Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Adolescent 20 Stress

Hochgeladen von

Glesit Marie Monta╤o TatoyCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Adolescent 20 Stress

Hochgeladen von

Glesit Marie Monta╤o TatoyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/23566788

Adolescent stress through the eyes of high-risk teens

Article in Pediatric nursing · September 2008

Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

16 5,375

2 authors, including:

Judith W Herrman

University of Delaware

56 PUBLICATIONS 463 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Judith W Herrman on 13 August 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Adolescent Stress through

The Eyes of High-Risk

Continuing

Nursing Teens

Education

Series Denise E. LaRue Judith W. Herrman

Adults often under-estimate the levels of stress in adolescents; however, stressors experienced by teens are

valid and have been described in both lay and professional literature. This article presents a thorough liter-

ature review as well as study results that explore teen perceptions about the stressors they face.

am stressed out” is a phrase stressors they face, offering an adoles- individual. Finkelstein et al. (2007)

“I that has been echoed by

teens down through the

ages. The level of stress

experienced by teens on a daily basis

has been described in lay and profes-

cent perspective to the literature relat-

ed to teen stress. According to Lau

(2002), teens “can experience a spec-

trum of stresses ranging from ordinary

to severe” (p. 238). Stress has been

differentiate stress in the adolescent

period as having both environmental

(objective assessments of conditions)

and psychological (subjective evalua-

tions) perspectives of stressful events.

sional literature. Adults often under- associated with a variety of high-risk The psychosocial perspective views

estimate this level of stress and may behaviors, including smoking, suicide, stress from the experience of the indi-

not always be cognizant of the poten- depression, drug abuse, behavioral vidual and dictates that stress is

tial consequences of stress on teens problems, and participating in high- assessed from a variety of dimen-

and young adults. This lack of appre- risk sexual behaviors (Finkelstein, sions, including the personal meaning

ciation of the stress experienced by Kubzansky, Capitman, & Goodman, of the stressor, the magnitude of the

adolescents may be partially related 2007; Finkelstein, Kubansky, & stressor, the demands placed by the

to a lack of awareness of the sources Goodman, 2006; Goodman, McEwan, stressor, and the coping mechanisms

of stress in teen life, the changing Dolan, Schafer-Kalkhoff, & Adler, available to react to the stimulus

nature of stressors through time, the 2005). In addition, long-term expo- (Finkelstein et al., 2007). The current

ever-evolving complexities of adoles- sure to stress is associated with a vari- study is informed by this psychologi-

cent life, and the tendency for adults ety of chronic psychological and cal, or personal subjective assess-

to minimize their own personal stress physical illnesses (Goodman et al., ment, of the stress experience and

during the teen years or compare their 2005). High-risk teens, or those who how stress is interpreted on the indi-

teen years to the experiences of oth- live in social disadvantage, may be at vidual level.

ers. Physiological development, cog- increased risk for illness related to Chandra and Batada (2006) asked

nitive differences, pubertal changes, chronic exposure to stress, discrimi- teens to use their own words to define

immature coping mechanisms, slower nation, stigma, and a “harsh social stress. One of the teens described his

recovery from stressful events, and environment” (Goodman et al., 2005, stress as “a great deal of pain that’s

lack of experience in dealing with p. 485). Chandra and Batada (2006) inside your body that you can’t get

stress may intensify the stressful purported that assessing adolescent out…and makes you feel bad”

events experienced by adolescents stressors and “the impact of stress is (Chandra & Batada, 2006, p. 4).

(Herrman, 2005). the first step in the prevention and Another stated stress was character-

The purpose of this study was to treatment of its associated chronic ized by “worrying, keeping secrets,

determine teen perceptions about the diseases” (p. 2). Understanding teen gray hair, problems, anger, being

stressors may assist pediatric nurses tense” (Chandra & Batada, 2006, p.

working with adolescents by helping 4). These definitions of stress led to an

teens develop resilience to stress, exploration of adolescent perceptions

Denise E. LaRue, RN, is a Graduate of the thereby increasing teens’ levels of on the origins of stress. The research

University of Delaware, School of Nursing, health (Tussaie, Puskar, & Sereika, related to stress has identified several

Newark, DE. 2007). key sources of stressors having an

Judith W. Herrman, PhD, RN, is the impact on teens, including school,

Assistant Director and an Assistant

Review of the Literature family and home life, social disadvan-

Professor, University of Delaware, Newark, The word stress has emerged as a tage. and other stressors.

DE. part of current daily vocabulary and is School stressors. Pressures in the

not always well defined as a concept school setting were frequently cited as

or uniformly understood. Several stressful by adolescents. Using a pile-

authorities have defined stress as it sort activity, participants in a study by

Objectives, the CNE relates specifically to teens. According Chandra and Batada (2006) identified

posttest, and disclosure to Goodman et al. (2005), stress school work “as the most frequent and

statements can be found refers to a stimulus generating psy- important source of stress” in their

chosocial and physiologic demands, lives (p. 5). The 9th graders stated

on pages 395-396. and requiring action on the part of the that the sudden increase in homework

PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2008/Vol. 34/No. 5 375

was a main stressor for them, along 4). Many boys discussed the stress “of of violence in their homes, their

with “worrying about exams and being the only male in the household,” schools, and on the streets” as well as

grades” (Chandra & Batada, 2006, p. and therefore, feeling the need to the fact that “poverty is also associated

5). Green, Holohan, and Feldheim “defend the home” or to protect the with serious mental disorders” (p. 240).

(2003) identified that for even the family (Chandra & Batada, 2006, pp. An adolescent living in social disadvan-

most confident teen, schoolwork is 4-5). tage may encounter multiple and inter-

“often the first area to fall apart under Teens noted that not getting along related stressors creating a complex

duress” (p. 4). Homework, tests, with a sibling or parents were indicators environment for adolescent growth and

needing to keep up with daily materi- of family stress. Teens also cited that development.

al, the presence of a learning disabili- hearing or seeing their parents fight Other stressors. Other stressors

ty, a conflict with a teacher, problems with each other and worrying about the have been identified as posing threats

with other students, or simply a dislike general outcome of these altercations to teens. For most adolescents, being

of the school experience represented was a frequent stressor (Lau, 2002). hospitalized would increase stress lev-

common areas of stress for the school Customary methods families and par- els. Sources of anxiety may include the

setting (Green et al., 2003). ents use to deal with current stressors “threat of physical harm, separation

According to Lau (2002), there and conflict, including arguing, yelling, from parents, and fear of the unknown

were three main clusters of stress or physical fighting, may affect the and uncertainty about acceptable

associated with school that included level of stress perceived by the teen behaviors” (Lau, 2002, p. 243). Puskar

“fear of success or failure, test or per- (Tarrant & Woon, 1995). According to and Rohay (1999) found that “geo-

formance anxiety, and fears associat- Lau (2002), the sibling stress that teens graphic relocation may compromise or

ed with the school setting” (p. 241). In mention often started with the birth of a retard the adolescent developmentally.

addition, teens with a low self-esteem younger sibling and then continued With a limited repertoire of coping skills

were reported to seek “acknowledg- through the years with a sibling rivalry. and an unfamiliar peer group, teens

ment and acceptance by teachers and Problems, such as “divorce or the may find the transition associated with

peers,” which was also extremely death of a family member, are more relocation particularly stressful” (p.

stressful (Lau, 2002, p. 241). Often, serious than others” (Green et al., 16). Ethier et al. (2006) discovered

“a perceived lack of respect from 2003, p. 3). Divorce may have other that stress manifested by depressive

teachers as well as general conflicts” effects on the family as well, such as symptoms, anxiety, or hostility was

with teachers stressed teens within the lowering the income or changing the associated with “pregnancy, to have

school setting and inhibited “their aca- living arrangements, which in turn had unprotected vaginal sex, to have

demic performance and school func- could have negative effects on the nonmonogamous sex partners, and to

tioning” (Chandra & Batada, 2006, p. child’s “health, well-being, and school not use any form of contraception” and

5). Poor student-teacher relationships achievement” (Lau, 2002, p. 239). further added to the stress (p. 269).

were noted to have a profound impact Social disadvantage stressors. Other adolescent stressors included

on learning, success in school, and Social disadvantage, whether real or obtaining or holding a job, money,

overall stress levels (Chandra & perceived, may be related to race, body image, relationships, and abuse

Batada, 2006). Finally, teens’ tenden- community, ethnicity, or socioeconom- (Puskar & Rohay, 1999). Adolescents

cy to look toward the future after the ic status. Potential stressors associated have also identified major stressors

school experience proved stressful as with social disadvantage in the inner- associated with war, natural disasters,

well (National Campaign to Prevent city environment may include violence, or community disasters. Tarrant and

Teen Pregnancy, 1999). In focus drug use, or poor housing, all of which Woon (1995) commented that “the

groups, participants disclosed finding can contribute negatively to the devel- escalating threat and damage to the

school and education as primary con- opment of the adolescents living in environment and constant world con-

cerns in life, and students pointed out these areas (Miller, Webster, & flict which is graphically brought into

that they were determined to get “an MacIntosh, 2002). The Urban Hassles the home on a daily basis, questions

education to get somewhere in life” Scale was created to rate how frequent- one’s safety and security” (p. 26).

(National Campaign to Prevent Teen ly participants confronted each stres- A newer phenomenon associated

Pregnancy, 1999, p. 6). sor. The most frequently cited stressors with teen stress has been the act of

Family and home life stressors. were found to be “being pressured to “cutting” (Derouin & Bravender, 2004,

Rather than serving as a source of sup- join a gang and offered sex by drug p. 13). The authors noted that “adoles-

port, families and the home environ- addicts for money” (Miller et al., 2002, cents who have low impulse control

ment were often cited as major stres- p. 383). and a high desire to be popular may be

sors in teens’ lives (Tarrant & Woon, Neighborhood stress was common- unable to manage this mass influx of

1995). One study cited four of the nine ly reported as a source of stress. Urban information in a healthy way, and may

major domains adolescents compiled African-American adolescents cited direct the violence expressed in the

as life stressors, including the teen’s “drug dealing and litter on the streets” news and media against themselves”

home, parents, siblings, and extended as two of the top neighborhood stress- (Derouin & Bravender, 2004, p. 15).

family members (Moos, 2002). The es, which was also accompanied by These acts of self-mutilation may be

teens involved in Chandra and many girls voicing “concerns about used by teens as a coping mechanism

Batada’s (2006) study “noted that fam- men” (Chandra & Batada, 2006, p. 6). for managing their stress. To those who

ily conflicts usually involved doing their These teens expressed fear of living in participate in self-mutilating acts, the

homework, cleaning their room, and their neighborhoods and worrying episodes are “depersonalizing events

doing chores” (p. 4). In addition, teens about going out on the streets. Drug occurring during periods of extreme

described family stress as including dealers, older boys hassling girls, and stress or marked anxiety” (Derouin &

“worrying about the well being of fami- gang violence were identified as causes Bravender, 2004, p. 13). These events

ly members,” “being nagged,” and of stress (Chandra & Batada, 2006). may actually serve to escalate levels of

“conflict over family responsibilities with Lau (2002) noted that “poor children anxiety and provide an additional

siblings” (Chandra & Batada, 2006, p. are being exposed to increasing levels source of stress for teens.

376 PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2008/Vol. 34/No. 5

Adolescent Stress through The Eyes of High-Risk Teens

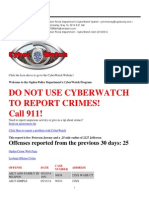

These studies demonstrate the wide Figure 1.

variety of the sources of stress impact- Life Stressors of Teens

ing adolescents. Though Chandra and

Batada’s (2006) study included teens’ Miscellaneous

own words, most of the research was Graduation

quantitative in nature, using estab- College

lished measures of stress and adult per- Friends

spectives in the analysis of results. The Violence/fighting

current study provides a new perspec- Time (lack of)

tive by using teens’ own words to STD’s/AIDS

describe their levels of stress and those Becoming pregnant

stimuli that are associated with the Sex

greatest levels of adolescent stress. Job

Being a mother

Materials and Methods Parents

This qualitative study stemmed Relationships

from a focus group descriptive study Money

exploring teens’ perspectives of sex, School/Grades

pregnancy, and teen births (Herrman, 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

2008). Rich and Ginsburg (1999)

addressed the benefits of gathering a OccurRence

focus group for information, explaining

that it is a natural setting “where ques-

tions are asked of groups that create

the give-and-take atmosphere in which ous high-risk behaviors. Agency per- angst in their daily lives, and resulted in

opinions naturally form” (p. 373). sonnel were responsible for identifying the group discussing the sources of

The qualitative format used in this and recruiting study participants, dis- stress.

study was effective in allowing teens to tributing packets, and collecting com- The Principal Investigator conduct-

open up about their lives and eliciting pleted assent and consent forms. ed all interviews, and made marginal

teens’ responses related to stress. The Employees and volunteers from the and observational notes during and fol-

facilitator asked questions, and the advocacy groups were asked to identi- lowing each interview. Summaries at

teens would discuss their personal fy youth who may take part in the focus the end of each interview provided a

responses, interact with other teens, groups based on their participation in a mechanism for “member checking” or

and share insights related to the per- variety of teen support efforts, includ- reviewing and validating data with each

spectives of others in the group. ing programs focused on preventing group participant (Rich & Ginsburg,

Quantitative methods are helpful in teen pregnancy, assisting teens to deal 1999). Saturation of the data was

“identifying the sources and impact of with social disadvantage, and delaying achieved in the final interviews, when

youth stress,” but “qualitative tools high-risk behaviors. The final purpo- no new information was solicited. Each

would add a unique perspective on how sive, non-random sample included 120 transcription was checked against the

young people themselves discuss and youths from throughout the state, audio-recording for accuracy. The data

prioritize issues” (Chandra & Batada, including 72 females and 48 males were coded and analyzed using the

2006, p. 2). Qualitative methods pro- ranging in age from 12 to 19 years. The Ethnograph v 5.08. The teens’ most

vided a mechanism to determine teens’ mean age of the participants was 16.1 common stressors were then ranked

stressors and examine causal factors years, with 68% of the youths identify- from the most commonly found to the

from the adolescents’ own perspective, ing themselves as African American, least commonly found. Marginal notes,

allowing adults an informed glimpse 19% as Caucasian, 11% as Hispanic, transcripts, and audiotapes were used

into some of the realities of teen life. and 2% as another ethnic origin. to determine the intensity of responses

Approval for this study was Seventeen focus groups were con- related to stressors in addition to the

received from the Institutional Review ducted over a span of six weeks. Each frequency of responses.

Board (IRB) at the local academic insti- group had 3 to 15 participants, and the

tution. Due to the sensitive nature of the interviews averaged 40 minutes in Results

material and the vulnerability of youth, length. One focus group included preg- In qualitative research, the results

careful attention was paid to the nant girls, 1 included teen fathers, 3 are often best understood through the

recruitment of the teens and to the con- had teen mothers, and 12 were com- words of the participants, in this case,

sent/assent processes. High-risk youth posed of non-parenting teens. The the teenagers themselves. The stress-

in the state of study were the popula- non-parenting groups included 4 ful aspects of the teens’ lives emerged

tion for this study, selected to inform female groups, 2 male groups, and 6 as themes from the data. Each of the

nursing and policy interventions and with boys and girls. The focus groups stressors was ranked from most com-

glean new information about teen per- were conducted in private conference mon to least common using Microsoft

ceptions of the stress experienced by rooms and were recorded using a Excel®. The frequency of the most

this cohort. Focus group participants handheld digital recorder, saved to a commonly noted stressors is found in

were solicited from school-based well- CD-ROM, and transcribed verbatim. Figure 1. The most frequently noted

ness centers, health services, churches, The interviews included ice-breaker stressor was school, followed by

teen support groups, and non-profit ado- questions, including “Tell me about money, relationships, and parents.

lescent programs. These sites served your life as a teen right now,” and The following is a discussion of these

teens considered at risk for negative “What are some of your concerns as a stressors with exemplary quotes.

behaviors, whether by self-report, teen?” These prompts led to various School. The greatest stressor dis-

demographics, or referral due to previ- probing questions about stress and covered in this study was school and

PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2008/Vol. 34/No. 5 377

its related components. Maintaining pictures, class dues, SATs, prom tick- significant stress in her life. Demands

good grades, passing their classes, ets, tuxedo rental, and a prom dress like these were interpreted as difficult

making it to graduation, and being were all listed as adding to their stress. by several teens given that they got up

accepted into college were all worries With these expenses in mind, the early in the morning, went to school

that the students cited as stressors. overall biggest complaint heard all day, and then came home and were

One student admitted to “stressing repeatedly was “how to get it.” This asked to do chores. This was a prime

over like whether I’m gonna pass or was especially true of young parents example of how various stressors tie

not, or your grades.” For some, this who suddenly found themselves need- into one another in which schoolwork,

stress existed because they found ing to pay for daycare and to purchase cleaning the house, and fatigue all

school challenging on a normal basis, diapers, wipes, formula, and other created a difficult situation.

while for others it was because they miscellaneous items that were neces-

took on increased challenges. For sary for raising a baby. For example, Discussion

example, one student mentioned that one young mother stated, “Today I The teens involved in the focus

things in school were more difficult just found out that my daycare bill is groups ranked school as their number

because of the fact that he “took a lot $120.93, and I’m like, how am I gonna one stressor in life. This held true for

of harder classes this year, so it’s pay that?” As is evidenced by the ado- all grade levels and both genders,

hard.” lescents’ statements, money caused a demonstrating that school, along with

Seniors taking part in this study large amount of stress in their lives, its associated workload and worries,

had an additional group of stressors which is then compounded even fur- caused stress for these teens. These

than the rest of the participants. They ther for some by parenting. results coincided with the literature as

cited the increased pressure of keep- Relationships. Participants dis- school being teens’ main stressor

ing up with school and graduating, cussed the troubles they were having (Chandra & Batada, 2006; Miller et

stating that it adds “a lot of pressure both with their friends and significant al., 2002; National Campaign to

your senior year ‘cause you wanna others. Many females seemed to have Prevent Teen Pregnancy, 1999). In

graduate with your class…you don’t problems with young men either addition, several of the other stressors,

wanna be left behind.” At this point in “cheating on them” or “lying” to them. including money, relationships, and

time, the seniors also “have to think For instance one girl noted that “they parents, were in concert with those

about – getting scholarships, looking say that you’re the only one they identified in the literature (Chandra &

for colleges, [and] start writing your messing with and then they’re lying, Batada, 2006; Green et al. 2003; Lau

resumes and stuff.” Another student [you] find out they mess with some- et al, 2002, Miller et al., 2002). Being

said it best when stating that senior body else.” Another comment indicat- a mother also ranked highly as a

year was “the time to act right” if you ed that “guys will tell you one thing, stressor, validating the stressors antic-

have not in the previous three years. then it’s another thing.” Many of the ipated associated with being a young

“Pulling themselves together” and girls demonstrated signs of stress mother (Herrman, 2008).

“staying on track” in order to graduate when merely speaking about these The participants often used the

were very important to many of the relationships and the young men’s term “pressure” to describe their

students. In the interviews, students behavior. Two young women men- stress. This referred to “pressure”

also brought up the fact that depend- tioned trouble from guys “trying to from parents to complete chores or

ing on one’s job, “it’s hard to make pressure you” and who “just don’t get good grades, from teachers to

money, even with a bachelor’s degree know when to stop.” Conversely, hand in assignments, from friends to

today,” so with just “a high school young men stated that “relationships” always be available on request, or

diploma, you ain’t making nothing.” were stressful when asked about their from significant others. Ethier et al.

The discussion of school and later life stressors. More specifically, “girl- (2006) noted that the word “pressure”

work success led into a discussion of friends get on my nerves” said one was used by teens when describing

money. boy. The overall feeling among the the duress placed on teens to partici-

Money. The teens’ financial status males regarding relationships was pate in sexual activity or to describe

was an issue in their lives. Depending best stated by one young man, who the need to compare one’s personal

on whether they had a baby to sup- said that girls were “nothing but in the behavior to peers. “Pressure” was a

port, were planning to put themselves way sometimes.” Topping off the dis- word that was consistently cited in

through college in the upcoming cussion on relationships was one male other resources; this theme pervaded

years, or just wanted extra spending who stated, “Girls ain’t worth my trou- the adolescents’ expressions of stress

money, obtaining money to meet their ble or my time.” both in this study and in the literature

needs was perceived as difficult. Parents. Several participants re- (Chandra & Batada, 2006; Miller et

Adolescents verbalized the fear of debt ferred to parents as sources of stress. al., 2002).

if they did not learn sound budgeting One teen discussed her father, stating, Another noticeable trend among

skills. Some teens were able to work “He don’t realize how much pressure the answers given by the teens were

and manage school, but were still find- he puts on me.” A second girl references to the emotions inherent in

ing themselves low on cash due to the expressed stress about her mom, stat- their daily lives. For example the teens

many demands for money in their ing, “I’m scared of my mom.” Another often spoke of being “worried” about

lives. For example, respondents noted teen commented that her parents exams or grades, graduation, college,

“every paycheck that is coming in “make me sick sometimes.” One par- getting pregnant, or simply the future.

right now, I am saving it, and it already ticipant explained that her parents’ Some voiced concerns of doubt, while

has an owner” and “It’s going right daily after-school request of her to others talked about being “upset” or

back out.” Some of the teens shared “fold up the clothes, and clean the “mad.” For instance, to sum up the

that they were in search of money to bathroom, and make sure that every- stressors experienced in the relation-

pay for common high school memo- thing’s cleaned before they get home ship with her parents, one girl stated,

rabilia, activities, and other necessi- at like 4:00 or 5:00, and if it’s not “Oh my gosh, that makes me so

ties. For instance, a class ring, school done…oh my, you’re in trouble” posed mad!” Comments the teens gave

378 PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2008/Vol. 34/No. 5

Adolescent Stress through The Eyes of High-Risk Teens

expressing their emotions of fear or Clinical Implications effectiveness of youth-based initia-

disdain when discussing their families Appreciating what teens reported tives. Stress management programs

included, “I’m scared of my mom,” regarding the stress in their lives leads to enhance coping, increase resiliency

“To me, family is foul,” and “They to numerous measures that can be resources, increase optimism, and for-

make me sick sometimes.” As was taken to aid them in dealing with those tify community supports may be

seen here, the focus group format stressors. First and foremost, adults effective in assisting teens to deal with

allowed the teens to be open and say need to be aware of the stresses that stress (Tussaie et al., 2007).

what they truly felt without needing to confront teens. This study provided Simply convening youth to specif-

hold back. This was also evident in the important data related to the teens’ ically deal with stress or facilitating the

teens’ enthusiasm, with many of the

students jumping in with answers to

questions before the entire question

urses, as well as other adults, may make a

had even been asked. The comments

they then made were often times very

emphatic in nature. For example,

when one girl quickly exclaimed that

N difference by encouraging all teens, no

matter their level of stress, to seek out and talk

“boys!” were a stressor, the next cou- to their parents or another adult role model

ple responded with “Yes! Oh my

[gosh]!” and “Yeah, that is stressful.”

with whom they are comfortable.

Responses like these were seen fre-

quently throughout the interviews.

Despite the fact that the data on own perception of the stress experi- discussion of stress in already estab-

stress found here were taken from a ence and the sources of stress they lished group meetings may provide

teen pregnancy prevention study, it encounter. Many adults feel that since the opportunity for teens to ventilate

provided insight into the lives of teens the teens have not yet entered adult- concerns, receive peer and adult

and the daily stressors they face. The hood, their lives are stress-free. The leader support, and pursue healthy

teens’ stressors built upon each other, realization that teens experience stress coping mechanisms to manage the

causing greater cumulative stress in and the origins of those stressors may stress inherent of teen life. Support

their lives. Teenagers expressed feel- assist adults to empathize with teens groups designed to assist teens to deal

ing overwhelmed by their studies and and enhance communication between with a variety of issues, including loss,

schoolwork. They were distracted by adults and teens. For many teens, substance abuse, chronic illness, or

troubles with their friends and signifi- adults contribute to the high-stress violent behaviors, may benefit from

cant others while attending school. levels experienced. Disseminating discussions framed within the context

Upon being dismissed from school, information about common stresses of the universal nature of stress, the

they returned home to complete all of and their causes to teens, youth advo- recognition of the teen years as stress-

the required tasks assigned by their cates, and families with adolescents is ful, and the need to learn ways to cope

parents, while putting off studying and of prime importance. Because stres- with stress on a progressive and

homework. Some teens also had to sors are believed to lead to chronic ill- developmental basis (Tussaie et al.,

juggle a job in order to manage the ness and due to the potential for ado- 2007). Methods to enhance stress

costs of a new baby or simply the lescents to live long lives, adults need resilience, including assisting teens to

costs of living. to be attentive to teen levels of stress use cognitive reframing to interpret

and means to assist adolescent cop- stressful stimuli, informing parents of

Limitations ing (Goodman et al., 2005). their need to provide support to teens

The sample of this study repre- The key sources of stress offer during stressful times, and the provi-

sents teens considered to be at risk for insight into the world of teens and the sion of psychological counseling as

both negative youth behaviors and means to intervene with teens about needed, should be employed to

pregnancy, and all participants were the stress experience. It is important to reduce the stress experience (Tussaie

from a single state, limiting its gener- recognize the role of school in a teen’s et al., 2007).

alizability. The timing of the study was life, as several other sources also iden- Researchers have explored the

during the last month of the school tify school as a major stressor in their relationship of optimism with increased

year in finals week with graduation on lives (Chandra & Batada, 2006; Green abilities to deal with the stressors con-

the horizon, which may have con- et al., 2003, Lau, 2002; Miller et al., fronted in daily life (Finkelstein et al.,

tributed to the emphasis on school as 2002). Intervention is necessary to 2007; Tussaie et al., 2007). Assisting

the highest priority stressor. Although address these stressors, and adults teens to identify positive aspects of

it is not known whether school was should assist teens to cope with school their lives, providing role models who

truly paramount or if the time of and its associated stressors. have surmounted similar challenges

intense emphasis on studying influ- It may be extremely beneficial for of social disadvantage, and offering

enced school’s high ranking, much of teens to have access to stress man- opportunities for success and happi-

the research in the literature cited agement programs. Developing such ness may help teens develop the

school as a major source of stress in programs in their schools, recreation resilience to handle life stressors

adolescents’ lives (Chandra & Batada, centers, and/or churches, or with the (Finkelstein et al., 2007).

2006; Green et al., 2003, Lau, 2002; help of pediatric nurses in hospitals, Nurses, as well as other adults,

Miller et al., 2002). The qualitative would be a valuable resource to aid may make a difference by encourag-

nature of this study limits the ability to them in learning to manage their ing all teens, no matter their level of

generalize findings to a different popu- stress. Constructing a stress manage- stress, to seek out and talk to their

lation but does offer insights to the ment program based on teen percep- parents or another adult role model

unique perspectives of teens identified tions of stress may lend validity to the with whom they are comfortable.

as high risk. program content and enhance the Having a role model to talk to and

PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2008/Vol. 34/No. 5 379

confide in during the teen years has ease prevention (Herrman, 2008). Derouin, A., & Bravender, T. (2004). Living on

positive benefits (Tussaie et al., Further studies should be done to the edge: The current phenomenon of

2007). Pediatric nurses may have an compare a larger and more diverse self-mutilation in adolescents. MCN The

impact on a young person’s life sample of high-risk and low-risk teens American Journal of Maternal Child

Nursing, 29(1), 12-20.

through counseling teens and their to explore their array of stressors. Ethier, K.A., Kershaw, T.S., Lewis, J.B., Milan,

families on the value of a mentor. Youth stressors should be examined S., Niccolai, L.M., & Ickovics, J.R. (2006).

They can also help adults build rela- for their role in high-risk behaviors, Self-esteem, emotional distress, and

tionships with teens based on adoles- such as substance abuse, violence, sexual behavior among adolescent

cents’ needs, developmental norms, sexual behavior, and defiance of rules females: Inter-relationships and temporal

and associated stressors. Teens may and laws (Finkelstein et al., 2006). effects. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38,

find that when working with a nurse, They should also be investigated for 268-274.

as someone they can trust, they can their relationship to adolescent mental Finkelstein, D.M., Kubzansky, L.D., Capitman,

become better able to deal with the health issues, including suicide, J., & Goodman, E. (2007). Socioeco-

nomic differences in adolescent stress:

stress in their lives. In their roles as depression, self-mutilation, and anxi- The role of psychological resources.

youth advocates and parent/teen edu- ety. The impact of stress on sleep, Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(2),

cators, pediatric nurses may commu- nutrition, dealing with peer pressure, 127-134.

nicate common stressors to parents school performance, and quality of life Finkelstein, D.M., Kubzansky, L.D., &

as a means to enhance communica- should be topics of research. Future Goodman, E. (2006). Social status,

tion and parents’ capacities to serve research to discover effective coping stress, and adolescent smoking. Journal

as youth role models (Herrman, mechanisms used by teens and the of Adolescent Health, 39(5), 678-675.

2005). means to enhance coping in teens Goodman, E., McEwen, B.S., Dolan, L.M.,

Teens also need to be told the with varying levels of stress and con- Schafer-Kalkhoff, T., & Adler, N.E.

(2005). Social disadvantage and adoles-

importance of being assertive with current manifestations of stress on cent stress. Journal of Adolescent

boyfriends or girlfriends when they their lives should be priorities for pedi- Health, 37, 484-492.

start feeling pressured to engage in atric nurses. Above all, nurses, adult Green, S.E., Holohan, E., & Feldheim, A.

any activity, including sexual behavior, role models, and parents should con- (2003). Stress in the family. Retrieved

for which they may not be ready. sider the stress levels experienced by August 26, 2008, from http://www.ecb.

Discussions related to gender identity, teens, develop ways to reduce those org/guides/pdf/CE_68_05.pdf

difficulties with relationships, personal stress levels, continue to explore the Herrman, J. (2005). The teen brain as a work

attitudes and activities, and high-risk impact of stress on today’s youth, and in progress: Implications for pediatric

behaviors may be initiated from the design interventions to assist teens to nurses. Pediatric Nursing, 31(2), 144-

148.

disclosure of these research findings cope with a complex world. Herrman, J. (2008). Adolescent perceptions of

of the common stressors of adoles- teen births. Journal of Obstetrical,

cents. Stressors associated with sexu- Gynecological, and Neonatal Nursing,

al activity and decision making may 37(1), 42-50.

provide the springboard for further References Lau, B.W.K. (2002). Does the stress of child-

discussion of responsible sexual Chandra, A., & Batada, A. (2006). Exploring hood and adolescence matter? A psy-

behavior, the role of relationships in stress and coping among urban African- chological perspective. The Journal of

American adolescents: The shifting the the Royal Society for the Promotion of

sexual activity, abstinence, compre- lens study. Preventing Chronic Disease:

hensive sexuality education, and teen Health, 122(4), 238-244.

Public Health Research, Practice, and Miller, D.B., Webster, S.E., & MacIntosh, R.

pregnancy/sexually transmitted dis- Policy, 3(2), 1-10. (2002). What’s there and what’s not:

Measuring daily hassles in urban African-

American adolescents. Research on

Social Work Practice, 12(3), 375-388.

Moos, R.H. (2002). Life stressors, social

Adolescence: A Select

ion of Issues resources, and coping skills in youth:

nursing education (CNE)

The purpose of this continuingunderstanding about a selection of

nurse’s

series is

1. Discuss the importance

OBJECTIVES

of maintaining a basic

understanding

Applications to adolescents with chronic

to increase the pediatric

disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health,

adolescence. today’s adolescent.

issues of importance in fraught with change,

a transition of the issues affecting a group of high-risk

Adolescence is a period issues in adoles- common stressors for

adulthood. Although many others, such as 2. List the three most

between childhood and years, adolescents.

the same throughout the with overweight for rural

adoles-

cence have remained the number of over- 3. List three factors associated

the enormous increase in

34, 22-29.

the need to address become a pri-

have only in recent years cents. al deter-

weight or obese teenagers, issues that affect adolescents can help social-cultural, and environment

on 4. Describe behavioral,

ority. Keeping updated

adolescents through

this exciting but often individuals among adolescent

minants of overweight

pediatric nurses guide

Latino/Hispanics. ion of Issues

Adolesence: A Select

stormy time. adoles- keep current on

of three articles that address for pediatric nurses to

This CNE series consists

cent issues. The first

ined adolescent stress

second article reports

article presents findings from

through the eyes of high-risk

the results of a study

a study that exam-

teenagers.

that sought to determine

demographic vari-

The

5. Identify opportunities

adolescent issues.

for X.X contact

c. Acculturation

This offering

is provided by Anthony

to the subtle

refers hours

J.

b. Private health insurance can have

protective effect on the incidence

a

of

National Campaign to Prevent Teen

overweight and obesity, following referrals is an

the association between

weight in Latino/Hispa

nic adolescentsthe

Which of of

11. frequency

and

ables, elevated blood pressure, articleillustration

in rural adolescents. The

third reviews the

and

this healtha.matter

thehealth carestatements

offers

Latino

most

cultural perceptions

of literature

potential strategies

population?

efficaciously

is the

.

Jannetti, Inc.

on over- with Anthony J. Jannetti,

nursing education

accepted language Commission d.

process of change

thinking through

the American

surebywith another

on Accreditationabove

All of theInc.

in behavior and

culture.

(ANCC-COA).

as a provider of continuing

contact and expo-

Inc is accredited

Nurses Credentialing

of continuing edu-

overweight.

income, and adverse health

can all work synergisticall

low-

c. Higher rates of overweight, effects

Center's

y to the dis-

Pregnancy. (1999). What about the

nurses can use to address

Spanish is an approved provider

spoken in most homes.

b. Chubby children are a

Anthony J. Jannetti,

e. None the above

ofBoard of Registered Nursing, CEP No. 5387. advantage of the individual.

sign of health cation by the California publication in the continuing education series

teens? Research on what teens say

Take the CNE

Articles accepted for d. All of the above

ASSIGNMENT in the standard Pediatric

used screening

are reviewed

and prosperity. 13. What that widely

is the most

manuscripts e. None of the above

a sign of are refereed

foods arethe otherchildren

with and to identifyin the journal. RN,

articles appearing

c. Highly saturated

J. (2008). Adolescent

stress through Nursing review for teens

toolprocess Rollins, PhD,

and edited by Judy A.

LaRue, D., & Herrmann, Pediatric Nursing,

eyes of high-risk teens.

Adams, M., Carter, T.,

Lammon, C., Judd,

(2008). Obesity and blood

wealth.34(5), 375-380.

d. Public

pressure tion

Nursing, e.

J., & Wheat,

health insurance

A., Leeper,

in rural adolescents

of prestige.

trends

(5), 381-386.

34None of the above

J. indica-

is an

Pediatric Nursing

FAAN, Pediatric

was reviewed

This testweight concerns?

associate editor, and Veronica

a. Skin foldseditor.

Nursing

b. Waist circumference

and gender

D. Feeg,15. is important to intervene

PhD,It RN,

tions for overweight in

Environmentally, what factors

indirectly contribute to this

in predisposi-

Latino children.

directly or

tendency?

about teen pregnancy: A focus group

Earn X.X Contact Hours

over a decade. Pediatric c. BMI for age

report. Washington, DC: Author.

nic adolescents: of screen time

Overweight in Latino/Hispa a. Less than 2 hours/day

Harrington, S. (2008). and implications.

nursingstatement

Pediatricthe term

defines d. Insulin levels drop-out rate

Scope of the problem 12. What best b. Elevated high school

e. Fasting blood sugars activity and energy

acculturation? c. Increased physical

posttest on

Nursing, 34(5), 389-394.

of behaviors

a. Acculturation is a group QUESTIO ic status is a thread that

practices of NS 14. Socioeconom

expenditure

1. According to this

study, adolescents

that speak to the cultural

a population. One way teens may deal with stress

4. a private the

b. Acculturation isthrough

members

experience

influences

is

many The

8.

health status. Which

practice of “cutting.”

of a partic- statements

a cop-

decisions

current

related toof Adams

analysis

of the following

leagues’ study was based

are true?

the following information?

d. and

e. which

on

the above

All ofcol-

None of the above

Puskar, K.R., & Rohay, J.M. (1999). School

cited several stressors

as particularlyamongst familyExperts believe teens use this as a. Economic insecurity can detrimentally

a. Ten years of observations

intense during the

the following stressors

from this study cite as

teen years. Which

did the teens

their number

of culture.

ular

one

ing mechanism because

a. Allows individuals to

b. Satisfies a need to feel

cutting:

express anger.

pain.

impact food choices.

b. Kindergarten through

dents

c. Repeated cross sectional

12th grade stu-

design PED J806 relocation and stress in teens. Journal of

pages 395 and 396

stressor? to respond to

of Issues

A Selection

the individual design

a. Parents

b. School

c. Relationships

Answer Form: Adolescen

Check the box next to

1. I A 2. I A 3.

c. Helpsce:

d. the

IA

anxiety.

correct

Provides

answer. for past mis-

a punishment

4. I A 5. I A 6.

takes.

I

I A 7. I A 8. I A

I B I B 9. I

d. Traditional longitudinal

e. a and c

B

9. I A 10. I A 11.

According

I A 12. I A 13. I A

I B Baur,Iand

ItoB Lobstein,

I

B UauyI B

C I C

IB

IC

14. I A 15. I A

IB

IC

IB

IC

School Nursing, 15(1), 16-22.

e.I BNone ofIthe B above. B I Cis theIprevalence of being

C ID ID

d. Money IB I ID

Rich, M., & Ginsburg, K.R. (1999). The reason

IB IC C what

IC (2004), ofD5 to 17I

I I Drange I D

e. Job IC IC IC I I inD the age IE IE

IC I D from I D D

overweight IE IE IE

ID

I D demonstrate slower recovery I IE IE

ID I D5. Teens IE IE E worldwide?

years

to this study, which of the fol- I E I E

stressful IE

events.

2. According IE a. 5% TIONS

lowing words do teens

most commonly POSTTEST INSTRUC

a. True ING: b. 6%

and rhyme of qualitative research: Why,

and earn 2.0

for “stress?” E THE FOLLOW

use as a synonym b.COMPLET

False and check the

by others.

c. 10% 1. Select the best answer answer form.

a. Worry

This test may be copied for usehave d. 12% correspond ing box on the

2004, how much as your

b. Hassle 6. Between 1980 and increased? ____________________

e. 15% __

Retain the test questions

when, and how to use qualitative meth-

__________

obesity rates

__________

c. Anxiety Name: ____________________ the adolescent record.

d. Pressure 5.0% to 17.4% ____________________ results are cor-

a.__________ ____________________ 10. Which of the following betweenthe information requested in

e. Strain Address: __________b. 5.0% to 13.9% rect related to the association

__________ 2. Complete

__________ characteris-

6.5% to 18.8%

c.__________ ____________________ obesity and demographic the space provided.

__________

3. A nurse is designing

ment program for teens

a stress manage-

and plans the

____________________

d. 6.7% to 18.8%

_______________State:

________ Zip: tics? ___________

the answer form or a copy

greater risks

adolescents are3.at Detach

of the

Pediatric ods in the study of adolescent health.

contact hours.

City: e. 7.0% to 19.1% a. Older and mail to:

intervention with the knowledge

that: Strongly

of being overweight.

answer form

Strongly Jannetti Pub-

discuss their agree higher, CNE Series,

Nursing

a. Teens are reluctant to 7. According to the

literature, becoming

disagree b. Females have a significantly Inc.; East Holly Avenue

Box

stress and coping mechanisms.

b. Teens do not find adult

effective in learning to deal

Evaluation

role models

1. The objectives relate

with

purpose/goals of the

obese in adolescence

onetoto thewhich

education activity.

problems?

can predispose

overall of the following health

1 2 3 5 being overweight.lications

4risk of

c. Nonwhites are at greater

overweight.

being NJ 08071-005

risk ofPitman,

56;

check or money order for $XX.00

Jannetti

income increases, over- Publications Inc.

6 with a

payable to Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 371-

stress. The activity met the stated objectives. 3 d. 4As family

5 (nonsubscriber).

a. Hypertension a basic 2

(subscriber) or $XX.00

378.

2.

means 1

c. Teens prefer to use unhealthy a. Discuss the importance b.

of maintaining

Dyslipidemia today’s weight increases.

to deal with stress. the issues affecting e. All of the above. be postmarked by

e the levelunderstanding of c. Pneumonia 4. Test returns must pass the test

d. Adults often underestimat adolescent. resistance

d. Insulin stressors 1 2 3 4 5

October 31, 2010. If you

of stress teens experience. b. List the three most common for a group for X.X

e. a, b, and d (70% or better), a certificate

e. a and b.

c.

of high-risk adolescents.

List three factors associated

rural adolescents.

with overweight for

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

contact hours will be

Anthony395J. Jannetti, Inc.

awarded by

for processing.

Tarrant, B., & Woon, A. (1995). Adolescent sui-

2008/Vol.

Describe behavioral, 34/No.and

social-cultural, 5 environmental Please allow 6-8 weeks the date that

cide: An overview. Australian Journal of

d. r-October

Septembe individuals among adolescent For recertification purposes,will reflect the

PEDIATRIC NURSING/ determinants of overweight

Latino/Hispanics. 2 3 4 5 contact hours are awarded

keep current 1

f. Identify opportunities

for pediatric nurses to date of processing.

on adolescent issues. 3 4 5

Emergency Care, 2(1), 26-30.

1 2

3. Home study format

was appropriate.

1 2 3 4 5 Test Scoring,

5 fees:

CNE Awarding/Recording

relevant to my practice. 1 2 3 4

4. The content was needs.

5. The content met my used to complete reading

6. How much time was

_______

I $XX.00

PN Subscriber

assignment and posttest:_______

a. Less than 1 hour

c. 2-3 hours

Comments ____________

_______

____________

b. 1-2 hours

d. 3 hours or more

________________________

_______

__________________

__

Nonsubscriber

I $XX.00

Exp. Date __________________

_______ Tusaie, K., Puskar, K., & Sereika, S.M. (2007).

________________________

2008/Vol. 34/No. 5

Signature ____________

396

________________________

PEDIATRIC NURSING/

September-October

A predictive and moderating model of

psychosocial resilience in adolescents.

Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 39, 54-60.

380 PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2008/Vol. 34/No. 5

View publication stats

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Violation of Human Rights of Women in South Asia: A Case Study of Punjab 1978-1992Dokument88 SeitenViolation of Human Rights of Women in South Asia: A Case Study of Punjab 1978-1992ਮਨਪ੍ਰੀਤ ਸਿੰਘNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cluster Based Training On Gender and Development Awareness: Narrative ReportDokument1 SeiteCluster Based Training On Gender and Development Awareness: Narrative Reportmichelle c lacad50% (2)

- The Making of Political Identities: Edited by Ernesto LaclauDokument33 SeitenThe Making of Political Identities: Edited by Ernesto LaclauYamil CelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- DEPED Child Protection PolicyDokument75 SeitenDEPED Child Protection PolicyJENNIFER YBAÑEZ100% (1)

- PaperDokument15 SeitenPaperBarnali SahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daniel Jordan Smith CV (2014)Dokument19 SeitenDaniel Jordan Smith CV (2014)Naveen ChoudhuryNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs Quintos G.R. No. 199402 November 12, 2014Dokument18 SeitenPeople Vs Quintos G.R. No. 199402 November 12, 2014herbs22225847Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 4 Prof Ed 13Dokument6 SeitenModule 4 Prof Ed 13Karl N. SabalboroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child MarriageDokument30 SeitenChild Marriagenurauni48Noch keine Bewertungen

- BARTELSON, Jens - War in International ThoughtDokument253 SeitenBARTELSON, Jens - War in International ThoughtMarcelo Carreiro100% (1)

- SouthcarolinaDokument5 SeitenSouthcarolinaapi-280868990Noch keine Bewertungen

- The RBG Blueprint For Black Power Study Cell GuidebookDokument8 SeitenThe RBG Blueprint For Black Power Study Cell GuidebookAra SparkmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opp ReportDokument1 SeiteOpp Reportgrahamwishart123Noch keine Bewertungen

- ORGANIZING COMMUNITY - Jeanette L. Ampog PDFDokument21 SeitenORGANIZING COMMUNITY - Jeanette L. Ampog PDFIrene AnastasiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PRESS RELEASE Human Trafficking Research FindingsDokument1 SeitePRESS RELEASE Human Trafficking Research FindingsCatholic Charities USANoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs MadsaliDokument3 SeitenPeople Vs MadsaliAshley CandiceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Travesty of Justice IndiaDokument5 SeitenTravesty of Justice IndiaSurinderjit SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- All About The Hathras Case - IpleadersDokument1 SeiteAll About The Hathras Case - IpleadersBadhon Chandra SarkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cyberwatch EmailDokument4 SeitenCyberwatch EmailJeremy PetersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Book PerspectivesOnViolenceAndOther PDFDokument246 Seiten2016 Book PerspectivesOnViolenceAndOther PDFSoumi BanerjeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Childrens Strategy South Tees Hospitals PDFDokument47 SeitenChildrens Strategy South Tees Hospitals PDFSimona TironNoch keine Bewertungen

- Russia - Committee 4 - Ana Position PaperDokument2 SeitenRussia - Committee 4 - Ana Position Paperapi-311096128Noch keine Bewertungen

- Violence & MediaDokument6 SeitenViolence & MediaJacobin Parcelle100% (4)

- Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) TrainingDokument2 SeitenCountering Violent Extremism (CVE) TrainingRoss Calloway100% (1)

- Assessing Damages and Jurisdiction in People v CatubigDokument2 SeitenAssessing Damages and Jurisdiction in People v CatubigAngela Louise SabaoanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Campaign For The Prevention of Child MarriageDokument15 SeitenGlobal Campaign For The Prevention of Child MarriageMelisa NaeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muňoz National High School-Annex: Schools Division of Sciencce City of MuňozDokument1 SeiteMuňoz National High School-Annex: Schools Division of Sciencce City of MuňozWilliam BalalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender-Based Violence SummaryDokument3 SeitenGender-Based Violence Summaryapi-537730890Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Table Breaks Down Updates Between Anti-Carnapping ActsDokument3 SeitenComparative Table Breaks Down Updates Between Anti-Carnapping ActsMark RojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breaking the silence on sexual harassmentDokument11 SeitenBreaking the silence on sexual harassmentSudheer VishwakarmaNoch keine Bewertungen