Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Case Study: Jack Welch's Creative Revolutionary Transformation of General Electric and The Thermidorean Reaction (1981-2004)

Hochgeladen von

aswanysankarOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case Study: Jack Welch's Creative Revolutionary Transformation of General Electric and The Thermidorean Reaction (1981-2004)

Hochgeladen von

aswanysankarCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

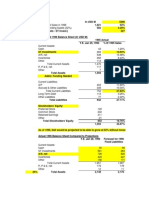

74 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

Case Study: Jack Welch’s Creative

Revolutionary Transformation of

General Electric and the Thermidorean

Reaction (1981–2004)

Pier A. Abetti

This case study draws a parallel between the French Revolution and the GE ‘revolution’,

according to three waves of transformation. We discuss the ‘hard’ effects on GE employees

(strategy, structure, employment, rewards) and the ‘soft’ effects (culture, work climate, indoc-

trination). In parallel with the French Revolution, the retirement of CEO Jack Welch was

followed by a ‘Thermidorean reaction’ characterized by the relaxation of Welch’s professional

and ethical standards, lassitude and indecision in the GE organization, and the fall of GE stock

price by 45 percent. Welch’s role as revolutionary leader and driving force is highlighted.

Introduction Thermidorean reaction after Welch’s

retirement. (The French Thermidorean

GE and Jack Welch’s Legacy reaction refers to the period after the Reign

of Terror, in 1794, when the tyrant Robe-

alued at $380 billion, General Electric

V (GE) is the world’s most valuable and

admired company. This status is still attrib-

spierre was removed from power and an

economically and culturally liberal gov-

ernment came to power.) This reaction, in

uted to the 20-year leadership of CEO Jack turn, was due to Welch’s less creative,

Welch (1981–2000). During that period, GE’s more opportunistic and more intolerant

market value increased 3213 percent at a leadership during his last years of tenure

compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of and the ensuing lassitude and indecision

20.4 percent, while the Standard and Poor 500 among employees (Abetti, 2001). The

(S&P) Index increased 915 percent (CAGR = question thus becomes: was the sharp

13.1 percent). Two years after Welch’s retire- decline of GE’s stock value due to the col-

ment, GE’s market value had fallen by 45 per- lapse of the Internet bubble or to the Ther-

cent, while the S&P index declined by 32 midorean reaction which, in turn, had its

percent. These figures lead to the conclusion root cause in Welch’s last years as CEO?

that GE’s success was essentially due to the

leadership of Welch and that his successor, Jeff

Immelt, was unable to maintain the momen- Objective, Methodology, Sources,

tum of his predecessor. However, two differ-

ing theories also need to be considered. and Plan

(1) GE was a company ‘built to last’ (Collins The objective of this historical study is to

and Porras, 1997). If GE had selected answer these questions by describing Welch’s

another CEO in 1981, he or she would career and his creative revolutionary transfor-

have obtained similar results. The ques- mation of GE according to three waves of ‘cre-

tion thus becomes: was Welch a product of ative destruction’ (Schumpeter, 1930) and their

GE, as claimed by Collins and Porras, or effects on GE’s employees, organization, and

was GE after 1981 a product of Welch? culture.

(2) The collapse of GE’s market value was We have deliberately elected not to draw on

primarily due to what can be called a the extensive and sometimes contradictory

Volume 15 Number 1 2006 © 2006 The Author

doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2006.00370.x Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing

CASE STUDY 75

theories of leadership in general and executive and Coutu, 2002). It should be noted that

or managerial leadership in particular. Rather, the last two sources must be treated with

since Welch was a revolutionary, always pro- caution. Welch’s autobiography was hast-

active, sometimes ruthless, we draw a parallel ily co-authored with a professional jour-

between his actions and the French Revolution nalistic writer. My analysis of the styles

(1789–1815) and other revolutions that had a in the text show that only around one-

major impact on their countries and the world, quarter of it was written by Welch. As will

namely the Russian Revolution (1917–1993), be described later, the final interview is a

the Chinese Revolution (1921–1972), the Mex- watered – down version of the original

ican Revolution (1911–1940), the Fascist Revo- interview that could not be published

lution in Italy (1919–1943) and the National- because of a conflict of interest.

Socialist Revolution in Germany (1923–1945)1. (6) Soon after his retirement, revelations about

In fact, GE’s value added in 1981 was of the Welch’s personal life stirred up many

same order of magnitude as the GNP of France scandalous stories in the popular press,

in 1789: $30 billion in 2004 prices2 (Hohenberg, (Beam, 2004), and in a book (Byron, 2004).

2005). Today GE’s value added is approxi-

The plan of this historical study follows the

mately $100 billion, similar to the GNP of Ire-

evolution of Welch from his family back-

land. We also draw a parallel between Welch’s

ground to his first job at GE; the event that

origins, motivation, leadership, personal and

caused him to become a revolutionary; his rise

managerial characteristics, and actions and

through the ranks by exploiting the GE sys-

those of the leaders of these other revolutions3.

tem; his selection as CEO; the coup d’état that

We hope this unorthodox approach will help

led to his assumption of full power; the three

answer the two controversial questions above.

creative revolutionary waves; their hard and

The sources for this study are the ample

soft effects on GE’s employees, organizations

business and popular literature on GE and

and culture; the hardening of his personality

Welch, and the author’s personal experience

and increasing intolerance of dissent; the

over 32 years (1948–1981) at GE, as well as his

attempt to keep power beyond the mandatory

conversations with other GE employees who

retirement age; the selection of three candi-

worked under Welch and his successor (1982–

dates for succession; the decision to appoint

2004).

one and fire the other two; the grooming,

The literature on GE and on Welch is

indeed attempted cloning, of his successor,

extensive but uneven. It can be divided into

Immelt. We then describe the Thermidorean

five categories.

reaction as it affected GE and its employees and

Welch personally, including business and mar-

(1) Serious business studies, such as the sem-

ital scandals that have left a permanent mark

inal study of GE by Collins and Porras

on Welch’s image.

(1997), and Harvard Business School and

We conclude by answering the two ques-

other cases, for instance, Aguilar et al.

tions above and by revealing the driving force

(1981, 1985, 1991); Malwight and Aguilar

underlying the rise and fall of American’s

(1996); Elderkin and Bartlett (1993); Jack

most successful and admired executive.

Welch, GE’s Revolutionary (1994); Heskett

(1999); Bartlett and Wozny (2000); Bartlett

and Glinka (2002); Bartlett and McLean

(2004).

Welch the Revolutionary

(2) Books and articles by Welch’s laudatory

semiofficial biographers (a better designa-

The Origins of the Revolutionary

tion would be hagiographers4) such as Slater Like many militant revolutionaries, Welch was

(1994, 1996, 1998, 2000); Tichy and Sher- born in a humble family of Irish descent at the

man (1994); Tichy and Cohen (1997); margins of the ruling class. His father was a

Heller (2001); Lowe (2001). conductor on a commuter railroad, the Boston

(3) A few critical studies, for instance, a well- and Maine, who sold and punched tickets and

researched book (O’Boyle, 1998) based never advanced in rank. More importantly,

mostly on interviews with disgruntled when Jack was born (1935), most members of

employees and Welch’s critics. the ruling class in the Boston area and execu-

(4) Countless interviews with Welch pub- tives in leading U.S. companies were WASPs

lished in a book (Lowe, 1998) and in busi- (White Anglo Saxon Protestants). Welch was

ness magazines, (Tichy and Charon, 1989), white, but Irish and Catholic, and regarded the

and in the popular press. ruling class with admiration, envy, and per-

(5) Welch’s autobiography (2001) with an haps some hostility. Ireland, which had been

afterword (2003) and a final interview in repressed for centuries by England, had just

the Harvard Business Review (Collingwood recently gained independence, in 1922.

© 2006 The Author

Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Volume 15 Number 1 2006

76 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

We can draw a parallel with Napoleon opportunity to revolutionize the system and

Buonaparte, who came from an impoverished make GE the world’s greatest company. To

Corsican family, despised by the French achieve this end, however, he had to gain

nobility. Welch’s roots in a comparable poor, power by becoming CEO.

despised minority could have given rise to a

comparable ambition to become the powerful

ruler of the majority.

The Rise of the Revolutionary

Welch was smart enough to obtain a Ph.D. According to Machiavelli (1515) there were

in engineering in three years. With his strong three ways to become the ruler of an Italian

technical background, he was hired by a lead- Renaissance state: (1) being chosen by the

ing, technologically advanced, growing and incumbent prince; (2) a palace revolution (coup

progressive company, GE, which was the ideal d’état); (3) violence. Welch advanced by being

vehicle for acquiring power. chosen by the incumbent president and then

implementing the coup d’état that allowed him

to revolutionize GE.

The Making of the Revolutionary After the Reign of Terror, Napoleon, a pen-

Most potential entrepreneurs do not launch niless general, was asked to subdue with a

their enterprises until they are either stimu- ‘whiff of grapeshot’ the mob that wanted to

lated or forced by a precipitating event, usu- restore the repressive regime of Robespierre.

ally a negative one such as dismissal for unjust Napoleon rose politically, was elected consul,

reasons, lack of recognition, or boredom (Tim- then first consul, then consul for life after a

mons, 1999). Similarly, many potential revolu- coup d’état in 1798. Finally he crowned him-

tionaries initially attempt to work within the self emperor.

system, hoping they can modify it through In a similar progression, Welch had first

persuasive or pacific means, until a major gained recognition by working within the sys-

shock convinces them that revolution is the tem before being selected as a candidate for

only possible solution. At the beginning of the succession and then, as CEO, revolutionizing

French Revolution the oppressed Third Estate GE. Although he hated GE’s highly politi-

(the 98 percent of the population who were cized, sanitized, ‘superficially congenial’

neither nobles nor clergy) addressed petitions (Welch, 2001) headquarters, with its bureau-

to the French king that went unanswered. cratic policies and procedures, he exploited

Only when the Third Estate was denied equal the system as he rose through the ranks. He

representation did they rebel against the king gained recognition through hard work,

and storm the Bastille. In Mexico, Francisco detailed analyses, polished presentations, and

Madero sought power through a democratic most of all outstanding business results.

election and started a revolution only after the Nonetheless, in 1975, he was not on the list of

vote was rigged by the incumbent dictator ten possible successors to CEO Reginald Jones,

Porfirio Diaz. In Russia, Lenin began by trying who was to retire in five years. The senior vice

to gain control of the democratically elected president of human resources believed Welch

Constituent Assembly. After he was forced drove too hard for results and had too little

into hiding, he decided to overthrow the gov- respect for the company’s rituals and tradition

ernment by violent means. (Welch, 2001).

Welch’s first job at GE was with the Plastics But Jones was also frustrated with GE’s

Division, an innovative venture outside GE’s slow-moving bureaucracy and wanted a

conservative electrical core business. He was successor who would shake things up. He

given responsibility for developing a new insisted that Welch be the eleventh candidate.

product and for the pilot plant. By working In 1979, Jones interviewed all of them accord-

extremely hard, he achieved outstanding ing to the ‘airplane interview,’ whose format

results his first year. He expected to be com- was: ‘You and I are flying in a company plane.

pensated financially and with a promotion, as The plane crashes and we both die. Who

he had been promised before he was hired. should be the next CEO of GE?’ The purpose

Instead his supervisor, apparently a bureau- was to determine each candidate’s opinion of

crat who did not appreciate Welch’s zeal, gave the other contenders and whether they would

him a minimal raise. This was the precipitat- be able to work together after Jones’ retire-

ing event that pushed him over the line. He ment. But Welch had his own agenda: to prove

decided to quit GE and look for more reward- he was the best choice for CEO. He conve-

ing employment. Fortunately for GE, his niently forgot he was supposed to be dead and

potential had been noticed by a vice president proposed himself as Jones’ successor!

who was able to convince Welch to stay thanks As a final test, Jones named three of the

to a substantial raise and promises of a bril- candidates, including Welch, vice-chairmen.

liant career. Welch realized he had a unique Welch proved his ability and was named CEO

© 2006 The Author

Volume 15 Number 1 2006 Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing

CASE STUDY 77

on April 1, 1981. He had gained limited power ended the dog-and-pony show. He wanted to

by climbing the traditional ladder. Over time lead rather than ‘review and approve.’ He did

he built a small, dedicated group of young, not want to see the books, but rather look into

aggressive followers who shared his vision the heads and hearts of the business leaders

of the new GE and were loyal to him. As and the passion they poured into their argu-

with Napoleon, these ‘dashing generals’ were ments. With two powerful actions – the mas-

rewarded with promotions, recognition as sive dismissal of people and the dismantling

members of the elite team, and generous of the bureaucracy – Welch showed that he

financial packages, as long as they kept winning. was fully in charge. Now he was ready to start

the revolution5.

Welch’s Coup d’Etat

To assert himself and prove he was in charge, Welch’s Creative Revolution

Welch consolidated his power through a coup (1981–2000)

d’état. His goal was to seize the few neural

centers where power was exercised and from The Three Waves

there to conquer the entire constituency

By definition, the goal of a revolution is to

(Malaparte, 1931). Accordingly, he started at

destroy a regime that is unsatisfactory to the

headquarters and eliminated the complacent

majority of the people (‘stakeholders’ in busi-

bureaucrats who might offer passive resis-

ness parlance) and replace it with a new order6

tance, firing 167 out of 200 and adding 67

that, it is hoped, will meet their needs and

members of his own loyal team.

aspirations. Welch achieved this goal over 20

He also realized that the world was entering

years by bringing about a revolution in waves.

a recession and that GE should reduce

The advantage of acting in separate waves

expenses, becoming ‘mean and lean’ to face

rather than one continuous revolution is that

the double challenge of a recession and

revolutionary fervor cannot last forever. Peo-

increased international competition. He laid

ple become tired and want to relax and enjoy

off 80,000 employees the first year and 42,000

the rewards of their work. To make progress,

over the next two years, targeting older, more

they must be reenergized and pushed ahead in

expensive employees who might be more

periodic waves.

resistant to change. There was one problem:

Welch’s 20-year revolution can be conceptu-

GE’s long-standing policy that employees

alized as three waves with the following start-

with 25 or more years of service could not be

ing dates and major objectives:

dismissed for lack of work. Welch realized that

canceling this policy would have negative 1981, first wave (hard)

repercussions among stakeholders and the

Create a new vision and strategy to drive

press and therefore decided to add the words

reorganization, mass dismissals, divest-

‘when appropriate’ to the policy. As far as I

ments and acquisitions.

know, not one single case of ‘appropriateness’

was ever registered! 1985, second wave (soft)

In parallel with dismantling the infrastruc-

Revolutionize GE to gain the strengths of a

ture of the GE bureaucracy, Welch wanted to

big company with the leanness and agility

change the modus operandi at headquarters and

of a small company.

in the field. This was exemplified by the prep-

aration and review of the plans of GE’s 65 stra- 1996, third wave (soft and hard)

tegic business units (SBUs). From January to

Develop an integrated, boundaryless,

May, every SBU prepared strategic plans of

stretched, total quality company with

100 or more pages with detailed forecasts for

A-players.

the next five years. Staff headquarters checked

and even graded them. They then prepared The characterization of the waves as hard or

tough or irrelevant questions for the CEO and soft refers to the means Welch employed. In

top executives to ask during the formal review the hard waves, the lives of the employees

in July. These reviews were elaborately pre- are physically disrupted by mass dismissals,

pared and rehearsed to avoid unpleasant sur- divestments, acquisitions and major organiza-

prises. Welch put an end to all this. He refused tional changes. In the soft waves, the minds

to see the books before the presentation and and habits of the employees are disturbed,

insisted on asking his own questions. The because they must absorb new ways of oper-

formal presentations with over 40 people ation and new working practices. Physical dis-

in attendance became shirt-sleeve, informal, ruption is minimal, except for those who

open discussions of the business and its cannot cope with the new company environ-

challenges with fewer than 10 persons. Welch ment and are forced to leave.

© 2006 The Author

Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Volume 15 Number 1 2006

78 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

The First Wave (1981–1984) 2. Reducing staff and changing its role from

controlling and revising to assisting and

Now that Welch had conquered headquarters, coaching.

he had to conquer the field, including the 3. Instituting a new reward system based

minds of managers, staff, and workers of all more on performance bonuses rather than

ranks. To achieve this, Welch, for the first time salaries, with more stock options.

in GE’s history7, created a unified vision and 4. Ending employment security. The company

strategy for the entire company, the famous could dismiss anybody, any time, regard-

three-circle concept. All GE businesses had to less of length of service or merit. At the

fit within three categories: same time, employees who found better

1. Core business (such as Power Generation, jobs outside the company were free to leave

Appliances) with moderate returns, managed and would not be considered disloyal.

as cash cows with selective investments. The first wave had created a smoothly func-

2. High-tech businesses (such as Medical Sys- tioning company that generated plenty of

tems, Plastics and Aircraft Engines) with cash. A portion of this cash was paid to the

high growth, negative cash flow and high stockholders, but the majority was reinvested

investments. in R&D, capital investments, and acquisitions,

3. Services (such as GE Capital, NBC and which, in turn, generated more cash, a concept

Information Services) with high returns, developed by Welch that was called the ‘GE

high growth, cash generation and low growth engine’ (Elderkin and Bartlett, 1993).

investments. The second wave created a more efficient,

Welch then evaluated each business. Those streamlined organization that reduced bure-

that were first or second in their industry were aucracy and motivated employees, through

placed inside one of the three circles. The oth- tangible incentives, to achieve improved

ers were given two years to become first or financial results.

second. If they could not, they were closed or

sold. Welch’s message to all employees was

crystal clear: Be first or second! If not, you’re out! The Third Wave

At the same time, Welch regrouped the 65 Because GE’s success was identified with

SBUs into 13 businesses, which he managed Welch personally rather than the new GE sys-

directly. Welch carried his message to the tem, the challenge was to prevent a slackening

field and met formally and informally with of efforts and a slowdown in growth and prof-

employees of all ranks. Because of his its after his retirement. In the third wave, he

working-class origins, Welch could relate eas- had to create new GE values, a new GE cul-

ily to blue-collar workers and listen to their ture, and an emotional climate that would

suggestions for improving efficiency. He regu- transcend his personality as well as his strate-

larly visited the GE executive training center gic and organizational reforms.

in Crotonville, N.Y., to give lectures and meet The third wave was both soft and hard. On

informally with future general managers. He the soft side, it included watchwords like

listened to their complaints about the linger- ‘speed, simplicity and self-confidence,’ ‘can-

ing bureaucracy and delays in obtaining dor, openness, ownership,’ ‘integrated diver-

approvals and decisions from superiors. sity,’ and even ‘evangelizing.’ On the hard side

Welch’s ‘workout’ meetings (Ulrich et al., was the total quality (six sigma) initiative,

2000) may be compared to Chairman Mao’s which produced significant results. To enforce

frequent meetings with Chinese workers and the six sigma culture, Welch made it clear that

soldiers, and his management meetings to nobody would be promoted unless he or

Mao’s open discussions with the younger she was a certified ‘black-belt’ team leader

party leaders. (Heckett, 1999). Welch then started a similar

campaign for digitization and e-commerce. All

The Second Wave (1985–1995) managers had to find a mentor who would

teach them how to access the Internet (Bartlett

Having achieved, almost by force, impressive

and Glinka, 2002).

financial results, Welch was concerned that

Probably the most important aspect of the

GE’s organization would not be able to main-

third wave was the selection of a top team of

tain its growth rate. Therefore, he embarked

A-players, the future leaders of GE (Bartlett

on a major reorganization that would ensure

and McLean, 2004). We know that Welch stud-

the motivation and the capability to grow suc-

ied the German strategies of World War I and

cessfully. He took the following actions:

admired the German general staff. He may

1. Flattening of the corporate pyramid from also have read Karl von Clausewitz’s famous

eight to four levels. treatise Vom Kriege (On War) (1830). Welch’s

© 2006 The Author

Volume 15 Number 1 2006 Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing

CASE STUDY 79

Imperial Germany The New GE

Smart Stupid Achievers Non-

Achievers

General Teach Motivate

Eager Out! Believers and and

Staff

Stretch Train

Force Non- Do Not

Lazy Troops Believers Out!

Them Hire

Karl von Clausewitz, 1830 Jack Welch, 2000

Figure 1. Welch’s third wave: selecting leaders.

Source: Abetti (2001)

criteria for selecting leaders are very similar to their wallets a card listing the GE values, just

the criteria for selecting the elite members of as Chinese party members, soldiers, and stu-

the German general staff. As shown in the left dents had to carry Chairman Mao’s Little Red

matrix of Figure 1, Clausewitz classified all Book. Welch applied these same values as cri-

potential candidates as smart or stupid and as teria for selecting GE’s future leaders.

eager or lazy. There are four possible combina- Welch characterized potential leaders in the

tions: new GE as achievers and non-achievers,

believers and non-believers, as shown on the

1. The ‘smart and eager’ (top left quadrant)

right side of Figure 1. There are four possible

are the obvious choice, but there are not

combinations:

enough of them.

2. Therefore, the ‘smart and lazy’ will be 1. ‘Achievers and believers’ are the obvious

forced to move from the lower left to the choice, but there are not enough of them.

upper left quadrant. 2. Therefore, the ‘believers and non-achievers’

3. If they do not respond, they will have to are motivated and trained to move from the

join the ‘stupid and lazy’ troops in the top right to the top left quadrant.

lower right quadrant. 3. ‘Non-achievers and non-believers’ should

4. ‘Stupid and eager’ is the worst combination not be hired.

because these people cause all kinds of 4. The ‘achievers and non-believers’ repre-

trouble with their overzealousness. They sented a problem for Welch. His attitude

should be thrown out! toward them changed over time. Initially he

recognized grudgingly their contributions

but also saw them as a management prob-

Welch’s Succession and Retirement lem. Later, in his last letter to stockholders,

Welch launched a crusade to eliminate

The Hardening of Welch

type-IV managers:

At the end of the third wave, faced with the

‘. . . we have to remove these type IV’s

prospect of mandatory retirement, Welch’s

because they have the power, by them-

attitude hardened. He became more and more

selves, to destroy the open, informed, trust-

demanding, setting unattainable stretch goals,

based culture we need to win today and

and more intolerant of dissent. For instance,

tomorrow . . . There are undoubtedly a few

while most companies would be content with

type IV’s remaining, and they must be

a 10 percent annual increase in operating

found. They must leave the company

margins, say from 10 to 11 percent, Welch

because their behavior weakens the trust

demanded a 50 percent increase, from 10 to 15

that more than 300,000 people have in its

percent, and a doubling of inventory turns.

leadership.’ (GE Annual Report, 2000)

Attempting to achieve such goals can cause

exhaustion or ‘fixing the books;’ missing the Here again, a parallel with major revolutions

goals can cause fear of sanctions and loss of is instructive. The French Revolution did away

morale. Welch also demanded more and more with the moderates, the Russian Revolution

conformity with his tenets. For several years, cast out the non-party specialists who had

GE managers were encouraged to carry in contributed to the post-war reconstruction,

© 2006 The Author

Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Volume 15 Number 1 2006

80 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

and Mao’s Cultural Revolution purged intel- trust authority of the European Economic

lectuals. History shows that all these purges Community. The deal fell through and

caused economic disruptions. Welch finally retired, having lost glory and

To summarize, during the first wave, Welch credibility.

changed the physical infrastructure of GE and

what people did. During the second wave he

changed the organization and how people

Welch’s Succession

operated. During the third wave, he changed Although he was in no hurry to retire, Welch

the culture and both what and how people selected potential successors following GE’s

should think. personnel policies and the example set by

It should be noted that the psychological Reginald Jones (Bartlett and McLean, 2004).

pressure on employees and their resentment However, the way Welch treated his potential

and potential resistance increased as one wave successors, especially the two losing candi-

was followed by the next. During the first dates, was quite different.

wave, employees were told what to do. They Like Jones, Welch narrowed his search to

recognized that it was part of management’s three candidates, but they were all working in

prerogatives, indeed of management’s duties, the field, not at headquarters. Welch chal-

to direct their effort where it would be most lenged each one to outperform the others and

valuable for the company. During the second to develop a successor who would be able to

wave, employees were told how to do their take over if that candidate was appointed

assignments. Thus, there was some concern CEO. After heated competition, Welch

that experimentation and creativity may have selected Jeff Immelt, whom he had mentored

been curtailed during the second wave. Dur- for many years, and who was loyal to him.

ing the third wave, employees were asked to Immelt had been in charge since 1997 of GE

endorse without reservations the new GE values, Medical Systems, Welch’s most successful

culture, and emotional climate. This new business before he was named CEO (Khanna

approach is potentially dangerous, because: and Weber, 2002).

The day before he announced his successor,

1. Some employees may be rewarded for

Welch took the company plane to Milwaukee

being politically correct rather than for their

to give the good news to Immelt. Then he flew

results;

to Cincinnati and Schenectady and fired the

2. Some high-performing employees may be

two losing candidates. GE was known as the

considered politically unreliable and forced

company that trained future CEOs and, in fact,

to leave;

some of the unsuccessful front runners for

3. Some employees may be afraid to speak

Welch’s job had already left GE to head For-

their minds for fear of retaliation.

tune 500 companies. Welch told the two losers

Here again, a parallel with revolutions is ‘You are going to be offered a CEO position

instructive. The situation above corresponds sooner or later, so you should leave right now!’

to the beginning of the Terror during the As a ruthless politician he knew the losers

French Revolution (1793)8. could do nothing more for him and thus fol-

A fourth wave from Welch would not have lowed the maxim: ‘In politics there is no grat-

been viable because it would have demanded itude because nothing is ever given’ (Guzman,

more conformity than was good for the com- 1951).

pany and more submission than the employ- On November 27, 2000, Welch and Immelt

ees were willing to accept. But in line with GE appeared on television in identical blue shirts

policy, it was time for Welch to retire. open at the collar, navy sports coats, even

matching tasseled loafers–the non plus ultra of

conformity! No wonder Fortune called Immelt

Welch’s Last Stand ‘The Man who would be Welch’ (Moore, 2000).

Welch, however, was not ready to give up From then on, Immelt’s problem was being

power. He wanted to leave with a bang, some considered Welch’s clone, and clones are never

major business coup that would satisfy his ego as good as the original. Welch kept Immelt on

and consolidate his fame as the world’s most a leash for nine months as he gradually turned

admired executive (Murray et al., 2000). Hav- over power. According to Sonnenfeld’s typol-

ing heard that Honeywell was being sold, ogy of succession patterns (1988), Welch was a

Welch made a last-minute offer at an inflated general who was leaving reluctantly and try-

price. Then he stated that he would not retire ing to stay in charge. Welch retired in Septem-

until this acquisition was consummated and ber 2001, and it was only after three years that

Honeywell was successfully integrated within Immelt began to shake his image as Welch’s

GE. Fortunately for GE stakeholders, Welch follower. In 2004 Fortune changed its tune and

was unable to obtain approval from the anti- the headlines were ‘Another boss, another

© 2006 The Author

Volume 15 Number 1 2006 Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing

CASE STUDY 81

revolution. Jeff Immelt is following a time- The Thermidorean Reaction at GE

honored GE tradition: abandoning the most (2002–2004)

treasured ideas of his predecessor’ (Useem,

2004). In the case of GE, the Thermidorean reaction,

which came after 20 years of Welch’s revolu-

tion, had three main aspects:

The Thermidorean Reaction 1. Lassitude among GE employees who

hoped to relax under Immelt, who was

Welch’s ‘Terror’ reputed to be less ‘mean’ than Welch. Their

attitude was ‘let’s wait and see which way

As the French Revolution evolved and France Jeff will go.’

fought to prevent European powers from 2. A reexamination by business analysts and

invading and reinstating the king, Robespierre the press of GE’s financial results, account-

became dictator and instituted the Reign of ing practices, and forecasts. For instance,

Terror. Two hundred years have passed, and The Economist published an article critical of

GE is not France, nor are its competitors GE with the headline ‘The Jack and Jeff

striving to conquer GE. Nonetheless, Welch show loses its luster’ (Economist, 2002).

instituted his own polices of conformity, as 3. A long period of transition (2002–2004)

described above, as well as a reign of terror while Immelt was reenergizing GE and dif-

(Byron, 2004) to consolidate and assert his ferentiating himself from Welch.

power. GE managers and employees were

scared by Welch’s increasing outbursts of rage,

even over small issues, that were punctuated Welch’s ‘Thermidor’

by foul language. The worst, however, was his For Welch the Thermidorean reaction led to

policy that every year ten percent of employ- changes in his personal and professional

ees in each department must be replaced. behavior that tarnished his image. Suffice it

Across the board the lowest performers were to say that The Economist, which had often

removed, regardless of their actual perfor- praised Welch to the sky, became disillusioned

mance. This policy is not effective (Lawler, and excoriated him as an ‘aging philanderer’

2002), and in the case of GE was clearly unfair, (Allio, 2003). This radical change in Welch’s

because some departments had excellent image was due to two episodes that were

results, others poor results. No matter, ten per- treated as scandals in the press and in a book:

cent had to go (Welch, 2001)! Also, as dis- his severance package and his affair with a

cussed above, some higher performers who prominent editor.

were suspected of disloyalty to Welch’s values The policy and practice at GE has always

or who lacked political support were fired. In been no employment contracts. Employees

this way Welch kept everybody on edge and can be terminated by the company at will, and

paved the way for the Thermidorean reaction. they can also leave at anytime. In 1996, five

years before his retirement, Welch negotiated a

The Thermidorean Reaction in France contract that included an extremely generous,

even lavish, package of life-long, post-

(1793–98) retirement benefits. This contract came to light

During the Reign of Terror, Roberpierre when Welch’s second wife sued for divorce

demanded complete loyalty to the principles and claimed a payment of almost half a billion

of the Revolution, and he executed anyone dollars. Welch, who had been praising ‘open-

suspected of dissent or disloyalty. This lasted ness, simplicity and unyielding integrity,’ was

until July 27, 1794 (9 Thermidor, year II accord- condemned by the press. He had no choice but

ing to the new Revolutionary calendar), when to give up the entire package and repay GE for

Robespierre and his associates were over- $2 to $2.5 million annually in services (Welch,

thrown and executed in a coup d’état. The 2002). The second scandal was caused by an

people of France, tired after years of turmoil, interview with the editor of Harvard Business

gave a sigh of relief and supported the new, Review that promoted Welch’s autobiography.

more moderate leaders, who were called The resultant headline in Business Week was

Thermidoreans. ‘Too Close for Comfort. GE’s legendary former

This was the beginning of the Thermidorean CEO Jack Welch kicks up a controversy over

reaction, which lasted until Napoleon took his affair with a journalist.’ The journalist

power. It was characterized by relaxed moral boasted openly of her relationship with Welch

standards, conspicuous consumption, drunk- and ‘quit after having lost the confidence of

enness, orgies and sexual license, all fueled her staff’ (Orecklen, 2002). Due to the conflict

by war profiteering, political payoffs and of interest, a watered-down version of the

corruption. interview was edited by others (Collinwood

© 2006 The Author

Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Volume 15 Number 1 2006

82 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

and Coute, 2002). Other dismal aspects of accomplishments are unique in the history of

Welch’s Thermidor were publicized as a result business. He transformed a mature electrical

of the divorce proceedings but will not be dis- company with a slow-moving, overstaffed

cussed here. bureaucracy, poor cash flow, and lethargic

stock into a global powerhouse, where electri-

cal products represent only 15 percent of sales,

Conclusion other innovative high-tech products (aircraft

engines, engineering plastics, man-made dia-

Answers to the Two Questions monds, medical diagnostic systems, etc.) 10

percent, and services 75 percent.

After having described the rise and fall of the While there have been many revolutionary

revolutionary Jack Welch, his creative trans- leaders in politics and business with clear

formation of GE, and the Thermidorean reac- vision and unbreakable motivation to imple-

tion, we turn to the two questions at the ment their vision, not many have succeeded in

beginning of this paper: maintaining the momentum for 20 years.

1. Was Welch a product of GE, as claimed by Welch is unique in his successful implementa-

Collins and Porras, or was GE (after 1981) tion of revolutionary change in a company that

a product of Welch? was already among the most admired when he

became CEO. How did Welch achieve this?

Our conclusion is that, while GE would The progress of nations is marked by revo-

have selected another capable executive in lutions that lead to a higher level of wellbeing

his stead, GE’s revolutionary transforma- for the citizens. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in

tion was due primarily, if not exclusively, to 1787 ‘A little rebellion now and then is a good

Welch’s creative leadership. In fact, it is thing’ (Jefferson, 1853–54).9 In a similar man-

clear that Welch, as a true revolutionary, ner, according to Greiner (1972), companies do

intended to overthrow the GE system after not grow continuously and smoothly but

his disillusionment with his first year of rather go through periods of evolution and

employment, and that he worked within revolution, separated by crises. According to

the system in order to become CEO, seize Collins and Porras (1997):

power through a coup d’état, and destroy

the old system. Visionary companies install powerful

mechanisms to create discomfort to obliter-

2. Was the major decline of GE’s stock value ate complacency and thereby stimulate

due to the collapse of the Internet bubble or change and improvement before the exter-

to the Thermidorean reaction, which in turn nal world demands it.

had its root cause in Welch’s last years as

CEO? Visionary companies are created by vision-

ary leaders who take advantage of impending

GE’s stock fell 45 percent from 2000 to external crises (as an economic recession) or

2003, while the S&P Index fell by 32 percent. even create their own crises in order to revo-

Other large, well-managed companies were lutionize the company and raise it to a higher

less affected. Microsoft fell 19 percent, Wal- level of performance. Markides (1998) states:

Mart 10 percent and IBM 22 percent. As dis-

cussed above, Welch’s hardening and his The successful innovators were not afraid

determination to stay in power would have to destabilize a smooth running machine

made a fourth wave of change ineffective, and to do so periodically but contin-

indeed dangerous, for GE. We have also uously. . . . The development of positive

shown that Welch’s insistence that his suc- crises. . . . is a powerful mechanism to des-

cessor should be his clone reinforced the tabilize the system and start the thinking

effects of the Thermidorean reaction and process again. . . .

delayed for three years Immelt’s establish- However, one revolution is not enough. The

ment as the new CEO and his differentiation revolutionary spirit fades over time, and a

from the Welch legacy. Our conclusion is that Thermidorean reaction follows10. At the same

Welch was the major cause of both GE’s suc- time, few visionary company leaders are will-

cess and GE’s decline. ing and able to maintain the revolutionary

drive over their entire tenure.

Welch’s Accomplishments and It takes a great leader to fundamentally

Driving Force question his or her mental models continu-

ously and escape the trappings of success

In spite of the managerial and personal short- more than once (emphasis added) (Markides,

comings at the end of his tenure, Welch’s 1998).

© 2006 The Author

Volume 15 Number 1 2006 Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing

CASE STUDY 83

In conclusion, the driving force of Welch’s revolution’ (Deutseher, 1954) which was

undeniable accomplishments was his will and anathema to Stalin, who wanted to consol-

ability to create a new vision of GE, to imple- idate his power by stabilizing the Soviet

ment it through a continuous revolution, to Union.

question the status quo, to dynamically mod-

ify his vision and strategy, and to propel the

company to ever higher levels of performance Acknowledgement

and success.

The author wishes to thank Lindsay Evans for

reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Notes

1 The literature on revolution is enormous. A

basic reference is the Encyclopedia of References

World History (Langer, 1968). The French

Abetti, P.A. (2001) General Electric after Jack

and Russian revolutions are analyzed by

Welch: Succession and Success? International

Crane (1957), the Mexican revolution by Journal of Technology Management, 22(7/8), 656–

Johnson (1968), the Chinese revolution by 69.

Guillermaz (1972), the Fascist revolution Aguilar, F.J., Hamermesh, R. and Brainard, C. (1981)

by De Felice (1981), and the National General Electric: Strategic Position 1981, Harvard

Socialist revolution by Bullock (1952). Business School, case 381-179.

2 The sales of large multinational corpora- Aguilar, F.J., Hamermesh, R. and Brainard, C. (1985)

tions are often compared to the GNPs of General Electric 1984, Harvard Business School,

developing countries. A better measure is case 385-315.

the value added by a company (Bartlett, Aguilar, F.J., Hamermesh, R. and Brainard, C. (1991)

General Electric: Reg Jones and Jack Welch, Harvard

Goshal, Birkinshaw, 2004).

Business School, case 9-391-144.

3 Following the example of Machiavelli Allio, R.J. (2003) The Seven Faces of Leadership, Tatu

(1515) we present the leaders as they were McGraw Hill, New Delhi.

and their actions without passing judg- Bartlett, C.A., Ghoshal, S. and Birkishaw, J.

ment. (2004) Transnational Management, 4th ed., Irwin,

4 From the Greek α′γιος = saint and γρα′ϕος = Boston.

writer, the writers of the ‘Lives of the Bartlett, C.A. and Glinka, M. (2002) GE’s Digital Rev-

Saints’ of early Christianity. olution: Redefining the E in GE, Harvard Business

5 According to Welch, Reg Jones did not School, case 9-302-001.

expect drastic changes. In fact, Jones was Bartlett, C.A. and McLean, A.N. (2004) GE’s Talent

Machine: The Making of a CEO, Harvard Business

often disappointed with Welch’s behavior

School, case 9-304-049.

starting with the coming-out party he orga- Bartlett, C.A. and Wozny, M. (2000) GE’s Two –

nized just before Welch officially became Decade Transformation: Jack Welch’s Leadership,

CEO (Welch, 2001). Although Jones had Harvard Business School, case 399-150.

doubts about the wisdom of his choice, Beam, A. (2004) Books About Schnooks, Atlantic

Jones did not interfere after retirement Monthly, November, 112–116.

(Byron, 2004). Brinton, C. (1957) The Anatomy of Revolution,

6 For instance, the ‘Novus Ordo Seclorum’ Vintage Books, New York.

(New Order of Centuries) of the American Bullock, A. (1952) Hitler – a Study in Tyranny,

revolution, as shown on one dollar bills. Odhams, London.

Byron, C. (2004) Testosterone, Inc: Tales of CEOs Gone

7 Attempts to develop a ‘GE Strategy’ under

Wild, Wiley, New York.

Reg Jones failed for three reasons: (1) the Collingwood, H. and Coutu, D.C. (2002) Jack on

task was delegated to analysts, (2) the top Jack, Harvard Business Review, 80, February, 88–94.

executives were not involved and kept Collins, T.C. and Porras, J.I. (1997) Built to Last,

changing their minds, (3) the strategy was Harper Business, New York.

top-secret, and only five executives (out of DeFelice, R. (1981) Mussolini, vols 1–5, Einaudi,

400,000 employees) had access to the doc- Turin. (In Italian).

uments. Deutscher, I. (1954) Trotsky, vols 1–3, Oxford Uni-

8 Other examples are the early Stalin era in versity Press, New York.

the Soviet Union (1927–37) and Chairman Economist (2002) Business: The Jack and Jeff Show

Loses its Luster: General Electric. The Economist,

Mao’s cultural revolution (1966–67).

363(8271) May 4, 63–65.

9 Jefferson referred to the American revolution Elderkin, K.W. and Bartlett, C.A. (1993) General Elec-

as a ‘rebellion’. tric: Jack Welch’s Second Wave, Harvard Business

10 To forestall the slackening and bureaucra- School, Case 391-248.

tization of the Soviet revolution, Trotsky GE Annual Report (2000) General Electric Com-

developed the theory of the ‘permanent pany, Fairfield, Connecticut.

© 2006 The Author

Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Volume 15 Number 1 2006

84 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

Greiner, L.E. (1972) Evolution and revolution as Slater, R. (1998) Jack Welch and the GE Way, McGraw

organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 50 Hill, New York.

(July–August), 37–46. Slater, R. (2000) The GE Way Fieldbook, McGraw Hill,

Gillermaz, J. (1972) Histoire du Parti Communiste Chi- New York.

nois, vols 1–2, Payot, Paris (in French). Schumpeter, J.A. (1932) The Theory of Economic

Guzman, M.L. (1951) La Sombra del Caudillo (The Development, Harvard University Press, Cam-

Shadow of the Chief), Compañia General de Edi- bridge, Massachusetts.

ciones, Mexico, D.F., Mexico (in Spanish). Sonnenfeld, J. (1988) The Hero’s Farewell, Oxford

Heller, R. (2001) Jack Welch, Dorling Kindersley, University Press, New York.

New York. Tuchy, N. and Charan, R. (1989) Speed, simplicity,

Heskett, J.L. (1999) GE. . . . We Bring Good Things to self-confidence: an interview with Jack Welch,

Life (A and B), Harvard Business School, cases 9- Harvard Business Review, 67, September–October,

899-162 and 9-899-163. 114–34.

Hohenberg, P. (2005) Personal Communications Tichy, M.N. and Cohen, E. (1997) The Leadership

from Paul Hohenberg, former Chair, Department Engine, Harper Business, New York.

of Economics, RPI, January 18. Tichy, M.N. and Sherman, S. (1994) Control Your

Jack Welch: General Electric’s Revolutionary (1994) Destiny or Someone Else Will, Harper Business,

Harvard Business School, case 394-065. New York.

Johnson, W.W. (1968) Heroic Mexico, Doubleday, Timmons, J. (1999) New Venture Creation, 5th ed.,

Garden City, New York. Irwin, Boston.

Jefferson, T. (1853–54) The Writings of Thomas Jeffer- Ulrich, O., Kerr, S. and Ashkenas, R. (2002) The GE

son, 9 vols, Washington, D.C. Work-out, McGraw Hill, New York.

Khanna, T. and Weber, J. (2002) General Electric Med- Useem, J. (2004) Another Boss, Another Revolution,

ical Systems, 2002, Harvard Business School, case Fortune, April 5, 112–22.

9-702-428. Von Clausewitz, K. (1830) Vom Kriege, (On War)

Langer, W.L. (1968) An Encyclopedia of World History, Berlin.

4th ed. Houghton Mifflin, Boston. Welch, J. (2001, 2003) Jack, Straight from the

Lawler, E.E. III (2002) The Folly of Forced Rankings, Gut, Warner Books, New York. (The text

Strategy and Business, 28, Third Quarter. was published in 2001, the afterword added

Lowe, J.C. (1998) Jack Welch Speaks, Wiley, New in 2003).

York. Welch, J. (2002) My Dilemma – And How I Resolved

Lowe, J. (2001) Welch, An American Icon, Wiley, New It, Wall Street Journal on Line, Sept. 16 (Reprinted

York. in Welch 2001, 2003).

Machiavelli, N. (1515) Il Principe (The Prince), MS,

Florence.

Malaparte, C. (1931) Technique du Coup d’ Etat (Tech-

nique of the Coup d’Etat) Grasset, Paris (in

French).

Malwight, T.W. and Aguilar, F.J. (1990) GE-Prepar- Pier A. Abetti (abettp@rpi.edu) holds a

ing for the 1990s, Harvard Business School, case 9- Ph.D. degree in Electrical Engineering from

390-091. Illinois Institute of Technology. Prior to join-

Markides, C. (1998) Strategic Innovation in Estab- ing Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1982,

lished Companies, Sloan Management Review, as Professor in the Lally School of Manage-

Spring, 31–42. ment and Technology, he worked 32 years

Moore, P.L. (2000) The Man Who Would Be Welch, for the General Electric Company (USA).

Business Week, December 11, 56–59. He was manager of the Electrical and Infor-

Murray, M., Cole, J., Deogun, W. and Pasztor, A. mation Advance Technology Laboratories

(2000) On eve of retirement, Jack Welch decided and manager of General Electric’s Europe

to stick around GE a bit, Wall Street Journal, 23 Strategic Planning Operation. He presently

December. teaches management of technology and

O’Boyle, T. (1998) At Any Cost: Jack Welch and technological entrepreneurship courses in

the Pursuit of Profits, Random House, New the USA, Finland, and Tunisia. Author of

York. two books and more than 150 technical and

Orecklin, M. (2002) Too Close for Comfort, Time, management papers in five languages, he

March 18, 65. was the recipient of the 1993 Kaufman

Slater, R. (1993) The New GE, Irwin, Burr Ridge, Foundation Award as University Entrepre-

Illinois. neurship Professor of the Year.

Slater, R. (1996) Get Better or Get Beaten, McGraw

Hill, New York.

© 2006 The Author

Volume 15 Number 1 2006 Journal compilation © 2006 Blackwell Publishing

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Jack Welch PaperDokument7 SeitenJack Welch Papercomela1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jack WelchDokument7 SeitenJack WelchShobhit RawatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jmra 4 (4) 183-185 PDFDokument3 SeitenJmra 4 (4) 183-185 PDFacfilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bank One GRP-B Repaired)Dokument46 SeitenBank One GRP-B Repaired)Nusrat Sababa RahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- WACC Professional Management GudanceDokument17 SeitenWACC Professional Management GudanceMagnatica TraducoesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 3Dokument7 SeitenAssignment 3Prasansha ShresthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LDR 531 - WK2 Tyco FailureDokument6 SeitenLDR 531 - WK2 Tyco Failuregidian82Noch keine Bewertungen

- Foreign Investment and Ethics How To Contribute To Social Responsibility by Doing Business in Less-Developed CountriesDokument17 SeitenForeign Investment and Ethics How To Contribute To Social Responsibility by Doing Business in Less-Developed CountriesAnand SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group Project Case StudyDokument38 SeitenGroup Project Case Studyapi-435962567Noch keine Bewertungen

- Richard Scrushy: The Rise and Fall of The "King of Health Care"Dokument20 SeitenRichard Scrushy: The Rise and Fall of The "King of Health Care"kneal82Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pricing of F&FDokument39 SeitenPricing of F&Fravinder_gudikandulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ogl 300 Leadership Theory Application EssayDokument8 SeitenOgl 300 Leadership Theory Application Essayapi-322248033Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jack Welch's Leadership: GE's Two Decade TransformationDokument24 SeitenJack Welch's Leadership: GE's Two Decade TransformationKishlaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weaa Leadership Theory EvaluationDokument7 SeitenWeaa Leadership Theory Evaluationapi-538756701Noch keine Bewertungen

- CalvetaDokument11 SeitenCalvetaAnonymous 3Pk0Oj100% (1)

- APO Group-6 Calveta Dining Services IncDokument10 SeitenAPO Group-6 Calveta Dining Services IncKartik SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- J&J Chandrashekhar - DocxqeDokument74 SeitenJ&J Chandrashekhar - DocxqeManova Kumar100% (1)

- Haier Group Company: MarketbusterDokument7 SeitenHaier Group Company: MarketbusterstudyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CemexDokument2 SeitenCemexBearBDSMNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE - 2decades of Transformation - Rollno 21Dokument3 SeitenGE - 2decades of Transformation - Rollno 21aruntce_kumar9286Noch keine Bewertungen

- GE S Two-Decade TransformationDokument10 SeitenGE S Two-Decade TransformationatefzouariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment On HyfluxDokument11 SeitenAssignment On HyfluxJosephiney92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study: The Rise & Fall of Blackberry: This Study Resource WasDokument5 SeitenCase Study: The Rise & Fall of Blackberry: This Study Resource WasShraddha SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dell's Working Capital ManagementDokument12 SeitenDell's Working Capital ManagementShashank Kanodia100% (2)

- Case Session18Dokument3 SeitenCase Session18Raju SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Diversity at Cityside Financial ServicesDokument8 SeitenManaging Diversity at Cityside Financial ServicesMayur AlgundeNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE - Two Decades of Transformation Under Jack WelchDokument18 SeitenGE - Two Decades of Transformation Under Jack WelchPurnendu SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE Case StudyDokument9 SeitenGE Case StudyAshwath RamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rondell Team PaperDokument14 SeitenRondell Team PaperSandeep KuberkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case of HyfluxDokument6 SeitenCase of HyfluxMai NganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases SkodewDokument6 SeitenCases SkodewAnkit CNoch keine Bewertungen

- National-Renewable EnergyDokument26 SeitenNational-Renewable EnergyBALLB BATCH-1100% (1)

- GE AnalysisDokument14 SeitenGE Analysisaby0% (1)

- ICRISATDokument17 SeitenICRISATTanjim Lampard IslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- OracleDokument2 SeitenOracleaj4u7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Citibank Performance Evaluation Case StudyDokument10 SeitenCitibank Performance Evaluation Case StudyPrashant KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM Final Version AnDokument12 SeitenHRM Final Version AnAhmed NounouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of The CaseDokument40 SeitenSummary of The Casepriyaa03100% (1)

- Case Study Analysis of Nuclear Tube Assembly Room (A)Dokument7 SeitenCase Study Analysis of Nuclear Tube Assembly Room (A)Justin HuynhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dell Working CapitalDokument12 SeitenDell Working Capitalsankul50% (1)

- Case Study - Hyflux NewaterDokument6 SeitenCase Study - Hyflux NewaterAnshita SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- BCG Economic Value Added Oct1996Dokument2 SeitenBCG Economic Value Added Oct1996anahata2014Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case SummaryDokument1 SeiteCase SummaryZainab IrfanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyflux Limited: Capital Structure and Financial DistressDokument11 SeitenHyflux Limited: Capital Structure and Financial DistressMizanur RahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hindustan Petroleum Corporation LTDDokument7 SeitenHindustan Petroleum Corporation LTDSaurabh Sharma100% (1)

- APO Group-3 Calveta Dining ServicesDokument11 SeitenAPO Group-3 Calveta Dining ServicesKartik SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Electric Case Study: Succession Planning at GE: Powerpoint Templates Powerpoint TemplatesDokument14 SeitenGeneral Electric Case Study: Succession Planning at GE: Powerpoint Templates Powerpoint TemplatesPankaj Singh PariharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leadership ArticleReview PraneshDokument5 SeitenLeadership ArticleReview PraneshAshutosh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge and Jack Welch'S Leadership - A Case Study Approach: - Praveen AdariDokument10 SeitenGe and Jack Welch'S Leadership - A Case Study Approach: - Praveen AdarivasudhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leadership Change in DisneyDokument6 SeitenLeadership Change in DisneyumarzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonoco Case StudyDokument2 SeitenSonoco Case StudyMohanrasu GovindanNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE's Two Decade Transformation: Jack Welch's LeadershipDokument2 SeitenGE's Two Decade Transformation: Jack Welch's LeadershipJenny SchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zappos Case Study - 2Dokument15 SeitenZappos Case Study - 2GauravTiwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mount Everest 1996Dokument6 SeitenMount Everest 1996Suraj GaikwadNoch keine Bewertungen

- AssignmentDokument11 SeitenAssignmentHarshita JaiswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design For The Next Generation: Incorporating Cradle-to-Cradle Design Into Herman Miller ProductsDokument18 SeitenDesign For The Next Generation: Incorporating Cradle-to-Cradle Design Into Herman Miller ProductsJesús Rafael Páez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge S Two E28093 Decade TransformationDokument25 SeitenGe S Two E28093 Decade Transformationgir_8100% (1)

- General Electric After Jack Welch: Succession and Success?: Pier A. AbettiDokument14 SeitenGeneral Electric After Jack Welch: Succession and Success?: Pier A. AbettiKimberly Latorza0% (1)

- Case 1 - Jack Welch and Jeffrey Immelt Continuity and Change in Strategy, Style, and Culture at GEDokument24 SeitenCase 1 - Jack Welch and Jeffrey Immelt Continuity and Change in Strategy, Style, and Culture at GEvijayselvarajNoch keine Bewertungen

- GEDokument18 SeitenGEydy92611Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kingdom of Thailand: Cross Cultural Management Project WorkDokument51 SeitenKingdom of Thailand: Cross Cultural Management Project WorkaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thai Dining EtiquetteDokument13 SeitenThai Dining EtiquetteaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1Dokument7 SeitenChapter 1aswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aswnny2 PDFDokument21 SeitenAswnny2 PDFaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aswny 3 PDFDokument17 SeitenAswny 3 PDFaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- CertificateDokument20 SeitenCertificateaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intrinsic PDFDokument10 SeitenIntrinsic PDFaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAFTA: Few Observations: Shahid Ahmed, PH.D Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Jamia Millia Islamia New DelhiDokument11 SeitenSAFTA: Few Observations: Shahid Ahmed, PH.D Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Jamia Millia Islamia New DelhiaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Management Case StudyDokument2 SeitenRisk Management Case StudyaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- EffectsDokument28 SeitenEffectsaswanysankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cbjesccq14 PDFDokument9 SeitenCbjesccq14 PDFHilsa Das Hilsa DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- D893Dokument5 SeitenD893rpajaro75Noch keine Bewertungen

- Noches Siniestras en Mar Del Plata PDF Nsemdp11 10 - 5a90ee781723dde9a0acb009 PDFDokument2 SeitenNoches Siniestras en Mar Del Plata PDF Nsemdp11 10 - 5a90ee781723dde9a0acb009 PDFPachii Rnr50% (2)

- Collections Management Policy: Approved by The Board of Trustees On March 2, 2021Dokument21 SeitenCollections Management Policy: Approved by The Board of Trustees On March 2, 2021ﺗﺴﻨﻴﻢ بن مهيديNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9Dokument24 SeitenChapter 9Jiaway TehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shashank Sasane 02Dokument1 SeiteShashank Sasane 02Pratik BajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIR Vs Gen FoodsDokument12 SeitenCIR Vs Gen FoodsOlivia JaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ortfolio Assessment: Carlo Magno, PHD Lasallian Institute For Development and Educational ResearchDokument26 SeitenOrtfolio Assessment: Carlo Magno, PHD Lasallian Institute For Development and Educational ResearchGuide DoctorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marathon TX 1Dokument12 SeitenMarathon TX 1alexandruyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Export AssistanceDokument15 SeitenExport AssistanceGaurav AgrawalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sectoral AnalysisDokument416 SeitenSectoral AnalysisNICOLE EDRALINNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gap Analysis: Dr. N. BhaskaranDokument4 SeitenGap Analysis: Dr. N. BhaskaranNagarajan BhaskaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1900 - John Burnet - The Ethics of AristotleDokument593 Seiten1900 - John Burnet - The Ethics of AristotleRobertoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mis in WalmartDokument36 SeitenMis in WalmartNupur Vashishta93% (14)

- Marketing Research ProposalDokument42 SeitenMarketing Research ProposalFahmida HaqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migracion WAS8Dokument472 SeitenMigracion WAS8ikronos0Noch keine Bewertungen

- DAC 6000 4.x - System Backup and Restore Procedure Tech TipDokument8 SeitenDAC 6000 4.x - System Backup and Restore Procedure Tech TipIgnacio Muñoz ValenzuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Po NPN 5053104338 KrisbowDokument2 SeitenPo NPN 5053104338 Krisbowryan vernando manikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metgraf Data SheetDokument1 SeiteMetgraf Data SheetFlorin BargaoanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- PCX 160 (Ultimate Excellence) : Honda Premium Matic Day (HPMD) #Cari - AmanDokument4 SeitenPCX 160 (Ultimate Excellence) : Honda Premium Matic Day (HPMD) #Cari - AmanMUHAMMAD RIDHO AZHARNoch keine Bewertungen

- InvoisDokument54 SeitenInvoisAnonymous Ff1qA9RLCNoch keine Bewertungen

- GSM Modem PDFDokument2 SeitenGSM Modem PDFFalling SkiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Revenue CycleDokument36 SeitenThe Revenue CycleGerlyn Dasalla ClaorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bombas KSBDokument50 SeitenBombas KSBAngs TazNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR Narendra Kumar Assistant ProfessorDokument16 SeitenDR Narendra Kumar Assistant ProfessorAbdiweli AbubakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Csec Poa June 2015 p2Dokument33 SeitenCsec Poa June 2015 p2goseinvarunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carti Vertical Flight PDFDokument214 SeitenCarti Vertical Flight PDFsaitoc0% (1)

- Accord - DA-XDokument95 SeitenAccord - DA-XPeter TurnšekNoch keine Bewertungen

- En 13369 PDFDokument76 SeitenEn 13369 PDFTemur Lomidze100% (2)

- Type LSG-P: Rectangular Sight Glass FittingsDokument1 SeiteType LSG-P: Rectangular Sight Glass Fittingsגרבר פליקסNoch keine Bewertungen