Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Clinical Assessment and Treatment in Paediatric Wards in The North-East of The United Republic of Tanzania

Hochgeladen von

Oheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Clinical Assessment and Treatment in Paediatric Wards in The North-East of The United Republic of Tanzania

Hochgeladen von

Oheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Clinical assessment and treatment in paediatric wards in the

north-east of the United Republic of Tanzania

Hugh Reyburn,a Emmanuel Mwakasungula,b Semkini Chonya,b Frank Mtei,b Ib Bygbjerg,c Anja Poulsen c

& Raimos Olomi b

Objective We assessed paediatric care in the 13 public hospitals in the north-east of the United Republic of Tanzania to determine if

diagnoses and treatments were consistent with current guidelines for care.

Methods Data were collected over a five-day period in each site where paediatric outpatient consultations were observed, and a

record of care was extracted from the case notes of children on the paediatric ward. Additional data were collected from inspection of

ward supplies and hospital reports.

Findings Of 1181 outpatient consultations, basic clinical signs were often not checked; e.g. of 895 children with a history of fever,

temperature was measured in 57%, and of 657 of children with cough or dyspnoea only 57 (9%) were examined for respiratory

rate.

Among 509 inpatients weight was recorded in the case notes in 250 (49%), respiratory rate in 54 (11%) and mental state in

47 (9%). Of 206 malaria diagnoses, 123 (60%) were with a negative or absent slide result, and of these 44 (36%) were treated

with quinine only. Malnutrition was diagnosed in 1% of children admitted while recalculation of nutritional Z-scores suggested that

between 5% and 10% had severe acute malnutrition; appropriate feeds were not present in any of the hospitals. A diagnosis of HIV-

AIDS was made in only two cases while approximately 5% children admitted were expected to be infected with HIV in this area.

Conclusion Clinical assessment of children admitted to paediatric wards is disturbingly poor and associated with missed diagnoses

and inappropriate treatments. Improved assessment and records are essential to initiate change, but achieving this will be a challenging

task.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2008;86:132–139.

Une traduction en français de ce résumé figure à la fin de l’article. Al final del artículo se facilita una traducción al español. .الرتجمة العربية لهذه الخالصة يف نهاية النص الكامل لهذه املقالة

Introduction lines for care. In the United Republic Methods

of Tanzania, the Referral Care Manual

Hospital care for severely ill children (RCM) based on Integrated Manage- The study area

can make an important contribution ment of Childhood Illness (IMCI) was The north-east of the United Republic

to child survival, especially in Africa adopted as policy in 2005.7 Although of Tanzania is characterized by the

where typically one in six children dies Eastern Arc mountains stretching from

not widely implemented, this defines

before their fifth birthday from treatable

a framework within which current the coastal plain to Mount Kilimanjaro.

conditions such as malaria, pneumo-

standards of care can be evaluated and Populations living at an altitude of up

nia, gastroenteritis and malnutrition.1,2

improved. to 2000 m create a wide natural variation

Good-quality inpatient care in a rural

district in Kenya has been estimated to In this study, we aimed to deter- in malaria transmission intensity.8 There

have averted up to 60% of childhood mine if clinical assessments of children are two administrative regions with a

deaths in the surrounding population,3 admitted to hospital were sufficient to combined population of 3.4 million,9

although this potential is probably not make effective use of the RCM and if 90% of whom live in rural areas where

realized in many areas of Africa due to treatment of common conditions was subsistence agriculture is supplemented

lack of trained staff and other resources, consistent with the RCM. The study by plantations of sisal, bananas and

few and unreliable diagnostic tests and was conducted in 13 hospitals in the coffee.

poor organization of care.4–6 north-east of the United Republic of Childhood mortality in 2002 was

The limited diagnostic and treat- Tanzania as part of a baseline assessment estimated at 67 out of 1000 and 162 out

ment options available in most district before implementing a three-year ca- of 1000 in the Kilimanjaro and Tanga

hospitals have led in recent years to the pacity-building programme to improve regions respectively;9 a difference that

development of syndromic-based guide- paediatric inpatient care in the area. follows known differences in malaria

a

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London WCIE 7HT, England.

b

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, United Republic of Tanzania.

c

University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Correspondence to Hugh Reyburn (e-mail: hugh.reyburn@lshtm.ac.uk).

doi:10.2471/BLT.07.041723

(Submitted: 26 February 2007 – Revised version received: 7 June 2007 – Accepted: 13 June 2007 )

132 Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2)

Research

Hugh Reyburn et al. Clinical assessment and treatment in Tanzanian paediatric wards

transmission intensity and socioeco- The data are descriptive, but for illustra- Malnutrition, meningitis and HIV-

nomic status in the regions. In the year tive purposes we estimated that within related disease were associated with

before the start of the study, an IMCI any single site data from 50 admissions the highest case fatality rates although

“focal person” had been trained in each would allow an estimate of any propor- these conditions were reported in only

hospital in the regions, but IMCI was tion of 25% ± 10% with 80% power 0.4%, 0.2% and 0.1% of admissions

not systematically practised at any site. and 90% confidence. Nutritional data respectively (Table 1). Almost 40% of

were analysed using United States of admissions were infants and only 8%

Background and retrospective data America Centers for Disease Control were over five years of age. The median

Thirteen hospitals were assessed; two reference data for height, weight and duration of non-fatal admission was 3

were regional, seven were government age. days while that of fatal admissions was

district and four were mission “district- on the day of admission.

designated” hospitals. Hospital ecolo- Ethical approval and consent Inspection of wards and hospital

gies varied; five were highland district Staff members were sensitized to the as- pharmacies revealed that all sites had

hospitals (> 1200 m of altitude), two sessment through meetings at each site. at least one oxygen cylinder or oxygen

were urban regional hospitals and six Staff and caretakers of children whose concentrator; these were present on the

were lowland district hospitals. Clinical consultations were observed gave ver- ward in all but one of the paediatric

paediatric care was provided by clinical bal consent to participate. If qualified wards). Quinine, amoxicillin, penicil-

officers (with 2–3 years of training) and research staff observed care that was lin, chloramphenicol and gentamycin

assistant medical officers (with an ad- likely to directly jeopardize the survival were present either on the ward or in

ditional 2 years of training), except in of a child, they made a tactful interven- the hospital pharmacy in all sites. None

three hospitals that had a fully-qualified tion by informing the most senior staff of the hospitals had specialist feeds for

medical doctor. member present of their concerns and severe acute malnutrition (ReSoMal,

Data on all paediatric admissions offering assistance. Ethical approval for F-75, F-100 or equivalent).

and deaths during 2004 were extracted this study was obtained from the Insti-

from the paediatric ward register in tutional Review Boards of the London Outpatient care

each site. The number of calendar days School of Hygiene and Tropical Medi- In the 13 hospitals, 1181 paediatric out-

between admission and discharge or cine, the United Kingdom, and the patient consultations were observed

death was calculated in approximately National Institute for Medical Research (interquartile range: 37–120). The me-

50 consecutive fatal and non-fatal ad- in the United Republic of Tanzania. dian (mean) age of children seen was

missions in each hospital to estimate 1.5 (1.9) years, the median reported

the time from admission to death or Results duration of illness was 3 days and 7

discharge respectively. (0.6%) of the children had been referred

The ward and hospital pharmacy Retrospective data and hospital from another health facility. In 95%

were inspected for the presence of es- supplies of consultations, the consulting health

sential drugs, infusions and oxygen, as In 2004, there were a total of 27 703 worker was a clinical officer and in 5%

absence of these might explain a failure admissions to the 13 hospitals (range an assistant medical officer. No consul-

to seek indications for their use. per hospital 380–4447) with 826 (3%) tations were conducted by a qualified

deaths (range: 1–6%). Malaria ac- medical doctor.

Outpatient and inpatient data counted for 55% of admissions and Clinical features that were sought

The basic methods of the assessment was the most common single cause of during consultations are shown in

used established WHO evaluation admission in all but one site, followed Table 2. In 489 (50%) consultations

tools 10 adapted for use in east Africa.5 by pneumonia (22% of admissions). an investigation was requested; 51% of

Outpatient consultations were silently

observed by a medically trained research

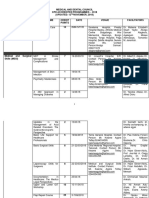

assistant who recorded whether IMCI Table 1. Paediatric admissions and deaths during 2004 at 13 Tanzanian study hospitals

diagnostic criteria were obtained either

by examination or enquiry of the care- Diagnosis a Admissions b Deaths CFR (%)

taker.11 Hospital case notes of children Malaria 15 299 (55) 367 2.4

who were present on the paediatric

Pneumonia 6 070 (22) 138 2.3

ward at the start of the five-day assess-

Anaemia 1 774 (6) 121 6.8

ment or who were admitted during the

Gastroenteritis 1 248 (5) 40 3.2

assessment were inspected by medically

Neonatal sepsis 303 (1) 21 6.9

trained research staff for the record of

Malnutrition 121 (0.4) 24 19.8

admission assessment, progress on the

Meningitis 60 (0.2) 18 30.0

ward and treatment given. Data from

HIV 28 (0.1) 8 28.6

maternity wards where neonates were

Other 2 800 (10) 89 3.2

cared for were not collected.

Total 27 703 (100) 826 3.0

Sample size and data management

CFR, case fatality rate.

Data were double-entered into Micro- a

First-recorded final diagnosis in ward admission registers.

soft Access and analysed using Stata 9. b

Percentage of total indicated in parentheses.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2) 133

Research

Clinical assessment and treatment in Tanzanian paediatric wards Hugh Reyburn et al.

these were for a malaria slide only, 32%

Table 2. Clinical features that were sought (by enquiry or examination) in outpatient

for a malaria slide and haemoglobin consultations directly observed over 5 days at 13 Tanzanian study hospitals

measurement, and 17% for other in-

vestigations. One hundred and twenty General signs and symptoms, all cases Number checked b Interquartile

five (11%) children were admitted and (n = 959) a range (%)

an additional 51 (4%) were asked to

re-attend for follow-up. An aggregated Ability to feed asked 607 (63) 49–82

score was derived from the presence Pre-treatment asked 534 (56) 45–72

(1) or absence (0) of an enquiry or Temperature felt or measured 533 (55) 24–75

examination for the following features: Vomiting asked 514 (54) 41–71

duration of illness, treatment in this ill- Eyes examined 130 (14) 7–26

ness, ability to feed asked, temperature Pallor checked 124 (13) 5–13

felt or measured, weight chart checked, Convulsion or lethargy asked 96 (10) 1–8

chest exposed, respiratory rate counted, Fever in last 7 days asked 39 (4) 0–3

convulsion in this illness asked and ex- Immunization checked 41 (4) 1–3

amined for pallor. Overall, the median Wasting or weight chart checked 31 (3) 0–7

(mean) score for these 9 items was 3 Oedema checked 9 (1) 0–1

(3.0), increasing to 4 (4.4) if the child If fever was stated to be a problem

was admitted. The assessment score (n = 805)

increased with increasing duration of Temperature felt or measured 456 (57) 27–79

consultation (mean scores of 2.4, 2.9, Convulsion or lethargy asked 87 (11) 1–15

3.4, 3.7 and 4.6 for consultations last- Ears checked 53 (7) 1–12

ing < 2 minutes, 2–3.9 minutes, 4–5.9 Fever in last 7 days asked 40 (5) 0–4

minutes, 6–7.9 minutes and > 8 min- Mastoid checked 25 (3) 0–9

utes respectively) and consultations that Stiff neck checked 7 (1) 0–5

resulted in a child being admitted lasted If cough or difficult breathing reported as

longer (median: 5 minutes) than other a problem (n = 657)

consultations (median: 3 minutes). Chest exposed c 183 (28) 23–42

Stethoscope used 115 (18) 11–29

Inpatient data Respiratory rate counted d 57 (9) 0–2

Data from 509 paediatric admissions Cyanosis checked 22 (3) 0–7

were extracted from case notes of chil- If diarrhoea reported as a problem

dren who were either on the ward at (n = 150)

the start of the assessment or who Blood in stool asked 57 (39) 22–55

were admitted during the assessment. Skin pinch checked 21 (14) 3–5

The median (mean) age was 1.6 (2.5) Diarrhoea more than 14 days asked 6 (4) 0–4

years; 9 (1.8%) children died, 7 (1.4%) Thirst checked e 7 (5) 0–18

were referred to another hospital, 333

(65.4%) were discharged and 133

a

Cases with incomplete data omitted to allow a common denominator.

b

Percentage of total indicated in parentheses.

(31.4%) were alive on the ward at the c

Chest exposed from below to nipple line and assumed to be evidence that chest in-drawing was sought.

end of the study. d

Respiratory rate counted for any time period.

A record of clinical features in the e

Thirst asked or fluids offered.

case notes irrespective of the result for

all admissions and for selected diagnoses

is shown in Table 3. The age, duration on the medical history, 10% related to Of 206 children with an admission

of illness and measurement of tempera- temperature or fever, 8% related to diagnosis of malaria and a slide request

ture were present in a high proportion new treatment and 24% to informa- recorded, 149 (72%) had the result in

of admissions, but weight, pallor or tion categories other than these. Only the case notes. Treatment with com-

the presence of a cough were recorded 4% of entries recorded findings of ex- binations of antimalarial or antibiotic

in only about half of admissions. The amination for the level of consciousness drugs by blood slide results is shown in

ability to drink or the level of conscious- or hydration, and 3% on respiratory Fig. 1; 66 (44%) children had a record

ness was recorded in less than 10% of function. of a negative malaria slide, of whom 23

admissions. (35%) were treated with an antimalarial

Of the 509 children in the study, Specific diagnoses drug alone.

310 (59%) had no entry in the case Malaria was the single most common Of 193 children with a diagnosis

notes following admission. There were diagnosis; the assessment of which of pneumonia, only 29 (15%) had a

669 entries in the 208 case notes that depends on the level of consciousness, record of respiratory rate, 11 (38%) of

had any entry after admission (exclud- presence of respiratory distress (the most which were normal for the recorded age.

ing insertion of laboratory or X-ray fatal manifestation of severe malaria) Only one patient had a complete record

results); 25% of these related to con- and the presence of severe anaemia. Yet of the respiratory rate, ability to drink,

tinuation of treatment, 17% to a remark only pallor or a malaria slide result were chest in-drawing and cyanosis (RCM

on general progress, 10% elaborated recorded in more than half the cases.12 criteria to classify pneumonia).

134 Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2)

Research

Hugh Reyburn et al. Clinical assessment and treatment in Tanzanian paediatric wards

Seven (1.4%) children were diag-

Table 3. Documentation in the case notes (irrespective of result) of clinical features

nosed with meningitis (admission or required to make inpatient assessments according to WHO guidelines for care

discharge), 6 with a record of intention

to lumbar puncture, and 4 with a result All admissions (n = 509) Number with any Interquartile

written in the case notes. One addi- record a range (%)

tional case had a lumbar puncture but

was not diagnosed with meningitis. Duration of illness 462 (91) 89–98

There were only 2 (0.4%) children Age in years or months 448 (88) 91–100

with a diagnosis (admission or dis- Fever history 436 (86) 76–90

charge) that included HIV, AIDS or Temperature 413 (81) 68–92

a variety of synonyms that are used in Pallor 291 (58) 31–81

case-notes (e.g. “elisa-test positive”, Cough or difficult breathing 258 (51) 51–70

“immunosuppression”). History of vomiting 253 (50) 44–54

An initial or final diagnosis of mal- Weight recorded 250 (49) 12–51

nutrition was made for 5 (1%) chil- Diarrhoea 173 (34) 35–46

dren; 1 had an abnormal weight for age Hydration status b 90 (18) 13–30

Z-score (WAZ) on admission, 1 was Convulsion in this illness 63 (12) 5–17

within normal limits and for 3 it was Respiratory rate 54 (11) 1–15

not possible to calculate the WAZ due Mental state c 47 (9) 0–11

to missing data on age and/or weight. Able to drink 35 (7) 0–13

To assess whether diagnoses of Oedema 29 (6) 3–11

malnutrition might have been missed, Neck stiffness 26 (5) 2–1

WAZ scores were calculated for the Heart rate 19 (4) 0–2

209 children with a record of age and Cyanosis 15 (3) 0–5

weight (with the addition of 6 months Any diagnosis of malaria d (n = 299)

if age was only given in years). Seventeen Malaria slide result 175 (58) 21–88

of these had WAZ of < –5 and were Pallor 202 (68) 54–93

excluded due to likely error. Of the Difficulty in breathing 45 (15) 4–37

remaining 192, 29 (15%) had a score Mental state 27 (9) 0–17

between –2 and –3, and 23 (12%) be- Haemoglobin result 166 (56) 17–67

tween –3 and –5, suggesting moderate Any diagnosis of pneumonia (n = 191)

and severe malnutrition respectively. Able to drink 14 (7) 0–11

A record of height or length was not Chest in-drawing 62 (32) 16–45

found in any of the case notes, so it Respiratory rate 29 (15) 5–25

was not possible to distinguish between Cyanosis 11 (6) 0–11

stunting and acute malnutrition nor

Any diagnosis of gastroenteritis (n = 103)

was not possible to estimate the con-

Fever history or temperature recorded 96 (93) 9–100

tribution of dehydration (although 11

Hyrdration status a 56 (54) 26–85

children with abnormal Z-scores had an

Mental state 8 (8) 0–11

admission diagnosis of gastroenteritis).

a

Percentage of total indicated in parentheses.

Discussion b

Any statement on the hydration status or presence/absence of sunken eyes or delayed skin pinch.

c

Any note on alertness, lethargy, Blantyre or alert-verbal response-pain response-unconscious (AVPU) scores.

Delivery of hospital care is a complex d

Diagnoses include any admission or discharge diagnosis; cases may appear in multiple categories.

process involving management and sup-

plies, staff availability and skills mix,

Africa (i.e. antimalarials, antibiotics, documented that malaria tends to be

laboratory services and so on. Some of

oxygen, fluids and blood). overdiagnosed, slide-negative children

these have been described elsewhere 4–6

and in this analysis we have focused with severe febrile illness suggestive of

on what we consider to be a funda- Specific diagnoses malaria have higher mortality than slide-

mental issue: that clinical assessments Although a record of care is not the positives 13 and many of these children

were often very superficial both in the same as the care that is delivered (and are likely to have blood-borne bacterial

outpatient department (where children there is a tendency to record only infections.14 In fact, there is evidence

are generally admitted and treatment abnormal findings), where informa- that even with a positive slide result a

is initiated) and on subsequent days tion was available it revealed problems significant proportion of children with

of admission, where few and generally with paediatric case management that severe malaria also have potentially

uninformative entries were added to are strikingly consistent with other life-threatening bacteraemia.15 The bias

the case notes. With the exception of studies.5,6,13 towards and over-confidence in a single

specialist feeds for malnutrition, our Approximately one-third of slide- diagnosis of malaria in these settings is

findings could not be explained by the negative children diagnosed as having likely to put children at risk, and this bias

absence of the few basic treatments malaria were treated with an antima- merits more specific attention in current

that are available in paediatric wards in larial only, while we have previously guidelines.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2) 135

Research

Clinical assessment and treatment in Tanzanian paediatric wards Hugh Reyburn et al.

Fig. 1. Treatments with admission diagnosis of malaria by slide result

Admission diagnosis for malaria

and slide requested:

206

No slide result in case notes: Slide result in case notes:

57 (28%) 149a (72%)

Antimalaria Antimalaria Slide positive: Slide negative:

alone: and antibiotic: 83a (56%) 66a (44%)

21 (42%) 30 (58%)

Antibiotic only: Antimalarial Antimalarial, Antibiotic only: Antimalarial Antimalarial,

1 (4%) and antibiotic: no antibiotic: 10 (15%) and antibiotic: no antibiotic:

32 (39%) 48 (58%) 33 (50%) 23 (35%)

a

Numbers restricted to admission diagnosis, therefore different from Table 3.

Respiratory rate, chest in-drawing, antiretroviral treatment that is avail- Inpatient mortality

presence of cyanosis and ability to able in many African hospitals (and Paediatric inpatient mortality in our

drink are essential criteria for diag- in at least three of our study hospitals) study hospitals was approximately half

nosing pneumonia and assessing its the issue needs to be tackled. A study that reported from Kenyan District

severity,7 but over half of the children from Malawi (where HIV prevalence is Hospitals by English et al., and prob-

with an admission diagnosis of pneu- approximately 16%, compared to 8% ably lower than in African hospitals

monia did not have one of these fac- in the United Republic of Tanzania) 19 generally. The reasons are not clear but

tors documented in the case notes and found that almost 20% of paediatric

at least two factors are likely to be im-

only one child had a record of all four admissions were HIV-positive and the

portant. First, neonates (with relatively

factors. Reduced oxygen saturation in diagnosis was often difficult to pre-

high mortality) are managed on the

children with pneumonia is associated dict clinically.20 In the assessment of

maternity ward and are not counted

with a significant increase in mortal- one of the hospitals we subsequently

as admissions or deaths, neither in our

ity, although the difficulties in clini- found that 4% of febrile paediatric

study nor in routine hospital statistics,

cally detecting cyanosis may provide admissions with a history of fever were

some justification for its being rarely antibody-test positive for HIV, rising a problem that also applies to Kenyan

recorded.16 to 15% if the malaria slide was negative routine statistics. Second, in the United

Other studies in east Africa suggest with criteria of pneumonia or malnu- Republic of Tanzania paediatric in-

that approximately 2% of paediatric trition (Nadjm B et al., unpublished). patient care is generally free, while in

admissions and up to 10% of deaths Malnutrition has been implicated as Kenya and many other African coun-

are due to meningitis, often presenting a contributing cause in up to half of tries there are significant user fees that

with atypical features. Careful applica- all childhood deaths in resource-poor are likely to restrict admission to more

tion of guidelines for lumbar punctures countries,2 and a hospital series in Kenya severely ill children. Consistent with

is likely to result in approximately one (a country with similar child mortality this, a study of admissions with WHO

in five paediatric admissions needing a to the United Republic of Tanzania) 21 criteria for severe malaria, in one of the

lumbar puncture,15,17,18 but we found found that almost 10% of paediatric hospitals in our study, found case fatal-

that it was very rarely undertaken. This admissions (and 38% of deaths) had ity to be comparable to that found in

is likely to result in significant numbers severe acute malnutrition, compared to Africa generally.22 Variations in inpa-

of children with acute meningitis being less than 1% diagnosed in our study.15 tient mortality raise several questions

treated inappropriately, typically for Specialist feeds and modern guidelines regarding quality of care, access and

cerebral malaria. were absent in all of our study hospitals, appropriate criteria for admission, about

HIV testing in children is a sen- and subsequent enquiry revealed that which relatively little is known. Inad-

sitive issue, not least because a posi- these were not available nationally, a equate outpatient assessments inevita-

tive test almost inevitably means the situation that is now being urgently bly lead to both a failure to recognize

mother is infected. However, now that redressed by the Ministry of Health. the need for admission and unnecessary

136 Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2)

Research

Hugh Reyburn et al. Clinical assessment and treatment in Tanzanian paediatric wards

admission that is likely to compromise as long as the median consultation time Acknowledgements

the care of severely ill children on the that we observed. Little is known about Thanks to all the staff of participat-

ward. staff productivity in these settings; while ing hospitals who cooperated with

it seems likely that in busy hospitals the this study. Regional and district medi-

Improving quality of care availability of staff may limit what can cal officers of Tanga and Kilimanjaro

Improving hospital care is a complex be achieved, in many and perhaps most provided support and guidance in

and multidimensional task.23 Tanzanian hospitals improved time-management conducting the study. The data were

Ministry of Health policy 24 emphasizes and working practices may be the key. collected by a team from the Joint

the importance of multidisciplinary There is now consistent evidence Malaria Programme: Hilda Mbakilwa,

teams undertaking regular clinical audit, of disturbingly low standards of pae- Lilian Ngowi, Ana Mtei, Boniface Njau,

but establishing a meaningful audit diatric inpatient care in Africa, a situ- Magdalena Massawe and Zenorina

cycle is almost impossible without es- ation that is unacceptable in an era of Mushi. Joanne Beckmann assisted in

sential clinical information. The RCM international focus on child survival. three sites. Thanks to Mike English,

and the recently introduced Pocket Our findings suggest that seeking and who provided advice and guidance in

Book lend themselves well to the use of recording essential clinical features in designing the study, and Jackie Deen

a standard admission form to help fill sick children needs to be the focus for for comments on the manuscript. Most

this relative vacuum of useful clinical both improved individual case manage- of all, thanks to the caretakers and their

information, and following this study ment and for effective clinical audit to children who participated. The work

we developed and introduced such a raise standards generally. This will be a was supported by a grant from the

form. However, it has been estimated complex and challenging task, but is European Commission.

that an IMCI assessment, even at the essential if inpatient paediatric care is to

first level of care, takes approximately realize its potential to reduce childhood Competing interests: None declared.

8 minutes per child,25 more than twice mortality in Africa. ■

Résumé

Evaluation clinique et traitement dans les hôpitaux pédiatriques du Nord-est de la République-Unie de

Tanzanie

Objectif Nous avons évalué les soins pédiatriques dispensés dans 54 cas (11 %) et l’état mental dans 47 cas (9 %). Sur

dans 13 hôpitaux publics du Nord-est de la République-Unie 206 diagnostics de paludisme, 123 (60 %) avaient été établis

de Tanzanie afin de vérifier la conformité du diagnostic et du en présence d’un résultat négatif de l’examen sur lame ou en

traitement avec les directives actuelles en matière de soins. l’absence d’un tel résultat et 44 (36 %) des cas étaient traités

Méthodes Nous avons recueilli des données sur une période de par la quinine uniquement. Une malnutrition a été diagnostiquée

5 jours dans chaque site où l’on avait recensé des consultations chez 1 % des enfants hospitalisés, alors qu’un nouveau calcul

pédiatriques externes et nous avons extrait des dossiers des des z-scores évaluant l’état nutritionnel laissait prévoir une

enfants dans les hôpitaux un relevé des soins. Nous avons recueilli malnutrition aiguë sévère chez 5 à 10 % de ces enfants. Aucun

d’autres données en examinant les rapports hospitaliers et les stocks des hôpitaux ne disposait d’aliments appropriés pour de tels cas.

de fournitures dans les salles. Un dépistage du VIH/sida n’avait été pratiqué que chez 2 patients,

Résultats Sur les 1181 consultations externes recensées, il alors qu’on peut s’attendre à ce qu’environ 5 % des enfants

était fréquent que des signes cliniques de base n’aient pas été hospitalisés soient infectés par le VIH dans cette zone.

contrôlés : par exemple, sur 895 enfants avec des antécédents de Conclusion La médiocrité de l’évaluation clinique des enfants

fièvre, la température n’avait été mesurée que dans 57 % des cas admis dans les hôpitaux pédiatriques est choquante et cette

et sur 657 enfants présentant une toux ou une dyspnée, on avait médiocrité s’accompagne d’erreurs de diagnostic et de

mesuré la fréquence respiratoire que chez 57 (9 %) seulement traitement. Une amélioration de cette évaluation et de la tenue

d’entre eux. des dossiers est essentielle pour commencer à faire changer les

Sur 509 patients hospitalisés, le poids a été enregistré choses, mais y parvenir sera très difficile.

dans le dossier dans 250 cas (49 %), la fréquence respiratoire

Resumen

Examen y tratamiento clínicos en las salas de pediatría en el noreste de la República Unida de Tanzanía

Objetivo Evaluar la atención pediátrica dispensada en los 13 datos mediante la inspección de los suministros de sala y los

hospitales públicos del noreste de la República Unida de Tanzanía informes hospitalarios.

para determinar si los diagnósticos y tratamientos se ajustaban a Resultados En las 1181 consultas de pacientes ambulatorios

las directrices de atención en vigor. consideradas, con frecuencia se ignoraron durante la exploración

Métodos Durante un periodo de cinco días se reunieron datos signos clínicos básicos; por ejemplo, entre 895 niños con

en cada uno de los sitios donde se observaron las consultas de antecedentes de fiebre, sólo se midió la temperatura en un 57%

pediatría ambulatoria, y se elaboró un registro de la atención de los casos, y entre 657 niños con tos o disnea, sólo se examinó

dispensada a partir de las notas de seguimiento de los niños a 57 (9%) para determinar la frecuencia respiratoria.

atendidos en la sala de pediatría. Se obtuvieron también otros De 509 niños hospitalizados, se registró el peso en las

Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2) 137

Research

Clinical assessment and treatment in Tanzanian paediatric wards Hugh Reyburn et al.

notas de seguimiento de 250 (49%), la frecuencia respiratoria en previsible en la zona era que hubiese aproximadamente un 5%

54 (11%), y el estado mental en 47 (9%). De 206 diagnósticos de casos entre los niños ingresados.

de malaria, 123 (60%) se hicieron con frotis negativo o sin frotis, Conclusión El examen clínico de los niños ingresados en

y 44 (36%) de esos casos fueron tratados sólo con quinina. Se las salas de pediatría es preocupantemente deficiente y

diagnosticó malnutrición en un 1% de los niños ingresados, conlleva diagnósticos fallidos y tratamientos inadecuados. La

mientras que recalculando los valores zeta nutricionales se pudo introducción de mejoras en la exploración y los registros es una

deducir que un 5%-10% de ellos habían sufrido malnutrición condición esencial para propiciar los cambios necesarios, pero

aguda grave; ninguno de los hospitales disponía de los alimentos ello significa afrontar una ardua tarea.

apropiados. Sólo se diagnóstico VIH/SIDA en dos niños, cuando lo

ملخص

التقيـيم الرسيري واملعالجة يف أجنحة األطفال يف شامل رشق جمهورية تنزانيا املتحدة

ورسعة التنفس،)%49( ً مريضا250 ضمن املالحظات املدونة عن الحالة لنحو مستشفى من13 لقد قمنا بتقيـيم الرعاية املقدَّمة لألطفال يف:الهدف

وبالنسبة.)%9( ً مريضا47 والحالة النفسية لدى،)%11( ً مريضا54 لدى مستشفيات القطاع العام يف شامل رشق تنزانيا املتحدة ُب ْغ َية تحديد فيام

) كانت%60 حالة (أي نحو123 وجد أن، من حاالت املالريا206 لتشخيص إذا كانت تدابري التشخيص واملعالجة تـتامىش مع الدالئل اإلرشادية الحالية

) من هذه%36( 44 وتم معالجة،نتائج الرشيحة سلبية أو غري موجودة .للرعاية

من األطفال%1 وش ِّخص سوء التغذية لدى ُ .الحاالت باستخدام الكينني فقط تم تجميع املعطيات يف فتـرة تـربو عىل خمسة أيام من كل موقع:الطريقة

تشريZ الذين أدخلوا املستشفى عندما كانت إعادة حساب األحراز التغذوية من املواقع التي تم فيها مالحظة كيفية تقديم استشارات طب األطفال

بسوء التغذية الحاد الوخيم؛ ومل تتوافر%10 و%5 إىل إصابة ما يرتاوح بني واستُخلص سجل الرعاية من واقع املالحظات حول،للمرىض الخارج ِّيـني

شخصت اإلصابة مبرض ِّ كام.التغذية املالمئة يف أي من هذه املستشفيات كام تم تجميع معطيات إضافية من خالل،حاالت األطفال يف جناح األطفال

من%5 اإليدز والعدوى بفريوسه يف حالتني فقط بالرغم من توقع إصابة نحو . واإلمدادات املوجودة باألجنحة،فحص تقارير املستشفى

.األطفال الذين أدخلوا املستشفى يف هذه املنطقة بفريوس اإليدز مل يتم يف غالب، استشارة للمرىض الخارج ِّيـني1181 من بني:املوجودات

إن التقيـيم الرسيري لألطفال الذين يتم إدخالهم أجنحة األطفال:االستنتاج فعىل سبيل املثال من بني.األحيان التح ُّقق من العالمات الرسيرية األساسية

ناهيك عن ما يصاحبه من خطأ التشخيص،سيئ إىل درجة تبعث القلق فقط%57 تم قياس درجة الحرارة لنحو، طف ًال سبق إصابتهم بالحمى895

مام يستلزم االرتقاء بالتقيـيم وتحسني السجالت،واملعالجة غري املالمئة تم، طف ًال لديهم سوابق سعال أو ضيق تنفس657 ومن بني،من الحاالت

. وإن كان تحقيق ذلك مي ِّثل مهمة صعبة تكتنفها التحديات.إلحداث تغيـري .%9 أي ما ميثل نحو، طف ًال فقط57 فحص رسعة التنفس لنحو

فسجل الوزن

ِّ ، مرىض داخليـني باملستشفى509 أما يف ما يتعلق بنحو

References

1. Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying 11. Armstrong Schellenberg J, Bryce J, de Savigny D, Lambrechts T, Mbuya C,

every year? Lancet 2003;361:2226-34. PMID:12842379 doi:10.1016/ Mgalula L, et al. The effect of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness on

S0140-6736(03)13779-8 observed quality of care of under-fives in rural Tanzania. Health Policy Plan

2. Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K & Black RE. WHO estimates of the 2004;19:1-10. PMID:14679280 doi:10.1093/heapol/czh001

causes of death in children. Lancet 2005;365:1147-52. PMID:15794969 12. Marsh K, Forster D, Waruiru C, Mwangi I, Winstanley M, Marsh V, et al.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8 Indicators of life-threatening malaria in African children. N Engl J Med 1995;

3. Snow RW, Mung’ala VO, Foster D & Marsh K. The role of the district hospital 332:1399-404. PMID:7723795 doi:10.1056/NEJM199505253322102

in child survival at the Kenyan Coast. Afr J Health Sci 1994;1:71-5. 13. Reyburn H, Mbatia R, Drakeley C, Carneiro I, Mwakasungula E, Mwerinde O,

PMID:12153363 et al. Overdiagnosis of malaria in patients with severe febrile illness in

4. English M, Esamai F, Wasunna A, Were F, Ogutu B, Wamae A, et al. Delivery of Tanzania: a prospective study. BMJ 2004;329:1212. PMID:15542534

paediatric care at the first-referral level in Kenya. Lancet 2004;364:1622-9. doi:10.1136/bmj.38251.658229.55

PMID:15519635 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17318-2 14. Berkley JA, Lowe BS, Mwangi I, Williams T, Bauni E, Mwarumba S, et al.

5. English M, Esamai F, Wasunna A, Were F, Ogutu B, Wamae A, et al. Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. N Engl J

Assessment of inpatient paediatric care in first referral level hospitals in 13 Med 2005;352:39-47. PMID:15635111 doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040275

districts in Kenya. Lancet 2004;363:1948-53. PMID:15194254 doi:10.1016/ 15. Berkley JA, Maitland K, Mwangi I, Ngetsa C, Mwarumba S, Lowe BS, et al.

S0140-6736(04)16408-8 Use of clinical syndromes to target antibiotic prescribing in seriously ill

6. Nolan T, Angos P, Cunha AJ, Muhe L, Qazi S, Simoes EA, et al. Quality of children in malaria endemic area: observational study. BMJ 2005;330:995.

hospital care for seriously ill children in less-developed countries. Lancet PMID:15797893 doi:10.1136/bmj.38408.471991.8F

2001;357:106-10. PMID:11197397 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03542-X 16. Usen S, Weber M, Mulholland K, Jaffar S, Oparaugo A, Omosigho C, et al.

7. Management of the child with a serious infection or severe malnutrition: Clinical predictors of hypoxaemia in Gambian children with acute lower

guidelines for care at the first-referral level in developing countries. Geneva: respiratory tract infection: prospective cohort study. BMJ 1999;318:86-91.

WHO; 2000. PMID:9880280

8. Drakeley CJ, Carneiro I, Reyburn H, Malima R, Lusingu JP, Cox J, et al. 17. Berkley JA, Mwangi I, Ngetsa CJ, Mwarumba S, Lowe BS, Marsh K, et al.

Altitude-dependent and -independent variations in Plasmodium falciparum Diagnosis of acute bacterial meningitis in children at a district hospital in sub-

prevalence in northeastern Tanzania. J Infect Dis 2005;191:1589-98. Saharan Africa. Lancet 2001;357:1753-7. PMID:11403812 doi:10.1016/

PMID:15838785 doi:10.1086/429669 S0140-6736(00)04897-2

9. Tanzanian National Census 2002. United Republic of Tanzania.

10. Improving quality of paediatric care assessment tools. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

138 Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2)

Research

Hugh Reyburn et al. Clinical assessment and treatment in Tanzanian paediatric wards

18. Mwangi I, Berkley J, Lowe B, Peshu N, Marsh K, Newton CR. Acute bacterial 23. Duke T, Tamburlini G, Silimperi D. Improving the quality of paediatric care in

meningitis in children admitted to a rural Kenyan hospital: increasing peripheral hospitals in developing countries. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:563-5.

antibiotic resistance and outcome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002;21:1042-8. PMID:12818896 doi:10.1136/adc.88.7.563

PMID:12442027 doi:10.1097/00006454-200211000-00013 24. Guidelines for reforming hospitals at regional and district levels in Tanzania.

19. Report on Global HIV-AIDS Epidemic 2000. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2000. United Republic of Tanzania: Ministry of Health; 2005.

20. Rogerson SR, Gladstone M, Callaghan M, Erhart L, Rogerson SJ, Borgstein E, 25. Adam T, Manzi F, Schellenberg JA, Mgalula L, de Savigny D, Evans DB. Does

et al. HIV infection among paediatric in-patients in Blantyre, Malawi. Trans R the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness cost more than routine

Soc Trop Med Hyg 2004;98:544-52. PMID:15251404 doi:10.1016/j. care? Results from the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ

trstmh.2003.12.011 2005;83:369-77. PMID:15976878

21. The state of the world’s children, 2006.UNICEF; 2006.

22. Reyburn H, Mbatia R, Drakeley C, Bruce J, Carneiro I, Olomi R, et al.

Association of transmission intensity and age with clinical manifestations

and case fatality of severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. JAMA

2005;293:1461-70. PMID:15784869 doi:10.1001/jama.293.12.1461

Bulletin of the World Health Organization | February 2008, 86 (2) 139

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Wales 2004Dokument6 SeitenWales 2004Subha ManivannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of Distance and Quality of Care On Place of Delivery in Rural GhanaDokument8 SeitenThe Influence of Distance and Quality of Care On Place of Delivery in Rural GhanaJames Czar FontanillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S2666535220300057 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S2666535220300057 MainSensi Tresna AdilahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Pregnant MotherDokument7 SeitenKnowledge Attitude and Practice of Pregnant Motherمالك مناصرةNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Determinants of Acute Malnutrition Among ChildrenDokument8 Seiten5 Determinants of Acute Malnutrition Among ChildrenRezki Purnama YusufNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Dehydration of NewbornDokument7 SeitenJurnal Dehydration of NewbornRSU Aisyiyah PadangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lebanon - Congenital Anomalies Prevalence and Risk FactorsDokument7 SeitenLebanon - Congenital Anomalies Prevalence and Risk FactorsAbdelrhman WagdyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Routine Amoxicillin For Uncomplicated Severe Acute Malnutrition in ChildrenDokument10 SeitenRoutine Amoxicillin For Uncomplicated Severe Acute Malnutrition in ChildrenMc'onethree BrownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paediatric Surgery For Congenital Anomalies The Next Frontier - 2021 - The LanDokument2 SeitenPaediatric Surgery For Congenital Anomalies The Next Frontier - 2021 - The LanAvril JatariuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Influencing Nutritional Status and Food Consumption Patterns of ChildrenDokument18 SeitenFactors Influencing Nutritional Status and Food Consumption Patterns of ChildrenpopongNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Prevalence of Maternal Near Miss: A Systematic ReviewDokument9 SeitenThe Prevalence of Maternal Near Miss: A Systematic ReviewringgoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 37030-Article Text-130968-2-10-20190611 PDFDokument3 Seiten37030-Article Text-130968-2-10-20190611 PDFMuhammad YawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S095980491100400X Main PDFDokument10 Seiten1 s2.0 S095980491100400X Main PDFANA MARTINEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6754-Article Text-108154-1-10-20230524Dokument7 Seiten6754-Article Text-108154-1-10-20230524JOSHUA IARA BIAGNoch keine Bewertungen

- JurnaldfgdfsgxdgvcxDokument8 SeitenJurnaldfgdfsgxdgvcxYohan MaulanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Childhood Eating Disorders British National Surveillance StudyDokument7 SeitenChildhood Eating Disorders British National Surveillance StudygharrisanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutritional Status of Children Admitted To The Pediatric Department at A Tertiary Care Hospital, Sana'a, YemenDokument6 SeitenNutritional Status of Children Admitted To The Pediatric Department at A Tertiary Care Hospital, Sana'a, YemenInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstetric Referrals at Saint Paul'S Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC) : Pre-Referral Care and AppropriatenessDokument7 SeitenObstetric Referrals at Saint Paul'S Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC) : Pre-Referral Care and AppropriatenessTaklu Marama M. BaatiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- InIntegrating Traditional Healers in The Treatment of Tbtegrating Traditional Healers in The Treatment of TBDokument2 SeitenInIntegrating Traditional Healers in The Treatment of Tbtegrating Traditional Healers in The Treatment of TBGerald SackNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anaemia in Pregnancy Malaysia, APJCN2006 PDFDokument10 SeitenAnaemia in Pregnancy Malaysia, APJCN2006 PDFAkhmal SidekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotics As Part of The Management of Severe Acute MalnutritionDokument13 SeitenAntibiotics As Part of The Management of Severe Acute Malnutritionmarisa armyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijpedi2019 1054943Dokument9 SeitenIjpedi2019 1054943niaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pages 300-331Dokument31 SeitenPages 300-331aptureinc100% (13)

- Knowledge Level and Determinants of Neonatal Jaundice A Cross-Sectional Study in The Effutu Municipality of GhanaDokument10 SeitenKnowledge Level and Determinants of Neonatal Jaundice A Cross-Sectional Study in The Effutu Municipality of GhananicloverNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020Dokument18 Seiten2020SANDIE SORELLENoch keine Bewertungen

- Epidemiology of Malnutrition Among Pregnant Women and Associatedfactors in Central Refit Valley of Ethiopia 2016 2161 0509 1000222Dokument8 SeitenEpidemiology of Malnutrition Among Pregnant Women and Associatedfactors in Central Refit Valley of Ethiopia 2016 2161 0509 1000222tewoldeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research ArticleDokument7 SeitenResearch ArticletadessetogaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sickle Cell ServicesDokument3 SeitenSickle Cell Servicesstephen X-SILVERNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6469-Article Text-111142-1-10-20230621Dokument8 Seiten6469-Article Text-111142-1-10-20230621Nathalie ConchaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pembe 2010Dokument9 SeitenPembe 2010Berry BancinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Kidney Injury in Children: Incidence, Awareness and Outcome-A Retrospective Cohort StudyDokument8 SeitenAcute Kidney Injury in Children: Incidence, Awareness and Outcome-A Retrospective Cohort Studycantika larasatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knowledge and Practices of Mothers On Nigeria PDFDokument11 SeitenKnowledge and Practices of Mothers On Nigeria PDFalfinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neonatal Anemia Falciforme AngolaDokument13 SeitenNeonatal Anemia Falciforme AngolaSilvio BarbosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indicaciones NP Onc PedDokument7 SeitenIndicaciones NP Onc PedSebastian MarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHRONIC DiseaseDokument6 SeitenCHRONIC Diseaseberlian29031992Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pmed 1002547Dokument21 SeitenPmed 1002547Louinel JosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Obstetric Emergencies at The Maternity Center of The University Hospital Center of Ouemeplateau Chud Op in Benin 2167 0420 1000398Dokument6 SeitenManagement of Obstetric Emergencies at The Maternity Center of The University Hospital Center of Ouemeplateau Chud Op in Benin 2167 0420 1000398zahalina90Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nutrition Status and Risk Factors Associated With Length of Hospital Stay For Surgical PatientsDokument8 SeitenNutrition Status and Risk Factors Associated With Length of Hospital Stay For Surgical PatientsFarida MufidatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ZimbabweDokument10 SeitenZimbabweRosa ParksNoch keine Bewertungen

- 173641-Article Text-444853-1-10-20180622Dokument9 Seiten173641-Article Text-444853-1-10-20180622Alimatu AgongoNoch keine Bewertungen

- JurnalDokument7 SeitenJurnalRahmi SilviyaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of Risk Factors in Antenatal Women at Ishaka Adventist Hospital, UgandaDokument9 SeitenAssessment of Risk Factors in Antenatal Women at Ishaka Adventist Hospital, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNoch keine Bewertungen

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDokument8 SeitenNew England Journal Medicine: The ofAeny Al-khusnaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- PGH 107 04 198Dokument4 SeitenPGH 107 04 198shjahsjanshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wessels 1996Dokument5 SeitenWessels 1996Araceli Enríquez OvandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recognizable Birth Defects Among Neonatal Admissions at A Tertiary Hospital in South Western Uganda: Prevalence, Patterns and Associated FactorsDokument13 SeitenRecognizable Birth Defects Among Neonatal Admissions at A Tertiary Hospital in South Western Uganda: Prevalence, Patterns and Associated FactorsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal-Critique NematodeDokument13 SeitenJournal-Critique NematodeJOHN SETH LEWIS ANDRESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cohort Study Milk IsDokument6 SeitenCohort Study Milk Isحسان عبداللہNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Profile of Pediatric Solid Tumors: A Single Institution Experience in KashmirDokument7 SeitenA Profile of Pediatric Solid Tumors: A Single Institution Experience in KashmirAikawa MitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zimbabwe's Hospital Referral System: Does It Work? Zimbabwe's Hospital Referral System: Does It Work?Dokument12 SeitenZimbabwe's Hospital Referral System: Does It Work? Zimbabwe's Hospital Referral System: Does It Work?Hiten DabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of Oral Rehydration Therapy in The Treatment of Childhood Diarrhoea in Douala, CameroonDokument5 SeitenUse of Oral Rehydration Therapy in The Treatment of Childhood Diarrhoea in Douala, CameroonKiti AstutiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 Monitoring and Detection of Leprosy Patients in Southest China A Retrospective Study 2010 - 2014Dokument8 Seiten2018 Monitoring and Detection of Leprosy Patients in Southest China A Retrospective Study 2010 - 2014Jorge RicardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 09 ARTI Cecatti 232 238Dokument7 Seiten09 ARTI Cecatti 232 238plucichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diarrhea, Dehydration, and The Associated Mortality in Children With Complicated Severe Acute Malnutrition: A Prospective Cohort Study in UgandaDokument11 SeitenDiarrhea, Dehydration, and The Associated Mortality in Children With Complicated Severe Acute Malnutrition: A Prospective Cohort Study in Ugandasalma romnalia ashshofaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal 1 KEPDokument6 SeitenJurnal 1 KEPYosepha Devi AriskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caesarean in Rural Environment of Eastern Kasai (R.D. Congo) Cover of The Needs and Quality of The Services With Kasansa and TshilengeDokument8 SeitenCaesarean in Rural Environment of Eastern Kasai (R.D. Congo) Cover of The Needs and Quality of The Services With Kasansa and TshilengeAnonymous SMEU6r2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mortality After Inpatient Treatment For Diarrhea in Children: A Cohort StudyDokument15 SeitenMortality After Inpatient Treatment For Diarrhea in Children: A Cohort StudyRatu NajlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Undernutrition Among Children Under Five in The Bandja Village of Cameroon AfricaDokument6 SeitenUndernutrition Among Children Under Five in The Bandja Village of Cameroon AfricaMd UmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutritional Status and Dietary Diversity of Kamea in Gulf Province, Papua New GuineaDokument6 SeitenNutritional Status and Dietary Diversity of Kamea in Gulf Province, Papua New GuineaArdian SmNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPD Accredited Programmes-2018 PDFDokument75 SeitenCPD Accredited Programmes-2018 PDFOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Additional Qualification FormsDokument2 SeitenAdditional Qualification FormsOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ghs Act525Dokument24 SeitenGhs Act525Oheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPD Accredited Programmes-2018Dokument75 SeitenCPD Accredited Programmes-2018Oheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toc PDFDokument15 SeitenToc PDFOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Health Two (2) PH2 (2015)Dokument26 SeitenPublic Health Two (2) PH2 (2015)Oheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Guidelines On Fluid Therapy: Book ReviewDokument1 SeitePractical Guidelines On Fluid Therapy: Book ReviewOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- PHRD 4014-Top Drugs & Medical Terminology: Posey@ulm - EduDokument6 SeitenPHRD 4014-Top Drugs & Medical Terminology: Posey@ulm - EduOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alldiebedie - Commhealth - Essay N VivaDokument53 SeitenAlldiebedie - Commhealth - Essay N VivaOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Health One - Docx-1Dokument35 SeitenPublic Health One - Docx-1Oheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Guidelines On Fluid Therapy: Book ReviewDokument1 SeitePractical Guidelines On Fluid Therapy: Book ReviewOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- FractureDokument83 SeitenFractureOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approach To Practical Pediatrics, 2E (Manish Narang) (2011)Dokument461 SeitenApproach To Practical Pediatrics, 2E (Manish Narang) (2011)Oheneba Kwadjo Afari Debra75% (4)

- TocDokument16 SeitenTocrajenderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resistance: Leaving Cert Physics Long Questions 2018 - 2002Dokument19 SeitenResistance: Leaving Cert Physics Long Questions 2018 - 2002Oheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grand Rounds: A Method For Improving Student Learning and Client Care Continuity in A Student-Run Physical Therapy Pro Bono ClinicDokument21 SeitenGrand Rounds: A Method For Improving Student Learning and Client Care Continuity in A Student-Run Physical Therapy Pro Bono ClinicOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Guidelines On Fluid Therapy: Book ReviewDokument1 SeitePractical Guidelines On Fluid Therapy: Book ReviewOheneba Kwadjo Afari DebraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnosis, Internal MedicineDokument379 SeitenDiagnosis, Internal MedicineKiattipoom Sukkulcharoen96% (25)

- Program Studi Pemikiran Islam Program Pascasarjana Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta 2012Dokument29 SeitenProgram Studi Pemikiran Islam Program Pascasarjana Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta 2012SopyangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palmar Long Quiz Ratio AnswersDokument153 SeitenPalmar Long Quiz Ratio AnswersPatrisha May MahinayNoch keine Bewertungen

- LMR Answer KeyDokument18 SeitenLMR Answer KeyDon Marcus83% (6)

- Roehampton Hospital Case Study - Part 2Dokument2 SeitenRoehampton Hospital Case Study - Part 2akhil paulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Research ProblemsDokument12 SeitenSample Research ProblemsBenjamin Joel Breboneria100% (1)

- Fitterman, Robbie 10Dokument3 SeitenFitterman, Robbie 10Orlando LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entry Level Nurse Resume Sample - Windsor OriginalDokument2 SeitenEntry Level Nurse Resume Sample - Windsor OriginalTejinder BhattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Download Ebook Ebook PDF Neebs Mental Health Nursing 5th Edition PDFDokument41 SeitenFull Download Ebook Ebook PDF Neebs Mental Health Nursing 5th Edition PDFrobert.lorge145100% (38)

- Director Finance Accounting CFO in Tampa ST Petersburg FL Resume T Harry LinnDokument2 SeitenDirector Finance Accounting CFO in Tampa ST Petersburg FL Resume T Harry LinnTHarryLinnNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE HealthcareDokument3 SeitenGE Healthcarecharlie tomlinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care of The Hospitalized ChildDokument55 SeitenNursing Care of The Hospitalized ChildJose UringNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 - OIG CPG For Hospitals PDFDokument12 SeitenModule 1 - OIG CPG For Hospitals PDFSpit FireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Biotech Pharmaceutical Sales in Kansas City MO Resume James DebrickDokument2 SeitenMedical Biotech Pharmaceutical Sales in Kansas City MO Resume James DebrickJamesDebrickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Staff: Revised 2011 University of Michigan Hospitals and Health CentersDokument111 SeitenMedical Staff: Revised 2011 University of Michigan Hospitals and Health CentersRio P. BadriansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Comprehension #4Dokument2 SeitenReading Comprehension #4María Cristina Tobón SotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICICI Lombard Health Care Claim Form - HospitalisationDokument6 SeitenICICI Lombard Health Care Claim Form - HospitalisationEazhil DhayallanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health Service in Ghana: A Review of The CaseDokument15 SeitenMental Health Service in Ghana: A Review of The CaseIJPHSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic: Vitalconnect Definition:: Nursing InformaticsDokument4 SeitenTopic: Vitalconnect Definition:: Nursing InformaticsKenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poor-Quality-of-Healthcare-Services IN THE PHILIPPINESDokument8 SeitenPoor-Quality-of-Healthcare-Services IN THE PHILIPPINESceejay tamayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ranklen Hilajos Guirhem: Personal ParticularsDokument6 SeitenRanklen Hilajos Guirhem: Personal Particularsjay frankNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality in Health Care PDFDokument102 SeitenQuality in Health Care PDFjeetNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSKY Attached HospitalDokument8 SeitenBSKY Attached Hospitalsatyapriyakund1998Noch keine Bewertungen

- Caro Center EvaluationDokument51 SeitenCaro Center EvaluationMadeline CiakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Queensland ParliamentDokument142 SeitenQueensland ParliamentoscarnineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accreditation NABH Questionnaire JNABHHP 2014Dokument4 SeitenAccreditation NABH Questionnaire JNABHHP 2014adhishbasuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Byzantine MedicineDokument3 SeitenByzantine MedicineAainaa KhairuddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jawahar Bala Arogya Raksha (JBAR), Guidelines For Referral of The School Children, G.O.319, Dt.27.10Dokument6 SeitenJawahar Bala Arogya Raksha (JBAR), Guidelines For Referral of The School Children, G.O.319, Dt.27.10Narasimha SastryNoch keine Bewertungen

- HTDG, LLC and Timothy Stephen Smith and Respectfully Aver As FollowsDokument73 SeitenHTDG, LLC and Timothy Stephen Smith and Respectfully Aver As FollowsAnonymous GF8PPILW5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hospital Strategic Management Training PDFDokument9 SeitenHospital Strategic Management Training PDFkartikaNoch keine Bewertungen