Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Alchemy of Emotion (From Bhava To Rasa) (20417)

Hochgeladen von

Roxana CortésOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Alchemy of Emotion (From Bhava To Rasa) (20417)

Hochgeladen von

Roxana CortésCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

An Alchemy of Emotion: Rasa and Aesthetic Breakthroughs

Author(s): Kathleen Marie Higgins

Source: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 65, No. 1, Special Issue: Global

Theories of the Arts and Aesthetics (Winter, 2007), pp. 43-54

Published by: Wiley on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4622209 .

Accessed: 13/05/2013 15:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and The American Society for Aesthetics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

KATHLEENMARIE HIGGINS

An Alchemy of Emotion:Rasa and Aesthetic

Breakthroughs

"Now they're cookin'!" my companion an- and other breakthroughswithin human experi-

nounced.Thiswas the firstlive jazz performance ence.3Indianinvestigationof breakthroughsboth

I had ever witnessedand I was intriguedby his withinand beyondaestheticschallengesWestern

comment. Somethinghad changed for him just philosophy to investigate further art's connec-

then. Lackingmuch exposureto jazz before this, tions with the ethical and spiritualdimensionsof

I was not certainwhathad changed,but I wanted life.

to know. I consider these Indian analyses of aesthetic

The Westernaesthetictradition,for all it says breakthrough, beginningin SectionI witha discus-

about aesthetic experience,says little about the sionof the conceptof rasa,the emotionalflavorof

breakthroughthat precipitates it. The case of an aestheticexperience.In Section II, I consider

FriedrichNietzsche, a notable exception, is in- the mechanismsinvolvedin the productionof rasa

structive. In The Birth of Tragedy he describes in the contextof a dramaticperformanceandshow

the experienceof music as provokinga sense of thatthe experienceof rasais itselfan indicationof

transformedidentity,in whichawarenessof one's a breakthroughon the partof an audiencemem-

ordinaryroles drops away.He describesthe way ber. The spectatoroptimallymoves from aware-

in which this transformationrenderedthe spec- ness of the emotional content of a performance

tator of Athenian tragedya veritableDionysian (whichis evident to virtuallyany memberof the

votary,suddenlyable to see throughthe actorto audienceof a competentlyperformeddrama)to

the character,and throughthe characterto the a state of savoringthe drama'semotionalcharac-

god.' Nietzsche'semphasison thesemagicaltrans- ter in a universalizedmanner(somethingthat de-

formations,however,is not generallypickedup by pendson the particularspectator'sdegreeof spir-

laterWesternphilosophy. itual development,as we shall see). I proceedin

By contrast, we find a great deal on these Section III to considerAbhinavagupta'sauthori-

mattersin traditionalIndianaesthetics,whichfo- tative interpretationof rasatheory.Abhinavaex-

cuses on aestheticbreakthroughto a far greater plicates a numberof stages involved in the ex-

extent than the aesthetics of our own tradi- perience.He also suggeststhat the experienceof

tion. (Significantly,Arthur Schopenhauer'sac- rasa has a trajectoryof developmenttowardan-

count of spiritual transformation,which influ- other breakthrough,this one into a state of tran-

encedNietzsche'sanalysisof Greektragedy,draws quility,which I discuss in Section IV. Abhinava

directly on Indian thought.2)The Indian tradi- comparesattainingthe latterconditionto achiev-

tion analyzesthe psychologyof aestheticbreak- ing the most importantbreakthroughpossiblein

throughsandsituatesthemin the broadercontext a humanlife, thatof spiritualliberation,or moksa.

of humanaspirations.Theworkof Abhinavagupta Thus,the breakthroughsinvolvedin aestheticex-

(eleventh century), in particular,also analyzes periencefacilitatespiritualaspirationby offering

the relationship between aesthetic experience a taste of the achievedaim.4

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

44 GlobalTheoriesof the Arts and Aesthetics

I. dramais less focused on decisive events than is

Westerndrama,and the conventionis to idealize

The key to any analysisof aesthetictransforma- characters'actionsby presentingthem as accord-

tions in the Indiantraditionis the theoryof rasa, ing with dharma(the morallaw). The actionsthat

the emotional flavor of aesthetic experience.In Bharataemphasizesare those of the personplay-

this section, I discussthe basic terms bhava and ing the role of a character.Specifically,Bharata

rasa, which are discussedin the oldest surviving analyzesin detailthe physicalmovementsandges-

Indian text on aesthetics,the Natya~dstra.The turesof the actor,a topic ignoredby Aristotle.

termsarenot alwayskeptdistinctin thistext,but I Similarly,althoughboth thinkerstake unity to

follow the interpretationof Abhinavagupta,who be a criterionof successforthe work,the unitythat

uses these terms to make a basic distinctionbe- Bharataconsidersstemsfromthe achievementof

tweenemotionas it is renderedin dramaticperfor- a dominantmood or emotionaltone, while Aris-

mance and aestheticexperienceof an emotional totle seeks unityprimarilyin the plot (throughits

state, whichis an achievementon the part of the focuson a singleaction,its constrainedlength,and

spectator.5 so forth).9Moreover,both Aristotleand Bharata

The Ndtyasdstra,attributedto Bharata (200- contendthatthe aimin dramais to conveycertain

500 CE), is a detailed compendiumof technical emotionsto the audience.However,Aristotlecon-

knowledgeaboutthe performingarts.6A practical fines his discussionof the arousalof emotion by

manualfor the productionof successfuldramati- tragedyto a few remarks(for example,his con-

cal works,whichincludedmusicanddanceas well tention that tragedyshould arouse pity and fear

as acting,the Natyaidstraarticulatesrasa theory for the purposeof catharsisandhisclaimthateven

in light of the dramatist'spragmaticgoal of con- hearingthe basicplot outlineshouldarousethese

veying emotionalstates to the audience.Specifi- emotions).Bharata,on the otherhand,developsa

cally,it is concernedwith the practicalmeansfor detailedtaxonomyof emotion and emotionalex-

creatinga distinctmood throughthe performance pression,the topic to whichI now turn.

that can be transformedinto a rasa,aestheticrel- Thecentralimportanceof affectivetransforma-

ish of the emotionaltone,in the suitablycultivated tion in the Natyasastrais underscoredby the dis-

audience member.7(Bharataassumes that only tinction, suggested by the text, between bhdvas

the moreculturedanddiscerningtheatergoerswill and rasas.10 The dramatist'sgoal is to facilitate

havethisoptimumexperience,a matterthatI con- the transformationof a bhdva,an emotion rep-

sider later in more detail.) Everythingwithinthe resentedin the dramaand recognizedby the au-

dramashouldbe subordinateto the aimof produc- dience member,to a rasa, an experience of the

ing rasa, includingthe constructionof the plot.8 spectator.Thetermbhavameansboth"existence"

Alreadywe can observethe contrastbetweenthis and "mentalstate," and in aesthetic contexts it

Indianconceptionof aestheticexperience,which has been variouslytranslatedas "feelings,""psy-

emphasizesthe audiencesavoringparticularemo- chologicalstates,"and "emotions.""Bhdvasare

tionaltones,and variousWesternnotions,suchas emotionsor affectivestatesas they typicallyoccur

ImmanuelKant'scognitive"freeplayof imagina- in ordinarylife. In the contextof the drama,they

tion andunderstanding" or DavidHume'sgeneric are the emotionsrepresentedin the performance.

aesthetic"sentiment." According to the Natya?dstra, "Bhdva is so called

The statusof the Natyaidstrais akin to that of because of its representing(bhdvayan)the inner

Aristotle'sPoetics.Both offerdetailedaccountsof feeling of the play-wrightby meansof an expres-

whatit takesto writea goodplay(albeitthePoetics sion comingfromspeech, limbs,face and Sattva"

is restrictedto such a discussionof tragedy),and [thatis, involuntaryemotionalexpression,suchas

each providesits respectivetraditionwith basic shudderingor becomingpale].'2Bharataproposes

criteriaof artisticsuccessnot only for theater,but thatthe playwrighthas experiencedan emotion,a

for other arts as well. Yet there are some reveal- bhava,whichis then expressedthroughthe play;

ing contrasts.Both focus on action,but with very actors representthis emotion throughtheir per-

differentemphases.Aristotlestressesthe plot, the formance.

actions of the characterwithinthe drama,while Rasas, by contrast, are aesthetically trans-

Bharatadoes not. This is appropriate,for Indian formed emotional states experienced with

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Higgins An Alchemy of Emotion: Rasa and Aesthetic Breakthroughs 45

enjoymentby audiencemembers.The term rasa 11.

is not restrictedto aesthetic contexts. Arindam

Chakrabartiobserves that the term has many TheNatya dstraconsidersseveralaffectivedimen-

uses, all of whichinflectits aestheticmeaning:"a sions,all of whichplay a role in the productionof

fluidthattends to spill,a taste such as sour,sweet both the sthayibhdvaand the rasa.In this section,

or salty, the soul or quintessenceof something, I describethese,pointingout thatthey are insuffi-

a desire, a power, a chemical agent used in cientfor the achievementof rasawithoutthe audi-

changingone metal into another,the life-giving ence member'stranscendenceof narrowpersonal

sap in plants,and even poison!"13In its aesthetic interest.The aestheticbreakthroughof rasa, ac-

employment,the word rasa has been translated cordingly,dependson the moralcultivationof the

as "mood,""emotionaltone,"or "sentiment,"or spectatoras well as on featuresof the aesthetic

more literally,as "flavor,""taste,"or "juice."'14 object.

The gustatorycharacterof the term resembles How does the presentationof a sthdyibhava

that of the Westernaestheticterm "taste."How- lead to the experienceof rasa?The Natyasastra

ever, rasais not a faculty,as is Western"taste";it states: "Rasa is produced from a combina-

is literallythe activityof savoringan emotion in tion of determinants (vibhdvas), consequents

its full flavor.'1 (anubhavas),and complementarypsychological

In a dramatic production, the sthdyibhdva states (vyabicari-bhavas)."''20

The vibhdvas (liter-

(durableemotion) is the overarchingemotional ally the "causes"of "emotions")are the con-

tone of a play as a whole. Table 1 shows the ditions, the objects, and "other excitingcircum-

Natyasastra's lists of the sthdyibhdvas and the stances"that producethe emotionalstate in the

rasas.16 characters.21Forexample,in Hamlet,the determi-

Only certainemotionalflavorsare counted as nants of the emotion withinthe play (and hence

rasas.17The list of rasas comprisesan inventory of a spectator's specific rasa) are the circum-

of emotions as objects of aesthetic relish. Sig- stances of Hamlet's mother's remarriageto his

nificantly,they are characterizedimpersonally,as uncle, his encounterwith his father'sghost, the

emotionsin themselves,a matterto whichI shall suspicionsthisencounterleadshimto harbor,and

return.Each of the rasaslisted in Table 1 corre- so on.

spondsto a sthayibhdva,an emotionthatcanserve Theanubavas,translated"consequents"or "re-

as the basicaffectivetone of an entireplay.Inclu- sultant manifestations,"include the performer's

sion of emotionson the list of sthdyibhavas is de- gesturesandothermeansof expressingemotional

termined,accordingto scholarsA. K. Ramanujan states.22Someof these maybe involuntary,for ex-

and Edwin Gerow,by the fact that they are "so ample,sweating,horripilation,andshivering.Oth-

basic,so universal,so fundamentalin humanex- ers are voluntary,includingpatternsof actionand

perienceas to serve as the organizingprincipleof deliberategestures.Hamlet'spale aspect,his de-

a sustaineddramaticproduction."'1These basic meanor, his raving remarksin conversation,his

emotions were taken to be inherentpossibilities arrangingfor the productionof The Murderof

for all humanbeingsand thuseasily recognizable Gonzago, his accusationstowardhis mother,his

in a drama.19 killing Polonius,and so forth, are all among the

consequents.

The vyabicdribhavasare the complementary

Table 1 psychological states, also translated "transient

Durable Emotions emotions."These are those relativelybrief con-

(sthdyibhavas) Rasas ditions that, although fleeting, contribute to

Erotic love (rati) The erotic (Srnigdra) the basic emotional tone of the play. The

Mirth (hasya) The comic (hasya)

Sorrow(?oka) Thepathetic,or sorrowful

Ndtyasdstracites thirty-threeof these transient

(karuna)

emotions, including"discouragement,weakness,

Anger (krodha) The furious (raudra) apprehension,envy, intoxication,weariness,in-

Energy (utsdha) The heroic (vira) dolence,depression,anxiety,distraction,recollec-

Fear (bhaya) The terrible (bhaydnaka) tion, contentment,shame, inconstancy,joy, ag-

Disgust (jugupsd) The odious (bibhatsa)

Astonishment (vismaya) The marvelous(adbhuta) itation, stupor, arrogance,despair, impatience,

sleep,epilepsy,dreaming,awakening,indignation,

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

46 Global Theories of the Arts and Aesthetics

dissimulation, cruelty, assurance, sickness, insan- sensitivepeople (budha)enjoy in their mindsthe per-

ity, death, fright and deliberation."23 manentemotionspresentedwith differentkindsof the

This list includes many things that we in the actingout of (transient)emotions(and presentationof

West would not consider to be emotions at their causes).This is why (these primaryemotions)are

all, such as sleep, epilepsy, death, and deliber- knownas natyarasas.25

ation. These may, however, occur as side ef-

fects or consequences of an emotional state, and The ingredients-a combination of vibhavas

that is enough for Bharata to classify them as (determinants), anubhavas (consequents), and

vyabicaribhdvas.In the drama, these and the other vyabicdribhdvas(transient psychological states)-

vyabicdribhdvas are represented only in passing, are conjoined and altered through the chemistry

but they strengthen and provide shadings for the of acting into a form that can be aesthetically

durable emotions they accompany, though they relished by the audience. This passage is one in

are of brief duration. In Hamlet, for example, which the Natya?dstraequates the bhdvas (that is,

Hamlet's fear of the ghost, his wistful recollec- sthdyibhdvas) with rasas.

tion of Yorick, his sarcastic attitude in speaking to However, the Ndtya'sdstra makes it clear that

the king, his wrathful outburst toward his mother, even though a play competently conveys a durable

are all among the temporary emotional states that bhdva, every audience member does not automat-

Hamlet undergoes and that contribute to the im- ically experience rasa. Bharata emphasizes that

pression of his avenging anger as the prevailing the people who experience rasa are (according

emotional tone of the play. to various translations) "sensitive," "cultured," or

In addition to the vyabicdribhdvas, other "learned." He compares them to connoisseurs or

sthayibhavas can sometimes serve as transient gourmets. The tastes and understanding of peo-

affects that contribute to the formation of a ple varies depending on age, sex, and class. The

sthdyibhdva. For example, in Romeo and Juliet, cultivation necessary for rasa according to the

the relatively enduring sthdyibhava rati (erotic Natyaadstra involves general cultural sophistica-

love) contributes to the sthdyibhava ?oka (sor- tion (high social status and the education that at-

row), which is the overarching emotional tone of tends it, as well as awareness of cultural conven-

the play. tions) and also knowledge of the dramatic arts

The transformation that precipitates aesthetic and their conventions. Bharata sets the bar for the

experience is the conversion of a sthdyibhdva (that ideal spectator much higher than the requirements

is, a durable emotion) into a rasa. How does this Hume sets for the true judge of taste. Bharata stip-

happen? The Ndtyasastra compares the produc- ulates that ideal spectators are:

tion of a rasa to the preparation of a dish from its

various ingredients. "As a (spicy) flavour is created possessed of [good] character,high birth, quiet be-

from many substances (dravya) of different kinds, haviourand learning,are desirousof fame, virtue,are

in the same way the bhavas along with (various impartial,advancedin age, proficientin dramain all its

kinds of) acting, create rasas."24Bharata elabo- six limbs,alert,honest,unaffectedby passion,expertin

rates the gustatory metaphor in a way that empha- playingthe four kindsof musicalinstrument,very vir-

sizes the impact of well-combined elements of the tuous,acquaintedwith the Costumesand Make-up,the

drama on the sensitive member of the audience. rulesof dialects,the fourkindsof HistrionicRepresenta-

tion, grammar,prosody,andvarious[other]Sastras,are

As gourmets(sumanas)are able to savor the flavour expertsin differentartsand crafts,and have fine sense

of food preparedwith manyspices,and attainpleasure of the Sentimentsandthe PsychologicalStates.

etc.,so sensitivespectators(sumanas)savorthe primary

emotionssuggested... by the actingout of the various Moreover, the ideal spectator should be a paragon

bhavasand presentedwith the appropriatemodulation of "unruffled sense, ... honest, expert in the dis-

of the voice, movementsof the body and displayof in- cussion of pros and cons, detector of faults and ap-

voluntaryreactions,and attainpleasureetc. Therefore preciator [of merits]" and also experience "glad-

they are called ... ndtyarasas(dramaticflavours).On ness on seeing a person glad, and sorrow on see-

thissamesubjectthereare the followingtwo traditional ing him sorry," and be one who "feels miserable

... verses:As gourmets... savor food preparedwith on seeing him miserable." Bharata acknowledges

many tasty ingredients(dravya)and many spices. So that "[a]ll these various qualities are not known to

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Higgins An Alchemy of Emotion: Rasa and Aesthetic Breakthroughs 47

exist in one single spectator."He concludesthat a sthdyibhdvagives way to an experienceof rasa.

in a generalaudience"the inferiorcommonper- Laterinterpreterselaboratevariousaccounts,but

sons ... cannotbe expectedto appreciatethe per- the definitive analysis is provided by Abhinav-

formanceof the superiorones."26Only superior agupta (eleventh century).29Abhinavaguptais

individualsare likely to experiencerasa. one of the giantsof Indianthought.A theologian

Of Bharata'sprerequisitesfor the ideal specta- and mysticas well as a philosopher,he explicates

tor, later interpretersemphasizethe requirement the psychologicalpreconditionsforthe attainment

of being capable of empatheticresponse to the of rasa.I considerhis analysisin this section.

emotions of others as indispensableto the spec- AlthoughAbhinava,like Bharata,took the rasa

tator'sabilityto experiencerasa.The capacityto producedby dramato be paradigmatic,he also

take joy in the joys of others and feel sorrowin acknowledgedthe productionof rasain purelylit-

responseto the sorrowsof othersis crucialto the erary works.In this he follows the dhvani theo-

spectator'sabilityto thoroughlyimbibethe emo- rists (in particularAnandavardhanaof the ninth

tionalaspectsof the dramaand therebytake them century),who claimed that poetry conveys rasa

as objectsof aestheticsavoring.In this sense, the by means of suggestion (dhvani). Dhvani (also

rasika(the connoisseurwho experiencesrasa) is termed'vyaiijand')was proposedas a thirdpower

characterizedby a superiorityof moralcharacter, of language,in additionto abhidhd(denotation)

not just eminencewithinsociety. andlaksand(secondarymeaning,ormetonomy).30

Practicaldetailsof performanceand play con- While these other two powers convey meaning

structionare subordinatedin the Natyaidstrato conceptually,dhvani conveys affective meaning.

the goal of the presentinga sthdyibhdvaandfacili- Abhinava,endorsingthe idea of this thirdlinguis-

tatingthe experienceof rasa.In thisendeavor,the tic power,claimsthat rasa can be communicated

text detailsthe optimalway to sequenceepisodes only throughdhvani.Describingrasaas it is pro-

withina plot. It also elaborateson the waythe ac- ducedin poetry,Abhinavaassertsthat "rasais ...

tor should representthe unfoldingof emotional of a form that mustbe tastedby an act of blissful

expression,on the basis of how such expression relishingon thepartof a delicatemindthroughthe

occursin ordinarylife. Forexample,Bharatalists stimulation... of previouslydepositedmemoryel-

the stages of erotic love: longing,anxiety,recol- ementswhicharein keepingwiththe vibhdvasand

lection,enumerationsof the beloved'smerits,dis- anubhavas,beautifulbecauseof theirappealto the

tress, lamentation,insanity,sickness,stupor,and heart,whicharetransmittedby [suggestive]words

death.27He proceedsto itemizethe natureof each [of the poet]."31

of these andhow one indicatesthemon stage.For In this statement,Abhinavapostulatesthe role

example:"Whena womanintroducestopic about of unconsciousmemorytraces(samskdras)in the

him(i.e. the beloved)on all occasionsandhatesall arousalof rasa.He spells thisout in greaterdetail

[other]males,it is a case of Insanity.To represent in his discussionof a vignettefromthe Ramayana,

Insanityone shouldsometimelook with a stead- in which the sage Valmiki,the epic's traditional

fastgaze,sometimesheavea deep sigh,sometimes author, describes his coming to write the epic.

be absorbedwithinoneself and sometimesweep Valmikiwas bathingand enjoyingthe sight and

at the [usual]time for recreation."28

Properlypre- song of matingbirds,a pair of curlews.Suddenly,

sented, the variousgesturesand behaviorsof the he sawan arrowkill one of the birds.Valmiki'sre-

actors will replicatethe real sequence of stages sponseto thisscenewasto cursethe hunter,andas

experiencedby a person undergoinga particular he didso, his wordscameout in the formof a verse

emotion.The sensitiveaudiencemember,by em- (Sloka).Afterward,he was remorsefulat having

patheticallyattendingto this affectivetrajectory, cursedthe hunter,but also amazedby the poetic

experiencesthe tasteof the emotionin its essence, form that his curse had taken. Brahma,the Lord

that is, rasa. of Creation,appearedto Valmiki and said that

thesloka hadcome throughhis intention.He tells

Valmikito writethe Ramayanain?lokas, whichhe

III. does. Valmiki'spower to write poetry,according

to this legend, sprangforth as a consequenceof

The Natya•dstraremainsvague on the details of a powerfulemotionalexperience.Indeed,in that

whathappenswhenthe spectator'srecognitionof Valmikiis consideredthe first poet, the sugges-

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

48 Global Theories of the Arts and Aesthetics

tion is that poetry itself came into being in his lated, and he identifies this remembered grief with

manner. that of the bird.36However, he does not wallow

Characterizing Valmiki's experience as rasa, in memory of his own experience. Daniel H. H.

Abhinava explains: Ingalls interprets Abhinava as implying that when

the poet relishes the grief of others, "he has lost

The griefwhicharosefromthe separationof the pairof his own griefs within them.""37 As Abhinava him-

curlews,thatis,fromthedestructionof thematingarising self puts it:

fromthe killingof the bird'smate,a griefwhichwasa ba-

sic emotiondifferent,becauseof its hopelessness,from Grief is the basic emotion of the rasa of compassion,

the basic emotion of love found in love-in-separation: for compassionconsistsof relishing(or aestheticallyen-

thatgrief,by the poet'sruminatinguponits [alambana-]

joying) grief. That is to say, where we have the basic

vibhdvas[i.e.,the birds]in their[unhappy]state andon emotiongrief,a thought-trendthatfitswiththe vibhavas

the anubhdvasarisingtherefrom,suchas the wailing[of andanubhdvasof this grief,if it is relished(literally,if it

the survivingbird],met with a responsefrom his heart is chewedover and over), becomesa rasa and so from

andwithhis identifying[of the bird'sgriefwiththe grief its aptitude[towardthis end] one speaksof [any]basic

in his ownmemory]andso transformeditselfinto a pro- emotionas becominga rasa.Forthe basicemotionis put

cess of relishing.32 to use in the processof relishing:througha succession

of memoryelements it adds together a thought-trend

Abhinava describes the poet's rasa as arising

whichone has alreadyexperiencedin one's own life to

from his response to the emotion expressed by the

one whichone infersin another'slife, andso establishes

surviving bird.33The stages involved in Valmiki's a correspondencein one's heart.38

experience of rasa, then, include:

1. His recognition of the emotion expressed by The elements of resuscitated memory enable

the surviving bird, through witnessing the emo- one who experiences an artwork or other affect-

tion's vibhdvas (the circumstances causing it) producing stimuli to recognize the convergence of

and anubhdvas (the bird's involuntary emo- one's own experience and the emotion one en-

tional expressions). counters in another.39This recognition of common

2. His rumination on this emotion. emotional experience depends on moving beyond

3. His feeling response, predicated on his sense of a narrowly egoistic outlook to a more general-

sharing the emotion expressed by the bird. ized, transpersonal sense of the emotion.40 One

4. His aesthetic relishing of his continued rumi- interprets the perceived emotion as an instance

nation on the emotion, which is now felt to be of a type and recognizes its common character

with one's own remembered emotion, thereby un-

intersubjective.

dercutting one's sense of personally owning one's

Why should the poet relish what would seem to emotion. This breakthrough is essential for rasa to

be a very painful experience? Abhinava goes on occur.

to explain that grief is transformed into the rasa of An everyday example might help illuminate the

compassion. To explain how this differs from ordi- delight one experiences in rasa. An older adult, ob-

nary grief, he compares the emotion transformed serving the emotional expressions of a small child,

into rasa to "the spilling over of ajar filled with liq- is often reminded of his or her own juvenile emo-

uid."34Where Plato uses an image of iron rings be- tional experiences, particularly at times when the

ing joined together through magnetism, Abhinava adult is not called on to control the child's be-

uses the image of overflowing liquid to describe havior. The grandparent, for example, who finds

the rasa giving shape to the form of the poem, and virtually all the grandchild's responses charming

the further communication of rasa from the poet might well find the child's emotion familiar from

to the receptive reader or listener.35 his or her old childhood (or that of the child's par-

The poet's own experience of rasa depends on ents). Or a parent at a nonconfrontational mo-

empathy with the bird. According to Abhinava, ment might feel a certain delight in the sense that

the poet was experiencing rasa, however, not the the adolescent child's emotions and responses are

bhdva of grief. According to Abhinava, this em- steps along a well-traveled trail that the parent has

pathy arises because the poet has latent impres- also navigated. Although these reactions may be

sions of grief in his own memory, which are stimu- limited to a sense of sharing between oneself and

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Higgins An Alchemy of Emotion: Rasa and Aesthetic Breakthroughs 49

a close family member, they might also prompt re- it gives immediatepleasure,andit giveshappinesslater

flection on the emotional repertoire and trajectory (throughinstruction,whichif followed leads to happi-

of human beings generally. If the adult moves on ness).As forthosewhoarenot in sorrow,butarealmost

to this more general reflection, he or she is close to alwayshappy,such as princes,etc., even for them the

the type of contemplation that precipitates rasa. dramaprovidesinstructionin the waysof the worldand

The breakthrough that initiates the experience in the meansleadingto the (four)goals of life, such as

of rasa can be impeded by various obstacles. dharma,etc.... Question:does the dramainstructthe

Abhinava identifies seven. way a teacher(or an elderlyperson) does? (Answer:)

No. Ratherit causesone's wisdomto grow.42

1. Inability to find the drama convincing.

2. Overly personal identification. Valuable as enhanced wisdom is, aesthetic plea-

3. Absorption in one's own feelings. sure is the primary purpose of drama, according to

4. Incapacity of the appropriate sense organ. Abhinava. Indeed, aesthetic pleasure is the means

5. Lack of clarity within the play. to the wisdom available through art. "Even of in-

6. Lack of a dominant mental state. struction in the four goals of life delight is the final

7. Doubt about what emotion particular expres- and major result." Abhinava continues, "Nor are

sions are meant to convey.41 pleasure and instruction really different things, for

they both have the same object," that is, happi-

The elimination of these obstacles makes room ness.43

for the experience of rasa. Several of these (Nos. The kind of happiness Abhinava has in mind is

1, 5, and 7) depend primarily on the play and its "mental repose."44The detachment and profound

performance; even No. 6 can be considered a con- pleasure involved in rasa produce a sense of tran-

sequence of the play's inept focus. One (No. 4) quility, or equanimity, in the person who experi-

concerns the fact that sound sensory organs are ences it. Tranquility, or dantarasa,is the putative

necessary for artistic enjoyment. The remaining ninth rasa defended by some later interpreters of

impediments (Nos. 2 and 3) are psychological; they the Ndtyasdstra, including Anandavardhana and

are forms of inability to overcome narrow self- Abhinava.45 The legitimacy of this ninth rasa is

absorption. not a minor issue for Abhinava. He argues that all

The transformation of a bhava to a rasa de- other rasas guide one toward tranquility and that

pends on transcendence of the narrowly personal this is their ultimate goal.

sense of self. Accordingly, any experience of rasa The idea that all rasas tend toward tranquility

requires the overcoming of egoism. This break- suggests a further breakthrough that is possible

through enables the artistic audience member to within aesthetic experience. Relative to the other

achieve rasa, a condition of pleasure, or rapture. rasas, which correspond to emotions that are in

some sense driven toward an end, adntarasais the

most placid.46 The other rasas are more transi-

IV. tory in character than is ?dntarasa, and sdntarasa

is the aim of the others. Abhinava compares this

Beyond analyzing the breakthrough involved in supreme rasa to the experience of moksa, or spir-

the attainment of rasa, Abhinava also discusses itual liberation, the supreme goal of human life.

the possible development of the experience into Abhinava's interpretation of moksa is based on

a further breakthrough. In this section, I consider his religious views as a Saivite (a devotee of Siva).

his suggestion that rasa involves an inherent ten- His monistic theological vision has become the

dency toward tranquility, a condition that he sees canonical view of Kashmiri Saivism. Abhinava's

as resembling that of ultimate spiritual liberation. system holds that the only ultimate reality is the

Abhinava considers the delight of rasa to be consciousness of Siva. The world is a manifestion

basic to the value of drama, and he considers this of Siva, literally a play of Siva's consciousness.

as antecedent to any instruction that drama might The spiritual goal of the human being is to over-

offer. come the misconception that one has a distinct

individual being and to recognize one's identity

[T]hepurpose(of the drama)forthosewhoareunhappy (and the identity of the whole world) with Siva,

(is threefold):it calmsthe painof thosewho aregrieved, one's true Self. This recognition involves seeing

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

50 Global Theories of the Arts and Aesthetics

one's individual consciousness as a play of the uni- performing arts, rasa continues while the perfor-

versal consciousness. Compared with many other mance continues but does not persist beyond it.49

Indian systems, Kashmiri Saivism is highly life- Moksa, by contrast, endures. It is not dependent

affirmative, for it considers the world a manifesta- on a play or any other aesthetic phenomenon. In-

tion of the supreme reality and holds that realiza- stead, it is the blissful state of identification with

tion of one's true Self and the liberation, moksa, universal consciousness. The experience of moksa

that comes with it are possible within this life.47 is thus the most stable of all possible states of mind.

The experience of rasa borders on the experi- All other emotional conditions are transient in re-

ence of moksa. Lifting one to a transpersonal per- lation to it, even idntarasa.

spective on the emotion one tastes, rasa moves Nevertheless, Abhinava takes santarasa to be

one past the limitations of ego-identification and both a foretaste of moksa (liberation) and a means

closer to liberation. The kinship of rasa and moksa to understand it.50 Although similar to moksa,

becomes evident in Abhinava's analysis of the idntarasa is a response to the separate "world" of

durable emotion correlating with idntarasa. The the artistic performance, whereas moksa pertains

debate about the legitimacy of including ?dnta as to reality.51However, we tend to be deluded about

a rasa led to consideration of what sthdyibhava our real situation, and Abhinava considers the ex-

would correspond to dantarasa.The reasoning was perience of rasa through drama to be an ideal

that if ?antarasawere really a rasa, it should corre- metaphor for our actual status. As a Saivite, Abhi-

late with a sthdyibhdva, as does every other rasa. nava believes that Siva expresses himself through

Abhinava contended that this sthdyibhdva,the sta- our consciousness and action. In our world, Siva

ble basis for a rasa, would be the state of mind that in effect takes on the role of individuals in a play

is conducive to moksa. This state of mind would that he produces for his own delight. Siva identifies

be recognition of the Self, and the rasa associated with all the characters in the drama of our world.

with it involves the blissful taste of knowledge of Through rasa in response to drama we begin to

the Self. As in the case of other rasas, the con- approximate Siva's impersonal identification with

tent of the sthdyibhdvacarries over into adntarasa. every conscious being and all the actions of our

Knowledge of the Self is the basis for the tran- world. Rasa thus gives us a taste of the impersonal

quility that becomes ?dntarasawhen aesthetically identification that, sustained, would be liberation

enjoyed. However, this sthdyibhava is much more itself.

stable than the others, just as adntarasais the most The Western reader might wonder whether

stable of the rasas. Abhinava's theory has much relevance to some-

one who does not share his spiritual vision or the

(Theotherstates)suchas sexualpassion,whosemodeof Indian conviction that moksa is the supreme end of

existence(ever)is to be (either)facilitatedorobstructed, human life. Abhinava's suggestions that aesthetic

in accordancewiththe appearanceor disappearanceof experience leads to tranquility, and that this has

variouscausalfactors,are said to be "stable"relatively some significant but complex relationship to equa-

[apeksikatayd], to the extentthatthey attachthemselves nimity in "real" life are, however, transposable

for a time to the wallof the Self,whosenatureit is to be to Western formulation, regardless of whether we

"stable."Knowledgeof the truth,however,represents want to consider the possibility of a universal con-

thewallitself(on whicharedisplayed)allthe otheremo- sciousness. In secular Western terms, Abhinava's

tions [bhavantara],and is (thus), among all the stable analysis also prompts the question of whether aes-

(emotivestates), the most stable.... Before the stable thetic experience is a generic thing, or whether dif-

(affectivestate),knowledgeof the truth,theentiregroup ferent kinds of aesthetic experience have different

of mentalstates,both mundaneandtranscendental, be- preconditions and trajectories. Of interest, too, is

comes "transitory."48 Abhinava's view that pleasure, not moral message,

is the means by which the aesthetic dimension el-

?dntarasa, however, is not identical to moksa. evates the soul and improves the character, a posi-

Like all the other rasas, it is premised on the art- tion that somewhat resembles Friedrich Schiller's

work or other aesthetic phenomenon as its condi- but is largely foreign to Western aesthetics.

tion, for in rasa one aesthetically relishes an ob- More generally, the Indian aesthetic tradition

ject (for example, an emotion presented through builds its account of aesthetic experience from a

a play). Rasa is also transient. In the case of the psychology of emotions, and this serves as the basis

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Higgins An Alchemyof Emotion:Rasaand AestheticBreakthroughs 51

for analyzingaestheticbreakthroughs.Rasa the- Abhinavagupta is not the only Indian aesthetician to

ory offers an explanationfor the power and in- analyze aesthetic breakthroughs. A school of Bengali

Vaisnavites (devotees of Vishnu) in the sixteenth cen-

tersubjectivityof aestheticexperiencethat serves tury, among them Rupagisvamin,offer an alternative ac-

as an alternativeto both the Kantianinterplay count. For them, the supreme rasa was ?rnigara(the

of intellectualfacultiesand Hume's genericsen- erotic), which they considered to reach its pinnacle in

timentof taste.The psychologicalemphasisof In- devotion to the god (bhakti). They interpreted Irrigdra

dianaestheticsalsocontrastsstrikinglywithrecent as encompassing not only many other kinds of love be-

Westernaesthetics.Since the mid-twentiethcen- yond the erotic, but indeed all emotion. I will not, how-

ever, consider this school here, given the restrictions of

tury,anglophoneWesternphilosophyhas for the space. For a more extended summationof their views, see

most partresisteddiscussinginnerstates,with the Edwin Gerow, "Indian Aesthetics: A Philosophical Sur-

resultthatthe spiritualaspectsof art(andof other vey," in A Companion to World Philosophies, ed. Eliot

Deutsch and Ron Bontekoe (Malden,MA:Blackwell,1997),

phenomena)are approachedonly obliquely.Tra- pp. 319-321.

ditionalIndianaestheticsremindsus of how much 4. This point is made by Edwin Gerow. See Ed-

more there is (whether on heaven or on earth) win Gerow, "Abhinavagupta'sAesthetics as a Speculative

than contemporaryWesternphilosophyis willing Paradigm,"Journalof the AmericanOrientalSociety 114(2)

to dreamof. 52 (1994): 191.

5. The exclusionof rasa from the emotion that was pre-

sented on stage was an innovationof Abhinava. See Ingalls,

KATHLEENMARIE HIGGINS "Introduction,"p. 35.

of Philosophy

Department 6. I follow the customary practice of referring to the

of TexasatAustin

TheUniversity positions taken in the Ndtyaidstraas Bharata's,despite the

fact that modern scholarsdo not believe that this work was

Austin, 78712,USA

TX written by a single author. See Edwin Gerow, A Glossary

of Indian Figures of Speech (The Hague: Mouton, 1971),

INTERNET:

kmhiggins@mail.utexas.edu p. 75. See also Gerow, "IndianAesthetics: A Philosophical

Survey,"p. 315. There,Gerow points out that "the properly

aesthetic portions of the treatise are thought to be among

1. See FriedrichNietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy(with the latest matters added to the collection, perhapsin or by

The Case of Wagner),trans.WalterKaufmann(New York: the sixth centuryCE."

Vintage, 1966), ? 8, pp. 61-67. 7. "Aesthetic relish" is V. K. Chari's characterization

2. See Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and of rasa. See V. K. Chari, SanskritCriticism(University of

Representation,in 2 vols., trans.E. F. J. Payne (New York: Hawaii Press,1990),p. 9. Gerow characterizesrasaas "emo-

Dover, (vol. I) 1969 and (vol. II) 1958), vol. I, ? 68, pp. 378- tional 'tone."'See Gerow, "IndianAesthetics:A Philosoph-

398, especially pp. 388-389. Nietzsche was later critical of ical Survey,"p. 306.

Schopenhauer,but his thought remained profoundlyinflu- 8. See Bharata-muni(ascribed),TheNdtyaidstra,vol. I,

enced by the latter. chs.I-XXVII, rev.2nd ed., ed. andtrans.ManomohanGhosh

3. Abhinavagupta,who lived from the middle of the (Calcutta: Granthalaya, 1967) [hereafter N.S.], XXI.104,

tenth centuryinto the eleventh centuryCE, was prolific.He p. 396.

wrote numerous philosophical works, including commen- 9. See Gerow,A Glossaryof Indian Figuresof Speech,

taries and surveyson Tantraand the pratyabhijfid(recogni- p. 76.

tion) school of Saivism,literarycriticalworks,and religious 10. Again, this distinction is sharp in Abhinavagupta's

poetry.Abhinava'scontributionsto aesthetics are multiple. interpretation,which I follow here. The meaningsof these

He is noteworthyfor elaboratinga theory of the philosophi- terms are not consistently distinct in the Ndtyadstra itself.

cal foundationsof aestheticsin two importantcommentaries, Nevertheless,the termsare differentiated.Gerow notes that

the Locana (on Anandavardhana'sDhvanyaloka) and the even in the Ndatyaistra,rasa has "elements of the contem-

Abhinavabhdrati(on the Natya?dstra).These commentaries plative, the platonic, and the vicarious,"and he emphasizes

presenta numberof innovations,suchas the strictdistinction the universalcharacterof rasa.See Gerow,"IndianAesthet-

between the emotion of the characteron stage and rasa,and ics: A PhilosophicalSurvey,"p. 316.

an analysislinkingrasawith religion.(These innovationswill 11. RichardA. Shwederand JonathanHaidt, "TheCul-

be discussed below.) Despite his relative lack of interest in tural Psychology of the Emotions: Ancient and New," in

historyas such, Abhinavais also the primarysource through Handbook of the Emotions, 2nd ed., ed. Michael Lewis

which we know the aesthetic views of other importantaes- and JeannetteM. Haviland-Jones(New York:The Guilford

thetic theorists,such as Bhatta Lollata, who contended that Press,2000),p.399;A. K. Ramanujanand EdwinGerow,"In-

rasa was just an intensified form of a durable bhdva, and dianPoetics,"in TheLiteraturesofIndia:an Introduction,ed.

Bhattandyaka,who sought to undermine the concept of EdwardC. Dimock, Jr. (Universityof Chicago Press,1974),

dhvani, or poetic suggestion. See Daniel H. H. Ingalls,"In- p. 117;N.S., 1.2, p. 100 and VI.15, p. 102;Arthur Berriedale

troduction,"in The Dhvanyaloka of Anandavardhanawith Keith, TheSanskritDrama in its Origin,Development,The-

the LocanaofAbhinavagupta,ed. Daniel H. H. Ingalls;trans. ory, and Practice (Oxford University Press, 1924), p. 319;

Daniel H. H. Ingalls,Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, and M. V. Bharata-Muni,Aesthetic Rapture:The Rasidhydya of the

Patwardhan(HarvardUniversityPress,1990),p. 17nand pp. Nadyaidstra,ed. and trans.J. L. Masson and M.V.Patward-

30-32. han (Poona:Deccan College, 1970), p. 43.

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

52 GlobalTheoriesof the Arts and Aesthetics

12. N.S., XXIV.8,p. 443. Masson and Patwardhan,Sdntarasa,p. 123n;Gerow, "Abhi-

13. Arindam Chakrabarti,"Disgust and the Ugly in In- navagupta'sAesthetics as a SpeculativeParadigm,"p. 195n.

dian Aesthetics," in La PluralitdEstetica:Lasciti e irradi- Alexander Catlin points out that while the argument was

azioni oltre il Novecento,Associazione ItalianaStudi di Es- in circulationby the time Abhinava wrote his commentary

tetica,Annali 2000-2001 (Torino:Trauben,2002), p. 352. on Bharata, Abhinava rejected it. It was not demolished

14. Ramanujan and Gerow, "Indian Poetics," p. 117; by Abhinava'sargumentation,however, for the later figure

Gerow,"IndianAesthetics:A PhilosophicalSurvey,"p. 306. Mammata(active mid-late eleventh century) repeated this

15. ThisfollowsAbhinavagupta'saccount,whichempha- argument.See Alexander HavemeyerCatlin,"TheElucida-

sizes that rasais a type of perception.See J. MoussaieffMas- tion of Poetry:A Translationof ChaptersOne throughSix of

son and M. V. Patwardhan, ~intarasaand Abhinavagupta's Mammata'sKdvyaprakasawith Commentsand Notes" (un-

Philosophy of Aesthetics(Poona:BhandarkarOriental Re- published dissertation,The University of Texas at Austin,

searchInstitute,1969),pp. 73 and 73n [hereafterSantarasa]. 2005), ch. 4.

16. The translationsgiven are those in the translationof 24. The Ndtyaidstra,VI.35, as translatedin Masson and

the Ndtya dstraby ManomohanGhosh. See N.S., VI.15, p. Patwardhan,in AestheticRapture,pp. 46-47.

102. See also B. N. Goswamy, "Rasa: Delight of the Rea- 25. The Ndtya dstra, VI.37, as translated in Aesthetic

son," in Essence of Indian Art (San Francisco:Asian Art Rapture,pp. 46-47. Ghosh translatesthe passage as follows.

Museum of San Francisco,1986), pp. 17-30; Gerow, "Abhi-

[A]s taste (rasa)resultsfroma combinationof variousspices,

navagupta'sAesthetics as a SpeculativeParadigm,"p. 193n. vegetables and other articles,and as six tastes are produced

Gerow points out that it is appropriatethat the names of the

by articles such as, raw sugaror spices or vegetables, so the

rasas are formulatedas "descriptiveadjectives ... or their Durable PsychologicalStates,when they come togetherwith

appropriateabstractions."Interestingly,Bharatadivides the various other PsychologicalStates ..., attain the quality of

rasas into four that are more basic and four that are out- a Sentiment [rasa] [that is, become Sentiment (rasa)] ... it

growths of them. He describes the Erotic, the Furious,the is said that just as well disposed persons while eating food

Heroic, and the Odious as the "four [original]Sentiments," cooked with many kinds of spice, enjoy ... its tastes, and

and goes on to say, "the Comic [Sentiment]arises from the attain pleasureand satisfaction,so the culturedpeople taste

Erotic, the Pathetic from the Furious,the Marvellousfrom the Durable Psychological States [bhdvas] while they see

the Heroic, and the Terriblefrom the Odious."More specif- them representedby an expressionof the variousPsycholog-

ically, he says that "a mimicryof the Erotic [Sentiment] is ical States with Words,Gestures and the Sattva [involuntary

called the Comic,"while in the other cases, the second rasa emotional responses], and derive pleasure and satisfaction

results from the first (N.S., VI.38-41, p. 107). ... Forin this connnexionthere are two traditionalcouplets:

17. Later Indianthoughtdebated whether Bharata'slist

should be considered as exhaustive.Some later thinkersac- Just as a connoisseur of cooked food while eating food

cepted a ninth rasa, ?dntarasa(tranquility),as we shall see. ... which has been prepared from various spices and

S~ntarasawas also added to the list in a probablyspurious other articles taste it, so the learned people taste in

edition of the Nadtyaadstra. their heart (manas) the Durable Psychological States

18. Ramanujan and Gerow, "Indian Poetics," p. 135. (such as love, sorrow etc.) when they are represented by

See also Manomohan Ghosh, "Introduction," in The an expression of the Psychological States with Gestures.

Hence these Durable Psychological States in a drama are

Nadtyadstra,rev.2nd ed., p. xxxvii.

19. So characterized,the list of sthdyibhdvasbears some called Sentiments [rasas]. (N.S., VI.31-33, pp. 105-106)

resemblance to proposed lists of "basic emotions" that are 'Dravya'is the basic term for "substance."'Budha,'like the

the topic of cont emporary debate in psychology and phi- term 'Buddha,' comes from the root "budh,"which Hein-

losophy. See, for example, Paul Ekman, "An Argument for rich Zimmer translates as meaning "to wake, to rise from

Basic Emotions,"Cognitionand Emotion6 (1992): 169-200; sleep, to come to one's senses or regain consciousness;to

Robert C. Solomon, "Back to Basics: On the Very Idea of perceive, to notice, to recognize, to mark; to know under-

'Basic Emotions"' (1993, rev. 2001), in Not Passion'sSlave: stand, or comprehend; to deem, consider; to regard, es-

Emotions and Choice (Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. teem; to think, to reflect." See Heinrich Zimmer, Philoso-

115-142. However, Richard Shweder and Jonathan Haidt phies of India, ed. Joseph Campbell,Bollingen Series XXVI

have pointed out manydivergencesbetween the list of rasas (PrincetonUniversityPress, 1951),p. 320. This also the root

and Ekman'slist of basic emotions.See Shwederand Haidt, for "buddhi,"the intellect or faculty of (intuitive) aware-

"The Cultural Psychology of the Emotions: Ancient and ness, which is understoodto be independent of the ego, the

New," pp. 397-414. ego being dependent on it. It is the source of the insights

20. N.S., VI.31, p. 105. of the conscious mind, but the conscious mind does not

21. See Ghosh, "Introduction,"in The Ndtyaadstra,p. control it.

xxxviiin; Gerow, "Abhinavagupta'sAesthetics as a Specu- Manas is the thinking faculty, or mind. Sometimes the

lative Paradigm,"p. 194n; V. K. Chari, Sanskrit Criticism term manas is used to refer to the buddhi, but sometimes

(University of Hawaii Press, 1990), p. 17. (as, for example, in the Sdrikhyasystem) it is used for the

22. See Gerow, "Abhinavagupta'sAesthetics as a Spec- mental faculty as it is mediated by the ego (that is, the indi-

ulative Paradigm,"p. 194n. viduated sense of self).

23. N.S.,VI.18,p. 102.The firsttermon this list is nirveda, 26. N.S., XXVII.50-58, pp. 523-524. Bharata character-

which is often translated as "world-weariness."An argu- izes the way different types of people respond to drama in

ment was sometimes made that because this was the first N.S.,XXVII.60-62, p. 524. His variousaccountsof the differ-

term on the list of vyabicaribhavas,it might also be read as ent types of emotional display in persons of superior,mid-

the last in the list of durable emotions (sthayibhavas).See dling, and inferior quality also illuminate his conception of

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Higgins An Alchemyof Emotion:Rasaand AestheticBreakthroughs 53

these different social strata. See, for example, N.S., VII.14, 37. Abhinavagupta,Locana, 1.5L, p. 118n.

p. 123, and N.S., VII.40-44, p. 130. 38. Abhinavagupta, Locana, 1.5L, pp. 116-117. Al-

27. N.S., XXIV.169-171,p. 465. though the translationrefers here to inferring in another

28. N.S., XXIV.184-185,p. 468. person the same thought-trendone has experienced one-

29. Abhinava is our only source of knowledge of many self, we should not conclude that Abhinavaguptaconsiders

other contemporaneousinterpretationsof rasa theory. See rasa to be a matter of inference. Indeed, he devotes a con-

Navjivan Rastogi, "Re-Accessing Abhinavagupta,"in The siderableportion of the Locana to refutingthis idea.

VariegatedPlumage:EncounterswithIndian Philosophy (A 39. For Abhinava,sarnskiras, or latent memory traces,

CommemorationVolume in Honour of Pandit Jankinath include karmiclatencies from previous lives as well as from

Kaul "Kamal"),ed. N. B. Patil and MrinalKaul "Martand" the present one.

(Delhi: Motilal Banarsidassand Sant Samagam Research 40. Abhinavaattributesthe view that all representations

Institute,Jammu,2003), p. 144. withina play were generalizedto Bhaia Narilaya, a thinker

30. "Metonomy"is Gerow'stranslation.See Gerow,"In- with whom he agreed on many points. See Gerow, "Indian

dian Aesthetics,"p. 313. Laksaniasometimes is translatedas Aesthetics: A PhilosophicalSurvey,"pp. 316-317.

"metaphor,"but it has particularcharacteristicsthat make 41. Masson and Patwardhan,Santarasa,pp. 47-48.

this translationtoo broad. Lakniasdinvolves those alternate 42. Abhinavagupta, Abhinavabhdrati, on the

meanings that make sense of a locution when the obvious Ndtyadastra, 1.108-110, as translated in Masson and

denotation is blocked for some reason. Withouta blockage Patwardhan,?dntarasa,p. 57. See also Sdntarasa,pp. 54-57;

of the most obvious denotation, however, laksariadoes not Gerow, "Abhinavagupta's Aesthetics as a Speculative

occur. A classical example of laksaridis: "The village is on Paradigm,"p. 188. TraditionalIndian thought postulates

the Ganges."The "on"in Sanskrithas a very stronglocative four basic goals for human life: kama (sensual pleasure),

force, meaning "placed on top of." Since the village is not artha (material well-being), dharma (moral and religious

literally built on top of the waters of the Ganges, the state- duties), and moksa(spiritualliberation).Patankarcontends

ment is construed to mean that it is alongside the Ganges. that the durable emotions on which the rasas are built

See K. KunjunniRaja, Indian Theoriesof Meaning (Chen- are dominant within the psyche precisely because they do

nai: Adyar Libraryand Researc Centre, 1969), pp. 232-233. promote these ultimate goals. R. B. Patankar,"Does the

Raja does, however, translatelaksandas "metaphor." Rasa Theory Have Any Modern Relevance?" Philosophy

31. Abhinavagupta, Locana, in The Dhvanyaloka of East and West30 (1980): 301-302. Masson and Patwardhan

Anandavardhanawiththe Locana of Abhinavagupta,1.4aL, point out that Abhinava considers four mental states,

p. 81. which correlate with the four basic goals of life, to be

32. Abhinavagupta,Locana, 1.5, p. 115. most important. Abhinava's correlations are as follows:

33. Whetherpoets or actorsexperiencerasais the subject erotic love (rati) corresponds to the goal of kama; anger

of serious debate. See Masson and Patwardhan,?dntarasa, (krodha)correspondsto artha;energy (utsaha)corresponds

p. 84; Gerow,"Abhinavagupta'sAesthetics as a Speculative to kama, artha, and dharma;and a fourth, which Masson

Paradigm,"p. 188.Abhinavahimselfindicatesvariousviews and Patwardhan identify as nirveda (world-weariness),

on this topic, noting the difference between Lollata, who

corresponds to moksa. See Masson and Patwardhan,

contended that the actor felt rasa, and ?ankuka, who de-

pp. 47-48. Gerow's notes to his translation of

nied this. See Masson and Patwardhan, idntarasa,pp. 68- mdntarasa,

the Abhinavabharfti (Abhinava's Commentary on the

69. See also Goswamy,"Rasa:Delight of the Reason,"p. 25.

Natya~dstra)characterizesnirvedaas "that sense of futility

Goswamy points out that many commentators argue that following upon the recognition of the transiency of all

the actor can experience rasa only if he or she imagina- attainments, and leading to the desire for liberation."

tively takes on the point of view of a spectator.The Bengali See Gerow, "Abhinavagupta'sAesthetics as a Speculative

Vaisnavitesof the sixteenth century also held that the actor Paradigm,"p. 195n. In his translation, Gerow challenges

experiencesrasa.Theiranalysis,whichemphasizesthe role- Masson and Patwardhan'sidentification of nirveda as the

playingaspect of the humanbeing within the cosmic drama, sthdayibhdva of moksa. See pp. 196-197nn and p. 198n. I

largely eliminated the distinction between the actor and follow Gerow's readinghere.

the audience. See Ripagisvdmin, "BahktirasPmrta," trans.

43. Abhinavagupta,Locana,as translatedin Massonand

Jose Pereira, in Hindu Theology:A Reader, Jose Pereira,

ed. (Garden City, NY: Image Books, 1976), p. 339; David Patwardhan,?dntarasa,p. 55.

44. See Masson and Patwardhan, p. 56.

L. Habermas, Acting as a Way of Salvation: A Study of

45. Masson and Patwardhanpropose as its translation

•antarasa,

RdgdnugdBhaktiSddhana(Oxford University Press,1988), "the imaginative experience of tranquility."See Aesthetic

pp. 7-11 and 30-39.

34. Abhinavagupta,Locana, 1.5L, p. 115. Rapture,vol. I, p. III. The originsof this proposedadditionto

Bharata'slist of rasasare obscure;Masson and Patwardhan

35. Abhinava characterizesthe experience of the recep-

estimate that this idea may have been formulatedsometime

tive spectator as a "meltingof the mind,"a state that Mas-

aroundthe eighthcenturyCE. See Massonand Patwardhan,

son and Patwardhandescribe as "a state when the mind

Snmtarasa, p. 35. Although Abhinava seems to acknowledge

is exceedingly receptive." See Masson and Patwardhan, that Bharata's list included only eight rasas, he considers

?dntarasa,p. 83n.

Santarasato be consonant with the Nftyaaastra.The appro-

36. Abhinavagupta,Locana, 1.5L, pp. 115-116. Masson

priatenessof this addition continues to be debated.

and Patwardhancontend that even if the poet ever does feel

grief, he or she must take some distance on this immediate 46. ContemporarypsychologistNico Frijdaanalyzes all

emotional response in order to be able to compose poetry. emotions as involving action-tendencies.See Nico Frijda,

See Masson and Patwardhan,?dntarasa,p. 84. The Emotions (Cambridge University Press, and Paris:

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

54 GlobalTheoriesof the Arts and Aesthetics

Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, 1986), experience of rasa into a homogenous notion of aesthetic

pp. 69-90. Aesthetic emotions might seem to be counterex- experience.See Catlin, The Elucidationof Poetry,ch. 4.

amples, but action-tendencies need not be geared to en- 50. Contemporaryscholarsdisagree about whether Ab-

ergetic activity.Aesthetic emotion has a tendency to seek hinava'stheologicalcommitmentsshape his aestheticsor the

the continuation of savoring,as Frijdaargued in Nico Fri- other way around.Massonand Patwardhan,AestheticRap-

jda, "Refined Emotions,"presented at the general meeting ture, pp. 32-33, contend that Kashmiri?aivism is the basis

of the InternationalSociety for Research on the Emotions, for Abhinava'saesthetictheory. Gerow suggests that Abhi-

University of Bari, July 12, 2005. nava's aesthetics came first, and that his aesthetic thought

47. See Dr. KapilaVatsyayan,"?aivismandVaisnavism," helped him articulatehis theologicalandmetaphysicalviews.

in The VariegatedPlumage:Encounterswith Indian Philos- See Gerow, "Abhinavagupta'sAesthetics as a Speculative

ophy, pp. 124-125. Paradigm,"pp. 186-192. On this point I follow Gerow.

48. Abhinavagupta, Abhinavabhdrati,as translated in 51. This distinctionbetween the theatricaland ordinary

Gerow, "Abhinavagupta's Aesthetics as a Speculative worlds is denied by Rupagisvamin and other sixteenth-

Paradigm,"pp. 200-201. centuryBengali Vaisnavites.See Gerow,"IndianAesthetics:

49. Indeed, the rasas'dependence on conditions is what A PhilosophicalSurvey,"pp. 318-321.

differentiates them. My thanks to Alexander Catlin for 52. My thanksto StephenPhillipsand his aestheticssem-

pointing out that this is how Abhinava avoids collapsing inar for their insightson this topic.

This content downloaded from 132.248.101.205 on Mon, 13 May 2013 15:18:58 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Alone in The UniverseDokument12 SeitenAlone in The UniverseJustice Tamplen89% (9)

- Jazz and Improvisation BookletDokument16 SeitenJazz and Improvisation Bookletcharlmeatsix100% (3)

- Art of The Classic Fairy Tales From The Walt Disney Studio - Dreams Come TrueDokument30 SeitenArt of The Classic Fairy Tales From The Walt Disney Studio - Dreams Come TrueHaraldNastNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music GcseDokument45 SeitenMusic GcseAimee DohertyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 - Sylvan Barnet - Writing About Art PDFDokument6 Seiten01 - Sylvan Barnet - Writing About Art PDFRoxana Cortés20% (5)

- OBSTINATE ORTHODOXY - G.K. ChestertonDokument9 SeitenOBSTINATE ORTHODOXY - G.K. Chestertonfommmy9178Noch keine Bewertungen

- (Brill's Indological Library 6) Ian Charles Harris - The Continuity of Madhyamaka and Yogācāra in Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism (1991)Dokument202 Seiten(Brill's Indological Library 6) Ian Charles Harris - The Continuity of Madhyamaka and Yogācāra in Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism (1991)Thomas Johnson100% (1)

- SphotaDokument57 SeitenSphotaVikram BhaskaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhvanyaloka and It Critics Krishnamoorthy K. - TextDokument379 SeitenDhvanyaloka and It Critics Krishnamoorthy K. - Textvinay86% (7)

- The Thought of Nirad C. Chaudhuri IslamDokument26 SeitenThe Thought of Nirad C. Chaudhuri Islamsakupljackostiju100% (1)

- Dhvanyāloka 1Dokument21 SeitenDhvanyāloka 1Priyanka MokkapatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Natyashastra by Siddhartha SinghDokument20 SeitenThe Natyashastra by Siddhartha SinghSiddhartha SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plantations As ArchivesDokument22 SeitenPlantations As ArchivesIlyas Lu100% (1)

- Brahma Sutra - ChatussutriDokument38 SeitenBrahma Sutra - ChatussutriRAMESHBABUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bharatha's NatyashastraDokument331 SeitenBharatha's NatyashastraCentre for Traditional Education100% (3)

- World LiteratureDokument47 SeitenWorld LiteratureAljenneth Micaller100% (1)

- Jurgen Hanneder - Vedic and Tantric MantrasDokument21 SeitenJurgen Hanneder - Vedic and Tantric MantrasjesprileNoch keine Bewertungen

- Little Red Book of Sanskrit Paradigms - Devanagari Version - McComas TaylorDokument74 SeitenLittle Red Book of Sanskrit Paradigms - Devanagari Version - McComas TaylorAndre V.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Negotiating Tamil-Sanskrit Contacts-Engagements by Tamil GrammariansDokument26 SeitenNegotiating Tamil-Sanskrit Contacts-Engagements by Tamil GrammariansVeeramani Mani100% (1)

- Rasa Natyashastra To Bollywood PDFDokument292 SeitenRasa Natyashastra To Bollywood PDFIndavara GayathriNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Rasa Seen To Rasa HeardDokument19 SeitenFrom Rasa Seen To Rasa Heardsip5671100% (1)

- Sphota Doctrine in Sanskrit Semantics Demystified by Joshi N.R.Dokument16 SeitenSphota Doctrine in Sanskrit Semantics Demystified by Joshi N.R.PolisettyNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Neerja A. Gupta) A Students Handbook of Indian Ae (B-Ok - Xyz)Dokument143 Seiten(Neerja A. Gupta) A Students Handbook of Indian Ae (B-Ok - Xyz)KAUSTUBH100% (2)

- Indian and Western Aesthetics in Sri Aurobindo’s Criticism, A Comparative StudyVon EverandIndian and Western Aesthetics in Sri Aurobindo’s Criticism, A Comparative StudyBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- Influence of Spandasastra On Abhinavagupta's Philosophy-NirmalaDokument3 SeitenInfluence of Spandasastra On Abhinavagupta's Philosophy-Nirmalaitineo2012Noch keine Bewertungen

- Natya Nritta and Nritya - A Comparative Analysis of The Textual Definitions and Existing TraditionsDokument7 SeitenNatya Nritta and Nritya - A Comparative Analysis of The Textual Definitions and Existing TraditionsSubiksha SNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rasa Theory and The DarśanasDokument21 SeitenThe Rasa Theory and The DarśanasK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- Towards An Integral Appreciation of Abhinava's Aesthetics of RasaDokument54 SeitenTowards An Integral Appreciation of Abhinava's Aesthetics of Rasaitineo2012100% (1)

- Knowing Nothing: Candrakirti and Yogic PerceptionDokument37 SeitenKnowing Nothing: Candrakirti and Yogic PerceptionminoozolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- B. Baumer - Deciphering Indian Arts KalamulasastraDokument9 SeitenB. Baumer - Deciphering Indian Arts KalamulasastraaedicofidiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review of Abhinavagupta: An Historical and Philosophical Study by Kanti Chandra Pandey. Author of The Review, J.C. WrightDokument3 SeitenReview of Abhinavagupta: An Historical and Philosophical Study by Kanti Chandra Pandey. Author of The Review, J.C. WrightBen Williams100% (1)

- Indian AestheticsDokument92 SeitenIndian Aestheticsatrijoshi100% (1)

- A Study of Ratnagotravibhaga, Takasaki, 1966Dokument373 SeitenA Study of Ratnagotravibhaga, Takasaki, 1966Jonathan Shaw100% (2)

- Bibliography For The Study of Śaiva TantraDokument4 SeitenBibliography For The Study of Śaiva Tantravkas0% (1)

- A Study of Dharmakirti's Pramanavarttika - Masatoshi Nagatomi - TextDokument505 SeitenA Study of Dharmakirti's Pramanavarttika - Masatoshi Nagatomi - TextRamanatha BrahmacariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abhinavagupta's Comments On Aesthetics in Abhinavabhāratī and Locana - 30 Pag-SampleDokument30 SeitenAbhinavagupta's Comments On Aesthetics in Abhinavabhāratī and Locana - 30 Pag-SampleGeorge Bindu100% (1)

- Rasa TheoryDokument5 SeitenRasa TheoryhtreaswNoch keine Bewertungen

- A History of Indian Literature. Vol. V, Fasc.3. Indian Poetics. Edwin Gerow. Wiesbaden, 1977 (400dpi - Lossy)Dokument90 SeitenA History of Indian Literature. Vol. V, Fasc.3. Indian Poetics. Edwin Gerow. Wiesbaden, 1977 (400dpi - Lossy)sktkoshas100% (1)

- Emotions in Indian Drama and Dances 2012 PDFDokument47 SeitenEmotions in Indian Drama and Dances 2012 PDFRamani SwarnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SelfDokument10 SeitenSelfJay KayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Kashmir StudiesDokument139 SeitenJournal of Kashmir StudiesBoubaker JaziriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhvani TheoryDokument12 SeitenDhvani TheoryRatnakar KoliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissanayake - Homo AestheticusDokument383 SeitenDissanayake - Homo AestheticusRoxana Cortés83% (6)

- Stella Kramrisch - Expressiveness of Indian Art PDFDokument106 SeitenStella Kramrisch - Expressiveness of Indian Art PDFIndrajit BandyopadhyayNoch keine Bewertungen

- A History of Indian LogicDokument165 SeitenA History of Indian Logickadamba_kanana_swami100% (1)

- 10th Through 14th Century Indian AuthorsDokument202 Seiten10th Through 14th Century Indian AuthorsRādhe Govinda DāsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impossible DistanceDokument70 SeitenImpossible DistanceRoxana CortésNoch keine Bewertungen

- Līlāvatī Vīthī of Rāmapāṇivāda: with the Sanskrit Commentary “Prācī” and Introduction in EnglishVon EverandLīlāvatī Vīthī of Rāmapāṇivāda: with the Sanskrit Commentary “Prācī” and Introduction in EnglishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vakrokti and DhvaniDokument13 SeitenVakrokti and Dhvanivasya10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Digital SLR Photography - June 2016Dokument148 SeitenDigital SLR Photography - June 2016pejasrbijaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anaphor Resolution in Sanskrit: Issues and ChallengesDokument13 SeitenAnaphor Resolution in Sanskrit: Issues and ChallengesMadhav GopalNoch keine Bewertungen

- VEDANTA Heart of Hinduism 3Dokument9 SeitenVEDANTA Heart of Hinduism 3mayankdiptyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07 - Chapter 1 PDFDokument188 Seiten07 - Chapter 1 PDFakshat08Noch keine Bewertungen

- DhwaniDokument10 SeitenDhwaniSachin KetkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddhist Sanskrit in The Kalacakra Tantra, by John Newman PDFDokument20 SeitenBuddhist Sanskrit in The Kalacakra Tantra, by John Newman PDFdrago_rossoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romantic Moments in PoetryDokument54 SeitenRomantic Moments in PoetryAganooru VenkateswaruluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natya ShastraDokument4 SeitenNatya ShastraRatnakar KoliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sheldon Pollock - Bouquet of Rasa and River of RasaDokument40 SeitenSheldon Pollock - Bouquet of Rasa and River of Rasaniksheth257100% (2)

- Staal Happening PDFDokument24 SeitenStaal Happening PDFВладимир Дружинин100% (1)

- Kavya-Alankara-Vivrti - Sreenivasarao's BlogsDokument10 SeitenKavya-Alankara-Vivrti - Sreenivasarao's BlogsSovan ChakrabortyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natyasastra AestheticsDokument4 SeitenNatyasastra AestheticsSimhachalam ThamaranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddhacarita of Asvaghosa A Critical Study PDFDokument12 SeitenBuddhacarita of Asvaghosa A Critical Study PDFManjeet Parashar0% (1)

- Bronner and Shulman A Cloud Turned Goose': Sanskrit in The Vernacular MillenniumDokument31 SeitenBronner and Shulman A Cloud Turned Goose': Sanskrit in The Vernacular MillenniumCheriChe100% (1)

- Dheepa SundaramDokument290 SeitenDheepa SundaramMaldivo Giuseppe Vai100% (2)

- Donald Davis PurusharthaDokument28 SeitenDonald Davis Purusharthamohinder_singh_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Art, Beauty and CreativityDokument6 SeitenArt, Beauty and CreativityVarshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Extreme Poetry: The South Asian Movement of Simultaneous NarrationVon EverandExtreme Poetry: The South Asian Movement of Simultaneous NarrationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clark - Farewell To An IdeaDokument34 SeitenClark - Farewell To An IdeaRoxana Cortés75% (4)

- Arte Descentrado - Hans SedlmayrDokument22 SeitenArte Descentrado - Hans SedlmayrRoxana Cortés100% (1)

- Gombrich - EstiloDokument6 SeitenGombrich - EstiloRoxana CortésNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andrei Pop - How To Do Things With PicturesDokument45 SeitenAndrei Pop - How To Do Things With PicturesRoxana CortésNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 - Caglioti, Siddi, de Marchi - Verrocchio, Il Maestro Di LeonardoDokument3 Seiten02 - Caglioti, Siddi, de Marchi - Verrocchio, Il Maestro Di LeonardoRoxana CortésNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aalst, Belgium - WikipediaDokument1 SeiteAalst, Belgium - WikipediaNuri Zganka RekikNoch keine Bewertungen

- HampiDokument2 SeitenHampiTharun SampathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ciconia1400 1Dokument4 SeitenCiconia1400 1Виктор Бушиноски МакедонскиNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renaissance and Restoration TheatreDokument1 SeiteRenaissance and Restoration TheatrerawkboxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asian Paints PDCDokument11 SeitenAsian Paints PDCAshish BaidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davis Rotary Portable Sewing Machine Instruction ManualDokument30 SeitenDavis Rotary Portable Sewing Machine Instruction ManualiliiexpugnansNoch keine Bewertungen

- Serene EbrochureDokument13 SeitenSerene EbrochureMohamad SyafiqNoch keine Bewertungen

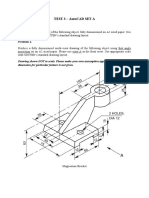

- MEMB113 Test 3 - AutoCAD Semester 1 1415Dokument11 SeitenMEMB113 Test 3 - AutoCAD Semester 1 1415haslina matzianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Floor FinishesDokument24 SeitenFloor FinishesEdgar JavierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Descriptive Writing - A Sunny Day in A Town or CityDokument1 SeiteDescriptive Writing - A Sunny Day in A Town or CityKashif Khan0% (1)

- 2019 JSC InfoDokument13 Seiten2019 JSC InfoJaze HydeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecorbusier and The Radiant City Contra True Urbanity and The EarthDokument9 SeitenLecorbusier and The Radiant City Contra True Urbanity and The EarthVivek BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jakarta Boxing Open KPJ Bulungan 11 Maret - PoldaDokument3 SeitenJakarta Boxing Open KPJ Bulungan 11 Maret - Poldasnapy wolterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jobsheet TSMDokument236 SeitenJobsheet TSMRizky YantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Artist Guia de FloresDokument75 SeitenAmerican Artist Guia de FloresgaryjoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lap FormerDokument2 SeitenLap FormerRatul Hasan100% (1)

- Dabu PrintingDokument23 SeitenDabu PrintingNamrata Lenka50% (4)

- 05esprit de CorpsDokument33 Seiten05esprit de CorpsMarek KubisiakNoch keine Bewertungen

- James Price Advanced 2D Animation (CT62DANI)Dokument12 SeitenJames Price Advanced 2D Animation (CT62DANI)JamesPriceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stage One Activity Plan - Colours in NatureDokument4 SeitenStage One Activity Plan - Colours in NatureSara JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bs 916 StandardDokument1 SeiteBs 916 Standardatif iqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4th Year 1st 1st Test 2023Dokument3 Seiten4th Year 1st 1st Test 2023salima190Noch keine Bewertungen