Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ar65vs PDF

Hochgeladen von

Shantianth KumbharOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ar65vs PDF

Hochgeladen von

Shantianth KumbharCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 870

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

Vastu Purusha Mandala - A Human Ecological

Framework for Designing Living Environments

Jayadevi Venugopal

Abstract--- This paper aims to present ‘vastu purusha building activity and the „Purusa‟ or the macrocosm, the

mandala’(VPM), a symbolic diagram used in the indigenous essence of all things. Similarly, Ayurveda (indigenous medical

system of Indian architecture as a human ecologic frame work science of India) is defined as the self-awareness of all living

for designing living environments. The article begins with an beings about their relationship with the environment (Dimitrov

attempt to provide a working definition for the ‘living & Naess, 2005, p. 93).

environment’ based on the theories developed by Rapoport

This article begins with an attempt to provide a working

(2005) and Lawrence (2001). It then discusses the symbolism

definition for the „living environment‟ based on the theories

and the human ecologic significance of VPM. This is

developed by Rapoport (2005) and Lawrence (2001). It then

substantiated through the works of Kramrisch (1976), Moore discusses the symbolism and the human ecologic significance

(1989), Shukla (1996) and Chakrabarthi (1998). Some recent of VPM. This is substantiated through the works of Kramrisch

papers on Vastu Shastra are also examined. Furthermore,

(1976), Moore (1989), Shukla (1996) and Chakrabarthi

VPM is compared with the livability guidelines developed for

(1998). Some recent papers on Vastu Shastra are also

high-rise living by the Centre for Subtropical Design,

examined. Furthermore, VPM is compared with the livability

Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. A guidelines developed for high-rise living by the Centre for

meaningful interpretation of vastushastra which is free from Subtropical Design, Queensland University of Technology,

mysticism and symbolism is proffered through this paper.

Brisbane, Australia.

Keywords--- Vastu Purusha Mandala

II. TOWARDS A HUMAN ECOLOGIC DEFINITION FOR

LIVING ENVIRONMENT

I. INTRODUCTION Ecology is a term that is customarily used as an indicative

of „sustainability‟ in the normative theory of architecture (Orr,

E COLOGY is the branch of science that deals with the

interrelationship between organisms and

surroundings. The term ecology is derived from the Greek

their

2002, 2007; Tanzer & Longoria, 2007; Van der Ryn &

Cowan, 1996; Williams, 2007). Similarly, human ecology was

also discussed initially with the normative theory in

words “olikos‟ and “logos” that means science of the habitat.

architecture by Soleri (1969) through his works on

Human ecology is a derivation of ecology, first used by Robert

„Archology‟. It is only recently that aspects of human ecology

Park and Ernest Burgess. They defined human ecology as the

are studied as part of an explanatory theory of architecture by

study of the spatial and temporal relations of human beings as

scholars like Lawrence (2003) and Rapoport (2010). The

affected by selective, distributive and accommodative forces

following review of the existing literature seems to denote that

of the environment (Park, Burgess, & McKenzie, 1925, p. 63).

an explanatory theory of architecture, based on human

A more recent definition for human ecology by Lawrence

ecology, is a new point of departure.

(2003) says that it refers to the dynamic interrelationships

between human populations and the physical, biotic, cultural Lawrence (2003, p. 34) states that the interrelationship

and social characteristics of their environment and the between people and environment is not only spatial but also

biosphere (Lawrence, 2001, p. 675). Human ecology is biological and cultural and that these interrelationships are

interpreted in various ways under different disciplines and subject to change over time. Figure 1 shows the framework of

applied fields such as anthropology, geography, psychology, human ecology perspective developed by Lawrence (2003, p.

sociology, urban design, architecture and planning (Bruhn, 33). He argues that human settlements should be reinterpreted

1974; Nauser & Steiner, 2002). in order to make architecture more sensitive to the human

ecology of cities, regions as well as the biosphere. Lawrence‟s

While ecology is defined as a branch of science in today‟s

framework brings together all the factors that the natural and

knowledge system, it is an imperative component that

social scientist have been conferring separately such as biotic,

encompasses all branches of the ancient Vedic knowledge

abiotic and cultural. He does not project this model as a

system of India. Kramrisch (1976) points out that in the

complete one but states that it is a superior representation of

diagram of „vastu purusa‟, a communication is established

human ecology when compared to previous interventions

between man („purusa‟) or the microcosm as the patron of the

(Lawrence, 2001, p. 692). He argues that this framework

considers the whole system as the unit of study and that it is a

Jayadevi Venugopal , PhD Student, School of Design, Creative synchronic representation of human eco-system that is open

Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, and linked to others. However, his attempt to move away from

Queensland, Australia. E-mail: j.venugopal@qut.edu.au

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 871

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

the dualist world view seems embryonic. His framework factors), exo (community level influence), macro (cultural

appears to lack a holistic outlook and presents fragmented contexts) and chrono (context of time) systems

relationships between the human population and the (Bronfenbrenner, 1994, p. 39). Rapoport (Rapoport, 2005, p.

environment. 23) uses this framework to conceptualise housing as an

expanding system of settings. It is to be noted that this

framework projects a non-dualist (advaitha) world view. It is

the ubiquitous nature of this idea that has made it possible to

comprehend such a complex phenomenon in a simple manner,

a quality that is lacking in Lawrence‟s framework for human

ecology.

Rapoport„s field of investigation is Environment-

Behaviour Studies (EBS) which deals with the subject matter

of Environment-Behaviour Relation (EBR). Within the

framework of EBS, he attempts to explore the nature and types

of environment, dismantle the term „culture‟ and discover the

mechanisms that link people and environment, particularly in

the context of housing. Rapoport does not use the term human

ecology in his writings. But his area of research not only

seems to encompass all the factors of human ecology, but also

relates it to an explanatory theory of architecture with a focus

on housing.

Having discussed some relevant theories in human

ecology, it is now necessary to explain what this article means

by „Living environment‟. For the purpose of this paper, „living

environment‟ is the environment created by human beings as a

setting for their daily living. This definition points towards the

concept of dwelling which is very close to the system of

settings as shown by Rapoport (2000, p. 147) (see figure 2).

Rapoport (2005, p. 24) conceptualizes environment in four

Figure 1: Framework of Human Ecology Perspective ways starting with the most abstract to the most concrete.

(Lawrence, 2001, p. 691)

The organization of space, time, meaning and

communication.

A system of settings,

The cultural landscape

Consisting of fixed, semi-fixed, and non-fixed

elements.

Rapoport argues that these formulations can be unified

despite of their different levels of abstraction and complexity.

However, he expands his study based on the conceptualization

of environments as a system of settings. While this approach is

pragmatic, a detailed examination of each of these

conceptualizations reveals that the first one is more holistic

and relates human existence to the most abstract concepts of

the living environment such as space and time. The concepts

of meaning and communication emerge as a result of human

interaction with the environment. These concepts, if applied to

different scales of environment such as micro, meso and

macro will produce myriad forms of relations which will

represent the complex nature of human ecology. Therefore,

Figure 2: Relationship between Housing-Neighbourhood and defining living environment as an expanding organization of

Settlement Defined as System of Settings based on space, time, meaning and communication seems appropriate

Bronfenbrenner‟s Theory of Human Ecology (Rapoport, 2000, for the purpose of this paper. The task now is to formulate

p. 147) these concepts into a tangible framework for designing living

The anthropologic framework for human ecology by environments. The following section attempts to interpret

Bronfenbrenner (1979) seems to present a simple but Vastu Purusha Mandala as a solution towards the above said

embracive way of representing human ecology. He developed task.

a theoretical framework that included micro (individual or

interpersonal features), meso (organizational or institutional

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 872

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

III. VASTU PURUSHA MANDALA (VPM) „paramasayika‟ mandala. It is to be noted that this is one of the

Before venturing into explaining VPM, it is necessary to several types of mandalas that are prescribed by the ancient

create an understanding of „Vastu Shasthra‟, the branch of texts (Chakrabarti, 1998, pp. 70-74).

architectural science to which VPM belongs to. „Vastu‟ is

derived from the root Sanskrit sound „Vas‟ which

encompasses a range of words related to objects that are used

as a surround by human beings like cloths, house and

habitation (Monier-Williams, 2005). „Vastu‟ in the context of

Vastu Shastra means places where immortals and mortals

dwell (Kumar, 2005, p. 3). Vastu is classified in to earth

(bhumi), house (harmya), vehicle (yana) and furniture/seating

(sayana). The general meaning of „Shastra‟ is science, which

makes the translation of Vastu Shastra , the science of places

where immortals and mortals live. Vastu Shastra comprises of

a body of knowledge that was fully developed before the

advent of 1st century AD but most of the literary material

between 6th century BC and 6th century AD are lost

(Chakrabarti, 1998, p. 1). Vastu Shastra was developed and

modified by a successive generation of architectural scholars

through a range of Sanskrit and Tamil literary works till 15th Figure 3: Vastu Purusha on Paramasayika Mandala (Achuthan

century. Most of the translated and interpreted books on Vastu & Prabhu, 2003; Kramrisch, 1976, p. 88) see (Chakrabarti,

Shastra are based on six ancient Sanskrit books – Mayamata, 1998, pp. 70-74) for Other Versions of vastu Purusha Mandala

Manasara, Samaranganasuthradhara, Rajavallabha, (Author)

Vishwakarmaprakasha and Aparajitapraccha (Chakrabarti,

1998, p. 2). Scholarly works such as Kramrisch (1976), Moore (1989),

(Marriot, 1976) and Shukla (1996) and on the divisions,

Further scholarly development of Vastu Shasta along with symbolisms and meanings of VPM are reviewed here. The

other indigenous traditions slowed down after 10th century following section will discuss the two themes that emerged as

AD because of the increase in foreign invasion to India. a result of this review.

During the British rule in India from 1858 to 1947, indigenous

educational system was revolutionized based on modern IV. ENVIRONMENTAL FOCUS

scientific philosophy. The indigenous system of knowledge

was regarded inferior to the new scientific outlook that was “Whereas the earth, as the surface of this world which

brought in. But, in the past decade, importance of Vastu supports the movements and the weight of our bodies, is

Shasta has increased among general public in India which has round, the earth held in the embrace of the sky and subject to

led to a system where an architect works with a Vastu its laws is represented as fixed four-fold. The prithvimandala

specialist especially for residential buildings. This therefore, is a square mandala or chakra.”(Kramrisch, 1976, p.

development has led to some academic interest in the revival 29)

of Vastu Shastra in the recent years (Awasthi, Singh, There are no contemporary authors who have written about

Bhargava, & Singh, 2004; Dili, Naseer, & Zacharia, 2011; VPM without referring to the monumental work of Kramrisch

Patra, 2006, 2009). But Vastu Shastra is still not considered as (1976). This is the first work of its kind which lifted the image

a subject of study in the mainstream educational system for of Indian architecture beyond archaeological importance in the

architects. This is primarily because of the mysticism and western world. The difference of her study approach is that,

symbolism that are associated with this product of eastern she has also employed non-western methods that extend into

philosophy. The existing form of Vastu Shastra needs a understanding the metaphysics and symbolisms associated

revival to completely address current issues in built with Hindu architecture. The above said quote throws light on

environment development. the square form of the mandala. In the mandala, the earth is

Vastu Shastra is a product of Vedic science which perceived as a square. As Kramrisch (Kramrisch, 1976, p. 29)

considers humans as part of a whole. It addresses a wide range aptly says, the square implies the 4 directions that are

of applications like town planning, temple architecture, identified by the movement of the sun, the direction of earth‟s

residential architecture, painting and sculpturing. It is magnetic field and other universal laws. However, she

important to state that Vastu Shastra for every site, state and recognises that the ancient texts also prescribe other shapes

country differs as per the various regional factors of that place. such as circle and octagon but proposes square as the perfect

The most important symbolic diagram that is used in Vastu shape. She goes further into deeper meanings of the 32 deities

Shastra for planning and locating a house is called vastu assigned to the border of the mandala, highlighting the 8

purusha mandala. Here, the site is represented as a human important directions which include 4 cardinal points and the 4

being or „vastu purusha‟ with his face down and his body corners of the square. The 8 directions, Kramrisch (1976, p.

occupied by various deities with different qualities. Figure 3 29) says are born from the contact of heaven and earth and

illustrates the most commonly used configuration called the realised by the apparent movement of sun, moon and other

constellations. Therefore she concludes that, the (terrestrial

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 873

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

power) impact of the „directions‟ on land (space) is sociological model for VPM that identifies the eastern side

determined by the movement (celestial power) of sun and with activities that are „mixing‟ in nature. This is the open and

other planets around earth (time). interactive area of a house where external mingling happens.

This is opposite to western side where there are activities that

Shukla (1996, pp. 195-200) examines the work of

are „unmixing‟, such as privacy and seclusion. She assigns

Mankad(1950) on the symbolism of the deities on VPM and

another set of attributes to the north and south direction and

brings out the focus on the yearly and daily influence of sun

calls them „matching‟ and „unmatching‟. She also plots a third

on earth. He associates the 9 deities on eastern side to the

morning spectrum of sun which includes ultraviolet and dimension that is shown vertically called marking and

infrared rays at the corners and seven colours of VIBGYOR in unmarking.

the middle. He then moves towards the centre and assigns the Moore (1989) discusses VPM based on Hindu sociological

5 deities on the east of Brahman to the attributes of sun on his models developed by Karmarich(1976) and Marrriot(1976) in

journey to the west. Sun at mid-day is represented by the her findings from an ethnographic study of the pre-industrial

centre deity, Brahman. Likewise he interprets the 5 deities on houses of Kerala that where built as per Vastu Shastra. She

the west of Brahman as the afternoon attributes of sun and finds Marriot‟s model, more connected to her observations.

finishes up with the 9 deities on the west as attributes of sun at Moore‟s analysis brings out the importance of the center

dusk and night. courtyard of a house as the balancing space which ties all the

different activities of a house.

The orientation of the vastu purusha is shown with his

head in the east and legs in the west in former versions of the

mandala (Kramrisch, 1976, p. 57). Figure 3 shows the later VI. VPM AS A HUMAN ECOLOGIC FRAMEWORK

version where he lies diagonally from northeast to south-west. From the discussion above, it is clear that VPM is a

Although this position is said to be permanent, the vastu diagram that establishes a relationship between human and

purusha rotates throughout the year (Kramrisch, 1976, p. 62). environment. The definition of human ecology is recalled here

The rotation of vastu purusha corresponds to different lunar as the organization of space, time, meaning and

months and depicts different seasons (Kumar, 2005, p. 8). communication. The following section will try to identify

aspects of space, time, meaning and communication in VPM.

Another important aspect of VPM is its fractal nature. This

is embedded in the measurement system used in Vastu

Shastra. Rian, et al (2007, p. 4097) recently investigated the

application of fractal geometry in Kandariya Mahadev temple,

Khajuraho with the help of VPM. They illustrate the

complexity of VPM and relate it to the developmental plans of

Hindu temples. Their investigation brought out the fact that

modern architecture lacked the fractal interlinks and that there

is an emerging trend to incorporate fractal geometry into

architectural forms.

V. SOCIAL FOCUS

The superimposed vastu purusha is the most important

symbol of the mandala. Kramrisch (1976, p. 52) points out

that the human symbol literally is connected to the owner of

the land. Her words are: “ Builder and building are one; the

building is a test for his health and probity of the builder, his

„alter ego‟, his second body …” This implies that care should

be taken when disturbing the organism of the land as though

the disturbance is to be made to one‟s own body. The mandala

also exhibits a concentric nature of increasing importance Figure 4: Vastu Purusha Mandala as Representation of Space

towards the centre. The Brahman at the center is the most (Author)

sacred part of the mandala which can be related to the soul of

the building. As the concentric square expands outwards, the

Brahman is connected to external qualities of the environment.

The social focus is derived from the meanings assigned to

each sector of the mandala. This means that the social

structure of a building is brought in as another set of attributes

assigned to the same deities. For example, active and open

activities are linked to east where the energy of sun is

abundant. Calm and inactive aspects like resting, storage etc

are linked to west where, sun‟s harmful energy is controlled

by heavy and tall built structure. Marriot (1976) proposes a

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 874

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

source in the north east, bedrooms in the south and west and

so on (Achuthan & Prabhu, 1997).

Figure 6 (IN Annexure-1) illustrates the expansion of

meaning and communication from the symbolism of VPM.

This diagram is not claimed to be a complete one. However, it

is proposed as a starting point for collating valid information

to develop an explanatory theory for VPM. The arguments so

far presented in this article have oriented this theory towards

human ecology.

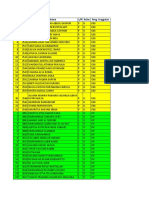

VII. VPM AND HIGH-DENSITY LIVABILITY

Human ecology is much more complex in the current state

of our planet than at the time of the development of VPM.

Various concepts have emerged from the study of the

relationship of human and environment. Livability is one such

concept. It is particularly important for the growing number of

high-density developments in compact cities. A recent effort

to understand the livability in high-density housing was

initiated in Australia by the Centre for subtropical design,

Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane. Later a set of

guidelines where developed to assist various stakeholders such

as residents, building managers, designers and developers to

achieve high livability standards in high-density living

environments. This research, included surveys, interviews,

observations and temperature monitoring and was undertaken

Figure 5: Vastu Purusha Mandala as Representation of Cyclic by Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and

Nature of Time (Author) Northshore Development Group as part of an Australian

VPM illustrates space and time as inseparable and Research Council funded project investigating the social,

coterminous entities. The spatial aspect of VPM is defined by environmental and economic impacts of high-density living.

the placement of sun, definition of directions and the Table 1 demonstrates 5 parallel guidelines between VPM and

institution of proportions (see figure 4). The oriented square the livability guidelines developed by the research mentioned

form, the geometric divisions and the establishment of the 8 above. This table is presented here to demonstrate the

directions in relation to the path of the sun represents the potential of VPM to act as a global framework for designing

aspect of space in VPM. living environments.

The path of sun, plotted as aspects of the divinities, VIII. CONCLUSION

represents diurnal time and also dismantles different effects of

sun as a spatial determinant. The rotation of the human form From the above discussion, it is clear that there is potential

with in the square denotes annual cyclic repeats of time and for further research into the various representations of VPM

signifies the qualities of each of the 8 directions with relation and its usefulness as a tool to represent the human ecology of

to time (see figure 5). The fractal geometry presented in VPM designing living environments. The idea of a symbolic deity

denotes the expanding and iterative nature of space and time. representing different but connected social and environmental

It is this unit of measurement that transforms space and time in attributes seems to be a comprehensive way to perceive human

to tangible forms (grids). ecology. The full potential of this diagram is yet to be

developed for the current state of living but there is no doubt

The tangible forms are then credited with meanings as in asserting the fact that vastu purusha mandala is a tool that

symbolic deities. For example the deity in the north-east was used by the ancient architects to perceive an object of

corner is „Isanan‟ who is the God of creation. Isanan is one of creation within the complex nature of the environment and

the Vedic Gods. Isanan is generally regarded with positive beyond.

qualities which imply meanings like open, light, receptive and

interactive etc to the spaces constructed in the north east

corner of a plot. Similarly, the south west is deity is „Nirurthi‟

who is the controller of destruction, decomposition and exit

from life. The meanings assigned to Nirurthi are heavy,

closed, clean, resting and seclusion etc. These meanings are

now morphed into living environments to produce human

interactions or communications. For example, entrance and

living room towards east and north, kitchen facing east, water

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 875

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

ANNEXURE-1

Figure 6: Vastu Purusha Mandala as a Human Ecologic Framework for Living Environment Representing Space, Time, Meaning

and Communication (Author). The Meaning and Communication Inputs are Derived from Various Literature including

(Kramrisch, 1976), (Shukla, 1996), (Marriot, 1976) and (Moore, 1989) (Author)

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 876

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

Table 1: Parallel Guidelines between Vastu Purusha Mandala and the Livability Guidelines developed by CSD, Brisbane, Qld,

Australia

[12] Lawrence, R. J. (2001). Human ecology. In M. K. Tolba (Ed.), Our

fragile world: challenges and opportunities for sustainable

REFERENCES development (pp. 675-693): Eolss publishers oxford.

[1] Achuthan, A., & Prabhu, B. T. S. (1997). Design in Vasthuvidya. [13] Lawrence, R. J. (2003). Human ecology and its applications.

Calicut, Kerala: Vasthuvidya prathisthanam, Saraswatham. Landscape and Urban Planning, 65(1-2), 31-40.

[2] Achuthan, A., & Prabhu, B. T. S. (2003). [14] Marriot, M. (1976). Hindu transactions: diversity without dualism. In

Manushyalachandrikasaram. Calicut, Kerala: Sarasat academy of B. Kapferer (Ed.), Transaction and meaning: directions in the

higher education,. anthropology of exchange and symbolic behavior Institute for the

[3] Awasthi, V., Singh, N., Bhargava, D., & Singh, M. (2004). Study of Human Issues.

Environmental considerations in vaastu culture for residential [15] Monier-Williams, M. (2005). A Sanskrit-English dictionary:

building orientation. Journal of architecture institution of engineers, etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to

85, 1-8. cognate Indo-European languages: Motilal Banarsidass.

[4] Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: [16] Moore, M. A. (1989). The Kerala house as a hindu cosmos.

experiments by nature and design: Harvard University Press. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 23(1), 169-202.

[5] Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human [17] Nauser, M., & Steiner, D. (2002). Human Ecology: Taylor and

development International encyclopedia of education (2 ed., Vol. 3): Francis.

Oxford, Elsevier. [18] Orr, D. (2002). The nature of design: ecology, culture, and human

[6] Bruhn, J. (1974). Human ecology: A unifying science? Human intention. New York: Oxford University Press (US).

Ecology, 2(2), 105-125. [19] Orr, D. (2007). Architecture, ecological design, and human ecology.

[7] Chakrabarti, V. (1998). Indian architectural theory: contemporary In K. Tanzer & R. Longoria (Eds.), The Green Braid: Towards an

uses of Vastu Vidya: Curzon. Architecture of Ecology, Economy and Equity, Hoboken: Taylor &

[8] Corporation of Cochin (Cartographer). (2010). Proposed land use Francis Ltd.

map. [20] Park, R. E., Burgess, E. W., & McKenzie, R. D. (1925). The city.

[9] Dili, A. S., Naseer, M. A., & Zacharia, V. T. (2011). Passive control Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

methods for a comfortable indoor environment: Comparative [21] Patra, R. (2006). A Comparative Study on Vaastu Shastra and

investigation of traditional and modern architecture of Kerala in Heidegger's „Building, Dwelling and Thinking‟1. Asian Philosophy,

summer. Energy and Buildings, 43(2-3), 653-664. 16(3), 199-218.

[10] Kramrisch, S. (1976). The Hindu temple. New Delhi: South Asia [22] Patra, R. (2009). Vaastu Shastra: Towards sustainable development.

Books. Sustainable Development, 17(4),

[11] Kumar, A. (2005). Vaastu: The Art And Science Of Living. New [23] 244-256.

Delhi: Sterling Publishers Private Limited.

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Proceedings of International Conference on Advances in Architecture and Civil Engineering (AARCV 2012), 21st – 23rd June 2012 877

Paper ID AR65VS, Vol.2

[24] Rapoport, A. (2000). Theory, Culture and Housing. Housing, Theory

and Society, 17(4), 145-165.

[25] Rapoport, A. (2005). Culture, architecture, and design: Locke

Science Pub. Co.

[26] Rian, I. M., Park, J.-H., Uk Ahn, H., & Chang, D. (2007). Fractal

geometry as the synthesis of Hindu cosmology in Kandariya

Mahadev temple, Khajuraho. Building and Environment, 42(12),

4093- 4107.

[27] Shukla, D. N. (1996). Vastu-Sastra: Hindu Science of Architecture

(Vol. 1). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Private,

Limited.

[28] Soleri, P. (1969). Arcology: the city in the image of man. Cambridge,

Mass: MIT Press.

[29] Tanzer, K., & Longoria, R. (2007). The Green Braid: Towards an

Architecture of Ecology, Economy and Equity. Hoboken: Taylor &

Francis Ltd.

[30] Van der Ryn, S., & Cowan, S. (1996). Ecological design.

Washington, D.C: Island Press.

[31] Williams, D. E. (2007). Sustainable Design: Ecology, Architecture,

and Planning: Wiley.

ISBN 978-93-82338-01-7 | © 2012 Bonfring

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Quantum Jumping 1Dokument126 SeitenQuantum Jumping 1tvmedicine100% (14)

- Noble Quran Details - 1 FinalDokument16 SeitenNoble Quran Details - 1 FinalAhmad KhurshidNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Stranger With Analysis and SummaryDokument16 SeitenThe Stranger With Analysis and SummaryAlex Labs100% (1)

- ApolloDokument13 SeitenApolloaratos222Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gaia TheoryDokument12 SeitenGaia TheoryAlchemis7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cassian Prayer - The Monastic Tradition of Meditation 2Dokument32 SeitenCassian Prayer - The Monastic Tradition of Meditation 2celimarcel100% (1)

- Life and Mission of Maulana Muhammad Ilyas RADokument201 SeitenLife and Mission of Maulana Muhammad Ilyas RAMohammed SeedatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Varshapala Vedic Annual TajikaDokument223 SeitenVarshapala Vedic Annual TajikaPablo M. Mauro100% (12)

- A Way of Seeing People and Place: Phenomenology in Environment-Behavior ResearchDokument25 SeitenA Way of Seeing People and Place: Phenomenology in Environment-Behavior ResearchMatt TenneyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Niche Construction Theory and Human ArchitectureDokument7 SeitenNiche Construction Theory and Human Architectureclou321dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antolog Palat Patonvol 1Dokument528 SeitenAntolog Palat Patonvol 1Javier Hernández GarcíaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecological SoundscapeDokument14 SeitenEcological SoundscapeManuel Brásio100% (2)

- Andscapes Concepts of Nature and Culture For Landscape Architecture in The AnthropoceneDokument15 SeitenAndscapes Concepts of Nature and Culture For Landscape Architecture in The AnthropoceneAlejandro SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- VPM Framework JayadeviDokument10 SeitenVPM Framework JayadeviGauravRaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vastu Purusha Mandala Academic PaperDokument10 SeitenVastu Purusha Mandala Academic Paper7harma V1swaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human EcologyDokument6 SeitenHuman EcologyLeon RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interactions of Landscapes and Cultures PDFDokument12 SeitenInteractions of Landscapes and Cultures PDFChechyVillamilNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dialectic of Organic/ Inorganic Relations: John Bellamy FosterDokument23 SeitenThe Dialectic of Organic/ Inorganic Relations: John Bellamy Fosterduttons930Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ott - Environmental EthicsDokument8 SeitenOtt - Environmental EthicsAnonymous eAKJKKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioscience Rozzi 1999Dokument11 SeitenBioscience Rozzi 1999Francisca MassardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mind Map Literary Theory The Basics: EcocriticismDokument3 SeitenMind Map Literary Theory The Basics: EcocriticismBaskhoro Edo PrastyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit I - Fundamental Concepts IDokument7 SeitenUnit I - Fundamental Concepts ISagar SunuwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is It Time To Bury The Ecosystem Concept? (With Full Military Honors, of Course!)Dokument10 SeitenIs It Time To Bury The Ecosystem Concept? (With Full Military Honors, of Course!)JulianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- POLITICAL SCIENCE MORNING - SEM 2 HONS - CC4 Dr. Saheli BoseDokument19 SeitenPOLITICAL SCIENCE MORNING - SEM 2 HONS - CC4 Dr. Saheli BoseAbcd XyzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Details of Module and Its StructureDokument13 SeitenDetails of Module and Its StructureKrish JaiswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heras-Escribano - The Evolutionary Role of AffordancesDokument27 SeitenHeras-Escribano - The Evolutionary Role of AffordancesSweetmotherofgodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acta Astronautica: Albert A. HarrisonDokument7 SeitenActa Astronautica: Albert A. HarrisonKenneth Ayala CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017-MALHI-The-concept of The AnthropDokument28 Seiten2017-MALHI-The-concept of The AnthropStephany Rodrigues CarraraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phenomenology, Place, Environment, and Architecture: A Review of The LiteratureDokument29 SeitenPhenomenology, Place, Environment, and Architecture: A Review of The LiteratureAtomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical BackgroundDokument3 SeitenTheoretical BackgroundRhona CantagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Handbook of Evolutionary PsychologyDokument13 SeitenThe Handbook of Evolutionary PsychologyElifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andscapes Concepts of Nature and Culture For Landscape Architecture in The AnthropoceneDokument15 SeitenAndscapes Concepts of Nature and Culture For Landscape Architecture in The AnthropoceneDanny RodríguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 240 - Reading - Deep Ecology PDFDokument6 Seiten240 - Reading - Deep Ecology PDFPaola SotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunDokument12 SeitenGregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunsankofakanianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 3 Environmental Movements in IndiaDokument19 SeitenUnit 3 Environmental Movements in Indiakajal sainiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shifting From Human Centric To Eco Centric Platform-Deep EcologyDokument6 SeitenShifting From Human Centric To Eco Centric Platform-Deep EcologyHans HeinrichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art, Design and Metamorphosis in Outer Space (Irene Lia Schlacht)Dokument9 SeitenArt, Design and Metamorphosis in Outer Space (Irene Lia Schlacht)Luh Putu RuliatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whitaker, Andrew The Landscape Imagination WebVersion-1366225741Dokument22 SeitenWhitaker, Andrew The Landscape Imagination WebVersion-1366225741Gustavo GodoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAPOPORT, tHEORY CULTURE AND HOUSİNGDokument22 SeitenRAPOPORT, tHEORY CULTURE AND HOUSİNGLivia TanasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Naveh, Z. and Lieberman, A.S. 1984. Landscape Ecology - TheoryDokument12 SeitenNaveh, Z. and Lieberman, A.S. 1984. Landscape Ecology - TheoryDanielly Cozer AliprandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Landscape Approach For SustainabilityDokument19 SeitenA Landscape Approach For SustainabilityJosé David QuevedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Trouble With 'Evolutionary Biology'Dokument6 SeitenThe Trouble With 'Evolutionary Biology'ADNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soundscape Ecology The Science of Sound PDFDokument14 SeitenSoundscape Ecology The Science of Sound PDFGeorge AndreiNoch keine Bewertungen

- M1 - Nature and Ecology - Part 1 (v.2020-21) (Handouts)Dokument3 SeitenM1 - Nature and Ecology - Part 1 (v.2020-21) (Handouts)LANZ ADREAN YAPNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Landscape Symphonies" - Gardening As A Source of Landscape Architectural Practice, Engaged With ChangeDokument7 Seiten"Landscape Symphonies" - Gardening As A Source of Landscape Architectural Practice, Engaged With ChangeWoojin HwangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conceptualizingcontext 1998Dokument11 SeitenConceptualizingcontext 1998Tesis LabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feld 2015Dokument5 SeitenFeld 2015ASDFNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grey Room, Inc. and The Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyDokument27 SeitenGrey Room, Inc. and The Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyjohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 1Dokument11 SeitenUnit 1Madhu SubbuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissolving Dualities: Onto-Epistemological Implications of Ecological Sound ArtDokument15 SeitenDissolving Dualities: Onto-Epistemological Implications of Ecological Sound ArtRicardo AriasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainability 09 02123 v2Dokument23 SeitenSustainability 09 02123 v2myka joy oñezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Geographical Landscape Studies For Sustainable Territorial PlanningDokument23 SeitenThe Role of Geographical Landscape Studies For Sustainable Territorial PlanningVasilie MartologNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 PrefaceDokument3 Seiten5 PrefaceSRIKANTA MONDALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecology-Introduction (Reading Material) PDFDokument14 SeitenEcology-Introduction (Reading Material) PDFNovita RullyFransiska MarpaungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Being Ecology in Richard Powers' Generosity: Chen YiDokument9 SeitenHuman Being Ecology in Richard Powers' Generosity: Chen YiSomya SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study of Sibu Oromo Environmental EthicDokument7 SeitenA Study of Sibu Oromo Environmental EthicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does Ecology Need MarxDokument13 SeitenDoes Ecology Need MarxGustavo MeyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecocriticism A Study of Environmental IsDokument3 SeitenEcocriticism A Study of Environmental IsBlack LotusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environment Perceptions and Conservation PreferencesDokument10 SeitenEnvironment Perceptions and Conservation PreferencesVictoria PérezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecological Aesthetics 2010 PDFDokument7 SeitenEcological Aesthetics 2010 PDFcaphilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 005 - Order and Disorder in The Environment: Environmental EthicsDokument11 SeitenModule 005 - Order and Disorder in The Environment: Environmental EthicsKenberly DingleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week006 Module OrderandDisorderintheEnvironmentDokument11 SeitenWeek006 Module OrderandDisorderintheEnvironmentRheizha vyll RaquipoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maran 2007Dokument27 SeitenMaran 2007Anchen Catherine WheelNoch keine Bewertungen

- JASO Book Review - How Forests Think Eduardo Kohn - Lewis Daly-LibreDokument4 SeitenJASO Book Review - How Forests Think Eduardo Kohn - Lewis Daly-LibrePatrick ArleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Barrett Et Al. 2009) Positioning Aesthetic Landscape As EconomyDokument9 Seiten(Barrett Et Al. 2009) Positioning Aesthetic Landscape As EconomyOscar Leonardo Aaron Arizpe VicencioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ambientalismo, Ética Ambiental y Algunos Vínculos Con El PaisajeDokument12 SeitenAmbientalismo, Ética Ambiental y Algunos Vínculos Con El PaisajeJss MndzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Materialismo Ecocritica. Serenella Oppermann PDFDokument17 SeitenMaterialismo Ecocritica. Serenella Oppermann PDFVictoria AlcalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rabindranath Tagore A Philosophical Study on EnvironmentVon EverandRabindranath Tagore A Philosophical Study on EnvironmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tes Praktek Ibadah RegulerDokument49 SeitenTes Praktek Ibadah RegulerTU MTsN Tambakberas JombangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brett Salakas Self Review-FinalDokument6 SeitenBrett Salakas Self Review-Finalapi-275860636Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mantra PurascharanDokument9 SeitenMantra Purascharanjatin.yadav1307100% (1)

- History Nicula Monastery Wonderworking Icon of The Mother of GodDokument2 SeitenHistory Nicula Monastery Wonderworking Icon of The Mother of Godlilianciachir7496Noch keine Bewertungen

- PCMC HistoryDokument2 SeitenPCMC HistoryMadhushree RathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- EDM 1 Carolnian Missionary Final Req 1Dokument1 SeiteEDM 1 Carolnian Missionary Final Req 1joan arreolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Day 1 9 Novena To MHC 2023Dokument226 SeitenComplete Day 1 9 Novena To MHC 2023Jasper A. SANTIAGONoch keine Bewertungen

- MabdaDokument106 SeitenMabdaAlvi100% (1)

- PDF 2 ImageDokument14 SeitenPDF 2 ImageTim van IerschotNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Private Schools SY 2022 2023 For DOC ODokument33 SeitenList of Private Schools SY 2022 2023 For DOC Olouis adonis silvestreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Position of The SoulDokument7 SeitenConstitutional Position of The SoulchanduvenuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nilai Akhlak Islam Dalam Cerpen GergasiDokument9 SeitenNilai Akhlak Islam Dalam Cerpen GergasiErina Tri YuliantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kartarpur Corridor: SignificanceDokument2 SeitenKartarpur Corridor: Significancemars earthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ogham Gematria - Drawing Sephiroth6Dokument4 SeitenOgham Gematria - Drawing Sephiroth6Simon StacheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chen Chang Xing S Teaching of The Correct Boxing SystemDokument5 SeitenChen Chang Xing S Teaching of The Correct Boxing SystemTibzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient China: GeographyDokument18 SeitenAncient China: GeographyInes DiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and ArchitectureDokument3 SeitenArt and Architectureapi-291662375Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Death of Socrates Jacques Louis DavidDokument13 SeitenThe Death of Socrates Jacques Louis Davidzappata73Noch keine Bewertungen

- Islam Dan Modernisme Di Indonesia: Kontribusi Pemikiran Mohamad Rasjidi (1915-2001) Mohammad Zakki AzaniDokument36 SeitenIslam Dan Modernisme Di Indonesia: Kontribusi Pemikiran Mohamad Rasjidi (1915-2001) Mohammad Zakki Azanicep dudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Onmyoji Soul DatabaseDokument16 SeitenOnmyoji Soul DatabaseDcimasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Censorship in Saudi ArabiaDokument97 SeitenCensorship in Saudi ArabiainciloshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viva! Cristo Rey!: Solemnity of Christ The KingDokument132 SeitenViva! Cristo Rey!: Solemnity of Christ The KingKristel Arceo SungaNoch keine Bewertungen