Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ashkenazi 2007

Hochgeladen von

Ecaterina PozdircăCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ashkenazi 2007

Hochgeladen von

Ecaterina PozdircăCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review

Menstrual migraine: a review

of hormonal causes, prophylaxis

and treatment

1. Introduction Avi Ashkenazi† & Stephen Silberstein

2. Definitions Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Department of Neurology, Philadelphia, PA, USA

3. Epidemiology

Migraine in some women is associated with changes in sex hormone levels.

4. Pathogenesis Many women suffer from increased frequency of migraine around the

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

5. Management time of menses. Menstrual migraine (MM) may be more severe than

6. Expert opinion migraine that occurs at other times of the cycle. The pathogenesis of MM

is probably related to declining estrogen levels after exposure to high levels

of the hormone for several days. The acute treatment of MM is similar to

that of non-menstrually-related attacks. 5-HT1B/1D agonists (triptans), ergots,

NSAIDs, or combination analgesics may be used, although the response to

some drugs may not be as robust as that of non-menstrual attacks. Women

who suffer from frequent or debilitating MM attacks may benefit from

perimenstrual prophylaxis that can be either hormonal or non-hormonal.

Keywords: estrogen, menstrual migraine, prophylaxis, triptans

Expert Opin. Pharmachother. (2007) 8(11):1605-1613

For personal use only.

1. Intoduction

Migraine is a neurovascular disorder characterized by attacks of headache,

autonomic nervous system dysfunction and gastrointestinal symptoms [1]. Some

migraine patients experience an aura, typically manifesting as visual scotomas or

scintillations that precede the headache and last < 60 min. Less commonly, aura

symptoms may include transient tingling/numbness or dysphasia. Migraine is

a common disorder, with a prevalence of ∼ 12% in the adult population [2].

The prevalence of migraine peaks after 4 – 5 decades of life, when patients are

at their highest productivity [3]. The disease may have a significant impact on the

quality of life of the individual.

Epidemiologic data suggest a link between migraine and the female sex

hormones [4,5]. Before puberty, migraine prevalence is similar in boys and girls [6].

However, in adults migraine prevalence is three-times higher in women compared

with men (18% versus 6%). The peak incidence of migraine in women occurs at

adolescence [7]. Migraine prevalence decreases in women after the menopause,

although it remains higher than that of men [3].

Changes in headache pattern in women are probably related to changes in

estrogen levels [5]. Estrogen has diverse effects on brain function [8]. Estrogen

receptor-α (ER-α) is found mainly in the hypothalamus, whereas ER-β is more widely

distributed throughout the brain [9]. Hypothalamic endorphin levels correlate with

estradiol levels, suggesting a role for estrogen in the processing of pain perception [10].

In many women, migraine attacks are more frequent in the perimenstrual period,

and in some they occur exclusively during this time [11,12]. Migraine attacks

also appear to be more severe and less responsive to treatment compared with non

menstrually-related attacks [13].

In this review the epidemiology and pathogenesis of menstrual migraine (MM)

is discussed. Recent advances in the preventive and acute treatment of the disease

are also described.

10.1517/14656566.8.11.1605 © 2007 Informa UK Ltd ISSN 1465-6566 1605

Menstrual migraine: a review of hormonal causes, prophylaxis and treatment

2. Definitions The risk of an MA attack was also elevated during this period,

but not significantly so. Headaches were not more frequent

The International Headache Society (IHS) defines pure during the premenstrual period or around ovulation. In

menstrual migraine (PMM) as migraine attacks that occur another population-based study of 81 women with migraine,

exclusively between days -2 and +3 of the menstrual cycle Stewart et al. found an increased risk of headache in the

(where day 1 is the first day of menstruation) in at least two perimenstrual period for MO (OR: 2.04), and for tension-type

out of three menstrual cycles [14]. Menstrually-related migraine headache (OR: 1.67) but not for MA [11]. The highest risk

(MRM) is defined by the IHS as migraine attacks that occur at was observed in the first 2 days of menses.

the same time period as PMM in at least two out of three In a large population-based study from the Netherlands,

menstrual cycles and additionally may occur at other times of the prevalence of MM and MRM was assessed in a sample of

the cycle. The IHS classification emphasizes that MM attacks 1181 women [19]. The authors found that 8% of women had

are of migraine without aura (MO), since attacks of migraine MRM and 3% had PMM, as defined by the IHS. These

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

with aura (MA) do not seem to be related to menstruation. figures are lower than the ones reported in clinic-based

These definitions are included in the appendix of the IHS studies, possibly due to selection bias in the latter. Recently,

classification of headache disorders, meaning that more MacGregor et al. studied the occurrence of migraine in

scientific evidence is needed before they are formally accepted different phases of the menstrual cycle in 40 women with

as clinical entities. MO [20]. Migraine attacks were most likely to occur on

the first day of menstruation and on the day preceding it.

3. Epidemiology Ovulation was not associated with increased risk of having

a migraine attack.

When referring to the days of menstrual cycle in this Based on these data, it appears that migraine (without aura)

discussion, day 1 is defined as the first day of menstruation. is more frequent during the perimenstrual period. Pure

An increased risk of having a migraine attack (without aura) menstrual migraine, as defined by the IHS, is relatively

during the perimenstrual period has been shown in several uncommon, with a prevalence of 3% in one population-based

For personal use only.

studies [11,15-18]. However, these results need to be taken with study and 7 – 15% in clinic-based studies.

reservation: first, the definition of MM was not the same in

all studies; second, some of these studies were clinic-based, 4. Pathogenesis

causing a potential selection bias for patients with more severe

and disabling migraine compared with the general migraine The pathogenesis of MM is probably related to declining

patient population. estrogen levels after exposure to high levels of the hormone

MacGregor et al. studied the prevalence of MM in a for several days [20-22]. Estrogen, given premenstrually, delays

clinic-based study that included 55 women [15]. MM was the onset of migraine but not of menstruation [21,22]. In a

defined as migraine that occurs regularly on or between days study of 38 women with MO, migraine attack frequency and

-2 and +3 of the menstrual cycle and at no other time. urinary levels of estrone-3-glucuronide and pregnanediol-

The prevalence of MM in this study was 7.2% (all had MO). 3-glucuronide, metabolites of estradiol and progesterone,

A further 34% of women had an increased frequency of attacks respectively, were recorded over three menstrual cycles.

during the perimenstrual period. In another clinic-based study Migraine attacks were most likely to occur during the late

that included 155 women, migraine was found to be 1.7-times luteal and early follicular phases, when estrogen levels were

more likely to occur during the 2 days before menstruation falling or low, and least likely to occur when estrogen levels

and 2.5-times more likely to occur during the first 3 days of were rising [20].

menstruation, compared with other days of the cycle [12]. Estrogen and progesterone modulate receptor density and

Cupini et al. examined the association between sex-hormones neuronal activity of both serotonergic and opioid neurons in

related events and the occurrence of both MA and MO in the CNS [23,24]. The estrogen-sensitive changes in central opioid

268 women attending a headache clinic [16]. The prevalence of tone in women with MM may relate to headache genesis.

MM and of MRM (defined as in the above study [15]) in In an immunocytochemical study, ER-α was demonstrated in

women with MO was 13.6 and 56.4%, respectively. In women female rat trigeminal ganglia neurons in vitro [25]. Moreover,

with MA, the corresponding figures were significantly lower estrogen was shown in this study to alter the expression of genes

(3.8 and 33.3%). In another study, 20 women completed a coding for proteins that may be involved in inflammatory

3-month diary of migraine and menstrual periods [17]. Of pain (e.g., extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase).

these, 15% had MM and another 15% had MRM. All women In another animal study, mRNA levels of tryptophan

in both the MM and MRM groups had MO. Johannes et al. hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in serotonin synthesis,

investigated the relationship between headache occurrence and were found to be more than twice as high during the proestrus

phases of the menstrual cycle in a population-based study of (the high estrogen phase of the cycle) compared with the

74 women [18]. The risk of having an attack of MO was elevated diestrus (the low estrogen phase) [26]. Thus, cyclical changes in

during the first 3 days of menstruation (odds ratio (OR): 1.66). serotonin levels in trigeminal ganglia, which are associated

1606 Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11)

Ashkenazi & Silberstein

with changes in estrogen levels, may contribute to the migraine-related symptoms through cranial vasoconstriction

pathogenesis of MM. and inhibition of neurotransmission in the trigeminovascular

Prostaglandins (PGs), produced by the endometrium in system [33,34]. Several triptans have been studied as acute

response to estrogen and progesterone, sensitize nociceptors, treatments for MM [35].

promote neurogenic inflammation and cause uterine contrac-

tions, resulting in dysmenorrhea [27]. There is a high prevalence 5.1.1.1 Sumatriptan

of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) in women with MM. Sumatriptan, in both injectable and oral preparations, is the

Facchinetti et al. found that 64% of women with MM suffered most extensively-studied triptan for the acute treatment of

from PMS (compared with 33% of those with non menstrually- MM [36-40]. However, the definitions of MM in the different

related migraine) [28]. Prostoglandin E2 levels are increased studies were not the same (Table 1).

in women with MM during acute attack, supporting the In a placebo-controlled study, Facchinetti et al. assessed the

above epidemiologic data [29]. safety and efficacy of subcutaneous sumatriptan in 179 women

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

who treated two MM attacks [36]. At 2 h post-treatment,

5. Management sumatriptan injection resulted in a significantly higher rate of

headache relief compared with placebo (attack one: 73 versus

The management of MM includes pharmacologic treatment 31%; attack two: 81 versus 29%). Sumatriptan was also

for the acute attacks and, in some women, perimenstrual superior to placebo in alleviating nausea, photophobia and

prophylaxis in an attempt to decrease the frequency and phonophobia, and was well-tolerated. Solbach et al. analyzed

severity of attacks [5]. Perimenstrual prophylaxis may also the data from two controlled studies on the efficacy of

enhance the efficacy of acute migraine drugs. Hormonal sumatriptan 6 mg s.c. in the acute treatment of menstruation-

treatments are occasionally used to alter the duration of the associated migraine (MAM) [37]. At 1 h post treatment with

menstrual cycle, or to eliminate it altogether, thereby decreasing sumatriptan, 80% of women experienced pain relief, compared

MM frequency. with 19% of those who were given placebo. Dowson et al.

It has long been suggested that MM attacks are more severe evaluated the efficacy of oral sumatriptan 100 mg for both

For personal use only.

and disabling compared with non-menstrually related attacks. menstrual and non-menstrual migraine attacks in a placebo

Recent evidence supports this notion. Granella et al. enrolled controlled study of 93 women [38]. Sumatriptan treatment was

64 women with MRM in a 2-month prospective clinic-based associated with a 4-h headache relief in 67% of MM attacks

diary study. Perimenstrual attacks were significantly longer, (versus 33% for placebo). Response to sumatriptan was

caused greater work-related disability and were less responsive non-significantly lower for menstrual attacks compared with

to acute treatment compared with non-menstrual attacks [13]. that for non-menstrual attacks. In this study, however, the

MacGregor and Hackshaw found that perimenstrual migraine definition of MM was different from that recommended

attacks were 2.1 – 3.4 times more likely to be severe compared by the IHS. Nett et al. prospectively studied the effect of

with non-menstrual attacks [12]. Similar results were found in sumatriptan 50 and 100 mg tablets on MAM in a placebo-

a population-based study from the Netherlands [19]. Stewart controlled trial of 349 women [39]. Patients treated a single

et al. found, in a population-based prospective study, that MAM attack within 1 h of headache onset, when pain was

migraine headaches were more severe during the first 2 days of mild. At 2 h after treatment, 61 and 51% of women who

the menstrual cycle, but differences were small [11]. In a study used sumatriptan 100 and 50 mg, respectively, were pain free,

of 30 menstruating migraine women, MM attacks were compared with 29% of those who used placebo. As a

associated with more disability compared with non-menstrual comparison, in a study of 153 general migraine patients (both

attacks [30]. Silberstein et al., however, did not find a significant men and women), 83 patients treated a single migraine attack

difference in the response to a combination of acetaminophen, with oral sumatriptan 100 mg within 1 h of pain onset [41].

aspirin and caffeine (AAC) between patients with MM and Seventy-one percent of patients reported being pain free

those with migraine not associated with menses [31]. 2 h after treatment. The median time from pain onset to

sumatriptan use in this study was, however, somewhat shorter

5.1 Acute treatment than that in the study by Nett et al. (20 versus 30 min).

The acute treatment of MM is similar to that of non- In summary, sumatriptan in both injectable and oral forms

menstrually-related attacks [5]. Triptans (e.g., sumatriptan, is effective as acute treatment for MM. However, the response

zolmitriptan), ergots (e.g., dihydroergotamine), NSAIDs of MM attacks to sumatriptan may be weaker than that of

(e.g., naproxen sodium) or combination analgesics (e.g., AAC) non-menstrually related attacks.

are used (Table 1).

5.1.1.2 Zolmitriptan

5.1.1 Triptans Zolmitriptan has also been well-studied as an acute treatment

The 5-HT1B/1D agonists, known as triptans, have proven for MM [42-47]. Loder et al. evaluated the efficacy of oral

safe and effective in alleviating head pain and associated zolmitriptan for MAM in a prospective controlled study of

migraine symptoms [32]. The drugs presumably relieve 579 women [42]. The zolmitriptan dose range was 1.25 – 5 mg.

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11) 1607

Menstrual migraine: a review of hormonal causes, prophylaxis and treatment

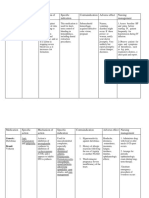

Table 1. Acute treatment of menstrual migraine.

Drug Dosage and Study design n* Results Reference

route of

administration

Sumatriptan 6 mg s.c. Prospective, randomized, PC 179 Drug superior to placebo [36]

6 mg s.c. Retrospective analysis of two 157 Drug superior to placebo; no [37]

PC trials difference between MRM and

non-MRM

100 mg PO Prospective, randomized PC 93 Response of MRM to drug ns [38]

crossover lower than that of non-MRM

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

50 or 100 mg PO Prospective, randomized PC 349 Drug superior to placebo [39]

Zolmitriptan 1, 2.5 or 5 mg Prospective, randomized PC 579 Drug superior to placebo but [42]

PO response rates low

2.5 mg PO Prospective, randomized PC 334 Drug superior to placebo; [47]

response rates similar to those

reported for non-MM

1 – 2.5 mg PO Retrospective analysis of 530 Drug similarly effective for MRM [43]

eight PC trials and for non-MRM

2.5 mg PO Subset analysis of a PC trial 49 Response of MRM to drug ns [44]

lower than that of non-MRM

1 – 10 mg Subset analysis of a PC trial 999‡ Response of MRM to drug ns [45]

higher than that of non-MRM

For personal use only.

5 mg PO Open label 2058 Response of MRM to treatment [46]

similar to that of non-MRM

Rizatriptan 5 or 10 mg PO Retrospective analysis of two 335 Drug superior to placebo; [48]

PC trials efficacy similar for MRM and for

non-MRM

10 mg PO Retrospective analysis of 95 Drug superior to placebo; [49]

long-term data efficacy similar for MRM and for

non-MRM

Naratriptan 2.5 mg PO Prospective, randomized PC 229 Drug superior to placebo [50]

Almotriptan 12.5 mg PO Retrospective analysis of a 136 Almotriptan and zolmitriptan [51]

randomized comparative trial similarly superior to placebo

AAC (acetaminophen 2 tabs PO Retrospective analysis of 966 Drug superior to placebo; no [31]

250 mg, aspirin 250 mg, three PC trials difference between MRM and

caffeine 65 mg) non-MRM

Modified from: ASHKENAZI A, SILBERSTEIN SD: Curr. Headache Rep. (2006) 5:207-212.

*n = number of patients.

‡This is the total number of patients in the study. Number of patients with MRM was not provided.

AAC: Acetominpohen, asprin, caffeine; MRM: Menstrually-related migraine; ns: Not significant; PC: Placebo controlled; PO: Per os.

At 2 h post treatment, headache response was achieved in 2.5 mg in MM treatment [47]. A total of 67% of patients who

48% of zolmitriptan-treated attacks compared with 27% of used zolmitriptan had headache response, compared with 33%

placebo-treated attacks. Zolmitriptan was well tolerated, with of placebo-treated patients. These results are similar to efficacy

most adverse events being transient and of mild or moderate data with zolmitriptan for non-menstrual migraine. Schoenen

intensity. Although zolmitriptan showed efficacy in treating et al. reviewed the data from eight studies constituting the

MAM in this study, response rates were lower that those zolmitriptan clinical trial program [43]. Data for 530 women

reported in studies on the efficacy of the drug in migraine with MRM was analyzed. Headache response rate for

attacks of any type [43,44]. Placebo response rates in this MRM attacks was similar to that of non-MRM attacks

study were also low, suggesting that this study population (65% for both types of attacks with the zolmitriptan 2.5 mg

may have been more difficult to treat than those in other dose; 69 versus 64%, respectively, with the 5 mg dose).

studies. In another placebo-controlled study of 334 patients, Solomon et al. conducted a controlled trial to assess the

Tuchman et al. examined the efficacy of oral zolmitriptan efficacy of oral zolmitriptan 2.5 mg in the acute treatment

1608 Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11)

Ashkenazi & Silberstein

of migraine [44]. A subset analysis of the data for 49 women used for perimenstrual prophylaxis, drugs from the same

who had MAM showed a headache response rate of 56%, class, or an ergot, should not be used for acute migraine attacks

compared with 41% for placebo. The corresponding rates at that time; an NSAID would be an appropriate choice for

for non-MAM attacks were 63 and 33%. Different results acute treatment in these circumstances).

were obtained by Rapoport et al., who showed a slightly

higher headache response rate to zolmitriptan in women 5.2.1 Non-hormonal prophylaxis

with MRM compared with those with non-MRM (72 versus Drugs that have been used for MM prophylaxis include

67% with zolmitriptan 2.5 mg and 69 versus 64% with triptans, ergots and NSAID’s [52,53].

zolmitriptan 5 mg, respectively) [45]. In an open label long-term

study of oral zolmitriptan 5 mg, data from 31,579 migraine 5.2.1.1 Triptans

attacks experienced by 2058 patients were analyzed [46]. Several triptans have been studied as prophylactic treatment

Headache response rates were not affected by association of for MM, including sumatripan, naratriptan and frovatriptan.

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

migraine attacks with menstruation.

In summary, oral zolmitriptan appears to be effective and 5.2.1.1.1 Sumatriptan Newman et al. treated in an open

well-tolerated as an acute treatment for MM. Available data do label study 20 women migraineurs with oral sumatriptan

not show a significant difference in response to the drug (25 mg t.i.d.) perimenstrually (Table 2) [52]. Headache was

between MM and non-MM attacks. absent in 52% of treated cycles and significantly reduced

in severity in 42%.

5.1.1.3 Other triptans

There is little data on the efficacy of other triptans in the 5.2.1.1.2Naratriptan Naratriptan (1 or 2.5 mg b.i.d. for

treatment of MM. In two retrospective studies, rizatriptan 5 days) was evaluated in MRM prophylaxis in 206 women [53].

10 mg was found to be as effective for MM as it was for Naratriptan 1 mg treatment was associated with a significantly

non-MM attacks [48,49]. In a prospective study of 229 women, lower number of MRM attacks (2.0 versus 4.0) and MRM

naratriptan 2.5 mg was superior to placebo in relieving MM days (4.2 versus 7.0) compared with placebo. The 2.5 mg dose

For personal use only.

headache [50]. Allais et al. performed a retrospective comparative was not effective.

analysis of the efficacy of almotriptan 12.5 mg versus

zolmitriptan 2.5 mg in MM [51]. Both drugs were equally 5.2.1.1.3Frovatriptan Silberstein et al. evaluated the efficacy

effective for this indication. of frovatriptan (2.5 mg once or twice daily) in the prevention

of MRM in a placebo-controlled study of 546 women [54].

5.1.2 Dihydroergotamine Treatment was started 2 days before the anticipated onset

Although used clinically for acute MM attacks, no data from of MRM headache, and lasted for 6 days. The incidence of

controlled studies on the efficacy of dihydroergotamine in the MRM headache was 67, 52 and 41% for placebo, frovatriptan

acute treatment of MM are available. 2.5 mg once daily and frovatriptan 2.5 mg b.i.d., respectively.

5.1.3 Other analgesics 5.2.1.1.4 Zolmitriptan Tuchman and Emeribe evaluated the

Silberstein et al. looked at data from three randomized efficacy of oral zolmitriptan (2.5 mg twice or three times daily)

controlled trials to assess the efficacy of AAC combination in MM prevention in a placebo-controlled study of

for both MAM and non-MAM [31]. Of the 1220 patients, 244 women [55]. Zolmitriptan treatment was started 2 days

185 women treated a MAM attack and 781 treated a non-MAM prior to the expected day of menses and continued for a

attack. AAC was superior to placebo in providing headache total of 7 days. Zolmitriptan at both treatment regimens

relief for both types of attacks, with no significant difference was significantly superior to placebo in decreasing the

between the two types (headache response at 2 h post dose: frequency of MM attacks (proportion of patients with ≥ 50%

MAM 61%, non-MAM 58%; pain free at 2 h: 25 versus 21%, decrease in MM frequency: 59, 55 and 38% for

respectively). In this study, however, patients with incapacitating zolmitriptan 2.5 mg t.i.d., zolmitriptan 2.5 mg b.i.d. and

headaches were excluded, causing a potential selection bias. placebo, respectively).

5.2 Prophylactic treatment 5.2.1.2 NSAIDs

Short-term drug prophylaxis is given for several (usually 5 – 7) Naproxen sodium 550 mg b.i.d. given perimenstrually, was

days each month, beginning before the anticipated time of shown to be associated with a significant decrease in headache

menstrual headache, in an attempt to prevent menstrually- intensity, headache duration and the number of days with

related attacks. This may be achieved with either hormonal or headaches in a controlled study of 35 women with MM [56].

non-hormonal treatments (Table 2). When a woman uses a

perimenstrual migraine prophylaxis, drugs that do not interact 5.2.2 Hormonal prophylaxis

with the prophylactic medication should be used as acute Hormonal manipulation, usually with estrogen, may also

treatment for breakthrough attacks (e.g., when a triptan is be effective in the short-term prophylaxis of MM (Table 2).

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11) 1609

Menstrual migraine: a review of hormonal causes, prophylaxis and treatment

Table 2. Perimenstrual prophylaxis for migraine.

Drug Dosage and route Study design n* Results Reference

of administration

Sumatriptan 25 mg PO t.i.d. Open label 20 Headache absent in 52% of treated cycles and [52]

significantly reduced in 42%

Naratriptan 1 mg PO; 2.5 mg Randomized PC 206 Significantly lower number of MRM attacks with 1 mg; [53]

PO 2.5 mg dose not effective

Frovatriptan 2.5 mg PO qd or Randomized PC 546 Decrease in incidence of MRM attacks with both doses, [54]

b.i.d. more so with the b.i.d. regimen

Zolmitriptan 2.5 mg bid or t.i.d. Randomized PC 244 Decrease in frequency of MM attacks with both [55]

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

regimens

Naproxen 550 mg PO b.i.d. PC 35 Decreased headache intensity and duration [56]

sodium

Estradiol 1.5 mg, transdermal Randomized 20 Decreased frequency, severity and duration of MRM [57]

(gel) PC, cross-over

Estradiol 1.5 mg, transdermal Randomized PC 35 A 22% reduction in MM days when using the drug, but [59]

(gel) cross-over an increase in headache after cessation of treatment

*n = number of patients.

MM: Menstrual migraine; MRM: Menstrually-related migraine; PC; Placebo controlled; PO: Per os.

The transdermal estrogen preparation is convenient and 6. Expert opinion

effective. However, withdrawal headaches with cessation of

For personal use only.

treatment may occur. There is convincing evidence, both from epidemiologic data

and from basic science research, for the association between

5.2.2.1 Estrogens female sex-hormones and migraine. Changes in estrogen levels

Percutaneous estradiol gel (1.5 mg in 2.5 g gel), started that occur around the time of menses appear to trigger migraine

2 days before the menses and continued for 7 days, was attacks in susceptible women. There is still a debate on whether

associated with a reduction in frequency, severity and MM is a separate clinical entity or the same disease process

duration of MM [57]. These positive results were confirmed in as non-menstrual migraine with a propensity to occur at a

other trials [58]. Recently, MacGregor et al. examined the specific time. There is no specific biologic marker for MM

efficacy of estardiol (1.5 mg) gel in MM prevention in a that would distinguish it from non-menstrual migraine. More

placebo controlled study [59]. Women treated six cycles research is needed to address this question. Current data is

in a cross-over design. Gel was applied daily from the insufficient to support the hypothesis that MM is a separate

10th day after ovulation to the second day of menses. disease. MM attacks seem to be more severe and possibly

During the time of gel application, estradiol treatment less responsive to some migraine drugs, compared with

was associated with a 22% reduction in migraine days, non-menstrual attacks. This may be due to the effect of changes

compared with placebo. However, an increase in migraine in hormonal (most importantly estrogen) levels on cranial

in the estardiol group occurred during the 5 days nociception and does not prove that MM is fundamentally

following cessation of gel application, compared with the different from non menstrually-related migraine.

placebo group. Some clinical observations support common mechanisms

for both MM and non-MM:

5.2.2.2 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

• The symptomatology of both types of migraine is similar,

In few studies, the efficacy of gonadotropin-releasing hormone

with the exception of aura that does not seem to be associ-

(GnRH) agonists in MM prevention was examined, with

ated with MM.

inconsistent results. In one study, five women with severe

• Both types respond to the same classes of acute-treatment

MM were treated with the GnRH agonist leuprolide

drugs (e.g., triptans, ergots, NSAIDs).

acetate, alone and in combination with transdermal estrogen

• MM severity and frequency may decrease with the

and oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Both treatments

use of preventive drugs that are also effective in the

resulted in significant headache relief [60]. In another study

prevention of non-menstrual migraine (e.g., antidepressants,

of 21 women with migraine, treatment with the combination

anticonvulsants).

of GnRH agonist goserelin and transdermal estradiol,

was effective in migraine prevention, but goserelin alone Future research may help in finding more specific drugs

was not [61]. for MM treatment. This may be accomplished once the

1610 Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11)

Ashkenazi & Silberstein

exact mechanisms of the interactions between estrogen and for 5 – 7 days, starting 2 days before the anticipated headache

the trigeminal system are elucidated. Until then, the mainstay day) is effective for this purpose in the majority of women

of MM treatment will consist of drugs used for migraine at and is used by the authors as a first choice treatment, unless

any other time of the cycle. contraindicated. If this fails, a triptan (e.g., frovatriptan

When treating MM attacks, the general principles of acute 2.5 mg b.i.d. for 6 days, starting 2 days before the anticipated

migraine treatment should apply. The triptans are effective day of the headache) may be used. We use hormonal prophylaxis

in the acute treatment of MM and should be considered a (e.g., percutaneous estradiol) if the above drugs are contra-

first line treatment for this indication, although the response indicated or ineffective, or if the patient prefers it. Giving a

of MM to some triptans may not be as robust as that of 3-month cycle hormonal contraceptive (e.g., Seasonale®,

non-MM attacks. Other treatment options include NSAIDs Duramed Pharmaceuticals, [ethinyl estradiol 30 µg plus

and combination analgesics. There are no established guidelines levonorgestrel 0.15 mg]) may also be considered. This will

for the prophylactic treatment of MM and MRM. Women result in decreased frequency of menses and thereby of

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

who suffer from frequent or debilitating migraine attacks in menstrually-related migraine. This option may be particularly

the perimenstrual period should be considered for short-term appealing to women whose MM attacks are severe and

prophylaxis. An NSAID (e.g., naproxen sodium 550 mg t.i.d. difficult to treat.

Bibliography 8. MCEWEN BS, ALVES SE: Estrogen 16. CUPINI LM, MATTEIS M,

Papers of special note have been highlighted actions in the central nervous system. TROISI E, CALABRESI P,

as either of interest (•) or of considerable Endocr. Rev. (1999) 20:279-307. BERNARDI G, SILVESTRINI M:

interest (••) to readers. 9. RIGGS BL, HARTMANN LC: Selective Sex-hormone related events in migrainous

estrogen-receptor modulators-mechanisms females. A clinical comparative study

1. GOADSBY PJ, LIPTON RB,

of action and application to clinical between migraine with aura and migraine

FERRARI MD: Migraine-current

practice. N. Engl. J. Med. (2003) without aura. Cephalalgia (1995)

understanding and treatment.

15:140-144.

For personal use only.

N. Engl. J. Med. (2002) 346:257-270. 348:618-629.

•• A thorough review of migraine 10. STOMATI M, BERNARDI F, LUISI S 17. MACGREGOR EA, IGARASHI H,

mechanisms and management. et al.: Conjugated equine estrogens, estrone WILKINSON M: Headaches and

sulphate and estradiol valerate oral hormones: subjective versus objective

2. LIPTON RB, BIGAL M, DIAMOND M:

administration in ovariectomized rats: assessment. Headache Quart. (1997)

Migraine prevalence, disease burden and

effects on central and peripheral 8:126-136.

the need for preventive therapy. Neurology

(2007) 68:343-349. allopregnanolone and β-endorphin. 18. JOHANNES CB, LINET MS,

•• A large population-based study that Maturitas (2002) 43:195-206. STEWART WF, CELENTANO DD,

examines migraine prevalence and 11. STEWART WF, LIPTON RB, LIPTON RB, SZKLO M: Relationship

migraine-related disability in the US. CHEE E, SAWYER J, of headache to phase of the menstrual

SILBERSTEIN SD: Menstrual cycle cycle among young women: a daily

3. LIPTON RB, HAMELSKY SW,

and headache in a population sample diary study. Neurology (1995)

STEWART WF: Epidemiology and impact

of migraineurs. Neurology (2000) 45:1076-1082.

of headache. In: Wolff ’s Headache and Other

Head Pain. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, 55:1517-1523. 19. COUTURIER EG, BOMHOF MA,

Dalessio DJ (Eds), Oxford University Press, 12. MACGREGOR EA, HACKSHAW A: NEVEN AK, VAN DUIJN NP: Menstrual

New York (2001):85-107. Prevalence of migraine on each day of the migraine in a representative Dutch

natural menstrual cycle. Neurology (2004) population sample: prevalence, disability

4. SILBERSTEIN SD, MERRIAM G: Sex

63:351-353. and treatment. Cephalalgia (2003)

hormones and headache 1999 (menstrual

23:302-308.

migraine). Neurology (1999) 53:S3-S13. 13. GRANELLA F, SANCES G, ALLAIS G

• A well-designed population-based study

5. ASHKENAZI A, SILBERSTEIN SD: et al.: Characteristics of menstrual and

of menstrual migraine.

Hormone-related headache: nonmenstrual attacks in women with

menstrually related migraine referred 20. MACGREGOR EA, FRITH A, ELLIS J,

pathophysiology and treatment.

to headache centres. Cephalalgia (2004) ASPINALL L, HACKSHAW A: Incidence

CNS Drugs (2006) 20:125-141.

24:707-716. of migraine relative to menstrual cycle

6. ABU-AREFEH I, RUSSELL G: phases of rising and falling estrogen.

Prevalence of headache and migraine 14. HEADACHE CLASSIFICATION

Neurology (2006) 67:2154-2158.

in school children. BMJ (1994) COMMITTEE: The international

•• A well-designed study that examines the

309:765-769. classification of headache disorders,

association between migraine and sex

2nd Edition. Cephalalgia (2004) 24:1-160.

7. STEWART WF, LINET MS, hormone levels in women.

CELENTANO DD et al.: Age and 15. MACGREGOR EA, CHIA H,

21. SOMERVILLE BW: Estrogen-withdrawal

sex-specific incidence rates of migraine with VOHRAH RC, WILKINSON M:

migraine. I. Duration of exposure

and without visual aura. Am. J. Epidemiol. Migraine and menstruation: a pilot

required and attempted prophylaxis by

(1991) 34:1111-1120. study. Cephalalgia (1990) 10:305-310.

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11) 1611

Menstrual migraine: a review of hormonal causes, prophylaxis and treatment

premenstrual estrogen administration. 32. FERRARI MD, ROON KI, 41. SCHOLPP J, SCHELLENBERG R,

Neurology (1975) 25:239-244. LIPTON RB, GOADSBY PJ: Oral MOECKESCH B, BANIK N: Early

22. SOMERVILLE BW: The role of triptans (serotonin 5-HT1B/1D agonists) treatment of a migraine attack while pain

estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of in acute migraine treatment: a metaanalysis is still mild increases the efficacy of

menstrual migraine. Neurology (1972) of 53 trials. Lancet (2001) 358:1668-1675. sumatriptan. Cephalalgia (2004)

22:355-365. •• A comprehensive assessment of the 24:925-933.

efficacy of triptans in migraine treatment. 42. LODER E, SILBERSTEIN SD,

23. BIEGON A, RECHES A, SNYDER L,

MCEWEN BS: Serotonergic and 33. HUMPHREY PP, FENIUK W, ABU-SHAKRA S, MUELLER L,

noradrenergic receptors in the rat brain: PERREN MJ, BERESFORD IJ, SMITH T: Efficacy and tolerability

modulation by chronic exposure to SKINGLE M, WHALLEY ET: of oral zolmitriptan in menstrually

ovarian hormones. Life Sci. (1983) Serotonin and migraine. associated migraine: a randomized,

32:2015-2028. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. (1990) 600:587-598. prospective, parallel-group, double-blind,

placebo-controlled study. Headache (2004)

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

24. GENAZZANI AR, PETRAGLIA F, 34. MOSKOWITZ MA, CUTRER FM:

Sumatriptan: a receptor-targeted treatment 44:120-130.

VOLPE A, FACCHINETTI F: Estrogen

for migraine. Ann. Rev. Med. (1993) • A controlled study of the efficacy of

changes as a critical factor in modulation of

44:145-154. zolmitriptan in menstrual migraine.

central opioid tonus: possible correlations

with postmenopausal migraine. 35. MANNIX LK, FILES JA: 43. SCHOENEN J, SAWYER J: Zolmitriptan

Cephalalgia (1985) 2:211-214. The use of triptans in the (Zomig®, 311C90), a novel dual central

management of menstrual migraine. and peripheral 5-HT1B/1D agonist: an

25. PURI V, PURI S, SVOJANOVSKY SR

CNS Drugs (2005) 19:951-972. overview of efficacy. Cephalalgia (1997)

et al.: Effects of oestrogen on trigeminal

• A comprehensive review of the role 17:28-40.

ganglia in culture: implications for

hormonal effects on migraine. Cephalalgia of triptans in the treatment of 44. SOLOMON GD, CADY RK,

(2006) 26:33-42. menstrual migraine. KLAPPER JA, EARL NL, SAPER JR,

• An important study that shows how 36. FACCHINETTI F, BONELLIE G, RAMADAN NM: Clinical efficacy and

estrogen may affect the trigeminal system. KANGASNIEMI P, PASCUAL J, tolerability of 2.5 mg zolmitriptan for the

For personal use only.

SHUAIB A: The efficacy and safety of acute treatment of migraine. Neurology

26. BERMAN NE, PURI V,

subcutaneous sumatriptan in the acute (1997) 49:1219-1225.

CHANDRALA S et al.: Serotonin in

trigeminal ganglia of female rodents: treatment of menstrual migraine. The 45. RAPOPORT AM, RAMADAN NM,

relevance to menstrual migraine. Sumatriptan Menstrual Migraine ADELMAN JU et al.: Optimizing the dose

Headache (2006) 46:1230-1245. Study Group. Obstet. Gynecol. (1995) of zolmitriptan (Zomig, 311C90) for the

86:911-916. acute treatment of migraine: a multicenter,

27. BOYLE CA: Management of

• A controlled study that evaluated the double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose

menstrual migraine. Neurology (1999)

efficacy of sumatriptan in the treatment range-finding study. 017 Clinical Trial

53:S14-S18.

of menstrual migraine. Study Group. Neurology (1997)

28. FACCHINETTI F, NERI I, 49:1210-1218.

37. SOLBACH MP, WAYMER RS: Treatment

MARTIGNONI E, FIORONI L,

of menstruation-associated migraine 46. THE INTERNATIONAL 311C90

NAPPI G, GENAZZANI AR: The

headache with subcutaneous sumatriptan. LONG-TERM STUDY GROUP: The

association of menstrual migraine

Obstet. Gynecol. (1993) 82:769-772. long-term tolerability and efficacy of oral

with the premenstrual syndrome.

38. DOWSON AJ, MASSIOU H, zolmitriptan (Zomig, 311C90) in the acute

Cephalalgia (1993) 13:422-425.

AURORA SK: Managing migraine treatment of migraine. An international

29. NATTERO G, ALLAIS G, study. Headache (1998) 38:173-183.

headaches experienced by patients who

DELORENZO C et al.: Relevance

self-report with menstrually related 47. TUCHMAN M, HEE A,

of prostaglandins in true menstrual

migraine: a prospective, placebo-controlled EMERIBE U, SILBERSTEIN SD:

migraine. Headache (1989) 29:233-238.

study with oral sumatriptan. Oral zolmitriptan demonstrates high

30. DOWSON AJ, KILMINSTER SG, J. Headache Pain (2005) 6:81-87. efficacy and good tolerability in the

SALT R, CLARK M, BUNDY MJ: acute treatment of menstrual

39. NETT R, LANDY S, SHACKELFORD S,

Disability associated with headaches migraine. CNS Drugs (2006)

RICHARDSON MS, AMES M,

occurring inside and outside the 20:1019-1026.

LENER M: Pain-free efficacy after

menstrual period in those with migraine:

treatment with sumatriptan in the mild 48. SILBERSTEIN SD, MASSIOU H,

a general practice study. Headache (2005)

pain phase of menstrually associated LEJEUNNE C, PRATT LJ,

45:274-282.

migraine. Obstet. Gynecol. (2003) MCCARROLL KA, LINES CR:

31. SILBERSTEIN SD, ARMELLINO JJ, 102:835-842. Rizatriptan in the treatment of

HOFFMAN HD et al.: Treatment of menstrual migraine. Obstet. Gynecol.

40. SALONEN R, SAIERS J: Sumatriptan is

menstruation-associated migraine with (2000) 96:237-242.

effective in the treatment of menstrual

the nonprescription of acetaminophen,

migraine: a review of prospective studies 49. SILBERSTEIN SD, MASSIOU H,

aspirin, and caffeine: results from three

and retrospective analyses. Cephalalgia MCCARROLL KA, LINES CR:

randomized, placebo-controlled studies.

(1999) 19:16-19. Further evaluation of rizatriptan in

Clin. Ther. (1999) 21:475-491.

1612 Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11)

Ashkenazi & Silberstein

menstrual migraine: retrospective migraine. Neurology (2004) 60. MURRAY SC, MUSE KN: Effective

analysis of long-term data. Headache 63:261-269. treatment of severe menstrual migraine

(2002) 42:917-923. 55. TUCHMAN M, EMERIBE U: headaches with gonadotropin-releasing

50. MASSIOU H, JAMIN C, HINZELIN G, Zolmitriptan is effective and well tolerated hormone agonist and “add-back” therapy.

BIDAUT-MAZEL C: Efficacy of oral in both acute and prophylactic treatment of Fertil. Steril. (1997) 67:390-393.

naratriptan in the treatment of menstrually menstrual migraine. Neurology (2007) 61. MARTIN V, WERNKE S, MANDELL K

related migraine. Eur. J. Neurol. (2005) 68(Suppl. 1):A260-A261. et al.: Medical oophorectomy with and

12:774-781. 56. SANCES G, MARTIGNONI E, without estrogen add-back therapy in the

51. ALLAIS G, ACUTO G, FIORONI L, BLANDINI F, prevention of migraine headache.

CABARROCAS X, ESBRI R, FACCHINETTI F, NAPPI G: Naproxen J. Head Face Pain (2003) 43:309-321.

BENEDETTO C, BUSSONE G: sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis:

Efficacy and tolerability of almotriptan a double-blind placebo controlled study. Affiliation

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

versus zolmitriptan for the acute treatment Headache (1990) 30:705-709. Avi Ashkenazi†1 MD &

of menstrual migraine. Neurol. Sci. (2006) 57. DELIGNIÈRES B, VINCENS M, Stephen Silberstein2 MD FACP

27(Suppl. 2):S193-S197. MAUVAIS-JARVIS P, MAS JL, †Author for correspondence

1Assistant Professor of Neurology,

52. NEWMAN LC, LIPTON RB, LAY CL, TOUBOUL PJ, BOUSSER MG:

SOLOMON S: A pilot study of oral Prevention of menstrual migraine by Thomas Jefferson University,

sumatriptan as intermittent prophylaxis of percutaneous estradiol. BMJ (1986) Department of Neurology,

menstruation-related migraine. Neurology 293:1540. 111 South 11th Street, Suite #8130,

(1998) 51:307-309. 58. DENNERSTEIN L, MORSE C, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

53. NEWMAN LC, MANNIX LK, BURROWS G, OATS J, BROWN J, Tel: +1 215 955 2032; Fax: +1 215 955 2060;

LANDY SH et al.: Naratriptan as SMITH M: Menstrual migraine: a E-mail: avi.ashkenazi@jefferson.edu

2Professor of Neurology,

short-term prophylaxis for menstrually double-blind trial of percutaneous estradiol.

associated migraine: a randomized, Gynecol. Endocrinol. (1988) 2:113-120. Director, Jefferson Headache Center,

double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Thomas Jefferson University Hospital,

59 MACGREGOR EA, FRITH A, ELLIS J,

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

For personal use only.

Headache (2000) 41:248-256. ASPINALL L, HACKSHAW A: Prevention

54. SILBERSTEIN SD, ELKIND AH, of menstrual attacks of migraine – a

SCHREIBER C, KEYWOOD C: double-blind placebo-controlled crossover

Randomized trial of frovatriptan for the study. Neurology (2006) 67:2159-2163.

intermittent prevention of menstrual

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. (2007) 8(11) 1613

Expert Opin. Pharmacother. Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Pennsylvania on 07/13/13

For personal use only.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Menstrual Migrain Razutis 2015Dokument4 SeitenMenstrual Migrain Razutis 2015Fifi RohmatinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marcus 2001Dokument8 SeitenMarcus 2001Juliana Valentina CedeñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A14 2002febGallagherS58 73 2Dokument16 SeitenA14 2002febGallagherS58 73 2Zahra Ahmed AlzaherNoch keine Bewertungen

- ArticlesDokument71 SeitenArticlesMuhammad Obaid Ur RehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 Pharmacology of Balance and DizzinessDokument14 Seiten2013 Pharmacology of Balance and Dizzinessfono.jcbertolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacological MigraineDokument5 SeitenPharmacological MigraineSofia RomeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- ANSWERS Vol 24.4 - Headache.2018 PDFDokument40 SeitenANSWERS Vol 24.4 - Headache.2018 PDFmonica ortizNoch keine Bewertungen

- JNSK 08 00311Dokument5 SeitenJNSK 08 00311Ro KohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- MigraineDokument6 SeitenMigraineNatália CândidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prolonged Abuse of Vasograin Tablets: 10.5005/jp-Journals-10067-0014Dokument2 SeitenProlonged Abuse of Vasograin Tablets: 10.5005/jp-Journals-10067-0014Pratipal SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Levetiracetam in The Prophylaxis of Migraine With Aura: A 6-Month Open-Label StudyDokument5 SeitenLevetiracetam in The Prophylaxis of Migraine With Aura: A 6-Month Open-Label StudyDian ArdiansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- JOURNAL READING-Epilepsy-RidhaDokument22 SeitenJOURNAL READING-Epilepsy-RidhaUlul Azmi AdnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 - Antidepressants DrugsDokument27 Seiten3 - Antidepressants DrugsHadeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treatment of Migraine Attacks and Prevention of MiDokument40 SeitenTreatment of Migraine Attacks and Prevention of MiHemi Amalia AmirullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Case PresentationDokument26 SeitenPatient Case PresentationKathleen B BaldadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAiN SYnDrOmEs (Reviewer)Dokument19 SeitenPAiN SYnDrOmEs (Reviewer)Agum, Philip James P.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Myastheni Gravis Quick NotesDokument4 SeitenMyastheni Gravis Quick NotesLeamy ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ect CDokument3 SeitenEct Capi-354936399Noch keine Bewertungen

- Initial Dose: 50 MG Orally Once A Day Maintenan Ce Dose: 50 To 200 MG Orally Once A DayDokument2 SeitenInitial Dose: 50 MG Orally Once A Day Maintenan Ce Dose: 50 To 200 MG Orally Once A Dayunkown userNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0903CP Article1Dokument7 Seiten0903CP Article1Patricia Cavalcanti RibeiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Migrain Asam ValproatDokument5 SeitenJurnal Migrain Asam ValproatcynthiaramaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rle (NCM 116) CasesDokument12 SeitenRle (NCM 116) CasesLaurence ZernaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuropathic Pain: Mechanisms and Their Clinical ImplicationsDokument12 SeitenNeuropathic Pain: Mechanisms and Their Clinical Implicationsfahri azwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal RadaDokument3 SeitenJurnal RadaMuh Ridho AkbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epilepsy in Pregnancy.15Dokument12 SeitenEpilepsy in Pregnancy.15alexsr36Noch keine Bewertungen

- Content - 73 - 351 - Side Effects of Antidepressants An OverviewDokument9 SeitenContent - 73 - 351 - Side Effects of Antidepressants An OverviewAbraham TheodoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Role of Psychiatric Nurse IN Various Therapies: ObjectivesDokument30 Seiten1 Role of Psychiatric Nurse IN Various Therapies: ObjectivesChiragNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Triptans in The Management of Acute Migraine: A ReviewDokument7 SeitenRole of Triptans in The Management of Acute Migraine: A ReviewAndreas NatanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antidepressants PrintedDokument3 SeitenAntidepressants PrintedRahul Kumar DiwakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacology of AntidepressantsDokument28 SeitenPharmacology of Antidepressantsحيدر كريم سعيد حمزهNoch keine Bewertungen

- New England Journal of Medicine Volume 383 Issue 19 2020 (Doi 10.1056 - NEJMra1915327) Ropper, Allan H. Ashina, Messoud - MigraineDokument11 SeitenNew England Journal of Medicine Volume 383 Issue 19 2020 (Doi 10.1056 - NEJMra1915327) Ropper, Allan H. Ashina, Messoud - MigraineMarija Sekretarjova100% (1)

- Menopause Hormone Therapy Latest Developments and Clinical PracticeDokument9 SeitenMenopause Hormone Therapy Latest Developments and Clinical PracticeJuan FranciscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Traeger 2020Dokument19 SeitenTraeger 2020Alvaro StephensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anest Implication of PsikoaktifDokument5 SeitenAnest Implication of PsikoaktifjilieNoch keine Bewertungen

- 18.jaladi Himaja Battu Rakesh PDFDokument9 Seiten18.jaladi Himaja Battu Rakesh PDFFebby da costaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient: Alma Drug Mechanism of Action Indications Contraindication S Adverse Reactions Nursing Responsibilities Generic NameDokument5 SeitenPatient: Alma Drug Mechanism of Action Indications Contraindication S Adverse Reactions Nursing Responsibilities Generic NameAllisson BeckersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prophylaxis of Migraine Headache: The CaseDokument8 SeitenProphylaxis of Migraine Headache: The CaseRo KohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preventive Migraine TreatmentDokument20 SeitenPreventive Migraine TreatmentNatalia BahamonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Migraine Headaches in A Chronic Pain Patient: A Case ReportDokument5 SeitenManagement of Migraine Headaches in A Chronic Pain Patient: A Case Reporthenandwitafadilla28Noch keine Bewertungen

- Migraine and The Scope of HomeopathyDokument6 SeitenMigraine and The Scope of HomeopathyDiego RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- AntidepressantsDokument4 SeitenAntidepressantsSalman HabeebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug StudyDokument5 SeitenDrug StudyTRIXY MAE HORTILLANONoch keine Bewertungen

- Antidepressand Pain 2006Dokument7 SeitenAntidepressand Pain 2006Paulo MaurícioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migraine DiagnosisDokument7 SeitenMigraine DiagnosisMariaAmeliaGoldieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insomnia: Prevalence, Consequences and Effective Treatment: Supplement Sleep DisordersDokument8 SeitenInsomnia: Prevalence, Consequences and Effective Treatment: Supplement Sleep DisordersAlmas BilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hes 005 Session 12 SasDokument12 SeitenHes 005 Session 12 SasBread PartyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hes 005 Session 12 SasDokument12 SeitenHes 005 Session 12 SasJose Melmar Autida AutenticoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manejo de La Migraña en Adultos. Tratamiento FarmacologicoDokument19 SeitenManejo de La Migraña en Adultos. Tratamiento FarmacologicoGabriel Josué Alaña UrdanetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Option Overview: Neuropathic PainDokument3 SeitenAn Option Overview: Neuropathic PainAndi Tri SutrisnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clobazam As First Add On What Is The Evidence and Experience - Final Deck - 14 Feb 2023Dokument51 SeitenClobazam As First Add On What Is The Evidence and Experience - Final Deck - 14 Feb 2023veerraju tvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drugs and Acupuncture: The Energetic Impact of Antidepressant MedicationsDokument7 SeitenDrugs and Acupuncture: The Energetic Impact of Antidepressant Medicationspeter911x2134Noch keine Bewertungen

- NCM 61 Pharmacology - Digital Scrapbook-: By: Hannah Angelu S. Cabading Bsn2DDokument35 SeitenNCM 61 Pharmacology - Digital Scrapbook-: By: Hannah Angelu S. Cabading Bsn2DHannah Angelu CabadingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Study PsychDokument2 SeitenDrug Study PsychShannon CabfitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chronic Insomnia: Matt T. Bianchi, MD, PHDDokument6 SeitenChronic Insomnia: Matt T. Bianchi, MD, PHDAlex BorroelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moosi Depression PresentationDokument30 SeitenMoosi Depression Presentationfathima AlfasNoch keine Bewertungen

- AcetaminophenDokument1 SeiteAcetaminophenKristine YoungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specific ActionDokument3 SeitenSpecific Actionmoritashinobu2011Noch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Reading AminophyllineDokument76 SeitenJournal Reading AminophyllinePandhu Suprobo100% (1)

- Psychopharmacology in Psychopharmacology in Psychiatry PsychiatryDokument16 SeitenPsychopharmacology in Psychopharmacology in Psychiatry PsychiatryHasnain HyderNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0701 CB MigraineDokument4 Seiten0701 CB MigraineEcaterina PozdircăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Giraud2013 Obesity and MigraineDokument6 SeitenGiraud2013 Obesity and MigraineEcaterina PozdircăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accepted Manuscript: Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical SciencesDokument21 SeitenAccepted Manuscript: Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical SciencesEcaterina PozdircăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Menstrual Migraine: Therapeutic Approaches: E. Anne MacgregorDokument10 SeitenMenstrual Migraine: Therapeutic Approaches: E. Anne MacgregorEcaterina PozdircăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Celiac Disease Comprehensive Cascade Test AlgorithmDokument1 SeiteCeliac Disease Comprehensive Cascade Test Algorithmayub7walkerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amoebiasis NCPDokument3 SeitenAmoebiasis NCPRellie CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study 103Dokument8 SeitenCase Study 103Jonah MaasinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whitepaper Cohort of ConcernDokument4 SeitenWhitepaper Cohort of ConcernwoodsjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- #Spirochaetes & Mycoplasma#Dokument28 Seiten#Spirochaetes & Mycoplasma#Sarah PavuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dorset County Hospital NHS Foundation TrustDokument1 SeiteDorset County Hospital NHS Foundation TrustRika FitriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appolo AssignmentDokument13 SeitenAppolo AssignmentAparna R GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mission Urinalysis Strips InsertDokument1 SeiteMission Urinalysis Strips Insertquirmche70Noch keine Bewertungen

- Disease Impact 2Dokument31 SeitenDisease Impact 2Seed Rock ZooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sound TherapyDokument1 SeiteSound TherapyibedaflyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Documentary Requirements and Format of Simplified CSHPDokument1 SeiteDocumentary Requirements and Format of Simplified CSHPRhalf AbneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing 102 Med-Surg PerioperaDokument7 SeitenNursing 102 Med-Surg PerioperaKarla FralalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology SPMDokument17 SeitenBiology SPMbloptra18Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On IbuprofenDokument8 SeitenLiterature Review On Ibuprofenbujuj1tunag2100% (1)

- BC CancerDokument42 SeitenBC CancerIsal SparrowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life-Changed Self-Healing Series Ayurvedic Oil PullingDokument19 SeitenLife-Changed Self-Healing Series Ayurvedic Oil PullingReverend Michael Zarchian Amjoy100% (2)

- History Taking and MSE AIIMS PatnaDokument34 SeitenHistory Taking and MSE AIIMS PatnaShivendra Kumar100% (1)

- Kegawatan Pada Diare Dehidrasi BeratDokument40 SeitenKegawatan Pada Diare Dehidrasi BeratAkram BatjoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infochap10 12Dokument18 SeitenInfochap10 12Nareeza AbdullaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ob &gyDokument6 SeitenOb &gyThumz ThuminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Reading Radiologi EllaDokument44 SeitenJournal Reading Radiologi EllaElla Putri SaptariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apply Thinking Skilawefawefawefls To Multiple Choice QuestionsDokument2 SeitenApply Thinking Skilawefawefawefls To Multiple Choice Questionsseaturtles505Noch keine Bewertungen

- AutismAdvisoryPanelReport 2019Dokument64 SeitenAutismAdvisoryPanelReport 2019CityNewsTorontoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge Cumulative Rates ResortedDokument81 SeitenGe Cumulative Rates ResortedfishyfredNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subject: Field Observation Report: Pphi SindhDokument2 SeitenSubject: Field Observation Report: Pphi Sindhrafique512Noch keine Bewertungen

- Titus Andronicus and PTSDDokument12 SeitenTitus Andronicus and PTSDapi-375917497Noch keine Bewertungen

- PMLS 2 LEC Module 3Dokument8 SeitenPMLS 2 LEC Module 3Peach DaquiriNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 PharmacodynamicsDokument51 Seiten2 PharmacodynamicsKriziaoumo P. Orpia100% (1)

- Hostel Prospectus BookletDokument12 SeitenHostel Prospectus BookletsansharmajsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Read and Choose The Correct Answer From The Box Below.: Boys GirlsDokument1 SeiteRead and Choose The Correct Answer From The Box Below.: Boys GirlsjekjekNoch keine Bewertungen