Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Guía Evidencia Práctica Clínica Extubación

Hochgeladen von

Matías Bcrro0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

59 Ansichten21 SeitenEste documento presenta guías sobre la retirada del tubo endotraqueal. Describe los riesgos de la intubación prolongada, indicaciones para la extubación como la capacidad del paciente para mantener la vía aérea y respirar espontáneamente de manera adecuada, y posibles complicaciones como la hipoxemia o hipercapnia después de la extubación. También cubre la evaluación de la preparación del paciente para la extubación a través de pruebas como una respiración espontánea con bajos niveles de presión positiva

Originalbeschreibung:

Procedimiento y Cuidados en retirada de TET

Originaltitel

Retirada Del Tubo Endotraqueal

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenEste documento presenta guías sobre la retirada del tubo endotraqueal. Describe los riesgos de la intubación prolongada, indicaciones para la extubación como la capacidad del paciente para mantener la vía aérea y respirar espontáneamente de manera adecuada, y posibles complicaciones como la hipoxemia o hipercapnia después de la extubación. También cubre la evaluación de la preparación del paciente para la extubación a través de pruebas como una respiración espontánea con bajos niveles de presión positiva

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

59 Ansichten21 SeitenGuía Evidencia Práctica Clínica Extubación

Hochgeladen von

Matías BcrroEste documento presenta guías sobre la retirada del tubo endotraqueal. Describe los riesgos de la intubación prolongada, indicaciones para la extubación como la capacidad del paciente para mantener la vía aérea y respirar espontáneamente de manera adecuada, y posibles complicaciones como la hipoxemia o hipercapnia después de la extubación. También cubre la evaluación de la preparación del paciente para la extubación a través de pruebas como una respiración espontánea con bajos niveles de presión positiva

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 21

Guías de Evidencia Basada en la Práctica Clínica AARC

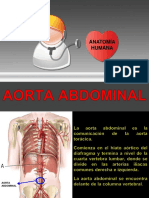

Retirada del tubo endotraqueal

CKPC - Revisión y actualización 2007

1.0 PROCEDIMIENTO 2.1.11 Extubación Accidental

Retirada electiva del tubo endotraqueal en con requerimiento de reintubación de

pacientes adultos, pediátricos y neonatales. emergencia25,28

2.2 La Extubación puede resultar en las

2.0 DESCRIPCION/DEFINCION siguientes complicaciones

En la decisión de discontinuar la ventilación 2.2.1Obstrucción de la vía aérea

mecánica es preciso socavar los riesgos entre la superior por laringoespasmo29-32

ventilación mecánica prolongada y el fallo de 2.2.2Edema laringeo33-37

extubacion12. Esta guía se enfocará en los 2.2.3Obstrucción subglotica38

predictores que ayudan a la decisión de retirar el 2.2.4 Edema pulmonar39-41

tubo orotraqueal, al procedimiento mencionado 2.2.5 Síndrome de aspiración

como extubación y a las intervenciones pulmonar19,42

postextubación inmediatas que pueden evitar la 2.2.6 Alteración del intercambio

potencial reintubación. Esta revisión no gaseoso

abordará el destete de la ventilación mecánica,

la extubación accidental, ni la extubación en

3.0 Medio Ambiente

pacientes terminales.

El tubo endotraqueal debe ser retirado en un

2.1 Los riegos de la intubación

ambiente donde el paciente pueda tener una

translaríngea prolongada incluyen pero no se

adecuada monitorización de los parámetros

limitan a:

fisiológicos y donde se encuentren

2.1.1 Sinusitis3,4

inmediatamente disponibles equipos de

2.1.2 Injuria de las Cuerdas emergencia y personal de la salud entrenada en

Vocales5 el manejo de la vía aérea. (ver 10.0 y 11.0).

2.1.3 Injuria Laringea6-8

2.1.4 Estenosis Laringea6,7 4.0 INDICACIONES/OBJETIVOS

2.1.5 Estenosis Subglótica en Cuando se considere que el control de la vía

neonatos9 -11 y niños12 aérea proporcionado por el tubo ya no sea

2.1.6 Injuria Traqueal13-16 necesario para continuar con el cuidado del

2.1.7 Hemoptisis17 paciente, el tubo debe ser retirado. Deben

2.1.8 Aspiracion18,19 encontrarse determinantes objetivos y

2.1.9 Infección Pulmonar20-23 subjetivos de la mejoría de la condición clínica

2.1.10 Oclusión del Tubo subyacente o mejoría de la función pulmonar

endotraqueal24-27 y/o intercambio gaseoso antes de la extubación2.

Para aumentar la probabilidad de éxito en la

extubación el paciente debe ser capaz de

conservar la vía aérea permeable y mantener inspirada de oxígeno a través de

una respiración espontanea adecuada. En la vía aérea superior47

general, esto requiere que el paciente presente 6.1.2 Obstrucción aguda de la

adecuado: drive central inspiratorio, fuerza de vía aérea superior secundaria a

los músculos respiratorios, tos fuerte para laringoespasmo29-32

eliminar secreciones, función laríngea, estado 6.1.3Desarrollo de edema

nutricional, y no tener efectos de los sedantes y pulmonar post extubacion39-41

bloqueantes neuromusculares 6.1.4 Broncoespasmo48,49

4.1En ocasiones una obstrucción aguda 6.1.5 Desarrollo de atelectasia o

de la vía aérea artificial por secreciones colapso pulmonar50

o deformaciones mecánicas generan la

6.1.6Aspiración Pulmonar18,19,42

necesidad de una inmediata remoción

6.1.7 Hipoventilacion51,52

del tubo endotraqueal. Para mantener un

6.2Puede desarrollarse hipercapnia

efectivo intercambio gaseoso será

después de la extubación. Las causas

necesario reintubar al paciente o realizar

incluyen pero no se limitan a

otras técnica para reestablecer la vía

aérea (ej, manejo de la vía aérea de 6.2.1 Obstrucción de la vía

forma quirúrgica).26,27,43 aérea superior como resultado

de edema de tráquea, cuerdas

4.2 En aquellos pacientes en los cuales

vocales o laringe33-38

esta documentada la ineficacia de

tratamientos médicos futuros el tubo 6.2.2 Debilidad de los músculos

puede ser retirado a pesar de las respiratorios53,54

indicaciones anteriores44,45 6.2.3 Trabajo respiratorio

excesivo 55-59

5.0 CONTRAINDICACIONES 6.2.4 Broncoespasmo48,49

No existen contraindicaciones absolutas para la 6.3Cuando la incapacidad médica es el

extubacion. Algunos pacientes para mantener un motivo de la extubación podría ocurrir

adecuado intercambio gaseoso después de la la muerte del paciente.

extubación, pueden requerir uno o más de los

siguientes: ventilación no invasiva, presión 7.0 LIMITACIONES EN LA

positiva continua en la vía aérea, fracción METODOLOGÍA/VALIDACIÓN DE

inspirada de oxígeno alta o reintubación. RESULTADOS

Inmediatamente después de la extubación o por La predicción de los resultados de la extubación

un tiempo más prolongado, los reflejos de es de significativa importancia clínica. Tanto el

protección de la vía aérea pueden estar retrasos como la falla de extubación están

deprimidos18,46. Se deben considerar medidas asociados con pobres resultados para el

para prevenir la aspiración. paciente.1,2 La literatura en estos temas está

limitada a unas pocas medidas objetivas

6.0 PELIGROS/COMPLICACIONES validadas para predecir con exactitud los

6.1Puede generarse Hipoxemia resultados de la extubación en pacientes

postextubación. Las causas incluye pero no se individuales1,2,60-63 La falla de extubación no es

limita a necesariamente indicador de falla de la práctica

6.1.1 Falla en la entrega médica. Los pacientes pueden requerir una

adecuada de la fracción reintubación inmediata o luego de un periodo de

tiempo debido a una inapropiada programación inspirada de oxigeno provista a

de la extubación, progresión de la enfermedad través de un dispositivo de

de base o desarrollo de un nuevo evento. Por lo oxigeno simple (FIO2 ≤ 0.4 a

tanto debe realizarse una prueba de extubación a 0.5) y con niveles bajos de

aquellos pacientes marginales en los que se presión positiva al final de la

espera que requieran reintubación. inspiración (PEEP) ≤ 5 a 8

La tasa de falla de extubación reportada alcanza cmH2O

el 1.8% - 18,6% en adultos36, 6365,2.7%-22% en 8.1.2 Capacidad de mantener un

niños,66-70y puede llegar a40%-60%para valor adecuado de pH (pH ≥

lactantes con bajo peso al nacer.71-75 7.25)2y presión parcial de CO2

En la práctica clínica estándar, para la remoción arterial durante la ventilación

del tubo endotraqueal debe incluirse un espontanea74,75

monitoreo postextubación exhaustivo, 8.1.3 Culminación con éxito de

identificación inmediata de falla respiratoria, una prueba de respiración

mantenimiento de la vía aérea permeable, y en espontanea (PRE) de 30-120

caso de estar clínicamente indicado, intentos de minutos realizada con bajos

reestablecer la vía aérea artificial por medio de niveles de CPAP (ej,5cmH2O) o

la reintubación y/o con técnicas quirúrgicas. Las bajos niveles de presión de

tasas de fracaso y complicaciones dela soporte (ej 5-7

extubación se pueden utilizar como monitor de cmH2O)demostrando un

calidad. adecuado patrón respiratorio,

intercambio gaseoso,

8.0 EVALUACIÓN DE LA PREPARACION estabilidad hemodinámica y

PARA LA EXTUBACIÓN confort subjetivo77-81

Cuando el paciente no requiera la vía aérea 8.1.4Frecuencia respiratoria

artificial, el tubo endotraqueal debe ser retirado. durante la prueba de

Los pacientes deben presentar remisión de la respiración espontanea, en

causa que precipitó la falla respiratoria adultos< 35 respiraciones por

subyacente, ser capaces de mantener una minuto54; en infantes y en niños

adecuada ventilación espontanea e intercambio la frecuencia respiratoria

gaseoso. La determinación de la preparación aceptable decrece inversamente

para la extubación debe ser individualizada con la edad y puede ser medida

usando las siguientes pautas. con buena repetitividad con un

8.1 Los pacientes que requirieron vía estetoscopio82

aérea artificial para facilitar el 8.1.5 Adecuada fuerza de los

tratamiento de la falla respiratoria deben músculos respiratorios83-85

considerarse para ser extubados cuando 8.1.6 Presión inspiratoria

hayan cumplido con criterios máxima > -30 cmH2O86-

89

establecidos 64,76

.Ejemplos de estos .Aunqueen la práctica clínica

criterios incluyen pero no se limitan a: actual se pueden aceptar una

8.1.1 Capacidad de mantener presión inspiratoria máxima >

una adecuada presión parcial de -20 cmH2O90,91

oxigeno arterial (PaO2/FIO2 > 8.1.7 Capacidad vital >

150-200) con una fracción 10mL/kg del peso corporal

ideal92y en neonatos en niños el VD/VT ≤ 0.5

>150mL/m289 equivale al 96% de extubación

8.1.8 Presión transdiafragmática exitosa, entre 0.51-0.64

media durante la ventilación equivale al 60% de extubación

espontánea <15% de la exitosa y 0.65 equivale al 20%

maxima93,94 de extubación exitosa 105,106

8.1.9 En adultos, ventilación 8.1.15 Presión de oclusión de la

minuto espontanea exhalada < vía aérea en los primeros 0.100

10 L/min86 segundos (P0.1) < 6 cm H2O y

8.1.10 En adultos, el índice de cuando regulariza los valores

respiración rápida y superficial para la presión inspiratoria

(índice de FR/VT) ≤105 máxima (PIM), como indica

respiraciones /minuto (valor P0.1/PIM, predice un éxito de

predictivo positivo [VPP]de extubación del 88% y del 98%

0.78)90; en infantes y niños, las de las veces respectivamente.107-

109

variables estandarizadas por la (esta medición es

edad o el peso son más útiles. El principalmente una herramienta

índice CROP modificado de investigación)

(compliance, resistencia, 8.1.16 Ventilación voluntaria

oxigenación, presión de máxima>al doble de la

86

ventilación)por encima de un ventilación minuto en reposo

umbral ≥ 0.1-0.15 mL· 8.1.17 En lactantes pre término,

mmHg/respiraciones/min/kg) las pruebas de ventilación

(sensibilidad de 83% y minuto vs la evaluación clínica

especificidad de 53%) puede ser estándar resulta en una

una herramienta de evaluación disminución del tiempo de

superior al FR/VT modificado ≤ extubación110

8-11 respiraciones/min/mL/kg 8.1.19 Pico flujo espiratorio

(sensibilidad de 74%y (PFE) ≥ 60L/min después de 3

67,68,95

especificidad de 74%) intentos de tos, medidos con un

8.1.11 Compliance torácica > espirómetro en linea111,112

25 mL/cmH2O96 8.1.20 Tiempo de recuperación

8.1.12 Trabajo respiratorio< 0.8 de la ventilación minutos hasta

J/L97-102 alcanzar valores basales previos

8.1.13Consumo de oxigeno a la prueba de respiración

total< 15%, especialmente para espontanea.113

aquellos pacientes con 8.1.21 Presión inspiratoria

insuficiencia respiratoria máxima sostenida (PIMS) >

crónica que requieren 57.5 unidad de presión tiempo

ventilación mecánica (sensibilidad y especificidad

prolongada (sensibilidad 100%; 1.0) predicen resultados de

especificidad 87%)102-104 extubación14

8.1.14 Relación espacio muerto 8.1.22 En neonatos, la

– volumen tidal (VD/VT) < 0.6; compliance del sistema

respiratorio (Crs, derivada de extubación. (Cociente de

VT/PIP-PEEP) ≤ 0.9 riesgo,RR= 4.0; 95% intervalo

mL/cmH2Oestá asociada con de confianza (CI95) 1.8 a 8.9)121

falla de extubación, mientras 8.2.3 Manejo de

que un valor ≥ 1.3mL/cm H2O secreciones 1,63,119,120

está asociado con éxito de 8.3 Además de la resolución del proceso

extubación115 que llevo al paciente a requerir una vía

8.1.23 Los recién nacidos aérea artificial, en todos los pacientes

prematuros extubados debe considerarse antes de la

directamente de ventilación de extubación los siguientes:

baja frecuencia sin una prueba 8.3.1 Que no se anticipe la

de presión positiva continúa en necesidad de reintubación

la vía aérea por el tubo 8.3.2 Conocer los factores de

endotraqueal (CPAP) riesgo de falla de extubación:

demostraron una tendencia a

8.3.2.1 Los pacientes

aumentar las chances de

con alto riesgo de falla

extubación exitosa (RR = 0.45,

de la extubación son los

CI95 (0.19, 1.07), NNT 10116

que presentan: admisión

8.1.24 Índices integrados que a una ICU medica, edad

miden capacidad vital (CV, > a 70 o < a 24 meses,

valor de corte= mayor severidad de la

635mL),relación entre enfermedad desde el

frecuencia respiratoria y weaning, hemoglobina

volumen tidal(f/VT, punto de <10 mg/dL, uso de

corte = 88respiraciones/min/L) sedación intravenosa

y presión espiratoria máxima continua, mayor

(MEP, punto de corte = 28 duración de la

cmH2O)80,117 ventilación mecánica,

8.2Además del tratamiento de la falla presencia de un

respiratoria, la vía aérea artificial se síndrome o condición

coloca para proteger la vía aérea. La médica crónica,

resolución de la causa que llevo al condición médica o

paciente a no proteger la vía aérea tiene quirúrgica de la vía

que estar resuelta, debe presentar pero aérea conocida,63,70,

no se limita a: aspiración frecuente,121,

8.2.1 Adecuado nivel de pérdida de los reflejos

conciencia 118-120 de protección de la vía

8.2.2 Adecuados reflejos de aerea,119,120

protección de la víaaérea119,120 8.3.2.2 Factores de

8.2.2.1 Fuerza tusígena Riesgo o antecedentes

disminuida (grado 0-2) medida de vía aérea dificultosa:

con el test de la tarjeta blanca y síndrome o condiciones

abundantes secreciones son congénitas asociadas

predictores de falla de con inestabilidad

cervical (ie, Klippel- 8.3.3 La presencia de

Feil o trisomia 21); obstrucción de la vía aérea o

acceso físico de la vía edema laríngeo evaluados

aérea limitado (halo- mediante la disminución de la

vest u obstáculos fuga de aire alrededor del tubo

anatómicos); múltiples endotraqueal con respiraciones

intentos fallidos de a presión positiva. 37,132-139

laringoscopia directa 8.3.3.1 El porcentaje de

por un laringoscopista fuga por el manguito o

experto o múltiples la diferencia entre el

intentos fallidos volumen tidal espirado

seguidos de intubación medido con el balón

traqueal usando un inflado y luego

fibrobroncoscopio o desinflado en un modo

estilete nasal o la controlado por

necesidad de colocar volumen≥15.5%

una máscara laríngea 122- (sensibilidad 75%,

129

especificidad 72%).132-

138

8.3.2.3 En la población Todavía no se

pediátrica de cirugía encontró que este test

cardiotorácica, la sea predictivo en un

presencia de una o más estudio con pacientes de

de estas variables cirugía cardiotorácica

139

aumenta la probabilidad

de falla de extubación: 8.3.3.2 En niños la fuga

edad menor a 6 meses, de aire puede ser un

historia de nacimiento predictor de estridor

prematuro, falla postextubación

cardiaca congestiva e dependiente de la edad.

hipertensión pulmonar Una fuga de aire > 20

130

cmH2O fue predictor de

8.3.2.4 Para pacientes estridor post extubación

pediátricos, mediciones en niños ≥ 7 años de

validadas de la función edad (sensibilidad de

respiratoria al lado de la 83%, especificidad de

cama identificaron 80%), pero no fue

puntos de corte de predictor en niños < 7

bajo(< 10%) y alto años de edad37 .

riego (> 25%) de falla 8.3.3.3 El test de fuga

de extubación que ha sido predictor de

pueden ser útiles para estridor post extubación

discutir pero no pueden o falla de extubación

ser aplicados para para niños con

31

riesgo individual patología de la vía

aérea; pacientes con neonatos de alto riesgo

trauma,140 crup,141 pero no en niños (riesgo

después de una cirugía relativo, RR = 0.49,

traqueal. 142 CI95 0.01, 19.65) o

8.3.4 Evidencia de función adultos (RR = 0.95,

hemodinámica adecuada y CI95 0.52, 1.72)61,163

estable 2,143-146 8.3.9.4 La

8.3.5 Evidencia de funciones no administración

respiratorias estables147-150 profiláctica de

8.3.6 Valores de electrolitos corticoides en pacientes

dentro de los rangos con

normales 151-153 laringotraquebronquitis

8.3.7 Evidencia de la se correlaciona con una

disminución de la desnutrición, disminución de la tasa

función muscular respiratoria y de reintubación164,165

drive central.154-158 8.3.9.5 El citrato de

8.3.8 La literatura de anestesia cafeína reduce el riesgo

indica que el paciente no debe de apneas en niños pero

ingerir comida o líquidos por no reduce el riesgo de

boca por un periodo de tiempo falla de extubación166

previo a la manipulación de la 8.3.9.6 El tratamiento

vía aérea. La alimentación con metilxantinas

transpilórica continua durante estimula la respiración

el procedimiento de extubación y reduce el índice de

continúa siendo controversial. apneas (RR = 0.47,

159,160 CI95 (0.32, 0.70).

8.3.9 Se debe considerar [Número necesario a

medicación profiláctica antes de tratar (NNT) 3.7, CI95

la extubación para evitar o (2.7, 6.7)] en neonatos

reducir la severidad de con drive central

complicaciones post extubación disminuido,

como ser especialmente los

lactantes que tienen

8.3.9.1 Considerar el

bajo peso extremo.167

uso de lidocaína

profiláctica para

prevenirla tos y/o 9.0 EVALUACIÓN DE LOS RESULTADOS

laringoespasmo en La remoción del tubo endotraqueal debe ser

pacientes de riesgo 161,162 seguida de una adecuada ventilación

8.3.9.2La espontanea a través de la vía aérea natural,

administración oxigenación, y no requerir reintubación.

profiláctica de 9.1 El resultado clínico debe ser

esteroides puede ser de evaluado mediante la evaluación física,

ayuda para prevenir re auscultación, mediciones invasivas y no

intubaciones en

invasivas de intercambio gaseoso y prongs [RR = 0.59,

radiografía torácica. CI95 (0.41, 0.85); NNT

9.2 La calidad del procedimiento puede 5, CI95 (3, 14)]174

ser evaluado a través del monitoreo de 9.5.1.3 En adultos, el

las complicaciones y la necesidad de uso rutinario de

reintubación. ventilación a presión

9.3 La calidad dela extubación puede positiva no invasiva

ser evaluada examinando la frecuencia post extubación como

de reintubaciones y la frecuencia de BIPAP no

175- 177

complicaciones. estáadmitido

9.4 Los casos en que un paciente se 9.5.1.4 En pacientes con

autoextuba y no requiere reintubación, enfermedad pulmonar

son sugerentes de que la extubación obstructiva crónica

debió ser considerada antes.168-173 (EPOC), el uso de

9.5 Algunos pacientes pueden requerir presión positiva

algún tipo de intervenciones para continua de la vía aérea

mantener un adecuado intercambio (CPAP) de 5 cm H2O

gaseoso o soporte postextubación ov entilación con

,independientemente de la ventilación presión de soporte

mecánica controlada (PSV) de 15cm H2O ha

9.5.1 Soporte ventilatorio no mejorado el intercambio

invasivo gaseoso, disminuido la

fracción de shunt

9.5.1.1 Los lactantes

intrapulmonar y

extubados a ventilación

disminuido el trabajo

a presión positiva

respiratorio. 178

intermitente a través de

una cánula nasal (VPPI) 9.5.2 Terapia Médica

tuvieron menos Postextubación

probabilidad de fallar 9.5.2.1 La levo –

la extubación que adrenalina en aerosol es

aquellos lactantes tan efectiva como la

extubados a ventilación epinefrina racémica en

nasal a presión positive aerosol para el

continua de la vía aérea tratamiento del edema

(VPPC)[RR = 0.21, laríngeo post

CI95 (0.10, 0.45); NNT extubación en niños 35

3, CI95 (2, 5)]52 9.5.2.2 No se han

9.5.1.2 En neonatos y realizado estudios

lactantes prematuros, randomizados en

binasal prong CPAP es neonatos para evaluar el

más efectivo en rol de la epinefrina

prevenir reintubaciones racémica nebulizada en

que single nasal el estridor post

179

ornasopharyngeal extubación

9.5.2.3 El helio puede 10.1.4 Sondas de aspiración

aliviar los síntomas de faríngeas y traqueales

una obstrucción parcial 10.1.5Bolsa de resucitación

de la vía aérea y del manual autoinflable o no.

estridor resultante, 10.1.6 Mascaras faciales de

mejorar el confort del tamaño apropiado

paciente, disminuir el 10.1.7 Cánulas de mayo.

trabajo respiratorio y

10.1.8 Tubos endotraqueales de

prevenir la

varios tamaños con y sin balón.

reintubacion.57,58,140

10.1.9 Equipamiento de

9.5.3 Terapia de Diagnóstico

intubación translaringea (hojas

9.5.3.1Para pacientes de laringoscopio, palas, baterías

con complicaciones extras, lubricante quirúrgico,

post extubación como jeringas para inflar el balón,

ser estridor u mandril)

obstrucción, la

10.1.10 Intercambiadores de

fibrobroncoscopia

TET de distintos tamaños.

puede proporcionar una

10.1.11 Mascara laríngea de

inspección directa de

varios tamaños

vía aérea y una

10.1.12 Equipamiento para el

intervención terapéutica

restablecimiento de la vía aérea

(aspiración de

quirúrgica de

secreciones, instilación

emergencia(escalpelo, lidocaína

de drogas, remoción o

con epinefrina, tamaño

aspiración de cuerpos

apropiado de tubo endotraqueal

extraños).180,181

y cánula de traqueostomía)

10.1.13 Tubos nasogástricos de

10.0 RECURSOS

varios tamaños

Antes de la extubación debe prepararse el

10.1.14 Oxímetro de pulso

equipamiento para una reintubación de

10.1.15 Monitor cardiaco de dos

emergencia y personal capacitado debe estar

canales

rápidamente disponible. Los siguientes

equipamientos y suministros deben estar 10.1.16 Suministros para

próximos al paciente en cantidades suficientes y extracción de sangre arterial y

en condiciones de ser usados análisis de gases en sangre

10.1 Equipamiento 10.1.17 Medicación para

sedación, analgesia, bloqueantes

10.1.1 Fuente de oxigeno

neuromusculares, y prevención

10.1.2 Dispositivos para

del aumento de la presión

entregar mezcla de gases

intracraneana como se indica

enriquecida en oxigeno

por la situación individual

10.1.3 Fuente de aspiración de

10.1.18 Dispositivos para la

alto volumen y sonda de

detección de dióxido de carbóno

aspiración

(dispositivos cualitativos y/o 11.1 Personal adecuadamente entrenado

cuantitativos) para detectar la falla cardiopulmonar

10.2 Personal debe estar rápidamente disponible.

10.2.1 El personal de la salud 11.2 La evaluación respiratoria debe

acreditado con conocimientos y incluir: signos vitales, evaluación del

habilidad para la evaluación y estado neurológico, permeabilidad de la

manejo de la vía aérea del vía aérea, hallazgos auscultatorios,

paciente debe determinar la trabajo respiratorio y estado

idoneidad de la extubación, hemodinámico.

estar disponible para evaluar el 11.3 Equipamiento

éxito y comenzar las 11.2.1 Oxímetro de pulso

intervenciones adecuadas en 11.2.2 Monitor cardiaco de 2

caso de producirse canales

complicaciones inmediatas. 11.2.3 Tensiómetro y

Personal calificado en estetoscopio

intubación endotraqueal y en la

11.2.4 Capnógrafo

inserción de una vía aérea

artificial debe estar

12.0 FRECUENCIA

inmediatamente disponible

cuando se realiza una No existe consenso sobre el tiempo apropiado

extubación. de colocación de una traqueostomía en

pacientes con ventilación mecánica. Cualquier

10.2.2 El personal de la salud

recomendación debe tener en cuenta la

acreditado con conocimiento

población de pacientes, la etiología del daño

documentado y habilidad

respiratorio, conocer el tiempo esperado de

demostrada en dispositivos de

duración de la ventilación mecánica y realizar

administración de oxígeno y

un balance entre riesgo/beneficio de continuar

aspiración de la vía aérea puede

recibiendo ventilación mecánica a través de una

prestar apoyo durante el proceso

traqueotomía. Las recomendaciones anteriores

de extubación.

se basaron en un consenso de expertos.2,182,183

10.2.3En el momento de

12.1Existen pocos datos acerca de la

obstrucción de la vía aérea

tasa de extubación exitosa posterior a

artificial aguda, cualquiera que

una falla de extubación.

tenga manejo de la vía aérea

puede retirar el tubo 12.1.1 Muchos estudios clínicos

endotraqueal para salvar la vida incluyen solo el primer intento

del paciente.160 de extubación

12.1.2 En un estudio descriptivo

en niños, 174/2794 presentaron

11. 0 MONITOREO

falla de extubación [tasa de falla

El monitoreo del periodo postextubación

de extubación del 6.2%, CI95

incluye asegurar que el equipamiento, personal,

5.3,7.1] después del primer

y medicación estén rápidamente disponibles en

intento; 27% (65/174) fallaron

la emergencia y fenómenos postextubacion160

un segundo intento de

extubación; de esos

pacientes,22fueron extubados of CriticalCare Medicine. Chest 2001;120(6

exitosamente después del tercer Suppl):375S-395S.

intento.70 3. Holzapfel L, Chevret S, Madinier G, Ohen

F,Demingeon G, Coupry A, Chaudet M.

13.0 PRECAUCIONES ESTANDARES. Influence of

El personal de salud debe entrenarse en las long-term, oro- or nasotracheal intubation on

precauciones estandares para todos los nosocomialmaxillary sinusitis and pneumonia:

pacientes, seguir las recomendaciones del results of aprospective, randomized, clinical

Centro de prevención y control de infecciones trial. Crit Care Med 1993;21(8):1132-1138.

para el control de la exposición a tuberculosis, e 4. Guerin JM, Lustman C, Meyer P, Barbotin-

instituir las precauciones empíricamente Larrieau F.Nosocomial sinusitis in pediatric

necesarias de aire, gotas y contacto en intensive care patients(comment). Crit Care

pacientes en los que se espera la confirmación Med 1990;18(8):902.

pero se tienen sospecha de infecciones 5. Kastanos N, EstopaMiro R, Marin Perez A,

graves.184-189 XaubetMir A, Agusti-Vidal A. Laryngotracheal

injury due toendotracheal intubation: incidence,

14.0 IDENTIFICACIÓN, ADAPTACIÓN Y evolution, and predisposingfactors: a

DISPONIBILIDAD prospective long-term study. CritCare Med

1983;11(5):362-367.

14.1 Adaptación Publicación original 6. Colice GL, Stukel TA, Dain B. Laryngeal

Respir Care 1999; 44 (1): 85-90

14.2 Desarrollo de la guía complicationsof prolonged intubation. Chest

Capítulo de Kinesiología en el Paciente 1989;96(4):877-884.

Crítico 7. Santos PM, Afrassiabi A, Weymuller EA Jr.

Lic. Klga Ftra Agustina Quijano Risk factorsassociated with prolonged

Lic. Klgo Ftra Gustavo Plotnikow intubation and laryngealinjury. Otolaryngol

14.3 Disponibilidad Head Neck Surg 1994;111(4):453-459.

www.sati.org.ar

14.4 Conflictos de interés 8. Benjamin B. Prolonged intubation injuries of

Ninguno the larynx:endoscopic diagnosis, classification,

and treatment.Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol

1993;160:1-15.

9. Sherman JM, Lowitt S, Stephenson C,

BIBLIOGRAFIA

Ironson G. Factorsinfluencing acquired

subglottic stenosis in infants.J Pediatrics

1986;109(2):322-327.

1. Epstein SK. Decision to extubate. Intensive

Care Med2002;28(5):535-546. 10. Marcovich M, Pollauf F, Burian K.

Subglottic stenosisin newborns after mechanical

2. MacIntyre NR, Cook DJ, Ely EW Jr, Epstein

ventilation. ProgPediatrSurg 1987;21:8-19.

SK, FinkJB, Heffner JE, et al. Evidence-based

guidelines forweaning and discontinuing 11. Parkin JL, Stevens MH, Jung AL. Acquired

ventilatory support: a collectivetask force and congenitalsubglottic stenosis in the infant.

facilitated by the American Collegeof Chest Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol 1976; 85(5 Pt1): 573-

Physicians; the American Association 581.

forRespiratory Care; and the American College 12. Wiel E, Vilette B, Darras JA, Scherpereel P,

Leclerc F.Laryngotracheal stenosis in children

after intubation.Report of five mechanically ventilated patients.Am Rev Respir

cases.PaediatrAnaesthes1997;7(5):415-419. Dis 1990;142(3):523-528.

13. Stauffer JL, Olson DE, Petty TL. 23. Harris H, Wirtschafter D, Cassady G.

Complications andconsequences of Endotracheal intubationand its relationship to

endotracheal intubation and tracheotomy:a bacterial colonizationand systemic infection of

prospective study of 150 critically ill newborn infants. Pediatrics1976;58(6):816-823.

adultpatients. Am J Med 1981;70(1):65-76. 24. Rivera R, Tibbals J. Complications of

14. Hoeve LJ, Eskici O, Verwoerd endotracheal intubationand mechanical

CD.Therapeutic reintubationfor post-intubation ventilation in infants and children.Crit Care

laryngotracheal injury inpreterm infants.Int J Med 1992;20(2):193-199.

PediatrOtorhinolaryngol1995;31(1):7-13. 25. Khan FH, Khan FA, Irshad R, Kamal RS.

15. Stauffer JL, Silvestri RE. Complications of Complicationsof endotracheal intubation in

endotrachealintubation, tracheostomy, and mechanically ventilatedpatients in a general

artificial airways.Respir Care 1982;27(4):417- intensive care unit. J PakMed Assoc

434. 1996;46(9):195-198.

16. Spear RM, Sauder RA, Nichols DG. 26. Cohen IL, Weinberg PF, Fein IA, Rowinski

Endotracheal tuberupture, accidental extubation, GS. Endotrachealtube occlusion associated with

and tracheal avulsion:three airway catastrophes the use of heatand moisture exchangers in the

associated with significantdecrease in leak intensive care unit. CritCare Med

pressure. Crit Care Med1989;17(4):701-703. 1988;16(3):277-279.

17. Keceligil HT, Erk MK, Kolbakir F, Yildrim 27. Skoulas IG, Kountakis SE. Endotracheal

A, YilmanM, Unal R. Tracheoinnominate artery tube obstruction:a rare complication in laser

fistula followingtracheostomy. CardiovascSurg ablation of recurrentlaryngeal papillomas. Ear

1995;3(5):509-510. Nose Throat J2003;82(7):504-506, 512.

18. Leder SB, Cohn SM, Moller BA. Fiberoptic 28. Black AE, Hatch DJ, Nauth-Misir N.

endoscopicdocumentation of the high incidence Complications ofnaotracheral intubation in

of aspirationfollowing extubation in critically ill neonates, infants and children:a review of 4

trauma patients.Dysphagia 1998;13(4):208-212. years’ experience in a children’shospital. Br J

19. Goitein KJ, Rein AJ, Gornstein A. Incidence Anaesth 1990;65(4):461-467.

of aspirationin endotracheally intubated infants 29. Backus WW, Ward RR, Vitkun SA,

and children.Crit Care Med 1984;12(1):19-21. Fitzgerald D,Askanazi J. Postextubation

20. Garibaldi RA, Britt MR, Coleman ML, laryngeal spasm in anunanesthetized patient

Reading JC, Pace NL. Risk factors for with Parkinson’s disease. J ClinAnesth

postoperative pneumonia.Am J Med 1991;3(4):314-316.

1981;70(3):677-680. 30. Guffin TN, Har-el G, Sanders A, Lucente

21. Kerver AJ, Rommes JH, Mevissen-Verhage FE, Nash M. Acute postobstructive pulmonary

EA, HulstaertPF, Vos A, Verhoef J, Wittebol P. edema. OtolaryngolHead Neck Surg

Prevention ofcolonization and infection in 1995;112(2):235-237.

critically ill patients: aprospective randomized 31. Wilson GW, Bircher NG. Acute pulmonary

study. Crit Care Med1988;16(11):1087-1093. edema developingafter laryngospasm: report of

22. Torres A, Aznar R, Gatell JM, Jiminez P, a case. J OralMaxillofacSurg 1995;53(2):211-

Gonzalez J,Ferrer A, et al. Incidence, risk, and 214.

prognosis factors ofnosocomial pneumonia in

32. Young A, Skinner TA. Laryngospasm gastric acid aspiration:influence of two

following extubationin children anesthetic techniques. AnesthAnalg

(letter).Anaesthesia 1995;50(9):827. 1980;59(11):862-864.

33. Hartley M, Vaughan RS. Problems 43. Kapadia FN, Bajan KB, Singh S, Mathew B,

associated with trachealextubation. Br J Anaesth Nath A,Wadkar S. Changing patterns of airway

1993;71(4):561-568. accidents in intubatedICU patients. Intensive

34. Darmon JY, Rauss A, Dreyfuss D, Bleichner Care Med 2001;27(1):296-300.

G,Elkharrat D, Schlemmer B, et al. Evaluation 44. Task Force on Ethics of the Society of

of riskfactors for laryngeal edema after tracheal Critical CareMedicine. Consensus report on the

extubation inadults and its prevention by ethics of foregoinglife-sustaining treatments in

dexamethasone: a placebocontrolled,double- the critically ill.Crit CareMed

blind, multicenter study. 1990;18(12):1435-1439.

Anesthesiology1992;77(2):245-251. 45. Truog RD, Cist AF, Brackett SE, Burns JP,

35. Nutman J, Brooks LJ, Deakins KM, CurleyMA, Danis M, et al. Recommendations

Baldesare KK, Witte MK, Reed MD. Racemic for end-of-lifecare in the intensive care unit:

versus l-epinephrineaerosol in the treatment of The Ethics Committeeof the Society of Critical

postextubation laryngealedema: results from a Care Medicine. Crit CareMed

prospective, randomized, double-blind study. 2001;29(12):2332-2348.

Crit Care Med 1994;22(10):1591- 1594. 46. Ajemian MS, Nirmul GB, Anderson MT,

36. Kemper KJ, Benson MS, Bishop MJ. Zirlen DM,Kwasnik EM. Routine fiberoptic

Predictors of postextubationstridor in pediatric endoscopic evaluationof swallowing following

trauma patients.CritCare Med 1991;19(3);352- prolonged intubation: implicationsfor

355. management. Arch Surg2001;136(4):434-437.

37. Mhanna MJ, Zamel YB, Tichy CM, Super 47. Guglielminotti J, Constant I, Murat I.

DM. The“air leak” test around the endotracheal Evaluation ofroutine tracheal extubation in

tube, as a predictorof postextubation stridor, is children: inflating or suctioningtechnique? Br J

age dependent inchildren. Crit Care Med Anaesth 1998;81(5):692-695.

2002;30(12):2639-2643. 48. Tait AR, Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Munro

38. Vauthy PA, Reddy R. Acute upper airway HM, SeiwertM, Pandit UA. Risk factors for

obstructionin infants and children: evaluation by perioperative adverserespiratory events in

the fiberopticbronchoscope. Ann children with upper respiratorytract infections.

OtolRhinolLaryngol 1980;89(5 Pt1):417-418. Anesthesiology 2001;95(2):299-306.

39. Willms D, Shure D. Pulmonary edema due 49. Wong DH, Weber EC, Schell MJ, Wong AB,

to upperairway obstruction in adults. Chest AndersonCT, Barker SJ. Factors associated with

1988;94(5):1090-1092. postoperativepulmonary complications in

40. Kamal RS, Agha S. Acute pulmonary patients with severechronic obstructive

oedema: a complicationof upper airway pulmonary disease.

obstruction. Anaesthesia1984;39(5):464-467. AnesthAnalg1995;80(2):276-284.

41. Guinard JP. Laryngospasm-induced 50. Flenady VJ, Gray PH. Chest physiotherapy

pulmonary edema.Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol for preventingmorbidity in babies being

1990;20(2):163-168. extubated from mechanicalventilation.

42. Arandia HY, Grogono AW. Comparison of Cochrane Database Syst Rev2002;

the incidenceof combined “risk factors” for (2):CD000283. Lopata M, Onal E. Mass

loading, sleep apnea, and thepathogensis of 61. Davis PG, Henderson-Smart DJ.

obesity hypoventilation. Am Rev Respir Intravenous dexamethasonefor extubation of

Dis 1982;126(4):640-645. newborn infants. CochraneDatabase Syst Rev

52. Davis PG, Lemyre B, de Paoli AG. Nasal 2001;(4):CD000308.

intermittentpositive pressure ventilation 62. Sinha SK, Donn SM. Weaning newborns

(NIPPV) versus nasalcontinuous positive from mechanicalventilation. SeminNeonatol

airway pressure (NCPAP) forpreterm neonates 2002;7(5):421-428.

after extubation. Cochrane DatabaseSyst Rev 63. Epstein SK. Predicting extubation failure: is

2001;(3):CD003212. it in (on)the cards? (editorial) Chest

53. Mier A, Laroche C, Agnew JE, Vora H, 2001;120(4):1061-1063.

Clarke SW,Green M, Pavia D. Tracheobronchial 64. DeHaven CB Jr, Hurst JM, Btanson RD.

clearance in patientswith bilateral diaphragmatic Evaluation oftwo different extubation criteria:

weakness. Am RevRespir Dis 1990;142(3):545- attributes contributingto success. Crit Care Med

548. 1986;14(2):92-94.

54. Cohen CA, Zagelbaum G, Gross D, Roussos 65. Ely EW, Baker AM, Dunagan DP, Burke

C, MacklemPT. Clinical manifestations of HL, SmithAC, Kelly PT, et al. Effect on the

inspiratory musclefatigue. Am J Med duration of mechanicalventilation of identifying

1982;73(3):308-316. patitents capable ofbreathing spontaneously. N

55. Sundaram RK, Nikolic G. Successful Engl J Med

treatment ofpost-extubation stridor by 1996;335(25):1864-1869.

continuous positive airwaypressure. Aneasthes 66. el-Khatib MF, Baumeister B, Smith PG,

Intensive Care1996;24(3):392-393. Chatburn RL,Blumer JL. Inspiratory

56. Hertzog JH, Siegel LB, Hauser GJ, Dalton pressure/maximal inspiratorypressure: does it

HJ. Noninvasivepositive-pressure ventilation predict successful extubation in criticallyill

facilitates trachealextubation after infants and children? Intensive Care

laryngotracheal reconstruction in children.Chest Med1996;22(3):264-268.

1999;116(1):260-263. 67. Farias JA, Alia I, Esteban A, Golubicki AN,

57. Kemper KJ, Izenberg S, Marvin JA, OlazarriFA. Weaning from mechanical

Heimbach DM.Treatment of postextubation ventilation in pediatricintensive care patients.

stridor in a pediatric patientwith burns: the role Intensive Care Med1998;24(10):1070-1075.

of heliox. J Burn Care Rehabil1990;11(4):337- 68. Baumeister BL, el-Khatib M, Smith PG,

339. Blumer JL.Evaluation of predictors of weaning

58. Kemper KJ, Ritz RH, Benson MS, Bishop from mechanicalventilation in pediatric

MS. Helium-oxygen mixture in the treatment of patients.PediatrPulmonol1997;24(5):344-352.

postextubationstridor in pediatric trauma 69. Khan N, Brown A, Venkataraman ST.

patients. Crit Care Med 1991;19(3):356-359. Predictors of extubationsuccess and failure in

59. Jaber S, Carlucci A, Boussarsar M, Fodil R, mechanically ventilatedinfants and children.

PigeotJ,Maggiore S, et al. Helium-oxygen in the Crit Care Med 1996; 24(9):1568-1579.

postextubationperiod decreases inspiratory 70. Kurachek SC, Newth CJ, Quasney MW,

effort. Am J RespirCrit Care Med Rice T,Sachdeva RC, Patel NR, et al.

2001;164(4):633-637. Extubation failure in pediatricintensive care: a

60. Epstein SK. Endotracheal extubation. Respir multiple-center study of riskfactors and

Care ClinN Am 2000;6(2):321-360.

outcomes. Critical Care to discontinue mechanicalventilation. The

Medicine2003;31(11):2657-2664. Spanish Lung Failure CollaborativeGroup. Am

71. Allatar, MH, Bhola M, Weiss M, Dallal O, J RespirCrit Care Med 1999;159(2):512-518.

MuraskasJK. The micropreemies: how early 80. Vallverdu I, Calaf N, Subirana M, Net A,

could they be extubated?Pediatric Research Benito S,Mancebo J. Clinical characteristics,

2001;49:360A. respiratory functionalparameters, and outcome

72. Sillos EM, Veber M, Schulman M, Krauss of a two-hour T-piecetrial in patients weaning

AN, AuldPA. Characteristics associated with from mechanical ventilation. Am J RespirCrit

successful weaningin ventilator-dependent Care Med 1998;158(6):1855-1862.

preterm infants. Am J Perinatol1992; 9(5- 81. Ely EW, Baker AM, Evans GW, Haponik

6):374-377. EF. Theprognostic significance of passing a

73. Veness-Meehan K, Richter S, Davis JM. daily screen ofweaning parameters. Intensive

Pulmonaryfunction testing prior to extubation in Care Med1999;25(6):581-587.

infants with respiratorydistress 82. Rusconi F, Castagneto M, Gagliardi L, Leo

syndrome.PediatrPulmonol1990;9(1):2-6. G, PellegattaA, Porta N, et al. Reference values

74. Berman LS, Fox WW, Raphaely RC, for respiratoryrate in the first 3 years of life.

Downes JJ Jr.Optimum levels of CPAP for Pediatrics1994;94(3):350-355.

tracheal extubation ofnewborn infants. J Pediatr 83. Bellemare F, Grassino A. Effect of pressure

1976;89(1):109-112. and timingof contraction on human diaphragm

75. Kim EH, Boutwell WC. Successful direct fatigue. J ApplPhysiol 1982;53(5):1190-1195.

extubationof very low birthweight infants from 84. Jubran A, Tobin MJ. Passive mechanics of

low intermittentmandatory ventilation rate. lung andchest wall in patients who failed or

Pediatrics 1987; 80(3):409-414. Erratum in: succeeded in trialsof weaning. Am J RespirCrit

Pediatrics 1987;80(6):948. Care Med1997;155(3):916-921.

76. Leitch EA, Moran JL, Grealy B. Weaning 85. Roussos C, Macklem PT. The respiratory

and extubationin the intensive care unit: clinical muscles. NEngl J Med 1982;307(13):786-797.

or index-drivenapproach? Intensive Care Med 86. Sahn SA, Lakshminarayan S. Bedside

1996;22(8):752-759. criteria for discontinuationof mechanical

77. Farias JA, Retta A, Alia I, Olazarri F, ventilation. Chest1973;63(6):1002-1005.

Esteban A, GolubickiA, et al. A comparison of 87. Hess D. Measurement of maximal

two methods to performa breathing trial before inspiratory pressure:a call for standardization

extubation in pediatric intensivecare patients. (editorial). Respir Care1989;34(10):857-559.

Intensive Care Med2001;27(10):1649-1654. 88. Marini JJ, Smith TC, Lamb V. Estimation of

78. Esteban A, Alia I, Gordo F, Fernandez R, inspiratorymuscle strength in mechanically

Solsona JF,Vallverdu I, et al. Extubation ventilated patients:the measurement of maximal

outcome after spontaneousbreathing trials with inspiratory pressure. JCrit Care 1986;1(1):32-

T-tube or pressure supportventilation. The 38.

Spanish Lung Failure CollaborativeGroup. Am 89. Belani KG, Gilmour IJ, McComb C,

J RespirCrit Care Med 1997;156(2 Pt1):459- Williams A,Thompson TR.

465. Erratum in: Am J RespirCrit Care Preextubationventilatory measurementsin

Med1997;156(6):2028. newborns and infants.

79. Esteban A, Alia I, Tobin MJ, Gil A, Gordo F, AnesthAnalg1980;59(7):467-472.

VallverduI, et al. Effect of spontaneous

breathing trial durationon outcome of attempts

90. Yang KL, Tobin MJ. A prospective study of 100. Levy MM, Miyasaki A, Langston D. Work

indexespredicting the outcome of trials of of breathingas a weaning parameter in

weaning from mechanicalventilation. N Engl J mechanically ventilatedpatients. Chest

Med1991;324(21):1445-1450. 1995;108(4):1018-1020.

91. Martin L, Bratton S, Walker L. Principles 101. Kirton OC, DeHaven CB, Morgan JP,

and practiceof respiratory support and Windsor J,Civetta JM. Elevated imposed work

mechanical ventilation. In:Rogers MC, editor. of breathing masqueradingas ventilator weaning

Textbook of pediatric intensivecare, 3rd ed. intolerance. Chest1995;108(4):1021-1025.

Baltimore: Williams & Williams; 1996. 102. Shikora SA, Bistrian OR, Borlase BC,

92. Bendixen HH, Egbert LD, Hedly-White J, et Blackburn GL,Stone MD, Benotti PN. Work of

al. Managementof patients undergoing breathing: reliablepredictor of weaning and

prolonged artificialventilation.Respir Care extubation. Crit Care Med1990;18(2):157-162.

1965;10:149-153. 103. Harpin RP, Baker JP, Downer JP, Whitwell

93. Aubier M, Murciano D, Lecocguic Y, Viires J, GallacherWN. Correlation of the oxygen cost

N, ParienteR. Bilateral phrenic stimulation: a of breathing andlength of weaning from

simple techniqueto assess diaphragmatic fatigue mechanical ventilation. CritCare Med

in humans. JApplPhysiol 1985;58(1):58-64. 1987;15(9):807-812.

94. Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. Respiratory 104. Shikora SA, Benotti PN, Johannigman JA.

muscle dysfunctionin mechanically-ventilated The oxygencost of breathing may predict

patients. Mol CellBiochem 1998;179(1-2):87- weaning from mechanicalventilation better than

98. the respiratory rate to tidalvolume ratio. Arch

95. Thiagarajan RR, Bratton SL, Martin LD, Surg 1994;129(3):269-274.

Brogan TV,Taylor D. Predictors of successful 105. Tahvanainen J, Salmenpera M, Nikki P.

extubation in children.Am J RespirCrit Care Extubationcriteria after weaning from

Med 1999;160(5 Pt1):1562-1566. intermittent mandatoryventilation and

96. Peters RM, Hilberman M, Hogan JS, continuous positive airway pressure.Crit Care

Crawford DA.Objective indications for Med 1983;11(9):702-707.

respiratory therapy in posttraumaand 106. Hubble CL, Gentile MA, Tripp DS, Craig

postoperative patients. Am J DM, MelionesJN, Cheifetz IM. Deadspace to

Surg1972;124(2):262-269. tidal volumeratio predicts successful extubation

97. Lee KH, Hui LP, Chan TB, Tan WC, Lim in infants and children.Crit Care Med

TK. Rapidshallow breathing (frequency-tidal 2000;28(6):2034-2040.

volume ratio) didnot predict extubation 107. Capdevila XJ, Perrigault PF, Perey PJ,

outcome. Chest1994;105(2):540-543. Roustan JPA,d’Athis F. Occlusion pressure and

98. Krieger BP, Isber J, Breitenbucher A, its ratio to maximuminspiratory pressure are

Throop G, ErshowskyP. Serial measurements of useful predictors for successfulextubation

the rapid-shallowbreathingindex as a predictor following T-piece weaning trial.

of weaning outcome inelderly medical patients. Chest1995;108(2):482-489.

Chest 1997;112(4):1029-1034. 108. Montgomery AB, Holle RH, Neagley SR,

99. Lewis WD, Chwals W, Benotti PN, Pierson DJ,Schoene RB. Prediction of

Lakshman K, O’Donnell C, Blackburn GL, successful ventilator weaningusing airway

Bistrian BR. Bedside assessmentof the work of occlusion pressure and hypercapnicchallenge.

breathing. Crit Care Med1988;16(2):117-122. Chest 1987;91(4):496-499.

109. Gandia F, Blanco J. Evaluation of indexes 119. Harel Y, Vardi A, Quigley R, Brink LW,

predictingthe outcome of ventilator weaning Manning SC,Carmody TJ, Levin DL.

and value of addingsupplemental inspiratory Extubation failure due to postextubationstridor

load. Intensive Care Med1992;18(6):327-333. is better correlated with neurologicimpairment

110. Gillespie LM, White SD, Sinha SK, Donn than with upper airway lesions in criticallyill

SM. Usefulnessof the minute ventilation test in pediatric patients. Int J

predicting successfulextubation in newborn PediatrOtorhinolaryngol1997;39(2):147-158.

infants: a randomizedcontrolled trial. J Perinatol 120. Coplin WM, Pierson DJ, Cooley KD,

2003;23(3):205-207. Newell DW,Rubenfeld GD. Implications of

111. Smina M, Salam A, Khamiees M, Gada P, extubation delay inbrain-injured patients

Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Cough meeting standard weaning criteria.Am J

peak flows and extubationoutcomes. Chest RespirCrit Care Med 2000;161(5):1530-1536.

2003;124(1):262-268. Bach JR, Saporito LR. 121. Khamiees M, Raju P, DeGirolamo A,

Criteria for extubation and tracheostomytube Amoateng-AdjepongY, Manthous CA.

removal for patients with ventilator failure: a Predictors of extubation outcomein patients who

different approach to weaning. have successfully completed aspontaneous

Chest1996;110(6):1566-1571. breathing trial. Chest 2001;120(4):1262-1270.

113. Martinez A, Seymour C, Nam M. Minute 122. Deem S, Bishop MJ. Evaluation and

ventilationrecovery time: a predictor of management ofthe difficult airway.Crit Care

extubation outcome.Chest 2003;123(4):1214- Clin 1995;11(1):1-27.

1221. 123. American Society of Anesthesiologists.

114. Bruton A. A pilot study to investigate any Practice guidelinesfor management of the

relationshipbetween sustained maximal difficult airway: an updatedreport by the

inspiratory pressure andextubation outcome. American Society of AnesthesiologistsTask

Heart Lung 2002;31(2):141-149. Force on Management of the Difficult

115. Balsan MJ, Jones JG, Watchko JF, Guthrie Airway.Anesthesiology 2003;98(5):1269-1277.

RD. Measurementsof pulmonary mechanics Erratum inAnesthesiology 2004;101(2):565.

prior to the electiveextubation of neonates. 124. Cork R, Monk JE. Management of a

PediatrPulmonol1990;9(4):238-243. suspected and unsuspecteddifficult

116. Davis PG, Henderson-Smart DJ. laryngoscopy with the laryngealmask airway. J

Extubation from lowrateintermittent positive ClinAnesth 1992;4(3):230-234.

airways pressure versus extubationafter a trial 125. Van Boven MJ, Lengele B, Fraselle B,

of endotracheal continuous positiveairways Butera G, VeyckemansF. Unexpected difficult

pressure in intubated preterm infants.Cochrane tracheal reintubationafter thyroglossal duct

Database Syst Rev 2001;(4):CD001078. surgery: functional imbalanceaggravated by the

117. Zeggwagh AA, Abouqal R, Madani N, presence of a hematoma. AnesthAnalg

Zekraoui A,Kerkeb O. Weaning from 1996;82(2):423-425.

mechanical ventilation: amodel for extubation. 126. Mort TC. Extubating the difficult airway:

Intensive Care Med1999;25(10):1077-1083. determiningthe odds of failure: be alert to the

118. Redmond JM, Greene PS, Goldsborough signs that flag a managementchallenge. J

MA,Cameron DE, Stuart RS, Sussman MS, et CritIlln 2003;18(4):177-184.

al. Neurologicinjury in cardiac surgical patients 127. Loudermilk EP, Hartmannsgruber M,

with a history ofstroke. Ann ThoracSurg Stoltzfus DP,Langevin PB. A prospective study

1996;61(1):42-47. of the safety of trachealextubation using a

pediatric airway exchangecatheter for patients 138. Sandhu RS, Pasquale MD, Miller K,

with a known difficult airway.Chest Wasser TE. Measurementof endotracheal tube

1997;111(6):1660-1665. cuff leak to predict postextubationstridor and

128. Hartmannsgruber MW, Loudermilk E, need for reintubation. J AmCollSurg

Stoltzfus D.Prolonged use of a cook airway 2000;190(6):682-687.

exchange catheter obviatedthe need for 139. Engoren M. Evaluation of the cuff-leak test

postoperative tracheostomy in anadult patient. J in a cardiacsurgery population. Chest

ClinAnesth 1997;9(6):496-498. 1999;116(4):1029-1031.

129. Hartmannsgruber MW, Rosenbaum SH. 140. Kemper KJ, Ritz RH, Benson MS, Bishop

Safer endotrachealtube exchange technique MS. Helium-oxygen mixture in the treatment of

(letter). Anesthesiology1998;88(6):1683. postextubationstridor in pediatric trauma

130. Davis S, Worley S, Mee RB, Harrison AM. patients. Critical Care Med1991;19(3):356-359.

Factors associatedwith early extubation after 141. Adderley RJ, Mullins GC. When to

cardiac surgery inyoung children. PediatrCrit extubate the crouppatient: the “leak” test. Can J

Care Med 2004;5(1):63-68. Anaesth 1987;34(3 Pt1):304-306.

131. Venkataraman ST, Khan N, Brown A. 142. Seid AB, Godin MS, Pransky SM, Kearns

Validation ofpredictors of extubation success DB, PetersonBM. The prognostic value of

and failure in mechanicallyventilated infants endotracheal tube-airleak following tracheal

and children. Crit Care Med2000;28(8):2991- surgery in children. Arch Oto- laryngol Head

2996. Neck Surg 1991;117(8):880-882.

132. Fisher MM, Raper RF. The ‘cuff-leak’ test 143. Morganroth ML, Morganroth JL, Nett LM,

for extubation.Anaesthesia 1992;47(1):10-12. Petty TL.Criteria for weaning from prolonged

133. Potgieter PD, Hammond JM. “Cuff” test mechanical ventilation.Arch Intern Med

for safe extubationfollowing laryngeal edema 1984;144(5):1012-1016.

(letter). Crit CareMed 1988;16(8):818. 144. Clochesy JM, Daly BJ, Montenegro HD.

134. De Bast Y, De Backer D, Moraine JJ, Weaningchronically critically ill adults from

Lemaire M, VandenborghtC, Vincent JL. The mechanical ventilator support: a descriptive

cuff leak test to predictfailure of extubation for study. Am J Crit Care1995;4(2):93-99.

laryngeal edema. IntensiveCare Med 145. Biery DR, Marks JD, Schapera A, Autry

2002;28(9):1267-1272. M,Schlobohm RM, Katz JA. Factors affecting

135. Miller RL, Cole RP. Association between perioperativepulmonary function in acute

reduced cuffleak volume and postextubation respiratory failure.Chest 1990;98(6):1455-1462.

stridor. Chest1996;110(4):1035-1040. 146. Hammond MD, Bauer KA, Sharp JT,

136. Jaber S, Chanques G, Matecki S, Rocha RD. Respiratorymuscle strength in

Ramonatxo M,Vergne C, Souche B, et al. Post- congestive heart failure.Chest 1990;98(5):1091-

extubation stridor inintensive care unit patients: 1094.

risk factors evaluation andimportance of the 147. Rothaar RC. Epstein SK. Extubation

cuff-leak test. Intensive Care failure: magnitudeof the problem, impact on

Med2003;29(1):69-74. outcomes, and prevention.CurrOpinCrit Care

137. Marik PE. The cuff-leak test as a predictor 2003;9(1):59-66.

of postextubationstridor: a prospective study. 148. Sapijaszko MJ, Brant R, Sandham D,

Respir Care1996;41(6):509-511. Berthiaume Y.Nonrespiratory predictor of

mechanical ventilation dependencyin intensive

care unit patients. Crit Care 159. Lyons KA, Brilli RJ, Wieman RA, Jacobs

Med1996;24(4):601-607. BR. Continuationof transpyloric feeding during

149. Smith IE, Shneerson JM. A progressive weaning of mechanicalventilation and tracheal

care programmefor prolonged ventilatory extubation in children:a randomized controlled

failure: analysis ofoutcome. Br J Anaesth trial. JPEN J ParenterEnteral Nutr

1995;75(4):399-404. 2002;26(3):209-213.

150. Scheinhorn DJ, Hassenpflug M, Artinian 160. American Academy of Pediatrics

BM, LaBreeL, Catlin JL. Predictors of weaning Committee onDrugs: Guidelines for monitoring

after 6 weeks ofmechanical ventilation. Chest and management ofpediatric patients during and

1995;107(2):500-505. after sedation for diagnosticand therapeutic

151. Cerra FB. Hypermetabolism, organ failure procedures. Pediatrics 1992;89(6 Pt1):1110

andmetabolic support. Surgery 1987;101(1):1- -1115.

14. 161. Gefke K, Andersen LW, Friesel E.

152. Aubier M, Murciano D, Lecocguic Y, Lidocaine given intravenouslyas a suppressant

Viires N,Jacquens Y, Squara P, Pariente R. of cough and laryngospasmin connection with

Effect of hypophosphatemiaon diaphragmatic extubation after

contractility in patientswith acute respiratory tonsillectomy.ActaAnaesthesiolScand

failure. N Engl J Med1985;313(7):420-424. 1983;27(2):111-112.

153. Aubier M, Viires N, Piquet J, Murciano D, 162. Staffel JG, Weissler MC, Tyler EP, Drake

Blanchet F,Marty C, Gherardi R, Pariente R. AF. The preventionof postoperative stridor and

Effects of hypocalcemiaon diaphragmatic laryngospasm withtopical lidocaine. Arch

strength generation. J ApplPhysiol Otolaryngol Head Neck

1985;58(7):2054-2061. Surg1991;117(10):1123-1128.

154. Pingleton SK, Harmon GS. Nutritional 163. Markovitz BP, Randolph AG.

management inacute respiratory failure.JAMA Corticosteroids for theprevention and treatment

1987;257(22):3094-3099. of postextubation stridor inneonates, children

155. Lewis MI, Sieck GC, Fournier M, et al. and adults. Cochrane Database SystRev 2000;

The effect ofnutritional deprivation of (2):CD001000.

diaphragm contractility andmuscle fiber size. J 164. Freezer N, Butt W, Phelan P. Steroids in

ApplPhysiol 1986;60(2):596-603. croup: do theyincrease the incidence of

156. Doekel RC Jr, Zwillich C, Scoggin CH, successful extubation?Anaesth Intensive Care

Kryger M,Weil JV. Clinical semi-starvation: 1990;18(2):224-228.

depression of hypoxicventilatory response. N 165. Tibballs J, Shann FA, Landau LI. Placebo-

Engl J Med1976;295(7):358-361. controlledtrial of prednisolone in children

157. Larca L, Greenbaum DM. Effectiveness of intubated for croup.Lancet

intensivenutritional regimes in patients who fail 1992;340(8822):745-748.

to wean frommechanical ventilation. Crit Care 166. Steer PA, Henderson-Smart DJ. Caffeine

Med1982;10(5):297-300. versus theophyllinefor apnea in preterm infants.

158. Bassili HR, Deitel M. Effect of nutritional CochraneDatabase Syst Rev 2000;

support onweaning patients off mechanical (2):CD000273.

ventilators. JPEN JParenter Enteral Nutr 167. Henderson-Smart DJ, Davis PG.

1981;5(2):161-163. Prophylacticmethylxanthines for extubation in

preterm infants.Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2003;(1):CD000139.

168. Listello D, Sessler CN. Unplanned noninvasive positive pressureventilatory support

extubation: clinicalpredictors for reintubation. in non-COPD patients with acuterespiratory

Chest 1994;105(5):1496-1503. insufficiency after early extubation.

169. Epstein SK. Etiology of extubation failure IntensiveCare Med 1999;25(12):1374-1380.

and the predictivevalue of the rapid shallow 179. Davies MW, Davis PG. Nebulized

breathing index. AmJ RespirCrit Care Med racemicepinephrine for extubation of newborn

1995;152(2):545-549. infants.

170. Whelan J, Simpson SQ, Levy H. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;

Unplanned extubation:predictors of successful (1):CD000506.

termination of mechanicalventilatory support. 180. Liebler JM, Markin CJ. Fiberoptic

Chest 1994;105(6):1808-1812. bronchoscopy fordiagnosis and treatment.Crit

171. Tindol GA Jr, DiBenedetto RJ, Kosciuk L. Care Clin 2000;16(1):83-100.

Unplannedextubations. Chest 181. Walker P, Forte V. Failed extubation in the

1994;105(6):1804-1807. neonatal intensivecare unit. Ann

172. Vassal T, Anh NG, Gabillet JM, Guidet B, OtolRhinolLaryngol1993;102(7):489-495.

StaikowskyF, Offenstadt G. Prospective 182. Plummer AL, Gracey DR. Consensus

evaluation of self-extubationsin a medical conference onartificial airways in patients

intensive care unit. Intensive CareMed receiving mechanical ventilation.Chest

1993;19(6):340-342. 1989;96(1):178-180.

173. Franck LS, Vaughan B, Wallace J. 183. Maziak D, Meade M, Todd TR. The timing

Extubation andreintubation in the NICU: of tracheostomy:a systematic review. Chest

identifying opportunities toimprove care. 1998;114(2):605-609.

PediatrNurs 1992;18(3):267-270. 184. Garner JS. Hospital Infection Control

174. De Paoli AG, Davis PG, Faber B, Morley Practices AdvisoryCommittee, Centers for

CJ. Devicesand pressure sources for Disease Control and Prevention.Guidelines for

administration of nasal continuouspositive isolation precautions in hospitals.1-01-1996.

airway pressure (NCPAP) in pretermneonates. Available at www.cdc.gov.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev2002; 185. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

(4):CD002977. Guidelinesfor preventing the transmission of

175. Jiang JS, Kao SJ, Wang SN. Effect of early Mycobacterium tuberculosisin health-care

applicationof biphasic positive airway pressure facilities.MMWR43(RR13);1-132. Publication

on the outcome ofextubation in ventilator date 10/28/1994. Availableat www.cdc.gov.

weaning.Respirology1999;4(2):161-165. 186. Lange JH. SARS respiratory protection

176. Meyer TJ. Hill NS. Noninvasive positive (letter). CMAJ2003;169(6):541-542.

pressure ven-tilation to treat respiratory failure. 187. Ho PL, Tang XP, Seto WH. SARS: hospital

Ann Intern Med1994;120(9):760-770. infectioncontrol and admission strategies.

177. Keenan SP, Powers C, McCormack DG, Respirology 2003;8Suppl:S41-S45.

Block G.Noninvasive positive-pressure 188. Tablan OC. Anderson LJ. Besser R.

ventilation for postextubationrespiratory Bridges C. HajjehR.CDC. Healthcare Infection

distress: a randomized controlledtrial. JAMA Control Practices AdvisoryCommittee.

2002;287(24):3238-3244. Guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated

178. Kilger E, Briegel J, Haller M, Frey L, pneumonia, 2003: recommendations ofCDC and

Schelling G,Stoll C, et al. Effects of the Healthcare Infection Control

PracticesAdvisory Committee. MMWR Guideline or infectioncontrol in healthcare

Recommendations &Reports 2004;53(RR-3):1- personnel, 1998. Hospital InfectionControl

36. Practices Advisory Committee. InfectControl

189. Bolyard EA, Tablan OC, Williams WW, HospEpidemiol 1998;19(6):407-463. Erratumin

Pearson ML,Shapiro CN, Deitchmann SD. Infect Control HospEpidemiol 1998;19(7):493.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Intubacion EndotraquealDokument8 SeitenIntubacion EndotraquealRamackNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apoyo al soporte vital avanzado. SANT0208Von EverandApoyo al soporte vital avanzado. SANT0208Noch keine Bewertungen

- Protocolo Intubacion y Extubacion OrotraquealDokument26 SeitenProtocolo Intubacion y Extubacion OrotraquealJacquelin GómezNoch keine Bewertungen

- .Guía Prono VigilDokument7 Seiten.Guía Prono VigilCarol Molina VillarroelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ultrasonido pulmonar focalizado: Serie Ultrasonido focalizado en urgencias y cuidado críticoVon EverandUltrasonido pulmonar focalizado: Serie Ultrasonido focalizado en urgencias y cuidado críticoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retirada Asitencia RespDokument5 SeitenRetirada Asitencia Respmaria lucia cardonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Destreza clínica I: Biomicroscopía, tonometría, fondo de ojo y gonioscopíaVon EverandDestreza clínica I: Biomicroscopía, tonometría, fondo de ojo y gonioscopíaBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- 03.- Ventilación Mecánica en Pediatría (III), Retirada de LaDokument26 Seiten03.- Ventilación Mecánica en Pediatría (III), Retirada de LaFrancis LamedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terapia respiratoria pacientes críticosDokument11 SeitenTerapia respiratoria pacientes críticosLuis BazanNoch keine Bewertungen

- RCP EspecialDokument8 SeitenRCP EspecialFran ramos ortegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protocolo IpsDokument25 SeitenProtocolo IpsLaura S RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guías para El Manejo de La Vía Aérea Durante La Extubación Parte 2Dokument10 SeitenGuías para El Manejo de La Vía Aérea Durante La Extubación Parte 2Walter Espinoza CiertoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definición de Extubación EndotraquealDokument15 SeitenDefinición de Extubación EndotraquealJorge EliasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vía Aérea Capítulo 1 ROSEN S Edicion 10 2023Dokument62 SeitenVía Aérea Capítulo 1 ROSEN S Edicion 10 2023Citlaly Gpe. Hernandez SobrevillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SIR en UrgenciasDokument10 SeitenSIR en UrgenciasMacaRuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Airway Management in Patients With Burn Contractures ofDokument38 SeitenAirway Management in Patients With Burn Contractures ofLissethe HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- GPC VmniDokument31 SeitenGPC Vmnilewita.valeriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Extubación de La Vía Aérea DifícilDokument14 SeitenLa Extubación de La Vía Aérea Difícilsanjuandediosanestesia100% (6)

- Secuencia Rapida de IntubacionDokument9 SeitenSecuencia Rapida de IntubacionLuz Caroly Vergara UtriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anexo - Modalidades Ventilatorias Guillermo BugedoDokument10 SeitenAnexo - Modalidades Ventilatorias Guillermo Bugedofrancisca yañezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ventilacion Mecanica No Invasiva en AsmáticosDokument10 SeitenVentilacion Mecanica No Invasiva en Asmáticosapi-3765169Noch keine Bewertungen

- Facilitando La Via Aerea SAE 2020 PDFDokument24 SeitenFacilitando La Via Aerea SAE 2020 PDFYesicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATL 10ed Capitulo 2Dokument19 SeitenATL 10ed Capitulo 2esthelar.hidalgo1988Noch keine Bewertungen

- Covid 19 y Cuidados RespiratoriosDokument29 SeitenCovid 19 y Cuidados RespiratoriosLevi GabrielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desvinculación de La Ventilación MecánicaDokument17 SeitenDesvinculación de La Ventilación MecánicaGisela SotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2-Manejo de La Vía Aérea yDokument18 Seiten2-Manejo de La Vía Aérea yHugo FernandesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protocolo manejo médico Covid intensivo UCDokument8 SeitenProtocolo manejo médico Covid intensivo UCTaniamtz2024Noch keine Bewertungen

- 7 - Extubacion SeguraDokument44 Seiten7 - Extubacion SegurajohaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Libro Mvaa M4 T9 Extubacion VadDokument27 SeitenLibro Mvaa M4 T9 Extubacion VadVanesaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5Dokument4 Seiten5Joel Grageda RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2024 Extubation Antes y MejorDokument4 Seiten2024 Extubation Antes y MejorrealdasoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guía Snorkel Covid19 V5Dokument12 SeitenGuía Snorkel Covid19 V5LeslieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protocolo WeaningDokument19 SeitenProtocolo WeaningJavier Enrique Barrera PachecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trabajo Final Mariana BurgosDokument119 SeitenTrabajo Final Mariana Burgosmarianavburgos17Noch keine Bewertungen

- Examen 2021 Santa FeDokument11 SeitenExamen 2021 Santa FeMauricio Contreras ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capítulo - 12Dokument18 SeitenCapítulo - 12julissaj64Noch keine Bewertungen

- Vad Induccion Inhalatoria SX Lennox GastautDokument4 SeitenVad Induccion Inhalatoria SX Lennox Gastautjuajimenez55Noch keine Bewertungen

- Retiro de la ventilación mecánicaDokument8 SeitenRetiro de la ventilación mecánicaANGIE PAOLA GOMEZ ARISTIZABALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decanulación de TraqueotomíaDokument10 SeitenDecanulación de TraqueotomíaRocío Macarena Espina VásquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capitulo 6 Intubacion Orotraqueal SeguraDokument11 SeitenCapitulo 6 Intubacion Orotraqueal SeguraYili yiliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resumen Via AereaDokument5 SeitenResumen Via AereaLau FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protocolo Manejo de La VADokument14 SeitenProtocolo Manejo de La VAAlonso Marcelo Herrera VarasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluación Del Espacio Muerto Ajustado Al VolumenDokument11 SeitenEvaluación Del Espacio Muerto Ajustado Al VolumenjimmyivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Via Aerea en TraumaDokument4 SeitenVia Aerea en TraumaAriana ManzanarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intubación endotraqueal: procedimiento y cuidadosDokument19 SeitenIntubación endotraqueal: procedimiento y cuidadoskyuper coronadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ventilación Mecánica InvasivaDokument13 SeitenVentilación Mecánica InvasivaPatricia Cecilia Rossi DeganoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articulo Via Aerea Dificil1Dokument17 SeitenArticulo Via Aerea Dificil1LORGIA VILLCA NINANoch keine Bewertungen

- Guía Clínica Manejo de Insuficiencia Respiratoria Hipoxémica y Del SDRA en El Paciente Con COVID 19. v3Dokument17 SeitenGuía Clínica Manejo de Insuficiencia Respiratoria Hipoxémica y Del SDRA en El Paciente Con COVID 19. v3Camila Fernanda Rivera ArayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maniobras de Reclutamiento AlveolarDokument18 SeitenManiobras de Reclutamiento AlveolarLaura Fierro ValverdeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECMO en SDRA. Puntos Clave en La Indicación y en El Abordaje AsistencialDokument7 SeitenECMO en SDRA. Puntos Clave en La Indicación y en El Abordaje Asistencialjose luis iribarrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anestesia y CIRUGIA...Dokument10 SeitenAnestesia y CIRUGIA...Ana ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secu Intuba RápidaDokument22 SeitenSecu Intuba RápidaANGELICA MARIA DAZA RAMIREZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fisioterapia adultos COVID-19Dokument3 SeitenFisioterapia adultos COVID-19Luisa CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluación Primaria en TraumaDokument5 SeitenEvaluación Primaria en TraumaEdgar Honorio Echavarria RoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broncoscopia Intervencionista Tratamiento Cáncer PulmónDokument15 SeitenBroncoscopia Intervencionista Tratamiento Cáncer Pulmónjabm91266154Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anestesia para Correccion de Atresia Esofagica y FistulaDokument22 SeitenAnestesia para Correccion de Atresia Esofagica y FistulaPamela Jeri FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Copia de Retiro de La Ventilación Mecánica MED CRIT 2017Dokument8 SeitenCopia de Retiro de La Ventilación Mecánica MED CRIT 2017frankNoch keine Bewertungen

- Profesiograma M PDokument10 SeitenProfesiograma M PPachoo Delgadoo0% (1)

- Guia de QuemadurasDokument14 SeitenGuia de QuemadurasJunior VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epoc - Antonio RuizDokument49 SeitenEpoc - Antonio RuizLeo Ruiz EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- DEFINICIONESDokument4 SeitenDEFINICIONESAly JaimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aporte Individual - Farmacia Magistral - Edwin - BastidasDokument10 SeitenAporte Individual - Farmacia Magistral - Edwin - Bastidasamanditasan11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Seminarios de InfectoDokument91 SeitenSeminarios de InfectoRodrigoNoch keine Bewertungen

- OMEPRAZOLDokument4 SeitenOMEPRAZOLOtto Carballo100% (1)

- Signos de Exploración AbdominalDokument2 SeitenSignos de Exploración AbdominalMercedes RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gestiones comerciales gimnasio Marzo 2022Dokument2 SeitenGestiones comerciales gimnasio Marzo 2022ONE FITNESS CLUB BY REYESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defensoría del Pueblo pide atención urgente para La LibertadDokument2 SeitenDefensoría del Pueblo pide atención urgente para La LibertadIamJuanAxelNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Secreto Del Poder 09 PatipembasDokument54 SeitenEl Secreto Del Poder 09 PatipembasJuanRivero83% (12)

- Aporte de Liquidos y Electrolitos en El PacienteDokument17 SeitenAporte de Liquidos y Electrolitos en El Pacientemario_edlo6573Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cuidados de Enfermeria en La MenopausiaDokument5 SeitenCuidados de Enfermeria en La MenopausiaHilda Pisconte100% (2)

- Exudado Faríngeo 4IM3 FloresRodríguez-HernándezMedinaDokument24 SeitenExudado Faríngeo 4IM3 FloresRodríguez-HernándezMedinaAnalí FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revolucionario Sistema de Limpieza Interna: ¿Por Qué Desintoxicarse?Dokument4 SeitenRevolucionario Sistema de Limpieza Interna: ¿Por Qué Desintoxicarse?alfred2569Noch keine Bewertungen

- Autosocorro en EspeleologíaDokument59 SeitenAutosocorro en EspeleologíaÁlvaro Martínez Ferrín100% (4)

- Fármacos Que Ocasionan Efectos Adversos A Nivel HematológicoDokument7 SeitenFármacos Que Ocasionan Efectos Adversos A Nivel HematológicoYos GuerreroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 25 08 20 Comunicación L1 2°Dokument5 Seiten25 08 20 Comunicación L1 2°Charles David Delvalle MartínezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expo Micosis CutaneasDokument31 SeitenExpo Micosis CutaneasJoseSilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomía de la aorta abdominal y sus ramasDokument12 SeitenAnatomía de la aorta abdominal y sus ramasKristen Llaxacondor AlayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- XV. Enfermedades de La PleuraDokument14 SeitenXV. Enfermedades de La Pleuramauricio maestreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cadenas Musculares en La Columna CervicalDokument47 SeitenCadenas Musculares en La Columna CervicalDan Diaz Guerra0% (2)

- EVALUACIÓN DE LECTURA COMPLEMENTARIA4º BasicoDokument5 SeitenEVALUACIÓN DE LECTURA COMPLEMENTARIA4º Basicoclaudia moscosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monografia - SemiologiaDokument31 SeitenMonografia - SemiologiaAnabel ZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

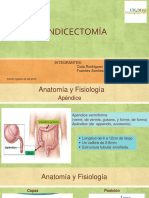

- APENDICECTOMÍADokument34 SeitenAPENDICECTOMÍAThanis Fuentes Senties100% (3)

- Generalidades de PediatriaDokument38 SeitenGeneralidades de PediatriaLuchitoGoicocheaTraucoNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Contaminación Ambiental para Quinto de PrimariaDokument4 SeitenLa Contaminación Ambiental para Quinto de PrimariaJill Halinna Terán Montalván75% (4)

- Antibioticos AntitumoralesDokument34 SeitenAntibioticos AntitumoralesBrandom VillanuevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aparato Reproductor FemeninoDokument2 SeitenAparato Reproductor FemeninoAna HedzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Módulo 1 Lectura 1221Dokument42 SeitenMódulo 1 Lectura 1221gestoriadel automotorlhNoch keine Bewertungen