Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Newsletter July 2019

Hochgeladen von

Brittany Etheridge0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

46 Ansichten7 SeitenNewsletter July 2019

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenNewsletter July 2019

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

46 Ansichten7 SeitenNewsletter July 2019

Hochgeladen von

Brittany EtheridgeNewsletter July 2019

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 7

UGA Cotton Team Newsletter

July, 2019

Variety Selection in Georgia, Why Our Best Choices are

Sometimes a Compromise…(Whitaker)

Weather is a big factor that all cotton producers have to consider during planting season. In Georgia,

rainfall is almost always limited at some point and our producers are some of the most experienced

in “making it work”.

This year was no exception as conditions deteriorated quickly, where rainfall became increasingly

rare anywhere across the state between May 14th and June 3rd. On top of the dry weather, air

temperatures soared between May 26th and June 3rd. This left conditions exceedingly poor for most

of the state and producers who were finishing planting during this time faced an extremely difficult

task.

Ultimately, many (if not most) fields which were planted during the window between May 26th and

June 3rd ended up having to be replanted.

Replanting occurs on a small percentage of our crop each year, but this situation was unique as stands

were inadequate in fields where producers did everything right and used all the tricks and tools we

have to help emergence during less than optimum conditions.

Most of the time when a cotton field has to be replanted there is some issue that we can point to

which helps explain what happened and give hints to what could be done differently next time.

This time I visited growers across the state with stand issues that occurred during this window and

time after time there was not obvious issue that would explain why we failed at getting a stand. The

only common thing was that germination seemed to slow down and seedlings seemed to “run out of

gas”, which was backwards to the common idea that emergence is faster as soil temperatures

rise. We did measure soil temperatures in a lot of fields during this window and documented

temperatures at 1” below the surface well over 100° F in wet soil and over 120° F in drier soil. We’ve

seen soil temperatures this high many times before, but rarely see it last over a week.

Looking back, there was quite a bit of literature that provided evidence to indicate that cotton

emergence slows and is ultimately limited when soil temperatures rise above 95° F. Specifically, that

research has shown that temperatures even slightly over 95° F can significantly limit the emergence

process. There are several physiological processes that are negatively affected when temperatures

rise above 100° F, yet the work ultimately suggests that the seedling emergence process is not

efficient and the process slows, in some cases to the point where seedlings don’t make it to the soil

surface prior to running out of energy (ending in seedling death).

Some of this temperature related cotton seedling work has indicated that seedling vigor, or inherent

differences in vigor, can significantly impact how much these adverse conditions play a role in

emergence. In Georgia, most of our best variety choices are considered to be extremely small seeded

varieties. We know that seed size is very closely correlated to seedling vigor, as seed size decreases,

vigor decreases (and vice versa). This is not something that is seed company or brand specific, but

rather simply a function of energy storage. So, it should not be surprising that when a larger seeded

variety is planted next to a smaller seeded variety, when conditions are poor, one could see

differences in overall emergence.

In hindsight, we had some extremely poor weather conditions for almost half of our planting window

and almost impossible conditions during a particular week. Knowing what we know now, there were

obvious situations where a bag of seed with better vigor could have made the difference in getting a

stand. However, making variety decisions only based on vigor in Georgia could leave yield potential

on the table.

With weather predictions becoming increasingly better, we may be able to know when this will

happen again. However, we still need to have better information on how seed from a particular bag

will respond. Currently, we only know that seed we buy has adequate vigor to emerge in a standard

germination test, which is conducted with temperatures up to only 86° F. We can also make

inferences based on seed size and in some cases have the results of a cool germination test.

As much as producers pay for cotton seed, I think it’s fair to say that we need better information on

what happens when soil temperatures rise to risky levels. There are other germination tests out

there, specifically an accelerated aging test, which may provide key information needed to help make

the decision on how to choose a variety when seedling vigor becomes increasingly important. More

times than not, we plant cotton in soil temperatures that are well above 86° F and testing information

that reflects that could make all the difference in whether or not we get an adequate stand of cotton

in early enough to maximize yields.

This article is certainly not meant to challenge current germination testing procedures or to say that

growers should make rash decisions based on recent experiences, but rather to encourage our

industry to strive to provide Georgia producers with variety decisions which don’t make us settle on

sometimes “lower than needed” vigor. In the meantime, we need to work to ensure that we have the

best information possible to make good decisions when these scenarios occur again in the future.

After all that, let’s hope for a successful 2019 cotton crop. Even though much of the crop suffered

early on, the weather has made a turn for the better in most places and with a favorable August we

could make an extremely good if not record crop.

For any question or issue with your cotton crop, be sure to reach out to your local UGA County

Extension agent.

Considerations for PGRs in 2019 (Freeman)

Although plant growth regulators have been used for many years in Georgia, there is still much

confusion about what they actually do. Contrary to what many may think, mepiquat does not cause

the plant to produce more flowers or bolls. What is can do is limit the amount of vegetative

growth which may enhance fruit retention in lower nodes. This early node fruit retention will

help with “earliness” or a quicker maturation of the crop, which tends to benefit later planted

cotton more so than early planted cotton. Excessive vegetative growth can also decrease harvest

efficiency, decrease coverage of insecticides and fungicides below the canopy, decrease below

canopy airflow (which may increase risk of foliar diseases and boll rot), and excessive shading

of the lower canopy which can impact the fiber quality of bolls of the lower portion of the plant.

There are several key factors that play a role in a crop’s need for PGR applications. Current crop

condition should always be the most important factor considered as mepiquat applications to

stressed or stunted cotton may have negative impacts on the crop. Checking internode lengths

between the 4th and 5th nodes from the top of the plant is a great way to determine the crop’s

current condition and growth potential. If this internode measures 3” or greater mepiquat

application is warranted.

Other factors should also be considered. What is the vegetative growth history of the particular

field? If a field is known for growing rank cotton, higher rates and/or more applications may be

necessary. Considerable thought should also be given to the crop’s fertility program. If nitrogen

is excessive (include all N forms: poultry litter, legume cover crops, standard fertilizer) the

vegetative growth potential may also warrant additional mepiquat. Planting date should also be

considered, as later planted cotton will often realize a greater benefit from mepiquat applications

compared to earlier planted cotton. Additionally, in 2019, special attention should be paid to

cotton that was planted in mid to late May. Although not technically “late” this cotton most likely

received excessive stress from intense heat, dry weather, and thrips and maturity was most

likely delayed. This cotton should be managed as if it were planted late and a more aggressive

PGR program should be applied.

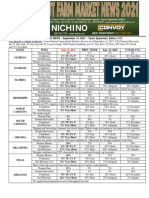

One final consideration is cotton variety. Each variety’s vegetative growth potential and

response to PGR applications is unique. Below is a chart that is to be used as a guide for PGR

needs by variety. It is

important to

understand that

although variety plays a

large role in the overall

PGR program, the other

factors must always be

considered. For

example, a variety in

the lower growth

potential group will

become rank with

excessive nitrogen and

irrigation/rainfall

occur. For me

information on rates

and timings please contact your local UGA Extension Agent.

Layby Directed and Hooded Row Middle Applications of Engenia,

FeXapan, and XtendiMax Approved for Georgia Cotton Growers.

(Culpepper, UGA & Gray, GDA)

A state Section 24(c) Special Local Need Label has been approved by the U.S. EPA and Georgia

Department of Agriculture (GDA) allowing directed and hooded applications for Engenia, FeXapan,

and XtendiMax.

Topical applications of Engenia, FeXapan, and XtendiMax in tolerant cotton can only be made through

60 days after planting; thus, directed labels will offer an extended use of this herbicide chemistry.

Directed applications should provide improved weed control through better coverage and, even

more importantly, will offer a more effective resistance management approach when managing

Palmer amaranth as tank mixtures with more effective herbicides such as diuron may be used. One

must have the label in hand and follow it precisely. Below are a few details form the label.

Label Information:

1. Applicators must have attended (and registered) a 2019 Using Pesticide Wisely training and must

be a certified applicator.

2. Each applicator must have the label of the product they decide to use in hand during the

application. Labels can be obtained at the GDA web site: http://agr.georgia.gov/24c.aspx. Once on

the website, click “go to dicamba page”; then select the “24C label” for the product of choice. These

labels will provide detailed information needed to make a proper application.

3. Hooded applications: May use any standard spray tip as long as droplets are coarse or larger in

size (>341 microns vmd). Hoods must remain in contact with soil while making the application. A

maximum of 6 mph sprayer speed. Tolerant cotton must be at least 15 inches in height at time of

application.

4. Directed Layby applications: May use any standard spray tip as long as droplets are coarse or

larger in size (>341 microns vmd). Spray release point must not be more than 10 inches from the soil

and the cotton must be at least 20 inches in height. Spray tip must be angled downward toward the

soil making sure no spray droplets remain in the air. A maximum of 6 mph sprayer speed is required.

5. Engenia, FeXapan, and XtendiMax can be mixed with any other labeled cotton herbicides approved

on the manufactures websites (www.engeniatankmix.com;

www.xtendimaxapplicationrequirements.com; www.fexapanapplicationrequiremetns.dupont.com).

Do not mix with AMS or glufosinate products (Liberty, etc.)

A few questions and answers:

1. Do hood or layby applications reduce the buffer requirements currently required for topical

applications? NO!

2. Do hood or layby applications increase the application window for these dicamba formulations? Yes.

Hooded or directed applications can be made in-crop up until 7 days pre-harvest for cotton.

First Bloom is Here; Don’t Miss Opportunity to Protect the Crop

and Maximize Yields (Kemerait)

Three foliar diseases are expected to affect cotton production in Georgia this year and all of them may

become more apparent in July. One of them, Stemphylium leaf spot, is likely to be more problematic

when hot and dry conditions have prevailed at some point earlier in the season. Target spot is likely

to be problematic in fields with good growth and good yield potential and where conditions are warm

and humid. Areolate mildew typically appears during the second half of the growing season and, like

target spot, is favored by rainfall and humidity.

It is important to be able to differentiate these diseases of cotton because effective management

options are different. Stemphylium leaf spot is associated with a deficiency in potassium in the cotton

plant. This deficiency may occur because the soil is deficient in potassium or because the roots have

not been able to translocate sufficient potassium from the soil. This could be the result of drought

where water was not available to move the potassium into the plant, or it may occur in areas where

plant-parasitic nematodes have damaged the roots and inhibited nutrient uptake. Severe symptoms

of Stemphylium leaf spot often occur in the sandier areas of a field, whether because nutrients are

more easily leached from those areas, because drought is felt more intensely there, or because sting

and root-knot nematodes are more commonly found in sandier areas of a field. Plants affected by

Stemphylium leaf spot show poor growth and significant reddening and yellowing in the foliage.

Spots are found on leaves throughout the canopy, and especially at the top of the plant. Centers of

the spots are papery and bleached-gray; often having a “shot-hole” appearance. As Stemphylium leaf

spot is the result of a potassium deficiency, fungicides are generally ineffective in managing this

disease.

Target spot, caused by the fungal pathogen Corynespora cassiicola, is a disease of cotton when the

crop has a dense canopy of leaves and high yield potential. Target spot is especially problematic

where there are extended periods of leaf wetness, either because of frequent rain showers or where

a dense leaf canopy and high humidity reduce airflow and keep leaves in the lower part of the plant

from drying. Target spot can also be a problem in fields with excess nitrogen. Target spot is rarely

found on poor-growth cotton or where Stemphylium leaf spot occurs. Target spot begins deep in the

lower leaf canopy and can move quickly up the plants causing significant premature defoliation when

conditions are favorable. The development of target spot is quite variable as it is largely driven by a

disease-favorable environment. The first week of bloom is an excellent time to begin scouting for

target spot, as first bloom often corresponds with a time when the canopy is closing.

Judicious use of fungicides can help to protect yield and maximize profit for growers. As target spot

may not appear in every field every year and, therefore, not all fields will need to be treated.

However, where conditions are favorable and target spot appears early enough in the season,

growers can increase their yield by 200 lb lint/A, or more, with use of fungicides. Growers should

consider use of a fungicide for management of target spot as early as the first week of bloom.

However, if the disease is not present, growers can safely delay application if they are willing to scout

for onset of the disease. The single most important timing for application is the 3 rd week of bloom;

multiple fungicide applications may be necessary to protect the crop and yield. The most effective

fungicide to date is Priaxor. Headline and Quadris are effective as well. Target spot is nearly

impossible to manage once significant defoliation occurs. Growers should not need to protect their

crop after the 6th week of bloom.

Prior to the 2017 growing season, I rarely observed areolate mildew (Ramularia) except later in the

season in southeastern Georgia. In both 2017 and 2018 this disease was observed in cotton across

the Coastal Plain and did, I believe, because some yield loss. This is based on results of field trials

conducted by Stephanie Hollifield (Brooks Co. Extension Agent) and Jeremy Kichler (Colquitt Co.

Extension Agent). Basically, if areolate mildew appears within 4 weeks of anticipated defoliation, I

wouldn’t worry about it. If areolate mildew shows up earlier, and the cotton crop looks to have

reasonable yield potential, I would protect it with a fungicide. If the disease is not detected until

significant defoliation has occurred, then there is little chance of protecting yield with a too-late-

applied fungicide.

Areolate mildew is easier to control than is target spot. This is because the fungus is much more

exposed (it looks a lot like powdery mildew) to the fungicide and because it is less confined to the

lower canopy. Use of Priaxor will protect the crop against target spot and areolate mildew, as will

Headline and Quadris. Arolate mildew alone can be managed with timely applications of any of these

fungicides; however azoxystrobin has been generally effective to date.

Because of crop development, it is important during July to consider protecting a cotton crop with

fungicides. There are 5 steps. First, scout the field and determine what diseases are present. Second,

decide on management options. If the disease is Stemphylium leaf spot, then a fungicide will not

control the disease. If the disease is target spot or areolate mildew, then a fungicide could be

beneficial. Third, consider the crop before applying the fungicide. Does the field have a reasonable

chance for good yields? How advanced is the disease? Fourth, decide on a fungicide. Priaxor is the

best fungicide for management of target spot, though other fungicides, to include Headline and

Quadris are also good. These fungicides will control areolate mildew as well, though areolate mildew

is easier to control than is target spot. Fifth, timing of fungicide application is critical. If applied too

late, there will be little hope for controlling the disease and protecting yield.

Cotton Aphid Management- We Need the FUNGUS! (Roberts)

Cotton aphid is a fairly consistent and predictable pest of cotton in Georgia. Aphids will typically

build to moderate to high numbers and eventually crash due to a naturally occurring fungus,

Neozygites fresenii. This fungal epizootic typically occurs in late June or early July depending on

location. Once the aphid fungus is detected in a field (gray fuzzy aphid cadavers) we would expect

the aphid population to crash within a week. Over the weekend we received several reports of

fields crashing due to the fungus in the southernmost Georgia. Typically the fungus starts in the

southernmost counties of southwest Georgia and moves north and east in time.

Aphids feed on plant juices and secrete large amounts of “honeydew”, a sugary liquid. The loss of

moisture and nutrients by the plants has an adverse effect on growth and development. This stress

factor can be reduced with the use of an aphid insecticide. However, research conducted in Georgia

fails to consistently demonstrate a positive yield response to controlling aphids. Invariably, some

fields probably would benefit from controlling aphids during some years. Prior to treatment, be sure

there is no indication of the naturally occurring fungus in the field or immediate vicinity. Also

consider the levels of stress plants are under, vigorous and healthy plants are able to tolerate more

aphid damage than stressed plants.

A closer look at a cotton aphid infested

leaves and identification of the cotton

aphid fungus (Neozygites fresenii) and

other interesting things:

Figure 1. Cotton aphid fungus present and

aphids are crashing. Note the gray fuzzy

aphids which is indicative of the fungus.

Also note the aphid cast skins which are

white in color; aphids molt or shed their

exoskeleton (skin) as they grow.

Figure 2. Zoomed in on a fungus

killed winged aphid. See the

fungal growth and sporulation.

Figure 3. No fungus in this infested

terminal. The brown balls (aphid

mummies) are aphids which have been

parasitized by a small wasps. Also lots of

aphid cast skins in this pic.

Figure 4. Four leaf cotton with a heavy

aphid infestation. Note the high number

of winged aphids which invaded this field.

If aphids slow seedling growth that may

delay maturity which could be an issue on

late planted cotton. No fungal infected

aphids in this pic.

Stink Bug Update: Observations and

correspondence with agents, scouts, and

consultants suggest that stink bug

numbers are higher than we have

observed in recent years. Once plants

begin setting bolls begin monitoring for

internal damage. Scout bolls

approximately the diameter of a quarter. Bolls of this size are easy to squash between your thumb

and forefinger and are the preferred size for stink bugs to feed. Bolls with callous growths (warts)

and/or stained lint are considered damaged. Use the dynamic threshold based on week of bloom to

make treatment decisions. During the first week or ten days of bloom when bolls have not reached

the size of a quarter, sample the largest bolls available. Stink bugs will feed on small bolls when 10-

12 day old bolls (quarter sized) are not present. Feeding on small bolls will cause them to be shed by

the plant.

Important Dates

Expo Field Day – July 25th

Midville Field Day – August 14th

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- CQ Perspectives Jan 2005Dokument4 SeitenCQ Perspectives Jan 2005Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- CQ Perspectives Jan 2010Dokument4 SeitenCQ Perspectives Jan 2010Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- eGuide-How-No-Tilling-Can-Help-Growers-Ease-Flooding-Issues REEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEDokument8 SeiteneGuide-How-No-Tilling-Can-Help-Growers-Ease-Flooding-Issues REEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEkerateaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On Corn ProductionDokument6 SeitenResearch Paper On Corn Productionfvj8675e100% (1)

- Grain Sorghum Production HandbookDokument32 SeitenGrain Sorghum Production HandbookSiti Norihan AGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agronomic PrinciplesDokument14 SeitenAgronomic PrinciplesRebwar OsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cotton Presentation 3Dokument9 SeitenCotton Presentation 3Izukanji kayoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CQ Perspectives Sep 2007Dokument4 SeitenCQ Perspectives Sep 2007Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seed Selection PDFDokument4 SeitenSeed Selection PDF小次郎 佐々木Noch keine Bewertungen

- Factors That Affecting Farm Life and See Storage and Treatment (Erron John F CastroDokument6 SeitenFactors That Affecting Farm Life and See Storage and Treatment (Erron John F CastroEJ CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nzgrassland Publication (Artículo)Dokument7 SeitenNzgrassland Publication (Artículo)Eduardo PérezNoch keine Bewertungen

- CQ Perspectives Jul 2003Dokument4 SeitenCQ Perspectives Jul 2003Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peanut Production Guide 2020Dokument24 SeitenPeanut Production Guide 2020nazeer.traytonNoch keine Bewertungen

- PEANUT MARKETING NEWS - August 24, 2020 - Tyron Spearman, EditorDokument1 SeitePEANUT MARKETING NEWS - August 24, 2020 - Tyron Spearman, EditorMorgan IngramNoch keine Bewertungen

- HOW To GROW NO TILL COTTONmspmctn9603 Plant Materials Nrcs UsdaGOVDokument5 SeitenHOW To GROW NO TILL COTTONmspmctn9603 Plant Materials Nrcs UsdaGOVJdoe3399Noch keine Bewertungen

- G D82 HuceDokument26 SeitenG D82 HucennvbnbvnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consider These 9 TipsDokument2 SeitenConsider These 9 TipsastuteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aula06 2 Grain DryersDokument27 SeitenAula06 2 Grain DryersHarish KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wheat Production HandbookDokument46 SeitenWheat Production HandbookAnonymous im9mMa5Noch keine Bewertungen

- CQ Perspectives Oct 2001Dokument6 SeitenCQ Perspectives Oct 2001Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Variability, SCF, and Corn Farming in Isabela, Philippines: A Farm and Household Level AnalysisDokument66 SeitenClimate Variability, SCF, and Corn Farming in Isabela, Philippines: A Farm and Household Level AnalysisAce Gerson GamboaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural PracticesDokument3 SeitenCultural PracticesrexazarconNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agricultural: AlternativesDokument12 SeitenAgricultural: AlternativesmealysrNoch keine Bewertungen

- p1828 WebDokument36 Seitenp1828 WebMohammed PastawyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crop Production and Management Farm ReportDokument4 SeitenCrop Production and Management Farm Reportapi-252447938Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis On GM CropsDokument4 SeitenThesis On GM CropsAudrey Britton100% (3)

- Cover Crops For Sustainable Crop Rotations: Topic Room SeriesDokument4 SeitenCover Crops For Sustainable Crop Rotations: Topic Room Seriespoz9024Noch keine Bewertungen

- Vineyard Yield Estimation: Brittany Komm, Former Graduate Research Assistant, WSUDokument11 SeitenVineyard Yield Estimation: Brittany Komm, Former Graduate Research Assistant, WSUPutchong SaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grazing Cover Crops: A How-To Guide: Developed in Partnership WithDokument32 SeitenGrazing Cover Crops: A How-To Guide: Developed in Partnership Withpoz9024Noch keine Bewertungen

- Flood Effects: Responding To Late Season FloodingDokument4 SeitenFlood Effects: Responding To Late Season Floodingcool908Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cantaloupe Production GuideDokument6 SeitenCantaloupe Production GuidemasoudbaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSU Improving Carrot Quality - Brainard Final Report 346517 7Dokument10 SeitenMSU Improving Carrot Quality - Brainard Final Report 346517 7EscarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sunflower Production Guidelines for Northern NSWDokument8 SeitenSunflower Production Guidelines for Northern NSWFaiza BilalNoch keine Bewertungen

- CQ Perspectives Aug 2002Dokument4 SeitenCQ Perspectives Aug 2002Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- 204 ORO - Nursery Management Participant Material Module 1Dokument20 Seiten204 ORO - Nursery Management Participant Material Module 1Yared AlemnewNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06crop1 PDFDokument14 Seiten06crop1 PDFmichaella ann arcayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Planting Corn For Grain in TennesseeDokument3 SeitenPlanting Corn For Grain in TennesseeDbaltNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crop Rotation Guide for Vegetable FarmsDokument3 SeitenCrop Rotation Guide for Vegetable FarmsChing QuiazonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rice Objective Yield Feasibility StudyDokument7 SeitenRice Objective Yield Feasibility StudyMannieNadateCatrizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corn Production ManagementDokument19 SeitenCorn Production ManagementGelly Anne DomingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEED SELECTION AND GINSENG CULTUREDokument4 SeitenSEED SELECTION AND GINSENG CULTUREronalit malintadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organic Tomato ATTRA PDFDokument16 SeitenOrganic Tomato ATTRA PDFgarosa70Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On GM CropsDokument11 SeitenLiterature Review On GM Cropsjwuajdcnd100% (1)

- CQ Perspectives Sep 2004Dokument4 SeitenCQ Perspectives Sep 2004Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Manufacture of Tomato Products: Including whole tomato pulp or puree, tomato catsup, chili sauce, tomato soup, trimming pulpVon EverandThe Manufacture of Tomato Products: Including whole tomato pulp or puree, tomato catsup, chili sauce, tomato soup, trimming pulpNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Transition To Regenerative AgricultureDokument9 SeitenHow To Transition To Regenerative AgricultureharleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- PEANUT MARKETING NEWS - April 13, 2020 - Tyron Spearman, EditorDokument1 SeitePEANUT MARKETING NEWS - April 13, 2020 - Tyron Spearman, EditorBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cover Crops For Field Crop Systems: Fact Sheet 93 Agronomy Fact Sheet SeriesDokument2 SeitenCover Crops For Field Crop Systems: Fact Sheet 93 Agronomy Fact Sheet SeriesGregory BakasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise 5 Crop Suitability Assessment RepairedDokument5 SeitenExercise 5 Crop Suitability Assessment RepairedJessa PalbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strawberry ProductionDokument8 SeitenStrawberry ProductionQuang Ton ThatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region Ix, Zamboanga Peninsula Schools Division of Zamboanga Del NorteDokument6 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region Ix, Zamboanga Peninsula Schools Division of Zamboanga Del NorteJam Hamil AblaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CQ Perspectives Nov 2004Dokument4 SeitenCQ Perspectives Nov 2004Crop QuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top pecan varieties for Georgia orchardsDokument8 SeitenTop pecan varieties for Georgia orchardsErnesto Berciano GüelfoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kentucky Pest News, March 26, 2013Dokument3 SeitenKentucky Pest News, March 26, 2013awpmaintNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crop PatternDokument4 SeitenCrop PatternAshirwad SinghalNoch keine Bewertungen

- PeanutDokument45 SeitenPeanutSaumya SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hanks 1991Dokument24 SeitenHanks 1991IcsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nedry Be An Production Guide 2017Dokument11 SeitenNedry Be An Production Guide 2017dmsngc55njNoch keine Bewertungen

- RS EffectOfPGRStrategiesDokument2 SeitenRS EffectOfPGRStrategiesFurqanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1. Site SelectionDokument10 SeitenModule 1. Site SelectionGENESIS MANUELNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 159 21Dokument1 Seite12 159 21Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- One Broker Reported ThatDokument1 SeiteOne Broker Reported ThatBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cotton Marketing NewsDokument1 SeiteCotton Marketing NewsBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cotton Marketing NewsDokument2 SeitenCotton Marketing NewsBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cotton Marketing NewsDokument1 SeiteCotton Marketing NewsBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Said Jeremy Mayes, General Manager For American Peanut Growers IngredientsDokument1 SeiteSaid Jeremy Mayes, General Manager For American Peanut Growers IngredientsBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLICK HERE To Register!Dokument1 SeiteCLICK HERE To Register!Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part of Our Local Economy With Peanuts and PecansDokument1 SeitePart of Our Local Economy With Peanuts and PecansBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breakfast Luncheon: Peanut Marketing News - November 8, 2021 - Tyron Spearman, Editor (144) Post Harvest Meeting Kick OffDokument1 SeiteBreakfast Luncheon: Peanut Marketing News - November 8, 2021 - Tyron Spearman, Editor (144) Post Harvest Meeting Kick OffBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- October 24, 2021Dokument1 SeiteOctober 24, 2021Brittany Etheridge100% (1)

- 2021 USW Crop Quality Report EnglishDokument68 Seiten2021 USW Crop Quality Report EnglishBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. PEANUT EXPORTS - TOP 10 - From USDA/Foreign Agricultural Service (American Peanut Council)Dokument1 SeiteU.S. PEANUT EXPORTS - TOP 10 - From USDA/Foreign Agricultural Service (American Peanut Council)Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 128 21Dokument1 Seite10 128 21Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- October 10, 2021Dokument1 SeiteOctober 10, 2021Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- October 17, 2021Dokument1 SeiteOctober 17, 2021Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- NicholasDokument1 SeiteNicholasBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1,000 Acres Pounds/Acre TonsDokument1 Seite1,000 Acres Pounds/Acre TonsBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Agricultural Supply and Demand EstimatesDokument40 SeitenWorld Agricultural Supply and Demand EstimatesBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shelled MKT Price Weekly Prices: Same As Last WeekDokument1 SeiteShelled MKT Price Weekly Prices: Same As Last WeekBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- October 3, 2021Dokument1 SeiteOctober 3, 2021Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 127 21Dokument1 Seite10 127 21Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winter-Conference - HTML: Shelled MKT Price Weekly PricesDokument1 SeiteWinter-Conference - HTML: Shelled MKT Price Weekly PricesBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dairy Market Report - September 2021Dokument5 SeitenDairy Market Report - September 2021Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sept. 19, 2021Dokument1 SeiteSept. 19, 2021Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sept. 26, 2021Dokument1 SeiteSept. 26, 2021Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shelled MKT Price Weekly Prices: Same As Last Week 7-08-2021 (2020 Crop) 3,174,075 Tons, Up 3.0 % UP-$01. CT/LBDokument1 SeiteShelled MKT Price Weekly Prices: Same As Last Week 7-08-2021 (2020 Crop) 3,174,075 Tons, Up 3.0 % UP-$01. CT/LBBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2021 Export Update - Chinese Future Prices Have Gotten Weaker. This Is Not SurprisingDokument1 Seite2021 Export Update - Chinese Future Prices Have Gotten Weaker. This Is Not SurprisingBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sept. 12, 2021Dokument1 SeiteSept. 12, 2021Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- YieldDokument1 SeiteYieldBrittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Export Raw-Shelled Peanuts (MT) In-Shell Peanuts (MT) : Down - 11.8 % Down - 16.1%Dokument1 SeiteExport Raw-Shelled Peanuts (MT) In-Shell Peanuts (MT) : Down - 11.8 % Down - 16.1%Brittany EtheridgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Padmavati Gora BadalDokument63 SeitenPadmavati Gora BadalLalit MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- We Generally View Objects As Either Moving or Not MovingDokument11 SeitenWe Generally View Objects As Either Moving or Not MovingMarietoni D. QueseaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CELTA Pre-Interview Grammar, Vocabulary and Pronunciation ExercisesDokument4 SeitenCELTA Pre-Interview Grammar, Vocabulary and Pronunciation ExercisesMichelJorge100% (2)

- LAU Paleoart Workbook - 2023Dokument16 SeitenLAU Paleoart Workbook - 2023samuelaguilar990Noch keine Bewertungen

- Calibration GuideDokument8 SeitenCalibration Guideallwin.c4512iNoch keine Bewertungen

- High Yield Pics For STEP 2 CKDokument24 SeitenHigh Yield Pics For STEP 2 CKKinan Alhalabi96% (28)

- Solwezi General Mental Health TeamDokument35 SeitenSolwezi General Mental Health TeamHumphreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jiangsu Changjiang Electronics Technology Co., Ltd. SOT-89-3L Transistor SpecificationsDokument2 SeitenJiangsu Changjiang Electronics Technology Co., Ltd. SOT-89-3L Transistor SpecificationsIsrael AldabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osprey, Men-At-Arms #008 The Black Watch (1971) (-) OCR 8.12Dokument48 SeitenOsprey, Men-At-Arms #008 The Black Watch (1971) (-) OCR 8.12mancini100% (4)

- Principles of CHN New UpdatedDokument4 SeitenPrinciples of CHN New Updatediheart musicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biosynthesis of FlavoursDokument9 SeitenBiosynthesis of FlavoursDatta JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Politics and Constitution SyllabusDokument7 SeitenPhilippine Politics and Constitution SyllabusIvy Karen C. Prado100% (1)

- Assessing Student Learning OutcomesDokument20 SeitenAssessing Student Learning Outcomesapi-619738021Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pembahasan Soal UN Bahasa Inggris SMP 2012 (Paket Soal C29) PDFDokument15 SeitenPembahasan Soal UN Bahasa Inggris SMP 2012 (Paket Soal C29) PDFArdi Ansyah YusufNoch keine Bewertungen

- James and Robson 2014 UAVDokument8 SeitenJames and Robson 2014 UAVAdriRGNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Starter WBDokument88 Seiten1 Starter WBHYONoch keine Bewertungen

- STR File Varun 3Dokument61 SeitenSTR File Varun 3Varun mendirattaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Finding My Voice in ChinatownDokument5 SeitenFinding My Voice in ChinatownMagalí MainumbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Double Burden of Malnutrition 2017Dokument31 SeitenDouble Burden of Malnutrition 2017Gîrneţ AlinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Power of Networking for Entrepreneurs and Founding TeamsDokument28 SeitenThe Power of Networking for Entrepreneurs and Founding TeamsAngela FigueroaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timoshenko Beam TheoryDokument8 SeitenTimoshenko Beam Theoryksheikh777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Concepts of Citrix XenAppDokument13 SeitenBasic Concepts of Citrix XenAppAvinash KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Nima Naghibi) Rethinking Global Sisterhood Weste PDFDokument220 Seiten(Nima Naghibi) Rethinking Global Sisterhood Weste PDFEdson Neves Jr.100% (1)

- Product Differentiation and Market Segmentation As Alternative Marketing StrategiesDokument7 SeitenProduct Differentiation and Market Segmentation As Alternative Marketing StrategiesCaertiMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Utilization of Wood WasteDokument14 SeitenUtilization of Wood WasteSalman ShahzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ra 11223 PDFDokument34 SeitenRa 11223 PDFNica SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defender 90 110 Workshop Manual 5 WiringDokument112 SeitenDefender 90 110 Workshop Manual 5 WiringChris Woodhouse50% (2)

- Ubc 2015 May Sharpe JillianDokument65 SeitenUbc 2015 May Sharpe JillianherzogNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENVPEP1412003Dokument5 SeitenENVPEP1412003south adventureNoch keine Bewertungen

- 341SAM Ethical Leadership - Alibaba FinalDokument16 Seiten341SAM Ethical Leadership - Alibaba FinalPhoebe CaoNoch keine Bewertungen