Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Core Competencies For Patient Safety Research: A Cornerstone For Global Capacity Strengthening

Hochgeladen von

Adrian De VeraOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Core Competencies For Patient Safety Research: A Cornerstone For Global Capacity Strengthening

Hochgeladen von

Adrian De VeraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ERROR MANAGEMENT

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 on 12 January 2011. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on 16 August 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Core competencies for patient safety

research: a cornerstone for global

capacity strengthening

Anne Andermann,1 Liane Ginsburg,2 Peter Norton,3 Narendra Arora,4

David Bates,5 Albert Wu,6 Itziar Larizgoitia,7 On behalf of the Patient Safety

Research Training and Education Expert Working Group of WHO Patient Safety

1

Woodrow Wilson School of Background: Tens of millions of patients worldwide levels of development. WHO Patient Safety

Public and International suffer disabling injuries or death every year due to unsafe (formerly known as the World Alliance for

Affairs, Princeton University, medical care. Nonetheless, there is a scarcity of research Patient Safety) was established in 2004 to

Princeton, New Jersey, USA

2

School of Health Policy & evidence on how to tackle this global health priority. The mobilise global efforts to improve the safety

Management, York shortage of trained researchers is a major limitation, of healthcare for patients in all WHO

University, Toronto, Canada particularly in developing and transitional countries. Member States. WHO estimates that millions

3

Department of Family Objectives: As a first step to strengthen capacity in this

Medicine, University of of patients worldwide suffer disabling injuries

area, the authors developed a set of internationally

Calgary, Ontario, Canada or death every year due to unsafe medical

4 agreed core competencies for patient safety research

The INCLEN Trust

worldwide.

practices and care.1 While nearly one in ten

International, New Delhi,

India Methods: A multistage process involved developing an patients is harmed while receiving healthcare

5

Department of Health Policy initial framework, reviewing the existing literature in well-funded and technologically advanced

and Management, Harvard relating to competencies in patient safety research, hospital settings, there is little evidence about

School of Public Health, and

conducting a series of consultations with potential end the burden of unsafe care in developing

Brigham and Women’s

Hospital, Boston, users and international experts in the field from over countries, where the risk of patient harm may

Massachusetts, USA 35 countries and finally convening a global consensus be even greater due to limitations in infra-

6

Department of Health Policy conference. structure, technology and human resources,

and Management, Johns Results: An initial draft list of competencies was

Hopkins Bloomberg School either in hospital or in primary care and

of Public Health, Baltimore,

grouped into three themes: patient safety, research community settings.

Maryland, USA methods and knowledge translation. The competencies

7

WHO Patient Safety gives special emphasis

WHO Patient Safety, World were considered by the WHO Patient Safety task force,

Health Organization, Geneva,

to research advancement as one of the essen-

by potential end users in developing and transitional

Switzerland tial building blocks for achieving safer care.

countries and by international experts in the field to be

relevant, comprehensive, clear, easily adaptable to Patient safety research is defined as: An action-

Correspondence to

local contexts and useful for training patient safety oriented field of scientific enquiry that aims to

Dr Itziar Larizgoitia, WHO

Patient Safety, 20 Ave Appia, researchers internationally. determine: 1) the type and magnitude of harm

1211 Geneva 27, Conclusions: Reducing patient harm worldwide will caused by unsafe care; 2) the contributing

Switzerland; require long-term sustained efforts to build capacity to factors and causal pathways that are potentially

larizgoitiai@who.int

enable practical research that addresses local modifiable, including unsafe systems,

Accepted 30 April 2010 problems and improves patient safety. The first edition processes and behaviours; and 3) cost-effective

of Competencies for Patient Safety Researchers is and locally adapted interventions that can

proposed by WHO Patient Safety as a foundation for successfully prevent, reduce or mitigate unsafe

strengthening research capacity by guiding the

care to reduce harm. More knowledge - and

development of training programmes for researchers

better use of the knowledge available - are

in the area of patient safety, particularly in developing

essential for understanding the extent and

and transitional countries, where such research is

urgently needed. causes of patient harm, and for developing

solutions that can be used in different

contexts. To address the lack of research

capacity in patient safety research worldwide,

This paper is freely available

online under the BMJ INTRODUCTION especially in developing and transitional

Journals unlocked scheme, countries, WHO Patient Safety convened

see http://qualitysafety.bmj.

com/site/about/unlocked.

Patient safety represents a global public a task force of world experts in patient safety

xhtml health problem which affects countries at all research, curriculum development and

96 BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:96e101. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814

ERROR MANAGEMENT

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 on 12 January 2011. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on 16 August 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.

research capacity strengthening from a wide range of list of competencies (version 0.2) would be easy to

countries in early 2008. The initial goal was to develop a set understand, appropriate to local contexts and useful for

of core competencies for patient safety research to guide training future patient safety researchers. Feedback was

the development of education and training opportunities used to revise the competencies to version 0.3. A second

for promoting capacity strengthening in this area. Below, external consultation with international experts in

we describe the group’s approach to competency devel- patient safety (Stage 6) involved sending an online

opment, present the competencies, and discuss implica- questionnaire to a convenience sample of 155 experts

tions and next steps. The full report is available on the chosen from several key meeting and conference lists to

WHO website (http://www.who.int/patientsafety/).2 assess the face validity of the proposed list of compe-

tencies. The sample, which included the external leads

METHODS of WHO Patient Safety as well as advisory council

members for the Research Programme, involved experts

The 21-member international task force convened by from the six WHO world regions, although the

WHO Patient Safety followed a seven-stage process predominance was from high-income countries in

(figure 1) to develop patient safety research competen- Europe and North America where patient safety research

cies that would be applicable in developing, transitional has been more developed. Version 0.4 of the patient

and developed countries. The first stage involved safety research competencies was presented to the task

preparing a background paper and initial framework for force for discussion at a 2-day conference (Stage 7)

patient safety research competencies.3 These documents aimed at (a) achieving consensus on a first edition of the

were discussed at the first meeting of the task force in Patient Safety Research Competencies (version 1.0), as

February 2008 (Stage 2). An expanded literature review well as (b) identifying steps for further validation and

of competencies relating to patient safety, research and dissemination of the competencies, and for their

knowledge translation (Stage 3) was combined with the incorporation into existing or new training programmes

initial framework from Stage 1 and feedback from Stage in developing and transitional countries in particular.

2 to create a preliminary list of patient safety research

competencies (version 0.1). An internal consultation RESULTS

with the task force (Stage 4) used an on-line survey to

identify key documents or competencies that did not In January 2008, when the seven-stage process of

emerge from the Stage 3 literature review, and to suggest competency development began, little had been

changes to the content or format of the preliminary list published on the nature, boundaries and challenges of

of competencies. Feedback was incorporated into patient safety research.4e9 Since that time, a great deal

version 0.2 of the competencies. A large-scale external more has emerged in the literature.10e18 The initial

consultation with potential end users of the competen- framework for patient safety research competencies that

cies (Stage 5) used a snowball technique to send an emerged from Stage 1 suggested that competencies may

on-line survey to researchers, practitioners and policy- differ for different target audiences, different regional

makers in developing and transitional countries working contexts and different levels of research advancement

in the area of patient safety, to determine whether the (table 1).3 The primary discussion points of the inter-

national task force (Stage 2) focused on (a) how to

develop patient safety research competencies that would

Stage 1 Competencies framework developed be relevant for developing and transitional countries,

and (b) who should be the main target audience of

Stage 2 Initial Meeting of the Expert Working Group

patient safety research education and training.

Twenty-nine documents were identified for inclusion

Stage 3 Literature review and synt hesis

in the literature review and synthesis of competencies

relating to patient safety research (Stage 3). These

Stage 4 Internal consultation wit h the working group

included documents on competencies for promoting

patient safety,19e22 for conducting health services

Stage 5 External consultat ion wit h potential end users

research23 24 and for knowledge translation.25 26 A

Stage 6 Final consultat ion with internat ional experts preliminary list of patient safety research competencies

was created (version 0.1) based on key themes which

Stage 7 Consensus conference emerged from the literature (figure 2) relating to

patient safety, research, and knowledge translation.

Figure 1 Seven-stage patient safety research competency Feedback on this preliminary list was obtained from nine

development process. out of 21 members (43%) of the task force (Stage 4).

BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:96e101. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 97

ERROR MANAGEMENT

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 on 12 January 2011. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on 16 August 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.

developing and transitional countries. The external

Table 1 Initial framework for patient safety research

competencies* consultation yielded usable data from 73 respondents in

35 developing and transitional countries across all six

Advanced

knowledge and WHO regions. Respondents were largely early to mid-

skills needed in Policy/ career academics or physicians involved in conducting

the following Academic Clinician manager research relating to patient safety (96%), with one-third

competency researcher researcher researcher focussing on safe medicines and devices, and another

areas: track track track

third focussing on healthcare associated infections.

1. Science of O + O Respondents indicated that the proposed patient safety

patient safety research competencies were easy to understand and

2. At least one O e e relevant in developing and transitional countries, and

patient safety

subspecialty

would be useful for training patient safety researchers in

3. Research design + O O these regions. Respondents also indicated that few

and methodology patient safety research training opportunities presently

4. Conducting + O O exist (see table 2). At least half of respondents believed

research that each of the three competency areas is important for

5. Statistics and + O O

practitioners, policy-makers and academic researchers

data analysis

6. Knowledge O O + alike, thus indicating that a single list of competencies

translation for all three profiles of patient safety researchers should

O, essential competency; e, competency could be de-emphasised; be retained in version 0.3.

+, additional emphasis may be required. Of the 46 international experts who responded in

*Adapted from Ginsburg and Norton.3 Stage 6, 85% found the competencies easy to under-

stand, 87% considered them to be appropriate for local

Respondents to the internal consultation highlighted contexts, and 93% thought they would be helpful for

the need for further attention to questions about training future patient safety researchers internationally

whether and how patient safety research competencies (see table 2). They also emphasised the need to avoid

may differ for different researcher profiles (eg, academic the use of technical jargon (such as ‘disseminating’ and

researcher, policy-maker, healthcare practitioner inter- ‘surveillance’) and the need for subdividing competen-

ested in research), different regional, social, economic cies that cover multiple concepts and grouping together

and cultural contexts, and the extent to which the those where there is overlap.

competencies take into account unique contextual issues In the final stage of the competency development

in developing countries. process (Stage 7), 17 of the 21 members of the task

In response to these concerns, Stage 5 solicited feed- force, as well as three key informants, attended

back from potential end users of the competencies in a consensus conference for an in-depth discussion of

version 0.4 of the patient safety research competencies.

During the conference, modifications were made to

better reflect that the main target audience are

researchers (as opposed to end users of research such as

clinicians or policy-makers) and to ensure that the final

document would employ appropriate terminology

commonly used in the field of competency development.

Consensus was reached that since all competencies

contained basic and advanced levels, there was no

need to specify competencies as basic or advanced

for trainees at different academic levels. The first

edition of the Competencies for Patient Safety Research

(version 1.0dbox 1) was agreed upon at the close of the

meeting.

DISCUSSION

Patient safety research competencies represent the

Figure 2 Emerging themes relating to patient safety research fundamental knowledge, ability, skills and expertise

competencies. needed to carry out research in this area and to use

98 BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:96e101. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814

ERROR MANAGEMENT

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 on 12 January 2011. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on 16 August 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.

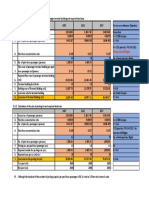

Table 2 External consultation key results

Potential end users from developing International experts in patient

and transitional countries (Stage 5 safety research (Stage 6

respondents, n[73) respondents, n[46)

Percentage reporting the competencies

Are easy to understand 63 (86%) 39 (85%)

Do not require modification 60 (82%) 32 (70%)

Are well adapted to local contexts 64 (88%) 40 (87%)

Would be useful for training patient 73 (100%) 43 (93%)

safety researchers

Percentage reporting the competencies would be useful

As a systematic basis for training 60 (82%) 37 (80%)

For defining learning objectives 55 (75%) 33 (72%)

To emphasise different knowledge 53 (73%) 37 (80%)

and skills needed

As a basis to be tailored to different 37 (51%) 25 (54%)

trainee profiles

To evaluate the progress of trainees 57 (78%) 23 (50%)

Competency area considered the main priority for training patient safety researchers in their own country:

Patient safety theory and practice 31 (42%) NA

Designing and conducting research 24 (33%)

Translating findings into safer care 18 (25%)

Percentage aware of training 13 (18%) NA

opportunities for patient safety

researchers in their country

patient safety research evidence to make healthcare a systematic basis for training, (b) define key learning

safer. The current paper describes the methods and objectives that should be covered, (c) demonstrate the

results of a multistage process, including literature many different types of knowledge and skills that are

reviews and consultations with experts and stakeholders needed to carry out patient safety research, (d) tailor

that were used to develop patient safety research training programmes and curricula to different profes-

competencies. The competencies that emerged are sional profiles, contexts and needs, and (e) help evaluate

intended to guide patient safety researchers in acquiring the progress of patient safety research trainees.

the knowledge and skills needed to conduct research Experience utilising the proposed patient safety

that aims to better understand the magnitude and type research competencies will be essential to achieve

of patient harm, identify potentially modifiable contrib- a better understanding of the completeness, specificity

uting factors, and design and test cost-effective and and acceptability by different user groups in different

locally adapted interventions that can successfully socio-economic environments, as well as the feasibility of

prevent, reduce or mitigate unsafe care to reduce harm. incorporating the competencies into a variety of educa-

The first edition of Competencies for Patient Safety tional programmes and training modalities. This will

Research (version 1.0dbox 1) proposed in this paper require the more general competency areas of

emphasises (a) understanding the science of patient ‘designing and conducting patient safety research’ and

safety, (b) conducting valid and ethical research and (c) ‘translating research evidence to improve the safe care of

translating research into practice. Our results indicate patients’ to be adapted to the field of patient safety

that both experts and potential end users believe the research by drawing upon context-specific examples,

competencies can be tailored to different audiences, case studies, data collection tools and study designs that

local and national contexts, and levels of educational are particularly useful in trying to address research

attainment. Our results further suggest the core questions relating to patient safety.27

competencies have potential to be used by educational

and research institutions in high- as well as low- and Implications for policy and practice

middle-income country contexts to inform curricula and Relatively little is known about the epidemiology of

the development of training programmes. In particular, patient safety in developing or transitional countries,

the core competencies can be used to (a) provide and about what strategies will be effective in improving

BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:96e101. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 99

ERROR MANAGEMENT

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 on 12 January 2011. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on 16 August 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Box 1 First edition of Core Competencies for Patient Safety Research

Patient safety researchers are able to:

1. Describe the fundamental concepts of the science of patient safety, in their specific social, cultural and economic context.

These concepts include the following items, among others:

1.1. Basic definitions and foundational concepts, including human factors and organisational theory

1.2. The burden of unsafe care

1.3. The importance of a culture of safety

1.4. The importance of effective communication and collaboration in care delivery teams

1.5. The use of evidence-based strategies for improving the quality and safety of care

1.6. The identification and management of hazards and risks

1.7. The importance of creating environments for safe care

1.8. The importance of educating and empowering patients to be partners for safer care

2. Design and conduct patient safety research. These competencies include the ability to perform, but are not necessarily

restricted to, the following:

2.1. Search, appraise and synthesise the existing research evidence

2.2. Involve patients and carers in the research process starting with defining the research objectives

2.3. Identify research questions that address important knowledge gaps

2.4. Select an appropriate qualitative or quantitative study design to answer the research question

2.5. Conduct research using a systematic approach, valid methodologies and information technology

2.6. Employ valid and reliable data measurement and data analysis techniques

2.7. Foster interdisciplinary research teams and supportive environments for research

2.8. Write a grant proposal

2.9. Obtain research funding

2.10. Manage research projects

2.11. Write-up research findings and disseminate key messages

2.12. Evaluate the impact of interventions as well as feasibility and resource requirements

2.13. Identify and evaluate indicators of patient safety for use in monitoring and surveillance

2.14. Ensure professionalism and ethical conduct in research

3. Be part of the process of translating research evidence to improve the safe care of patients. The skills involved include, but

are not restricted to, the ability to contribute to the following:

3.1. Appraise and adapt research evidence to specific social, cultural and economic contexts

3.2. Use research evidence to advocate for patient safety

3.3. Define goals and priorities for making healthcare safer

3.4. Translate research evidence into policies and practices that reduce harm

3.5. Partner with key stakeholders in overcoming barriers to change

3.6. Promote standards and legal frameworks to improve safety

3.7. Institutionalise changes to build supportive systems for safer care

3.8. Apply financial information for knowledge translation

3.9. Promote leadership, teaching and safety skills.

patient safety in these regions. Further research is develop their knowledge and skills by being involved in

therefore needed, which will require the creation of conducting research. The Core Competencies for

a critical mass of newly trained researchers able to fill the Patient Safety Research provide a framework for the

many knowledge gaps that exist. For many, the goal of ongoing education and training of patient safety

education and training in patient safety research is to researchers worldwide. Establishing formal training

create research that leads to actions that improve patient programmes at accredited academic institutions across

safety. However, the link between training patient safety all WHO regions may take many years. However, the

researchers and these more distal outcomes will likely be growth of research networks and the availability of

difficult to demonstrate in the short-term. Accordingly, targeted funding to support patient safety research can

process indicators such as increases in the number of already be used to promote research-capacity strength-

courses offered in patient safety research, the number of ening, particularly in developing and transitional coun-

graduates, the local adoption of evidence-based safe tries where such research is urgently needed.

practices or the number of policies aimed at improving

Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the members of the

safety would also be important measures of success. WHO Patient Safety Research Training and Education Expert Working Group

Building research capacity is a long-term process that for their important contribution to this work: Ahmed Al-Mandhari (Sultan

requires sustained effort, in terms of formal training Qaboos University Hospital, Sultanate of Oman); Antoine Geissbuhler

(Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève, Switzerland); John Goshbee (University

opportunities but, more importantly, in providing of Michigan, USA); Festus Ilako (African Medical and Research Foundation,

a nurturing environment for trainees to continue to AMREF, Kenya); Mark Joshi (University of Nairobi, Kenya); Rakesh Lodha

100 BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:96e101. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814

ERROR MANAGEMENT

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 on 12 January 2011. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on 16 August 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.

(All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India); Sergio Muñoz Navarro 8. Grol R, Berwick DM, Wensing M. On the trail of quality and safety in

(Universidad de La Frontera, Chile); Hillegonda Maria Dutilh Novaes health care. BMJ 2008;336:74e6.

(University of São Paolo, Brazil); John Orav (Harvard School of Public 9. Cook RL. Lessons from the war on cancer: the need for basic

research on safety. J Patient Saf 2005;1:7e8.

Health, USA); Alan Pearson (Johanna Briggs Institute, Australia); Peter 10. Brown C, Hofer T, Johal A, et al. An epistemology of patient safety

Pronovost (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, USA); Miguel Recio research: a framework for study design and interpretation. Part 1.

Segoviano (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain); Jiruth Sriratanaban Conceptualising and developing interventions. Qual Saf Health Care

(Chulalongkorn University, Thailand); Naruo Uehara (Tohoku University, 2008;17:158e62.

Japan); Steven Wayling (Special Programme for Research and Training in 11. Brown C, Hofer T, Johal A, et al. An epistemology of patient safety

research: a framework for study design and interpretation. Part 2.

Tropical Diseases, World Health Organization, Switzerland); Maria

Study design. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:163e9.

Woloshynowych (Imperial College, United Kingdom); and Zhao Yue (Peking 12. Brown C, Hofer T, Johal A, et al. An epistemology of patient safety

University People’s Hospital, P.R. China). The authors would also like to research: a framework for study design and interpretation. Part 3.

thank Jason Frank (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, End points and measurement. Qual Saf Health Care

Canada) for sharing his expertise in the area of competency development, as 2008;17:170e7.

well as the many interns who contributed at various stages to this project: 13. Brown C, Hofer T, Johal A, et al. An epistemology of patient

safety research: a framework for study design and interpretation.

Khalifa Elmusharaf (University of Khartoum, Sudan); Aimee McHale

Part 4. One size does not fit all. Qual Saf Health Care

(University of North Carolina, USA); Jean-Louis Keene (McGill University, 2008;17:178e81.

Canada); Naomi Dove (University of British Columbia, Canada); Ruramayi 14. Bates DW. Mountains in the clouds: patient safety research. Qual Saf

Rukini (University of Bristol, United Kingdom) and Shannon Gibson Health Care 2008;17:156e7.

(University of Victoria, Canada). The authors are also grateful to all the 15. Kass N, Pronovost PJ, Sugarman J, et al. Controversy and quality

experts and stakeholders from around the world who provided feedback on improvement: lingering questions about ethics, oversight, and

patient safety research. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf

earlier drafts of this work. 2008;34:349e53.

Competing interests None. 16. Hofoss D, Deilkås E. Roadmap for patient safety research:

approaches and roadforks. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:812e17.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed. 17. Pronovost PJ, Goeschel CA, Marsteller JA, et al. Framework for patient

safety research and improvement. Circulation 2009;119:330e7.

18. McCarthy M, Brookes M, Scourfield P. Patient safety research:

REFERENCES shaping the European agenda. Clin Med 2009;9:145e6.

1. The Research Priority Setting Working Group of the WHO World 19. Cronenwett L, Sherwood G, Barnsteiner J, et al. Quality and safety

Alliance for Patient Safety. Summary of the evidence on patient education for nurses. Nurs Outlook 2007;55:122e31.

safety: implications for research. Geneva: World Health Organization, 20. Sandars J, Bax N, Mayer D, et al. Educating undergraduate medical

2008. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/ students about patient safety: priority areas for curriculum

9789241596541_eng.pdf. development. Med Teach 2007;29:60e1.

2. The Patient Safety Research Training and Education Expert Working 21. Singh R, Naughton B, Taylor JS, et al. A comprehensive collaborative

Group of WHO. Patient Safety. Competencies for Patient Safety patient safety residency curriculum to address the ACGME core

Research. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. http://www. competencies. Med Educ 2005;39:1195e204.

who.int/patientsafety/research. 22. Walton M. The National Patient Safety Education Framework.

3. Ginsburg LR, Norton PG. Background paper 1: creating leaders in Sydney, Australia: The Australian Council for Safety and Quality in

patient safety research: Essential competencies for conducting Health Care and The University of Sydney, 2005.

research and translating evidence to reduce patient harm. Prepared 23. AHRQ. Health Services Research Core Competencies. Final Report.

for the 1st meeting of the Patient Safety Research Training and Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007.

Education Expert Working Group of WHO Patient Safety, 18e19 24. Burke L, Schlenk E, Sereika S, et al. Developing research

February 2008, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. competence to support evidence-based practice. J Prof Nurs

4. Meyer GS, Battles J, Hart JC, et al. The US agency for healthcare 2005;21:358e63.

research and quality’s activities in patient safety research. Int J Qual 25. Armstrong R, Waters E, Roberts H, et al. The role and theoretical

Health Care 2003;15(Suppl 1):25e30. evolution of knowledge translation and exchange in public health.

5. Battles JB, Lilford RJ. Organizing patient safety research to identify J Public Health 2006;28:384e9.

risks and hazards. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12(Suppl 2):2e7. 26. Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P. Development of a framework for

6. Lilford RJ. Patient safety research: does it have legs? Qual Saf Health knowledge transfer: understanding user context. J Health Serv Res

Care 2002;11:113e14. Policy 2005;8:94e9.

7. Meyer GS, Eisenberg JM. The end of the beginning: the strategic 27. WHO Patient Safety. Case Studies in Patient Safety Research.

approach to patient safety research. Qual Saf Health Care Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. http://www.who.int/

2002;11:3e4. patientsafety/research/strengthening_capacity/classics/.

BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:96e101. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041814 101

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7Dokument2 SeitenSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7Ram Duran82% (11)

- Jci Ssi ToolkitDokument191 SeitenJci Ssi ToolkitMr. Jonathan Hudson O.T. Manager, Justice K.S. Hegde Charitable Hospital100% (3)

- Patient Safety GuideDokument272 SeitenPatient Safety Guidejuanlaplaya100% (1)

- Peasant Revolution in EthiopiaDokument288 SeitenPeasant Revolution in Ethiopiaobsii100% (1)

- Core Competencies For Patient Safety (B)Dokument7 SeitenCore Competencies For Patient Safety (B)Meylinda KurniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safer Primary Care OMSDokument20 SeitenSafer Primary Care OMSJulian SandovalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safer Primary Care OMSDokument20 SeitenSafer Primary Care OMSJulian SandovalNoch keine Bewertungen

- No1 Sep2009Dokument2 SeitenNo1 Sep2009risnayektiNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHO Brochure GPSC - Medication Without HarmDokument16 SeitenWHO Brochure GPSC - Medication Without HarmdeddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intervention Studyto UpgradeDokument10 SeitenIntervention Studyto UpgradeDalia Talaat WehediNoch keine Bewertungen

- About Us: Patient SafetyDokument7 SeitenAbout Us: Patient SafetyFaulya Nurmala ArovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Safety in RadoncDokument4 SeitenPatient Safety in Radoncapi-575843507Noch keine Bewertungen

- A National Study of Patient Safety Culture And.14Dokument7 SeitenA National Study of Patient Safety Culture And.14Yo MeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient SafetyDokument258 SeitenPatient SafetycosommakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Ps CurriculumDokument258 SeitenWho Ps CurriculumrajaakhaterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of Patient Safety Culture in Primary Care Setting, Al-Mukala, YemenDokument9 SeitenAssessment of Patient Safety Culture in Primary Care Setting, Al-Mukala, YemenRaja Zila Santia ANoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1111@nin 12390Dokument14 Seiten10 1111@nin 12390YLA KATRINA BONILLANoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Open - 2022 - Wang - Assessing Patient Safety Culture in Obstetrics Ward A Pilot Study Using A Modified ManchesterDokument7 SeitenNursing Open - 2022 - Wang - Assessing Patient Safety Culture in Obstetrics Ward A Pilot Study Using A Modified ManchesterAirha Mhae HomoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploring Patient Safety Culture in Emergency DepartmentsDokument7 SeitenExploring Patient Safety Culture in Emergency Departmentsmuhammad ismailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Safety Cases in Industry and HealthcareDokument44 SeitenUsing Safety Cases in Industry and Healthcaremaheshwaghe272Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yamalik 2012Dokument8 SeitenYamalik 2012martin ariawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Removal of Sharp Object Patient SaftyDokument6 SeitenRemoval of Sharp Object Patient SaftyAlibaba AlihaihaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introducing Quality Patient Safety ProgramDokument15 SeitenIntroducing Quality Patient Safety ProgramfitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Measurement and Monitoring of SafetyDokument92 SeitenThe Measurement and Monitoring of SafetycicaklomenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Self-Education On Patient Safety Via Smartphone Application For Self-Efficacy and Safety Behaviors of Inpatients in KoreaDokument9 SeitenEffects of Self-Education On Patient Safety Via Smartphone Application For Self-Efficacy and Safety Behaviors of Inpatients in Korea'Amel'AyuRizkyAmeliyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 The Effect of Self-Learning ProofDokument10 Seiten4 The Effect of Self-Learning ProofdipanajnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self SafetyDokument9 SeitenSelf SafetyCitra Suarna NhsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Predictors and Outcomes of Patient Safety Culture in HospitalsDokument12 SeitenPredictors and Outcomes of Patient Safety Culture in HospitalsEvi Furi AmaliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WFCCN Chapter 4 Safety-and-Quality-in-the-ICU 2nd EditionDokument13 SeitenWFCCN Chapter 4 Safety-and-Quality-in-the-ICU 2nd EditionJuan Carlos Mora TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fekonja 2023 Factors Contributing To Patient SafDokument17 SeitenFekonja 2023 Factors Contributing To Patient Safsergejkmetec1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Awareness and Implementation of Nine World Health Organization 'S Patient Safety Solutions Among Three Groups of Healthcare Workers in OmanDokument8 SeitenAwareness and Implementation of Nine World Health Organization 'S Patient Safety Solutions Among Three Groups of Healthcare Workers in OmanDeny SetyansNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4-8-1-989 Format For SynopsisDokument7 Seiten4-8-1-989 Format For SynopsisYashoda SatputeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety and Health at Work: Original ArticleDokument8 SeitenSafety and Health at Work: Original ArticleOluwaseun Aderele GabrielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Safety Education For Undergraduate Medical Students: A Systematic ReviewDokument8 SeitenPatient Safety Education For Undergraduate Medical Students: A Systematic ReviewNovaamelia jesicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient SafetyDokument8 SeitenPatient SafetyQuennie Abellon QuimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2727-Texto Do Artigo-13334-1-10-20230331Dokument14 Seiten2727-Texto Do Artigo-13334-1-10-20230331Par AcesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acceptance of The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist Among Surgical Personnel in Hospitals in Guatemala CityDokument5 SeitenAcceptance of The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist Among Surgical Personnel in Hospitals in Guatemala Citygede ekaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review Needle Stick InjuryDokument6 SeitenLiterature Review Needle Stick Injuryafmzslnxmqrjom100% (1)

- Experiences With Neonatal Jaundice Management in Hospitals and The Community: Interviews With Australian Health ProfessionalsDokument9 SeitenExperiences With Neonatal Jaundice Management in Hospitals and The Community: Interviews With Australian Health Professionalsstardust.m002Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pressure Ulcer PreventionDokument11 SeitenPressure Ulcer PreventionChi ChangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safe Surgery JournalDokument10 SeitenSafe Surgery JournalNur LaelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety and Health at Work: Original ArticleDokument8 SeitenSafety and Health at Work: Original ArticlePractice Medi-nursingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Ier PSP 2010.3 EngDokument16 SeitenWho Ier PSP 2010.3 EngAdebisiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On Surgical Safety ChecklistDokument11 SeitenLiterature Review On Surgical Safety Checklistfut0mipujeg3100% (1)

- Who Ps Curriculum SummaryDokument12 SeitenWho Ps Curriculum SummaryHengky_FandriNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHO Primary CareDokument32 SeitenWHO Primary CareCukup StsajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vaccine Development StagesDokument31 SeitenVaccine Development Stageschernet kebedeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monitoring Preventable Adverse Events and Near.9Dokument6 SeitenMonitoring Preventable Adverse Events and Near.9danny widjajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morse 2001Dokument5 SeitenMorse 2001Anonymous EAPbx6Noch keine Bewertungen

- Donaldson LJ, Fletcher MG. The WHO World Alliance For Patient Safety: Towards The Years of Living Less Dangerously. Med J Aust 184 (10 Suppl) :S69-S72Dokument5 SeitenDonaldson LJ, Fletcher MG. The WHO World Alliance For Patient Safety: Towards The Years of Living Less Dangerously. Med J Aust 184 (10 Suppl) :S69-S72be a doctor for you Medical studentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eng 2Dokument7 SeitenEng 2Mukarrama MajidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Safety and Safety Culture in Primary Health Care: A Systematic ReviewDokument12 SeitenPatient Safety and Safety Culture in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Reviewjulio cruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ajph 94 11 1926Dokument6 SeitenAjph 94 11 1926Neenk GelizzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Groah 2014 Table TalkDokument12 SeitenGroah 2014 Table TalkChandra JohannesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interventions To Decrease Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in The ICU: The Keystone Intensive Care Unit ProjectDokument5 SeitenInterventions To Decrease Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in The ICU: The Keystone Intensive Care Unit ProjectanggitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Implementation of Patient Safety Culture Deny Gunawan - CompressedDokument7 SeitenThe Implementation of Patient Safety Culture Deny Gunawan - Compresseddeny gunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Perception of Patient Safety Culture Dimensions On The Willingness To Report Patient Safety IncidentDokument14 SeitenEffect of Perception of Patient Safety Culture Dimensions On The Willingness To Report Patient Safety IncidentMuhammad IsranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paediatric Neck MassesDokument7 SeitenPaediatric Neck MassesGiovanni HenryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics of Innovation in NeurosurgeryVon EverandEthics of Innovation in NeurosurgeryMarike L. D. BroekmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy: An Evidence-Based Review on Current Status and Future PerspectivesVon EverandVaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy: An Evidence-Based Review on Current Status and Future PerspectivesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Virologic Failure in HIV: An Updated Clinician’s Guide to Assessment and ManagementVon EverandVirologic Failure in HIV: An Updated Clinician’s Guide to Assessment and ManagementNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pecs BookDokument2 SeitenPecs BookDinaliza UtamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fatal Charades Roman Executions Staged AsDokument33 SeitenFatal Charades Roman Executions Staged AsMatheus Scremin MagagninNoch keine Bewertungen

- Search For The Nile RevisitedDokument2 SeitenSearch For The Nile RevisitedEdmundBlackadderIVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference - APA - Citations & ReferencingDokument34 SeitenReference - APA - Citations & ReferencingDennis IgnacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imperial College London Graduation Ceremony Terms and Conditions 2019Dokument9 SeitenImperial College London Graduation Ceremony Terms and Conditions 2019Riza Agung NugrahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edt 315 ModDokument2 SeitenEdt 315 Modapi-550565799Noch keine Bewertungen

- Excercise - Terminal Area - JICA - Wbook 2 PDFDokument1 SeiteExcercise - Terminal Area - JICA - Wbook 2 PDFDipendra ShresthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approaches To Discourse AnalysisDokument16 SeitenApproaches To Discourse AnalysisSaadat Hussain Shahji PanjtaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modicare and Its ImpactDokument9 SeitenModicare and Its ImpactsagarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Architectral Thesis 2019-2020: Indraprastha Sanskriti Kala KendraDokument13 SeitenArchitectral Thesis 2019-2020: Indraprastha Sanskriti Kala Kendravaibhavi pendamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Optimizing Grade 12 P eDokument4 SeitenHealth Optimizing Grade 12 P eKookie100% (1)

- Sustainable Residential Housing For Senior CitizensDokument9 SeitenSustainable Residential Housing For Senior CitizensPriyaRathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- RINZA Global SDN BHD Company ProfileDokument7 SeitenRINZA Global SDN BHD Company ProfilerinzaglobalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes For Transportation LawDokument9 SeitenNotes For Transportation LawDaphnie Cuasay100% (1)

- Ela Final Exam ReviewDokument9 SeitenEla Final Exam Reviewapi-329035384Noch keine Bewertungen

- SEAMEODokument279 SeitenSEAMEOEdith PasokNoch keine Bewertungen

- Promotion Decisions Marketing Foundations 5Dokument38 SeitenPromotion Decisions Marketing Foundations 5JellyGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qualifications-Based Selection-The Federal Government ProcessDokument5 SeitenQualifications-Based Selection-The Federal Government ProcessNickson GardoceNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Hierarchical Framework For Supply Chain Performance MeasurementDokument5 SeitenA Hierarchical Framework For Supply Chain Performance MeasurementDenny SheatsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Company Vinamilk PESTLE AnalyzeDokument2 SeitenCompany Vinamilk PESTLE AnalyzeHiền ThảoNoch keine Bewertungen

- S2 2016 372985 Bibliography PDFDokument2 SeitenS2 2016 372985 Bibliography PDFNanang AriesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faqs On Foreign Investment in The PhilippinesDokument8 SeitenFaqs On Foreign Investment in The PhilippinesVanillaSkyIIINoch keine Bewertungen

- Students at Domalandan Center Integrated School I. Introduction and RationaleDokument3 SeitenStudents at Domalandan Center Integrated School I. Introduction and RationaleNors CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Day 1 - Super - Reading - Workbook - Week - 1Dokument19 SeitenDay 1 - Super - Reading - Workbook - Week - 1Funnyjohn007Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture - Why Software FailsDokument3 SeitenLecture - Why Software Failsapi-3759042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Security Analysis and Valuation Assignment On Valuation of Company's Stock Instructor: Syed Babar Ali E-Mail: Babar - Ali@nu - Edu.pkDokument4 SeitenSecurity Analysis and Valuation Assignment On Valuation of Company's Stock Instructor: Syed Babar Ali E-Mail: Babar - Ali@nu - Edu.pkShahzad20Noch keine Bewertungen

- Departures Episode 1Dokument6 SeitenDepartures Episode 1SK - 10KS - Mississauga SS (2672)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Margaret Lynn Salomon: Work Experience SkillsDokument1 SeiteMargaret Lynn Salomon: Work Experience SkillsMargaret Lynn Jimenez SalomonNoch keine Bewertungen