Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Lady of Animals

Hochgeladen von

adimarinCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Lady of Animals

Hochgeladen von

adimarinCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

5280 LADY OF THE ANIMALS

(wings, beaks, snakelike bodies, bear heads, and the like) are dess of the sea and sea animals, especially seals, walruses, and

common in the Neolithic era in Old Europe (6500–3500 whales. To the Hopi she is Kokyanguruti, or Spider Woman,

BCE) and elsewhere. Their origins can probably be traced to the creatress and guardian of Mother Earth, who presides

the Upper Paleolithic (30,000–10,000 BCE). The Lady of the over emergence and return. To the Algonquin she is No-

Animals is found in almost all cultures. komis, the Grandmother, who feeds plants, animals, and hu-

mans from her breasts. In Mexico she is Chicomecoatl, Heart

Because prehistory has left no written records, interpre-

of the Earth, with seven serpent messengers. In Africa she is

tation of the meaning of the earliest images called Lady of

Osun with peacocks and Mami Wata with snakes. In Chris-

the Animals cannot be certain. She was known to her earliest

tianity her memory remains in the images of Eve with the

worshipers as “Mother of All the Living” (a phrase used to

snake and Mary with the dove. She lingers, too, in such folk

refer to Eve in Genesis 3:20), as “Creatress,” “Goddess,” “An-

images as Mother Goose, the Easter bunny, and the stork

cestress,” “Clan Mother,” “Priestess,” by a place or personal

who brings babies.

name, or, simply, as “Mother,” “Ma,” or “Nana.” Whatever

she was called, the Lady of the Animals is an image of the Composed between 800 and 400 BCE, the Homeric

awesome creative powers of women and nature. The term Hymns, some of which may reflect earlier religious concep-

Mother of All the Living may in fact be more accurately de- tions, provide two powerful written images of the Lady of

scriptive of the wide range of creative powers depicted in im- the Animals that can help us interpret earlier drawn and

ages commonly called “Lady of the Animals.” sculpted images. In the “Hymn to Earth” she is “well-

A very early sculpture of a Lady of the Animals was founded Earth, mother of all, eldest of all beings. She feeds

found in Çatalhüyük, a Neolithic site in central Anatolia all creatures that are in the world, all that go upon the goodly

(central Turkey), dating from 6500 to 5650 BCE. Made of land, and all that are in the paths of the seas, and all that fly.”

baked clay, she sits on a birth chair or throne. She is full- In the “Hymn to the Mother of the Gods” she is “well-

breasted and big of belly, and she seems to be giving birth, pleased with the sound of rattles and timbrels, with the voice

for a head (not clearly human) emerges from between her of flutes and the outcry of wolves and bright-eyed lions, with

legs. Her hands rest on the heads of two large cats, probably echoing hills and wooded coombes.”

leopards, that stand at her sides. From Sumer (c. 2000 BCE), In these songs the Lady of the Animals is cosmic power,

a Lady of the Animals appears in a terra-cotta relief, naked mother of all. The animals of the earth, sea, and air are hers,

and winged, with two owls at her sides and her webbed feet and the wildest and most fearsome animals—wolves and

resting on the backs of two monkeys. From Minoan Crete lions, as well as human beings—praise her with sounds. The

comes a small statue unearthed in the treasury of the new pal- Lady of the Animals is also earth, the firm foundation under-

ace of Knossos (c. 1700–1450 BCE); staring as if in trance, girding all life. The hills and valleys echo to her. In these im-

she holds in her outstretched arms two striped snakes; her ages she would not be called a “lady of the plants,” which

breasts are exposed, and a small snake emerges from her suggests that the conceptions reflected in these hymns may

bodice. have originated in preagricultural times. Jane Harrison

In Ephesus, an enormous image of a Lady of the Ani- (1903) has suggested that the “lady of the wild things” be-

mals dominated the great temple of Artemis or Diana (re- comes “lady of the plants” only after human beings become

built 334 BCE and known as one of the seven wonders of the agriculturalists.

ancient world). Her many egg-shaped breasts symbolized her THE PALEOLITHIC AGE. Marija Gimbutas, Gertrude R.

nurturing power, while the signs of the zodiac forming her Levy, and E. O. James are among those who concur with

necklace expressed her cosmic power. Her arms were extend- Harrison in tracing the Goddess symbolism of the Neolithic

ed in a gesture of blessing, and her lower body, shaped like and later periods to the Upper Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age

the trunk of the tree of life, was covered with the heads of (c. 30,000–10,000 BCE). Therefore, we must ask whether the

wild, domestic, and mythical animals. At her feet were bee- image of the Lady of the Animals also goes back to the Paleo-

hives; at her sides, two deer. The city crowned her head. lithic era.

In Asia Minor the Lady of the Animals is known as Ku-

Many small figures of so-called pregnant Venuses have

baba or Cybele and is flanked by lions. In Egypt she is Isis

been dated to the Upper Paleolithic. Abundantly fleshed

the falcon or Isis with falcon wings and a uraeus (snake)

with prominent breasts, bellies, and pubic triangles, they

emerging from her forehead; she is also Hathor the cow god-

were often painted with red ocher, which seems to have sym-

dess or Hathor with the cow horns. In Canaan she is Ashto-

bolized the blood of birth, the blood of life. These images

ret or Astarte holding snakes and flowers in her hands. In

have been variously interpreted.

India she is Tārā or Parvati astride a lion or Durgā riding a

lion into battle and slaying demons with the weapons in her These images may be understood in relation to the cave

ten arms. In Japan she is Amaterasu, the sun goddess, with art of the Paleolithic era. Paleolithic peoples decorated the

her roosters that crow at dawn and her messengers the crows. labyrinthine paths and inner recesses of caves with abstract

In China she is Kwan Yin standing on a dragon that symbol- line patterns and with drawings and paintings of animals,

izes good fortune. To the Inuit (Eskimo) she is Sedna, god- such as bison and deer. Small human figures, both male and

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGION, SECOND EDITION

LADY OF THE ANIMALS 5281

female, were sometimes painted in the vicinity of the much nature, Old Europeans honored humanity’s participation in,

larger animals. The drawings and paintings of these animals, and connection to, nature’s cycles of birth, death, and renew-

and the rituals practiced in the inner reaches of the caves, al. A combination of human and animal forms expressed her

have often been understood as hunting magic, done to en- power more fully than the human figure alone. Many ani-

sure the capture of prey. But Gertrude R. Levy argues that mals, such as the caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly, the bird that

the purposes of these rituals cannot have been simple “magic flies in the air and walks on the earth, and the snake that

compulsion” but must have involved a desire for a “participa- crawls above and below the earth, have powers that humans

tion in the splendor of the beasts” (Levy, 1963, p. 20). If, lack.

as was surely the case later, Paleolithic peoples also under-

stood the caves and their inner recesses to be the womb of In Old Europe, the creator goddess who appeared with

Mother Earth, then is it not possible to recognize the ani- animal characteristics was the primary image of the divine.

conic image of the Lady of the Animals in the womb-cave According to Gimbutas, the “male element, man and animal,

onto which the animals were painted? And can we not also represented spontaneous and life-stimulating—but not life-

see the Lady of the Animals in the well-known Paleolithic generating—powers” (Gimbutas, 1982, p. 9). Gimbutas

carving found in Laussel of an unclothed full-bodied woman stated that women were symbolically preeminent in the cul-

holding a bison horn? Must we not, then, interpret prehistor- ture and religion of Old Europe. Although women were hon-

ic rituals in the labyrinthine recesses of caves as a desire to ored, the culture itself was not “matriarchal,” as women did

participate in the transformative power of the creatress, the not dominate men but shared power with them. It is general-

mother of all, the Lady of the Animals? ly thought that women invented agriculture, which led to the

Neolithic “revolution.” As the gatherers of plant foods in Pa-

OLD EUROPE. Anthropomorphic images of the Lady of the leolithic societies, women would have been the ones most

Animals appear in abundance in the Neolithic, or early agri- likely to notice the connection between the dropping of a

cultural period, which began about 9000 BCE in the Near seed and the springing up of a new plant. Women are also

East. Marija Gimbutas coined the term Old Europe to refer the likely inventors of pottery and weaving in the Neolithic

to distinctive Neolithic and Chalcolithic (or Copper Age) era, for pottery was used primarily for women’s work of food

civilizations of Central and Southern Europe that included preparation and food storage, and weaving clothing and

the lands surrounding the Aegean and Adriatic Seas and their other items for use in the home is women’s work in almost

islands and extended as far north as Czechoslovakia, south- all traditional cultures. Each of these inventions of the Neo-

ern Poland, and the western Ukraine. There is reason to be- lithic era is a mystery of transformation—seed into plant into

lieve that Neolithic-Chalcolithic cultures developed along harvest, earth and fire into pot, wool and flax into clothing

similar lines in other parts of the world, including, for exam- and blankets. If these mysteries were understood to have

ple, Africa, China, the Indus Valley, and the Americas. been given to women by the goddess and handed down from

mother to daughter, this would have provided a material and

In Old Europe (c. 6500–3500 BCE), Gimbutas found

economic basis for the preeminence of the female forms in

a pre–Bronze Age culture that was “matrifocal and probably

religious symbolism.

matrilinear, agricultural and sedentary, egalitarian and peace-

ful” (Gimbutas, 1982, p. 9). This culture was presided over ÇATALHÜYÜK. The culture of Çatalhüyük, excavated by

by a goddess conceived as the source and giver of all. Al- James Mellaart, seems similar to that found by Gimbutas in

though originally this goddess did not appear with animals, Old Europe. Like Gimbutas, Mellaart found a culture where

she herself had animal characteristics. One of her earliest women and goddesses were prominent, a culture that he be-

forms was as the snake and bird goddess, who was associated lieved to have been matrilineal and matrilocal and peaceful

with water and represented as a snake, water bird, duck, and in which the goddess was the most powerful religious

goose, crane, diving bird, or owl or as a woman with a bird image. In Çatalhüyük the Lady of the Animals was preemi-

head or birdlike posture. She was the creator goddess, the nent. Wall paintings in the shrines frequently depict a god-

giver of life. dess, with outstretched arms and legs, giving birth, some-

times to bulls’ or rams’ heads. Other shrines depict rows of

The goddess of Old Europe was also connected with the bull heads with rows of breasts; in one shrine, rows of breasts

agricultural cycles of life, death, and regeneration. Here she incorporate the lower jaws of boars or the skulls of foxes,

appeared as, or was associated with, bees, butterflies, deer, weasels, or vultures. Besides the small figure, mentioned ear-

bears, hares, toads, turtles, hedgehogs, and dogs. The domes- lier, of the seated goddess, hands on her leopard companions,

ticated dog, bull, male goat, and pig became her compan- giving birth, Mellaart also found a sculpture of a woman in

ions. To the Old Europeans she was not a power transcen- leopard-skin robes standing in front of a leopard. One shrine

dent of the earth but rather the power that creates, sustains, simply depicts two leopards standing face-to-face.

and manifests itself in the variety of life-forms within the

earth and its cycles. Nor did the goddess represent “fertility” Wall paintings of bulls were also frequent at the site.

in a narrow sense of human, animal, and plant reproduction; Mellaart believes that the religion of Çatalhüyük was cen-

rather she was the giver of life, beauty, and creativity. Instead tered on life, death, and rebirth. The bones of women, chil-

of celebrating humanity’s uniqueness and separation from dren, and some men were found buried under platforms in

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGION, SECOND EDITION

5282 LADY OF THE ANIMALS

the living quarters and in the shrines, apparently after having the power manifesting itself in the cycles of nature. Thus,

been picked clean by vultures. According to Mellaart, vul- Cretan pottery and frescoes abound in rhythmical forms; im-

tures were also associated with the goddess, thus indicating ages of waves, spirals, frolicking dolphins, undulating snakes,

that she was both giver and taker of life. and graceful bull leapers are everywhere. The Minoans cap-

tured life in motion. Exuberant movement must have repre-

As Mellaart states in Earliest Civilizations of the Near

sented to them the dance of life, the dance of the Mother

East (1965), the land-based matrifocal, sedentary, and peace-

of All the Living, the Lady of the Animals.

ful agricultural societies of the Near East were invaded by

culturally inferior northern peoples starting in the fifth and GREECE. Eventually all the Neolithic and (isolated) Bronze

fourth millennia BCE. These invaders and others who fol- Age cultures in which the creator goddess was supreme fell

lowed set the stage for the rise of the patriarchal and warlike to patriarchal and warlike invaders. By the time of decipher-

Sumerian state about 3500 BCE. According to Gimbutas, the able written records, we begin to see evidence that societies

patriarchal, nomadic, and warlike proto-Indo-Europeans in- are ruled by warrior kings; goddesses are no longer supreme

filtrated the matrifocal agricultural societies of Old Europe and women are subordinated by law to their husbands. On

between 4500 and 2500 BCE. As a result, in both the Near mainland Greece, Apollo took over the holy site of Delphi,

East and Old Europe, the creator goddess was deposed, slain, sacred first to Mother Earth and her prophetess, after slaying

or made wife, daughter, or mother to the male divinities of the python, the sacred snake that guarded the sanctuary. This

the warriors. The Lady of the Animals did not disappear (re- act can be compared to Marduk’s slaying of the female sea

ligious symbols linger long after the end of the cultural situa- snake (or dragon) Tiamat, to the association of the formerly

tion that gave rise to them), but her power was diminished. sacred snake with sin and evil in Genesis 2–3, to St. George’s

slaying the dragon-snake, and to St. Patrick’s driving the

MINOAN CRETE. In the islands, which were more difficult

snakes out of Ireland.

to invade, the goddess-centered cultures survived and devel-

oped into Bronze Age civilizations. In Crete the Lady of the According to the Olympian mythology found in

Animals remained supreme until the Minoan civilization fell Homer, Hesiod, and the Greek tragedies, Zeus, the Indo-

to the Mycenaeans about 1450 BCE. In the old and new pal- European sky God, is named father and ruler of all the gods

ace periods of Minoan Crete (c. 2000–1450 BCE), a highly and goddesses. Hera, an indigenous goddess whose sanctuary

developed pre-Greek civilization based on agriculture, arti- at Olympia was older than that of Zeus, becomes his never

sanship, and trade emerged. From existing archaeological ev- fully subdued wife. Athena is born from the head of Zeus,

idence (Linear A, the written language of the Minoans, has but her mountain temples (for example, the Parthenon) and

not been translated), it appears that women and priestesses her companions, the owl and snake, indicate her connection

played the prominent roles in religious rituals. There is no to the mother of the living, the Lady of the Animals. Aphro-

evidence that women were subordinate in society. Indeed, dite retains her connection to the dove and the goose. Arte-

there is no clear evidence that the “palaces” were royal resi- mis is the goddess of the untamed lands, mountain forests,

dences. The celebrated throne of “King Minos,” found by and wild animals such as bears and deer. Although she is

excavator Arthur Evans, is now thought by several scholars named a virgin goddess, she aids both human and animal

(including Nano Marinatos, Jacquetta Hawkes, Stylianous mothers in giving birth. Of all the Olympian goddesses, Ar-

Alexiou, Helga Reusch, and Ruby Rohrlich) to have been oc- temis retains the strongest connection to the Mother of All

cupied by a priestess or a queen, while others suggest that it the Living, the Lady of the Animals.

dates from the time of Mycenean occupation of Knossos. What happened to the goddesses in ancient Greece hap-

In Minoan Crete the goddess was worshiped at natural pened elsewhere. They were slain, tamed, made defenders of

sites, such as caves or mountaintops, and in small shrines in patriarchy and war, or relegated to places outside the city.

the palaces and homes. She had attributes of both a moun- Yet the attempt to banish the image of the Mother of All the

tain mother and a Lady of the Animals. In Crete the Lady Living, the Lady of the Animals, was never completely suc-

of the Animals is commonly found in the company of snakes, cessful. Like an underground spring, she burst forth in im-

doves, and trees, particularly the olive tree, which may have ages of Mary and the female saints throughout Christian his-

first been cultivated in Crete. In a seal ring found in the Dic- tory. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries she has

tean cave, the goddess appears with bird or snake head be- reemerged in the work of feminist artists and in a widespread

tween two winged griffins, the same animals that flank the Goddess movement.

throne of “Minos.”

SEE ALSO Animals; Goddess Worship, overview article; Lord

Other pervasive symbols in Crete include the stylized of the Animals; Megalithic Religion; Prehistoric Religions.

horns of consecration, which evoke not only the cow or bull

but also the crescent moon, the upraised arms of Minoan BIBLIOGRAPHY

goddesses and priestesses, and the double ax, which may The reconstruction of Old European religion and culture by

originally derive from doubling the sacred female triangle, Marija Gimbutas can be found in The Language of the God-

the place where life emerges. Heiresses and heirs to Neolithic dess (San Francisco, 1989) and The Civilization of the Goddess

religion, the Minoans continued to understand the divine as (San Francisco, 1991); a summary of her conclusions can be

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGION, SECOND EDITION

LAESTADIUS, LARS LEVI 5283

found in “Women and Culture in Goddess-Oriented Old and a Swedish father. After Laestadius’s alcoholic father lost

Europe,” in The Politics of Women’s Spirituality, edited by his job, the family went to live with Lars’s half-brother, Carl

Charlene Spretnak (Garden City, N.Y., 1982), pp. 22–31. Erik, a Lutheran pastor in Kvikkjokk. Carl Erik was an also

Gimbutas’s work has incited scholarly controversy, some of amateur botanist and encouraged his younger brother’s in-

which may reflect a backlash against feminist uses of her terest in the subject.

work; see From the Realm of the Ancestors, edited by Joan

Marler (Manchester, Conn., 1997); Ancient Goddesses, edited When Lars was 16, he entered the Härnösand Gymnasi-

by Lucy Goodison and Christine Morris (Madison, Wis., um. Three years later his avid interest in botany led him to

1998); and Varia on the Indo-European Past (Journal of Indo- take part in a botanical excursion to Helgoland, Norway;

European Studies Monograph 19), edited by Miriam Robbins when his report of the journey was published, the Swedish

Dexter and Edgar C. Polome (Washington, D.C., 1997). Academy of Science and Letters was so impressed that it

The works of James Mellaart, particularly Çatal Hüyük: A

promised to underwrite his future excursions. In 1820 La-

Neolithic Town in Anatolia (New York, 1967) and Earliest

Civilizations of the Near East (London, 1965), are essential

estadius enrolled at the University of Uppsala, where he stud-

for understanding Goddess symbolism in Neolithic civiliza- ied botany and theology—excelling in both.

tion. For a brief overview of reconsiderations of Mellaart’s He was ordained in1825, and became the vicar of Kares-

work, see Michael Balter, “The First Cities: Why Settle uando a year later. During his years as a minister, Laestadius

Down? The Mystery of Communities,” Science, November

continued his botanical studies, joining the scientific society

20, 1998, pp. 1442–1443; visit the website of the new exca-

of Uppsala publishing articles on the flora of Samiland, and

vation, “Çatalhöyük” at http://catal.arch.cam.ac.uk/catal/

catal.html. Gertrude R. Levy’s Religious Conceptions of the serving as botanist during the years 1838 to 1840 on a

Stone Age (New York, 1963), originally titled The Gate of French botanical expedition to the region.

Horn (London, 1948), remains a valuable resource on prehis- In 1844, after nineteen years in the ministry, Laestadius

toric religion, especially on the question of cave symbolism. underwent a significant “conversion” from inside the Luther-

Jane E. Harrison’s Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

an Church from its “highly churchly” mainstream to the pi-

(1903; reprint, Atlantic Highlands, N.J., 1981) has never

been superseded as a comprehensive reference on Greek reli- etist movement of the “Readers.” He became a revivalist

gion with particular emphasis on the prepatriarchal origins minister, campaigning for temperance, organizing of educa-

of goddesses. Jacquetta Hawkes presents a dramatic contrast tion for the Sami people, and serving as a newspaper editor.

between patriarchal and prepatriarchal Bronze Age societies His dynamic evangelism won him many followers, and even-

in Dawn of the Gods (New York, 1968). Nano Marinatos tually prompted a following that spread throughout the re-

presents an original scholarly reconstruction in Minoan Reli- gion. This religious movement, now known as Laestadian-

gion (Columbia, S.C., 1993). For a general overview of God- ism, began among the Sami Readers in Karesuando and

dess symbolism in many cultures, E. O. James’s The Cult of spread to the Finns at Pajala in the Tornio river valley. Sami

the Mother Goddess (New York, 1959) remains extremely use- and Finnish immigrants brought Laestadianism to America,

ful. Erich Neumann’s The Great Mother, 2d ed., translated

particularly northern states like Michigan, Minnesota, and

by Ralph Manheim (New York, 1963), contains a wealth of

information mired in androcentric Jungian theory. Buffie

Oregon. Laestadius’s role as founder of the biggest religious

Johnson’s Lady of the Beasts (San Francisco, 1998) is also movement in northern Scandinavia eventually overshad-

written from a Jungian and therefore ahistorical perspective. owed his scholarly career, which expanded into several disci-

Anthropological research on Goddess symbolism and ritual plines:

in numerous cultures, most of them contemporary, can be

1. As an ecologist and botanist he was the successor to

found in Mother Worship, edited by James J. Preston (Chapel

Hill, N.C., 1982). The Book of the Goddess: Past and Present,

Carolus Linnaeus; he took part in Prof. Wahlenberg’s botan-

edited by Carl Olson (New York, 1983), presents research, ical expeditions from Skåne to Lapland. His unique herbari-

some of it feminist, on historical and contemporary Goddess um, containing 6,700 plants, was sold to the French Acade-

religions. Women and Goddess Traditions in Antiquity and my after his death.

Today, edited by Karen King (Minneapolis, 1997), addresses 2. As a theologian and religious philosopher Laestadius

the role of women in Goddess religions. The emergence of

used his considerable knowledge of Enlightenment psychol-

Goddess symbolism in contemporary women’s art and spiri-

tuality is discussed in Elionor Gadon, Once and Future God- ogy, philosophy, and theology to preach forceful and dynam-

dess (San Francisco, 1989). ic sermons against alcohol and other social eveils. He pub-

lished many of these, including his pastoral thesis Crapula

CAROL P. CHRIST (1987 AND 2005) mundi (Hangover of the world, Hernoesandie, 1843), the

three-volume book Dårhushjonet (The madhouse inmate,

written before 1851), as well as sermons in Finnish, Swedish,

and Sami. Many of these writings expressed his protest

LAESTADIUS, LARS LEVI (1800–1861), Sami

against the spiritually dead doctrinalism taught by traditional

minister, writer, ecologist, mythologist, and ethnographer

church leaders.

who became the founder of Laestadian Lutheran revivalist

movement. Laestadius was born January 10, 1800, in the 3. Laestadius was a philologist of some stature; in addi-

Swedish Lappland village town of Jäkkvik to a Sami mother tion to his mother’s Southern Sami tongue, he spoke Pite

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGION, SECOND EDITION

5284 LĀHORĪ, MUH: AMMAD EALĪ

Sami and Finnish. He learned the latter two to be able to BIBLIOGRAPHY

preach in those languages. He transcribed Pite and Luleå Franzén, Olle. Naturalhistorikern Lars Levi Laestadius. Tornedali-

Sami using his own “Lodge Lappish” Sami-based ortho- ca 15. Luleå, 1973.

graphy. Jonsel, Bengt, et al., eds. Lars Levi Læstadius: botaniker-lingvist-

4. Laestadius was an ethnographer, mythographer, and etnograf-teolog. Oslo, 2000.

a mythologist of the Sami people. He collected information Laestadius, Lars Levi. Dårhushjonet. In Suomen Kirkkohistorial-

about the ancient Sami, and compiled folk beliefs and leg- lisen Seuran toimituksia L:1, 2, 3. Vasa (1949), Åbo (1964).

ends into a system he called a mythology; and as mythogra- Laestadius, Lars Levi. Fragmenter i lappska mythologien. In Svenska

pher used this mythology to write a history for the Sami. His landsmål och svenskt folkliv, B 61. Uppsala, 1959.

achievement as mythologist and ethnographer, Fragmenter i Laestadius, Lars Levi. Hulluinhuonelainen. Helsinki, 1968.

lappska mythologien (Fragments in Lapp mythology), was fi-

Laestadius, Lars Levi. Katkelmia lappalaisten mythologiasta. Tal-

nally translated into English in 2002. This manuscript, writ-

linn, 1994.

ten between1840 and 1845, was not even published fully in

Swedish until 1997. Laestadius, Lars Levi. Fragments in Lappish Mythology. Edited by

Juha Pentikäinen, translated by Börje Vähämäki. Beaverton,

Laestadius did field work in the heart of Sami territory 2002.

as rector of Karesuando and inspector of Sami parishes in

Larsson, Berngt. Lars Levi Laestadius—Hans liv och verk & den la-

Sweden. In these capacities, he visited every lodge in Swedish estadianska väckelsen. Skellefteå, 1999.

Lapland, as he stated in the Fragmenter preface. Both this

work and Crapula mundi were written during his religious Norderval, O⁄ivind og Nesset, Sigmund, ed. Vekkelse og vitenskap.

Lars Levi Læstadius 200 år. Tromso⁄ , 2000.

conversion.

Pentikäinen, Juha. “Lars Levi Laestadius Revisited: A Lesser-

As a religious man he lived wholeheartedly inside the

Known Side of the Story.” In Exploring Ostrobothnia, edited

“interior household of the Sami,” as he called their world by Börje Vähämäki (Special Issue of Journal of Finnish

view—or more properly their religion. His 1845 letter to an- Studies Vol. 2). Toronto, 1998.

other Lapp mythologist, Jacob Fellman (1795–1875), rector

of Utsjoki, offers evidence of the change already begun with- JUHA PENTIKÄINEN (2005)

in him: “I can no longer undertake any further actions with

regard to this worthy manuscript, because my attention has

become directed elsewhere and been overwhelmed by mat- LĀHORĪ, MUH: AMMAD EALĪ (1874–1951),

ters belonging to the sphere of religion, which seem to me scholar of Islam and founder of the Lāhorı̄ branch of the

to be considerably more important than mythology.” Ah: madı̄yyah movement. Born in Murar (Kapurthala),

Laestadius’s writings in Latin, Swedish, Finnish and India, Lāhorı̄ completed advanced degrees in English (1896)

Sami are extensive. His Sami-language works, Hålaitattem and law (1899) in Lahore. His life and works are closely in-

Ristagase ja Satte almatja kaskan (1839), a talk between a tertwined with the Ah: madı̄yyah (also known as Qādiyānı̄)

Christian and an ordinary man, and Tåluts Suptsahah, Jub- movement, a minor sect of Islam founded in 1889 by

mela pirra ja Almatji pirra (1844), an ancient tale about God Ghulām Ah: mad (c. 1839–1908), at whose suggestion

and man, make him one of the first Sami writers. Fragmenter Lāhorı̄ undertook his two major works, a translation of the

i lappska mythologien was originally produced for J. P. Gai- QurDān and The Religion of Islam. In 1902, Lāhorı̄ was ap-

mard, leader of Laestadius’s 1838 royal French arctic expedi- pointed co-editor of the Ah: madı̄yyah periodical, Review of

tion to Scandinavia, the Faroes, Iceland, and Spitzbergen. Religions, through which he propagated the movement’s

Both Gaimard and historian Xavier Marmier recognized La- news and views to the non-Muslim world. This appointment

estadius’ knowledge of Lappish history and lore. Mythology marked the beginning of Lāhorı̄’s prolific career. He translat-

and history are intermingled in Fragmenter; the borderline ed Ghulām Ah: mad’s writings into English, defended his

between the two was extremely vague. views in the face of the Sunnı̄ majority’s growing opposition,

Part I of Fragmenter, “Gudalära” (Doctrine on divinity), and wrote on various aspects of Islam.

was written in 1840; the next three chapters, including one In 1914, with the death of Ghulām Ah: mad’s successor,

called “Comments to Fellman” were completed five years Nūr al-Dı̄n—a prominent scholar of QurDān considered the

later. The other parts are offer-lära (sacrifice), spådomslära mastermind of the Ah: madı̄yyah movement by its oppo-

(prophesy), Lapp nåjdtro (shamanism), and valda stycken af nents—the community split over doctrinal issues such as

Lapparnes Sagohäfde (selection of Lappish folk tales). Ghulām Ah: mad’s claim of prophethood. Lāhorı̄ headed the

Laestadius’s Fragmenter details his vast knowledge of the splinter group, the Ah: madı̄yyah Anjuman-i IshaEat-Islam,

Sami people, languages, and religion. His careful criticism Lahore, known as the Lāhorı̄ group, which regarded Ghulām

and field observations make him one of the founders of the Ah: mad a reformer (mujaddid), not the prophet. This group

Northern Ethnography school. was more liberal and closer to the mainstream of Sunnı̄

Islam, but also more aggressive in its outreach and more

SEE ALSO Finno-Ugric Religions; Sami Religion. vocal in explaining its doctrinal differences with the parent

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGION, SECOND EDITION

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- RamaDokument1 SeiteRamaadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- TurtleDokument2 SeitenTurtleadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- BearsDokument4 SeitenBearsadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- HermeneuticsDokument7 SeitenHermeneuticsadimarin100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- C.B. Knights-Masculinities in Text and Teaching (2008)Dokument258 SeitenC.B. Knights-Masculinities in Text and Teaching (2008)adimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- VrtraDokument2 SeitenVrtraadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Baba YagaDokument2 SeitenBaba YagaadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- JanusDokument1 SeiteJanusadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- BaalDokument2 SeitenBaaladimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Ancient Greek Submission WrestlingDokument37 SeitenAncient Greek Submission Wrestlingiceberg99Noch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- IncantationDokument5 SeitenIncantationadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Anamnes IsDokument10 SeitenAnamnes IsadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- GamblingDokument6 SeitenGamblingadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- JaguarsDokument2 SeitenJaguarsadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Kuruksetra PDFDokument1 SeiteKuruksetra PDFadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- History of Indian Religion StudyDokument16 SeitenHistory of Indian Religion StudyadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- FravashisDokument1 SeiteFravashisadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- MonstersDokument4 SeitenMonstersadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freyja: Norse Goddess of Love, Fertility, and DeathDokument3 SeitenFreyja: Norse Goddess of Love, Fertility, and DeathadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- IncantationDokument5 SeitenIncantationadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- AmuletsDokument4 SeitenAmuletsadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- CURSING AND TABELLAE DEFIXIONESDokument12 SeitenCURSING AND TABELLAE DEFIXIONESadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- FolkloreDokument9 SeitenFolkloreadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Human Sacrifice: An OverviewDokument10 SeitenAncient Human Sacrifice: An OverviewadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Arjuna: The Ideal Warrior and Devotee in the MahabharataDokument2 SeitenArjuna: The Ideal Warrior and Devotee in the MahabharataadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chinghis KhanDokument2 SeitenChinghis KhanadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balarama Si BaldrDokument2 SeitenBalarama Si BaldradimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Culture HeroesDokument3 SeitenCulture HeroesadimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- BaalDokument2 SeitenBaaladimarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senior Secondary Science Admission TestDokument14 SeitenSenior Secondary Science Admission TestMohan SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Attendance RecordsDokument366 SeitenStudent Attendance RecordsAdam KurniawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAMILY Law Final DraftDokument26 SeitenFAMILY Law Final DraftSarvjeet KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 116Dokument52 SeitenArticle 116balochimrankhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Diversity (Iran) : Communication Skills Report OnDokument9 SeitenCultural Diversity (Iran) : Communication Skills Report OnKainaat YaseenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian - Pak 1971Dokument31 SeitenIndian - Pak 1971Dhaval BhattNoch keine Bewertungen

- Can Shaitan or Jinn Make A Person SickDokument4 SeitenCan Shaitan or Jinn Make A Person SickdrsayeeduddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- NullDokument4 SeitenNullURWA AKBARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ze'evi, Dror - Producing Desire - Changing Sexual Discourse in The Ottoman Middle East, 1500-1900Dokument245 SeitenZe'evi, Dror - Producing Desire - Changing Sexual Discourse in The Ottoman Middle East, 1500-1900Joshua CurtisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Travelers To Greece and ConstantinopleDokument777 SeitenTravelers To Greece and ConstantinopleArt Critic100% (1)

- Translation of Names in Consumer-Oriented Texts: In-Flight Magazines Articles As A Case StudyDokument8 SeitenTranslation of Names in Consumer-Oriented Texts: In-Flight Magazines Articles As A Case StudyPiotr LorekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scope of Equity Is EqualityDokument9 SeitenScope of Equity Is EqualityFatima bNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ghuriakhel ShajrahDokument1 SeiteGhuriakhel ShajrahHaider AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Malay Ruler's Loss of ImmunityDokument43 SeitenThe Malay Ruler's Loss of Immunitygoldenscreen100% (8)

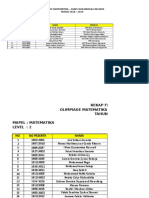

- Olimpiade Matematika, Sains dan Bahasa Inggris 2018-2019 ResultsDokument39 SeitenOlimpiade Matematika, Sains dan Bahasa Inggris 2018-2019 ResultsMargareta RetnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islamic Montessori Magazine Issue 3 June 2022Dokument20 SeitenIslamic Montessori Magazine Issue 3 June 2022Khairun Sofea ShahrulzamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zia Ul Quran Vol.1Dokument69 SeitenZia Ul Quran Vol.1fakhan90% (10)

- MCQsDokument35 SeitenMCQsDawood KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safe Serve CertificateDokument2 SeitenSafe Serve Certificateapi-4626713270% (1)

- Chap 6 Culture of PakistanDokument32 SeitenChap 6 Culture of Pakistanusman ahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Candidates Upgraded On Open Merit Seats For Sheikh Zayed Medical College, Rahim Yar Khan For The Session 2011-2012 (15th December 2011)Dokument3 SeitenList of Candidates Upgraded On Open Merit Seats For Sheikh Zayed Medical College, Rahim Yar Khan For The Session 2011-2012 (15th December 2011)Babar AkhtarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liste Des Candidats Par Ordre Alphabétique Convoqués Pour Accéder À La 4ème Année TAFSEM Option Commerce Au Sein de l'ENCG Agadir 2020-2021Dokument2 SeitenListe Des Candidats Par Ordre Alphabétique Convoqués Pour Accéder À La 4ème Année TAFSEM Option Commerce Au Sein de l'ENCG Agadir 2020-2021Mouf SidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arabic Loan Words in HausaDokument14 SeitenArabic Loan Words in Hausaulukmm2795Noch keine Bewertungen

- Critique of Islam - St. John of DamascusDokument4 SeitenCritique of Islam - St. John of Damascusndd00100% (1)

- Taj Mahal PresentationDokument1 SeiteTaj Mahal PresentationElo PengNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gospel of Barnabas: Secret Bible?: A Different Jesus?Dokument7 SeitenThe Gospel of Barnabas: Secret Bible?: A Different Jesus?shamirNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Aug 2016 - (Sesi 1)Dokument166 Seiten10 Aug 2016 - (Sesi 1)Daud Farook II0% (1)

- Jadwal Penyaluran Program Insentif Gbpns Kemenag 2022Dokument320 SeitenJadwal Penyaluran Program Insentif Gbpns Kemenag 2022Ufie UfieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saint of Rajabs Dua April 2015Dokument2 SeitenSaint of Rajabs Dua April 2015Ali Sarwari-QadriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surah Al WaaqiahDokument56 SeitenSurah Al WaaqiahShaidNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IVon EverandThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (78)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedVon Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (110)

- Caligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeVon EverandCaligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (16)

- Past Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersVon EverandPast Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (14)

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingVon EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernVon EverandTwelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (9)