Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Effects of Music Therapy in Patients Undergoing Septorhinoplasty Surgery Under General Anesthesia. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology.

Hochgeladen von

Yamii AlmeidäCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Effects of Music Therapy in Patients Undergoing Septorhinoplasty Surgery Under General Anesthesia. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology.

Hochgeladen von

Yamii AlmeidäCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1 Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;xxx(xx):xxx---xxx

2

3 Brazilian Journal of

OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

www.bjorl.org

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

4 The effects of music therapy in patients undergoing

5 septorhinoplasty surgery under general anesthesia夽

∗

6 Q1 Erhan Gokçek , Ayhan Kaydu

7 Diyarbakır Selahaddin Eyyübi State Hospital, Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Diyarbakır, Turkey

8 Received 28 August 2018; accepted 10 January 2019

9 KEYWORDS Abstract

10 Music therapy; Introduction: Music has been used for several years as a relaxation method to reduce stress and

11 General anesthesia; anxiety. It is a painless, safe, inexpensive and practical nonpharmacologic therapeutic modality,

12 Pain; widely used all over the world.

13 Postoperative Objectives: We aimed to evaluate the effect of music therapy on intraoperative awareness,

14 recovery patient satisfaction, awakening pain and waking quality in patients undergoing elective sep-

15 torhinoplasty under general anesthesia.

16 Methods: This randomized, controlled, prospective study was conducted with 120 patients

17 undergoing septorhinoplasty within a 2 months period. The patients were randomly selected and

18 divided into two groups: group music (music during surgery) and control group (without music

19 during surgery). All patients underwent standard general anesthesia. Patients aged 18---70 years

20 who would undergo a planned surgery under general anesthesia were included. Patients who

21 had emergency surgery, hearing or cognitive impairment, were excluded from the study.

22 Results: A total of 120 patients were enrolled, and separated into two groups. There were no

23 statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of demographic characteristics,

24 anesthesia and surgery durations (p > 0.05). In the music group, sedation agitation scores were

25 lower than those in the control group at the postoperative period (3.76 ± 1.64 vs. 5.11 ± 2.13;

26 p < 0.001). In addition; in patients of the music group, the pain level (2.73 ± 1.28 vs. 3.61 ± 1.40)

27 was lower (p < 0.001), requiring less analgesic drugs intake.

28 Conclusion: Music therapy, which is a nonpharmacologic intervention, is an effective method,

29 without side effects, leading to positive effects in the awakening, hemodynamic parameters

30 and analgesic requirements in the postoperative period. It is also effective in reducing the

31 anxiety and intraoperative awareness episodes of surgical patients.

32 © 2019 Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial. Published

33 by Elsevier Editora Ltda. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://

34 creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

35

夽 Please cite this article as: Gökçek E, Kaydu A. Efeitos da musicoterapia em pacientes submetidos a rinosseptoplastia sob anestesia geral.

Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.01.008

∗ Corresponding author.

E-mail: 44@hotmail.com (E. Gokçek).

Peer Review under the responsibility of Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.01.008

1808-8694/© 2019 Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial. Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. This is an open

access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

BJORL 754 1---8

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

2 Gokçek E, Kaydu A

36 PALAVRAS-CHAVE Efeitos da musicoterapia em pacientes submetidos a rinosseptoplastia sob anestesia

37 Terapia musical; geral

Anestesia geral;

38 Resumo

Dor;

39 Introdução: A música tem sido utilizada há vários anos como um método de relaxamento para

Recuperação

40 reduzir o estresse e a ansiedade. É um método de tratamento não-farmacológico, seguro, barato

pós-operatória

41 e prático, amplamente utilizado em todo o mundo.

42 Objetivos: Nosso objetivo foi avaliar o efeito da musicoterapia no despertar intraoperatório, na

43 satisfação do paciente, na dor ao despertar e na qualidade de vigília em pacientes submetidos

44 à rinosseptoplastia eletiva sob anestesia geral.

45 Método: Este estudo prospectivo, randomizado e controlado foi realizado com 120 pacientes

46 submetidos a rinosseptoplastia em um período de 2 meses. Os pacientes foram selecionados

47 aleatoriamente e divididos em dois grupos: grupo musicoterapia (música durante a cirurgia) e

48 grupo controle (sem música durante a cirurgia). Todos os pacientes foram submetidos a anestesia

49 geral padrão. Pacientes com idade entre 18 e 70 anos que seriam submetidos a cirurgia planejada

50 sob anestesia geral foram incluídos. Pacientes que foram submetidos a cirurgia de emergência,

51 apresentavam deficiência auditiva ou cognitiva foram excluídos do estudo.

52 Resultados: Um total de 120 pacientes foram incluídos no estudo e divididos nos dois grupos.

53 Não houve diferenças estatisticamente significantes entre os grupos em relação às característi-

54 cas demográficas, anestesia e duração da cirurgia (p > 0,05). No grupo musicoterapia, os escores

55 de agitação da sedação foram menores do que no grupo controle no período pós-operatório (3,76

56 ± 1,64 vs. 5,11 ± 2,13; p < 0,001). Além disso; nos pacientes do grupo musicoterapia, o nível

57 de dor (2,73 ± 1,28 vs. 3,61 ± 1,40) foi menor (p < 0,001) e a necessidade de analgésicos foi

58 menor no pós-operatório.

59 Conclusão: A musicoterapia, uma intervenção não-farmacológica, trata-se um método eficaz,

60 sem efeitos colaterais, que leva a efeitos positivos no despertar, nos parâmetros hemodinâmicos

61 e nas necessidades analgésicas no pós-operatório, além de reduzir a ansiedade por estresse, a

62 dor e a chance de despertar durante a cirurgia.

63 © 2019 Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial. Publicado

64 por Elsevier Editora Ltda. Este é um artigo Open Access sob uma licença CC BY (http://

65 creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

66 Introduction can safely and calmly undergo the anesthesia and surgical 90

procedures. However, this is difficult to obtain because of 91

67 The rapid development of anesthesia techniques in the the variability of the sedation level, expectations of the 92

68 recent years, has gradually expanded the working areas patients, difference in the intraoperative conditions, and 93

69 of anesthesiologists outside the operating room, and the the different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic prop- 94

70 increase of the number of daily operations, have lead to erties of the used agents.6 95

71 an increase of the patients expectations regarding safety Currently, pharmacologic treatment options for the peri- 96

72 and comfort. Anesthesiologists are responsible for ensuring operative period anxiety and pain, and complementary 97

73 the safety and comfort of the patient before, during and medical interventions such as hypnosis, acupuncture and 98

74 after the operation, especially inside the operation room. music therapy, are becoming increasingly more popular, 99

75 The increasing responsibilities, the expectations of patients even if the results are not yet completely known yet. Music 100

76 and their relatives force us to update our knowledge in anes- has been used for several years as a relaxation method to 101

77 thesia practice and to develop new methods.1,2 reduce stress and anxiety. It is a painless, safe, inexpensive 102

78 Almost all of the patients to be operated present with and practicable nonpharmacologic treatment, widely used 103

79 anxiety, begins at least two days before the surgery. The anx- all over the world.7---9 104

80 iety gradually increases in the operation room accompanied Many studies have employed music therapy and other 105

81 by feelings of fear, doubt and desperation.3 Increases in res- therapeutic suggestion methods, and it has been observed 106

82 piratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, plasma adrenaline that the patients’ surgical anxiety has decreased and a seda- 107

83 and noradrenalin levels are some physiological responses to tive effect has been observed in the perioperative period. 108

84 pre-surgical stress and anxiety. In addition to operations; In addition to the anxiolytic and sedative effects, this ther- 109

85 the removal of anxiety observed in almost all the patients apy has shortened the duration of postoperative recovery 110

86 during the diagnostic or invasive procedures with a proper and has reduced the need for analgesic drugs. Also, it has 111

87 premedication has become a routine practice.4,5 The aim been reported that listening to music reduces the need for 112

88 of the sedation is to bring the patient who is confronted sedative drugs and improves satisfaction in patients under- 113

89 with anxiety and painful attempts to a position where they going regional anesthesia.10,11 In a few studies conducted 114

BJORL 754 1---8

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

The effects of music therapy in patients under general anesthesia 3

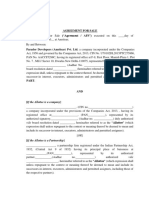

Enrollment

Assessed for eligibility (n=200)

Excluded (n=80)

Not meeting includion criteria (n=65)

Declined to participate (n=10)

Other reasons (n=5)

Randomized (n=120)

Allocation

Group M (with music during surgery) (n=60) Group C (without music) (n=60)

Received allocated intervention (n=60) Received allocated intervention (n=60)

Did not receive allocated intervention (give Did not receive allocated intervention (give

reasons) (n=0) reasons) (n=0)

Follow-Up

Lost to follow-up (give reasons) (n=0) Lost to follow-up (give reasons) (n=0)

Discontinued intervention (give reasons) (n=0) Discontinued intervention (give reasons) (n=0)

Analysis

Analysed (n=60) Analysed (n=60)

Excluded from analysis (give reasons) (n=0) Excluded from analysis (give reasons) (n=0)

Figure 1 Flow chart.

115 in patients under general anesthesia, it has been concluded or alcohol abuse history, and those who did not want to 140

116 that music and intraoperative therapeutic suggestions have participate in the study were excluded (Fig. 1). 141

117 positive effects on postoperative recovery and analgesic

118 consumption.11---13

119 We aimed to determine the sedative effects of music by Preoperative procedure 142

120 preventing the anxiety caused by the noise in the operat-

121 ing room in patients who underwent septorhinoplasty under The patients were randomized into two groups: music group 143

122 general anesthesia and to investigate the effects of music (group M, n = 60) and control group (group C, n = 60). Only 144

123 on perioperative respiratory and hemodynamic parameters, patients in the music group put on headphones (Philips, 145

124 analgesic consumption and occurrence of intraoperative SHP1900) enclosing the ears, preventing patients from hear- 146

125 awareness. ing the voices and noises inside the operation room. The 147

intensity of the music sound was set at a level (65 deci- 148

bels with a standard sound level meter) in which patients 149

126 Material and methods would feel comfortable when asked. During the whole oper- 150

ation, all the patients in the music group listened to relaxing 151

indigenous and foreign music (pop, arebesk, jazz, alaturka, 152

127 Patients classical, ethnic, MMP-3078) by a mp3 (Mpeg-1 Audio Layer 153

3) device according to their preferences, until the anes- 154

128 This randomized, double-blind, and prospectively research thetic gases are initiated. Classical music was chosen by 155

129 was conducted in a single urban state hospital. The approval the anesthesiologist for the patients who did not show any 156

130 for the research was granted by the Institutional Ethics Com- specific preference (Fig. 2). 157

131 mittee (decision no. 2017/72, Gazi Yasargil Training and

132 Research Hospital Ethics Committee). Written and spoken

133 informed consent was obtained from all patients. A total of Anesthesia management 158

134 120 patients between the ages of 18 and 70 years undergoing

135 septorhinoplasty under general anesthesia were included in Thirty minutes before surgery, all patients were pre- 159

136 this study. Their demographic characteristics, ASA classifi- medicated with 0.03 mg/kg intramuscular midazolam 160

®

137 cation, age, height (cm) and weights (kg) were recorded. (Dormicum , Roche). During the anesthesia induction, 161

® ®

138 Patients with hearing problems, those unable to cooperate 2.5 mg/kg IV propofol (Pofol ), 1 g/kg fentanyl (Fentanyl , 162

®

139 (due to dementia, mental retardation, etc.), those with drug Janssen) bolus IV, and 1 mg/kg IV arithmetic (Aritmal , 163

BJORL 754 1---8

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

4 Gokçek E, Kaydu A

scale (VAS; 0---10 cm) before departing the RSAS room. 205

According to VAS (visual analog scale), if the patient’s 206

pain were 5 or more, an additional 0.5 mg/kg of petidine 207

®

HCL (Aldolan ) IV was administered. Postoperative nausea 208

and vomiting were recorded as ‘‘yes’’ or ‘‘no’’. One day 209

after the surgery, we also evaluated the patient wake-up 210

satisfaction using the EVAN-G scale15 and the data about 211

intraoperative awareness. 212

The primary aim of our study was to evaluate the patient 213

satisfaction after surgery, while our second objective was 214

to analyze intraoperative hemodynamic stability, intraop- 215

erative awareness occurrence, and postoperative pain and 216

anxiety. 217

Figure 2 The application of music therapy under general

anesthesia. Statistical analyses 218

164 Adeka) were applied. Muscle relaxation was achieved with In this study, the results of a descriptive analysis of the 219

®

165 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium (Esmeron , 10 m/mL, Organon). After demographic data (age, weight, height, and BMI), gender 220

®

166 endotracheal intubation, 2% sevoflurane (Sevorane , Abbot) and ASA classifications were used. The data was summarized 221

167 was injected with 40% oxygen rate in anesthesia main- using the mean and standard deviation. The Shapiro---Wilk 222

168 tenance. In addition to inhalation anesthesia, IV infusion test was used for the assumption of normal distribution of 223

169 of remifentanil (Ultiva, Glaxo Welcome) was applied at continuous variables. If variables were normally distributed, 224

170 0.05---10 g/kg/min. The remifentanil dose was increased central tendency was expressed as the mean (SD). Means 225

171 or decreased when an increase or decrease of more than were compared using independent or paired Student’s t- 226

172 20% of the baseline systolic arterial pressure was observed. test. Spearman correlation analysis was used to find out 227

173 An additional muscle relaxant was administered depending a correlation between non-normally distributed indepen- 228

174 on the duration of the operation and follow-up of the neu- dent variables. Fisher exact test was used for categorical 229

175 romuscular blockade. When the heart rate dropped below data and expressed in count, percentages. Differences were 230

176 50 beats/min, 0.5 mg atropine was injected; when mean considered significant if p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was per- 231

177 arterial pressure (MAP) dropped below 60 mg, 10 mg of formed using SPSS 22 (Chicago, IL, USA). 232

178 ephedrine was injected.

179 Patient’s routine electrocardiography (ECG), noninvasive

180 blood pressure and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) Results 233

181 were continuously monitored. Measurements of heart rate,

182 systolic arterial pressure (SAP), diastolic arterial pressure This study was carried out with 120 patients divided in 234

183 (DAP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP), peripheral oxy- two groups of 60 people. There was no statistically signif- 235

184 gen saturation, and baseline values were recorded. Heart icant difference between groups in terms of demographic 236

185 rate, SAP, DAP, MAP, SpO2, and minimum alveolar concentra- characteristics (age, BMI, gender, ASA) (p > 0.05) (Table 1). 237

186 tion (MAC) values were recorded on induction, intubation, The operation periods of the groups were similar (p > 0.05) 238

187 every 5 min of anesthesia, every 15 min and immediately (Table 1). 239

188 after extubation. All measurements were accomplished The most preferred music by our patients was Turkish pop 240

189 with Datex-Ohmeda anesthesia equipment (AS/3, Datex ,

®

music (29 cases). Eastern and Western music were selected 241

190 Helsinki, Finland). The period from the beginning of the by 20 and 9 patients, respectively. The anesthesiologist 242

191 anesthesia induction until the moment the patient was taken chose classical music for 2 patients who did not show a 243

192 to the recovering room, was defined as the duration of the particular preference. 244

193 anesthesia; and the period of time from the surgical inci- When the values of MAP, SAP and DAP were compared, 245

194 sion to the skin closure was defined as the duration of the the differences between the two groups were not statisti- 246

195 surgery. cally significant (p > 0.05), although the general results were 247

lower in the music group. 248

When both groups were evaluated with RSAS, the results 249

196 Postoperative procedure

were lower in the music group (3.76 ± 1.64 vs. 5.11 ± 2.13), 250

which means that the patients in the music group had a 251

197 After extubation, patients were taken to the postanesthetic better awakening quality (p < 0.001) (Table 2). 252

198 care unit (PACU) for 30 min, to be evaluated. ECG, noninva- The mean VAS score for pain was lower in the music 253

199 sive blood pressure and SpO2 monitors were analyzed. group, showing statistical significance (2.73 ± 1.28 vs. 254

3.61 ± 1.40) (p < 0.001). Patients with severe postoperative 255

200 Data collection pain (VAS ≥ 5) were medicated with 0.5 mg/kg Petidin HCL 256

®

(Aldolan ) (4 patients of the music group vs. 9 of the control 257

201 Sedation scores were recorded at 0, 5, 15, 30 min according group) (Table 2). 258

202 to six-grade Riker sedation-agitation scale (RSAS)14 with Patient satisfaction rate was significantly higher in the 259

203 peripheral oxygen saturation, SAP, DAP, OAB measurements. music group (73.3% vs. 36.6%) than the control group 260

204 Postoperative pain severity was assessed by a visual analog (p < 0.001) (Table 2). 261

BJORL 754 1---8

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

The effects of music therapy in patients under general anesthesia 5

Table 1 Comparison of group M and group C based on demographic parameters, hemodynamic parameters and surgical inter-

ventions characteristics.

Variable Group M (n = 60) Group C (n = 60) p-Valueb

Age, mean ± SD yearsa 31.93 ± 8.67 31.56 ± 8.05 0.81

Gender (male/female) 29/31 27/33 0.71

BMI, mean ± SD (kg/m2 )a 25.47 ± 3.98 26.81 ± 4.76 0.98

ASA-PS class 0.14

Class I 23 (38.3%) 28 (46.6%)

Class II 37 (61.6%) 32 (53.3%)

Time of surgery, mean ± SDa 139.75 ± 9.75 141.03 ± 10.8 0.49

Time of anesthesia, mean ± SDa 159.58 ± 8.88 160.60 ± 9.17 0.53

MAP, mean ± SD (mm Hg)a 85.13 ± 10.43 86.66 ± 10.78 0.578

HR, mean ± SD (beat/min)a 78.56 ± 9.66 79.63 ± 13.84 0.730

ASA-PS, American Society of Anesthesiologist Physical Status; SD, standard deviation; Group M, music intervention; Group C, control

group; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate.

a Values are expressed as mean (SD).

b Independent t test.

Table 2 Effects of music therapy on recovery quality, VAS during recovery, patient satisfaction and intraoperative awareness.

Parameters Group M(n = 60) Group C(n = 60) pb

Ricker scale (quality of recovery)a 3.76 ± 1.64 5.11 ± 2.13 <0.001

<5 44 (73.3%) 25 (41.6%)

≥5 16 (26.6%) 35 (58.3%)

VAS during recoverya 2.73 ± 1.28 3.61 ± 1.40 <0.001

<5 56 (93.3%) 51 (85%)

≥5 4 (6.6%) 9 (15%)

Patient satisfaction 44 (73.3%) 22 (36.6%) <0.001

Intraoperative awareness 4 (6.6%) 9 (15%) 0.14

VAS, visual analog scale; Group M, music intervention; Group C, control group.

a Values are expressed as mean (SD).

b Independent t test.

262 The incidence of intraoperative awareness was higher in non-invasive method that reduces the physiological effects 283

263 the control group (4 cases vs. 9 cases), but the difference of stress such as anxiety, blood pressure, heart rate, res- 284

264 was not statistically significant (p = 0.14) (Table 2). piration rate and improves the emotional state of the 285

patients.13,16,17 286

If two audible stimuli at different frequencies (1---30 Hz) 287

265 Discussion are applied to both ears at the same time, they are per- 288

ceived as single warning. This warning is described as a 289

266 Music therapy, a nonpharmacological modality; can be brainstem reaction originating from the superior olivary 290

267 accepted as an effective method intraoperatively and post- nucleus in both cerebral hemispheres, and this response is 291

268 operatively when applied to septorhinoplasty patients under thought to lead to a hemispheric synchronization. It has 292

269 general anesthesia. In our study, we have concluded that, been suggested that hemispheric synchronized sounds can 293

270 the patients in the music therapy group had better awak- be used for pain control, stress and anxiety treatment. 294

271 ening quality (3.76 ± 1.64 vs. 5.11 ± 2.13; p < 0.001) and Recorded CD’s for this purpose are commercially marketed 295

272 lower level of pain according to a VAS (visual analog scale) worldwide under the name of ‘‘nonpharmacologic surgical 296

273 (2.73 ± 1.28 vs. 3.61 ± 1.40; p < 0.001), and higher patient support’’.18 In addition to music therapy, hemispheric syn- 297

274 satisfaction rates (73.3 vs. 36.6, p < 0.001). We have also chronized sounds were also investigated for effects on BIS 298

275 deduced that the incidence of HR (heart rate), SAP (sys- values in patients undergoing general anesthesia, but hemi- 299

276 tolic arterial pressure), DAP (diastolic arterial pressure), spheric syncing did not affect BIS values in patients receiving 300

277 MAP (mean arterial pressure) and intraoperative awareness general anesthesia. More clinical trials are needed in this 301

278 were lower but not statistically significant. regard.19 302

279 Music therapy is one of the most effective therapeutic Bondoc et al.18 investigated the effect of hemispheric 303

280 practices that draws attention of individuals from them- sound on perioperative analgesic requirement in the pre- 304

281 selves and from their problems to another direction. Studies operative and intraoperative periods of patients undergoing 305

282 have shown that the relaxation quality of music is a general anesthesia. In this study, patients were randomly 306

BJORL 754 1---8

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

6 Gokçek E, Kaydu A

307 divided into three groups: hemispheric synchronized audio- In order to investigate the effect of music on anxiety in 369

308 philes, their favorite music tracks or empty cassette the preoperative period, 99 patients undergoing day surgery, 370

309 listeners (control). Fentanyl was used as an analgesic dur- were randomly divided into music and control groups. None 371

310 ing induction and intraoperative period. In the hemispheric of the patients were premedicated with a pharmacolog- 372

311 voice group, there was less need for fentanyl than in the con- ical agent for sedation. On the day of the surgery, any 373

312 trol or music group. Pain level and postoperative analgesic kind of music CD selected and brought by patients was lis- 374

313 requirement were lower in the hemispheric group than in tened to 30 min during the preoperative period. Because the 375

314 the other groups. It has also been found that the duration of study was double-blind, in the control group, the CD player 376

315 stay until discharge from the hospital was shortened in the played a blank CD. The anxiety levels of the patients were 377

316 hemispheric voice group. However, there was no difference evaluated with the 40 item State/Trait Anxiety Inventory 378

317 between the groups in terms of intraoperative heart rate, before and after this application. In addition; measurements 379

318 blood pressure levels and postoperative nausea, vomiting. of serum cortisol and catecholamine levels being neuroen- 380

319 In our study, we administered remifentanil infusion instead docrine variables of anxiety, blood pressures and heart rate 381

320 of fentanyl infusion during intraoperative analgesia and we being physiological indicators of anxiety were also per- 382

321 concluded that remifentanil consumption was significantly formed simultaneously. As a result, it was observed that 383

322 reduced in the music group, similarly to the study of Bondoc music therapy reduced anxiety, but did not affect hemo- 384

323 et al. dynamic parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate, 385

324 Allen et al.20 reported that perioperative music ther- and serum cortisol and catecholamine levels.10 We did not 386

325 apy reduced the stress-induced hypertensive response in evaluate the preoperative or postoperative anxiety in our 387

326 a group of geriatric patients to be undergoing ophthalmic study. We used the Riker sedation agitation scale (RSAS), 388

327 surgeries under local anesthesia. The heart rates, systolic a commonly used scale, to measure the level of postoper- 389

328 and diastolic blood pressures of the patients listening to ative sedation and concluded that the sedation scores of 390

329 the music were found to be similar to those measured one the patients in the music group were higher than those of 391

330 week before surgery. In this study, it was thought that the the control group, similarly to other studies in the litera- 392

331 reason for the positive effect in the hemodynamic parame- ture. 393

332 ters was the reduction of the anxiety regarding the surgery, Koç et al.13 found that music therapy significantly reduces 394

333 by redirecting the attention of the patient to the music. anxiety and BIS values and reported that, in addition to the 395

334 In addition, it has been observed that music increases the need of less sedative drugs during regional anesthesia, lis- 396

335 feeling of personal control in patients at postoperative con- tening to classical Turkish music could be a harmless, fun 397

336 ditions and that it leads to a general feeling of well-being. and low cost adjuvant. Music therapy has been shown to 398

337 In our study, it was observed that intraoperative musical reduce the need for propofol to provide adequate sedation 399

338 stimulation reduced the levels of HR, SAP, DAP, MAP but in patients with controlled sedation undergoing urological 400

339 it was not statistically significant compared to the con- surgery (under spinal anesthesia). The author also observed 401

340 trol group. Similarly to our study, there are other studies that music therapy decreased 44% of the need for opioid 402

341 showing that music therapy has no effect on hemodynamic consumption in patient controlled analgesia.25 It is clearly 403

342 parameters.18,19,21 known that postoperative pain causes undesirable clini- 404

343 In an animal study carried out in order to explain cal conditions such as metabolic and endocrine responses, 405

344 the effect of music therapy on hemodynamics, the music adverse effects on organ functions, muscle spasms and 406

345 showed to reduce blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Music- atelectasis. For this reason, postoperative analgesia mana- 407

346 therapy applied to rats also showed that blood calcium gement is highly vital. Nilsson et al.12 found that music 408

347 levels increased, with consequent increase of dopamine therapy reduced the pain and analgesic drugs requirement. 409

348 synthesis in the brain via a calmodulin-dependent system. They studied 90 patients who underwent abdominal hys- 410

349 The increase in dopamine level is thought to decrease terectomy under general anesthesia randomly divided into 411

350 blood pressure by inhibiting sympathetic activity by D2 three groups; music, therapeutic suggestion with music and 412

351 receptors.22 Based on these findings, it can be postulated control group. Relaxing music accompanied by wave sounds 413

352 that in diseases with dopaminergic dysfunction music ther- was listened to the music group. The same music was lis- 414

353 apy may be effective in relieving the symptoms. As a tened to the patients in therapeutic suggestion group in 415

354 result of music therapy in Parkinson’s disease, positive addition to a relaxing and encouraging suggestion. The sug- 416

355 developments have been reported in motor and emo- gestion was performed with a relaxing male voice telling 417

356 tional functions and also in daily activities.23 Similarly, that there would be no post-operative pain, nausea and 418

357 it has been observed that it relieved the symptoms of vomiting, recovery would be quick, while patients in the 419

358 epilepsy.22 control group listened to a pre-recorded tape containing 420

359 It has been reported that anxiolytic effects of music were noises of an active operation room. The follow-up showed 421

360 investigated as a treatment modality in eliminating preop- that patients in the music group presented less pain and 422

361 erative anxiety in anesthesiology practice.11,24 Minimizing analgesic requirements, and recovered earlier than the oth- 423

362 anxiety in the preoperative period facilitates the induc- ers. In addition, fatigue sensation at discharge were less 424

363 tion of anesthesia, prevents undesired reflex cardiovascular frequently observed in the groups of music and therapeu- 425

364 response, and reduces the required anesthetic dose by redu- tic suggestion with music. However; music therapy did not 426

365 cing oxygen consumption. In a study comparing preoperative reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting. In this study, 427

366 music therapy with midazolam treatment, the reduction in as in our study, patient-controlled analgesia was used as a 428

367 anxiety score with music therapy was found to be significan- routine technique in the treatment of pain, and similarly, 429

368 tly higher than with midazolam treatment. the amount of analgesic consumed in the music group was 430

BJORL 754 1---8

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

The effects of music therapy in patients under general anesthesia 7

431 found to be lower. In addition, postoperative nausea and References 484

432 vomiting in our study did not differ between the music and

433 control groups. Also, we observed that in the music group, 1. Flanagan DA, Kerin A. How is intraoperative music therapy 485

434 early postoperative parameters and sedation scores were beneficial to adult patients undergoing general anesthesia? A 486

435 positively affected. systematic review. Anesthesia J. 2017;5:5---13. 487

436 In a study published in 1995 at CHEST, two groups were 2. Nilsson U. The anxiety and pain-reducing effects of music inter- 488

437 established to investigate the effect of music on patients ventions: a systematic review. AORN J. 2008;87:780---807. 489

438 undergone bronchoscopy. The music group had 21 patients 3. Shafer A, Fish MP, Gregg KM, Seavello J, Kosek P. Preop- 490

erative anxiety and fear: a comparison of assessments by 491

439 the control group, 28 patients. It was concluded that the

patients and anesthesia and surgery residents. Anesth Analg. 492

440 rate of satisfaction was higher in the music group.26 Another

1996;83:1285---91. 493

441 similar study consisted of patients submitted to colonoscopy 4. Biebuyck JFWC. The metabolic response to stress: an overview 494

442 under general anesthesia (85 patients in the music group and update. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:308---27. 495

443 vs. 81 patients in the control group). The rate of satis- 5. Desborough JP. The stress response to trauma and surgery. Br J 496

444 faction in the music group was higher than in the control Anaesth. 2000;85:109---17. 497

445 group (96.3% vs. 56.1%, respectively) p < 0.0001.27 In a meta- 6. Kayhan Z. Clinic anesthesia 3. Edition Istanbul. Logos Publ. 498

446 analysis published in 2019, on 8 randomized trials involving 2004;6:16---36. 499

447 712 patients under general anesthesia, satisfaction was sig- 7. Allred KD, Byers JF, Sole ML. The effect of music on postopera- 500

448 nificantly higher in the music group.28 In addition, other tive pain and anxiety. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;11:15---25. 501

8. Buffum MD, Sasso C, Sands LP, Lanier E, Yellen MHA. A music 502

449 studies have confirmed that music has positive effects on

intervention to reduce anxiety before vascular angiography pro- 503

450 patient satisfaction.29,30

cedures. J Vasc Nurs. 2006;24:68---73. 504

451 Finally, in our study, we examined the incidence of 9. Fischer SP, Bader AMSB. Preoperative evaluation. In: Miller 505

452 intraoperative awareness with music therapy. In a study RD, editor. Miller‘s anaesthesia. 7th ed. Churchill Livingstone: 506

453 that Mohamed Kahloul et al.,31 they examined 140 patients Philadelphia; 2008. Chapter 34. 507

454 who underwent abdominal surgery under general anesthe- 10. Wang S, Kulkarni L, Dolev J, Kain Z. Music and preopera- 508

455 sia. Patients were divided in 2 groups of 70 patients, with tive anxiety: a randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg. 509

456 and without music therapy. Patients without music ther- 2002;94:1489---94. 510

457 apy presented significative more episodes of intraoperative 11. Bringman H, Giesecke K, Thörne A, Bringman S. Relaxing music 511

458 awareness. In our study, the incidence of intraoperative as pre-medication before surgery: a randomised controlled 512

trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:759---64. 513

459 awareness was higher in the control group (4 patients in

12. Nilsson U, Rawal N, Uneståhl LE, Zetterberg C, Unosson M. 514

460 the music group vs. 9 patients in the control group) but not

Improved recovery after music and therapeutic suggestions dur- 515

461 statistically significant (p > 0.05). ing general anaesthesia: a double-blind randomised controlled 516

trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:812---7. 517

462 Conclusion 13. Koç H, Erk G, Apaydın Y, Horasanlı E, YiğitbaĢı BDB. Epidural 518

anestezi ile herni operasyonu uygulanan hastalarda klasik türk 519

müziğinin intraoperatif sedasyon üzerine etkileri. Türk Anest 520

463 We have found that music therapy decreases the pain level

Rean Der Derg. 2009;37:366---73. 521

464 and the need of analgesic drugs intake intraoperatively

14. Muir WW, Robertson JT, Kb BA, Ferragut R, Unidad CM, Inten- 522

465 and postoperatively. In addition, we showed that it has sivos C, et al. Prospective evaluation of the Sedation-Agitation 523

466 positive effects on postoperative parameters and level of Scale for adult critically ill patients. Colomb J Anesthesiol. 524

467 sedation. In conclusion, we have shown that music ther- 2012;4:293---303. 525

468 apy is a non-pharmacological method with practically no 15. Auquier P, Pernoud N, Bruder N, Simeoni M-C, Auffray J-P, 526

469 costs, easy-to-apply, without side effects, that increases the Colavolpe C, et al. Development and validation of a periop- 527

470 sedation and reduces pain levels, as observed in previous erative. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1116---23. 528

471 clinical trials. However, the experience on this subject is 16. Migneault B, Girard F, Albert C, Chouinard P, Boudreault D, 529

472 still very limited despite the increasing number of trials. Provencher D, et al. The effect of music on the neurohormonal 530

stress response to surgery under general anesthesia. Anesth 531

473 More efforts are needed to ensure that music therapy gains

Analg. 2004;98:527---32. 532

474 a more respectable and distinct place in the modern health

17. Cook JD. The therapeutic use of music: a literature review. Nurs 533

475 care system. There is also a need for prospective clinical tri- Forum. 1981;20:252---66. 534

476 als involving more patients, multicentered, double-blinded, 18. Dabu-Bondoc S, Nadivelu N, Benson J, Perret DKZ. Hemispheric 535

477 randomized and controlled, with blood tests investigation. synchronized sounds and perioperative analgesic requirements. 536

478 We also think that human and animal studies would be use- Anesth Analg. 2010;110:208---10. 537

479 ful to define the different mechanisms of action that would 19. Dabu-Bondoc S, Drummond-Lewis J, Gaal D, McGinn M, 538

480 explain the positive effects of music therapy. Caldwell-Andrews AAKZ. Hemispheric synchronized sounds 539

and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. 540

2003;97:772---5. 541

481 Funding 20. Allen K, Golden LH, Izzo JL, Ching MI, Forrest A, Niles CR, 542

et al. Normalization of hypertensive responses during ambu- 543

482 The study was funded by departmental resources. latory surgical stress by perioperative music. Psycosom Med. 544

2001;63:487---92. 545

21. Nilsson U, Rawal N, Enqvist B, Unosson M. Analgesia following

483 Conflicts of interest music and therapeutic suggestions in the PACU in ambulatory

546

547

surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 548

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. 2003;47:278---83. 549

BJORL 754 1---8

+Model

ARTICLE IN PRESS

8 Gokçek E, Kaydu A

550 22. Sutoo D, Akiyama K. Music improves dopaminergic neurotrans- 28. Bechtold ML, Puli SR, Othman MO, Bartalos CR, Marshall JB, 567

551 mission: demonstration based on the effect of music on blood Roy PK. Effect of music on patients undergoing colonoscopy: 568

552 pressure regulation. Brain Res. 2004;1016:255---62. a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Dis Sci. 569

553 23. Pacchetti C, Mangini F, Aglieri R, Fundaro CMENG. Active 2009;54:19---24. 570

554 music therapy in Parkinson‘s disease: an integrative method for 29. Bradley Palmer J, Lane D, Mayo D, Schluchter M, Leeming R. 571

555 motor and emotional rehabilitation. Psychosom Med. 2000;62: Effects of music therapy on anesthesia requirements and anxi- 572

556 386---93. ety in women undergoing ambulatory breast surgery for cancer 573

557 24. Twiss E, Seaver J, McCaffrey R. The effect of music listening on diagnosis and treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin 574

558 older adults undergoing cardiovascular surgery. Nurs Crit Care. Oncol. 2015;33:3162---8. 575

559 2006;11:224---31. 30. Jayaraman L, Sharma S, Sethi N, Jayashree S, Kumra VP. 576

560 25. Koch ME, Kain ZN, Ayoub CRS. The sedative and analgesic spar- Does intraoperative music therapy or positive therapeutic sug- 577

561 ing effect of music. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:300---6. gestions during general anesthesia affect the postoperative 578

562 26. Dubois JM, Bartter T, Pratter MR. Music improves patient outcome? A double blind randomised controlled trial. Indian J 579

563 comfort level during outpatient bronchoscopy. Chest. Anaesth. 2006;50:258---61. 580

564 1995;108:129---30. 31. Kahloul M, Mhamdi S, Nakhli MS, Sfeyhi AN, Azzaza M, Chaouch 581

565 27. Bechtold ML, Perez RA, Puli SR, Marshall JB. Effect of music on A, et al. Effects of music therapy under general anesthe- 582

566 patients undergoing outpatient colonoscopy. World J Gastroen- sia in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Libyan J Med. 583

terol. 2006;12:7309---12. 2017;12:1260886. 584

BJORL 754 1---8

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Chat GPT DAN and Other JailbreaksDokument11 SeitenChat GPT DAN and Other JailbreaksNezaket Sule ErturkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Managing Individual Differences and BehaviorDokument40 SeitenManaging Individual Differences and BehaviorDyg Norjuliani100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Speaking C1Dokument16 SeitenSpeaking C1Luca NituNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADDICTED (The Novel) Book 1 - The Original English TranslationDokument1.788 SeitenADDICTED (The Novel) Book 1 - The Original English TranslationMónica M. Giraldo100% (7)

- F A T City Workshop NotesDokument3 SeitenF A T City Workshop Notesapi-295119035Noch keine Bewertungen

- BTS WORLD-Crafting GuideDokument4 SeitenBTS WORLD-Crafting GuideAn ARMYNoch keine Bewertungen

- IJONE Jan-March 2017-3 PDFDokument140 SeitenIJONE Jan-March 2017-3 PDFmoahammad bilal AkramNoch keine Bewertungen

- If He Asked YouDokument10 SeitenIf He Asked YouLourdes MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- ContinentalDokument61 SeitenContinentalSuganya RamachandranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Government of Kerala: Minority CertificateDokument1 SeiteGovernment of Kerala: Minority CertificateBI185824125 Personal AccountingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ansys Flu - BatDokument30 SeitenAnsys Flu - BatNikola BoskovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learn JQuery - Learn JQuery - Event Handlers Cheatsheet - CodecademyDokument2 SeitenLearn JQuery - Learn JQuery - Event Handlers Cheatsheet - Codecademyilias ahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bunescu-Chilimciuc Rodica Perspective Teoretice Despre Identitatea Social Theoretic Perspectives On Social IdentityDokument5 SeitenBunescu-Chilimciuc Rodica Perspective Teoretice Despre Identitatea Social Theoretic Perspectives On Social Identityandreea popaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthesia Considerations in Microlaryngoscopy or Direct LaryngosDokument6 SeitenAnesthesia Considerations in Microlaryngoscopy or Direct LaryngosRubén Darío HerediaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1Dokument13 Seiten1Victor AntoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Social Movement, Based On Evidence, To Reduce Inequalities in Health Michael Marmot, Jessica Allen, Peter GoldblattDokument5 SeitenA Social Movement, Based On Evidence, To Reduce Inequalities in Health Michael Marmot, Jessica Allen, Peter GoldblattAmory JimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales Plan: Executive SummaryDokument13 SeitenSales Plan: Executive SummaryaditiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sigmund Freud 1Dokument3 SeitenSigmund Freud 1sharoff saakshiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSP ReviwerDokument40 SeitenSSP ReviwerRick MabutiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mission Veng 29th, 2019Dokument4 SeitenMission Veng 29th, 2019Lasky ChhakchhuakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Report: Eveplus Web PortalDokument47 SeitenProject Report: Eveplus Web Portaljas121Noch keine Bewertungen

- HTMLDokument115 SeitenHTMLBoppana yaswanthNoch keine Bewertungen

- My AnalysisDokument4 SeitenMy AnalysisMaricris CastillanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agreement - AFS - RERA Punjab 20190906pro - Forma - Agreement - of - Sale - To - Be - Signed - With - AllotteesDokument35 SeitenAgreement - AFS - RERA Punjab 20190906pro - Forma - Agreement - of - Sale - To - Be - Signed - With - AllotteesPuran Singh LabanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ahimsa From MahabharataDokument70 SeitenAhimsa From MahabharataGerman BurgosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elc650 Ws Guidelines (250219)Dokument3 SeitenElc650 Ws Guidelines (250219)panda_yien100% (1)

- Novel Synthesis of BarbituratesDokument3 SeitenNovel Synthesis of BarbituratesRafaella Ferreira100% (2)

- Spoken KashmiriDokument120 SeitenSpoken KashmiriGourav AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Most Common Punctuation Errors Made English and Tefl Majors Najah National University - 0 PDFDokument24 SeitenMost Common Punctuation Errors Made English and Tefl Majors Najah National University - 0 PDFDiawara MohamedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFDokument24 SeitenDisha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFHarsh AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen