Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Comorbidity of Anxiety Disorders With Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa

Hochgeladen von

Masha BarskyOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Comorbidity of Anxiety Disorders With Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa

Hochgeladen von

Masha BarskyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Article

Comorbidity of Anxiety Disorders

With Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa

Walter H. Kaye, M.D. Objective: A large and well-character- sive disorder (OCD) (N=277 [41%]) and so-

ized sample of individuals with anorexia cial phobia (N=134 [20%]). A majority of

nervosa and bulimia nervosa from the the participants reported the onset of

Cynthia M. Bulik, Ph.D.

Price Foundation collaborative genetics OCD, social phobia, specific phobia, and

study was used to determine the fre- generalized anxiety disorder in child-

Laura Thornton, Ph.D. quency of anxiety disorders and to under- hood, before they developed an eating

stand how anxiety disorders are related to disorder. People with a history of an eat-

Nicole Barbarich, B.S. state of eating disorder illness and age at ing disorder who were not currently ill

onset. and never had a lifetime anxiety disorder

Kim Masters, B.S. Method: Ninety-seven individuals with diagnosis still tended to be anxious, per-

anorexia nervosa, 282 with bulimia ner- fectionistic, and harm avoidant. The pres-

Price Foundation Collaborative vosa, and 293 with anorexia nervosa and ence of either an anxiety disorder or an

Group bulimia were given the Structured Clinical eating disorder tended to exacerbate

Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders and these symptoms.

standardized measures of anxiety, perfec- Conclusions: The prevalence of anxiety

tionism, and obsessionality. Their ratings disorders in general and OCD in particular

on these measures were compared with was much higher in people with anorexia

those of a nonclinical group of women in nervosa and bulimia nervosa than in a

the community. nonclinical group of women in the com-

Results: The rates of most anxiety disor- munity. Anxiety disorders commonly had

ders were similar in all three subtypes of their onset in childhood before the onset

eating disorders. About two-thirds of the of an eating disorder, supporting the pos-

individuals with eating disorders had one sibility they are a vulnerability factor for

or more lifetime anxiety disorder; the developing anorexia nervosa or bulimia

most common were obsessive-compul- nervosa.

(Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2215–2221)

C linical and epidemiological studies have consis-

tently shown that the majority of people with anorexia

mediated pathway toward the development of anorexia

nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

nervosa or bulimia nervosa experience one or more anxi- Despite this wealth of data, many questions regarding

ety disorders (1–3). Studies using trained interviewers and the nature of the relation between comorbid eating disor-

standardized diagnostic instruments in clinical samples ders and anxiety disorders remain unanswered (1). Most

have found that obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), clinical studies have investigated relatively small groups of

social phobia, and specific phobia are the most common subjects with eating disorders and have lacked sufficient

anxiety disorders in individuals with anorexia nervosa and statistical power to characterize comorbidity patterns of

bulimia nervosa. Other anxiety disorders, such as post- the more uncommon anxiety disorders. In addition, few

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and generalized anxiety studies have been sufficiently large to subtype subjects

disorder, appear to be less common; however, they were with eating disorders accurately into clearly defined

not routinely assessed in all studies. groups with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or both

Several studies have shown that, in most cases, the on- anorexia and bulimia. To our knowledge, no study has

set of anxiety disorders precedes the onset of anorexia ner- compared patterns of comorbidity of anxiety disorders

vosa or bulimia nervosa (4–6). Silberg and Bulik (7), using across these three well-defined diagnostic subcategories.

twins, identified a common genetic factor that influences The Price Foundation has supported a multicenter, in-

liability to anxiety, depression, and eating disorder symp- ternational collaborative study of the genetics of eating

toms. This pattern of onset may simply reflect the natural disorders. This study has included a collection of affected

course of the two disorders (i.e., the average age at onset of pairs consisting of probands with bulimia nervosa who

some anxiety disorders is younger than the average age at have relatives with bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, or a

onset of anorexia nervosa), but it may also indicate that broad-spectrum eating disorder (8). The Price Foundation

childhood anxiety represents one important genetically sample is sufficiently large and rigorously diagnosed to

Am J Psychiatry 161:12, December 2004 http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org 2215

ANXIETY DISORDERS, ANOREXIA, AND BULIMIA

enable separation of participants into clearly defined eat- Comparison Women From the Community

ing disorder diagnostic subcategories. A comparison group of 694 healthy women were recruited by

The goals of the present study were to 1) calculate the fre- local advertisement and matched with the eating disorder sub-

jects based on site, age range (except no comparison subjects un-

quency of all types of anxiety disorders in a large, well-char-

der 18 years were included), ethnicity, and highest educational

acterized eating disorder sample; 2) understand how anxi- level completed. They were 18–65 years old, primarily of Euro-

ety disorders are related to factors such as state of eating pean ancestry, and at normal weight (lifetime body mass index

disorder illness and age at onset; and 3) compare tempera- range=19–28). Comparison women were excluded if they had

ment in subjects with eating disorders by lifetime anxiety medical, psychiatric, or alcohol or drug disorders or a first-degree

relative with an eating disorder. Psychiatric and substance exclu-

disorders to determine whether personality phenotypes oc-

sions were defined by the presence of any “likely” axis I disorder

cur when anxiety disorders are controlled. We hope that as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

these data will assist in identifying likely behavioral en- (SCID) Screen Patient Questionnaire—Extended (9). Also ex-

dophenotypes in our attempts to identify the genetic un- cluded were women with a history of any substantial dieting, eat-

derpinnings of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. ing disorder behaviors, or excessive concerns with weight or

shape, as defined by a score of 20 or higher on the Eating Attitudes

Test-26 (10). Comparison women completed the same battery of

Method self-report personality and symptom measures as probands and

provided blood samples for genetic analysis.

Collaborative Arrangements

Assessment Instruments

This study was supported through funding provided by the

Assessment instruments are described in greater detail else-

Price Foundation under the principal direction of Walter H. Kaye

where (8). Eating disorder symptom profiles and diagnoses of

of the University of Pittsburgh and Wade Berrettini of the Univer-

probands and affected relatives were determined by using a mod-

sity of Pennsylvania (see reference 8 for details). This initiative

ified version of the Structured Interview for Anorexic and Bulimic

was developed through a cooperative arrangement among the

Price Foundation, the University of Pittsburgh, and other aca- Disorders (11) and an expanded version of module H of the SCID

demic sites in North America and Europe. The sites of collabora- (12). Lifetime major axis I anxiety disorder diagnoses were ob-

tained by using the SCID; the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive

tive arrangement, selected on the basis of experience in the as-

sessment of eating disorders and geographical distribution, Scale (13) was administered in conjunction with the OCD section

included the University of Pittsburgh, Cornell University, Univer- of the SCID. Anxiety disorder diagnoses were made according to

DSM-IV criteria. We classified individuals who were one symp-

sity of California at Los Angeles, University of Toronto, University

of Munich, University of Pisa, University of North Dakota, Univer- tom short of the threshold diagnosis for anxiety disorders to have

sity of Minnesota, and Harvard University. Each site obtained in- probable diagnoses. Both individuals with threshold diagnoses

and those with probable diagnoses were included. The defini-

stitutional review board approval separately from its own institu-

tions for probable anxiety disorder are available on request (from

tion’s human subjects committee.

Dr. Kaye). Participants completed the State-Trait Anxiety Inven-

Phenotypic Assessment tory (14), the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (15),

and the Temperament and Character Inventory (16).

Probands met the following criteria: 1) DSM-IV lifetime diag-

nosis of bulimia nervosa, purging type; 2) age between 13 and 65 Statistical Methods

years; and 3) primarily of European descent. A current or lifetime All statistical analyses were completed by using SAS 8.0 (SAS/

history of anorexia nervosa was acceptable (some subjects had STAT software, version 8. SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Logistic re-

both bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa). (For further details gression with the generalized estimating equation, which pro-

see reference 8.) vides a chi-square value for testing significance, was used to cor-

Affected relatives were biologically related to the proband, rect for nonindependence of the sample caused by inclusion of

were 13 to 65 years old, and had at least one of the following life- family members and was applied to the data to compare rates of

time eating disorder diagnoses: 1) DSM-IV bulimia nervosa, purg- the different anxiety disorders across eating disorder subtypes.

ing type or nonpurging type; 2) DSM-IV anorexia nervosa, This same type of analysis was used to compare differences in

restricting type or binge eating/purging type (criteria were modi- patterns of onset of anxiety and eating disorders across the three

fied for this study to include individuals with and without amen- eating disorder subgroups. In addition, a Poisson regression with

orrhea); 3) or a subclinical eating disorder, defined as an eating a generalized estimating equation correction was completed to

disorder not otherwise specified. Affected relatives were excluded determine if there were differences in the number of anxiety dis-

if they were a monozygotic twin of the proband, a biological par- orders (defined as none, one, or more than one) among the eating

ent with an eating disorder (unless there was another affected disorder subgroups.

family member with whom the parent could be paired), or diag- We used a two-step process to compare differences between

nosed with binge-eating disorder as their only lifetime eating dis- currently ill and recovered participants with eating disorders who

order diagnosis. did or did not have a lifetime diagnosis of an anxiety disorder on

Subjects were considered to be recovered if, for the last 12 different personality and anxiety scales. First, a linear regression

months, they maintained normal weight and did not diet, restrict was completed on each of the variables in question with body

food intake, fast, binge-eat, purge, or exercise excessively. Cogni- mass index and age as the regressors. The residuals from these

tive components of an eating disorder, such as body image distor- analyses were then used to complete the regressions with the

tion and preoccupations with weight and shape, were not in- generalized estimating equation corrections to test for differ-

cluded in our definition because, for many individuals, these ences between the groups. The comparison women were then

aspects persist, though often abated, long after weight restoration compared with subjects in the four eating disorder groups de-

and cessation of eating disorder behaviors. Subjects were consid- fined by eating disorder recovery status (recovered versus cur-

ered to be currently ill if they either met all diagnostic criteria or rently ill) and lifetime diagnosis of any anxiety disorder (present

partial criteria for any eating disorder during the last 12 months. or absent) by using analysis of variance with generalized estimat-

2216 http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 161:12, December 2004

KAYE, BULIK, THORNTON, ET AL.

TABLE 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 672 Individuals With Eating Disorders From the Price Foundation

Collaborative Genetics Study

All Subjects Anorexia Nervosa Anorexia and Bulimia Bulimia Nervosa

Characteristic (N=672) (N=97) (N=293) (N=282) Analysis

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD χ2 (df=2) p

Age (years) 28.36 9.45 26.64 9.71 29.30 9.10 27.96 9.65 1.61 0.45

Current body mass index 21.01 3.06 19.15 2.11 19.97 2.56 22.73 2.95 109.35 0.0001*

N % N % N % N % χ2 (df=2) p

Female sex 662 98.6 94 96.9 290 99.0 278 98.6 —

Diagnosed as having at least

one anxiety disorder 427 64 53 55 198 62 176 68 4.96 0.068

OCD 277 41 34 35 129 44 114 40 2.42 0.30

Social phobia 134 20 21 22 68 23 45 16 5.24 0.07

Specific phobia 102 15 14 14 54 18 34 12 5.93 0.05

Generalized anxiety disorder 65 10 13 13 30 10 22 8 2.69 0.26

PTSD 86 13 5 5 43 15 38 13 9.88 0.007

Panic disorder 72 11 9 9 32 11 31 11 0.29 0.86

Agoraphobia 20 3 3 3 11 4 2 2 1.48 0.48

*p<0.01.

TABLE 2. Age at Onset of Eating Disorders and Anxiety Disorders in 672 Individuals With Eating Disorders From the Price

Foundation Collaborative Genetics Study

Eating Disorder

Anxiety Disorder Preceded or Occurred at

Age at Onset of Age at Onset of Preceded Eating Same Time as Anxiety Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety Disorder Eating Disorder Disorder in Subjects Disorder in Subjects Preceded Eating

(years) (years) With Anxiety Disorder With Anxiety Disorder Disorder in All Subjects

Anxiety Disorder Mean SD Mean SD N % N % N %

OCD 14.38 6.92 17.43 3.96 146 62 88 38 155 23

Social phobia 13.78 8.80 17.47 3.84 88 74 31 26 87 13

Specific phobia 11.86 8.07 18.40 4.29 64 83 13 17 67 10

Generalized anxiety

disorder 13.22 6.88 17.92 5.14 35 65 19 35 34 5

PTSD 17.46 6.94 17.57 4.86 34 41 49 59 27 4

Panic disorder 20.94 6.94 18.71 6.45 19 29 46 71 20 3

Agoraphobia 17.41 6.34 18.31 4.21 8 47 9 53 7 1

ing equation corrections. However, because there were distribu- nostic groups; however, body mass index was significantly

tional differences between the comparison women and the lower for individuals in the group with anorexia nervosa

participants with eating disorders for most of the variables, non-

parametric statistical tests (PROC NPAR1WAY in SAS) were also

and the group with anorexia and bulimia than for the

completed. Both methods yielded the same results. In addition, group with bulimia nervosa. Of the entire sample, 427

effect sizes were calculated; an effect size exceeding 0.55, which (63.5%) were diagnosed with at least one lifetime anxiety

includes intermediate to large effects in the nomenclature of Co- disorder (Table 1). The most common anxiety disorder

hen (17), was considered an indication of substantial differences.

was OCD, which occurred in approximately 40% of indi-

viduals, followed by social phobia (20%); other anxiety dis-

Results orders were somewhat less common.

Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders

Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders

A total of 741 individuals with eating disorders were by Eating Disorder Subtype

given the SCID; 97 had anorexia nervosa, 282 had bulimia

The prevalence of OCD, panic disorder, social phobia,

nervosa, 293 had both anorexia and bulimia, and 69 had

an eating disorder not otherwise specified). Because of the specific phobia, agoraphobia, and generalized anxiety dis-

small number of individuals with an eating disorder not order did not differ significantly across the three eating

otherwise specified and the diagnostic heterogeneity in- disorder subtypes (Table 1). PTSD was significantly less

herent in that subcategory, they were excluded from anal- common among individuals with anorexia nervosa than

ysis, leaving a total of 672 participants. The vast majority among those with bulimia nervosa and those with both

of individuals in each group were women (94 [96.9%] of anorexia and bulimia. A nonsignificantly greater number

the subjects with anorexia nervosa, 278 [98.6%] of those of individuals with anorexia nervosa than those with bu-

with bulimia nervosa, and 290 [99.0%] of those with anor- limia with or without anorexia had no lifetime anxiety dis-

exia and bulimia ). Age did not differ across the three diag- orders (χ2=4.96, df=2, p=0.08) (data not included).

Am J Psychiatry 161:12, December 2004 http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org 2217

ANXIETY DISORDERS, ANOREXIA, AND BULIMIA

TABLE 3. Demographic and Clinical Measures for Healthy Women in the Community and for Individuals With Remitted or

Active Eating Disorders From the Price Foundation Collaborative Genetics Study Who Did or Did Not Have Lifetime Anxiety

Disordersa

Group 3 (N=111): Group 4 (N=310):

Group 1 (N=82): Group 2 (N=160): Remitted Eating Active Eating

Remitted Eating Active Eating Disorder and One Disorder and One

Disorder and No Disorder and No or More Anxiety or More Anxiety Group 5 (N=694):

Anxiety Disorder Anxiety Disorder Disorders Disorders Healthy Women

Measure Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

Age at onset of eating disorder (years) 18.42 4.21 18.54 4.05 17.91 3.93 18.55 4.93

Age at time of study (years) 32.27 11.12 26.51 8.67 29.68 8.09 27.82 9.52 26.34 8.36

Body mass index at time of study 21.79 2.49 20.63 2.98 21.78 2.60 20.70 2.30 22.14 1.79

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

State 35.29 10.45 42.32 12.62 40.96 12.19 50.53 13.77 27.14 6.63

Trait 38.65 10.44 45.75 12.57 45.47 11.57 54.20 12.91 29.44 6.92

Harm avoidance 13.79 5.61 17.33 7.28 19.06 7.29 21.50 7.34 10.83 5.39

Total perfectionism 83.39 24.15 85.81 22.39 94.67 22.92 96.73 23.64 60.53 15.89

Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale 2.09 4.47 2.57 5.14 13.69 11.16 15.99 11.38

a Means and standard deviations were computed by using untransformed data.

b Differences with an effect size greater than 0.55, which includes intermediate to large effects, were considered substantial.

Age at Onset Relationship of Lifetime Anxiety Disorder

Age at onset of the eating disorder was available for all and State of Eating Disorder Illness

participants. The age at onset of anxiety disorder was on Self-Report Assessments

available for between 78% (specific phobia) and 98% Previous studies suggested that being ill with an eating

(PTSD) of the individuals who had an anxiety disorder. If disorder exacerbates anxiety-related symptoms in indi-

an individual stated that the anxiety disorder was present viduals with eating disorders (18). To determine how the

during childhood “as long as she or he could remember,” state of the eating disorder was associated with anxiety

we set the age at onset as 5 years old, assuming childhood symptoms, we compared individuals with eating disor-

recollections were limited before this age. For each eating ders stratified by current illness state (currently ill versus

disorder subtype, we determined whether the age at onset symptom free for at least 12 months) (Table 3). In addition,

of the anxiety disorder was before or either concurrent to determine whether anxiety symptoms were present in

with or subsequent to the onset of the eating disorder (Ta- the absence of an anxiety disorder diagnosis, we stratified

ble 2). Eating disorder onset was defined as the age at participants by the presence versus absence of one or

which all of the symptoms necessary to make the diagno- more lifetime anxiety disorder(s). Thus, the four cells for

sis were present concurrently. Because there were no sig- this analysis were characterized by current eating disorder

nificant differences in patterns of onset of anxiety or eat- and lifetime history of one or more anxiety disorders.

ing disorder for any eating disorder subtype, the groups The four groups of eating disorder subjects were rela-

were combined. When all eating disorder subtypes were tively similar in terms of age and weight. Age at the time of

considered together, the onset of OCD, social phobia, spe- study differed significantly across the four groups, but the

cific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder usually pre- mean age span of the four groups was less than 5 years

ceded the onset of the eating disorder. In contrast, PTSD, (high 20s to low 30s). Current body mass index was higher

panic disorder, and agoraphobia most often developed af- in the subjects without an anxiety disorder, regardless of

ter the onset of the eating disorder. state of eating disorder illness. However, body mass index

When the entire sample of individuals with eating disor- differed by about one unit between groups. The four

ders was considered, 23% had an onset of OCD, 13% had groups had similar ages at onset of their eating disorders.

an onset of social phobia, and 10% had an onset of specific In general, scores for anxiety, harm avoidance, perfec-

phobia in childhood, before the onset of an eating disor- tionism, and obsessionality tended to be highest in the in-

der (Table 2). Other anxiety disorders were less common. dividuals who had a lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis

Overall, 282 (42%) of the entire sample had the onset of and were ill with an eating disorder. Scores tended to be

one or more anxiety disorders in childhood, before the on- somewhat lower in those who either were currently ill with

set of an eating disorder. an eating disorder or had a lifetime anxiety disorder diag-

2218 http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 161:12, December 2004

KAYE, BULIK, THORNTON, ET AL.

stantial majority of the participants with eating disorders

had the onset of OCD, social phobia, specific phobia, or

generalized anxiety disorder in childhood, before the

emergence of an eating disorder.

Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders in Subgroups

Group Comparison Any Group Substantial of Individuals With Eating Disorders

χ2 (df=3) p Differences Differencesb

Previous studies (1) have found elevated rates of anxiety

1.40 n.s.

35.17 0.0001 1>3>2, 4; 4>5; disorders in individuals with eating disorders. However,

1>5; 3>5 these studies have assessed small groups of individuals,

63.79 0.0001 1, 3, 5>2, 4 2 and 5; 4 and 5 and many have used nonstructured or standardized in-

388.59 0.0001 5<1<2; 3<4 1 and 2; 1 and 4; 1 and 5; struments. Our study, which has three subgroups with rig-

2 and 4; 2 and 5; 3 and 4; orously defined subtypes of eating disorders (anorexia

3 and 5; 4 and 5 nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia and bulimia),

418.86 0.0001 5<1<2; 3<4 1 and 2; 1 and 3; 1 and 4;

1 and 5; 2 and 4; 2 and 5; showed that rates of most anxiety disorders were generally

3 and 4; 3 and 5; 4 and 5 similar in these subgroups.

270.75 0.0001 5<1<2<3<4 1 and 3; 1 and 4; 1 and 5;

2 and 5; 2 and 4; 3 and 5; Aside from OCD, the rates of anxiety disorders in our

4 and 5 study were usually within the range reported in a review of

330.97 0.0001 5<1; 2<3, 4 1 and 4; 1 and 5; 2 and 5; studies that used similar methods (1). In assessing OCD,

3 and 5; 4 and 5

157.47 0.0001 1, 2<3, 4 1 and 3; 1 and 4; 2 and 3; we used the SCID and also incorporated information from

2 and 4 the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, which re-

views a list of the most common obsessions and compul-

sions with the participant. The most frequently endorsed

symptoms in individuals with eating disorders were sym-

nosis. Individuals with eating disorders who had not been metry, exactness, and order. It may be that people with

symptomatic with an eating disorder in the past 12 eating disorders do not recognize these as OCD symptoms

months and who never had a lifetime diagnosis of an anx- and consequently do not endorse the more general SCID

iety disorder still had scores for anxiety, harm avoidance, screening probe. Thus, cases of OCD may be missed when

and perfectionism that were significantly higher than the SCID is used alone.

those of the comparison women in the community. For The prevalence of PTSD was lower in the anorexia ner-

subjects who were not currently ill with an eating disorder, vosa group than in the bulimia nervosa group and the an-

the ratio of having no anxiety disorder to having an anxiety orexia and bulimia group. Although not significantly dif-

disorder was 0.74. In comparison, for people ill with an ferent, the prevalence of other anxiety disorders was also

eating disorder, the ratio was 0.52 (χ2=3.85, df=1, p=0.05). lower in the anorexia nervosa group. This could reflect an

Although this could reflect some bias in terms of recall, it ascertainment bias: anorexia nervosa participants in this

may also suggest that not having an anxiety disorder has a study were selected on the basis of being a relative of a

modest association with recovery. proband with bulimia nervosa or anorexia and bulimia.

Preliminary evidence from these studies suggests that

Discussion overall severity of illness and comorbidity burden may be

lower in individuals with anorexia nervosa who are in-

To our knowledge, this study of 672 individuals with an- cluded as affected relatives than in individuals who were

orexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or anorexia and bulimia ascertained as an anorexia nervosa proband.

nervosa is the largest study to date to evaluate patterns of

comorbidity of anxiety disorders and eating disorders and Comparison With Rates of Anxiety Disorders

the only study to assess a wide range of anxiety disorders in Women in the Community

in rigorously defined subgroups of individuals with eating Our study found that people with eating disorders had a

disorders. Overall, we observed that individuals with anor- 64% rate of lifetime anxiety disorders. This is clearly higher

exia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or anorexia and bulimia than the rates of 30.5% and 12.7%–18.1% for women in the

had relatively similar rates of all anxiety disorders, with the community reported by Kessler et al. (19) and Wittchen

exception of PTSD, which was approximately three times and Essau (20), respectively. Similarly, the 41% frequency

more frequent in individuals with bulimia nervosa and of OCD in people with eating disorders is much higher

those with anorexia and bulimia than in those with anor- than the frequency found in community samples (in the

exia nervosa. In this sample, approximately two-thirds of low percents) (20, 21). Our study found that 20% of the in-

participants with eating disorders reported one or more dividuals with eating disorders had social phobia. Kessler

anxiety disorder in their lifetimes—the most common di- et al. (19) reported a rate of 15.5%, and Wittchen and Essau

agnoses were OCD (41%) and social phobia (20%). A sub- (20) reported a rate of 1%–3.5%. It is less certain whether

Am J Psychiatry 161:12, December 2004 http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org 2219

ANXIETY DISORDERS, ANOREXIA, AND BULIMIA

the rates for other anxiety disorders are higher than the Limitations

rates for women in the community. That is because the First, we opted to report age at onset as the age at which

rates for specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, all criteria for a full DSM eating disorder diagnosis were

panic disorder, and agoraphobia often have a wide range met, leading to an average age at onset of approximately 18

in community studies (19, 20). years. In some cases, individuals may have exhibited sub-

threshold eating disorder symptoms at younger ages. Sec-

Onset of Anxiety Disorders ond, age at onset of anxiety disorder diagnoses was not ob-

Versus Onset of Eating Disorders tained for all individuals, either because they were unable

Previous studies suggested that early-onset anxiety dis- to recall with confidence the age at onset or the question

orders represent a risk factor for the development of an- was not adequately assessed by the interviewer. Third, this

orexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in girls (4, 5, 7). More- study is subject to ascertainment bias; that is, our inclu-

over, retrospective accounts of premorbid personality in sion/exclusion criteria for the genetic study may have in-

children with anorexia nervosa often underscore perva- fluenced the types of individuals who were selected for this

sive anxiety as a dominant presentation (22, 23). This study. Moreover, the fact that participants came from en-

study showed that the onset of OCD, social phobia, spe- riched pedigrees might have led to higher rates of comor-

cific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder most com- bidity than would be seen in the community.

With these caveats in mind, these results both replicate

monly preceded the onset of an eating disorder. We calcu-

previous studies of smaller and less well-characterized

lated that 42% of the people with eating disorders in our

samples and extend our understanding of the nature of

total sample had the onset of one or more anxiety disor-

the relation between eating disorders and anxiety disor-

ders in childhood. This is substantially higher than the fre-

ders and traits. We believe that genetic linkage analyses

quency of overall anxiety disorders in childhood (4.7% to

dependent solely on DSM-based phenotypes are unlikely

17.7%) reported in 1995 (24). Most striking was the high

to yield strong linkage signals for eating disorders; there-

rate of childhood-onset OCD (23%) in the subjects with fore, we have advocated the search for likely behavioral or

eating disorders compared with community samples (2% temperamental endophenotypes to clarify the pheno-

to 3%) (25). This is all the more notable because the age of typic definition of eating disorders. The present results

risk of the onset of OCD in women is often in the 20s. It is underscore the pervasive presence of anxiety in individu-

less certain whether people with eating disorders had ele- als with eating disorders, even in the absence of frank

vated rates of childhood-onset social phobia (13% versus anxiety disorders, and support further exploration of the

0.6%–5.1% in community samples [24]), or of other anxi- biological and hence genetic relation between eating and

ety disorders compared with community estimates (24). anxiety pathology.

Relationship of Lifetime Anxiety Disorder Received May 27, 2003; revision received Jan. 30, 2004; accepted

and State of Eating Disorder Illness Feb. 12, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pitts-

burgh, and the Price Foundation Collaborative Group. Address re-

to Current Symptoms print requests to Dr. Kaye, Department of Psychiatry, University of

It has been reported (26–29) that people with eating dis- Pittsburgh Medical Center, Western Psychiatric Institute & Clinic,

3811 O’Hara St., Suite 600, Iroquois Bldg., Pittsburgh, PA 15213;

orders have more symptoms of anxiety, harm avoidance, kayewh@msx.upmc.edu (e-mail).

obsessionality, and perfectionism, but it is less clear Support for the clinical collection of subjects and data analysis pro-

vided by the Price Foundation.

whether such symptoms are secondary to malnutrition

The authors thank the staff of the Price Foundation Collaborative

and whether they persist after recovery. In general, we Group for their efforts in participant screening and clinical assess-

found that scores on measures of these symptoms tended ments, Eva Gerardi, and the participating families for their contribu-

tion of time and effort in support of this study.

to be most elevated in individuals who had a lifetime diag- The Price Foundation Collaborative Group includes Walter H. Kaye,

nosis of an anxiety disorder and were currently ill with an M.D., Laura Thornton, Ph.D., Nicole Barbarich, B.S., Kim Masters, B.S.,

Katherine Plotnicov, Ph.D., Christine Pollice, M.P.H., and Bernie Dev-

eating disorder. In comparison, scores tended to be lower

lin, Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh; Cynthia

in those with only one of these contributory factors. It is M. Bulik, Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of North Caro-

important to emphasize, however, that individuals who lina at Chapel Hill; Manfred M. Fichter, M.D., and Norbert Quadflieg,

Dipl.Psych., Klinik Roseneck, Hospital for Behavioral Medicine, affili-

never had a lifetime anxiety disorder and who had been ated with the University of Munich, Prien, Germany; Katherine A.

recovered from an eating disorder for at least 12 months Halmi, M.D., New York Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Medical College of

still reported higher levels of anxiety, harm avoidance, and Cornell University, White Plains, N.Y.; Allan S. Kaplan, M.D., and D.

Blake Woodside, M.D., Program for Eating Disorders, Toronto General

perfectionism than the healthy women in the community. Hospital, Toronto; Michael Strober, Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry

This suggests that anxiety symptoms are traits present in and Behavioral Science, University of California at Los Angeles; An-

drew W. Bergen, Ph.D., Biognosis, U.S., Inc., and Core Genotyping Fa-

most people with eating disorders, even if they do not cility, Advanced Technology Center, National Cancer Institute, Gaith-

meet DSM-IV criteria for anxiety disorders. ersburg, Md.; Scott Crow, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, University

2220 http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 161:12, December 2004

KAYE, BULIK, THORNTON, ET AL.

of Minnesota, Minneapolis; James Mitchell, M.D., Neuropsychiatric 13. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann

Research Institute, Fargo, N.D.; Alessandro Rotondo, M.D., Depart- RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obses-

ment of Psychiatry, Neurobiology, Pharmacology and Biotechnolo- sive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability.

gies, University of Pisa, Italy; Mauro Mauri, M.D., University of Pisa, It- Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011

aly; Pamela Keel, Ph.D., Department of Psychology, Harvard

University, Cambridge Mass.; Kelly L. Klump, Ph.D., Department of

14. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RD: STAI Manual. Palo

Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing; Lisa R. Lilenfeld, Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1970

Ph.D., Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta; 15. Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R: The dimensions of

and Wade H. Berrettini, M.D., Center of Neurobiology and Behavior, perfectionism. Cognit Ther Res 1990; 14:449–468

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. 16. Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR: A psychobiological

model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry

1993; 50:975–990

References 17. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences.

1. Godart NT, Flament MF, Perdereau F, Jeammet P: Comorbidity Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988

between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Int J 18. Pollice C, Kaye WH, Greeno CG, Weltzin TE: Relationship of

Eat Disord 2002; 32:253–270 depression, anxiety, and obsessionality to state of illness in

2. Walters EE, Kendler KS: Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syn- anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 1997; 21:367–376

dromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psy- 19. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshle-

chiatry 1995; 152:64–71 man S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prev-

3. Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves alence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States:

LJ: The structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychi-

for six major psychiatric disorders in women: phobia, general- atry 1994; 51:8–19

ized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bulimia, major depres- 20. Wittchen H-U, Essau CA: Epidemiology of anxiety disorders, in

sion, and alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:374–383 Psychiatry. Edited by Cooper AM. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott,

4. Deep AL, Nagy LM, Weltzin TE, Rao R, Kaye WH: Premorbid on- 1993, pp 1–25

set of psychopathology in long-term recovered anorexia ner- 21. Lilenfeld LR, Kaye WH, Greeno CG, Merikangas KR, Plotnicov K,

vosa. Int J Eat Disord 1995; 17:291–297 Pollice C, Rao R, Strober M, Bulik CM, Nagy L: A controlled fam-

5. Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Fear JL, Joyce PR: Eating disorders and ily study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: psychiatric

antecedent anxiety disorders: a controlled study. Acta Psychi- disorders in first-degree relatives and effects of proband co-

atr Scand 1997; 96:101–107 morbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:603–610

6. Godart NT, Flament MF, Lecrubier Y, Jeammet P: Anxiety disor- 22. Lask B, Bryant-Waugh R (eds): Anorexia Nervosa and Related

ders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: co-morbidity Eating Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence, 2nd ed. New

and chronology of appearance. Eur Psychiatry 2000; 15:38–45 York, Taylor & Francis, 2000

7. Silberg J, Bulik C: Developmental association between eating 23. Bruch H: Eating Disorders: Obesity, Anorexia Nervosa, and the

disorders and symptoms of depression and anxiety in juvenile Person Within. New York, Basic Books, 1973

twin girls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (in press)

24. Costello EJ, Angold A: Epidemiology, in Anxiety Disorders in

8. Kaye WH, Devlin B, Barbarich N, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Bacanu

Children and Adolescents. Edited by March J. New York, Guil-

S-A, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Kaplan AS, Strober M, Woodside DB,

ford, 1995, pp 109–124

Bergen AW, Crow S, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano G,

25. Piacentini J, Bergman RL: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in

Keel P, Plotnicov K, Pollice C, Klump KL, Lilenfeld LR, Ganjei JK,

children. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 23:519–533

Quadflieg N, Berrettini WH: Genetic analysis of bulimia ner-

vosa: methods and sample description. Int J Eat Disord 2004; 26. Halmi KA, Sunday SR, Klump KL, Strober M, Leckman JF, Fichter

35:556–570 M, Kaplan A, Woodside DB, Treasure J, Berrettini WH, Shabboat

9. First M, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: SCID Screen Patient M, Bulik CM, Kaye WH: Obsessions and compulsions in anor-

Questionnaire (SSPQ) and SCID Screen Patient Questionnaire— exia nervosa subtypes. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 33:308–319

Extended (SSPQ-X): Computer Program for Windows Software 27. Halmi KA, Sunday SR, Strober M, Kaplan A, Woodside DB, Fich-

Manual. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1999 ter M, Treasure J, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH: Perfectionism in an-

10. Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel P: The Eating Atti- orexia nervosa: variation by clinical subtype, obsessionality,

tudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psy- and pathological eating behavior. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:

chol Med 1982; 12:871–878 1799–1805

11. Fichter MM, Herpertz S, Quadflieg N, Herpertz-Dahlmann B: 28. Klump KL, Bulik CM, Pollice C, Halmi KA, Fichter MM, Berrettini

Structured Interview for Anorexic and Bulimic Disorders for WH, Devlin B, Strober M, Kaplan A, Woodside DB, Treasure J,

DSM-IV and ICD-10: updated (third) revision. Int J Eat Disord Shabboat M, Lilenfeld LR, Plotnicov KH, Kaye WH: Tempera-

1998; 24:227–249 ment and character in women with anorexia nervosa. J Nerv

12. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clini- Ment Dis 2000; 188:559–567

cal Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Research Version 29. Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Joyce PR, Carter FA: Temperament, char-

(SCID-I). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biomet- acter, and personality disorder in bulimia nervosa. J Nerv Ment

rics Research, 1996 Dis 1995; 183:593–598

Am J Psychiatry 161:12, December 2004 http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org 2221

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Theories On Eating Disorders and Its Correlations With Certain Personality TraitsDokument7 SeitenTheories On Eating Disorders and Its Correlations With Certain Personality TraitsBlack LettuceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Background - Eating Disorders General Info - Klein and Walsh 2003Dokument13 SeitenBackground - Eating Disorders General Info - Klein and Walsh 2003Jason WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Johnson 2002Dokument8 SeitenJohnson 2002Andrei OlariuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strong Thesis Statement On Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia and The MediaDokument4 SeitenStrong Thesis Statement On Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia and The Mediabk4pfxb7100% (1)

- Obesity Science Practice - 2023 - Pearl - Prevalence of Diagnosed Psychiatric Disorders Among Adults Who Have ExperiencedDokument7 SeitenObesity Science Practice - 2023 - Pearl - Prevalence of Diagnosed Psychiatric Disorders Among Adults Who Have ExperiencedMariana RochaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissociation, Abuse and The Eating Disorders: Evidence From An Australian PopulationDokument8 SeitenDissociation, Abuse and The Eating Disorders: Evidence From An Australian PopulationCoordinacionPsicologiaVizcayaGuaymasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leslie Et Al-2018-European Eating Disorders ReviewDokument10 SeitenLeslie Et Al-2018-European Eating Disorders ReviewGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating Disorders: Evaluation and Management: Key PointsDokument21 SeitenEating Disorders: Evaluation and Management: Key PointsCassandra BoduchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gangguan Makan Pada ObesitasDokument13 SeitenGangguan Makan Pada ObesitasDiaa NagitaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Overview of Binge-Eating Disorder 1Dokument15 SeitenRunning Head: Overview of Binge-Eating Disorder 1TatianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Body dissatisfaction in eating disordersDokument11 SeitenBody dissatisfaction in eating disordersKaren Posada GonzálezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Diagnostic and Treatment of Eating DisordersDokument10 SeitenThe Diagnostic and Treatment of Eating DisordersCAMILA OSPINA AYALANoch keine Bewertungen

- Anorexia Nervosa Handbook ChapterDokument17 SeitenAnorexia Nervosa Handbook ChapterOchaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Prevalence of Preadolescent Eating Disorders in The United StatesDokument4 SeitenThe Prevalence of Preadolescent Eating Disorders in The United StatesSukma YosrinandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development and Validation of The Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: A Brief Self-Report Measure of Anorexia, Bulimia, and Binge-Eating DisorderDokument9 SeitenDevelopment and Validation of The Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: A Brief Self-Report Measure of Anorexia, Bulimia, and Binge-Eating DisorderlinhamarquesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affect, Object Relation and Eating DisordersDokument10 SeitenAffect, Object Relation and Eating DisordersGloria KentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delaney2014Dokument11 SeitenDelaney2014ryselNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artículo 2Dokument7 SeitenArtículo 2danielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ReconceptuALIZING AnDokument8 SeitenReconceptuALIZING AnloloasbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neurobio of AnDokument15 SeitenNeurobio of AnThienanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Binge Eating Disorder ANNADokument12 SeitenBinge Eating Disorder ANNAloloasbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recent Advances in Developmental and Risk Factor ResearchDokument10 SeitenRecent Advances in Developmental and Risk Factor ResearchloloasbNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1002@eat 23366Dokument11 Seiten10 1002@eat 23366LucíaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personality Variables and 2018Dokument15 SeitenPersonality Variables and 2018Dhino Armand Quispe SánchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apego Transgeneracional y AnorexiaDokument9 SeitenApego Transgeneracional y AnorexiaadriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iaedp Research Summaries 3 FinalDokument6 SeitenIaedp Research Summaries 3 Finalapi-250253869Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ypi en Mujeres Con TcaDokument9 SeitenYpi en Mujeres Con TcaTatiana CastañedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recent Research On BulimiaDokument12 SeitenRecent Research On BulimialoloasbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mood Disorders Comorbidity in Obese Bariatric Patients The Role of The Emotional DysregulationDokument7 SeitenMood Disorders Comorbidity in Obese Bariatric Patients The Role of The Emotional DysregulationAlejandro Flores VelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dis Arfid PDFDokument10 SeitenDis Arfid PDFDalilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anorexia Nervosa Patient Centered CareDokument4 SeitenAnorexia Nervosa Patient Centered Careapi-315748471100% (1)

- Intl J Eating Disorders - 2020 - Hilbert - Psychometric Evaluation of The Eating Disorders in Youth Questionnaire When UsedDokument10 SeitenIntl J Eating Disorders - 2020 - Hilbert - Psychometric Evaluation of The Eating Disorders in Youth Questionnaire When UsedKariena PermanasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument8 SeitenAnnotated Bibliographyapi-665207114Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Family Based Intervention of Adolescents With Eating Disorders The Role of AssertivenessDokument1 SeiteA Family Based Intervention of Adolescents With Eating Disorders The Role of AssertivenessMaria SokoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gastrointestinal Problems Anxiety and DepressionDokument7 SeitenGastrointestinal Problems Anxiety and DepressionRama KhantoumaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impulsive and compulsive traits in eating disordersDokument8 SeitenImpulsive and compulsive traits in eating disordersTomás ArriazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S019188690100071X MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S019188690100071X MainTomás ArriazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - Which Factors Do Provoke Binge Eating An Exploratory Study in Eating Disorder Patients PDFDokument6 Seiten1 - Which Factors Do Provoke Binge Eating An Exploratory Study in Eating Disorder Patients PDFLaura CasadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge EatingDokument14 SeitenEating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge EatingmahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diet Quality in Persons With and Without Depressiv 2018 Journal of PsychiatrDokument7 SeitenDiet Quality in Persons With and Without Depressiv 2018 Journal of Psychiatrgiulia.santinNoch keine Bewertungen

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokument21 SeitenNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptJorge Andres AndradeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expressed Emotion in Eating Disorders Assessed via Self-ReportDokument10 SeitenExpressed Emotion in Eating Disorders Assessed via Self-ReportSerbanescu BeatriceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Case StudiesDokument12 SeitenClinical Case StudiesCristian DinuNoch keine Bewertungen

- AbstracteDokument4 SeitenAbstractegrymberg5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lent 2012 PDFDokument4 SeitenLent 2012 PDFBety Rafael PérezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper - Night - Eating - Syndrome - in - Young - Adults - de 17-7-2021Dokument8 SeitenPaper - Night - Eating - Syndrome - in - Young - Adults - de 17-7-2021Cristóbal Cortázar MorizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample of WorkDokument12 SeitenSample of Workapi-454173229Noch keine Bewertungen

- Etiology of Eating DisorderDokument5 SeitenEtiology of Eating DisorderCecillia Primawaty100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0015028211027075 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S0015028211027075 MainHanine El-DekmakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kelly2013 PDFDokument11 SeitenKelly2013 PDFditeABCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article of Eating DisordersDokument13 SeitenArticle of Eating Disordersapi-285693330Noch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence of Eating Disorders Among College Students in India: A Systematic ReviewDokument10 SeitenPrevalence of Eating Disorders Among College Students in India: A Systematic ReviewIJAR JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Update On Binge EatingDokument12 SeitenUpdate On Binge EatingloloasbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotion Regulation in BingeDokument5 SeitenEmotion Regulation in BingelauraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fishman Aug 06Dokument5 SeitenFishman Aug 06verghese17Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kuczmarski 2010Dokument7 SeitenKuczmarski 2010Alejandra LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- EATING DISORDERS Research ProposalDokument12 SeitenEATING DISORDERS Research ProposalKhushi KashyapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Purging Disorder: Recent Advances and Future Challenges: ReviewDokument7 SeitenPurging Disorder: Recent Advances and Future Challenges: ReviewMaximo Villanueva ZuñigaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bulimia Nervosa in Adolescents - Prevalence and Treatment ChallengesDokument6 SeitenBulimia Nervosa in Adolescents - Prevalence and Treatment ChallengesCamila CesteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Evolutionary Approach to Understanding and Treating Anorexia Nervosa and Other Eating ProblemsVon EverandAn Evolutionary Approach to Understanding and Treating Anorexia Nervosa and Other Eating ProblemsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regulated Professions AustraliaDokument8 SeitenRegulated Professions AustraliaAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Learning TheoryDokument6 SeitenSocial Learning TheoryAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bandura - Sociocognitive Self-Regulatory Mechanisms Governing Transgressive BehaviourDokument11 SeitenBandura - Sociocognitive Self-Regulatory Mechanisms Governing Transgressive Behaviournikatie4846Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gene Envirmonment Interaction in Prediction of Behavior Inhibition in Middle ChildhoodDokument6 SeitenGene Envirmonment Interaction in Prediction of Behavior Inhibition in Middle ChildhoodAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotional Intelligence, Locus of Control and PersonalityDokument62 SeitenEmotional Intelligence, Locus of Control and PersonalityAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bernstein PDFDokument15 SeitenBernstein PDFVirgílio BaltasarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suicidality in BDDDokument15 SeitenSuicidality in BDDAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written Emotional ExpressionDokument11 SeitenWritten Emotional ExpressionAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uso de Terapias Alternativas en MexicoDokument10 SeitenUso de Terapias Alternativas en MexicoAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written Emotional ExpressionDokument11 SeitenWritten Emotional ExpressionAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Encuesta Nacional Epidemiologia PsiquiatricaDokument16 SeitenEncuesta Nacional Epidemiologia Psiquiatricaapi-3707147100% (2)

- DSM-V Review of Generalized Anxiety Disorder Classification OptionsDokument14 SeitenDSM-V Review of Generalized Anxiety Disorder Classification OptionsAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attentionalbias To Threat and Emotional Response To Biological Challenge PDFDokument19 SeitenAttentionalbias To Threat and Emotional Response To Biological Challenge PDFAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Depression, Alexithymia and Eating Disorders PDFDokument11 SeitenDepression, Alexithymia and Eating Disorders PDFAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Cortisol On Memory in Women With BPDDokument12 SeitenEffect of Cortisol On Memory in Women With BPDAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparison of Insight in BDD and OCDDokument14 SeitenA Comparison of Insight in BDD and OCDAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating-Disordered Patients With Without Self-Injurious Behaviors - A Comparison of Psychopathological FeaturesDokument19 SeitenEating-Disordered Patients With Without Self-Injurious Behaviors - A Comparison of Psychopathological FeaturesAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developmental Pathways in ODD and CD (1-2p)Dokument13 SeitenDevelopmental Pathways in ODD and CD (1-2p)Alicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ANSIEDAD Y DEPRESIÓN, EL PROBLEMA de Su DiferenciaciónDokument9 SeitenANSIEDAD Y DEPRESIÓN, EL PROBLEMA de Su DiferenciaciónjuaromerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catharsis, Rumination, Distraction, Anger and Aggressive Responding PDFDokument8 SeitenCatharsis, Rumination, Distraction, Anger and Aggressive Responding PDFAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- APA Ethics Code PDFDokument18 SeitenAPA Ethics Code PDFAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Craske - PD Review For DSM 5Dokument20 SeitenCraske - PD Review For DSM 5Alicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alexithymia, Eating Behavior and Self EsteemDokument8 SeitenAlexithymia, Eating Behavior and Self EsteemAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDDokument9 SeitenAbnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDDokument9 SeitenAbnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

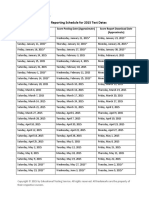

- Score Reporting Schedule Test DatesDokument3 SeitenScore Reporting Schedule Test DatesAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents Implications For DSM 5 PDFDokument44 SeitenAnxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents Implications For DSM 5 PDFAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colegio Ontario SupervisionDokument6 SeitenColegio Ontario SupervisionAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colegio Ontario CuotasDokument1 SeiteColegio Ontario CuotasAlicia SvetlanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The 4 Types of Eating: Fuel, Joy, Fog and StormDokument6 SeitenThe 4 Types of Eating: Fuel, Joy, Fog and StormCRestine Joy Elmido Montero100% (2)

- Comorbid Drug Use Disorders and Eating Disorders - A Review of Prevalence StudiesDokument12 SeitenComorbid Drug Use Disorders and Eating Disorders - A Review of Prevalence StudiesJhon QuinteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engl102 Final PaperDokument13 SeitenEngl102 Final Paperapi-317396471Noch keine Bewertungen

- HOME SCIENCE (Code No. 064) : ObjectivesDokument6 SeitenHOME SCIENCE (Code No. 064) : Objectivesapi-243565143Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case 1Dokument25 SeitenCase 1hamshiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating DisordersDokument15 SeitenEating DisordersЯ мусурманNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self-Compassion and Eating Disorder Symptons in AdolescentDokument162 SeitenSelf-Compassion and Eating Disorder Symptons in AdolescentMaria AlejandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dflex 2011Dokument7 SeitenDflex 2011Carla CascianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLIL - Unit Plan - You Are What You Eat - Alberto LanzatDokument4 SeitenCLIL - Unit Plan - You Are What You Eat - Alberto Lanzatlanzat1Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Is An Eating Disorder?: Anorexia Nervosa: Anorexia Nervosa Is Self-Imposed Starvation. AnorexiaDokument4 SeitenWhat Is An Eating Disorder?: Anorexia Nervosa: Anorexia Nervosa Is Self-Imposed Starvation. AnorexialuqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrated Case StudyDokument10 SeitenIntegrated Case Studyapi-483148847Noch keine Bewertungen

- 70 Reasons NOT To EatDokument3 Seiten70 Reasons NOT To Eatchrisdrown67% (3)

- Understanding Your Eating Overcoming Disordered Eating From Anorexia To ObesityDokument266 SeitenUnderstanding Your Eating Overcoming Disordered Eating From Anorexia To ObesitynervesawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating Disorders and The Internet: The Therapeutic PossibilitiesDokument7 SeitenEating Disorders and The Internet: The Therapeutic PossibilitiesPaula SalidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating DisorderDokument65 SeitenEating DisorderVanessa MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teen ProblemsDokument5 SeitenTeen Problemsapi-442460902Noch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1016@j Bodyim 2018 08 009 PDFDokument6 Seiten10 1016@j Bodyim 2018 08 009 PDFvirnathalia saniparNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individuation WomenDokument70 SeitenIndividuation WomenCarles Fondevila RomeuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes and Effects of Anorexia NervosaDokument9 SeitenCauses and Effects of Anorexia NervosaBruce Wayne100% (1)

- Informative Outline SPCDokument2 SeitenInformative Outline SPCAnonymous madidqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anorexia Nervosa PDFDokument6 SeitenAnorexia Nervosa PDFmist73Noch keine Bewertungen

- El DSM-5-TR Un Análisis 101. Una Revisión Ejecutiva Completa de Los Espectros Clasificados en El Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de Los Trastornos Mentales, Quinta Edición, Revisión Del Texto - Scientia Media GroupDokument454 SeitenEl DSM-5-TR Un Análisis 101. Una Revisión Ejecutiva Completa de Los Espectros Clasificados en El Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de Los Trastornos Mentales, Quinta Edición, Revisión Del Texto - Scientia Media GroupHenry RuedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 5 UtsDokument29 SeitenModule 5 Utsdwill cagatanNoch keine Bewertungen

- OT and Eating DysfunctionDokument1 SeiteOT and Eating DysfunctionMCris EsSemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Based Treatment For Eating DisorderDokument2 SeitenFamily Based Treatment For Eating DisorderHana Chan100% (1)

- Adolescents and Body ImageDokument4 SeitenAdolescents and Body ImageSari Yuli AndariniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating Disorder RecoveryDokument4 SeitenEating Disorder RecoveryDevotedrecoveryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gormally 1982Dokument9 SeitenGormally 1982lola.lmsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating Disorders LP 2013Dokument28 SeitenEating Disorders LP 2013muscalualina100% (1)

- Eating Disorders: Dr. Shastri MotilalDokument26 SeitenEating Disorders: Dr. Shastri MotilalSaraNoch keine Bewertungen