Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

PPDS McDonald - Et - al-2015-BJOG: - An - International - Journal - of - Obstetrics - & - Gynaecology PDF

Hochgeladen von

Rommy Yorinda PutraOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PPDS McDonald - Et - al-2015-BJOG: - An - International - Journal - of - Obstetrics - & - Gynaecology PDF

Hochgeladen von

Rommy Yorinda PutraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.

13263 General gynaecology

www.bjog.org

Dyspareunia and childbirth: a prospective cohort

study

EA McDonald,a D Gartland,a R Small,b SJ Browna,c

a

Healthy Mothers Healthy Families Research Group, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, Vic., Australia b The Judith Lumley

Centre, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia c General Practice and Primary Health Care Academic Centre, The University of

Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia

Correspondence: EA McDonald, Healthy Mothers Healthy Families Research Group, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, The Royal

Children’s Hospital, Flemington Road, Parkville, Vic. 3052, Australia. Email ellie.mcdonald@mcri.edu.au

Accepted 15 November 2014. Published Online 21 January 2015.

Objective To investigate the relationship between mode of perineum or unsutured tear, women who had an emergency

delivery, perineal trauma and dyspareunia. caesarean section (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.41, 95% confidence

interval [95% CI] 1.4–4.0; P = 0.001), vacuum extraction (aOR

Design Prospective cohort study.

2.28, 95% CI 1.3–4.1; P = 0.005) or elective caesarean section

Setting Six maternity hospitals in Melbourne, Australia. (aOR 1.71, 95% CI 0.9–3.2; P = 0.087) had increased odds of

reporting dyspareunia at 18 months postpartum, adjusting for

Sample A total of 1507 nulliparous women recruited in the first

maternal age and other potential confounders.

and second trimesters of pregnancy.

Conclusions Obstetric intervention is associated with persisting

Method Data from baseline and postnatal questionnaires (3, 6, 12

dyspareunia. Greater recognition and increased understanding of

and 18 months) were analysed using univariable and multivariable

the roles of mode of delivery and perineal trauma in contributing

logistic regression.

to postpartum maternal morbidities, and ways to prevent

Main outcome measure Study-designed self-report measure of postpartum dyspareunia where possible, are warranted.

dyspareunia at 18 months postpartum.

Keywords Cohort studies, delivery obstetric, dyspareunia, pain,

Results In all, 1244/1507 (83%) women completed the baseline perineum, postpartum period, prospective studies, sexual intercourse.

and all four postpartum questionnaires; 1211/1237 (98%) had

Linked article This article is commented on by C Sakala, p. 680 in

resumed vaginal intercourse by 18 months postpartum, with 289/

this issue. To view this mini commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/

1211 (24%) women reporting dyspareunia. Compared with

10.1111/1471-0528.13264.

women who had a spontaneous vaginal delivery with an intact

Please cite this paper as: McDonald EA, Gartland D, Small R, Brown SJ. Dyspareunia and childbirth: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2015;122:672–679.

nulliparous pregnancy cohort study.8 The primary objective

Introduction

of this paper was to investigate the contribution of obstet-

The relationship between obstetric risk factors including ric risk factors, including mode of delivery and perineal

mode of delivery and perineal trauma and dyspareunia is trauma, to postpartum dyspareunia. In addition, we aimed

not well characterised or understood.1–7 Previous studies to assess the influence of potential confounders, including

have suffered from several methodological limitations breastfeeding, maternal fatigue, maternal depression and

including cross-sectional study design,1–3,5,6 limited power intimate partner abuse.

to assess associations with obstetric risk factors1–7 and lack

of long-term follow up.1–7 Inferences drawn from the exist-

Methods

ing literature are limited by the failure of the studies to

consider prepregnancy dyspareunia2–7 and a range of post- Sample and participants

partum factors, such as breastfeeding and intimate partner Details regarding study eligibility and exclusion criteria and

abuse, that may confound associations.2–6 recruitment methods are available in a published study pro-

This study draws on data collected in the Maternal tocol.8 Briefly, women were recruited to the study between

Health Study, an Australian multicentre, prospective April 2003 and December 2005 from six metropolitan public

672 ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Dyspareunia and childbirth

maternity hospitals in Melbourne, Australia. We recruited proportions of women reporting symptoms divided by the

nulliparous women, aged over 18 years, in the first and total number of women who had resumed vaginal sex and

second trimesters of pregnancy. Women with poor Eng- had data available for the relevant period. Pain on first vag-

lish language literacy were excluded. inal sex is reported separately.

Risk factors for postpartum dyspareunia were investi-

Measures and definitions gated using univariable and multivariable logistic regres-

At recruitment, participants were asked to complete a sion. Logistic regression modelling was used to examine the

baseline questionnaire recording demographic and social association between mode of delivery and perineal trauma

characteristics, including age, country of birth and socio- (exposures of main interest) and dyspareunia at 18 months

economic status, and baseline measures of common maternal postpartum (primary outcome), taking into account poten-

morbidities, including dyspareunia before and during preg- tial confounders. Maternal age was included in modelling

nancy.1 Follow-up questionnaires were administered at 3, 6, analyses for a priori reasons. Other variables were included

12 and 18 months postpartum. Data regarding the mode of based on associations that were observed in univariable

delivery and degree of perineal trauma were collected in the analyses at 6 and/or 18 months postpartum. Data are pre-

3-month postpartum questionnaire and abstracted from sented as crude or adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95%

medical records for a subset of women. There was a high confidence intervals (95% CI).

degree of congruity between women’s own accounts of mode Ethical approval for the study was provided by La Trobe

of delivery and other obstetric events and data abstracted University (2002/38); Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne

from medical records.9,10 (27056A); Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne (2002/23);

Follow-up questionnaires included study-designed ques- Southern Health, Melbourne (2002-099B); and Angliss

tions regarding sexual health and dyspareunia drawing on Hospital, Melbourne (2002).

questions included in the Australian Longitudinal Women’s

Health Study11 and a study by Barrett et al.1 assessing

Results

women’s health after childbirth. Study questionnaires also

included validated measures of maternal depressive symp- Participants

toms (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale)12 and inti- A total of 1507 women enrolled in the study. The mean

mate partner abuse (Composite Abuse Scale),13,14 and gestation of study participants at the time of enrolment

single item measures assessing maternal fatigue15 and infant was 15.0 weeks (range 6–24 weeks). We were unable to

feeding.16 Pretesting of the questionnaires, paying particu- determine a precise response fraction, but conservatively

lar attention to study-designed questions, was undertaken estimate that the response was between 1507/5400 (28%)

with a pilot sample of women recruited through participat- and 1507/4800 (31%). The follow-up response fractions

ing hospitals. The baseline Maternal Health Study ques- were 1431/1507 (95%), 1400/1507 (93%), 1387/1507

tionnaire is available on the study website.17 Postnatal (92%), 1326/1507 (88%) at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months post-

questionnaires can be made available by contacting the partum, respectively. In all, 1211/1239 (98%) participants

authors. were sexually active at 18 months postpartum.

Study participants were representative in relation to

Statistical analysis obstetric characteristics including mode of delivery and

Data were analysed using STATA version 13 (StataCorp., perineal trauma (see Table 1). Women born overseas in

College Station, TX, USA).18 Sample representativeness was countries where English is not the first language, and youn-

assessed by comparing data on social and obstetric charac- ger women were under-represented. Further information

teristics of participants with routinely collected perinatal regarding sociodemographic and reproductive characteris-

data for nulliparous women giving birth in the study per- tics of the sample and representativeness of study partici-

iod at the six participating hospitals, and at all public pants is available in previous papers.10,19 The 1244/1507

maternity hospitals in Victoria. (83%) women who completed all four follow-up question-

Analyses presented in the paper are restricted to women naires comprise the sample for the analyses in this paper

who completed the baseline questionnaire and all follow-up (Figure 1).

questionnaires. The proportions of women resuming vagi-

nal sex by 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum were calculated Birth outcomes

based on the proportion of women reporting resumption A total of 609/1244 (49.0%) women had a spontaneous

of sex divided by the total number of women with valid vaginal birth, two-thirds of whom (411/609, 67.5%) sus-

responses at each time point. tained a sutured tear and/or episiotomy; 134/1244 (10.8%)

The period prevalence of dyspareunia at 6 and had an operative vaginal birth assisted by vacuum extrac-

18 months postpartum was calculated based on the tion and 133/1244 (10.7%) gave birth assisted by forceps.

ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 673

McDonald et al.

Table 1. Social characteristics of participants in the Maternal Health Study compared with Victorian Perinatal Data Collection Unit data

Maternal Health Nulliparous women Nulliparous women

Study participants ≥18 years giving ≥18 years giving

(n = 1507) birth in Victorian birth in the six

public hospitals participating

1/7/03 to 31/12/05 Victorian hospitals

(n = 40 905) 1/7/03 to 31/12/05

(n = 13 803)

n % n % n %

Maternal age at birth of first child

18–24 years 212 14.1 12 216 29.8 3813 27.6

25–29 years 437 29.0 13 802 33.7 4645 33.7

30–34 years 580 38.4 10 740 26.3 3769 27.3

35–39 years 236 15.7 3552 8.7 1319 9.6

≥40 years 42 2.8 595 1.5 257 1.9

Relationship status*

Married 914 60.7 22 790 56.0 8300 60.3

Unmarried 593 39.3 17 932 44.0 5469 39.7

Country of birth*

Australia 1115 74.4 29 791 73.3 8603 62.5

Overseas—English speaking 141 9.4 2109 5.2 905 6.6

Overseas—non-English speaking background 243 16.2 8738 21.5 4267 30.9

Mode of delivery*

Caesarean—no labour 140 9.8 3750 9.2 1237 9.0

Caesarean—laboured 292 20.4 7665 18.7 2587 18.7

Spontaneous vaginal birth 695 48.6 20 785 50.8 7000 50.7

Vaginal breech birth 5 0.3 182 0.4 95 0.7

Vaginal with forceps 150 10.5 3915 9.6 1426 10.3

Vaginal with vacuum extraction 149 10.4 4603 11.3 1457 10.6

Perineal trauma**

Intact perineum 595 41.7 19 805 48.4 6296 45.6

Unsutured laceration 72 5.0 n/a n/a n/a n/a

Sutured laceration 439 30.8 11 074 27.1 4221 30.6

Episiotomy 228 16.0 9068 22.2 3089 22.4

Episiotomy and tear 93 6.5 958 2.3 197 1.4

*Denominators vary due to missing values.

**Data collected by the Perinatal Data Collection Unit on perineal trauma does not include information regarding unsutured lacerations or

nonperineal lacerations, e.g. vaginal wall tears.

The majority of these women sustained a sutured tear and/ (44.7%) women at 3 months postpartum, 496/1144

or episiotomy (124/134, 92.5% and 129/133, 97.0%, respec- (43.4%) women at 6 months postpartum, 333/1184

tively). In all, 120/1244 (9.7%) were delivered by elective (28.1%) women at 12 months postpartum and 289/1236

caesarean section and 248/1244 (19.9%) were delivered by (23.4%) women at 18 months postpartum. Of the 496

emergency caesarean section. women who reported dyspareunia at 6 months postpartum,

one-third (162/496, 32.7%) reported persisting dyspareunia

Dyspareunia following childbirth at 18 months postpartum. In all, 338/1234 (27.4%) women

By 3 months postpartum, 970/1239 (78.3%) had resumed reported dyspareunia in the year prior to the index preg-

vaginal intercourse; 1165/1239 (94.0%) by 6 months post- nancy.

partum, 1202/1239 (97.0%) by 12 months postpartum and

1211/1239 (97.7%) by 18 months postpartum. Most of the Associations with dyspareunia

women who had resumed sex by 12 months postpartum The unadjusted odds of dyspareunia at 18 months postpar-

experienced pain during first vaginal sex after childbirth tum were higher in women who gave birth by vacuum

(961/1122, 85.7%). Dyspareunia was reported by 431/964 extraction (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.2–3.5; P = 0.013),

674 ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Dyspareunia and childbirth

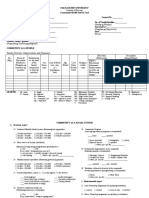

Q1: 1507 eligible participants

13 Withdrew

Q2: 1494 participants

1431 completed (95.0% of 1507 participants)

5 Withdrew

3 lost to follow up

Q3: 1486 participants

1400 completed (92.9% of 1507 participants)

16 Withdrew

6 lost to follow up

Q4: 1464 participants

1357 completed (90.0% of 1507 participants)

6 Withdrew

6 lost to follow up

Q5: 1452 participants

1327 completed (88.1% of 1507 participants)

Figure 1. Maternal Health Study participation flowchart to 18 months postpartum.

emergency caesarean section (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.3–3.3; other variables in the model. Elective caesarean section was

P = 0.004) or elective caesarean section (OR 1.65, 95% CI also associated with increased odds of dyspareunia at

0.9–2.9; P = 0.090) compared with women who had a 18 months postpartum, although the confidence interval

spontaneous vaginal birth with an intact perineum. Youn- suggests borderline statistical significance.

ger women (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.0–2.5; P = 0.057), women Similar patterns of association were found between

who experienced dyspareunia before the index pregnancy dyspareunia at 6 months postpartum, mode of delivery,

(OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.6–2.9; P = 0.000), women who perineal trauma and other maternal and postnatal factors

reported intimate partner abuse from birth to 12 months (Table 3). Women who had an operative vaginal delivery

postpartum (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.3–2.6; P = 0.001), women (with forceps or vacuum extraction) had greater than a

who reported fatigue at 18 months postpartum (OR 1.65, three-fold increase in adjusted odds of dyspareunia at

95% CI 1.2–2.3; P = 0.002) and women who reported 6 months postpartum. Emergency caesarean section and

depressive symptoms at 18 months postpartum (OR 1.97, vaginal birth with a sutured tear and/or episiotomy were

95% CI 1.3–3.0; P = 0.002) also had increased odds of associated with a two-fold increase in odds of dyspareunia

reporting dyspareunia at 18 months postpartum. after taking into account other factors in the model.

To obtain more precise estimates of the association Women who had an elective caesarean section did not

between mode of delivery and dyspareunia at 18 months have raised odds of reporting dyspareunia at 6 months

postpartum, we developed a multivariable logistic regres- postpartum. Prepregnancy dyspareunia was associated with

sion model (Table 2). A composite variable combining data a two-fold increase in odds of dyspareunia at both 6 and

on mode of delivery and perineal trauma was the exposure 18 months postpartum. Observed associations with obstet-

of main interest. Maternal age was included in the model ric intervention in multivariable models were stronger

for a priori reasons based on previous research showing than associations with postnatal factors, including mater-

that younger women are more likely to experience dyspa- nal depressive symptoms, fatigue and intimate partner

reunia.20,21 Dyspareunia before pregnancy, maternal depres- abuse.

sion, maternal fatigue and intimate partner abuse were

included because of the significant associations with dyspa-

Discussion

reunia at 6 and/or 18 months postpartum noted in univari-

able analyses. Main findings

Women who gave birth by emergency caesarean section Almost all women experience some pain during sexual

or vacuum extraction and those who reported prepregnan- intercourse following childbirth. Our findings show that

cy dyspareunia had greater than a twofold increase in the extent to which women report dyspareunia at 6 and

adjusted odds of persisting dyspareunia at 18 months post- 18 months postpartum is influenced by events during

partum compared with women who had a spontaneous labour and birth. The odds of dyspareunia at 18 months

vaginal birth with an intact perineum after adjusting for were substantially higher in women who delivered by

ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 675

McDonald et al.

Table 2. Adjusted odds of dyspareunia at 18 months postpartum associated with mode of delivery, perineal trauma and other risk factors*

Dyspareunia at 18 months Adjusted OR (95% CI) P values

postpartum

No Yes

n (%) n (%)

Mode of delivery and perineal trauma

Spontaneous vaginal birth

Intact perineum/unsutured tear 153 (83.2) 31 (16.8) 1.0 ref

Sutured tear/episiotomy 307 (80.2) 76 (19.8) 1.37 (0.8–2.2) 0.201

Caesarean section (intact perineum)

Elective 84 (75.0) 28 (25.0) 1.71 (0.9–3.2) 0.087

Emergency 157 (70.7) 65 (29.3) 2.41 (1.4–4.0) 0.001

Forceps (sutured tear/episiotomy) 95 (79.8) 24 (20.2) 1.56 (0.8–2.9) 0.156

Vacuum extraction (sutured tear/episiotomy) 86 (71.1) 35 (28.9) 2.28 (1.3–4.1) 0.005

Prepregnancy dyspareunia

No 679 (81.5) 154 (18.5) 1.0 ref

Yes 210 (66.9) 104 (33.1) 2.09 (1.5–2.8) 0.000

Maternal age at index birth

30–34 years 254 (78.9) 68 (21.1) 1.0 ref

18–24 years 85 (70.3) 36 (29.7) 1.45 (0.9–2.4) 0.165

25–29 years 366 (76.1) 115 (23.9) 1.10 (0.8–1.6) 0.602

35+ years 189 (81.8) 42 (18.2) 0.77 (0.5–1.2) 0.263

Highest educational qualification

University degree 436 (77.0) 130 (23.0) 1.0 ref

Certificate/diploma 226 (76.4) 70 (23.6) 0.91 (0.6–1.3) 0.620

Year 12 165 (81.3) 38 (18.7) 0.69 (0.4–1.1) 0.091

<Year 12 62 (73.8) 22 (26.2) 1.02 (0.6–1.8) 0.938

Maternal fatigue at 18 months postpartum

No 297 (83.0) 61 (17.0) 1.0 ref

Yes 592 (74.8) 200 (25.2) 1.51 (1.1–2.1) 0.018

EPDS ≥13 at 18 months postpartum

No 824 (78.8) 222 (21.2) 1.0 ref

Yes 68 (65.4) 36 (34.6) 1.27 (0.8–2.0) 0.318

Intimate partner abuse in first 12 months postpartum

No 766 (79.3) 200 (20.7) 1.0 ref

Yes 125 (67.6) 60 (32.4) 1.65 (1.1–2.4) 0.009

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

*Excludes women who report giving birth to second baby by 18 months postpartum and denominators vary due to missing values.

emergency caesarean section or vacuum extraction, and women reporting dyspareunia at 18 months postpartum is

somewhat higher for women who had an elective caesarean similar for women who had a spontaneous vaginal birth

section, compared with women who had a spontaneous with and without perineal damage.

vaginal birth with an intact perineum. At 6 months post- Other factors associated with dyspareunia at 18 months

partum, vaginal birth assisted with forceps was also associ- postpartum include prepregnancy dyspareunia, intimate

ated with dyspareunia, but elective caesarean section was partner abuse and maternal fatigue. These results suggest

not. These differences in the pattern of association with that clinicians should be alert to the possibility that inti-

mode of delivery may reflect limited study power for com- mate partner abuse is a potential underlying factor in per-

parisons of these subgroups. Alternatively, it is possible that sisting dyspareunia.

women recover more quickly from forceps than from vac- The finding that breastfeeding is associated with dyspa-

uum extraction, and that women having an elective caesar- reunia in the early postnatal period confirms previous

ean section that do experience postpartum dyspareunia are study findings.1 Women still breastfeeding at 6 months

slow to recover. It is noteworthy that the proportion of postpartum had a higher likelihood of experiencing

676 ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Dyspareunia and childbirth

Table 3. Adjusted odds of dyspareunia at 6 months postpartum associated with mode of delivery, perineal trauma and other risk factors*

Dyspareunia at 6 months Adjusted OR (95% CI) P values

postpartum

No Yes

Mode of delivery and perineal trauma

Spontaneous vaginal birth

Intact perineum/unsutured tear 130 (68.8) 59 (31.2) 1.0 ref

Sutured tear/episiotomy 201 (53.6) 174 (46.4) 2.32 (1.5–3.5) 0.000

Caesarean section (intact perineum)

Elective 72 (68.6) 33 (31.4) 0.76 (0.4–1.4) 0.387

Emergency 133 (59.4) 91 (40.6) 1.83 (1.2–2.9) 0.010

Forceps (sutured tear/episiotomy) 59 (48.0) 64 (52.0) 3.11 (1.9–5.2) 0.000

Vacuum extraction (sutured tear/episiotomy) 45 (40.5) 66 (59.5) 3.36 (2.0–5.8) 0.000

Prepregnancy dyspareunia

No 503 (60.8) 325 (39.2) 1.0 ref

Yes 140 (45.8) 166 (54.2) 1.91 (1.4–2.6) 0.000

Maternal age at index birth

30–34 years 203 (60.1) 135 (39.9) 1.0 ref

18–24 years 77 (59.2) 53 (40.8) 1.39 (0.9–2.3) 0.181

25–29 years 249 (53.4) 217 (46.6) 1.30 (0.9–1.8) 0.118

35+ years 119 (56.7) 91 (43.3) 1.25 (0.8–1.9) 0.293

Highest educational qualification

University degree 293 (53.5) 255 (46.5) 1.0 ref

Certificate/diploma 168 (56.2) 131 (43.8) 1.03 (0.7–1.4) 0.882

Year 12 122 (61.0) 78 (39.0) 0.81 (0.6–1.2) 0.286

<Year 12 62 (68.9) 28 (31.1) 0.61 (0.3–1.1) 0.102

Breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum

No 183 (62.0) 112 (38.0) 1.0 ref

Yes 373 (52.5) 337 (47.5) 1.55 (1.1–2.1) 0.007

Maternal fatigue at 6 months postpartum

No 283 (60.1) 188 (39.9) 1.0 ref

Yes 363 (54.4) 304 (45.6) 1.28 (1.0–1.7) 0.081

EPDS ≥13 at 6 months postpartum

No 598 (57.3) 445 (42.7) 1.0 ref

Yes 47 (48.5) 50 (51.5) 1.62 (1.0–2.7) 0.060

Intimate partner abuse in first 12 months postpartum

No 552 (57.1) 414 (42.9) 1.0 ref

Yes 94 (53.4) 82 (46.6) 1.26 (0.9–1.8) 0.237

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

*Denominators vary due to missing values.

dyspareunia at 6 months postpartum, even after adjusting on subsequent sex. Importantly for the analyses presented

for other maternal factors including mode of delivery and in this paper, the sample was representative in relation to

perineal trauma. mode of delivery.

The recruitment method did result in under-representa-

Strengths and limitations tion of younger women and women born overseas with a

Major strengths of this study are recruitment of a nullipa- non-English-speaking background. However, this is unlikely

rous pregnancy cohort in early pregnancy, frequent follow to have biased the results, as these social characteristics

up and high retention of participants to 18 months post- were unrelated to the primary outcomes reported in the

partum. All of these key features of the design of the study paper. The fact that recruitment was restricted to nullipa-

reduce the likelihood of recall bias, which is a major con- rous women, while very valuable in providing rich detail

cern in much of the previous literature. Additionally, the about the experiences of women having their first baby,

study was designed to facilitate ascertainment and differen- means that we are unable to comment on outcomes follow-

tiation of pain on first vaginal sex after childbirth and pain ing second and subsequent births.

ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 677

McDonald et al.

Interpretation paper for publication. EM and DG were responsible for

The major contribution of this study is that it provides data management.

much more robust evidence than previously available about

the extent and persistence of postpartum dyspareunia, and Funding

associations with mode of delivery and perineal trauma. This research was supported by project grants from the

No other study has undertaken such detailed, frequent and Australian National Health and Medical Research Council

long-term follow up with a sufficiently large nulliparous (ID191222 and ID433006 Melbourne, Australia); a Vic-

cohort recruited in early pregnancy to assess associations Health Public Health Research Fellowship (2002–2006), a

with obstetric risk factors. National Health and Medical Research Council Career

The higher prevalence of persisting dyspareunia in Development Fellowship (ID491205, 2008–2011) and an

women who had an operative birth raises important ques- ARC Future Fellowship (2012–2015) awarded to SB; a La

tions about the longer-term impact of operative procedures Trobe University Postgraduate Scholarship awarded to EM,

on women’s health. Although in a study of this nature we and the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure

cannot be confident in drawing causal inferences, the find- Support Programme.

ings raise important questions about the extent to which

obstetric procedures have long-term consequences for Acknowledgements

women’s health and wellbeing, and whether any of this We are grateful to members of the Maternal Health Study

morbidity could be prevented. It is striking that so few research team who have contributed to data collection and

prospective studies have collected data on the persistence coding (Maggie Flood, Ann Krastev, Renee Paxton, Susan

of dyspareunia beyond 6 months postpartum. The study Perlen, Martine Spaull, Hannah Woolhouse). &

findings highlight the importance of continuing efforts to

improve understanding of postpartum maternal morbidi-

References

ties, including factors that influence severity and persistence

of symptoms. The fact that dyspareunia persists for a sub- 1 Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, Victor C, Thakar R, Manyonda I.

Women’s sexual health after childbirth. BJOG 2000;107:186–95.

stantial proportion of women also points to the need for

2 Brubaker L, Handa VL, Bradley CS, Connolly A, Moalli P, Brown MB,

focusing clinical attention on ways to help women experi- et al. Sexual function 6 months after first delivery. Obstet Gynecol

encing ongoing morbidity, and increased efforts to prevent 2008;111:1040–4.

postpartum morbidity whenever possible. 3 Buhling KJ, Schmidt S, Robinson JN, Klapp C, Siebert G,

Dudenhausen JW. Rate of dyspareunia after delivery in primiparae

according to mode of delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

Conclusions 2006;124:42–6.

4 Gjerdingen DK, Froberg DG, Chaloner KM, McGovern PM. Changes

The findings of this multicentre prospective cohort of nul- in women’s physical health during the first postpartum year. Arch

liparous women suggest that obstetric intervention—specif- Fam Med 1993;2:277–83.

ically vacuum extraction and caesarean section—contribute 5 Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Robbins JM, Kaczorowski J, Jorgensen SH,

Franco ED, et al. Relationship of episiotomy to perineal trauma and

to persisting dyspareunia affecting a significant proportion

morbidity, sexual dysfunction, and pelvic floor relaxation. Am J

of women up to 18 months postpartum. Greater recogni- Obstet Gynecol 1994;171:591–8.

tion and better overall understanding of the role of obstet- 6 Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, Repke JT. Postpartum sexual

ric intervention in contributing to maternal postpartum functioning and its relationship to perineal trauma: a retrospective

morbidities, and ways to prevent postpartum dyspareunia cohort study of primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2001;184:881–90.

where possible, are warranted.

7 Safarinejad MR, Kolahi AA, Hosseini L. The effect of the mode of

delivery on the quality of life, sexual function, and sexual

Disclosure of interests satisfaction in primiparous women and their husbands. J Sex Med

None disclosed. 2009;6:1645–67.

8 Brown S, Lumley J, McDonald E, Krastev A. Maternal Health Study:

a prospective cohort study of nulliparous women recruited in early

Contribution to authorship pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2006;6:12.

EM planned and conducted the analyses and wrote the 9 Gartland D, Lansakara N, Flood M, Brown S. Assessing obstetric risk

paper. SB wrote the study protocol, took primary responsi- factors for maternal morbidity: congruity between medical records

bility for the design and conduct of the study, contributed and mothers’ reports of obstetric exposures. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2012;206:152.e1–e10.

to analysis and interpretation of data and contributed to

10 Brown S, Gartland D, Donath S, MacArthur C. Fecal incontinence

writing the paper. DG and RS contributed to interpretation during the first 12 months postpartum: complex causal pathways

of data and reviewed and commented on drafts of the and implications for clinical practice. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:

paper. All authors have approved the final draft of the 1–10.

678 ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Dyspareunia and childbirth

11 Brown WJ, Bryson L, Byles JE, Dobson AJ, Lee C, Mishra G, et al. 17 Brown SB. Maternal Health Study. 2014 [www.mcri.edu.au/media/

Women’s Health Australia: recruitment for a national longitudinal 987190/031570_pregnancy_v10_f_a_.pdf]. Accessed 17 December

cohort study. Women Health 1999;28:23–40. 2014.

12 Cox J. Perinatal Mental Health: A Guide to the Edinburgh Postnatal 18 StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station,

Depression Scale (EPDS). London: Gaskell, 2003. TX: StataCorp LP, 2013.

13 Hegarty K, Bush R, Sheehan M. The composite abuse scale: further 19 Brown S, Donath S, MacArthur C, McDonald E, Krastev A. Urinary

development and assessment of reliability and validity of a incontinence in nulliparous women before and during pregnancy:

multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Int Urogynecol J

Vict 2005;20:529–47. 2010;21:193–202.

14 Hegarty KL, Sheehan M, Schonfeld C. A multidimensional definition 20 Richters J, Grulich AE, de Visser RO, Smith AMA, Rissel C. Sex in

of partner abuse: development and preliminary validation of the Australia: sexual difficulties in a representative sample of adults [The

Composite Abuse Scale. J Fam Violence 1999;14:399–414. Australian Study of Health and Relationships, a survey of 19,307

15 Woolhouse H, Gartland D, Perlen S, Donath S, Brown SJ. Physical people aged 16–59 years which had a broad focus across many

health after childbirth and maternal depression in the first 12 aspects of sexual and reproductive health.]. Aust N Z J Public Health

months post partum: results of an Australian nulliparous pregnancy 2003;27:164–70.

cohort study. Midwifery 2014;30:378–84. 21 Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United

16 McDonald E, Brown S. Does method of birth make a difference to States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537–44.

when women resume sex after childbirth? BJOG 2013;120:823–30.

ª 2015 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 679

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Chapter 35 - Her Triplet Alphas - Novel SquareDokument5 SeitenChapter 35 - Her Triplet Alphas - Novel SquareeiseNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Family Structure, Characteristics and DynamicsDokument6 SeitenFamily Structure, Characteristics and DynamicsErilyn Leigh ManaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- (GYNE) 3.05 Gestational Trophoblastic Disease - Co-HidalgoDokument7 Seiten(GYNE) 3.05 Gestational Trophoblastic Disease - Co-HidalgoMeg MisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR Template - BeghDokument2 SeitenDR Template - BeghJayran Bay-an100% (1)

- Children and Adolescents of Lesbian and Gay ParentsDokument5 SeitenChildren and Adolescents of Lesbian and Gay ParentsshyznogudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contraceptive SuppositoryDokument3 SeitenContraceptive SuppositoryMonica GereroNoch keine Bewertungen

- (#5) Benign and Malignant Ovariaan TumorsDokument35 Seiten(#5) Benign and Malignant Ovariaan Tumorsmarina_shawkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutritional Strategies For Optimizing Reproductive Performance of SowDokument18 SeitenNutritional Strategies For Optimizing Reproductive Performance of Sowanon_151103933Noch keine Bewertungen

- BrochureDokument3 SeitenBrochureapi-218300213Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Controversy Over Stem Cell ResearchDokument4 SeitenThe Controversy Over Stem Cell ResearchGra BohórquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 Lesson 1Dokument3 SeitenChapter 2 Lesson 1John Carldel VivoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bsc1102 Lab Power PointDokument26 SeitenBsc1102 Lab Power PointKris StephensNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV European English Fabiana Interlandi 7Dokument3 SeitenCV European English Fabiana Interlandi 7Andrea VetranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Tumor Genital WanitaDokument115 Seiten2 Tumor Genital WanitaKhafidz Asy'ariNoch keine Bewertungen

- b1 ChecklistDokument2 Seitenb1 ChecklistRoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Bulletin: Vaginal Birth After Previous Cesarean DeliveryDokument14 SeitenPractice Bulletin: Vaginal Birth After Previous Cesarean DeliveryFernando González PeruggiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sci5 q2 Mod1 Human Reproductive System Loida Pineda Revised Bgo v1Dokument20 SeitenSci5 q2 Mod1 Human Reproductive System Loida Pineda Revised Bgo v1Louie Raff Michael EstradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pollination and Its AgentsDokument6 SeitenPollination and Its AgentsdebbyhooiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition: Bilateral Tubal Ligation (BTL)Dokument5 SeitenDefinition: Bilateral Tubal Ligation (BTL)Reginald UyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Babson and Benda's ChartDokument10 SeitenBabson and Benda's ChartZasly WookNoch keine Bewertungen

- SampleDokument255 SeitenSampleshivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SemenDokument6 SeitenSemenMarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Issues IVFDokument1 SeiteEthical Issues IVFBasinga OkinamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Planning Service Record (Form 1)Dokument32 SeitenFamily Planning Service Record (Form 1)Kareen Xc Mae BerdosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hormones FTMDokument16 SeitenHormones FTMapi-221867127Noch keine Bewertungen

- SDKI 2002 - Kuesioner PriaDokument19 SeitenSDKI 2002 - Kuesioner Priakiki rizkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communities WorksheetDokument2 SeitenCommunities WorksheetJamie MakrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uso Medicinal de Cordia LuteaDokument12 SeitenUso Medicinal de Cordia LuteaBelen GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barr Body and HermaphroditismDokument41 SeitenBarr Body and HermaphroditismTamjid KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ALE 2014 Animal Science Autosaved - Docx 2003409664Dokument85 SeitenALE 2014 Animal Science Autosaved - Docx 2003409664Haifa KalantunganNoch keine Bewertungen