Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Do School Bags Cause Back Pain?

Hochgeladen von

TOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Do School Bags Cause Back Pain?

Hochgeladen von

TCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review

Do schoolbags cause back pain in children and

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 on 2 May 2018. Downloaded from http://bjsm.bmj.com/ on 18 July 2019 by guest. Protected by copyright.

adolescents? A systematic review

Tiê Parma Yamato,1,2,3 Chris G Maher,1,4 Adrian C Traeger,1 Christopher M Wiliams,2,3,5

Steve J Kamper1,3

►► Additional material is Abstract report mostly unclear associations.4 Some evidence

published online only. To view Objective To investigate whether characteristics of suggests that psychosocial factors (eg, distress),

please visit the journal online

(http://d x.doi.o rg/10.1136/ schoolbag use are risk factors for back pain in children female gender and smoking may increase the risk

bjsports-2017-098927). and adolescents. of back pain in this population.4 The evidence for

Data sources Electronic searches of MEDLINE, anthropometric factors (eg, height, weight), posture

1

Institute for Musculoskeletal EMBASE and CINAHL databases up to April 2016. and lifestyle factors is mixed and of generally poor

Health, Sydney Local Health

District, The University of

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies Prospective quality.4 Although loading or biomechanical factors

Sydney, Sydney, New South cohort studies, cross-sectional and randomised controlled are frequently cited as causes for back pain in

Wales, Australia trials conducted with children or adolescents. The primary children and adolescents, the evidence is inconsis-

2

Hunter New England outcome was an episode of back pain and the secondary tent.4 10

Population Health, Hunter New outcomes were an episode of care seeking and school

England Local Health District,

Schoolbag characteristics are one biomechan-

Wallsend, New South Wales, absence due to back pain. We weighted evidence from ical factor often implicated as a cause of back

Australia longitudinal studies above that from cross-sectional. The pain in children and adolescents. Despite the lack

3

Centre for Pain, Health and risk of bias of the longitudinal studies was assessed by a of convincing evidence, schoolbags have been

Lifestyle, Australia modified version of the Quality in Prognosis Studies tool.

4 traditionally linked to back pain in children and

Institute for Musculoskeletal

Results We included 69 studies (n=72 627), of which adolescents.11 Heightened awareness of this issue

Health, The University of Sydney,

Sydney, New South Wales, five were prospective longitudinal and 64 cross-sectional by the general public means that clinicians are

Australia or retrospective. We found evidence from five prospective frequently asked for advice on a preferred style

5

School of Medicine and studies that schoolbag characteristics such as weight, of schoolbag and/or how to carry the schoolbag

Public Health, Hunter Medical design and carriage method do not increase the risk of

Research Institute, University to reduce risk of back pain.12 More specifically,

of Newcastle, Newcastle, New developing back pain in children and adolescents. The the attention on the magnitude of load carried by

South Wales, Australia included studies were at moderate to high risk of bias. children and adolescents to and from school has

Evidence from cross-sectional studies aligned with that been increasing.

Correspondence to from longitudinal studies (ie, there was no consistent To date, there is variation regarding recommenda-

Dr Tiê Parma Yamato, pattern of association between schoolbag use or type tions for children and adolescents carrying school-

Musculoskeletal Health Sydney, and back pain). We were unable to pool results due to

School of Public Health, Sydney bags.13 Guidelines for safe loads are mostly within

Medical School, The University different variables and inconsistent results. 10%–15% of body weight (BW) range but include

of Sydney, Sydney NSW 2050, Summary/conclusion There is no convincing evidence values as low as 5%14 and as high as 20%.15 Some

Australia; that aspects of schoolbag use increase the risk of back biomechanical studies suggest that the schoolbag

t ie.yamato@s ydney.edu.a u pain in children and adolescents.

weight of 10% of BW may be enough to cause

Accepted 20 February 2018 changes in kinematics, body posture and muscular

Published Online First strain.16 17 The evidence investigating the associa-

2 May 2018

Introduction tion between schoolbag weight or other schoolbag

Back pain is well known for its frequency and characteristics and the risk of back pain is incon-

global burden.1 The mean point prevalence of low clusive and not helpful to determine any choice of

back pain (LBP) in adults is estimated as 18.3% and limit or recommendations regarding schoolbags.4 15

1-year prevalence is 38%,1 while the 1-year prev- A greater understanding of schoolbag-related risk

alence rates for mid-back pain range from 15% to factors for back pain is important to determine

35%.2 Epidemiological data have shown that back appropriate preventative action for children and

pain is not only a health problem for adults but is adolescents.18

also frequently reported by children and adoles- The aim of this study is to investigate whether

cents.3 4 The prevalence of back pain reported by characteristics of schoolbag use (eg, weight, dura-

children and adolescents is high in many parts of tion of use, bag design, method of carrying bag,

the world,5 and prevalence increases rapidly with perceived weight) are risk factors for back pain in

age through adolescence.6 A recent large multina- children and adolescents.

tional study reported that the self-reported preva-

lence of back pain was 27%, 37% and 47% among

children aged 11, 13 and 15 years, respectively.7 Methods

Other studies found that by the age of 14–17 years, The protocol for this review was registered

11%–71% have experienced at least one episode of prospectively on International Prospective Register

To cite: Yamato TP, back pain.8 9 for Systematic Reviews (CRD 42016037689). This

Maher CG, Traeger AC, The aetiology of back pain in children and systematic review is reported according to the

et al. Br J Sports Med adolescents is unknown. Studies investigating risk Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epide-

2018;52:1–6. factors for back pain in children and adolescents miology checklist.19

Yamato TP, et al. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:1241–1245. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 1 of 6

Review

Searches was rated low for both study attrition and study confounding.

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 on 2 May 2018. Downloaded from http://bjsm.bmj.com/ on 18 July 2019 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Systematic searches were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias of the studies inde-

and CINAHL from their inception until November 2017. The pendently and discrepancies were resolved by consensus, if

search strategy included spinal pain terms, terms related to necessary, a third author helped to reach the consensus. We

children and adolescents and terms related to schoolbags; the planned to incorporate risk of bias ratings into interpretation of

search strategy was based on previous Cochrane reviews in rele- findings by comparing results from studies at low risk of bias to

vant areas (online supplementary appendix 2). Additional strat- those from the total pool of included studies.

egies (eg, examination of reference lists and citation tracking of

included studies) were used to identify further eligible studies. Data synthesis

Searches were not limited by language; collaborators with the Longitudinal and cross-sectional designs were assessed sepa-

relevant language skills assessed studies published in languages rately. To analyse whether characteristics of schoolbag use are risk

other than English, Portuguese and Spanish. factors for back pain, the relationship between schoolbag char-

acteristics and back pain was explored and pooled if adequate

Study selection numbers of longitudinal studies examining similar risk factors

We included prospective longitudinal cohort studies, cross-sec- were identified. For the cross-sectional studies, we performed

tional studies and randomised controlled trials (RCT) that a descriptive analysis to report the factors associated with back

studied back pain as the main outcome. Eligible studies needed to pain. We made the decision a priori to primarily base conclu-

include children or adolescents of school age as participants and sions on findings from longitudinal studies because they offer a

report information about ‘carrying a backpack’. Two reviewers more robust design for making causal inferences. The decision

independently screened titles and abstracts and excluded irrel- as to whether to pool studies was made on the basis of clinical

evant records. Full-text articles were assessed by two reviewers and methodological homogeneity; this involved subjective deci-

independently to identify studies that met the inclusion criteria. sion based on consensus among the authors. Key factors in this

Any disagreement was resolved by consensus. decision included measures of exposure and outcome, timing of

data collection and reporting of analyses.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was an episode of back pain with no Results

restriction for duration. We considered lumbosacral, lumbar and The searches retrieved 6597 studies. After removing duplicates

thoracic pain as ‘back pain’. The secondary outcomes were an and screening titles and abstracts, we included 160 studies for

episode of care seeking for back pain (ie, one or more consulta- full-text assessments; we could not access the full-text for six

tions with a healthcare provider for back pain) and an episode of of these studies and attempts to contact the authors were not

school absence due to back pain.20 successful. A total of 69 studies met our inclusion criteria and

were included in this review (total n=72 627 participants). We

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment included four longitudinal cohort studies (n=1743), one RCT

All data were extracted by two reviewers independently. Where (n=108), 63 cross-sectional studies (n=70 720) and one case–

necessary, study authors were contacted by email in order to control with retrospective data (n=56) (figure 1). The character-

obtain additional information that was not reported in the arti- istics of the prospective studies (longitudinal cohort and RCT)

cles. The following data were extracted from each study: are described in table 1, and the characteristics of the cross-sec-

►► study characteristics: source of patients, sample size, tional and case–control studies are described in the online

follow-up period and loss to follow-up; supplementary appendix 1. It was not possible to pool data due

►► number of new episodes of back pain during study period to heterogeneity regarding exposure (backpack) and outcome

(primary outcome); (back pain) measures.

►► number of episodes of care seeking for back pain and

episodes of school absence due to back pain (secondary Prospective studies

outcomes); The five prospective studies were judged as moderate to high

►► weight of schoolbag (absolute weight or expressed as the risk of bias for most risk of bias domains from QUIPS (table 2).

percentage of child’s BW); Two studies21 22 were rated as high risk of bias and three23–25

►► other characteristics of schoolbag use (eg, duration of use, as moderate risk of bias. The domains of ‘study attrition’,

bag design, method of carrying bag, perceived weight); ‘prognostic factor measurement’ and ‘study confounding’ were

►► statistical measure to quantify association (eg, relative risk, the most poorly described domains. The domain of ‘outcome

OR, HR) and 95% CI. measurement’ was the best described. Due to the high hetero-

The risk of bias assessment of the longitudinal studies was geneity between included studies, we have presented results

assessed by a modified version of the Quality in Prognosis descriptively.

Studies (QUIPS) tool, which has been recommended by the Two prospective studies (one longitudinal cohort23 and one

Cochrane Prognosis Methods Group. The QUIPS was modified RCT22) evaluated associations between schoolbag weight (%

to judge bias in relation to risk factors, instead of the original BW) and risk of developing LBP; neither reported an associa-

tool’s focus on prognostic factors. The following six domains tion. Based on the QUIPS rating for these two studies, weighting

were considered: (1) study participation, (2) study attrition, (3) by sample size, we consider this moderate quality evidence for

measurement of risk factor, (4) measurement of, and controlling no relationship between backpack weight and back pain.

for confounding variables, (5) measurement of outcomes and (6) Two longitudinal studies evaluated ‘perception of schoolbag

analysis and reporting. Each domain was assessed as having high, weight’ and risk of LBP. One study21 found that children with

moderate or low risk of bias. The overall risk of bias was also back pain who reported difficulty carrying their schoolbag had

assessed. We considered a study to be of high quality when the increased in risk of developing persistent LBP (RR 2.1, 95% CI

risk of bias was rated low on at least four of the six domains and 1.1 to 4.0). Another study25 also reported an association between

2 of 6 Yamato TP, et al. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:1241–1245. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927

Review

question on ‘pain-provoking situations’ none

approximately twofold to threefold increase

LBP was not associated with load carried or

of them mentioned carrying the schoolbag

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 on 2 May 2018. Downloaded from http://bjsm.bmj.com/ on 18 July 2019 by guest. Protected by copyright.

No schoolbag variables reported—for the

Incidence of LBP was not associated with

carrying their schoolbag experienced an

load carried, bag design or method of

No quantitative Perceived weight of schoolbag was

Children who reported difficulty

in risk of persistent back pain

weight of schoolbag (% BW)

associated with LBP

Main findings

carrying

data reported

Perceived

weight

–

–

bags at all: n=35 (9.2%)

(25.72%); did not use

Method of carrying

On their back: n=248

(65.09%); on their

shoulder: n=98

bag

–

–

Load carried (kg)

Median 4.7 kg

Mean: 8.75 kg

(IQR 3.7–6.0)

(SD 1.26)

–

Weight of schoolbag

Median 9.9% of BW

Mean: 19.9% of BW

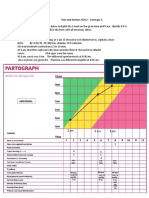

Figure 1 Flow chart of the included studies in this review.

(IQR 7.4–12.9%)

(% BW)

(SD 5.3)

the perception of schoolbag weight as heavy and LBP (OR 2.2,

95% CI 1.0 to 4.8). Based on the QUIPS rating for these two –

LBP: lifetime at baseline: 104 –

studies, we consider this low quality evidence for a relationship

(36%); lifetime at follow-up:

Prevalence of back pain

between perception of backpack weight and back pain.

13 (4.5%); recent onset at

Recent onset at baseline:

3 years (follow-up) 39%

Another longitudinal study24 did not investigate schoolbag

LBP: Point 330 (24%)

follow-up: 16 (5.6%)

Point 168 (18.6%)

weight or perception of weight; however, for the question on

3 month 41.9%

LBP: Point 58%

Lifetime 58.4%

‘pain provoking situations’, none of the participants mentioned

101 (35%).

that carrying the schoolbag provoked pain. None of the prospec-

tive longitudinal studies reported data on duration of using a

LBP:

LBP:

schoolbag, episodes of care seeking for back pain or episodes of

school absence due to back pain. The results from longitudinal

Sample size

1376 (330

studies are summarised in table 3.

followed)

108

933

392

All schoolchildren (and their parents) 88

Cross-sectional and case-control studies

Mean age: 11.2 years (range 10–12)

School children in Antwerp, Belgium

Twenty-eight studies investigated weight of schoolbag (% BW),

Middle school in Italy (Mantua)

ranging from 5% to 19% BW, and 29 studies investigated load

BW, body weight; LBP, low back pain; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Mean age: 14.7 years (SD 0.7)

Age between 11 and 14 years

Age between 11 and 14 years

carried, which ranged from 2 kg to 10 kg. Fourteen studies

Table 1 Characteristics of the included studies

Source and age group

(Northwest of England)

investigated duration of use of the schoolbag (ie, time carrying),

39 Secondary schools

39 Secondary schools

(Northwest England)

ranging from 20 to 85 min per day. Regarding schoolbag design

in Eastern Norway

and method of carrying the bag, 22 studies reported that most

Age: 9 years

students used backpacks or rucksacks (around 90%) and carried

the schoolbag on both shoulders (around 75%), and a minority

of students used satchels or shoulder bags carried on one

shoulder or by hand.

Longitudinal

Longitudinal

Longitudinal

Longitudinal

Twenty-nine cross-sectional studies did not find an associa-

tion between schoolbag characteristics and LBP.26–54 Four studies

Design

cohort

cohort

cohort

cohort

RCT

reported a positive association between the child’s perception of

backpack weight and back pain.55–58 Three studies reported asso-

Szpalski et al25

ciations between the duration of carrying a back pack (prolonged

Negrini et al22

Macfarlane21

periods) and back pain.57 59 60 Four studies reported associations

Jones and

Jones and

Watson23

Sjolie24

between schoolbag weight (heavier) and back pain,60–63 and

Study

other three studies found an association between the method of

Yamato TP, et al. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:1241–1245. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 3 of 6

Review

Table 2 Risk of bias assessment for the prospective studies

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 on 2 May 2018. Downloaded from http://bjsm.bmj.com/ on 18 July 2019 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Outcome

Study Study participation Study attrition Prognostic factor measurement Study confounding Statistical analysis and reporting

23

Jones and Watson Moderate Moderate Moderate Low Moderate Moderate

Jones and Macfarlane21 High High High Low High High

Sjolie24 Low Moderate High Low High Moderate

Szpalski et al25 Moderate High Moderate Moderate Moderate Moderate

Negrini et al22 2004 Moderate High High High High High

carrying the schoolbags (one shoulder or asymmetrically) with there is a causal relationship between backpack use and

back pain.42 64 65 For the retrospective case–control study, there back pain, we expected that cross-sectional studies would

were no data regarding the schoolbag weight or features, but consistently report an association between the two variables,

75% of the subjects with chronic non-specific LBP reported that but this evidence of itself would be insufficient. Hence, we

carrying a schoolbag aggravated their pain. expected that data from cross-sectional studies could corrob-

Episodes of care seeking for back pain were reported in 14 orate inference of a causal association, or lack thereof in the

cross-sectional studies.27 30 35 37 38 42–44 61 64 66–69 The prevalence longitudinal data. In this study, we also performed a compre-

of care seeking ranged from 1.6% to 35% (median 18.5, IQR hensive search, we registered the protocol and we assessed

8.6–23.3). However, none of the studies investigated the asso- the risk of bias of the included studies using robust methods.

ciation between schoolbag use and care seeking for back pain. This study has limitations. We only found five prospective

School absence due to back pain was reported in six cross-sec- studies to include in this review. Since these studies investi-

tional studies,27 30 38 41 55 61 with median prevalence of 7.8% of gated different variables and present results inconsistently,

absence for one or more days (IQR 1.8–20.5). However, none we were unable to pool results. Despite these limitations,

of the studies investigated the association between schoolbag use the volume of research and the fact that associations show

and school absence due to back pain. no consistent pattern suggest that any relationship between

Because we anticipated different definitions of back pain backpack use and back pain is minimal at best, and research

episodes, we planned a sensitivity analysis to explore the influ- resources aimed at understanding adolescent back pain are

ence of episode definition on risk. However, for the prospective better directed elsewhere.

studies, the definitions were all were very similar, so we did not Previous reviews have investigated the association between

perform this analysis. back pain and schoolbag characteristics (ie, weight, type, method

of carrying) in children and adolescents.9 13 15 70–73 Although

Discussion most of these reviews are based on data from cross-sectional

This systematic review provides evidence from prospective studies, their results generally agree with our findings (ie, there

studies with moderate to high risk of bias that schoolbag char- appears no clear association between schoolbags characteris-

acteristics such as weight, design and carriage method do not tics and back pain in children and adolescents). Most of these

increase the risk of developing back pain in children and adoles- reviews are narrative reviews or investigated risk factors without

cents. Two prospective studies reported that the perception of considering longitudinal data. Our review extends the findings

heaviness or difficulty in carrying the schoolbag were associ- of previous studies by providing evidence from five prospective

ated with back pain and persistent symptoms. Evidence from longitudinal studies, which show there is little or no association

cross-sectional studies supported the findings from prospec- between schoolbag use and back pain.

tive studies. Taken together, these results are not suggestive of Schoolbag use does not appear to be an important risk factor

a meaningful relationship between backpack use or weight and for back pain in children and adolescents. However, due to

back pain in children and adolescents. the small number of prospective studies and low methodolog-

The strength of this review is that we focused on data from ical quality of the studies included in this review, our findings

prospective studies that investigated schoolbag characteristics should be interpreted with caution. There are few longitudinal

and the risk of back pain, yet also included cross-sectional cohort studies in children and adolescents in the literature, and

and retrospective studies to capture all possible relevant in most of these cases identifying risk factors for back pain was

information on the topic. Data from the latter studies were not the primary aim. Consequently, the choice of exposure vari-

considered with respect to the extent to which they were ables, measurement instruments and timing of data collection

concordant with the longitudinal studies. In the event that are not optimal to reveal causal relationships. These problems

Table 3 Results from longitudinal studies included in the review.

Study n Schoolbag measures Back pain measures Finding

Negrini et al22 (RCT) 108 % Body weight Back pain episode No association

Load carried No association

Jones and Watson23 933 Load carried Back pain episode No association

Bag design No association

Carrying method No association

Jones and Macfarlane21 330 Difficulty carrying schoolbag Persistent back pain Increased risk: RR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.0

Sjolie24 88 Schoolbag use Pain-provoking situations No association

Szpalski25 392 Perceived weight Back pain episode Increased odds: OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.0 to 4.8

4 of 6 Yamato TP, et al. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:1241–1245. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927

Review

may explain why systematic reviews in this field do not have 16 Devroey C, Jonkers I, de Becker A, et al. Evaluation of the effect of backpack load

and position during standing and walking using biomechanical, physiological and

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 on 2 May 2018. Downloaded from http://bjsm.bmj.com/ on 18 July 2019 by guest. Protected by copyright.

strong conclusions.

subjective measures. Ergonomics 2007;50:728–42.

These findings call into question the various guidelines and 17 Mackie HW, Legg SJ. Postural and subjective responses to realistic schoolbag carriage.

statements that endorse specific weight limits for school bags in Ergonomics 2008;51:217–31.

children and adolescents.13–15 It seems that these recommenda- 18 Trevelyan FC, Legg SJ. Risk factors associated with back pain in New Zealand school

tions are not based on the most reliable evidence on the subject. children. Ergonomics 2011;54:257–62.

19 Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in

The findings also have implications for the various professional

epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in

bodies and clinicians that endorse or recommend specific back- Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12.

packs. It is important that such endorsement is made on the basis 20 de Vet HC, Heymans MW, Dunn KM, et al. Episodes of low back pain: a proposal for

of firm evidence and free of financial conflict. uniform definitions to be used in research. Spine 2002;27:2409–16.

21 Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ. Predicting persistent low back pain in schoolchildren: a

prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1359–66.

Conclusion 22 Negrini S, Politano E, Carabalona R, et al. The backpack load in schoolchildren: clinical

Based on evidence from five longitudinal studies (n=1851 chil- and social importance, and efficacy of a community-based educational intervention. A

prospective controlled cohort study. Eura Medicophys 2004;40:185–90.

dren and adolescents) and more than 60 cross-sectional studies, 23 Jones GT, Watson KD, Silman AJ, et al. Predictors of low back pain in British

there is no convincing evidence that aspects of schoolbag use schoolchildren: a population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatrics

increase the risk of back pain. There is some evidence that the 2003;111:822–8.

perception of heaviness is associated with back pain. 24 Sjolie AN. Persistence and change in nonspecific low back pain among adolescents: a

3-year prospective study. Spine 2004;29:2452–7.

25 Szpalski M, Gunzburg R, Balagué F, et al. A 2-year prospective longitudinal study on

Acknowledgements TPY holds a PhD scholarship from CAPES (Coordination low back pain in primary school children. Eur Spine J 2002;11:459–64.

for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel), Ministry of Education of 26 Akdag B, Cavlak U, Cimbiz A, et al. Determination of pain intensity risk factors among

Brazil. CGM, CMW and SJK’s fellowship are funded by Australia’s National Health school children with nonspecific low back pain. Med Sci Monit 2011;17:PH12–15.

and Medical Research Council. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Bruno 27 Bejia I, Abid N, Ben Salem K, et al. Low back pain in a cohort of 622 Tunisian

Saragiotto for critical revision of the manuscript and data analysis. schoolchildren and adolescents: an epidemiological study. Eur Spine J

Contributors TPY performed this study as part of her PhD degree, she led the 2005;14:331–6.

main writing, screening, data extraction and analysis. CGM was her supervisor and 28 Cavlak U, Cimbiz A, Akdag B. Non specific low back pain in a Turkish population

contributed with the concept idea and guiding during the study. ACT, CMW and SJK based sample of school children: a field survey with analysis of associated factors. The

contributed with revision, screening, data extraction and interpretation of the study. Pain Clinic 2006;18:351–60.

29 Dockrell S, Simms C, Blake C. Schoolbag carriage and schoolbag-related

Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the

musculoskeletal discomfort among primary school children. Appl Ergon

public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

2015;51:281–90.

Competing interests None declared. 30 Gunzburg R, Balagué F, Nordin M, et al. Low back pain in a population of school

Patient consent Not required. children. Eur Spine J 1999;8:439–43.

31 Johnson OE, Adeniji OA, Mbada CE, et al. Percent of body weight carried by

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed. secondary school students in their bags in a nigerian school. J Musculoskelet Res

© Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the 2011;14:1250003.

article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise 32 Kaspiris A, Grivas TB, Zafiropoulou C, et al. Nonspecific low back pain during

expressly granted. childhood: a retrospective epidemiological study of risk factors. J Clin Rheumatol

2010;16:55–60.

33 Korovessis P, Koureas G, Zacharatos S, et al. Backpacks, back pain, sagittal spinal

References curves and trunk alignment in adolescents: a logistic and multinomial logistic analysis.

1 Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low Spine 2005;30:247–55.

back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2028–37. 34 Korovessis P, Repantis T, Baikousis A. Factors affecting low back pain in adolescents. J

2 Briggs AM, Smith AJ, Straker LM, et al. Thoracic spine pain in the general population: Spinal Disord Tech 2010;23:513–20.

prevalence, incidence and associated factors in children, adolescents and adults. A 35 Kovacs FM, Gestoso M, Gil del Real MT, et al. Risk factors for non-specific low

systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:77. back pain in schoolchildren and their parents: a population based study. Pain

3 Kamper SJ, Henschke N, Hestbaek L, et al. Musculoskeletal pain in children and 2003;103:259–68.

adolescents. Braz J Phys Ther 2016:275–84. 36 Macedo RB, Coelho-e-Silva MJ, Sousa NF, et al. Quality of life, school backpack

4 Kamper SJ, Yamato TP, Williams CM. The prevalence, risk factors, prognosis and weight, and nonspecific low back pain in children and adolescents. J Pediatr

treatment for back pain in children and adolescents: an overview of systematic 2015;91:263–9.

reviews. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016;30:1021–36. 37 Minghelli B, Oliveira R, Nunes C. Non-specific low back pain in adolescents from the

5 Akdag B, Cavlak U, Cimbiz A, et al. Determination of pain intensity risk factors south of Portugal: prevalence and associated factors. J Orthop Sci 2014;19:883–92.

among school children with nonspecific low back pain. Medical Science Monitor 38 Murphy S, Buckle P, Stubbs D. A cross-sectional study of self-reported back and neck

2011;17:PH12–5. pain among English schoolchildren and associated physical and psychological risk

6 Olsen TL, Anderson RL, Dearwater SR, et al. The epidemiology of low back pain in an factors. Appl Ergon 2007;38:797–804.

adolescent population. Am J Public Health 1992;82:606–8. 39 Negrini S, Carabalona R. Backpacks on! Schoolchildren’s perceptions of load,

7 Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, et al. An International survey of pain in associations with back pain and factors determining the load. Spine 2002;27:187–95.

adolescents. BMC Public Health 2014;14:447. 40 Onofrio AC, da Silva MC, Domingues MR, et al. Acute low back pain in high school

8 Skoffer B. Low Back pain in 15- to 16-year-old children in relation to school furniture adolescents in Southern Brazil: prevalence and associated factors. Eur Spine J

and carrying of the school bag. Spine 2007;32:E713–7. 2012;21:1234–40.

9 Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen JJ. Non-specific low back pain in children and 41 Shehab DK, Al-Jarallah KF. Nonspecific low-back pain in Kuwaiti children and

adolescents: risk factors. Eur Spine J 1999;8:429–38. adolescents: associated factors. J Adolesc Health 2005;36:32–5.

10 Nicolet T, Mannion AF, Heini P, et al. No kidding: low back pain and type of container 42 Skoffer B. Low back pain in 15- to 16-year-old children in relation to school furniture

influence adolescents’ perception of load heaviness. Eur Spine J 2014;23:794–9. and carrying of the school bag. Spine 2007;32:E713–E717.

11 Malhotra MS, GUPTA JSEN, Sen Gupta J. Carrying of school bags by children. 43 van Gent C, Dols JJ, de Rover CM, et al. The weight of schoolbags and the occurrence

Ergonomics 1965;8:55–60. of neck, shoulder, and back pain in young adolescents. Spine 2003;28:916–21.

12 Wigram J. Why is low back pain common in adolescence? Education and Health 44 Viry P, Creveuil C, Marcelli C. Nonspecific back pain in children. A search for

2002;20:36–7. associated factors in 14-year-old schoolchildren. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 1999;66:381–8.

13 Lindstrom-Hazel D. The backpack problem is evident but the solution is less obvious. 45 Watson KD, Papageorgiou AC, Jones GT, et al. Low back pain in schoolchildren: the

Work 2009;32:329–38. role of mechanical and psychosocial factors. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:12–17.

14 Rateau MR. Use of backpacks in children and adolescents. A potential contributor of 46 Whittfield J, Legg SJ, Hedderley DI. Schoolbag weight and musculoskeletal symptoms

back pain. Orthop Nurs 2004;23:101–5. in New Zealand secondary schools. Appl Ergon 2005;36:193–8.

15 Dockrell S, Simms C, Blake C. Schoolbag weight limit: can it be defined? J Sch Health 47 Chiang HY, Jacobs K, Orsmond G. Gender-age environmental associates of middle

2013;83:368–77. school students’ low back pain. Work 2006;26:197–206.

Yamato TP, et al. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:1241–1245. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 5 of 6

Review

48 De Paula AJ, Silva JC, Paschoarelli LC, et al. Backpacks and school children’s obesity: 60 Grimmer K, Williams M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back

challenges for public health and ergonomics. Work 2012;41(Suppl 1):900–6. pain. Appl Ergon 2000;31:343–60.

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927 on 2 May 2018. Downloaded from http://bjsm.bmj.com/ on 18 July 2019 by guest. Protected by copyright.

49 Noll M, de Avelar IS, Lehnen GC, et al. Back pain prevalence and its associated factors 61 Erne C, Elfering A. Low back pain at school: unique risk deriving from unsatisfactory

in brazilian athletes from public high schools: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One grade in maths and school-type recommendation. Eur Spine J 2011;20:2126–33.

2016;11:e0150542. 62 Alghadir AH, Gabr SA, Al-Eisa ES. Mechanical factors and vitamin D deficiency in

50 Wirth B, Knecht C, Humphreys K. Spine Day 2012: spinal pain in Swiss school schoolchildren with low back pain: biochemical and cross-sectional survey analysis. J

children- epidemiology and risk factors. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:159. Pain Res 2017;10:855–65.

51 Amyra Natasha A, Ahmad Syukri A, Siti Nor Diana MK, et al. The association between 63 Spiteri K, Busuttil ML, Aquilina S, et al. Schoolbags and back pain in children between

backpack use and low back pain among pre-university students: a pilot study. J 8 and 13 years: a national study. Br J Pain 2017;11:81–6.

Taibah Univ Med Sci 2017. 64 Troussier B, Davoine P, de Gaudemaris R, et al. Back pain in school children. A study

52 Aprile I, Di Stasio E, Vincenzi MT, et al. The relationship between back pain among 1178 pupils. Scand J Rehabil Med 1994;26:143–6.

and schoolbag use: a cross-sectional study of 5,318 Italian students. Spine J 65 Noll M, Candotti CT, Rosa BN, et al. Back pain prevalence and associated factors in

2016;16:748–55. children and adolescents: an epidemiological population study. Rev Saude Publica

53 Minghelli B, Oliveira R, Nunes C. Postural habits and weight of backpacks of 2016;50:10.

Portuguese adolescents: Are they associated with scoliosis and low back pain? Work 66 Ayanniyi O, Mbada CE, Muolokwu CA. Prevalence and profile of back pain in Nigerian

2016;54:197–208. adolescents. Med Princ Pract 2011;20:368–73.

54 Poursadeghiyan M, Azrah K, Biglari H, et al. The effects of the manner of carrying the 67 Balagué F, Skovron ML, Nordin M, et al. Low back pain in schoolchildren. A study of

bags on musculoskeletal symptoms in school students in the city of Ilam, Iran. Ann familial and psychological factors. Spine 1995;20:1265–70.

Trop Med Public Health 2017;10:600–5. 68 Pires Sanchez C, Esquivel F, Felipe M, et al. Does the weight of backpacks cause

55 Adegoke BO, Odole AC, Adeyinka AA. Adolescent low back pain among secondary backache in 10-11 year-old children? Acta Pediatrica Espanola 2011;69:325–31.

school students in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 2015;15:429–37. 69 Watson KD, Papageorgiou AC, Jones GT, et al. Low back pain in schoolchildren:

56 Harreby M, Nygaard B, Jessen T, et al. Risk factors for low back pain in a cohort of occurrence and characteristics. Pain 2002;97:87–92.

1389 Danish school children: an epidemiologic study. Eur Spine J 1999;8:444–50. 70 Cardon G, Balagué F. Low back pain prevention’s effects in school children. What is

57 Haselgrove C, Straker L, Smith A, et al. Perceived school bag load, duration of carriage, the evidence? Eur Spine J 2004;13:663–79.

and method of transport to school are associated with spinal pain in adolescents: an 71 Hill JJ, Keating JL. Risk factors for the first episode of low back pain in children

observational study. Aust J Physiother 2008;54:193–200. are infrequently validated across samples and conditions: a systematic review. J

58 Astfalck RG, O’Sullivan PB, Straker LM, et al. A detailed characterisation of pain, Physiother 2010;56:237–44.

disability, physical and psychological features of a small group of adolescents with 72 Trevelyan FC, Legg SJ. Back pain in school children – where to from here? Appl Ergon

non-specific chronic low back pain. Man Ther 2010;15:240–7. 2006;37:45–54.

59 Yao W, Mai X, Luo C, et al. A cross-sectional survey of nonspecific low back pain 73 Smith D, Leggat P. Back pain in the young: a review of studies conducted among

among 2083 schoolchildren in China. Spine 2011;36:1885–90. school children and university students. Current Pediatric Reviews 2007;3:69–77.

6 of 6 Yamato TP, et al. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:1241–1245. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098927

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- School Bags and Musculoskeletal Pain Among Elementary School Children in Chennai CityDokument9 SeitenSchool Bags and Musculoskeletal Pain Among Elementary School Children in Chennai CityMuhammad HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exmpl Jurnal 2Dokument7 SeitenExmpl Jurnal 2Muhammad Imam NoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Influence of Obesity On Foot Loading Characteristics in Gait For Children Aged 1 To 12 YearsDokument12 SeitenInfluence of Obesity On Foot Loading Characteristics in Gait For Children Aged 1 To 12 Yearstania martinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10.1542@Peds.2012-0764.PDF Junal Nutrition 1Dokument9 Seiten10.1542@Peds.2012-0764.PDF Junal Nutrition 1bobkevinNoch keine Bewertungen

- pdf24 MergedDokument33 Seitenpdf24 MergedfloriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurding ObesityDokument6 SeitenJurding ObesityNancy Dalla DarsonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Evidence Based PhysiotherapyDokument10 SeitenPractical Evidence Based PhysiotherapyMarcelo WanderleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breastfeeding and Risk of Febrile Seizures in Infants The - 2019 - Brain and deDokument9 SeitenBreastfeeding and Risk of Febrile Seizures in Infants The - 2019 - Brain and deSunita ChayalNoch keine Bewertungen

- BackpainDokument10 SeitenBackpainBrenda CaraveoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bidirectional Relationships Between Weight Stigma and Pediatric Obesity A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisDokument12 SeitenBidirectional Relationships Between Weight Stigma and Pediatric Obesity A Systematic Review and Meta Analysislama4thyearNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baby Carrying Method Impacts Caregiver Postural.2Dokument7 SeitenBaby Carrying Method Impacts Caregiver Postural.2Cata Gomez UbillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Original Article: OsteoporosisDokument7 SeitenOriginal Article: OsteoporosisRio Michelle CorralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insecure Attachment in Severely Asthmatic Preschool ChildrenDokument5 SeitenInsecure Attachment in Severely Asthmatic Preschool ChildrenMatt Van VelsenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12.tummy TimeDokument27 Seiten12.tummy TimeAtikah AbayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Back Pain in The Young: A Review of Studies Conducted Among School Children and University StudentsDokument10 SeitenBack Pain in The Young: A Review of Studies Conducted Among School Children and University StudentsMariel GentilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposal 2Dokument14 SeitenResearch Proposal 2Abhishek SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Niños TaiwanesesDokument8 SeitenNiños Taiwaneseselizabeth ocanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Down Syndrome and Feeding ProblemsDokument8 SeitenDown Syndrome and Feeding Problemsfelix08121992Noch keine Bewertungen

- Changes in The Incidence of ChildhoodDokument10 SeitenChanges in The Incidence of ChildhoodAroldo CantanhedeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ExploringtheRelationshipBetweenFundamentalMotorSkillInterventionsandPhysicalActivityLevelsinChildren ASystematicReviewandMeta AnalysisDokument14 SeitenExploringtheRelationshipBetweenFundamentalMotorSkillInterventionsandPhysicalActivityLevelsinChildren ASystematicReviewandMeta AnalysisMariana MeloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsDokument9 SeitenBreast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsBernadette Grace RetubadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1841-Article Text-7334-1-10-20200703Dokument4 Seiten1841-Article Text-7334-1-10-20200703Sarly FebrianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artikel 4Dokument6 SeitenArtikel 4Claudia BuheliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identification of Malnutrition in Children With Cerebral Palsy: Poor Performance of Weight-For-Height CentilesDokument7 SeitenIdentification of Malnutrition in Children With Cerebral Palsy: Poor Performance of Weight-For-Height CentilesAfnita LestaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long-Term Outcome of Infants With Positional Occipital PlagiocephalyDokument9 SeitenLong-Term Outcome of Infants With Positional Occipital PlagiocephalychiaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Back Pain Risks Factors Brazilian AdolescentsDokument10 SeitenBack Pain Risks Factors Brazilian AdolescentsCONSTANZA PATRICIA BIANCHI ALCAINONoch keine Bewertungen

- Sleep Duration and Adolescent Obesity: AuthorsDokument9 SeitenSleep Duration and Adolescent Obesity: AuthorsmeutiasandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rebbe 2018Dokument8 SeitenRebbe 2018Karen CárcamoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Micali 2015 Adolescent Eating Disorder BehaviouDokument8 SeitenMicali 2015 Adolescent Eating Disorder BehaviouXiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sciencedirect: Sara Dokuhaki, Maryam Heidary, Marzieh AkbarzadehDokument8 SeitenSciencedirect: Sara Dokuhaki, Maryam Heidary, Marzieh AkbarzadehRatrika SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Height & Weight - Statistical AnalysisDokument7 SeitenHeight & Weight - Statistical AnalysisIvyJoyceNoch keine Bewertungen

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDokument9 SeitenNew England Journal Medicine: The offrischilia almuksiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Life Risk Factors For ObesityDokument13 SeitenEarly Life Risk Factors For Obesitybarragan-prosisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Growth and Health in Children With Moderate-to-Severe Cerebral PalsyDokument11 SeitenGrowth and Health in Children With Moderate-to-Severe Cerebral PalsyNudyan BetharinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IJMRHS VOl 3 Issue 3 With Cover Page v2Dokument272 SeitenIJMRHS VOl 3 Issue 3 With Cover Page v2Muhammad ZubairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dyw 236Dokument12 SeitenDyw 236Fatamorgana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Recommendations For Early Mobilization in Critically Ill ChildrenDokument13 SeitenPractice Recommendations For Early Mobilization in Critically Ill ChildrenClara Carte CancinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reliabilitas Pengukuran Inter Dan Intraobserver AntropometriDokument7 SeitenReliabilitas Pengukuran Inter Dan Intraobserver AntropometriRifka Laily MafazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elizathe2018 Article ACross-sectionalModelOfEatingDDokument8 SeitenElizathe2018 Article ACross-sectionalModelOfEatingDAisah indrawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assess The Effect of Nutritional Status, Food Consumption, Physical Activity Among School ChildrenDokument5 SeitenAssess The Effect of Nutritional Status, Food Consumption, Physical Activity Among School ChildrenInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kop Pen 2016Dokument6 SeitenKop Pen 2016Iwan RezkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of New WHO Child Growth Standards To Assess How Infant Malnutrition Relates To Breastfeeding and MortalityDokument11 SeitenUse of New WHO Child Growth Standards To Assess How Infant Malnutrition Relates To Breastfeeding and MortalityezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 56 29 PBDokument129 Seiten56 29 PBMarianneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boreham, C., & Riddoch, C. (2001) - The Physical Activity, Fitness and Health ofDokument17 SeitenBoreham, C., & Riddoch, C. (2001) - The Physical Activity, Fitness and Health ofAnonymous TLQn9SoRRbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hypertension, Overweight and Obesity Among School Children in Madurai, Tamil Nadu: A Cross Sectional StudyDokument9 SeitenPrevalence and Risk Factors of Hypertension, Overweight and Obesity Among School Children in Madurai, Tamil Nadu: A Cross Sectional StudyROHIT DASNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does Obesity in Uence Foot Structure in Prepubescent Children?Dokument4 SeitenDoes Obesity in Uence Foot Structure in Prepubescent Children?TyaAbdurachimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use Only: Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices Among Working-Class Women in Osun State, NigeriaDokument7 SeitenUse Only: Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices Among Working-Class Women in Osun State, Nigeriahenri kaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fix Jurnal InterDokument6 SeitenFix Jurnal InterFildzah DheaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Safety of Sedation For Overweight Obese Children in The Dental SettingDokument6 SeitenThe Safety of Sedation For Overweight Obese Children in The Dental SettingMohammed LudoNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Positive and Negative Childhood Experiences Influence Adult HealthDokument9 SeitenHow Positive and Negative Childhood Experiences Influence Adult HealthDiana Teodora PiteiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Internasional Nuzulia Rahmah 1Dokument10 SeitenJurnal Internasional Nuzulia Rahmah 1nzlNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S2095254618301078 Main PDFDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S2095254618301078 Main PDFdoni treaserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise and Sedentary Habits Among Adolescents With PCOS 2012 Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent GynecologyDokument3 SeitenExercise and Sedentary Habits Among Adolescents With PCOS 2012 Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent GynecologyfujimeisterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cremm Et Al 2011Dokument9 SeitenCremm Et Al 2011Paula MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijmrhs Vol 3 Issue 3Dokument271 SeitenIjmrhs Vol 3 Issue 3editorijmrhsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Children's Concepts of IllnessDokument21 SeitenChildren's Concepts of IllnessMarisol RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Can't Play, Won't PlayDokument7 SeitenCan't Play, Won't PlayMatthew ChilversNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ardic 19 Effects of Infant Feeding Practices and MaternalDokument7 SeitenArdic 19 Effects of Infant Feeding Practices and MaternalPaty BritoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Practical Approach to Adolescent Bone Health: A Guide for the Primary Care ProviderVon EverandA Practical Approach to Adolescent Bone Health: A Guide for the Primary Care ProviderSarah PittsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adenoids and Diseased Tonsils: Their Effect on General IntelligenceVon EverandAdenoids and Diseased Tonsils: Their Effect on General IntelligenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interventions For The Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Revision 2021Dokument61 SeitenInterventions For The Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Revision 2021Beca MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuroscience of Exercise - Neuroplasticity and Its Behavioral ConsequencesDokument3 SeitenNeuroscience of Exercise - Neuroplasticity and Its Behavioral ConsequencesTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patients As Partners in Research: It's The Right Thing To DoDokument4 SeitenPatients As Partners in Research: It's The Right Thing To DoTNoch keine Bewertungen

- PT and PTA Program Textbook SurveyDokument63 SeitenPT and PTA Program Textbook SurveyTNoch keine Bewertungen

- PT Content Outline 2018Dokument12 SeitenPT Content Outline 2018TNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Steps To Earning Awesome GradesDokument88 Seiten10 Steps To Earning Awesome GradesKamal100% (7)

- Angeles University Foundation: I) Clinical PathologyDokument20 SeitenAngeles University Foundation: I) Clinical PathologyKaye ManalastasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiac Changes Associated With Vascular Aging: Narayana Sarma V. Singam - Christopher Fine - Jerome L. FlegDokument7 SeitenCardiac Changes Associated With Vascular Aging: Narayana Sarma V. Singam - Christopher Fine - Jerome L. Flegabraham rumayaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adorio Partograph ScenarioDokument2 SeitenAdorio Partograph Scenariojonathan liboonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Isi FormulariumDokument9 SeitenDaftar Isi FormulariumNilam atika sariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthodontic Treatment in Systemic DisordersDokument9 SeitenOrthodontic Treatment in Systemic DisordersElizabeth Diaz BuenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction and Evaluation of Pharmacovigilance For BeginnersDokument8 SeitenIntroduction and Evaluation of Pharmacovigilance For BeginnersShaun MerchantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jtptunimus GDL Handayanig 5251 2 Bab2Dokument42 SeitenJtptunimus GDL Handayanig 5251 2 Bab2Rendra Syani Ulya FitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Care Bundle Approach For Prevention of Ventilator-AssociatedDokument7 SeitenA Care Bundle Approach For Prevention of Ventilator-AssociatedRestu Kusuma NingtyasNoch keine Bewertungen

- SimMan 3G BrochureDokument8 SeitenSimMan 3G BrochureDemuel Dee L. BertoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ChecklistDokument5 SeitenChecklistjoaguilarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Operating RoomDokument81 SeitenOperating Roomjaypee01100% (3)

- Clotting Concept Analysis Diagram and ExplanationDokument2 SeitenClotting Concept Analysis Diagram and ExplanationJulius Haynes100% (1)

- McqepilipsyDokument3 SeitenMcqepilipsyNguyen Anh TuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neonatal GoalsDokument5 SeitenNeonatal GoalsJehanie LukmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Extrapyramidal Side EffectsDokument15 SeitenExtrapyramidal Side EffectsNikhil YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Drugs Acting On The Cardiovascular SystemDokument5 Seiten12 Drugs Acting On The Cardiovascular SystemJAN CAMILLE LENONNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Information of SilodosinDokument8 SeitenDrug Information of SilodosinSomanath BagalakotNoch keine Bewertungen

- SodiumDokument1 SeiteSodiumyoyoyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Akshata Sawant Final Article 1Dokument16 SeitenAkshata Sawant Final Article 1SonuNoch keine Bewertungen

- COPARDokument7 SeitenCOPARMar VinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Life Support (Training Manual)Dokument74 SeitenAdvanced Life Support (Training Manual)Matt100% (25)

- XXXXXXXXXXX BGDokument5 SeitenXXXXXXXXXXX BGProbioticsAnywhereNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Opioid Presribing Rate Part DDokument104 Seiten2016 Opioid Presribing Rate Part DJennifer EmertNoch keine Bewertungen

- PTSD - Diagnostic CriteriaDokument5 SeitenPTSD - Diagnostic Criteriagreg sNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part 1 Introduction ADokument6 SeitenPart 1 Introduction AGeevee Naganag VentulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes and Hearing Loss (Pamela Parker MD)Dokument2 SeitenDiabetes and Hearing Loss (Pamela Parker MD)Sartika Rizky HapsariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Article Respiratory RelatedDokument3 SeitenResearch Article Respiratory RelatedRizza Faye BalayangNoch keine Bewertungen

- nsg-320cc Care Plan 1Dokument14 Seitennsg-320cc Care Plan 1api-509452165Noch keine Bewertungen

- Paper. Stem Cells Applications in Regenerative Medicine andDokument25 SeitenPaper. Stem Cells Applications in Regenerative Medicine andMike NundweNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample of Essay - The FluDokument2 SeitenSample of Essay - The FluMerisa WahyuningtiyasNoch keine Bewertungen