Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Acute Abdomen

Hochgeladen von

E. Lisette SandovalCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Acute Abdomen

Hochgeladen von

E. Lisette SandovalCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PEER REVIEWED

ACUTE ABDOMEN IN

DOGS & CATS

Step-by-Step Approach to Patient Care

Garret Pachtinger, VMD, Diplomate ACVECC

A

cute gastrointestinal (GI) distress and abdominal t Arched back or “prayer position” (Figure 1)

pain require prompt evaluation and immediate t Abdominal distension (Figure 2)

intervention to prevent further morbidity and mor- t GI signs, including vomiting, diarrhea, hypersalivation,

tality. The most important question is: Does the patient retching, or anorexia

require medical or surgical management? If surgical t Poor perfusion parameters, including pale mucous

management is warranted, the clinician will need to time membranes (Figure 3), prolonged capillary refill time,

the surgery to decrease further morbidity and maximize and poor pulse quality

survival. t Tachypnea and/or tachycardia.

Acute abdominal pain is associ-

ated with a variety of underlying

causes (Table 1), and results from:

t Stimulation of pain fibers—A-del-

1

ta and c-nociceptors—within the:

» GI tract (ie, submucosa, mus-

cularis or peritoneal lining of

hollow viscera)

» Abdominal organs (ie, capsule

distension and stretching of

spleen and liver)

» Nerves, muscle, fascia, and skin

associated with the abdominal

wall.

t Pain referred from extra-abdom-

inal sites.1

STEP 1. Determine if clinical 2

signs are associated with acute Figure 1. Abdominal stretching or the classic

abdominal pain. “prayer position”

Clinical signs associated with acute Figure 2. Severe abdominal distension due to

abdominal pain may include:2 ascites

3

t Restlessness and/or guarding or Figure 3. Pale mucous membranes

splinting of the abdomen

14 Today’s Veterinary Practice September/October 2013

ACUTE ABDOMEN IN DOGS & CATS |

TABLE 1. Acute Abdominal Pain:

Differential Diagnosis List2 TABLE 2. Patient Status: Examples of

Abdominal t Abscessation/infection Diagnoses & Therapeutic Approach

Lymph Node t Neoplasia

Disease EXAMPLES OF THERAPEUTIC

DIAGNOSES APPROACH

External GI/ t Fasciitis

Abdominal t Herniation (umbilical, inguinal, Nonsurgical

Structures abdominal wall) Acute pancreatitis r IV fluid therapy

t Intervertebral disk disease Gastritis r Medications, including

t Myositis Gastroenteritis analgesics, antiemetics,

t Steatitis gastroprotectants, and

GI Tract t Gastric dilatation–volvulus prokinetics

Lesions t GI neoplasia, obstruction, Emergent

perforation, or ulceration Cardiovascularly stable Surgical candidates that

t Intestinal torsion hemoabdomen can:

t Intussusception Intestinal obstruction with- r Tolerate a delay in anes-

t Mesenteric thrombosis or torsion out evidence of peritonitis thesia and surgery

t Pyloric outflow obstruction

Uroabdomen, with place- r Require medical therapy

Pancreatic t Infarction of the pancreas ment of temporary urinary to optimize health status

Disease t Pancreatic abscess or peritoneal dialysis cath- prior to anesthesia and

t Pancreatitis eter surgery

Peritoneal t Bile peritonitis Critical

Cavity t Hemoperitoneum

Gastric dilatation–volvulus Patients that require:

Disease t Pneumoperitoneum

Mesenteric torsion r Rapid assessment and

t Septic peritonitis

Septic peritonitis treatment

t Uroperitoneum

Uncontrolled hemorrhage r Immediate emergency

Reproductive t Pyometra abdominal surgery; delay

Tract Disease t Testicular abscess or torsion will increase morbidity

t Uterine rupture or torsion and mortality

Reticulo- Hepatobiliary Disease

endothelial t Biliary tract rupture, mucocele,

System or obstruction STEP 2. Categorize patient as nonsurgical, emergent,

t Hepatic abscess, hepatitis, or or critical.

cholangiohepatitis When a patient presents with concern for GI distress and acute

t Liver lobe torsion abdominal pain, I try to place them into 1 of 3 categories:

t Neoplasia nonsurgical (medical), emergent, or critical (Table 2).

Splenic Disease Some cases are fairly straightforward; for example, the

t Fracture

4-year-old standard poodle that presents with acute onset

t Hematoma

t Neoplasia of panting, pacing, nonproductive retching, and distended

t Thrombosis abdomen. Gastric dilatation–volvulus (GDV) is the most likely

t Torsion diagnosis. However, other cases present with clinical signs

consistent with acute abdomen but too vague to identify a

Urinary Tract Prostatic Disease

t Prostatic neoplasia specific diagnosis without further evaluation.

t Prostatitis/prostatic abscess Therefore, use your well-tuned examination and diagnos-

Renal Disease tic skills to determine whether patients require a medical or

t Avulsion surgical approach.

t Calculi

t Infarct STEP 3. Perform triage evaluation and address any life-

t Neoplasia threatening abnormalities.

t Pyelonephritis Triage History

Urethral/Ureteral Disease Important triage information includes:3

t Obstruction t Signalment

t Passage of calculi

» Age: Younger patients may have a different differential list

t Rupture

Urinary Bladder Disease

(eg, trauma, poisoning) compared with older patients (eg,

t Cystitis neoplasia, metabolic disease)

t Neoplasia » Sex: Intact patients may also have a different differential

t Obstruction list (eg, pyometra, prostatic abscess) than that of neutered

t Rupture patients.

» Breed: Breed variations may help guide examination and

September/October 2013 Today’s Veterinary Practice 15

| ACUTE ABDOMEN IN DOGS & CATS

diagnostics, such as a standard poodle with GDV or

TABLE 3. Physical Examination: hypoadrenocorticism versus a dachshund with inter-

Assessment & Findings vertebral disk disease

t Presenting complaint

VITAL SIGN ASSESSMENT t Time of onset

Cardiovascular r $BQJMMBSZ SFGJMM UJNF t Progression since initial onset.

r )FBSU SBUF SIZUIN

r .VDPVT NFNCSBOFT Triage Examination

r 1VMTF RVBMJUZ A triage examination is a brief, focused, physical evalua-

r #PEZ UFNQFSBUVSF tion that is critical to assess major body systems, which

Respiratory r 3FTQJSBUPSZ SBUF FGGPSU include the cardiovascular (ie, circulation and tissue per-

POTENTIAL FINDINGS fusion), neurologic (ie, brain or spinal cord dysfunction),

respiratory (ie, airway patency, oxygenation), and uro-

Abdominal r "TDJUFT

r 'PDBM TPVSDF PG BCEPNJOBM QBJO

genital (ie, renal function and urinary bladder integrity)

r %JTUFOEFE BCEPNFO XJUI systems. Failure to recognize an abnormality in any system

tympany on percussion (GDV) can result in immediate, life-threatening deterioration of

r "CEPNJOBM NBTT QPTTJCMF the patient.

neoplasia)

r 0SHBOPNFHBMZ STEP 4. Obtain detailed history and perform thorough

Eyes, Ears, r %FOUBM PDVMBS PS PUJD EJTFBTF physical examination.

Nose, Throat r )BMJUPTJT Once the initial assessment is completed and any life-

(EENT) r 4USJOH GPSFJHO NBUFSJBM VOEFS UIF threatening abnormalities addressed, obtain a more thor-

tongue ough history and perform a complete physical examina-

r 6MDFSBUJPO tion.

Lymph Nodes r -ZNQI OPEF FOMBSHFNFOU PS

discomfort Acute Abdomen History

Musculo- r 'SBDUVSFT In patients with GI distress and acute abdominal pain, his-

skeletal/ r +PJOU TXFMMJOH tory should address:

Neurologic r .VTDMF BUSPQIZ t Medication history (both prescription and over the

r 3FGFSSFE TQJOBM QBJO counter)

Skin r &DDIZNPTFT CSVJTJOH t Access to foreign material (indoors and outdoors)

(Integument) r )FNPSSIBHF JO BSFB PG VNCJMJDVT » Abnormal/new food

(Cullen’s sign); may indicate he- » Garbage

moabdomen » Recent abdominal surgery

Respiratory r #SPODIPWFTJDVMBS TPVOET » Toys (both children and pet)

t Trauma

Rectal r .FMFOB PS IFNBUPDIF[JB

t If vomiting present, differentiating it from regurgitation,

r 1FSJ BOBM NBTTFT

r 1SPTUBUF QBJO PS FOMBSHFNFOU coughing, or retching.

r 4VCMVNCBS MZNQIBEFOPQBUIZ t If diarrhea present, characterizing it as large or small

bowel based on color, frequency, and consistency and

Urogenital r Females: Pregnancy, mammary

supplementing with rectal examination.

masses, or vaginal discharge

r Males: Enlarged prostate or pre-

putial discharge Physical Examination Evaluation

Following the triage examination, perform a thorough

physical examination (Table 3).

TABLE 4. Opioid Medications for Acute Abdomen

STEP 5. During history and physi-

Medication Dose Range Frequency Route

cal examination, begin monitor-

Buprenorphine 0.01–0.02 mg/kg Q 4–6 H SC, IM, IV ing patient.

Fentanyl 3–10 mcg/kg/H Constant rate IV An effective veterinary team has

(2–5 mcg/kg initial IV bolus) infusion mastered the art of multitasking.

Fentanyl patch < 10 kg: 25-mcg patch Q 3–4 days; Transdermal To facilitate efficient patient assess-

10–20 kg: 50-mcg patch onset of effect ment, ask support staff to:4

20–30 kg: 75-mcg patch 12–24 H after t Place peripheral IV catheter(s)

> 30 kg: 100-mcg patch application t Initiate intermittent or continu-

Hydromorphone 0.05–0.2 mg/kg Q 4–6 H SC, IM, IV ous electrocardiography for car-

Methadone 0.1–0.4 mg/kg Q6H SC, IM, IV

diac monitoring

t Monitor pulse oximetry and

Morphine 0.5–2 mg/kg Q 4–6 H SC, IM blood pressure

16 Today’s Veterinary Practice September/October 2013

ACUTE ABDOMEN IN DOGS & CATS |

t Evaluate packed cell volume, total protein, blood glucose,

lactate, and electrolytes; determine if azotemia is present.

4

STEP 6. Initiate primary treatment based on findings.

Based on physical examination and initial diagnostic results,

primary treatments may include:

t IV fluid therapy to correct hypovolemia and improve perfu-

sion; administer:

» Balanced isotonic crystalloids (10–30 mL/kg) in incremen-

tal boluses

» Synthetic colloids (hydroxyethyl starch, 3–5 mL/kg) in

incremental boluses

t Supplemental oxygen, if there is labored breathing or abnor-

mal perfusion

t Analgesic therapy:5

» Opioid therapy is most commonly used (Table 4). 5

» Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be

used with caution until the underlying cause is identified.

Their usefulness is limited in hypoperfused patients due

to side effects (renal and GI compromise) and potential

need for surgery.

STEP 7. Perform secondary survey as well as additional

diagnostics.

Laboratory Analysis

t Complete blood count: White blood cell, red blood cell, and

platelet counts

t Serum biochemical profile: Important organ values, blood 6

glucose, and electrolytes

t Pancreatic testing: Pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity test,

lipase, or amylase can be used to evaluate possible pancre-

atitis.

t Coagulation profile: Prothrombin time, partial thromboplas-

tin time, platelet count, and D-dimers

t Urinalysis and urine sediment: Urine specific gravity, pres-

ence of bacteria, and other abnormalities

t Fecal examination: Fecal float and cytology

Imaging Analysis

Radiography to identify or evaluate (Figures 4 through 6):

t GDV or pneumoperitoneum 7

t Presence of foreign material or intestinal pattern consistent

with obstruction, such as small intestinal plication or dila-

tion (Note: Distention of bowel up to 1.6 the height of the

body of L5 is reportedly normal in dogs).

t Poor contrast and detail due to:

» Ascites (eg, carcinomatosis)

» Lack of abdominal fat (eg, cachectic or juvenile patient)

» Mass effect (eg, pyometra or stump pyometra, splenic mass)

» Peritonitis (eg, septic effusion due to ruptured intestinal

viscera).

Abdominal ultrasound to identify (Figure 7):

t GI obstruction Figure 4. Gastric dilatation–volvulus

t Pancreatitis Figure 5. Severe gastric distension due to “food

t Peritoneal effusion bloat”

t Pyometra Figure 6. Large urinary bladder stones

t Specific organ enlargement Figure 7. Ultrasound appearance of small intestinal

t Urinary tract obstruction. intussusception

September/October 2013 Today’s Veterinary Practice 17

| ACUTE ABDOMEN IN DOGS & CATS

8 9 10

Figure 8. Septic suppurative inflammation diagnosing a septic abdomen

Figure 9. Gross surgical appearance of a small intestinal intussusception

Figure 10. Dehiscence of a small intestinal resection and anastomosis

Cytologic Analysis 9. Elevated bilirubin levels compared to peripheral serum

Effusion can be obtained by:6,7 levels

t Abdominocentesis (ultrasound-guided or 4-quadrant 10. Free gas on abdominal radiographs (if radiographs

technique) taken prior to abdominocentesis and patient has not

t Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (for small volume effusion had recent abdominal surgery)

or if ultrasound is unavailable). Once a diagnosis is made, the critical question is: How

Cytologic evaluation of the effusion should include soon should surgery be performed? This decision depends

(Figure 8): on 2 factors:

t Identification of degenerate neutrophils, neoplastic 1. How stable is the patient?

cells, and/or intracellular bacteria 2. What is the underlying diagnosis?

t Nucleated cell count and differentiation among transu- Most patients presenting with an acute abdomen will

date, modified transudate, or exudate require some degree of stabilization prior to anesthesia

t Detection of food material and surgery. For example, in patients with acute abdominal

t Measurement of:8,9 pain and GI distress with hypovolemia, common findings

» Lactate and glucose (compared to plasma in evaluation are acid–base or electrolyte abnormalities, which should

of sepsis) be addressed prior to anesthetic induction.

» Creatinine and potassium (compared to plasma in Clinical judgment is needed to determine the appropriate

evaluation of urinary tract rupture) balance between presurgical stabilization and the amount of

» Bilirubin (compared to plasma in evaluation of biliary time taken before the problem can be surgically corrected.

tract rupture).

STEP 8. For emergent and critical patients, consider

TABLE 5. Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic

indications for surgery: Combinations for Critical Patients

Indications for immediate surgical intervention in critical

COMBINATION 1

patients include (Figures 9 and 10):

Cefazolin, or 20–30 mg/kg Q 8–12 H; IV

Abdominal Conditions Ampicillin 22 mg/kg Q 8 H; IV

1. Complete bowel obstruction Enrofloxacin 10–15 mg/kg Q 24 H; IV

2. GDV Metronidazole 10 mg/kg Q 12 H; IV

3. Inability to medically stabilize intra-abdominal hemor-

COMBINATION 2

rhage10,11

4. Mesenteric volvulus Ampicillin/ 20–30 mg/kg Q 8 H; IV

5. Penetrating abdominal injury sulbactam

6. Splenic torsion Enrofloxacin 10–15 mg/kg Q 24 H; IV

Metronidazole 10 mg/kg Q 12 H; IV

Diagnostic Findings

7. Cytologic evidence of intracellular bacteria or plant/ COMBINATION 3

food material in abdominal fluid Cefotaxime 30–50 mg/kg Q 6 H; IV

8. Elevated creatinine and potassium levels compared to Clindamycin 8–11 mg/kg Q 8–12 H; IV

peripheral serum levels

18 Today’s Veterinary Practice September/October 2013

ACUTE ABDOMEN IN DOGS & CATS |

References

1. Franks JN, Howe LM. Evaluating and

TABLE 6. GI Protectants & Antiemetic Medications managing acute abdomen. Vet Med

2000; 95(1):56-69.

DOSE RANGE, FREQUENCY, & 2. Macintire DK. The acute

MEDICATION DRUG CLASS abdomen—differential diagnosis and

ROUTE management. Semin Vet Med Surg

Chlorpromazine Alpha-2 and D2 0.1–0.5 mg/kg Q 8 H; IM, SC, (Small Anim) 1988; 3(4):302-310.

3. Kirby R, Rudloff E. Acute abdomen.

antagonist suppository In Morgan R (ed): Handbook of

Dolasetron 5-HT3 0.5–1 mg/kg Q 12–24 H; SC, IV Small Animal Practice, 3rd ed.

Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

antagonist

4. Mann FA. Acute abdomen:

Famotidine H2 receptor 0.5–1 mg/kg Q 12–24 H; IV, PO, Evaluation and emergency

antagonist SC treatment. In Bonagura JD (ed):

Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy

Maropitant NK-1 antagonist 1 mg/kg Q 24 H; SC XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders,

2 mg/kg Q 24 H; PO 2002, pp 160-164.

5. Mathews K. Management of pain.

Metoclopramide D2 antagonist 0.2–1 mg/kg Q 6 H; IM, PO, SC Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract

1–2 mg/kg/day; CRI 2001; 30:4.

6. Crowe DT. Diagnostic abdominal

Omeprazole Proton pump 0.7–1 mg/kg Q 24 H; IV, PO paracentesis and lavage in the

inhibitor evaluation of abdominal injuries

in dogs and cats: Clinical and

Ondansetron 5-HT3 0.1–0.3 mg/kg Q 6–24 H; IV, PO experimental investigations. JAAHA

antagonist 1976; 168:700.

7. Rudloff E. Abdominocentesis

Pantoprazole Proton pump 0.7–1 mg/kg Q 24 H; IV and diagnostic peritoneal lavage.

inhibitor In Ettinger S, Feldman E (eds):

Textbook of Veterinary Internal

Prochlorpera- Alpha-2 and D2 0.1–0.5 mg/kg Q 8 H; IM, SC, Medicine: Diseases of the Dog

zine antagonist suppository and Cat, 6th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier

Saunders, 2005, pp 269-270.

Ranitidine H2 receptor Dog: 2 mg/kg Q 8–12 H; IV, PO

8. Rizzi TE, Cowell RL, Tyler RD,

antagonist Cat: 2.5 mg/kg Q 12 H; IV Meinkoth JH. Effusions; abdominal,

Cat: 3.5 mg/kg Q 12 H; PO thoracic, and pericardial fluid.

Diagnostic Cytology and Hematology

of the Dog and Cat, 3rd ed. St.

Louis: Mosby, 2008, pp 235-255.

STEP 9. For all patients, implement appropriate 9. Bonczynski JJ, Ludwig LL, Barton

LJ, et al. Comparison of peritoneal fluid and peripheral blood pH,

medical therapy. bicarbonate, glucose, and lactate concentration as a diagnostic tool

In addition to fluid therapy, electrolyte correction, for septic peritonitis in dogs and cats. Vet Surg 2003; 32:161.

and potential surgical correction, other therapies to 10. Crowe D, Devey J. Assessment and management of the

hemorrhaging patient. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1994;

consider include: 24:1095.

11. Herold L, Devey J, Kirby R, Rudloff E. Clinical evaluation and

management of hemoperitoneum in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care

Antibiotic Therapy 2008; 18(1):40-53.

Translocation of gram-positive and gram-negative aer- 12. Saxon W. The acute abdomen. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract

obes and anaerobes may occur following a period of 1994; 24(6):1207-1224.

poor perfusion and alteration to the integrity of the

GI tract. Common broad-spectrum antibiotic combi- Garret Pachtinger, VMD,

nations I use in critical patients are listed in Table 5. Diplomate ACVECC, is a

veterinarian at the Veterinary

GI Therapy Specialty and Emergency

For persistent GI upset, administer gastroprotectants Center in Levittown,

and antiemetics (Table 6). Pennsylvania, and COO of

VetGirl, LLC, a subscription-

IN SUMMARY based podcast service offer-

ing RACE-approved veterinary

Ultimately, the prognosis for patients with acute abdo-

CE. While in practice, he helped develop the emer-

men depends on the underlying disease process.12

gency room and intensive care unit at VSEC as well

Many diseases are treatable with fluid resuscitation,

as develop their emergency and critical care intern-

pain control, and exploratory laparotomy. Rapid ship program. Dr. Pachtinger is actively involved

evaluation and treatment of life-threatening complica- with the American College of Emergency and

tions, such as hypovolemic shock, decreases morbid- Critical Care and is a consultant for the Veterinary

ity and gives the astute clinician time to determine a Information Network. He has published numerous

diagnosis and develop a therapeutic plan. n scientific articles and book chapters and lectures

nationally and internationally. Dr. Pachtinger received

GDV = gastric dilatation–volvulus; GI = gastrointestinal; his degree from University of Pennsylvania.

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

September/October 2013 Today’s Veterinary Practice 19

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Three Basic Components of A Pulse: Shape, Jump, and LevelDokument3 SeitenThe Three Basic Components of A Pulse: Shape, Jump, and LevelShahul Hameed100% (1)

- Medical Intensive Care UnitDokument120 SeitenMedical Intensive Care Unithaaronminalang100% (6)

- 6th Charles Merieux Conference 2019 Pre Post Analytical Errors in HematologyDokument7 Seiten6th Charles Merieux Conference 2019 Pre Post Analytical Errors in HematologyYaser MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shark Cartilage MonographDokument4 SeitenShark Cartilage MonographWalter Sanhueza BravoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Removable Denture Pros Tho Don Tics 2007-08 - KaddahDokument145 SeitenPrinciples of Removable Denture Pros Tho Don Tics 2007-08 - KaddahJudy Abbott100% (1)

- CV Dr. Eko Arianto SpU 2021Dokument10 SeitenCV Dr. Eko Arianto SpU 2021Bedah ManadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Study On DigoxinDokument8 SeitenDrug Study On DigoxinDonald BidenNoch keine Bewertungen

- NEET-SS UrologyDokument59 SeitenNEET-SS Urologyadi100% (1)

- Jimma University: Institute of Health Faculty of Health Science School of PharmacyDokument69 SeitenJimma University: Institute of Health Faculty of Health Science School of PharmacyMaህNoch keine Bewertungen

- Https Cghs - Nic.in Reports View Hospital - JSPDokument36 SeitenHttps Cghs - Nic.in Reports View Hospital - JSPRTI ActivistNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Amenorrhea Therapy With Accupu 2c484cf6Dokument5 SeitenSecondary Amenorrhea Therapy With Accupu 2c484cf6NurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nonoperative Management of Femoroacetabular ImpingementDokument8 SeitenNonoperative Management of Femoroacetabular ImpingementRodrigo SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Delivery Receipt: Product Delivery Location: FacilityDokument1 SeitePatient Delivery Receipt: Product Delivery Location: FacilityPat Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Krok 2 2002-2003 SurgeryDokument23 SeitenKrok 2 2002-2003 SurgeryAli ZeeshanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parkinson S Disease Epidemiology,.9Dokument5 SeitenParkinson S Disease Epidemiology,.9bacharelado2010Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hon 2005Dokument5 SeitenHon 2005lenirizkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laporan Persediaan 1sd30okt2023Dokument28 SeitenLaporan Persediaan 1sd30okt2023ARIEF YUNIARDINoch keine Bewertungen

- WHO Vaccine Manual PDFDokument112 SeitenWHO Vaccine Manual PDFRagel CorpsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 270 Scientists Call On Spotify To Take Action Over - Dangerous - Misinformation On Joe Rogan Podcast - IFLScienceDokument4 Seiten270 Scientists Call On Spotify To Take Action Over - Dangerous - Misinformation On Joe Rogan Podcast - IFLScienceDigiti inNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health and Hindu Psicology by Swami AkhilanandaDokument245 SeitenMental Health and Hindu Psicology by Swami Akhilanandaapi-19985927100% (3)

- Perioperative Nursing: Lecturer: Mr. Renato D. Lacanilao, RN, MANDokument27 SeitenPerioperative Nursing: Lecturer: Mr. Renato D. Lacanilao, RN, MANJmarie Brillantes PopiocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Essential Steps of CPRDokument2 Seiten7 Essential Steps of CPRBea YmsnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Checklist of Quality Indicators For NABH Accreditation PreparationDokument11 SeitenChecklist of Quality Indicators For NABH Accreditation PreparationQUALITY SIDARTH HOSPITALSNoch keine Bewertungen

- APA - DSM5 - Level 2 Inattention Parent of Child Age 6 To 17 PDFDokument3 SeitenAPA - DSM5 - Level 2 Inattention Parent of Child Age 6 To 17 PDFLiana Storm0% (1)

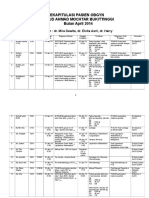

- Rekapitulasi Pasien Obgyn Apr 2014 2Dokument20 SeitenRekapitulasi Pasien Obgyn Apr 2014 2Ressy Dara AmeliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health and Family Welfare (C) Department: PreambleDokument14 SeitenHealth and Family Welfare (C) Department: PreambleAjish BenjaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Causes, Severity and Outcome of Neonatal Thrombocytopenia in Hi-Tech Medical College and Hospital, BhubaneswarDokument4 SeitenCauses, Severity and Outcome of Neonatal Thrombocytopenia in Hi-Tech Medical College and Hospital, BhubaneswarInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- PCNE Classification Scheme For Drug Related Problems-1 (Revised)Dokument3 SeitenPCNE Classification Scheme For Drug Related Problems-1 (Revised)Alan HobbitNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Ophthalmologists Cullman, AL: We Found NearDokument2 Seiten4 Ophthalmologists Cullman, AL: We Found NearSantosh Sharma VaranasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology Investigatory Project: The Study of Effects of Antibiotics On Micro-OrganismsDokument9 SeitenBiology Investigatory Project: The Study of Effects of Antibiotics On Micro-OrganismsSamanwitha SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen