experiment 1 supported our hypothesis that fast disclaimers

undermine consumers’ purchase intention toward brands

when they lack relevant information or believe the brand is Method

untrustworthy, but not when they trust the brand. We have

proposed that fast disclaimer speed acts as a negative heu- Participants and Design. One hundred and fifty-eight

ristic cue, leading consumers to view the advertised undergraduate students (72 males, 85 females, and 1 par-

product—without conscious elaboration of the content of ticipant who did not indicate sex; Mage p 20.53 years; SDage

the message—as suspicious and perhaps unworthy of pur- p 1.76 years) participated in a 2 (disclaimer speed: fast

chase. However, a plausible alternative explanation for our disclaimer vs. normal-paced disclaimer) # 2 (brand trust:

results is that fast communications cause consumers to be trust-unknown [Omega] vs. trusted [Gatorade]) # 2 (dis-

suspicious of the communicator’s intent and, consequently, claimer valence: negative vs. positive) between-participants

to attend more carefully to the content of the communication factorial design.

(Petty and Cacioppo 1986; Priester and Petty 1995, 2003). Materials and Procedure. Participants listened to one of

Such scrutiny could be stronger with trust-unknown or not- eight radio advertisements. The advertisement described ei-

trusted brands than with trusted brands. Because the dis- ther Omega (trust-unknown brand) or Gatorade (trusted

claimer in experiment 1 contained negative information brand). The announcer read the disclaimer, which presented

about the brand, elaborating upon this content would likely either negative or positive information about the brand, in

decrease purchase intention, potentially yielding results sim- approximately 4 seconds (fast condition) or 7 seconds (nor-

ilar to those depicted in figure 1. mal-paced condition). Here is the text for Gatorade (the text

Fortunately, we can pit these two explanations—that the for Omega was identical except for the brand name):

experiment 1 results are due to heuristic versus elaborative

processing—against each other by adding a disclaimer va- Advertisement: Gatorade Rush! Gatorade is proud to intro-

lence manipulation (negative vs. positive). (Although pos- duce the highly caffeinated and additive-filled Gatorade Rush,

itive disclaimers are rare in real-world advertisements, in- a new heart-pumping energy drink. Gatorade Rush increases

cluding a positive disclaimer condition in this experiment your heart rate, keeping you wide awake for hours on end.

allows us to establish the mechanism driving our effects, It helps truckers stay alert for 18 straight hours. Find our ad

and it enables us to pit our heuristic-based model against in this month’s issue of Maxim.

an account inspired by Priester and Petty’s elaborative-based Negative Disclaimer: The caffeine and additives in Gat-

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

914 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

orade Rush can increase blood pressure and heart rate, which purchase intention, the three-way interaction did not ap-

can be uncomfortable. To make sure Gatorade Rush is safe proach statistical significance (b p ⫺.01, t(150) p ⫺0.18,

for you, consult your doctor. p p .857). Given that it is hazardous to draw firm conclu-

Positive Disclaimer: The caffeine and additives in Gat- sions on the basis of a null effect (even an effect with such

orade Rush can increase physical performance and mental a large p-value), we conducted several additional analyses

alertness, which can make you feel extremely driven. Achieve to examine whether the results were similar across the neg-

your goals with Gatorade Rush. ative and the positive valence conditions. First, we con-

ducted a 2 (disclaimer speed) # 2 (brand trust) ANOVA,

After listening to the advertisement, participants com-

dropping disclaimer valence from the model and seeking to

pleted a two-item measure of purchase intention (e.g., “I am

replicate the finding that fast disclaimers undermined par-

likely to purchase this brand”; 1 p strongly disagree, 7 p

ticipants’ purchase intention toward the trust-unknown

strongly agree; a p .90). They also completed manipulation

brand (Omega), but not toward the trusted brand (Gatorade).

checks, estimating the disclaimer’s duration and using an

The disclaimer speed # brand trust interaction effect was

11-item measure to report their trust in the brand (see the

significant (b p .19, t(154) p 2.72, p p .007). In the

appendix; 1 p strongly disagree to 7 p strongly agree; a

Omega condition, participants who heard the fast disclaimer

p .93). During debriefing, participants were informed that

exhibited significantly weaker purchase intention (M p

the advertisement was fake.

1.35; SD p 0.53) than did participants who heard the nor-

mal-paced disclaimer (M p 2.34; SD p 1.19; b p ⫺.50,

Results t(78) p ⫺5.06, p ! .001). In contrast, in the Gatorade

condition, no significant purchase intention difference

Manipulation Checks. Participants in the fast disclaimer

emerged for participants who heard the fast disclaimer (M

condition estimated that the disclaimer was shorter (M p

p 3.26; SD p 1.78) versus the normal-paced disclaimer

3.77 seconds; SD p 1.83 seconds) than did participants in

(M p 3.05; SD p 1.74; b p .06, t(76) p 0.54, p p .589).

the normal-paced disclaimer condition (M p 4.41 seconds;

Indeed, the disclaimer speed # brand trust interaction

SD p 2.51 seconds; t(127) p –1.67, p p .098). (This

effect on purchase intention was near-significant not only

analysis omitted five outliers who estimated that the dis-

in the negative disclaimer condition (b p .19, t(67) p 1.76,

claimer took at least 20 seconds, presumably because they

p p .084; fig. 2A), but also in the positive disclaimer con-

misunderstood the question to be asking about the length

dition (b p .18, t(83) p 1.94, p p .056; fig. 2B). For

of the entire advertisement.) In addition, participants exhib-

ited significantly greater trust in Gatorade (M p 3.93; SD Omega, participants exhibited significantly weaker purchase

p 1.09) than in Omega (M p 2.59; SD p 0.83; t(152) p intention in the fast disclaimer condition than in the normal-

8.63, p ! .001). paced disclaimer condition after both the negative disclaimer

(Mfast p 1.28; SD p 0.45 vs. Mnorm p 2.15; SD p 1.28;

Hypothesis Tests. As depicted in figure 2, results sup- b p ⫺.46, t(34) p ⫺2.98, p p .005), and the positive

ported our theoretical analysis. In a 2 (disclaimer speed) # disclaimer (Mfast p 1.42; SD p 0.59 vs. Mnorm p 2.47; SD

2 (brand trust) # 2 (disclaimer valence) ANOVA predicting p 1.15; b p ⫺.52, t(42) p ⫺3.96, p ! .001). In contrast,

FIGURE 2

EXPERIMENT 2: MEANS FOR PURCHASE INTENTION AS A FUNCTION OF DISCLAIMER SPEED

AND BRAND TRUST FOR (A) NEGATIVE AND (B) POSITIVE DISCLAIMER VALENCE

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DISCLAIMER SPEED 915

for Gatorade, participants’ purchase intention appeared to tion as a heuristic cue that the advertisement is sneaky (try-

be unaffected by disclaimer speed after both the negative ing to “pull a fast one”), and, consequently, they undermine

disclaimer (Mfast p 3.13; SD p 1.86, Mnorm p 2.75; SD p consumers’ purchase intention—but this effect only emerges

1.93; b p .10, t(33) p 0.59, p p .560), and the positive if consumers are motivated to evaluate the trustworthiness

disclaimer (Mfast p 3.36; SD p 1.75; Mnorm p 3.32; SD p of the brand. This motivation appears to be present when

1.53; b p .01, t(41) p 0.08, p p .938). consumers evaluate trust-unknown and not-trusted brands

In sum, experiment 2 demonstrated that brand trust mod- but absent when they evaluate trusted brands.

erates the effect of disclaimer speed on purchase intention

comparably whether the disclaimer contains negative or pos- Implications

itive information about the advertised product. Regardless

of disclaimer valence, when consumers lack trust infor- The present findings have theoretical implications for

mation about an advertised brand, fast disclaimers under- scholars and practical implications for advertisers and policy

mine their purchase intention. In contrast, when consumers makers. In terms of scholarship, the present findings extend

trust the brand, they appear to be unaffected by disclaimer research on the effects of advertising disclosures. Whereas

speed. That this interaction effect emerged regardless of past research has focused on the effectiveness of different

disclaimer valence (negative vs. positive) suggests that dis- disclaimer content for modifying consumer judgments (e.g.,

claimer speed exerts its effect through heuristic rather than Andrews et al. 2000), the present findings highlight the im-

elaborative processes. portance of content-irrelevant features of disclaimers by ex-

amining how disclaimer speed affects purchase intention.

GENERAL DISCUSSION The present findings also contribute to research on speed of

communication (Moore et al. 1986; Smith and Shaffer 1991,

Two experiments demonstrated that fast (vs. normal-paced) 1995). Past research has suggested that perceivers use com-

disclaimers undermine consumers’ intention to purchase the munication speed as a positive heuristic cue for the intel-

advertised product but only for consumers who have not ligence of the speaker, such that they tend to infer that fast

established trust in the brand. Experiment 1 held brand fa- speakers are intelligent (Smith and Shaffer 1995). The pre-

miliarity and popularity constant and demonstrated that the sent findings show that in the context of advertising dis-

undermining effect of fast disclaimers applies both to trust- claimers for untrusted brands, perceivers also use fast speech

unknown and to not-trusted brands, but not to trusted brands, as a negative heuristic cue for the trustworthiness of the

which suggests that consumers are only impervious to the advertiser, supporting research suggesting that consumers

effects of fast disclaimers once trust in the brand is estab- are vigilant for information that might convey ulterior mo-

lished. tives on the part of advertisers (Main et al. 2007). One

The disclaimer speed # brand trust interaction effect explanation for the divergent effects of communication

emerged even when the disclaimer presented positive in- speed in Smith and Shaffer’s (1995) studies versus in our

formation about the brand (experiment 2), which suggests own is that the abrupt change of pace between the main

that the effects of disclaimer speed work through heuristic advertisement and the end-of-advertisement disclaimer

rather than elaborative processing. That is, fast disclaimers might draw consumer attention and raise suspicion.

appear to undermine purchase intention directly rather than These results also have implications for the social cog-

by prompting consumers to scrutinize disclaimer content nition literature on conditional or goal-dependent automa-

more carefully. Past research has shown that messages from ticity (Aarts and Dijksterhuis 2000; Bargh 1989). Condi-

untrustworthy sources elicit more attention and scrutiny than tional automaticity effects occur when an automatic process

messages from trustworthy sources do (Priester and Petty is triggered only in the presence of certain conditions, such

1995). Because increased attention to positive content as the presence of a specific goal (Bargh 1989; Blair 2002).

should not reduce trust (and should, if anything, increase For example, although exposure to members of minority

it), the fact that fast positive disclaimers reduced trust in groups frequently triggers automatic stereotypes of those

our research suggests that our findings are unlikely to have groups, this automatic stereotype activation depends upon

resulted from increased elaboration from suspicious con- the presence of perceivers’ goals, contextual factors, and

sumers. Of course, there is no reason to believe that these features of the group members (Blair 2002; Dasgupta and

elaborative and heuristic effects are mutually exclusive. Greenwald 2001; Macrae, Bodenhausen, and Milne 1995;

There may be times when consumers will respond to fast Mitchell, Nosek, and Banaji 2003; Sinclair and Kunda 1999;

disclaimers by scrutinizing the message more carefully. For Spencer et al. 1998). Similarly, we suggest that consumers’

example, if consumers are particularly motivated to form purchase intentions following fast disclaimers for trust-un-

an accurate impression of the trustworthiness of the adver- known, not-trusted, and trusted brands derive from a con-

tised brand, they may be more likely to respond with an ditionally automatic process. Consumers who are motivated

elaborative type of processing of the disclaimer content to evaluate the trustworthiness of an advertisement’s claims

rather than a heuristic type of processing of the disclaimer (such as those hearing advertisements for trust-unknown or

speed cue (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). not-trusted brands) are influenced by heuristic trust cues like

Overall, the results support the theoretical analysis we disclaimer speed, whereas consumers who are not so mo-

advanced in the introduction: fast disclaimers appear to func- tivated (such as those hearing advertisements for trusted

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

916 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

brands) are not. To our knowledge, this is the first condi- put the “action” in the trusted brand conditions: threats, such

tional automaticity effect to be shown in the consumer do- as potentially untrustworthy advertising tactics, should ac-

main. tivate consumers’ motivation to defend their positive views

In terms of practical implications, the present findings can of the brand. This account would also suggest that consum-

help advertisers make wise decisions in light of the pro- ers in the trust-unknown or not-trusted brand conditions are

crustean constraints they face when writing and producing responding in an unbiased manner to the disclaimer infor-

advertisements. For example, advertisers frequently have mation. Although the current experiments were not designed

only 30 seconds to convey their message, and regulatory to test for motivated defense of trusted brands, the pattern

agencies sometimes require that the advertisement include of data provides evidence that tentatively contradicts this

a disclaimer. Should advertisers convey the disclaimer in- alternative account. Consumers’ purchase intention toward

formation as quickly as possible, or should they convey it trusted brands was not significantly influenced by disclaimer

at a normal pace? At first glance, the former approach seems speed in any of the experiments. Rather, it was consumers’

preferable. After all, it has the advantages of maximizing views of trust-unknown and not-trusted brands that were

the available time to convey the primary message while reliably influenced by the manipulation. That is, consumers

simultaneously glossing over undesirable product informa- do not seem to be responding to threats to their views of

tion. In contrast, the latter seems to emphasize the negative trusted brands by increasing their trust and purchase inten-

aspects of the product while chewing up precious seconds tion. Instead, they appear to be ignoring any information

that could have been used to drive home the primary mes- provided by disclaimer speed in advertisements for trusted

sage. The present research suggests, however, that fast dis- brands, while responding to information provided by dis-

claimers undermine consumers’ purchase intention for trust- claimer speed in advertisements for trust-unknown and not-

unknown or not-trusted brands, adverse effects that were trusted brands.

absent for trusted brands. As such, our findings suggest that A second limitation is that the present work did not ex-

advertisers promoting unfamiliar or not-trusted brands may amine several intriguing features of disclaimers that may

want to employ normal-paced disclaimers, whereas adver- moderate our central effects. For example, the effects of

tisers promoting trusted brands have greater latitude to use disclaimer speed may be moderated by whether consumers

fast disclaimers to save additional seconds for the adver- believe that advertisers freely chose to include the disclaimer

tisement’s primary message. or were required by law to include it. The effects of fast

These considerations lead us to a final implication, this disclaimers for untrusted brands may also diminish as con-

one for policy makers. The present results suggest that any sumers become inured to such disclaimers in light of their

policies that regulate disclaimer content but not disclaimer widespread use within a given industry. In addition, the

speed could infuse systematic bias favoring some companies content of an advertisement or a disclaimer may also mod-

over others. Such policies would allow companies whom erate the effects of disclaimer speed. Although experiment

consumers already trust to pack the required disclaimer con- 2 indicated that disclaimer content valence (i.e., negative

tent into just a few seconds without undermining consumers’ vs. positive information about the brand) did not moderate

trust and purchase intention, whereas these policies would our key effects, it would be interesting to explore whether

end up forcing companies whom consumers either distrust the current effects might be moderated by, for example, the

or do not know to devote more time to this required content, credibility (or boldness) of the claim in the advertisement

presenting it at a slower speed to maintain consumers’ trust

or by the consumer domain (e.g., perhaps fast disclaimers

and purchase intention. If advertisers use disclaimer speeds

might not undermine consumers’ purchase intention toward

approximating the ones we employed in the present research,

untrusted brands in domains in which fast disclaimers are

then trusted brands could devote only 13% of the adver-

normative).

tisement’s duration to the disclaimer (4 seconds in a 30-

A third limitation is the possibility that, in today’s cultural

second spot), whereas other brands might have to devote

23% of the advertisement’s duration to the disclaimer (7 climate, consumers frequently perceive disclaimers as char-

seconds in a 30-second spot). Thus, regulation of disclaimer acteristic of an industry rather than of the specific brand in

content but not disclaimer speed may systematically dis- a particular advertisement. If so, then perhaps the inferences

advantage some companies over others. consumers make after listening to a particular advertisement

containing a disclaimer apply to all brands in that industry.

Although our experiments demonstrated that consumers re-

Limitations, Future Research, and Strengths spond differently to fast (vs. normal-paced) disclaimers de-

The present research has limitations that can serve as pending on whether the advertisement is for an untrusted

springboards for future research. First, we have argued that or a trusted brand, we did not ask participants to report their

once consumers trust a brand, they no longer evaluate the purchase intention toward more than one brand. As such,

brand’s trustworthiness, which renders them impervious to we had no way of knowing whether, for example, the adverse

heuristic trust cues. However, an alternative possibility is effects of fast disclaimers on consumers’ purchase intention

that such consumers are motivated to defend against infor- generalize to their purchase intention toward other brands

mation that is potentially threatening to their established in that same industry.

trust beliefs (Hoch and Deighton 1989). This account would To address this issue (albeit in a preliminary way), we

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DISCLAIMER SPEED 917

conducted an experiment in which we randomly assigned they might be inattentive to ambiguous trust cues because

78 students to listen to a fast-disclaimer or a normal-paced- they have developed confidence that the brand is unlikely

disclaimer advertisement for Taco Bell. We sought to rep- to take advantage of them (see the present work). But it is

licate the finding that fast disclaimer speed undermines con- precisely this confidence that makes consumers so unfor-

sumers’ purchase intention toward not-trusted brands (a giving when they encounter the sort of unambiguous trans-

separate sample of 56 students reported moderate-to-low gressions they cannot simply overlook (see the work by

trust in Taco Bell) and, more importantly, to demonstrate Aaker et al. 2004).

that this adverse effect of fast disclaimers would not gen-

eralize to other brands in the same industry. In this case, CONCLUSION

we examined whether listening to the Taco Bell advertise-

ment with the fast versus the normal-paced disclaimer in- Two experiments demonstrated that fast disclaimers under-

fluenced consumers’ purchase intention toward Taco Bell, mine consumers’ purchase intention toward trust-unknown

as well as toward Chipotle and Qdoba, two other major and not-trusted brands, but not toward trusted brands. These

Mexican-style fast food chains. After listening to the ad- effects, which are driven by heuristic rather than elaborative

vertisement for Taco Bell, participants reported their pur- processes, suggest that consumers become impervious to

chase intention (on a 1–7 scale) toward all three brands. ambiguous trust cues once they trust the brand.

Results supported the hypothesis that the adverse effects of

fast disclaimers are limited to the advertised brand rather APPENDIX

than generalizing to other brands in the same industry. Spe-

cifically, although participants exhibited (marginally) lower BRAND TRUST MEASURE

purchase intention toward Taco Bell if they had heard the

fast rather than the slow disclaimer (M p 2.49 vs. 3.20;

1. I trust this brand.a

t(76) p –1.88, p p .06), the effect of disclaimer speed on 2. This brand is predictable.a

participants’ purchase intention toward Chipotle and Qdoba 3. This brand is dependable.a

(in composite form) did not approach significance (M p 4. This brand is reliable.a

5.28 vs. 5.37; t(76) p –0.37, p p .72). Analyzing Chipotle 5. This brand is truthful.a

6. This brand is competent.b

and Qdoba separately revealed identical conclusions—the 7. This brand has integrity.b

effect of disclaimer speed did not approach significance. 8. This brand is responsive.b

These preliminary data suggest that the disclaimer speed 9. I rely on this brand.c

effects are limited to the advertised brand. 10. This is an honest brand.c

11. This brand is safe.c

These limitations notwithstanding, the present research

a

also has notable strengths. First, we experimentally manip- Adapted or derived from Holmes and Rempel (1989).

b

ulated brand trust, across two different product categories, Adapted or derived from Sirdeshmukh et al. (2002).

c

Adapted or derived from Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001).

using both an existing brand (experiment 2) and a fictitious

brand we developed for this research (experiment 1); al-

though both of these approaches have limitations, they com-

plement each other and allow us to draw firmer causal con- REFERENCES

clusions about our effects. Second, the present emphasis on Aaker, Jennifer, Susan Fournier, and S. Adam Brasel (2004),

an ambiguous trust cue (disclaimer speed) complements pre- “When Good Brands Do Bad,” Journal of Consumer Re-

vious research on unambiguous brand transgressions (Aaker search, 31 (1), 1–16.

et al. 2004), which has demonstrated that consumers tend Aarts, Henk and Ap Dijksterhuis (2000), “Habits as Knowledge

to be less forgiving when they have an intimate, friendship- Structures: Automaticity in Goal-Directed Behavior,” Journal

like relationship rather than a casual, fling-like relationship of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (1), 53–63.

with the brand. Taken together, the story emerging from a Andrews, J. Craig, Scot Burton, and Richard G. Netemeyer (2000),

“Are Some Comparative Nutrition Claims Misleading? The

theoretical integration of the present experiments with the Role of Nutrition Knowledge, Ad Claim Type and Disclosure

work by Aaker et al. (2004) is that consumers’ negative Conditions,” Journal of Advertising, 29 (3), 29–42.

responses to potential trust violations are strongest (a) when Andrews, J. Craig, Richard G. Netemeyer, and Srinivas Durvasula

a brand with which they have an intimate or trusting rela- (1991), “Effects of Consumption Frequency on Believability

tionship commits an unambiguous offence (as in the work and Attitudes toward Alcohol Warning Labels,” Journal of

by Aaker et al. 2004) and (b) when a brand with which they Consumer Affairs, 25 (2), 323–38.

lack such a relationship commits an ambiguous offence (as Bargh, John A. (1989), “Conditional Automaticity: Varieties of

in the present work). To be sure, future research will be Automatic Influence in Social Perception and Cognition,” in

Unintended Thought, ed. James S. Ulman and John A. Bargh,

required to discern if this integrative model is accurate (es- New York: Guilford, 3–51.

pecially given that the key moderating constructs differ Blair, Irene V. (2002), “The Malleability of Automatic Stereotypes

somewhat across the two lines of research), but this pattern and Prejudice,” Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6

of results makes good theoretical sense. If consumers have (3), 242–61.

a trusting, friendship-like relationship with a brand, then Briñol, Pablo and Richard E. Petty (2003), “Overt Head Move-

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

918 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

ments and Persuasion: A Self-Validation Analysis,” Journal current Disclosures to Correct Invalid References,” Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 84 (6), 1123–39. of Consumer Research, 26 (4), 307–22.

Campbell, Margaret C. (1995), “When Attention-Getting Adver- Komorita, S. S. and John Heckling (1967), “Betrayal and Rec-

tising Tactics Elicit Consumer Inferences of Manipulative In- onciliation in a Two-Person Game,” Journal of Personality

tent: The Importance of Balancing Benefits and Investments,” and Social Psychology, 6 (3), 349–53.

Journal of Consumer Psychology, 4 (3), 225–54. Lount, Robert B., Jr. (2010), “The Impact of Positive Mood on

Campbell, Margaret C. and Amna Kirmani (2000), “Consumers’ Trust in Interpersonal and Intergroup Interactions,” Journal

Use of Persuasion Knowledge: The Effects of Accessibility of Personality and Social Psychology, 98 (3), 420–33.

and Cognitive Capacity on Perceptions of an Influence Macrae, C. Neil, Galen V. Bodenhausen, and Alan B. Milne (1995),

Agent,” Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (1), 69–83. “The Dissection of Selection in Person Perception: Inhibitory

Chaudhuri, Arjun and Morris B. Holbrook (2001), “The Chain of Processes in Social Stereotyping,” Journal of Personality and

Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Perfor- Social Psychology, 69 (3), 397–407.

mance: The Role of Brand Loyalty,” Journal of Marketing, Main, Kelley J., Darren W. Dahl, and Peter R. Darke (2007), “De-

65 (2), 81–93. liberative and Automatic Bases of Suspicion: Empirical Evi-

Darke, Peter R. and Robin J. B. Ritchie (2007), “The Defensive dence of the Sinister Attribution Error,” Journal of Consumer

Consumer: Advertising, Deception, Defensive Processing, Psychology, 17 (1), 59–69.

and Distrust,” Journal of Marketing Research, 44 (1), 114– Mason, Marlys J., Debra L. Scammon, and Xiang Fang (2007),

27. “The Impact of Warnings, Disclaimers, and Product Experi-

Dasgupta, Nilanjana and Anthony G. Greenwald (2001), “On the ence on Consumers’ Perceptions of Dietary Supplements,”

Journal of Consumer Affairs, 41 (1), 74–99.

Malleability of Automatic Attitudes: Combating Automatic

McAllister, Daniel J. (1995), “Affect- and Cognition-Based Trust

Prejudice with Images of Admired and Disliked Individuals,”

as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organiza-

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81 (5), 800–

tions,” Academy of Management Journal, 38 (1), 24–59.

814.

Miller, Norman, Goeffrey Maruyama, Rex J. Beaber, and Keith

Doney, Patricia M. and Joseph P. Cannon (1997), “An Examination

Valone (1976), “Speed of Speech and Persuasion,” Journal

of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 34 (4), 615–24.

of Marketing, 61 (2), 35–51.

Mitchell, Jason P., Brian A. Nosek, and Mahzarin R. Banaji (2003),

Erdem, Tulin and Joffre Swait (2004), “Brand Credibility, Brand

“Contextual Variations in Implicit Evaluation,” Journal of

Consideration, and Choice,” Journal of Consumer Research,

Experimental Psychology: General, 132 (3), 455–69.

31 (1), 191–98.

Moog, Carol (1990), “Are They Selling Her Lips?” Advertising

Federal Trade Commission (2000), “Advertising Retail Electricity and Identity, New York: Morrow.

and Natural Gas Disclosures and Disclaimers,” http://busi- Moore, Danny L., Douglas Hausknecht, and Kanchana Thamo-

ness.ftc.gov/documents/bus47-advertising-retail-electricity- daran (1986), “Time Compression, Response Opportunity,

and-natural-gas. and Persuasion,” Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (1),

Fein, Steven (1996), “Effects of Suspicion on Attributional Think- 85–99.

ing and the Correspondence Bias,” Journal of Personality and Moorman, Christine, Rohit Deshpandé, and Gerald Zaltman

Social Psychology, 70 (6), 1164–84. (1993), “Factors Affecting Trust in Market Research Rela-

Finkel, Eli J., Caryl E. Rusbult, Madoka Kumashiro, and Peggy tionships,” Journal of Marketing, 57 (1), 81–101.

A. Hannon (2002), “Dealing with Betrayal in Close Rela- Moorman, Christine, Gerald Zaltman, and Rohit Deshpandé

tionships: Does Commitment Promote Forgiveness?” Journal (1992), “Relationships between Providers and Users of Mar-

of Personality and Social Psychology, 82 (6), 956–74. ket Research: The Dynamics of Trust within and between

Friestad, Marian and Peter L. Wright (1994), “The Persuasion Organizations,” Journal of Marketing Research, 29 (3),

Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion At- 314–29.

tempts,” Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (1), 1–31. Morgan, Robert M. and Shelby D. Hunt (1994), “The Commit-

——— (1995), “Persuasion Knowledge: Lay People’s and Re- ment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing,” Journal of

searchers’ Beliefs about the Psychology of Advertising,” Marketing, 58 (3), 20–38.

Journal of Consumer Research, 22 (1), 62–74. Packard, Vance O. (1991), The Hidden Persuaders, London: Pen-

Garbarino, Ellen and Mark S. Johnson (1999), “The Different Roles guin Books.

of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Rela- Petty, Richard E. and John T. Cacioppo (1986), Communication

tionships,” Journal of Marketing, 63 (2), 70–87. and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude

Hoch, Stephen J. and John Deighton (1989), “Managing What Change, New York: Springer-Verlag.

Consumers Learn from Experience,” Journal of Marketing, Petty, Richard E. and Duane T. Wegener (1999), “The Elaboration

53 (2), 1–20. Likelihood Model: Current Status and Controversies,” in

Holmes, John G. and John K. Rempel (1989), “Trust in Close Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology, ed. Shelly Chai-

Relationships,” in Review of Personality and Social Psy- ken and Yaacov Trope, New York: Guilford, 37–72.

chology, Vol. 10, ed. Clyde Hendrick, London: Sage, 187– Priester, Joseph R. and Richard E. Petty (1995), “Source Attri-

220. butions and Persuasion: Perceived Honesty as a Determinant

Insko, Chester A., Jeffrey L. Kirchner, Brad Pinter, Jamie Efaw, of Message Scrutiny,” Personality and Social Psychology Bul-

and Tim Wildschut (2005), “Interindividual–Intergroup Dis- letin, 21 (6), 637–54.

continuity Effect as a Function of Trust and Categorization: ——— (2003), ”The Influence of Spokesperson Trustworthiness

The Paradox of Expected Cooperation,” Journal of Person- on Message Elaboration, Attitude Strength, and Advertising

ality and Social Psychology, 88 (2), 365–85. Effectiveness,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13 (4),

Johar, Gita and Carolyn J. Simmons (2000), “The Use of Con- 408–21.

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DISCLAIMER SPEED 919

Rogers, Wendy A., Nina Lamson, and Gabriel K. Rousseau (2000), through Its Impact on Message Elaboration,” Personality and

“Warning Research: An Integrative Perspective,” Human Fac- Social Psychology Bulletin, 17 (6), 663–69.

tors, 42 (1), 102–39. ——— (1995), “Speed of Speech and Persuasion: Evidence for

Simpson, Jeffry A. (2007), “Foundations of Interpersonal Trust,” Multiple Effects,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulle-

in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, 2nd ed., tin, 21 (10), 1051–60.

ed. Arie W. Kruglanski and E. Tory Higgins, New York: Guil- Spencer, Steven J., Steven Fein, Connie T. Wolfe, Christina Fong,

ford, 587–607. and Meghan A. Dunn (1998), “Automatic Activation of Ste-

Sinclair, Lisa and Ziva Kunda (1999), “Reactions to a Black Pro-

reotypes: The Role of Self-Image Threat,” Personality and

fessional: Motivated Inhibition and Activation of Conflicting

Social Psychology Bulletin, 24 (11), 1139–52.

Stereotypes,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

77 (5), 885–904. Stewart, David W. and Ingrid M. Martin (2004), “Advertising Dis-

Sirdeshmukh, Deepak, Jagdip Singh, and Barry Sabol (2002), closures: Clear and Conspicuous or Understood and Used?”

“Consumer Trust, Value, and Loyalty in Relational Ex- Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 23 (2), 183–92.

changes,” Journal of Marketing, 66 (1), 15–37. Urban, Glen L., Fareena Sultan, and William J. Qualls (2000),

Smith, Stephen M. and David R. Shaffer (1991), “Celerity and “Placing Trust at the Center of Your Internet Strategy,” Sloan

Cajolery: Rapid Speech May Promote or Inhibit Persuasion Management Review, 42 (1), 39–48.

This content downloaded from

103.244.172.219 on Sun, 12 May 2019 13:24:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Journal of Consumer Research, Inc.: The University of Chicago PressDokument9 SeitenJournal of Consumer Research, Inc.: The University of Chicago PressLucia DiaconescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Perceptionsof Brand Mentionin Magazinesby Levelof InvolvementDokument15 SeitenConsumer Perceptionsof Brand Mentionin Magazinesby Levelof InvolvementShyamrajsinh JethwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attitudes of Audience Towards Repeat Advertisements A Case of Pepsi AdsDokument4 SeitenAttitudes of Audience Towards Repeat Advertisements A Case of Pepsi AdsDev RishabhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Deceptive Advertising On Customer Behavior and Attitude: Literature ViewpointDokument5 SeitenImpact of Deceptive Advertising On Customer Behavior and Attitude: Literature ViewpointNoor SalmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand CredibilityDokument9 SeitenBrand CredibilityHumaira SalmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposal (39038) PDFDokument7 SeitenResearch Proposal (39038) PDFshaiqua TashbihNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposal (39038)Dokument7 SeitenResearch Proposal (39038)shaiqua TashbihNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ad Skepticism The Consequences of DisbeliefDokument17 SeitenAd Skepticism The Consequences of DisbeliefvarshaalakshmipathyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Airtel CREATIVITYINADSDokument22 SeitenAirtel CREATIVITYINADSAlex AransiolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Customer Perception Towards HDFC LimitedDokument13 SeitenA Study On Customer Perception Towards HDFC LimitedKHUSHBOO BABELNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognition and Affect in Consumer Decision Making: Conceptualization and Validation of Added Constructs in Modified InstrumentDokument21 SeitenCognition and Affect in Consumer Decision Making: Conceptualization and Validation of Added Constructs in Modified InstrumentTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research ProposalDokument6 SeitenResearch ProposalAsad Ullah KhalidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovating Analytics: How the Next Generation of Net Promoter Can Increase Sales and Drive Business ResultsVon EverandInnovating Analytics: How the Next Generation of Net Promoter Can Increase Sales and Drive Business ResultsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020 The Effect of Endorser and Corporate Credibility On Perceived Risk and Consumer Confidence The Case of Technologically Complex ProductsDokument22 Seiten2020 The Effect of Endorser and Corporate Credibility On Perceived Risk and Consumer Confidence The Case of Technologically Complex ProductsRizky UtamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Marketing AssociationDokument14 SeitenAmerican Marketing AssociationvincentNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Brand Loyalty of Tooth Paste Among Consumers in North CoimbatoreDokument9 SeitenA Study On Brand Loyalty of Tooth Paste Among Consumers in North Coimbatorefaizu naazNoch keine Bewertungen

- KHRM21. BS - Agency IssuesHRMDokument14 SeitenKHRM21. BS - Agency IssuesHRMProf. Dr. Anbalagan ChinniahNoch keine Bewertungen

- What's Done in The Dark Will Be Brought To The LightDokument14 SeitenWhat's Done in The Dark Will Be Brought To The LightcallmebymochiNoch keine Bewertungen

- P .MostafizurRahman 01Dokument10 SeitenP .MostafizurRahman 01Vinh VũNoch keine Bewertungen

- IJMS Vol4 Iss3 Paper4 800 808 PDFDokument9 SeitenIJMS Vol4 Iss3 Paper4 800 808 PDFHarshit AgrawalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Satisfaction With Life Insurance: A Benchmarking SurveyDokument16 SeitenConsumer Satisfaction With Life Insurance: A Benchmarking SurveyArnab DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ample Research Proposal On The Influence and Impact of Advertising To Consumer Purchase MotiveDokument14 SeitenAmple Research Proposal On The Influence and Impact of Advertising To Consumer Purchase MotiveAmit Singh100% (1)

- The Curious Case of Behavioral Backlash: Why Brands Produce Priming Effects and Slogans Produce Reverse Priming EffectsDokument18 SeitenThe Curious Case of Behavioral Backlash: Why Brands Produce Priming Effects and Slogans Produce Reverse Priming Effectsalidani92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Asia Paci Fic Management Review: Danny Tengti KaoDokument9 SeitenAsia Paci Fic Management Review: Danny Tengti KaofutulashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Achieving a Safe and Reliable Product: A Guide to Liability PreventionVon EverandAchieving a Safe and Reliable Product: A Guide to Liability PreventionNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 The Impact of Advertisements On The Buying Behavior of Senior High School Students of Sto. Niño AcademyDokument37 Seiten1 The Impact of Advertisements On The Buying Behavior of Senior High School Students of Sto. Niño AcademyIzzy Mei CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dual Credibility Model: The Influence of Corporate and Endorser Credibility On Attitudes and Purchase IntentionsDokument12 SeitenThe Dual Credibility Model: The Influence of Corporate and Endorser Credibility On Attitudes and Purchase IntentionsKreunik ArtNoch keine Bewertungen

- PM PDFDokument14 SeitenPM PDFCindy Rizka Maulina IINoch keine Bewertungen

- American Marketing AssociationDokument15 SeitenAmerican Marketing AssociationGulderay IklassovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand Credibility Research Paper 4Dokument8 SeitenBrand Credibility Research Paper 4AKSHAT SHARMANoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketig Managment NaguDokument9 SeitenMarketig Managment NaguNageshwar singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Loyalty and Customer Loyalty ProgramsDokument23 SeitenCustomer Loyalty and Customer Loyalty ProgramsJoanne ZhaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand PromotionDokument55 SeitenBrand PromotionsidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer PerceptionsDokument11 SeitenConsumer PerceptionsFadli LieyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hybrid Detailing: A Proposed Model For Pharmaceutical Sales: I-Manager's Journal On Management August 2010Dokument8 SeitenHybrid Detailing: A Proposed Model For Pharmaceutical Sales: I-Manager's Journal On Management August 2010Kington JiangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ad and Brand PerceptionDokument15 SeitenAd and Brand Perceptionirenek100% (1)

- Advertsiement Skepticism and Brand Extension Evaluation - Versao - Enanpad - 2013 - VF1Dokument16 SeitenAdvertsiement Skepticism and Brand Extension Evaluation - Versao - Enanpad - 2013 - VF1Caio Henrique Noronha JuniorNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of Brand Image and Brand Attitude Toward Buying Interest (The Case of Garuda Indonesia and Lion Air)Dokument8 SeitenThe Influence of Brand Image and Brand Attitude Toward Buying Interest (The Case of Garuda Indonesia and Lion Air)Muhammad AzizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misr University For Science and TechnologyDokument7 SeitenMisr University For Science and Technologymahmoud said moietNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Research Proposal On The Influence and Impact of Advertising To Consumer Purchase MotiveDokument19 SeitenSample Research Proposal On The Influence and Impact of Advertising To Consumer Purchase MotiveallanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijm 11 05 060Dokument9 SeitenIjm 11 05 060IAEME PublicationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand Awareness V1ycelq5Dokument26 SeitenBrand Awareness V1ycelq5anislaaghaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Customer Advocate and the Customer Saboteur: Linking Social Word-of-Mouth, Brand Impression, and Stakeholder BehaviorVon EverandThe Customer Advocate and the Customer Saboteur: Linking Social Word-of-Mouth, Brand Impression, and Stakeholder BehaviorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Selling and AdDokument9 SeitenPersonal Selling and Adtrang nguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Brand Marketing On Consumer Decision MakingDokument12 SeitenImpact of Brand Marketing On Consumer Decision MakingIJRASETPublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Advertisement On Brand Loyalty and Consumer Buying BehaviorDokument13 SeitenThe Role of Advertisement On Brand Loyalty and Consumer Buying BehaviorAli MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Power of PersuasionDokument10 SeitenThe Power of PersuasionPeerIndexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Brand Equity Advertisement and Hedonic CDokument10 SeitenImpact of Brand Equity Advertisement and Hedonic Cengr.fmrushoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Turning Complaining Into Customer LoyaltyDokument56 SeitenTurning Complaining Into Customer LoyaltyKUSUMA WIDYA TANTRINoch keine Bewertungen

- Dan Project WorkDokument55 SeitenDan Project Workjega okoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper 002Dokument15 SeitenPaper 002Abhay MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management - Role of E-Commerce - Dr. Mahabir NarwalDokument12 SeitenManagement - Role of E-Commerce - Dr. Mahabir NarwalImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Word of Mouth MArketingDokument6 SeitenWord of Mouth MArketingUTKARSH PANDEYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alvarezalvarez 2005Dokument21 SeitenAlvarezalvarez 2005Miruna CucosNoch keine Bewertungen

- A STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFDokument6 SeitenA STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFRamana RamanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFDokument6 SeitenA STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFzeeshanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SIP Brand PromoDokument23 SeitenSIP Brand PromosidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hanza Ee 2011Dokument12 SeitenHanza Ee 2011Riska ResnadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- City Spring 2019Dokument14 SeitenCity Spring 2019Ahsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Analytics Course Outline V3Dokument3 SeitenBusiness Analytics Course Outline V3Ahsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- ProcessDokument1 SeiteProcessAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 52-Project DetailDokument1 Seite52-Project DetailAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 52-Project DetailDokument1 Seite52-Project DetailAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50-MBA Project Detail1Dokument1 Seite50-MBA Project Detail1Ahsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epo - Morning Mid Term Exam Schedule City Campus - Fall 2019Dokument10 SeitenEpo - Morning Mid Term Exam Schedule City Campus - Fall 2019Ahsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- DocxDokument15 SeitenDocxAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCM ReportDokument10 SeitenSCM ReportAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flash Memory IncDokument3 SeitenFlash Memory IncAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quiz 3solutionDokument5 SeitenQuiz 3solutionAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urdu NotesDokument2 SeitenUrdu NotesAhsan Iqbal100% (1)

- Netflix, Inc. Consolidated Balance SheetsDokument4 SeitenNetflix, Inc. Consolidated Balance SheetsAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Changes in Upcoming Schedule of Charges (Jan-Jun-2019) : ADC ServicesDokument1 SeiteChanges in Upcoming Schedule of Charges (Jan-Jun-2019) : ADC ServicesAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- OBL Grade SheetDokument12 SeitenOBL Grade SheetAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- DTTL Tax Pakistanhighlights 2018 PDFDokument5 SeitenDTTL Tax Pakistanhighlights 2018 PDFAhsan IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Machine Learning ProjectDokument37 SeitenMachine Learning ProjectAish Gupta100% (3)

- Research ProposalDokument13 SeitenResearch ProposalPRAVEEN CHAUDHARYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efficiency of Student Mobility ProgramsDokument11 SeitenEfficiency of Student Mobility ProgramsMF Mike100% (1)

- Validity TestDokument3 SeitenValidity Testsympatico081100% (3)

- Fraser 2016Dokument4 SeitenFraser 2016Loan TrầnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jam Rodriguez Activity #4Dokument7 SeitenJam Rodriguez Activity #4Sandra GabasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan Kinder ScienceDokument16 SeitenLesson Plan Kinder Sciencemayflor certicioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 09 - Chapter 2 PDFDokument43 Seiten09 - Chapter 2 PDFIrizh DanielleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Time Series Forecasting Using Deep Learning NetworkDokument12 SeitenFinancial Time Series Forecasting Using Deep Learning NetworkLuminous LightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminological ResearchDokument5 SeitenCriminological ResearchkimkimkouiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design and Development of Production Monitoring SystemDokument83 SeitenDesign and Development of Production Monitoring Systemammukhan khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shm04 PP ManualDokument9 SeitenShm04 PP ManualMarcelo Vieira100% (1)

- PTDokument60 SeitenPTIbrahim Eldesoky82% (11)

- DLL Earth and Life Week 1Dokument3 SeitenDLL Earth and Life Week 1Queency Panaglima PadidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practicum Portfolio TemplateDokument23 SeitenPracticum Portfolio TemplateMarjorie Lee LathropNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrep Module 2 SLMDokument25 SeitenEntrep Module 2 SLMShiela Mae Ceredon33% (3)

- Oral ScriptDokument7 SeitenOral ScriptArdent BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A PrécisDokument6 SeitenHow To Write A PrécisKimberly De Vera-AbonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 10 English DLL Q1 2022 2023 WEEK 6Dokument5 SeitenGrade 10 English DLL Q1 2022 2023 WEEK 6Sai Mendez Puerto Judilla-SolonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flexible Evaluation Mechanism (FEM) Understanding Culture Society and PoliticsDokument1 SeiteFlexible Evaluation Mechanism (FEM) Understanding Culture Society and Politicsgenesisgamaliel montecinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gayong - Gayong Sur, City of Ilagan, Isabela Senior High SchoolDokument6 SeitenGayong - Gayong Sur, City of Ilagan, Isabela Senior High SchoolRS Dulay100% (1)

- Developing Emotional IntelligenceDokument3 SeitenDeveloping Emotional IntelligenceTyrano SorasNoch keine Bewertungen