Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kwong Sing Vs City of Manila

Hochgeladen von

Elle Mich0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

8 Ansichten2 Seitensales cases

Originaltitel

Kwong Sing vs City of Manila

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldensales cases

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

8 Ansichten2 SeitenKwong Sing Vs City of Manila

Hochgeladen von

Elle Michsales cases

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 2

Republic of the Philippines SEC. 2.

No person shall take away any cloths or clothes delivered to a

SUPREME COURT person, firm, or corporation, mentioned in the preceding section, to be

Manila washed, dyed or cleaned, unless he returns the receipt issued by such

EN BANC person, firm, or corporation.

G.R. No. L-15972 October 11, 1920 SEC. 3. Violation of any of the provisions of this ordinance shall be

KWONG SING, in his own behalf and in behalf of all others having punished by a fine of not exceeding twenty pesos.

a common or general interest in the subject-matter of this action, SEC. 4. This Ordinance shall take effect on its approval.

plaintiff-appellant, Approved February 25, 1919.

vs. In the lower court, the prayer of the complaint was for a preliminary

THE CITY OF MANILA, defendant-appellant. injunction, afterwards to be made permanent, prohibiting the city of

G. E. Campbell for appellant. Manila from enforcing Ordinance No. 532, and for a declaration by the

City Fiscal Diaz for appellee. court that the said ordinance was null and void. The preliminary

injunction was granted. But the permanent injunction was not granted

MALCOLM, J.: for, after the trial, judgment was, that the petitioner take nothing by his

The validity of Ordinance No. 532 of the city of Manila requiring receipts action, without special finding as to costs. From this judgment plaintiff

in duplicate in English and Spanish duly signed showing the kind and has appealed, assigning two errors as having been committed by the

number of articles delivered by laundries and dyeing and cleaning trial court, both intended to demonstrate that Ordinance No. 532 is

establishments, must be decided on this appeal. The ordinance in invalid.

question reads as follows: The government of the city of Manila possesses the power to enact

[ORDINANCE No. 532.] Ordinance No. 532. Section 2444, paragraphs (l) and (ee) of the

AN ORDINANCE REGULATING THE DELIVERY AND RETURN OF Administrative Code, as amended by Act No. 2744, section 8,

CLOTHES OR CLOTHS DELIVERED TO BE WASHED IN authorizes the municipal board of the city of Manila, with the approval

LAUNDRIES, DYEING AND CLEANING ESTABLISHMENTS. of the mayor of the city:

Be it ordained by the Municipal Board of the city of Manila, that: (l) To regulate and fix the amount of the license fees for the

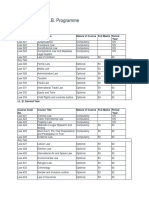

SECTION. 1. Every person, firm or corporation in the city of Manila following: . . . laundries . . .

engaged in laundering, dyeing, or cleaning by any process, cloths or (ee) To enact all ordinances it may deem necessary and proper for the

clothes for compensation, shall issue dyed, or cleaned are received a sanitation and safety, the furtherance of the prosperity, and the

receipt in duplicate, in English and Spanish, duly signed, showing the promotion of the morality, peace, good order, comfort, convenience,

kind and number of articles delivered, and the duplicate copy of the and general welfare of the city and its inhabitants, and such others as

receipt shall be kept by the owner of the establishment or person may be necessary to carry into effect and discharge the powers and

duties conferred by this chapter. . . .

The word "regulate," as used in subsection (l), section 2444 of the

Administrative Code, means and includes the power to control, to

govern, and to restrain; but "regulate" should not be construed as

synonymous with "supress" or "prohibit." Consequently, under the

power to regulate laundries, the municipal authorities could make

proper police regulations as to the mode in which the employment or

business shall be exercised. And, under the general welfare clause

(subsection [ee], section 2444 of the Manila Charter), the business of

laundries and dyeing and cleaning establishments could be regulated,

as this term is above construed, by an ordinance in the interest of the

public health, safety, morals, peace good order, comfort, convenience,

prosperity, and the general welfare.

The purpose of the municipal authorities in adopting the ordinance is

fairly evident. Ordinance No. 532 was enacted, it is said, to avoid

disputes between laundrymen and their patrons and to protect

customers of laundries who are not able to decipher Chinese

characters from being defrauded. The object of the ordinance was,

accordingly, the promotion of peace and good order and the prevention

of fraud, deceit, cheating, and imposition. The convenience of the

issuing same. This receipt shall be substantially of the following form: public would also presumably be served in a community where there is

a Babel of tongues by having receipts made out in the two official

languages. Reasonable restraints of a lawful business for such

purposes are permissible under the police power. The legislative body

is the best judge of whether or not the means adopted are adequate to

accomplish the ends in view.

Chinese laundrymen are here the protestants. Their rights, however,

are not less because they may be Chinese aliens. The life, liberty, or

property of these persons cannot be taken without due process of law;

they are entitled to the equal protection of the laws without regard to

their race; and treaty rights, as effectuated between the United States

and China, must be accorded them. 1awph!l.net

With these premises conceded, appellant's claim is, that Ordinance No.

532 savors of class legislation; that it unjustly discriminates between

persons in similar circumstances; and that it constitutes an arbitrary

infringement of property rights. To an extent, the evidence for the

plaintiffs substantial their claims. There are, in the city of Manila, more

than forty Chinese laundries (fifty-two, according to the Collector of

Internal Revenue.) The laundrymen and employees in Chinese

laundries do not, as a rule, speak, read, and write English or Spanish.

Some of them are, however, able to write and read numbers.

Plaintiff's contention is also that the ordinance is invalid, because it is

arbitrary, unreasonable, and not justified under the police power of the

city. It is, of course, a familiar legal principle that an ordinance must be

Provided, however, That in case the articles to be delivered are so reasonable. Not only must it appear that the interest of the public

many that it will take much time to classify them, the owner of the generally require an interference with private rights, but the means

establishment, through the consent of the person delivering them, may adopted must be reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of the

be excused from specifying in the receipt the kinds of such articles, but purpose and not unduly oppressive upon individuals. If the ordinance

he shall state therein only the total number of the articles so received. appears to the judicial mind to be partial or oppressive, it must be

declared invalid. The presumption is, however, that the municipal

authorities, in enacting the ordinance, did so with a rational and

conscientious regard for the rights of the individual and of the

community.

Up to this point, propositions and facts have been stated which are

hardly debatable. The trouble comes in the application of well-known

legal rules to individual cases.

Our view, after most thoughtful consideration, is, that the ordinance

invades no fundamental right, and impairs no personal privilege. Under

the guise of police regulation, an attempt is not made to violate personal

property rights. The ordinance is neither discriminatory nor

unreasonable in its operation. It applies to all public laundries without

distinction, whether they belong to Americans, Filipinos, Chinese, or

any other nationality. All, without exception, and each everyone of them

without distinction, must comply with the ordinance. There is no

privilege, no discrimination, no distinction. Equally and uniformly the

ordinance applies to all engaged in the laundry business, and, as nearly

as may be, the same burdens are cast upon them.

The oppressiveness of the ordinance may have been somewhat

exaggerated. The printing of the laundry receipts need not be

expensive. The names of the several kinds of clothing may be printed

in English and Spanish with the equivalent in Chinese below. With such

knowledge of English and Spanish as laundrymen and their employees

now possess, and, certainly, at least one person in every Chinese

laundry must have a vocabulary of a few words, and with ability to read

and write arabic numbers, no great difficulty should be experienced,

especially after some practice, in preparing the receipts required by

Ordinance No. 532. It may be conceded that an additional burden will

be imposed on the business and occupation affected by the ordinance.

Yet, even if private rights of person or property are subjected to

restraint, and even if loss will result to individuals from the enforcement

of the ordinance, this is not sufficient ground for failing to uphold the

hands of the legislative body. The very foundation of the police power

is the control of private interests for the public welfare.

Numerous authorities are brought to our attention. Many of these cases

concern laundries and find their origin in the State of California. We

have examined them all and find none which impel us to hold

Ordinance No. 532 invalid. Not here, as in the leading decision of the

United States Supreme Court, which had the effect of nullifying an

ordinance of the City and Country of San Francisco, California, can

there be any expectation that the ordinance will be administered by

public authority "with an evil eye and an unequal hand." (Yick Wo vs.

Hopkins [1886], 118 U. S., 356, which compare with Barbier vs.

Connolly [1884], 113 U. S., 27.)

There is no analogy between the instant case and the former one of

Young vs. Rafferty [1916], 33 Phil., 556). The holding there was that

the Internal Revenue Law did not empower the Collector of Internal

Revenue to designate the language in which the entries in books shall

be made by merchants, subject to the percentage tax. In the course of

the decision, the following remark was interpolated: "In reaching this

conclusion, we have carefully avoided using any language which would

indicate our views upon the plaintiffs' second proposition to the effect

that if the regulation were an Act of the Legislature itself, it would be

invalid as being in conflict with the paramount law of the land and

treaties regulating certain relations with foreigners." There, the action

was taken by means of administrative regulation; here, by legislative

enactment. There, governmental convenience was the aim; here, the

public welfare. We are convinced that the same justices who

participated in the decision in Young vs. Rafferty [supra] would now

agree with the conclusion toward which we are tending.

Our holding is, that the government of the city of Manila had the power

to enact Ordinance No. 532 and that as said ordinance is found not to

be oppressive, nor unequal, nor unjust, it is valid. This statement

disposes of both assignments of error, for the improprietry of the

question answered by a witness for the defense over the objection of

plaintiff's attorney can be conceded without affecting the result.

After the case was submitted to this court, counsel for appellants asked

that a preliminary injunction issue, restraining the defendant or any of

its officers from enforcing Ordinance No. 532, pending decisions. It was

perfectly proper for the trial and appellate courts to determine the

validity of the municipal ordinance on a complaint for an injunction,

since it was very apparent that irreparable injury was impending, that a

municipality of suits was threatened, and that complainants had no

other plain, speedy, and adequate remedy. But finding that the

ordinance is valid, the general rule to the effect that an injunction will

not be granted to restrain a criminal prosecution should be followed.

Judgment is affirmed, and the petition for a preliminary injunction is

denied, with costs against the appellants. So ordered.

Mapa, C.J., Johnson, Araullo, Avanceña and Villamor, JJ., concur.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Federal Rules of Civil Procedure: Hyperlinked, #2Von EverandFederal Rules of Civil Procedure: Hyperlinked, #2Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Criminal Complaint State of Wisconsin v. Armor Correctional Health Services, Inc.Dokument11 SeitenCriminal Complaint State of Wisconsin v. Armor Correctional Health Services, Inc.CHRISTINA CURRIENoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)Dokument14 SeitenCase Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)MirafelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solicitor General Jose C. Calida v. Hon. Antonio Trillanes IVDokument2 SeitenSolicitor General Jose C. Calida v. Hon. Antonio Trillanes IVErvin John ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Due Process, Equal Protection CasesDokument12 SeitenDue Process, Equal Protection CasessheldoncooperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fortenberry - Disqualify AUSA Mack JenkinsDokument11 SeitenFortenberry - Disqualify AUSA Mack JenkinsThe FederalistNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bryan Kohberger: Order Denying Motion To Dismiss IndictmentDokument13 SeitenBryan Kohberger: Order Denying Motion To Dismiss IndictmentLeigh EganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dela Cruz Vs ParasDokument16 SeitenDela Cruz Vs ParasborgyambuloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Substantive Due ProcessDokument28 SeitenSubstantive Due ProcessJemMoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gansul Arrival NoticeDokument19 SeitenGansul Arrival Noticejaguar99100% (5)

- Stockholm SyndromeDokument19 SeitenStockholm Syndromesisdrak100% (2)

- Tatel vs. Municipality of ViracDokument5 SeitenTatel vs. Municipality of ViracDan Christian PerolinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of John Joseph DiPaoloDokument44 SeitenAffidavit of John Joseph DiPaoloforbesadminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judicial Affidavit NeighborDokument6 SeitenJudicial Affidavit NeighborAries De Luna100% (1)

- Inherent Powers Consti 2 DJL DigestsDokument36 SeitenInherent Powers Consti 2 DJL DigestsEunice Maye Ruiz100% (1)

- Kwong Sing vs. City of Manila (41 Phil 103 G.R. No. 15972 11 Oct 1920)Dokument2 SeitenKwong Sing vs. City of Manila (41 Phil 103 G.R. No. 15972 11 Oct 1920)Kath PostreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ortigas vs. FeatiDokument17 SeitenOrtigas vs. FeatiGuiller C. MagsumbolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pub CorpDokument184 SeitenPub CorpJCapskyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pub Corp Review II Case DigestDokument137 SeitenPub Corp Review II Case DigestMikMik UyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital PunishmentDokument23 SeitenCapital PunishmentVivek Rai100% (4)

- White Light Corp Vs City of Manila (Updated Digest)Dokument3 SeitenWhite Light Corp Vs City of Manila (Updated Digest)GR100% (9)

- 61 Tatel Vs Mun of ViracDokument3 Seiten61 Tatel Vs Mun of ViracSan Vicente Mps IlocossurppoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kwong Sing vs. City of Manila 41 Phil 103Dokument2 SeitenKwong Sing vs. City of Manila 41 Phil 103Georgette V. SalinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- BA Finance Corp. v. CADokument2 SeitenBA Finance Corp. v. CAElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang vs. Williams: Estsuprema LexDokument20 SeitenCalalang vs. Williams: Estsuprema LexNicole SantoallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nicanor Malcaba, Et Al, Petitioners - Versus - Prohealth Pharma PHILIPPINES, INC., RespondentsDokument5 SeitenNicanor Malcaba, Et Al, Petitioners - Versus - Prohealth Pharma PHILIPPINES, INC., RespondentsJustin Enriquez100% (1)

- Homeowners' Association of The Philippines, Inc. and Vicente A. Rufino v. The Municipal Board of The City of Manila Et Al. (KATRINA)Dokument1 SeiteHomeowners' Association of The Philippines, Inc. and Vicente A. Rufino v. The Municipal Board of The City of Manila Et Al. (KATRINA)Carissa CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)Dokument33 SeitenCase Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)MirafelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kwong Sing V City of ManilaDokument2 SeitenKwong Sing V City of ManilaValerie Aileen AnceroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kwong Sing Vs City of ManilaDokument5 SeitenKwong Sing Vs City of ManilashezeharadeyahoocomNoch keine Bewertungen

- G. E. Campbell For Appellant. City Fiscal Diaz For AppelleeDokument40 SeitenG. E. Campbell For Appellant. City Fiscal Diaz For AppelleeJas FherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case LawDokument4 SeitenCase LawBiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cons. Dig. 3Dokument19 SeitenCons. Dig. 3Incess CessNoch keine Bewertungen

- KWONG SING V CITY OF MANILA (Digest)Dokument2 SeitenKWONG SING V CITY OF MANILA (Digest)Jude ChicanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kwong Sing vs. City of ManilaDokument3 SeitenKwong Sing vs. City of ManilaNei BacayNoch keine Bewertungen

- (GR No L-15972) Kwong Sing v. City of ManilaDokument9 Seiten(GR No L-15972) Kwong Sing v. City of ManilacreamyfrappeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loc Gov DigestDokument34 SeitenLoc Gov DigestjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loc Gov DigestDokument37 SeitenLoc Gov DigestjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loc Gov DigestDokument28 SeitenLoc Gov DigestjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loc Gov DigestDokument19 SeitenLoc Gov DigestjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tatel v. Municipality of ViracDokument3 SeitenTatel v. Municipality of ViracLyka Dennese SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vicente de La Cruz vs. Paras DigestDokument3 SeitenVicente de La Cruz vs. Paras DigestEvangeline VillajuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippine Congress AssembledDokument32 SeitenBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippine Congress AssembledHannaniah PabicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)Dokument35 SeitenCase Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)MirafelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)Dokument18 SeitenCase Digests For Constitutional Law 2 Review 2020: (List of Cases Based On Dean Joan S Largo'S Syllabus)MirafelNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd Half FP of StateDokument20 Seiten2nd Half FP of StateEly SibayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ortigas & Co. Ltd. Partnership vs. Feati Bank & Trust Co. (G.R. No. L-24670, December 14, 1979)Dokument17 SeitenOrtigas & Co. Ltd. Partnership vs. Feati Bank & Trust Co. (G.R. No. L-24670, December 14, 1979)Elle AlamoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petitioners: en BancDokument10 SeitenPetitioners: en BancVina Esther FiguraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 8 - Due Process of Law - DigestsDokument14 SeitenChap 8 - Due Process of Law - DigestsTrish Verzosa100% (1)

- Ortigas Vs Feati BankDokument25 SeitenOrtigas Vs Feati BankMaria GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 - Tatel vs. Municipality of Virac, G.R. No. 40243 March 11, 1992Dokument7 Seiten3 - Tatel vs. Municipality of Virac, G.R. No. 40243 March 11, 1992Dennis Arn B. CariñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 5 - StatconDokument4 SeitenCHAPTER 5 - StatconggumapacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ortigas v. FeatiDokument25 SeitenOrtigas v. FeatiellochocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section 10 13Dokument46 SeitenSection 10 13Althea EstrellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- R A - No - 10142-FRIADokument22 SeitenR A - No - 10142-FRIAriclyde cahucomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pacta Sunt ServandaDokument4 SeitenPacta Sunt ServandaBrigetLim100% (1)

- Ermita Hotel v. City of ManilaDokument1 SeiteErmita Hotel v. City of ManilaRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDokument26 SeitenBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledYuri SisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eminent Domain Consti 2Dokument3 SeitenEminent Domain Consti 2LC TNoch keine Bewertungen

- Custom As A Source of LawDokument16 SeitenCustom As A Source of LawshayneyyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Congress of The Philippines Metro Manila Fourteenth Congress Third Regular SessionDokument37 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Congress of The Philippines Metro Manila Fourteenth Congress Third Regular SessionCiara De LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- A. in The Matter of The Petitions For Admission To The Bar of Unsuccessful Candidates of 1946 To 1953 - ALBINO CUNANANDokument91 SeitenA. in The Matter of The Petitions For Admission To The Bar of Unsuccessful Candidates of 1946 To 1953 - ALBINO CUNANANmichelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- in Re Cunanan Et Al. 94 Phil 534 March 18 1954Dokument98 Seitenin Re Cunanan Et Al. 94 Phil 534 March 18 1954April Janshen MatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fernando V St. SchoDokument16 SeitenFernando V St. SchoCla SaguilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fria Law (Ra10142)Dokument41 SeitenFria Law (Ra10142)Derek C. EgallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDokument24 SeitenBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledracrabeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fria Ra 10142Dokument23 SeitenFria Ra 10142Marianne Shen PetillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Re Albino CunananDokument98 SeitenIn Re Albino CunananFerb de JesusNoch keine Bewertungen

- White Light Corp. v. City of Manila, G.R. No. 122846, 20 January 2009Dokument12 SeitenWhite Light Corp. v. City of Manila, G.R. No. 122846, 20 January 2009vince parisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tatel v. Municipality of Virac, G.R. No. 40243, (March 11, 1992)Dokument6 SeitenTatel v. Municipality of Virac, G.R. No. 40243, (March 11, 1992)Hershey Delos SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ferrer Vs BautistaDokument29 SeitenFerrer Vs BautistaElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yang v. CADokument3 SeitenYang v. CAElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Garcia Vs Ranida SalvadorDokument5 SeitenGarcia Vs Ranida SalvadorElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Umali VS Dr. CruzDokument12 SeitenUmali VS Dr. CruzGhifari MustaphaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corinthian Gardens Vs Sps. ReynaldoDokument6 SeitenCorinthian Gardens Vs Sps. ReynaldoElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- de Ocampo v. GatchalianDokument3 Seitende Ocampo v. GatchalianElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Health Care v. CIR, G.R. No. 167330, June 12, 2008Dokument7 SeitenPhilippine Health Care v. CIR, G.R. No. 167330, June 12, 2008Elle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guingon v. Del Monte, 20 SCRA 1043 (1967)Dokument4 SeitenGuingon v. Del Monte, 20 SCRA 1043 (1967)KristineSherikaChyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIR Vs AlgueDokument3 SeitenCIR Vs AlgueElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alpha v. Castor G.R. No. 198174, Sep. 2, 2013Dokument6 SeitenAlpha v. Castor G.R. No. 198174, Sep. 2, 2013Elle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 (1) White Gold Vs PioneerDokument3 Seiten1 (1) White Gold Vs PioneerJovan Ace Kevin DagantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caballero v. DeiparineDokument3 SeitenCaballero v. DeiparineElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Baguio Vs de LeonDokument4 SeitenCity of Baguio Vs de LeonElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Health Care v. CIR, G.R. No. 167330, September 18, 2009Dokument15 SeitenPhilippine Health Care v. CIR, G.R. No. 167330, September 18, 2009Elle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNB v. Sta. MariaDokument2 SeitenPNB v. Sta. MariaElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- NFA v. IACDokument1 SeiteNFA v. IACElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philamcare Health Systems, Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Julita TrinosDokument4 SeitenPhilamcare Health Systems, Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Julita TrinosClaudine Christine A VicenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNB v. Agudelo y GonzagaDokument2 SeitenPNB v. Agudelo y GonzagaElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial Bank v. Republic Armored CarDokument1 SeiteCommercial Bank v. Republic Armored CarElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rural Bank of Bombon, Inc. v. CADokument2 SeitenRural Bank of Bombon, Inc. v. CAElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dir. of Public Works v. Sing JucoDokument2 SeitenDir. of Public Works v. Sing JucoElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phil. Sugar Estates Dev. Co. v. PoizatDokument3 SeitenPhil. Sugar Estates Dev. Co. v. PoizatElle Mich100% (1)

- Awad v. Filma Mercantile Co.Dokument1 SeiteAwad v. Filma Mercantile Co.Elle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- EN BANC G.R. No. L-13471 January 12, 1920 VICENTE SY-JUCO and CIPRIANA VIARDO, Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. SANTIAGO V. SY-JUCO, Defendant-AppellantDokument1 SeiteEN BANC G.R. No. L-13471 January 12, 1920 VICENTE SY-JUCO and CIPRIANA VIARDO, Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. SANTIAGO V. SY-JUCO, Defendant-AppellantElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rural Bank of Bombon, Inc. v. CADokument2 SeitenRural Bank of Bombon, Inc. v. CAElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Municipal Court of Iloilo v. EvangelistaDokument2 SeitenMunicipal Court of Iloilo v. EvangelistaElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phil. Sugar Estates Dev. Co. v. PoizatDokument3 SeitenPhil. Sugar Estates Dev. Co. v. PoizatElle Mich100% (1)

- Dir. of Public Works v. Sing JucoDokument2 SeitenDir. of Public Works v. Sing JucoElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caballero v. DeiparineDokument3 SeitenCaballero v. DeiparineElle MichNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 163938 March 28, 2008 Dante Buebos and Sarmelito Buebos, Petitioners, The People of The Philippines, RespondentDokument10 SeitenG.R. No. 163938 March 28, 2008 Dante Buebos and Sarmelito Buebos, Petitioners, The People of The Philippines, RespondentjojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CraigslistVRadpad - JudgmentDokument9 SeitenCraigslistVRadpad - JudgmentLegal WriterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solvic Industrial Corp. v. NLRC GR 125548, September 25, 1998Dokument1 SeiteSolvic Industrial Corp. v. NLRC GR 125548, September 25, 1998Bion Henrik PrioloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compendium RemedialDokument663 SeitenCompendium RemedialAthena RoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRLAW OUTLINE (March 4, 2019)Dokument32 SeitenHRLAW OUTLINE (March 4, 2019)RegieReyAgustinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elavarasan v. State - IracDokument6 SeitenElavarasan v. State - Iracaakash batraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Relations and Torts & Damages1Dokument8 SeitenHuman Relations and Torts & Damages1girlNoch keine Bewertungen

- James Griffin v. State of South Carolina Martha Wannamaker, Warden Attorney General of South Carolina, 958 F.2d 367, 4th Cir. (1992)Dokument2 SeitenJames Griffin v. State of South Carolina Martha Wannamaker, Warden Attorney General of South Carolina, 958 F.2d 367, 4th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casebook - Chapter 1Dokument21 SeitenCasebook - Chapter 1DrB PKNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Make A Batson Case On AppealDokument50 SeitenHow To Make A Batson Case On Appealfirdaus azinunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paulding Progress November 18, 2015Dokument16 SeitenPaulding Progress November 18, 2015PauldingProgressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marvin Mitchell vs. Niagara Regional PoliceDokument12 SeitenMarvin Mitchell vs. Niagara Regional PoliceGrant LaFlecheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comment-Dreu CaseDokument4 SeitenComment-Dreu CaseRosemarie JanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law Curriculum in Tu (Nepal Law Campus)Dokument2 SeitenLaw Curriculum in Tu (Nepal Law Campus)Shrestha AnjivNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jennings Rule Legal OpinionDokument3 SeitenJennings Rule Legal Opinional_crespoNoch keine Bewertungen

- BarbadosEvidence Act CAP1211 PDFDokument124 SeitenBarbadosEvidence Act CAP1211 PDFCarolyn TeminNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Mosqueda-Ramirez, 10th Cir. (2005)Dokument10 SeitenUnited States v. Mosqueda-Ramirez, 10th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- "When All Hope Seems Lost Today, Give Up Tomorrow." The Quote Depicts The Unfortunate Ruling ofDokument3 Seiten"When All Hope Seems Lost Today, Give Up Tomorrow." The Quote Depicts The Unfortunate Ruling ofrussel1435Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rahiem Nowell v. John Reilly, 3rd Cir. (2011)Dokument9 SeitenRahiem Nowell v. John Reilly, 3rd Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Google, Inc. v. Affinity Engines, Inc. - Document No. 73Dokument2 SeitenGoogle, Inc. v. Affinity Engines, Inc. - Document No. 73Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen