Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Excerpt From "Mobituaries" by Mo Rocca

Hochgeladen von

OnPointRadioOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Excerpt From "Mobituaries" by Mo Rocca

Hochgeladen von

OnPointRadioCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

6P_Rocca_Mobituaries_35560.

indd 282 9/6/19 11:09 AM

M

y family had a station wagon for a couple of years in the early 1970s. But

I was only three or four at the time so I can barely remember it. It was

yellow, I think, or maybe it was cream colored. Was it a Chevy? What

I do know is that one afternoon my mother put my brother in the back seat after a

doctor’s appointment and the car started rolling backward in the parking lot. À la

Angie Dickinson in Police Woman she had to jump into the front seat and pull the

emergency brake. This was reason enough for my father to trade in the station wagon

for an Impala sedan soon after. And just like that, the one thing that made us like

TV’s Brady family—and who were more all-American than the Bradys?—was gone.

For a few decades, from the midfifties to the mideighties, station wagons like

the Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser, the Chrysler Town and Country, and the Ford Coun-

try Squire were as central to the American Dream as the white picket fence and the

basketball hoop in the driveway. These were the quintessential family cars. (FYI,

the Bradys had at least two different station wagons, both of them Plymouth Sat-

ellites.) And the bigger the wagon, the cooler the family. By the 1970s the Ford

Country Squire was a nearly nineteen-foot-long behemoth and got a whopping

eight to ten miles to the gallon. You could cram four or five kids into the back seat,

but that’s not where I wanted to be.

Anytime I was lucky enough to ride in one (and I’m sure I befriended some

kids because their families had station wagons) I headed straight for the way back.

With the seats folded down. The freedom. The danger! I loved being thrown against

the side when the car turned, all the better when other kids were back there, all of

us ricocheting off each other after a pizza party at Shakey’s. Riding in the way back

283

6P_Rocca_Mobituaries_35560.indd 283 9/6/19 11:09 AM

mobituaries

gave me the same out-of-control thrill I got from roller coasters. Related: I used to

fantasize about climbing into the dryer so I could just spin and spin. It’s probably a

good thing I didn’t figure out how to turn the dryer on from the inside.

What gave these cars an extra flair was the vinyl appliqué wood-grain paneling.

It made it feel like a house on wheels. The paneling was a throwback to the earliest

station wagons, which were made mostly of wood. These wagons were DIY affairs.

The customer would buy the chassis of, say, a Model T, then order the wood body

from a coachbuilder or hire a carpenter to make it and bolt it on. “It was just much

lighter and easier to build the body out of wood,” says my friend Matt Anderson,

curator of transportation at the Henry Ford Museum. “The technology just didn’t

exist at that time to build a large body out of steel.” By the 1930s these vehicles—and

many were beauties—were known as “Woodies.”

The earliest station wagons were used on farms or as delivery vehicles, and to

transport passengers between railroad stations and hotels. That’s how the vehicle

got the name “station wagon.” (This is the kind of factoid I love.) By the time the

baby boom hit, the station wagon had caught on with families. “The first real mod-

ern station wagon is the 1949 Plymouth Suburban,” says Matt. “It’s got an all-steel

body. The name itself tells you how that vehicle was marketed. The rise of the sub-

urbs was a big factor in the adoption of the station wagon.”

Now, it’s true that station wagons were an absolute nightmare for any teenager

learning to parallel park. They were larger than the standard parking space, the

sight lines were miserable, and I’m pretty sure that rear defrosters hadn’t been in-

vented yet. And of course they were dangerous. The way back was a death chamber.

(For the more safety-conscious there was a rear-facing fold-up seat, introduced by

Chrysler in 1957. It had seat belts, not that you could ever find them. It also had the

benefit that someone sitting back there could call out whenever luggage strapped to

the roof rack came free and tumbled out onto the highway.)

By the early 1980s the family station wagon was already beginning to acquire

value as kitsch. We know this for a fact because in 1983 Warner Bros. released

284

6P_Rocca_Mobituaries_35560.indd 284 9/6/19 11:09 AM

death of a leviathan

Harold Ramis’s National Lampoon’s Vacation. The true star of that movie is not the

bumbling Chevy Chase but the “Wagon Queen Family Truckster,” an enormous

hearse-like vehicle that is gradually gutted over the course of the film due to a com-

bination of vandalism and incompetent driving.

But as Vacation was “celebrating” the station wagon, its demise was looming.

There were warning signs. The oil crisis of 1973 made fuel efficiency a priority for

consumers. The ingenuity of Japanese engineering was making it harder and harder

to stay loyal to American cars that handled poorly and seemed in constant need

of repair. Then came what car journalist Amos Kwon has called “the testosterone-

robbing minivan,” which Lee Iacocca introduced at Chrysler in 1983. With better

fuel economy, more headroom, and, best of all, a sliding side door, the minivan was

a hit among practical-minded carpooling soccer moms. Mandatory car seats rang

the death knell of the “way back.”

The station wagon belonged to the Golden Age of the highway, the new sys-

tem of interstates built by Eisenhower and Kennedy. Up through the eighties, that

highway system represented nothing less than freedom itself, flight from dreary

routines of city and suburb, access to all our nation’s great beauty and natural at-

tractions. But then, with traffic and suburban sprawl getting worse and worse, those

endless highways were no longer our means of escape. They became another part of

what we needed to escape from.

And so after the minivan, we fell in love with the four-wheel-drive SUV, the

kind that—at least in the commercials—could drive right over a guardrail, plow

through a rocky riverbed, and scale a craggy mountain at forty-five degrees. Maybe

it was the renewed nuclear fears of the eighties, or just a vague sense of loom-

ing catastrophe, but suddenly we all needed military-grade vehicles of our own—

something that could get traction on a glacier and stand up to machine-gun fire if

needed. When the next blizzard, hurricane, or wildfire hit, local and state authori-

ties weren’t going to save us.

In 2011 Volvo announced that it would stop selling station wagons in the

285

6P_Rocca_Mobituaries_35560.indd 285 9/6/19 11:09 AM

mobituaries

United States. Sales had dropped from 40,000 in 1999 to 480 in 2010. Auto buffs

immediately began to mourn its passing. But the truth is that by 2011 the station

wagon was already long dead. The Volvo wagon of the nineties was no more a real

station wagon than a barn swallow is a real dinosaur. At best, it was a stunted de-

scendant of the magnificent monsters that roamed American highways during the

Late Cretaceous period of American automotive history.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of auto safety. But boy, if someone gave me the

keys to a 1979 Ford Country Squire, I’d be sorely tempted to take a week off and ride

that beast to the Grand Canyon.

286

6P_Rocca_Mobituaries_35560.indd 286 9/6/19 11:09 AM

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Mega Kyb Monroe Gabriel Shock Absorber Cross ReferenceDokument6 SeitenMega Kyb Monroe Gabriel Shock Absorber Cross Referencesapu11jagat58550% (4)

- Freelander 2010 Owners Manual PDFDokument207 SeitenFreelander 2010 Owners Manual PDFJosiel BrunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Foster Wallace, The View From The Midwest - Rolling StoneDokument12 SeitenDavid Foster Wallace, The View From The Midwest - Rolling Stoneioio1469Noch keine Bewertungen

- DIECI AGRISTAR MANUAL AXH1148 - UK - Ed02 - Agri SIRZ (Max Power Star)Dokument276 SeitenDIECI AGRISTAR MANUAL AXH1148 - UK - Ed02 - Agri SIRZ (Max Power Star)EDUARDOLOPEZMONTES75% (4)

- McQuade AFW Excerpt For NPR On PointDokument5 SeitenMcQuade AFW Excerpt For NPR On PointOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Howo Tipper Truck 6x4 371HP PDFDokument2 SeitenHowo Tipper Truck 6x4 371HP PDFIbrahim Fadhl KalajengkingNoch keine Bewertungen

- American PostmodernismDokument18 SeitenAmerican PostmodernismAneta StejskalovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Buried Giant LitChartDokument57 SeitenThe Buried Giant LitChartJanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Don Lelillo's Novels and Tibetan BuddhismDokument26 SeitenDon Lelillo's Novels and Tibetan BuddhismShilpi SenguptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RealWork TheFirstMysteryofMastery 13-21Dokument5 SeitenRealWork TheFirstMysteryofMastery 13-21OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sitema Hicas PDFDokument2 SeitenSitema Hicas PDFAlejandroO.VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mercedes Benz E200 2017 ManualDokument470 SeitenMercedes Benz E200 2017 ManualYousuf_Alqeisi100% (1)

- XML6807J23-秘鲁-7160896 - 2016Dokument216 SeitenXML6807J23-秘鲁-7160896 - 2016Adelmo Hernandez Hernandez100% (2)

- 32 Ford CatalogDokument64 Seiten32 Ford CatalogJavier EscuderoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Balloon - Donald BarthelmeDokument6 SeitenThe Balloon - Donald Barthelmetrond_trondsen1774100% (2)

- Mission at Tenth Volume 5Dokument139 SeitenMission at Tenth Volume 5California Institute of Integral Studies100% (1)

- Brecht TimelineDokument3 SeitenBrecht Timelineapi-281813793Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Walking Shadow: A Promethean Scientific RomanceVon EverandThe Walking Shadow: A Promethean Scientific RomanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Card - A Story of Adventure in the Five TownsVon EverandThe Card - A Story of Adventure in the Five TownsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (6)

- Labyrinth: BolanoDokument13 SeitenLabyrinth: BolanojgswanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Bee Stung Me - George SaundersDokument21 SeitenA Bee Stung Me - George SaundersLaura Ordonez100% (1)

- Lonely Are The Brave (1962)Dokument3 SeitenLonely Are The Brave (1962)Jean ValjeanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The First Men in The MoonDokument127 SeitenThe First Men in The MoonThuvarakan SelvanathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 An Interview With Manuel PuigDokument8 Seiten4 An Interview With Manuel Puigapi-26422813Noch keine Bewertungen

- Being Busted - Leslie A FiedlerDokument264 SeitenBeing Busted - Leslie A Fiedlerdoctorjames_44100% (1)

- A Postcolonial Reading of Some of Saul Bellow's Literary WorksDokument120 SeitenA Postcolonial Reading of Some of Saul Bellow's Literary WorksMohammad HayatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alexander Theroux Answers Charge of Plagiarism in Primary Colors - San Diego ReaderDokument21 SeitenAlexander Theroux Answers Charge of Plagiarism in Primary Colors - San Diego ReaderPahomy4100% (1)

- Paradise Lost - John MiltonDokument213 SeitenParadise Lost - John MiltonMohamed FathyNoch keine Bewertungen

- EssayDokument18 SeitenEssaypriteegandhanaik_377Noch keine Bewertungen

- Humboldt'S Gift - Saul Bellow'S Freudian Slip of The TongueDokument3 SeitenHumboldt'S Gift - Saul Bellow'S Freudian Slip of The Tonguealina barbuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heart of Darkness Related To The Island of Dr. MoreauDokument11 SeitenHeart of Darkness Related To The Island of Dr. Moreauxcrunner9811Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jaime Clarke - Conversations With Jonathan LethemDokument216 SeitenJaime Clarke - Conversations With Jonathan LethemMaxih72Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lady Windermere's FanDokument76 SeitenLady Windermere's FanTarmac NomadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Off The MapDokument75 SeitenOff The Mapmdemon9991100% (2)

- Old Man in a Baseball Cap: A Memoir of World War IIVon EverandOld Man in a Baseball Cap: A Memoir of World War IIBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (9)

- Anton Chekhov: Letters, Diary, Reminiscences & Biography: A Collection of Autobiographical WritingsVon EverandAnton Chekhov: Letters, Diary, Reminiscences & Biography: A Collection of Autobiographical WritingsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rediscovery, Volume 2: Science Fiction by Women (1953-1957)Von EverandRediscovery, Volume 2: Science Fiction by Women (1953-1957)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ezra Pound ManuscriptsDokument14 SeitenEzra Pound ManuscriptsdomaninaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Billy ChildishDokument3 SeitenBilly ChildishAleksandar KojicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilhelm Meister'S Apprenticeship Reference Guide To World Literature, 3 EditionDokument2 SeitenWilhelm Meister'S Apprenticeship Reference Guide To World Literature, 3 EditionAbhisek Upadhyay100% (1)

- Shep's Army: Bummers, Blisters and BoondogglesVon EverandShep's Army: Bummers, Blisters and BoondogglesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (8)

- New Stories from the MidwestVon EverandNew Stories from the MidwestJason Lee BrownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brodsky, Joseph - Discovery (FSG, 1999)Dokument23 SeitenBrodsky, Joseph - Discovery (FSG, 1999)Isaac JarquínNoch keine Bewertungen

- Three Somebodies: Plays about Notorious Dissidents: SCUM | Jack the Rapper | Art Was HereVon EverandThree Somebodies: Plays about Notorious Dissidents: SCUM | Jack the Rapper | Art Was HereNoch keine Bewertungen

- When Brecher Met HastingsDokument7 SeitenWhen Brecher Met Hastings98814002aNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1956 Lucky Starr and The Big Sun of MercuryDokument45 Seiten1956 Lucky Starr and The Big Sun of MercuryluciusthorNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dusty Bookcase: A Journey Through Canada's Forgotten, Neglected and Suppressed WritingVon EverandThe Dusty Bookcase: A Journey Through Canada's Forgotten, Neglected and Suppressed WritingNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Town by William FaulknerDokument13 SeitenThe Town by William FaulknerJacinda33% (3)

- What It Might Be Like To Live in Viriconium: Article by Author M John HarrisonDokument2 SeitenWhat It Might Be Like To Live in Viriconium: Article by Author M John HarrisonJames DouglasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kent Jones CriterionDokument40 SeitenKent Jones Criterionyahooyahooyahoo1126Noch keine Bewertungen

- Study Guide: John Ford (1956) : The SearchersDokument11 SeitenStudy Guide: John Ford (1956) : The SearchersG HNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intro Excerpt How Elites Ate The Social Justice MovementDokument11 SeitenIntro Excerpt How Elites Ate The Social Justice MovementOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Alone Chapter Copies - Becoming Ancestor & Epiloge (External)Dokument5 SeitenNever Alone Chapter Copies - Becoming Ancestor & Epiloge (External)OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Braidwood V Becerra LawsuitDokument38 SeitenBraidwood V Becerra LawsuitOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 AMTLTDokument11 SeitenChapter 1 AMTLTOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9-11 Pages From NineBlackRobes 9780063052789 FINAL MER1230 CC21 (002) WM PDFDokument3 Seiten9-11 Pages From NineBlackRobes 9780063052789 FINAL MER1230 CC21 (002) WM PDFOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Like Literally Dude - Here and Now ExcerptDokument5 SeitenLike Literally Dude - Here and Now ExcerptOnPointRadio100% (1)

- Adapted From 'Uniting America' by Peter ShinkleDokument5 SeitenAdapted From 'Uniting America' by Peter ShinkleOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intro From If I Betray These WordsDokument22 SeitenIntro From If I Betray These WordsOnPointRadio100% (2)

- Traffic FINAL Pages1-4Dokument4 SeitenTraffic FINAL Pages1-4OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Short Write-Up On A World of InsecurityDokument1 SeiteA Short Write-Up On A World of InsecurityOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Stranger in Your Own City Chapter 1Dokument8 SeitenA Stranger in Your Own City Chapter 1OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Op-Ed by Steve HassanDokument2 SeitenOp-Ed by Steve HassanOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Escape PrologueDokument5 SeitenThe Great Escape PrologueOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Battle For Your Brain Excerpt 124-129Dokument6 SeitenThe Battle For Your Brain Excerpt 124-129OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- PbA Non-Exclusive ExcerptDokument3 SeitenPbA Non-Exclusive ExcerptOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time To Think Extract - On Point - HB2Dokument3 SeitenTime To Think Extract - On Point - HB2OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- WICF SampleDokument7 SeitenWICF SampleOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction Excerpt For Here and Now - Non ExclusiveDokument9 SeitenIntroduction Excerpt For Here and Now - Non ExclusiveOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excerpt For Here & Now - Chapter 2 - AminaDokument15 SeitenExcerpt For Here & Now - Chapter 2 - AminaOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Big Myth - Intro - 1500 Words EditedDokument3 SeitenThe Big Myth - Intro - 1500 Words EditedOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Excerpt - Here&NowDokument8 SeitenChapter 1 Excerpt - Here&NowOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speak Up Excerpt FightLikeAMother-WATTSDokument3 SeitenSpeak Up Excerpt FightLikeAMother-WATTSOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doe-V-Twitter 1stAmndComplaint Filed 040721Dokument55 SeitenDoe-V-Twitter 1stAmndComplaint Filed 040721OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- MY SELMA - Willie Mae Brown - NPR ExcerptDokument3 SeitenMY SELMA - Willie Mae Brown - NPR ExcerptOnPointRadio100% (1)

- Pages From The People's Tongue CORRECTED PROOFSDokument8 SeitenPages From The People's Tongue CORRECTED PROOFSOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8BillionAndCounting 1-28Dokument28 Seiten8BillionAndCounting 1-28OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Fight of His Life Chapter 1Dokument5 SeitenThe Fight of His Life Chapter 1OnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schlesinger - Great Money Reset ExcerptDokument3 SeitenSchlesinger - Great Money Reset ExcerptOnPointRadioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terex 820 Backhoe Loader TechSheetDokument2 SeitenTerex 820 Backhoe Loader TechSheetCostin Bizon100% (2)

- HIDROMEK MG460 - SPEC SHEETvsfdsgDokument2 SeitenHIDROMEK MG460 - SPEC SHEETvsfdsggaurav champawatNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020 Civic Sedan Trim WalkDokument4 Seiten2020 Civic Sedan Trim WalkKevin YoungNoch keine Bewertungen

- CarExamer Announces Free Used Car ChecklistDokument4 SeitenCarExamer Announces Free Used Car ChecklistPR.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- JLG G9-43A SN 0160048658 To Present Telehandler Parts ManualDokument478 SeitenJLG G9-43A SN 0160048658 To Present Telehandler Parts ManualCharle Robles Bocanegra67% (3)

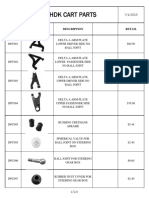

- HDK Spares PDFDokument62 SeitenHDK Spares PDFBala Murugan100% (1)

- Eurotech Iveco AustraliaDokument8 SeitenEurotech Iveco AustraliaDIONYBLINKNoch keine Bewertungen

- SDLG B877F Brochure PDFDokument8 SeitenSDLG B877F Brochure PDFAL NOOR GROUPNoch keine Bewertungen

- N122 Text 2Dokument6 SeitenN122 Text 2doodoobuttfartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peugeot 407: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDokument12 SeitenPeugeot 407: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchKhaled FatnassiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Behaviour For Sedan and Luxury Cars - Kartik Jain and Jaswant Singh PDFDokument16 SeitenConsumer Behaviour For Sedan and Luxury Cars - Kartik Jain and Jaswant Singh PDFkartik jain100% (1)

- Megane Rs Brochure March2019 PDFDokument44 SeitenMegane Rs Brochure March2019 PDFTõnis TranzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renault Trucks D Distribution Range Uk 2016Dokument24 SeitenRenault Trucks D Distribution Range Uk 2016AliNoch keine Bewertungen

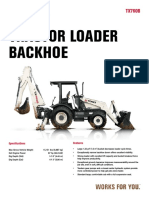

- Tractor Loader Backhoe: Specifications FeaturesDokument4 SeitenTractor Loader Backhoe: Specifications FeaturesSebastián Heriberto Campos Arenas100% (1)

- 2020 Ford Lincoln BrochureDokument13 Seiten2020 Ford Lincoln BrochurepsychonomyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Currently Dismantling - Manitowoc Tms900e (7/27/20)Dokument1.190 SeitenCurrently Dismantling - Manitowoc Tms900e (7/27/20)All Parts Inc.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pro Comp Suspension: PN# 62170 1998-2010 Ford Ranger 4wd & Edge 2wd/4wd Torsion Bar Key KitDokument8 SeitenPro Comp Suspension: PN# 62170 1998-2010 Ford Ranger 4wd & Edge 2wd/4wd Torsion Bar Key KitomarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ford EcoSportDokument15 SeitenFord EcoSportknight riderNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1095 Truck Technical Specification For Procurement of TruckDokument2 Seiten1095 Truck Technical Specification For Procurement of TruckPradeep AcharyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 620e630e635e 1.6 0516Dokument4 Seiten620e630e635e 1.6 0516iodakortNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 Audi Q5 BrochureDokument13 Seiten2019 Audi Q5 BrochureMuhammad HamzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Astra H BrochureDokument72 SeitenAstra H BrochureSeanGordonTysonNoch keine Bewertungen