Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Moving Toward Reconciliation

Hochgeladen von

Cham SaponCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Moving Toward Reconciliation

Hochgeladen von

Cham SaponCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Moving Toward Reconciliation:

Community Engagement in Nursing Education

Majorie A. Schaffer and Carol Hargate

Abstract

The integration of community engagement learning experiences in nursing education promotes a

commitment to social responsibility and service. A nursing department implemented learning experiences

for undergraduate nursing students across five semesters in churches, schools, and community agencies.

Focus group data and selected stories from undergraduate and graduate nursing students, nursing faculty,

and community partners provided lessons for establishing effective academic-community partnerships.

Lessons learned included: 1) time and academic expectations are constraints, 2) being in the community

requires flexibility, 3) working side by side develops relationships, 4) the community teaches faculty

and students, and 5) the learning curve needs to be recognized. The lessons learned provide guidelines

for nursing faculty and community partners in creating and sustaining partnerships that contribute to

educating nurses for practice in a diverse society.

Introduction in values and lifestyle approaches between

A key recommendation for transforming community members, community organizations,

nursing education for the future calls for nursing students, and nursing faculty that lead

preparing nurses to work with diverse populations to discomfort, tension, or frustration. Learning

in community settings. Educational essentials experiences in community settings provide nursing

emphasize learning to advocate for social justice, students opportunities to adapt to and reconcile

including a commitment to improving the health differences and live with ambiguity while working

of vulnerable populations and eliminating health toward common goals. Experiential learning

disparities. (AACN, 2005; 2008; Groh, Stallwood, increases capacity to become more effective in

& Daniels, 2011; Institute of Medicine, 2011). providing nursing care to diverse populations and

Inequities that contribute to health disparities communities, ultimately contributing to reduced

include socioeconomic status, educational health disparities and improved population health.

opportunities, neighborhoods, stress, and access

to quality health care (Robert Wood Johnson Purpose

Foundation, 2011). These inequities contribute to an This paper presents the stories of students,

unfair burden of disease (Cockerham, 2007; Health community partners, and faculty about the benefits

Policy Briefs, 2011, http://www.healthaffairs.org/ and challenges encountered through community

healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=53). engagement learning. In addition, the lessons

Community Campus Partnerships for Health learned for forming effective academic-community

(CCPH) promotes the development of partnerships partnerships are examined through the stories of

between academic institutions and communities partnership participants.

to work toward solving major health, social, and

economic challenges (CCPH, 2012). For nursing Context

students, the goal is to facilitate their commitment Reconciliation

to social responsibility and service, their desire to Reconciliation is a central aspect of nursing

improve health care access to those that need it, and education, particularly related to preparing nurses

their ability to form partnerships with communities to address health inequities and engage diverse

to improve the health of populations. communities in dialogue about potential solutions.

Nursing education integrates classroom Reconciliation with individuals, groups, or

learning with clinical experiences in health care communities involves setting aside an attitude or

settings. In community settings, nursing students action in order to bring about positive change and

have an opportunity to hear the stories about the restore relationships (Boesack & DeYoung, 2012).

life experiences of individuals and families and how Curricular strategies that promote relationship

these life experiences are connected with health building between students and community

and access to health care. There may be differences members foster both knowledge and skill building

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 59

to work in partnership with diverse populations authentic partnerships. Three essential components

in an ethical and sensitive manner. In nursing, for an authentic community partnership include:

a focus on reconciliation is also consistent with 1) the partnership must be relationship-focused,

the central nursing concept of caring. DeYoung open, honest, respectful, and committed to mutual

(2007) stated relationship building is the hard learning and sharing the credit for accomplishments;

work of reconciliation that offers something that 2) outcomes must be meaningful to the community;

cannot be found in social or economic justice and 3) transformation should occur at multiple

alone. Implementing community engagement into levels, including personal (through self-reflection)

the nursing curriculum serves to unite nursing and institutional levels, community capacity

educators, students, and community members in building, generation of new knowledge, and social

moving toward reconciliation and improved health justice (CCPH, 2012).

outcomes. Research on community engagement reveals

that students with positive community engagement

Social Justice experiences have a heightened sense of civic

Social justice focuses on the balance of societal responsibility, challenge stereotypes, become

burdens and benefits and holds that members of more culturally aware, and appreciate similarities

society have rights and responsibilities to promote and differences across cultures (Hunt & Swiggum,

equity in the distribution of burdens and benefits 2007; Mueller & Norton, 2005). Community

(Boutain, 2008). A focus on social justice will prepare engagement experiences also develop students’

students to be social change agents and develop the leadership, critical thinking, professional decision

skills for implementing actions that improve the making, social skills, and social awareness. For

health of vulnerable populations (Boutain, 2005; students, learning outcomes are enhanced through

Fahrenwald, 2003). One strategy for creating learning a pedagogy that includes: 1) active learning,

opportunities in social justice is the use of innovative 2) frequent non-threatening feedback from all

community settings where students encounter social collaborators, c) collaboration, d) a mentor to

injustices. Kirkham, Hofwegen, and Harwood facilitate transfer of theory to practice and navigate

(2005) analyzed nursing students’ responses to complex situations that may develop, and 5)

encounters with poverty and inequities in clinical practical applications that are in the real world but

experiences in innovative community settings, have a safety net for mistakes (Bringle & Steinberg,

including corrections, international, parish, rural, 2010). Schussler, Wilder, and Byrd (2012) explored

and aboriginal settings in Canada. Focus groups with nursing student development of cultural humility

65 undergraduate students, clinical instructors, and in student reflective journaling through four

nurse mentors yielded narratives of social justice. semesters in a community clinical experience.

Through development of a greater awareness of The researchers identified two concepts in the

poverty, inequities, and marginalization, students reflective journals that contributed to development

developed a commitment to social change. of cultural humility. Students linked poverty to

health disparities when they discovered how a lack

Community Engagement of resources contributes to power imbalances. In

Community engagement is the “application of addition, students learned they needed to integrate

institutional resources to address and solve challenges cultural factors when planning health promotion

facing communities through collaboration with teaching.

these communities” (CCPH, 2012). The Robert

Wood Johnson Foundation (2012) identified Development of the Community Engagement

community engagement as one of the multifaceted Curriculum

and targeted solutions featured in disparities projects. Bethel University is a small private liberal arts

Community engagement provides “the seeds we college in a suburban location with proximity to

need to plant for change.” The Carnegie Foundation a major metropolitan area. The nursing program

(2012) developed a community engagement elective implemented a revised nursing curriculum in 2010

classification system to recognize the community that featured community engagement curricular ac-

engagement initiatives of institutions of higher tivities. Faculty aimed to prepare nurses who will:

learning. The Foundation identified reciprocal 1) contribute to reducing health disparities, 2) de-

partnerships as a key criterion for the community velop cultural sensitivity and competence, and 3)

engagement classification. develop commitment to serving diverse and vulner-

CCPH promotes the development of able populations. These goals are consistent with

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 60

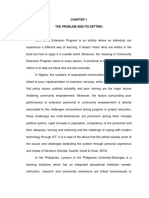

the Bethel University val- Figure 1. Barriers and Solutions and Response to Health Disparities

ues of reconciliation and

peacemaking. Health Factors & Social Determinants of Health

To prepare for the

community engagement

Social & Economic

learning experiences, nurs- Health Behaviors

Factors

Physical Environment

ing faculty and graduate

students conducted fo- Barriers Solutions Barriers Solutions Barriers Solutions

available

stress “free” lack of education cultural

cus groups with potential extracur- education/ disconnect community

costly ricular income family con- resources

community partners to fruits & nections unfamiliar

vegetables learning community open

explore community views to manage status political forums for

lack of stress environ- lack of community

on how nursing students excercise “families ment communi-

health identify

could be involved in their traditional education

broken up”

“having a

cation

stressors

choice” in commu-

organizations. Analysis of medicine

increased

lack of

power & nity

data from 11 focus groups lack of

access to

focus on

preventa-

control “realizing

that differ-

with churches, schools, health care tive health social

isolation

ence does

not mean

non-profit agencies, and a people

taking language

bad”

long-term care facility re- charge of

their own

barriers

vealed relevant curricular health

themes of what was needed

to support the community

engagement curriculum. Through intergroup dialogue, the community

The resulting themes included adequate orienta- participants identified “walls” (barriers) and “doors”

tion for students, clear expectations, working out (solutions) associated with the community’s

scheduling and logistics, matching student interest self-identified health inequities. The identified

with the organization, addressing the challenges of barriers and solutions for challenges encountered

interaction with populations in the community, were then categorized as health and behavior,

and brainstorming about project ideas (Wattman, social and economic, and physical factors in their

Schaffer, Juarez, Rogstad, Bredow, & Traylor, 2009). environment (see Figure 1).

The nursing department sponsored a series of rec- Community engagement learning experiences

onciliation lunches during one semester that were were implemented in the Spring Semester of 2011

led by a trained facilitator for all nursing faculty. in 21 community engagement sites, with a faculty

The following semester, faculty and community liaison assigned to each site and the appointment

partners participated in “Lunch and Learn Sessions” of a community engagement coordinator in the

that featured discussion about selections from the Nursing Department. Initially 2–5 sophomore

Unnatural Causes DVD series on health disparities students were assigned to each site. With full

(http://www.unnaturalcauses.org/). A quasi-inter- implementation of the curriculum, students at

group dialogue format was used to elicit commu- each site range from 6–15. (See Table 1 for a

nity participants’ reflections on community health more complete description of the community

concerns and challenges and potential solutions. engagement curriculum.) Additional features of the

Democratic intergroup dialogue is one strategy that community engagement program include Student

can help groups move toward reconciliation; this Community Engagement Council meetings (twice

approach recognizes and respects all parties, creates a semester) and Community Partner meetings (once

a setting that reinforces the notion that change is a semester). Student Community Engagement

possible, and transforms relationships toward pos- Council members represent all students and

itive social change. From such changes, public de- contribute to the planning process for community

cision making is influenced, and new, previously engagement curricular implementation.

unknown results can be produced (Schoem, 2003;

Zubizaretta, 2002). Characteristics of intergroup Method

dialogue include fostering an environment that en- Methods included focus groups with

ables participants to speak and listen in the present sophomore nursing students (a program evaluation

while understanding the contributions of the past component), and recorded or written stories

and the unfolding of the future (Dessel, Rogge, & from Student Community Engagement Council

Garlington, 2006). members, graduate students, nursing faculty, and

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 61

community partners. A graduate nursing student experiencing ambiguity, and 6) creating effective

conducted two focus groups with sophomore community engagement partnerships.

nursing students in a University classroom Experiencing difference. Students noted there

following their first semester in their community were differences in the communities, environment,

engagement setting to evaluate student learning and life experiences in comparison to their own life

experiences in the sophomore year. No faculty experiences. A student reflected on wondering how

members were present during the focus groups. youth in an African American church viewed white

Faculty instrumental in initiating community students:

engagement experiences generated the focus

group questions based on suggestions from the I was a little nervous going into my

Community Engagement Through Service Learning site actually because it’s an all-African-

Manual (Case Western Reserve University, 2001) American church and I could just tell

and goals for student learning experiences. people were looking at me like what are

Focus group questions addressed positive and you doing here so I can be a little negative

frustrating experiences; learning about self, nursing, and say that but I was just a little nervous

at first because what do they think of us

community agency, and community; needs of

coming to their youth group, us four white

the community; and contributions made to the

students coming from [the University].

community. One student was randomly selected

They probably have a lot of assumptions

from each community engagement site from a

in their head going on just like we do--its

total of 90 students assigned across 21 community

natural for people when they first come

engagement sites. The study was approved by the into an environment. It’s been good to

Bethel University Institutional Review Board and just be able to throw those stereotypes

all participants signed a consent form. Two focus aside and just realize we all serve the same

groups were audio-taped and transcribed. A content God and he loves us all equally.

analysis strategy was used to identify focus group

themes. The graduate student who conducted the Framing learning experiences. Students

focus groups organized content themes, which were reflected on how they understood the purpose

reviewed, revised, and validated by the first author. and outcomes of CE, including learning public

Additionally, others involved in community health approaches, learning to love people in the

engagement (a convenience sample) were asked community, and being able to integrate their faith.

to provide stories about their experiences. They One student specifically discussed reconciliation:

were contacted by phone, in-person, or email and

invited to participate in sharing their experiences I think a big focus of [the University] is

with community engagement. Written consent reconciliation and I feel like community

was obtained for using their stories. Student engagement helps us to reconcile ourselves

Community Engagement Council members, with the community and find ways of

graduate students who had an internship experience dealing with different social disparities but

with the community engagement undergraduate to also learn from them and become better

program, nursing faculty who were liaisons to people ourselves from the experience and

community engagement sites, and community also to help the community as well.

partners provided stories in a written or oral

format (audio taped). The stories represent the Learning from the community. As students

experiences of nursing students, nursing faculty, spent time in their community settings, they began

and community partners following one to two to realize the potential of their learning from the

semesters of community engagement experiences. people they were serving. A student reflected on the

first realization of the purpose of the experience:

Results

Two focus groups were conducted; one group … it’s like this is a group of people, it is

had eight students and the second included nine like a family or church buddy, it is like just

students. A content analysis of student comments knowing them, there is so much for me to

revealed six themes: 1) experiencing difference, learn, and I don’t know how much we are

2) framing learning experiences, 3) learning from there to help them as much as just to know

the community, 4) acquiring professional skills, 5) them. Right now we did a blood pressure

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 62

screening but it’s not like they needed us Creating effective community engagement

to do that. It’s like learning from them-- partnerships. In focus groups, students contributed

being who they are is a lot to offer us. So suggestions about the faculty liaison role, orientation

I think right now it’s just for me to know format, and matching the community engagement

them, their lives, their communities, and sites to coordinate with student schedules. They

their families. discussed the variability in interactions with the

faculty liaison. A student expressed appreciation

Acquiring professional skills. A number of for the faculty liaison:

student comments addressed how skills practiced in

community engagement would contribute to their My faculty member in charge of our site

competence in nursing, specifically focusing on really took an extra step to get to know

communication, teamwork, and problem solving. our group members because after the first

A student reflected about the skill of problem time we went to the site, she took us out

solving: to lunch; we just sat down and got to know

her a little better. It was really awesome

I think another really vital one [skill] that because it wasn’t like an initiative to do

we learned is problem solving. …. You better but really made me see her goals for

just have to learn how to improvise and us and even as a person getting to know

go with it and figure out what you are her better makes me want to help out more

doing, different situations that you may because I feel like she will back us up.

come across at the sites you may have to

problem solve. It’s really critical as a nurse In contrast, another student expressed that

to be able to have that skill. students should have greater responsibility:

Several students commented about the teamwork We don’t even have a liaison and its better

experience in their community engagement setting because there is no one to communicate

and the realization that different viewpoints exist through and it’s gone really smoothly.

within the nursing profession. For example: “I I feel like it’s been really helpful to have

think it’s like a lesson that we would learn for the it that way, more responsibility on the

rest of our lives…” “We need to get outside of students rather than faculty.

our little bubble and realize that there are going

be a lot of nurses that don’t have the same vision Other students commented about wanting

of nursing.” …. “I need to realize that maybe not more consistency between the faculty liaisons. A

everyone thinks like me or wants to become a nurse student expressed that many of their questions were

for the same reason as me but ultimately we are all left unanswered (ambiguity). What they wanted

on the same team of providing the best care we can from the faculty liaison was to “get the ball rolling

for the patient.” right away” and help them to feel more comfortable

by making the initial contact with the community

Experiencing ambiguity. Many students partner.

commented about the challenges of working

in a community setting in which the roles and Stories from Students on the Community

tasks of nursing students are less clearly defined. Engagement Council

They reported experiencing ambiguity in role A student shared an experience in learning

expectations, the community partner’s lack of about a residence that served women recovering

knowledge about community engagement, unclear from addiction and abuse:

communication channels, and difficulty scheduling

their community engagement experience. Students Another neat aspect that we saw was a

discussed the ambiguity of working with the faculty huge kitchen where women can learn to

liaison and community partner to determine their cook healthy meals for themselves and

purpose and activities in the community setting. their families. Most of the women grew

They expressed that expectations were not clear up in homes where abuse was so prevalent

and in some cases neither the faculty liaison nor there was no teaching, so for them to

community partner was able to provide them with learn these skills is crucial to their success.

clear guidance. The thing I loved most is that they don’t

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 63

just teach people how to simply get over are stronger together than we are apart. I

their addiction; they teach them how to walked away feeling really hopeful where I

heal from the inside out, which is what had been feeling not so hopeful and a little

ultimately brings healing. I look forward desperate in that situation.

to another three semesters there and can’t

wait to go visit again! A student whose group had been unable to

establish a connection with their assigned church

Another student talked about the difficulty expressed feeling encouraged by hearing about

of meeting with the faculty liaison, encountering activities and interactions at the lunch. The student

uncertainty about how students should interact commented,

with the organization, the challenge of finding

time with the academic schedule, and the hope Seeing people at the luncheon and that

for continued opportunity for involvement in the they are so excited to have people come

organization. into their church was really hopeful and we

Student Community Engagement Council were able to see by all the students coming

members also shared reflections of a lunch with into the community, the big effect it has

health coordinators and staff from an organization, on the community, and what we can learn

which is a collaboration of African American from the community as well.

churches to build community and promote healthy

living and values. Masters and undergraduate The lunch event served a similar purpose for

nursing students developed resource notebooks in another student whose group who had not been

response to a request from the health coordinators able to connect with the church health coordinator.

for a health education tool. An undergraduate The student reflected,

student noted the challenge of integrating different

groups at a partnership luncheon: It was nice to hear all the other coordinators

and hear them say “We’re so excited to

It was cool to see the people who were have students working with us.” … All

there…. We were talking afterward how it of them seem really passionate about

was very segregated. [The University] was what they were doing. They were very

all in one area and everyone else from the concerned about their communities. That

community was in their own …it was just was refreshing…. Going to that luncheon

the nature of the thing, but it was kind of was really cool. Even though we are not

sad because we’re doing this to get more at that site anymore I have a good idea of

cultured and we all just kind of segregated what the other groups are experiencing.

together.

Stories from Graduate Students

The same student also reflected about Graduate students assisted with community

community strengths. She commented, “for me engagement activities in a variety of ways.

personally, I learned how there are a lot of people They provided classroom content, assisted with

who really do care about the community.” coordination of activities, and contributed

Another student reflected on the meaning of to evaluation of the community engagement

hope for communities that experienced health curriculum. Graduate students reflected on

disparities: connecting with the community and the benefits of

working in partnerships. A graduate student wrote,

It was the pastor I believe really put a sense

of hope back in me. Because unfortunately Our teaching opportunity for the students

we’re talking about health disparities and came with having them present and explain

we are seeing the economy and we’re seeing the resource binder [Reaching for Healthier

firsthand what’s happening so those who Tomorrow] and its uses to their individual

are even less fortunate are even becoming community site leader. For me and my

more, less fortunate. He just talked about [teaching] partner, it was breaking the ice

hope. We are doing something and even by engaging the leaders in a health quiz and

though it’s something small, hopefully giving a live cooking demonstration using

that trickle effect will be larger and we one of the healthy recipes from the created

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 64

resource binder. For the leaders, it was experience. It takes courage to go into

having the opportunity to get to know us another culture and introduce oneself,

and have materials that they could use for offering involvement with health initiatives

their community. This learning experience already started, and a willingness to do

reinforced, to me, that opportunities for whatever one can yet feeling inadequate

learning, growth, and partnership can take for the task at hand.

many forms.

The faculty member noted that leadership

Another graduate student reflected on learning experiences were “rocky” because of

opportunities for “exponential growth and busy schedules that became a barrier to following

opportunity for strengthening interpersonal and through on communication. However, there

leadership skills during times of project success and were also opportunities for growth in leadership,

failure.” Graduate students balanced the uncertainty indicated in the following comment:

of the community settings, coached undergraduate

students to gain learning from both successes and The student leadership that emerged

challenges, and focused on their own leadership through the experience has been quite

growth. remarkable and also a learning experience.

The graduate student who conducted focus One young man displayed a passion for

groups with sophomore students following their this experience and by default took over

first semester, made the following observations: leadership of the group. He emailed

meeting times and topics and led the

Many students went into this course “in-person” meeting of the group, with a

with the assumption that they will be written agenda. He also connected with

teaching the community and making the site on several occasions, connecting

an impact on the lives of community emotionally as well, emailing over the

members. At the end of the first semester summer to ask if they were okay after

since the implementation of (community tornadoes [hit the area].

engaement), it was quite astonishing to

most students the amount of learning Another faculty member described a learning

and growth that has taken place regarding experience in the community engagement setting

various cultural values and beliefs… . that promoted student learning about the diversity

Community engagement also allows of the facility. Nursing students tabulated all the

nursing students the majority of whom different languages spoken in a long-term care

are white to come in contact with people facility. The faculty member worked with students

that they have little or no interaction to create a “wordle” (www.wordle.net/) document

with in the past. Through meaningful of languages, which resulted in a colored illustration

partnerships, nursing students are able of “word clouds from text.” The faculty member

to throw stereotypes aside and treat explained that the resulting illustration “emphasized

community members with as much respect the diversity of the facility. The administrators at

as they deserve. the facility were happy to have some meaningful

art to hang in the halls of the facility. The students

Stories from Faculty Members became acquainted with the facility and the facility

Faculty members also experienced challenges benefited from the product of the class exercise.”

with scheduling community engagement

experiences. One of the faculty liaisons adapted to Stories from Community Partners

this challenge by finding an alternative community A health coordinator from one of the churches

engagement site that was familiar to them. Another expressed satisfaction with student participation in

faculty member discussed the learning that results a church flu shot clinic. She said, “The three nursing

from uncertainty: students volunteered to take blood pressures. More

people, young and old, came down to get their

Learning to be flexible and willing to blood pressure checked and also got a flu shot.”

feel “uncertain of what to do” or “out The community partner that worked directly

of their element” are the peripheral, yet with all health coordinators at the churches spoke

equally important learning aspects of this about both student involvement and satisfaction

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 65

with the resource notebook that focused on healthy Discussion

living: Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this project is the inclusion of

Some of the successes are the great prepa- stories from all partnership participant categories,

ration and community interaction prior which gives a more complete picture of community

to the students actually entering the com- engagement learning experiences. Since sophomore

munity of faith. The coordinators, pastor, students were randomized into focus groups, their

and congregation at the churches were wel- stories are likely to be more representative of student

coming and made the students feel a part views. However, Student Community Engagement

[of the church congregation] although Council members, nursing faculty, and community

they may have been somewhat apprehen- partner participants were recruited based on their

sive at first especially if, for the first time availability, which means the stories likely do not

they were the minority. The students have capture the full range of views about community

attended the worship services and stayed engagement experiences.

for the entire service (more than an hour)

and have connected to the other young Lessons Learned

adults in the congregation and the young- Lessons learned stem from the voices of

er children admire them. They continue to students, community partners, and faculty about

communicate with the coordinator after their community engagement experience and

the semester ends in preparation for the the authors’ experiences with overseeing the

next semester. The resource book that was implementation of the community engagement

created and provided for the churches is curriculum.

brilliant and a priceless tool in the hands

of those overseeing the health ministry Time and academic expectations are con-

in their churches. I personally found the straints. All stakeholders seem to value the goals

Low-Calorie Meals gift book for partic- of community engagement—reducing health dis-

ipating in the health quiz a must in my parities, developing cultural sensitivity and compe-

kitchen and can use it as a teaching tool for tence, and developing a commitment to vulnerable

nutrition classes. populations. However, the reality of finding time to

devote to these goals in the midst of a content-driv-

The director of the program also spoke about en curriculum and the busy schedules of students,

the challenges encountered in working with differ- community partners, and faculty is a major chal-

ent calendars and volunteers as well as managing lenge. “All the academic stuff,” as one student said,

changes that occur in funding and resources: eclipses the time needed to invest in community

engagement. It is important for all stakeholders to

One of the challenges with the churches is keep the goals of community engagement in the

fitting the health ministry into the church forefront. Faculty and students are learning to “let

calendar. The churches with an established go” or adapt expected assignments and tasks, giv-

and strong health ministry can quickly in- en the uncertainty and changing community envi-

tegrate nursing students into health minis- ronment. The key lesson learned is that change is a

try while in the other churches it is a great- process and a good portion of the learning happens

er challenge and may leave the students a during the process, sometimes more than the learn-

little frustrated. However, we are expecting ing that results from the end product or outcome.

some changes especially since the positive Being in the community requires flexibility.

reports have promoted others to request Although nursing faculty endorse and even em-

nursing students for their church. In many brace the idea of reconciliation, the hard long-term

churches those working in the health min- community relationship building that is founda-

istry are volunteers making it extremely tional to reconciliation (DeYoung, 2007) is a major

difficult for consistent follow through…I challenge in several ways to nursing faculty. Barriers

believe this is an exceptional concept to to the development of long-term relationships be-

incorporate/integrate community engage- tween nursing faculty and the community include:

ment in underserved communities for the changes in faculty course assignments, changes in

nursing students’ education and commend community agency staff, and time constraints fac-

you for the commitment to see it through. ulty experience in juggling multiple roles. Time

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 66

management and complex schedule challenges in developed the motivation to do things differently

community engagement are consistent with barri- in future experiences in the community.

ers to effective academic-community partnerships The learning curve needs to be recognized.

identified in the literature (Rosing, Reed, Ferrari, The stories represent community engagement ex-

& Bothne, 2010; Simpson 2012). In addition, the periences midstream in curricular implementation.

norm for nursing faculty is to develop the course Since change is a constant given the differences in

plan prior to each semester, and then follow the roles and settings, community engaement partner-

syllabus until the course is finished. From an aca- ships and learning strategies are dynamic and will

demic perspective, nursing faculty and nursing stu- change through the implementation process. This

dents have learned to cope and “survive” by living experience is consistent with how our real world

by their “to do lists.” This organized approach is works. Thus we need to recognize that we will learn

consistent with an academic and hospital environ- also from times when the experience does not go as

ments, but can create tension in collaboration in expected. As we work to develop meaningful rela-

community settings. In community settings, the tionships, we need to recognize that it takes time,

“to do list” may change several times within a se- we all bring different skills and expertise that are im-

mester timeframe. portant to the collaboration process, and we need

Working side by side develops relationships. to forgive one another when our understanding or

If community partners, nursing students, and nurs- capacity is limited. We have hope in the capacity to

ing faculty can move beyond the constraints of time learn ways of moving toward reconciliation.

and the norms of their different settings, they have

the opportunity to experience joy and satisfaction Conclusion: Moving Toward Reconciliation

as they work together. The work of reconciliation Reconciliation is an ongoing and continuing

means the authentic or “real” person shows up and process and is certainly characterized by “bumps

shares knowledge, skills, and ideas to work toward in the road,” collisions of tensions, and stops and

a common goal. Creating time to share food and starts. Community partners welcomed nursing

open conversation is crucial to relationship build- faculty and students into their organizations,

ing—working side by side as CE experiences are creating strong partnerships and the development

implemented. In a qualitative study about cultural of a broad array of strategies and resources that

safety in nursing and nursing education (Doutrich, contribute to healthier communities. Nursing

Arcus, Dekker, Spark, & Pollock-Robinson, 2012), faculty and students along with the community

the researchers identified one of the major themes partners joined together, were courageous in

as “learning to walk alongside.” This involves a starting the journey, and desired to contribute to

partnership model in which all voices are important the development of future nurses.

and included in decision-making.

The community teaches students and faculty. References

Although both students and faculty expressed American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

frustration with the uncertainty of their community (2008). The essentials of baccalaureate education

connections and for some the connections did not for professional nursing practice. Retrieved

happen, the uncertainty also can lead to increased from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education/pdf/

problem solving by students. Nursing faculty baccessentials08.pdf

members that take on the role of a “coach” (in American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

contrast to the traditional faculty role of “director”) (2005). Nursing education’s agenda for the 21st

are more likely to emphasize the learning that century. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.

comes from being in the community. Both students edu/Publications/positions/nrsgedag.htm

and faculty may need to continue moving out of Boesack, A.A. & DeYoung, CP. Radical

their “comfort zone” in wanting detailed plans for reconciliation: Beyond political pietism and Christian

completing specific activities and tasks. quietism. Maryknoll, NY: Orbus Books.

One example showcased in the student stories Boutain, D.M. (2005). Social justice as a

illustrated the phenomenon of segregation. In this framework for professional nursing. Journal of

situation, the student learned about the meaning Nursing Education, 44(9), 404–408.

of segregation through sitting in different groups Boutain, D.M. (2008). Social justice as a

at an event in the community. The same learning framework for undergraduate community health

would be much less likely to occur in the classroom clinical experiences in the United States. International

setting. From this learning experience, the student Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 5(1). Retrieved

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 67

from: http://www.bepress.com.ijnes/Vol5/iss1/art35 http://www.bepress.com/ijnes.

Bringle, R. G. & Steinberg, K. (2010). Educating Mueller,C., & Norton, B. (2005). Service

for informed community involvement. American learning: Developing values and social responsibility.

Journal of Community Psychology, 46, 428–441. In Billings, D.M., & Halstead, J.A. (Ed.), Teaching in

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement nursing: A guide for faculty (2nd ed., pp. 213–227). St.

of Teaching. (2012). Classification description: Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

Community engagement elective classification. Robert Wood Johnson, Foundation. (2012).

Retrieved from: http://classifications. Finding answers solving disparities. Retrieved from

carnegiefoundation.org/descriptions/community_ http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/12/

engagement.php finding-answers-solving-disparities.html.

Case Western Reserve University. (2001). Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2011).

Community engagement through service learning What shapes health? Issue Brief #2: Exploring

manual. Retrieved from http://depts.washington. the social determinants of health. Robert Wood

edu/ccph/pdf_files/CETSLmanual4.pdf Johnson Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.

Cockerham, W.C. (2007). Social causes of health rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/03/what-shapes-

and disease. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. health-related-behaviors---.html<http://www.rwjf.

Community Campus Partnerships of Health org/content/rwjf/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-

(2012). Community Campus Partnerships of Health: research/2011/06/what-shapes-health.html>.

Transforming communities and higher education. Rosing, H., Reed, S., Ferrari, J.R., & Bothne,

Retrieved from http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/ N.J. (2010). Understanding student complaints in

scholarship.html the service learning pedagogy. American Journal of

Dessel, A., Rogge, M., & Garlington, S. (2006). Community Psychology, 46(3-4), 472–481.

Using intergroup dialogue to promote social justice Schoem. D. (2003). Intergroup dialogue for a

and change. Social Work, 51, 303–315. just and diverse democracy. Sociological Inquiry, 73(2),

DeYoung, C. (2007). Living faith: How faith 212–227.

inspires social justice. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Schuessler, J.B., Wilder, B., & Byrd, L.W. (2012).

Press. Reflective journaling and development of cultural

Doutrich, D., Arcus, Kerri, Dekker, L., Spuck, humility in students. Nursing Education Perspectives,

J., & Pollock-Robinson, C. (2012). Cultural safety 33(2), 96–99.

in New Zealand and the United States. Journal Simpson, V.L. (2012). Making it meaningful:

of Transcultural Nursing, 23(2), 143–150. DOI: Teaching public health nursing through academic-

10.1177/1043659611433873 community partnerships in a baccalaureate

Fahrenwald, N.L. (2003). Teaching social justice. curriculum. Nursing Education Perspectives, 33(4),

Nurse Educator, 28(5), 222–226. 260–263).

Groh, C.J., Stallwood, L.G., & Daniels, J.M. Wattman, J.E., Schaffer, M.A., Juarez, M.J.,

(2011). Service-learning in nursing education: Its Rogstad, L.L., Bredow, T., & Traylor, S.E. (2009).

impact on leadership and social justice. Nursing Community partner perceptions about community

Education Perspectives, 23(6), 400–405. engagement experiences for nursing students. Journal

Health Policy Briefs (October 6, 2011). of Community Engagement Experiences for Nursing

Achieving equity in health. Retrieved from: http:// Students, 1(1). http://discovery.indstate.edu/ojs/

www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief. index.php/joce/issue/current.

php?brief_id=53. Zubizaretta. R. (2002). Dynamic facilitation: An

Hunt, R.J., & Swiggum, P. (2007). Being in exploration of deliberative democracy, organizational

another world: Transcultural student experiences development and educational theory as tools for social

using service learning with families who are change. Unpublished master’s thesis. Sonoma State

homeless. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 18(2), 167– University. Retrieved June 4, 2004, from WTA’Av.

174. doi:10.1177/1043659606298614 sonoma.edu/iisers/s/.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of

nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, About the Authors

D.C.: The National Academies Press. Marjorie A. Schaffer is a professor of nursing and

Kirkham, S.R., Hofwegen, L.V., Harwood, Carol Hargate is an associate professor of nursing,

C.H. (2005). Narratives of social justice: Learning both at Bethel University in McKenzie, Tennessee.

in innovative clinical settings. International Journal of

Nursing Education Scholarship, 2(1). Retrieved from:

Vol. 8, No. 1—JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND SCHOLARSHIP—Page 68

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Community Schools White Paper - Jan - 2016Dokument21 SeitenCommunity Schools White Paper - Jan - 2016Rhon T. BergadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- History and Evolution of Psychiatric NursingDokument4 SeitenHistory and Evolution of Psychiatric Nursingkaren carpio100% (1)

- Criminal Charges For Medical Mistakes A Tough Pill To SwallowDokument6 SeitenCriminal Charges For Medical Mistakes A Tough Pill To SwallowCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- 112 564 1 PBDokument16 Seiten112 564 1 PBSuphachittra ThongchaveeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing Global CitizenDokument18 SeitenDeveloping Global CitizenMuhamad RamzyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Based HealthDokument11 SeitenCommunity Based HealthAmira Fatmah QuilapioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of Community ParticipationDokument8 SeitenImportance of Community ParticipationLikassa LemessaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diversity 1Dokument22 SeitenDiversity 1Ratëd MwNoch keine Bewertungen

- First-Draft Impact.222Dokument28 SeitenFirst-Draft Impact.222Sam Abduhassan SaidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Models For Faculty Development: What Does It Take To Be A Community-Engaged Scholar?Dokument19 SeitenModels For Faculty Development: What Does It Take To Be A Community-Engaged Scholar?B LabNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Draft Impact.222Dokument27 SeitenFirst Draft Impact.222Sam Abduhassan SaidNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Qualitative Case Study of Best Practices in Holistic EducationVon EverandA Qualitative Case Study of Best Practices in Holistic EducationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Kompetensi Perawat 1Dokument8 SeitenJurnal Kompetensi Perawat 1Suki HanantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pengembangan KurikulumDokument11 SeitenPengembangan KurikulumLUtfatulatifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Community Engagement in Education ProgramsDokument12 Seiten2 Community Engagement in Education Programssharmakhan433Noch keine Bewertungen

- Practical School Community Partnership Leading To Succesful Educatinal Leaders 1013145Dokument8 SeitenPractical School Community Partnership Leading To Succesful Educatinal Leaders 1013145AD ASSOCIATES SDN BHDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Participation in Quality EducationDokument9 SeitenCommunity Participation in Quality EducationBishnu Prasad Mishra100% (5)

- Jurnal Kompetensi Perawat 4Dokument11 SeitenJurnal Kompetensi Perawat 4Suki HanantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Opening Doors To Community CollaborationDokument4 SeitenAdvanced Practice Nursing Education: Opening Doors To Community Collaborationscifer_06Noch keine Bewertungen

- Operational Definitions 062021Dokument3 SeitenOperational Definitions 062021Hollister OfficialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Participation in School EducatDokument8 SeitenCommunity Participation in School EducatmohammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Participation in EducationDokument35 SeitenCommunity Participation in EducationJayCesarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aprendizaje Servicio y EIPDokument6 SeitenAprendizaje Servicio y EIPNAYITA_LUCERONoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter On School Community RelationshipDokument34 SeitenChapter On School Community Relationshipsaleha shahid100% (1)

- Culminatingexperience Presentation 690Dokument9 SeitenCulminatingexperience Presentation 690api-522465317Noch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Reading 3Dokument9 SeitenJournal Reading 3Ronaly Angalan TinduganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Responsibility PDFDokument18 SeitenSocial Responsibility PDFDewiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept Note On Community ParticipationDokument7 SeitenConcept Note On Community ParticipationLikassa LemessaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Participation in The Primary Schools of Selected Districts in The PhilippinesDokument35 SeitenCommunity Participation in The Primary Schools of Selected Districts in The PhilippinesNamoAmitofou50% (2)

- Reduce PrejudiceDokument3 SeitenReduce PrejudiceHarshitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Community Health Module 1Dokument40 SeitenIntroduction To Community Health Module 1abdullahi bashiirNoch keine Bewertungen

- GROUP6PPTDokument60 SeitenGROUP6PPTmIrangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Extension Services BodyDokument17 SeitenCommunity Extension Services BodyDhanessa CondesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Development Research PapersDokument5 SeitenCommunity Development Research Papershozul1vohih3100% (1)

- Chapter 2 PrintDokument15 SeitenChapter 2 Printcharls xyrhen BalangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 and 2Dokument17 SeitenChapter 1 and 2noel edison flojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 Making Schools InclusiveDokument18 SeitenChapter 3 Making Schools InclusiveleamartinvaldezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evert ArticleDokument5 SeitenEvert Articleapi-165286810Noch keine Bewertungen

- Order #474974790Dokument4 SeitenOrder #474974790s.macharia1643Noch keine Bewertungen

- Argumentative Essay Examples UniversityDokument4 SeitenArgumentative Essay Examples UniversityShining of HopeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHS Community EngagementDokument16 SeitenSHS Community EngagementMANNY CARAJAYNoch keine Bewertungen

- ThesisDokument22 SeitenThesisZorayda AbubakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 Ed7Dokument10 SeitenChapter 3 Ed7Agnes Abegail AcebuqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elev8 Oakland Community Schools Cost Benefit AnalysisDokument17 SeitenElev8 Oakland Community Schools Cost Benefit Analysisapi-242719112Noch keine Bewertungen

- Community Involvement Practices of Public Secondary School TeachersDokument13 SeitenCommunity Involvement Practices of Public Secondary School TeachersPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- CESC12 Q1 M6 Forms of Community EngagementDokument16 SeitenCESC12 Q1 M6 Forms of Community EngagementJeffrey LozadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 127-Manuscript (Title, Abstract, Introduction, Materials and Methods, Etc.) - 516-1-10-20200814 PDFDokument10 Seiten127-Manuscript (Title, Abstract, Introduction, Materials and Methods, Etc.) - 516-1-10-20200814 PDFhayascent hilarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relationships Between Service-Learning, Social Justice, Multicultural Competence, and Civic EngagementDokument16 SeitenThe Relationships Between Service-Learning, Social Justice, Multicultural Competence, and Civic EngagementKenny BayudanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 4 Making Schools Inclusive PDFDokument25 SeitenModule 4 Making Schools Inclusive PDFMariane Joy TecsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- CESC12 Q1 M6 Forms of Community EngagementDokument16 SeitenCESC12 Q1 M6 Forms of Community EngagementKim Bandola0% (1)

- Embedding Community-Based Service Learning Into Psychology Degrees at UKZN, South AfricaDokument15 SeitenEmbedding Community-Based Service Learning Into Psychology Degrees at UKZN, South Africatangwanlu9177Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Transforming Schools Into Learning CommunitiesDokument8 SeitenRunning Head: Transforming Schools Into Learning CommunitiesBenjamin L. StewartNoch keine Bewertungen

- School Com2 8Dokument10 SeitenSchool Com2 8Lian CopasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cesc12 q1 m6 Forms of Community Engagement PDFDokument16 SeitenCesc12 q1 m6 Forms of Community Engagement PDFKim BandolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community DevelopmentDokument4 SeitenCommunity DevelopmentkaboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustaining ChangeDokument5 SeitenSustaining ChangeAmna GhafoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prof Ed 4 Unit 2 LP 2Dokument24 SeitenProf Ed 4 Unit 2 LP 2Aniway Rose Nicole BaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Education and Advocacy: Student's Name Affiliation Course Instructor DateDokument7 SeitenCommunity Education and Advocacy: Student's Name Affiliation Course Instructor DateMike NgangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EJ1259929Dokument16 SeitenEJ1259929Collince OchiengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broadening Participation in CommunityDokument34 SeitenBroadening Participation in CommunityEdgarsito AyalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 9 - Concepts and Principles of ImmersionDokument20 SeitenModule 9 - Concepts and Principles of ImmersionAlyssa ValenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A - Behavioral - Approach - To - Leade PDFDokument14 SeitenA - Behavioral - Approach - To - Leade PDFCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overseas Filipino Workers in Conflict Zones NarratDokument21 SeitenOverseas Filipino Workers in Conflict Zones NarratCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Care Providers Handbook On Muslim PatientsDokument22 SeitenHealth Care Providers Handbook On Muslim PatientsCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code of Ethics For Nurses 2012Dokument12 SeitenCode of Ethics For Nurses 2012Ar Jhay100% (1)

- Patients' - Needs - Trump - BeliefsDokument2 SeitenPatients' - Needs - Trump - BeliefsCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- QM ch6Dokument31 SeitenQM ch6Shrestha HemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Shortages in The OR: Solutions For New Models of EducationDokument23 SeitenNursing Shortages in The OR: Solutions For New Models of EducationCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- CriteriaDokument27 SeitenCriteriaCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Delivery SystemDokument22 SeitenNursing Care Delivery SystemFeFo Gh100% (5)

- An Integrative Review of EngagDokument9 SeitenAn Integrative Review of EngagCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Students' PerceptionsDokument5 SeitenNursing Students' PerceptionsCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Delivery Systems: Issues and TrendsDokument21 SeitenNursing Care Delivery Systems: Issues and TrendsCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Etica 2Dokument7 SeitenEtica 2lauraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Better Nurse Staffing and Work Environment Associated With Increased Survival To In-Hospital Cardiac ArrestDokument17 SeitenBetter Nurse Staffing and Work Environment Associated With Increased Survival To In-Hospital Cardiac ArrestCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Med Surg BulletDokument12 SeitenMed Surg BulletCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Better Nurse Staffing and Work Environment Associated With Increased Survival To In-Hospital Cardiac ArrestDokument17 SeitenBetter Nurse Staffing and Work Environment Associated With Increased Survival To In-Hospital Cardiac ArrestCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transitioning From Acute To Primary Health Care Nursing - An Integ PDFDokument40 SeitenTransitioning From Acute To Primary Health Care Nursing - An Integ PDFCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- More Than A Warm Body HiringDokument2 SeitenMore Than A Warm Body HiringCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- INGREDIENTSDokument1 SeiteINGREDIENTSCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Designing Individualized Nursing OrientationDokument3 SeitenDesigning Individualized Nursing OrientationCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organization Development and Change UhuhDokument2 SeitenOrganization Development and Change UhuhCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vice Ganda: New Microsoft Word DocumentDokument8 SeitenVice Ganda: New Microsoft Word DocumentCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAMPLE - HAAD - QUESTION - Docx Filename - UTF-8''SAMPLE HAAD QUESTIONDokument36 SeitenSAMPLE - HAAD - QUESTION - Docx Filename - UTF-8''SAMPLE HAAD QUESTIONCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Learning Objectives Describe What You Will Gain by Utilizing The Learning Activities and Resources in The Learning Resource Toolkit.Dokument4 SeitenThe Learning Objectives Describe What You Will Gain by Utilizing The Learning Activities and Resources in The Learning Resource Toolkit.Cham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Billy Joe CrawfordDokument12 SeitenBilly Joe CrawfordCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jose Marie Borja ViceralDokument8 SeitenJose Marie Borja ViceralCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vice Ganda: New Microsoft Word DocumentDokument8 SeitenVice Ganda: New Microsoft Word DocumentCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Athletics The Ancient Greeks: Sponsored Links Osaka HistoryDokument2 SeitenAthletics The Ancient Greeks: Sponsored Links Osaka HistoryCham SaponNoch keine Bewertungen

- Csec NCPDokument4 SeitenCsec NCPAngelica Murillo Ang-AngcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Order ID 352758453Dokument6 SeitenOrder ID 352758453James NdiranguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salinan Terjemahan Teks Basing DramaDokument2 SeitenSalinan Terjemahan Teks Basing DramaArdhalena DhikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PB1 - NP2Dokument12 SeitenPB1 - NP2Denzelle ZchalletNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Practice QuestionsDokument12 SeitenReview Practice QuestionsJhannNoch keine Bewertungen

- TIGER Initiative Informatics DefinitionsDokument9 SeitenTIGER Initiative Informatics DefinitionslaggantigganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frequently Cause Stress To Nursing StudentsDokument9 SeitenFrequently Cause Stress To Nursing StudentsEltrik SetiyawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCP HyperthermiaDokument2 SeitenNCP HyperthermiaMeljonesDaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challenges For Nursing Students in The Clinical Learning EnvironmDokument117 SeitenChallenges For Nursing Students in The Clinical Learning EnvironmCarla Jane Mirasol Apolinario100% (2)

- Dorothy E. Johnson's Behavioral System ModelDokument9 SeitenDorothy E. Johnson's Behavioral System ModelMichael Angelo SeñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Double Effect ASSIGNMENTDokument5 SeitenEthical Double Effect ASSIGNMENTKrea kristalleteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 2Dokument28 SeitenLecture 2Justiniano Jadraque Medel Jr (Justin)Noch keine Bewertungen

- PICU NICU OrientationDokument8 SeitenPICU NICU OrientationSony PrabowoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Evaluation MSC Nursing Programme Offered by Inc & AiimsDokument8 SeitenCritical Evaluation MSC Nursing Programme Offered by Inc & AiimsManisha ThakurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article IDokument8 SeitenArticle IMuhammad Nuril Wahid FauziNoch keine Bewertungen

- EXAM 2 RationaleDokument1 SeiteEXAM 2 RationaleSkye M. PetersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Process and DocumentationDokument52 SeitenNursing Process and Documentationgeorgeloto12100% (2)

- AG Fitch Joins MS Doctor in Challenging New Federal Rules For Anti-Racism Plans in Medical PracticesDokument26 SeitenAG Fitch Joins MS Doctor in Challenging New Federal Rules For Anti-Racism Plans in Medical PracticesRuss LatinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- LGBTIQ HealthDokument7 SeitenLGBTIQ HealthThomas MooreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Health Nursing: Individual Record of Skills Return DemonstrationDokument15 SeitenCommunity Health Nursing: Individual Record of Skills Return DemonstrationThimiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occupational Health Hazards and ManegementDokument20 SeitenOccupational Health Hazards and ManegementPrabh GillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nurse Call A and E Powerpoint DOC0696731 BY GEDokument92 SeitenNurse Call A and E Powerpoint DOC0696731 BY GEAmal RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Betz Rebecca ResumeDokument2 SeitenBetz Rebecca Resumeapi-316054946Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sample CVDokument4 SeitenSample CVkage1205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Triage JiwaDokument5 SeitenTriage JiwaFebri Ayu MentariNoch keine Bewertungen

- OET - Speaking Tips - Verb - NounDokument16 SeitenOET - Speaking Tips - Verb - NounReji Mat100% (1)

- Community Healthcare Family Nursing Care Plan Presence of Breeding SitesDokument2 SeitenCommunity Healthcare Family Nursing Care Plan Presence of Breeding SitesAndrea LapuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salem Hospital Plan of Correction 7-28-11Dokument2 SeitenSalem Hospital Plan of Correction 7-28-11Statesman JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: Diane FotheringhamDokument6 SeitenInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Diane FotheringhamDANIELNoch keine Bewertungen